Abstract

Background

Imaging cardiac excitation within ventricular myocardium is important in the treatment of cardiac arrhythmias and might help improve our understanding of arrhythmia mechanisms.

Objective

This study aims to rigorously assess the imaging performance of a three-dimensional (3-D) cardiac electrical imaging (3-DCEI) technique with the aid of 3-D intra-cardiac mapping from up to 216 intramural sites during paced rhythm and norepinephrine (NE) induced ventricular tachycardia (VT) in the rabbit heart.

Methods

Body surface potentials and intramural bipolar electrical recordings were simultaneously measured in a closed-chest condition in thirteen healthy rabbits. Single-site pacing and dual-site pacing were performed from ventricular walls and septum. VTs and premature ventricular complexes (PVCs) were induced by intravenous NE. Computer tomography images were obtained to construct geometry model.

Results

The non-invasively imaged activation sequence correlated well with invasively measured counterparts, with a correlation coefficient of 0.72±0.04, and a relative error of 0.30±0.02 averaged over 520 paced beats as well as 73 NE-induced PVCs and VT beats. All PVCs and VT beats initiated in the subendocardium by a nonreentrant mechanism. The averaged distance from imaged site of initial activation to pacing site or site of arrhythmias determined from intra-cardiac mapping was ~5mm. For dual-site pacing, the double origins were identified when they were located at contralateral sides of ventricles or at the lateral wall and the apex.

Conclusion

3-DCEI can non-invasively delineate important features of focal or multi-focal ventricular excitation. It offers the potential to aid in localizing the origins and imaging activation sequence of ventricular arrhythmias, and to provide noninvasive assessment of the underlying arrhythmia mechanisms.

Keywords: cardiac electric imaging, electrocardiography, inverse problem, cardiac mapping, pacing, ventricular tachycardia

Introduction

VT is a malignant arrhythmia that may degenerate to ventricular fibrillation and cause sudden cardiac death. VT can occur in patients with either structurally normal (e.g., idiopathic VT) or abnormal (e.g., congestive heart failure) hearts. In treatment of these arrhythmias, catheter ablation procedures1 require extensive invasive electrophysiological mapping2 to determine the arrhythmogenic substrate, and thus keep patients in the electrophysiology laboratory for prolonged periods. Noninvasive mapping techniques offer the potential to help define the underlying electrophysiological mechanisms and facilitate therapeutic treatments of cardiac disorders on a beat-to-beat basis.

Efforts have been put forward to solve the ECG inverse problem to estimate the equivalent cardiac sources from body surface potential maps (BSPMs). Such inverse approaches include moving dipole solutions,3,4,5 epicardial potential imaging,6,7,8 and heart surface activation imaging.9,10,11,12 Validation studies in imaging ventricular arrhythmias through both animal experiments7 and human studies13,14 have been previously reported.

However, due to the fact that arrhythmias typically originate from the subendocardium (and, at times, from intramural sites),15 it is important to image cardiac electrical activities throughout the 3-D myocardium. Investigations have been made in imaging the 3-D cardiac electrical activity with the aid of a heart cellular automaton model.16,17,18 Recently, an alternative 3-D cardiac electrical imaging (3-DCEI) approach has been proposed to image ventricular activation sequence from the inversely reconstructed equivalent current densities (ECDs).19,20 A feasibility study21 in the rabbit heart showed the potential application of this 3-DCEI approach in localizing the origin of activation and imaging activation sequence under single-site pacing.

The aim of the present study is to rigorously evaluate the imaging performance of this novel 3-DCEI approach20 using a well-established 3-D intra-cardiac mapping procedure21,22,23 during paced rhythms and during VT induced by norepinephrine (NE) in the rabbit heart. The 3-DCEI imaged results were quantitatively compared with simultaneous intra-cardiac mapping results and imaging performance was assessed. This study advances our previous experimental work21 in four important ways: 1) Single-site pacing from a large number of subendocardial or subepicardial sites in LV and RV simulates more realistic single cardiac sources originating from the subendocardium and subepicardium, while septal pacing simulates intramural cardiac activation originating from the interventricular septum; 2) Simultaneous dual-site pacing was induced to evaluate the capability of 3-DCEI to image more complex cardiac excitation processes; 3) The realistic geometry heart-torso model was constructed from CT scans after the mapping experiment to account for the potential geometrical errors related to the preceding open-chest surgery and plunge electrode placement; 4) 3-DCEI was applied to imaging the activation sequence of clinically-relevant NE-induced VTs and PVCs.

Methods

An expanded description of methods is in the online supplemental material.

Experimental Procedures

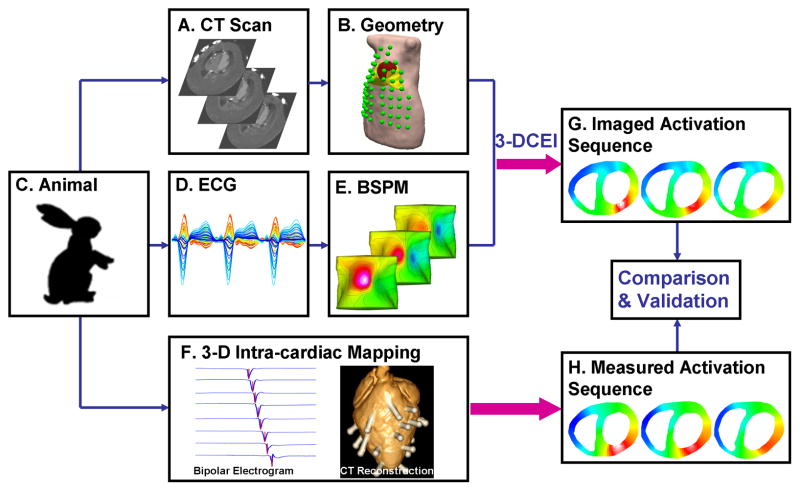

Thirteen healthy New Zealand white rabbits were studied under a protocol for simultaneous body surface potential mapping and 3-D intra-cardiac mapping (Figure 1). The protocol is approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Minnesota and the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Bipolar electrograms were continuously recorded (from up to 27 transmural plunge-needle electrodes inserted at LV, RV and septum22,23) with body surface potentials (from up to 64 BSPM electrodes) in a closed-chest condition. Immediately following the mapping study, UFCT scans were performed on the living rabbit to obtain the anatomical information. The plunge-needle electrodes were then carefully localized as previously described.22,23 Rapid single-site and simultaneous dual-site pacing were performed via bipolar electrode-pairs on selected plunge-needle electrodes. NE was infused at 25–100 μg/kg/min (3 minutes at each dose) to induce PVCs and VTs.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the experimental protocol for validating the 3-D cardiac electrical imaging (3-DCEI) technique with simultaneous measurements from 3-D intra-cardiac mapping. A. Cross-sectional CT slices showing detailed heart chambers and location of body surface electrodes and plunge-needle electrodes. B. Realistic geometry heart-torso model (green spots showing body surface electrodes). C. Animal model. D. Butterfly plot of multiple-channel ECGs. E. Body surface potential maps (BSPMs). F. Multiple-channel intramural bipolar electrograms during 3-D intra-cardiac mapping (left) and reconstruction from CT images of an isolated rabbit heart with labeled pins (right). G. Activation sequence non-invasively imaged from 3-DCEI. H. Measured activation sequence from invasive 3-D intra-cardiac mapping.

Data Analysis

The physical-model based 3-DCEI approach was previously described.20 The heart-torso model was constructed from UFCT images. Derived from bidomain theory,24 body surface potentials are linearly related to the ECD distribution within 3-D ventricular myocardium using the boundary element method. A spatiotemporal regularization technique and lead-field normalized weighted minimum norm25 estimation were used to solve the inverse problem and the activation time at each myocardial site was determined as the instant when the time course of the estimated ECD reaches its maximum magnitude.20

The measured activation sequence within the 3-D ventricular myocardium was constructed in a way that was slightly different from the previous method.18 The location of plunge-needle electrodes within the myocardium was determined directly from the same UFCT images used for constructing the heart-torso geometrical model. The activation time of each recording electrode was assigned on the basis of peak criteria,22,23,26 and the complete 3-D measured activation sequence was obtained through an interpolation algorithm.18

Numerical data are presented as mean ± SD. The CC and RE were computed respectively to quantify the agreement of overall activation pattern and the consistency of the activation time between measured and imaged activation sequence. The CC and RE are defined in the supplemental material. The LE is defined as the distance between site of earliest activation from 3-D intra-cardiac measurements and the center of mass of the myocardial region with the earliest imaged activation time.

Results

Experimentation and Modeling

After insertion of plunge electrodes, closure of the chest did not alter heart rate or mean arterial blood pressure (232 ± 6 vs 238 ±6 bpm and 62±4 vs 62±3 mm Hg, P=NS vs pre-closure) or total activation times of sinus beats (31±1ms vs 29±1ms, P=NS vs pre-closure), which were consistent with previously published data in control rabbits.18,23 The ventricular myocardium was tessellated into 6250±1137 evenly-spaced grid points. The spatial resolution of the ventricle models was 1 mm. There were 178±25 intramural bipolar electrodes during 3-D intra-cardiac mapping and 60±2 BSPM electrodes.

Single-Site Pacing

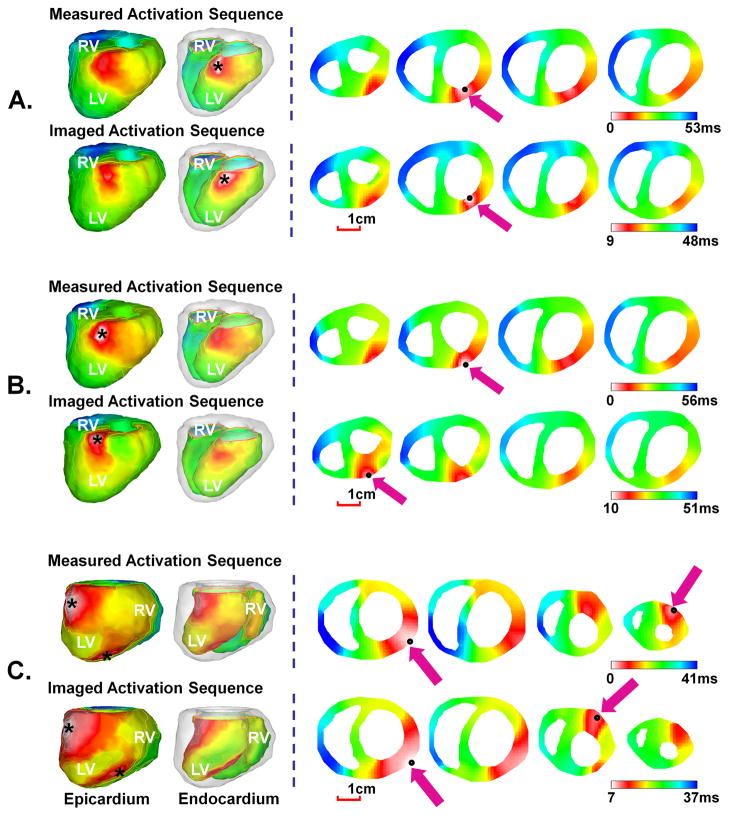

Single-site pacing was performed in rabbits P1–P9. The pacing sites were chosen to include multiple regions of LV, RV, and septum. Figure 2(A)–(B) show the representative example of the comparison between the measured and imaged activation sequence when rabbit P6 was paced respectively at subendocardium (Figure 2(A)) or subepicardium (Figure 2(B)) via a plunge-needle electrode located at anterior basal wall of LV. From the measured activation sequence of the endocardial-paced beat in Figure 2(A), the earliest activation was observed at the subendocardium. When the wavefront arrived at the epicardium, a relatively large breakthrough was noticed on the epicardial surface. The wavefront then propagated over the septum, and ended at the basal lateral wall of RV. The spatial activation pattern for the epicardial-paced beat in Figure 2(B) is similar to that of endocardial-paced beat, but the major difference is that the origin of the activation from both the measured and the imaged activation sequences is located at the subepicardium rather than the subendocardium. For both cases, the imaged activation sequence closely approximated the measured activation sequence, with a CC of 0.76 and a RE of 0.29 for endocardial-paced beat, and a CC of 0.77 and a RE of 0.30 for epicardial-paced beat. The origin of activation was visually localized at the subendocardium or subepicardium, with a low LE of 3.6mm and 3.0mm for these two cases respectively.

Figure 2.

Comparison between the 3-D activation sequence measured via 3-D intra-cardiac mapping and the 3-D activation sequence imaged by 3-DCEI when rabbit P6 was paced respectively at the endocardium (A) and epicardium (B) of LV basal anterior wall and when rabbit P3 was simultaneously paced at epicardium of LV apex and anterior basal left wall (C). The activation sequence is color coded from white to blue, corresponding to earliest and latest activation. In the left column, activation sequence is displayed on epicardial and endocardial surfaces, respectively. In the right column, four axial slices starting from ventricular base are displayed from left to right. The pacing site and the estimated initial site of activation are marked by a black asterisk in the left column and a black spot and a purple arrow in the right column. The scale bar is given for the axial slices. The epicardial and endocardial surfaces are displayed respectively in a left anterior view for rabbit P6 and in a left posterior view for rabbit P3.

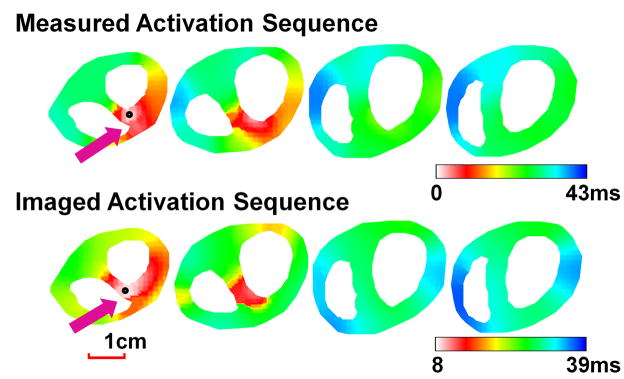

Septal pacing was performed via the selected plunge-needle electrodes placed in the interventricular septum for rabbits P7–P9. Figure 3 shows a representative example when rabbit P9 was paced at base septum via a septal electrode inserted from the anterior rabbit ventricles. From the measured map, the activation initiated at the intramural septum slightly closer to LV. The wavefront then propagated to the rest of the ventricles and terminated at the RV apex. The overall pattern of the imaged activation sequence resembled the measured one, with a CC of 0.68, and a RE of 0.29. The initiation site was well localized at the septum with a LE of 4.4 mm for this beat.

Figure 3.

Comparison between measured and imaged activation sequence when rabbit P9 was paced from the basal septum.

A total of 300 beats of LV pacing from 15 selected plunge-needle electrodes were analyzed (10 endocardial paced beats and 10 epicardial paced beats for each plunge-needle electrode). The ability of 3-DCEI in reconstructing the overall activation pattern and localizing the pacing site during LV pacing in quantitative comparison is summarized in Table 1. A slightly better performance of imaging epicardial pacing was observed in terms of LE. Another 150 beats of single-site pacing at 10 RV epicardial sites and 5 septal sites (10 paced beats for each pacing) were analyzed and the quantitative comparison is summarized in Table 2. A slight increase of LE was observed during septal pacing, as compared to LV pacing. The averaged CC and averaged RE for the combination of LV pacing, RV pacing, and septal pacing were 0.73±0.04 and 0.30±0.02 respectively, suggesting excellent agreement between the measured and imaged activation sequence. Furthermore, the pacing sites were estimated to be 4.9±1.3mm away from the measured ones, suggesting reasonable localization accuracy of this approach.

Table 1.

Quantitative comparison between measured and imaged activation sequence in single-site LV pacing.

| Rabbit No. | Pacing Needle Location | Endocardial LV Pacing | Epicardial LV Pacing | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | RE | LE (mm) | CC | RE | LE (mm) | ||

| P1 | LVA | 0.71 | 0.25 | 4.7 | 0.67 | 0.23 | 3.2 |

| P2 | BLW | 0.73 | 0.33 | 6.2 | 0.75 | 0.31 | 5.7 |

| P3 | Anterior BLW | 0.78 | 0.30 | 7.6 | 0.79 | 0.32 | 7.1 |

| LVA | 0.65 | 0.27 | 5.2 | 0.69 | 0.27 | 4.1 | |

| P4 | BLW | 0.81 | 0.29 | 4.6 | 0.86 | 0.27 | 2.7 |

| Posterior BLW | 0.73 | 0.34 | 3.9 | 0.71 | 0.33 | 4.2 | |

| P5 | Posterior MLW | 0.74 | 0.34 | 3.9 | 0.73 | 0.32 | 4.8 |

| LVA | 0.74 | 0.32 | 7.4 | 0.75 | 0.29 | 7.4 | |

| Anterior BLW | 0.63 | 0.30 | 4.9 | 0.61 | 0.33 | 4.1 | |

| P6 | Anterior BLW | 0.71 | 0.30 | 3.8 | 0.75 | 0.31 | 2.3 |

| P7 | Anterior MLW | 0.79 | 0.28 | 3.7 | 0.81 | 0.27 | 3.4 |

| Posterior MLW | 0.69 | 0.29 | 5.1 | 0.68 | 0.31 | 5.0 | |

| P8 | MLW | 0.72 | 0.33 | 4.7 | 0.73 | 0.32 | 5.1 |

| BLW | 0.75 | 0.26 | 3.8 | 0.74 | 0.27 | 3.2 | |

| P9 | MLW | 0.76 | 0.31 | 4.6 | 0.77 | 0.32 | 4.5 |

|

| |||||||

| Mean | 0.73±0.05 | 0.30±0.03 | 4.9±1.2 | 0.74±0.06 | 0.29±0.03 | 4.5±1.5 | |

BLW, basal left wall; LVA, left ventricle apex; MLW, middle left wall.

Table 2.

Quantitative comparison between measured and imaged activation sequence in single-site RV and septal pacing.

| Rabbit No. | Pacing Needle Location | CC | RE | LE (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | MRW | 0.75 | 0.30 | 3.2 |

| P2 | Posterior MRW | 0.68 | 0.31 | 7.8 |

| MRW | 0.74 | 0.29 | 4.0 | |

| P3 | BRW | 0.78 | 0.30 | 5.6 |

| P4 | Anterior BRW | 0.73 | 0.26 | 4.3 |

| Posterior MRW | 0.68 | 0.36 | 5.2 | |

| P5 | BRW | 0.80 | 0.32 | 6.3 |

| RVA | 0.78 | 0.28 | 4.9 | |

| P6 | Posterior MRW | 0.74 | 0.27 | 5.5 |

| MRW | 0.69 | 0.32 | 4.7 | |

| P7 | Posterior MS | 0.67 | 0.30 | 5.3 |

| Posterior AS | 0.72 | 0.33 | 7.2 | |

| P8 | Posterior AS | 0.71 | 0.29 | 5.0 |

| P9 | Anterior BS | 0.69 | 0.31 | 4.7 |

| Anterior MS | 0.68 | 0.32 | 5.8 | |

|

| ||||

| Mean | 0.72±0.04 | 0.30±0.03 | 5.3±1.2 | |

AS, apex septum; BRW, basal right wall; BS, basal septum; MRW, middle right wall; MS, middle septum; RVA, right ventricle apex.

Dual-Site Pacing

Dual-site pacing was performed in rabbits P1–P5. Figure 2(C) shows the representative comparison when rabbit P3 was simultaneously paced at an LV epicardial site in the basal lateral wall and at an LV epicardial site in the posterior apex. The two pacing sites were 21mm apart within the heart. The activation ended in the RV basal lateral wall. The non-invasively reconstructed activation sequence closely resembled the measured one, with a CC of 0.72 and a RE of 0.30. The double origins of the activation were clearly resolved from the imaged result. A total of 70 beats of simultaneous dual-site pacing from 7 pairs of epicardial pacing sites (10 beats for each dual-site pacing) were analyzed. The performance of 3-DCEI in imaging dual-site pacing in quantitative comparison is summarized in Table 3. The inter-site distance for the two pacing sites ranged from 10–27mm. The double origins were identified when they were located at contralateral sides of ventricles or at the ventricular lateral wall and the apex, respectively. The averaged CC and RE were 0.69±0.05 and 0.33±0.05 respectively, suggesting excellent agreement between measured and estimated activation sequences when imaging more complex activation pattern other than single-site pacing.

Table 3.

Quantitative comparison between measured and imaged activation sequence in simultaneous dual-site pacing.

| Rabbit No. | Pacing Needle Locations | CC | RE |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | LVA, MRW | 0.65 | 0.34 |

| P2 | BLW, Posterior MRW | 0.59 | 0.39 |

| P3 | Anterior BLW, LVA | 0.71 | 0.33 |

| P4 | Anterior BRW, Posterior BLW | 0.72 | 0.33 |

| P5 | BRW, LVA | 0.69 | 0.31 |

| RVA, LVA | 0.71 | 0.32 | |

| Anterior BLW, LVA | 0.73 | 0.34 | |

|

| |||

| Mean | 0.69±0.05 | 0.33±0.05 | |

BLW, basal left wall; BRW, basal right wall; LVA, left ventricle apex; MRW, middle right wall; RVA, right ventricle apex.

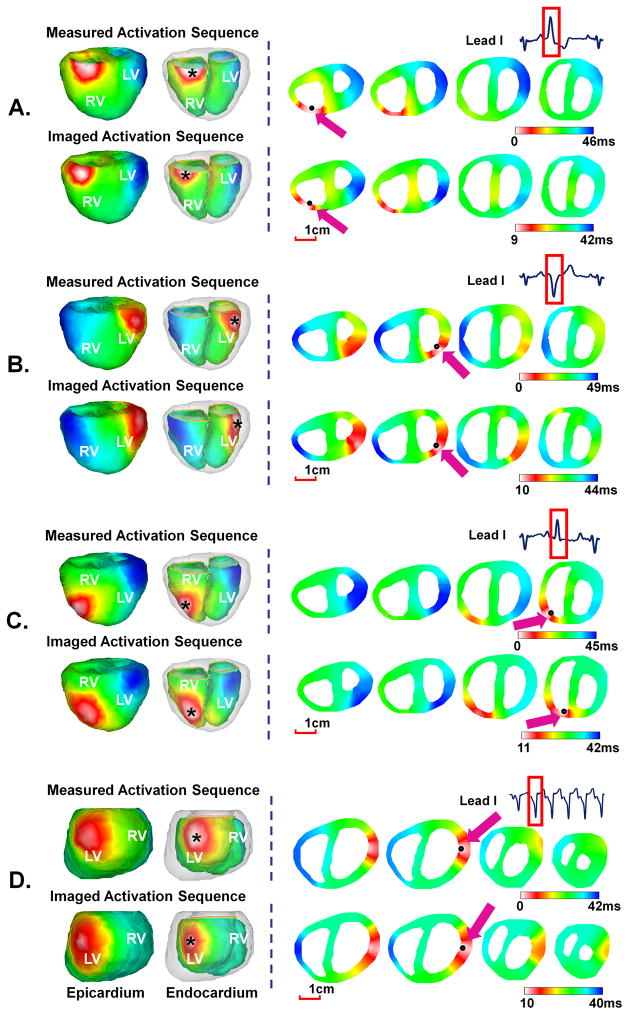

PVCs and Monomorphic VTs

Isolated PVCs and nonsustained monomorphic VTs were obtained during the infusion of NE in rabbits V1–V4. A total of 28 PVCs and 45 beats of VTs were analyzed and the mechanism of the arrhythmia was defined for all these ectopic beats from intra-cardiac mapping. All these PVC and VT beats initiated in the subendocardium and did so by a focal, and what we believe to be a nonreentrant mechanism, based on the lack of intervening electrical activity between the preceding beat and the initiation of the ectopic beat in intramural recordings.22,23 PVCs in each rabbit demonstrated different initial sites of activation, except rabbit V1 which had PVCs only initiated from a single site. Seven PVCs initiated in the LV and 21 in the RV. PVCs initiated with a coupling interval of 279±39ms and conducted with a total activation time of 46±9ms. The averaged coupling interval among all maintained VT beats was 216±11ms, and the averaged total activation time was 48±7ms. The quantitative comparison for PVCs and VTs beats is summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Quantitative comparison between measured and imaged activation sequence in norepinephrine induced VT.

| Rabbit No. | Arrhythmia Type | Origin | CC | RE | LE (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1 | PVC | LVA | 0.61 | 0.31 | 7.4 |

| Monomorphic VT | BLW | 0.70 | 0.33 | 5.4 | |

| V2 | PVC | MRW | 0.71 | 0.30 | 5.0 |

| PVC | Posterior MRW | 0.69 | 0.31 | 3.8 | |

| Monomorphic VT | Anterior MRW | 0.77 | 0.31 | 6.0 | |

| V3 | PVC | MRW | 0.75 | 0.32 | 4.8 |

| PVC | BLW | 0.70 | 0.30 | 4.8 | |

| PVC | BRW | 0.69 | 0.31 | 4.7 | |

| Monomorphic VT | BRW | 0.73 | 0.29 | 7.1 | |

| V4 | PVC | BRW | 0.69 | 0.31 | 4.9 |

| PVC | Posterior MRW | 0.65 | 0.27 | 7.1 | |

| Monomorphic VT | BRW | 0.68 | 0.32 | 4.0 | |

|

| |||||

| Mean | 0.70±0.04 | 0.31±0.02 | 5.4±1.2 | ||

BLW, basal left wall; BRW, basal right wall; LVA, left ventricle apex; MRW, middle right wall.

Figure 4(A)–(C) show the comparison between the measured and imaged activation sequence for three PVC beats in rabbit V3. Different activation patterns were observed, with different initiation sites at subendocardium of basal right wall, basal left wall, and middle right wall respectively. The imaged results resembled the measured counterparts, with a CC of 0.69 and a RE of 0.31 for PVC in Figure 4(A), a CC of 0.71 and a RE of 0.29 for PVC in Figure 4(B), and a CC of 0.78 and a RE of 0.28 for PVC in Figure 4(C). The initiation sites were estimated to be 4.8mm, 3.6mm, and 4.5mm from the measured sites respectively.

Figure 4.

Comparison between measured and imaged activation sequence of PVCs in three activation patterns (A), (B), and (C) for rabbit V3 and a six-beat monomorphic VT (D) for rabbit V1. The epicardial and endocardial surfaces are displayed respectively in the anterior view for rabbit V3 and left posterior view for rabbit V1.

An example of a representative VT beat in a six-beat monomorphic VT in rabbit V1 is shown in Figure 4(D). After initiation, all VT beats looked similar. As shown in the measured activation sequence, the VT beat initiated within subendocardium by a focal (nonreentrant) mechanism at the basal lateral wall of LV. After initiation, activation propagated to the RV and terminated at base of RV with a total activation time of 42ms. The imaged activation sequence matched measured one, with a CC of 0.76 and a RE of 0.30. The initiation of the activation was well localized with a LE of 4.8mm.

Discussion

The present study aims to assess the performance of the 3-DCEI technique in non-invasively reconstructing the 3-D ventricular activation sequence and localizing the origin of activation in the in vivo rabbit heart. By comparing the imaged results with simultaneous measurements through 3-D intra-cardiac mapping from up to 216 intramural sites, this study validated the ability of 3-DCEI to identify, locate and resolve single and double electric events during single-site and dual-site paced rhythm, as well as NE-induced nonsustained monomorphic VTs and PVCs. Our results showed an excellent agreement of the spatial activation pattern between the non-invasively imaged activation sequence and its directly measured counterparts, as quantified by a CC of 0.72 and a RE of 0.30 averaged over all paced and ectopic beats. The origins of the activation in imaged results had an averaged distance of ~5mm from the pacing sites for the single-site paced beats (450 beats at 45 pacing locations in 9 animals) and site of initiation for ventricular ectopic beats determined by intra-cardiac mapping (73 beats in 4 animals). These findings imply that 3-DCEI is feasible in reconstructing the spatial patterns of 3-D ventricular activation sequences, localizing the focal or multiple arrhythmogenic foci, and imaging dynamically changing arrhythmia on a beat-to-beat basis.

Rigorous validation studies in biological systems are crucial for establishing any imaging methods. Compared with other animal experiments and human studies7,12,13,14,27,28,29 in validating epicardial potential and heart surface activation imaging techniques, the present study has used a novel in vivo experimental design in which BSPMs were obtained simultaneously with intramural electrical recordings from plunge-needle electrodes in a closed-chest condition, and thus provided quantitative assessments of the 3-DCEI approach. The experimental protocol has been refined from our previous studies18,21 in using CT images obtained on the anesthetized animals immediately following the mapping studies. Such improvements could more accurately model the heart-torso geometry by considering certain effects related to the procedures of open-chest surgery (e.g., rotation of the heart orientation and position-shift of BSPM electrodes) and more accurately determine the location of the plunge-needle electrodes within the detailed heart model, as compared with previous studies.18,21 While some scatters caused by the needles were observed on CT images, we were still able to reconstruct the geometry of the ventricular cavities (which were brightly visualized by intravenous contrast) and localize the needles (shown as very bright dot spots).

The present physical-model based 3-DCEI approach only uses the general biophysical relationships governing the cardiac electrical activity, without incorporating any physiological assumptions. By solving the spatial-temporal linear inverse problem, the 3-DCEI approach estimated the instantaneous current density at each grid point from the BSPMs and thus extracted the spatial distribution of activation time throughout 3-D ventricular myocardium. Like other studies,14,28 we experience smoothing effects when we solve the inverse problem, especially at the earliest and latest activation times, when body surface potentials are of relatively small magnitudes compared to noise. As such, the resultant solution may lead to spatially smoothed images, and thus cause the delayed initiation and premature termination. Nevertheless, the imaged activation sequence still provided a close match to the direct measurement, suggesting that significant information regarding ventricular excitation has been preserved in imaged results. Such information revealed the activation pattern within a single map and helped identify the initiation sites in the endocardium, epicardium or intramural septum during single- and dual-site pacing.

For the first time, the 3-DCEI approach was applied in imaging activation sequence of ventricular arrhythmia and validated with the aid of 3-D intra-cardiac mapping. NE simulated the activation of the sympathetic nervous system and induced PVC and VT. The measured activation sequence also showed that these arrhythmias usually originated within the subendocardium and may arise from Purkinje cells or subendocardial myocardium. The origins have been well localized by the noninvasive 3-DCEI approach with good accuracy, implying that this approach may be valuable for imaging focal ventricular arrhythmias arising in the deeper myocardium. For the earliest activation onset, it is possible that PVCs and beats of VT may initiate close to the plunge electrode that records earliest electrical activity. However, mapping at the resolution that we employed in this study (recording from 200 intramural sites in the rabbit heart is equivalent to recording from up to 2600 intramural sites in the canine heart)23 and having each bipolar initiation site surrounded by several dozen intramural recording sites that recorded later activity, we minimized the effects of extrapolation so that we anticipated earliest onset to be immediately adjacent to the earliest recording site.23

Our results indicated that the site of earliest activation was always in close proximity to the measured initiation site, with an averaged distance from imaged and measured sites to be ~5mm. While the noninvasive imaging approach would enable the clinical electrophysiologist to localize to within ~5 mm of the region of the myocardium from which focal activation is arising, additional catheter mapping would certainly be required to more precisely localize this focal site for the ensuing ablation. The key values of this approach would be to shorten the time for ablation and, perhaps more importantly, to help determine whether initiation is arising in the endocardium or the epicardium (which would also shorten ablation time since epicardial ablation requires a pericardial approach, and this is often initiated after endocardial catheter mapping suggests an epicardial site of origin). This study also extended the evaluation in imaging relatively more complex activation pattern (e.g., in the presence of multiple, interacting wavefronts), as simulated by dual-site pacing. This has specific clinical relevance when more than one arrhythmogenic activity (e.g., two pre-excitation sites or fusion beat) are taking place simultaneously, and it would then be imperative to know the locations of these electric events before ablation. Furthermore, dual-site pacing simulates the cardiac resynchronization therapy,30 which is an important clinical procedure in treatment of heart failure patient and may have potential clinical applications in this area.

The current imaging accuracy is considered to be associated with the inherited errors based on experimental protocol used. Note that the experimental errors are mainly determined by the current procedures and would not linearly scale to the size of the subjects, and thus it shall be reasonable to anticipate that the imaging accuracy would be maintained at the level comparable to rabbit heart (and that would be clinically useful) in species with larger cardiac size. With further development and validation studies in larger species to improve the imaging accuracy, this physical-model based 3-DCEI technique may have a potential to become a clinically complementary tool to aid in interventional therapeutic procedures.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study suggests that the 3-DCEI approach can reconstruct 3-D ventricular activation sequence and localize the origin of activation during pacing and focal ventricular arrhythmias, as validated by 3-D intra-cardiac mapping in the rabbit heart. It also implies the potential application of 3-DCEI as a clinically useful tool to aid in localizing the origins of ventricular arrhythmias and understanding the mechanism of these arrhythmias.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health [HL080093 to B.H., HL 073966 to S.M.P.], and the National Science Foundation [CBET-0756331 to B.H.]. C.H. was supported in part by a Predoctoral Fellowship from the American Heart Association, Midwest Affiliate.

The authors are grateful to Drs. Dakun Lai and Chenguang Liu for assistance in data collection and useful discussions.

Abbreviations

- 3-D

Three-dimensional

- CC

Correlation coefficient

- CT

Computer tomography

- ECG

Electrocardiograph

- LE

Localization error

- LV

Left ventricle

- PVC

Premature ventricular complex

- RE

Relative error

- RV

Right ventricle

- UFCT

Ultra fast computer tomography

- VT

Ventricular tachycardia

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Bin He is an inventor of a patent related to the imaging technique used in this study.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Morady F. Radio-frequency ablation as treatment for cardiac arrhythmias. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:534–544. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902183400707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong J, Calkins H, Solomon SB, et al. Integrated electroanatomic mapping with three-dimensional computed tomographic images for real-time guided ablations. Circulation. 2006;113:186–194. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.565200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okamoto Y, Teramachi Y, Musha T. Limitation of the inverse problem in body surface potential mapping. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1983;30:749–754. doi: 10.1109/tbme.1983.325190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gulrajani RM, Roberge FA, Savard P. Moving dipole inverse ECG and EEG solutions. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1984;31:903–910. doi: 10.1109/TBME.1984.325257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mirvis DM, Keller FW, Ideker RE, Cox JW, Jr, Dowdie RF, Zettergren DG. Detection and localization of multiple epicardial electrical generators by a two-dipole ranging technique. Circ Res. 1977;41:551–557. doi: 10.1161/01.res.41.4.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barr RC, Ramsey M, Spach MS. Relating epicardial to body surface potential distributions by means of transfer coefficients based on geometry measurements. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1977;24:1–11. doi: 10.1109/TBME.1977.326201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burnes JE, Taccardi B, Rudy Y. A noninvasive imaging modality for cardiac arrhythmias. Circulation. 2000;102:2152–2158. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.17.2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greensite F, Huiskamp G. An improved method for estimating epicardial potentials from the body surface. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1998;45:98–104. doi: 10.1109/10.650360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuppen JJ, van Oosterom A. Model studies with the inversely calculated isochrones of ventricular depolarization. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1984;31:652–659. doi: 10.1109/TBME.1984.325315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pullan AJ, Cheng LK, Nash MP, Bradley CP, Paterson DJ. Noninvasive electrical imaging of the heart: theory and model development. Ann Biomed Eng. 2001;29:817–836. doi: 10.1114/1.1408921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huiskamp G, Greensite F. A new method for myocardial activation imaging. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1997;44:433–446. doi: 10.1109/10.581930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tilg B, Fischer G, Modre R, et al. Model-based imaging of cardiac electrical excitation in humans. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2002;21:1031–1039. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2002.804438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghosh S, Rhee EK, Avari JN, Woodard PK, Rudy Y. Cardiac memory in patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: noninvasive imaging of activation and repolarization before and after catheter ablation. Circulation. 2008;118:907–915. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.781658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berger T, Fischer G, Pfeifer B, et al. Single-beat noninvasive imaging of cardiac electrophysiology of ventricular pre-excitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:2045–2052. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pogwizd SM, McKenzie JP, Cain ME. Mechanisms underlying spontaneous and induced ventricular arrhythmias in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1998;98:2404–2414. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.22.2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li G, He B. Localization of the site of origin of cardiac activation by means of a heart-model-based electrocardiographic imaging approach. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2001;48:660–669. doi: 10.1109/10.923784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He B, Li G, Zhang X. Noninvasive imaging of cardiac transmembrane potentials within three-dimensional myocardium by means of a realistic geometry anisotropic heart model. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2003;50:1190–1202. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2003.817637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang X, Ramachandra I, Liu Z, Muneer B, Pogwizd SM, He B. Noninvasive three-dimensional electrocardiographic imaging of ventricular activation sequence. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H2724–H2732. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00639.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He B, Wu D. Imaging and visualization of 3-D cardiac electric activity. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed. 2001;5:181–186. doi: 10.1109/4233.945288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Z, Liu C, He B. Noninvasive reconstruction of three-dimensional ventricular activation sequence from the inverse solution of distributed equivalent current density. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2006;25:1307–1318. doi: 10.1109/tmi.2006.882140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han C, Liu Z, Zhang X, Pogwizd SM, He B. Noninvasive three-dimensional cardiac activation imaging from body surface potential maps: a computational and experimental study on a rabbit model. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2008;27:1622–1630. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2008.929094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pogwizd SM. Focal mechanisms underlying ventricular tachycardia during prolonged ischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1994;90:1441–1458. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.3.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pogwizd SM. Nonreentrant mechanisms underlying spontaneous ventricular arrhythmias in a model of nonischemic heart failure in rabbits. Circulation. 1995;92:1034–1048. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.4.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller WT, Geselowitz DB. Simulation studies of the electrocardiogram. I. The normal heart. Circ Res. 1978;43:301–315. doi: 10.1161/01.res.43.2.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang JZ, Williamson SJ, Kaufman L. Magnetic source images determined by a lead-field analysis: the unique minimum-norm least-squares estimation. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1992;39:665–675. doi: 10.1109/10.142641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Durrer D, van der Tweel LH. Spread of activation in the left ventricular wall of the dog. II. Activation conditions at the epicardial surface. Am Heart J. 1954;47:192–203. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(54)90249-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barr RC, Spach MS. Inverse calculation of QRS-T epicardial potentials from body surface potential distributions for normal and ectopic beats in the intact dog. Circ Res. 1978;42:661–675. doi: 10.1161/01.res.42.5.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oster HS, Taccardi B, Lux RL, Ershler PR, Rudy Y. Noninvasive electrocardiographic imaging: reconstruction of epicardial potentials, electrograms, and isochrones and localization of single and multiple electrocardiac events. Circulation. 1997;96:1012–1024. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.3.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghanem RN, Jia P, Ramanathan C, Ryu K, Markowitz A, Rudy Y. Noninvasive electrocardiographic imaging (ECGI): comparison to intraoperative mapping in patients. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:339–54. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2004.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abraham WT, Fisher WG, Smith AL, et al. Cardiac resynchronization in chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1845–1853. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.