Abstract

Community participation may be especially important for older adults, who are often at risk for unwanted declines in participation. We estimated the prevalence of community participation restriction (PR) due to perceived environmental barriers among older adults (≥50 years) and compared the impact among those with selected chronic conditions. Individuals with low-prevalence conditions reported high community PR (9.1–20.4%), while those with highly prevalent conditions (e.g., arthritis) had relatively low community PR (5.1–10.0%) but represented the greatest absolute numbers of condition-associated burden (>1 million). Across all conditions, more than half of those with community PR reported being restricted “always or often.” Community PR most often resulted from modifiable environmental barriers. Promising targets to reduce community PR among adults ≥50 years with chronic conditions, particularly arthritis, include building design, sidewalks/curbs, crowd control, and interventions that improve the built environment.

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines “participation restriction” (PR), a key feature of the revised International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), as “problems an individual may experience in involvement in life situations,” and it reflects the negative consequences of health conditions on important personal and societal domains [1]. Community participation is an important type of participation because having and maintaining valued life roles and activities is associated with better psychological well-being and self-rated health [2–4] and may be especially important for older adults, who are often at risk for unwanted declines in participation [5–7]. There is a growing interest in PR from public health, medical, and social perspectives, partly because “even when poor health persists, participation may still be maintained” [8]. PR from an ICF perspective considers the influence of environment, in all its forms, on one's ability to engage in life situations. A recent independent validity study found that the ICF model, including its conceptualization of participation, is useful for examining disability in aging research [9].

Despite some studies [10–14], gaps remain in research on the interaction between older adults and their environment. Among limited findings, arthritis has consistently been associated with high levels of PR and disability in both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies [2, 15–21]. Also, features of the “built environment” and poor “walkability” of neighborhoods have been identified as barriers for individuals with varying levels of physical impairment [11]. Combining both health status and environmental perspectives provides an ideal context in which to examine how older adults with chronic health conditions participate in their communities.

The purpose of this study was to estimate the prevalence of community PR due to perceived environmental barriers among older adults (≥50 years) and to compare the impact among those with selected chronic conditions. Previous reports in the literature suggest that community PR would be greatest among older adults with disabling conditions (e.g., arthritis, stroke) and sensory deprivation (e.g., hearing or vision loss) [5, 8, 19, 21–23].

2. Materials and Methods

Data Source —

Data were obtained from the 2002 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), an ongoing, multistage probability survey conducted annually by a standardized in-person interview in English or Spanish. The NHIS is designed to be representative of the US civilian, noninstitutionalized population [24]. In 2002, a supplement based on Healthy People 2010 content [25], Disability and Secondary Conditions Questions: Assistive Technologies and Environmental Barriers, was added to the Sample Adult Core questionnaire [26], from which our sample was drawn. The Sample Adult Core was administered to 31,044 individuals ages ≥18 years; only respondents ≥50 years (n = 12,376) were included in this analysis.

2.1. Definition of Variables

2.1.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

Sociodemographic characteristics were examined to characterize the sample. These were age, sex, race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic Non-Hispanic Other), annual household income (>$20,000, <$20,000, and unknown), and education (≥high school, < high school, and unknown).

We examined the prevalence of three main outcomes: (1) community PR, (2) condition-associated absolute burden of community PR, and (3) community environmental barriers.

2.1.2. Community Participation Restriction and Related Environmental Barriers

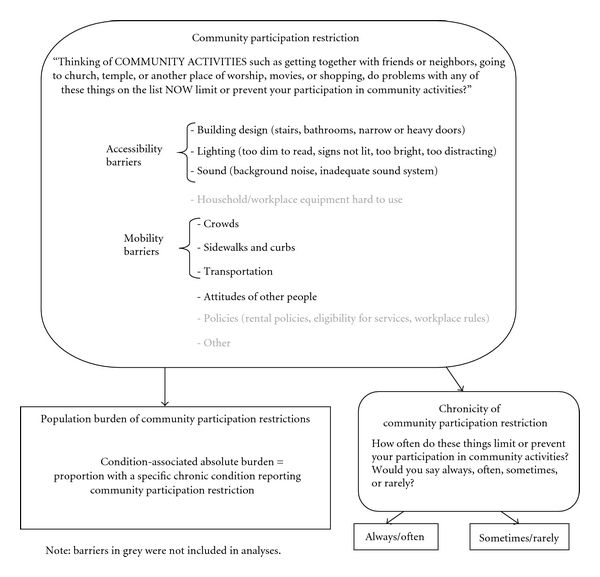

Participants were shown a list of ten environmental barriers (building design, lighting, sound, crowds, sidewalks and curbs, and transportation, household or workplace equipment hard to use, attitudes of other people, policies, and other) and were asked: “Thinking of COMMUNITY ACTIVITIES such as getting together with friends or neighbors, going to church, temple, or another place of worship, movies, or shopping, do problems with any of these things on the list NOW limit or prevent your participation in community activities?” (Figure 1). Community PR was defined as a “yes” to this question. Respondents answering yes were next asked to identify which items on the list were barriers to them and to report how often they experienced these barriers (collapsed to always/often or sometimes/rarely). Conceptually, the first three barriers (building design, lighting, and sound) fit together as “accessibility barriers,” while crowds, sidewalks/curbs, and transportation made up a category of “mobility barriers.” “Household/workplace equipment hard to use” was omitted because it pertained to noncommunity settings; “other” was excluded because of high item nonresponse. “Attitudes of other people” was analyzed independently. The policy category was excluded from the analysis because it had a low item response rate with estimates failing to meet minimum reliability criteria (relative standard error <30.0) for any condition examined.

Figure 1.

2.1.3. Condition-Associated Absolute Burden of Community PR

For each condition (defined below), the associated burden of community PR was estimated as the absolute number of respondents with the condition reporting community PR. Condition-associated absolute burden was also examined for those with each chronic condition who also had arthritis as a comorbidity (described below).

2.1.4. 12 Chronic Conditions

The presence of seven diagnosed chronic conditions or condition categories was based on a “yes” response to “Have you EVER been told by a doctor or other health professional that you have…” for each of arthritis, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, heart conditions (i.e., angina pectoris, coronary heart disease, heart attack, heart failure, or heart condition/disease), neurological conditions (i.e., multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease, neuropathy, or seizures), and respiratory conditions (i.e., asthma, emphysema, or chronic bronchitis). Hearing impairments were defined as a response of “a lot of trouble hearing” or “deaf” to “Which statement best describes your hearing without a hearing aid: good, a little trouble, a lot of trouble, deaf?” Vision impairments were defined as a response of “yes” to “Do you have any trouble seeing, even when wearing glasses or contact lenses?” Obesity was defined as a body mass index (weight in kg/height in m2) of ≥30. Depression/anxiety was determined by a “yes” response to “DURING THE PAST 12 MONTHS, have you been frequently depressed or anxious?” Serious psychological distress (SPD) was measured with the Kessler 6 (K6), a psychological distress scale developed to screen for and monitor population prevalence and trends of nonspecific SPD. It comprises 6 questions on a 0 (none of the time) to 4 (all of the time) point scale asking how often in the past 30 days a person felt sad, worthless, nervous, restless, hopeless, or that everything was an effort. Responses are summed for a total score (0–26); we used a cutoff of ≥13 as recommended by the scale developer to identify SPD among respondents [27]. Respondents could have more than one chronic condition; therefore, chronic conditions examined were not mutually exclusive.

Missing values for community PR and individual barriers were assigned to the most conservative category, that is, if a respondent did not identify community PR with a “yes” response, he/she was assigned to the no category. Missing values for chronic conditions ranged from n = 8 (0.06%) for respiratory conditions to n = 613 (5.0%) for obesity. Age, sex, and race/ethnicity variables were provided by NCHS with no missing values.

2.1.5. Comorbidities

To examine the effects of comorbidities on community PR, we created a count variable indicating how many of the 12 chronic conditions described above each respondent reported (categorized as 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and ≥5).

2.1.6. Arthritis as a Comorbidity

Given its widespread prevalence and status as the most common cause of disability among US adults [28], arthritis was expected to be associated with high levels of community PR. We examined community PR among those with each of the other chronic conditions plus arthritis as a comorbidity.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Weighted frequencies, 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), and proportions were obtained using SAS 9.2 [29] and SUDAAN v10 [30] statistical software, accounting for the complex sampling design. Statistical significance was determined by nonoverlapping 95% CI. Estimates were considered unstable if they did not meet minimum reliability criteria (i.e., a relative standard error (RSE) ≥30%) and are not reported [31]. Estimates were considered potentially unreliable if they had an RSE between 20% and 30% and have been flagged as such in tables and footnotes.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characteristics of the Sample

The weighted median age of the participants was 61.5 (mean = 64.0; standard deviation 13.4) (Table 1) (The age of respondents ≥85 years are reported as 85 years in the NHIS public release files: ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHIS/2002/samadult.pdf. Therefore, the mean, standard deviation, median, and range of ages may be underestimated.). The majority of the participants were female (54.2%), non-Hispanic Whites (80.4%) and those with an annual household income of ≥$20,000 (70.7%) and at least a high school education (77.8%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Weighted characterization of the study sample of 12,376 USA Adults ≥50 years, 2002.

| Weighted frequency (in 1,000s) |

%1 (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 76,634 | 100 |

| Age (median, mean ± SD) | 61.5, 64.0 ± 13.4 |

|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 35,123 | 45.8 (44.8–46.8) |

| Female | 41,511 | 54.2 (53.2–55.2) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-hispanic white | 61,597 | 80.4 (79.4–81.4) |

| Non-hispanic black | 6,970 | 9.1 (8.4–9.8) |

| Hispanic | 5,581 | 7.3 (6.7–7.9) |

| Non-hispanic other | 2,486 | 3.2 (2.8–3.7) |

| Income | ||

| $20K or more | 54,144 | 70.7 (69.6–71.7) |

| Less than $20K | 16,232 | 21.2 (20.3–22.1) |

| Unknown | 6,258 | 8.2 (7.5–8.9) |

| Education | ||

| >/= high school | 59,616 | 77.8 (76.9–78.7) |

| Less than high school | 15,930 | 20.8 (19.9–21.6) |

| Unknown | 1,088 | 1.4 (1.1–1.7) |

1May not add to 100 percent due to rounding.

3.2. Chronic Conditions

Chronic conditions were common among adults ≥50 years; 23.7% reported one condition and 55.8% reported two or more conditions Most condition groups examined (8 of 12) were reported by >10% of the sample (Table 2). Hypertension was the most frequently reported chronic condition (44.4%, 95% CI = 43.5–45.3), followed by arthritis (39.8%, 95% CI = 38.7–40.8). Neurological conditions (4.3%) and SPD (3.1%) were the least reported conditions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Weighted estimates and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) of prevalence of selected chronic conditions; community participation restriction (PR) and condition-associated absolute burden; chronicity of community PR; arthritis comorbidity and associated absolute burden among adults ≥50 years with selected chronic conditions, 2002.*

| Prevalence in population | Community PR | Chronicity of community PR† | Arthritis comorbidity‡ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (95% CI) | n (in 1,000s) | % (95% CI) | Condition-associated absolute burden, n (in 1,000s) | % (95% CI) | n (in 1,000s) | Community PR% (95% CI) | Associated absolute burden, n (in 1,000s) | |

| Arthritis | 39.8 (38.7–40.8) | 30,312 | 6.4 (5.6–7.1) | 1,929 | 56.7 (51.9–61.4) | 1,058 | ~ | ~ |

| Hypertension | 44.4 (43.5–45.3) | 33,908 | 5.3 (4.6–5.9) | 1,781 | 56.3 (51.3–61.4) | 961 | 7.8 (6.8–8.9) | 1,323 |

| Depression/anxiety | 17.3 (16.5–18.2) | 13,229 | 9.9 (8.4–11.3) | 1,304 | 65.7 (59.5–71.8) | 813 | 12.0 (10.1–13.9) | 868 |

| Heart conditions | 22.3 (21.4–23.1) | 17,030 | 6.7 (5.7–7.7) | 1,140 | 59.7 (53.5–65.8) | 650 | 9.4 (7.8–10.9) | 870 |

| Vision impairments | 13.6 (13.0–14.3) | 10,444 | 10.0 (8.5–11.6) | 1,049 | 58.0 (51.4–64.6) | 576 | 11.1 (9.2–13.0) | 659 |

| Obesity | 25.3 (24.3–26.3) | 18,492 | 5.1 (4.3–6.0) | 947 | 65.9 (59.9–71.9) | 593 | 7.5 (6.0–9.0) | 724 |

| Diabetes | 14.7 (13.9–15.4) | 11,239 | 7.0 (5.7–8.4) | 792 | 57.5 (50.0–65.1) | 435 | 10.1 (8.0–12.1) | 583 |

| Respiratory conditions | 14.6 (13.9–15.3) | 11,174 | 6.7 (5.4–7.9) | 743 | 55.9 (48.0–63.7) | 399 | 9.2 (7.4–11.0) | 562 |

| Hearing impairments | 6.7 (6.2–7.3) | 5,132 | 10.8 (8.3–13.3) | 554 | 59.7 (49.0–70.4) | 322 | 11.7 (8.7–14.8) | 343 |

| SPD§ | 3.1 (2.7–3.5) | 2,304 | 20.4 (17.6–23.2) | 469 | 75.8 (67.6–84.0) | 344 | 22.6 (19.2–25.9) | 290 |

| Stroke | 5.4 (5.0–5.9) | 4,160 | 9.1 (6.8–11.4) | 377 | 66.8 (56.4–77.1) | 244 | 10.6 (7.9–13.3) | 249 |

| Neurological conditions | 4.3 (3.8–4.7) | 3,254 | 11.3 (9.2–13.4) | 367 | 54.7 (42.9–66.4) | 195 | 11.8 (9.4–14.3) | 219 |

*Descending order of condition-associated absolute burden.

†Respondents reporting being “always or often” restricted.

‡Respondents with the specific chronic condition, plus arthritis as a comorbidity.

§SPD: serious psychological distress, as measured by the Kessler 6 scale.

3.3. Community PR

Among all adults ≥50 years, the prevalence of any community PR was 3.6% (3.2–3.9). Among adults with chronic conditions, the overall prevalence of any community PR ranged from 5.1% (4.3–6.0) for obesity to 20.4% (17.6–23.2) for SPD (Table 2).

3.4. Condition-Associated Absolute Burden of Community PR

Respondents with the most prevalent conditions (hypertension and arthritis) reported among the lowest proportion of any community PR, 5.3% and 6.4%, respectively (Table 2). The highest prevalence of community PR overall was among respondents with SPD (20.4%), followed by neurological conditions, hearing or vision impairments, and depression/anxiety (Table 2). However, due to the relatively low prevalence of these conditions, only depression/anxiety and vision impairments were among the top five conditions with the greatest condition-associated absolute burden of community PR. In absolute numbers, the greatest condition-associated burden was among people with arthritis, affecting 1.9 million adults ≥50 years (Table 2). The remaining top five conditions in terms of absolute numbers of condition-associated burden of community PR were, in order of magnitude, hypertension, depression/anxiety, heart conditions, and vision impairments.

3.5. Chronicity of Community PR

Across all conditions, more than half of those with community PR reported being restricted “always/often,” ranging from 54.7% for neurological conditions to 75.8% for SPD (Table 2). Approximately two-thirds of respondents with community PR and stroke, obesity, or depression/anxiety reported restriction “always/often” (Table 2). Similar to condition-associated absolute burden, despite the lower prevalence of being “always/often” restricted, those with arthritis had the greatest disease burden in absolute numbers (~1.1 million), followed by hypertension (961,000) (Table 2).

3.6. Arthritis as a Comorbidity

The presence of arthritis as a comorbidity resulted in significantly higher community PR for respondents with hypertension (7.8 versus 5.3), heart conditions (9.4 versus 6.7), and obesity (7.5 versus 5.1) (Table 2). Despite the lack of significance for arthritis comorbidity in the remaining conditions, there was pattern of higher community PR for every condition examined; arthritis seemed to result in greater prevalence of community PR by 2-3% across conditions (Table 2).

3.7. Community Barriers

Respondents with SPD reported the highest prevalence of any accessibility (13.9%), any mobility (16.8%), and attitudes of others (8.5%) barriers (Table 3). Report of any accessibility barrier ranged from 3.4% for obesity (2.7–4.2) and hypertension (2.9–3.9) to 13.9% (11.6–16.2) for SPD. The prevalence of any mobility barrier ranged from 3.6% (2.9–4.3) for obesity to 16.8% (14.2–19.5) for SPD. Attitudes of others barriers were less frequent, ranging from 1.1% (0.8–1.4) for hypertension to 8.5% (6.6–10.4) for SPD (Table 3).

Table 3.

Weighted prevalence % (95% CI) of community barriers among adults ≥50 years with selected chronic conditions, 2002.*

| Accessibility barriers | Mobility barriers | Attitude barriers | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n in 1,000s | Any accessibility barrier | Building design | Lighting | Sound | n in 1,000s | Any mobility barrier | Sidewalks/curbs | Crowds | Transportation | Attitudes of others | |

| Arthritis | 1,262 | 4.2 (3.5–4.8) | 3.2 (2.6–3.7) | 1.0 (0.7–1.3) | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 1,336 | 4.4 (3.8–5.1) | 2.0 (1.5–2.4) | 2.1 (1.7–2.6) | 1.7 (1.3–2.1) | 1.3 (0.9–1.6) |

| Hypertension | 1,149 | 3.4 (2.9–3.9) | 2.5 (2.0–2.9) | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) | 1,238 | 3.7 (3.1–4.2) | 1.8 (1.4–2.2) | 1.6 (1.2–2.0) | 1.5 (1.1–1.8) | 1.1 (0.8–1.4) |

| Depression/anxiety | 788 | 6.0 (4.9–7.1) | 4.2 (3.2–5.1) | 1.6 (1.0–2.1) | 1.9 (1.3–2.6) | 971 | 7.3 (6.1–8.6) | 4.1 (3.2–5.1) | 2.7 (2.0–3.4) | 3.0 (2.2–3.9) | 2.9 (2.0–3.7) |

| Heart conditions | 744 | 4.4 (3.6–5.1) | 2.9 (2.3–3.5) | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | 1.4 (0.9–1.9) | 793 | 4.7 (3.8–5.5) | 2.2 (1.6–2.9) | 2.0 (1.5–2.5) | 1.8 (1.2–2.3) | 1.4 (0.9–1.9) |

| Vision impairments | 725 | 6.9 (5.7–8.1) | 4.9 (3.9–5.9) | 2.6 (1.8–3.3) | 1.8 (1.1–2.5) | 758 | 7.3 (6.0–8.5) | 3.5 (2.5–4.4) | 3.4 (2.7–4.2) | 3.3 (2.4–4.2) | 2.3 (1.5–3.1) |

| Obesity | 637 | 3.4 (2.7–4.2) | 2.7 (2.0–3.3) | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) | 0.6 (0.3–1.0)† | 664 | 3.6 (2.9–4.3) | 1.7 (1.2–2.2) | 1.7 (1.3–2.2) | 1.5 (1.0–2.0) | 1.2 (0.7–1.7)† |

| Diabetes | 560 | 5.0 (3.9–6.1) | 3.6 (2.6–4.6) | 1.5 (0.9–2.1) | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 516 | 4.6 (3.6–5.6) | 2.1 (1.4–2.7) | 2.2 (1.5–2.8) | 2.1 (1.5–2.8) | 1.3 (0.7–1.9)† |

| Respiratory conditions | 453 | 4.1 (3.1–5.0) | 2.9 (2.1–3.7) | 1.0 (0.5–1.5)† | 1.0 (0.5–1.6)† | 507 | 4.5 (3.5–5.5) | 2.2 (1.4–3.0) | 1.8 (1.1–2.4) | 1.9 (1.3–2.7) | 1.2 (0.7–1.7)† |

| Hearing impairments | 365 | 7.1 (5.1–9.1) | 3.4 (2.0–4.7)† | 1.9 (0.9–3.0)† | 4.1 (2.4–5.9)† | 390 | 7.6 (5.4–9.8) | 3.9 (2.2–5.7)† | 2.6 (1.6–3.6) | 3.1 (1.7–4.5)† | ‡ |

| SPD§ | 320 | 13.9 (11.6–16.2) | 8.6 (6.3–10.8) | 3.3 (1.9–4.6)† | 7.4 (5.8–9.0) | 388 | 16.8 (14.2–19.5) | 11.8 (9.6–14.0) | 6.6 (4.4–8.8) | 5.5 (4.3–6.6) | 8.5 (6.6–10.4) |

| Stroke | 251 | 6.0 (4.2–7.9) | 4.1 (2.6–5.7) | 2.5 (1.1–3.9)† | 1.5 (0.7–2.3) | 266 | 6.4 (4.5–8.3) | 2.6 (1.7–3.5) | 3.0 (1.7–4.3)† | 3.5 (2.2–4.7) | 1.8 (0.9–2.6)† |

| Neurological conditions | 273 | 8.4 (6.5–10.2) | 6.2 (4.5–8.0) | 2.3 (1.0–3.7)† | 2.2 (1.3–3.0) | 299 | 9.2 (7.3–11.1) | 5.5 (3.8–7.1) | 5.2 (3.6–6.8) | 3.9 (2.1–5.6)† | 2.9 (1.6–4.2)† |

*Descending order of condition-associated absolute burden from Table 2.

†Estimate is potentially unreliable, relative standard error (RSE) between 20.0% and 30.0%.

‡Estimate is unstable, RSE ≥ 30.0%.

§SPD: serious psychological distress, as measured by the Kessler 6 scale.

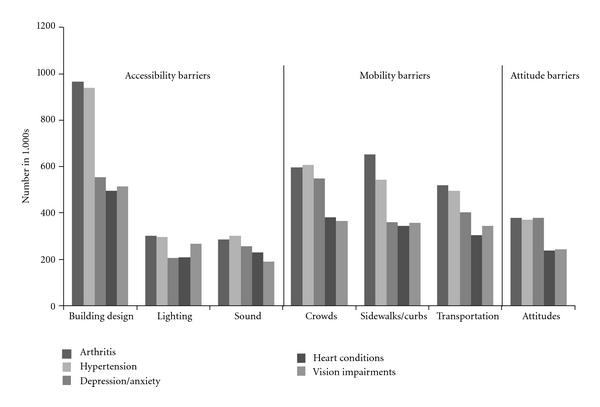

Although the frequency of accessibility barriers was the same as mobility barriers across conditions, the absolute number of people with mobility barriers was greater for all conditions except diabetes (Table 3; Figure 2). Among those with accessibility barriers, building design (2.5–8.6%) was reported significantly more often than either lighting (0.8–3.3%) or sound (0.9–7.4%) for all conditions, with the exceptions of hearing impairments, SPD, and stroke (Table 3). Within mobility barriers, there were no significant differences in the prevalence of any of the three components, with the exception that respondents with SPD reported crowds as a barrier significantly more often than those with other conditions (Table 3). Among the top five chronic conditions with the greatest condition-associated absolute burden of community PR (arthritis, hypertension, depression/anxiety, heart conditions, and vision impairments), the absolute numbers of those with mobility barriers were greater than accessibility barriers (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Environmental barriers among the top 5 most common chronic conditions.

3.8. Environmental Barriers to Community Participation among the Top 5 Most Common Chronic Conditions

Within accessibility barrier components, building design was reported with the greatest frequency across all 5 conditions and was highest among those with arthritis (Figure 2). Within mobility barriers, the category sidewalks/curbs was reported by more people than either crowds or transportation among respondents with arthritis (Figure 2). For the remaining top five conditions, crowds were cited by the greatest number (Figure 2). Overall, attitude barriers were cited more often than either lighting or sound and were highest among those with arthritis, hypertension, and depression/anxiety (Figure 2).

3.9. Comorbidity Count

The prevalence of community PR rose with increasing number of chronic conditions, ranging from 0.6% (0.2–0.9) for zero chronic conditions to 13.0% (10.8–15.2) for ≥5 chronic conditions (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Prevalence of community participation restriction, by number of chronic conditions, 2002.

4. Discussion

This study is a novel examination of community PR in older adults with chronic conditions. Several important messages emerged from the findings. First, individuals with low-prevalence conditions (e.g., SPD, neurological conditions, and stroke) reported high community PR. Second, highly prevalent conditions (e.g., arthritis, and hypertension) had relatively low community PR but resulted in the greatest absolute numbers of condition-associated burden. Third, the presence of comorbid conditions had a significant effect, resulting in greater community PR as the number of conditions increased. Finally, the most frequently reported barriers were building design, sidewalks/curbs, and crowds.

Studies of participation in older adults demonstrate that PR is associated with several health, disability, demographic, and socioeconomic characteristics as well as suggesting discordance between physical limitations and PR [2, 5, 32, 33]. It is also well-established that functional limitations are associated with chronic conditions, older age, increased health care expenditures, and lower quality of life [34, 35]. This paper extends the literature through the examination of selected chronic conditions, as single and comorbid conditions, with associated community PR and specific environmental barriers.

Stroke and vision and hearing impairments were associated with high levels of community PR as expected; alternatively, respondents with arthritis reported among the lowest prevalence of community PR. Surprisingly, obesity was associated with low levels of community PR, despite cross-sectional and longitudinal studies consistently showing declining mobility in tandem with increasing adiposity in older adults [36].

Large condition-associated absolute burden was expected and observed with arthritis. Also, higher prevalence of community PR among respondents with arthritis comorbidity was consistent with a priori expectations. Arthritis has been shown to increase levels of physical inactivity among adults with heart disease [37] and diabetes [38], as well as being linked to negative physical and mental health outcomes, including increased activity limitation [35, 39], work limitation [40], frequent mental distress [41], and serious psychological distress [42].

There is consistent evidence in the literature that absent or poorly maintained sidewalks, lack of access to transportation, and heavy motor vehicle traffic [43–45] have negative impacts on mobility in older adults. For example, Clarke et al. found that adults with severe lower extremity physical impairments who lived in neighborhoods with fair/poor streets were 4.5 times more likely to report severe mobility disability than those living in neighborhoods with streets free from cracks, potholes, and broken curbs [11]. Also, a recent US study estimated that each year more than 9,000 older pedestrian fall-related injuries involve a curb [46]. Our findings regarding sidewalks/curbs and transportation as barriers support these known associations. Attitudes of the public [44] and “other persons' rudeness” [47] have also been identified as community barriers in other studies; in these studies, as in ours, physical barriers were more frequently reported by respondents. Participants in a Meyers et al. study also cited religious buildings, friends' or relatives' houses, restaurants, and other places for recreation or leisure as destinations participants, particularly those ≥50, wanted to but were unable to reach, suggesting these may be important destinations related to community PR in that sample as well [47].

Interestingly, there were insufficient responses from survey participants to create reliable estimates regarding policy barriers to community PR. This may reflect that, while community dwelling older adults in the USA do not report encountering policies that explicitly limit their community participation, these same adults may not be aware of or recognize that policy changes could facilitate their ability to maintain community participation [11, 13, 44, 45, 48–50]. As described in the Disablement Process [48] and the ICF [1], intervening factors of the physical environment, which can be influenced by policy, “speed-up and slow-down” disablement in the presence of functional limitations. A growing literature links environmental barriers to PR, particularly among older adults [5, 10, 11, 13, 49–51]. Many of these studies simultaneously reinforce that “for those adults at greatest risk for disability, the disablement process could be reversed or attenuated” [11, 48] through policy-supported efforts to improve community infrastructure, such as sidewalk repairs, creating greener street environments, removing obstacles, and adding or maintaining street lighting, which can assist individuals with impairments to remain engaged in their communities [10, 11, 13, 50].

Among the features consistently associated with greater community mobility are intact pavement [11, 45], greater land use density [45, 49, 52], greater land use diversity [13, 45, 49], and shorter distance to nonresidential destinations [45, 49]. In a study examining neighborhood design and walkability, Frank et al. reported that “walking levels could increase 2-fold if older adults had access to multiple destinations within short distances” [49], and Li and colleagues found a positive relationship between housing density, green and open spaces, number of nearby recreational facilities, and number of street intersections, among other features, and walking activity in older adults [52]. Based on these and other findings, Saelens and Handy concluded that “evidence on correlates appears sufficient to support policy changes” and recommended efforts related to land use patterns and transportation systems [45]. Regulatory and fiscal policies that affect zoning codes, land use development, street networks, housing density, intersection characteristics (e.g., cross walks, safety islands, and countdown timers), and city planning have also been recommended as important opportunities to reduce barriers in the built environment [43, 45, 46, 49, 53]. Based on a comparative study of the USA, The Netherlands, and Germany, Pucher and Dijkstra recommended that policies to improve urban design, support traffic calming, and provide better pedestrian facilities could be applied in the USA to increase walking safety [54]. The potential decrease in community barriers and community PR offered by policy change is important because even small environmental changes can postpone, reverse, and possibly prevent disability in vulnerable older adults (e.g., those with chronic conditions or functional limitations) [1, 8, 10, 11, 13, 44, 46–50, 52, 53, 55, 56]. Furthermore, changes to improve the built environment for older adults could benefit community members of all ages [10, 45, 46, 54].

This study is subject to at least four limitations. First, data were from survey participants' self-reports and may be subject to recall bias, although such self-reports are considered valid for surveillance purposes [57]. Second, cross-sectional data cannot be used to infer causation; therefore, we cannot determine the temporal sequencing of the chronic conditions and community PR. Third, there was limited statistical power to examine sex and race/ethnicity differences. Previous literature suggests that disability may be experienced or perceived differently by men and women [12, 14], and future studies with the ability to examine these possible differences are warranted. Finally, the list of potential barriers shown to respondents to identify community PR was not exhaustive. There could be additional environmental and other barriers that result in community PR; therefore, our findings may underestimate community PR among older adults.

Strengths of this study include a large sample with simultaneously available data on both community PR and a substantial number of chronic conditions that allowed us to generate nationally representative estimates for older adults. Additionally, “accessibility,” “mobility,” and “attitude” barriers are self-reported, individual-level rather than community-level variables, reflecting individuals' perceptions and experiences of barriers in their environments. Finally, establishment of a condition-associated absolute burden measure that describes the impact of arthritis and other chronic conditions on community PR can be used to target and leverage resources and interventions for the greatest population effect.

5. Conclusion

Millions of older adults experience community PR due to modifiable environmental characteristics, especially accessibility and mobility barriers. Given the rapid growth of the older population and the high prevalence of arthritis in this population [58], the burden of arthritis will likely continue to be the largest among the conditions studied. Furthermore, arthritis prevalence is projected to increase by an estimated 19 million Americans by 2030 and is already the most common cause of disability among older adults [28, 58]. Assuming that the current prevalence of community PR due to modifiable environmental barriers remains constant, given the aging of the population and the projected increase in arthritis prevalence, our findings suggest that increasing numbers of adults ≥50 years with arthritis will experience PR due to modifiable environmental characteristics. Moreover, many of these environmental features are barriers to older adults with other chronic conditions and are demonstrated to further limit people with comorbid conditions. Promising targets to reduce community PR among adults ≥50 years with chronic conditions, particularly arthritis, include building design, sidewalks/curbs, crowd control, and interventions that improve the built environment.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilkie R, Peat G, Thomas E, Croft P. Factors associated with restricted mobility outside the home in community-dwelling adults ages fifty years and older with knee pain: an example of use of the international classification of functioning to investigate participation restriction. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2007;57(8):1381–1389. doi: 10.1002/art.23083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hawker GA, Gignac MAM. How meaningful is our evaluation of meaningful change in osteoarthritis? Journal of Rheumatology. 2006;33(4):639–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katz P, Morris A, Gregorich S, et al. Valued life activity disability played a significant role in self-rated health among adults with chronic health conditions. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2009;62(2):158–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anaby D, Miller WC, Eng JJ, Jarus T, Noreau L. Can personal and environmental factors explain participation of older adults? Disability and Rehabilitation. 2009;31(15):1275–1282. doi: 10.1080/09638280802572940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sachs D, Josman N. The activity card sort: a factor analysis. Occupation, Participation and Health. 2003;23(4):165–174. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edward D, Christiansen C. Occupational development. In: Christiansen C, Baum CM, editors. Occupational Theraphy: Performance, Participation and Well-Being. Thorofare, NJ, USA: Slack; 2005. pp. 42–63. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilkie R, Thomas E, Mottram S, Peat G, Croft P. Onset and persistence of person-perceived participation restriction in older adults: a 3-year follow-up study in the general population. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2008;6, article 92 doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rejeski WJ, Ip EH, Marsh AP, Miller ME, Farmer DF. Measuring disability in older adults: the international classification system of functioning, disability and health (ICF) framework. Geriatrics and Gerontology International. 2008;8(1):48–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2008.00446.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crews DE, Zavotka S. Aging, disability, and frailty: implications for universal design. Journal of Physiological Anthropology. 2006;25(1):113–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clarke P, Ailshire JA, Bader M, Morenoff JD, House JS. Mobility disability and the urban built environment. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;168(5):506–513. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manton KG. Epidemiological, demographic, and social correlates of disability among the elderly. Milbank Quarterly. 1989;67(supplement 2, part 1):13–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarke P, George LK. The role of the built environment in the disablement process. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(11):1933–1939. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freedman VA, Grafova IB, Schoeni RF, Rogowski J. Neighborhoods and disability in later life. Social Science and Medicine. 2008;66(11):2253–2267. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Banerjee D, Perry M, Tran D, Arafat R. Self-reported health, functional status and chronic disease in community dwelling older adults: untangling the role of demographics. Journal of Community Health. 2010;35(2):135–141. doi: 10.1007/s10900-009-9208-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dalle Carbonare L, Maggi S, Noale M, et al. Physical disability and depressive symptomatology in an elderly population: a complex relationship. The Italian Longitudinal Study of Aging (ILSA) American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2009;17(2):144–154. doi: 10.1097/jgp.0b013e31818af817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCurry SM, Gibbons LE, Bond GE, et al. Older adults and functional decline: a cross-cultural comparison. International Psychogeriatrics. 2002;14(2):161–179. doi: 10.1017/s1041610202008360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leveille SG. Musculoskeletal aging. Current Opinion in Rheumatology. 2004;16(2):114–118. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200403000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verbrugge LM, Juarez L. Profile of arthritis disability. Public Health Reports. 2001;116(supplement 1):157–179. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.S1.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parmelee PA, Harralson TL, Smith LA, Schumacher HR. Necessary and discretionary activities in knee osteoarthritis: do they mediate the pain-depression relationship? Pain Medicine. 2007;8(5):449–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ling SM, Xue QL, Simonsick EM, et al. Transitions to mobility difficulty associated with lower extremity osteoarthritis in high functioning older women: longitudinal data from the Women’s Health and Aging Study II. Arthritis Care and Research. 2006;55(2):256–263. doi: 10.1002/art.21858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verbrugge LM, Patrick DL. Seven chronic conditions: their impact on US adults’ activity levels and use of medical services. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85(2):173–182. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.2.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kempen GIJM, Verbrugge LM, Merrill SS, Ormel J. The impact of multiple impairments on disability in community-dwelling older people. Age and Ageing. 1998;27(5):595–604. doi: 10.1093/ageing/27.5.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Botman SL, et al. Design and estimation for the national health interview survey, 1995–2004. Vital and Health Statistics. 2000;(130) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010. With Understanding and Improving Health and Objectives for Improving Health. 2nd edition. 1-2. Washington, D.C, USA: Government Printing Office; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Center for Health Statistics. Data File Documentation, National Health Interview Survey, 2002 (Machine Readable Data File and Documentation) Hyattsville, Md, USA: National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32(6):959–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brault MW, et al. Prevalence and most common causes of disability among adults, United States, 2005. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2009;58(16):421–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.SAS Institute. SAS/STAT User's Guide. Version 9. Cary, NC, USA: SAS Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Research Trianle Institute. SUDAAN Language Manual. Research Triangle Park, NC, USA: Research Trianle Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klein RJ, Proctor SE, Boudreault MA, Turczyn KM. Healthy People 2010 criteria for data suppression. Healthy People 2010 Statistical Notes. 2002;(24):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mars GMJ, Kempen GIJM, Mesters I, Proot IM, van Eijk JTM. Characteristics of social participation as defined by older adults with a chronic physical illness. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2008;30(17):1298–1308. doi: 10.1080/09638280701623554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilkie R, Peat G, Thomas E, Croft P. Factors associated with participation restriction in community-dwelling adults aged 50 years and over. Quality of Life Research. 2007;16(7):1147–1156. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9221-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Group TL. Individuals Living in the Community with Chronic Conditions and Functional Limitations: A Closer Look. Washington, D.C, USA: Office of the Assistance Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; United States Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freelove-Charton J, Bowles HR, Hooker S. Health-related quality of life by level of physical activity in arthritic older adults with and without activity limitations. Journal of Physical Activity & Health. 2007;4(4):481–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vincent HK, Vincent KR, Lamb KM. Obesity and mobility disability in the older adult. Obesity Reviews. 2010;11(8):568–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bolen J, et al. Arthritis as a potential barrier to physical activity among adults with heart disease—United States, 2005 and 2007. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2009;58(7):165–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bolen J, Hootman J, Helmick CG, Murphy L, Langmaid G, Caspersen CJ. Arthritis as a potential barrier to physical activity among adults with diabetes—United States, 2005 and 2007. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2008;57(18):486–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheng YJ, et al. Prevalence of doctor-diagnosed arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitation—United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2010;59(39):1261–1265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Theis KA, Murphy L, Hootman JM, Helmick CG, Yelin E. Prevalence and correlates of arthritis-attributable work limitation in the US population among persons ages 18–64: 2002 National Health Interview Survey Data. Arthritis Care and Research. 2007;57(3):355–363. doi: 10.1002/art.22622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strine TW, Hootman JM, Okoro CA, et al. Frequent mental distress status among adults with arthritis age 45 years and older, 2001. Arthritis Care and Research. 2004;51(4):533–537. doi: 10.1002/art.20530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shih M, Hootman JM, Strine TW, Chapman DP, Brady TJ. Serious psychological distress in U.S. adults with arthritis. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21(11):1160–1166. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00573.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clarke P, Ailshire JA, Lantz P. Urban built environments and trajectories of mobility disability: findings from a national sample of community-dwelling american adults (1986–2001) Social Science and Medicine. 2009;69(6):964–970. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.06.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kirchner CE, Gerber EG, Smith BC. Designed to deter. Community barriers to physical activity for people with visual or motor impairments. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;34(4):349–352. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saelens BE, Handy SL. Built environment correlates of walking: a review. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2008;40(supplement 7):S550–S566. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31817c67a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Naumann RB, Dellinger AM, Haileyesus T, Ryan GW. Older adult pedestrian injuries in the United States: causes and contributing circumstances. International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion. 2011;18(1):65–73. doi: 10.1080/17457300.2010.517321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meyers AR, Anderson JJ, Miller DR, Shipp K, Hoenig H. Barriers, facilitators, and access for wheelchair users: substantive and methodologic lessons from a pilot study of environmental effects. Social Science and Medicine. 2002;55(8):1435–1446. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00269-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verbrugge LM, Jette AM. The disablement process. Social Science and Medicine. 1994;38(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90294-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frank L, Kerr J, Rosenberg D, King A. Healthy aging and where you live: community design relationships with physical activity and body weight in older Americans. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2010;7(supplement 1):S82–S90. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.s1.s82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beard JR, Blaney S, Cerda M, et al. Neighborhood characteristics and disability in older adults. Journals of Gerontology, Series B. 2009;64(2):252–257. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbn018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Diez Roux AV. Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(11):1783–1789. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li F, Fisher KJ, Brownson RC, Bosworth M. Multilevel modelling of built environment characteristics related to neighbourhood walking activity in older adults. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2005;59(7):558–564. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.028399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hindman D. Local-level policy can have an important effect on healthy lifestyles. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2010;7(supplement 1):S5–S6. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.s1.s5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pucher J, Dijkstra L. Promoting safe walking and cycling to improve public health: lessons from the Netherlands and Germany. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(9):1509–1516. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li W, Keegan THM, Sternfeld B, Sidney S, Quesenberry CP, Kelsey JL. Outdoor falls among middle-aged and older adults: a neglected public health problem. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(7):1192–1200. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.083055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Michael YL, Green MK, Farquhar SA. Neighborhood design and active aging. Health and Place. 2006;12(4):734–740. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nelson DE, Holtzman D, Bolen J, Stanwyck CA, Mack KA. Reliability and validity of measures from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) Sozial- und Praventivmedizin. 2001;46(supplement 1):S3–S42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hootman JM, Helmick CG. Projections of US prevalence of arthritis and associated activity limitations. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2006;54(1):226–229. doi: 10.1002/art.21562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]