Abstract

Medical therapy for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) became an accepted standard of care in the 1990s following the reports of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies showing that finasteride, a 5-α reductase inhibitor, and terazosin, an α-blocker, significantly improved lower urinary tract symptoms and increased peak urinary flow rates in men with BPH. This article reviews novel approaches to the pharmacological treatment of BPH.

Key words: Benign prostatic hyperplasia, Lower urinary tract symptoms, Monotherapy, Combination therapy

It has been long recognized that enlargement of the prostate and the development of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are age-dependent events.1 The primary cause of prostatic enlargement is benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), which involves both the stromal and epithelial elements of the prostate.2 Many postulate that the pathophysiology of LUTS in the aging male is intimately related to BPH. Therefore, during the greater part of the 20th century, the most common treatment of LUTS arising from BPH was resection or enucleation of the prostate adenoma. These surgical approaches for removing BPH tissue were highly effective at relieving LUTS and decreasing bladder outlet obstruction (BOO).3 However, in the 1980s an increasing number of urologists began to question whether the benefits of surgical intervention for BPH justified its risks, especially in men presenting only with moderate LUTS.

The development of 5-α reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs) and α-blockers were based on a simplistic concept for the pathophysiology of the disease: LUTS arose from BOO which in turn arose from benign prostatic enlargement (BPE).4 5-ARIs and α-blockers targeted the static and dynamic (smooth muscle) components of BPH-induced BOO, respectively.

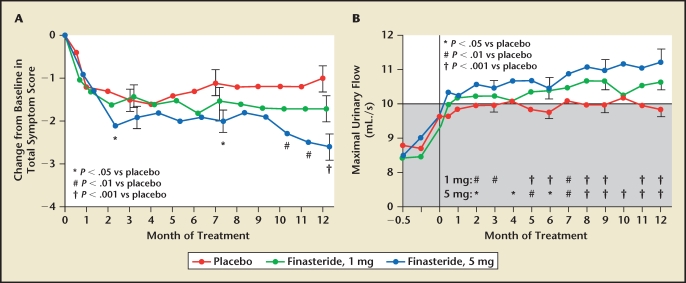

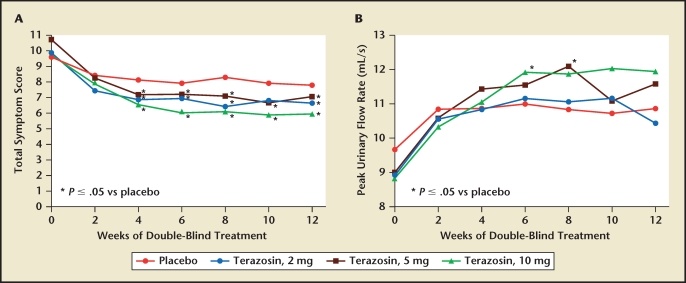

Medical therapy for the treatment of BPH became an accepted standard of care in the 1990s following the reports of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies showing that finasteride,4 a 5-ARI (Figure 1), and terazosin, an α-blocker5 (Figure 2), significantly improved LUTS and increased peak urinary flow rates in men with BPH.6

Figure 1.

Trial results comparing placebo and two dosing regimens of finasteride in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. (A) Men who received finasteride, 5 mg, had a significant decrease in symptom scores at months 2, 7, 10, 11, and 12, compared with placebo. Men who received finasteride, 1 mg, had no significant change in symptom scores. (B) At 6 and 12 months, the maximal flow rates in both finasteride-treated groups were significantly higher than baseline values and rates of the placebo group. Shaded area indicates range in which urinary flow was considered to be obstructed. Reproduced with permission from Gormley GJ et al, N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1185–1191. © Massachusetts Medical Society.

Figure 2.

Trial results comparing placebo and three dosing regimens of terazosin in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. The effects of terazosin on (A) American Urological Association symptom score and (B) peak urinary flow rate were found to be dose dependent. Reproduced with permission from Lepor H et al, J Urol. 1992;148:1467–1474.5

Over the following two decades, numerous randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials have confirmed the effectiveness of two 5-ARIs (finasteride and dutasteride) and five α-blockers (terazosin, doxazosin, tamsulosin, alfuzosin, and silodosin).7 All of these drugs were subsequently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of BPH. Although dutasteride achieves a more complete suppression of dihydrotestosterone (DHT) production because it is a dual inhibitor of the enzyme 5-α reductase,8 there appears to be no clinical advantage over finasteride for the treatment of BPH.9 The evolution of α-blockers has been toward the development of longer-acting and subtype-selective agents, resulting in easier dosing regimens and reduced side effects while maintaining effectiveness.10

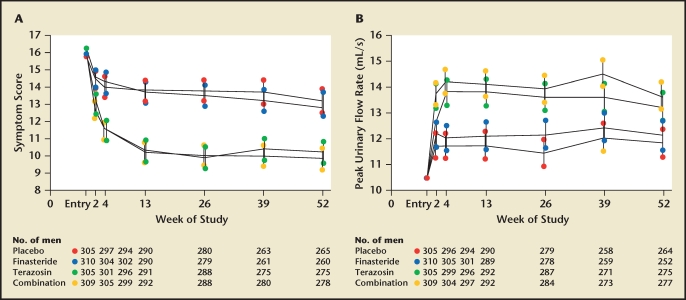

The relative effectiveness of 5-ARIs and α-blockers was first investigated in the mid-1990s by the Veterans Affairs (VA) Cooperative Studies Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Study Group.11 A total of 1229 men with symptomatic BPH were randomized to receive terazosin, finasteride, the combination of terazosin and finasteride, or placebo for 1 year. The effectiveness of the treatment groups was captured by improvements in the American Urological Association sympton score (AUASS) and peak flow rates. The observed efficacy of terazosin in the VA study was similar to previous reports, whereas the effectiveness of finasteride was observed to be no greater than placebo (Figure 3). Combination therapy was observed to be no more effective than terazosin monotherapy because finasteride was of no clinical benefit relative to placebo. The primary difference between the study design of the VA trial and the finasteride registration study12 was that the VA study enrolled all men with BPH, whereas the finasteride registration study enrolled a disproportionate percentage of men with very large prostates, the subset most likely to respond to a drug whose mechanism of action is to reduce prostate size. Specifically, the mean prostate volume in the VA trial was 37 cm3 compared with 58.6 cm3 in the finasteride registration study. Therefore, the findings of the VA study reflect the effectiveness of the evaluated medical therapies for all men with clinical BPH, whereas the findings of the finasteride registration study are relevant only to the subset of men with clinical BPH and large prostates.

Figure 3.

Comparison of finasteride, terazosin, and combined dosing regimens for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Symptom scores and flow rates are expressed as adjusted means and 95% confidence intervals. (A) American Urological Association symptom scores, according to treatment group. Symptom scores of subjects who received terazosin or combination therapy were significantly lower from baseline, as well as from those in the placebo and finasteride groups, at all follow-up visits. (B) Mean peak urinary flow rates were significantly higher in the terazosin and combination therapy groups than in the placebo and finasteride groups at all follow-up visits. Reproduced with permission from Lepor H et al, N Engl J Med. 1996;335:533–539. © Massachusetts Medical Society.11

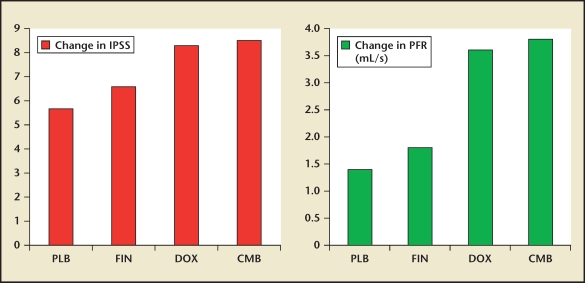

The findings of the VA study were replicated by the PREDICT13 study, which substituted the α-blocker doxazosin for terazosin. Again, the doxazosin was significantly more effective than placebo at relieving LUTS and increasing peak urinary flow rate, and finasteride was no more effective than placebo; there was no benefit of combination therapy over α-blocker monotherapy (Figure 4). In the PREDICT study, the baseline prostate volume was 36 g, which is virtually identical to the VA study.

Figure 4.

The mean changes in International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) score and peak flow rate (PFR) between baseline and 1 year of active treatment of men randomized to placebo (PLB) and finasteride (FIN), doxazosin (DOX), or a finasteride + doxazosin (CMB) in the PREDICT study. Data from Kirby et al.13

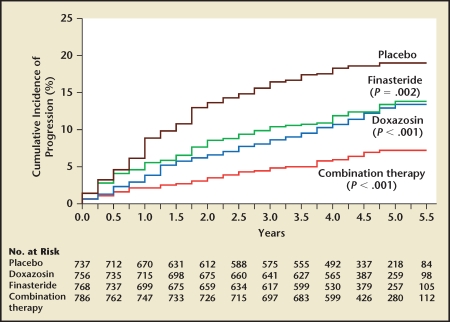

The VA and PREDICT studies were designed to examine the relative effectiveness of α-blockers, 5-ARIs, and the combination of these two classes of drugs for improving LUTS and BOO over a 1-year period. The Medical Therapy of Prostatic Symptoms (MTOPS) study was designed primarily to address disease progression. MTOPS examined the ability of a 5-ARI (finasteride), an α-blocker (doxazosin), and the combination of these two classes of drugs (finasteride and doxazosin) to prevent disease progression relative to placebo.14 In this randomized, placebo-controlled study enrolling 3047 men with clinical BPH, the primary endpoint was clinical BPH progression and the secondary endpoints were changes in LUTS and peak urinary flow rate. Clinical BPH progression was defined as a four-point increase in AUASS or development of acute urinary retention (AUR), renal insufficiency, urinary tract infection (UTI), or incontinence. The requirement for invasive therapy due to BPH was also captured. With a mean follow-up of 4.5 years, all treatment groups significantly decreased overall disease progression relative to placebo (Figure 5). Combination therapy was significantly more effective than monotherapy at preventing overall disease progression. In this study, progression of LUTS and development of AUR were the factors accounting for the overwhelming majority of disease progression events. In the placebo group, 80% and 15% of the events contributing to overall clinical progression were attributable to symptom progression and the development of AUR, respectively (Table 1). Doxazosin and finasteride were equally effective at preventing LUTS progression, whereas finasteride was significantly more effective than doxazosin at preventing AUR. Although the risk reduction rate for preventing AUR in the combination group relative to placebo was 81%, only 18 men developed AUR in the placebo group (Table 1). Due to the infrequent development of incontinence, renal insufficiency, and UTI/renal insufficiency, Table 2 highlights only the effect of the MTOPS active treatment arms to prevent overall clinical BPH progression, symptom progression, development of UTI, and invasive therapy of BPH. The numbers needed to treat to prevent these events are also presented in Table 2, and put the risk reductions in perspective. The observed 66%, 64%, 81%, and 67% risk reduction of combination therapy for overall clinical BPH progression, symptom progression, development of AUR, and progression to invasive therapy of BPH, respectively, has been used to justify combination therapy. Overall, 786 men were treated with combination therapy over a mean follow-up of 4.5 years to prevent 61, 14, and 25 symptom progression events, episodes of AUR, and invasive therapies for BPH, respectively. This translates into a need to treat 12, 56, and 29 men with clinical BPH for a mean of 4.5 years to prevent a single man from developing symptom progression, AUR, or having invasive therapy for BPH. At 4 years, the overall median change in AUASS in the doxazosin group was significantly greater than finasteride. Invasive therapy was neither a primary nor secondary endpoint. If one assumes that an α-blocker is administered as the first-line treatment of symptomatic BPH based on the VA and PREDICT studies, then the addition of finasteride prevented 21, 5, and 14 symptom progression events, episodes of AUR, and invasive therapies for BPH, respectively. This translates to the need to treat 36, 151, and 54 men with combination therapy to prevent a single man on an α-blocker from developing symptom progression, AUR, or having invasive treatment of BPH, respectively. Throughout the study, both the α-blocker and combination therapy groups exhibited significantly greater improvement in LUTS, confirming the short- and long-term superiority of α-blockers over 5-ARIs for LUTS improvement.

Figure 5.

Cumulative incidence of progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Progression was defined by an increase of at least 4 points over baseline in the American Urological Association symptom score, acute urinary retention, urinary incontinence, renal insufficiency, or recurrent urinary tract infection. P values are for the comparison with placebo. Reproduced with permission from McConnell JD et al, N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2387–2398. © Massachusetts Medical Society.14

Table 1.

Clinical Progression in the MTOPS Treatment Groups

| Number (%) of Events | ||||

| Combination | ||||

| Doxazosin and | ||||

| Placebo | Doxazosin | Finasteride | Finasteride | |

| Endpoint | (n = 737) | (n = 756) | (n = 768) | (n = 786) |

| 4-point ↑ IPSS | 97 (14) | 55 (7) | 65 (9) | 36 (5) |

| AUR | 18 (2) | 9 (1) | 6 (< 1) | 4 (< 1) |

| Incontinence | 6 (< 1) | 7 (< 1) | 7 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) |

| UTI/urosepsis | 1 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 0 | 1 (< 1) |

| Invasive therapy due to BPH | 37 (5) | 26 (3) | 14 (2) | 12 (1) |

AUR, acute urinary retention; BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; IPSS, International Prostate Symptom Score; MTOPS, Medical Therapy of Prostatic Symptoms; UTI, urinary tract infection. Data from McConnell JD et al.14

Table 2.

Clinical Progression of BPH in the MTOPS Trial

| Risk Reduction (95% CI) | ||||

| Combination | ||||

| Doxazosin and | ||||

| Placebo | Doxazosin | Finasteride | Finasteride | |

| Endpoint | (n = 737) | (n = 756) | (n = 768) | (n = 786) |

| Clinical progression of BPH | − | 39 (20–53) | 34 (14–50) | 66 (54–76) |

| ≥ 4-point ↑ IPSS | − | 45 (25–60) | 30 (6–48) | 64 (48–75) |

| AUR | − | 35 (−31–67) | 68 (21–87) | 81 (44–93) |

| Invasive therapy due to BPH | − | 3 (−48–37) | 64 (34–80) | 67 (40–82) |

AUR, acute urinary retention; BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; CI, confidence interval; IPSS, International Prostate Symptom Score; MTOPS, Medical Therapy of Prostatic Symptoms. Data from McConnell JD et al.14

Like MTOPS, the Combination of Avodart and Tamsulosin (CombAT) study compared the effectiveness of the 5-ARI dutasteride, the α-blocker tamsulosin, and the combination of these drugs over 4 years of active treatment.15 The primary endpoint of the CombAT study was time to develop AUR or have BPH-related surgery. Many secondary endpoints were also evaluated, including time to overall BPH clinical progression, which included the same progression endpoints as the MTOPS study, percentage of subjects exhibiting a larger than three-point improvement in International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), and changes in maximum urinary flow rate. A total of 4844 men with prostate volumes > 30 cm3 and clinical evidence of symptomatic BPH were randomized in equal proportions to doxazosin, dutasteride, or combination treatment and followed for 4 years. The CombAT study markedly deviated from the MTOPS trial (Table 3). First, the CombAT trial was sponsored and funded solely by the pharmaceutical company marketing the 5-ARI under investigation (dutasteride), whereas the MTOPS study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Unlike MTOPS, the CombAT study lacked a placebo arm, the selection criteria was designed to enroll men with large prostates, and the primary endpoint was time to AUR or BPH-related surgery instead of overall BPH clinical progression (Table 3). It is readily apparent that the study design favored the 5-ARI arms because the selection criteria were designed to enroll men with large prostates and the disease progression primary endpoint was restricted to the two progression endpoints that were superior in the 5-ARI arm of the MTOPS trial relative to the α-blocker arm. It is important to emphasize that the mean prostate volume in the CombAT study was almost 70% greater than the MTOPS study. Unlike MTOPS, the CombAT study demonstrated that the effect of tamsulosin and dutasteride on IPSS and maximum urinary flow rate were not significantly different and that combination therapy was significantly more effective than monotherapy at improving these secondary endpoints (Table 4). Combination therapy and dutasteride monotherapy significantly reduced the risk of AUR and BPH surgery and the combined AUR/BPH surgery progression endpoint relative to tamsulosin (Table 4). The incidence of AUR was uniformly low in all treatment groups. In men with large prostates who are predisposed to develop BPH and were selected for the CombAT trial, 30 and 18 men had to be treated with combination therapy over 4 years to prevent a single man treated with an α-blocker from developing AUR or undergoing invasive BPH surgery, respectively. Symptom progression was virtually identical in the tamsulosin and dutasteride groups, whereas the combination arm was superior to monotherapy at preventing symptom progression. Due to the inherent bias of the study design, it is absolutely not surprising that the 5-ARI arm performed better than the α-blocker group as far as the heavily biased primary endpoint. The legitimate conclusion of the CombAT study is that, in a select group of men with large prostates, combination therapy and dutasteride alone are significantly better than tamsulosin at preventing AUR and BPH surgery. For all other endpoints, the effectiveness of monotherapy was similar and combination therapy was superior to the monotherapy groups.

Table 3.

MTOPS Versus CombAT

| Design | MTOPS | CombAT |

| Placebo control | Yes | No |

| Selection criteria for | No | Yes |

| large prostates (> 30 cm3) | ||

| Primary endpoint | Clinical BPH progression | AUR and BPH invasive |

| intervention | ||

| Funding | National Institutes of Health | GlaxoSmithKline |

AUR, acute urinary retention; BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; CombAT, Combination of Avodart and Tamsulosin; MTOPS, Medical Therapy of Prostatic Symptoms.

Table 4.

Outcomes From the CombAT Study

| Outcomes at 48 Months | Mean Change | ||

| Dutasteride | Tamsulosin | Dutasteride+ | |

| (n = 1623) | (n = 1611) | Tamsulosin | |

| (n = 1610) | |||

| Δ IPSS | −5.3 | −3.8 | −6.3 |

| % Patients Δ IPSS ≥ 25% | 61 | 52 | 67 |

| Δ PFR (mL/s) | 2.0 | 0.7 | 2.4 |

| Progression Events | Number (%) Events | ||

| Symptoms | 212 (13.1) | 229 (14.2) | 139 (8.6) |

| AUR | 37 (2.3) | 82 (5.1) | 26 (1.6) |

| BPH surgery | 56 (3.5) | 126 (7.8) | 38 (2.4) |

| Incontinence | 60 (3.7) | 65 (4.0) | 49 (3.0) |

| UTI | 5 (0.3) | 5 (0.3) | 3 (0.2) |

| Renal insufficiency | 2 (0.1) | 7 (0.4) | 1 (< 0.1) |

AUR, acute urinary retention; BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; CombAT, Combination of Avodart and Tamsulosin; IPSS, International Prostate Symptom Score; PFR, peak flow rate; UTI, urinary tract infection. Data from Roehrborn CG et al.15

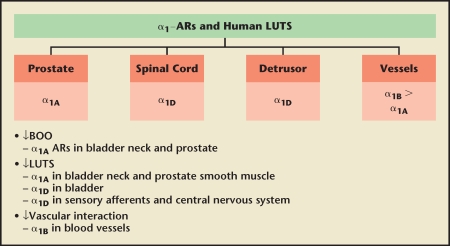

New α-Blockers

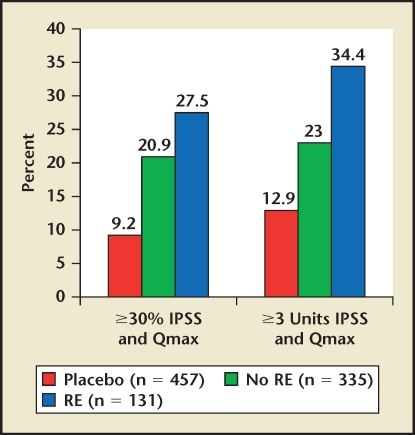

The evolution of α-blockers for the treatment of clinical BPH has involved the development of subtype-selective α-antagonists and novel formulations that ultimately allow for a single, daily-dose administration without the requirement for dose titration.10 There are three subtypes of the α1A,α1B, and α1D. The α1A- and α1B-adrenoceptor are predominant in the prostate and vasculature, respectively, whereas the α1D-adrenoceptor is present in the bladder and nerve junctions (Figure 6).16 Of all α-blockers, only silodosin exhibits any degree of α-adrenoceptor subtype selectivity that can be leveraged in the clinical setting. Silodosin exhibits very high selectivity for α1A versus α1B and modest selectivity for α1A versus α1D. If efficacy is mediated by α1A and α1D and toxicity by α1B, then silodosin has the potential for unique clinical properties. The clinical data suggest that silodosin is essentially devoid of cardiovascular side effects.17,18 On the other hand, the incidence of ejaculatory dysfunction exceeds all other α-blockers.17 Interestingly, the subset of men experiencing ejaculatory dysfunction experiences the greatest efficacy (Figure 7).19 Therefore, the utility of silodosin in the treatment of BPH must balance maximizing effectiveness, limiting cardiovascular side effects, and preventing ejaculatory dysfunction.

Figure 6.

New concepts in drug development of α-blockers. AR, androgen receptor; BOO, bladder outlet obstruction; LUTS, lower urinary tract symptoms. Reproduced with permission from Lepor H, Rev Urol. 2009;11 (suppl 1):S9–S13.

Figure 7.

Silodosin post hoc responder analysis by ejaculation status. Based on patient subanalysis. IPSS, International Prostate Symptom Score; RE, retrograde ejaculation. Data on file, Watson Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Corona, CA.

Novel Nonsurgical Treatment of BPH

The mechanism by which BPH causes LUTS is still poorly understood. In men with BPH, there is only a weak correlation between severity of LUTS and BOO.20 There is also a poor correlation between the improvement in LUTS and BOO in men following medical and surgical therapy of BPH.20 Thus, although the concept that BPE causes BOO leading to LUTS was the foundation for developing α-blocker and 5-ARI therapy, this is an oversimplification. There is little doubt that the prostate plays a central role in LUTS, because the majority of men experience dramatic improvement in symptoms following a transurethral or radical prostatectomy. 21 Therefore, the development of novel nonsurgical therapies does not necessarily need to target relieving BOO exclusively.

Phosphodiesterase Type 5 (PDE5) Inhibitors

Both BPH/LUTS and erectile dysfunction (ED) are conditions identified in a significant percentage of aging males. The observation that men with ED in general have greater LUTS suggests a common etiology.22 There are several mechanisms of action supporting the utility of PDE5 inhibitors for the treatment of BPH. First, nitric oxide-staining nerves are abundant in the prostate and prostate smooth muscle tension is mediated by NO.23,24 Therefore, PDE5 inhibitors were initially investigated as a means to relax prostate smooth muscle. Alternative mechanisms of action summarized by Laydner and colleagues23 include endothelin inactivation, decrease in autonomic hyperactivity, and reduction of pelvic ischemia.

PDE5 inhibitors are the primary medical treatment option for ED: they are safe, efficacious, and easily administered. 25 Among the three commonly prescribed oral PDE5 inhibitors (sildenafil, tadalafil, and vardenafil), the only meaningful difference is the duration of action of tadalafil. Whereas vardenafil and sildenafil have a duration of action of 4 hours, tadalafil is active for as long as 36 hours (T1/2 = 17.5 h). Tadalafil, 5 mg, is the only drug approved for daily administration for the treatment of ED. This feature makes tadalafil the most promising commercially available PDE5 inhibitor as a once-daily treatment of BPH/LUTS.

Initial data support the clinical benefit of PDE5 inhibitors for the treatment of LUTS secondary to BPH. Four large, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials have examined the effectiveness of sildenafil, tadalafil, and vardenafil in men with LUTS and BPH.26–29 All of the studies consistently demonstrated that this class of drugs improves LUTS in men with BPH (Table 5). On the basis of risk/benefit, daily tadalafil, 5 mg, was thought to be its preferred dose.29 None of the studies showed meaningful changes in objective indices of outlet obstruction, including uroflowmetric parameters or postvoid residual volume. This very important observation provides validation that future treatments for LUTS secondary to BPH do not need to target prostate smooth muscle relaxation or reduce prostate volume.

Table 5.

Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trials of PDE5 Inhibitors for the Treatment of Clinical BPH

| Treatment Effect |

|||||

| Reference | Drug | Dose (mg) | No. | † IPSS | † Qmax |

| McVary KT et al26 | Sildenafil | 100 | 189 | 6.3 | 0.31 |

| McVary KT et al27 | Tadalafil | 5 | 281 | 2.8 | 0.5 |

| 20 | 281 | 3.8 | 0.5 | ||

| Stief CG et al28 | Vardenafil | 10 bid | 222 | 5.9 | 1.6 |

| Roehrborn CG et al29 | Tadalafil | 5 | 212 | 4.87 | 1.64 |

BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; IPSS, International Prostate Symptom Score; PDE5, phosphodiesterase type 5.

Further investigations with PDE5 inhibitors in BPH/LUTS still need to be conducted; this includes assessments of primary treatment of BPH/LUTS in an unselected group of men with BPH, efficacy of combination treatment with an α-blocker and/or 5-ARI, and durability of effectiveness.

Intraprostatic Botulinum Toxin Type A

Botulinum toxin type A (BoNT-A) acts irreversibly at acetylcholinergic synapses to block the release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine.30 This results in decrease of target muscle tone. Injection of BoNT-A is widely used for cosmetic purposes, as well as for treatment of various conditions, including strabismus, cervical dystonia, and esophageal achalasia. Preliminary studies demonstrate durable improvements in overactive bladder (OAB) voiding symptoms after cystoscopy-guided injection.31 Based on these clinical observations, intravesical injection of BoNT-A is used offlabel for overactive bladder.

Because BoNT-A inhibits the release of acetylcholine at nerve synapses, this agent may relive LUTS secondary to BPH by decreasing smooth muscle tone, inhibiting the secretory function of the prostate, and inhibiting sensory afferents that may be mediating LUTS via unrecognized mechanisms.

Ilie and colleagues have recently summarized the clinical studies investigating BoNT-A for the treatment of LUTS/BPH.32 BoNT-A is administered using transrectal ultrasound guidance, and injection is performed transperineally, transrectally, or transurethrally. Typically administered doses vary from 100 to 300 units depending on the size of the prostate. The procedure can be performed on an outpatient basis, and there is no need for Foley catheter drainage of the bladder postprocedure.

The majority of reported BoNT-A clinical studies in men with LUTS/BPH was from small, single institutions and was not randomized or placebo controlled.32 Very impressive improvements in IPSS, peak flow rates, and prostate volume have been observed. One placebo-controlled study demonstrated statistically significant treatment differences in both IPSS and uroflowmetric parameters (Table 6).33 Follow-up studies in this same cohort demonstrated durable responses at 12 months and beyond.34

Table 6.

A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Botulinum Toxin Type A for Treatment of Clinical BPH

| Outcomes (N = 30) | Baseline | 1 Month | 2 Months |

| AUASS | |||

| BoNT-A | 23.2 | 10.6 | 8.0 |

| PLB | 23.3 | 23.4 | 23.3 |

| PFR (mL/s) | |||

| BoNT-A | 8.1 | 14.9 | 15.4 |

| PLB | 8.8 | 8.8 | 8.7 |

| Prostate volume (cm3) | |||

| BoNT-A | 52.6 | 23.8 | 16.8 |

| PLB | 52.3 | 50.5 | 50.3 |

| PVR (mL) | |||

| BoNT-A | 126.3 | 49.6 | 21 |

| PLB | 118.0 | 116.7 | 116.7 |

AUASS, American Urological Association symptom score; BoNT-A, botulinum toxin type A; BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; PFR, peak flow rate; PLB, placebo; PVR, postvoid residual volume. Data from Maria G et al.33

Like intravesical BoNT-A for OAB, intraprostatic BoNT-A is not yet approved by the FDA. Long-term safety questions, including effect on serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels and risk of prostate cancer, have yet to be answered. Intraprostatic BoNT-A may ultimately become a useful treatment in patients with BPH/LUTS refractory to oral medications, especially those who are not candidates for surgery.

Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) Antagonists

GnRH agonists reduce the volume of BPE by lowering serum and intraprostatic testosterone and dihydrotestosterone levels. This results in some modest clinical benefits related to improvements in LUTS. The primary disadvantages of GnRH agonists are their associated immediate and long-term adverse effects due to induction of castrate levels of testosterone. The initial rationale for GnRH antagonists in the treatment of BPH/LUTS was the opportunity to titrate serum testosterone to a level that would reduce prostate volume without causing adverse effects.

A small, open-label study with the GnRH antagonist cetrorelix acetate demonstrated that short-term administration of the drug was associated with long-term improvement in LUTS and decreased prostate volume.35 A phase II, randomized, placebo-controlled study in men with BPH/LUTS conducted in Eastern Europe demonstrated promising results. 36 In this study, the clinical effect of cetrorelix acetate was dose dependent. The optimal dosing regimen was cetrorelix acetate, 60 mg, administered at 26-week intervals. The improvement in IPSS and peak flow rate over placebo observed throughout the duration of the study was comparable with that observed with α-blockade. At the effective doses, cetrorelix did not appear to cause vasomotor or sexual side effects and lowered testosterone levels only transiently. Despite the fact that testosterone levels had returned to baseline within a few weeks, effectiveness continued for the 26 weeks in between the dosing of the drug.

Due to the above findings, phase III studies were conducted in the United States and Europe; in the US study, 637 men were randomized to receive either two doses of placebo or cetrorelix on weeks 2 and 26.37 Upon conclusion of the trial, the drug showed no statistically significant benefit in improving IPSS. In addition, the drug did not have a significant effect on peak flow rate or prostate volume versus placebo. It is difficult to reconcile this lack of efficacy given favorable prior results. A subsequent multicenter European trial also failed to show any treatment-related efficacy of cetrorelix.38 The experience with cetrorelix highlights the importance of randomized, placebo-controlled trials that are appropriately powered to show clinical benefit and safety.

NX-1207

NX-1207 is a new drug under investigation for the treatment of symptomatic BPH. NX-1207 has been suggested to elicit a proapoptotic effect on the prostate.39 The drug is injected directly into the prostate as a single administration. Four clinical trials yet to be published in the peer-reviewed literature have been interpreted to show improvement in LUTS exceeding that of all other medical therapies currently marketed for the treatment of BPH. NX-1207 was also reported to decrease prostate volume and increase Qmax. These clinical benefits were maintained after angle injection for a year. Phase III studies are underway to define the true efficacy, safety, and mechanism of action of this novel approach to treating BPH.

Combination Therapy

α-Blocker and 5-ARI

The VA Cooperative Trial11 and the PREDICT trial13 unequivocally demonstrated there is no observed benefit of adding a 5-ARI to an α-blocker to further decrease LUTS or increase peak urinary flow rate during the first year of treatment in unselected men with clinical BPH.

The MTOPS trial asked an entirely different clinical question than the VA Cooperative and PREDICT trials. MTOPS was the first study to examine the ability of medical therapy to prevent disease progression in a group of men with clinical BPH independent of prostate volume.14 BPH progression was defined by a 4-point increase in IPSS, development of AUR, renal insufficiency, UTI/urosepsis, or social incontinence. The need to undergo BPH surgery was not a primary endpoint, but this clinical information was captured. In this study, prevention of LUTS progression was similar in both monotherapy treatment groups, whereas the prevention of AUR was superior in the 5-ARI group. The combination arm was superior at preventing overall disease progression and progression of LUTS and AUR. A lot of emphasis has focused on the ability of combination therapy to prevent AUR. At first glance, the 81% risk reduction of AUR in the combination arm relative to placebo appears compelling and highly clinically relevant. It is important to note that in the placebo group, only 2% of the subjects developed AUR. Therefore, one had to treat 56 men with combination therapy for up to 5 years to prevent a single episode of AUR relative to placebo. If one assumes that the initial treatment of clinical BPH is an α-blocker, then the addition of a 5-ARI will prevent only one additional case of AUR for every 150 men treated with combination therapy. The cost effectiveness of this indiscriminant use of combination therapy in an unselected group of men with BPH to decrease risk of AUR or any other progression endpoint requires re-evaluation.

The CombAT trial,15 which was sponsored by the company marketing dutasteride, was cleverly designed to show an advantage of their drug over the α-blocker. Unlike the MTOPS study, the selection criteria were designed to identify men with large prostates. The selection criteria achieved the intended bias because the prostate volume in the CombAT trial was 70% greater than the MTOPS trial. The primary endpoint was progression only to AUR and BPH surgery because in the MTOPS study, only these endpoints favored the 5-ARI group. The CombAT trial simply demonstrated that, in men with large prostates, combination therapy is superior to monotherapy at preventing AUR and BPH surgery. One had to treat 30 men selected with large prostates with combination therapy for 4 years to prevent one more episode of AUR had treatment been initiated with an α-blocker alone.

Barkin and colleagues40 reported results from the Symptom Management After Reducing Therapy (SMART-1) trial in which 327 men with clinical BPH were treated with the combination of dutasteride and tamsulosin for 24 weeks followed by a randomized, placebo-controlled withdrawal of the tamsulosin for an additional 12 weeks. The inclusion criteria included a prostate volume exceeding 30 cm3. The baseline mean prostate volumes were not reported, but presumably the prostates were very large due to this minimal volume requirement. The baseline mean serum PSA level of 4.3 is higher than other 5-ARI studies and suggests an even greater propensity to enroll men with very large prostates. The primary endpoint was the individual’s perception of change in LUTS and the secondary endpoint included changes in IPSS. Overall, 23% of subjects reported worsening of LUTS when the tamsulosin was withdrawn compared with only 9% if combination therapy was maintained. Of the men with severe LUTS at baseline, 42.5% reported worsening of their symptoms once tamsulosin was withdrawn compared with 14% if combination therapy was maintained. The difference in the IPSS attributable to withdrawing tamsulosin was only about 1 symptom unit. It has also been previously demonstrated that when a drug is randomly withdrawn in a placebo-controlled trial design, the severity of LUTS does not return to baseline, suggesting a persistent residual nondrug effect in the placebo group. Therefore, one cannot assume that the residual response after withdrawing tamsulosin was entirely a dutasteride effect. Ideally, the study should have included both a randomized withdrawal of tamsulosin and dutasteride and not just tamsulosin.

In summary, men with clinical BPH are best treated initially with α-blocker monotherapy to relieve LUTS. The benefits of indiscriminately initiating the treatment of men with clinical BPH on combination therapy will add little to symptom improvement. Although combination therapy does decrease disease progression relative to monotherapy, the clinical relevance and cost-effectiveness of this outcome in an unselected group of men with clinical BPH are highly questionable.

In the subset of men with large prostates, both α-blockers and 5-ARIs significantly decrease LUTS, and this clinical benefit appears to be additive.14 In men with large prostates, 5-ARIs are superior to α-blockers at preventing AUR and BPH surgery; however, one has to treat a large cohort of men for 4 years with the addition of a 5-ARI to prevent a single episode of AUR or BPH surgery. Even in this highly selected cohort, the clinical significance of a 5-ARI for preventing disease progression is marginal.

Anticholinergic and α-Blocker

Historically, anticholinergic (ACH) agents were considered a contraindication in men suffering from BPH owing to a concern for precipitating AUR. A subset of men with LUTS and BPH has very troublesome symptoms that would fulfill the criteria for a diagnosis of OAB and BPH. The coexistence of these conditions raised the possibility that combination therapy with an α-blocker and anticholinergic agent might be efficacious in this challenging group of men often refractory to α-blocker therapy.

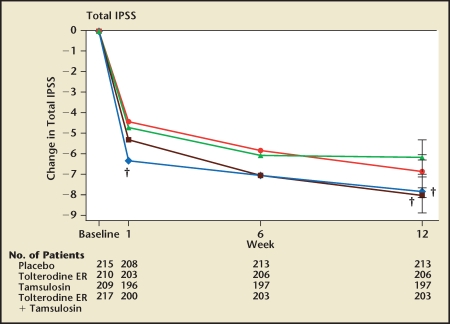

Kaplan and colleagues reported a 12-week, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled study comparing the safety and efficacy of the α-blocker tamsulosin, the anticholinergic tolterodine, the combination of these drugs, and placebo in 879 men fulfilling the criteria of both OAB and BPH.41 The interpretation of the study depends on the outcome measure under consideration. At 12 weeks, the IPSS score of the tamsulosin group was significantly lower than placebo (Figure 8). The IPSS scores of the combination and tamsulosin groups were virtually identical, indicating that combination therapy is no better than tamsulosin monotherapy at relieving LUTS in men with OAB and BPH. The percentages of men qualitatively exhibiting an improvement in LUTS in the placebo, tamsulosin monotherapy, tolterodine monotherapy, and combination groups were 62%, 65%, 71%, and 80%, respectively. Only the proportion of men qualitatively rating their symptoms as improved in the combination group was significantly greater than the placebo group. The study did not show that the qualitative assessment of symptoms was significantly greater in the combination therapy group relative to tamsulosin alone.

Figure 8.

Changes from baseline in International Prostate Symptom Score. Values are adjusted means (ie, leastsquares means). ER, extended release; IPSS, International Prostate Symptom Score. † P < .01 tversus placebo. Reproduced with permission from Kaplan SA et al.41

The natural history of AUR in men with BPH indicates the risk increases with duration of follow-up.14,15 The risk of AUR is greatest in men with large prostates. Interestingly, men in the tolterodine/tamsulosin study had very small prostates and therefore a relatively low risk of AUR. A study of 3 months’ duration is inadequate to examine the true effect of ACH on promoting AUR in men with BPH.

In summary, the tolterodine/tamsulosin study falls short of demonstrating, or even suggesting, the safety and efficacy of the combination of an α-blocker and ACH for the treatment of BPH.

Other Combination Therapies

There is no doubt that any combination of drugs with different mechanisms of action will likely show additive clinical effectiveness. When and if PDE5 inhibitors and other novel drugs are approved for the treatment of BPH, the next step will be to examine the benefit of combination therapy with an α-blocker or 5-ARI. The cost of combination must be considered owing to a long-term commitment to medical therapy. It is likely that only subsets of men will benefit from a specific combination and therefore the challenge will be to identify that subset instead of treating all men with expensive combination therapies.

Main Points.

Medical therapy for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) became an accepted standard of care in the 1990s following the reports of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies showing that finasteride, a 5-α reductase inhibitor (5-ARI), and terazosin, an α-blocker, significantly improved lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and increased peak urinary flow rates in men with BPH.

The evolution of α-blockers for the treatment of clinical BPH has involved the development of subtype-selective α-antagonists and novel formulations that ultimately allow for a single, daily-dose administration without the requirement for dose titration. Of all α-blockers, only silodosin exhibits any degree of α-adrenoceptor subtype selectivity that can be leveraged in the clinical setting.

Initial data support the clinical benefit of phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors for the treatment of LUTS secondary to BPH. Four large, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials have examined the effectiveness of sildenafil, tadalafil, and vardenafil in men with LUTS and BPH; all of the studies consistently demonstrated that this class of drugs improves LUTS in men with BPH.

Intraprostatic botulinum toxin type A (BoNT-A) is not yet approved by the US Food and Drug Adaministration. Long-term safety questions, including effect on serum prostate-specific antigen levels and risk of prostate cancer, have yet to be answered. Intraprostatic BoNT-A may ultimately become a useful treatment in patients with BPH/LUTS refractory to oral medications, especially those who are not candidates for surgery.

Trials evaluating the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist cetrorelix have reported conflicting findings. Additional randomized, placebo-controlled trials that are appropriately powered need to be conducted to verify clinical benefit and safety.

NX-1207 is a new drug under investigation for the treatment of symptomatic BPH. Four clinical trials yet to be published in the peer-reviewed literature have been interpreted to show improvement in LUTS exceeding that of all other medical therapies currently marketed for the treatment of BPH. These clinical benefits were maintained after angle injection for a year. Phase III studies are underway to define the true efficacy, safety, and mechanism of action of this novel approach to treating BPH.

Men with clinical BPH are best treated initially with α-blocker monotherapy to relieve LUTS. Although combination therapy does decrease disease progression relative to monotherapy, the clinical relevance and cost-effectiveness of this outcome in an unselected group of men with clinical BPH are highly questionable. In the subset of men with large prostates, both α-blockers and 5-ARIs significantly decrease LUTS and this clinical benefit appears to be additive. In men with large prostates, 5-ARIs are superior to α-blockers at preventing AUR and BPH surgery; however, one has to treat a large cohort of men for 4 years with the addition of a 5-ARI to prevent a single episode of AUR or BPH surgery. Even in this highly selected cohort, the clinical significance of a 5-ARI for preventing disease progression is marginal.

A study evaluating tolterodine/tamsulosin combination therapy falls short of demonstrating, or even suggesting, the safety and efficacy of the combination of an α-blocker and anticholinergic for the treatment of BPH.

References

- 1.Berry SJ, Coffey DS, Walsh PC, Ewing LL. The development of human benign prostatic hyperplasia with age. J Urol. 1984;132:474–479. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49698-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shapiro E, Becich MJ, Hartanto V, Lepor H. The relative proportion of stromal and epithelial hyperplasia is related to the development of symptomatic benign prostate hyperplasia. J Urol. 1992;147:1293–1297. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37546-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lepor H, Rigaud G. The efficacy of transurethral resection of the prostate in men with moderate symptoms of prostatism. J Urol. 1990;143:533–537. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)40012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Finasteride Study Group, authors. Finasteride (MK-906) in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Prostate. 1993;22:291–299. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990220403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lepor H, Auerbach S, Puras-Baez A, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled multicenter study of the efficacy and safety of terazosin in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 1992;148:1467–1474. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36941-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lepor H. Nonoperative management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 1989;141:1283–1289. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)41282-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirby R, Lepor H. Evaluation and nonsurgical management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, editors. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 9th ed. New York: Elsevier; 2007. pp. 2766–2782. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark RV, Hermann DJ, Cunningham GR, et al. Marked suppression of dihydrotestosterone in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia by dutasteride, a dual 5alpha-reductase inhibitor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2179–2184. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roehrborn CG, Boyle P, Nickel JC, et al. Efficacy and safety of a dual inhibitor of 5-alphareductase types 1 and 2 (dutasteride) in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 2002;60:434–441. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01905-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lepor H. The evolution of alpha-blockers for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Rev Urol. 2006;8(suppl 4):S3–S9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lepor H, Williford WO, Barry MJ, et al. The efficacy of terazosin, finasteride, or both in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:533–539. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608223350801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stoner E. Three-year safety and efficacy data on the use of finasteride in the treatment of of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 1994;43:284–294. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(94)90068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirby RS, Roehrborn C, Boyle P, et al. for the Prospective European Doxazosin and Combination Therapy Study Investigators, authors. Efficacy and tolerability of doxazosin and finasteride, alone or in combination, in treatment of symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia: the Prospective European Doxazosin and Combination Therapy (PREDICT) trial. Urology. 2003;61:119–126. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McConnell JD, Roehrborn CG, Bautista OM, et al. for the Medical Therapy of Prostatic Symptoms (MTOPS) Research Group, authors. The long-term effect of doxazosin, finasteride, and combination therapy on the clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2387–2398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roehrborn CG, Siami P, Barkin J, et al. for the CombAT Study Group. The effects of combination therapy with dutasteride and tamsulosin on clinical outcomes in men with symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia: 4-year results from the CombAT study. Eur Urol. 2010;57:123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwinn DA, Roehrborn CG. Alpha1-adrenoceptor subtypes and lower urinary tract symptoms. Int J Urol. 2008;15:193–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2007.01956.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lepor H, Hill LA. Silodosin for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: pharmacology and cardiovascular tolerability. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30:1303–1312. doi: 10.1592/phco.30.12.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marks LS, Gittelman MC, Hill LA, et al. Rapid efficacy of the highly selective alpha1A-adrenoceptor antagonist silodosin in men with signs and symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia: pooled results of 2 phase 3 studies. J Urol. 2009;181:2634–2640. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roehrborn CG, Lepor H, Kaplan SA. Retrograde ejaculation induced by silodosin is the result of relaxation of smooth musculature in the male uro-genital tracts and is associated with greater urodynamic and symptomatic improvements in men LUTS secondary to BPH. J Urol. 2009;181:694–695. [Abstract 1922] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lepor H, Williford WO, Barry MJ, et al. The impact of medical therapy on bother due to symptoms, quality of life and global outcome, and factors predicting response. Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Study Group. J Urol. 1998;160:1358–1367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwartz EJ, Lepor H. Radical retropubic prostatectomy reduces symptom scores and improves quality of life in men with moderate and severe lower urinary tract symptoms. J Urol. 1999;161:1185–1188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosen R, Altwein J, Boyle P, et al. Lower urinary tract symptoms and male sexual dysfunction: the multinational survey of the aging male (MSAM-7) Eur Urol. 2003;44:637–649. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2003.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laydner HK, Oliveira P, Oliveira CR, et al. Phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors for lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia: a systematic review. BJU Int. 2011;107:1104–1109. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takeda M, Tang R, Shapiro E, et al. Effects of nitric oxide on human and canine prostates. Urology. 1995;45:440–446. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(99)80013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dorsey P, Keel C, Klavens M, Hellstrom WJ. Phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors for the treatment of erectile dysfunction. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11:1109–1122. doi: 10.1517/14656561003698131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McVary KT, Monnig W, Camps JL, Jr, et al. Sildenafil citrate improves erectile function and urinary symptoms in men with erectile dysfunction and lower urinary tract symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia: a randomized, double-blind trial. J Urol. 2007;177:1071–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McVary KT, Roehrborn CG, Kaminetsky JC, et al. Tadalafil relieves lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2007;177:1401–1407. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stief CG, Porst H, Neuser D, et al. A randomised, placebo-controlled study to assess the efficacy of twice-daily vardenafil in the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Eur Urol. 2008;53:1236–1244. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.01.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roehrborn CG, McVary KT, Elion-Mboussa A, Viktrup L. Tadalafil administered once daily for lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia: a dose finding study. J Urol. 2008;180:1228–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.06.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schantz EJ, Johnson EA. Botulinum toxin: the story of its development for the treatment of human disease. Perspect Biol Med. 1997;40:317–327. doi: 10.1353/pbm.1997.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nitti VW. Botulinum toxin for the treatment of idiopathic and neurogenic overactive bladder: state of the art. Rev Urol. 2006;8:198–208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ilie CP, Chancellor MB, Chuang YC, Dan M. Intraprostatic botulinum toxin injection in patients with benign prostatic enlargement. J Med Life. 2009;2:338–342. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maria G, Brisinda G, Civello IM, et al. Relief by botulinum toxin of voiding dysfunction due to benign prostatic hyperplasia: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Urology. 2003;62:259–264. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00477-1. discussion 264–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brisinda G, Cadeddu F, Vanella S, et al. Relief by botulinum toxin of lower urinary tract symptoms owing to benign prostatic hyperplasia: early and long-term results. Urology. 2009;73:90–94. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.08.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gonzalez-Barcena D, Vadillo Buenfil, Garcia Procel E, et al. Inhibition of luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone and sex-steroid levels in men and women with a potent antagonist analog of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone, Cetrorelix (SB-75) Eur J Endocrinol. 1994;131:286–292. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1310286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Debruyne F, Tzvetkov M, Altarac S, Geavlete PA. Dose-ranging study of the luteinizing hormonereleasing hormone receptor antagonist cetrorelix pamoate in the treatment of patients with symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 2010;76:927–933. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.09.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.AEterna Zentaris (AEZS) announces results from two phase 3 studies with cetrorelix in benign prostatic hyperplasia, phase 3 trial misses primary endpoint [press release] Quebec City, Canada: AEterna Zentaris; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 38.AEterna Zentaris (AEZS) announces results from its European phase 3 study with cetrorelix in benign prostatic hyperplasia; study Z-036 did not reach primary endpoint [press release] Quebec City, Canada: AEterna Zentaris; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shore N. NX-1207: a novel investigational drug for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2010;19:305–310. doi: 10.1517/13543780903555196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barkin J, Guimarães M, Jacobi G, et al. Alphablocker therapy can be withdrawn in the majority of men following initial combination therapy with the dual 5alpha-reductase inhibitor dutasteride. Eur Urol. 2003;44:461–466. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(03)00367-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaplan SA, Roehrborn CG, Rovner ES, et al. Tolterodine and tamsulosin for treatment of men with lower urinary tract symptoms and overactive bladder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296:2319–2328. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.19.2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]