Urologic Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndromes (UCPPS), including chronic prostatitis (CP)/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS), and interstitial cystitis (IC)/painful bladder syndrome (PBS), remain one of the most frustrating urologic conditions to understand and manage. The paradigm shift in our understanding that these conditions represent more than an organ-centric medical disease, and our observations that patients presenting with these conditions have multiple different clinical phenotypes has led to a more rational patient-directed multidisciplinary, multimodal therapeutic strategy. These concepts were explored and discussed at an International Pain Day symposium, held on August 29, 2010, in Kingston, Ontario, Canada. This comprehensive review represents an update on urologic chronic pelvic pain based on the proceedings of that meeting.

UCPPS is one of the most frustrating and difficult conditions seen in urologic practice. The etiology is uncertain, the diagnosis is one of exclusion, and, based on significant subjective criteria, prediction of progression is not possible, prognosis is unpredictable, and treatment, particularly for chronic patients, is acknowledged as dismal.1 It is now recognized that successful management of UCPPS is only possible using a multidisciplinary and multimodal pain management approach for chronic noncancer pain.2 We should all consider adopting the credo used by the Toronto-based Wasser Pain Management Centre that, “All individuals suffering from pain deserve to have their pain and their associated conditions assessed and then appropriate treatment must be given.”

Urologists managing male and female patients presenting with UCPPS must understand that CP and IC/PBS are not the only pelvic pain syndromes that they will see. Other conditions that must be considered in the differential diagnosis include vulvar and urethral pain syndromes, pudendal nerve (and other regional nerve) entrapment, pelvic floor pain, endometriosis, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), as well as pain syndromes associated with external genitalia including clitoral, penile, and testicular (scrotal) pain. Furthermore, we now know that these conditions frequently coexist in the same patient.

Using the ADDOP Approach to the Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Pelvic Pain: The Five Pillars of Pain Management

The Wasser clinic approach employing five pillars of pain management is one that can be considered for the diagnosis and management of UCPPS3:

Pillar One: Assess the individual including risk assessment, symptom, and sign assessment. The Universal Precautions4 to stratify individuals into low-, medium-, and high-risk categories is suggested.

Pillar Two: Define and treat the underlying diagnosis such as the diabetes in painful diabetic neuropathy.

Pillar Three: Diagnose the kind of pain and treat it: for example, neuropathic pain versus nociceptive pain.

Pillar Four: Other symptoms, conditions, and complications such as mood and sleep.

Pillar Five: Personal responsibility and self management. If you, as the physician, are working harder than your patient, there is something wrong.

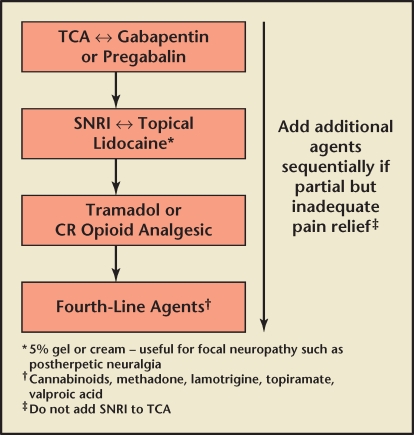

The optimal pharmacologic approach to the management of neuropathic pain appears to be a stepwise management algorithm.5 There are a number of published guidelines, but for the purposes of Canadian urologists, the Canadian guideline is the most appropriate. This describes four levels of neuropathic therapy developed for peripheral neuropathic pain, but in the absence of specific controlled studies may be used as guideposts. There are few well-controlled pharmacotherapy studies in this area. Management of chronic pain refractory to conservative treatment, including standard analgesic and condition-specific therapies (see later in the article), should normally start with a tricyclic and/or gabapentinoid (gabapentin or pregabalin; then go to a drug such as duloxetine or venlafaxine or a topical medication such as lidocaine, gabapentin, or capsaicin; an opioid such as tramadol, oxycodone, or morphine; and then a variety of agents (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Stepwise pharmacologic management of chronic pain refractory to conservative treatment. CR, continuous release; SNRI, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.

[Allan Gordon, MD]

CP as a Mechanistic Model of UCPPS

The etiology of CP/CPPS is unknown. Our current working hypothesis is that there is likely a trigger event such as infection, trauma, or even stress that, in susceptible individuals, results in chronic pelvic pain. The pain is either modulated or perpetuated by factors including psychologic, inflammatory/immune, neurologic, and endocrine aspects. The clinical manifestation may also be affected by the patient’s social situation.

The epidemiology of CP/CPPS suggests that, in some men, it may progress along with other systemic diseases. In the National Institutes of Health (NIH)-sponsored Chronic Prostatitis Cohort study, men with CP/CPPS were six times more likely to report a history of cardiovascular disease than age-matched asymptomatic controls. They were five times more likely to report a history of neurologic disease, and twice as likely to report sinusitis and anxiety/depression.6 A recent review of the overlap between CP/CPPS, IC/PBS, and systemic pain conditions such as IBS, fibromyalgia, and chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) found that 21% of men with CPPS report a history of musculoskeletal, rheumatologic, or connective tissue disorder. Men with CP/CPPS report CFS twice as often as asymptomatic controls, and 19% to 79% of men with CPPS report IBS or IBS symptoms.7 The conclusion from these findings is that, in some men, CP/CPPS may be part of systemic pain syndrome.

Although the symptoms of CP/CPPS mimic those of a true prostatic infection, there has yet to be a clear association between bacteria and the presence of CP/CPPS. Localizing cultures in men with CP/CPPS and asymptomatic controls showed almost identical numbers of bacteria isolated from urine, prostatic fluid, and post-prostate massage urine.8 A history of sexually transmitted disease is almost twice as common in men with CP/CPPS compared with men without the condition, indicating a possible role for urethritis as a causative factor.6 A recent report indicates that blood samples examined for Helicobacter pylori antibodies were positive in 76% of men with CP/CPPS compared with 62% in controls (P < .05). Although this is significantly greater, a large number of patients without symptoms were seropositive.9

The role of inflammation is also unclear in CPPS. The fact that men with category IIIB have no inflammation but pain makes this link questionable. Also, in men with CPPS who have inflammation, the amount of inflammation does not correlate with symptoms.10 There is evidence, however, that autoimmunity may be a factor in some men. CD4 T cells purified from 31 men with CPPS were compared with 27 controls with exposure to antigens consisting of parts of the prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP) and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) molecules. Activation and release of INFα are markers of recognition of the antigens. A region of the PAP molecule, 173–192, was recognized in 15 of 23 patients and in only 5 of 22 controls (P < .01). Recognition of parts of the PSA molecule was also greater in CPPS (12 of 24 CPPS vs 4 of 22 controls; P < .05).11 These data indicate the likelihood of autoimmunity in some men with CPPS. Although the utility of cytokines as biomarkers has been mixed so far in CPPS, two new candidate molecules have emerged as likely being important in this syndrome. Macrophage inflammatory protein 1-α(MIP-1α) and monocyte chemo-attractant protein-1 (MCP-1) have both been found in significantly greater amounts in the expressed prostatic secretions of men with CP/CPPS compared with asymptomatic controls and men with benign prostatic hyperplasia (P = .0002).12 In addition, MIP-1α levels correlated with pain levels in these men (P = .0007).

Given that the cardinal symptom in CP/CPPS is pain, it also makes sense that the nervous system plays a role. In addition to MIP-1α, another marker that correlates with pain is nerve growth factor (NGF).13 NGF is a neuropeptide that plays a role in nociception and regulates the sensitivity of adult neurons to capsaicin, which excites C-fibers in addition to mediating long-term depolarization via Nmethyl-D-aspartate receptors. Men with CPPS have been found to have alterations in both afferent and efferent autonomic nervous system function.14 Also, affecting both immune and nervous system function are endocrine factors. On awakening, serum cortisol levels rise; there is a significantly greater cortisol rise in men with CPPS compared with controls.15 Men with CPPS also have a lower baseline adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) level and blunted ACTH rise in response to stress than men without symptoms.16 In the same study, men with CPPS were found to have more anxiety and perceived stress.

There is also a psychosocial context to the presentation of pain. The same biologic insult in given individuals can result in different pain experiences. This includes how the individual interacts with those around him,17 including spousal support. Thus, there may be common underlying mechanisms that we can target to treat CPPS as a whole, but we must also consider that, on some level, the pathogenesis and thus treatment of each patient with CPPS will be unique to that patient.18

[Michel Pontari, MD]

Evaluation and Treatment of Men With CP/CPPS

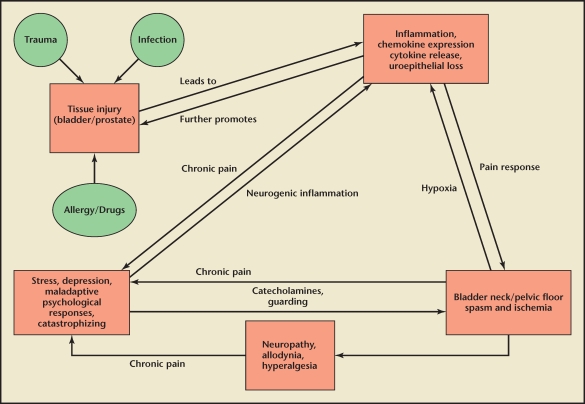

Category III prostatitis, also known as CPPS, is a common condition with significant impact on quality of life.19 There is little consensus on appropriate therapy and indeed both patient and urologist frustration is high in dealing with the disorder. Part of the problem is the heterogeneous nature of CPPS, which is, by definition, a syndrome rather than a disease that can be targeted by one specific therapy. Large, multicenter trials of promising treatments (eg, antibiotics, α-blockers,20 neuroleptic agents) have often shown minimal or no benefit when compared with placebo; however, the heterogeneous nature of patients in these studies may have prevented a positive result for patients with the appropriate mechanism or etiology of symptoms. This would be analogous to testing an effective migraine drug in patients only defined as having a headache, which could include patients with a brain tumor, infected tooth, or neck spasm. Currently, we do not have validated biomarkers that would allow us to classify patients in a way that could guide therapy. A scheme of our current best understanding of the pathophysiology of CPPS is seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Proposed pathophysiology of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome.

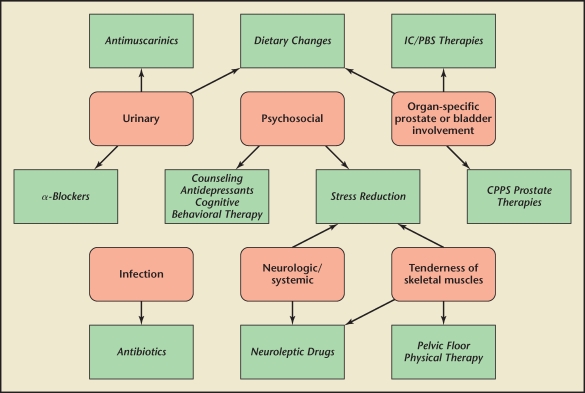

In response to this situation, a 6-point clinical phenotyping system has been proposed to classify patients with chronic pelvic pain (CPPS and IC) and to direct appropriate therapy.21 The clinical domains are urinary symptoms, psychosocial dysfunction, organ-specific findings, infection, neurologic/systemic, and tenderness of muscles. This produces the mnemonic UPOINT. Each domain is clinically defined, is linked to specific mechanisms of symptom production or propagation, and is associated with specific therapy. Symptom severity is then measured using the NIH Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (CPSI). The number of positive UPOINT domains correlates with symptom severity and symptom duration.22 These findings have been confirmed by researchers in Sweden,23 Italy, and Germany.24

The ultimate goal was to use UPOINT to improve patient outcomes. In a recent prospective study published in the journal Urology,25 100 CPPS patients were treated with multimodal therapy, offering specific therapy for each positive domain (eg, urinary: α-blocker or antimuscarinic; psychosocial: stress reduction/psychologic support; organ-specific: quercetin; infection: antibiotic; neurologic/systemic: amitriptyline or pregabalin; tenderness: pelvic floor physical therapy). With a minimum follow-up of 6 months, and average follow-up of 50 weeks, 84 patients (84%) reached the primary endpoint of a 6-point or greater improvement in total CPSI. The chance of reaching the primary endpoint was not significantly different regardless of number of positive domains. Fifty-one patients had a 50% or greater improvement in total CPSI, whereas 84 patients had at least a 25% or greater improvement. All CPSI subscores were significantly improved from baseline. The improvement seen in all groups was not simply due to regression to the mean of more symptomatic patients because number of UPOINT domains did not correlate with drop in CPSI. In addition, drop in CPSI did not correlate with symptom duration or number of therapies. Although this was not a placebo-controlled study, the incidence and magnitude of improvement was significantly higher than reported in prior large or multicenter studies of comparable duration.

An online resource has been created that will allow urologists to enter patient data and be given the UPOINT phenotype as well as suggested therapies. This can be found at http://www.upointmd.com. Such a simple algorithmic approach can simplify the care and improve the outcomes for men who suffer with CPPS.

[Daniel Shoskes, MD]

Multidisciplinary Approach to Urologic Pain in Women

IC was first described more than 90 years ago as a distinct ulcer seen in the bladder on cystoscopy. This classic IC is truly a bladder disease, confirmed as severe inflammation on biopsy and symptom improvement with eradication of the ulcers. The presentation may be variable; however, the key symptoms are urinary frequency, urgency, and pelvic pain. The definition of IC has been broadened to include patients without ulcers, but with symptoms of urinary urgency, frequency, and pelvic pain who had identifiable causes ruled out such as urinary tract infections, bladder cancer, and endometriosis. In patients without ulcers, but symptoms of IC, the bladder epithelium has been the focus of the pathogenesis of IC and therapy has been directed at treating the leaky epithelium. The assumption is the bladder is a storage organ that stores urine that is toxic.

For the bladder to function as a storage organ, it must protect itself from the irritants and toxins in the urine. If the protective layer of the bladder is compromised, the urine will act as an irritant, penetrate into the detrusor wall, lead to proliferation of mast cells and nerve upregulation, and, ultimately, bladder irritation with urinary urgency, frequency, and pain. Despite many studies evaluating compounds directed at treating the epithelium for IC, few have proven to be effective when studied in a rigorous fashion using a placebo-controlled trial design.26

Clinicians who have been managing IC realize that there is a clear distinction between ulcerative and nonulcerative IC. The former is an inflammatory bladder disease and the latter is a pain syndrome that not only includes urinary urgency, frequency, and pelvic pain, but also includes fibromyalgia, IBS, migraine headaches, multiple allergies, CFS, vulvodynia, dyspareunia, female sexual dysfunction, and pelvic floor dysfunction. Thus, to effectively treat patients with chronic pelvic pain, it is important to be an astute clinician and phenotype patients (UPOINT) to direct therapy toward the underlying clinical entities.27

One of the most common, reversible causes of pelvic pain, dyspareunia, urgency, and frequency has been pelvic floor dysfunction. Myofascial pain and hypertonic pelvic floor dysfunction are present in more than 50% of patients with IC and/or CPPS.28 The cause of pelvic floor dysfunction is unknown, but it is similar to a tension headache of the pelvis. Having appropriate control of the pelvic floor is important in normal bladder and bowel function. If a woman cannot relax her pelvic floor when voiding, this leads to voiding dysfunction. Stress often worsens the symptoms of IC, likely by worsening the pelvic floor spasm and creating more pelvic symptoms. A noxious stimulus may trigger the release of nerve growth factor and substance P in the periphery, causing the mast cells in the bladder to release proinflammatory substances causing neurogenic inflammation of the bladder wall. This can result in painful bladder symptoms (IC) and vulvar or vaginal pain. When evaluating a patient with urinary urgency, frequency, and pelvic pain, it is imperative to not only focus on the bladder as a cause of the syndrome, but also the pelvic floor. If palpation of the levator muscles reproduces the patient’s pain or bladder pressure, then it is reasonable to consider pelvic floor therapy as a first-line treatment before any invasive testing or medications are used.29 If pelvic floor involvement is identified, treatment by a therapist knowledgeable in intravaginal myofascial release may markedly improve symptoms and often is the only treatment needed. If no levator spasm or tenderness is identified on initial evaluation, or if after completing pelvic floor therapy the patient continues to have urinary symptoms, then it is reasonable to evaluate and treat further with standard therapies for IC.

Over the past 20 years, bladder-directed therapy has been ineffective in treating the syndrome of IC and it is now time to think outside the box when evaluating women with CPPS. The key is to evaluate the whole patient, identify pain trigger points, prioritize problems, consider the mind-body connection, and provide encouragement and support. Behavioral interventions such as dietary changes, stress reduction, guided imagery, cognitive behavioral therapy, yoga, and relaxation techniques may help improve symptoms. Along with pelvic floor physical therapy, consider intravaginal valium, vaginal dilators, and injection of trigger points with Botox® (Allergan, Irvine, CA) or Marcaine® (Sanofi Winthrop Inc., New York, NY) and Kenalog® (Bristol Myers Squibb, Princeton, NJ). Neuromodulation using tibial nerve stimulation, sacral nerve stimulation, or transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation devices may improve the symptoms of chronic pelvic pain and urinary frequency. A model of care that provides comprehensive multidisciplinary (urologists, urogynecologists, women’s health nurse practitioners, pelvic floor physical therapists, integrative medicine, and psychologic services) evaluation and treatment to this very challenging patient population will lead to improvement of our management of women with chronic pelvic pain.

[Kenneth M. Peters, MD]

Understanding and Managing Pain Catastrophizing in UCPPS Treatment

Pain-related catastrophizing is a set of persistent negative pain-related thoughts used when a patient is undergoing or anticipating pain.30 Catastrophizing is a robust pain predictor assessed using the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS),31 a 13-item measure with three factors: rumination (eg, I worry all the time about whether the pain will end), magnification (eg, I keep thinking of other painful events), and helplessness (eg, I feel like I can’t go on). UCPPS research suggests that catastrophizing may be a prominent psychosocial factor in CP/CPSS and IC/PBS for both pain and diminished quality of life (QoL).

CP/CPPS Pain and Catastrophizing

The first study examining catastrophizing in CP/CPPS was conducted by the NIH-Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network (CPCRN) Study Group,32 which found that catastrophizing was correlated with greater disability, higher urinary scores, depressive symptoms, and pain. Furthermore, catastrophizing was a significant pain predictor when demographic and psychosocial variables were controlled. Another recent study showed that diminished mental status QoL was predicted by greater helplessness catastrophizing and lower social support from friends and family, beyond the demographic, medical status, and other psychosocial variables in the analyses.33 Further, Tripp and colleagues34 showed that an adolescent male sample (aged 16 to 19 years) reported a prevalence of at least mild prostatitis-like symptoms at 8.3%, with 3% reporting a pain domain score of > 7. Pain, urinary symptoms, depressive symptoms, and catastrophizing were all correlated with poorer QoL and the catastrophizing magnification domain was the lone predictor of poorer QoL after controlling for pain and urinary scores. These findings have increased the desire to model UCPPS treatment from a framework that manages individual patients using a multimodal therapy approach to UCPPS. UPOINT is a 6-point clinical classification system that includes a psychosocial domain (ie, catastrophizing).22

IC/PBS and Catastrophizing

Earlier IC/PBS studies examining catastrophizing and patient outcomes showed that catastrophizing was associated with greater depressive symptoms, poorer mental health, poorer social functioning, and greater pain.35 A recent cohort of female patients with IC/PBS from three IC/PBS clinics reported on patient QoL, IC/PBS symptoms, sexual functioning, pain, and psychosocial factors.36 The data showed that greater helplessness catastrophizing was the primary predictor of diminished mental QoL over the significant effects of factors like older age. The IC/PBS and catastrophizing findings have directed current efforts in the area of clinical assessment and management of psychosocial factors for improved patient adjustment. Using the clinically practical UPOINT phenotyping classification system for patients diagnosed with IC/PBS,27 the psychosocial domain of UPOINT (ie, catastrophizing) identified patients with IC/PBS who also reported greater pain, urinary urgency, and frequency. Accumulating evidence suggests that it is likely that psychosocial factors and catastrophizing in particular significantly impact patient outcomes.37

Treatment for Catastrophizing

Interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, targeting catastrophizing and helplessness, in particular, may be invaluable to UCPPS management programs. Recent articles have outlined how such programs may be developed from an empirically supported base of intervention38 with a particular emphasis on the amelioration of catastrophizing.

Catastrophizing is a clear and pressing concern for UCPPS treatment. Support from empirical studies across UCPPS conditions suggests that helplessness catastrophizing may be a particular focus of intervention and ongoing clinical research.

[Dean Tripp, PhD]

A Holistic Approach to the Treatment of UCPPS

A holistic approach aims to empower a patient and to treat the whole person, not just symptoms. Its purpose is to help patients assume responsibility. Responsibility entails the ability of a patient to respond to her situation. This is a fundamental right, and it requires a patient to be actively involved in her healing process. A central tenet of mind-body medicine is the recognition that the mind plays a key role in health and that any presumed separation of mind and body is false.39 Stress is not a known cause of UCPPS, but having chronic pain causes enormous stress. With mind-body techniques like meditation, the patient learns not only to relax and to breathe, but also to change his/her way of thinking.

The lifestyle modification discussion includes the topics of eating, sleeping, and working habits. It emphasizes that supplements and herbs are not suitable substitutes for a healthy diet. Table 1 lists some supplements that patients may consider. Some patients with CPPS are very sensitive to foods. Avoiding potentially aggravating foods such as colas, caffeine, and acidic and spicy foods for 4 to 6 weeks, and then slowly reintroducing one at a time is a sound strategy for discovering which foods are aggravating a patient’s symptoms.

Table 1.

Supplements and Herbal Therapies Suggested for UCPPS

Reduce swelling and inflammation

|

Ameliorate painful urination

|

Reduce stress and muscle spasms

|

Reduce constipation

|

Prevent urinary tract infection

|

Improve antibiotic effectiveness

|

Studies evaluating hypnosis in chronic pain conditions40 indicate that for both chronic and acute pain conditions, hypnotic analgesia consistently results in greater decreases in a variety of pain outcomes compared with standard treatment alone. Hypnosis frequently outperforms nonhypnotic interventions (eg, education, supportive therapy), resulting in greater reductions of pain-related outcomes. It also performs similarly to treatments that contain hypnotic elements (eg, progressive muscle relaxation), but is not surpassed in efficacy by these alternative treatments. Factors that influence the efficacy of hypnotic analgesia interventions include, but are not limited to, the patient’s level of suggestibility, treatment outcome expectancy, and provider expertise.

Biofeedback educates patients to improve their health by using signals from their own bodies. Specialists in many different fields use biofeedback to help patients cope with pain. The most common forms of biofeedback are electromyography (EMG) and the electrodermal therapy (EDR). These sensors allow a person to monitor their own muscle relaxation, heart rate, and breathing patterns. It enables the subject to concentrate on changing the patterns through either the visual or auditory information provided by the equipment.

Thermal therapy can involve superficial heat (heating pad or hot pack), deep heat (ultrasound), or cooling (cold pack). Heat is often helpful for joint stiffness, although cold therapy is likely to aggravate it. The results are relatively short lived.

Massage and myofascial release relax muscles and improve circulation and range of motion. Often massage is offered in places where calm music and Bach flower essences are used. These help to release endorphins and create a general sense of well-being, meant not only for patients in pain, but also for people eager to care for their health by preventing disease. Thiele massage appears to be very helpful in improving irritative bladder symptoms in patients with IC and high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction, in addition to decreasing pelvic-floor muscle tone.28,29 Myofascial release therapy combined with progressive relaxation training is an effective therapeutic approach for the management of CP/CPPS, providing pain and urinary symptom relief.41

Yoga, tai chi, and qi gong involve gentle exercises that reestablish harmony and balance in the energy level of the body. Breathing exercises are key factors in these techniques. Although deep breathing exercises were ineffective in reducing pain levels, the majority of those who received deep breathing education felt it was useful, increasing their feelings of rapport and intention to follow their doctor’s directives.42 Acupuncture (electro-acupuncture) therapy has been shown to have independent therapeutic effects, particularly for pain relief in CP/CPPS and is superior to sham.43

In clinical practice, the placebo response is often regarded as a nuisance. The latest scientific evidence has demonstrated that placebo and nocebo effect stem from highly active processes in the brain that are mediated by psychologic mechanisms such as expectation and conditioning. These processes have been described in some detail for many diseases and treatments, and we now know that they can represent both strength and vulnerability in the course of a disease as well as in the response to a therapy.44 The astute physician will use the placebo effect to the benefit of the patient.

Table 2 lists some of the alternative holistic therapies available for patients to consider.

Table 2.

Holistic Modalities of Therapy for UCPPS

Mind-body

|

Manipulative body-based methods

|

Biological

|

Energy-based

|

Behavioral

|

[Ragi Doggweiler, MD]

How to Integrate Pain Interventions Into the Care of the Pain Patient

It is well accepted that a person’s experience of pain will be dependent on not only the biologic processes underlying the pain condition, but also on the person’s psychologic, behavioral, sexual, and social status (the biopsychosocial model).32–39 When it comes to urogenital pelvic pain syndromes, it is often the case that there are no obvious well-described local pathologies. There is very minimal evidence for effective biologic treatments (both procedures and drugs); however, there are many suggested interventions and it is generally accepted (by evidenced-based medicine, expert opinion, and common sense) that such treatments may have a role for certain patients.45

It is standard practice that all patients must have a full history and examination undertaken by a medical practitioner experienced in the field and where that is likely to lead to an intervention that person should be the interventionist.46 When indicated appropriate, investigations should be arranged. Any red flags must result in the correct onward referral and further investigation of these symptoms and their management. The key to integrating biologic interventions into patient care is to also look for those negative prognostic factors in the areas of: psychosocial yellow flags,47 occupational blue flags,48 and socioeconomic black flags.49 Negative factors in these areas are likely to impede a response to a physical intervention and may even result in a pain and/or psychologic crisis for the patient. Common sense would indicate that negative flags must be acknowledged early and if they appear significant they will need to be managed prior to any biologic physical intervention. The pain team is well established as being a significant force in reversing many of these issues and we should consider an early involvement of experienced pain medicine psychologists, nurses, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists.50 Not only do these team members provide therapy interventions, they also play an important role as advocates for patients, ensuring informed consent.

The common-sense approach to biologic interventions, where there is some evidence of efficacy but where it is limited, is to balance the risk against potential benefit. The patient must have appropriate expectations of a procedure or intervention with appropriate informed consent. Appropriate outcome measures must also be considered and these should include measures from several domains that will include a range of pain scores (eg, worst pain, average pain, frequency), emotional measures, behavioral scores, and, where appropriate, more specific questions around sexual activity and end-organ functional disorders (eg, bowel and urinary dysfunction). This translates into clinical practice that the patient needs to be treated as a whole and as an individual through an integrated care team approach. Subsequent intervention should be decided in the context of the biopsychosocial model. There is no doubt about the importance of evaluating and treating UCPPS patients as individuals using a team approach with comprehensive assessments, expectations, and explanations to optimize outcome.

[Andrew Paul Baranowski, BSc Hons, MBBS, FRCA, MD, FFPMRCA]

Optimizing Clinical Outcome

Clinical outcome for patients suffering from UCPPS and physicians managing it will depend on multiple factors that can best be described by the biopsychosocial rather than a pure biomedical model of disease. These factors include antecedent premorbid conditions, associated medical conditions, various etiologic mechanisms, and multiple pathogenic pathways leading to very heterogenous clinical phenotypic presentations. A comprehensive assessment of all these factors, including diagnosis of all possible pain generators (Table 3), allowing a phenotypic classification (UPOINT is recommended; Figure 3) is therefore required prior to intervention (Table 4 and Figure 3). Patient and physician expectations must be realistic and patient-oriented goals of therapy must be mutually agreed upon. These should include a clinical meaningful amelioration of symptoms, improvement in QoL and activities, and reduction in the level of disability. This will only be accomplished by proper diagnosis and phenotyping (sources of pain, associated conditions, impacting factors) and appropriate therapy (treat all pain sources, all associated conditions, and all impacting factors). A multidisciplinary team approach with comprehensive assessment and individually directed therapy will ultimately optimize outcome.

Table 3.

Pain Generators That May Be Operative in Chronic Pelvic Pain

|

CPPS, chronic pelvic pain syndrome; CP, chronic prostatitis; IC, interstitial cystitis; PBS, painful bladder syndrome.

Figure 3.

UPOINT domains and associated therapies. CPPS, chronic pelvic pain syndrome; IC, interstitial cystitis; PBS, painful bladder syndrome.

Table 4.

The Five Steps of UCPPS Management

|

|

|

|

|

Before treatment is implemented, biopsychosocial associations (pain generators, associated conditions, and impacting factors) must be determined.

Main Points.

Urologic Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndromes (UCPPS) are one of the most difficult conditions to manage in urologic practice. It is now recognized that successful management of UCPPS is only possible using a multidisciplinary and multimodal pain management approach for chronic noncancer pain.

To understand the pathophysiology of chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS), a 6-point phenotyping system (UPOINT) has been proposed to classify patients and direct therapy: urinary symptoms, psychosocial dysfunction, organ-specific findings, infection, neurologic/systemic, and tenderness of muscles. The goal is to use UPOINT to simplify care and improve patient outcomes. An online resource is available for urologists at http://www.upointmd.com.

Bladder-directed therapy has been ineffective in treating the syndrome of interstitial cystitis and physicians should think outside the box when evaluating women with CPPS. The key is to evaluate the whole patient, identify pain trigger points, and prioritize problems. Behavioral interventions such as dietary changes, stress reduction, guided imagery, cognitive behavioral therapy, yoga, and relaxation techniques may help improve symptoms.

Interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy, targeting catastrophizing and helplessness, in particular, may be invaluable to UCPPS management programs. Catastrophizing is a clear and pressing concern for UCPPS treatment and support from empirical studies across UCPPS conditions suggests that helplessness catastrophizing may be a particular focus of intervention and ongoing clinical research.

The holistic approach for treating UCPPS aims to treat the whole person, not just the symptoms. Lifestyle modifications include a discussion of eating, sleeping, and work habits, and emphasize that herbs/supplements are not substitutes for a healthy diet. Holistic therapies for patients to consider include hypnotic analgesia, biofeedback, thermal therapy, massage, yoga, and tai chi.

Clinical outcome for patients suffering from UCPPS will depend on various factors including antecedent premorbid conditions and associated medical conditions. A comprehensive assessment of these factors, including diagnosis of all possible pain generators, is required prior to intervention. Patient and physician expectations must be realistic and patient-oriented goals of therapy must be mutually agreed upon.

References

- 1.Nickel JC. Words of wisdom: clinical phenotyping in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome and interstitial cystitis: a management strategy for urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes. Eur Urol. 2009;56:881. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nickel JC, Shoskes D. Phenotypic approach to the management of the chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. BJU Int. 2010;106:1252–1263. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordon A. Best practice guidelines for treatment of central pain after stroke in central neuropathic pain. In: Henry JL, Panju A, Yashpal K, editors. Central Neuropathic Pain: Focus on Poststroke Pain. Seattle, WA: IASP Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gourlay DL, Heit HA, Almahrezi A. Universal precautions in pain medicine: a rational approach to the treatment of chronic pain. Pain Med. 2005;6:107–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.05031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moulin DE, Clark AJ, Gilron I, et al. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain-Consensus statement and guidelines from the Canadian Pain Society. Pain Res Manag. 2007;12:13–21. doi: 10.1155/2007/730785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pontari MA, McNaughton-Collins M, O’Leary MP, et al. A case-control study of risk factors in men with chronic pelvic pain syndrome. BJU Int. 2005;96:559–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodriguez MA, Afari N, Buchwald DS for the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Working Group on Urological Chronic Pelvic Pain., authors Evidence for overlap between urological and nonurological unexplained clinical conditions. J Urol. 2009;182:2123–2131. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nickel JC, Alexander RB, Schaeffer AJ, et al. Leukocytes and bacteria in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome compared to asymptomatic controls. J Urol. 2003;170:818–822. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000082252.49374.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karatas OF, Turkay C, Bayrak O, et al. Helicobacter pylori seroprevalence in patients with chronic prostatitis: a pilot study. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2010;44:91–94. doi: 10.3109/00365590903535981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaeffer AJ, Knauss JS, Landis JR, et al. Leukocyte and bacterial counts do not correlate with severity of symptoms in men with chronic prostatitis: the National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Cohort Study. J Urol. 2002;168:1048–1053. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64572-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kouiavskaia DV, Southwood S, Berard CA, et al. T-cell recognition of prostatic peptides in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol. 2009;182:2483–2489. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.07.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desireddi NV, Campbell PL, Stern JA, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha as possible biomarkers for the chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol. 2008;179:1857–1861. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller LJ, Fischer KA, Goralnick SJ, et al. Nerve growth factor and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urology. 2002;59:603–608. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01597-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yilmaz U, Liu YW, Berger RE, Yang CC. Autonomic nervous system changes in men with chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol. 2007;177:2170–2174. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson RU, Orenberg EK, Chan CA, et al. Psychometric profiles and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol. 2008;179:956–960. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.10.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson RU, Orenberg EK, Morey A, et al. Stress induced hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis responses and disturbances in psychological profiles in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol. 2009;182:2319–2324. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tripp DA, Nickel JC. Quality of life in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) In: Preedy VR, Watson RS, editors. Handbook of Disease Burdens and Quality of Life Measures. London, UK: Springer; 2010. pp. 2211–2224. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pontari M. Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain: the disease. J Urol. 2009;182:19–20. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snow DC, Shoskes DA. Pharmacotherapy of prostatitis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11:2319–2330. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2010.495946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alexander RB, Propert KJ, Schaeffer AJ, et al. Ciprofloxacin or tamsulosin in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a randomized, double-blind trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:581–589. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-8-200410190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shoskes DA, Nickel JC, Rackley RR, Pontari M. Clinical phenotyping in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome and interstitial cystitis: a management strategy for urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2009;12:177–183. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2008.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shoskes DA, Nickel JC, Dolinga R, Prots D. Clinical phenotyping of patients with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome and correlation with symptom severity. Urology. 2009;73:538–542. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.09.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hedelin HH. Evaluation of a modification of the UPOINT clinical phenotype system for the chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2009;43:373–376. doi: 10.3109/00365590903164514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wagenlehner F, Magri V, Perletti G, et al. Clinical phenotyping of patient’s with chronic prostatitischronic pelvic pain syndrome in two specialized European institutions. J Urol. 2010;183(suppl):312. Abstract 799. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shoskes DA, Nickel JC, Kattan MW. Phenotypically directed multimodal therapy for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a prospective study using UPOINT. Urology. 2010;75:1249–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nickel JC. Interstitial cystitis: a chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Med Clin North Am. 2004;88:467–481. doi: 10.1016/S0025-7125(03)00151-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nickel JC, Shoskes DA, Irvine-Bird K. Clinical phenotyping of women with interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome: a key to classification and potentially improved management. J Urol. 2009;182:155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.02.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.FitzGerald MP, Anderson RU, Potts J, et al. Randomized multicenter feasibility trial of myofascial physical therapy for treatment of urologic chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol. 2009;182:570–580. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oyama IA, Rejba A, Lukban JC, et al. Modified Thiele massage as therapeutic intervention for female patients with interstitial cystitis and high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction. Urology. 2004;64:862–865. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sullivan MJL, Thorn B, Haythornthwaite J, et al. Theoretical perspectives on the relation between catastrophizing and pain. Clin J Pain. 2001;17:52–64. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200103000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7:524–532. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tripp DA, Nickel C, Wang Y, et al. Catastrophizing and pain-contingent rest as predictors of patient adjustment in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Pain. 2006;7:697–708. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nickel JC, Tripp DA, Chuai S, et al. Psychosocial variables affect the quality of life of men diagnosed with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) BJU Int. 2008;101:59–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tripp DA, Nickel JC, Ross S, et al. Prevalence, symptom impact and predictors of prostatitis-like symptoms in North American males aged 16–19 years. BJU Int. 2009;103:1080–1084. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rothrock NE, Lutgendorf SK, Kreder K. Coping strategies in patients with interstitial cystitis: relationships with quality of life and depression. J Urol. 2003;169:233–236. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64075-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tripp DA, Nickel JC, Fitzgerald MP, et al. Sexual functioning, catastrophizing, depression, and pain as predictors of quality of life in women suffering from interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. Urology. 2009;73:987–992. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nickel JC, Tripp DA, Pontari M, et al. Psychosocial phenotyping of women with IC/PBS: a case control study. J Urol. 2010;183:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nickel JC, Mullins C, Tripp DA. Development of an evidence-based cognitive behavioral treatment program for men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. World J Urol. 2008;26:167–172. doi: 10.1007/s00345-008-0235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Campbell CM, Edwards RR. Mind-body interactions in pain: the neurophysiology of anxious and catastrophic pain-related thoughts. Transl Res. 2009;153:97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stoelb BL, Molton IR, Jensen MP, Patterson DR. The efficacy of hypnotic analgesia in adults: a review of the literature. Contemp Hypn. 2009;26:24–39. doi: 10.1002/ch.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson RU, Wise D, Sawyer T, Chan C. Integration of myofascial trigger point release and paradoxical relaxation training treatment of chronic pelvic pain in men. J Urol. 2005;174:155–160. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000161609.31185.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Downey LV, Zun LS. The effects of deep breathing training on pain management in the emergency department. South Med J. 2009;102:688–692. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181a93fc5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee SH, Lee BC. Electroacupuncture relieves pain in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: three-arm randomized trial. Urology. 2009;73:1036–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Enck P, Benedetti F, Schedlowski M. New insights into the placebo and nocebo responses. Neuron. 2008;59:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fall M, Baranowski AP, Elneil S, et al. EAU guidelines on chronic pelvic pain. Eur Urol. 2010;57:35–48. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baranowski AP, Fall M, Abrams P. Urogenital Pain in Clinical Practice. New York: Taylor and Francis; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kendall NA. Psychosocial approaches to the prevention of chronic pain: the low back paradigm. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 1999;13:545–554. doi: 10.1053/berh.1999.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shaw WS, van der Windt DA, Main CJ, et al. Early patient screening and intervention to address individual-level occupational factors (“blue flags”) in back disability. J Occup Rehabil. 2009;19:64–80. doi: 10.1007/s10926-008-9159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haefeli M, Elfering A, Aebi M, et al. What comprises a good outcome in spinal surgery? A preliminary survey among spine surgeons of the SSE and European spine patients. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:104–116. doi: 10.1007/s00586-007-0541-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee J, Nandi P. Improving the management of neuropathic pain. Practitioner. 2010;254(1731):27–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]