Abstract

Therapy of heart failure is more difficult when renal function is impaired. Here, we outline the effects on kidney function of the autacoid, adenosine, which forms the basis for adenosine A1 receptor (A1R) antagonists as treatment for decompensated heart failure. A1R antagonists induce an eukaliuretic natriuresis and diuresis by blocking A1R-mediated NaCl reabsorption in the proximal tubule and the collecting duct. Normally, suppressing proximal reabsorption will lower glomerular filtration rate (GFR) through the tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism (TGF). But the TGF response, itself, is mediated by A1R in the pre-glomerular arteriole, so blocking A1R allows natriuresis to proceed while GFR remains constant or increases. The influence of A1R over vascular resistance in the kidney is augmented by angiotensin II while A1R activation directly suppresses renin secretion. These interactions could modulate the overall impact of A1R blockade on kidney function in patients taking angiotensin II blockers. A1R blockers may increase the energy utilized for transport in the semi-hypoxic medullary thick ascending limb, an effect that could be prevented with loop diuretics. Finally, while the vasodilatory effect of A1R blockade could protect against renal ischaemia, A1R blockade may act on non-resident cells to exacerbate reperfusion injury, were ischaemia to occur. Despite these uncertainties, the available data on A1R antagonist therapy in patients with decompensated heart failure are promising and warrant confirmation in further studies.

Keywords: Adenosine, kidney, heart failure, tubuloglomerular feedback, reabsorption, angiotensin II

INTRODUCTION

Concomitant renal dysfunction is one of the strongest risk factors for mortality in ambulatory heart failure patients [1–3]. In patients hospitalised for decompensated heart failure, worsening of renal function further predicts an adverse outcome [4]. Whereas the mechanism underlying impaired renal function may vary, therapeutic approaches that improve kidney function in these settings have a chance to improve clinical outcome. Especially in patients with worsening of renal function, volume overload, and refractoriness to classical diuretics like loop diuretics and thiazides, effective therapy of cardiorenal dysfunction is very difficult, indicating the need to better understand renal dysfunction in this setting and to develop new therapeutic strategies. As adenosine A1 receptor (A1R) antagonists make their way into the clinical arena as therapeutic agents in heart failure, it is appropriate to review the cardiorenal physiology of adenosine.

In addition to serving as the precursor to ATP, adenosine is an autocoid that binds to cell surface receptors in kidney, heart, brain, retina, and skeletal muscle to mediate various aspects of organ function. Most of these actions of adenosine revolve around local adjustments that match blood flow with energy consumption. According to this paradigm, the interstitial concentration of adenosine rises when neighboring cells are in negative energy balance. Vasodilatory adenosine A2 receptors (A2R) are activated, in turn, which adjusts blood flow to meet demand. Since the half-life and diffusion distance of adenosine are short, this is a fast and efficient means to match supply and demand over short distances within an organ. The role of adenosine in the kidney is, at the same time, analogous, yet dissimilar to, and more complicated than, its role in other organs.

In this review, we first describe the basis for a more complicated role of adenosine in the kidney and outline its differential effects on the renal cortical and medullary vascular structures, its role in tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF), the regulation of renin secretion and in transport processes in the tubular and collecting duct system. These issues are subsequently discussed with regard to a potential role of A1R as a new target in the treatment of patients with acute decompensated heart failure or cardiorenal failure. The reader is referred to relatively recent reviews on the role of adenosine in kidney function in general [5] and fluid retention in particular [6;7].

Differential vascular actions of adenosine in the kidney cortex and medulla

While blood flows to other organs to meet a demand for energy, blood that flows to the kidney generates a demand for energy. This occurs because glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is closely tied to the renal blood flow and nearly all of the glomerular filtrate must be reabsorbed, which requires energy. Hence, the way to recover from negative energy balance in the kidney is not necessarily to increase its blood flow, but to lower the filtration fraction, since this will lessen the number of sodium ions that must be transported per oxygen delivered. From the physical forces that drive glomerular filtration, it is apparent that the simplest way to lower the filtration fraction is to reduce the glomerular capillary pressure. As outlined below, the renal adenosine system employs vasoconstrictor A1R on the afferent arteriole and vasodilatory A2R on the efferent arteriole. Activating either population of glomerular adenosine receptors will suffice to reduce the filtration fraction, whereas nuances related to their relative activities will determine the impact of endogenous adenosine on single nephron GFR and glomerular blood flow.

In comparison, blood flow in the renal medulla is nutritive. It derives from the postglomerular circulation of deep nephrons and due to the way the kidney concentrates the urine, blood flow and O2 supply are low in this area although active NaCl reabsorption in the medullary thick ascending limb is essential for function. This asks for a vasodilator to prevent hypoxic injury in the renal medulla. As outlined in the following, adenosine lowers GFR but is a vasodilator in the renal medulla.

Adenosine lowers GFR via activation of A1R

Intravenous infusion of adenosine in healthy awake volunteers was found to lower GFR by ~25% while blood pressure and renal blood flow were unchanged [8;9]. Direct infusion of adenosine into the renal artery of volunteers also reduced GFR [10], indicating a primary renal site of action based on the short plasma half life of adenosine of a few seconds. Furthermore, oral application of the A1R antagonist FK-453 to healthy male subjects increased GFR by ~20% without significantly altering effective renal plasma flow or mean arterial blood pressure [11], indicating that endogenous adenosine through activation of A1R elicits a tonic suppression of GFR.

Continuous adenosine infusion into the renal artery of rats or dogs reduced single nephron GFR (SNGFR) in superficial nephrons to a larger extent than whole kidney GFR, indicating that deep-cortical vasodilation (see below) counteracts superficial vasoconstriction [12–14]. The adenosine-induced fall in SNGFR in superficial nephrons was the result of afferent arteriolar vasoconstriction with a parallel fall of the hydrostatic pressure in glomerular capillaries and in postglomerular star vessels [12;14](Figure 1). Direct videometric assessment of pre- and postglomerular arteries using the “split-hydronephrotic” rat kidney technique indicated adenosine-induced constriction of afferent arterioles via high affinity A1R and dilation via activation of both high affinity A2AR and low affinity A2bR [15]. In general, activation of A1R lead to constriction mainly of afferent arterioles near the glomerulus whereas A2R activation lead to dilation mainly of postglomerular arteries [16–18].

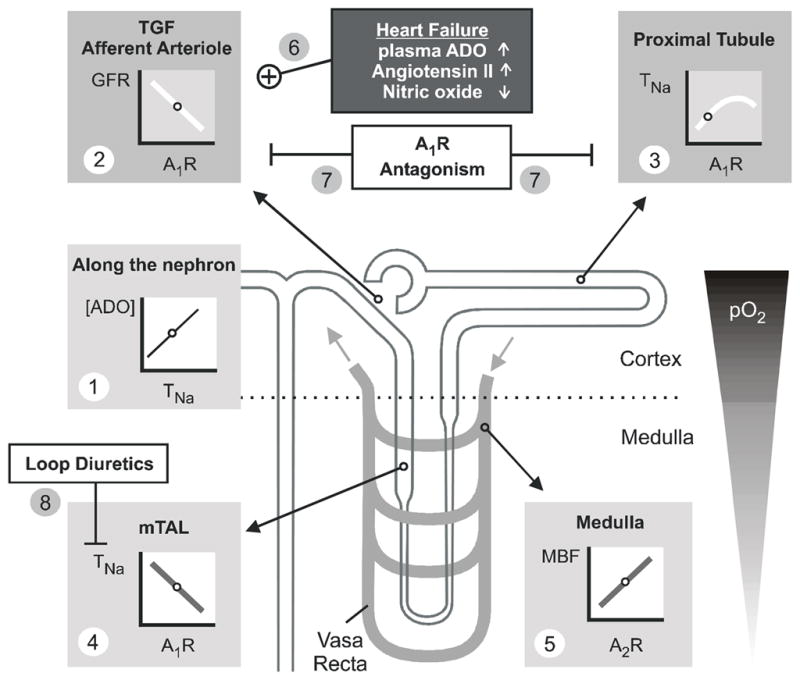

Fig. 1. Differential effects of adenosine (ADO) on renal haemodynamics and transport – basis for a therapeutical effect of A1R antagonism in heart failure.

Partial oxygen pressure (pO2) is lower in renal medulla than cortex exposing the medulla to a greater risk for hypoxic damage. The line plots illustrate the relationships between the given parameters. Small circles on these lines indicate ambient physiological conditions. (1) In every nephron segment, an increase in reabsorption or transport of sodium (TNa) increases extracellular ADO. (2) ADO via A1R mediates TGF and constricts the afferent arteriole to lower GFR. (3) In the proximal tubule, ADO via A1R stimulates TNa and thus lowers the Na+ load to segments residing in the semi-hypoxic medulla. (4) In contrast, ADO via A1R inhibits TNa in the medulla including medullary thick ascending limb (mTAL). (5) In addition, ADO via A2R enhances medullary blood flow (MBF), which increases O2 delivery and further limits O2 consuming transport in the medulla. (6) Heart failure can be associated with increased plasma concentrations of ADO and angiotensin II, and endothelial dysfunction can impair nitric oxide formation, all of which may enhance the A1R-mediated lowering of GFR. (7) A1R antagonism induces natriursesis and diuresis by inhibiting proximal reabsorption and preserving or increasing GFR. (8) A1R antagonism can enhance TNa in mTAL. This is prevented by co-administration of loop diuretics, and diuresis and natriuresis are potentiated.

Factors affecting adenosine-induced cortical vasoconstriction

Many factors and conditions affect the renal vasoconstrictor response to adenosine, which can be of clinical relevance. One prominent factor is the renin-angiotensin system. Whereas suppression of the system by high salt intake [19;20], angiotensin II AT1 receptor antagonists [21–24], or inhibitors of angiotensin I converting enzyme [17] reduces or blocks the renal vasoconstrictive action of adenosine, activation of the renin-angiotensin system potentiates adenosine-induced vasoconstriction and lowering of GFR [13;19;23]. The assumed interaction of angiotensin II and adenosine in preglomerular vessels was confirmed in dogs [25;26], and further studies revealed a mutual dependency and cooperation of adenosine and angiotensin II in producing afferent arteriolar constriction [27–29]. A significant increase in the sensitivity of the kidney to adenosine-induced vasoconstriction is also induced by inhibiting the synthesis of vasodilators like nitric oxide (NO) [30;31] or prostaglandins [32;33]. Table 1 summarizes further interactions between different conditions, drugs and hormones and the renal vasoconstriction mediated by adenosine.

Table 1.

Parallel response of adenosine (ADO)-induced renal vasoconstriction and tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF) activity to a number of different experimental conditions, drugs and hormones

| ADO-induced vasoconstriction | TGF activity | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADO | TGF | |||

| Conditions | ||||

| low salt diet, volume depletion or hemorrhage | potentiation | ↑ | [13;19] | [133–136] |

| high salt diet or volume expansion | attenuation | ↓ | [13;19] | [137] |

| Drugs/ Hormones | ||||

| theophylline or ADO A1 antagonists | inhibition | ↓ | [138] | [23;43;46;47;141] |

| calcium antagonists | inhibition | ↓ | [139] | [142–144] |

| angiotensin II blockade | inhibition | ↓ | [22;23;26] | [145] |

| NOS inhibition | potentiation | ↑ | [30] | [146–150] |

| ADO re-uptake ↓ | potentiation | ↑ | [20;140] | [23;43;151] |

| angiotensin II | potentiation | ↑ | [25;27] | [152–157] |

NOS, nitric oxide synthase;

Adenosine induces medullary vasodilation via activation of A2R

After an initial adenosine-induced vasoconstriction in all cortical zones in response to intrarenal continuous adenosine infusion in rats, the superficial cortical vasoconstriction persisted while a deep cortical vasodilation was observed [34;35]. Moreover, experiments in isolated-perfused rabbit afferent arterioles indicated that A1R-mediated afferent arteriolar constriction dominates in superficial nephrons whereas deep cortical nephrons, which supply the blood flow to the renal medulla, can respond to adenosine with A2R-mediated vasodilation [36–40]. In accordance, renal interstitial infusion of the A2R agonist CGS-21680C in rats increased medullary blood flow [41]. Moreover, infusion of the selective A2R antagonist DMPX (but not the A1R antagonist DPCPX) into the renal medulla of rats decreased medullary blood flow [42], indicating that endogenous adenosine dilates medullary vessels and sustains medullary blood flow via activation of A2R (Figure 1). Furthermore, by washing out the high osmolality in the medullary interstitium, the A2R-mediated rise in medullary blood flow lowers medullary transport activity [42].

In summary, adenosine can induce both, vasoconstriction and vasodilation in the kidney (Figure 1). Adenosine-induced vasoconstriction via A1R activation is predominant in the outer cortex by increasing the resistance of afferent arterioles, which lowers GFR and thus renal transport work. In the deep cortex and medulla, adenosine-induced vasodilation via A2R activation is associated with an increase of medullary blood flow and thus increased medullary oxygenation.

Adenosine is a mediator of tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF) via activation of A1R

The way the mammalian kidney developed to fulfill its functions in body homeostasis includes a rather high GFR (~180 l/day in human). About 99% of the filtered fluid and NaCl needs subsequently to be reabsorbed along the nephron, such that urinary excretion closely matches intake. As a consequence, GFR is a critical determinant of renal transport work, and GFR and reabsorption have to be closely coordinated to prevent renal loss or retention of fluid and NaCl. The importance of the symmetry between nephron filtration and reabsorption can be appreciated from the fact that a disparity of as little as 5 % between filtered load and the reabsorption rate would lead to a net loss of about one third of the total extracellular fluid volume within 1 day, a situation which inevitably would lead to vascular collapse. A mechanism that helps to coordinate GFR with the tubular transport activity or capacity and which contributes to the GFR lowering effect of adenosine in kidney cortex under physiological conditions, is the TGF. In this mechanism, the tubular NaCl load at the end of the thick ascending limb (TAL)(where about 85% of the filtered NaCl has been reabsorbed and 15% is left in the tubular fluid) is sensed by specialized tubular cells, the macula densa. These cells generate a signal to affect primarily afferent arteriolar tone, such that an inverse relationship is established between this tubular NaCl load and SNGFR of the same nephron. In doing so, the TGF helps to stabilize the NaCl load to further distal segments, which, under systemic neuro-humoral control, are the sites of fine regulation of NaCl and fluid balance.

Evidence for a role of adenosine and A1R in the TGF mechanism derived from studies showing that the reduction in SNGFR or glomerular capillary pressure in response to increasing the NaCl concentration at the macula densa is inhibited by unselective adenosine receptor blockers like theophylline or PSPX [43–45], as well as by selective A1R antagonists like DPCPX, KW-3902, CVT-124, or FK838 [44;46–50]. Moreover, gene-targeted mice lacking A1R also lack this TGF response [51–53], and additional experiments in this mouse model demonstrated the role of A1R - and thus TGF-mediated control of GFR in stabilizing the Na+ delivery to the distal tubule [53]. Under certain conditions, adenosine-induced vasodilation of the efferent arteriole may potentiate its vasoconstrictive effect on the afferent arteriole with regard to TGF-induced reduction of GFR [54;55]. Importantly, however, an intact TGF response requires local concentrations of adenosine to fluctuate in dependence of the NaCl concentration in the tubular fluid at the macula densa, indicating that adenosine serves as a mediator of TGF [47].

The concept that adenosine may be a mediator of TGF was first proposed by Osswald and colleagues in 1980 [43]. A current model is illustrated in Figure 2. Changes in luminal concentrations of Na+, K+ and Cl− alter NaCl uptake by macula densa cells via the furosemide-sensitive Na-K-2Cl cotransporter in the luminal membrane. This triggers basolateral ATP release [56;57] as well as transport-dependent hydrolysis by basolateral Na+-K+-ATPase [58] of ATP to AMP, the latter also being released. Plasma membrane-bound ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-1/cd39 converts ATP and ADP to AMP [59] and ecto-5′-nucleotidase/cd73 converts extracellular AMP to adenosine [47;60–62]. Part of the extracellular adenosine involved in the TGF response is generated independent of ecto-5′-nucleotidase and may reflect direct adenosine release from macula densa cells [61]. Extracellular adenosine binds to adenosine A1 receptors at the surface of extraglomerular mesangial cells [63–66] and increases cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations [65]. Because of the intensive coupling by gap junctions between extraglomerular mesangial cells and smooth muscle cells of glomerular arterioles, intracellular Ca2+ transients could be transmitted to these target structures inducing afferent arteriolar constriction [67;68]. Thus, a model is envisioned in which both ATP and adenosine would be considered mediators of TGF since both are released or generated, respectively, in dependence of the NaCl concentration at the macula densa and both are part of a signalling cascade, in which adenosine via A1R activation triggers the final effects of the TGF response, i.e., preglomerular vasoconstriction. Under physiological conditions, adenosine-induced afferent arteriolar constriction may primarily derive from tonic activation of the TGF mechanism (Table 1 shows the parallel response of adenosine-induced vasoconstriction and TGF activity to a number of different experimental conditions, drugs and hormones). The TGF induces oscillations (2–3/min) in SNGFR and thus in the NaCl load to the tubule including the medullary TAL, where NaCl is reabsorbed by furosemide-sensitive Na-K-2Cl cotransporter. Since the latter segment has to work under relative hypoxic conditions, the phases of reduced NaCl load may help to preserve the integrity of the renal medulla.

Fig. 2. Proposed mechanism of adenosine acting as a mediator of the tubuloglomerular feedback.

Left panel: Schematic drawing showing the macula densa (MD) segment located at the vascular pole with the afferent arteriole (AA) entering and the efferent arteriole (EA) leaving the glomerulus. EGM, extraglomerular mesangium; BM, glomerular basement membrane; EP, epithelial podocytes with foot processes (F); B, BS, Bowman’s capsule and space, respectively; PT, proximal tubule. (Adapted from Kriz, Nonnenmacher and Kaissling). Right panel: Schematic enlargement of area in red rectangle. Numbers in circles refer to the following sequence of events. (1), Increase in concentration-dependent uptake of Na+, K+ and Cl− via the furosemide-sensitive Na+-K+-2Cl−-cotransporter (NKCC2); (2)(3), transport-related, intra- and/or extracellular generation of adenosine (ADO); (4), extracellular ADO activates adenosine A1 receptors triggering an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ in extraglomerular mesangium cells (MC); (5), the intensive coupling between extraglomerular MC, granular cells containing renin, and smooth muscle cells of the afferent arteriole (VSMC) by gap junctions allows propagation of the increased Ca2+ signal resulting in afferent arteriolar vasoconstriction and inhibition of renin release. Factors such as nitric oxide, arachidonic acid breakdown products or angiotensin (Ang) II modulate the described cascade. NOS I, neuronal nitric oxide synthase; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2 (adapted from [5;132]).

Adenosine inhibits renin secretion via A1R activation

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system plays a central role in electrolyte homeostasis and in the regulation of blood pressure. The level of activity of this system is determined primarily by the rate at which the kidneys secrete renin into the circulation. Major stimuli that control renal renin release include the renal perfusion pressure, sympathetic nerve activation, and the NaCl concentration sensed by the macula densa in the early distal tubule. The role of adenosine in the control of renin secretion has recently been reviewed [5]. In 1970 Tagawa and Vander reported that adenosine infusion into the renal artery of salt-depleted dogs leads to a sustained inhibition of renal renin secretion into the venous blood [69]. This acute inhibitory effect of adenosine on renin release was subsequently confirmed in various species including humans [10]. The adenosine-induced inhibition of renin release is mediated by A1R as specific agonists and antagonists for this receptor type can mimic or block the inhibitory actions of exogenous adenosine on renin secretion, respectively. Most notably, a single application of the A1R antagonist FK-453 was found to increase plasma renin concentrations in humans [11] indicating a tonic inhibition of renin secretion by A1R activation. In accordance, mice lacking A1R have increased renal mRNA expression and content of renin [70] as well as greater plasma renin activity [52;71] compared with wild-type mice.

Jackson suggested that increases in intracellular cAMP in renin secreting cells cause efflux of cAMP, which activates the extracellular cAMP-adenosine pathway, i.e. cAMP is converted to adenosine in the extracellular space. The generated adenosine by acting on A1R on the renin secreting cells then acts as a negative-feedback control on renin release [72]. Besides a role for adenosine derived from renin secreting cells, further studies indicated that high NaCl concentrations in the tubular lumen enhance adenosine generation in a macula densa-dependent way and that the adenosine generated inhibits renin release via activation of A1R [73–76](Figure 2). In contrast to A1R stimulation, activation of A2R can lead to an increase of renin secretion [77;78]. Whether this stimulatory effect of adenosine A2R activation is of physiological significance remains to be determined. Indirect evidence was provided by the fact that the unselective adenosine receptor antagonist caffeine reduced plasma renin concentration in mice lacking the A1R [71].

Differential effects of adenosine on fluid and electrolyte transport

Adenosine affects fluid and electrolyte transport in the kidney indirectly through effects on renal blood flow, GFR and renin release, as well as by direct effects on the tubular and collecting duct system as reviewed recently [5].

Adenosine increases transport in proximal tubule via activation of A1R

In vitro studies showed that endogenously formed adenosine stimulates proximal tubular reabsorption of fluid, Na+, HCO3−, and phosphate by activation of A1R [79–82]. Importantly, in vivo studies in rats and humans demonstrated that systemic application of selective A1R antagonists (such as CVT-124, DPCPX, KW-3902, or FK453) elicits diuresis and natriuresis predominantly due to inhibition of reabsorption in the proximal tubule [11;83–87], indicating a tonic stimulation of proximal tubular reabsorption via A1R activation (Figure 1). Mechanisms involved in A1R-mediated increases in proximal tubular reabsorption were proposed to include increases of intracellular Ca2+ [88], reductions of intracellular cAMP levels [89], and activation of the Na+-H+-exchanger NHE3 [88], which is known to play a major role for Na+ reabsorption in proximal tubule [90].

In general, natriuretics that act proximal to the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron stimulate K+ secretion in the latter segment and thus increase renal K+ excretion. The finding that A1R antagonists do not increase renal K+ excretion suggests that A1R may also affect transport mechanisms in the distal nephron. As a consequence, selective A1R antagonists are being developed as eukaliuretic natriuretics in Na+ retaining states such as heart failure [91–93](see below). Similar to selective A1R blockade, systemic application of the unselective adenosine receptor antagonists theophylline or caffeine is known to induce natriuretic and diuretic responses. Experiments in knockout mice demonstrated that intact A1R are necessary for both caffeine- and theophylline-induced inhibition of renal Na+ and fluid reabsorption. These findings strongly suggest that A1R blockade mediates the natriuresis and diuresis in response to these compounds [94].

Adenosine inhibits transport in medullary TAL via activation of A1R

A tonic, adenosine-mediated stimulation of cortical proximal tubular reabsorption reduces the workload delivered to the medullary parts of the proximal tubule and the TAL, which pass through a kidney region in which blood flow and oxygen supply is much lower than in the cortex. In contrast to the proximal tubule, adenosine via activation of A1R can inhibit NaCl reabsorption in medullary TAL [95–97]. Medullary TAL is a site of adenosine release and adenosine release in this segment is transport-dependent [98;99] and enhanced significantly during hypoxic conditions [98]. Furthermore, studies using pharmacological inhibition [42] or gene-knockout [53] are consistent with a tonic activation of Na+ reabsorption in medullary TAL by A1R activation (Figure 1). This is relevant since the renal medulla has a low partial oxygen pressure [100] and the described inhibitory effects of adenosine on transport work together with its A2R-mediated renal medullary vasodilation (see above) may serve to maintain metabolic balance in the renal medulla.

Effects of adenosine on transport in distal convolution and cortical collecting duct

As mentioned above, the natriuretic but eukaliuretic effect of A1R inhibitors suggests an additional site of action in the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron, but the exact site of action and the involved mechanisms are unclear. There is evidence in the distal nephron that adenosine released during cell swelling may bind to A1R and activates Cl− channels in the apical membrane to restore cell volume [101;102]. One may speculate that Na+ transport-induced cell swelling in these segments activates A1R to co-activate Cl− and K+ secretion. In addition, A1R activation can stimulate Mg2+ and Ca2+ uptake in the cortical collecting duct in vitro [103–105], which is mediated by members of the transient receptor potential cation channel family, namely TRPM6 [106] and TRPV5 [107], respectively. Whether this interaction is of clinical relevance (e.g. during pharmacological inhibition of A1R) is unclear.

Adenosine can inhibit effects of vasopressin in inner medullary collecting duct

Extracellular adenosine may serve to feedback inhibit vasopressin-induced cAMP-mediated stimulation of Na+ and fluid reabsorption in the inner medullary collecting duct [108;109] and decrease vasopressin-stimulated electrogenic Cl− secretion through activation of A1R [110]. Jackson and colleagues provided evidence for the extracellular cAMP-adenosine pathway as an important source of extracellular adenosine under these conditions [111]. Again, the clinical relevance of this interaction is unclear.

To summarize, the in vitro and in vivo studies on kidney fluid and electrolyte transport indicate that under physiological conditions, endogenous adenosine by activation of A1R stimulates NaCl reabsorption in proximal tubule, which is a tubular segment with relatively high basal oxygen supply. In contrast, adenosine inhibits NaCl reabsorption in medullary TAL and IMCD, i.e., nephron segments with relatively low oxygen delivery (Figure 1). In accordance, interstitial infusion of adenosine in rat kidney decreased partial pressure of O2 in the cortex but increased it in the medulla, consistent with an important regulatory and protective role of adenosine in renal medullary O2 balance [112].

Potential role of A1R antagonists in the treatment of heart failure

As outlined above, effective therapy of cardiorenal dysfunction is very difficult, indicating the need to better understand renal dysfunction in this setting and to develop new therapeutic strategies. The mainstay of therapy for the management of fluid overload in both systemic volume overload and acute pulmonary oedema decompensated heart failure includes conventional diuretics such as loop and thiazide diuretics. However, enhanced solute excretion is often achieved at the expense of glomerular filtration. The latter may arise as a consequence of volume depletion and in the case of loop diuretics also by immediate direct preload reduction due to increased venous compliance, which by inducing systemic changes, such as activation of the sympathetic nervous system, are likely to mediate the adverse effects on renal haemodynamics [113;114].

A three-fold increase in circulating levels of adenosine has been reported in patients with chronic heart failure compared with controls (~200 vs. 60 nM)[115]. Studies in dogs with volume overload heart failure showed that myocardial adenosine release is elevated three-fold above normal dogs [116]. Whether elevated adenosine release in the failing myocardium increases circulating adenosine to an extent, which affects afferent arteriolar tone and thus GFR, is unclear. However, heart failure-associated activation of the renin-angiotensin-system and/or impairment of the local formation of NO (endothelial dysfunction) or prostaglandins can sensitize the renal vasculature to A1R-mediated vasoconstrictor and GFR-lowering effects of adenosine. In addition, impaired renal perfusion and hypoxia enhance adenosine formation within the kidney [117]. As a consequence, the normally homeostatic adenosine system may become maladaptive and overshoots with regard to the down-regulation of GFR (Figure 1). On the other hand, the renin-angiotensin system is pharmacologically blocked in most patients with heart failure, which may attenuate a sensitizing influence of angiotensin II (see below). Fluid retention is further potentiated by stimulation of NaCl and fluid reabsorption in the proximal tubule, a mechanism also mediated by A1R activation (see above). Based on this concept, pharmacological blockade of A1R could improve kidney function and fluid retention in heart failure. Since adenosine, by activation of A1R, mediates TGF, the expected TGF-induced reduction in GFR in response to inhibition of proximal reabsorption by A1R antagonists should be blunted. In accordance, a study in rats showed that A1R antagonism with KW-3902 prevented the GFR-lowering effect of the proximal diuretic benzolamide, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor [84].

Animal studies

In a pig model of systolic dysfunction and induction of chronic heart failure by pacer-induced tachycardia, Lucas et al. observed that acute application of the selective A1R antagonist BG9719 lowered pulmonary capillary wedge pressure and pulmonary vascular resistance in the absence of significant changes in mean arterial blood pressure, heart rate or cardiac output compared with vehicle controls [118]. Whereas basal creatinine clearance (Ccr) was not affected in this heart failure model, the compound increased Ccr and urinary flow rate and sodium excretion compared with vehicle control. Similar effects were described by Jackson et al. in aged, lean SHHF/Mcc-fa(cp) rats, a rodent model of hypertensive dilated cardiomyopathy in response to the same compound [114]. The rats were pretreated for 72 h before experiments with the loop diuretic furosemide to mimic the clinical setting of chronic diuretic therapy and were given 1% NaCl as drinking water to reduce dehydration/sodium depletion. Under these conditions, acute application of BG-9719 increased GFR and urinary flow rate and sodium excretion. In comparison, acute application of furosemide decreased renal blood flow and GFR and increased fractional potassium excretion. Neither drug altered afterload; however, furosemide, but not BG9719, decreased preload. Neither drug altered systolic function (+dP/dt(max)); however, furosemide, but not BG9719, attenuated diastolic function (decreased −dP/dt(max), increased tau). The authors concluded that in the setting of left ventricular dysfunction, chronic salt loading and prior loop diuretic treatment, selective A1R antagonists are effective diuretic/natriuretic agents with a favorable renal haemodynamic/cardiac performance profile [114].

Human studies

Gottlieb et al. determined the acute effects of furosemide and BG9719 on renal function in 12 patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class II to IV [91]. Mean GFR in the placebo group was 84 ml/min/1.73m2. Whereas furosemide lowered GFR to 63 ml/min/1.73m2, the latter was not affected by BG9719 (82 ml/min/1.73m2). Sodium excretion increased from 8 mEq following placebo administration to 37 mEq following BG9719 administration. In the six patients in whom it was measured, sodium excretion was 104 mEq following furosemide administration. The data showed that natriuresis is effectively induced by both furosemide and the A1R antagonist in patients with chronic heart failure, but only furosemide decreased GFR. In a follow-up study, Gottlieb et al. studied the effects of BG9719 in 63 patients catergorized as NYHA functional class II, III, or IV, which despite receiving standard therapy, including furosemide (at least 80 mg daily) and ACE inhibitors, remained oedematous [93]. This was a randomised, double-blind, ascending-dose, cross-over study, evaluating 3 doses of BG9719. Patients received 7-h infusions of placebo or 1 of 3 doses of BG9719 to yield serum concentrations of 0.1, 0.75, or 2.5 ug/ml. It was observed that BG9719 tripled urine output without inducing a decrease in GFR or potassium loss. In these same patients, furosemide increased urine output 8-fold and increased potassium excretion while reducing GFR. Importantly, when BG9719 was given in addition to furosemide, urinary sodium excretion additionally increased and GFR was not altered compared with placebo. These results indicate that A1R antagonism might preserve renal function while simultaneously promoting natriuresis during acute treatment of heart failure [93]. Similar results were more recently reported in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, two-way crossover study by Dittrich et al. using the A1R antagonist KW-3902 in 32 outpatients with congestive heart failure and impaired renal function (median GFR of 50 mL/min) [119]. Baseline GFR and renal plasma flow were assessed 3 hours before and over 8 hours following the intravenous administration of furosemide along with KW-3902 (30mg) or placebo. After a washout period of 3 to 8 days (median 6 days), the crossover portion of the study was performed. KW-3902 increased GFR by 32% and renal plasma flow by 48% compared with placebo. Notably, subjects who initially received KW-3902 had a statistically significant 10 mL/min increase in GFR when they returned for the crossover phase compared with the previous baseline. Thus, the increase in GFR persisted for several days longer than predicted by pharmacokinetics. These findings suggest that KW-3902 reset the complex network that determines kidney function in these patients and provided first evidence for potential longer-term benefits of using A1R antagonists [119]. Along these lines, a recent randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study by Greenberg et al. assessed the pharmacokinetics and clinical effects of the selective A1R antagonist, BG9928, given orally for 10 days to 50 patients with heart failure and systolic dysfunction who were receiving standard therapy [120]. BG9928 over the dose range of 3 to 225 mg/day was well tolerated and increased sodium excretion compared with placebo without causing kaliuresis or reducing renal function (assessed from adjusted creatinine clearance). These effects were maintained over the 10 day period. Moreover, BG9928 at doses of 15, 75, or 225 mg reduced body weight at the end of the study compared with placebo [120]. Natriuresis associated with preservation or improvement of GFR in response to A1R antagonism and its combination with furosemide can be of clinical relevance because in patients with heart failure, worsening renal function is associated with a prolonged duration of hospitalisation, higher in-hospital costs, and an increased risk of mortality [121;122].

Perspectives

The above described acute and short-term human studies employing A1R antagonists in patients with heart failure yielded promising results. However, considering the above outlined complexity of adenosine actions, further clinical trials with more patients are needed to show that A1R antagonism induces no adverse clinical consequences. Whereas the presented animal and human studies were acute or short-term treatments, it remains to be determined whether longer term application of A1R antagonism has beneficial effects.

If, as the classical teaching goes, angiotensin II and adenosine require each other to affect afferent arteriolar resistance (see above), then patients will respond quite differently to A1R blockade if they are already on ACE inhibitors or angiotensin AT1 receptor blockers. Nearly all patients with chronic heart failure are on the maximum tolerated doses of these compounds already. The only exceptions are those patients who are precluded based on renal failure or hyperkalaemia. The fact that patients pretreated with these compounds respond to A1R blockade with greater values of GFR relative to loop diuretic treatment [93] indicates that the mutual dependency and cooperation of adenosine and angiotensin II in producing afferent arteriolar constriction is not absolute, in the clinical setting.

Some concerns relate to the fact that, like loop diuretics, acute and chronic application of A1R antagonists can increase renin release (see above). A transient increase in plasma renin activity was also observed in response to the A1R antagonist BG9719 in a heart failure model in the pig [118]. A chronic activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system could be of relevance due to its prominent role in cardiac remodelling and the progression of heart failure [123]. However, there seems to be no immediate effect of the renin released acutely in response to A1R antagonists on blood pressure, which should be very sensitive to meaningful sudden increases in renin. On the other hand, if A1R blockade leads to later elevation of renin, that could be a normal physiologic response to a prior reduction in total body salt. However, if A1R blockade fails to increase GFR or reduce total body salt and renin goes up anyway, that rise in renin would be “pathologic”. When more data on A1R-renin interactions become available from heart failure trials, they will require interpretation with the foregoing nuances in mind.

Are there potential dangers to the kidney of A1R blockade? There is potential for A1R blockers to worsen reperfusion injury after acute renal ischaemia even though these blockers could lessen the prior probability of developing ischaemia to begin with. The worsening of ischaemia-reperfusion injury during genetic or pharmacological blockade of A1R is reflected by a heightened immune response to ischaemia-reperfusion inducing inflammation and necrosis [124]. The worsening may also relate to the fact that antagonism of A1R can impair TGF-induced oscillations and enhance reabsorption in the medullary TAL (see above), which both could affect the integrity of the semi-hypoxic medulla, although A2R-mediated medullary vasodilation should still be intact. Anyway, to attenuate medullary hypoxia, A1R antagonists may be combined with a loop diuretic, which will inhibit transport in medullary TAL (Figure 1). This combination therapy, as shown above, inhibits reabsorption in different nephron segments and induces additive diuretic effects while preserving GFR in heart failure patients (see above). The problem of exacerbating reperfusion injury apparently does not extend to toxic acute renal failure, against which A1R blockers reportedly afford prevention (for review see reference [5].)

Paradoxically, A1R agonists have also been under development as cardioprotective therapy in heart failure. Potential beneficial effects could include inhibition of the neuro-humoral axes involved in myocardial hypertrophy and remodelling by activation of cardial A1R [125]. In fact, the selective A1R agonist, 2-chloroadenosinesoine, attenuated cardiac hypertrophy, pulmonary oedema, and systolic dysfunction in a murine left ventricular pressure-overload model [126], and activation of A1R can contribute to ischaemic pre-conditioning and confers a resistance to further ischaemic insult [127]. However, the prediction of the net effect of A1R agonism on the neuron-humoral axes does not appear as straight forward as expected, since acute application of the A1R agonist, SDZ-WAG 994, in heart failure patients actually increased plasma norepinephrine concentrations [128]. Notably, in contrast to A1R antagonists, no clinical studies have been published on the use of A1R agonists in heart failure within the last 3 years. Moreover, because the negative inotropic effects of A1R agonists are enhanced in failing cardiomyocytes [129], it is possible that blockade of A1R could actually have beneficial effects on heart performance in the setting of left ventricular dysfunction.

Further studies in more patients are needed to more fully establish the acute effects of A1R antagonists on renal and cardiac function in patients with heart failure and cardiorenal failure. It will also be important to further assess whether the salutary effects observed in single-dose trials with A1R antagonists are durable. A1R blockade is a unique opportunity to lower renal vascular resistance independent of all other organs. The inability to do this is a major drawback of all vasodilator heart failure therapies that have been tried so far. This puts A1R blockade in a category all by itself. The importance of this is evident from the Guyton model, which predicts that dilating any organ other than the kidney will merely lead to salt retention and, as effective arterial filling declines, will actually reduce kidney function [130;131].

Acknowledgments

The work from our laboratories was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Institutes of Health (DK56248, DK28602, GM66232), and the American Heart Association (GiA 655232Y).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Dries DL, Exner DV, Domanski MJ, Greenberg B, Stevenson LW. The prognostic implications of renal insufficiency in asymptomatic and symptomatic patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:681–689. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00608-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahon NG, Blackstone EH, Francis GS, Starling RC, III, Young JB, Lauer MS. The prognostic value of estimated creatinine clearance alongside functional capacity in ambulatory patients with chronic congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:1106–1113. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hillege HL, Girbes AR, de Kam PJ, et al. Renal function, neurohormonal activation, and survival in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2000;102:203–210. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forman DE, Butler J, Wang Y, et al. Incidence, predictors at admission, and impact of worsening renal function among patients hospitalized with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vallon V, Muhlbauer B, Osswald H. Adenosine and kidney function. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:901–940. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00031.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Welch WJ. Adenosine A1 receptor antagonists in the kidney: effects in fluid-retaining disorders. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2002;2:165–170. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(02)00134-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Modlinger PS, Welch WJ. Adenosine A1 receptor antagonists and the kidney. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2003;12:497–502. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200309000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edlund A, Sollevi A. Renal effects of i.v. adenosine infusion in humans. Clin Physiol. 1993;13:361–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097x.1993.tb00336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balakrishnan VS, Coles GA, Williams JD. Effects of intravenous adenosine on renal function in healthy human subjects. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:F374–F381. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.271.2.F374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edlund A, Ohlsen H, Sollevi A. Renal effects of local infusion of adenosine in man. Clin Sci Colch. 1994;87:143–149. doi: 10.1042/cs0870143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balakrishnan VS, Coles GA, Williams JD. A potential role for endogenous adenosine in control of human glomerular and tubular function. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:F504–F510. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.265.4.F504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osswald H, Spielman WS, Knox FG. Mechanism of adenosine-mediated decreases in glomerular filtration rate in dogs. Circ Res. 1978;43:465–469. doi: 10.1161/01.res.43.3.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osswald H, Schmitz HJ, Kemper R. Renal action of adenosine: effect on renin secretion in the rat. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1978;303:95–99. doi: 10.1007/BF00496190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haas JA, Osswald H. Adenosine induced fall in glomerular capillary pressure. Effect of ureteral obstruction and aortic constriction in the Munich-Wistar rat kidney. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1981;317:86–89. doi: 10.1007/BF00506263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang L, Parker M, Fei Q, Loutzenhiser R. Afferent arteriolar adenosine A2a receptors are coupled to KATP in in vitro perfused hydronephrotic rat kidney. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:F926–F933. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.277.6.F926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gabriels G, Endlich K, Rahn KH, Schlatter E, Steinhausen M. In vivo effects of diadenosine polyphosphates on rat renal microcirculation. Kidney Int. 2000;57:2476–2484. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dietrich MS, Steinhausen M. Differential reactivity of cortical and juxtaglomerullary glomeruli to adenosine-1 and adenosine-2 receptor stimulation and angiotensin converting-enzyme inhibition. Microvasc Res. 1993;45:122–133. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1993.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holz FG, Steinhausen M. Renovascular effects of adenosine receptor agonists. Ren Physiol. 1987;10:272–282. doi: 10.1159/000173135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Osswald H, Schmitz HJ, Heidenreich O. Adenosine response of the rat kidney after saline loading, sodium restriction and hemorrhagia. Pflügers Arch. 1975;357:323–333. doi: 10.1007/BF00585986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arend LJ, Thompson CI, Spielman WS. Dipyridamole decreases glomerular filtration in the sodium- depleted dog. Evidence for mediation by intrarenal adenosine. Circ Res. 1985;56:242–251. doi: 10.1161/01.res.56.2.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dietrich MS, Endlich K, Parekh N, Steinhausen M. Interaction between adenosine and angiotensin II in renal microcirculation. Microvasc Res. 1991;41:275–288. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(91)90028-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spielman WS, Osswald H. Blockade of postocclusive renal vasoconstriction by an angiotensin II antagonists: evidence for an angiotensin-adenosine interaction. Am J Physiol. 1979;237:F463–F467. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1979.237.6.F463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Osswald H, Hermes H, Nabakowski G. Role of adenosine in signal transmission of tubuloglomerular feedback. Kidney Int. 1982;22 (Suppl 12):S136–S142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macias-Nunez JF, Garcia Iglesias C, Santos JC, Sanz E, Lopez-Novoa JM. Influence of plasma renin content, intrarenal angiotensin II, captopril, and calcium channel blockers on the vasoconstriction and renin release promoted by adenosine in the kidney. J Lab Clin Med. 1985;106:562–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall JE, Granger JP. Adenosine alters glomerular filtration control by angiotensin II. Am J Physiol. 1986;250:F917–F923. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1986.250.5.F917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hall JE, Granger JP, Hester RL. Interactions between adenosine and angiotensin II in controlling glomerular filtration. Am J Physiol. 1985;248:F340–F346. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1985.248.3.F340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weihprecht H, Lorenz JN, Briggs JP, Schnermann J. Synergistic effects of angiotensin and adenosine in the renal microvasculature. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:F227–F239. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1994.266.2.F227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hansen PB, Hashimoto S, Briggs J, Schnermann J. Attenuated renovascular constrictor responses to angiotensin II in adenosine 1 receptor knockout mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;285:R44–R49. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00739.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Traynor T, Yang T, Huang YG, et al. Inhibition of adenosine-1 receptor-mediated preglomerular vasoconstriction in AT1A receptor-deficient mice. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:F922–F927. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.275.6.F922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pflueger AC, Osswald H, Knox FG. Adenosine-induced renal vasoconstriction in diabetes mellitus rats: role of nitric oxide. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:F340–F346. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.276.3.F340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barrett RJ, Droppleman DA. Interactions of adenosine A1 receptor-mediated renal vasoconstriction with endogenous nitric oxide and ANG II. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:F651–F659. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.265.5.F651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pflueger AC, Gross JM, Knox FG. Adenosine-induced renal vasoconstriction in diabetes mellitus rats: role of prostaglandins. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:R1410–R1417. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.277.5.R1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spielman WS, Osswald H. Characterization of the postocclusive response of renal blood flow in the cat. Am J Physiol. 1978;235:F286–F290. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1978.235.4.F286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macias-Nunez JF, Fiksen-Olsen MJ, Romero JC, Knox FG. Intrarenal blood flow distribution during adenosine-mediated vasoconstriction. Am J Physiol. 1983;244:H138–H141. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1983.244.1.H138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miyamoto M, Yagil Y, Larson T, Robertson C, Jamison RL. Effects of intrarenal adenosine on renal function and medullary blood flow in the rat. Am J Physiol. 1988;255:F1230–F1234. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1988.255.6.F1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weihprecht H, Lorenz JN, Briggs JP, Schnermann J. Vasomotor effects of purinergic agonists in isolated rabbit afferent arterioles. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:F1026–F1033. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1992.263.6.F1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nishiyama A, Inscho EW, Navar LG. Interactions of adenosine A1 and A2a receptors on renal microvascular reactivity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;280:F406–F414. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.280.3.F406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yaoita H, Ito O, Arima S, et al. [Effect of adenosine on isolated afferent arterioles] Nippon Jinzo Gakkai Shi. 1999;41:697–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Inscho EW, Carmines PK, Navar LG. Juxtamedullary afferent arteriolar responses to P1 and P2 purinergic stimulation. Hypertension. 1991;17:1033–1037. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.17.6.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Inscho EW. Purinoceptor-mediated regulation of the renal microvasculature. J Auton Pharmacol. 1996;16:385–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-8673.1996.tb00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agmon Y, Dinour D, Brezis M. Disparate effects of adenosine A1- and A2-receptor agonists on intrarenal blood flow. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:F802–F806. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.265.6.F802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zou AP, Nithipatikom K, Li PL, Cowley AW., Jr Role of renal medullary adenosine in the control of blood flow and sodium excretion. Am J Physiol. 1999;45:R790–R798. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.3.R790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Osswald H, Nabakowski G, Hermes H. Adenosine as a possible mediator of metabolic control of glomerular filtration rate. Int J Biochem. 1980;12:263–267. doi: 10.1016/0020-711x(80)90082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Franco M, Bell PD, Navar LG. Effect of adenosine A1 analogue on tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:F231–F236. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.257.2.F231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schnermann J, Osswald H, Hermle M. Inhibitory effect of methylxanthines on feedback control of glomerular filtration rate in the rat kidney. Pflügers Arch. 1977;369:39–48. doi: 10.1007/BF00580808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schnermann J, Weihprecht H, Briggs JP. Inhibition of tubuloglomerular feedback during adenosine1 receptor blockade. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:F553–F561. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1990.258.3.F553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thomson S, Bao D, Deng A, Vallon V. Adenosine formed by 5′-nucleotidase mediates tubuloglomerular feedback. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:289–298. doi: 10.1172/JCI8761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ren Y, Arima S, Carretero OA, Ito S. Possible role of adenosine in macula densa control of glomerular hemodynamics. Kidney Int. 2002;61:169–176. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kawabata M, Ogawa T, Takabatake T. Control of rat glomerular microcirculation by juxtaglomerular adenosine A1 receptors. Kidney Int. 1998;67 (Suppl):S228–S230. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.06757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilcox CS, Welch WJ, Schreiner GF, Belardinelli L. Natriuretic and Diuretic Actions of a Highly Selective Adenosine A1 Receptor Antagonist. J Am Soc Nephrol. 999:714–720. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V104714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun D, Samuelson LC, Yang T, et al. Mediation of tubuloglomerular feedback by adenosine: evidence from mice lacking adenosine 1 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9983–9988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171317998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brown R, Ollerstam A, Johansson B, et al. Abolished tubuloglomerular feedback and increased plasma renin in adenosine A1 receptor-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;281:R1362–R1367. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.5.R1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vallon V, Richter K, Huang DY, Rieg T, Schnermann J. Functional consequences at the single-nephron level of the lack of adenosine A1 receptors and tubuloglomerular feedback in mice. Pflugers Arch. 2004;448:214–221. doi: 10.1007/s00424-004-1239-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ren YL, Garvin JL, Liu R, Carretero OA. Possible mechanism of efferent arteriole (Ef-Art) tubuloglomerular feedback. Kidney Int. 2007;71:861–866. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blantz RC, Vallon V. Tubuloglomerular feedback responses of the downstream efferent resistance: unmasking a role for adenosine? Kidney Int. 2007;71:837–839. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bell PD, Lapointe JY, Sabirov R, et al. Macula densa cell signaling involves ATP release through a maxi anion channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4322–4327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0736323100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Komlosi P, Peti-Peterdi J, Fuson AL, Fintha A, Rosivall L, Bell PD. Macula densa basolateral ATP release is regulated by luminal [NaCl] and dietary salt intake. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286:F1054–F1058. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00336.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lorenz JN, Dostanic-Larson I, Shull GE, Lingrel JB. Ouabain inhibits tubuloglomerular feedback in mutant mice with ouabain-sensitive alpha1 Na,K-ATPase. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2457–2463. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006040379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oppermann M, Friedman D, Faulhaber-Walter R, et al. Compromised tubuloglomerular feedback regulation in ecto-NTPDase1/CD39-deficient mice. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006 Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Castrop H, Huang Y, Hashimoto S, et al. Impairment of tubuloglomerular feedback regulation of GFR in ecto-5′-nucleotidase/CD73-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:634–642. doi: 10.1172/JCI21851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huang DY, Vallon V, Zimmermann H, Koszalka P, Schrader J, Osswald H. Ecto-5′-nucleotidase (cd73)-dependent and -independent generation of adenosine participates in the mediation of tubuloglomerular feedback in vivo. Am JPhysiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291:F282–F288. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00113.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ren Y, Garvin JL, Liu R, Carretero OA. Role of macula densa adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in tubuloglomerular feedback. Kidney Int. 2004;66:1479–1485. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weaver DR, Reppert SM. Adenosine receptor gene expression in rat kidney. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:F991–F995. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1992.263.6.F991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Toya Y, Umemura S, Iwamoto T, et al. Identification and characterization of adenosine A1 receptor- cAMP system in human glomeruli. Kidney Int. 1993;43:928–932. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Olivera A, Lamas S, Rodriguez-Puyol D, Lopez-Novoa JM. Adenosine induces mesangial cell contraction by an A1-type receptor. Kidney Int. 1989;35:1300–1305. doi: 10.1038/ki.1989.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Smith JA, Sivaprasadarao A, Munsey TS, Bowmer CJ, Yates MS. Immunolocalisation of adenosine A(1) receptors in the rat kidney. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;61:237–244. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00532-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Iijima K, Moore LC, Goligorsky MS. Syncytial organization of cultured rat mesangial cells. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:F848–F855. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1991.260.6.F848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ren Y, Carretero OA, Garvin JL. Role of mesangial cells and gap junctions in tubuloglomerular feedback. Kidney Int. 2002;62:525–531. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tagawa H, Vander AJ. Effects of adenosine compounds on renal function and renin secretion in dogs. Circ Res. 1970;26:327–338. doi: 10.1161/01.res.26.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schweda F, Wagner C, Kramer BK, Schnermann J, Kurtz A. Preserved macula densa-dependent renin secretion in A1 adenosine receptor knockout mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;284:F770–F777. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00280.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rieg T, Schnermann J, Vallon V. Adenosine A1 receptors determine effects of caffeine on total fluid intake but not caffeine appetite. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;555:174–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jackson EK, Raghvendra DK. The extracellular cyclic AMP-adenosine pathway in renal physiology. Annu Rev Physiol. 2004;66:571–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032102.111604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lorenz JN, Weihprecht H, He XR, Skott O, Briggs JP, Schnermann J. Effects of adenosine and angiotensin on macula densa-stimulated renin secretion. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:F187–F194. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.265.2.F187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Itoh S, Carretero OA, Murray RD. Possible role of adenosine in the macula densa mechanism of renin release in rabbits. J Clin Invest. 1985;76:1412–1417. doi: 10.1172/JCI112118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Weihprecht H, Lorenz JN, Schnermann J, Skott O, Briggs JP. Effect of adenosine1-receptor blockade on renin release from rabbit isolated perfused juxtaglomerular apparatus. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:1622–1628. doi: 10.1172/JCI114613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kim SM, Mizel D, Huang YG, Briggs JP, Schnermann J. Adenosine as a mediator of macula densa-dependent inhibition of renin secretion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005 doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00367.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Churchill PC, Churchill MC. A1 and A2 adenosine receptor activation inhibits and stimulates renin secretion of rat renal cortical slices. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1985;232:589–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Churchill PC, Bidani A. Renal effects of selective adenosine receptor agonists in anesthetized rats. Am J Physiol. 1987;252:F299–F303. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1987.252.2.F299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Takeda M, Yoshitomi K, Imai M. Regulation of Na(+)-3HCO3- cotransport in rabbit proximal convoluted tubule via adenosine A1 receptor. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:F511–F519. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.265.4.F511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tang Y, Zhou L. Characterization of adenosine A1 receptors in human proximal tubule epithelial (HK-2) cells. Receptors Channels. 2003;9:67–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cai H, Batuman V, Puschett DB, Puschett JB. Effect of KW-3902, a novel adenosine A1 receptor antagonist, on sodium-dependent phosphate and glucose transport by the rat renal proximal tubular cell. Life Sci. 1994;55:839–845. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)00567-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cai H, Puschett DB, Guan S, Batuman V, Puschett JB. Phosphate transport inhibition by KW-3902, an adenosine A1 receptor antagonist, is mediated by cyclic adenosine monophosphate. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;26:825–830. doi: 10.1016/0272-6386(95)90451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wilcox CS, Welch WJ, Schreiner GF, Belardinelli L. Natriuretic and Diuretic Actions of a Highly Selective Adenosine A1 Receptor Antagonist. J Am Soc Nephrol. 999:714–720. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V104714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Miracle CM, Rieg T, Blantz RC, Vallon V, Thomson SC. Combined effects of carbonic anhydrase inhibitor and adenosine A1 receptor antagonist on hemodynamic and tubular function in the kidney. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2007;30:388–399. doi: 10.1159/000108625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mizumoto H, Karasawa A. Renal tubular site of action of KW-3902, a novel adenosine A-1- receptor antagonist, in anesthetized rats. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1993;31(3):251–253. doi: 10.1254/jjp.61.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Knight RJ, Bowmer CJ, Yates MS. The diuretic action of 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine, a selective A-1 adenosine receptor antagonist. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;109(1):271–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13564.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.van-Buren M, Bijlsma JA, Boer P, van-Rijn HJ, Koomans HA. Natriuretic and hypotensive effect of adenosine-1 blockade in essential hypertension. Hypertension. 1993;22:728–734. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.22.5.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Di Sole F, Cerull R, Petzke S, Casavola V, Burckhardt G, Helmle-Kolb C. Bimodal acute effects of A1 adenosine receptor activation on Na+/H+ exchanger 3 in opossum kidney cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:1720–1730. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000072743.97583.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kost CK, Jr, Herzer WA, Rominski BR, Mi Z, Jackson EK. Diuretic response to adenosine A(1) receptor blockade in normotensive and spontaneously hypertensive rats: role of pertussis toxin-sensitive G-proteins. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;292:752–760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vallon V, Schwark JR, Richter K, Hropot M. Role of Na(+)/H(+) exchanger NHE3 in nephron function: micropuncture studies with S3226, an inhibitor of NHE3. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2000;278:F375–F379. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.278.3.F375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gottlieb SS, Skettino SL, Wolff A, et al. Effects of BG9719 (CVT-124), an A1-adenosine receptor antagonist, and furosemide on glomerular filtration rate and natriuresis in patients with congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:56–59. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00532-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Welch WJ. Adenosine A1 receptor antagonists in the kidney: effects in fluid-retaining disorders. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2002;2:165–170. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(02)00134-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gottlieb SS, Brater DC, Thomas I, et al. BG9719 (CVT-124), an A1 adenosine receptor antagonist, protects against the decline in renal function observed with diuretic therapy. Circulation. 2002;105:1348–1353. doi: 10.1161/hc1102.105264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rieg T, Steigele H, Schnermann J, Richter K, Osswald H, Vallon V. Requirement of intact adenosine A1 receptors for the diuretic and natriuretic action of the methylxanthines theophylline and caffeine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313:403–409. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.080432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Burnatowska-Hledin MA, Spielman WS. Effects of adenosine on cAMP production and cytosolic Ca2+ in cultured rabbit medullary thick limb cells. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:C143–C150. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1991.260.1.C143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Torikai S. Effect of phenylisopropyladenosine on vasopressin-dependent cyclic AMP generation in defined nephron segments from rat. Ren Physiol. 1987;10:33–39. doi: 10.1159/000173111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Beach RE, Good DW. Effects of adenosine on ion transport in rat medullary thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:F482–F487. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1992.263.3.F482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Beach RE, Watts BA, Good DW, Benedict CR, DuBose TD., Jr Effects of graded oxygen tension on adenosine release by renal medullary and thick ascending limb suspensions. Kidney Int. 1991;39:836–842. doi: 10.1038/ki.1991.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Baudouin-Legros M, Badou A, Paulais M, Hammet M, Teulon J. Hypertonic NaCl enhances adenosine release and hormonal cAMP production in mouse thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:F103–F109. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1995.269.1.F103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Brezis M, Rosen S. Hypoxia of the renal medulla--its implications for disease. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:647–655. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503093321006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Schwiebert EM, Karlson KH, Friedman PA, Dietl P, Spielman WS, Stanton BA. Adenosine regulates a chloride channel via protein kinase C and a G protein in a rabbit cortical collecting duct cell line. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:834–841. doi: 10.1172/JCI115662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rubera I, Barriere H, Tauc M, et al. Extracellular adenosine modulates a volume-sensitive-like chloride conductance in immortalized rabbit DC1 cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;280:F126–F145. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.280.1.F126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kang HS, Kerstan D, Dai LJ, Ritchie G, Quamme GA. Adenosine modulates Mg(2+) uptake in distal convoluted tubule cells via A(1) and A(2) purinoceptors. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;281:F1141–F1147. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.281.6.F1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hoenderop JG, Hartog A, Willems PH, Bindels RJ. Adenosine-stimulated Ca2+ reabsorption is mediated by apical A1 receptors in rabbit cortical collecting system. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:F736–F743. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.274.4.F736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hoenderop JGJ, De Pont JJHH, Bindels RJM, Willems PHGM. Hormone-stimulated Ca2+ reabsorption in rabbit kidney cortical collecting system is cAMP-independent and involves a phorbol ester-insensitive PKC isotype. Kidney Int. 1999;55:225–233. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chubanov V, Gudermann T, Schlingmann KP. Essential role for TRPM6 in epithelial magnesium transport and body magnesium homeostasis. Pflugers Arch. 2005 doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1470-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hoenderop JG, van Leeuwen JP, van der Eerden BC, et al. Renal Ca2+ wasting, hyperabsorption, and reduced bone thickness in mice lacking TRPV5. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1906–1914. doi: 10.1172/JCI19826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yagil Y. Interaction of adenosine with vasopressin in the inner medullary collecting duct. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:F679–F687. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1990.259.4.F679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yagil C, Katni G, Yagil Y. The effects of adenosine on transepithelial resistance and sodium uptake in the inner medullary collecting duct. Pflügers Arch. 1994;427:225–232. doi: 10.1007/BF00374528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Moyer BD, McCoy DE, Lee B, Kizer N, Stanton BA. Adenosine inhibits arginine vasopressin-stimulated chloride secretion in a mouse IMCD cell line (mIMCD-K2) Am J Physiol. 1995;269:F884–F891. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1995.269.6.F884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jackson EK, Mi Z, Zhu C, Dubey RK. Adenosine biosynthesis in the collecting duct. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;307:888–896. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.057166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Dinour D, Brezis M. Effects of adenosine on intrarenal oxygenation. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:F787–F791. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1991.261.5.F787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Tucker BJ, Blantz RC. Effect of furosemide administration on glomerular and tubular dynamics in the rat. Kidney Int. 1984;26:112–121. doi: 10.1038/ki.1984.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Jackson EK, Kost CK, Jr, Herzer WA, Smits GJ, Tofovic SP. A(1) receptor blockade induces natriuresis with a favorable renal hemodynamic profile in SHHF/Mcc-fa(cp) rats chronically treated with salt and furosemide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;299:978–987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Funaya H, Kitakaze M, Node K, Minamino T, Komamura K, Hori M. Plasma adenosine levels increase in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 1997;95:1363–1365. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.6.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Newman WH, Grossman SJ, Frankis MB, Webb JG. Increased myocardial adenosine release in heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1984;16:577–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(84)80645-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Nishiyama A, Miyatake A, Aki Y, et al. Adenosine A(1) receptor antagonist KW-3902 prevents hypoxia-induced renal vasoconstriction. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;291:988–993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lucas DG, Jr, Hendrick JW, Sample JA, et al. Cardiorenal effects of adenosine subtype 1 (A1) receptor inhibition in an experimental model of heart failure. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;194:603–609. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(02)01136-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Dittrich HC, Gupta DK, Hack TC, Dowling T, Callahan J, Thomson S. The effect of KW-3902, an adenosine A1 receptor antagonist, on renal function and renal plasma flow in ambulatory patients with heart failure and renal impairment. J Card Fail. 2007;13:609–617. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Greenberg B, Thomas I, Banish D, et al. Effects of multiple oral doses of an A1 adenosine antagonist, BG9928, in patients with heart failure: results of a placebo-controlled, dose-escalation study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:600–606. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Krumholz HM, Chen YT, Vaccarino V, et al. Correlates and impact on outcomes of worsening renal function in patients > or =65 years of age with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2000;85:1110–1113. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)00705-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Weinfeld MS, Chertow GM, Stevenson LW. Aggravated renal dysfunction during intensive therapy for advanced chronic heart failure. Am Heart J. 1999;138:285–290. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70113-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Schrier RW, Abraham WT. Hormones and hemodynamics in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:577–585. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908193410806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Lee HT, Xu H, Nasr SH, Schnermann J, Emala CW. A1 adenosine receptor knockout mice exhibit increased renal injury following ischemia and reperfusion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286:F298–F306. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00185.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kitakaze M, Hori M. Adenosine therapy: a new approach to chronic heart failure. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2000;9:2519–2535. doi: 10.1517/13543784.9.11.2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Liao Y, Takashima S, Asano Y, et al. Activation of adenosine A1 receptor attenuates cardiac hypertrophy and prevents heart failure in murine left ventricular pressure-overload model. Circ Res. 2003;93:759–766. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000094744.88220.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Riksen NP, Smits P, Rongen GA. Ischaemic preconditioning: from molecular characterisation to clinical application--part I. Neth J Med. 2004;62:353–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Bertolet BD, Anand IS, Bryg RJ, et al. Effects of A1 adenosine receptor agonism using N6-cyclohexyl-2′-O-methyladenosine in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. Circulation. 1996;94:1212–1215. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.6.1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Borst MM, Szalai P, Herzog N, Kubler W, Strasser RH. Transregulation of adenylyl-cyclase-coupled inhibitory receptors in heart failure enhances anti-adrenergic effects on adult rat cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;44:113–120. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00197-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Guyton AC, Coleman TG, Granger HJ. Circulation: overall regulation. Annu Rev Physiol. 1972;34:13–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.34.030172.000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Guyton AC. Arterial Pressure and Hypertension. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Vallon V. Tubuloglomerular feedback and the control of glomerular filtration rate. News Physiol Sci. 2003;18:169–174. doi: 10.1152/nips.01442.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Moore LC, Mason J. Perturbation analysis of tubuloglomerular feedback in hydropenic and hemorrhaged rats. Am J Physiol. 1983;245:F554–F563. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1983.245.5.F554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Kaufman JS, Hamburger RJ, Flamenbaum W. Tubuloglomerular feedback response after hypotensive hemorrhage. Ren Physiol. 1982;5:173–181. doi: 10.1159/000172854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Moore LC, Mason J. Tubuloglomerular feedback control of distal fluid delivery: effect of extracellular volume. Am J Physiol. 1986;250:F1024–F1032. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1986.250.6.F1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Selen G, Muller-Suur R, Persson AE. Activation of the tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism in dehydrated rats. Acta Physiol Scand. 1983;117:83–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1983.tb07181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Persson AE, Schnermann J, Wright FS. Modification of feedback influence on glomerular filtration rate by acute isotonic extracellular volume expansion. Pflügers Arch. 1979;381:99–105. doi: 10.1007/BF00582339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Osswald H. Renal effects of adenosine and their inhibition by theophylline in dogs. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1975;288:79–86. doi: 10.1007/BF00501815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Arend LJ, Haramati A, Thompson CI, Spielman WS. Adenosine-induced decrease in renin release: dissociation from hemodynamic effects. Am J Physiol. 1984;247:F447–F452. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1984.247.3.F447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Osswald H. Adenosine and renal function. In: Berne RM, Rall TW, Rubio R, editors. Regulatory function of adenosine. Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers; 1983. pp. 399–418. [Google Scholar]

- 141.Schnermann J. Effect of adenosine analogues on tubuloglomerular feedback responses. Am J Physiol. 1988;255:F33–F42. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1988.255.1.F33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Casellas D, Moore LC. Autoregulation and tubuloglomerular feedback in juxtamedullary glomerular arterioles. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:F660–F669. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1990.258.3.F660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Navar LG, Carmines PK, Mitchell KD, Bell PD. Role of intracellular calcium in the regulation of renal hemodynamics. Proceedings of the 11th International Congress on Nephrology; New York: Springer; 1991. pp. 718–730. [Google Scholar]

- 144.Mitchell KD, Navar LG. Tubuloglomerular feedback responses during peritubular infusions of calcium channel blockers. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:F537–F544. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1990.258.3.F537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Welch WJ, Wilcox CS. Feedback responses during sequential inhibition of angiotensin and thromboxane. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:F457–F466. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1990.258.3.F457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Thorup C, Persson AEG. Inhibition of locally produced nitric oxide resets tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:F606–F611. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1994.267.4.F606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Wilcox CS, Welch WJ, Murad F, et al. Nitric oxide synthase in macula densa regulates glomerular capillary pressure. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1992;89:11993–11997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.11993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Itoh S, Ren Y. Evidence for the role of nitric oxide in macula densa control of glomerular hemodynamics. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:1093–1098. doi: 10.1172/JCI116615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Vallon V, Thomson S. Inhibition of local nitric oxide synthase increases homeostatic efficiency of tubuloglomerular feedback. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:F892–F899. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1995.269.6.F892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Vallon V, Traynor T, Barajas L, Huang YG, Briggs JP, Schnermann J. Feedback control of glomerular vascular tone in neuronal nitric oxide synthase knockout mice. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:1599–1606. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1281599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Vallon V, Osswald H. Dipyridamole prevents diabetes-induced alterations of kidney function in rats. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1994;349:217–222. doi: 10.1007/BF00169840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]