Abstract

Epilepsy is a complex disease, characterized by the repeated occurrence of bursts of electrical activity (seizures) in specific brain areas. The behavioral outcome of seizure events strongly depends on the brain regions that are affected by overactivity. Here we review the intracellular signaling pathways involved in the generation of seizures in epileptogenic areas. Pathways activated by modulatory neurotransmitters (dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin), involving the activation of extracellular-regulated kinases and the induction of immediate early genes (IEGs) will be first discussed in relation to the occurrence of acute seizure events. Activation of IEGs has been proposed to lead to long-term molecular and behavioral responses induced by acute seizures. We also review deleterious consequences of seizure activity, focusing on the contribution of apoptosis-associated signaling pathways to the progression of the disease. A deep understanding of signaling pathways involved in both acute- and long-term responses to seizures continues to be crucial to unravel the origins of epileptic behaviors and ultimately identify novel therapeutic targets for the cure of epilepsy.

Keywords: Fos, ERK, activity-dependent transcription, seizure, apoptosis, hippocampus

Behavioral Manifestations of Seizures and Epilepsy

Epilepsy is one of the most common neurological disorders, characterized by the repeated occurrence of sudden and transitory episodes of motor, sensory, autonomic, and psychic origin, known as seizures. Seizures typically arise in restricted regions of the brain and may remain confined to these areas (“focal” or “partial” seizures) or spread to the whole cerebral hemispheres (“generalized” seizures). The behavioral outcome of seizure events depends on the brain regions that are affected by overactivity. This is clearly exemplified by the behavioral manifestations of temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), which represents one of the most common forms of human epilepsy. In TLE, focal seizures arise in a restricted part of the limbic system (temporal lobe: hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus, and amygdala). If paroxysmal activity remains confined to the area of onset (“simple partial” seizure), the seizure may be characterized by auditory, gustatory, olfactory, visual, or somatosensory hallucinations (auras), accompanied by psychic sensations such as euphoria, fear, and anger. The seizure may also spread to a larger portion of the temporal lobe (“complex partial” seizure), resulting in impaired consciousness, motionless staring, motor automatisms of the hands or mouth, altered speech, and other unusual behaviors. Finally, partial seizures arising in the temporal lobe may subsequently spread to the whole brain (“secondarily generalized tonic–clonic” seizures or “grand mal” seizures). These seizures begin with symptoms of a partial seizure followed by whole-body convulsions (Berg et al., 2010).

Temporal lobe epilepsy can be reproduced in laboratory animals (typically rodents) by the systemic or intracerebral administration of powerful convulsant agents such as glutamatergic (kainic acid) or cholinergic (pilocarpine) agonists (Pitkänen et al., 2005). According to the classical scale originally proposed by Racine (1972), experimental seizures evoked in the temporal lobe in rodents can be scored on the basis of specific behaviors that correspond to different brain regions impacted by seizure activity. Stages from 1 to 3 are characterized by behavioral signs of focal seizure activity restricted to the temporal lobe (hippocampal formation, entorhinal cortex, and amygdala): immobility, rigid posture, forelimb and/or tail extension, repetitive movements, and head bobbing. When activity generalizes and spreads to cerebral hemispheres, isolated limbic motor seizures (forelimb clonus with rearing and falling; stage 4) or continuous convulsive activity (status epilepticus, stages 5–6: continuous rearing and falling, whole-body tonic–clonic convulsions) occur. Electroencephalographic (EEG) and metabolic mapping studies confirmed these behavioral observations. EEG analysis of experimentally induced limbic seizures showed that epileptic activity sequentially appears in forebrain areas, starting from the hippocampus and then spreading to the amygdala, and cerebral cortex (Lothman et al., 1981; Turski et al., 1989). Consistent with these results, glucose utilization studies in rodents at different times after limbic seizure induction revealed a progressive increase in several forebrain areas, starting in the hippocampus, amygdala, and other limbic areas and then diffusing to cerebral cortical areas (Lothman and Collins, 1981; Clifford et al., 1987).

In the past 25 years, a large series of studies addressed the crucial issue of how neurons transduce pathological electrical activity from their membrane to the nucleus, resulting in both short- and long-term rearrangements that modify neuronal connectivity in the epileptic brain and, ultimately, brain function, and behavior. Many of these mechanisms are now well characterized, whereas others still remain to be clearly understood. In the following sections, we will describe some of the major signaling pathways involved in short- and long-term cellular responses to seizure activity that are thought to underlie acute and chronic behaviors in the epileptic brain.

The Acute Cellular Response to Seizures: Activation of Immediate Early Genes

The first demonstration that pathological overactivity can modify gene expression in the brain came from the pioneering studies by J. I. Morgan and T. Curran, who showed that metrazole-induced seizures markedly induce c-fos mRNA expression in several areas of the rodent brain (Morgan et al., 1987). These authors first introduced the concept that neurons largely use the rapid activation of “immediate early genes” (IEGs; usually transcription factors, such as Fos and Jun) to couple acute and long-term responses to physiological as well as pathological stimuli (Morgan and Curran, 1989, 1991a). Induction of activity-regulated transcription factors is a general phenomenon occurring in neurons after acute seizures (Morgan and Curran, 1991b; Herrera and Robertson, 1996; Hughes et al., 1999). However, c-fos certainly remains the prototypical and well characterized activity-dependent transcription factor, and its induction is widely considered a suitable marker of neuronal activity. As originally demonstrated using fos-lacZ transgenic mice, seizures induce c-fos mRNA transcription in defined neuronal populations at different times (Smeyne et al., 1992). These observations have been confirmed by several studies using c-fos mRNA in situ hybridization or c-Fos immunostaining on rodent brain sections as a way to perform activity mapping studies after seizures. A precise correlation exists between the pattern of c-fos induction and the progression of seizures from focal to generalized. Focal epileptic activity stimulates c-fos mRNA and c-Fos protein induction only in a few limbic areas, typically initiating in granule cell layer of the dentate gyrus and then spreading to CA3 and CA1 pyramidal layers. Then, when activity generalizes and limbic motor seizures and status epilepticus occur, a widespread c-fos mRNA and c-Fos protein expression is detected throughout the whole cerebral cortex and several other brain areas (Barone et al., 1993; Willoughby et al., 1997; Bozzi et al., 2000; Tripathi et al., 2008). More recent findings suggest that the increased level of phosphorylated ERK (pERK) could be one of the earliest immunohistochemical indicators of neurons that are activated at the time of a spontaneous seizure (Houser et al., 2008). In spontaneously epileptic animals, a marked increase in pERK labeling occurred at the time of spontaneous seizures and was evident in large populations of neurons at very short intervals (as early as 2 min) after detection of a behavioral seizure.

The intracellular signaling cascades involved in IEGs activation in both physiological and pathological conditions have been extensively investigated in neurons. So far, the pathways involved in c-fos induction remain the best characterized and can be briefly summarized as a prototypical example of activity-dependent neuronal gene transcription. Neuronal depolarization leads to increased intracellular levels of the second messengers cAMP (typically, following neurotransmitter/neuromodulator binding to G-protein coupled receptors) and Ca2+ (e.g., due to ion channel opening following glutamate binding to glutamate receptors). Both these two second messengers activate intracellular kinases [protein kinase A and extracellular-regulated kinases (ERK)] whose activity converges on the phosphorylation of the transcription factor CREB (cAMP response element binding protein, constitutively present in the nucleus). In turn, CREB phosphorylation activates c-fos mRNA transcription. c-fos mRNA is then translated into the c-Fos protein, that acts as a transcription factor for a wide variety of neuron-specific genes (reviewed in West et al., 2002; Flavell and Greenberg, 2008). This mechanism is rapid, and allows neurons to fast couple depolarizing stimuli to a wide variety of intracellular long-lasting responses, including the induction of genes involved in synaptic plasticity and cell death (see below).

Intracellular cascades activated by seizures are largely overlapping those involved in synaptic plasticity, and more specifically in long-term memory (that requires IEGs induction and new protein synthesis). These cascades have been widely studied in the hippocampus, that is crucially involved in learning and memory, but is also one of the most epileptogenic brain areas. From these studies it emerges that hippocampal neurons use the same signaling pathways to respond to both physiological and pathological stimuli. However, these pathways are harmful only when activated by seizures and not physiological neuronal activity. Different types of activity pattern might elicit physiological or pathological responses of hippocampal neurons. For example, only epileptogenic stimuli (such as kainic acid and pilocarpine), but not other types of electrical stimulation, are able to rapidly (3 h) induce dendritic accumulation of BDNF mRNA and protein in hippocampal neurons (Tongiorgi et al., 2004), a change that is thought to contribute to the pro-epileptogenic action of BDNF (Simonato et al., 2006).

Signaling Pathways Acutely Induced by Seizures: The Role of Neuromodulators

Seizures have been traditionally characterized as an imbalance between excitatory (glutamatergic) and inhibitory (GABAergic) transmission. The role of glutamate, GABA, and their respective signaling pathways in seizures and epilepsy has been extensively addressed in the literature (see for example McNamara et al., 2006; Ben-Ari et al., 2007) and will not be further reviewed here. Instead, we focus on the role that neuromodulatory systems have been shown to regulate seizure activity. The activities of dopamine, noradrenaline, and serotonin systems in modulating seizure threshold have been widely investigated, and all these neuromodulators have been shown to positively or negatively regulate the generation of seizures, depending on the receptors involved. However, the nature of the coupling of their receptors to intracellular signal transduction and, in particular, the induction of IEGs is still being investigated. Here, we describe the current state of knowledge of cell signaling pathways activated by neuromodulators and involved in seizure onset and propagation.

Catecholamines: Dopamine and noradrenaline

The role of catecholamines (dopamine and noradrenaline) in the control of seizure onset and propagation has been widely addressed in experimental, clinical, and therapeutic studies (Starr, 1993, 1996; Weinshenker and Szot, 2002; Giorgi et al., 2004). However, the topic has received very little attention regarding the underlying signaling pathways activated by seizures. No data are available on the signaling cascades downstream of noradrenaline receptors during seizures, with the exception of a recent study addressing the role of noradrenergic neurons of the locus coeruleus (LC) in limbic seizure activity. LC neurons densely innervate limbic areas of the brain, greatly contributing to control seizure activity. LC neurons play an important role in determining IEG expression following seizures. Indeed, LC lesion markedly reduces seizure-induced Fos expression in the hippocampus, indicating that noradrenergic inputs to the limbic system positively control IEG transcription during seizures (Giorgi et al., 2008).

More studies instead investigated the signaling pathways downstream of dopamine receptors that might contribute to limbic seizure onset and spread. Dopamine acts through two different types of G-protein coupled receptors, named D1-like and D2-like receptors. Activation of D1-like (D1 and D5) receptors results in reduction of seizure threshold and increased seizure severity (DeNinno et al., 1991). Administration of a sub-threshold dose of pilocarpine in the presence of D1 receptor agonists has been shown to induce seizures (Starr and Starr, 1993). Conversely, the effect of D2-like (including D2, D3, and D4) receptors on seizure modulation is predominantly inhibitory. Administration of D2-like receptor agonists results in lower seizure activity, whereas blockade or genetic inactivation of these receptors has pro-convulsant effects (Starr, 1993, 1996; Bozzi et al., 2000; An et al., 2004; Bozzi and Borrelli, 2002, 2006).

The canonical pathway of dopamine receptor activity in neurons involves modulation of adenylate cyclase (AC) to regulate cAMP production and subsequent activation of protein kinase A (PKA). D1-like receptors are coupled to Gs/olf proteins and stimulate AC, leading to increased levels of the second messenger cAMP. Conversely, D2-like receptors are coupled to Gi/o proteins and inhibit AC, decreasing cAMP production (Callier et al., 2003). Pharmacological and targeted gene knockout studies provided some insight into the profile of these pathways explicitly in seizures. It appears that specific receptor coupling to AC may be critical in seizure induction by D1-like receptors (O'Sullivan et al., 2005). Stimulation of phospholipase C (PLC) signaling, however, does not appear to have any effect on seizure threshold (Clifford et al., 1999) and is associated with more subtle behaviors. Dopamine and cAMP-regulated phosphoprotein of 32 kDa (DARPP-32) has been identified as one of the critical downstream targets of dopamine and PKA. PKA-catalyzed phosphorylation activates DARPP-32, converting it into an inhibitor of protein phosphatase-1 (PP-1). Specifically, casein kinase 1 (CK1) promotes the activation of DARPP-32 by reducing calcineurin-dependent dephosphorylation at the PKA site. Phosphorylated DARPP-32, by inhibiting PP-1, acts together with other protein kinases (mainly PKA and PKC) to increase the level of phosphorylation of a number of downstream effector proteins, including GABA and glutamate receptors, Ca2+ and Na+ channels, and the transcription factor CREB (Greengard et al., 1999; Greengard, 2001). DARPP-32 phosphorylation was observed in mice treated with D1-like receptor agonists and this elevation correlated with seizure behavior (O'Sullivan et al., 2008). The crucial role of DARPP-32 in mediating dopaminergic control of seizures was highlighted by the observation that seizure behaviors were absent or greatly reduced in DARPP-32 knockout mice (O'Sullivan et al., 2008).

As outlined previously, D2-like receptor stimulation appears to have an antagonistic effect to D1-like stimulation. Also acting on AC, it can inhibit the activity of cAMP and reduce PKA activation (Missale et al., 1998). Moreover, D2 receptor (D2R) activation has been shown to downregulate DARPP-32 activity (Nishi et al., 1997). Recent evidence, however, suggests a role of an alternative pathway in D2R-modulated seizure behavior. Studies in the striatum suggested that a cAMP-independent pathway involves the formation of a signaling complex composed of D2R, Akt, protein phosphatase-2A (PP2A), and β-arrestin 2. Activation of this pathway following binding of dopamine to D2R results in dephosphorylation of Akt (inactivation), followed by dephosphorylation (activation) of glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β; Beaulieu et al., 2005, 2007). Similar activation of GSK-3β was observed in the hippocampus following KA administration in D2R knockout (D2R−/−) mice (Tripathi et al., 2010), suggesting that upregulation of GSK-3β activity might contribute to increased susceptibility to seizure-induced cell death observed in these mice. Indeed, activation of GSK-3β has been implicated in neuronal cell death (Kaytor and Orr, 2002). Importantly, GSK-3β upregulation was independent of any change in Akt in D2R−/− mice following seizures (Tripathi et al., 2010), implicating that alternative pathways might contribute to modulate GSK-3β in the hippocampus during epileptic activity. p38MAPK and Wnt pathways have both been implicated as potential alternative pathways in regulating GSK-3β activity (Thornton et al., 2008; Inestrosa and Arenas, 2010), but require further investigation in the context of seizures.

In addition to its direct role on glutamatergic excitation (see above), ERK signaling is also believed to play an integral role in D1- and D2-type receptor signaling. Upregulation of ERK and increased phosphorylation of the ribosomal protein S6 and histone H3 (two downstream targets of ERK) were detected in the granule cell layer of the dentate gyrus, in response to brief seizures evoked by D1 specific agonists; these effects were prevented by genetic inactivation of D1 receptor, or by pharmacological inhibition of ERK (Gangarossa et al., 2011). Importantly, D1 receptor-mediated ERK upregulation disappeared within 60 min and correlated with seizure activity (Gangarossa et al., 2011). This is in contrast to kainic acid or pilocarpine-induced ERK upregulation, which can persist for hours (Kim et al., 1994; Berkeley et al., 2002). Thus, brief or long-lasting ERK activation in selective epileptogenic areas of the brain might contribute to activate signaling pathways in response to different seizure-promoting stimuli, as well as different types of seizure behaviors. Spontaneous chronic seizures following pilocarpine treatment rapidly induce ERK phosphorylation in the dentate gyrus specifically in a subpopulation of cells in the subgranular zone, that were identified as proliferating radial glia-like neural precursors (Li et al., 2010b). The functional significance of ERK activation, and its link with the detrimental or beneficial effects of seizure-induced neurogenesis (Kokaia, 2011), remain to be clarified.

Seizure-induced ERK activation seems to be controlled also by D2R-dependent pathways. Following kainic acid treatment, more rapid and longer-lasting ERK phosphorylation is detected in the hippocampus of D2R−/− mice, as compared to wild-type controls (Yuri Bozzi, unpublished observations). Downstream of ERK, the induction of IEGs is a critical effector step and has been extensively studied in seizure models (see above). D1-type receptor agonists increase the levels of Zif268 and Arc/Arg3.1 (two IEGs involved in transcriptional regulation and synaptic plasticity) in the dentate gyrus, with a time course that parallels that of ERK phosphorylation (Gangarossa et al., 2011).

Studies performed in D2R−/− mice confirm that dopaminergic innervation to the hippocampus plays a crucial role in seizure-induced IEGs induction. Experimentally induced seizures in these mice result in a more prominent upregulation of c-fos and c-jun mRNAs in the hippocampus, as compared to wild-type controls (Bozzi et al., 2000). As observed following administration of D1 agonists in wild-type mice (Gangarossa et al., 2011), seizure-induced IEGs upregulation in D2R−/− mice was transient in the dentate gyrus (Bozzi et al., 2000), confirming the critical role of this structure in mediating the first steps of dopamine-dependent control of hippocampal activity during seizures.

Serotonin

Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) acts through a family of predominantly G-protein coupled receptors to modulate neuronal excitability (Barnes and Sharp, 1999; Hannon and Hoyer, 2008). Activation of 5-HT receptors by administration of 5-HT agonists or reuptake inhibitors can inhibit focal and generalized seizures, while destruction of serotonergic terminals and depletion of brain 5-HT results in reduction of seizure threshold and increased neuronal excitability in experimental models (Bagdy et al., 2007). More recently, increased threshold to kainic acid-induced seizures was observed in mice with genetically increased 5-HT levels (Tripathi et al., 2008).

Despite the well established role of 5-HT in seizure modulation, the receptor subtypes and signaling pathways through which 5-HT exerts its effect are not well characterized. Fourteen mammalian 5-HT receptor subtypes are currently recognized, and these have been classified into seven receptor families on the basis of their structural, functional and, to some extent, pharmacological characteristics (Barnes and Sharp, 1999; Hannon and Hoyer, 2008). Among these receptors, the 5-HT1A and 5-HT2C subtypes, which are expressed in epileptogenic brain areas (mainly, cerebral cortex and/or hippocampus), appear to be the most relevant in epilepsy (Bagdy et al., 2007). For example, increased seizure severity is observed in mice with targeted inactivation of the 5-HT1A or 5-HT2C genes (Tecott et al., 1995; Brennan et al., 1997; Sarnyai et al., 2000). However, it must be noted that pharmacological studies using the 5-HT1 or 5-HT2 specific agonist/antagonists failed to give a clear evidence of the general role played by these receptors in seizure modulation: contrasting results were obtained depending on the experimental seizure models used to test the anti- or pro-convulsant effect of different ligands. A detailed description of these findings is beyond the scope of this review and the reader is referred to more comprehensive previous studies (Bagdy et al., 2007).

Similar to dopamine, most of 5-HT receptors act on the AC/cAMP/PKA pathway. The only exceptions are 5-HT2 receptors (that modulate PLC) and the 5-HT3A receptor (a ligand-gated ion channel; Bockaert et al., 2006; Hannon and Hoyer, 2008). 5-HT receptor signaling modulates IEGs induction in response to excitatory glutamatergic stimuli, such as those resulting from seizure activity. For example, the induction of Arc/Arg3.1 and c-fos in cortical neuronal populations following treatment with DOI (a 5-HT2 receptor agonist) is critically dependent on glutamate receptor activation (Pei et al., 2004). As regarding the neuromodulatory role of 5-HT on intracellular signaling pathways acutely induced by seizures, it is interesting to note that activation of the 5-HT2/PLC pathway leads to phosphorylation of DARPP-32 (Svenningsson et al., 2002). The observation that pharmacological and genetic manipulations of 5-HT2 receptors modulate seizure activity (see above; Bagdy et al., 2007) suggests that DARPP-32 may act as a converging point of the neuromodulatory action of both dopamine and 5-HT in seizure-induced signaling cascades.

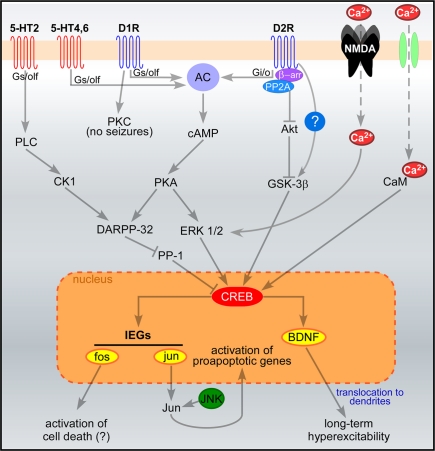

Figure 1 summarizes the major signaling pathways downstream of dopamine and 5-HT receptors in the early response to seizures.

Figure 1.

Signaling pathways acutely activated in hippocampal neurons following seizures. Pathways downstream of glutamate, serotonin and dopamine receptors are illustrated. Seizures induce massive influx of Ca2+ through NMDA receptors and voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (in green), leading to CREB phosphorylation via ERK and calmodulin-dependent signaling, respectively (West et al., 2002). Serotonin and dopamine signaling modulate seizure-induced CREB phosphorylation via the activation of DARPP-32 and ERK1/2. Once phosphorylated, CREB promotes the transcription of activity-dependent genes such as BDNF and the IEGs fos and jun. The sustained induction of jun has been shown to switch on apoptotic cascades, whereas the pro-apoptotic role of fos induction has been questioned. Dendritic localization of BDNF mRNA and protein may also contribute to long-term excitability. The proposed scheme is a general (though not complete) summary of the intracellular pathways induced by seizures in the hippocampus. All the reported serotonin and dopamine receptor subtypes are expressed in the hippocampus, together with their signaling proteins (Meador-Woodruff et al., 1991; Perez and Lewis, 1992; Hannon and Hoyer, 2008). However, important differences may occur in different types of hippocampal neurons (e.g., dentate granule cells, pyramidal neurons), due to the different expression levels of these proteins. Abbreviations: AC, adenylate cyclase; CaM, calmodulin; CK1, casein kinase 1; DARPP-32, dopamine and cAMP-regulated phosphoprotein of 32 kDa; D1R and D2R, dopamine receptors (D1 and D2 subtypes); ERK, extracellular-regulated kinase; GSK-3β, glycogen synthase kinase 3β; IEGs, immediate early genes; JNK, Jun-terminal kinase; NMDA, NMDA glutamate receptors; PKA, protein kinase A; PKC, protein kinase C; PLC, phospholipase C; PP-1, protein phosphatase 1; 5-HT, serotonin receptors. Question marks indicate that some pathways have been proposed but not clearly demonstrated.

Seizure-Induced Cell Death: Intrinsic and Extrinsic Pathways

Studies performed in both experimental models and findings in humans support the notion that seizures can be damaging to the brain. In particular, if seizures are prolonged (status epilepticus) or repeatedly evoked they can cause neuronal death, particularly within vulnerable brain regions such as the hippocampus. Cell death is a common pathologic feature of insults to the brain which trigger a chronic epileptic condition (Pitkanen and Sutula, 2002). The main mechanism by which neurons die after seizures is excitotoxicity due to prolonged over-activation of ionotropic glutamate receptors (Choi, 1988; Meldrum, 1991; Fujikawa, 2005). An appreciation of the complex molecular pathways lying downstream of glutamate receptor over-activation has emerged, alongside evidence that glutamate receptor antagonists do not block all cell death after seizures (Bengzon et al., 1997).

Several studies have addressed the role of IEGs in seizure-induced cell death (Herdegen and Leah, 1998). The prolonged activation of the IEGs c-fos and c-jun after acute seizures was originally proposed as one of the crucial steps that trigger long-term neuronal death (Smeyne et al., 1993; Kasof et al., 1995; Kondo et al., 1997). In physiological conditions, IEGs are essential for normal neuronal responses to excitation in the brain. The protein products of fos/jun contribute to assembly of the AP-1 transcription factor, whose activation regulates the expression of a wide number of “synaptic” genes, including neurotrophic factors (Sheng and Greenberg, 1990). Indeed, loss of c-fos in mice markedly reduces activity-dependent structural plasticity (mossy fiber sprouting; Watanabe et al., 1996). This suggests that such a “fos-less phenotype” might be due to altered seizure-induced transcriptional activation of genes involved in synaptic plasticity (Watanabe et al., 1996). However, the role of c-fos as a promoting agent of seizure-induced neuronal cell death has been questioned by the observation that conditional mutant mice lacking c-fos in the hippocampus display increased susceptibility to seizure-dependent neuronal loss (Zhang et al., 2002). Conversely, the pro-apoptotic activity of c-jun activation has been confirmed in several experimental models. Increased levels of both c-jun mRNA and Jun phosphorylation are observed in epileptogenic areas after seizures (Huges et al., 1999; Raivich and Behrens, 2006). Phosphorylation of Jun is mediated by the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and results in the subsequent activation of Jun transcriptional activity, that triggers apoptotic neuronal cell death after seizures (Herdegen et al., 1998; Behrens et al., 1999; Mielke et al., 1999; Schauwecker, 2000; Spigolon et al., 2010) and other traumatic insults (Yuan and Yankner, 2000). Accordingly, mice lacking the Jun-terminal kinase Jnk3 are protected against seizure-induced apoptosis in the hippocampus (Yang et al., 1997).

Apoptosis-associated signaling pathways are important components of the molecular response to seizures (Engel and Henshall, 2009). Complex intracellular and intercellular cell death-regulatory pathways are increasingly recognized as important contributors to seizure-induced neuronal death. Here, we review the latest findings on apoptosis-associated signaling pathways, in particular the role of Bcl-2 family proteins, as critical components of the molecular response to seizures.

Apoptosis is a form of programmed cell death that is orchestrated by evolutionarily-conserved signaling pathways. Two main pathways have been identified. The intrinsic pathway is activated by various intracellular stressors such as DNA damage, perturbed intracellular organelle function (for example, prolonged endoplasmic reticulum stress), and loss of calcium homeostasis (Orrenius et al., 2003; Xu et al., 2005). Ultimately, this results in mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) and release of apoptogenic molecules from mitochondria, in particular cytochrome c. Having transited from the inter-membrane space to the cytoplasm, cytochrome c binds the apoptotic protease activating factor 1 (Apaf-1) which recruits caspase-9, a long pro-domain-containing member of the caspase family of cysteinyl aspartate-specific proteases. This forms the so-called apoptosome which processes downstream effector caspases such as caspase-3, culminating in cleavage of various structural and other proteins and, finally, cell death. The extrinsic pathway is activated when cytokines such as Fas ligand bind surface-expressed death receptors of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily (Ashkenazi and Dixit, 1998). Upon binding, receptors recruit intracellular adaptor proteins such as Fas-associated death domain protein (Fadd) which can activate caspase-8, followed by effector caspases (Wilson et al., 2009).

Apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) is a critical mediator of caspase-independent apoptosis. AIF is released from mitochondria whereupon it translocates to the nucleus and mediates large scale DNA fragmentation and nuclear condensation (Hangen et al., 2010). AIF release is triggered by various insults including excitotoxicity and AIF can be blocked in some models by Bcl-2 (Susin et al., 1999).

Bcl-2 Family

Control over MOMP and the downstream caspase-dependent and, possibly, AIF/caspase-independent cell death process, rests with the Bcl-2 family proteins. The family is characterized by the presence of one or more Bcl-2 homology (BH) domains and is divided into anti-apoptotic members, including Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL, and pro-apoptotic members. Within the pro-apoptotic family there are the multi-BH domain proteins, Bax and Bak, and the BH3-only subgroup. BH3-only proteins are the sentinels of cell stress. At least 10 members have been identified which share homology within the short BH3 domain but are otherwise structurally unrelated (Youle and Strasser, 2008). Some members are constitutively expressed in cells, requiring release from chaperones or post-translational modification to become active. Others are not normally present and require transcriptional upregulation. Two non-mutually exclusive mechanisms have been proposed for how BH3-only proteins promote MOMP. First, BH3-only proteins bind to anti-apoptotic members thereby neutralizing them. This displaces and allows activation of the multi-BH domain proteins Bax/Bak to trigger MOMP. A second mechanism is the direct activator model whereby BH3-only proteins directly activate Bax/Bak by binding and promoting their integration into mitochondria (Youle and Strasser, 2008; Chipuk et al., 2010). There is a hierarchy among BH3-only proteins with so-called “weak” members such as Bad having restricted affinity for only few anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins and unable to directly activate Bax/Bak, whereas potent members of the BH3-only family including Bim, Bid, and probably Puma can avidly bind all anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins and directly activate Bax/Bak (Youle and Strasser, 2008; Chipuk et al., 2010). Activation of pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins, in particular Bax and Bid, may also directly cause mitochondrial fragmentation that contributes to cell death (Youle and Karbowski, 2005).

Induction of Apoptosis-Associated Signaling Pathways after Acute Seizures

There is substantial evidence that prolonged or repeated seizures activate apoptosis-associated signaling in vivo (Engel and Henshall, 2009). Within a few hours of status epilepticus there is release of cytochrome c and other pro-apoptogenic molecules from mitochondria and an ensuing caspase cascade, and neuronal death can be interrupted using caspase inhibitors (Henshall et al., 2000a, 2001a,b; Viswanath et al., 2000; Narkilahti et al., 2003a; Li et al., 2006; Manno et al., 2007; Murphy et al., 2007).

Seizures also activate caspase-independent apoptosis pathways in the brain (Cheung et al., 2005; Takano et al., 2005; Engel et al., 2010a; Zhao et al., 2010). Here, calpains are thought to be critical. There are over 60 known calpain substrates and calpain is viewed as a critical coordinator of calcium-dependent signaling pathways underlying neuronal death (Vosler et al., 2008). Calpain inhibitors have proven to be effective neuroprotectants in models of status epilepticus (Araujo et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2008). Recently, calpain I (μ-calpain) was shown to be responsible for triggering AIF release during excitotoxicity (Cao et al., 2007). Thus, calpain and AIF may be particularly important for neuronal death in seizure models in which caspases are not activated (Fujikawa et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2010).

Bcl-2 family proteins in seizure-induced neuronal death

In vivo delivery of Bcl-XL or Bcl-2 in rodents can prevent neuronal death following excitotoxin administration in vivo (Lawrence et al., 1996; Ju et al., 2008). Also, mice lacking another anti-apoptotic member Bcl-w were found to be more vulnerable to seizures and to develop significantly more hippocampal damage after status epilepticus (Murphy et al., 2007). Thus, anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members protect against seizure-induced neuronal death in animal models.

Among the multi-BH domain proteins, Bax has been shown to accumulate at mitochondria after seizures (Henshall et al., 2002) but we await in vivo functional studies. Some in vitro data support a role for Bax in glutamate-induced neuronal death (Xiang et al., 1998), but other studies have reported bax-deficient neurons are equally vulnerable to excitotoxicity (Dargusch et al., 2001; Cheung et al., 2005). Bak does not appear to promote neuronal death in adult brain (Fannjiang et al., 2003) and there are no in vivo data on the third multi-BH domain member, Bok.

At least six members of the BH3-only subfamily have been studied in seizure models, including each of the potently pro-apoptotic BH3-only subgroup (Engel et al., 2011). Bid is rapidly cleaved to its more active form after seizures (Henshall et al., 2001b; Li et al., 2006; Engel et al., 2010a). Bim and Puma are both up-regulated after seizures, accumulate in the hippocampus and bind anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins (Shinoda et al., 2004; Engel et al., 2010c; Murphy et al., 2010). Among the less potent members, there is evidence for activation of Bad after seizures (Henshall et al., 2002; Noh et al., 2006) while two other BH3-only proteins examined, Noxa and Hrk, were not induced (Korhonen et al., 2003; Engel et al., 2010c).

Signaling pathways linking seizures to activation of BH3-only proteins

How are the various BH3-only proteins activated by seizures? For Bad, the trigger is thought to be dephosphorylation by the calcium-regulated phosphatase calcineurin (Henshall et al., 2002). Puma upregulation after seizures is largely p53-mediated. Indeed, pharmacologic inhibition of p53 prevents Puma induction after status epilepticus and Puma is not up-regulated after seizures in p53-deficient mice (Engel et al., 2010c). The trigger for p53 accumulation after seizures may be DNA damage, which is an early consequence of seizures in vivo (Henshall et al., 1999; Lan et al., 2000), but other stimuli including raised intracellular calcium could be responsible (Sedarous et al., 2003).

Bim has several transcriptional control mechanisms (Biswas et al., 2007; Puthalakath et al., 2007; Concannon et al., 2010). The FoxO1/3a transcription factors were the first to be linked to Bim regulation after status epilepticus (Shinoda et al., 2004), but more recent work has implicated c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK; Murphy et al., 2010). Indeed, in vivo injection of the JNK inhibitor SP600125 fully blocked Bim induction after status epilepticus in mice (Murphy et al., 2010). Activation of JNK itself may occur via stimulation of the KA receptor subunit GluR6 recruiting post-synaptic density protein 95 (PSD-95) and mixed lineage kinases, which activate JNK (Savinainen et al., 2001; Li et al., 2010a). This signaling scaffold also mediates the degradation of Bcl-2 after seizures (Zhang et al., 2011). JNK can also be activated downstream of TNF receptor 1 and endoplasmic reticulum stress (Yang et al., 2006), which are both early events following seizures (Shinoda et al., 2003; Murphy et al., 2010). Last, in vitro data show the adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) mediates Bim-induced neuronal death during excitotoxicity (Concannon et al., 2010), although this has not been explored in vivo.

Caspase-8 has been implicated in the mechanism of Bid activation after seizures on the basis that caspase-8 pseudosubstrate inhibitors reduced Bid cleavage (Henshall et al., 2001b; Li et al., 2006). Whether this is downstream of death receptors is unknown. Bid can also be activated by calpain (Mandic et al., 2002) and in some models cleavage of Bid may not be needed for mitochondrial translocation and neuronal apoptosis (Konig et al., 2007).

In vivo evidence that BH3-only proteins regulate neuronal death after seizures

Seizure-induced neuronal death has recently been studied in animals lacking each of the potently pro-apoptotic BH3-only proteins (Engel et al., 2011). Mice deficient in Puma are the most protected against seizure-induced neuronal death, with seizure-damage reduced by over 70% (Engel et al., 2010c). Puma-deficient mice were also protected when the severity of status epilepticus was increased to produce a stronger necrotic component (Engel et al., 2010b). Seizure-damage in the hippocampus of Bim-deficient mice was reduced by ∼45% in the same model (Murphy et al., 2010). In another study, however, bim−/− mice were not protected against intra-hippocampal KA-induced damage (Theofilas et al., 2009).

Seizure-induced hippocampal damage in Bid-deficient mice was not different to wild-type animals (Engel et al., 2010a). This was surprising because Bid-deficient mice were protected against stroke and traumatic brain injury, and bid−/− neurons are protected in vitro from glutamate excitotoxicity (Plesnila et al., 2001; Bermpohl et al., 2006). Of note, Puma-deficient mice are not protected against ischemic brain damage (Kuroki et al., 2009). This suggests there are differences in the contributions of BH3-only proteins to the patho-mechanisms of seizure versus ischemic damage as well as gaps between the relatedness of in vitro and in vivo models (Engel et al., 2011).

Bcl-2 family proteins in experimental epilepsy

Activation of apoptosis-associated signaling pathways also extends into the period of epileptogenesis and chronic recurrent seizures (i.e., epilepsy). Indeed, recent transcriptome profiling of rat brain found changes to apoptosis-associated genes were associated with all stages of epileptogenesis (Okamoto et al., 2010). We know little, however, about the role of Bcl-2 family proteins in epilepsy development. Puma-deficient mice were found to develop fewer epileptic seizures than wild-type animals after status epilepticus (Engel et al., 2010c), but there are no data on Puma levels in wild-type epileptic mice. Also, the influence of Puma deficiency on epileptogenesis is complicated by the neuroprotection afforded by its absence during the initial precipitating injury. Studies of brief evoked seizures, which model some aspects of epileptic seizures, show expression changes for a small number of Bcl-2 family proteins but functional studies are needed to determine whether they are active during the process of epileptogenesis or after epileptic seizures (Engel and Henshall, 2009).

Bcl-2 family proteins in human epilepsy

The expression of several members of the Bcl-2 family has been examined in human hippocampus and neocortex samples resected from patients with TLE (Engel and Henshall, 2009). Overall, the patterns favor an adapted, anti-apoptotic state which may function to limit seizure-induced neuronal death; Bcl-2, Bcl-w, and Bcl-XL are all expressed at higher levels in TLE samples than controls and levels of Bim are lower (Henshall et al., 2000b; Shinoda et al., 2004; Murphy et al., 2007; Engel and Henshall, 2009). Modest upregulation of Bax has been reported in some TLE studies while no changes have been reported for Bad or Bid (Engel and Henshall, 2009). Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, and Bax may also be aberrantly expressed in focal cortical dysplasia, another common cause of pharmacoresistant epilepsy (Chamberlain and Prayson, 2008).

Other apoptosis-associated signaling pathways during epileptogenesis and in chronic epilepsy

Several other apoptosis-associated genes have been examined during epileptogenesis and in chronic epilepsy. Immunohistochemistry and enzyme assays show caspase-3 is active several days and even a week after status epilepticus (Narkilahti et al., 2003b; Weise et al., 2005). Other caspases have similarly been found to be cleaved and/or active during epileptogenesis and in epileptic brain in experimental models (Engel and Henshall, 2009). Over-expression and cleavage of caspases-1, 2, 3, 6, 7, and 9 have also been identified in resected human TLE tissue (Engel and Henshall, 2009).

Non-cell death functions of apoptosis-associated signaling molecules

It is recognized that several proteins involved in apoptosis have non-cell death-related biological functions (Galluzzi et al., 2008; Lamb and Hardwick, 2010). Caspase-1, a member of the non-apoptotic subgroup, is the enzyme responsible for interleukin-1β (IL-1β) production. An inflammatory cytokine, IL-1β is pro-convulsive, prolonging seizures, while inhibitors of IL-1β and caspase-1 have potent anti-convulsive effects (Vezzani et al., 2010). A role for caspase activation has also been demonstrated in microglial activation (Burguillos et al., 2011). Apoptotic caspases, including caspases-2 and 6, have been found to localize to the dendritic fields of the hippocampus in the wake of experimental status epilepticus (Narkilahti and Pitkanen, 2005; Narkilahti et al., 2007). Similar patterns of staining for caspases-2, 3, and 9 have been found in hippocampal tissue from TLE patients. This likely reflects roles for caspases in dendritic pruning and synaptic plasticity (D'amelio et al., 2010). Most recently, Bad, Bax, and caspase-3 have been proposed in long-term depression of synaptic transmission (Li et al., 2010c; Jiao and Li, 2011). These non-cell death functions are almost certainly of relevance to epilepsy. Only a single study has explored the effects of caspase inhibition on epilepsy, however, and results were negative (Narkilahti et al., 2003a). Nevertheless, if caspases and certain Bcl-2 family proteins influence the post-insult remodeling process and exert direct influences on excitability then they represent therapeutic targets of interest long-after the initial precipitating injury.

Other apoptosis-associated molecules have neuromodulatory effects. TNFα is known to promote AMPA receptor function (Stellwagen and Malenka, 2006) and Bcl-w has been associated with GABA receptor signaling (Murphy et al., 2007). It is likely further non-cell death functions will emerge for apoptosis-associated signaling molecules.

Taken together, studies on apoptosis-associated signaling in epilepsy have revealed a widespread role which spans contributions to early as well as late cell death and a variety of non-cell death-regulatory functions including seizure thresholds and processes which may impact on epileptogenesis and the chronic epileptic state.

The intracellular pathways involved in long-term neuronal cell death after seizures are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Apoptosis-associated signaling pathways activated in neurons by seizures. Signaling pathways downstream of glutamate and Fas (death) receptors turn on BH3-only proteins of the Bcl-2 family, culminating in mitochondrial dysfunction and caspase-dependent and -independent cell death. The list is not complete and represents only some of the major pathways. Abbreviations: AIF, apoptosis-inducing factor; casp8, caspase-8; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; Fadd, Fas-associated death domain protein; FasR, Fas death receptor; JNK, Jun-terminal kinase; KA and NMDA, glutamate receptor subtypes; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Conclusion

The activation of cell signaling pathways in response to acute seizures has detrimental long-term effects. Upregulation of IEGs induced by pathological overactivity results in plastic changes that alter synaptic functions and neuronal connectivity in susceptible brain areas. IEGs induction after seizures has been described to lead to neuronal death in several regions of the brain, including the hippocampus and the limbic system. These structures are among the most epileptogenic areas of the brain, and are crucially involved in learning and memory processes. In addition, studies on apoptosis-associated signaling in epilepsy have revealed a widespread role which spans contributions to early as well as late cell death and a variety of non-cell death-regulatory functions including seizure thresholds and processes which may impact on epileptogenesis and the chronic epileptic state. Thus, the activation of cell signaling pathways after seizures (markedly depending on the neuromodulatory action of catecholaminergic and serotonergic systems) has dramatic long-term consequences such as neuronal loss, behavioral changes and irreversible loss of function. Understanding these mechanisms remains a crucial issue to unravel the origins of epileptic behaviors and ultimately identify a cure for chronic epileptic disorders.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Mark Dunleavy is a postdoctoral fellow supported by IRCSET (Ireland) under the Marie Curie-People cofunding action of the European Community. This work was funded by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (PRIN 2008 grant # 200894SYW2_002 to Yuri Bozzi), and the Italian Ministry of Health (grant RF-TAA-2008-1141282 to Yuri Bozzi) and Health Research Board (grant RP/2007/37 to David C. Henshall) and Science Foundation Ireland (grant 08/IN.1./B1875 to David C. Henshall).

References

- An J. J., Bae M. H., Cho S. R., Lee S. H., Choi S. H., Lee B. H., Shin H. S., Kim Y. N., Park K. W., Borrelli E., Baik J. H. (2004). Altered GABAergic neurotransmission in mice lacking dopamine D2 receptors. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 25, 732–741 10.1016/j.mcn.2003.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo I. M., Gil J. M., Carreira B. P., Mohapel P., Petersen A., Pinheiro P. S., Soulet D., Bahr B. A., Brundin P., Carvalho C. M. (2008). Calpain activation is involved in early caspase-independent neurodegeneration in the hippocampus following status epilepticus. J. Neurochem. 105, 666–676 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05181.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenazi A., Dixit V. M. (1998). Death receptors: signaling and modulation. Science 281, 1305–1308 10.1126/science.281.5381.1305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagdy G., Kecskemeti V., Riba P., Jakus R. (2007). Serotonin and epilepsy. J. Neurochem. 100, 857–873 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04277.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes N. M., Sharp T. (1999). A review of central 5-HT receptors and their function. Neuropharmacology 38, 1083–1152 10.1016/S0028-3908(99)00010-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barone P., Morelli M., Cicarelli G., Cozzolino A., Dejoanna G., Campanella G., Dichiara G. (1993). Expression of c-fos protein in the experimental epilepsy induced by pilocarpine. Synapse 14, 1–9 10.1002/syn.890140102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu J. M., Gainetdinov R. R., Caron M. G. (2007). The Akt-GSK-3 signaling cascade in the actions of dopamine. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 28, 166–172 10.1016/j.tips.2007.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu J. M., Sotnikova T. D., Marion S., Lefkowitz R. J., Gainetdinov R. R., Caron M. G. (2005). An Akt/beta-arrestin 2/PP2A signaling complex mediates dopaminergic neurotransmission and behavior. Cell 122, 261–273 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens A., Sibilia M., Wagner E. F. (1999). Amino-terminal phosphorylation of c-Jun regulates stress-induced apoptosis and cellular proliferation. Nat. Genet. 21, 326–329 10.1038/6854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y., Gaiarsa J. L., Tyzio R., Khazipov R. (2007). GABA: a pioneer transmitter that excites immature neurons and generates primitive oscillations. Physiol. Rev. 87, 1215–1284 10.1152/physrev.00017.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengzon J., Kokaia Z., Elmer E., Nanobashvili A., Kokaia M., Lindvall O. (1997). Apoptosis and proliferation of dentate gyrus neurons after single and intermittent limbic seizures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 10432–10437 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg A. T., Berkovic S. F., Brodie M. J., Buchhalter J., Cross J. H., Van Emde Boas W., Engel J., French J., Glauser T. A., Mathern G. W., Moshe S. L., Nordli D., Plouin P., Scheffer I. E. (2010). Revised terminology and concepts for organization of seizures and epilepsies: report of the ILAE Commission on Classification and Terminology, 2005–2009. Epilepsia 51, 676–685 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02522.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkeley J. L., Decker M. J., Levey A. I. (2002). The role of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor-mediated activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 in pilocarpine-induced seizures. J. Neurochem. 82, 192–201 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00977.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermpohl D., You Z., Korsmeyer S. J., Moskowitz M. A., Whalen M. J. (2006). Traumatic brain injury in mice deficient in Bid: effects on histopathology and functional outcome. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 26, 625–633 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas S. C., Shi Y., Sproul A., Greene L. A. (2007). Pro-apoptotic Bim induction in response to nerve growth factor deprivation requires simultaneous activation of three different death signaling pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 29368–29374 10.1074/jbc.M702634200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockaert J., Claeysen S., Becamel C., Dumuis A., Marin P. (2006). Neuronal 5-HT metabotropic receptors: fine-tuning of their structure, signaling, and roles in synaptic modulation. Cell Tissue Res. 326, 553–572 10.1007/s00441-006-0286-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozzi Y., Borrelli E. (2002). Dopamine D2 receptor signaling controls neuronal cell death induced by muscarinic and glutamatergic drugs. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 19, 263–271 10.1006/mcne.2001.1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozzi Y., Borrelli E. (2006). Dopamine in neurotoxicity and neuroprotection: what do D2 receptors have to do with it? Trends Neurosci. 29, 167–174 10.1016/j.tins.2006.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozzi Y., Vallone D., Borrelli E. (2000). Neuroprotective role of dopamine against hippocampal cell death. J. Neurosci. 20, 8643–8649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan T. J., Seeley W. W., Kilgard M., Schreiner C. E., Tecott L. H. (1997). Sound-induced seizures in serotonin 5-HT2c receptor mutant mice. Nat. Genet. 16, 387–390 10.1038/ng0897-387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burguillos M. A., Deierborg T., Kavanagh E., Persson A., Hajji N., Garcia-Quintanilla A., Cano J., Brundin P., Englund E., Venero J. L., Joseph B. (2011). Caspase signalling controls microglia activation and neurotoxicity. Nature 472, 319–324 10.1038/nature09788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callier S., Snapyan M., Le Crom S., Prou D., Vincent J. D., Vernier P. (2003). Evolution and cell biology of dopamine receptors in vertebrates. Biol. Cell 95, 489–502 10.1016/S0248-4900(03)00089-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao G., Xing J., Xiao X., Liou A. K., Gao Y., Yin X. M., Clark R. S., Graham S. H., Chen J. (2007). Critical role of calpain I in mitochondrial release of apoptosis-inducing factor in ischemic neuronal injury. J. Neurosci. 27, 9278–9293 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1329-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain W. A., Prayson R. A. (2008). Focal cortical dysplasia type II (malformations of cortical development) aberrantly expresses apoptotic proteins. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 16, 471–476 10.1097/PAI.0b013e31815d9ac7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung E. C., Melanson-Drapeau L., Cregan S. P., Vanderluit J. L., Ferguson K. L., Mcintosh W. C., Park D. S., Bennett S. A., Slack R. S. (2005). Apoptosis-inducing factor is a key factor in neuronal cell death propagated by BAX-dependent and BAX-independent mechanisms. J. Neurosci. 25, 1324–1334 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4904-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipuk J. E., Moldoveanu T., Llambi F., Parsons M. J., Green D. R. (2010). The BCL-2 family reunion. Mol. Cell 37, 299–310 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi D. W. (1988). Glutamate neurotoxicity and diseases of the nervous system. Neuron 1, 623–634 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90162-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford D. B., Olney J. W., Maniotis A., Collins R. C., Zorumski C. F. (1987). The functional anatomy and pathology of lithium-pilocarpine and high-dose pilocarpine seizures. Neuroscience 23, 953–968 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90171-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford J. J., Tighe O., Croke D. T., Kinsella A., Sibley D. R., Drago J., Waddington J. L. (1999). Conservation of behavioural topography to dopamine D1-like receptor agonists in mutant mice lacking the D1A receptor implicates a D1-like receptor not coupled to adenylyl cyclase. Neuroscience 93, 1483–1489 10.1016/S0306-4522(99)00297-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concannon C. G., Tuffy L. P., Weisova P., Bonner H. P., Davila D., Bonner C., Devocelle M. C., Strasser A., Ward M. W., Prehn J. H. (2010). AMP kinase-mediated activation of the BH3-only protein Bim couples energy depletion to stress-induced apoptosis. J. Cell Biol. 189, 83–94 10.1083/jcb.200909166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'amelio M., Cavallucci V., Cecconi F. (2010). Neuronal caspase-3 signaling: not only cell death. Cell Death Differ. 17, 1104–1114 10.1038/cdd.2009.180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dargusch R., Piasecki D., Tan S., Liu Y., Schubert D. (2001). The role of Bax in glutamate-induced nerve cell death. J. Neurochem. 76, 295–301 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00035.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNinno M. P., Schoenleber R., Perner R. J., Lijewski L., Asin K. E., Britton D. R., Mackenzie R., Kebabian J. W. (1991). Synthesis and dopaminergic activity of 3-substituted 1-(aminomethyl)-3,4-dihydro-5,6-dihydroxy-1H-2-benzopyrans: characterization of an auxiliary binding region in the D1 receptor. J. Med. Chem. 34, 2561–2569 10.1021/jm00112a034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel T., Caballero-Caballero A., Schindler C. K., Plesnila N., Strasser A., Prehn J. H., Henshall D. C. (2010a). BH3-only protein Bid is dispensable for seizure-induced neuronal death and the associated nuclear accumulation of apoptosis-inducing factor. J. Neurochem. 115, 92–101 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06909.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel T., Hatazaki S., Tanaka K., Prehn J. H., Henshall D. C. (2010b). Deletion of puma protects hippocampal neurons in a model of severe status epilepticus. Neuroscience 168, 443–450 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.03.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel T., Murphy B. M., Hatazaki S., Jimenez-Mateos E. M., Concannon C. G., Woods I., Prehn J. H., Henshall D. C. (2010c). Reduced hippocampal damage and epileptic seizures after status epilepticus in mice lacking proapoptotic Puma. FASEB J. 24, 853–861 10.1096/fj.09-145870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel T., Henshall D. C. (2009). Apoptosis, Bcl-2 family proteins and caspases: the ABCs of seizure-damage and epileptogenesis? Int. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. Pharmacol. 1, 97–115 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel T., Plesnila N., Prehn J. H., Henshall D. C. (2011). In vivo contributions of BH3-only proteins to neuronal death following seizures, ischemia, and traumatic brain injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 31, 1196–1210 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fannjiang Y., Kim C. H., Huganir R. L., Zou S., Lindsten T., Thompson C. B., Mito T., Traystman R. J., Larsen T., Griffin D. E., Mandir A. S., Dawson T. M., Dike S., Sappington A. L., Kerr D. A., Jonas E. A., Kaczmarek L. K., Hardwick J. M. (2003). BAK alters neuronal excitability and can switch from anti- to pro-death function during postnatal development. Dev. Cell 4, 575–585 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00091-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flavell S. W., Greenberg M. E. (2008). Signaling mechanisms linking neuronal activity to gene expression and plasticity of the nervous system. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 31, 563–590 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikawa D. G. (2005). Prolonged seizures and cellular injury: understanding the connection. Epilepsy Behav. 7(Suppl. 3), S3–S11 10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikawa D. G., Shinmei S. S., Zhao S., Aviles E. R., Jr. (2007). Caspase-dependent programmed cell death pathways are not activated in generalized seizure-induced neuronal death. Brain Res. 1135, 206–218 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galluzzi L., Joza N., Tasdemir E., Maiuri M. C., Hengartner M., Abrams J. M., Tavernarakis N., Penninger J., Madeo F., Kroemer G. (2008). No death without life: vital functions of apoptotic effectors. Cell Death Differ. 15, 1113–1123 10.1038/cdd.2008.28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangarossa G., Di Benedetto M., O'Sullivan G. J., Dunleavy M., Alcacer C., Bonito-Oliva A., Henshall D. C., Waddington J. L., Valjent E., Fisone G. (2011). Convulsant doses of a dopamine d1 receptor agonist result in erk-dependent increases in zif268 and arc/arg3.1 expression in mouse dentate gyrus. PLoS ONE 6, e19415. 10.1371/journal.pone.0019415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi F. S., Blandini F., Cantafora E., Biagioni F., Armentero M. T., Pasquali L., Orzi F., Murri L., Paparelli A., Fornai F. (2008). Activation of brain metabolism and fos during limbic seizures: the role of locus coeruleus. Neurobiol. Dis. 30, 388–399 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi F. S., Pizzanelli C., Biagioni F., Murri L., Fornai F. (2004). The role of norepinephrine in epilepsy: from the bench to the bedside. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 28, 507–524 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greengard P. (2001). The neurobiology of slow synaptic transmission. Science 294, 1024–1030 10.1126/science.294.5544.1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greengard P., Allen P. B., Nairn A. C. (1999). Beyond the dopamine receptor: the DARPP-32/protein phosphatase-1 cascade. Neuron 23, 435–447 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80798-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hangen E., Blomgren K., Benit P., Kroemer G., Modjtahedi N. (2010). Life with or without AIF. Trends Biochem. Sci. 35, 278–287 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannon J., Hoyer D. (2008). Molecular biology of 5-HT receptors. Behav. Brain. Res. 195, 198–213 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henshall D. C., Araki T., Schindler C. K., Lan J. Q., Tiekoter K. L., Taki W., Simon R. P. (2002). Activation of Bcl-2-associated death protein and counter-response of Akt within cell populations during seizure-induced neuronal death. J. Neurosci. 22, 8458–8465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henshall D. C., Bonislawski D. P., Skradski S. L., Araki T., Lan J. Q., Schindler C. K., Meller R., Simon R. P. (2001a). Formation of the Apaf-1/cytochrome c complex precedes activation of caspase-9 during seizure-induced neuronal death. Cell Death Differ. 8, 1169–1181 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henshall D. C., Bonislawski D. P., Skradski S. L., Lan J. Q., Meller R., Simon R. P. (2001b). Cleavage of Bid may amplify caspase-8-induced neuronal death following focally evoked limbic seizures. Neurobiol. Dis. 8, 568–580 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henshall D. C., Chen J., Simon R. P. (2000a). Involvement of caspase-3-like protease in the mechanism of cell death following focally evoked limbic seizures. J. Neurochem. 74, 1215–1223 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.741215.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henshall D. C., Clark R. S., Adelson P. D., Chen M., Watkins S. C., Simon R. P. (2000b). Alterations in bcl-2 and caspase gene family protein expression in human temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology 55, 250–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henshall D. C., Sinclair J., Simon R. P. (1999). Relationship between seizure-induced transcription of the DNA damage-inducible gene GADD45, DNA fragmentation, and neuronal death in focally evoked limbic epilepsy. J. Neurochem. 73, 1573–1583 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0731573.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdegen T., Claret F. X., Kallunki T., Martin-Villalba A., Winter C., Hunter T., Karin M. (1998). Lasting N-terminal phosphorylation of c-Jun and activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinases after neuronal injury. J. Neurosci. 18, 5124–5135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdegen T., Leah J. D. (1998). Inducible and constitutive transcription factors in the mammalian nervous system: control of gene expression by Jun, Fos and Krox, and CREB/ATF proteins. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 28, 370–490 10.1016/S0165-0173(98)00018-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera D. G., Robertson H. A. (1996). Activation of c-fos in the brain. Prog. Neurobiol. 50, 83–107 10.1016/S0301-0082(96)00021-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houser C. R., Huang C. S., Peng Z. (2008). Dynamic seizure-related changes in extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation in a mouse model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroscience 156, 222–237 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes P. E., Alexi T., Walton M., Williams C. E., Dragunow M., Clark R. G., Gluckman P. D. (1999). Activity and injury-dependent expression of inducible transcription factors, growth factors and apoptosis-related genes within the central nervous system. Prog. Neurobiol. 57, 421–450 10.1016/S0301-0082(98)00057-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inestrosa N. C., Arenas E. (2010). Emerging roles of Wnts in the adult nervous system. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 77–86 10.1038/nrn2755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao S., Li Z. (2011). Nonapoptotic function of BAD and BAX in long-term depression of synaptic transmission. Neuron 70, 758–772 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju K. L., Manley N. C., Sapolsky R. M. (2008). Anti-apoptotic therapy with a Tat fusion protein protects against excitotoxic insults in vitro and in vivo. Exp. Neurol. 210, 602–607 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasof G. M., Mandelzys A., Maika S. D., Hammer R. E., Curran T., Morgan J. I. (1995). Kainic acid-induced neuronal death is associated with DNA damage and a unique immediate-early gene response in c-fos-lacZ transgenic rats. J. Neurosci. 15, 4238–4249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaytor M. D., Orr H. T. (2002). The GSK3 beta signaling cascade and neurodegenerative disease. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 12, 275–278 10.1016/S0959-4388(02)00320-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. S., Hong K. S., Seong Y. S., Park J. B., Kuroda S., Kishi K., Kaibuchi K., Takai Y. (1994). Phosphorylation and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase by kainic acid-induced seizure in rat hippocampus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 202, 1163–1168 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokaia M. (2011). Seizure-induced neurogenesis in the adult brain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 33, 1133–1138 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07612.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo T., Sharp F. R., Honkaniemi J., Mikawa S., Epstein C. J., Chan P. H. (1997). DNA fragmentation and Prolonged expression of c-fos, c-jun, and hsp70 in kainic acid-induced neuronal cell death in transgenic mice overexpressing human CuZn-superoxide dismutase. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 17, 241–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konig H. G., Rehm M., Gudorf D., Krajewski S., Gross A., Ward M. W., Prehn J. H. (2007). Full length Bid is sufficient to induce apoptosis of cultured rat hippocampal neurons. BMC Cell Biol. 8, 7. 10.1186/1471-2121-8-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen L., Belluardo N., Mudo G., Lindholm D. (2003). Increase in Bcl-2 phosphorylation and reduced levels of BH3-only Bcl-2 family proteins in kainic acid-mediated neuronal death in the rat brain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 18, 1121–1134 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02826.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroki K., Virard I., Concannon C. G., Engel T., Woods I., Taki W., Plesnila N., Henshall D. C., Prehn J. H. (2009). Effects of transient focal cerebral ischemia in mice deficient in puma. Neurosci. Lett. 451, 237–240 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb H. M., Hardwick M. (2010). Noncanonical functions of BCL-2 proteins in the nervous system. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 687, 115–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan J., Henshall D. C., Simon R. P., Chen J. (2000). Formation of the base modification 8-hydroxyl-2’-deoxyguanosine and DNA fragmentation following seizures induced by systemic kainic acid in the rat. J. Neurochem. 74, 302–309 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0740302.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence M. S., Ho D. Y., Sun G. H., Steinberg G. K., Sapolsky R. M. (1996). Overexpression of Bcl-2 with herpes simplex virus vectors protects CNS neurons against neurological insults in vitro and in vivo. J. Neurosci. 16, 486–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Xu B., Wang W. W., Yu X. J., Zhu J., Yu H. M., Han D., Pei D. S., Zhang G. Y. (2010a). Coactivation of GABA receptors inhibits the JNK3 apoptotic pathway via disassembly of GluR6-PSD-95-MLK3 signaling module in KA-induced seizure. Epilepsia 51, 391–403 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02270.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Peng Z., Xiao B., Houser C. R. (2010b). Activation of ERK by spontaneous seizures in neural progenitors of the dentate gyrus in a mouse model of epilepsy. Exp. Neurol. 224, 133–145 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Jo J., Jia J. M., Lo S. C., Whitcomb D. J., Jiao S., Cho K., Sheng M. (2010c). Caspase-3 activation via mitochondria is required for long-term depression and AMPA receptor internalization. Cell 141, 859–871 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Lu C., Xia Z., Xiao B., Luo Y. (2006). Inhibition of caspase-8 attenuates neuronal death induced by limbic seizures in a cytochrome c-dependent and Smac/DIABLO-independent way. Brain Res. 1098, 204–211 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.04.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lothman E. W., Collins R. C. (1981). Kainic acid induced limbic seizures: metabolic, behavioral, electroencephalographic and neuropathological correlates. Brain Res. 218, 299–318 10.1016/0006-8993(81)91308-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lothman E. W., Collins R. C., Ferrendelli J. A. (1981). Kainic acid-induced limbic seizures: electrophysiologic studies. Neurology 31, 806–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandic A., Viktorsson K., Strandberg L., Heiden T., Hansson J., Linder S., Shoshan M. C. (2002). Calpain-mediated Bid cleavage and calpain-independent Bak modulation: two separate pathways in cisplatin-induced apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 3003–3013 10.1128/MCB.22.9.3003-3013.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manno I., Antonucci F., Caleo M., Bozzi Y. (2007). BoNT/E prevents seizure-induced activation of caspase 3 in the rat hippocampus. Neuroreport 18, 373–376 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32801b3cbb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara J. O., Huang Y. Z., Leonard A. S. (2006). Molecular signaling mechanisms underlying epileptogenesis. Sci. STKE 2006, re12. 10.1126/stke.3562006re12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meador-Woodruff J. H., Mansour A., Healy D. J., Kuehn R., Zhou Q. Y., Bunzow J. R., Akil H., Civelli O., Watson S. J., Jr. (1991). Comparison of the distributions of D1 and D2 dopamine receptor mRNAs in rat brain. Neuropsychopharmacology 5, 231–242 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meldrum B. (1991). Excitotoxicity and epileptic brain damage. Epilepsy Res. 10, 55–61 10.1016/0920-1211(91)90095-W [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mielke K., Brecht S., Dorst A., Herdegen T. (1999). Activity and expression of JNK1, p38 and ERK kinases, c-Jun N-terminal phosphorylation, and c-jun promoter binding in the adult rat brain following kainate-induced seizures. Neuroscience 91, 471–483 10.1016/S0306-4522(98)00667-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missale C., Nash S. R., Robinson S. W., Jaber M., Caron M. G. (1998). Dopamine receptors: from structure to function. Physiol. Rev. 78, 189–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan J. I., Cohen D. R., Hempstead J. L., Curran T. (1987). Mapping patterns of c-fos expression in the central nervous system after seizure. Science 237, 192–197 10.1126/science.3629250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan J. I., Curran T. (1989). Stimulus-transcription coupling in neurons: role of cellular immediate-early genes. Trends Neurosci. 12, 459–462 10.1016/0166-2236(89)90096-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan J. I., Curran T. (1991a). Proto-oncogene transcription factors and epilepsy. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 12, 343–349 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90594-I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan J. I., Curran T. (1991b). Stimulus-transcription coupling in the nervous system: involvement of the inducible proto-oncogenes fos and jun. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 421–451 10.1146/annurev.ne.14.030191.002225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy B., Dunleavy M., Shinoda S., Schindler C., Meller R., Bellver-Estelles C., Hatazaki S., Dicker P., Yamamoto A., Koegel I., Chu X., Wang W., Xiong Z., Prehn J., Simon R., Henshall D. (2007). Bcl-w protects hippocampus during experimental status epilepticus. Am. J. Pathol. 171, 1258–1268 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy B. M., Engel T., Paucard A., Hatazaki S., Mouri G., Tanaka K., Tuffy L. P., Jimenez-Mateos E. M., Woods I., Dunleavy M., Bonner H. P., Meller R., Simon R. P., Strasser A., Prehn J. H., Henshall D. C. (2010). Contrasting patterns of Bim induction and neuroprotection in Bim-deficient mice between hippocampus and neocortex after status epilepticus. Cell Death Differ. 17, 459–468 10.1038/cdd.2009.134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narkilahti S., Jutila L., Alafuzoff I., Karkola K., Paljarvi L., Immonen A., Vapalahti M., Mervaala E., Kalviainen R., Pitkanen A. (2007). Increased expression of caspase 2 in experimental and human temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuromol. Med. 9, 129–144 10.1007/BF02685887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narkilahti S., Nissinen J., Pitkanen A. (2003a). Administration of caspase 3 inhibitor during and after status epilepticus in rat: effect on neuronal damage and epileptogenesis. Neuropharmacology 44, 1068–1088 10.1016/S0028-3908(03)00115-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narkilahti S., Pirttila T. J., Lukasiuk K., Tuunanen J., Pitkanen A. (2003b). Expression and activation of caspase 3 following status epilepticus in the rat. Eur. J. Neurosci. 18, 1486–1496 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02874.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narkilahti S., Pitkanen A. (2005). Caspase 6 expression in the rat hippocampus during epileptogenesis and epilepsy. Neuroscience 131, 887–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi A., Snyder G. L., Greengard P. (1997). Bidirectional regulation of DARPP-32 phosphorylation by dopamine. J. Neurosci. 17, 8147–8155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh H. S., Kim Y. S., Kim Y. H., Han J. Y., Park C. H., Kang A. K., Shin H. S., Kang S. S., Cho G. J., Choi W. S. (2006). Ketogenic diet protects the hippocampus from kainic acid toxicity by inhibiting the dissociation of bad from 14-3-3. J. Neurosci. Res. 84, 1829–1836 10.1002/jnr.21057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto O. K., Janjoppi L., Bonone F. M., Pansani A. P., Da Silva A. V., Scorza F. A., Cavalheiro E. A. (2010). Whole transcriptome analysis of the hippocampus: toward a molecular portrait of epileptogenesis. BMC Genomics 11, 230. 10.1186/1471-2164-11-230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orrenius S., Zhivotovsky B., Nicotera P. (2003). Regulation of cell death: the calcium-apoptosis link. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 552–565 10.1038/nrm1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan G. J., Dunleavy M., Hakansson K., Clementi M., Kinsella A., Croke D. T., Drago J., Fienberg A. A., Greengard P., Sibley D. R., Fisone G., Henshall D. C., Waddington J. L. (2008). Dopamine D1 vs D5 receptor-dependent induction of seizures in relation to DARPP-32, ERK1/2 and GluR1-AMPA signalling. Neuropharmacology 54, 1051–1061 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan G. J., Kinsella A., Sibley D. R., Tighe O., Croke D. T., Waddington J. L. (2005). Ethological resolution of behavioural topography and D1-like versus D2-like agonist responses in congenic D5 dopamine receptor mutants: identification of D5:D2-like interactions. Synapse 55, 201–211 10.1002/syn.20107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei Q., Tordera R., Sprakes M., Sharp T. (2004). Glutamate receptor activation is involved in 5-HT2 agonist-induced Arc gene expression in the rat cortex. Neuropharmacology 46, 331–339 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2003.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez R. G., Lewis R. M. (1992). Regional distribution of DARPP-32 (dopamine- and adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate-regulated phosphoprotein of Mr = 32,000) mRNA in mouse brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 318, 304–315 10.1002/cne.903180307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkänen A., Schwartzkroin P., Moshé S. (2005). Models of Seizures and Epilepsy. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- Pitkanen A., Sutula T. P. (2002). Is epilepsy a progressive disorder? Prospects for new therapeutic approaches in temporal-lobe epilepsy. Lancet Neurol. 1, 173–181 10.1016/S1474-4422(02)00073-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plesnila N., Zinkel S., Le D. A., Amin-Hanjani S., Wu Y., Qiu J., Chiarugi A., Thomas S. S., Kohane D. S., Korsmeyer S. J., Moskowitz M. A. (2001). BID mediates neuronal cell death after oxygen/glucose deprivation and focal cerebral ischemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 15318–15323 10.1073/pnas.261323298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puthalakath H., O'reilly L. A., Gunn P., Lee L., Kelly P. N., Huntington N. D., Hughes P. D., Michalak E. M., Mckimm-Breschkin J., Motoyama N., Gotoh T., Akira S., Bouillet P., Strasser A. (2007). ER stress triggers apoptosis by activating BH3-only protein Bim. Cell 129, 1337–1349 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine R. J. (1972). Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation. II. Motor seizure. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neuroeurophysiol. 32, 281–294 10.1016/0013-4694(72)90177-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raivich G., Behrens A. (2006). Role of the AP-1 transcription factor c-Jun in developing, adult and injured brain. Prog. Neurobiol. 78, 347–363 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarnyai Z., Sibille E. L., Pavlides C., Fenster R. J., McEwen B. S., Toth M. (2000). Impaired hippocampal-dependent learning and functional abnormalities in the hippocampus in mice lacking serotonin(1A) receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 14731–14736 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savinainen A., Garcia E. P., Dorow D., Marshall J., Liu Y. F. (2001). Kainate receptor activation induces mixed lineage kinase-mediated cellular signaling cascades via post-synaptic density protein 95. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 11382–11386 10.1074/jbc.M100190200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauwecker P. E. (2000). Seizure-induced neuronal death is associated with induction of c-Jun N-terminal kinase and is dependent on genetic background. Brain Res. 884, 116–128 10.1016/S0006-8993(00)02888-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedarous M., Keramaris E., O'hare M., Melloni E., Slack R. S., Elce J. S., Greer P. A., Park D. S. (2003). Calpains mediate p53 activation and neuronal death evoked by DNA damage. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 26031–26038 10.1074/jbc.M302833200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng M., Greenberg M. E. (1990). The regulation and function of c-fos and other immediate early genes in the nervous system. Neuron 4, 477–485 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90060-S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]