Abstract

The primary products of de novo lipogenesis (DNL) are saturated fatty acids, which confer adverse cellular effects. Human adipocytes differentiated with no exogenous fat accumulated triacylglycerol (TG) in lipid droplets and differentiated normally. TG composition showed the products of DNL (saturated fatty acids from 12:0 to 18:0) together with unsaturated fatty acids (particularly 16:1n-7 and 18:1n-9) produced by elongation/desaturation. There was parallel upregulation of expression of genes involved in DNL and in fatty acid elongation and desaturation, suggesting coordinated control of expression. Enzyme products (desaturation ratios, elongation ratios, and total pathway flux) were also correlated with mRNA levels. We used 13C-labeled substrates to study the pathway of DNL. Glucose (5 mM or 17.5 mM in the medium) provided less than half the carbon used for DNL (42% and 47%, respectively). Glutamine (2 mM) provided 9-10%, depending upon glucose concentration. In contrast, glucose provided most (72%) of the carbon of TG-glycerol. Pathway analysis using mass isotopomer distribution analysis (MIDA) revealed that the pathway for conversion of glucose to palmitate is complex. DNL in human fat cells is tightly coupled with further modification of fatty acids to produce a range of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids consistent with normal maturation.

Keywords: desaturation, elongation, fatty acid synthesis, mass isotopomer

The pathway of de novo lipogenesis (DNL) was, until recently, believed to be virtually nonexistent in the human adipocyte (1–3). However, it is becoming increasingly clear that human adipocytes are capable of synthesis of fatty acids and triacylglycerols (TG) from nonlipid precursors. The expression of key enzymes of DNL, including acetyl-CoA carboxylase-A (ACACA) and fatty acid synthase (FAS), has been demonstrated in human adipose tissue (4, 5). Functionally, around 20% of palmitic acid in adipocyte TG arises from DNL, and although hepatic DNL could account for some of this (exported to the adipocyte in very low density lipoprotein TG), there is an excess that appears to have arisen in the adipose tissue (6). During hypercaloric, high-carbohydrate feeding, whole body DNL (measured by indirect calorimetry) increases considerably (7) and exceeds hepatic DNL (measured with tracers); the remainder may occur in adipose tissue (8).

The expression of lipogenic enzymes, which are greater in the adipose tissue of lean people (9, 10), specifically, those with smaller adipocytes (5), relates inversely to obesity. This finding is paralleled by accumulation of products of DNL, especially stearic acid (18:0) (5). This observation might suggest that small adipocytes use DNL to begin the process of lipid accumulation, with pathways for uptake of extracellular fatty acids becoming more important as the cells develop. Indeed, the lipogenic capacity of fetal human fat cells is high as the cells develop into mature adipocytes (11). There is further evidence from the study of human adipocyte differentiation in culture. Human preadipocytes differentiate and accumulate lipid droplets in the complete absence of an exogenous fat source (12). All of their accumulated fat should, therefore, be the product of DNL.

The primary product of DNL is palmitic acid (16:0), a saturated fatty acid. There is considerable evidence for adverse effects of excessive saturated fatty acid enrichment of cells (13–15). Therefore, adipocyte DNL might be expected to be associated with an adverse metabolic profile. It was surprising to discover that smaller cells that are associated with insulin sensitivity in vivo display more signs of DNL (i.e., increased expression of lipogenic enzymes and increased content of saturated fatty acids, especially myristic acid 14:0 and stearic acid) than do larger cells that are associated with insulin resistance in vivo (5). However, the palmitic acid content of adipose tissue TG does not relate to any of these measurements (5).

These observations suggested that the differentiating adipocyte might defend itself against adverse accumulation of saturated fatty acids produced from DNL by close linkage of DNL with further modification of fatty acids. There is evidence that hepatic DNL is regulated in parallel with elongation of fatty acids and their desaturation by the enzyme stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD, or delta-9 desaturase) (16, 17). We recently showed that differentiating human adipocytes protect themselves against cytotoxic effects of exogenous palmitate by upregulation of pathways for oleate synthesis (DNL, elongation and desaturation) (18). However, the coordinate regulation of these processes has not previously been shown in the differentiating adipocyte dependent solely on DNL-derived fatty acids for lipid accumulation.

Therefore, we investigated the induction of DNL during human adipocyte differentiation. Our hypothesis was that DNL could provide all the fatty acids necessary for normal differentiation and maturation if pathways for elongation and desaturation were induced in parallel. We also examined the pathways for DNL in the differentiating human adipocyte, a subject on which there is very little information. Although our starting hypothesis was that exogenous glucose would be the major precursor, we discovered that a large proportion of the fatty acids are synthesized from other sources. We explored that observation and details of the pathways involved.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Adipose tissue sample collection and preadipocyte culture

Subcutaneous adipose tissue biopsies were obtained by needle aspiration using a 12 gauge needle. Tissue donors consisted of 30 males and 39 females, with a median age of 41 years (ranging from 26 to 53 years), and with a median body mass index (BMI) of 26.3 kg/m2 (ranging from 16.7 to 40.1 kg/m2). The taking of human adipose tissue samples was approved by the Oxfordshire Clinical Research Ethics Committee, and all subjects gave written, informed consent.

Preadipocytes were isolated from subcutaneous adipose tissue and grown in medium consisting of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/nutrient mixture F-12 Ham's (v/v, 1:1), 10% fetal calf serum (Invitrogen), 1 µl/100 ml fibroblast growth factor and 100 units/ml penicillin as described previously (18). Fully confluent preadipocytes (day 0) were then differentiated for 14 days using a differentiation medium based on that of Hauner et al. (12), consisting of Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12 Ham (v/v, 1:1) containing 2 mM glutamine, 17 µM pantothenate, 100 nM human insulin, 1 nM triiodo-L-thyronine, 33 µM biotin, 10 µg/ml transferrin, 1 µM dexamethasone, and 1 ml/l gentamycin. 3-Isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (250 µM) and troglitazone (2 µM) were added for the first 3 days.

As discussed previously (18), the cells are differentiated without a source of exogenous fatty acids. Therefore all lipids present at day 14 were either present at the start of differentiation or arose through DNL.

Cellular protein quantitation

Total adipocyte protein per T25 flask was determined with the Bradford method (19) using Coomassie Blue G (Sigma-Aldrich, Gillingham, UK) made up according to the manufacturer's instructions. Bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich) was included as a standard.

Gas chromatography analysis of TG and phospholipid fatty acids

Fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) of adipocyte TGs and phospholipids (PL) were prepared and analyzed by gas chromatography (GC) as described previously (18). The fatty acid concentrations were calculated relative to the internal standard, and the results were expressed either as micrograms of fatty acid per 106 cells or as a mole percentage.

SCD and ELOVL flux calculations

Flux of fatty acids through the enzymes SCD and elongation of long chain fatty acids 6 (ELOVL6) was estimated as the sum of all the fatty acid products of the enzymes (18) and was expressed as micromoles of fatty acid over 14 days per 106 cells. For SCD, this was the sum of 16:1 n-7, 18:1 n-7, and 18:1 n-9, and for ELOVL6, the sum of 18:0 and 18:1 n-7.

Use of stable isotopes to trace carbon contribution of precursors to TG synthesis

Isotopically (13C)-labeled substrates (CK Gas, Cambridgeshire, UK) were added to the culture medium throughout differentiation to determine the precursors for DNL. In separate experiments, the following substrates were used: 1 mM [1-13C]acetate, D-[U-13C]glucose, 0.5 mM [U-13C]pyruvate, and 2 mM [U-13C]glutamine. For all except [1-13C]acetate, two glucose concentrations were studied, low (5 mM) and high (17.5 mM). Again, for all except [1-13C]acetate, these labeled substrates replaced the corresponding unlabeled substrate normally present in the medium.

After lipid extraction and separation of the TG fraction, FAMEs were analyzed using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) (18).

TG glycerol was extracted from the aqueous phase of the fatty acid derivitization, and tertiary-butyldimethylsilyl glycerol derivatives were produced as previously described (20). Glycerol was measured using a GC-MS equipped with a DB-Wax 30 m capillary column (i.d. 0.25 mm, film thickness 0.25 µm; Agilent). The sample (1 µl) was injected onto the column at an initial oven temperature of 110°C. The oven temperature was ramped at 10°C/min to 210°C and then at 20°C/min to 310°C. It was held at this temperature for 3 min for a total of 18 min. Injector and interface were 320°C, and gas flow was 1.1 ml/min. The sample was injected at split ratio of 50:1. The major peak corresponds to a fragmentation where a butyl group is removed and results in a molecule with a mass to charge ratio (m/z) of 377.3; thus, the peaks of m/z 377.3 and m/z 382.3 were measured using selected ion monitoring. Glycerol was corrected for natural enrichment using the isotope pattern obtained from Sheffield ChemPuter (http://winter.group.shef.ac.uk/chemputer/).

Analysis of isotopic tracer incorporation

GC-MS analysis produced a mass spectrum for each fatty acid and the relative abundance of each mass isotopomer. For each fatty acid, the native, unlabeled isotopomer is denoted M+0; e.g., methyl-palmitate M+0 has a mass of 270.3, whereas the isotopomer for [13C1]methyl-palmitate (M+1) has a mass of 271.3, etc. Relative abundance values were corrected for the natural abundance of 13C, which was obtained from measurements made in cells with no added labeled substrate. Data were analyzed in two ways: quantitative mass spectral analysis (QMSA) and mass isotopomer distribution analysis (MIDA).

QMSA was based on the method described by Tayek and Katz (21). In essence, we calculated the fraction of all carbon atoms in the product (e.g., palmitic acid) that were 13C. As the substrates [U13C]glucose and [U13C]glutamine were uniformly labeled, this represented the fraction of the product formed from the substrate in question. The same calculation was applied to the TG-glycerol moiety.

The evaluation of DNL through MIDA assumes that the fatty acids are constructed as polymers of the 2-carbon building block acetyl-CoA. If the 13C-enrichment of the acetyl-CoA pool is known, then the pattern of labeled molecules (mass isotopomers) produced can be predicted by the binomial theorem (22). Our data did not fit this simple model (see Results); therefore, more sophisticated modeling was attempted (see the supplementary data).

Gene expression measurements

RNA extracted from adipocytes was used to synthesize cDNA for real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis as previously described using 500 ng RNA (18). Target genes were as follows: ACACA, ACLY, ADIPOQ, CEBPA, DGAT2, ELOVL6, FABP4, FASN, G6PD, PCK1, PPARG, SCD, and SREBF1 (assay IDs Hs00167385_m1, Hs00153764_m1, Hs00605917_m1, Hs00269972_s1, Hs00261438, Hs00225412_m1, Hs00609791m1, Hs00188012_m1, Hs00166169_m1, Hs00159918_m1, Hs00234592_m1, Hs00748952_s1, and Hs00231674_m1, respectively). Normalized mRNA expression was calculated for each target gene using the Δ/ΔCT relative quantitation calculation as previously described (23, 24). In brief, the ΔCT transformation of all samples for each transcript was first calculated as ΔCT=E[minCT-sampleCT], where E equals the efficiency of the qRT-PCR reaction as calculated from the slope of a standard curve generated from a serial dilution of a pool of cDNA from all samples [E = (10[-1/slope])]. The Δ/ΔCT for each target gene was calculated as the target gene ΔCT divided by the ΔCT for the stable endogenous control PPIA (cyclophilin; assay ID Hs99999906_m1) (25). All measurements were made in triplicate.

Statistical analyses

Differences occurring over time were statistically analyzed using repeated-measures (ANOVA). Values were log-transformed where appropriate to achieve normality. Differences between conditions (e.g., low and high glucose concentrations) were assessed using a Student's paired t-test. Correlations were assessed using Spearman's rank correlation coefficient, rs. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS (version 15).

RESULTS

Fatty acid composition of differentiated cells reflects DNL

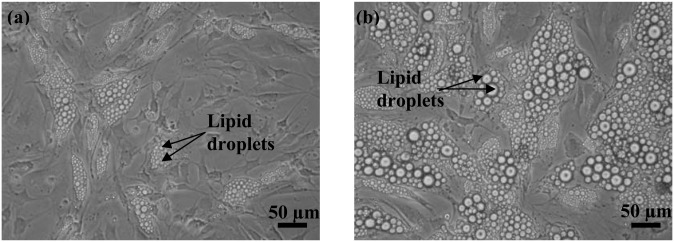

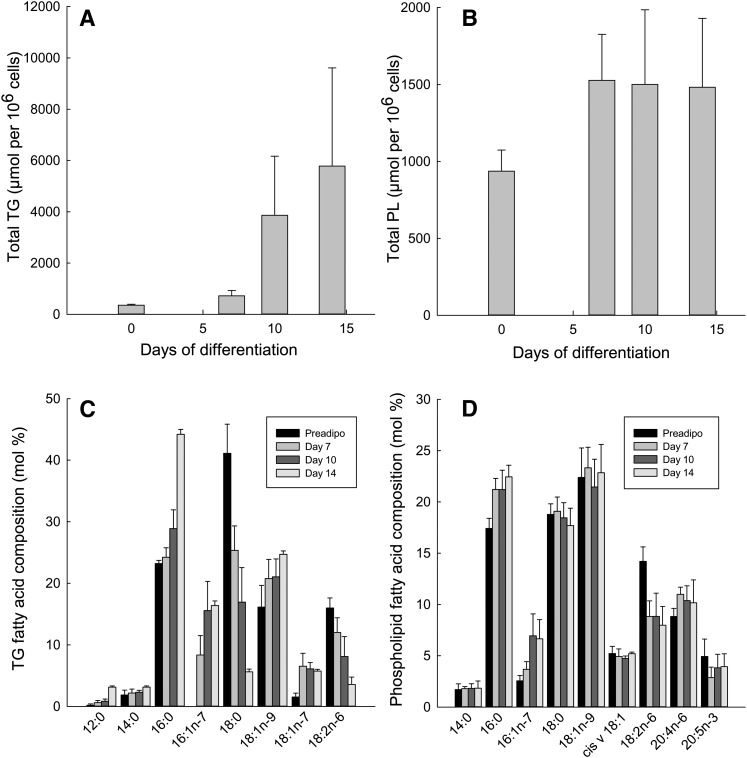

TG accumulated in cells during the differentiation process (Figs. 1 and 2A). The PL content tended to increase during the first week, and then it was constant (Fig. 2B). The protein content (expressed per 106 cells) rose slightly from preadipocyte to day 7, but then it was relatively constant (mean values for preadipocytes and for days 7, 10, and 14, respectively, were 198, 229, 238, and 225 µg (n = 3, P = 0.82, ANOVA).

Fig. 1.

Photomicrograph of adipocyte after 14 days of differentiation with no exogenous fat source. Human adipocytes differentiated (A) in the absence of fatty acids and (B) with a combination of different exogenous fatty acids (0.2 mM palmitate + 0.2 mM oleate).

Fig. 2.

TG and PL content of cells during differentiation and fatty acid composition. A: TG content during differentiation; n = 5, P = 0.06 for effect of time. B: PL content during differentiation; n = 5, P = 0.16. C: TG fatty acid composition, n = 5 for days 0-10, n = 74 at day 14, main effects of day (P = 0.04), fatty acid (P < 0.001), and day × fatty acid interaction (P < 0.001). D: PL fatty acid composition, n = 5, day × fatty acid interaction, P < 0.001. All statistics by repeated measures ANOVA.

The fatty acid composition of TG changed during differentiation. Stearic acid (18:0) predominated at early times, but it decreased, so that 16:0 (palmitic acid) became the major fatty acid by day 14 (Fig. 2C). The proportion of the essential fatty acid 18:2n-6 (linoleic acid) fell during this period. However, because the total TG content increased, the amount (µmol) of 18:2n-6 in TG changed much less, from 523 ± 83 µmol/106 cells in preadipocytes to 446 ± 55 µmol/106 cells at day 14 (P = 0.36, ANOVA). Therefore, the major fatty acids in TG at day 14 were those expected from the coordinate operation of the DNL and the elongation and desaturation pathways: 16:0, 16:1n-7 (palmitoleic acid), 18:0, 18:1n-9 (oleic acid), and 18:1n-7 (cis-vaccenic or asclepic acid, the elongation product of 16:1n-7). Smaller amounts of 12:0, 14:0 (Fig. 2C), and 14:1n-5 (the desaturation product of 14:0, not shown, mol% 0.20 ± 0.12) were also found.

The 16:0/18:2n-6 ratio was calculated as an index of DNL (dilution of essential fatty acids by those synthesized de novo) (16, 26). It rose from 1.5 ± 0.2 at day 0 to 39.9 ± 27.8 at day 14 (P = 0.04, ANOVA).

The PL fatty acid composition changed less (Fig. 2D). There was a progressive increase in the proportion of 16:0, whereas that of 18:2n-6 decreased. Again, the 16:0/18:2n-6 ratio rose from 1.3 ± 0.1 at day 0 to 3.7 ± 1.2 at day 14 (P = 0.01, ANOVA).

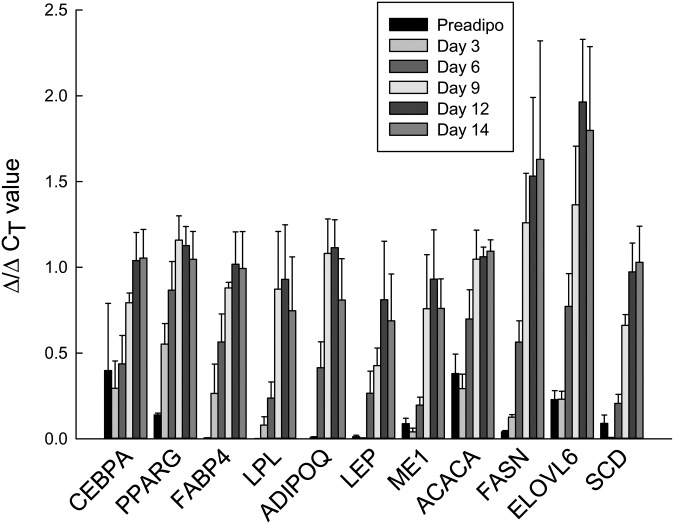

Expression of DNL-related genes is upregulated during differentiation

The changes in TG amount and composition were mirrored by the mRNA expression of the genes involved in DNL, elongation, and desaturation, as well as “classical” markers of differentiation, including CEBPA, PPARG, LPL, adiponectin, and leptin (Fig. 3). At day 14, the cells were expressing genes for fatty acid synthesis (ACACA, FASN, SCD, ELOVL6) as well as TG synthesis (e.g., DGAT2) (supplementary Table I). Genes involved in the supply of cytosolic acetyl-CoA for DNL (ACLY) and in the supply of NADPH (ME1, G6PD) were also expressed, as was the key glyceroneogenic gene PCK1 (PEPCK-cytosolic).

Fig. 3.

Time course for mRNA expression of genes involved in DNL during differentiation. For each gene, mRNA values are plotted for days 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 14 of differentiation (n = 4).

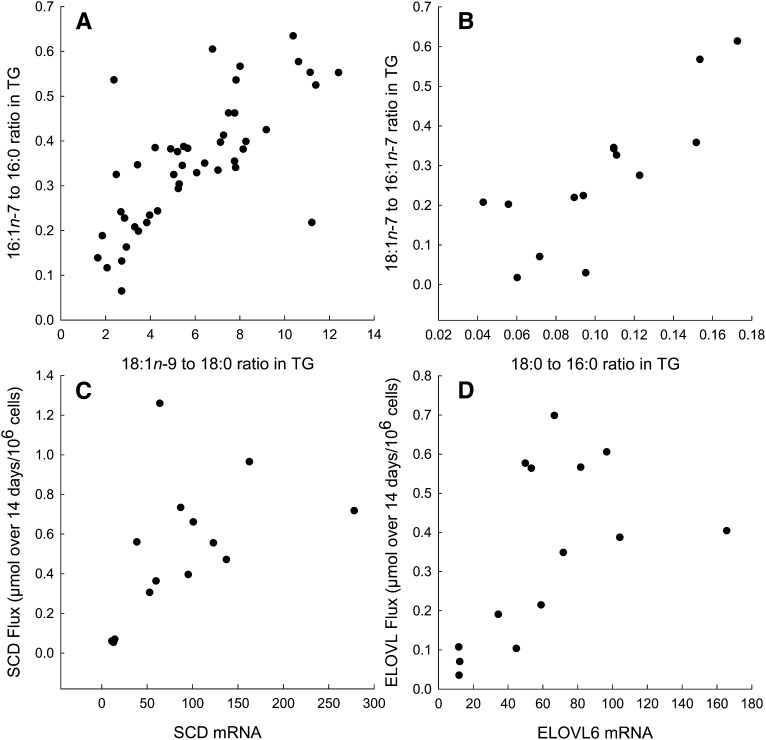

Fatty acid ratios reflecting the action of SCD, 16:1n-7/16:0 and 18:1n-9/18:0, were highly correlated across all cell cultures studied (Fig. 4A). Each of these ratios also correlated with the mRNA expression of SCD (rs = 0.37, P = 0.01; rs = 0.67, P < 0.001, respectively). Fatty acid ratios reflecting the action of ELOVL6, 18:0/16:0 and 18:1n-7/16:1n-7, were also correlated (Fig. 4B). However, ELOVL6 mRNA did not correlate with these fatty acid ratios, probably because one reaction removes reactants from another. We also calculated flux through each of these reactions, based on total accumulation of their products in TG over 14 days. In each case, flux correlated with mRNA expression of the respective enzyme (Fig. 4C, D).

Fig. 4.

Fatty acid ratios in TG and gene expression. A: Relationship between ratios reflecting desaturation; rs = 0.72, P < 0.001. B: Relationship between ratios reflecting elongation; rs = 0.84, P < 0.001. C: Relationship between flux through SCD over 14 days and SCD mRNA; rs = 0.68, P = 0.008. D: Relationship between flux through ELOVL6 over 14 days and ELOVL6 mRNA; rs = 0.67, P = 0.009.

The various mRNAs measured also tended to correlate highly with one another (Table 1), implying a strong element of coordinate control of gene expression in these pathways. Interestingly, one exception was SREBF1, in which mRNA did not correlate significantly with that of any other gene studied.

TABLE 1.

Relationships among mRNA levels for genes involved in differentiation, DNL, and fatty acid modification

| PPARG | SREBF1 | ACLY | G6PD | ACACA | FASN | SCDA | ELOVL6 | DGAT2 | ||

| CEBPA | rs | 0.915 | 0.027 | 0.880 | 0.598 | 0.767 | 0.903 | 0.916 | 0.643 | 0.922 |

| p | 0.000 | 0.872 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.086 | 0.000 | |

| n | 39 | 39 | 39 | 30 | 39 | 39 | 39 | 8 | 34 | |

| PPARG | rs | 0.049 | 0.854 | 0.606 | 0.709 | 0.860 | 0.908 | 0.825 | 0.895 | |

| p | 0.720 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| n | 55 | 55 | 37 | 55 | 53 | 55 | 15 | 43 | ||

| SREBF1 | rs | 0.083 | 0.099 | −0.029 | 0.114 | 0.079 | 0.214 | −0.059 | ||

| p | 0.546 | 0.561 | 0.835 | 0.415 | 0.565 | 0.443 | 0.705 | |||

| n | 55 | 37 | 55 | 53 | 55 | 15 | 43 | |||

| ACLY | rs | 0.656 | 0.858 | 0.922 | 0.918 | 0.721 | 0.894 | |||

| p | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | ||||

| n | 37 | 55 | 53 | 55 | 15 | 43 | ||||

| G6PD | rs | 0.658 | 0.600 | 0.498 | 0.032 | 0.622 | ||||

| p | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.909 | 0.000 | |||||

| n | 37 | 37 | 37 | 15 | 30 | |||||

| ACACA | rs | 0.815 | 0.772 | 0.586 | 0.846 | |||||

| p | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.022 | 0.000 | ||||||

| n | 53 | 55 | 15 | 43 | ||||||

| FASN | rs | 0.918 | 0.829 | 0.911 | ||||||

| p | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||||

| n | 53 | 15 | 41 | |||||||

| SCD | rs | 0.839 | 0.924 | |||||||

| p | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||||

| n | 15 | 43 | ||||||||

| ELOVL6 | rs | 0.905 | ||||||||

| p | 0.002 | |||||||||

| n | 8 |

All measurements were made after 14 days of differentiation.

De novo lipogenesis from acetate demonstrated using 13C-labeling

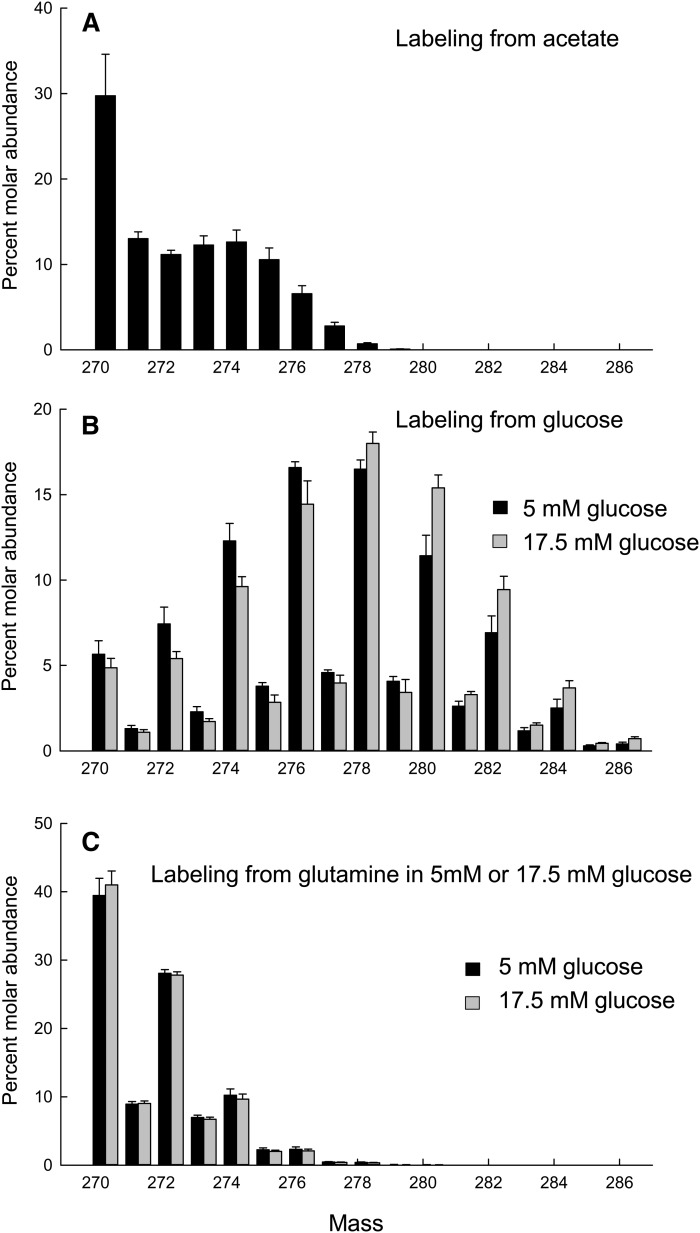

Next we investigated the pathway of DNL by differentiating cells in the presence of 1 mM [1-13C]acetate. The mass isotopomer spectrum of TG-palmitate from the differentiated cells at day 14 showed relatively consistent labeling from M+1 to M+5, with smaller amounts of higher labeling and none detectable above M+9 (Fig. 5A). (As noted in Experimental Procedures, all fatty acid mass abundance values were corrected for natural abundance by subtraction of results from cells with no added labeled substrate.) Similar patterns of labeling were seen in other TG-fatty acids, 14:0, 16:1n-7, 18:0, 18:1n-7 and 18:1n-9, confirming their origin from DNL. The molar abundance of native (unlabeled) TG-palmitate (M) was 29.8%, implying that the majority of the TG-palmitate molecules incorporated some labeled acetate. QMSA (see Experimental Procedures) showed that 16.6% of the palmitate carbon arose from acetate-13C in the medium (this would equate to 33.2% of palmitate carbon arising from acetate in the medium, since the acetate was labeled on one carbon) (Table 2). This implies considerable dilution of the labeled acetyl-CoA pool with acetyl-CoA coming from unlabeled substrates (e.g., glucose).

Fig. 5.

Mass isotopomer spectra for 16:0 in TG with different labeled substrates. A: Labeling from [1-13C]acetate. B: Labeling from [U-13C]glucose. C: Labeling from [U-13C]glutamine. B and C: Black, differentiation in 5 mM glucose; Gray, differentiation in 17.5 mM glucose.

TABLE 2.

Percentage of carbon formed from labeled substrate in medium

| TG-Palmitate |

TG-Glycerol |

|||

| Substrate | 5 mM Glucose | 17.5 mM Glucose | 5 mM Glucose | 17.5 mM Glucose |

| % carbon | % carbon | % carbon | % carbon | |

| 1 mM [1-13C]acetate | 16.6 ± 1.7a | ND | ND | ND |

| 0.5 mM [U-13C]pyruvate | 12.3 ± 2.3 | 12.3 ± 2.6 | 12.5 ± 1.1 | 13.9 ± 0.6 |

| [U-13C]glucose | 42.4 ± 2.0 | 47.0 ± 1.2b | 72.1 ± 4.6 | 72.6 ± 5.1 |

| 2 mM [U-13C]glutamine | 10.4 ± 0.7 | 9.2 ± 0.6 | 14.4 ± 0.5 | 13.4 ± 0.9 |

ND, not determined.

Because [1-13C]acetate was used, this is equivalent to 33.2% of TG-palmitate arising from medium acetate.

Significantly different from 5 mM [U-13C]glucose (P < 0.05).

De novo lipogenesis from glucose, pyruvate, and glutamine demonstrated using 13C-labeling

We differentiated cells in medium in which all the glucose was D-[U-13C]glucose. We used two different concentrations of glucose, 5 mM and 17.5 mM, and we expected that the higher concentration would particularly stimulate DNL from glucose. The amount of TG present at day 14 was not significantly different between the two conditions (5 mM, 0.53 ± 0.19 µmol TG/106 cells; 17.5 mM, 0.77 ± 0.31 µmol TG/106 cells; P = 0.12, paired t-test). TG mass isotopomer spectra were analyzed at day 14. The mass isotopomer spectrum in the presence of 17.5 mM glucose was very similar to that in the presence of 5 mM glucose (Fig. 5B), but it was shifted somewhat to the right. The mass isotopomer spectrum for 16:0 (Fig. 5B) showed that there was almost no completely labeled 16:0 (M+16). The greatest abundance was of the M+8 isotopomer. This was true at both glucose concentrations. Similar patterns were seen for other TG-fatty acids, 14:0, 16:1n-7, 18:0, 18:1n-7, and 18:1n-9. QMSA showed that 42% of the palmitate arose from 5 mM glucose in the medium and 47% of the palmitate arose from 17.5 mM glucose in the medium (Table 2). TG-glycerol mass isotopomers were analyzed (not shown). The concentration of glucose in the medium had no effect. [U-13C]glycerol (M+3) was around 3-fold more abundant than native (M), implying that the majority of TG-glycerol was formed from medium glucose (Table 2).

Because the data on DNL from glucose suggested another major substrate, we questioned whether the pyruvate that is a constituent of the medium might be that substrate. We replaced the pyruvate (0.5 mM) in the medium with 0.5 mM [U-13C]pyruvate throughout the differentiation period. For comparison with the labeled glucose experiments, we used low (5 mM) and high (17.5) mM (unlabeled) glucose concentrations. The resultant mass isotopomer spectrum for 16:0 in TG at 5 mM glucose (not shown) showed the greatest abundance for native 16:0 (27.3 mol%), with substantial labeling at M+2 (23.8 mol%), less labeling at M+1 and M+3, and progressively less labeling at higher masses. The implication is that the majority of 16:0 molecules present in TG had incorporated some carbon from pyruvate in the medium. Similar patterns were again seen for other TG-fatty acids. QMSA analysis showed that 12% of the palmitate-carbon arose from pyruvate in the medium (Table 2), with similar contributions to other fatty acids. Again, TG-glycerol mass isotopomers were analyzed and showed the greatest abundance for native glycerol. QMSA showed that 12.5% of TG-glycerol carbon was derived from pyruvate (Table 2). None of these values was significantly different in 17.5 mM compared with 5 mM glucose.

We then asked whether glutamine might play a role as a substrate for DNL, as it does in brown adipocytes (27). We replaced the glutamine (2 mM) in the medium with 2 mM [U-13C]glutamine throughout the differentiation period. Again, we used low (5 mM) and high (17.5) mM (unlabeled) glucose concentrations. At both 5 mM and 17.5 mM glucose, the mass isotopomer spectrum for 16:0 in TG showed the greatest abundance for native 16:0 (41%), with substantial labeling at M+2, less labeling at M+1 and M+3, and progressively less labeling at higher masses, with none detectable above M+11 (Fig. 5C). Mass spectra for 17.5 mM glucose were almost identical to those at 5 mM glucose (Fig. 5C). Similar patterns were again seen for other TG-fatty acids. QMSA showed that 10% of the carbons of palmitate arose from glutamine in the medium (Table 2), with similar contributions to other fatty acids. TG-glycerol mass isotopomers showed the greatest abundance for native glycerol. QMSA showed that 14% of TG-glycerol carbon was derived from glutamine (Table 2). As with pyruvate labeling, none of these values was significantly different in 17.5 mM compared with 5 mM glucose.

Pathways of de novo lipogenesis are complex

As described in Experimental Procedures, we modeled the incorporation of 13C into fatty acids from labeled substrates in the medium using MIDA. It was immediately clear that there were features of the data that could not be modeled with this simple approach, particularly the excess of unlabeled molecules (M) and the presence of significant amounts of “odd-numbered” labeled molecules (M+1, M+3, etc.). Our more sophisticated attempts at modeling these processes with binomial or trinomial expansions are described in the supplementary data.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that the differentiating human adipocyte is capable of synthesizing all the fatty acids it needs for maturation de novo from nonlipid precursors. The potential cellular toxicity of the saturated fatty acids that are the primary product of DNL is minimized by coordinate upregulation of elongation and desaturation pathways.

Our data were obtained in an in vitro setting. However, there is strong evidence that these pathways also operate in vivo (4, 5). The proportion of polyunsaturated fatty acids in human adipose tissue reflects the diet: correlation coefficients between dietary and adipose tissue fatty acids are typically around 0.6-0.7 for the essential fatty acids (e.g., linoleic acid, 18:2n-6). However, correlations are virtually absent for oleic acid (18:1n-9) and are weak for saturated fatty acids (28). This observation implies alternative routes of production of some fatty acids, and the present data show that DNL with elongation and desaturation is a potential route of oleic acid formation in the human adipocyte. Similar studies have been conducted recently on differentiation of the murine 3T3-L1 cell (29). Sensitive mass spectrometry approaches showed a range of fatty acids, similar to those found here, that included trace amounts of, for instance, odd-numbered fatty acids (9:0 to 17:0) and some of their desaturation products. We do not wish, however, to imply that DNL would be the only source of fatty acids available to the differentiating adipocyte. As Fig. 1A shows, a supply of exogenous fatty acids increases total TG storage. We described interactions between endogenous (DNL-derived) and exogenous fatty acids previously (18).

Further evidence for tight functional linkage between DNL and pathways of fatty acid modification came from our earlier experiments, in which we showed that DNL-derived fatty acids are preferentially channeled into elongation and desaturation compared with fatty acids delivered exogenously (18). In the present study, we noted strong correlations between the mRNA levels for most of the key enzymes in the DNL and fatty acid modification pathways, supporting the idea of coordinate control that would avoid the cellular toxicity of saturated fatty acids. The mRNA expression of the key transcription factor sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP1c) (gene SREBF1) was an exception. A lack of correlation between SREBP-1c and other DNL-associated genes has been observed previously in rat adipose tissue under various nutritional conditions (30). This seems surprising, as although the action of SREBP1c is mediated via posttranslational proteolysis and nuclear trafficking, it has been shown that, in many situations, the major site of control of its activity is at the level of gene expression, which is induced by both insulin and (in hepatocytes) liver X receptor (LXR) activation (31). Furthermore, in differentiating adipocytes, SREBP1c expression is closely linked with that of the CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP) transcription factors (32), although we found no relationship between their mRNA expression levels.

The use of 13C-labeled substrates enabled us to definitively show the origin of TG-fatty acids from nonlipid sources. When we labeled all the medium glucose, we found that more than half of the palmitate carbon remained unlabeled. Pyruvate was also present in the medium and might dilute the labeled pyruvate formed from glucose, although when we replaced the medium pyruvate with [U13C]pyruvate, we did not see sufficient labeling to explain the deficit. This finding implies that other substrates contribute carbon to DNL in the differentiating human adipocyte. In brown adipocytes, glutamine is a precursor for DNL (27). We showed that the same is true in human white adipocytes. Other amino acids might also contribute, and it is clear that a variety of substrates feed acetyl-CoA into the pathway of DNL in the human adipocyte.

In contrast, under the conditions that we studied, the majority of TG-glycerol was produced from glucose, presumably via glycolysis and glycerol 3-phosphate production. Labeling of TG-glycerol from pyruvate or glutamine was also observed. These would require operation of the glyceroneogenesis pathway (33). The relatively low labeling of TG-glycerol observed from these substrates is in keeping with the relatively low mRNA expression of PCK1, a key glyceroneogenic gene, under these conditions (supplementary Table I).

The pathways of fatty acid DNL were clearly not straightforward, as demonstrated by our attempts to model the experimental data with MIDA. In the presence of labeled acetate, there was a consistent and large peak of unlabeled palmitate that could not be fitted by the conventional MIDA model. The presence of this peak in other fatty acids implied that it is a genuine cellular phenomenon. We believe that the most likely explanation is that the lipogenic acetyl-CoA precursor pool is not in full equilibrium with the medium acetate pool, so that unlabeled acetyl-CoA coming from glycolysis, for instance, can feed preferentially into DNL. There is evidence for compartmentation of the intramitochondrial acetyl-CoA pool in liver (34). In the present situation, it could simply represent differences in acetate uptake and activation between cells in the same batch. It must also be remembered that we sampled TG that had been synthesized and accumulated over a 14-day period, and the metabolic pattern of the cells would undoubtedly have changed over that period. Therefore, pathways may have changed with time.

We consistently observed “odd-numbered” labeling from glucose that must represent formation of 13C1-acetyl-CoA, although glycolysis and pyruvate dehydrogenase action would have produced 13C2-acetyl-CoA from [U13C]glucose metabolism. This labeling could occur via pyruvate carboxylase, which would incorporate all three labeled carbons into oxaloacetate. When citrate exited the mitochondrion, two might be delivered to DNL as acetyl-CoA, leaving single-labeled oxaloacetate, which could potentially be converted to single-labeled pyruvate. Therefore, we extended MIDA with incorporation of a trinomial frequency distribution to allow for the presence of unlabeled, single-labeled, and double-labeled acetyl-CoA molecules in the precursor pool. With this model, there was still an excess of low degrees of labeling in the experimental data. We suggest various possible explanations. First, as noted above, we sampled TG that had accumulated over 14 days, and pathways might change in activity with stage of differentiation. Second, there might be separate origins of precursor pools of acetyl-CoA. That was particularly apparent in the case of labeling from [1-13C]acetate. With other labeled substrates, it is possible that acetyl-CoA was produced via different sources, for instance, glycolysis (likely the majority) and peroxisomal pathways. A further possibility would be that there is a recycling of DNL pathway intermediates with chain shortening, and then feeding back into the pathway. There is evidence for this during the differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells, in which odd-numbered fatty acids are produced (29). Introduction of labeled palmitate into that system showed production of labeled 15:0, confirming the presence of chain-shortening reactions (29). There is also considerable evidence for the activity of peroxisomal fatty acid oxidation in adipocytes that could be responsible for chain shortening (35, 36). Our data reveal the complexity of de novo lipid synthesis in maturing human preadipocytes. Further studies would be needed to address the molecular details of this process, incorporating the different stages of maturation, metabolism of the nonlipid precursors, the DNL pathway, and pathways of fatty acid oxidation in human adipocytes.

In summary, we demonstrated that human adipocytes are clearly capable of considerable rates of synthesis of fatty acids de novo. Potentially adverse effects of accumulation of saturated fatty acids are minimized by strong, coordinate control of the elongation and desaturation pathways, leading particularly to the synthesis of oleic acid (18:1n-9). Glucose is not the sole precursor of fatty acids under the conditions studied here; in fact, it contributes less than half of the carbon of the fatty acids produced from DNL. Other sources include glutamine and, presumably, other amino acids. In contrast, glucose is by far the major precursor of TG-glycerol. Pathways of fatty acid synthesis in the human adipocyte are complex, and further study of these processes may help in understanding the dysregulation of fat balance that characterizes obesity and its associated metabolic disturbances.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jane Cheeseman and Louise Dennis for taking the biopsies.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- ACACA

- acetyl-CoA carboxylase-A

- DNL

- de novo lipogenesis

- ELOVL

- elongation of long chain fatty acid

- FAME

- fatty acid methyl ester

- MIDA

- mass isotopomer distribution analysis

- PL

- phospholipid

- QMSA

- quantitative mass spectral analysis

- SCD

- stearoyl-CoA desaturase

- TG

- triacylglycerol

This work was supported by the Humane Research Trust, Stockport, Cheshire; by the Hepatic and Adipose Tissue and Functions in the Metabolic Syndrome (HEPADIP) project (Contract LSHM-CT-2005-018734), an Integrated Project under the European Union's Sixth Framework Programme; and by the Norwegian Research Council project 165026 (B.R.).

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains supplementary data in the form of one figure two, tables, and text.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shrago E., Spennetta T., Gordon E. 1969. Fatty acid synthesis in human adipose tissue. J. Biol. Chem. 244: 2761–2766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel M. S., Owen O. E., Goldman L. I., Hanson R. W. 1975. Fatty acid synthesis by human adipose tissue. Metabolism. 24: 161–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galton D. J. 1968. Lipogenesis in human adipose tissue. J. Lipid Res. 9: 19–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Letexier D., Pinteur C., Large V., Fréring V., Beylot M. 2003. Comparison of the expression and activity of the lipogenic pathway in human and rat adipose tissue. J. Lipid Res. 44: 2127–2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts R., Hodson L., Dennis A. L., Neville M. J., Humphreys S. M., Harnden K. E., Micklem K. J., Frayn K. N. 2009. Markers of de novo lipogenesis in adipose tissue: associations with small adipocytes and insulin sensitivity in humans. Diabetologia. 52: 882–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strawford A., Antelo F., Christiansen M., Hellerstein M. K. 2004. Adipose tissue triglyceride turnover, de novo lipogenesis, and cell proliferation in humans measured with 2H2O. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 286: E577–E588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pasquet P., Brigant L., Froment A., Koppert G. A., Bard D., de Garine I., Apfelbaum M. 1992. Massive overfeeding and energy balance in men: the Guru Walla model. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 56: 483–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aarsland A., Chinkes D., Wolfe R. R. 1997. Hepatic and whole-body fat synthesis in humans during carbohydrate overfeeding. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 65: 1774–1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diraison F., Dusserre E., Vidal H., Sothier M., Beylot M. 2002. Increased hepatic lipogenesis but decreased expression of lipogenic gene in adipose tissue in human obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 282: E46–E51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minehira K., Vega N., Vidal H., Acheson K., Tappy L. 2004. Effect of carbohydrate overfeeding on whole body macronutrient metabolism and expression of lipogenic enzymes in adipose tissue of lean and overweight humans. Int. J. Obes. 28: 1291–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunlop M., Court J. M. 1978. Lipogenesis in developing human adipose tissue. Early Hum. Dev. 2: 123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hauner H., Skurk T., Wabitsch M. 2001. Cultures of human adipose precursor cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 155: 239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Busch A. K., Gurisik E., Cordery D. V., Sudlow M., Denyer G. S., Laybutt D. R., Hughes W. E., Biden T. J. 2005. Increased fatty acid desaturation and enhanced expression of stearoyl coenzyme A desaturase protects pancreatic β-cells from lipoapoptosis. Diabetes. 54: 2917–2924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moffitt J. H., Fielding B. A., Evershed R., Berstan R., Currie J. M., Clark A. 2005. Adverse physicochemical properties of tripalmitin in beta cells lead to morphological changes and lipotoxicity in vitro. Diabetologia. 48: 1819–1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borradaile N. M., Han X., Harp J. D., Gale S. E., Ory D. S., Schaffer J. E. 2006. Disruption of endoplasmic reticulum structure and integrity in lipotoxic cell death. J. Lipid Res. 47: 2726–2737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chong M. F., Hodson L., Bickerton A. S., Roberts R., Neville M., Karpe F., Frayn K. N., Fielding B. A. 2008. Parallel activation of de novo lipogenesis and stearoyl-CoA desaturase activity after 3 d of high-carbohydrate feeding. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 87: 817–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oosterveer M. H., van Dijk T. H., Tietge U. J., Boer T., Havinga R., Stellaard F., Groen A. K., Kuipers F., Reijngoud D-J. 2009. High fat feeding induces hepatic fatty acid elongation in mice. PLoS ONE. 4: e6066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collins J. M., Neville M. J., Hoppa M. B., Frayn K. N. 2010. De novo lipogenesis and stearoyl-CoA desaturase are coordinately regulated in the human adipocyte and protect against palmitate-induced cell injury. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 6044–6052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradford M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72: 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adiels M., Larsson T., Sutton P., Taskinen M-R., Borén J., Fielding B. A. 2010. Optimization of N-methyl-N-[tert-butyldimethylsilyl]trifluoroacetamide as a derivatization agent for determining isotopic enrichment of glycerol in very-low density lipoproteins. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 24: 586–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tayek J. A., Katz J. 1996. Glucose production, recycling, and gluconeogenesis in normals and diabetics: a mass isotopomer [U-13C]glucose study. Am. J. Physiol. 270: E709–E717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hellerstein M. K., Christiansen M., Kaempfer S., Kletke S., Wu K., Reid J. S., Mulligan K., Hellerstein N. S., Shackleton C. H. L. 1991. Measurement of de novo lipogenesis in humans using stable isotopes. J. Clin. Invest. 87: 1841–1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Risérus U., Tan G. D., Fielding B. A., Neville M. J., Currie J., Savage D. B., Chatterjee V. K., Frayn K. N., O'Rahilly S., Karpe F. 2005. Rosiglitazone increases indexes of stearoyl-CoA desaturase activity in humans: link to insulin sensitization and the role of dominant-negative mutation in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma. Diabetes. 54: 1379–1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfaffl M. W. 2001. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29: e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neville M. J., Collins J. M., Gloyn A. L., McCarthy M. I., Karpe F. 2011. Comprehensive human adipose tissue mRNA and microRNA endogenous control selection for quantitative real-time-PCR normalization. Obesity (Silver Spring). 19: 888–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hudgins L. C., Hellerstein M., Seidman C., Neese R., Diakun J., Hirsch J. 1996. Human fatty acid synthesis is stimulated by a eucaloric low fat, high carbohydrate diet. J. Clin. Invest. 97: 2081–2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoo H., Stephanopoulos G., Kelleher J. K. 2004. Quantifying carbon sources for de novo lipogenesis in wild-type and IRS-1 knockout brown adipocytes. J. Lipid Res. 45: 1324–1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hodson L., Skeaff C. M., Fielding B. A. 2008. Fatty acid composition of adipose tissue and blood in humans and its use as a biomarker of dietary intake. Prog. Lipid Res. 47: 348–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts L. D., Virtue S., Vidal-Puig A., Nicholls A. W., Griffin J. L. 2009. Metabolic phenotyping of a model of adipocyte differentiation. Physiol. Genomics. 39: 109–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bertile F., Raclot T. 2004. mRNA levels of SREBP-1c do not coincide with the changes in adipose lipogenic gene expression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 325: 827–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hegarty B. D., Bobard A., Hainault I., Ferre P., Bossard P., Foufelle F. 2005. Distinct roles of insulin and liver X receptor in the induction and cleavage of sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102: 791–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Payne V. A., Au W. S., Lowe C. E., Rahman S. M., Friedman J. E., O'Rahilly S., Rochford J. J. 2009. C/EBP transcription factors regulate SREBP1c gene expression during adipogenesis. Biochem. J. 425: 215–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reshef L., Olswang Y., Cassuto H., Blum B., Croniger C. M., Kalhan S. C., Tilghman S. M., Hanson R. W. 2003. Glyceroneogenesis and the triglyceride/fatty acid cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 30413–30416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.von Glutz G., Walter P. 1975. Compartmentation of acetyl-coA in rat-liver mitochondria. Eur. J. Biochem. 60: 147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hajra A. K., Larkins L. K., Das A. K., Hemati N., Erickson R. L., MacDougald O. A. 2000. Induction of the peroxisomal glycerolipid-synthesizing enzymes during differentiation of 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Role in triacylglycerol synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 9441–9446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Su X., Han X., Yang J., Mancuso D. J., Chen J., Bickel P. E., Gross R. W. 2004. Sequential ordered fatty acid α oxidation and Δ9 desaturation are major determinants of lipid storage and utilization in differentiating adipocytes. Biochemistry. 43: 5033–5044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.