Abstract

Referral to a nephrologist before initiation of chronic dialysis occurs less frequently for blacks than whites, but the reasons for this disparity are incompletely understood. Here, we examined the contribution of racial composition by zip code on access and quality of nephrology care before initiation of renal replacement therapy (RRT). We retrospectively studied a cohort study of 92,000 white and black adults who initiated RRT in the United States between June 1, 2005, and October 5, 2006. The percentage of patients without pre-ESRD nephrology care ranged from 30% among those who lived in zip codes with <5% black residents to 41% among those who lived in areas with >50% black residents. In adjusted analyses, as the percentage of blacks in residential areas increased, the likelihood of not receiving pre-ESRD nephrology care increased. Among patients who received nephrology care, the quality of care (timing of care and proportion of patients who received a pre-emptive renal transplant, who initiated therapy with peritoneal dialysis, or who had a permanent hemodialysis access) did not differ by the racial composition of their residential area. In conclusion, racial composition of residential areas associates with access to nephrology care but not with quality of the nephrology care received.

Clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease emphasize the importance of timely referral to a nephrologist for patients expected to require renal replacement therapy.1–3 Nevertheless, approximately 33% of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients in the United States do not see a nephrologist before initiation of chronic dialysis.4,5 Lack of timely access to nephrology care is associated with several adverse outcomes after initiation of dialysis including higher mortality rates,6–9 higher rates of hospitalization,10 lower rates of renal transplantation,11,12 delayed creation of arteriovenous fistulae,13 lower rates of achievement of dialysis treatment targets,14,15 and a lower likelihood of receiving home-based dialysis therapies such as peritoneal dialysis and home hemodialysis.3,16–18

In the United States, black dialysis patients are less likely than white patients to have received nephrology care before onset of ESRD.9,19–21 They are also less likely to receive a pre-emptive kidney transplant,22,23 select peritoneal dialysis over hemodialysis,24 and have a vascular access in place at onset of hemodialysis.25,26 Several factors may contribute to these disparities including differences in insurance status, level of education, physician knowledge or biases, and patient preferences.9,27–29 In addition, geographic factors such as proximity to dialysis facilities and degree of urbanization also affect access to nephrology care.30–33

A substantial proportion of black patients are also more likely to live in areas where most other residents are black. A recent study demonstrated that both black and white dialysis patients living in predominantly black zip codes were less likely to receive a kidney transplant than patients living in other areas.34 Although levels of income, wealth and education tended to be lower among residents of predominantly black zip codes, lower transplant rates among dialysis patients living in these areas were not completely explained by these measures. Patients who live in predominantly black zip codes may face unique barriers to care that are not explained by measured socioeconomic characteristics of those zip codes. We therefore hypothesized that dialysis patients living in zip codes with a greater proportion of black residents would be less likely to have received pre-ESRD care and less likely to have received high-quality nephrology care than patients living in other zip codes. We also hypothesized that these relationships would not be completely explained by differences in zip code socioeconomic status or patient race.

Results

Patients

We identified 129,106 patients who initiated renal replacement therapy between June 1, 2005, and October 5, 2006. We excluded 4111 patients either because their zip code at initiation was not recorded in the USRDS database or because the zip code recorded could not be matched to a zip code tabulation area in the 2000 U.S. Census. We excluded a further 12,735 patients who were missing information on the timing of nephrology referral, 19,549 patients who were neither black nor white, and 711 patients who were younger than 18 or older than 100. The analytic sample consisted of the remaining 92,000 patients. Baseline characteristics of the excluded patients were similar to those in the analytic sample.

Descriptive Statistics

A total of 30,455 black and 61,545 white patients were included in this study. Overall, 63.4% of white patients lived in zip codes with <5% black residents and 2.2% lived in zip codes with >50% black residents (Table 1). Conversely, 41.5% of black patients lived in zip codes with >50% black residents and only 6.9% lived in zip codes with <5% black residents. Patients living in zip codes with a higher percentage of black residents were on average younger and were more likely to be women, to have hypertension, and to have either Medicaid or no medical coverage (Table 1). They were less likely to be employed, to have cardiac or peripheral vascular disease, and to have either Medicare or employee group coverage (Table 1). Zip codes with a higher percentage of black residents had, on average, a lower median per capita income, a lower proportion of residents employed in professional or managerial positions, a lower percentage of owner-occupied housing units, a lower percentage of adults with a high school diploma or college degree, and a higher percentage of residents living below poverty level (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patient-level baseline characteristics by zip code category

| Characteristics | Proportion of Black Residents in Zip Code |

P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <5% | 5 to 14.9% | 15 to 24.9% | 25 to 49.9% | >50% | ||

| Total number of patients (n) | 41,126 | 17,257 | 8170 | 11,443 | 14,004 | |

| Number of white patients | 39,013 | 12,839 | 4501 | 3814 | 1378 | |

| Number of black patients | 2113 | 4418 | 3669 | 7629 | 12,626 | |

| Black patients (%) | 5.14 | 25.60 | 44.91 | 66.67 | 90.16 | <0.001 |

| Mean age (years) | 66.47 | 63.98 | 61.88 | 60.87 | 59.61 | <0.001 |

| Gender (% women) | 41.70 | 43.41 | 45.91 | 48.03 | 50.64 | <0.001 |

| Employed at form completion (%) | 12.01 | 12.56 | 12.68 | 10.78 | 10.98 | <0.001 |

| Health insurance at onset of ESRD (%) | ||||||

| Medicare | 61.77 | 56.57 | 53.17 | 51.73 | 46.5 | <0.001 |

| Medicaid | 16.18 | 19.85 | 23.88 | 29.67 | 32.97 | <0.001 |

| Veterans Affairs | 1.82 | 1.94 | 1.76 | 1.71 | 1.54 | 0.11 |

| Employee group coverage | 31.19 | 31.4 | 31.46 | 27.27 | 26.58 | <0.001 |

| Other | 31.93 | 24.74 | 19.83 | 15.72 | 12 | <0.001 |

| No coverage | 3.75 | 6.16 | 7.81 | 9.8 | 11.52 | <0.001 |

| Comorbid conditions (%) | ||||||

| Cardiac disease | 54.24 | 50.69 | 48.29 | 44.83 | 41.77 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 48.19 | 49.3 | 51.02 | 51.32 | 49.91 | <0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 17.78 | 15.17 | 15.34 | 13.64 | 10.08 | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 10.6 | 10.22 | 10.8 | 10.22 | 10.23 | 0.36 |

| Hypertension | 81.77 | 83.47 | 84.92 | 86.54 | 86.92 | <0.001 |

| Timing of nephrology referral (%) | ||||||

| Not referred before RRT | 29.47 | 31.95 | 33.57 | 36.49 | 40.66 | |

| <6 months before RRT | 12.83 | 12.3 | 11.24 | 9.81 | 11.34 | |

| 6 to 12 months before RRT | 27.96 | 28.01 | 27.93 | 27.96 | 27.01 | |

| >12 months before RRT | 29.74 | 27.75 | 27.26 | 25.74 | 20.99 | <0.001 |

The first three lines provide number of patients in each zip code and race category for reference. P values for categorical variables were calculated using χ2 tests and those for continuous variables were calculated using the Kruskal-Wallis test. No characteristic had missing values.

Table 2.

Zip code–level socioeconomic characteristics by zip code category

| Characteristic | Proportion of Black Residents in Zip Code |

P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <5% | 5 to 14.9% | 15 to 24.9% | 25 to 49.9% | >50% | ||

| Total number of zip codes (n) | 11,620 | 2842 | 1186 | 1491 | 1077 | |

| Median per capita income ($U.S.) | 21,400 | 21,323 | 18,757 | 16,528 | 14,032 | <0.0001 |

| People below poverty line (%) | 9.79 | 11.42 | 13.95 | 18.11 | 25.45 | <0.0001 |

| People employed in professional/managerial positions (%) | 31.16 | 32.02 | 28.96 | 26.05 | 23.71 | <0.0001 |

| Housing units occupied by owner (%) | 76.72 | 68.37 | 66.63 | 65.96 | 59.40 | <0.0001 |

| People aged >25 years with high school diploma (%) | 31.32 | 26.98 | 28.02 | 28.77 | 27.99 | <0.0001 |

| People aged >25 years with college degree (%) | 12.57 | 13.13 | 10.94 | 8.93 | 7.45 | <0.0001 |

| Zip codes in metropolitan areas (%) | 56.32 | 77.02 | 69.48 | 55.80 | 66.57 | <0.0001 |

There were 4 zip codes missing data on percentage of owner-occupied housing and 11 zip codes missing data on type of employment. Total number of zip codes was 18,216.

Zip Code Racial Composition and Receipt of Pre-ESRD Nephrology Care

Overall, 29.5% of patients living in zip codes with <5% black residents did not receive nephrology care compared with 40.7% of those living in zip codes with >50% black residents (P < 0.0001). Zip code racial composition was associated with receipt of nephrology care even after adjustment for patient race and other patient- and zip code–level socioeconomic characteristics. Compared with the referent category of patients living in zip codes with <5% black residents, the unadjusted odds ratios for not receiving nephrology care before renal replacement therapy for those living in zip codes with 5 to 14.9%, 15 to 24.9%, 25 to 50%, and >50% black residents were respectively 1.11 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.07 to 1.16), 1.21 (CI, 1.14 to 1.29), 1.36 (CI, 1.29 to 1.44), and 1.61 (CI, 1.52 to 1.70). This association persisted after adjustment for patient- and zip code–level characteristics: 1.05 (95% CI, 1.02 to 1.10), 1.08 (CI, 1.01 to 1.16), 1.12 (CI, 1.05 to 1.19), and 1.21 (CI, 1.12 to 1.30), respectively (Table 3). Odds ratios for the association of zip code racial composition with receipt of predialysis nephrology care were progressively attenuated by sequential adjustment for patient characteristics, individual-level socioeconomic characteristics, and area-level socioeconomic characteristics. These results suggest that the aforementioned factors contribute to, but do not completely explain, the association of zip code racial composition with not receiving pre-ESRD nephrology care (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of sequentially adding patient and area characteristics on zip code racial composition odds ratios for receipt of nephrology care

| Model | Percentage of Black Residents in Zip Code |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 to 14.9% | 15 to 24.9% | 25 to 50% | >50% | |

| 1 | 1.11 (1.07 to 1.16) | 1.21 (1.14 to 1.29) | 1.36 (1.29 to 1.44) | 1.61 (1.52 to 1.7) |

| 2 | 1.08 (1.03 to 1.13) | 1.14 (1.07 to 1.12) | 1.24 (1.17 to 1.31) | 1.41 (1.32 to 1.50) |

| 3 | 1.08 (1.03 to 1.13) | 1.15 (1.08 to 1.22) | 1.26 (1.18 to 1.34) | 1.42 (1.33 to 1.52) |

| 4 | 1.06 (1.02 to 1.11) | 1.12 (1.05 to 1.2) | 1.19 (1.12 to 1.27) | 1.34 (1.25 to 1.43) |

| 5 | 1.05 (1.00 to 1.10) | 1.08 (1.01 to 1.16) | 1.12 (1.05 to 1.19) | 1.21 (1.12 to 1.3) |

| Final model (5) stratified by race | ||||

| White patients | 1.07 (1.01 to 1.12) | 1.12 (1.03 to 1.21) | 1.14 (1.04 to 1.23) | 1.26 (1.11 to 1.43) |

| Black patients | 1.03 (0.92 to 1.16) | 1.03 (0.91 to 1.17) | 1.11 (0.98 to 1.24) | 1.19 (1.05 to 1.34) |

Model 1 included only zip code racial composition. Model 2 added patient race to model 1 and model 3 added patient demographic and clinical variables to model 2. In model 4, patient-level socioeconomic status variables were added to the previous model. In model 5, zip code–level socioeconomic variables were added to model 4. The final two rows show the fully adjusted model (5) stratified by patient race. P values for all cells except for the first three columns for the black patients model were significant at the 0.05 level.

Associations of Patient Race and Area Poverty with Receipt of Pre-ESRD Nephrology Care

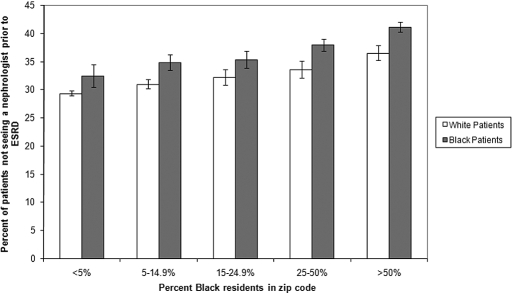

From zip codes with the lowest to the highest percentages of black residents, the unadjusted percentages of patients not receiving nephrology care before ESRD ranged from 29.3 to 36.5% (P < 0.0001) for white patients and from 32.5 to 41.1% (P < 0.0001) for black patients, respectively (Figure 1). The adjusted associations between zip code racial composition and receipt of pre-ESRD nephrology care were similar when estimated in white patients alone or in black patients alone, compared with those estimated in all patients (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Unadjusted proportion of patients not receiving nephrology care before initiating renal replacement therapy by race and zip code category. The 95% confidence intervals of the unadjusted percentages of patients not receiving nephrology care before renal replacement therapy is indicated with black bars.

The adjusted odds ratios for not receiving pre-ESRD nephrology care in black patients compared with those in white patients were examined within each zip code racial composition category separately. For zip code categories with <5%, 5 to 14.9%, 15 to 24.9%, 25 to 50%, and >50% black residents, the odds ratios were 1.21 (1.10 to 1.34), 1.13 (1.04 to 1.22), 1.05 (0.95 to 1.16), 1.14 (1.04 to 1.24), and 1.03 (0.91 to 1.16), respectively. There was also no significant interaction between patient race and zip code–level racial composition (P = 0.75).

A larger percentage of black patients (38.1%) compared with 30.3% of white patients had not received pre-ESRD nephrology care before commencing renal replacement therapy. In an unadjusted model examining the effect of patient race on receipt of nephrology care, sequential adjustment for patient demographic, clinical and socioeconomic factors, area poverty measures, and residential area composition, there was moderate attenuation of the odds ratio for nonreceipt of pre-ESRD care in black patients. The odds ratios decreased from 1.33 (1.29 to 1.37) to 1.12 (1.08 to 1.17), suggesting that the effect of black race on receipt of nephrology care was partly modified by residential area racial composition and each of the aforementioned domains (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effects of sequential adjustment for patient, area poverty, and racial composition on the odds ratio of black patients not receiving pre-ESRD care

| Model | Odds Ratio | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1.33 | 1.29 | 1.37 |

| B | 1.38 | 1.33 | 1.43 |

| C | 1.24 | 1.2 | 1.29 |

| D | 1.18 | 1.14 | 1.22 |

| E | 1.12 | 1.08 | 1.17 |

Model A examined the unadjusted effect of patient race on receipt of nephrology care. Model B added the remaining patient demographic and clinical variables to model A. In model C, patient-level socioeconomic characteristics were added to model B. In model D, area-level socioeconomic status markers were added to model C. Finally, in model E, zip code–level racial composition was added to model D.

Quality of Pre-ESRD Care

Among the subset of patients who had been referred for nephrology care before starting renal replacement therapy, there were no significant unadjusted or adjusted associations between zip code racial composition and either the timeliness of nephrology care or receipt of an arteriovenous fistula or graft versus a central venous catheter (Table 5). In unadjusted analyses, patients living in areas with a higher proportion of black residents were less likely to receive peritoneal dialysis and less likely to receive a pre-emptive renal transplant. However, the associations of these outcomes with residential area racial composition tended to disappear after adjustment for patient race and other potential confounders (Table 5). Patient race was likely the main factor explaining the difference between the unadjusted and adjusted outcomes for peritoneal dialysis and pre-emptive renal transplant in this study as the odds ratios for these outcomes in black patients were 0.6 (0.55 to 0.67) and 0.2 (0.17 to 0.28), respectively.

Table 5.

Unadjusted and adjusted secondary analyses by zip code category

| Outcomes | Odds Ratios | Percentage of Black Residents in Zip Code |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 to 14.9% | 15 to 24.9% | 25 to 50% | >50% | ||

| Late referral (n = 64,568) | Unadjusted | 0.98 (0.91 to 1.05) | 0.89 (0.81 to 0.99) | 0.84 (0.76 to 0.92) | 1.05 (0.96 to 1.16) |

| Adjusted | 0.98 (0.91 to 1.06) | 0.89 (0.8 to 0.99) | 0.82 (0.73 to 0.91) | 0.96 (0.85 to 1.09) | |

| Peritoneal dialysis (n = 64,568) | Unadjusted | 0.92 (0.84 to 1.02) | 0.89 (0.78 to 1.01) | 0.79 (0.70 to 0.89) | 0.6 (0.53 to 0.68) |

| Adjusted | 1 (0.9 to 1.1) | 1.02 (0.89 to 1.17) | 0.97 (0.84 to 1.12) | 0.9 (0.76 to 1.07) | |

| Pre-emptive renal transplant (n = 64,568) | Unadjusted | 0.64 (0.56 to 0.72) | 0.53 (0.44 to 0.64) | 0.35 (0.28 to 0.42) | 0.19 (0.15 to 0.24) |

| Adjusted | 0.75 (0.65 to 0.86) | 0.82 (0.66 to 1.02) | 0.87 (0.69 to 1.09) | 1 (0.73 to 1.36) | |

| AVF/AVG before HD (n = 56,394) | Unadjusted | 0.96 (0.91 to 1.02) | 0.99 (0.92 to 1.07) | 0.97 (0.9 to 1.04) | 1.01 (0.95 to 1.08) |

| Adjusted | 0.95 (0.9 to 1.01) | 0.97 (0.9 to 1.06) | 0.92 (0.85 to 1.00) | 0.93 (0.85 to 1.02) | |

The zip codes categories are listed by percentage of black residents with the referent category being <5% black residents. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios are shown with 95% confidence intervals on the left and right sides of the table respectively. LCI, lower 95% confidence interval; UCI, upper 95% confidence interval; HD, hemodialysis; AVF, arteriovenous fistula; AVG, arteriovenous graft. These models were adjusted for patient-level (age, gender, race, comorbidities, employment, and insurance status) and zip code–level (median per capita income, owner-occupied housing units, percentage of population below poverty line, high school and college education, percentage employed in professional/managerial positions) characteristics.

Discussion

In a large contemporary cohort of incident ESRD patients in the United States, 30.3% of white patients and 38.1% of black patients had not seen a nephrologist before onset of ESRD. Receipt of predialysis nephrology care appeared to be explained in part by where patients lived. Almost half of all black patients lived in zip codes in which most residents were also black. Both white and black patients living in zip codes with a higher proportion of black residents were less likely to have received nephrology care before initiation of renal replacement therapy even after accounting for differences in measures of socioeconomic status. Conversely, residential zip code racial composition appeared to contribute to the association of black race with not receiving nephrology care. Among patients who received nephrology care, however, residential area racial composition was not associated with performance on several measures of quality of predialysis nephrology care.

There is a growing volume of literature linking nephrology referral and several other clinical outcomes and quality measures among ESRD patients to residence location. A recent study demonstrated that dialysis patients living farther from a renal unit had a lower likelihood of being referred for pre-ESRD nephrology care.35 Previous studies have also reported poorer performance on dialysis quality measures, including timing of referral to nephrology care in areas with poor socioeconomic status. For example, Australian patients living in urban areas with higher socioeconomic deprivation scores were more likely to be referred late for nephrology care than other patients.30 In the United States, black and Asian and Pacific Islander dialysis patients living in higher poverty areas were less likely than white patients to be waitlisted for or to undergo renal transplantation.36,37 We are aware of only one study that examined the association of area racial composition with outcomes in dialysis patients. Rodriguez et al. demonstrated that patients living in predominantly black zip codes in the United States were less likely than patients living in areas with a low percentage of black residents to receive a renal transplant regardless of their own race.34

Although differences in zip code–level measures of socioeconomic status contributed to the observed association between zip code racial composition and receipt of pre-ESRD nephrology care, these measures did not completely explain this association. It is possible that measured differences in socioeconomic status between zip codes with differing racial composition do not fully capture true differences in socioeconomic status. Nonetheless, it may be that patients living in zip codes with a higher percentage of black residents face unique barriers to receipt of pre-ESRD nephrology care not faced by patients living in other poor zip codes. It is possible, for instance, that health care infrastructure may differ across zip codes with differing racial composition. Several prior studies among primary care patients indicate that clinics that primarily serve minority patients face greater organizational barriers to providing high-quality care and are less likely to have access to specialist services.38,39 Patients living in predominantly black neighborhoods may also find less community support for healthy behaviors and for interaction with health care. Several studies have demonstrated that health foods such as fruit and vegetables and access to recreational facilities may be more limited in predominantly black urban areas.40–43 Cultural and health beliefs and language, communication, and trust barriers may prevent access to health care44 and the availability of resources such as community support groups to reduce these barriers may vary by residential area.

Our study has several limitations. First, we were not able to examine patterns of referral among patients with chronic kidney disease who did not initiate renal replacement therapy. Second, there may have been some misclassification of zip code racial composition because we used the 2000 U.S. census to estimate the racial composition of zip codes in 2005 and 2006. Third, our analyses were conducted at the zip code level rather than finer levels of geographic resolution such as the census block or census tract because these data are not available from the United States Renal Data System (USRDS). Zip codes are geographic areas created by the United States postal service and thus may not always identify unified geographic areas (e.g., neighborhood) and may be less likely to identify homogenous populations than census blocks or tracts.45,46 Nonetheless, utilizing zip codes instead of census blocks or tracts creates a more conservative bias of socioeconomic health gradients.45–47 Fourth, we cannot exclude potential systematic variability among facilities in reporting of predialysis nephrology care as these questions on the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services form 2728 have not been validated. Finally, differences between patients in rate of change in estimated GFR before dialysis initiation might reasonably influence likelihood of nephrology referral. However, information on predialysis estimated GFR is not available in the data sources for this study.

In the United States, >40% of black patients who initiate renal replacement therapy live in zip codes where most residents are also black. Regardless of race, patients living in these areas were less likely to have received nephrology care before onset of ESRD. These differences were partly, but not completely, explained by differences in socioeconomic status between zip codes with differing racial composition. However, among patients referred to a nephrologist, quality of nephrology care received by patients living in these areas differed little by zip code racial composition. It is possible that the concentration of a large proportion of black ESRD patients in a relatively small number of residential zip codes may provide opportunities to reduce racial disparities in access to nephrology care via targeted area–based approaches.

Concise Methods

Design, Data Sources, and Patients

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using patient-level data from the USRDS, a national ESRD registry, and zip code–level data from the 2000 U.S. Census. In 2005, USRDS began recording information on receipt of nephrology care before initiation of renal replacement therapy (dialysis or transplantation). Patients were potentially eligible for inclusion in our cohort if they were between the ages of 18 and 100 years, were either black or white, and initiated renal replacement therapy between January 2005 and October 2006. We excluded patients whose residential zip code listed in USRDS did not match a zip code tabulation area in the 2000 U.S. Census and those who were missing information on receipt of nephrology care before initiation of renal replacement therapy.

Primary Predictor Variable

The primary predictor variable was the percentage of black residents living in each patient's zip code at the time of onset of renal replacement therapy. Zip codes were divided into five categories by percentage of residents who were black as follows: <5%, 5 to 14.9%, 15 to 24.9%, 25 to 50%, and >50%. These percentages were selected so that receipt of pre-ESRD care could be examined specifically in predominantly black zip codes and in zip codes where the percentage of black residents was below the national average (15%).

Other Predictor Variables

Patient factors included age, gender, race, comorbidities, employment status at form completion, and medical insurance coverage and these were obtained from the USRDS data. Comorbidities consisted of cardiac disease, diabetes, stroke, hypertension, and peripheral vascular disease. Insurance categories included Medicare, Medicaid, Veterans Affairs insurance, employee group coverage, other insurance, and no coverage. Zip code variables were obtained from the U.S. Census 2000 data and included median per capita income, percentage of people in the zip code with a high school and college education, percentage of owner-occupied housing units, percentage of the zip code population below the poverty line, and percentage of the zip code population employed in a professional or managerial position.

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome measure was whether or not patients received nephrology care before initiation of renal replacement therapy. At onset of ESRD, each patient's provider completes the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services' Medical Evidence Form (form 2728-U3). Our analyses were based on responses to the question: “Before ESRD therapy, was the patient under the care of a nephrologist?” Potential responses to this question were “yes,” “no,” and “unknown.”

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive Statistics

The median values of continuous patient- and zip code–level variables were compared across zip code racial composition categories using the Kruskal-Wallis test (Tables 1 and 2). The χ2 test was used to compare the distribution of categorical variables across zip code categories (Tables 1 and 2).

Zip Code Racial Composition and Receipt of Pre-ESRD Nephrology Care

The Mantel-Haenszel test was used to examine whether there were trends in lack of pre-ESRD nephrology care across zip code categories. The adjusted association of the racial composition of patients' zip code and receipt of nephrology care was assessed using a logistic regression model estimated using generalized estimating equation (GEE) methods to account for the clustering of patients within zip codes. Analyses adjusted for both patient-level characteristics and zip code–level measures of socioeconomic status.

To assess the effects of sequential adjustment for patient-level and residential area factors, sets of variables were sequentially added to a model explaining the association between residential area racial composition and receipt of nephrology care. The baseline model (model 1) included residential area racial composition as the only predictor variable. In model 2, patient race alone was added to model 1; in model 3, patient demographic and clinical variables were added to model 2. Model 4 added patient-level socioeconomic status variables to the previous model, whereas in model 5, zip code–level socioeconomic variables were added to model 4 (Table 3).

Associations of Patient Race and Area Poverty with Receipt of Pre-ESRD Nephrology Care

To determine whether the association between residential area racial composition and receipt of pre-ESRD nephrology care was present in both black patients and white patients, we conducted a set of stratified analyses. The unadjusted and adjusted effect of residential area composition on receipt of nephrology care was determined in black patients and white patients separately (Table 3 and Figure 1). Adjusted models included all patient demographic, clinical, socioeconomic, and area-level socioeconomic covariates.

Additionally, to examine the effect of patient race on receipt of nephrology care in each residential area composition category, we fit a separate regression model to examine the black versus white odds ratio for not receiving pre-ESRD care within each of the five residential area racial composition categories. These analyses adjusted for both patient- and zip code–level variables. Finally, we tested for an interaction between patient race and residential area racial composition on receipt of pre-ESRD nephrology care in the logistic regression model containing all patient demographic, clinical, socioeconomic, and area-level socioeconomic covariates.

To determine whether zip code racial composition modified the effect of patient race on receipt of pre-ESRD nephrology care, sequential adjustment for patient, area poverty, and racial composition on the odds ratio of black patients not receiving pre-ESRD care was examined. Model A examined the unadjusted effect of patient race on receipt of nephrology care. Model B added the remaining patient demographic and clinical variables to model A. In model C, patient-level socioeconomic characteristics were added to model B. In model D, area-level socioeconomic status markers were added to model C. Finally, in model E, zip code–level racial composition was added to model D (Table 4).

Quality of Pre-ESRD Care

To determine whether the quality and timeliness of nephrology care varied by residential area racial composition among patients who received this care, we examined the following secondary outcomes: (1) Whether patients had been referred to a nephrologist in a timely fashion (initial visit more than versus less than 6 months before dialysis initiation); (2) whether dialysis patients received peritoneal dialysis (versus hemodialysis) as their initial modality; (3) whether patients received a pre-emptive renal transplant as their first modality; and (4) whether hemodialysis patients had a permanent arteriovenous access placement (fistula or graft versus a central venous catheter) by the time of dialysis initiation (Table 5). We used the same analytic approach for these secondary analyses as for the primary analysis.

The institutional review board of the University of California, San Francisco approved the study and the Ethics Review Board of the University of Western Ontario reviewed the study protocol and decided that it did not require a full review process. The funding sources had no role in the design, conduct, or analysis of this study or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclosures

S.P. received a travel grant to present an abstract from this work at the World Congress of Nephrology in Milan, Italy, in May 2009. P.C.A. is supported by a Career Investigator Award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario. A.F. is supported by a K23RR18342 award from the National Institutes of Health/National Centre for Research Resources. A.M.O. is supported by a Beeson Career Development Award from the National Institute of Aging (1K23AG28980) and receives royalties from UpToDate and an honorarium from the Japanese Society for Foot Care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the United States Renal Data System and the United States Census for use of their data. The data reported here have been supplied by the United States Renal Data System (USRDS). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the U.S. government. Abstracts from this work were presented at the World Congress of Nephrology, Milan, Italy, May 22 through 26, 2009 and at the American Society of Nephrology conference, San Diego, California, October 27 through November 1, 2009 in poster format.

The institutional review board of the University of California, San Francisco approved the study and the Ethics Review Board of the University of Western Ontario reviewed the study protocol and decided that it did not require a full review process. The funding sources had no role in the design, conduct, or analysis of this study or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

See related editorial, “Neighborhoods, Race, and Nephrology Care,” on pages 1068–1070.

REFERENCES

- 1. Levey AS, Coresh J, Balk E, Kausz AT, Levin A, Steffes MW, Hogg RJ, Perrone RD, Lau J, Eknoyan G: National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Ann Intern Med 139: 137–147, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Avorn J, Winkelmayer WC, Bohn RL, Levin R, Glynn RJ, Levy E, Owen W, Jr: Delayed nephrologist referral and inadequate vascular access in patients with advanced chronic kidney failure. J Clin Epidemiol 55: 711–716, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lameire N, Wauters JP, Teruel JL, Van Biesen W, Vanholder R: An update on the referral pattern of patients with end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int Suppl 80: 27–34, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McClellan WM, Wasse H, McClellan AC, Kipp A, Waller LA, Rocco MV: Treatment center and geographic variability in pre-ESRD care associate with increased mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 1078–1085, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. United States Renal Data System (USRDS): Standard analysis files, core CD Minneapolis, MN, USRDS Coordination Center, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kazmi WH, Obrador GT, Khan SS, Pereira BJ, Kausz AT: Late nephrology referral and mortality among patients with end-stage renal disease: A propensity score analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 19: 1808–1814, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stack AG: Impact of timing of nephrology referral and pre-ESRD care on mortality risk among new ESRD patients in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 41: 310–318, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lin CL, Chuang FR, Wu CF, Yang CT: Early referral as an independent predictor of clinical outcome in end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis and continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Ren Fail 26: 531–537, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kinchen KS, Sadler J, Fink N, Brookmeyer R, Klag MJ, Levy AS, Powe NR: The timing of specialist evaluation in chronic kidney disease and mortality. Ann Intern Med 137: 479–486, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arora P, Kausz AT, Obrador GT, Ruthazer R, Khan S, Jenuleson CS, Meyer KB, Pereira BJ: Hospital utilization among chronic dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 740–746, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cass A, Cunningham J, Snelling P, Ayanian JZ: Late referral to a nephrologist reduces access to renal transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis 42: 1043–1049, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Winkelmayer WC, Mehta J, Chandraker A, Owen WF, Jr, Avorn J: Predialysis nephrologist care and access to kidney transplantation in the United States. Am J Transplant 7: 872–879, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ortega T, Ortega F, Diaz-Corte C, Rebollo P, Ma Baltar J, Alvarez-Grande J: The timely construction of arteriovenous fistulae: A key to reducing morbidity and mortality and to improving cost management. Nephrol Dial Transplant 20: 598–603, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sabath E, Vega O, Correa-Rotter R: Early referral to the nephrologist: Impact on initial hospitalization and the first 6 months of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Rev Invest Clin 55: 489–493, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Navaneethan SD, Nigwekar S, Sengodan M, Anand E, Kadam S, Jeevanatham V, Grieff M, Choudhry W: Referral to nephrologists for chronic kidney disease care: Is non-diabetic kidney disease ignored? Nephron Clin Pract 106: c113–c118, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ravani P, Marinangeli G, Stacchiotti L, Malberti F: Structured pre-dialysis programs: More than just timely referral? J Nephrol 16: 862–869, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee H, Manns B, Taub K, Ghali WA, Dean S, Johnson D, Donaldson C: Cost analysis of ongoing care of patients with end-stage renal disease: The impact of dialysis modality and dialysis access. Am J Kidney Dis 40: 611–622, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Manns BJ, Taub K, Vanderstraeten C, Jones H, Mills C, Visser M, McLaughlin K: The impact of education on chronic kidney disease patients' plans to initiate dialysis with self-care dialysis: A randomized trial. Kidney Int 68: 1777–1783, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Powe NR: To have and have not: Health and health care disparities in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 64: 763–772, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Obialo CI, Ofili EO, Quarshie A, Martin PC: Ultralate referral and presentation for renal replacement therapy: Socioeconomic implications. Am J Kidney Dis 46: 881–886, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ifudu O, Dawood M, Iofel Y, Valcourt JS, Friedman EA: Delayed referral of African-American, Hispanic, and older patients with chronic renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis 33: 728–733, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fine RN, Tejani A, Sullivan EK: Pre-emptive renal transplantation in children: Report of the North American Pediatric Renal Transplant Cooperative Study (NAPRTCS). Clin Transplant 8: 474–478, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Omoloja A, Stolfi A, Mitsnefes M: Racial differences in pediatric renal transplantation-24-year single center experience. J Natl Med Assoc 98: 154–157, 2006 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Barker-Cummings C, McClellan W, Soucie JM, Krisher J: Ethnic differences in the use of peritoneal dialysis as initial treatment for end-stage renal disease. JAMA 274: 1858–1862, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lok CE, Allon M, Moist L, Oliver MJ, Shah H, Zimmerman D: Risk equation determining unsuccessful cannulation events and failure to maturation in arteriovenous fistulas (REDUCE FTM I). J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 3204–3212, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hopson S, Frankenfield D, Rocco M, McClellan W: Variability in reasons for hemodialysis catheter use by race, sex, and geography: Findings from the ESRD Clinical Performance Measures Project. Am J Kidney Dis 52: 753–760, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kausz AT, Obrador GT, Arora P, Ruthazer R, Levey AS, Pereira BJ: Late initiation of dialysis among women and ethnic minorities in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 2351–2357, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Winkelmayer WC, Glynn RJ, Levin R, Owen WF, Jr, Avorn J: Determinants of delayed nephrologist referral in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 38: 1178–1184, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Boulware LE, Troll MU, Jaar BG, Myers DI, Powe NR: Identification and referral of patients with progressive CKD: A national study. Am J Kidney Dis 48: 192–204, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cass A, Cunningham J, Snelling P, Wang Z, Hoy W: Urban disadvantage and delayed nephrology referral in Australia. Health Place 9: 175–182, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. White P, James V, Ansell D, Lodhi V, Donovan KL: Equity of access to dialysis facilities in Wales. QJM 99: 445–452, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Christie S, Morgan G, Heaven M, Sandifer Q, Woerden H: Analysis of renal service provision in south and mid Wales. Public Health 119: 738–742, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Parry RG, Crowe A, Stevens JM, Mason JC, Roderick P: Referral of elderly patients with severe renal failure: Questionnaire survey of physicians. BMJ 313: 466, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rodriguez RA, Sen S, Mehta K, Moody-Ayers S, Bacchetti P, O'Hare AM: Geography matters: Relationships among urban residential segregation, dialysis facilities, and patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med 146: 493–501, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Boyle PJ, Kudlac H, Williams AJ: Geographical variation in the referral of patients with chronic end stage renal failure for renal replacement therapy. QJM 89: 151–157, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Patzer RE, Amaral S, Wasse H, Volkova N, Kleinbaum D, McClellan WM: Neighborhood poverty and racial disparities in kidney transplant waitlisting. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 1333–1340, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hall YN, O'Hare AM, Young BA, Boyko EJ, Chertow GM: Neighborhood poverty and kidney transplantation among US Asians and Pacific Islanders with end-stage renal disease. Am J Transplant 8: 2402–2409, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bach PB, Pham HH, Schrag D, Tate RC, Hargraves JL: Primary care physicians who treat blacks and whites. N Engl J Med 351: 575–584, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Varkey AB, Manwell LB, Williams ES, Ibrahim SA, Brown RL, Bobula JA, Horner-Ibler BA, Schwartz MD, Konrad TR, Wiltshire JC, Linzer M: Separate and unequal: Clinics where minority and nonminority patients receive primary care. Arch Intern Med 169: 243–250, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Galvez MP, Morland K, Raines C, Kobil J, Siskind J, Godbold J, Brenner B: Race and food store availability in an inner-city neighbourhood. Public Health Nutr 11: 624–631, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Morland K, Filomena S: Disparities in the availability of fruits and vegetables between racially segregated urban neighbourhoods. Public Health Nutr 10: 1481–1489, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zenk SN, Schulz AJ, Israel BA, James SA, Bao S, Wilson ML: Neighborhood racial composition, neighborhood poverty, and the spatial accessibility of supermarkets in metropolitan Detroit. Am J Public Health 95: 660–667, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Moore LV, Diez Roux AV, Evenson KR, McGinn AP, Brines SJ: Availability of recreational resources in minority and low socioeconomic status areas. Am J Prev Med 34: 16–22, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Carpenter WR, Godley PA, Clark JA, Talcott JA, Finnegan T, Mishel M, Bensen J, Rayford W, Su LJ, Fontham ET, Mohler JL: Racial differences in trust and regular source of patient care and the implications for prostate cancer screening use. Cancer 115: 5048–5059, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Rehkopf DH, Subramanian SV: Race/ethnicity, gender, and monitoring socioeconomic gradients in health: A comparison of area-based socioeconomic measures–the public health disparities geocoding project. Am J Public Health 93: 1655–1671, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Soobader MJ, Subramanian SV, Carson R: Geocoding and monitoring of US socioeconomic inequalities in mortality and cancer incidence: Does the choice of area-based measure and geographic level matter?: The Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Epidemiol 156: 471–482, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Thomas AJ, Eberly LE, Davey Smith G, Neaton JD: ZIP-code-based versus tract-based income measures as long-term risk-adjusted mortality predictors. Am J Epidemiol 164: 586–590, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]