Summary

A polarized epithelium in the non-metazoan Dictyostelium discoideum requires α-catenin and β-catenin but not classical cadherins, polarity proteins or Wnt signaling.

A fundamental characteristic of metazoans is the formation of a simple, polarized epithelium. In higher animals, the structural integrity and functional polarization of simple epithelia require a cell-cell adhesion complex containing a classical cadherin, the Wnt-signaling protein β-catenin and the actin-binding protein α-catenin. We show that the non-metazoan Dictyostelium discoideum forms a polarized epithelium that is essential for multicellular development. Although D. discoideum lacks a cadherin homolog, we identify an α-catenin ortholog that binds a β-catenin-related protein. Both proteins are essential for formation of the epithelium, polarized protein secretion and proper multicellular morphogenesis. Thus the organizational principles of metazoan multicellularity may be more ancient than previously recognized, and the role of the catenins in cell polarity predates the evolution of Wnt signaling and classical cadherins.

A simple epithelium is the most basic tissue type in metazoans (multicellular animals). It is the first overt sign of cellular differentiation during embryogenesis, and is important for the morphogenesis of many tissues and homeostasis in the adult (1). A simple epithelium comprises a cell monolayer surrounding a luminal space. The cells have a polarized organization of plasma membrane proteins, organelles and cytoskeletal networks that together regulate the directional absorption and secretion of proteins and other solutes (1).

The structural integrity and functional polarity of epithelial tissues in higher animals require cell-cell adhesion mediated by classical cadherins (2). Adhesion provides a spatial cue that initiates cell polarization via recruitment of cadherin-associated cytosolic proteins (3), including the Wnt signaling protein β-catenin (4) and the actin-binding protein α-catenin (5). Classical cadherins, which have extracellular cadherin repeats (6) and a conserved cytoplasmic domain that can bind β-catenin (7), are found in all multicellular animals including sponges, but not in choanoflagellates (8-10), suggesting that classical cadherins are restricted to metazoans. However, the evolutionary history of the catenins is unknown, and thus it is unclear how the cadherin-catenin complex evolved to mediate epithelial polarity in metazoans.

The non-metazoan social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum undergoes multicellular morphogenesis in response to starvation: single cells aggregate and undergo culmination to form a fruiting body, which comprises a rigid stalk that supports a collection of spores (Fig. 1a) (11). The mechanical rigidity of the stalk is due to the stalk tube, which contains cellulose and the extracellular matrix proteins EcmA/B (Fig. 1b) (12, 13). Harwood and colleagues described a ring of cells surrounding the stalk tube at the tip of the culminant (Fig. 1a, b and Movie S1) and speculated that these cells might contribute to stalk formation during culmination (14, 15). However, the subcellular organization and function of tip cells have not been characterized.

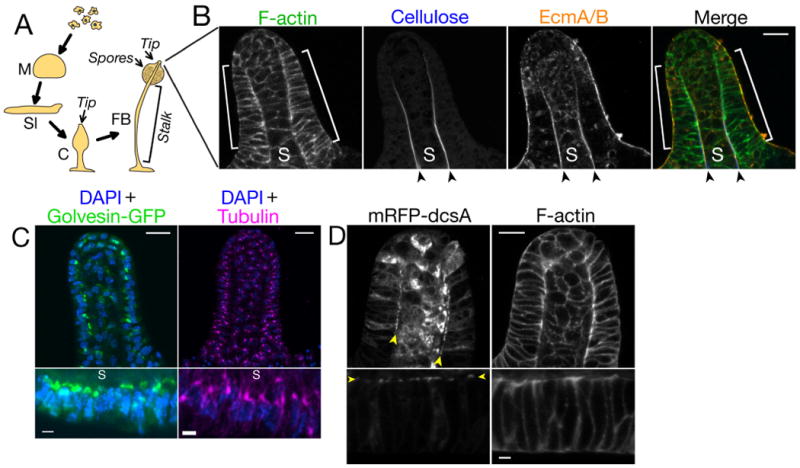

Figure 1.

A) D. discoideum developmental process. Abbreviations: M, mound; Sl, slug; C, culminant; FB, fruiting body.

B) Confocal section of the tip of a wild-type culminant. Brackets indicate the tip epithelium; arrowheads indicate the stalk tube; S indicates the stalk.

C) Maximum intensity projections showing Golgi (left), centrosomes (right) and nuclei (DAPI stain) in the entire tip (upper panels) or tip epithelium (lower panels).

D) Confocal section of the tip (upper panels) and tip epithelium (lower panels) in a wild-type culminant expressing cellulose synthase (mRFP-dcsA). In tip epithelia cells, mRFP-dcsA localizes to the tip epithelial cell membrane adjacent to the stalk (arrowheads). mRFP-dcsA is also expressed in the stalk cells.

Scale bars: 10 μm in lower-magnification views (B-D) and 2 μm in higher-magnification views (C&D). In views of the tip epithelium, the top of the images faces the stalk.

We confirmed the earlier observation (14) that the tip consists of an organized monolayer of cells surrounding the stalk (Fig. 1b and Movie S1). Additionally, we found that these cells have a distinctive polarized organization: centrosomes and Golgi localized to the stalk side of nuclei (Fig. 1c), and the transmembrane protein cellulose synthase (encoded by the dcsA gene (12)) localized to the plasma membrane domain adjacent to the stalk tube (Fig. 1d). Thus, D. discoideum tip cells have a subcellular organization characteristic of a simple polarized epithelium (Fig. S1), and we refer to these cells as the tip epithelium.

In metazoans, β-catenin and α-catenin are essential for formation of polarized simple epithelia (16, 17). A β-catenin-related protein called Aardvark has been identified in D. discoideum (Fig. S2) (9, 14). We identified a member of the α-catenin family in this organism, which we named Ddα-catenin on the basis of structural and functional characteristics (9). Ddα-catenin is approximately 35% homologous to human α-catenins and their paralog vinculin (Figs. 2a, S3-S5). Ddα-catenin was expressed at low levels in single D. discoideum cells but was up-regulated during multicellular development (Fig. 2b). Endogenous Ddα-catenin localized to cell-cell contacts in the slug and fruiting body (Figs. S6, S7a), and especially in columnar cells of the tip epithelium (Fig. 2c).

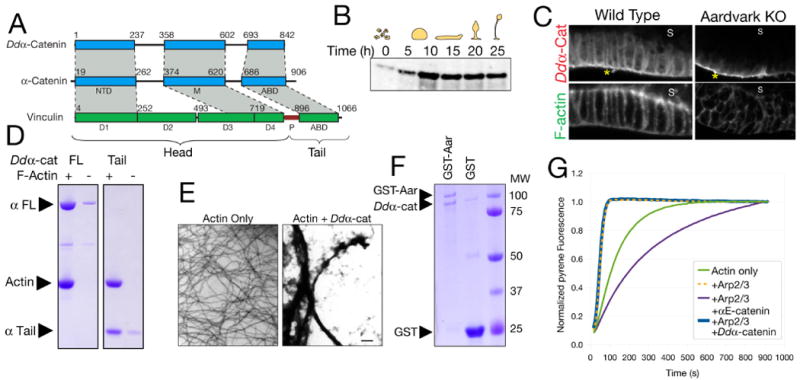

Figure 2.

A) Primary structures of Ddα-catenin and human α-catenin and vinculin. Regions of homology are shaded gray. NTD, N-terminal domain; M, M-domain; ABD, actin-binding domain; P, proline-rich region.

B) Western blot for Ddα-catenin at the indicated developmental time points.

C) Confocal sections of the tip epithelium in a wild-type culminant and an Aardvark knockout (14). Asterisks indicate non-specific signal on the exterior of the culminant (Fig. S8).

D) High-speed pelleting assay demonstrating binding of 5 μM full-length (FL) or the isolated tail domain of Ddα-catenin to 5 μM F-actin.

E) Negative-stain electron micrographs of actin filaments in the absence or presence of 5 μM Ddα-catenin. Scale bar: 500 nm.

F) Bead-bound fractions from a GST pull-down assay demonstrating binding of Ddα-catenin (10 μM) to GST-Aardvark (∼0.3 μM). 5 μM GST is a negative control.

G) Pyrene actin polymerization assays were performed in the presence of N-WASp VCA domain and the indicated additional proteins. αE-catenin or Ddα-catenin concentrations were 5 μM.

We examined whether Ddα-catenin is similar to metazoan α-catenin or vinculin, or both (9). Like metazoan α-catenin, Ddα-catenin bound and bundled actin filaments (Fig. 2d, e). Ddα-catenin bound to the D. discoideum β-catenin-related protein Aardvark (Fig. 2f) and mouse β-catenin (Fig. S9), and its localization to cell-cell contacts in vivo was Aardvark-dependent (Figs. 2c, S7). Unlike mammalian αE-catenin, but like the C. elegans α-catenin ortholog HMP-1 (18), purified Ddα-catenin was monomeric in solution (Fig. S10), and it did not inhibit the actin-nucleating activity of the Arp2/3 complex (Fig. 2g). In contrast to its overall similarity to metazoan α-catenin, Ddα-catenin lacked key properties of metazoan vinculin (Figs. S11, S12) (9). Because Ddα-catenin represents the most basally-branching members of the α-catenin/vinculin family (Fig. S4), these data indicate that the ancestral member of this protein family was probably α-catenin-like.

To test whether Ddα-catenin and its binding partner Aardvark are involved in the polarized organization of the tip epithelium, we depleted Ddα-catenin using RNA interference (Fig. S13). When Ddα-catenin was depleted below a level that could be detected by immunofluorescence, multicellular development arrested at the onset of culmination (Fig. 3a). Tip cells were disorganized and the stalk and tip epithelium were absent (Figs. 3a, b). Moreover, the distributions of Golgi and centrosomes were not polarized (Figs. 3c, S14), and cellulose synthase was mislocalized intracellularly (Fig. 3d). Culminants with partial Ddα-catenin knockdown exhibited a milder phenotype: a distinct stalk and tip epithelium formed, but the epithelium appeared disorganized and was more than one cell layer thick (Fig. 3b), and organelles (Figs. 3c, S14, arrowheads) and cellulose synthase (Fig. 3d) were not correctly polarized. Prestalk cell differentiation was unaffected in Ddα-catenin knockdowns, indicating that the lack of a stalk was not due to a failure of the developmental program to correctly specify cell types (Fig. S15).

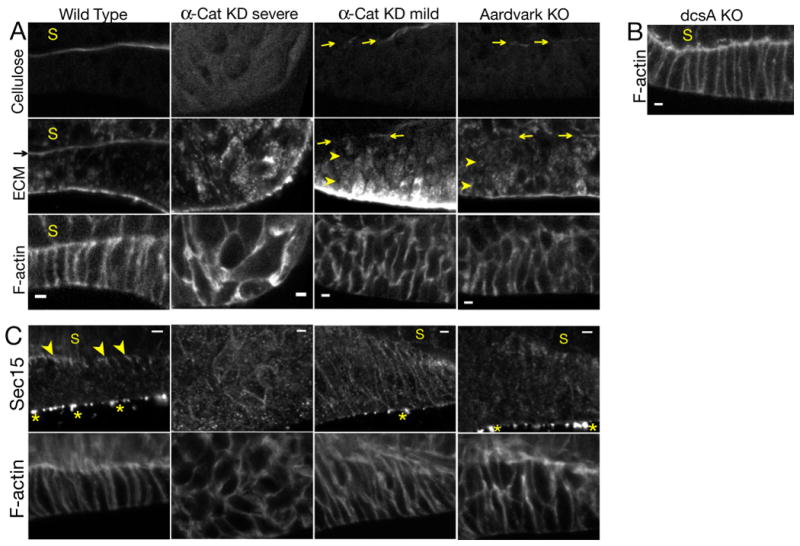

Figure 3.

A) Early culminants formed by wild-type and Ddα-catenin knockdown cells.

B) Confocal sections of the tip in culminants of the indicated cells. Severe and mild Ddα-catenin knockdown phenotypes are distinguished by the absence or presence, respectively, of a nascent stalk. Asterisk indicates non-specific signal on the exterior of the culminant (Fig. S8).

C) Maximum intensity projections showing centrosomes and nuclei. Arrowheads indicate centrosomes that are mislocalized relative to wild type (Fig. 1c). Lower panels show higher-magnification views of the boxed regions.

D) Confocal sections of the tip (upper panels) and tip epithelium (lower panels) in culminants of the indicated cells expressing mRFP-dcsA (cellulose synthase). Arrowheads indicate residual localization of mRFP-dcsA in mild Ddα-catenin knockdowns and Aardvark knockouts. Scale bars: 25 μm (A), 10 μm in lower-magnification views (B-D) or 2 μm in higher-magnification views (C&D).

Similar results were obtained with an Aardvark knockout strain (14) (Figs. 3b-d, S14), indicating that both Ddα-catenin and Aardvark are required to organize and polarize the tip epithelium during culmination. Harwood and colleagues reported that Aardvark was necessary for formation of actin-associated cell-cell junctions in tip cells that appeared similar to adherens junctions at the ultrastructural level (14, 15, 19). However, we found that Aardvark knockouts formed junctions similar to wild-type, as did Ddα-catenin knockdowns (Fig. S16). Because these junctions do not require Ddα-catenin or Aardvark, and D. discoideum does not have classical cadherins, we conclude that these junctions are unlikely to be molecularly equivalent to metazoan adherens junctions (9) and are not involved in the developmental phenotypes described above.

To better understand the developmental mechanism underlying impaired stalk formation in Ddα-catenin knockdowns and Aardvark knockouts, we examined whether the stalk tube components cellulose and EcmA/B were correctly distributed. Accumulation of cellulose and EcmA/B in the stalk tube was absent in severe Ddα-catenin knockdowns, and was strongly reduced in mild Ddα-catenin knockdowns and Aardvark knockouts (Figs. 4a, S17a, b) (19). Note that cellulose synthase (compare Figs. 3d and 1d) and EcmA/B (Figs. 4a, S17a, b, arrowheads) were mislocalized intracellularly in tip epithelial cells but were unchanged in stalk cells, indicating that tip epithelial cells are the primary source of secreted cellulose and EcmA/B in the stalk tube. Confirming this interpretation, we observed rare cases in which half of the tip epithelium was better organized than the other half, and in those culminants cellulose and EcmA/B accumulated in the stalk tube adjacent to the better-organized tip epithelial cells (Fig. S18). Significantly, in cellulose synthase knockouts, which do not form a stalk tube (12), the tip epithelium was morphologically normal and EcmA/B were secreted (Fig. 4b, S17c), demonstrating that tip epithelial polarity is genetically upstream of stalk tube formation.

Figure 4.

A) Confocal sections of the tip epithelium in culminants of the indicated cells. Arrows indicate deposition of small amounts of extracellular cellulose and EcmA/B in a nascent stalk tube. Arrowheads indicate intracellular accumulation of EcmA/B.

B) Confocal section of the tip epithelium in a culminant of cellulose synthase (dcsA) knockout cells (12).

C) Confocal sections of tip epithelia in culminants of the indicated cells. Arrowheads indicate Sec15 localization. Asterisks indicate non-specific signal on the exterior of the culminant (Fig. S8).

Scale bars: 2 μm.

Since tip epithelial cells appear to secrete cellulose and EcmA/B directionally to form an organized stalk tube, we tested whether the secretory pathway was polarized in wild-type and mutant strains. Sec15, a component of the Exocyst complex involved in polarized exocytosis in diverse systems (20), localized adjacent to the stalk tube (Fig. 4c), reminiscent of Exocyst localization in polarized mammalian epithelial cells (21), and this distribution was strongly disrupted in Ddα-catenin knockdowns and Aardvark knockouts (Fig. 4c). The molecular mechanisms underlying the polarized organization of the Exocyst in D. discoideum are unknown, but it is interesting to note that the catenins have been reported to associate in a complex with Exocyst components in mammalian cells (22).

Taken together with earlier results (14), our work shows that the non-metazoan Dictyostelium discoideum has a bona fide polarized epithelium consisting of a single layer of structurally and functionally polarized cells that secrete proteins into a luminal space (Fig. S1). Significantly, epithelial polarity in both metazoans and D. discoideum requires homologs of α-catenin and β-catenin, indicating a close evolutionary relationship between D. discoideum and metazoan epithelia. Since D. discoideum lacks cadherins, Wnt signaling components and polarity proteins of the PAR, Crumbs and Scribble complexes (9), the conserved catenin complex appears to be an ancient functional module that mediates epithelial polarity in the absence of the more complicated machinery found in metazoans (1).

The fact that the catenin complex is essential for epithelial polarity in both D. discoideum and metazoans indicates that this complex likely functioned in cell polarity prior to the divergence of social amoebae and metazoans. It is possible that the catenins evolved initially to mediate cell polarity in a unicellular organism, and then were used to organize cell polarity in a multicellular context in both social amoebae and metazoans. Alternatively, the last common ancestor of social amoebae and metazoans may have formed a polarized epithelial tissue organized by the catenin complex, but epithelial polarity was lost in some intervening lineages (9). In either case, our results identify unexpected similarities in tissue organization between two groups of distantly related organisms that were thought to have evolved multicellularity independently (23), and thereby reveal molecular factors and organizational principles that may have contributed to the early evolution and diversification of animals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank numerous colleagues for reagents (9); T. Soldati for sharing Sec15 antibodies prior to publication; C. Carswell-Crumpton, N. Ghori, J. Perrino and T. Weiss for technical assistance; D. Ehrhardt, N. King, D.N. Robinson, T. Soldati, J.A. Spudich, M. Tsujioka, H. Warrick and members of the Nelson and Weis laboratories for discussions. This work was supported by a Stanford Graduate Fellowship and an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship (DJD), NIH GM035527 (WJN) and NIH GM56169 (WIW). Portions of this research were carried out at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, supported by the US DoE and NIGMS.

References and Notes

- 1.Bryant DM, Mostov KE. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:887. doi: 10.1038/nrm2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson WJ. Nature. 2003;422:766. doi: 10.1038/nature01602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson WJ. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2008;036:149. doi: 10.1042/BST0360149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clevers H. Cell. 2006;127:469. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rimm DL, Koslov ER, Kebriaei P, Cianci CD, Morrow JS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:8813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hulpiau P, Roy Fv. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:349. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huber AH, Weis WI. Cell. 2001;105:391. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00330-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Srivastava M, et al. Nature. 2010;466:720. doi: 10.1038/nature09201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Materials and methods and additional text are available as supporting online material.

- 10.Abedin M, King N. Science. 2008;319:946. doi: 10.1126/science.1151084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urushihara H. Development, Growth & Differentiation. 2008;50:S277. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2008.01013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blanton RL, Fuller D, Iranfar N, Grimson MJ, Loomis WF. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040565697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McRobbie SJ, Tilly R, Blight K, Ceccarelli A, Williams JG. Dev Biol. 1988;125:59. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grimson MJ, et al. Nature. 2000;408:727. doi: 10.1038/35047099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams HP, Harwood AJ. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2003;6:621. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watabe M, Nagafuchi A, Tsukita S, Takeichi M. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:247. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.1.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torres M, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwiatkowski AV, et al. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:14591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007349107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coates JC, et al. Mech Dev. 2002;116:117. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00152-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He B, Guo W. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:537. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grindstaff KK, et al. Cell. 1998;93:731. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81435-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yeaman C, Grindstaff KK, Nelson WJ. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:559. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.King N. Dev Cell. 2004;7:313. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.