Abstract

In this paper, we link age differences in gaze patterns toward emotional stimuli to later mood outcomes. While one might think that looking at more positive emotional material leads to better moods, and looking at more negative material leads to worse moods, it turns out that links between emotional looking and mood depend on age as well as individual differences. Though older people can feel good by looking more at positive material, in some cases young adults actually feel better by engaging visually with the negative. These age effects are further moderated by attentional abilities. Such findings suggest that different age groups may use looking differently, and this may reflect their preferences for using distinct emotion regulatory strategies. This work also serves as a reminder that regulatory efforts are not always successful at improving mood.

Keywords: aging, fixation, emotion regulation, attention

Everyday, we are surrounded by stimuli varying in valence: sad songs, funny internet videos, news that makes us angry on television. Among this variety of emotional information, we encounter stimuli that attract more or less attention. This begs the question, how does visual attention influence how we feel? It might seem intuitive that the best strategy for increasing positive feelings in a particular moment is to focus visual attention on positively-valenced stimuli and look relatively less at negatively-valenced stimuli. This paper considers whether this intuition stands up to empirical scrutiny. The verdict is that visual attention to positive stimuli helps some individuals increase positive feelings some of the time, but it depends on characteristics of the person and the situation. Overall, looking at positive stimuli is most useful for older individuals; this provides one potential mechanism that might explain age-related improvements in affective experience, as has been found in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (e.g., Carstensen et al., in press). Below, we describe methods we have used to investigate to what extent personal characteristics such as age impact how attention can be used to regulate affect, and in which contexts these effects are most heightened. Finally, we consider the implications of these findings for attention – emotion links at any age.

Age-related Positivity Effects in Visual Attention

With increasing age, individuals seem to experience more positive and less negative moods in day-to-day life (Carstensen, Pasupathi, Mayr, & Nesselroade, 2000; Carstensen et al., in pres; Charles, Reynolds, & Gatz, 2001). Such findings have been attributed to age-related improvements in emotion regulation for older adults (Carstensen, Isaacowitz, & Charles, 1999; Urry & Gross. 2010), leading researchers to investigate whether there are age differences in cognitive processing of emotional material. Interestingly, laboratory studies on age differences in memory have shown that older adults exhibit superior memory for positive, as opposed to negative or neutral information, while younger adults show the reversed pattern in their memory (e.g., Charles, Mather, & Carstensen, 2003; Mikles, Larkin, Reuter-Lorenz, & Carstensen, 2005; Spaniol, Voss, & Grady, 2008; Mather & Carstensen, 2005, for a review), though some studies have not found this pattern (e.g., Grühn, Smith & Baltes, 2005). This age-related memory bias is referred to as a positivity effect. A logical question then arose concerning whether memory effects arise due to age differences in attention to valenced stimuli. Selective attention toward positive, and away from negative information, may serve as a filter that supports the encoding of positive information, but not negative information.

Earlier studies in our laboratory directly investigated age differences in visual attention to emotional stimuli using eye-tracking. The advantage of eye-tracking is that it measures eye movements (or gaze patterns) occurring during the processing of emotional stimuli in nearly real-time, providing an ecological way to assess age differences in attentional preferences. Eye-tracking has also been used successfully to investigate the links between looking behaviors and underlying cognitive processes such as during reading comprehension (Rayner, 1998), and looking at print advertisements (Rayner, Miller & Rotello, 2008).

In the typical eye-tracking paradigm used in our research on age differences, participants’ eye movements are recorded while they freely view images varying in valence on a computer screen. A visual fixation is defined as a period in which gaze is directed within a 1° visual angle for at least 100 ms (Manor & Gordon, 2003), within the predetermined areas of interest (AOIs), usually regions that provide affective information. Using these AOIs, the primary attentional measure is calculated as the fixation percentage for each emotional area(s) of each image relative to the amount of fixation to the entire image.

In two studies, emotional-nonemotional (neutral) synthetic face pairs were presented to younger and older participants and their gaze patterns were assessed by comparing the fixation percentage to positive and negative versus neutral faces (i.e., preferences for the emotional face over the neutral face or vice versa; Isaacowitz, Wadlinger, Goren, & Wilson, 2006a, 2006b). The results from these studies revealed that older adults displayed what might be called “positive” gaze patterns, such that they showed looking preferences toward positive (happy) and away from some negative faces (angry and sad). Younger adults, on the other hand, showed either equal looking or slight preference toward negative (afraid) faces. These findings demonstrate that younger and older adults process emotionally-valenced stimuli with a differential gaze preference (see also Isaacowitz & Choi (2011), for a replication with non-face stimuli).

How can we account for age-related positive gaze patterns? One explanation is that age-related gaze patterns may simply reflect age differences in mood states (i.e., mood-congruent gaze patterns). Improved mood with age may lead older adults to increasingly process positive information, and/or decreasingly process negative information, to reflect or maintain positive mood. On the other hand, as motivations to enhance or maintain negative affect are most prevalent in adolescence (Riediger, Schmiedek, Wagner, & Lindenberger, 2009), younger individuals may find feeling negative to be useful. Thus, age differences in gaze patterns toward emotional information can be seen as instrumental (Tamir, 2009).

Another explanation is that as individuals grow older, they care more about emotion regulation. This idea was most comprehensively developed by socioemotional selectivity theory (SST; Carstensen et al., 1999; Carstensen & Turk-Charles, 1994). According to SST, changes in one’s time perspective occur with aging. These changes shift goals to focus upon the allocation of resources for emotion regulation. Younger adults have a sense of an unlimited future and are motivated to pursue knowledge-related goals, such as learning information that will benefit them in the future, even at the cost of current emotional satisfaction. Older adults, on the other hand, perceive their future time as limited and, are therefore motivated to regulate their emotions, which can benefit their current life. Conceptually, this age-related shift in motivational goals is thought to produce the positivity effect in information processing and also good moods (Carstensen & Mikels, 2005).

In an attempt to explicitly link positivity effects to motivation, one study examined whether motivation could produce the same fixation patterns observed in older adults by experimentally manipulating motivations (emotion regulation vs. information seeking) in younger adults (Xing & Isaacowitz, 2006). Participants in the emotion regulation group (told to manage how they feel while viewing images) looked much less at negative than positive images when compared with the control group (simply told to look at the images as if at home watching television). The information group (told to get as much information as possible from the images) looked equally at both negative and positive images. The finding that younger adults who were motivated to regulate their mood displayed decreased attention especially to the negative stimuli, supports the notion that when older adults show looking patterns away from negative stimuli, it could be guided by a motivational shift toward emotion regulation.

Linking Looking and Feeling: Gaze Patterns and Mood

These eye-tracking findings suggest that older adults may control their attentional focus, toward positive and away from negative stimuli, to regulate how they feel. However, those previous studies did not directly connect gaze patterns to mood; therefore, it is unclear whether older adults’ gaze patterns just reflected positive mood (as suggested by the simple mood-congruency explanation) or their attempt to use gaze to regulate their mood. To assess the association between gaze and mood, we needed variability in mood states so that some individuals had the opportunity to use gaze to regulate their mood and feel better.

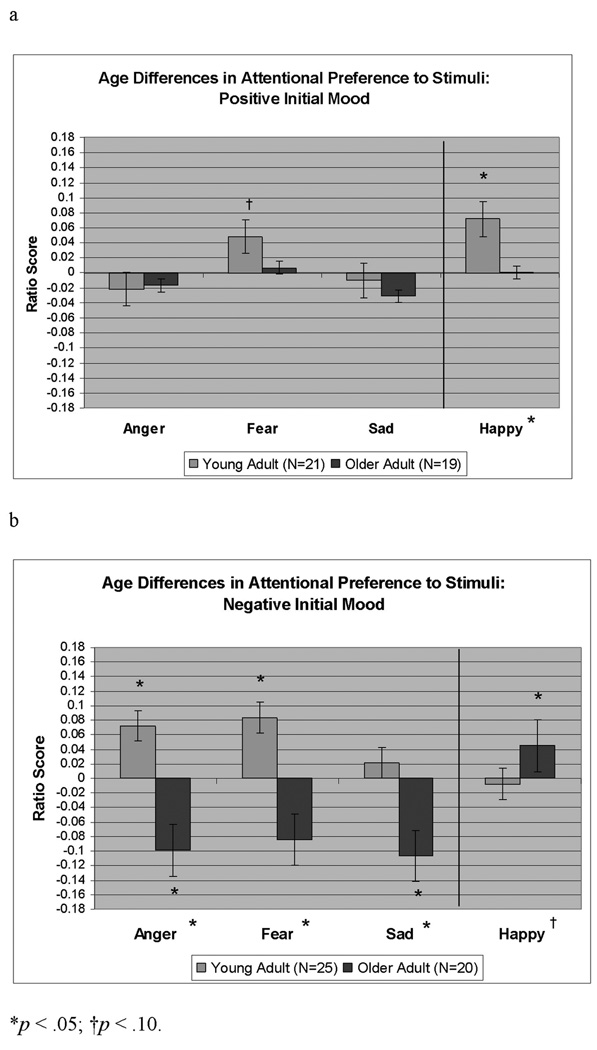

To address the issue of variability in moods, we assessed each participant’s mood before starting eye-tracking, using a potentiometer slider (Empirosoft Corporation, New York, NY). Age and mood had a significant interaction effect on gaze patterns (Isaacowitz, Toner, Goren, & Wilson, 2008). As shown in Figure 1, younger adults showed mood-congruent gaze patterns, such that they tended to show a more positive gaze pattern (toward happy faces) when in good moods (1a) and a more negative gaze pattern (toward angry and afraid faces) when in negative moods (1b). In contrast, older adults showed no significant gaze preferences when they started the eye-tracking task in positive or neutral moods. However, when starting the eye-tracking task in negative moods, they displayed positive gaze preferences such that they looked toward happy faces and away from angry and sad faces. Older adults’ use of positive gaze preferences when in bad moods could reflect their increased motivation toward emotion regulation, consistent with SST. It is less consistent with the simple mood-congruent looking idea, as older adults in negative moods showed more positive looking patterns.

Figure 1.

Fixation ratio scores by age groups and emotional face type, for participants starting in (a) a positive mood and (b) a negative mood. Notation significance next to a bar indicates that the ratio score for that cell is significantly different from zero, and notation of significance next the label for an emotional face type indicates a significant difference betweem age groups for that face type. From Isaacowitz, Toner, Goren, and Wilson (2008).

While younger adults’ mood-congruent looking patterns could simply reflect mood-congruency in their gaze; another possible explanation is that younger adults were actually trying to regulate out of their bad moods using an engagement strategy of visually attending to negative stimuli, perhaps as a way of figuring out how to use reappraisal and reinterpretation for regulation. This strategy is in contrast to older adults’ disengagement strategy in same context. How can this possible dissociation by age be understood? According to the process model of emotion regulation (Gross, 1998), emotion can be regulated using different strategies: Attentional deployment refers to directing one’s attention toward and away from certain aspects of emotional targets (which also can apply to real-time mood regulation in an environment full of potentially mood-disrupting stimuli). Positive gaze preferences related to a negative mood may thus reflect older adults’ use of attentional deployment to regulate their emotions.

Other possible regulatory strategies are described in the process model as well: Following attentional deployment is the strategy of cognitive reappraisal. Cognitive reappraisal involves modifying not attention toward the emotional stimulus, but rather, thoughts about the emotional stimulus. The ultimate goal of using cognitive reappraisal, then, is to use thought patterns to reduce emotional reaction. One study raised the concern that reappraisal may just be attentional deployment repackaged; in other words, when participants are told to reappraise an emotional stimulus, they just change how they look at it (van Reekum et al., 2007). However, more recent work in which gaze is held constant has found that reappraisal exists distinct from attentional deployment. Interestingly, in a study with younger adults (Urry, 2010), reappraisal only showed effects on expressive behavior when gaze was directed toward the most arousing aspect of the stimuli. This result suggests that reappraisal may not only be conceptually distinct from gaze and attentional deployment, but (at least in younger adults) there may be cases where gaze toward an emotional stimulus relates to successful reappraisal to lessen its impact. Other work suggests that the later reappraisal processes are initiated in an emotional situation, the more cognitively and physiologically demanding they are than some forms of attentional deployment (Sheppes, Catran, & Meiran, 2009; Sheppes & Meiran, 2008).

While older adults’ gaze patterns suggest their attempts to use attention deployment as a regulatory strategy, younger adults’ gaze patterns may help them use reappraisal as a regulatory strategy. Urry and Gross (2010) recently suggested that the efficiency of using some emotional regulation strategies declines with age due to age-related reduction in cognitive resources; however, older adults achieve successful emotion regulation by selecting and optimizing particular emotion regulation strategies that compensate for changes in resources. Supporting this, Shiota and Levenson (2009) demonstrated that older adults were less successful than younger adults at using cognitive reappraisal strategies, particularly when they were instructed to deliberately focus their attention on nonemotional aspects of the emotional situation to reduce the emotional responses. This is further supported by a recent neuroimaging study (Winecoff, LaBar, Madden, Cabeza, & Huettel, in press) revealing that use of reappraisal activated the lateral prefrontal region (implicated in cognitive control) in both younger and older adults. While exhibiting lower overall activation, older adults’ engagement of this region predicted their successful use of reappraisal strategies. In another study, younger and older adults directed their gaze to unpleasant emotional images and were instructed to use cognitive reappraisal to decrease negative emotions; older adults were less successful using this reappraisal strategy. The age-related effect was mediated by reduced activation in the dorsomedial and left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, regions also implicated in cognitive control (Opitz, Rauch, Terry, & Urry, in press). Thus, recent behavioral and neuroimaging findings support the idea that cognitive reappraisal relies heavily on cognitive resources, making implementation of this strategy increasingly difficult with age.

Downstream Effects of Gaze on Feeling Vary by Age and Attention

Demonstrating that positive gaze preferences arise when older adults are in a negative mood state, which they would presumably like to regulate out of, is one step toward showing that the function of positive gaze preferences in older adults helps them to regulate their mood. Questions remain as to whether younger adults’ negative gaze preferences reflect mood-congruence or their regulatory effort. A stronger functional account for both age groups would also require evidence that positive gaze preferences for older adults and negative gaze preferences for younger adults actually lead to better mood downstream. To test this, we have measured mood during eye tracking, rather than just before it. In order to measure real-time changes in feeling, and to assess the downstream outcomes of positive looking patterns, participants rated their moods continuously on a potentiometer slider without removing their gaze from the screen.

We first investigated mood change during eye tracking in data from the Isaacowitz et al. (2008) study. There were high levels of variability in mood change during the 20+ minutes of viewing synthetic face pairs. That said, on average, mood decreased across all participants, perhaps due to the monotonous and fatiguing nature of the task. Cluster analysis revealed four primary clusters of mood change during the task: one group that began positive and became somewhat more positive, two groups that began neutral and remained neutral, and one that began in a negative mood and became more negative over time (Stanley & Isaacowitz, 2011). This variability in moods in the experimental context is convenient for testing fixation-mood change links. Adding some complexity to the age trajectories of affective experience described above, in this lab-task setting, both the most positive and most negative subgroups represented more older than younger adults. More importantly, the most negative subgroup looked less at happy faces, had low cognitive ability and less mood stability than other groups.

Links between mood change and gaze depended not only on the age of the participant, but also on other individual characteristics. Mather and colleagues (Knight et al., 2007; Mather & Knight, 2005) have argued that because implementation of emotion regulation is a goal-directed, top-down controlled process, adequate cognitive control is necessary for older adults to display positivity effects in attention and memory. From this view, older adults’ positive gaze preferences reflect top-down interference from their emotion-focused goals which override more automatic responses to negative stimuli, and therefore require adequate cognitive control. This assertion is supported by the finding that older adults with better cognitive control (as measured by executive control tasks or dual-task situations) show the largest positivity effects in their gaze and memory (Knight et al., 2007; see also, Petrican, Moscovitch, & Schimmack, 2008, for a link between cognitive control and the retrieval of emotional memories; cf. Allard & Isaacowitz, 2008; Allard, Wadlinger, & Isaacowitz, 2010).

We assessed individual differences in cognitive control and more general attentional abilities using the Attention Network Test (ANT; Fan, McCandliss, Sommer, Raz, & Posner, 2002). The ANT allowed us to assess different aspects of attention. According to Posner and Petersen (1990), individuals can vary on three separate attentional functions; alerting (helps achieve and maintain a high state of sensitivity); orienting (used in information selection from sensory input); and executive control (involved in conflict resolution). In the ANT, the efficiency of the three attentional networks is determined by measuring the relative response times to combinations of arrows or cue trials (Fan et al., 2002).

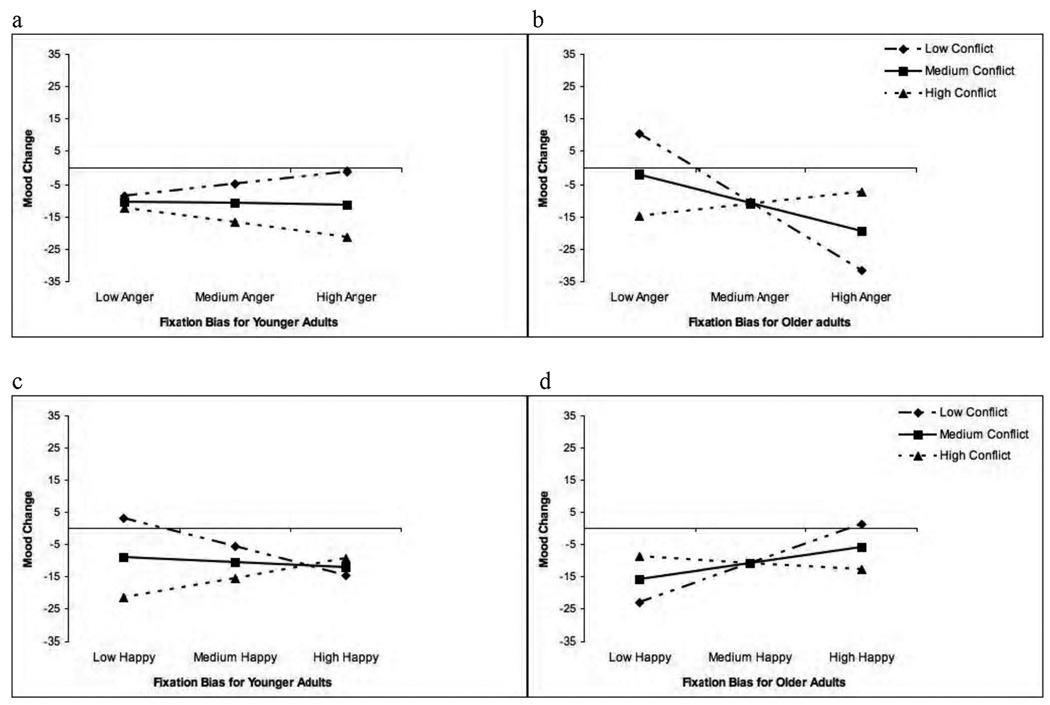

When we tried to link gaze patterns to synthetic faces to mood changes over time (comparing mood states at the start and end of the eye-tracking session), executive control emerged as a key moderator (Isaacowitz, Toner, & Neupert, 2009). Two groups of individuals showed mood stability/slight improvement during the 20+ minutes of image viewing even though most people’s moods went down: older adults with good executive control (low ANT conflict scores) best resisted mood decline utilizing a positive gaze pattern (looking toward happy and away from angry faces, see Figure 2b and 2d). In contrast, younger adults with good executive control were able to resist mood decline by displaying a more negative looking pattern (looking away from happy and toward angry faces; see Figure 2a and Figure 2c). The findings suggest that older adults with good executive control were most capable of resisting mood declines throughout the study. This further extends Mather and colleagues’ (e.g., Knight et al., 2007) argument that cognitive control is required for positivity effects to occur and suggests that the extent to which positive preferences support older adults’ mood regulation is dependent on adequate cognitive control.

Figure 2.

Interaction of Age group × Fixation × Conflict in the prediction of macrolevel mood change (posttracking mood minus pretracking mood; most scores were negative, indicating worsening mood during tracking) for (a) anger for younger adults (b) anger for older adults, (c) happy for younger adults, and (d) happy for older adults. Low conflict scores indicate better executive control. From Isaacowitz, Toner, & Neupert (2009).

Yet, these findings also raise the question of why younger adults with good executive control feel best when they look at negative materials. Supporting our earlier speculation, it appears that while older adults are more likely to implement a diensgagement strategy to downregulate negative emotions, younger adults prefer to use an ensgagement strategy to regulate how they feel; however, the extent to which these preferential gaze has positive mood outcomes appeared to depend on adequate control abiltiy. Thus, the fact that younger adults with high cognitive control, in particular, display a relatively negative gaze pattern while regulating their mood suggests that younger adults’ gaze patterns may not simply reflect mood-congruency.

In a more recent study (Noh, Lohani, & Isaacowitz, in press), we further tested age differences in the use of gaze to regulate mood by creating a context in which participants were explicitly instructed to regulate how they feel (“try to manage the emotions you feel while looking at the images”) as they viewed highly arousing negative images from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS; Lang, Bradley, & Cuthbert, 1999). This is opposed to the previous studies which showed synthetic emotional faces and instructed participants to “watch naturally.” By providing explicit emotion regulation instructions and using only negative visual stimuli that are quite emotionally evocative, we could test whether the participants actually were motivated to make attempts to regulate their mood in a case where the stimuli themselves, rather than a mood induction or a boring situation, elicited an affective response. Because all the images were negatively-valenced, fixation toward and away from the most negative areas of the images was recorded with eye tracking. Moreover, unlike the previous studies linking overall mood change and between-group differences in gaze patterns, this study evaluated change in gaze patterns at a smaller time interval (approximately 1 minute) within individuals and assessed how within-person changes in fixations predicted mood change over time. Using multi-level models, we also assessed moment-to-moment change in gaze patterns within individuals (i.e., increase or decrease in gaze toward the most negative regions relative to their average tendency) as they attempted to regulate their mood.

There were effects of time: mood declined as the images were presented, perhaps as the affective impact of the disturbing images accumulated. Within-person changes in fixation predicted change in mood over time, though it depended on age and attentional functioning; however, in this study, the alerting network of attention emerged as the key moderator. Among older adults, the level of fixation when alerting ability is high was shown to be more important than when alerting ability is low. That is, older adults with high alerting ability experienced a lesser mood decline at the end of the session when they showed more positive gaze patterns than their average tendency (in other words, looking relatively less at the negative images) compared to when they showed more negative looking patterns. Older adults with worse alerting ability showed a weaker association between positive gaze and mood change. In contrast, young adults felt slightly better when they looked more at the negative images compared to their own average, though this effect dissipated over time. Alerting did not moderate this effect in young adults.

While much previous research has linked executive control with emotion regulation (see also Zelazo & Cunningham, 2007), it is interesting that the alerting network is also an important attentional substrate in the context of older adults’ use of gaze patterns for emotion regulation when they have to regulate mood while viewing highly disturbing images. Why does good alerting ability facilitate successful use of gaze in regulating mood, especially for older adults? One suggestion comes from research on emotion-cognition links finding that self-reported negative affect correlates with alerting performance in the lab (Compton, Wirtz, Pajoumand, Claus, & Heller, 2004); this may also apply to the context of viewing disturbing images, as they negatively impact mood states which in turn heightens the system’s alertness. This is further supported by a recent study (MacLeod, Lawrence, McConnell, Eskes, & Klein, 2010), examining the reliabilities of the ANT networks, suggesting that executive control network may reflect a trait-like form of attention (low within-subject, but high between-subject variances), whereas both alerting and orienting networks may reflect a state-like form of attention (high within-subject, but low between-subject variances). Good alerting ability may indicate the perceiver’s sensitivity (increased speed) to external cues to sustain a vigilant state (Fan et al., 2002) and there is some evidence that older adults may rely more on external cues than younger adults (Spieler, Mayr, & LaGrone, 2006). Thus, older adults who can display good alerting ability may be those who are especially reliant on external cues in order to be alert allowing them to detect emotionally meaningful signals (in this case, the most negative, highly arousing parts of the images). Using a disengagement approach by looking away from the most disturbing parts of the images especially may therefore benefit older adults with good alerting ability.

Findings from these two studies specifically investigating links between looking and feeling in younger and older adults suggests that positive gaze preferences are helpful in terms of mood regulation for older adults with good attentional functioning, especially those high in executive control and alerting. Positive gaze preferences may also help those older adults with lower levels of attentional functioning, but not to the same degree. Younger adults seem to benefit from looking more at negative stimuli. A tentative conclusion is that positive looking, including visual disengagement from negative stimuli, is a key regulatory strategy used by older adults, with positive outcomes especially for those with good attentional functioning. For younger adults, engaging visually with negative stimuli may help them to regulate how they feel, suggesting that they are relying on emotion regulation strategies other than attentional deployment, perhaps cognitive reappraisal.

Age Differences in Visual Engagement and Disengagement in Emotion Regulation: Caveats, Constraints, and Implications

We believe that these findings support a perspective in which older adults may be more likely than younger adults to benefit from strategies of (visual) disengagement from negative stimuli, whereas younger adults may be more likely than older adults to benefit from strategies of engagement with negative stimuli; nonetheless, there are some important caveats to this assertion. Only based on a small number of studies and findings, it needs to be replicated and expanded in future studies. The overall pattern is complex and depends on attentional moderators; while this may reflect the complexity of real-time mood change, as well as the natural variability of moods across and within age groups, it makes testing these links difficult and findings often confusing. Moreover, the idea that younger adults may benefit from engaging visually with negative stimuli because it supports their attempts to use reappraisal as a regulatory strategy is purely speculative at this point and needs to be specifically tested in future research. The safest claim is that looking – at least positive looking – does not appear to be a key ingredient in younger adults’ mood regulation in these lab paradigms.

This raises a question of where these age-related gaze preferences come from, and how gaze patterns change over time. Life-span developmental theory proposed that training studies can suggest plausible developmental pathways (Baltes et al., 1987); therefore, we examined whether age-related positive gaze preferences could be shifted through training. Younger and older adults were trained to look at either more positive words or more negative words in emotional-neutral word pairs using a dot-probe training (Isaacowitz & Choi, 2011). Participants viewed highly negatively-valenced images before and after the training session and training effects were assessed by comparing the change in gaze patterns from before to after training. The effects of training on gaze patterns and mood differed by age group. Interestingly, older adults were more responsive to the positive training which led a greater drop in fixation to the most negative areas of the images after the training, whereas younger adults were more responsive to the negative training. Younger adults looked more at the negative images before and after training. In terms of mood change as a function of training, younger adults’ moods were not influenced by any type of training, but older adults in the negative training group showed the worst moods after training. These findings suggest only limited plasticity of age-related gaze preferences, and that negative gaze training may not be optimal for older adults’ moods. This sets the stage for future work to more specifically investigate whether experience and/or neural changes with age could lead to this profile of behavioral response and flexibility.

A potential implication of the age-related dissociation of links between looking and feeling is that older adults may be more likely to fail to attend to negative, but potentially important information in their environment. While there is evidence from studies of rapid attentional detection that older adults can detect negative emotional stimuli similarly to young adults (e.g., Leclerc & Kensinger, 2008), findings that older adults show lessened sustained attention to such negative images, and that it may be adaptive for them emotionally to do so, raise the possibility that they may miss stimuli that are negative but important. This may lead older adults to ignore certain health messages. However, it also is possible that older adults have a strategy to efficiently extract useful information from a stream of negatively-valenced material without thoroughly engaging with it. We are currently investigating this issue.

The work described above suggests that there are age differences in important components of emotion/mood regulation, and in particular how attention is used as a regulatory strategy. Emotion regulation is available to individuals regardless of age, though there may be some cases in which older adults show more rapid (Larcom & Isaacowitz, 2009) or more efficient (Scheibe & Blanchard-Fields, 2009) emotion regulation. Nonetheless, with a broad enough time-window, some individuals of any age are likely able to successfully regulate how they feel. Evaluating regulation at one point in time, or with only one possible regulatory strategy, may reveal age differences in processes but does not necessarily translate to age differences, ultimately, in downstream outcomes. The work reviewed in this article suggests that there may be age-related preferences in preferred regulatory strategies such that the behaviors associated with successful regulation for one group are opposite of those associated with successful regulation for another. In the case of gaze patterns, positivity seems to be best for older adults, whereas we do not find that positive gaze preferences are helpful for mood regulation in younger adults.

That said, individual differences exist within both younger and older adults that complicate the simplistic picture presented above. The key role of attentional functioning in moderating looking-feeling links, especially for older adults, has already been discussed. Beyond attention though, other important individual difference factors may be relevant. It could even be the case that some younger adults benefit from visual disengagement whereas some older adults benefit from visual engagement; in other words, individual differences may dictate that the adaptive pattern for some younger adults is the typical one for older adults, and vice versa. Future research will need to determine what individual difference factors moderate whether disengagement from negative, engagement with negative, or “average” looking is most utilized and/or most adaptive in a particular situation. Some possible guesses include education level, conscientiousness, and need for cognition: higher levels of any of these might make engagement strategies more preferred and/or more adaptive, perhaps at any age.

What are the implications of this theory and research for general social psychological research on emotion–attention links? One is that looking in a positive manner may not always be a key part of attempts at emotion regulation, even pro-hedonic ones that aim to optimize positive feeling (as opposed to instrumental emotion regulation efforts that are not focused on feeling good; see Tamir, 2009). For some people, in some contexts, regulating to (relatively more) positive feeling states may not involve preferential looking at positive material in the environment, and may even entail engagement with negative: this appears to be especially true for younger individuals. A second, related implication is that most preferred and most adaptive modes of emotion and/or mood regulation may vary by age, as well as other person-level factors. Another implication is that, in any context, there may be individuals (of any age) who do not successfully regulate themselves out of negative mood states: variability of mood, and regulatory success, is present at every age. This work also has implications for attempts to improve the regulation of those with suboptimal levels: younger adults may respond to engaging with negative emotions and “working through” them, whereas older adults may be helped more by orienting more toward positive material and avoiding the negative. Relatedly, persuasive messages may need to target the particular engagement/disengagement tendencies of different age groups, both in terms of affective as well as behavioral outcomes. Age may not only make a difference in general cognition–emotion links, it also appears to impact cognition–emotion regulation links as well.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 AG026323 to Derek M. Isaacowitz. Thanks to Monika Lohani for her help in preparing this manuscript. We would also like to thank Mary Jo Larcom for her valuable comments on the manuscript.

References

- Allard ES, Isaacowitz DM. Are preferences in emotional processing affected by distraction? Examining the age-related positivity effect in visual fixation within a dual-task paradigm. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. 2008;15:725–743. doi: 10.1080/13825580802348562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allard ES, Wadlinger HA, Isaacowitz DM. Positive gaze preferences in older adults: Assessing the role of cognitive effort with pupil dilation. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. 2010;17:296–311. doi: 10.1080/13825580903265681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB. Theoretical propositions of life-span developmental psychology: On the dynamics between growth and decline. Developmental Psychology. 1987;23:611–626. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Isaacowitz DM, Charles ST. Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist. 1999;54:165–181. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.3.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Mikels JA. At the Intersection of Emotion and Cognition: Aging and the Positivity Effect. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14:117–121. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Pasupathi M, Mayr U, Nesselroade JR. Emotional experience in everyday life across the adult life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:644–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Turan B, Scheibe S, Ram N, Ersner-Hershfield H, Samanez-Larkin GR, Brooks KP, Nesselroade JR. Emotional experience improves with age: Evidence based on over 10 years of experience sampling. Psychology and Aging. doi: 10.1037/a0021285. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Turk-Charles S. The salience of emotion across the adult life course. Psychology and Aging. 1994;9:259–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Mather M, Carstensen LL. Aging and emotional memory: The forgettable nature of negative images for older adults. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2003;132:310–324. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.132.2.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Reynolds CA, Gatz M. Age-related differences and change in positive and negative affect over 23 years. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton RJ, Wirtz D, Pajoumand G, Claus E, Heller W. Association between positive affect and attentional shifting. Cognitive Therapy & Research. 2004;28(6):733–744. [Google Scholar]

- Fan J, McCandliss BD, Sommer T, Raz A, Posner MI. Testing the efficiency and independence of attentional networks. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2002;14:340–347. doi: 10.1162/089892902317361886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ. Antecedent- and response-focused emotion regulation: Divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:224–237. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.1.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grühn D, Smith J, Baltes PB. No aging bias favoring memory for positive material: Evidence from a heterogeneity-homogeneity list paradigm using emotionally toned words. Psychology and Aging. 2005;20:579–588. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.4.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacowitz DM. Correlates of well-being in adulthood and old age: A tale of two optimisms. Journal of Research in Personality. 2005a;39:224–244. [Google Scholar]

- Isaacowitz DM. The Gaze of the Optimist. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005b;31:407–415. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacowitz DM, Choi Y. Malleability of age-related positive gaze preferences: Training to Change Gaze and Mood. Emotion. 2011:90–100. doi: 10.1037/a0021551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacowitz DM, Toner K, Goren D, Wilson HR. Looking while unhappy: Mood-congruent gaze in young adults, positive gaze in older adults. Psychological Science. 2008;19:848–853. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02167.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacowitz DM, Toner K, Neupert SD. Use of gaze for real-time mood regulation: Effects of age and attentional functioning. Psychology and Aging. 2009;24:989–994. doi: 10.1037/a0017706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacowitz DM, Wadlinger HA, Goren D, Wilson HR. Is there an age-related positivity effect in visual attention? A comparison of two methodologies. Emotion. 2006a;6:511–516. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.6.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacowitz DM, Wadlinger HA, Goren D, Wilson HR. Selective preference in visual fixation away from negative images in old age? An eye-tracking study. Psychology and Aging. 2006b;21:40–48. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kensinger EA. Age differences in memory for arousing and nonarousing emotional words. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2008;63B:13–18. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.1.p13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kensinger EA, Schacter DL. Neural processes supporting young and older adults' emotional memories. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2008;20:1161–1173. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight M, Seymour TL, Gaunt JT, Baker C, Nesmith K, Mather M. Aging and goal-directed emotional attention: Distraction reverses emotional biases. Emotion. 2007;7:705–714. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.4.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larcom MJ, Isaacowitz DM. Rapid emotion regulation after mood induction: Age and individual differences. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2009;64B:733–741. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN. International affective picture system (lAPS): Instruction manual and affective ratings. Gainsville, FL: Center for Research in Psychophysiology. University of Florida; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Leclerc CM, Kensinger EA. Effects of age on detection of emotional information. Psychology and Aging. 2008;23:209–215. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.23.1.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Isaacowitz DM. How optimists face skin cancer information: Risk assessment, attention, memory, and behavior. Psychology & Health. 2007;22:963–984. [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod JW, Lawrence MA, McConnell MM, Eskes GA, Klein RM. Appraising the ANT: Psychometric and theoretical considerations of the attention network test. Neuropsychology. 2010;24:637–651. doi: 10.1037/a0019803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manor BR, Gordon E. Defining the temporal threshold for ocular fixation in free-viewing visuocognitive tasks. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2003;128:85–93. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(03)00151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Carstensen LL. Aging and motivated cognition: The positivity effect in attention and memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2005;9:496–502. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Knight M. Goal-Directed Memory: The Role of Cognitive Control in Older Adults' Emotional Memory. Psychology and Aging. 2005;20:554–570. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.4.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikels JA, Larkin GR, Reuter-Lorenz PA, Carstensen LL. Divergent trajectories in the aging mind: Changes in working memory for affective versus visual information with age. Psychology and Aging. 2005;20:542–553. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.4.542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh SR, Lohani M, Isaacowitz DM. Deliberate real-time mood regulation in adulthood: The importance of age, fixation, and attentional functioning. Cognition and Emotion. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2010.541668. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opitz PC, Rauch LC, Terry DP, Urry HA. Prefrontal mediation of age differences in cognitive reappraisal. Neurobiology of Aging. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.06.004. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrican R, Moscovitch M, Schimmack U. Cognitive resources, valence, and memory retrieval of emotional events in older adults. Psychology and Aging. 2008;23:585–594. doi: 10.1037/a0013176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI, Petersen SE. The attention system of the human brain. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1990;13:25–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.13.030190.000325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner K. Eye movements in reading and information processing: 20 years of research. Psychological Bulletin. 1998;85:618–660. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.124.3.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner K, Miller B, Rotello CM. Eye movements when looking at print advertisement: The goal of the viewer matters. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2008;22:697–707. doi: 10.1002/acp.1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riediger M, Schmiedek F, Wagner GG, Lindenberger U. Seeking pleasure and seeking pain: Differences in prohedonic and contra-hedonic motivation from adolescence to old age. Psychological Science. 2009;20:1529–1535. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. The processing-speed theory of adult age differences in cognition. Psychological Review. 1996;103(3):403–428. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.103.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheibe S, Blanchard-Fields F. Effects of regulating emotions on cognitive performance: What is costly for young adults is not so costly for older adults. Psychology and Aging. 2009;24:217–223. doi: 10.1037/a0013807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppes G, Catran E, Meiran N. Reappraisal (but not distraction) is going to make you sweat: Physiological evidence for self-control effort. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2009;71:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppes G, Meiran N. Divergent cognitive costs for online forms of reappraisal and distraction. Emotion. 2008;8:870–874. doi: 10.1037/a0013711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiota M, Levenson R. Effects of aging on experimentally instructed detached reappraisal, positive reappraisal, and emotional behavior suppression. Psychology and Aging. 2009;24:890–900. doi: 10.1037/a0017896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaniol J, Voss A, Grady CL. Aging and emotional memory: Cognitive mechanisms underlying the positivity effect. Psychology and Aging. 2008;23:859–872. doi: 10.1037/a0014218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spieler DH, Mayr U, LaGrone S. Outsourcing cognitive control to the environment: Adult age differences in the use of task cues. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2006;13:787–793. doi: 10.3758/bf03193998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley JT, Isaacowitz DM. Age-related differences in profiles of mood-change trajectories. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:318–330. doi: 10.1037/a0021023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamir M. What do people want to feel and why?: Pleasure and utility in emotion regulation. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2009;18:101–105. [Google Scholar]

- Urry HL. Seeing, thinking, and feeling: Emotion-regulating effects of gaze-directed cognitive reappraisal. Emotion. 2010;10:125–135. doi: 10.1037/a0017434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urry HL, Gross JJ. Emotion regulation in older age. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2010;19:352–357. [Google Scholar]

- van Reekum CM, Johnstone T, Urry HL, Thurow ME, Schaefer HS, Alexander AL, et al. Gaze fixations predict brain activation during the voluntary regulation of picture-induced negative affect. NeuroImage. 2007;36:1041–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winecoff A, LaBar KS, Madden DJ, Cabeza R, Huettel SA. Cognitive and neural contributors to emotion regulation in aging. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq030. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelazo PD, Cunningham W. Executive function: Mechanisms underlying emotion regulation. In: Gross J, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York: Guilford; 2007. pp. 135–158. [Google Scholar]

- Xing C, Isaacowitz DM. Aiming at happiness: How motivation affects attention and memory for emotional images. Motivation and Emotion. 2006;30:249–256. [Google Scholar]