Abstract

Physical activity (PA) is critical for maximizing bone development during growth. However, there is no consensus on how well existing PA measurement tools predict bone strength.

PURPOSE

Compare four methods of quantifying physical activity (PA) (pedometer, 3-day physical activity recall (3DPAR), bone-specific physical activity questionnaire (BPAQ), and past year physical activity questionnaire (PYPAQ)), in young girls and evaluate their ability to predict indices of bone strength.

METHODS

329 girls aged 8–13 years completed a pedometer assessment, the 3DPAR, the BPAQ, and a modified PYPAQ. Peripheral quantitative computed tomography (pQCT) was used to assess bone strength index (BSI) at metaphyseal (4% distal femur and tibia) sites and strength-strain index (SSI) at diaphyseal (femur = 20%, tibia = 66%) sites of the non-dominant leg. Correlations and hierarchical multiple regression were used to assess relationships among PA measures and indices of bone strength.

RESULTS

After adjustment for maturity, correlations between PA measures and indices of bone strength were positive, although low (r = 0.01–0.20). Regression models that included covariates (maturity, body mass, leg length, and ethnicity) and PA variables showed that PYPAQ score was significantly (P < 0.05) associated with BSI and SSI at all sites and explained more variance in BSI and SSI than any other PA measure. Pedometer steps were significantly (P < 0.05) associated with metaphyseal femur and tibia BSI and 3DPAR score was significantly (P < 0.05) associated with metaphyseal femur BSI. BPAQ score was not significantly (P > 0.05) associated with BSI or SSI at any sites.

CONCLUSION

A modified PYPAQ that accounts for the duration, frequency, and load of PA predicted indices of bone strength better than other PA measures.

Keywords: BONE GEOMETRY, EXERCISE, FEMALE, PQCT, YOUTH

Introduction

Activity type and dose are critical factors underlying the osteogenic effect of physical activity (PA). As emphasized in the most recent American College of Sports Medicine position stand on PA and bone health (14), activities that involve high strain magnitudes (10) and greater loading frequencies (8) are most effective for optimizing the osteogenic response during growth, which is the most opportune time to modify bone mass and geometry (32). However, despite the well known favorable effects of certain types of PA on bone, few studies have tested the ability of existing PA measurement tools to predict bone strength in youth. Moreover, whether standardized methods that quantify the loading component of PA predict bone strength better than other methods remains unclear.

Recently, the bone-specific physical activity questionnaire (BPAQ) was developed by Weeks and Beck (41) to record both current and historical PA. Load values based on ground reaction forces (GRFs) associated with common sports and activities were incorporated into BPAQ algorithms to increase the contribution of high-impact activities to the overall score. The algorithms also weighed factors such as age and weekly frequency of PA participation. The current (past 12 months) component of the BPAQ was shown to predict femoral neck, lumbar spine, and whole body areal bone mineral density (aBMD, g/cm2) measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) in men, but not in women, while the historical component predicted calcaneal broadband ultrasound attenuation (BUA) in women (41). In contrast, other measures of PA such as the bone loading history questionnaire (BLHQ) (6), the Bouchard 3-day activity record (3DR) (5), the modifiable activity questionnaire (MAQ) (18), and pedometer steps were not predictive of aBMD and BUA (41). One limitation of the BPAQ algorithms is that they were developed and tested in a small sample (n = 40) of adults, and therefore, may not predict bone parameters in other populations (e.g., children and adolescents). Another limitation of the BPAQ algorithms is that they were developed using DXA and BUA, which do not assess bone geometry. Measures of bone geometry are crucial because small changes in the shape of bone (e.g. an increase in the outer circumference) can dramatically increase its strength (33). Lastly, although the historical component of the BPAQ accounts for the duration of years of training, the current component (past 12 months) does not account for the average duration of minutes per training session. While increasing the years of training history is known to be osteogenic (13, 15), we found only one study that addressed the osteogenic effect of increasing the duration of a typical training session (31). One reason this question has received insufficient attention may be because studies in animals have shown that the osteogenic response to loading saturates relatively quickly (30, 39). Based on these studies, prolonging the duration of a single training session is less likely to be osteogenic. However, animal studies have also shown that increased duration (e.g., increased number of loading cycles) can continue to stimulate bone formation as long as the distribution of strain is altered throughout the loading session (20), which is predominately the case during most activities in free-living humans. Thus, increasing the duration of the average training session may be an important osteogenic stimulus that has been overlooked.

The past year physical activity questionnaire (PYPAQ) is a validated questionnaire (2) which can be used to survey sport and leisure-time PA. Shedd et al. (34) used a modified version of the PYPAQ to assess PA in postmenopausal women and developed a bone-relevant PYPAQ algorithm that incorporates PA duration (defined as average minutes/session), frequency (sessions/week), and load (peak strain score (9)). The PYPAQ algorithm predicted volumetric bone mineral density (vBMD) and geometry assessed by peripheral quantitative computed tomography (pQCT) in postmenopausal women (34). However, the ability of the PYPAQ algorithm to predict bone parameters of children and adolescents has not been studied.

Given the need to quantify PA type and dose in studies of the effects of PA on bone, we sought to compare the ability of the BPAQ and the modified PYPAQ along with other common measures of PA in youth (3-day physical activity recall (3DPAR) (26) and pedometer) to predict bone strength in girls after controlling for important covariates known to influence bone parameters during growth. We hypothesized that PA assessment tools that account for bone loading (i.e. BPAQ and modified PYPAQ) would predict bone strength better than common PA measures (i.e. 3DPAR and pedometer) that give more global estimates of PA. Furthermore, we hypothesized that of the two PA measures that account for bone loading, the modified PYPAQ would be a better predictor of bone strength than the BPAQ because it accounts for duration in addition to the frequency and load of each activity reported.

Methods

Participants

The sample included 329 healthy girls, aged 8–13 years, who were participants in the “Jump-In: Building Better Bones” study. The long-term goal of the Jump-In study is to prospectively assess the effects of high-impact jumping exercises on bone macro-architecture in prepubescent and early pubescent girls. Girls who were in school grade 4 or 6 were recruited from 14 elementary and 4 middle schools around Tucson, Arizona. Exclusion criteria included learning disabilities (identified by schools) that made it impossible to complete questionnaires or otherwise unable to comply with assessment protocols; medications, medical conditions, or a disability that limited participation in physical exercise as defined by the Committee on Sports Medicine and Fitness (1); excluded (or excused) from participation in physical education; and the inability to read and understand English. The protocol was approved by the University of Arizona Human Subjects Protection Committee and the study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. All guardians and participating girls provided written informed consent. After informed consent, guardians completed a health history questionnaire with questions on participant ethnicity and race.

Anthropometry

Anthropometric measures were obtained following standardized protocols (22). Body mass was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a calibrated scale (Seca, Model 881, Hamburg, Germany) and height and sitting height were measured at full inhalation to the nearest mm using a stadiometer (Shorr Height Measuring Board, Olney, MD). Non-dominant femur length (nearest mm) was measured from the base of the patella to the inguinal crease. Non-dominant tibia length (nearest mm) was measured from the proximal end of the medial border of the tibial plateau to the distal edge of the medial malleolus. Coefficients of variation (CVs) for femur and tibia lengths were 0.38% and 0.13%, respectively (n = 329). For each anthropometric variable, the mean of two measurements was taken. The two measurements were repeated if the first two trials differed by more than 4 mm for height, sitting height and bone lengths, and 0.3 kg for body mass. If repeat measures were required, the mean of the second set of measures was used in the analyses.

Physical Maturation

Assessment of maturity is necessary in studies of growing children because the range in maturation between individuals of the same chronological age is large, especially during the pubertal years (24). In “Jump-In”, maturity was assessed in two ways. The first method relied on a self-report (with assistance available) questionnaire that presents illustrations of female pubertal development stages (Tanner stages). Girls rated their Tanner stage based on breast development and reported their menarcheal status using the validated questionnaire (25) that has been shown to agree well with physician exam and grading. Although Tanner staging is common in developmental studies, its ability to accurately assess maturation may be limited (35). Consequently, maturation was also assessed using the method of Mirwald et al., (24) who developed gender-specific algorithms to predict years from peak height velocity (PHV) based on data from a six-year longitudinal study in boys and girls (3). These algorithms incorporate interactions between height, weight, sitting height, leg length, and chronological age to derive a maturity offset value. The following equation from Mirwald et al. (24) was used to estimate maturity offset in our sample of females: Maturity Offset = −9.376 + 0.0001882·Leg Length and Sitting Height interaction + 0.0022·Age and Leg Length interaction + 0.005841·Age and Sitting Height interaction − 0.002658·Age and Weight interaction + 0.07693·Weight by Height ratio. In Mirwald’s sample, this equation explained 89% of the variance in years from PHV in girls (24).

Physical Activity Assessment

Pedometer

After laboratory testing, subjects were instructed to wear an Omron HJ-720ITC (Bannockburn, IL) pedometer during all waking hours, except when in water, for the following 7 contiguous days. The validity and reliability of this pedometer has been tested under prescribed and self-paced walking conditions (11). The pedometer features a dual piezoelectric sensor that detects vertical and horizontal movements. The pedometer also offers PC downloading capabilities, 41-day storable memory, automatically resets at midnight, and displays and stores total daily steps and aerobic (higher intensity) steps. Aerobic steps are defined as times during which a subject walks more than 60 steps per minute for more than 10 minutes continuously. Subjects were instructed to wear the pedometer on their waistband at the right hip because this site was recommended by the manufacturer, it does not interfere with daily activities, and is the most frequently used site in epidemiological studies.

3-Day Physical Activity Recall (3DPAR) questionnaire

The 3-day physical activity recall (3DPAR) questionnaire has been validated in girls (26) and has been used previously to quantify PA in youth (23). For every 30-minute time block (34 blocks/day, 17 hours/day) for the previous 3 days, participants reported the predominant PA and the intensity level (light, moderate, hard, or very hard) at which they performed the activity. To assist the respondent, the questionnaire includes a script and graphics to explain the intensity of common activities. Metabolic equivalents (MET, where 1 MET = 3.5 mL × kg−1 × min−1) were obtained from the Compendium of Energy Expenditures for youth (27). Average daily MET adjusted minutes of PA were computed over each of the 3 previous days using the following algorithm: 3DPAR average daily MET adjusted minutes = (∑ n =1–3 (∑ k =1–34 (30 minute block × MET value)))/n, where n = the number of days and k = the number of 30 minute blocks per day. Pate et al. (26) reported that the 3DPAR was significantly, and moderately correlated with MTI (Manufacturing Technologies, Inc., Shalimar, FL) Actigraph counts (r = 0.28–0.46).

Bone-specific Physical Activity Questionnaire (BPAQ)

The bone-specific physical activity questionnaire (BPAQ) has been described in detail previously (41). In brief, the BPAQ is a self-administered account of current (past 12 months) and historical (years) PA for which respondents record the type and weekly frequency of usual PA and sport participation. The current BPAQ score was calculated for each girl using an algorithm developed to weigh weekly frequency of activity participation and load intensity based on GRFs in adult men (n = 20) and women (n = 20). The following algorithm was used to calculate current BPAQ score: Current BPAQ (cBPAQ) score = [(R + 0.2 × R × (n−1)) × a], where R = effective load stimulus (derived from GRF testing), n = frequency of participation (per week), and a = age weighting factor (< 10 yrs = 1.2; 10–15 yrs = 1.5; 15–35 yrs = 1.1; > 35 yrs = 1.0) (41).

Past Year Physical Activity Questionnaire (PYPAQ)

The past year physical activity questionnaire (PYPAQ) has been validated in adolescents (2). We modified the questionnaire to include a more comprehensive list of 41 activities common to youth. Specifically, the modified PYPAQ was used to survey all sport and leisure-time physical activity in which subjects had engaged at least 10 times in the past year outside of physical education class. The questionnaire was administered in an interview with the subject and guardian(s). Participants were asked to record the average duration, weekly frequency, and the number of months of participation for each activity. Total PYPAQ score was computed using a modified algorithm from Shedd et al. (34): PYPAQ score = ∑1−n (duration (average minutes/session) × frequency ([months/12] × days/week) × load (peak strain score)), where n was the number of activities a subject reported during the past year. Peak strain scores (PSS) reported by Groothausen et al. (9) were used to increase the contribution of bone-relevant loading activities to the overall score. Jumping activities (e.g., basketball, gymnastics, volleyball) were assigned a PSS of 3; activities that involve changing directions quickly and sprinting (e.g., soccer, tennis) were assigned a PSS of 2; all other weight-bearing activities were assigned a PSS of 1. Low-impact activities that fell between categories were given a PSS of 1.5. Non-weight-bearing physical activities (e.g. swimming, cycling) were assigned a PSS of 0.5. Sports and leisure-time activities that did not have a PSS previously reported in the literature were assigned the same value as the most similar activity.

Bone measurements

Bone geometry and vBMD were assessed at the distal 4% and 20% femur and 66% tibia sites of the non-dominant leg using pQCT (XCT 3000; STRATEC Medizintechnik GmbH, Pforzheim, Germany, Division of Orthometrix; White Plains, NY). Scout scans were performed to locate the distal growth plate of the femur and tibia, with the scanner programmed to subsequently find the sites of interest. pQCT scans were analyzed using Stratec software, Version 5.50. Further details on image processing, calculations (e.g., bone strength indices), and analysis, including descriptions of Contour, Peel, and Cort modes can be found in the operator’s manual (Stratec Medizintechnik XCT 3000 manual, Pforzheim, Germany). At the 4% distal femur and tibia, we used Contour mode 3 at 169 mg/cm3 to define the total bone. Because of the difficulties in interpreting metaphyseal bone density measurements from a single slice (21), we averaged 3 pQCT slices at both the femur and tibia 4% sites. At the 20% femur and 66% tibia sites, Contour mode 1 at 710 mg/cm3 was used to measure total bone and Cort mode 2 at 710 mg/cm3 was used for cortical bone analysis. Peel mode 2 at 710 mg/cm3 was used to define the marrow area. Slice thicknesses were 2.2 mm and voxel sizes were set at 0.4 mm for all sites. Scanner speed was set at 30 mm/second. Bone strength index (BSI, mg2/mm4), calculated as described by Kontulainen (16), was assessed at the 4% femur and tibia sites, while strength-strain index (SSI, mm3), calculated as described by Shedd (34), was assessed at the 20% femur and 66% tibia. BSI estimates the bone’s ability to withstand compression at metaphyseal sites, while SSI is used to estimate the bone’s ability to resist torsion and bending forces at diaphyseal sites.

Calibration and quality assurance of the pQCT instrument was performed daily to ensure the accuracy and precision of measurements. Technicians were trained on pQCT scanning and software analyses following guidelines provided by Bone Diagnostics, Inc. (Fort Atkinson, WI). One operator performed all pQCT scans and one technician performed all scan analyses. Repeat scanning of young girls to establish the precision of pQCT was not considered ethical by the University of Arizona Human Subjects Protection Committee. Thus, we conducted a separate study with adults to determine within-subject pQCT precision error (coefficient of variation: CV). Subjects were repositioned between scans. CVs calculated as described by Binkley (4) for BSI at the 4% femur and tibia were 0.94% and 0.78%, respectively (n=29 per skeletal site), while CVs for SSI at the 20% femur and 66% tibia were 0.88% and 0.92%, respectively (n=29 per skeletal site).

Statistical Analysis

Data were checked for outliers and normality using histograms and all variables were tested for skewness and kurtosis. BSI and SSI at all sites were modestly skewed. We ran both log transformed and untransformed analyses; all results were similar, thus, we report the untransformed data for clarity. To identify relationships among PA measures and between PA measures and indices of bone strength (BSI, SSI), bivariate correlations were computed using Pearson’s r for continuous variables. Partial correlations (adjusted for maturity offset) were also used to quantify relationships between PA measures and indices of bone strength. Finally, hierarchical multiple regression models were constructed with indices of bone strength (BSI and SSI) as dependent variables. Adjusted R2 values were computed for each base model which included maturity offset, body mass, leg length, and ethnicity as covariates. Subsequently, each PA variable was added separately to the base model and the change in the adjusted R2 value was computed. We repeated all regression analyses substituting maturity offset with Tanner stage. All results were similar, thus, we only report analyses that included maturity offset based on its greater association with indices of bone strength in this sample (7). Regression models were also ran within maturity offset and Tanner stage maturity categories (maturity offset < 0 years post PHV and ≥ 0 years post PHV; Tanner stage I (pre-pubertal), Tanner stage II–III (early pubertal, Tanner stage IV–V (late pubertal). Prior to regression analyses, all variables were checked for normality, linearity, and homoscedasticity using residual plots. Colinearity among covariates was tested in each regression model and was not observed in any of the final models. All analyses were performed using The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows, Version 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Sample descriptive characteristics are shown in Table 1. Sample ethnicity and race were 22% Hispanic and 78% non-Hispanic, 87% white, 8% Asian, 3% black or African American, 1% Native American or Alaska Native, 0.5% Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, and 0.5% other. Based on U.S. National Center for Health Statistics/Center for Disease Control percentiles for body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) (19), 3.6% of the sample was underweight (BMI <5th percentile), 75.4% of the sample was healthy weight (BMI 5th–85th percentile), 13.1% of the sample was at-risk for overweight (BMI 85th–95th percentile), and 7.9% of the sample was overweight (BMI >95th percentile). Of the 329 girls, 17 (5%) achieved the Tudor-Locke et al. (38) recommendation of 12,000 steps per day for girls aged 6–12 years old.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive characteristics (n = 329).

| Charactertistics | Mean ± SD | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 10.7 ± 1.1 | 8.8 – 13.2 |

| Tanner stage (1–5) | 2.1 ± 1.0 | 1.0 – 4.0 |

| Maturity offset (yr) | −1.1 ± 1.1 | −3.2 – 1.2 |

| Body mass (kg) | 39.2 ± 10.4 | 22.1 – 77.2 |

| Height (cm) | 144.8 ± 9.9 | 120.3 – 171.6 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 18.4 ± 3.3 | 13.0 – 32.1 |

| Leg length (cm) | 69.0 ± 5.8 | 45.3 – 86.9 |

| Femur length (cm) | 34.2 ± 3.0 | 24.4 – 43.1 |

| Tibia length (cm) | 33.2 ± 2.9 | 25.5 – 40.7 |

| pQCT | ||

| Femur 4% BSI (mg2/mm4) | 96.2 ± 28.4 | 42.0 – 215.6 |

| Femur 20% SSI (mm3) | 1352 ± 402 | 565 – 2631 |

| Tibia 4% BSI (mg2/mm4) | 51.7 ± 14.4 | 23.5 – 106.8 |

| Tibia 66% SSI (mm3) | 1181 ± 338 | 497 – 2225 |

| Physical Activity | ||

| 3DPAR score | 1964 ± 369 | 828 – 3709 |

| Daily total steps | 8492 ± 2237 | 3603 – 16579 |

| Daily aerobic steps | 430 ± 585 | 0 – 3531 |

| BPAQ score | 115.3 ± 110.6 | 0.1 – 573.7 |

| PYPAQ score | 919.3 ± 1020.2 | 12.5 – 9385.0 |

BMI = body mass index; pQCT = peripheral quantitative computed tomography; BSI = bone strength index; SSI = strength-strain index; 3DPAR = 3-day physical activity recall; BPAQ = bone-specific physical activity questionnaire; PYPAQ = past year physical activity questionnaire.

Bivariate correlations (Pearson’s r) among PA measures (3DPAR score, total steps, aerobic steps, BPAQ score, PYPAQ score) were all positive. Significant, moderate correlations were found between average daily total steps and aerobic steps (P < 0.001, r = 0.47) and between BPAQ score and PYPAQ score (P < 0.001, r = 0.52). 3DPAR score and PYPAQ score were significantly, although weakly, correlated (P < 0.01, r = 0.20). All other correlations among PA measures were not significant (P > 0.05). Unadjusted bivariate correlations (Pearson’s r) between PA measures and indices of bone strength (BSI, SSI) were r = 0.05–0.10 for the 3DPAR, r = −0.12–0.00 for total steps, r = 0.01–0.10 for aerobic steps, r = 0.07–0.11 for the BPAQ, and r = 0.19–0.26 for the PYPAQ across all skeletal sites. Partial correlation coefficients (adjusted for maturity offset) between PA measures and indices of bone strength (BSI, SSI) at metaphyseal and diaphyseal sites of the femur and tibia are shown in Table 2. After adjustment for maturity, all PA measures were positively correlated with indices of bone strength, although correlations were low (r = 0.01–0.20). 3DPAR score was significantly (P < 0.05) correlated with metaphyseal femur BSI (r = 0.12), while average daily total pedometer steps were significantly (P < 0.05) correlated with metaphyseal femur and tibia BSI (r = 0.13). Significant (P < 0.05) correlations were consistently observed across skeletal sites between PYPAQ score and BSI at metaphyseal sites and SSI at diaphyseal sites of the femur and tibia (r = 0.11–0.20).

TABLE 2.

Partial correlation coefficients estimating associations between physical activity measures and bone strength outcomes (n = 329).

| 3DPAR score |

Total steps |

Aerobic steps |

BPAQ score |

PYPAQ score |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Femur 4% BSI (mg2/cm4) | 0.12* | 0.13* | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.11* |

| Femur 20% SSI (mm3) | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.13* |

| Tibia 4% BSI (mg2/cm4) | 0.10 | 0.13* | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.20‡ |

| Tibia 66% SSI (mm3) | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.17† |

All correlations adjusted for maturity offset. 3DPAR = 3-day physical activity recall; BPAQ = bone-specific physical activity questionnaire; PYPAQ = past year physical activity questionnaire; BSI = bone strength index (mg2/cm4); SSI = strength-strain index (mm3).

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001.

Results from hierarchical regression analyses are presented in Table 3. 3DPAR score was significantly (P < 0.05) associated with metaphyseal femur BSI, but was not associated (P > 0.05) with any other bone strength outcome. Average daily total steps were significantly (P < 0.01) associated with femur and tibia BSI at metaphyseal sites, but were not associated (P > 0.05) with SSI at diaphyseal sites of the femur and tibia. Average daily aerobic steps were significantly (P < 0.05) associated with diaphyseal femur SSI and metaphyseal tibia BSI. BPAQ score was not significantly (P > 0.05) associated with any indices of bone strength. In contrast to the 3DPAR, average steps, and the BPAQ, PYPAQ score was significantly (P < 0.05) associated with all indices of bone strength at all sites. Adjusted R2 values for the base regression models (covariates: maturity offset, body mass, leg length, and ethnicity) ranged from 0.418–0.474 for BSI at metaphyseal sites and 0.731–0.781 for SSI at diaphyseal sites of the femur and tibia (Table 3). Comparisons of adjusted R2 change values showed that the average increase in the adjusted R2 across all skeletal sites was 0.014 for the PYPAQ, 0.007 for total steps, 0.005 for aerobic steps, 0.005 for the 3DPAR, and 0.002 for the BPAQ (Table 3). Standardized (β) regression coefficients were, on average, greater for the PYPAQ than the other PA quantifying tools (Table 3). Together, the changes in adjusted R2 and the standardized β’s demonstrate that PYPAQ score was a stronger predictor of indices of bone strength than the other PA quantifying tools. Analyses within maturity categories (maturity offset < 0 years from PHV (PRE) and ≥ 0 years from PHV (POST); Tanner stage I (prepubertal), Tanner stages II–III (early pubertal), Tanner stage IV–V (late pubertal)) gave similar results and did not change the magnitude or direction of the observed relationships between PA quantifying tools and indices of bone strength.

TABLE 3.

Adjusted R2 value for the base regression model (maturity offset, body mass, leg length, and ethnicity) at each skeletal site, the standardized (β) regression coefficient for each physical activity quantifying tool within its respective full model, and the change (Δ) in adjusted R2 value when each physical activity variable was added separately to the base model.

| Base model | 3DPAR | Total steps | Aerobic steps | BPAQ | PYPAQ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | β | Δ R2 | β | Δ R2 | β | Δ R2 | β | Δ R2 | β | Δ R2 | |

| Femur 4% BSI | 0.418 | 0.094* | 0.009 | 0.117† | 0.013 | 0.081 | 0.006 | 0.018 | 0.000 | 0.093* | 0.008 |

| Femur 20% SSI | 0.781 | 0.040 | 0.002 | 0.039 | 0.001 | 0.055* | 0.003 | 0.019 | 0.000 | 0.084† | 0.007 |

| Tibia 4% BSI | 0.474 | 0.077 | 0.006 | 0.113† | 0.012 | 0.090* | 0.008 | 0.066 | 0.004 | 0.163‡ | 0.026 |

| Tibia 66% SSI | 0.731 | 0.053 | 0.003 | 0.024 | 0.001 | 0.042 | 0.002 | 0.042 | 0.002 | 0.118‡ | 0.014 |

3DPAR = 3-day physical activity recall questionnaire; BPAQ = bone-specific physical activity questionnaire; PYPAQ = past year physical activity questionnaire. BSI = bone strength index (mg2/cm4); SSI = strength-strain index (mm3).

Base regression model = maturity offset, body mass, leg length, and ethnicity.

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001.

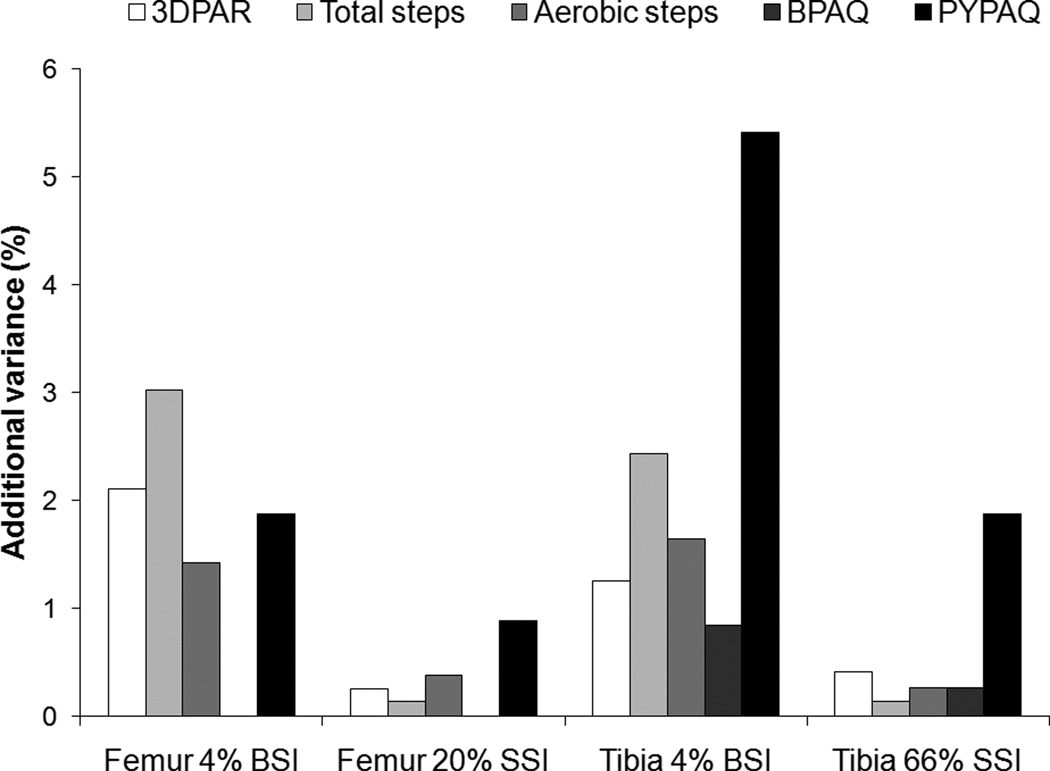

The additional variance (%) explained in indices of bone strength (BSI, SSI) after each PA quantifying tool was added separately to the base regression model (maturity, body mass, leg length, and ethnicity), is shown in Figure 1 for each skeletal site. The ranges in additional explained variance (%) in indices of bone strength when the PA variables were added to the base model were 0.3–2.1% for the 3DPAR, 0.1–3.0% for total steps, 0.3–1.6% for aerobic steps, 0.0–0.8% for the BPAQ, and 0.9–5.4% for the PYPAQ across all skeletal sites (Figure 1). The PYPAQ explained more additional variance in all indices of bone strength as compared to the other PA quantifying tools (Figure 1), with the single exception of total pedometer steps which explained an additional 3.0% of the variance in metaphyseal femur BSI while the PYPAQ explained an additional 1.9% of the variance in the same parameter (Figure 1). In contrast, the BPAQ explained the least additional variance in all bone strength outcomes as compared to the other PA quantifying tools (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The additional variance (%) explained in BSI (4% femur and tibia) and SSI (20% femur and 66% tibia) when each physical activity quantifying tool was added separately to the base regression model (maturity, body mass, leg length, and ethnicity). BSI = bone-strength index (mg2/cm4); SSI = strength strain index (mm3); 3DPAR = 3-day physical activity recall questionnaire; BPAQ = bone-specific physical activity questionnaire; PYPAQ = past year physical activity questionnaire.

Discussion

In our sample of pre- and peri-pubertal girls, a modified PYPAQ (2) was a stronger predictor of indices of bone strength (BSI and SSI) at metaphyseal and diaphyseal sites of the femur and tibia than the BPAQ (41) and common PA quantifying tools in youth (i.e., 3DPAR (26), pedometer). Overall, our findings are consistent with previous studies of PA and bone in children and adolescents that have used PA quantifying tools that account for the loading component of PA (36, 40). In contrast, the BPAQ (41) was not associated with indices of bone strength. Although measures of overall PA levels commonly used in studies of youth (3DPAR (26) and pedometer) were significant predictors of indices of bone strength, their associations were modest and site-specific. These findings are consistent with cross-sectional (17, 31, 37) and longitudinal (3, 12) studies of everyday PA and bone in youth.

Certain types of PA are critical for maximizing bone development during growth. However, it is difficult to assess the type and dose of PA best suited for optimizing bone strength with the available measurement tools. Much of our understanding of the factors that influence bone formation comes from studies of animals with surgically implanted strain gages. Studies of in vivo measurements of human bone strains during PA are rare. Thus, studies in free-living humans have been forced to rely on surrogate measures potentially related to strain. For example, motion sensors (e.g., accelerometers, pedometers) can be used to measure multi-plane acceleration and deceleration of movement, which relates to the intensity of PA. A number of studies have used motion sensors such as accelerometers and have reported that minutes of aerobic moderate- and vigorous-intensity PA relates to bone mass and aBMD in youth (12, 17, 31). However, it is still unknown how well the outputs of these devices during various intensities of PA relate to bone strain, the predominant stimulus that drives bone formation. We found that pedometer steps explained a significant, although small amount of the variance in BSI at metaphyseal sites of the femur and tibia. One explanation for the lower variance in our study as compared with other studies that have used motion sensors to measure and relate PA to bone outcomes (12, 17, 31) may be the relative lower level of activity of our sample. Only 5% of the sample achieved the Tudor-Locke et al. (38) recommendation of 12,000 steps per day for girls aged 6–12 years old.

An alternative cost-effective and potentially simpler surrogate measure of bone strain has been proposed in a number of studies (34, 40, 41), in which activities/sports are assigned peak strain scores based on GRFs reported in the literature. In our study, we incorporated a bone-loading weighting factor (peak strain score) in the PYPAQ and found that this PA measure significantly predicted pQCT indices of bone strength at various regions along the femur and tibia. Similar associations have been reported in early pubertal girls (40) and postmenopausal women (34) after increasing the contribution of high-impact activities to the overall score. In contrast, the BPAQ (41) did not predict bone strength at femur or tibia sites in our sample of pre- and peri-pubertal girls. One explanation for the failure of the BPAQ to predict femur and tibia bone strength may be because the algorithms were developed from data obtained from a small sample (n = 40) of adults and because bone outcomes were measured using DXA, which cannot provide definitive measures of bone geometry. It is possible that PA may relate differently to bone geometry compared to aBMD. Furthermore, although the BPAQ algorithm accounts for age, it does not account for sexual maturation and the influence of gonadal hormones (i.e., estrogen and testosterone), which have important consequences for bone geometry during puberty (32) and may alter the mechanosensitivity of bone cells (28). Another explanation for the inability of the BPAQ to predict bone strength in our sample of young girls is that the questionnaire does not account for seasonal changes in leisure-time PA and sport participation, which have been shown to vary greatly in youth (29). The failure to account for variation in leisure-time PA may have falsely elevated the total score of girls who engaged in certain activities for only part of the year. For example, according to the BPAQ algorithm, a respondent who participated in an activity three times weekly for 1 month during the past year would receive the same score as a respondent who participated in the same activity (3 times weekly) for the entire past year. Thus, particularly in youth, it is important to include PA measures that account for the monthly and weekly frequency of activity participation.

Our study is not without limitations. The main limitation is the difficulty assessing PA through self-report questionnaires in children and adolescents. We acknowledge that this approach is susceptible to reporting errors. In the case of the BPAQ and the PYPAQ, we attempted to minimize impact of this limitation by encouraging guardian assistance with PA recall and by limiting recall to past year PA and sport participation. Consequently, we were not able to test the ability of the historical component of the BPAQ (years of training history) to predict bone strength. In addition, GRFs associated with activities were not measured in our sample. Similar to Shedd (34) and Wang (40), for the PYPAQ, we assigned load values to activities based on GRFs (peak strain scores) reported in the literature (9). We acknowledge that these GRFs may not be representative of our sample. Another concern is that maturational differences may have influenced our study results. Although we did not directly assess skeletal age, we did assess maturation using two methods (Tanner staging and maturity offset). A potential limitation of the Tanner stage data is that it was obtained from a self-report questionnaire. Nevertheless, the questionnaire has been validated and shown to agree well with physician exam and grading of sexual maturation (25). We also assessed maturation using the method of Mirwald et al. (24), who developed gender-specific algorithms to predict years from PHV from cross-sectional data. A limitation of this method is that PHV is best captured from longitudinal somatic measurements for a number of years surrounding puberty (35). In an attempt to reconcile whether results were influenced by choosing one method over the other, we ran all analyses with Tanner stage and maturity offset separately. Results were similar, thus, we report analyses with maturity offset because its association with bone parameters was consistently higher in this sample (7). Despite its limitations, the study had several significant strengths, including the large, randomly selected study sample of pre- and peri-pubertal girls and in the use of pQCT, a technique that is appropriate for assessing vBMD and bone geometry in growing children and adolescents. Furthermore, the selection of several measurement sites at metaphyseal and diaphyseal regions of the femur and tibia provides a more detailed description of how PA measures (pedometer, 3DPAR, BPAQ, and PYPAQ) relate to weight-bearing bone strength.

Conclusions

Using pQCT in a large sample of pre- and peri-pubertal girls, our findings indicated that a modified PYPAQ that accounts for PA duration, frequency, and load was a stronger predictor of indices of bone strength (BSI, SSI) than global measures of PA commonly used in youth (3DPAR, pedometer) and the BPAQ. After controlling for important covariates known to influence bone development (maturity, body mass, leg length, ethnicity), the modified PYPAQ persisted as a significant predictor of indices of bone strength. We conclude that the modified PYPAQ is a better tool for assessing bone-relevant PA than the 3DPAR, pedometer, and the BPAQ in girls.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We appreciate the participation and support of principals, teachers, parents and students from the schools in the Catalina Foothills and Marana School Districts. We also wish to thank the radiation technicians, program coordinators, and all other members of the Jump-In Study team for their contribution. The project described was supported by Award Number HD-050775 (SG) from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. JF is supported by NIH NIGMS T32 GM-08400: Graduate Training in Systems and Integrative Physiology. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health. The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by ACSM.

Grant Support: NIH: HD050775

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: NONE

Contributor Information

Joshua N. Farr, Email: jfarr@email.arizona.edu.

Vinson R. Lee, Email: vinsonl@email.arizona.edu.

Robert M. Blew, Email: rblew@email.arizona.edu.

Timothy G. Lohman, Email: lohman@email.arizona.edu.

Scott B. Going, Email: going@email.arizona.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Academy of Pediatrics: Medical conditions affecting sports participation. Pediatrics. 2001;107(5):1205–1209. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.5.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aaron DJ, Kriska AM, Dearwater SR, et al. Reproducibility and validity of an epidemiologic questionnaire to assess past year physical activity in adolescents. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142(2):191–201. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey DA, McKay HA, Mirwald RL, Crocker PR, Faulkner RA. A six-year longitudinal study of the relationship of physical activity to bone mineral accrual in growing children: The University of Saskatchewan Bone Mineral Accrual Study. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14(10):1672–1679. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.10.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binkley TL, Berry R, Specker BL. Methods for measurement of pediatric bone. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2008;9(2):95–106. doi: 10.1007/s11154-008-9073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouchard C, Tremblay A, Leblanc C, et al. A method to assess energy expenditure in children and adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 1983;37(3):461–467. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/37.3.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dolan SH, Williams DP, Ainsworth BE, Shaw JM. Development and reproducibility of the bone loading history questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38(6):1121–1131. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000222841.96885.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farr JN, Chen Z, Lisse JR, Lohman TG, Going SB. Relationship of total body fat mass to weight-bearing bone volumetric density, geometry, and strength in young girls. Bone. 2010;46(4):977–984. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilsanz V, Wren TA, Sanchez M, et al. Low-level, high-frequency mechanical signals enhance musculoskeletal development of young women with low BMD. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(9):1464–1474. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Groothausen J, Siemer H, Kemper G, Twisk J, Welten D. Influence of peak strain on lumbar bone mineral density: an analysis of 15-year physical activity in young males and females. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 1997;9(2):159–173. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hind K, Burrows M. Weight-bearing exercise and bone mineral accrual in children and adolescents: a review of controlled trials. Bone. 2007;40(1):14–27. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holbrook EA, Barreira TV, Kang M. Validity and reliability of Omron pedometers for prescribed and self-paced walking. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(3):670–674. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181886095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janz KF, Gilmore JM, Levy SM, et al. Physical activity and femoral neck bone strength during childhood: the Iowa Bone Development Study. Bone. 2007;41(2):216–222. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karlsson MK, Magnusson H, Karlsson C, Seeman E. The duration of exercise as a regulator of bone mass. Bone. 2001;28(1):128–132. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(00)00405-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kohrt WM, Bloomfield SA, Little KD, Nelson ME, Yingling VR. American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand: physical activity and bone health. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(11):1985–1996. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000142662.21767.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kontulainen S, Sievanen H, Kannus P, Pasanen M, Vuori I. Effect of long-term impact-loading on mass, size, and estimated strength of humerus and radius of female racquet-sports players: a peripheral quantitative computed tomography study between young and old starters and controls. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17(12):2281–2289. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.12.2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kontulainen SA, Johnston JD, Liu D, et al. Strength indices from pQCT imaging predict up to 85% of variance in bone failure properties at tibial epiphysis and diaphysis. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2008;8(4):401–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kriemler S, Zahner L, Puder JJ, et al. Weight-bearing bones are more sensitive to physical exercise in boys than in girls during pre- and early puberty: a cross-sectional study. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19(12):1749–1758. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0611-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kriska AM, Bennett PH. An epidemiological perspective of the relationship between physical activity and NIDDM: from activity assessment to intervention. Diabetes Metab Rev. 1992;8(4):355–372. doi: 10.1002/dmr.5610080404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, et al. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data. 2000;8(314):1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lanyon LE. Functional strain in bone tissue as an objective, and controlling stimulus for adaptive bone remodelling. J Biomech. 1987;20(11–12):1083–1093. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(87)90026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee DC, Gilsanz V, Wren TA. Limitations of peripheral quantitative computed tomography metaphyseal bone density measurements. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(11):4248–4253. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lohman TG, Roche AF, Martorell R. Anthropometric Standardization Reference Manual. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1988. pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McMurray RG, Ring KB, Treuth MS, et al. Comparison of two approaches to structured physical activity surveys for adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(12):2135–2143. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000147628.78551.3b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mirwald RL, Baxter-Jones AD, Bailey DA, Beunen GP. An assessment of maturity from anthropometric measurements. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(4):689–694. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200204000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris NM, Udry RJ. Validation of a Self-Administered Instrument to Assess Stage of Adolescent Development. J Youth Adolesc. 1980;9(3):271–280. doi: 10.1007/BF02088471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pate RR, Ross R, Dowda M, Trost SG, Sirard JR. Validation of a 3-day physical activity recall instrument in female youth. Ped Ex Sci. 2003;15:257–265. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ridley K, Ainsworth BE, Olds TS. Development of a compendium of energy expenditures for youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5:45. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robling AG, Castillo AB, Turner CH. Biomechanical and molecular regulation of bone remodeling. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2006;8:455–498. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.8.061505.095721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rowlands AV, Pilgrim EL, Eston RG. Seasonal changes in children's physical activity: an examination of group changes, intra-individual variability and consistency in activity pattern across season. Ann Hum Biol. 2009;36(4):363–378. doi: 10.1080/03014460902824220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rubin CT, Lanyon LE. Regulation of bone formation by applied dynamic loads. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66(3):397–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sardinha LB, Baptista F, Ekelund U. Objectively measured physical activity and bone strength in 9-year-old boys and girls. Pediatrics. 2008;122(3):e728–e736. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seeman E. Invited Review: Pathogenesis of osteoporosis. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95(5):2142–2151. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00564.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seeman E, Delmas PD. Bone quality--the material and structural basis of bone strength and fragility. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(21):2250–2261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra053077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shedd KM, Hanson KB, Alekel DL, et al. Quantifying leisure physical activity and its relation to bone density and strength. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(12):2189–2198. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e318155a7fe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sherar LB, Baxter-Jones AD, Mirwald RL. Limitations to the use of secondary sex characteristics for gender comparisons. Ann Hum Biol. 2004;31(5):586–593. doi: 10.1080/03014460400001222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tamaki J, Ikeda Y, Morita A, et al. Which element of physical activity is more important for determining bone growth in Japanese children and adolescents: the degree of impact, the period, the frequency, or the daily duration of physical activity? J Bone Miner Metab. 2008;26(4):366–372. doi: 10.1007/s00774-007-0839-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tobias JH, Steer CD, Mattocks CG, Riddoch C, Ness ARCD, Mattocks CG, Riddoch C, Ness AR. Habitual levels of physical activity influence bone mass in 11-year-old children from the United Kingdom: findings from a large population-based cohort. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22(1):101–109. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tudor-Locke C, Pangrazi RP, Corbin CB, et al. BMI-referenced standards for recommended pedometer-determined steps/day in children. Prev Med. 2004;38(6):857–864. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Umemura Y, Ishiko T, Yamauchi T, Kurono M, Mashiko S. Five jumps per day increase bone mass and breaking force in rats. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12(9):1480–1485. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.9.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang QJ, Suominen H, Nicholson PH, et al. Influence of physical activity and maturation status on bone mass and geometry in early pubertal girls. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2005;15(2):100–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2004.00402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weeks BK, Beck BR. The BPAQ: a bone-specific physical activity assessment instrument. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19(11):1567–1577. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0606-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]