Abstract

Many RNAs contain tertiary interactions that contribute to folding the RNA into its functional 3D structure. In the VS ribozyme, a tertiary loop–loop kissing interaction involving stem–loops I and V is also required to rearrange the secondary structure of stem–loop I such that nucleotides at the base of stem I, which contains the cleavage–ligation site, can adopt the conformation required for activity. In the current work, we have used mutants that constitutively adopt the catalytically permissive conformation to search for additional roles of the kissing interaction in vitro. Using mutations that disrupt or restore the kissing interaction, we find that the kissing interaction contributes ∼1000-fold enhancement to the rates of cleavage and ligation. Large Mg2+-dependent effects on equilibrium were also observed: in the presence of the kissing interaction cleavage is favored >10-fold at micromolar concentrations of Mg2+; whereas ligation is favored >10-fold at millimolar concentrations of Mg2+. In the absence of the kissing interaction cleavage exceeds ligation at all concentrations of Mg2+. These data provide evidence that the kissing interaction strongly affects the observed cleavage and ligation rate constants and the cleavage–ligation equilibrium of the ribozyme.

INTRODUCTION

Many RNAs require a particular tertiary structure (3D folded state) to perform their functions. Formation of this structure is typically a hierarchical process that begins with base pairing of nucleotides near each other in the sequence to form secondary structures called helices and hairpin stem–loops. This is followed by tertiary interactions between these secondary structure elements to form the fully folded structure (1). Cations, in some cases specific monovalent or divalent metal ions, are required for tertiary folding (2).

In some, possibly all, RNAs the ‘fully folded’ state actually comprises a dynamic equilibrium among several tertiary structures (3–5). Some information about the contributions of tertiary interactions to the stability and dynamics of the folded structure can be obtained by biophysical and biochemical approaches (6,7). However, some consequences of tertiary interactions cannot be inferred from analyzing the structure(s) alone, but are reflected in their effects on RNA function. RNAs with intrinsic functions, such as ribozymes, have proven to be a useful class of molecules with which to study RNA tertiary structure because the kinetic properties of their easily measured catalytic activities can reflect the extent to which tertiary structure is correctly formed.

Among the many types of tertiary interaction that have been described, base-pairing between hairpin loops (‘kissing loops’) is common in many RNAs; interactions between hairpin loops and other unpaired nucleotides have also been observed (8). The Neurospora VS ribozyme contains a kissing loop interaction between hairpin loops I and V that is important for activity (9). Although there is no atomic-resolution structure of the entire VS ribozyme, biochemical, biophysical and modeling experiments provide evidence that the kissing loop interaction contributes to positioning helix I, which contains the cleavage–ligation site, in the correct position relative to the rest of the ribozyme to allow catalysis (10–17). These experiments have provided useful information about the role of the kissing loop interaction in ribozyme function under the specific in vitro conditions used: typically those conditions have included very high concentrations of divalent cations in an effort to maximize the catalytic activity of the ribozyme. In the current work we show that important features of RNA function have been overlooked previously, and that the kissing loop interaction plays an important role in determining cleavage–ligation equilibrium, especially at low (physiological) cation concentrations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid clones encoding RS19 and RS19ΔL have been described previously (18,19). Oligonucleotide-directed site-directed mutagenesis was used to construct the clones described in Figure 1C and D, which were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The choice of mutant sequences to disrupt and restore the kissing interaction was informed by previous studies that identified constraints on the identities of certain nucleotides in each loop in addition to those required for base pairing between loops I and V (9).

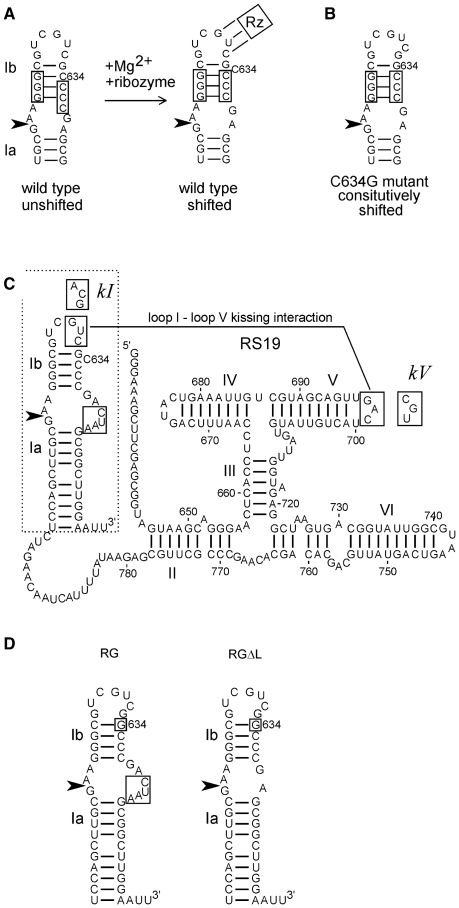

Figure 1.

Sequences and structures of VS ribozyme constructs. (A) The secondary structure of helix Ib and the internal loop containing the cleavage–ligation site (arrowhead) rearranges during Mg2+-dependent folding with the rest of the ribozyme (represented by Rz; the three lines connecting loop I to Rz represent the loop I–loop V kissing interaction [see Figure 1C and ref. (18,20)]. (B) The C634G mutant constitutively adopts the shifted conformation required for activity. (C) Secondary structure diagram of the RS19 version of the VS ribozyme, drawn with helix I in the shifted conformation (with C634 bulged out of the helix). Nucleotide numbers correspond to full-length VS RNA; helices are numbered with Roman numerals; the cleavage–ligation site is indicated by the arrowhead (19,38). The non-natural four extra nucleotides in the 3′ side of the cleavage–ligation site loop are boxed [see ref. (19) for details]. Boxed sequences in loops I and V interact via a kissing interaction indicated by the solid line (9). Mutant loop I and V sequences used to construct the kI, kV and kI+V mutants are indicated in boxes adjacent to their natural loop sequences. (D) The region of the RS19 ribozyme (dashed outline in C) into which the C634G mutation (boxed) was introduced to construct the RG ribozyme; deletion of the four non-natural nucleotides in the cleavage site loop of RG produced the RGΔL ribozyme.

Preparation of precursor RNAs, self-cleavage time courses and data analyses were performed as described in (19). Briefly, RNAs were transcribed from linearized plasmids in the presence of [α-32P]-GTP at low concentrations of MgCl2 to minimize self-cleavage during transcription. Uncleaved precursor RNA was purified by denaturing gel electrophoresis, eluted and dissolved in water. Cleavage reactions were performed at 37°C either by manual mixing and removing aliquots at specified times or using a Kintek RQF-3 rapid quench flow instrument (Kintek Corp, Clarence, PA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. One time reaction conditions contained 20 nM RNA, 40 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 50 mM KCl, 2 mM spermidine and 200 mM MgCl2. Aliquots from each time point were subjected to denaturing gel electrophoresis and exposed to a PhosphorImager screen. Band intensities were quantified using ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics/Amersham Biosciences/GE Healthcare).

Data were analyzed as described in (19). Cleavage data (fraction cleaved, fclv, at time, t) were normalized and fit to the first-order equation:

| (1) |

which corrects for the presence of any cleaved RNA in the starting material, f0 and allows estimation of the apparent maximal extent of cleavage, fmax and the apparent first-order cleavage rate constant, kobs.

Individual apparent cleavage and ligation rate constants, k1 and k−1, respectively, were estimated by fitting the normalized cleavage data to an equation derived by solving the system of differential equations describing the simplest approach-to-equilibrium model:

| (2) |

with the assumption that 100% of the precursor is cleavable. This equation is equivalent to Equation (1), where

| (3,4) |

RESULTS

VS ribozyme helix Ib adopts either of two secondary structures, called unshifted and shifted (Figure 1A). The shifted conformation is required for the loop at the base of helix Ib, which contains the cleavage–ligation site, to adopt the conformation needed for catalytic activity. However, the unshifted conformation predominates in the absence of Mg2+ or in the absence of the kissing interaction even in the presence of Mg2+ (18,20–23). Several sequence variants of helix Ib have been identified through in vitro selection and site-directed mutagenesis that constitutively adopt the shifted conformation: these variant RNAs exhibit some Mg2+-dependent self-cleavage activity even in the absence of the kissing interaction (18). In the current work, we introduced one such variant, a C634G substitution (Figure 1B), into helix Ib of the RS19 self-cleaving VS ribozyme (Figure 1C) to construct a version of the ribozyme called RG (abbreviated from RS19 C634G; Figure 1C and D). The RS19 and RG RNAs contain a non-natural 4-nt insertion in the cleavage site loop; we also constructed a version of RG in which the natural sequence was restored by deleting the extra loop nucleotides (called RGΔL; Figure 1D). Such constitutively shifted mutants of helix Ib allow us to examine other possible roles of the kissing interaction, independent of its role in rearranging the secondary structure of helix Ib into the conformation required for cleavage.

The I–V kissing interaction decreases the Mg2+ optimum and increases the cleavage rate of the RG ribozyme

The simplest version of the ribozyme in which to use ribozyme kinetics to investigate the roles of the kissing interaction is the RG construct which exhibits little, if any, re-ligation (19). Representative cleavage curves obtained in MgCl2 concentrations ranging from 25 µM to 200 mM are shown in Figure 2A. Cleavage was detected at [MgCl2] as low as 5 um (data not shown) but non-specific degradation at very long time points (above about 20 h) prevented us from measuring rates at lower MgCl2 concentrations, and from obtaining curves that reached completion in concentrations of MgCl2 below about 25 µM. All of the cleavage curves fit well to a first-order rate equation (r2 > 0.99) irrespective of whether the cleavage reaction occurred in milliseconds or hours [although at high MgCl2 concentrations the progress curve is more complex due to an on-pathway step detectable during the first few percent of cleavage; see reference (19) for details]. The apparent cleavage rate constants are plotted as a function of [MgCl2] in Figure 2B and show that the RG construct allows rates to be measured over at least five orders of magnitude of rate and MgCl2 concentration.

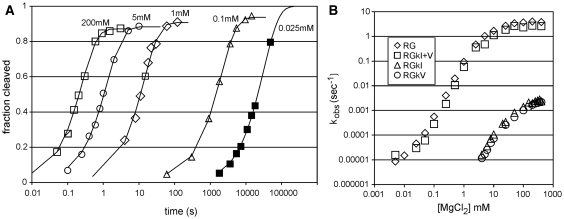

Figure 2.

Self-cleavage of the RG ribozyme and mutants with a disrupted or restored kissing interaction. (A) Example time courses of RG self-cleavage at the indicated concentrations of MgCl2. To display the wide range of observed cleavage rates, the time coordinate (X-axis) is plotted using a log10 scale. (B) Apparent first-order cleavage rate constants (kobs) for RNAs with an intact (RG, RGkI+V) or disrupted (RGkI, RGkV) kissing interaction. Data are the means of two to five replicates; SDs (data not shown for clarity) were typically less than the size of the symbols used to plot the means.

To investigate the contribution of the kissing interaction to cleavage rate, comparable cleavage curves were obtained for mutants RGkI and RGkV which disrupt the kissing interaction via triple mutations in loops I or V, respectively, and for a compensatory mutant, RGkI+V, which restores the interaction by combining the self-complementary kI and kV mutant sequences to form three base pairs different from those in the wild-type RG RNA (Figure 1C). Self-cleavage curves for all mutant RNAs fit well to first-order equations. For reactions at high enough concentrations of MgCl2 that the final extent of cleavage could be experimentally measured, final extents of cleavage >85% were observed (data not shown). Plots of kobs versus [MgCl2] in Figure 2B show that disrupting the kissing interaction with mutations in either loop I or loop V caused ∼1000-fold decrease in cleavage rate over the range of MgCl2 concentrations examined. An alternative way to look at these data would be that mutants with a disrupted kissing interaction require 1000-fold higher MgCl2 concentration to obtain a given cleavage rate. The compensatory mutant RGkI+V, in which the kissing interaction is restored using different base pairs, exhibited a rate versus [MgCl2] curve almost the same as wild-type. These data indicate that the slow cleavage of the individual kissing interaction mutants is not due to the mutant loop sequences per se, but to disruption of the kissing interaction.

The I–V interaction affects cleavage–ligation equilibrium in RNAs containing the natural sequence in the cleavage site loop

As noted above, the RG RNA exhibits little if any re-ligation. RNAs in which the extra 4 nt in the cleavage loop were deleted, thereby restoring the natural sequence in the cleavage site loop, are capable of both cleavage and ligation. We had previously characterized one such RNA, RS19ΔL, at saturating MgCl2 and observed a burst of very fast cleavage (kobs = 2 s−1) in which ∼10% of the RNA appeared to cleave. Chase experiments showed that this kinetic behavior reflected an approach to equilibrium where the low apparent extent of cleavage actually reflected re-ligation. Under these conditions, ligation is favored ∼10-fold over cleavage (19). In the current work we have examined cleavage and ligation of the related RGΔL RNA (Figure 1C) over a wide range of [MgCl2] and found a very different relationship than described above for RG.

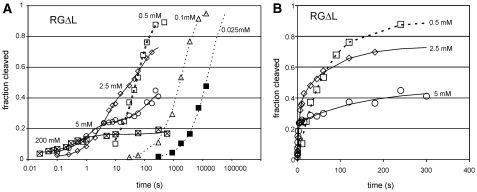

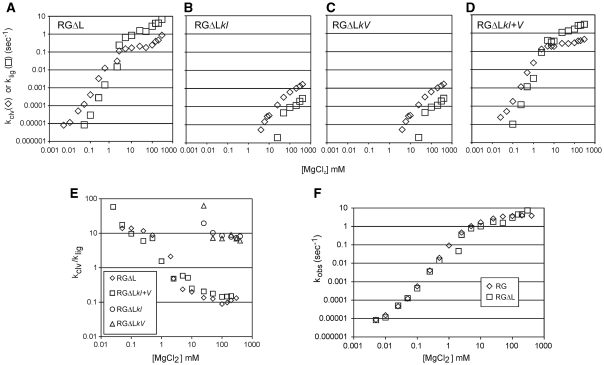

As observed with RG, cleavage of RGΔL was detectable at MgCl2 concentrations in the low micromolar range; reactions in MgCl2 concentrations below about 0.1 mM proceeded to completion and curves fit well to a first-order equation (Figure 3A and data not shown). However, at higher concentrations the curves became noticeably biphasic, with a decreasing proportion of the RNA appearing to cleave in the fast phase, and a decreased apparent final extent of cleavage (examples at selected MgCl2 concentrations are shown in Figure 3A, and in more conventional plot in Figure 3B). Chase experiments [data not shown; performed as in (19)] revealed that the low extent of cleavage at high MgCl2 concentrations is due to a cleavage–ligation equilibrium that favors cleavage, as described previously for the RS19ΔL (19). Fitting the fraction cleaved versus time data for RGΔL at each [MgCl2] to an equation that allowed estimation of the cleavage and ligation rate constants separately showed that both rate constants increase with increasing MgCl2, but klig has the steeper slope (Figure 4A). As a result, equilibrium strongly favors ligation at high concentrations of MgCl2 and strongly favors cleavage at low concentrations of MgCl2 (Figure 4E). The overall catalytic rate constant kobs (= kclv + klig) is essentially the same for RG and RGΔL over the entire range of MgCl2 concentrations (Figure 4F), indicating that the differences in sequence and structure in the cleavage site loop have no net effect on catalytic ability, but they substantially alter the cleavage–ligation equilibrium.

Figure 3.

Self-cleavage of the RGΔL ribozyme. (A) Example time courses of RG self-cleavage at the indicated concentrations of MgCl2; plotted as in Figure 2. (B) Conventional plot of fraction cleaved versus time showing biphasic cleavage at higher MgCl2 concentrations.

Figure 4.

Mg2+ dependence of the cleavage and ligation rate constants of the RGΔL ribozyme and mutants with a disrupted or restored kissing interaction. (A–D) Apparent first-order cleavage (kclv) and ligation (klig,) rate constants for RGΔL RNAs with an intact (RGΔL, RGΔLkI+V) or disrupted (RGΔLkI, RGΔLkV) kissing interaction. (E) Mg2+ dependence of the ratio of cleavage to ligation rate constants in RGΔL and its mutants. (F) Mg2+ dependence of the apparent overall first-order rate constant for RG and RGΔL RNAs.

To investigate the contribution of the kissing loop interaction to cleavage and ligation rates, equilibrium and cation concentration requirement, the same kissing loop disruption mutations described for RG above were introduced into RGΔL to make RGΔLkI and RGΔLkV. The compensatory RGΔLkI+V mutant which restored the kissing interaction was also characterized. In RGΔL mutants with disrupted kissing interactions, kclv and klig are both several orders of magnitude slower than in the presence of the kissing interaction (Figure 4B and C). However, unlike RNAs with an intact kissing interaction (Figure 4A and D), cleavage is favored over ligation in the loop-disrupted mutants even at the highest concentrations of MgCl2 (Figure 4E). Thus, even in RNAs with the natural cleavage loop sequence (which favors ligation over cleavage) the kissing interaction is required to favor ligation.

DISCUSSION

The loops I–V kissing interaction in the VS ribozyme had previously been shown to be important for formation of the shifted (active) conformation of stem–loop I (18,20), binding of free stem–loop I to a trans-acting version of the ribozyme (24) and rapid folding and formation of the solvent-inaccessible core (14). In the current work, we show that this tertiary interaction is also important for cleavage at low (physiological) concentrations of Mg2+, for fast cleavage and ligation, and for shifting the equilibrium in favor of ligation. Considering that circular (ligated) VS is the predominant form of VS RNA in vivo (25), the current observations suggest that the kissing loop interaction may be an important structural feature for producing the biological form of VS RNA.

Much of the recent work on the VS ribozyme has been focused on the chemical mechanism of the reaction (26–30). In those experiments, non-physiologically high concentrations of cations were used to ensure that the observed reaction rate was not limited by ion binding. Our only detailed examination of cleavage rates over a wide range of cation concentrations was performed using constructs that cleaved essentially to completion; ligation was, therefore, not examined (31). Under high-salt conditions we had previously observed that some VS ribozyme constructs favored cleavage whereas others favored ligation (19); however, prior to the current work, we had not examined whether this preference was inherent to a particular RNA construct or whether it could be altered by environmental (e.g. ionic) conditions. The current work shows that, while different versions of the VS ribozyme have different intrinsic preferences for cleavage versus ligation, the ionic conditions can strongly affect those preferences.

Tertiary interactions between structural elements distant from the catalytic core have also been recognized in RNAs that contain hammerhead ribozymes. In several of these natural or ‘extended’ hammerhead RNAs, the peripheral tertiary interactions decrease the concentration of cations required for catalytic activity (32) and increase the rates of cleavage and ligation (33–35); in one counter example, the peripheral interaction in the barley yellow dwarf virus satellite RNA hammerhead decreases its cleavage rate (36). Recent single-molecule kinetic analyses have provided evidence that the peripheral tertiary interaction in an extended hammerhead ribozyme may affect activity by dynamically favoring a particular RNA conformation (37).

Similar to the current observations on the VS ribozyme, extended hammerhead ribozymes also show a preference for ligation (compared to minimal hammerheads lacking the peripheral tertiary interaction), and exhibit substantial ligation even at low concentrations of divalent cations (34). The similarities in the effects of these peripheral tertiary interactions in two ribozymes with very different structures suggests that such interactions may be a general mechanism for tuning the cleavage and ligation rates of a ribozyme to the low divalent ion concentrations typically available in vivo.

FUNDING

Funding for open access charge: Canadian Institutes for Health Research (MOP-12837 to R.A.C.).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Andrew Keeping and Deborah Field for comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tinoco I, Jr, Bustamante C. How RNA folds. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;293:271–281. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Draper DE, Grilley D, Soto AM. Ions and RNA folding. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2005;34:221–243. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.34.040204.144511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Hashimi HM, Walter NG. RNA dynamics: it is about time. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2008;18:321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brion P, Westhof E. Hierarchy and dynamics of RNA folding. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 1997;26:113–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.26.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woodson SA. Compact intermediates in RNA folding. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2010;39:61–77. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.093008.131334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herschlag D. Biophysical, Chemical, and Functional Probes of RNA Structure, Interactions and Folding: Part A. Methods in Enzymology 468. San Diego, USA: Elsevier, Inc.; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herschlag D. Biophysical, Chemical, and Functional Probes of RNA Structure, Interactions and Folding: Part B. Methods in Enzymology 469. San Diego, USA: Elsevier, Inc.; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bindewald E, Hayes R, Yingling Y, Kasprzak W, Shapiro BA. RNAJunction: a database of RNA junctions and kissing loops for three-dimensional structural analysis and nanodesign. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D392–D397. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rastogi T, Beattie TL, Olive JE, Collins RA. A long-range pseudoknot is required for activity of the Neurospora VS ribozyme. EMBO J. 1996;15:2820–2825. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sood VD, Collins RA. Identification of the catalytic subdomain of the VS ribozyme and evidence for remarkable sequence tolerance in the active site loop. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;320:443–454. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00521-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rastogi T, Collins RA. Smaller, faster ribozymes reveal the catalytic core of Neurospora VS RNA. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;277:215–224. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins RA. The Neurospora Varkud satellite ribozyme. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2002;30:1122–1126. doi: 10.1042/bst0301122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiley SL, Sood VD, Fan J, Collins RA. 4-thio-U cross-linking identifies the active site of the VS ribozyme. EMBO J. 2002;21:4691–4698. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hiley SL, Collins RA. Rapid formation of a solvent-inaccessible core in the Neurospora Varkud satellite ribozyme. EMBO J. 2001;20:5461–5469. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.19.5461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lipfert J, Ouellet J, Norman DG, Doniach S, Lilley DM. The complete VS ribozyme in solution studied by small-angle X-ray scattering. Structure. 2008;16:1357–1367. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pereira MJ, Nikolova EN, Hiley SL, Jaikaran D, Collins RA, Walter NG. Single VS ribozyme molecules reveal dynamic and hierarchical folding toward catalysis. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;382:496–509. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bouchard P, Lacroix-Labonte J, Desjardins G, Lampron P, Lisi V, Lemieux S, Major F, Legault P. Role of SLV in SLI substrate recognition by the Neurospora VS ribozyme. RNA. 2008;14:736–748. doi: 10.1261/rna.824308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersen AA, Collins RA. Rearrangement of a stable RNA secondary structure during VS ribozyme catalysis. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:469–478. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80441-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zamel R, Poon A, Jaikaran D, Andersen A, Olive J, De Abreu D, Collins RA. Exceptionally fast self-cleavage by a Neurospora Varkud satellite ribozyme. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:1467–1472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305753101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andersen AA, Collins RA. Intramolecular secondary structure rearrangement by the kissing interaction of the Neurospora VS ribozyme. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:7730–7735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141039198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flinders J, Dieckmann T. A pH controlled conformational switch in the cleavage site of the VS ribozyme substrate RNA. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;308:665–679. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoffmann B, Mitchell GT, Gendron P, Major F, Andersen AA, Collins RA, Legault P. NMR structure of the active conformation of the Varkud satellite ribozyme cleavage site. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:7003–7008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0832440100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michiels PJ, Schouten CH, Hilbers CW, Heus HA. Structure of the ribozyme substrate hairpin of Neurospora VS RNA: a close look at the cleavage site. RNA. 2000;6:1821–1832. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200001394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zamel R, Collins RA. Rearrangement of substrate secondary structure facilitates binding to the Neurospora VS ribozyme. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;324:903–915. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01151-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saville BJ, Collins RA. A site-specific self-cleavage reaction performed by a novel RNA in Neurospora mitochondria. Cell. 1990;61:685–696. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90480-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaikaran D, Smith MD, Mehdizadeh R, Olive J, Collins RA. An important role of G638 in the cis-cleavage reaction of the Neurospora VS ribozyme revealed by a novel nucleotide analog incorporation method. RNA. 2008;14:938–949. doi: 10.1261/rna.936508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith MD, Collins RA. Evidence for proton transfer in the rate-limiting step of a fast-cleaving Varkud satellite ribozyme. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:5818–5823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608864104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith MD, Mehdizadeh R, Olive JE, Collins RA. The ionic environment determines ribozyme cleavage rate by modulation of nucleobase pK a. RNA. 2008;14:1942–1949. doi: 10.1261/rna.1102308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson TJ, Li NS, Lu J, Frederiksen JK, Piccirilli JA, Lilley DM. Nucleobase-mediated general acid-base catalysis in the Varkud satellite ribozyme. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:11751–11756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004255107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson TJ, McLeod AC, Lilley DM. A guanine nucleobase important for catalysis by the VS ribozyme. EMBO J. 2007;26:2489–2500. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poon AH, Olive JE, McLaren M, Collins RA. Identification of separate structural features that affect rate and cation concentration dependence of self-cleavage by the Neurospora VS ribozyme. Biochemistry. 2006;45:13394–13400. doi: 10.1021/bi060769+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khvorova A, Lescoute A, Westhof E, Jayasena SD. Sequence elements outside the hammerhead ribozyme catalytic core enable intracellular activity. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003;10:708–712. doi: 10.1038/nsb959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Canny MD, Jucker FM, Kellogg E, Khvorova A, Jayasena SD, Pardi A. Fast cleavage kinetics of a natural hammerhead ribozyme. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:10848–10849. doi: 10.1021/ja046848v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Canny MD, Jucker FM, Pardi A. Efficient ligation of the Schistosoma hammerhead ribozyme. Biochemistry. 2007;46:3826–3834. doi: 10.1021/bi062077r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De la Pena M, Gago S, Flores R. Peripheral regions of natural hammerhead ribozymes greatly increase their self-cleavage activity. EMBO J. 2003;22:5561–5570. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller WA, Silver SL. Alternative tertiary structure attenuates self-cleavage of the ribozyme in the satellite RNA of barley yellow dwarf virus. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:5313–5320. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.19.5313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McDowell SE, Jun JM, Walter NG. Long-range tertiary interactions in single hammerhead ribozymes bias motional sampling toward catalytically active conformations. RNA. 2010;16:2414–2426. doi: 10.1261/rna.1829110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beattie TL, Olive JE, Collins RA. A secondary-structure model for the self-cleaving region of Neurospora VS RNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:4686–4690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]