Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is a frequent sequela in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2). We conducted a pilot study to investigate functional, metabolic and penile morphological changes in a novel model of lean DM2.

METHODS

Eight rats received a high-fat diet and two weeks later, two intraperitoneal injections of streptozotocin (STZ, 30 mg/kg). Five age-matched rats served as controls. Insulin challenge tests were performed at 6 and 12 weeks after induction of DM2. At 12 weeks, erectile function was tested by measurement of intracavernous pressure (ICP) increase upon cavernous nerve stimulation. Penile tissue and serum samples were harvested for histology and biochemistry, respectively.

RESULTS

A lean DM2 model was established as demonstrated by decreased insulin resistance, elevated non-fasting plasma glucose levels, hyperlipidemia and decreased insulin concentration in the absence of obesity. ICP/mean arterial pressure was significantly decreased in DM2 animals (0.29) compared to controls (0.81). Expression of nNOS and RECA1, and the smooth muscle/collagen ratio were significantly decreased in the penis of DM2 animals.

CONCLUSIONS

We propose an inexpensive nongenetic animal model of lean DM2-associated ED. Micro-anatomical changes in the erectile tissue that reflect an advanced stage of the disease were observed.

Keywords: collagen-IV, Diabetes type 2, endothelium, erectile dysfunction, lean, nNOS, rat model, smooth muscle

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2) constitutes a major risk factor for erectile dysfunction (ED). In a recent study, 3 out of 5 men with DM2 lasting 6 months to 10 years suffered from ED and two-thirds of those had moderate or severe ED1. Several studies have concluded that ED in DM2 is associated with a hypercontractile state of the penile smooth muscle, an impairment of endothelial function, and changes in collagen and elastin metabolism, which together manifest symptoms of corporeal veno-occlusive dysfunction2-7. However, most of these studies were conducted with expensive genetic rat models of DM2 that reproduce some but not all aspects of the natural disease progression2-8. In a recent study Chiou et al 9 established a DM2-ED rat model by feeding of a high-fat diet (HFD) combined with injection of low dosed streptozotocin (STZ). Independently, we have also developed a comparable DM2 model for ED research in which the development of DM2 closely resembles the natural disease progression in humans. This novel model is inexpensive compared to the currently available genetic models, is easy to establish, and has high success rates of diabetic induction10. Furthermore, this model possesses a lean phenotype rather than the obese phenotype which characterizes the commonly used genetic models, while possessing biochemical characteristics of the metabolic syndrome10. The aim of our pilot study was to assess the development of ED in this lean model of DM2 including metabolic, hormonal, functional, and morphological characteristics.

Materials and methods

Study design and induction of type 2 diabetes mellitus

For this pilot study, eight male Sprague Dawley rats (12 weeks old) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA, USA) for induction of DM2 (DM2-group). Five age-matched animals served as non-diabetic controls (control-group). The animals were maintained on a 12 hours light/dark cycle and had access to water ad libitum. The experimental group was fed rat chow containing 2% cholesterol and 10% lard (Zeigler Bros, Gardners, PA, USA). Two weeks later, rats in the DM2 group received two intraperitoneal injections of streptozotocin (STZ, 30 mg/kg) 3 days apart, while the control rats were given vehicle citrate buffer in a dose volume of 0.25 mL/kg, respectively. Starting from the first day of STZ injection (week 0), postprandial capillary blood glucose was monitored weekly by tail tip snipping and measurement with an accu-check® advantage blood glucose meter (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). An IP insulin challenge test was conducted at 6 and 12 weeks following STZ injection. At 12 weeks following injection of STZ, all rats underwent erectile function evaluation. The animals were then sacrificed and the penis was harvested for histological analysis. Serum was collected for measurement of lipid, testosterone, and insulin levels. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of California, San Francisco.

Intraperitoneal insulin challenge test

For measurement of the sensitivity to a challenge of insulin, one IU/kg bovine insulin in phosphate buffered solution (1 IU/ml) was administered by intraperitoneal injection and tail snip capillary blood samples were collected at 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90 and 120 minutes following injection for obtaining a blood glucose response curve. The glucose levels are presented as percentages of plasma glucose level before insulin injection (baseline).

Assessment of Erectile Function

Twelve weeks after STZ injection, erectile function was assessed. Under Ketamine (100 mg/kg) and Midazolam (5mg/kg) anesthesia, the major pelvic ganglion and the cavernous nerves were exposed bilaterally via midline laparotomy. A 23G butterfly needle was inserted into the proximal left corpus cavernosum, filled with 250 U/mL heparin solution and connected to a pressure transducer (Utah Medical Products, Midvale, UT, USA) for intracavernous pressure (ICP) measurement. The ICP was recorded at a rate of 10 samples/second using a computer with LabView 6.0 software (National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA). A bipolar stainless-steel hook electrode was used to stimulate the CN directly (each pole 0.2 mm in diameter, separated by 1 mm) via a signal generator (National Instruments) generating monophasic rectangular pulses with stimulus parameters of 1.5 mA, 20 Hz, pulse width 0.2 ms, and duration 50 seconds. Three stimulations were conducted per side and the erection with maximum increase in ICP was included for statistical analysis in each animal. Systemic blood pressure was recorded using a 23G butterfly needle inserted into the aorta at the level of the aortic bifurcation, for the calculation of the ICP increase/mean arterial pressure (MAP) ratio. Venous blood was collected from the inferior vena cava before animals were euthanized.

Serum analysis

Venous blood was collected in mini-serum gel separator tubes (BD Microtainer®, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and centrifuged for 90 sec. at 15.000 g. For analysis of the lipid panel, serum was examined by the Comparative Pathology Laboratory of the University of California, Davis School of Veterinary Medicine. Testosterone (RD systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and insulin (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Histology

Mid-penile tissue was harvested and fixed in cold 2% formaldehyde and 0.002% saturated picric acid in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 8.0, for 4 h followed by overnight immersion in buffer containing 30% sucrose. The specimens were then embedded in OCT Compound (Sakura Finetec, Torrance, CA, USA) and stored at −80 °C until use. Fixed frozen tissue specimens were cut at 5 microns, mounted onto SuperFrost-Plus charged slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) and air dried on a warm plate for 5 min. For immunofluorescence staining, tissue sections were placed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, washed twice in PBS for 5 min and incubated with 3% horse serum in PBS/0.3% Triton X-100 for 30 min at room temperature. After draining the sections, the slides were incubated at 4 °C with mouse anti-RECA1 (rat endothelial cell antigen-1; ABD SEROTEC, Raleigh, NC, USA), rabbit anti-Collagen IV (Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA), or rabbit anti-nNOS (neuronal nitric oxide synthase; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) 1:400 in 3% horse serum/PBS. Control tissue sections were similarly prepared except no primary antibody was added. After rinses with PBS, the sections were incubated with Alexa-488 or Alexa-594 conjugated goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Following rinsing of the slides by PBS, tissue sections were stained for F-actin. Slides were therefore incubated with Alexa-488-conjugated phalloidin (1:500 in 1% BSA, Invitrogen) for 20 min at room temperature, followed by incubation with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, for nuclear staining, 1 mg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Slides were coverslipped with glycerol 50% in water. Collagen content was analyzed using Masson’s trichrome staining method.

Digital Analysis of Sections

Three mid-penile tissue sections per animal were included for statistical analysis. Slides were photographed and recorded using a Retiga 1300 digital camera (QImaging, Surrey, Canada) attached to a Nikon E300 microscope (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY, USA). Computerized histomorphometric analysis was performed using Image-Pro Plus 5.1 software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Statistical Analysis

The results were analyzed using Medcalc version 11.0.0.0 (Medcalc software, Belgium). To test the difference between means, Student’s T-test was used. Results were considered statistically significant if p<0.05. Data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Results

Establishment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

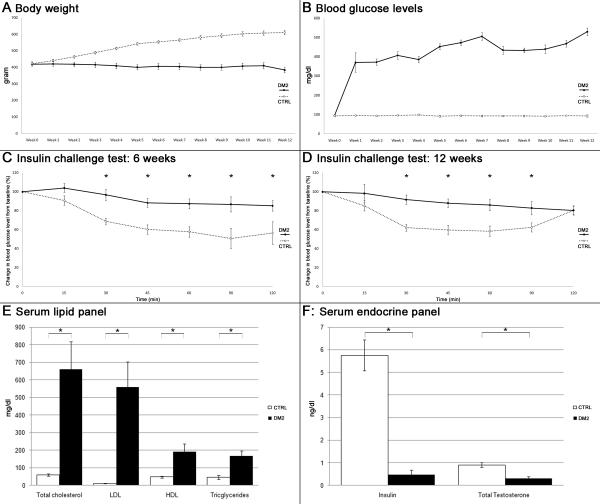

Body weight and postprandial blood glucose were measured weekly. While control rats gradually gained weight, DM2 rats showed little changes in body weight until week 11 when it started to decline (Fig. 1A). All animals in the DM2 group developed diabetes as indicated by blood glucose levels of >300 mg/dl one week after injection of STZ (Fig. 1B). Overt clinical features in DM2 rats included development of cataract and suppurative balanitis. The latter was treated by nontraumatic drainage and rinsing of the preputium and a short course of oral antibiotics. No animals died during the course of the study.

Fig. 1. Growth curves, glucose metabolism and serum biochemistry.

A: Graph depicts growth curves of the experimental animals. Body weight was measured weekly starting at the day of the first STZ injection. B: Postprandial blood glucose levels were measured weekly starting at the day of the first STZ injection. C,D: Insulin challenge test carried out 6 and 12 weeks following the first STZ injection. *: p < 0.05. E: Levels of lipids on rat serum biochemistry evaluation. *: p < 0.05. F: Levels of insulin and total testosterone in rat serum determined by ELISA. *: p < 0.05.

Since decreased sensitivity to insulin is a hallmark of DM2, insulin resistance was tested at weeks 6 and 12 after injection of STZ. The results show that DM2 rats lacked response to insulin challenge (Fig. 1C,D).

Serum analysis

Animals in the DM2 group showed significant increases in levels of serum triglycerides, total cholesterol, and low- and high-density lipoproteins (LDL and HDL). Testosterone and insulin levels were significantly lower compared to controls (Fig. 1 E,F).

Assessment of Erectile Function

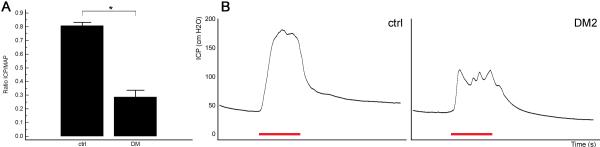

Induction of DM2 consistently resulted in erectile dysfunction as illustrated by a significant decline in ICP/MAP ratio upon CN electrostimulation in the STZ and HFD-treated group compared to control animals (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Erectile function upon cavernous nerve electrostimulation.

A: The effects of induction of DM2 on ratio of ICP/mean arterial pressure (MAP). *: p < 0.05. B: Representative ICP recordings per group. Note the spiky appearance of the plateau phase of the erection in diabetic rats, indicative of inability to maintain erection. The red bar represents an electrical stimulation of the cavernous nerve with a duration of 50 s.

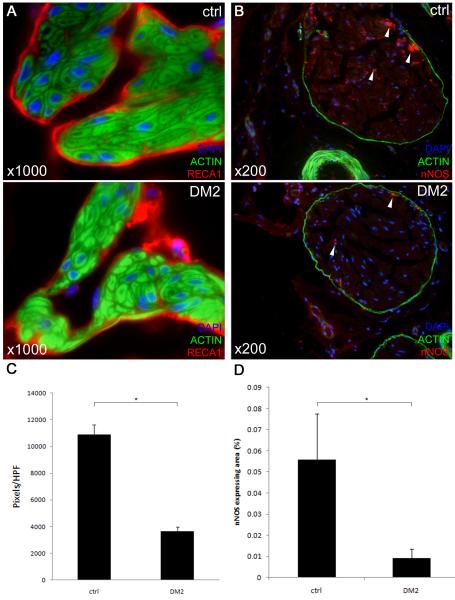

Histomorphometric Analysis

The cavernous endothelium of DM2 rats lost continuity and had a ‘patchy’ appearance (Fig. 3A). Expression of RECA1 was significantly decreased compared to age-matched controls (p < 0.001, Fig. 3C). Furthermore, significant decreases in nNOS content of the dorsal penile nerves were noted in DM2 rats (Fig. 3B,D).

Fig. 3. Changes in the endothelium and dorsal penile nerves in the diabetic rat penis.

A: Representative images of endothelial lining of sinusoids. Rat penis was stained with Alexa-488-conjugated phalloidin and with Alexa-594-conjugated anti-RECA1 antibody. Original magnification ×1000. Note the ‘patchy’ appearance of the endothelial lining in diabetic penile sinusoids whereas the endothelial lining is continuous in normal rats. B: Representative images of rat penile dorsal nerves. Rat penis was stained with Alexa-488-conjugated phalloidin and with Alexa-594-conjugated anti-nNOS antibody. Original magnification ×200. Note the significant decrease of nNOS positive nerve fibers, which are located mainly in the periphery of the dorsal nerve (arrows). C: Quantification of RECA1-staining in pixels/HPF, *: p < 0.001. D: Quantification of nNOS-staining in dorsal penile nerves, *: p < 0.001.

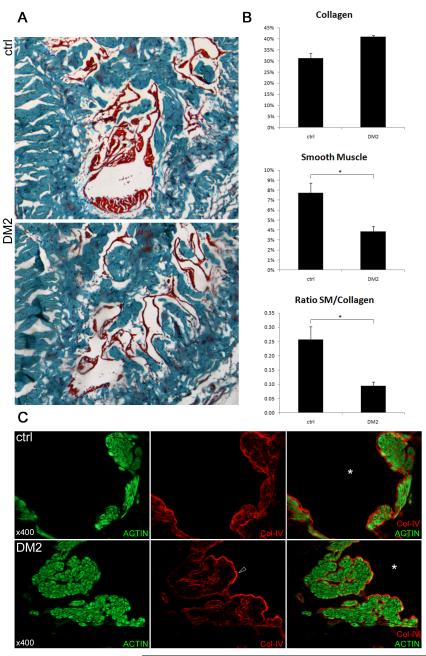

Masson’s trichrome stain showed that smooth muscle content was significantly lower in the corpus cavernosum of diabetic rats (p = 0.012). Collagen content was increased but this difference was not significant (p=0.04). Thus, the ratio of smooth muscle over collagen content was decreased in diabetic rats (Fig. 4 A,B). There were no major morphological alterations in cavernous smooth muscle after the induction of diabetes. However, the subendothelial basement membrane appeared slightly denser in the diabetic animals (Fig. 4 C).

Fig 4. Smooth muscle and extracellular matrix in the corpus cavernosum.

A: Representative pictures of the rat corpus cavernosum stained with Masson’s trichrome. Red color represents mainly smooth muscle, blue stains collagen fibers. Original magnification ×40. B: Histomorphometric analysis of the content of the corpus cavernosum. Upper and middle panel: collagen content and smooth muscle content in percentage of total intratunical area, lower panel: ratio smooth muscle (%) / collagen (%).*: p < 0.05. C: Rat penis was stained with Alexa-488-conjugated phalloidin and with Alexa-594-conjugated anti-collagen-IV antibody. Original magnification ×400. Representative high-power images of smooth muscle bundles lining a cavernosal sinusoid (*). Upper panel: normal rat, lower panel: diabetic rat. Note the somewhat denser expression of the sinusoidal subendothelial basement membrane in the diabetic rat sinus (arrowhead).

Discussion

In this study we confirmed the development of ED in a rat model of DM2 induced by HFD feeding combined with low-dose STZ injection. Chiou et al previously published the development of moderate erectile function impairment as early as 6 weeks after induction of diabetes in rats treated with HFD and low dosed STZ9. The authors demonstrated altered protein expression in the corpus cavernosum. As their study lacks data on insulin metabolism, it is unclear whether the proposed alterations in protein expression are related to an early (hyperinsulinemia) or advanced stage (hypoinsulinemia) of DM2. Most critical, however, is a lack of immunohistomorphometric analysis of the erectile apparatus. Indeed, in the literature high quality morphological data on erectile tissue in any DM2 rat model is rather scarce.

The induction of DM2 used in this study closely resembles the natural history of the disease. The two weeks of HFD feeding produces insulin resistance syndrome in the absence of hyperglycemia, a condition similar to pre-diabetes in humans11. Following two weeks of HFD, injections with low dose of STZ produced frank hyperglycemia and thus mimicked the decline in secretory capacity of pancreatic β-cells11. The persistent hyperglycemia further damages the pancreatic β-cells through gluco(lipo)toxicity, oxidative stress, amyloid deposition and an increase in circulating advanced end-products of glycation (AGEs). These factors cause islet inflammation and ultimately lead to apoptosis of β-cells resulting in hypoinsulinemia in the advanced stage of DM212. In addition, our model showed several hallmarks of DM2. First, as early as 6 weeks after injection of STZ, the treated rats did not show a significant drop in glucose levels upon injection of a fixed dose of insulin. This characteristic persisted into the later stage of the disease at 12 weeks and represents decreased insulin sensitivity; or insulin resistance. Second, by 12 weeks following STZ injections, endogenous insulin production had decreased dramatically, indicating the presence of β-cell failure. Third, the rats showed profound hyperlipidemia, hypercholesterolemia and hypogonadism, which are metabolic changes commonly seen in human DM2 patients and which, aside from the persistent hyperglycemia, might contribute to erectile and general tissue damage13.

Previously, ED in DM2 has been studied in genetic rat models such as the Zucker rat, the BBZ/WOR, and the Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima Fatty rat2,3. While these genetic models develop characteristics of DM2 similar to those in humans, costs can be as high as tenfold of those of Sprague-Dawley or Wistar rats. More importantly, these models unanimously are characterized by obesity and therefore fail to represent the rather large population of non-obese individuals who are metabolically abnormal but nevertheless exposed to an increased risk of diabetic and cardiovascular complications such as ED. In contrast, our STZ-HFD model does represent these patients as it is phenotypically lean while possessing the metabolic characteristics of DM2, including hyperlipidemia and hypogonadism. Thus, whereas the focus in the western world remains on the more prevalent obese patients, our lean DM2 model is better positioned to address the needs of the non-obese DM2 population, which is estimated to constitute 42% of DM2 cases worldwide14.

A decrease of endothelial function in the erectile tissue has been repeatedly described in the abovementioned DM2 genetic rat models5,7,15,16. However, little is known whether the endothelial dysfunction is associated with morphological changes in the cavernous endothelium. In the present suty, we observed a lower expression level of RECA1 in the corpus cavernosum of DM2 rats compared to their age-matched nondiabetic controls. By employing a novel phalloidin-based method for counterstaining of the cavernous smooth muscle, we were able to investigate the endothelial morphology with high accuracy. A striking micro-anatomical change resulting in disruption of the endothelial barrier had taken place in the diabetic animals. The endothelium had a ‘patchy’ appearance whereas control rats had an intact endothelial lining of the cavernous sinuses. These observed changes may be attributable to a combination of persisting hyperglycemia resulting in increased levels of reactive oxygen species, which in combination with increased LDL levels result in pathological, inflammatory changes, as previously described in the vascular endothelium17-21. In addition, diabetic rats showed profound hypogonadism, possibly contributing to a decreased endothelial integrity.

Reduced expression of nNOS in the penis of diabetic rats is a common finding in models for both chemically induced type 1 and genetic type 2 diabetes6,16,22,23. Furthermore, a previous publication showed with western blot anaysis that the amount of nNOS protein in HDF-STZ rats was significantly lower than in controls9. In the present study, we confirmed this finding immunohistochemically and showed a striking decrease in nNOS expression in the dorsal penile nerves of diabetic rats. A reduced nNOS expression results in a decrease in endogenous NO availability from the cavernous nerve endings and thereby impairs erectile function upon cavernous nerve stimulation. The reduced expression of nNOS, combined with a putative loss of endothelium-derived NO may explain the high rates of non-responders to PDE5-inhibitor therapy in advanced diabetic erectile dysfunction.

Various groups have described a decrease in corpus cavernosum smooth muscle content in DM2 rat models24. This decrease has been ascribed to an increased smooth muscle apoptotic rate and has further been linked to decreased circulating testosterone levels25. Moreover, increased deposition of collagen in the erectile tissue was found in diabetic animals and has been linked to increased levels of transforming growth factor beta in the diabetic penis24,26,27. In line with previous studies in other diabetic rat models, we found a decreased smooth muscle/total collagen ratio in the corpus cavernosum. However, detailed analysis of the smooth muscle morphology using phalloidin staining did not find significant morphological alterations other than changes in smooth muscle content identified by trichrome stain. A decreased smooth muscle/total collagen ratio may contribute to ED by decreasing the expandability of the sinusoids upon passive filling with blood, thereby resulting in veno-occlusive dysfunction28. Indeed, this structure-related dysfunction is reflected in the spiky shape of the plateau phase of the erection in the ICP recording, as evidenced in figure 2B.

Collagen-IV is an extracellular matrix molecule that is expressed in the subendothelial basement membrane. This protein further occurs in the basal lamina surrounding each individual smooth muscle cell in the corpus cavernosum (fig 4 C). It plays an important role in maintaining the contractile capacity of the smooth muscle bundle, and changes in its expression have been identified in diabetes-associated diseases, such as diabetic nephropathy29,30. In the present study we found that, although collagen-IV expression in the subendothelial basement membrane was somewhat higher in the DM2 than in the control group (Fig. 4 C), there was no difference in overall collagen-IV expression in the penis (data not shown).

Inherent to the concept of a pilot-study, the number of animals included in both groups was relatively low. In spite of these small group sizes, significant changes in both glucose and lipid metabolism, erectile biology and penile morphology were observed. These findings are promising for the use of this model for further research, including the investigation of novel treatment options for ED in diabetes. A larger scaled investigation towards the pathophysiological mechanisms involved in the development of ED is needed to further validate this animal model. Furthermore, insights in the role that altered collagen-IV metabolism plays in diabetic ED is needed and has recently been initiated in our laboratory.

Conclusions

Treatment of rats with low-dose STZ injection in combination with a high fat diet resulted in the establishment of a lean model of DM2 that mimicked the natural progression of the disease in humans. ED was present at 12 weeks after induction of diabetes and was histomorphometrically characterized by decreased nNOS expression, loss of endothelial integrity, and a decreased smooth muscle/collagen ratio. As such, this rat model is a more affordable alternative to the commonly used genetic rat models for the study of DM2-associated ED.

Acknowledgments

Source of funding: This work was funded by the national institutes of health (DK045370). MA is a fellow of the Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO), a scholar of the European Society of Surgical Oncology (ESSO), the Federico Foundation and Belgische Vereniging voor Urologie (BVU), and received an unrestricted research grant from Bayer Healthcare Belgium.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Giugliano F, Maiorino M, Bellastella G, et al. Determinants of erectile dysfunction in type 2 diabetes. Int J Impot Res. 2010;22(3):204–9. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2010.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chitaley K. Type 1 and Type 2 diabetic-erectile dysfunction: same diagnosis (ICD-9), different disease? J Sex Med. 2009;6(Suppl 3):262–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hidalgo-Tamola J, Chitaley K. Review type 2 diabetes mellitus and erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2009;6(4):916–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costa C, Soares R, Castela A, et al. Increased endothelial apoptotic cell density in human diabetic erectile tissue--comparison with clinical data. J Sex Med. 2009;6(3):826–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wingard C, Fulton D, Husain S. Altered penile vascular reactivity and erection in the Zucker obese-diabetic rat. J Sex Med. 2007;4(2):348–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00439.x. discussion 362-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vernet D, Cai L, Garban H, et al. Reduction of penile nitric oxide synthase in diabetic BB/WORdp (type I) and BBZ/WORdp (type II) rats with erectile dysfunction. Endocrinology. 1995;136(12):5709–17. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.12.7588327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jesmin S, Sakuma I, Salah-Eldin A, et al. Diminished penile expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors at the insulin-resistant stage of a type II diabetic rat model: a possible cause for erectile dysfunction in diabetes. J Mol Endocrinol. 2003;31(3):401–18. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0310401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gur S, Kadowitz PJ, Hellstrom WJ. A critical appraisal of erectile function in animal models of diabetes mellitus. Int J Androl. 2009;32(2):93–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2008.00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiou WF, Liu HK, Juan CW. Abnormal protein expression in the corpus cavernosum impairs erectile function in type 2 diabetes. BJU Int. 2010;105(5):674–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang M, Lv XY, Li J, et al. The characterization of high-fat diet and multiple low-dose streptozotocin induced type 2 diabetes rat model. Exp Diabetes Res. 2008;2008:704045. doi: 10.1155/2008/704045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Srinivasan K, Viswanad B, Asrat L, et al. Combination of high-fat diet-fed and low-dose streptozotocin-treated rat: a model for type 2 diabetes and pharmacological screening. Pharmacol Res. 2005;52(4):313–20. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prentki M, Nolan CJ. Islet beta cell failure in type 2 diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(7):1802–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI29103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miner MM, Sadovsky R. Evolving issues in male hypogonadism: evaluation, management, and related comorbidities. Cleve Clin J Med. 2007;74(Suppl 3):S38–46. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.74.suppl_3.s38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brunetti P. The lean patient with type 2 diabetes: characteristics and therapy challenge. Int J Clin Pract Suppl. 2007;(153):3–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Podlasek CA, Zelner DJ, Bervig TR, et al. Characterization and localization of nitric oxide synthase isoforms in the BB/WOR diabetic rat. J Urol. 2001;166(2):746–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia MM, Fandel TM, Lin G, et al. Treatment of erectile dysfunction in the obese type 2 diabetic ZDF rat with adipose tissue-derived stem cells. J Sex Med. 2010;7(1 Pt 1):89–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01541.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otero K, Martinez F, Beltran A, et al. Albumin-derived advanced glycation end-products trigger the disruption of the vascular endothelial cadherin complex in cultured human and murine endothelial cells. Biochem J. 2001;359(Pt 3):567–74. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3590567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim SC, Seo KK, Kim HW, et al. The effects of isolated lipoproteins and triglyceride, combined oxidized low density lipoprotein (LDL) plus triglyceride, and combined oxidized LDL plus high density lipoprotein on the contractile and relaxation response of rabbit cavernous smooth muscle. Int J Androl. 2000;23(Suppl 2):26–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2605.2000.00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim SC. Hyperlipidemia and erectile dysfunction. Asian J Androl. 2000;2(3):161–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toma L, Stancu CS, Botez GM, et al. Irreversibly glycated LDL induce oxidative and inflammatory state in human endothelial cells; added effect of high glucose. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;390(3):877–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.10.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aversa A, Bruzziches R, Francomano D, et al. Endothelial dysfunction and erectile dysfunction in the aging man. Int J Urol. 2010;17(1):38–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2009.02426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu ZS, Fu Q, Zhao ST, et al. Effect of diabetes and insulin treatment on nitric oxide synthase content in rat corpus cavernosum. Asian J Androl. 2001;3(2):139–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cellek S, Rodrigo J, Lobos E, et al. Selective nitrergic neurodegeneration in diabetes mellitus - a nitric oxide-dependent phenomenon. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;128(8):1804–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kovanecz I, Ferrini MG, Vernet D, et al. Pioglitazone prevents corporal veno-occlusive dysfunction in a rat model of type 2 diabetes mellitus. BJU Int. 2006;98(1):116–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen ZJ, Zhou XL, Lu YL, et al. Effect of androgen deprivation on penile ultrastructure. Asian J Androl. 2003;5(1):33–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonzalez-Cadavid NF. Mechanisms of penile fibrosis. J Sex Med. 2009;6(Suppl 3):353–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahn GJ, Sohn YS, Kang KK, et al. The effect of PDE5 inhibition on the erectile function in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17(2):134–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moreland RB. Pathophysiology of erectile dysfunction: the contributions of trabecular structure to function and the role of functional antagonism. Int J Impot Res. 2000;12(Suppl 4):S39–46. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei P, Lane PH, Lane JT, et al. Glomerular structural and functional changes in a high-fat diet mouse model of early-stage Type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2004;47(9):1541–9. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1489-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ha TS, Hong EJ, Ahn EM, et al. Regulation of type IV collagen alpha chains of glomerular epithelial cells in diabetic conditions. J Korean Med Sci. 2009;24(5):837–43. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2009.24.5.837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]