Abstract

The goal of this study was to examine the role of rejection sensitivity in the relationship between social anxiety and body dysmorphic concerns. To test our hypothesis that rejection sensitivity mediates the link between social anxiety and body dysmorphic concerns, we administered self-report questionnaires to 209 student volunteers. Consistent with our prediction, rejection sensitivity partially mediated the relationship between social anxiety symptoms and body dysmorphic concerns. The implications of the overlap between these constructs are discussed.

Keywords: Dysmorphic Concern, Social Anxiety, Rejection Sensitivity

Introduction

Body dysmorphic concerns are characterized by preoccupations with one’s physical appearance as being extremely ugly or flawed, in the absence of a real, physical deformity or anomaly. Although this construct has been described in the literature for centuries, it has only recently begun to receive greater empirical attention (Phillips, 2005). This concern manifests in persistent thoughts about one’s physical appearance, as well as time-consuming behaviors to hide, fix, or check one’s appearance (Phillips, Menard, Fay, & Weisberg, 2005). As a result of perceiving appearance flaws as a physical problem, individuals with body dysmorphic concerns often present to medical professionals (e.g., cosmetic surgeons, dermatologists) to improve or correct their appearance (Crerand, Phillips, Menard, & Fay, 2005).

People with body dysmorphic concerns often avoid social situations (Phillips, 2005). Social avoidance is also a prominent and characteristic feature of people with high social anxiety (Hofmann, 2007). Indeed, research suggests that social anxiety and body dysmorphic concerns are highly overlapping constructs (Coles et al., 2006; Fang & Hofmann, 2010; Kelly, Walters, & Phillips, 2010). Studies have demonstrated that individuals who report having body dysmorphic concerns also endorse high social anxiety (Coles et al., 2006). Both constructs are related to a fear of negative evaluation, as well as negative self-focused thoughts, such as being inadequate or worthless (Phillips et al., 2010). Consistent with having negative beliefs about themselves, individuals with social anxiety and body dysmorphic concerns tend to be biased to interpret ambiguous social situations in a negative manner, even when positive or neutral interpretations are available (Amir, Foa, & Coles, 1998; Buhlmann et al., 2002). Furthermore, evidence suggests that thoughts of reference are common to individuals with heightened social anxiety, as well as individuals with heightened body dysmorphic concerns (Meyer & Lenzenweger, 2009; Phillips, 2004). For example, people with high social anxiety and body dysmorphic concerns both tend to perceive others as talking about them in a mocking manner. These similarities may point to low insight as a common shared aspect of the two constructs (Fang & Hofmann, 2010). Thus, there appears to be empirical support for the notion that social anxiety and body dysmorphic concerns may be highly related constructs.

Despite existing research suggesting that social anxiety and body dysmorphic concerns are overlapping, these two constructs also show important differences. One major difference is that body dysmorphic concerns are usually characterized by compulsive behaviors (i.e. to check one’s physical appearance), which are not typically found in individuals with sole social anxiety concerns (Phillips, 2005; Phillips et al., 2010). Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that body dysmorphic concern may only be strongly associated with a fear of negative evaluation regarding physical appearance (Phillips, 2005). Therefore, more research is needed to clarify the similarities and differences between these related constructs.

It has been suggested that rejection sensitivity may be associated with both social anxiety and body dysmorphic concerns (Coles et al., 2006). The purpose of the current study was to investigate the role of rejection sensitivity, as one potential mechanism by which social anxiety and body dysmorphic concerns may be associated. Rejection sensitivity refers to a sense of personal inadequacy and misinterpretation of the behavior of others, which contributes to fear and discomfort when rejection is perceived (Harb, Heimberg, Fresco, Schneier, & Liebowitz, 2002). This construct is closely related to a fear of negative evaluation by others and a fear of embarrassment, which are the primary shared features between social anxiety concerns and body dysmorphic concerns. However, rejection sensitivity is distinguishable from fear of negative evaluation in that the latter refers to a broader construct related to anxious apprehension of others’ evaluations (Watson & Friend, 1969), rather than a specific concern about anticipating rejection from others, which better characterizes the former. Although data show that heightened rejection sensitivity is associated with social anxiety and body dysmorphic concern as independent constructs (Calogero, Park, Rahemtulla, & Williams, 2010; Harb et al., 2002; Phillips, Nierenberg, Brendel, & Fava, 1996), studies have not yet investigated whether rejection sensitivity serves as a link between the two constructs.

Specifically, the current study had the following aims. First, we examined whether social anxiety is associated with body dysmorphic concerns after controlling for rejection sensitivity. Second, we examined whether rejection sensitivity mediated the relationship between social anxiety and body dysmorphic concerns. Consistent with previous research (Calogero et al., 2010; Harb et al., 2002), we hypothesized that rejection sensitivity would be positively associated with body dysmorphic concerns, and that social anxiety would remain to be significantly associated with body dysmorphic concerns, even after controlling for rejection sensitivity. In other words, we predicted that rejection sensitivity would partially mediate the relationship between social anxiety and body dysmorphic concerns.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 218 undergraduate students. Each participant received course credit for experimental participation as part of an introductory psychology course. The study was approved by the university’s departmental Institutional Review Board. Participants gave written informed consent for participation in the study before completing a battery of self-report questionnaires.

Measures

Several measures assessing for social anxiety, body dysmorphic symptoms, and rejection sensitivity, including the Body Dysmorphic Disorder-Symptom Scale (BDD-SS), Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS; Liebowitz, 1987), and Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire (RSQ; Downey & Feldman, 1996), were administered as part of a larger battery of self-report questionnaires.

The BDD-SS (Wilhelm, 2006; Wilhelm, Phillips, & Steketee, in press) measures the presence, frequency, and distress of BDD-related symptoms (thoughts and behaviors) in the past week. It classifies symptom severity into seven symptom clusters. Each symptom item is scored as a binary variable (yes or no), and each symptom cluster yields a separate severity score, which is based on a 10-point Likert scale. The seven clusters of symptoms include: checking and comparing; fixing and correcting; avoiding and hiding; weight and shape concerns; skin picking and hair pulling; seeking cosmetic surgery; and beliefs about appearance. The BDD-SS has promising psychometric properties, which are reported elsewhere (Wilhelm, 2006; Wilhelm, Phillips, & Steketee, in press). Based on the sample in our study, the BDD-SS had strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .88).

The LSAS is a 24-item scale that assesses fear and avoidance on 11 social interactional and 13 performance situations in the past week (Liebowitz, 1987). In this study, participants completed the self-report version of the scale. The self-report version of the scale has shown good test-retest reliability, high internal consistency, and good convergent and discriminant validity (Baker, Heinrichs, Kim, & Hofmann, 2002; Fresco et al., 2001). In addition, Baker et al. (2002) reported that the scale was sensitive to treatment change. The LSAS-SR fear scale has also been demonstrated to have excellent internal consistency (α = .94) (Fresco et al., 2001).

The RSQ is a self-report measure used to assess rejection sensitivity in two separate components: level of anxiety and concern as well as expectations of rejection, for 18 interpersonal situations (Downey & Feldman, 1996). The 18 interpersonal situations assessed on the RSQ are scored by multiplying the level of rejection concern by the reverse of the level of expectation for acceptance or rejection for each item. Taking the mean of the resulting 18 scores produces an overall rejection sensitivity score ranging from 1 (low rejection sensitivity) to 36 (high rejection sensitivity).

Data Analysis

Of the 218 subjects in our original sample, 9 subjects were excluded from analysis due to missing data in amounts rendering them inappropriate for further analysis. The final sample, therefore, consisted of 209 subjects. Of the remaining 209 subjects, 7 subjects had missing data. Missing values ranged from 1 to 6 for each subject, with two subjects missing one data point, two subjects missing two data points, two subjects missing four data points, and one subject missing six data points. Multiple imputation was used to impute the remaining missing data points (Rubin, 1987).

Bivariate correlations were conducted to examine the relationships between social anxiety symptoms, body dysmorphic symptoms, and rejection sensitivity. Partial correlations were used to examine the association between social anxiety and body dysmorphic symptoms after controlling for gender and rejection sensitivity.

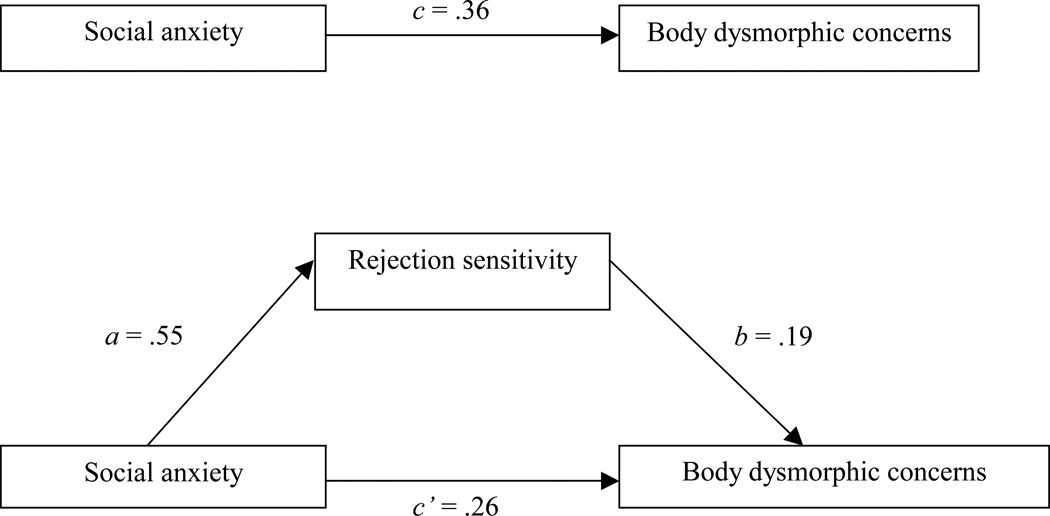

A mediational analysis was conducted to investigate whether rejection sensitivity mediated the relationship between social anxiety and body dysmorphic symptoms. According to the procedure outlined by Baron and Kenny (1986), the mediational role of rejection sensitivity was demonstrated by testing the following four conditions: 1) effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, 2) effect of the independent variable on the proposed mediator, 3) effect of the proposed mediator on the dependent variable, after controlling for the independent variable, and 4) effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, after controlling for the proposed mediator (see Figure 1). In addition, the mediational effect was examined using MacKinnon, Fritz, Williams, & Lockwood’s (2007) procedure for determining the confidence intervals for the indirect effect. This procedure was conducted using the PRODCLIN Program.

Figure 1.

Mediation involved testing the following relationships: Paths a (predictor [Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale; LSAS] to mediator [Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire; RSQ]), b (mediator to outcome [Body Dysmorphic Disorder Symptom Scale, beliefs about appearance cluster; BDD-SS] when controlling for the predictor), c (predictor to outcome), and c’ (predictor to outcome when controlling for the mediator). Mediation is demonstrated if path c’ is no longer significant (full mediation), or significantly reduced when controlling for the mediator (partial mediation).

Results

The mean age of the sample was 18.78 years (SD = 0.93, range = 18–22 years), consisting primarily of females (N = 155, 74.2%). The sample was racially and ethnically diverse. The mean overall score on the BDD-SS was 20.25 (SD = 15.29). The mean total score on the LSAS was 40.80 (SD = 21.07). The mean total score on the RSQ was 9.41 (SD = 3.37). Table 1 displays demographic characteristics of the sample.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics for the Overall Sample

| Age | 18.78 years (SD = 0.93) |

| Sex | 74.20% female |

| Ethnicity | 28.7% ethnic minority |

| African American | N = 4 (1.9%) |

| Asian | N = 33 (15.8%) |

| Caucasian | N = 149 (71.3%) |

| Hispanic | N = 12 (5.7%) |

| Indian | N = 6 (2.9%) |

| Other | N = 5 (2.4%) |

The relationship between social anxiety and body dysmorphic concerns was examined by using Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient. LSAS and BDD-SS scores were found to be moderately correlated (r = .36, n = 209, p < .001), suggesting that social anxiety symptoms were positively associated with body dysmorphic concerns. Partial correlation was used to examine the relationship between LSAS and BDD-SS scores, while controlling for rejection sensitivity and gender. There was a significant positive correlation between social anxiety and body dysmorphic symptoms, after controlling for rejection sensitivity (r = .23, n = 209, p < .01) and gender (r = .35, n = 209, p < .001).

Standard regressions were conducted to examine whether rejection sensitivity mediated the association between social anxiety and body dysmorphic concerns. When conducting the analysis using total scores on the BDD-SS, rejection sensitivity partially mediated social anxiety and body dysmorphic symptoms (Table 2). The Sobel test of significance for the indirect effect indicated that RSQ scores significantly mediated the relation between LSAS and BDD-SS scores (z = 2.39, p < .05). The mediational effect was also examined using the PRODCLIN Program (MacKinnon et al., 2007). Results showed that the indirect effect was significant, as the confidence interval did not include 0 [.016–.140].

Table 2.

Summary of Regression Analyses Testing for Mediation (N = 209)

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable(s) | B | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rejection sensitivity | Social anxiety | .55 | 9.54*** |

| Body dysmorphic concerns | Social anxiety | .36 | 5.55*** |

| Body dysmorphic concerns | Social anxiety1 | .26 | 3.32** |

| Body dysmorphic concerns | Rejection sensitivity2 | .19 | 2.47* |

After controlling for rejection sensitivity;

After controlling for social anxiety symptoms

p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05.

When conducting the analysis separately for each body dysmorphic symptom cluster, rejection sensitivity partially mediated the relationship between social anxiety and body dysmorphic concerns, for the following symptom clusters: checking and comparing, avoiding and hiding, and beliefs about appearance, but not for any other clusters. The Sobel test of significance for the indirect effect indicated that RSQ scores significantly mediated the relation between LSAS and BDD-SS cluster scores (checking and comparing: z = 2.34, p < .05; avoiding and hiding: z = 2.13, p < .05; beliefs about appearance: z = 4.03, p < .001). Using the PRODCLIN Program, results showed that the indirect effect was significant for each of these three domains, as the confidence intervals did not include 0 (checking and comparing: CI=.014–.138; avoiding and hiding: CI=.007–.131; beliefs about appearance: CI=.073–.205).

A reverse mediational analysis was conducted by reversing the proposed mediator with the dependent variable. Results showed that body dysmorphic symptoms were a significant mediator of social anxiety and rejection sensitivity. The Sobel test of significance showed that the indirect effect was significant (z = 2.17, p < .05). The PRODCLIN Program also revealed that the indirect effect was significant (CI=.007–.082). Separate Sobel tests were also conducted for the BDD-SS symptom clusters that were significantly partially mediated by RSQ scores. All three Sobel tests, as well as all three tests using PRODCLIN, indicated that the indirect effects were also significant. Therefore, the reverse mediations yielded models that also accounted for the data.

Discussion

Consistent with our hypothesis, rejection sensitivity partially mediated the relationship between social anxiety and body dysmorphic concerns. This suggests that rejection sensitivity may provide a mechanism by which the two constructs are related.

It is noteworthy that the partial mediation was only significant for the body dysmorphic symptom clusters pertaining to checking and comparing, avoiding and hiding, and beliefs about appearance, and not for any of the other symptom clusters, which pertain to specific domains of appearance concerns (e.g., weight/shape, skin picking/hair pulling, seeking cosmetic surgery). This suggests that the thoughts and behaviors related to appearance concerns are specific to the relationship between social anxiety and body dysmorphic concerns, and rejection sensitivity may be particularly related to the cognitive aspects of dysmorphic concern. The fact that the reverse mediation also resulted in a significant effect suggests that rejection sensitivity and appearance-related thoughts and behaviors may have a reciprocal relationship. Previous research shows that in patients who suffer from SAD as well as BDD social anxiety usually precedes the onset of dysmorphic concerns (Wilhelm, Otto, Zucker, & Pollack, 1997), which begs the question of whether the early presence of heightened rejection sensitivity or fear of negative evaluation provides a course for the later development of dysmorphic concerns. Prospective studies should examine the temporal relationship between these constructs in order to elucidate the question of causality.

The conceptualization of body dysmorphic concern is a source of debate in the literature, as researchers have drawn parallels between body dysmorphic concerns and many other constructs including body image concerns, psychotic or delusional concerns, and obsessive-compulsive concerns (Chosak et al., 2008; Cororve & Gleaves, 2001; Phillips et al., 1995). Previous research has found abundant evidence for the conceptual overlap between body dysmorphic and obsessive-compulsive concerns based on similarities in intrusive appearance-related cognitions and ritualized compulsive mirror checking behavior that is commonly observed in individuals with body dysmorphic concerns (Mataix-Cols, Pertusa, & Leckman, 2007). Our findings suggest that dysmorphic concerns may be highly associated with socially anxious concerns, although it remains unclear whether the role of rejection sensitivity is specific to the relationship between body dysmorphic and social anxiety symptoms. Future research should compare individuals with dysmorphic concern, socially anxious concerns, and obsessive-compulsive concerns to determine if sensitivity to rejection is a distinguishing feature of the relationship between social anxiety and body dysmorphic concerns, or shared more broadly among individuals who are highly anxious. Furthermore, other constructs besides rejection sensitivity may provide a link between the two constructs. Gender, for example, may be a defining feature of this relationship, as people with high dysmorphic concern and social anxiety tend to be slightly more common among females (Fang & Hofmann, 2010). Further research should investigate other potential constructs that may play a role in this relationship, such as heightened fear of negative evaluation, negative affect, or self-focused attention. Closer examination of this relationship can yield important information regarding mediating and moderating factors, as well as underlying latent factors that may explain their conceptual overlap.

There are certain limitations to this study that warrant attention. First and foremost, our sample consisted of undergraduate students. Therefore, it is uncertain whether our findings also apply to a clinical population. Secondly, the current study could not determine the direction of the relationship between social anxiety, body dysmorphic concerns, and rejection sensitivity because it did not account for the temporal precedence of these variables. Future research should therefore address causality to better understand the ways in which these constructs are related through longitudinal and experimental data. Furthermore, the reliance on a limited set of self-report instruments at the exclusion of other methods of assessment may limit the convergent validity of the study, as well as the objectivity of the data. However, these limitations notwithstanding, this study fills in one specific gap in the relatively scant literature on the relationship between social anxiety and body dysmorphic concerns.

Research Highlights.

Social anxiety and body dysmorphic concerns are highly related constructs.

Rejection sensitivity mediates the link between social anxiety and body dysmorphic concerns.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Amir N, Foa EB, Coles ME. Negative interpretation bias in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1998;36:945–957. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker SL, Heinrichs N, Kim HJ, Hofmann S. The Liebowitz social anxiety scale as a self-report instrument: a preliminary psychometric analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2002;40:701–715. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brawman-Mintzer O, Lydiard RB, Phillips KA, Morton A. Body dysmorphic disorder in patients with anxiety disorders and major depression: A comorbidity study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:1665–1667. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.11.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhlmann U, Wilhelm S, McNally RJ, Tuschen-Caffier B, Baer L, Jenike MA. Interpretive biases for ambiguous information in body dysmorphic disorder. CNS Spectrums. 2002;7:435–443. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900017946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calogero RM, Park LE, Rahemtulla ZK, Williams KCD. Predicting excessive body image concerns among British University students: The unique role of appearance-based rejection sensitivity. Body Image. 2010;7:78–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chosak A, Marques L, Greenberg JL, Jenike E, Dougherty DD, Wilhelm S. Body dysmorphic disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: Similarities, differences and the classification debate. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 2008;8:1209–1218. doi: 10.1586/14737175.8.8.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles ME, Phillips KA, Menard W, Pagano ME, Fay C, Weisberg RB, et al. Body dysmorphic disorder and social phobia: Cross-sectional and prospective data. Depression and Anxiety. 2006;23:26–33. doi: 10.1002/da.20132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cororve MB, Gleaves DH. Body dysmorphic disorder: A review of conceptualizations, assessment, and treatment strategies. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21:949–970. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(00)00075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crerand CE, Phillips KA, Menard W, Fay C. Nonpsychiatric medical treatment of body dysmorphic disorder. Psychosomatics: Journal of Consultation Liaison Psychiatry. 2005;46:549–555. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.46.6.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Feldman SI. Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:1327–1343. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.6.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang A, Hofmann SG. Relationship between social anxiety disorder and body dysmorphic disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:1040–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fresco DM, Coles ME, Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hami S, Stein MB, Goetz D. The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale: A comparison of the psychometric properties of self-report and clinician-administered formats. Psychological Medicine. 2001;31:1025–1035. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harb GC, Heimberg RG, Fresco DM, Schneier FR, Liebowitz MR. The psychometric properties of the Interpersonal Sensitivity Measure in social anxiety disorder. Behaviour research and therapy. 2002;40:961–980. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00125-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG. Cognitive factors that maintain social anxiety disorder: A comprehensive model and its treatment implications. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2007;36:193–209. doi: 10.1080/16506070701421313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MM, Walters C, Phillips KA. Social anxiety and its relationship to functional impairment in body dysmorphic disorder. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41:143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebowitz MR. Social phobia. Modern Problems in Pharmacopsychiatry. 1987;22:141–173. doi: 10.1159/000414022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:384–389. doi: 10.3758/bf03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mataix-Cols D, Pertusa A, Leckman JF. Issues for DSM-V: How should obsessive-compulsive and related disorders be classified? American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1313–1314. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07040568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer EC, Lenzenweger MF. The specificity of referential thinking: a comparison of schizotypy and social anxiety. Psychiatry Research. 2009;165:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KA. Psychosis in body dysmorphic disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2004;38:63–72. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(03)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KA. The broken mirror: Understanding and treating body dysmorphic disorder. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. (revised and expanded ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KA, McElroy SL, Hudson JI, Pope HG. Body dysmorphic disorder: An obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorder, a form of affective spectrum disorder, or both? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1995;56:41–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KA, Menard W, Fay C, Weisberg R. Demographic characteristics, phenomenology, comorbidity, and family history in 200 individuals with body dysmorphic disorder. Psychosomatics. 2005;46:317–325. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.46.4.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KA, Nierenberg AA, Brendel G, Fava M. Prevalence and clinical features of body dysmorphic disorder in atypical major depression. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1996;184:125–129. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199602000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KA, Stein DJ, Rauch SL, Hollander E, Fallon BA, Barsky A, et al. Should an obsessive-compulsive spectrum grouping of disorders be included in DSM-V? Depression and Anxiety. 2010;27:528–555. doi: 10.1002/da.20705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: J. Wiley & Sons.; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Friend R. Measurement of social-evaluative anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1969;33:448–457. doi: 10.1037/h0027806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm S. Feeling good about the way you look: A program for overcoming body image problems. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm S, Otto MW, Zucker BG, Pollack MH. Prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder in patients with anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1997;11:499–502. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(97)00026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm S, Phillips KA, Steketee G. A cognitive behavioral treatment manual for body dysmorphic disorder. New York: Guilford Press; (in press) [Google Scholar]