Abstract

Purpose

To describe the process by which childhood adversity influences the life course of survivors of childhood sexual abuse.

Design

A community-based, qualitative, grounded theory design.

Methods

In this grounded theory study, data were drawn from open-ended interviews conducted as part of a larger study of women's and men's responses to sexual violence. The current study examines the experiences of 48 female and 40 male survivors of childhood sexual abuse and family adversity. Data were analyzed using the constant comparison method.

Findings

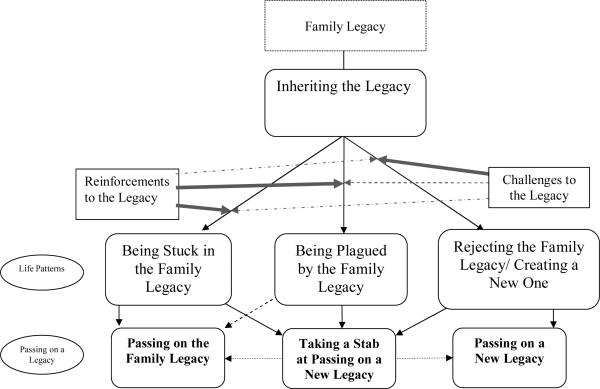

The participants described a sense of inheriting a life of abuse and adversity. The process by which childhood adversity influences the life course of adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse is labeled Living the Family Legacy. The theory representing the process of Living the Family Legacy includes three major life patterns: (a) Being Stuck in the Family Legacy, (b) Being Plagued by the Family Legacy, and (c) Rejecting the Family Legacy/Creating a New One. Associated with these life patterns are three processes by which the participants passed on a legacy to others, often their children: (a) Passing on the Family Legacy, (b) Taking a Stab at Passing on a New Legacy, and (c) Passing on a New Legacy.

Conclusions

The legacy of abuse and adversity has a profound effect on the lives of survivors of childhood sexual abuse. There are several trajectories by which the influence of childhood adversity unfolds in the lives of adult survivors and by which the legacy is passed on to others.

Clinical Relevance

The model representing the theoretical process of Living the Family Legacy can be used by clinicians who work with survivors of childhood sexual abuse and childhood adversity, especially those who have parenting concerns.

Keywords: Childhood sexual abuse, parenting, family adversity, grounded theory

Childhood sexual abuse (CSA) is a prevalent social and public health problem. The American Medical Association (2003) defines CSA as “the engagement of a child in sexual activities for which the child is developmentally unprepared and cannot give consent” (p. 5). According to the World Health Organization (2002), CSA is a worldwide problem with 25% of females and 8% of males reporting experiencing sexual abuse before the age of 18. As CSA often goes unreported, the actual incidence of CSA is thought to be much higher than that reported by governmental agencies (Russell & Bolen, 2000). For both women and men, a history of childhood sexual abuse is associated with a variety of short- and long-term psychological, social, behavioral, and health-related effects (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2007; Dube et al., 2005).

Children who are sexually abused, whether the abuse is intra- or extra-familial, frequently grow up in adverse family environments. CSA often co-occurs with physical or emotional abuse or neglect; parental problems with substance abuse, mental illness, economic instability, or domestic violence; and maladaptive family functioning, such low levels of cohesiveness and high levels of conflict (Dong et al., 2004; Gold, Hyman, & Andrés-Hyman, 2004; Higgins & McCabe, 2003). Survivors of CSA often report that in their families the abuse was often minimized, denied, or blamed on the child (Dunlap, Golub, & Johnson, 2003).

The role of family dysfunction and other types of abuse as the cause of later negative outcomes in survivors of CSA has been debated. In some studies, pathogenic family variables have been shown to be better predictors of adult disturbance than sexual abuse variables (Higgins & McCabe, 2003), whereas in other studies sexual abuse has been shown to be associated with negative long-term effects beyond those accounted for by family environment (Roesler & McKenzie, 1994). While the co-occurrence of multiple types of abuse seems to increase the risk of adult disturbance, the severity of abuse has been shown to be a stronger predictor of trauma symptoms in adults (Clemmons, Walsh, DiLillo, & Messman-Moore, 2007).

One area of functioning that is particularly likely to be affected by an adverse family environment is how survivors parent their children. Researchers have found that parenting problems of adult survivors of CSA include failure to establish clear generational boundaries, inadequate monitoring and supervision, and the use of harsh or inconsistent discipline (Banyard, Williams, & Siegel, 2003; DiLillo & Damashek, 2003). Experts caution, however, that the relationship between sexual abuse, childhood adversity, and parenting difficulties is complex and may be mediated by factors such as the mental health concerns, substance abuse, and domestic violence experienced by the adult survivor (Banyard et al.; Locke & Newcomb, 2004; Schuetze & Eiden, 2005).

While the influence of negative family characteristics on the later functioning of adult survivors of CSA has been examined, few studies (Dunlap et al., 2003) have explored how these characteristics shape the life course of survivors, especially from their own perspectives. Most researchers have attempted to isolate and measure types of childhood maltreatment and family characteristics and determine how they correlate with indices of adult psychopathology (DiLillo & Damashek, 2003). The complex processes by which the influences of adverse family experiences unfold through adulthood have not been explored in-depth. The purpose of this study, therefore, is to describe the process by which childhood adversity influences the life course of adult survivors of CSA from their perspectives.

Methods

Data are drawn from an on-going qualitative, community-based study aimed at developing a theoretical framework to describe, explain, or predict women's and men's responses to sexual violence. For the larger study, 121 women and men were recruited from several socioeconomically diverse communities in the metropolitan area of a mid-size city in Midwest United States. Participants were included in the larger study if they had experienced sexual violence at anytime in their lives. Research associates placed announcements throughout the communities and networked with community leaders and residents, who then promoted the study in a variety of settings, including churches, community agencies, and neighborhood centers (Martsolf, Courey, Chapman, Draucker, & Mims, 2006). Interested individuals called a toll-free line and were screened by advanced-practice mental health nurses using a script of questions designed by the researchers to detect acute emotional distress that would make participation risky. Those who met inclusion criteria were scheduled for an interview if appropriate. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained and participants signed consent forms.

Advanced-practice psychiatric/mental health nurse research associates conducted open-ended, face-to-face interviews that lasted one to two hours. Participants were asked to describe (a) the sexual violence they had experienced, (b) how they managed following the violence, (c) how the violence affected their lives, and (d) how they healed, coped, or recovered from the violence. Participants were paid $35.00 for each interview to compensate for their time and transportation costs. Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed. Data were collected over a 17-month period from December 2004 to April 2006. Pseudonyms are used in this article to protect the identity of the participants and others they discuss. Quotation marks are used to reflect the verbatim words of the participants.

Grounded theory methods (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), which focus on the complexities of people undergoing change and the influence of social interactions on outcomes (Benoliel, 1996), were used for both the larger and the current study. The aim of grounded theory is to identify common psychosocial processes used by people who share a life challenge (Glaser & Strauss). The choice of grounded theory for the current study was based on the researchers' belief that the ways in which childhood adversity influence the life course of adult survivors of CSA are complex processes that change over time and are influenced by both psychological and social factors.

Sample

For this study, a sub-sample of participants was selected from the 121 participants of the larger study. Inclusion criteria for this study were having had (a) an experience of CSA (as defined above) and (b) a childhood family environment that was aversive. Adversity could include: (i) physical or emotional abuse or neglect, (ii) domestic violence, (iii) disturbed, chaotic, or non-nurturing family interactions, or (iv) other indices of family dysfunction, including parental substance abuse, mental illness, or imprisonment.

Eighty-eight (88) participants from the larger study met criteria for this study. The sample included 48 women and 40 men who experienced both CSA and family adversity. Ages ranged from 19 to 62 years. Thirty-eight (38) of the participants were African American, 36 were Caucasian, 1 was Asian, 1 was Hispanic, 4 were more than one race, and 8 did not report race. Forty-eight (48) of the participants reported an income under $10,000; 17 between $10,000 and $30,000; 10 between $30,000 and $50,000; 7 above $50,000; and 6 did not report income. Thirty-two (32) participants had no children, 20 had 1 child, 12 had 2 children, 21 had more than 2 children (the most reported was 8). Three did not report number of children.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed by the research team using constant comparison techniques as described by Schreiber (2001). Constant comparison techniques involve comparing coded data with other data and with developing concepts through each of three levels of data analysis as described below. The theoretical constructs that serve as the basis for the theory presented in this article emerged as the team analyzed data for the larger study. Living the Family Legacy, therefore, is one of several theories that were developed from the data set of the larger project.

Three levels of coding were used to develop the theory for this study. First-level coding is a line-by-line examination of the data (Schreiber, 2001). During the first-level coding of transcripts for the larger study, the team noted that many participants, especially those whose sexual violence occurred during childhood, spoke as much - or more - about problems with how they were “raised” as they did about the sexual abuse itself. They described family environments characterized by parental maltreatment including harsh discipline, chaotic living situations, lack of nurturance, and lack of support for revealing, stopping, and/or healing from the abuse.

Because much data was coded to parenting, the team determined that parenting was an emerging category. Second-level coding, the comparison of first-level codes with existing and new data (Schreiber, 2001), was conducted to create increasingly more abstract categories. As this process progressed, the team broadened the parenting category to create categories related to any adversity in the family-of-origin and its effects and began to hypothesize how these categories were related. The team determined that these categories were most applicable to those with CSA experiences, and thus these participants became the sample for the current study.

Third-level coding, the exploration of the relationship among categories, was conducted on selected transcripts of survivors of CSA to determine whether the hypotheses and the emerging theory were supported. Theoretical sampling principles (Draucker, Martsolf, Ross, & Rusk, 2007) guided the selection of transcripts for third-level coding. Transcripts were selected that were information-rich (i.e., had much data related to the emerging theory), typical (i.e., were common manifestations of the theory), deviant (i.e., seemed to be inconsistent with the theory), extreme (i.e., had intense manifestations of the theory), and theoretically relevant (i.e., were illustrative of the construct of legacy). A close examination of these transcripts resulted in the refinement of the theory. Grounded theory strategies of memoing (i.e., tracking analytic decisions), diagramming (i.e., depicting the proposed relationships among variables), and member checks (i.e., validating emerging constructs with subsequent participants) were used to enhance the credibility of the theory (Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Schreiber, 2001).

The Theory: Living the Family Legacy

The data revealed that the participants had a sense that they had inherited a life of adversity and abuse. They inherited this life not only from their parents or parent surrogates, but also from other family members - including ancestors whom they had never met. The inheritance included memories of traumatic events, vulnerabilities to further maltreatment, and ways of life that reflected those in their families-of-origin. The concept of a legacy was therefore used to reflect the participants' sentiments that the inheritance came from several generations back, was something they carried with them to adulthood, and was something they could pass on to others, especially their children. The researchers therefore labeled the process by which childhood adversity influences the life course of adult survivors of CSA as Living the Family Legacy. A model depicting the process of Living the Family Legacy, which includes three life patterns and three ways of passing on a legacy, is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Living the Family Legacy

Inheriting the Legacy

Participants described an entire gamut of abuse and adverse experiences in their families-of-origin. The abuse was perpetrated by parents, step-parents, primary caretakers, grandparents, siblings, aunts, uncles, and cousins. Many participants had experienced several types of severe abuse. Stuart, a man who had experienced sexual abuse and beatings by his stepmother, revealed, “She'd lock me in cubbyholes, up in our attic, and sit in front of the door, to where I couldn't get out of it.” Others described physical and emotional neglect; parental substance abuse, mental illness, imprisonment, absence, and domestic violence; and/or disturbed family interactions, such as rigid control of children's activities or a high degree of conflict. For some, family life was chaotic. For others, the family environment was marked by a lack of supervision and an absence of nurturance. Randy was a 38-year-old who had engaged in child prostitution, dealt drugs as a school-aged child, and was raped at age 14, all without his parents' awareness. He indicated that being ignored by his father caused him the most pain. He explained, “My father and me have talked collectively – you can count on this hand, and I'm almost 40 years old. We're just like strangers. I wanted what other kids had – a conversation.”

Many participants indicated that memories of their painful childhood experiences would stay with them forever and left them particularly susceptible to on-going maltreatment or victimization. Some engaged in sexual activities at an early age because they wanted “someone to love me,” used drugs and alcohol to numb their pain, developed a poor sense of self because of how they were treated by their families, and failed to acquire the interpersonal skills or values they needed to form healthy relationships. Allison, a 25-year-old woman who experienced a lifetime of abuse, explained, “I don't get along with [others]. Being abused by my stepdad - like my conscience [sense of right and wrong] was taken away and maybe that made me more vulnerable.” Some enacted the behaviors to which they had been subjected; several who had been molested by older family members, for example, in turn abused younger family members, often their siblings.

Although the participants' childhood legacy caused them much suffering, as children they often defended or guarded their family's way of life. Many indicated it was the only life they knew and assumed it to be normal. Despite being hurt by family members, participants often attempted to protect them from attack or observation by outsiders who might intervene. In their own minds, participants relieved their families of responsibility for the adversity by concluding that the maltreatment was deserved because the participants had been bad or had “asked for it.” Participants had been afraid that if others were to become aware of “what was going on” in the household, the family would be torn apart or a family member would be punished, hurt, or taken away. Most did not tell others about the abuse or other family problems. When asked if he had told anyone of his childhood sexual abuse, Jerry, a 56-year-old man whose mother had abused drugs, responded, “Somebody outside the family? I don't know…. I guess that I just wanted to protect my family.”

Reinforcements to the Legacy

When the participants were children, adults outside the family-of-origin often facilitated or enabled the abuse or failed to help the child with his or her family problems. We refer to these interactions as reinforcements to the legacy as the actions of the adults served to perpetuate the abuse and adversity. Some reinforcements were subtle, such as when an adult ignored signs and symptoms of abuse. Other reinforcements were more overt, such as when adults told the participants that they were lying, punished them for revealing the abuse, or ignored their cries for help. Sophie, a 62-year old woman, was asked if she ever told anyone about the many times she had been sexually abused. She responded, “I think I called the police one time. I was coming from …, like the community center, and I called the police because a boy had tried to rape me and they told me I shouldn't have been out.”

Challenges to the Legacy

Some adults outside the family-of-origin tried to confront the abuse and adversity. Participants indicated that substitute parents, extended family members, family friends, neighbors, teachers, coaches, professional counselors, or church members told them the abuse was wrong, attempted to stop the abuse, and provided positive experiences to counteract the family environment. We refer to these interactions as challenges to the legacy as the adult actions were in opposition to the abuse and adversity the participants usually experienced. Joanna, a 19-year old woman who had been sexually abused by her uncle and a neighbor and physically abused by her family, described her interaction with an older neighbor: “I told Miss Sandra. Well, I actually didn't have to tell her because she saw I was hurting. She was like… `We gotta tell. We gotta tell, because it can't keep happening….'” Challenges such as this had not occurred often in the lives of the participants, however, and few adults were able to end the abuse or change family situations.

Life Patterns

Participants clearly believed that as adults the abuse and adversity they experienced in childhood continued to influence their behaviors, feelings, relationships, and plans for the future in profound ways. In the theory, the term “life patterns” is used to reflect all the facets of life that the participants indicated were affected by their childhood adversity. The data revealed three life patterns of Living the Family Legacy.

Being Stuck in the Family Legacy

Some participants described being stuck in the legacy as they continued to live with abuse and chaos very similar to their early family life and saw few possibilities for living differently. As children, their family legacy had been rarely challenged and often reinforced. The participants went on to live adult lives marked by addictions, imprisonment, prostitution, poor health, family instability, and/or experiences with interpersonal violence, both as perpetrators and victims. Jackie, a 45-year old woman who had been molested by her father, talked about how she used drugs and drinking to escape the pain. She described her life as an adult: “At one time, I got into prostitution. Drugs. Sex. I would smoke crack and feel warm. Isn't that sad? I've heard a lot of people are abused and go that way….”

Being Plagued by the Family Legacy

Many participants indicated that were functioning well “on the outside” but felt permanently bothered by the effects of their adverse childhood experiences. Unlike those who were stuck in the legacy, these participants did not endure on-going violence and chaos in their lives, but nonetheless indicated that they were plagued by their legacies. As children, their family legacy had been rarely challenged or reinforced; often others had not noticed the problems in the family. This life pattern was marked with emotional pain, including sadness, depression, and anxiety; feelings of low self-worth; and lack of trust of others. Jackson, a 48-year-old man, had been molested for over a year by a neighbor when he was 9. He said, “You put it behind you…. You block it out…. My substitute was sports…. But it made me not want to trust people. I guess the biggest thing is trust. You just don't trust people.”

Rejecting the Family Legacy and Creating a New Legacy

Some participants had rejected their family legacy and were creating a new one. Participants who described this pattern were most likely to have encountered others who challenged their family legacy. These participants were very determined to find a new way to live their lives; refused to be mistreated by others, especially by partners; and vowed to create healthy families. Many had obtained professional help to resolve the issues stemming from childhood. They were particularly concerned about finding ways to create lives free of abuse and to develop nurturing and supportive relationships. Christy, a 25-year-old woman who experienced sexual and emotional abuse as a child, discussed how she had rejected her family legacy and had learned to express love: “When you love somebody, you can do these things for somebody, like meaningful touch, just any kind of pat on the shoulder, or a hug…. You share…. I do it for my sister now.”

Passing on a Legacy

It was in the context of these life patterns that the participants talked about passing on a legacy to others. The legacy could be the family legacy of abuse and adversity or a new abuse-free legacy. The others to whom participants bequeathed the legacy were often their children, although many talked about passing on a legacy to other children or to “future generations.”

Passing on the Family Legacy

Some participants who were stuck, and a few who were plagued by, their family legacy, described passing it on, typically to their children. These participants had created family environments that were strikingly similar to those of their childhood. Many raised children in homes in which there was mental illness, drug abuse, domestic violence, criminal activity, and economic instability. Some reported having been violent or neglectful toward their children, and several indicated that their children had experienced sexual abuse similar to their own. Abigail, a 45- year-old woman, explained, “I didn't realize I was a parent until a few years ago. I knew I had kids, but to me it was never a responsibility. I left my kids with my sister and I went on my way, living my life.” Many participants who were stuck in the legacy decided not to have children as they were convinced they might abuse them. A few children of the participants had been removed from the home by protective services or raised by extended family members.

Taking a Stab at Passing on a New Legacy

Many participants, especially those who were plagued by the legacy, wished to nurture their children and to protect them from abuse. Many took a stab at leaving a new legacy as they made sincere, but ineffective, attempts to parent differently than they had been parented. Participants who took a stab at a new legacy tended to use expressions such as “I'll try to do better,” “Hopefully it will be different,” or “Maybe it won't happen to him [or her].” Some verbalized aspirations to protect their children from harm but did not take adequate measures to ensure their safety. Several expressed determination that the sexual abuse that happened to them would never happen to their children, only to later reveal that one or more of their children had, in fact, been sexually abused while in their care. Hilda, a 19-year-old woman who had experienced extensive abuse as a child, took a stab at a new legacy: “My son, he is very, very, he's not bad, but he's a very good manipulator…. I try to do [things differently] with my son because my grandmother beat me. I didn't want to have no sense of discipline with him, [so] I put him in time out.” Yet, she followed this proclamation with an account about beating her son with a belt because he had damaged her friend's wood floor.

Passing on a New Legacy

Most of the participants who had rejected the family legacy and created a new legacy wished to pass on the new legacy. Several told touching stories about absolutely refusing to hand down the legacy of abuse and adversity, especially to their children. Several were aware that the legacy was passed down from their grandparents, and participants vowed to “stop the cycle.” They sought to leave a new legacy by protecting their children from violence, decreasing their children's vulnerability to violence by ensuring they felt loved and protected, and providing a nurturing and stable environment. Christy talked about how she protected her son from his father, “They were all like … doing drugs and stuff, and he would want me to bring [my son] over there … and I told him, `No, I'm not doing that.' I stopped living this lifestyle for my son and I'm not going to take him over there.”

Several participants also talked about intervening in the lives of others' children as helping professionals, ministers, child advocates, or family friends and thereby make things better for “future generations.” Many participants became part of the study to pass on a new legacy. They hoped their stories could stop abuse and improve the lives of vulnerable children.

Trajectories of Living the Family Legacy

Figure 1 represents common life trajectories of participants who lived the family legacy. The bold arrows reflect common paths (found in the transcripts of the majority of participants) and the dashed line arrows reflect paths that were found in the data, but were not as common. Reinforcements of the legacy, for example, were common for those who were stuck in the legacy, whereas challenges to the legacy were more common for those who rejected the legacy. Similarly, while some participants who were plagued by the legacy passed the family legacy on to their children, it was more typical that they took a stab at leaving a new legacy.

Although the two-dimensional model in Figure 1 suggests that the trajectories were orderly and progressive, many participants actually described life trajectories that were complex, cyclic, regressive, and iterative. The model, therefore, leaves open the possibility of any number of trajectories. While the model suggests that one life pattern is often predominant, a survivor of childhood adversity might move from one life pattern to another. For example, one might progress from being stuck in the legacy to being plagued by the legacy. Similarly, a survivor might also move “backward” in the model, from passing on a new legacy to being plagued by the legacy following a contentious interaction with a parent. Some might take a stab at a new legacy with one child, and leave a new legacy for another.

Discussion

The concept of family legacies resonates with other work appearing in the health care literature. Boszormenyi-Nagy (1987) developed the construct of the intergenerational legacy, in which children assume obligations to their parents based on the burdens borne by parents in raising them. Plager (1999) examined how family legacies contribute to health-promoting habits in families with children of school age. Silverman, Baker, Cait, and Boerner (2002–2003) argued that children whose parents die may take on characteristics of the deceased parent to create a type of legacy. SmithBattle (2006) found that teen mothers refined, rejected, or modified family legacies of caregiving practices.

The major limitation of the current study is its retrospective design. Participants frequently recalled events that had occurred years ago, and their memories may have been clouded or distorted. Most participants, however, were able to recall their experiences in great detail, often beginning their stories with phrases such as, “I can remember it as if it were yesterday” or “I still remember to this day.” In addition, the life narratives may have been affected by how the participants were functioning at the time of the interview. Those who were depressed, for example, would be likely to tell stories through a negative lens. Nonetheless, the narratives were rich with descriptions of how the participants moved through life - from their own childhoods of adversity to their decision to participate in the interviews.

Transferability of these findings to other settings can be determined based on the description of the sample as provided above. Over one half of these participants were of lower socioeconomic status. However, the inclusion of almost equal numbers of women and men and of Caucasian and African American participants and the recruitment of participants in community settings allow for transfer of findings to a wide variety of settings.

These findings suggest several key points for nurses who provide care for survivors of CSA in any type of practice setting. In this sample, 45% of the participants were male. Thus, it is important for nurses to be aware that men experience CSA and that their narratives indicate that they often suffer lifelong social and emotional problems as a result. Both women and men in this sample shared life stories of childhood adversity and violation of generational boundaries that left them with difficulties with trusting others. Thus, nurses need to be especially careful in maintaining appropriate, clear professional boundaries with these clients and in fostering trust through use of supportive, gentle approaches (Draucker, 1999). Attentive listening and empathic responses enhance the development of these trusted professional relationships (Courey, Martsolf, Draucker, & Strickland, 2008). Survivors of CSA who told adults about the abuse were often not believed and the abuse was minimized. Thus, it is critical that nurses to whom survivors disclose their experience of CSA respond empathically by assuring clients that they are believed and taken seriously. Because these survivors experienced childhood adversity that frequently included lack of parental involvement and direction in their lives, nurses should provide guidance for making health choices without taking away the client's autonomy (Courey, et al.).

Findings from this study indicate that nurses and other health professionals who work in mental health settings with survivors of childhood adversity and sexual violence can be particularly helpful by providing challenges to the legacy of violence. The model presented in Figure 1 can be used as a tool to initiate conversations about the family legacy. Clients might trace their own trajectories on the model, thereby developing insights into how their histories contribute to their life patterns. When working with clients who are stuck in the family legacy, for example, clinicians can discuss what challenges would be needed for rejection of the family legacy. Those who are plagued by the family legacy might be especially amenable to therapeutic interventions as they suffer from the effects of their childhood, but do not experience the chaos or dysfunction of those who are stuck in the legacy. For clients who are parents, identifying their own life patterns and exploring their ways of passing on the legacy could open up discussion of new possibilities for parenting. Clients who are taking a stab at leaving a new legacy might be especially willing to try new parenting practices.

These findings suggest several avenues for further research. Studies designed to further explore relationships between adverse family environments, types of life patterns, and the ways of passing on a legacy would enhance refinements of the theory. Further development of the theory might lead to interventions that facilitate the rejection of family legacies of violence and adversity and enable clients to leave a new legacy for the next generation.

Conclusions

The processes by which childhood adversity influences the life course of adult survivors of CSA is best understood as Living the Family Legacy. Survivors of CSA described multiple trajectories that determined whether they passed on a legacy of abuse and adversity or left a new one. The trajectories are strongly influenced by others who either reinforce or challenge the family legacy. The model depicting the process of Living the Family Legacy can guide clinicians in initiating conversations about the influence of the family legacy on one's life pattern and one's parenting. The study presents numerous possibilities for further theorizing and research.

Clinical Resources

https://www.who.int/topics/child_abuse/en/

http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/childsexualabuse.html

http://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/usermanuals/sexabuse/sexabusef.cfm

Acknowledgement

This study is funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research [R01 NR08230-01 A1]. Claire B. Draucker, Principal Investigator

References

- American Medical Association Diagnostic and treatment guidelines on child sexual abuse. 2003 doi: 10.1001/archfami.2.1.19. Retrieved August 18, 2007, from http:/www.ama-assn.org/pub/upload/mm/386/childsexabuse.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Banyard VL, Williams LM, Siegel JA. The impact of complex trauma and depression on parenting: An exploration of mediating risk and protective factors. Child Maltreatment. 2003;8(4):334–349. doi: 10.1177/1077559503257106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoliel JQ. Grounded theory and nursing knowledge. Qualitative Health Research. 1996;6(3):406–428. [Google Scholar]

- Boszormenyi-Nagy I. In: Foundations of contextual therapy: Collected papers of Ivan. Boszormenyi-Nagy MD, editor. Brunner/Mazel Publishers; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Sexual Violence: Fact Sheet. 2007 Retrieved on November 7, 2007 from http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/factsheets/svfacts.htm.

- Clemmons JC, Walsh K, DiLillo D, Messman-Moore TL. Unique and combined combinations of multiple child abuse types and abuse severity to adult trauma symptomatology. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12(2):172–181. doi: 10.1177/1077559506298248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courey TJ, Martsolf DS, Draucker CB, Strickland KB. Hildegard Peplau's theory and the healthcare encounters of survivors of sexual violence. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 2008;14(2):136–143. doi: 10.1177/1078390308315613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiLillo D, Damashek A. Parenting characteristics of women reporting a history of childhood sexual abuse. Child Maltreatment. 2003;8(4):319–333. doi: 10.1177/1077559503257104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong M, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Williamson DF, Thompson TJ, Loo CM, Giles WH. The interrelatedness of multiple forms of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28:771–784. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draucker CB. The psychotherapeutic needs of women who have been sexually assaulted. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 1999;35(1):18–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.1999.tb00564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draucker CB, Martsolf DS, Ross R, Rusk TB. Theoretical sampling and category in grounded theory. Qualitative Health Research. 2007;17(1):1137–1148. doi: 10.1177/1049732307308450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Anda RF, Whitfield CL, Brown DW, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Giles WH. Long-term consequences of childhood sexual abuse by gender of victim. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;28(5):430–438. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap E, Golub A, Johnson BD. Girls' sexual development in the inner city: From compelled childhood sexual contact to sex-for-things exchanges. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2003;12(2):73–96. doi: 10.1300/J070v12n02_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine; Chicago: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Gold SN, Hyman SM, Andres-Hyman RC. Family of origin environments in two clinical samples of survivors of intra-familial, extra-familial, and both types of sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28(2004):1199–1212. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DJ, McCabe MP. Maltreatment and family dysfunction in childhood and the subsequent adjustment of children and adults. Journal of Family Violence. 2003;18(2):107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y, Guba E. Naturalistic inquiry. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Locke TF, Newcomb M. Child maltreatment, parent alcohol- and drug-related problems, polydrug problems, and parenting practices: A test of gender differences and four theoretical perspectives. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18(1):120–134. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martsolf DS, Courey TJ, Chapman TR, Draucker CB, Mims BL. Adaptive sampling: Recruiting a diverse community sample of survivors of sexual violence. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 2006;23(3):169–182. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn2303_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plager KA. Understanding family legacy in family health concerns. Journal of Family Nursing. 1999;5(1):51–71. [Google Scholar]

- Roesler TA, McKenzie N. Effects of childhood trauma on psychological functioning in adults sexually abused as children. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disorders. 1994;182:145–150. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199403000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell DEH, Bolen RM. The epidemic of rape and child sexual abuse in the United States. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber RS. The “how to” of grounded theory: Avoiding the pitfalls. In: Schreiber RS, Stern PN, editors. Using grounded theory in nursing. Springer Publishing Company; New York: NY: 2001. pp. 55–84. [Google Scholar]

- Schuetze P, Eiden RD. The relationship between sexual abuse during childhood and parenting outcomes: Modeling direct and indirect pathways. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29(6):645–659. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman PR, Baker J, Cait C, Boerner D. The effects of negative legacies on the adjustment of parentally bereaved children and adolescents. OMEGA. 2002–2003;46:335–352. [Google Scholar]

- SmithBattle L. Family legacies in shaping teen mothers' caregiving practices over 12 years. Qualitative Health Research. 2006;16:1129–1144. doi: 10.1177/1049732306290134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . World report on violence and health. Author; Geneva, Switzerland: 2002. [Google Scholar]