Abstract

Many developing countries including Cameroon have mortality patterns that reflect high levels of infectious diseases and the risk of death during pregnancy and childbirth, in addition to cancers, cardiovascular diseases and chronic respiratory diseases that account for most deaths in the developed world. Several medicinal plants are used traditionally for their treatment. In this review, plants used in Cameroonian traditional medicine with evidence for the activities of their crude extracts and/or derived products have been discussed. A considerable number of plant extracts and isolated compounds possess significant antimicrobial, anti-parasitic including antimalarial, anti-proliferative, anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetes, and antioxidant effects. Most of the biologically active compounds belong to terpenoids, phenolics, and alkaloids. Terpenoids from Cameroonian plants showed best activities as anti-parasitic, but rather poor antimicrobial effects. The best antimicrobial, anti-proliferative, and antioxidant compounds were phenolics. In conclusion, many medicinal plants traditionally used in Cameroon to treat various ailments displayed good activities in vitro. This explains the endeavor of Cameroonian research institutes in drug discovery from indigenous medicinal plants. However, much work is still to be done to standardize methodologies and to study the mechanisms of action of isolated natural products.

Keywords: medicinal plants, ethnopharmacology, Africa

Public Health Concern and Diseases in Cameroon

Health care is a basic service essential in any effort to combat poverty, and is often promoted with public funds in Africa to achieve this aim (Castro-Leal et al., 2000). Nevertheless, curative health spending is not always well targeted to the poorest, representing about 50.5% of Cameroonian (Edmondson, 2001). Many developing countries including Cameroon have mortality patterns that reflect high levels of infectious diseases and the risk of death during pregnancy and childbirth, in addition to cancers, cardiovascular diseases and chronic respiratory diseases that account for most deaths in the developed world (WHO, 2009). In Cameroon, 3 out of 20 patients are able to buy prescribed drugs in hospitals and one out of every 1000 patients are able to see a specialist. Health care activities are coordinated by the Ministry of Public Health which receives the second highest budgetary allocation per ministry each year (Speak Clear Association of Cameroon, 2004). Health facilities are either run as government services or private services managed by the various churches and other private individuals. There are also traditional doctors that play a great role as far as the provisions of health care services are concerned. The major diseases associated with high degree of risk within the population include food or waterborne diseases (bacterial and protozoal diarrhea, hepatitis A and E, and typhoid fever), vector borne diseases (malaria and yellow fever), water contact diseases (schistosomiasis), respiratory diseases (meningococcal meningitis), and animal contact diseases (rabies) (Index mundi, 2008). Very often, there is a coexistence of many infectious diseases. Ammah et al. (1999) demonstrated that high proportion of patients (33%) had malaria coexisting with typhoid (Salmonella typhimurium, Salmonella paratyphi, and Salmonella typhi infections). In the Cameroonian population, the lifetime risk of developing active tuberculosis once infected, in absence of HIV infection, is about 10%, meanwhile this increases tenfold in HIV infected individuals (Noeske et al., 2004). Malaria remains the leading cause of morbidity in Cameroon, and among the top five causes of mortality. Malaria represents approximately 45–50% of health consultations, and 23% of admissions (Edmondson, 2001). The unsatisfactory management of all diseases throughout the continent as well as in Cameroon, which allows partially treated and relapsed patients to become sequentially resistant, may play a significant role in the development of resistance for infectious diseases (Jones et al., 2008; McGaw et al., 2008). Effective treatment of diseases is challenging for various reasons, including lack of accessibility and elevated expense of drugs and low adherence owing to toxicity of second-line drugs. It is all too likely that the emergence of resistance will be experienced in the future, exhausting the current arsenal of chemical defenses at our disposal. For this purpose, new drugs are urgently needed, and research programs into alternative therapeutics including medicinal plants investigations should be encouraged.

Biodiversity and Protected Area in Cameroon

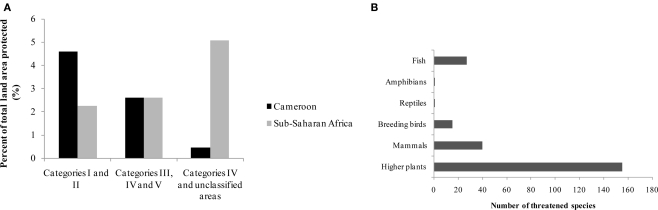

The biodiversity of Cameroon in term of protected land area, number of plant and some animals groups with threatened species are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Table 1.

Biodiversity and protected area in Cameroon, Sub-Saharan Africa, and the World (Source: EarthTrends, 2003).

| Cameroon | Sub-Saharan Africa | World | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total land areas | 47,544 | 2,429,241 | 13,328,979 |

| PROTECTED AREA (000 HA) | |||

| Extent of protected areas by IUCN Category (000 ha), 2003 | |||

| Total protected area (Categories I–V) | 3,741 | 264,390 | 1,457,674 |

| Marine and Littoral protected areasa | 389 | − | 417,970 |

| Protected areas as a percent of total land area | 8.0% | 10.9% | 10.8% |

| Biosphere reserves in 2002 | |||

| Number of sites | 3 | 46 | 408 |

| Total area (000 ha) | 876 | − | 439,000 |

| NUMBER AND STATUS OF SPECIES | |||

| Higher plants | |||

| Total known species (number) | 8,260 | – | – |

| Number of threatened species | 155 | – | 5,714 |

| Mammals | |||

| Total known species (number) | 409 | − | – |

| Number of threatened species | 40 | − | 1,137 |

| Breeding birds | |||

| Total known species (number) | 165 | − | – |

| Number of threatened specie | 15 | − | 1,192 |

| Reptiles | |||

| Number of total known species | 210 | − | – |

| Number of threatened species | 1 | − | 293 |

| Amphibians | |||

| Number of total known species | 171 | − | – |

| Number of threatened species | 1 | − | 157 |

| Fish | |||

| Number of total known species | 138 | − | – |

| Number of threatened species | 27 | − | 742 |

IUCN, International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources; Categories I, Nature Reserves, Wilderness, Areas; Categories II, National Parks; Category III, Natural monument; Category IV, Habitat/species management area; Category V, Protected landscape/seascape.

aMarine and littoral protected areas are not included in the “Total area protected” above; bIncludes IUCN categories I–V, marine and littoral protected areas are excluded from these totals.

(–): data not available.

Figure 1.

Portion of land area protected (A) by IUCN Category (2003) and threatened species (B) (2002–2003) in Cameroon (Source: EarthTrends, 2003). IUCN, International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources; Categories I, nature reserves, wilderness, areas; Categories II, national parks; Category III, natural monument; Category IV, habitat/species management area; Category V, protected landscape/seascape.

Cameroon has a rich biodiversity, with about 8,620 plants species and several animal groups (EarthTrends, 2003), encountered in both protected (about 8 %), and unprotected areas. About 155 plant species are classified by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) as threatened species. Threatened species used as medicinal plants include Thecacoris annobonae Pax & K. Hoffm (Euphorbiaceae) (Cheek, 2004), Pausinystalia johimbe (K. Schum) (Rubiaceae) (Ngo Mpeck et al., 2004), Prunus africana (Hook. f.) Kalkm (Rosaceae) (Focho et al., 2009). Ancistrocladus korupensis D. W. Thomas & Gereau (Ancistrocladaceae), Carpolobia lutea G.Don (Polygalaceae), Dacryodes edulis (G. Don) H. J. Lam. (Burseraceae), Enantia chlorantha Oliv (Annonaceae), Garcinia mannii Oliv. (Clusiaceae), Garcinia cola Heckel (Clusiaceae), Gnetum africanum Welw. (Gnetaceae), Invingia gabonensis Baill. (Irvingiaceae), Massularia acuminata (G. Don) Bullock (Rubiaceae), Pentaclethra macrophylla Benth. (Leguminosae), Baillonella toxisperma Pierre var. obovata Aubrév. & Pellegr. (Sapotaceae), Calamus deeratus Mann & Wendl. (Palmae), Cola acuminata (P.Beauv.) Schoot et Endl. (Sterculiaceae), Eremospatha macrocarpa (Mann & Wendl.) Wendl. (Palmae), Raphia regalis Becc. (Palmae), Raphia vinifera P.Beauv. (Palmae) and Ricinodendron heudelotti (Baill.) Pierre (Euphorbiaceae) (Koné, 1997). Protected zones include both land (3,741 ha) and marine areas (389 ha) (EarthTrends, 2003).

Ethnobotanical Uses of Medicinal Plants in Cameroon

Traditional healing plays an integral role in black African culture as it provides primary health care needs for a large majority (about 80%) of the population (WHO, 2002). In Cameroon, there is a rich tradition in the use of herbal medicine for the treatment of several ailments. Unfortunately, the integration of traditional medicine in the health system is not yet effective, due to its disorganization (Nkongmeneck et al., 2007). However, the government strategies of health envisage the organization of traditional medicine in order to provide the main trends for the development and its integration (Anonymous, 2006). Adjanohoun et al. (1996) provided a useful review of the traditional use of medicinal plants in Cameroon, although much work remains to be done regarding the documentation of existing ethnobotanical knowledge. Jiofack et al. (2010) also documented the traditional use of 289 plants species belonging to 89 families against 220 pathologies. Sixty eight percent of the documented plants are used to treat more than twenty important diseases. They are used as decoction, infusion, maceration, powder, powder mixtures, plaster, calcinations, and squeeze in water, boiling, cooking with young cock or sheep meat or groundnut paste, direct eating, juice, fumigation, and sitz bath (Jiofack et al., 2010). The most recurrent diseases or disorders treated are typhoid, male sexual disorders, malaria, gonorrhea, gastritis, rheumatism, fever, dysentery, diarrhea, dermatitis, boils, cough, wounds, syphilis, sterility, sexually transmitted diseases, ovarian cysts, and amoebiasis, with more than two hundred plants being used to cure these diseases or disorders (Jiofack et al., 2010).

Investigation of the Pharmacological Potential of Medicinal Plants of Cameroon

Antimicrobial activity

Plants are widely used traditionally for the treatment of microbial infections. A review of the antimicrobial potential of Cameroon medicinal plants (Kuete, 2010a) reported more than 58 species in vitro active extracts or isolated compounds. Cut-off points for activity in term of IC50-values were set to 100 μg/ml for extract and 25 μM for compounds (Cos et al., 2006). However, in the case of antimicrobial evaluation of extracts and compounds, determination of IC50 is not the optimal parameter for significance, most of the reported data being given as MIC values. Kuete (2010a) also set the bar as follows for extract: significant (MIC < 100 μg/ml), moderate (100 < CMI ≤ 625 μg/ml) or weak (CMI > 625 μg/ml). For compounds, this stringent endpoints criteria were: significant (MIC < 10 μg/ml), moderate (10 < MIC ≤ 100 μg/ml), and low or negligible (MIC > 100 μg/ml) (Kuete, 2010a). More than 50 microorganisms were found to be sensitive to such extracts and significant activity with minimally inhibiting concentrations (MIC) of less than 100 μg/ml (Kuete, 2010a). Some of the extracts including those from Bersama engleriana, Dorstenia angusticornis, Dorstenia barteri, Diospyros canaliculata, Diospyros crassiflora, Newbouldia laevis, and Ficus cordata exhibited a wide range of activity on both bacteria and fungi (Kuete, 2010a).

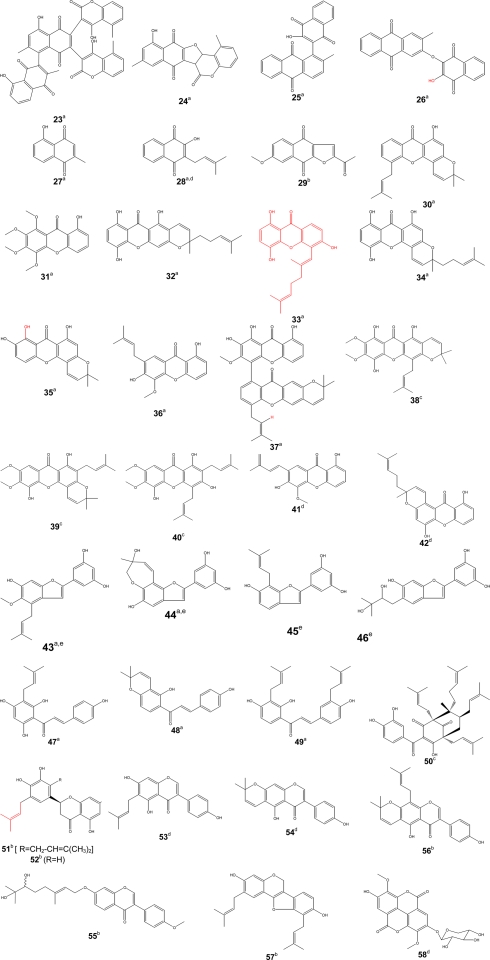

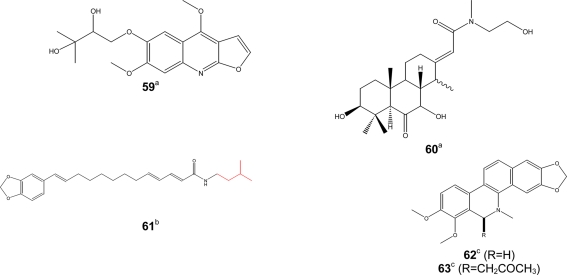

Some of the bioactive compounds such as diospyrone (23), crassiflorone (24), newbouldiaquinone (25), newbouldiaquinone A (26), laurentixanthone A (30), laurentixanthone B (31), smeathxanthone B (32), cheffouxanthone (33), bangangxanthone A (34), globulixanthone C (35), D (36) and E (37), moracin T (43), and U (44), nkolbisine (59), norerythrosuaveolide (60), were isolated and characterized for the first time from Cameroonian medicinal plants (Kuete, 2010a). Other compounds such as plumbagin (27), lapachol (28) (found to be inactive in vivo in some cases), isobavachalcone (47), 4-hydroxylonchocarpin (48), kanzonol C (49) exhibited interesting activities and were suggested as potential candidates for new antimicrobial drug (Kuete, 2010a). Though compound 28 is known to possess good antimicrobial activity in vitro, it will be necessary to assess its in vivo efficacy. However this compounds was active in vitro against intracellular amastigotes of Leishmania braziliensis and inactive in vivo using hamster infected model (Lima et al., 2004). Thecacoris cf. annobonae Pax & K. Hoffm (Euphorbiaceae) exhibited significant antimicrobial (MIC < 10 μg/ml) activities against Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv, Bacillus cereus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Kuete et al., 2010b). The extract from T. annobonae was reported to induce E. coli death through the inhibition of H+-ATPase-mediated proton pumping (Kuete et al., 2010b). Investigations the mode of resistance of the microorganisms to bioactive compounds isolated from Cameroonian medicinal plants have shown that efflux by AcrAB-TolC pumps was one of the likely mechanisms of defense of Gram-negative bacteria to compounds 23 and 47 (Kuete et al., 2010c).

Antimalarial activity

In Cameroon, several plant species are used to treat malaria. A review on traditionally used plants reported up to 217 species (Titanji et al., 2008). Some of these plants were screened in vitro for their activity against P. falciparum and more than 100 bioactive compounds were isolated (Titanji et al., 2008), most of which, however, showed only low or modest antimalarial activities. In the present review, we focus only on plant extract and compounds that exhibited considerably high activities. The proposed cut-off points for in vitro activity of antimalarial extracts based on their IC50 values can be categorized as follows: IC50 < 0.1 μg/ml (very good); 0.1–1 μg/ml (good); 1.1–10 μg/ml (good to moderate); 11–25 μg/ml (weak), 26–50 (very weak), >100 μg/ml (inactive) (Willcox et al., 2004a). The following inhibition percentages were proposed for in vivo activity of antimalarial extracts at a fixed dose of 250 mg/kg/day: 100–90% (very good activity); 90–50% (good to moderate); 50–10% (moderate to weak); 0% (inactive) (Willcox et al., 2004a). Several plant extracts from Cameroonian medicinal plants were reported for their antimalarial activities (Table 2), the most active (IC50 < 1 μg/ml) being that from Enantia chlorantha (Boyom et al., 2009).

Table 2.

Plants used in Cameroon to treat malaria, with evidence of their activities.

| Family | Speciesa | Traditional treatment | Plant part used | Bioactive (or potentially active) compoundsb | Screened activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthaceae | Thomandersia hensii De Wild and Th. Dur (LB Th 0301) | Malaria, diarrhea, colitis, furuncles, abscesses, syphilis, ulcers, urogenital disorders, intestinal parasites, debility, tiredness, edema, rheumatism, eye inflammations (Letouzey, 1985; Ngadjui et al., 1994). | Bark, leaves, pulp, sap, roots | Not identified | IC50 < 30 μg/ml reported for hexane extract from the stem bark on P. falciparum W2 (Indochina I/CDC) chloroquine-resistant strain (Bickii et al., 2007b) |

| Annonaceae | Uvariopsis congolana (De Wild) Fries (37016/HNC) | Malaria (Boyom et al., 2009) | Bark, leaves | Not identified, but plants of this family were reported to contain acetogeninsc | IC50 < 5 μg/ml reported for the crude extract from the leaves and bark on P. falciparum strain W2 (Boyom et al., 2009) |

| Polyalthia oliveri Engl. (19416 SRF/Cam) | Malaria (Boyom et al., 2009) | Bark | IC50 < 5 μg/ml reported for the crude extract from the bark on P. falciparum strain W2 (Boyom et al., 2009) | ||

| Enantia chlorantha Oliv. (32065/SRF/Cam) | Malaria (Boyom et al., 2009) | Bark, leaves | Not identified | IC50 < 1 μg/ml reported with the crude extract from the leaves and bark on P. falciparum strain W2 (Boyom et al., 2009) | |

| Apocynaceae | Picralima nitida Stapf (LB Pn 0301) | Malaria, diarrhoea, intestinal worms, gonorrhoea, inflammation (Letouzey, 1985; Ezeamuzie et al., 1994; Fakeye et al., 2000) | Bark, roots, seeds; fruits | Not identified | IC50 < 30 μg/ml reported for the methanol and dichloromethane–methanol 1:1 extracts from the seeds and bark on P. falciparum W2 (Indochina I/CDC) chloroquine-resistant strain (Bickii et al., 2007b) |

| Euphorbiaceae | Croton zambesicus Muell. Arg. (8204/SRFCam) | Malaria (Boyom et al., 2009) | Bark | Not identified | IC50 < 10 μg/ml reported for the crude extract from the bark on P. falciparum strain W2 (Boyom et al., 2009) |

| Neoboutonia glabrescens Müll. Arg. Prain (7433/SRFCam) | Malaria (Boyom et al., 2009) | Bark, leaves | Not identified | IC50 < 10 μg/ml reported for the crude extract from the leaves and bark on P. falciparum strain W2 (Boyom et al., 2009) | |

| Guttiferae | Symphonia globulifera Linn f. (50788/HNC) | Stomach and skin aches, laxative for pregnant women, general tonic, Malaria (Aubreville, 1950; Irvine, 1961; Ngouela et al., 2006). | Bark | Gaboxanthone (38); symphonin (39); globuliferin (40); guttiferone A (50) (Ngouela et al., 2006). | IC50 <20 μM on P. falciparum reported for compounds 38–40 and 50 (Ngouela et al., 2006). |

| Lauraceae | Beilschmiedia zenkeri Engl. | Not reported | Bark | 5-Hydroxy-7,8-dimethoxyflavone; pipyahyine; betulinic acid (Lenta et al., 2009) | IC50 <5 μM on chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum reported for pipyahyine (Lenta et al., 2009) |

| Meliaceae | Entandrophragma angolense Welwitsch C.D.C. (29933/HNC) | Malaria (Bickii et al., 2007a) | Bbark | 22-Hydroxyhopan-3-one; 24-methylenecycloartenol (8); tricosanoic acid; methylangolensate; 7α-acetoxydihydronomilin (9); 7α-obacunylacetate (10) (Bickii et al., 2007a) | IC50 < 20 μg/ml on P. falciparum W2 strain reported for compounds 8–10. The dichloromethane – methanol (1:1) extract of the stem bark of that plant exhibited IC50 of 18.8 μg/ml (Bickii et al., 2007a) |

| Khaya grandifoliola C.D.C. (PM 098/95/HNC) | Malaria (Obih et al., 1985; Bray et al., 1990; Weenen et al., 1990). | Bark and seeds | Methylangolensate (1); 6-methylhydroxyangolensate (2); gedunin (3); catechin; 7-deacetylkhivorin (4); 1-deacetylkhivorin (5); swietenolide (6); 6-acetylswietenolide (7) (Bickii et al., 2000) | IC50 < 20 μg/ml on P. falciparum W2 strain reported for bark and seeds extracts; compounds 1–7. Compound 3 exhibited an additive effect when combined with chloroquine (Bickii et al., 2000) | |

| Turreanthus africanus | Malaria and other fevers (Zhou et al., 1997) | Bark, seeds, leaves | 16-oxolabda-8 (17), 12(E)-dien-15-oic acid; methyl-14, 15-epoxylabda-8 (17), 12(E)-diene-16-oate; turreanin A (Ngemenya et al., 2006) | None of the active compounds exhibited IC50 < 20 μg/ml on P. falciparum F 32, chloroquine sensitive strain (Ngemenya et al., 2006) | |

| Moraceae | Artocarpus communis J.R. & G. Forst (43982 HNC) | Malaria (Boyom et al., 2009) | Bark, leaves | Not identified | IC50 < 10 μg/ml reported for the crude extract from the leaves and bark on P. falciparum strain W2 (Boyom et al., 2009) |

| Dorstenia convexa De Wild (53450 HNC) | Malaria (Boyom et al., 2009) | Twigs | Not identified | IC50 < 10 μg/ml reported with the crude extract from the twigs on P. falciparum strain W2 (Boyom et al., 2009) | |

| Zingiberaceae | Aframomum zambesiacum (Baker) K. Schum (37737HNY) | Malaria (Kenmogne et al., 2006) | Seeds | Aulacocarpin A (11); aulacocarpin B; 3-deoxyaulacocarpin A (12); methyl-14n,15-epoxy-3b-hydroxy-8(17),12-elabdadien-16-oate; galanolactone; zambesiacolactone A (13); zambesiacolactone B (14); aframodial (Kenmogne et al., 2006) | IC50 < 20 μM on P. falciparum reported for compounds 11–14 (Kenmogne et al., 2006) |

| Reneilmia cincinnata (K. Schum.) Bak. | Malaria (Tchuendem et al., 1999) | Fruits | Oplodiol (17); 5E,10(14)-Germacradien-1β,4β-diol (16); 1(10)E,5E-germacradien-4β-ol (15) (Tchuendem et al., 1999) | IC50 < 5 μM reported on P. falciparum D6 and W2 strains for compounds 15–17 on P. falciparum D6 strain (Tchuendem et al., 1999 |

aHNC or SRFK: Cameroon National herbarium code; LB, Laboratory of Botany, Yaoundé.

bCompounds characterized for the first time in Cameroonian medicinal plant are underlined.

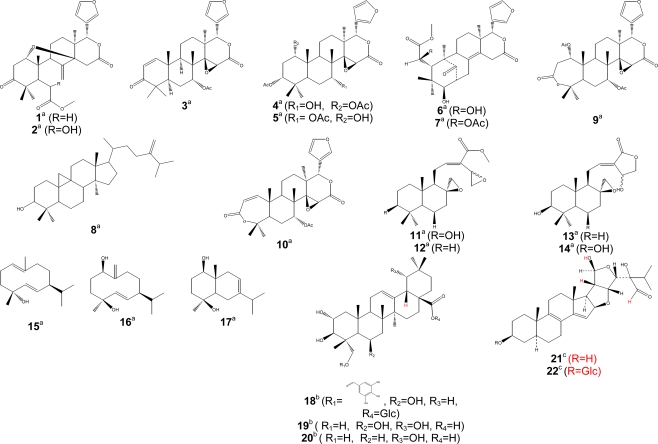

Some isolated compounds were also reported for their antimalarial activities (Table 2). An IC50 of 1.5 μM was chosen as cut-off point for several compounds (Calas et al., 1997). The threshold for in vitro chloroquine resistance has been defined as IC50 > 100 nM (Ringwald et al., 1996). According to Mahmoudi et al. (2006), compounds with IC50 > 5 μM were considered as inactive against parasite development, compounds with IC50 between 0.06 and 5 μM being active, and values of IC50 < 0.06 μM implying the drugs to be very toward P. falciparum. We will take into consideration up to IC50 < 20 μg/ml to report on the activity of antimalarial compounds isolated from Cameroonian medicinal plants. So far, active compounds isolated belong to three main groups of secondary metabolites, terpenoids (Figure 2), phenolics (Figure 3), and alkaloids (Figure 4). Antimalarial terpenoids including sesqui-, di-, and triterpenoids are the most frequently isolated compounds from Cameroonian plants. Several natural products were reported as being active against Plasmodium falciparum, with IC50 values below 20 μg/ml, including methylangolensate (1); 6-methylhydroxyangolensate (2); gedunin (3); 7-deacetylkhivorin (4); 1-deacetylkhivorin (5); swietenolide (6); 6-acetylswietenolide (7) (Bickii et al., 2000); 24-methylenecycloartenol (8); 7α-acetoxydihydronomilin (9); 7α-obacunylacetate (10) (Bickii et al., 2007a); aulacocarpin A (11); 3-deoxyaulacocarpin A (12); zambesiacolactone A (13), and B (14) (Kenmogne et al., 2006); 1(10)E,5E-germacradien-4β-ol (15); 5E,10(14)-germacradien-1β,4β-diol (16); oplodiol (17) (Tchuendem et al., 1999); IC50 < 5 μg/ml were obtained for compounds 3 (1.25 μg/ml), and 10 (2 μg/ml) (Bickii et al., 2000, 2007a), while values below 5 μM were recorded for compounds 12 (4.97 μM) (Kenmogne et al., 2006), 15 (1.54 μM); 16 (1.63 μM) and 17 (4.17 μM) (Tchuendem et al., 1999).

Figure 2.

Bioactive terpenoids. Activity [(a) antimalarial, (b) anti-inflammatory, (c) antitrypanosomal]; Glc, glucosyl group; Ac, acetyl group.

Figure 3.

Bioactive phenolics [quinones (23–29), xanthones (30–42), arylbenzofurans (43–46)]. Activity [(a) antimicrobial, (b) anti-inflammatory, (c) antimalarial, (d) anti-proliferative, (e) antioxidant]. [Chalcones (47–49), benzophenone (50), flavone (51–52), isoflavones (53–56), pterocarpene (57), ellagic acid derivative (58)]. Activity [(a) antimicrobial, (b) anti-inflammatory, (c) antimalarial, (d) anti-proliferative, (e) antioxidant].

Figure 4.

Bioactive alkaloids. Activity [(a) antimicrobial, (b) antimalarial, (c) antileishmanial].

Phenolic compounds (Figure 3) such as gaboxanthone (38); symphonin (39); globuliferin (40); guttiferone A (50) (Ngouela et al., 2006) also exhibited antimalarial activities when tested on P. falciparum. IC50 values below 5 μg/ml were reported with compounds 38 (3.53 μM); 39 (1.29 μM); 40 (3.86 μM) and 50 (3.17 μM) (Ngouela et al., 2006). Few alkaloids from Cameroonian medicinal plants (Figure 4) were characterized. For example, pipyahyine (61) exhibited good activity (IC50 < 5 μM) toward chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum (Lenta et al., 2009).

Studies dealing with the mechanisms of action of antimalarial compounds are still limited. However, some of the extracts from Cameroonian medicinal plants such as those from Annonaceae species were suggested to exert their antiplasmodial activity by the inhibition of vital parasitic enzymes such as cysteine proteases (Boyom et al., 2009).

Other anti-parasitic activities

Parasitic trypanosomatids cause a number of important diseases, including human African trypanosomiasis, Chagas disease, and leishmaniasis. More than 60 million people living in 36 sub-Saharan Africa countries are at risk of contracting sleeping sickness, caused by Trypanosoma brucei gambiense and T. b. rhodesience (WHO, 2007). It is estimated that currently 300,000–500,000 people were infected in 2001, with 50,000 deaths annually (Fairlamb, 2003; WHO, 2007). Leishmania species cause a spectrum of disease ranging from self-healing cutaneous lesions to life-threatening visceral infections, with 2 million new cases occurring annually (WHO, 2005). It is estimated that about 200 million people worldwide are currently affected by schistosomiasis, a disease caused by flatworms belonging to the genus Schistosoma. The disease is usually chronic and debilitating, with severe consequences on the urinary tract where S. haematobium is the organism involved and major damage to the intestinal tract where S. mansoni, S. intercalatum or S. japonicum are involved (Jatsa et al., 2009). In humans, Toxoplasma infections are widespread and lead to severe diseases in individuals with immature or suppressed immune system. Consequently, toxoplasmosis became one of the major opportunistic infections of the AIDS epidemic (Luft and Remington, 1992). Toxoplasmosis also affects T. gondii-negative women during pregnancy and is a serious threat for embryos. Despite the huge impact of these parasitic diseases, the drugs used for their treatment are often toxic, marginally effective, administered by injection only, expensive, and/or compromised by the development of resistance (Ouellette et al., 2004; Croft et al., 2005). Only few researchers in Cameroon focused on antitrypanosomal and antileishmanial compounds from medicinal plants. Available published data on traditionally used medicinal plants are compiled in Table 3. Herein, similar cut-off points as indicated above for antimalarials have been considered for activities against trypanosomal, leishmanial and schistosomal pathogens. Compounds with good antileishmanial activities were isolated from Garcinia lucida (Clusiaceae), with IC50 values of 2.0 and 6.6 μg/ml, respectively, for dihydrochelerythrine (62) and 6-acetonyldihydrochelerythrine (63) against L. donovani (Fotie et al., 2007). Significant antitrypanosomal activities were also reported for stigmastane derivatives, vernoguinosterol (21) and vernoguinoside (22) (Figure 2) isolated from Vernonia guineensis (Asteraceae), against bloodstream trypomastigotes of Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense with IC50 values ranging from 3 to 5 μg/ml (Tchinda et al., 2002).

Table 3.

Plants used in Cameroon to treat some parasitic infections with evidence of their activities.

| Family | Speciesa | Traditional treatment | Plant part used | Bioactive (or potentially active) compoundsb | Screened activityc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annonaceae | Polyalthia suaveolens Engl. & Diels (1227/SRFK) | Rheumatic pains (Surville, 1955) | Not specified | Polyveoline; 3-O-acetyl greenwayodendrin; polysin; greenwayodendrin-3-one (Ngantchou et al., 2010) | Antitrypanosomal activity: weak activity for polyveoline (IC50: 32 μM); 3-O-acetyl greenwayodendrin (IC50: 54 μM); mixture of polysin and greenwayodendrin-3-one (IC50: 18 μM) against T. brucei (Ngantchou et al., 2010) |

| Asteraceae | Vernonia guineensis Benth. (BUD 301) | Anthelmintic, anti-poison, malaria, jaundice (Iwu, 1993) | Leaves | Vernoguinosterol (21); vernoguinoside (22) (Tchinda et al., 2002) | Antitrypanosomal activity: significant for compounds 22 and 23 against four strains of bloodstream trypomastigotes T. b. rhodesiense with IC50 values in the range 3–5 mg/ml (Tchinda et al., 2002) |

| Guttiferae | Garcinia lucida Vesque (5768/HNC) | Gastric infections, anti-poison (Nyemba et al., 1990) | Bark | Dihydrochelerythrine (62); 6-acetonyldihydrochelerythrine (63); lucidamine A (Fotie et al., 2007) | Antileishmanial activity: Significant activity for compounds 62 and 63 and moderate for lucidamine A against L. donovani. Also, 100% Inhibition of promastigote at 100 μg/ml were reported for all the above compounds (Fotie et al., 2007) |

| Meliaceae | Turraeanthus africanus (Welw. ex C.D.C.) Pellegr (8233/HNC) | Asthma, stomachache, intestinal worms, and inflammatory diseases (Ekwalla and Tongo, 2003) | Aerial parts, roots | Turraeanthin C; sesamin (Vardamides et al., 2008) | Antitoxoplamal activity: Moderate activity for turraeanthin C and low activity for crude bark extract and sasamin. Inhibition of parasite growth at 10 μg/ml was found to be 55% for turraeanthin C, 20% for sesamin and 40% for crude extract (Vardamides et al., 2008) |

| Verbenaceae | Clerodendrum umbellatum Poir (7405/HNC) | Epilepsy, headache, intestinal helminthiasis, irregular menstruation, infective dermatitis, asthma, metaphysical powers, whitlow, vulvovaginitis (Adjanohoun et al., 1996; Jatsa et al., 2009) | Not specified | Not identified but, flavonoids, saponins, saponosides, tannins, and triterpenes were detected in the leaves aqueous extract (Jatsa et al., 2009) | Antischistosomal activity: 100 % reduction rate reported for mice infected with S. mansoni when treated with 160 mg/kg body weight of aqueous leaves extract (Jatsa et al., 2009) |

aHNC or SRFK: Cameroon National herbarium code; BUD, Herbarium of the Botany Department of the University of Dschang, Cameroon).

bCompounds characterized for the first time in Cameroonian medicinal plant are underlined.

cScreened activity: Leishmania donovani (L. donovani); Schistosoma mansoni (S. mansoni); Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii); Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense (T. b. rhodesiense); Trypanosoma brucei (T. brucei).

Anti-proliferative activity

Screenings of medicinal plants used as anticancer drugs has provided modern medicine with effective cytotoxic pharmaceuticals. More than 60% of the approved anticancer drugs in United State of America (from 1983 to 1994) were from natural origin (Stévigny et al., 2005; Newman and Cragg, 2007). The diversity of the biosynthetic pathways in plants has provided a variety of lead structures that have been used in drug development. In this last decade, investigations on natural compounds have been particularly successful in the field of anticancer drug research. Early examples of anticancer agents developed from higher plants are the antileukemic alkaloids (vinblastine and vincristine), which were both obtained from the Madagascar periwinkle (Catharanthus roseus) (Voss et al., 2005). The development of the highly automated bioassay screening based on colorimetric methods that quantified the proliferation of cell culture (Mosmann, 1983) of a huge number of plants extracts have permitted to find that many plant families (Guittiferae, Rubiaceae, Apocynaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Solanaceae, etc.) exhibited a great potential of anti-proliferative activity (Hostettmann et al., 2000; Whelan and Ryan, 2003). A large number of plant extracts have shown the in vitro and in vivo antitumor activities (Hostettmann et al., 2000). In the US NCI plant screening program, a crude extract is generally considered to have in vitro cytotoxic activity if the IC50 value following incubation between 48 and 72 h, is less than 20 μg/ml, while it is less than 4 μg/ml for pure compounds (Boik, 2001). This cut-off point for good cytotoxic compound has also been defined as 10 μM (Brahemi et al., 2010). Despite the exceptional biodiversity of Africa, few scientific studies have been carried out in the continent regarding the anti-proliferative properties of medicinal plants. However, some Cameroonian plants and derived natural products were tested for their anti-proliferative effects. Five medicinal plants widely used in cancer treatment, Sida acuta, Sida cordifolia, Sida rhombilifolia, Urena lobata, Viscum album, were recently screened for their cytoxicity against Hep G2 hepatocarcinoma cells rather showed moderate anti-proliferative effects (Pieme et al., 2010). However, studies based on the inhibition of Crown Gall tumors revealed pronounced tumor reducing activity of extracts from the roots and leaves from Bersama engleriana (Kuete et al., 2008). An IC50 of 27.16 μg/ml was reported for Antiaris africana in DU-145 prostate cancer cells, while even better activity (IC50 of 13.84 μg/ml) was recorded in Hep G2 hepatocarcinoma cells (Kuete et al., 2009). One of the most active compounds isolated from A. africana, 3,39-dimethoxy-49-O-β-d-xylopyronosylellagic acid (58) (Figure 3) exhibited considerable anti-proliferative activities toward HepG2 (IC50 of 3.84 μg/ml) and DU-145 (IC50 of 6.24 μg/ml) cells (Kuete et al., 2009). Compound 28, the main constituent of a Cameroonian medicinal plant, Newbouldia leavis (Bignoniaceae) was found to be very active against DU-145 cells with an IC50 of 64.59 nM (Eyong et al., 2008). Wighteone (53) and alpinumisoflavone (54) isolated from Erythrina indica (Leguminosae) were reported to be cytotoxic (effective dose of 0.78 and 4.13 μg/ml, respectively) when tested against KB nasopharyngeal cancer cells (Nkengfack et al., 2001). Globulixanthones A (41) and B (42) isolated for the first time in the Cameroonian medicinal plant, Symphonia globulifera L. f. (Clusiaceae), showed good anti-proliferative activities against human KB cells, with IC50 values of 2.15 and 1.78 μg/ml, respectively (Nkengfack et al., 2002). Compound 47 isolated from Dorstenia barteri (Ngameni et al., 2007) and D. turbinata (Ngameni et al., 2009) was cytotoxic toward a wide spectrum of tumor cell lines, including ovarian carcinoma OVCAR-8 cells, prostate carcinoma PC3 cells, breast carcinoma MCF-7 cells, and lung carcinoma A549 cells (Jing et al., 2010). Compound 47 significantly ablated Akt phosphorylation at Ser-473 and Akt kinase activity in cells, which subsequently led to inhibition of Akt downstream substrates and evoked significant levels the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis (Jing et al., 2010). Nishimura et al. (2007) demonstrated that compound 47 induced apoptotic cell death with caspase-3 and -9 activation and Bax upregulation in neuroblastoma cell lines. Compound 47 inhibited MMP-2 secretion from U87 glioblastoma cells (Ngameni et al., 2007). Compounds 48 and 49 also isolated from Dorstenia turbinata (Moraceae), inhibited the matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 secretion from brain tumor-derived glioblastoma cells (Ngameni et al., 2006).

Anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities

Pain is one common health problem with substantial socioeconomic impact because of its high incidence. It is a symptom of many diseases and it is estimated that 80–100% of the population experience back pain at least once in the life time (Jain et al., 2002). The treatment of pain requires analgesics including inflammatory products. Hence, most of the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents also have analgesic activity. The inhibition of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and nitric oxide (NO) production has been proposed as a potential therapy for different inflammatory disorders (Nowakowska, 2007). Although, many analgesics and anti-inflammatory agents are present on the market, modern drug therapy is associated with some adverse effects like gastrointestinal irritation (Jain et al., 2002; Osadebe and Okoye, 2003), fluid retention, bronchospasm, and prolongation of bleeding time. Therefore, it is necessary to search for new drugs with less adverse effects. Medicinal plants have been used for the development of new drugs and continue to play an invaluable role for the progress of drug discovery (Raza et al., 2001). Plant extracts can be an important source of safer drugs for the treatment of pain and inflammation. Several medicinal plants and derived products were screened for their anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties (Table 4). Bark extract as well as terpenoids from Combretum molle (Combretaceae), β-d-glucopyranosyl 2α,3β,6β-trihydroxy-23-galloylolean-12-en-28-oate (18); combregenin (19); arjungenin (20) (Figure 2) showed good activities against carrageenan-induced paw edema in rat (Ponou et al., 2008). A naphthoquinone, 2-acetyl-7-methoxynaphthol[2,3-b]furan-4,9-quinone (29), isolated from the anti-inflammatory crude extract of Millettia versicolor inhibited 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate (TPA)-induced acute ear edema and phospholipase A2 (PLA2) acute mouse paw edema (Fotsing et al., 2003). Isoflavones, griffonianone D (55) (Figure 3) isolated from Millettia griffoniana (Yankep et al., 2003), warangalone (56) isolated from the bark of Erythrina addisoniae (Talla et al., 2003), and erycristagallin (57) isolated from the root of Erythrina mildbraedii (Njamen et al., 2003), showed marked effectiveness as an anti-inflammatory on PLA2-induced paw edema and on TPA-induced ear edema in mice (Njamen et al., 2003; Talla et al., 2003). Flavonoids sigmoidin A (51) and B (52) (Figure 3) isolated from Erithrina sigmoidea, and compound 57 were also effective against TPA-induced ear edema (Njamen et al., 2003, 2004).

Table 4.

Plants used in Cameroon as anti-inflammatory and analgesic agents, with evidence of their activities.

| Family | Speciesa | Traditional treatment | Plant part used | Bioactive (or potentially active) compoundsb | Screened activityc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthaceae | Acanthus montanus (Nees) T. Anderson (1652/SRF61CAM) | Cough, hypertension, skin infection, boil, witches, dysmenorrhoea, pain, epilepsy, miscarriages, heart troubles, rheumatic pain, syphilis (Burkill, 1985; Adjanohoun et al., 1996; Babu et al., 2001; Noumi and Fozi, 2003; Igoli et al., 2005; Nana et al., 2008) | Leaves | Not identified | Leave extract showed analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties and the proposed mechanism was the inhibition of the prostaglandins pathway at 200 mg/kg in rats. Also, this extract at 200 mg/kg body weight in rats reduced carrageenan-induced edema, and formalin-induced pain (Asongalem et al., 2004). |

| Anacardiaceae | Sclerocarya birrea (A. Rich.) Hochst (7770/HNC) | Boils and blood circulation problems, rheumatism, infectious diseases, inflammation (Mojeremane and Tshwenyane, 2004; Fotio et al., 2009) | Bark | Not identified | Bark extract inhibited albumin-induced paw edema (Ojewole, 2004), Formalin- or Freund's adjuvant (CFA)-carrageenan-, histamine, or serotonin-induced paw edema (Fotio et al., 2009) in rats |

| Caesalpiniaceae | Erythrophleum suaveolens, Guillemin & Perrottet (HN001AD) | Anti-poison, dermatitis, infectious disease, convulsion, inflammation due to snake bite, cardiac problems, headaches, migraines edema, rheumatism, asthma (Dalziel, 1937; Bouquet, 1969; Leiderer, 1982; Neuwinger, 1998) | Bark | Not identified | Extract from the bark and fractions at 19.2 μg/ml showed inhibition of carrageenin-induced paw edema in rats; Hexane fraction inhibited the 5-lipoxygenase activity (Dongmo et al., 2001) |

| Combretaceae | Combretum molle R.Br. ex G.Don (6518/SRF/CAM) | Fever, abdominal pains, convulsion, worm infections, AIDS (Bessong et al., 2004) | Bark | β-d-glucopyranosyl 2α,3 β,6β-trihydroxy-23-galloylolean-12-en-28-oate (18); combregenin (19); arjungenin (20), arjunglucoside I, combreglucoside (Ponou et al., 2008) | Bark extract, compounds 18–20 showed good activity against carrageenan-induced paw edema in rat (Ponou et al., 2008) |

| Crassulaceae | Kalanchoe crenata Andr. (50103/YA/HNC) | Earache, smallpox, headache, inflammation, pain, asthma, palpitation, convulsion, general debility (Dimo et al., 2006) | Not specified | Not identified | n-Butanol fraction inhibited carrageenani-, histamine-, serotonin-, and formalin-induced paw edema in rats (Dimo et al., 2006) |

| Euphorbiaceae | Bridelia scleroneura (42088/HNC) | Abdominal pain, contortion, arthritis, inflammation (Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962; Théophile et al., 2006) | Bark, roots | Not identified | Crude bark extract showed peripheral and central analgesic and anti-inflammatory activity against acute inflammation processes in rats (Théophile et al., 2006) |

| Euphorbiaceae | Uapaca guineensis (41501/HNC) | Fever, inflammation, pain, skin diseases, and sexual dysfunction (Vivien and Faure, 1996) | Not specified | Not identified | Bark crude extract showed analgesic activity, and inhibited carrageenan-induced inflammation in rats (Nkeh-Chungag et al., 2009) |

| Guttiferae | Allanblackia monticola Staner L.C. (61168/HNC) | Amoebic dysentery, diarrhea, indigestion, pulmonary infections, skin diseases, headache, inflammation, and generalized pain (Raponda-Waker and Sillans, 1961) | Bark | Betulinic acid, lupeol, and amangostin (Nguemfo et al., 2009) | Crude extract from the bark, lupeol, betulinic acid, and a-mangostin inhibited paw carrageenan-induced edema rat (Nguemfo et al., 2007, 2009) |

| Leguminosae | Erythrina addisoniae Hutchinson & Dalziel (41617/HNC) | Dysentery, asthma, venereal diseases, boils, and leprosy (Talla et al., 2003) | Bark | Warangalone (56) (Talla et al., 2003) | Bark extract and compound 56 showed an anti-inflammatory on the PLA2-induced paw edema and 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate-induced ear edema in mice (Talla et al., 2003) |

| Erythrina mildbraedii Harms (50452/HNC) | Dysentery, stomach pains, venereal diseases, asthma, female sterility, ulcers, boils and various types of inflammations (Oliver-Bever, 1986) | Bark, roots | Erycristagallin (57) (Njamen et al., 2003) | Root bark extract inhibited the carrageenan-induced mouse paw whilst compound 57 inhibited the PLA2-induced mouse paw edema and mouse ear edema induced by 2-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate (Njamen et al., 2003) | |

| Erythrina sigmoidea Hua | Female infertility, stomach pain, and gonorrhea (Giner-Larza et al., 2001) | Bark | Sigmoidin A (51) and B (52) (Njamen et al., 2004) | Compound 51 inhibited PLA2-induced paw edema in mice, while both compounds 51 and 52 were found to be effective 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate-induced ear edema (Njamen et al., 2004) | |

| Millettia versicolor Welw. (32315/HNC) | Intestine parasitosis, rheumatism, pain, infertility (Adjanohoun et al., 1988; Bouquet, 1969) | Not specified | 2-acetyl-7-methoxynaphthol2,3-bfuran-4,9-quinone (29) (Fotsing et al., 2003) | CH2Cl2 fraction from methanol crude bark extract inhibited carrageenan-induced paw edema and TPA-induced acute ear edema in mouse as well as compound 29 (Fotsing et al., 2003) | |

| Millettia griffoniana Baill. (32315/SRF/HNC) | Boils, insects bits, inflammatory affections like pneumonia, and asthma, infertility, amenorrhea, menopausal disorders (Sandberg and Cronlund, 1977) | Bark, roots | griffonianone D (55) (Yankep et al., 2003) | Extract of the root bark and compound 55 showed anti-inflammatory effects via inhibition of PLA2-induced mouse paw edema and TPA-induced acute mouse ear edema (Yankep et al., 2003) | |

| Solanaceae | Solanum torvum Swartz. (21103/HNC) | Fever, wounds, tooth decay, haemostatic properties, pain, anti-inflammation (Henty, 1973; Ndebia et al., 2007) | Leaves | Not identified | Crude extract from the leaves inhibits both acetic acid- and pressure-induced pain at 300 mg/kg body weight of rats, and also anti-inflammatory activity on carrageenan-induced paw edema (Ndebia et al., 2007 |

aHNC or SRFK: Cameroon National herbarium code.

bCompounds characterized for the first time in Cameroonian medicinal plant are underlined.

cScreened activity: TPA (2-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate); PLA2 (phospholipase A2).

Anti-diabetic activity

Diabetes mellitus is a group of metabolic disorders with one common manifestation, hyperglycemia (WHO, 1980, 1985). Chronic hyperglycemia causes damage to eyes, kidneys, nerves, heart, and blood vessels (Mayfield, 1998). It is caused by inherited and/or acquired deficiency in insulin production of the pancreas, or by unresponsiveness toward insulin. It results either from inadequate secretion of hormone insulin, an inadequate response of target cells to insulin, or a combination of these factors (Malviya et al., 2010). Diabetes is projected to become one of the world's main disablers and killers within the next 25 years (Malviya et al., 2010). The management of diabetes is a global problem and a successful treatment has not yet been discovered. The total number of persons affected globally is projected to rise from 246 million in 2007 to 380 million in 2025, if prevention measures will not be scaled up (Bennett, 2007). In Africa, the number of diabetic patients in 2006 was 10.4 million, and it is expected to increase to 18.7 million in 2025. The annual mortality linked to diabetes worldwide is estimated to be above one million. In Cameroon, the prevalence of diabetes increased from 2% in 1998 (in a study supported by the World Diabetes Foundation, WDF) to 5% in 2003 and 6.5% in 2007 (in another WDF study, Walgate, 2008). Medicinal plants have been reported to be useful in diabetes worldwide and have empirically been used as anti-diabetic and anti-hyperlipidemic remedies. Anti-hyperglycemic effects of these plants were attributed to their ability to restore the function of pancreatic tissues by increasing insulin output, inhibiting the intestinal absorption of glucose, or enhancing metabolism of insulin-dependent processes. Several plant preparations were traditionally used in Cameroon to treat diabetes. Some of them were screened for their bioactivity, but most of the studies were not pursued until the isolation of active principles. Plants with hypoglycaemic activities include Anacardium occidentale, Sclerocarya birrea, Ageratum conyzoides, Ceiba pentandra, Kalanchoe crenata, Bridelia ndellensis, Irvingia gabonensis, Bersama engleriana and Morinda lucida (Table 5).

Table 5.

Plants used in Cameroon to treat diabetes, with evidence of their activities.

| Family | Speciesa | Traditional treatment | Plant part used | Bioactive (or potentially active) compounds | Screened activityb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anacardiaceae | Anacardium occidentale L. (41935/HNC) | Diabetes mellitus (Kamtchouing et al., 1998) | Leaves | Not identified | Leaves extract showed anti-diabetes activity through protective role against the diabetogenic action of STZ and hypoglycemic effects in rats (Kamtchouing et al., 1998; Sokeng et al., 2007) |

| Sclerocarya birrea (A. Rich.) Hochst (7770/HNC) | Diabetes, diarrhea, dysentery, gangrenous rectitis, fevers, stomach disorders, ulcers, sore eyes (Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962; Bryant, 1966; Gelfand et al., 1985; Dieye et al., 2008) | Leaves, bark, roots | Not identified | Bark extracts have been reported to exert hypoglycemic in rats following acute and chronic treatments (Ojewole, 2003; Dimo et al., 2007; Gondwe et al., 2008), acting directly on insulin-secreting cells (Ndifossap et al., 2010) | |

| Asteraceae | Ageratum conyzoides L. (19050/SFR/Cam) | Cough, fever, skin disease, diabetes, bleeding due to external wounds, furuncle, eczema, carbuncle, headaches (Lavergne and Véra, 1989; Tsabang et al., 2001) | Whole plant | Not identified | Leaves extract showed hypoglycemic and anti-hyperglycemic activities in STZ-induced diabetic rats (Nyunaï et al., 2009) |

| Bombacaceae | Ceiba pentandra (L) Gaertner (43623/HNC) | Diuretic, diabetes, hypertension, headache, dizziness, constipation, mental trouble, fever, peptic ulcer, rheumatism, leprosy (Noumi et al., 1999; Ngounou et al., 2000; Noumi and Dibakto, 2000; Noumi and Tchakonang, 2001; Ueda et al., 2002) | Bark, leaves, roots | Not identified | Roots extract reduced hyperglycemia in STZ-induced diabetic rats (Dzeufiet et al., 2006) |

| Crassulaceae | Kalanchoe crenata (WEKC) (50103/YA/HNC) | Inflammatory diseases, diabetes (Kamgang et al., 2008) | Whole plant | Not identified but terpenoids, tannins, polysaccharides, saponins, flavonoids and alkaloids were identified from the leaves (Kamgang et al., 2008) | Ethanol extract of the whole plant was found to possess significant hypoglycemic effect in normal rats by lowering blood glucose levels and anti-hyperglycemic effect by lowering and maintaining glycemia at normal levels in diabetic rats (Kamgang et al., 2008) |

| Euphorbiaceae | Bridelia ndellensis Beille (9676/HNC) | fever, rheumatism, diarrhea, and diabetes (Addae-Mensah and Achenbach, 1985; Onunkwo et al., 1996; Sokeng et al., 2005) | Not specified | Not identified | Ethyl acetate and dichloromethane extracts and fractions of the bark significantly lowered blood glucose levels in type 2 diabetic rats (Sokeng et al., 2005) |

| Irvingiaceae | Irvingia gabonensis (Aubry Lecomte ex O'Rorke) Baill. (28054/HNC) | Gonorrhea, gastrointestinal and hepatic disorders, wounds infection, diabetes, analgesis (Ngondi et al., 2005) | Bark, fruits, leaves, roots | Not identified | Seeds extract showed modulatory effect on diabetes induced dyslipidemia (Dzeufiet et al., 2009) in rats |

| Melianthaceae | Bersama engleriana Gurke (24725/HNC) | Cancer, spasms, infectious diseases, male infertility, diabetes (Watcho et al., 2007) | Leaves, Stem bark, roots | Not identified but flavonoids, phenols, triterpenes, saponins, and anthraquinones were detected in all parts of the plan (Kuete et al., 2008) | Leaves extract showed hypoglycemic properties (Njike et al., 2005) |

| Rubiaceae | Morinda lucida Benth | Uncontrolled adult cases of diuresis not necessarily associated with diabetes but linked to general body weakness and rapid loss of weight (Kamanyi et al., 1994) | Not specified | Not identified | Root extract showed potent hypoglycemic effects in both normoglycemic and alloxan-induced diabetic mice (Kamanyi et al., 1994) |

aHNC or SRFK: Cameroon National herbarium code.

bScreened activity: streptozotocin (STZ).

Antioxidant activities

The common link between oxidants and inflammatory reactions, infections, cancer, and other disorders has been well established (Mongelli et al., 1997; Wang et al., 1999). However, this may not really be of therapeutic relevance, but more of a preventive medicine. In chronic infections and inflammation as well as in other disorders, release of leukocytes and other phagocytic cells readily defends the organism from further injury. The cells do this by releasing free oxidant radicals, and these by-products are generally reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as super oxide anion, hydroxyl radical, nitric oxide, and hydrogen peroxide that result from cellular redox processes (Ames et al., 1993; Mongelli et al., 1997). At low or moderate concentrations, ROS exert beneficial effects on cellular responses and immune function. At high levels, however, free radicals and oxidants generate oxidative stress, a deleterious process that can damage cell structures, including lipids, proteins, and DNA (Pham-Huy et al., 2008). Oxidative stress plays a major role in the development of chronic and degenerative ailments such as cancer, autoimmune disorders, rheumatoid arthritis, cataract, aging, cardiovascular, and neurodegenerative diseases (Willcox et al., 2004b; Pham-Huy et al., 2008). Antioxidants act as free radical scavengers by preventing and repairing damages caused by ROS and, therefore, can enhance the immune defense and lower the risk of cancer and degenerative diseases (Ames et al., 1993; Pham-Huy et al., 2008). In recent years, there is an increasing interest in finding antioxidant phytochemicals, because they can inhibit the propagation of free radical reactions, and thereby protect the human body from diseases (Terao and Piskula, 1997). Several medicinal plants of Cameroon were screened for their antioxidant properties and a number of bioactive compounds was isolated (Table 6). Omisore et al. (2005) considered the cut-off point for antioxidant activity as 50 μg/ml. Samples with IC50 > 50 μg/ml were classified as being moderately active, while samples with IC50 < 50 μg/ml were judged as having high antioxidant capacity. In the present paper, samples will be considered to have high or significant antioxidant capacity with IC50 < 50 μg/ml (extract) or IC50 < 10 μg/ml (compounds), moderate antioxidant capacity with 50 < IC50 < 100 μg/ml (extract) or 10 < IC50 < 20 μg/ml (compounds) and low antioxidant capacity with IC50 > 100 μg/ml (extract) or IC50 > 20 μg/ml (compounds). Extracts from 42 medicinal plants of Cameroon used for the treatment of anemia, diabetes, AIDS, malaria, and obesity were recently screened for antioxidant properties, with a considerable number showing good activities (Agbor et al., 2007). Many of them exhibited high inhibition percentages on the basis of Folin, Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP), and DPPH (1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl) assays. Plants with good activities included Alchornea cordifolia (Euphorbiaceae), Dacryodes edulis (Burseraceae), Ocimum basilicum (Lamiaceae), Harungana madagascariensis (Hypericaceae), Cylicodiscus gabunensis (Mimosaceae), Coleus coprosifolius (Lamiaceae) (Agbor et al., 2007). Arylbenzofurans isolated from the bark of Morus mesozygia (Moraceae), moracin T (43), moracin U (44), moracin S (45); moracin R (46) also showed strong DPPH scavenging capability with IC50 values of 4.12, 5.06, 6.08, and 7.17 μg/ml, respectively (Kapche et al., 2009). The activity of the crude extract of this plant was also reported as significant (IC50: 5.92 μg/ml), by means of the DPPH scavenging assay (Kapche et al., 2009).

Table 6.

Plants used in Cameroon with evidence of their as antioxidant activities.

| Family | Speciesa | Traditional treatment | Plant part used | Bioactive (or potentially active) compoundsb | Screened activityc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ebenaceae | Diospyros sanza-minika A. Chevalier (9649/SRFCam) | Epilepsy, paralysis, convulsions, spasm, pains (Burkill, 1985) | Leaves | 11-O-p-hydroxybenzoylnorbergenin; 4-O-(30-methylgalloyl)norbergenin; 4-O-syringoylnorbergenin; norbergenin; 4-O-galloylnorbergenin; quercitol (Tangmouo et al., 2009) | DPPH scavenging activity: significant for 4-O-galloylnorbergenin, moderate for norbergenin, 11-O-p-Hydroxybenzoylnorbergenin, 4-O-(30-Methylgalloyl)norbergenin and 4-O-Syringoylnorbergenin (Tangmouo et al., 2009) |

| Guttiferae | Garcinia polyantha Oliv (1337/SRF/Cam) | Dressing for wounds (Bouquet, 1969) | Sap | Bangangxanthone A; bangangxanthone B; 2-hydroxy-1,7-dimethoxyxanthone; 1,5-dihydroxyxanthone (Lannang et al., 2005) | DPPH scavenging activity: bangangxanthone A isolated from the bark showed the best activity with an IC50 = 87.0 μM while the standard value for BHA was IC50 = 42.0 μM (Lannang et al., 2005) |

| Garcinia afzelii Engl. | Bacterial infections, dental caries (Adu-Tutu et al., 1979; Waffo et al., 2006) | Leaves; flowers | Afzeliixanthones A; afzeliixanthones B (Waffo et al., 2006) | DPPH scavenging activity: Significant for the crude extract and moderate for Afzelii xanthones A and B (Waffo et al., 2006) | |

| Hypericaceae | Harungana madagascariensis Lam. (32358/HNC) | Diarrhea, dysentery, indigestion, poor pancreatic function (Berhaut, 1975; Prajapati et al., 2003) | Not specified | Harunmadagascarins A and Harunmadagascarins B, harunganol B and harungin anthrone (Kouam et al., 2005) | DPPH scavenging activity: IC50 of 60.97; 64.76 were recorded with harunmadagascarin and harunganol B respectively (Kouam et al., 2005) |

| Meliaceae | Carapa grandiflora sprsgue | Arthritis, general fatigue, skin diseases and as febrifuge (Ayafor et al., 1994) | Seeds | Quercitrin (Omisore et al., 2005) | DPPH scavenging activity: low for quercetin (Omisore et al., 2005) |

| Mimosaceae | Entada rheedii Spreng (19966/SRI/CAM) | Jaundice (Nzowa et al., 2010) | Seeds | Rheediinoside A; rheediinoside B (Nzowa et al., 2010) | ABTS·+ scavenging activity: moderate for rheediinoside B; low for rheediinoside A; DPPH scavenging activity: low activity for rheediinoside A and rheediinoside B (Nzowa et al., 2010) |

| Moraceae | Dorstenia convexa De Wild (53450 HNC) | Malaria (Boyom et al., 2009) | Twigs | Bartericins A; stigmasterol; isobavachalcone (Omisore et al., 2005) | DPPH scavenging activity: low bartericin A and isobavachalcone and stigmasterol (Omisore et al., 2005) |

| Dorstenia barteri Bureau (44016/HNC) | Snakebite, rheumatic, infectious diseases, arthritis (Tsopmo et al., 1999) | Whole plant | Bartericins A, and B; stigmasterol; isobavachalcone; 4-hydroxylonchocarpin (Omisore et al., 2005) | DPPH scavenging activity: significant for twigs extract (Omisore et al., 2005) | |

| Dorstenia mannii Hook. f. (2135/HNC) | Rheumatism, stomach disorders (Bouquet, 1969) | Leaves | Dorsmanin F; 6,8-diprenyleridictyol (Omisore et al., 2005) | DPPH scavenging activity: low for 6,8-diprenyleriodictyol, and dosrmanin F (Omisore et al., 2005) | |

| Morus mesozygia Stapf. (4228/SRFK) | Arthritis, rheumatism, malnutrition, debility, pain-killers, stomach disorders, wound infections, gastroenteritis, peptic ulcer, infectious diseases (Burkill, 1985; Noumi and Dibakto, 2002) | Bark | Moracin R (46); moracin S (45); moracin T (43); moracin U (44) (Kapche et al., 2009) | DPPH scavenging activity: significant for bark crude extract, compounds 43–46 (Kapche et al., 2009) | |

| Piperaceae | Piper umbellatum Linn (6516/SRF/CAM) | Poisoning, pitting edema, fetal malpresentation, filariasis, rheumatism, hemorrhoids, dysmenorrheal, general pains (Tabopda et al., 2008) | Whole plant | Piperumbellactams A; piperumbellactams B; piperumbellactams C; N-p-coumaroyl tyramine (Tabopda et al., 2008) | DPPH scavenging activity: Moderate activity reported for piperumbellactams A and low activities for piperumbellactams B; C; N-p-coumaroyl tyramine (Tabopda et al., 2008) |

aHNC or SRFK: Cameroon National herbarium code.

bCompounds characterized for the first time in Cameroonian medicinal plant are underlined.

cScreened activity: DPPH or 1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl hydrazyl radical assay (evaluates the ability of antioxidants to scavenge free radicals; Hydrogen-donating ability is an index of the primary antioxidants; these antioxidants donate hydrogen to free radicals, leading to non-toxic species and therefore to inhibition of the propagation phase of lipid oxidation [Lugasi et al., 1998]); ABTS·+: 2,2-azinobis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium radical cation; BHA: 3-t-butyl-4-hydroxyanisole; Significant activity (IC50 < 50 μg/ml), moderate activity (50 < IC50 < 100 μg/ml), low activity (IC50 > 100 μg/ml).

Other activities

Other studies involving Cameroon medicinal plants include their action on human fertility and enzymatic activities. However, few studies have focused on these activities, explaining the scarcity of published data.

Some plants with positive effects on the reproductive system based on studies using experimental rats have been reported. They include Aloe buettneri (Liliaceae), Justicia insularis and Dicliptera verticillata (Acanthaceae) and Hibiscus macranthus (Malvaceae), locally used to regulate the menstrual cycle and to treat dysmenorrhea or infertility in women (Telefo et al., 1998); Basella alba (Basellaceae) (Moundipa et al., 2005), and Mondia whitei (Periplocaceae) traditionally claimed to increase libido (Watcho et al., 2001).

Some compounds from Cameroonian plants were investigated for the ability to interfere with the activity of some enzymes such as xanthine oxidase, phosphodiesterase I, or prolyl endopeptidase. Xanthine oxidase catalyzes the oxidative hydroxylation of hypoxanthine or xanthine using oxygen as a cofactor, and the resulting end products are superoxide anion (O2·−) and uric acid. The inhibitors of xanthine oxidase enzyme can prevent the generation of excess superoxide anions (Chung et al., 1997). Phosphodiesterase I successively hydrolyzes 5′-mononucleotides from 3′-hydroxyl-terminated ribo- and deoxyribo-oligonucleotides. The enzyme has been widely utilized as a tool for structural and sequential studies of nucleic acids. The 5′-nucleotide phosphodiesterase isozyme-V test is useful in detecting liver metastatis in breast, gastrointestinal, lung, and various other forms of cancers (Lei-Injo et al., 1980). Prolyl endopeptidase catalyzes the hydrolysis of peptide bonds at the l-proline carboxy terminal and, thus, plays an important role in the biological regulation of proline-containing neuropeptides and peptide hormones, which are recognized to be involved in learning and memory (Szeltner et al., 2000). The stilbene glycosides isolated from Boswellia papyrifera (Del.) Hochst (Burseraceae), trans-4′,5-dihydroxy-3-methoxystilbene-5-O-{α-l-rhamnopyranosyl-(1-2)-[α-l-rhamnopyranosyl-(1-6)]-β-d-glucopyranoside and trans-4′,5-dihydroxy-3-methoxystilbene-5-O-[α-l-rhamnopyranosyl-(1-6)]-β-d-glucopyranoside exhibited significant inhibition of phosphodiesterase I and xanthine oxidase (Atta-ur-Rahman et al., 2005). Triterpenes such as 3-α-acetoxy-27-hydroxylup-20(29)-en-24-oic acid, 11-keto-β-boswellic acid, β-elemonic acid, 3 α-acetoxy-11-keto-β-boswellic acid, and β-boswellic acid also exhibited prolyl endopeptidase inhibitory activities (Atta-ur-Rahman et al., 2005).

Conclusion

The present review presents an overview of medicinal plants research in Cameroon and is intended to serve as scientific baseline information for the documented plants as well as a starting point for future studies. The paper draws attention on some active metabolites and plant extracts, with the potential for new drugs or improved plant medicines. The review inevitably shows the richness of the Cameroon flora as medicinal resource and demonstrates the effectiveness of numerous traditionally used plants. Presently, there is an urgent necessity for standardization of plant-derived drugs, as their use is still empirical. There is also an urgent requirement to standardize methods and cut-off points for describing their bioactivities. Other recommendations include parallel screenings by using cytotoxicity tests to preclude non-specific cytotoxicity from being interpreted as efficient following in vitro screening. The elucidation of the mechanisms of action of biologically active extracts and compounds should be strengthened and given priority in future investigations as already shown for natural products from other parts of the world (Kong et al., 2009; Youns et al., 2010; Konkimalla and Efferth, 2010).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Authors are grateful to Dr. H.M. Poumale (Faculty of Science, University of Yaoundé I) for his support. Victor Kuete is also thankful to the Deutscher Akademische Austausch Dienst (DAAD) for the postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Mainz, Germany.

References

- Addae-Mensah I., Achenbach H. (1985). Terpenoids and flavonoids of Bridelia ferruginea. Phytochemistry 24, 1817–1819 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)82558-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adjanohoun E. J., Ahyi A. M. R., Ake Assi L., Moutsambote J. M., Mpati J., Doulou V., Baniakina J. (1988). Médecine Traditionnelle et Pharmacopée: Contribution aux études Ethnobotaniques et Floristiques en République Populaire du Congo. Paris: Rapport ACCT [Google Scholar]

- Adjanohoun J. E., Aboubakar N., Dramane K., Ebot M. E., Ekpere J. A., Enow-Orock E. G., Focho D., Gbile Z. E., Kamanyi A., Kamsu Kom J., Keita A., Mbenkum T., Mbi C. N., Mbiele A. L., Mbome I. L., Miburu N. K., Nancy W. L., Nkongmeneck B., Satabie B., Sofowora A., Tamze V., Wirmum C. K. (1996). Traditional Medicine and Pharmacopoeia: Contribution to Ethnopharmacological and Floristic Studies in Cameroon. Lagos–Nigeria: OAU/STRC [Google Scholar]

- Adu-Tutu M., Afful Y., Asante-Appiah K., Lieberman D., Hall J. B., Elvin-Lewis M. (1979). Chewing stick usage in southern Ghana. Econ. Bot. 33, 320–328 [Google Scholar]

- Agbor G. A., Kuate A., Oben J. E. (2007). Medicinal plants can be good source of antioxidant: Case study in Cameroon. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 10, 537–544 10.3923/pjbs.2007.537.544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames B. N., Shigenaga M. K., Hagen T. M. (1993). Oxidants, antioxidants and the degenerative diseases of aging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 7915–7922 10.1073/pnas.90.17.7915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammah A., Nkuo-Akenji T., Ndip R., Deas J.E. (1999). An update on concurrent malaria and typhoid fever in Cameroon. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 93, 127–129 10.1016/S0035-9203(99)90282-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. (2006). Plan stratégique national de développement et d'intégration de la médicine traditionnelle au Cameroun 2006-2010. http://www.irad-cameroon.org/Docs/Documents/1138721168 new_year_speach_SG_d%C3%A9finitif.doc (Accessed on May 04, 2010).

- Asongalem E. A., Foyet H. S., Ekobo S., Dimo T., Kamtchouing P. (2004). Antiinflammatory, lack of central analgesia and antipyretic properties of Acanthus montanus (Ness) T. Anderson. J. Ethnopharmacol. 95, 63–68 10.1016/j.jep.2004.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atta-ur-Rahman, Naz H., Fadimatou, Makhmoor T., Yasin A., Fatima N., Ngounou F. N., Kimbu S. F., Sondengam B. L., Iqbal Choudhary M. I. (2005). Bioactive constituents from Boswellia papyrifera. J. Nat. Prod. 68, 189–193 10.1021/np040142x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubreville A. (1950). Flore Forestière Soudano-Guinéene A.O.F. Cameroun Paris: A.E.F, Société d'Edition Géographique Maritime et Coloniale [Google Scholar]

- Ayafor J. F., Kimbu S. F., Ngadjui B. T. (1994). Limonoids from Curupa Carapa grandifolia (Meliaceae). Tetrahedron 50, 9343–9354 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)85511-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Babu B. H., Shulesh B. S., Padikkala J. (2001). Antioxidant and hepatoprotective effect of Acanthus ilicifolius (Acanthaceae). Fitoterapia 72, 272–277 10.1016/S0367-326X(00)00300-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett P. (2007). New data, fresh perspectives: diabetes atlas, third edition. Diabetes Voice 52, 46–48 [Google Scholar]

- Berhaut J. (1975). Flore Illustrée du Sénégal, Tome IV Dakar: Préface de M. Leopold Sendar Senghor [Google Scholar]

- Bessong P. O., Obi C. L., Igumbor E., Andreola M.-L., Litvak S. (2004). In vitro activity of three selected South African medicinal plants against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 3, 555–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickii J., Feuya Tchouya G. R., Tchouankeu J. C., Tsamo E. (2007a). The antiplasmodial agents of the stem bark of Entandrophragma angolense (Meliaceae). Afr. J. Trad. CAM 4, 135–139 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickii J., Feuya Tchouya G. R., Tchouankeu J. C., Tsamo E. (2007b). Antimalarial activity in crude extracts of some Cameroonian medicinal plants. Afr. J. Trad. CAM 4, 107–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickii J., Njifutie N., Foyere J. A., Basco L. K., Ringwald P. (2000). In vitro antimalarial activity of limonoids from Khaya grandifoliola C.D.C. (Meliaceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 69, 27–33 10.1016/S0378-8741(99)00117-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boik J. (2001). Natural Compounds in Cancer Therapy. Minnesota, USA: Oregon Medical Press; 11243668 [Google Scholar]

- Boyom F. F., Kemgne E. M., Tepongning R., Ngouana V., Mbacham W. F., Tsamo E., Amvam Zollo P. H., Gut J., Rosenthal P. J. (2009). Antiplasmodial activity of extracts from seven medicinal plants used in malaria treatment in Cameroon. J. Ethnopharmacol. 123, 483–488 10.1016/j.jep.2009.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouquet A. (1969). Féticheurs et médécines traditionnelles du Congo (Brazzaville). Paris: ORSTOM [Google Scholar]

- Brahemi G., Kona F. R., Fiasella A., Buac D., Soukupov J., Brancale A., Burger A. M., Westwell A. D. (2010). Exploring the structural requirements for inhibition of the ubiquitin E3 ligase breast cancer associated protein 2 (BCA2) as a treatment for breast cancer. J. Med. Chem. 53, 2757–2765 10.1021/jm901757t [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray D. H., Warhurst D. C., Connolly J. D., O'Neill M. J., Phillipson J. D. (1990). Plants as sources of antimalarial drugs. Part 7. Activity of some species of Meliaceae and their constituent limonoids. Phytother. Res. 4, 29–35 10.1002/ptr.2650040108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant A. T. (1966). Zulu Medicine and Medicine Men. Cape Town: Struik C [Google Scholar]

- Burkill H. M. (1985). Useful Plants of West Tropical Africa. Edinburgh: Royal Botanic Garden [Google Scholar]

- Calas M., Cordina G., Bompart J., Bari M. B., Jei T., Ancelin M. L., Vial H. (1997). Antimalarial activity of molecules interfering with plasmodium falciparum phospholipid metabolism. Structure–activity relationship analysis. J. Med. Chem. 40, 3557–3566 10.1021/jm9701886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Leal J., Dayton L., Mehra K. (2000). Public spending on health care in Africa: do the poor benefit? Bull. World Health Organ. 78, 66–74 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheek M. (2004). Thecacoris annobonae. IUCN 2009. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. http://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/45457/0 (Accessed on April 13, 2008).

- Chung H. Y., Baek B. S., Song S. H., Kim M. S., Huh J. I., Shim K. H., Kim K. W., Lee K. H. (1997). Xanthine dehydrogenase/xanthine oxidase and oxidative stress. Age (Omaha) 20, 127–140 10.1007/s11357-997-0012-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cos P., Vlietinck A. J., Vanden Berghe D., Maes L. (2006). Anti-infective potential of natural products: How to develop a stronger in vitro ‘proof-of-concept’. J. Ethnopharmacol. 106, 290–302 10.1016/j.jep.2006.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft S. L., Barrett M. P., Urbina J. A. (2005). Chemotherapy of trypanosomiases and leishmaniasis. Trends Parasitol. 21, 508–512 10.1016/j.pt.2005.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalziel J. M. (1937). The Useful Plants of West Tropical Africa. London: The Crown Agents for the Colonies [Google Scholar]

- Dieye A. M., Sarr A., Diop S. N., Ndiaye M., Sy G. Y., Diarra M., Rajraji Gaffary I., Ndiaye Sy A., Faye B. (2008). Medicinal plants and the treatment of diabetes in Senegal: survey with patients. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 22, 211–216 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2007.00563.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimo T., Fotio A. L., Nguelefack T. B., Asongalem E. A., Kamtchouing P. (2006). Antiinflammatory activity of leaf extract of Kalanchoe crenata Andr. Indian J. Phamacol. 38, 115–119 10.4103/0253-7613.24617 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dimo T., Rakotonirina S. V., Tan P. V., Azay J., Dongo E., Kamtchouing P., Cros G. (2007). Effect of Sclerocarya birrea (Anacardiaceae) stem bark methylene chloride/methanol extract on streptozotocin-diabetic rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 110, 434–438 10.1016/j.jep.2006.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dongmo A. B., Kamanyi A., Anchang M. S., Chungag-Anye Nkeh B., Njamen D., Nguelefack T. B., Nole T., Wagner H. (2001). Anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties of the stem bark extracts of Erythrophleum suaveolens (Caesalpiniaceae), Guillemin & Perrottet. J. Ethnopharmacol. 77, 137–141 10.1016/S0378-8741(01)00296-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzeufiet P. D. D., Ngeutse D. F., Dimo T., Tédong L., Ngueguim T. F., Tchamadeu M. C., Nkouambou N. C., Sokeng S. D., Kamtchouing P. (2009). Hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic effects of Irvingia gabonensis (Irvingiaceae) in diabetic rats. Pharmacologyonline 2, 957–962 [Google Scholar]

- Dzeufiet P. D. D., Tédong L., Asongalem E. A., Dimo T., Sokeng S. D., Kamtchouing P. (2006). Hypoglucaemic effect of methylène chloride/methanol root extract of Ceiba pentandra in normal and diabetic rats. Indian J. Pharmacol. 38, 194–197 10.4103/0253-7613.25807 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- EarthTrends. (2003). Biodiversity and Protected Areas-Cameroon. http://earthtrends.wri.org/pdf_library/country_profiles/bio_cou_120.pdf (Accessed on May 04, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson J. (2001). Malaria and Poverty: Opportunities to Address Malaria through Debt Relief and Poverty Reduction Strategies. www.lshtm.ac.uk/itd/dcvbu/malcon (Accessed on November 08, 2009).

- Ekwalla N., Tongo E. (2003). Nos plantes qui soignent. Doula, Cameroon: Ed I.C [Google Scholar]

- Eyong K. O., Kumar P. S., Kuete V., Folefoc G. N., Nkengfack A. E., Baskaran S. (2008). Semisynthesis and antitumoral activity of 2-acetylfuranonaphthoquinone and other naphthoquinone derivatives from lapachol. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 18, 5387–5390 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.09.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezeamuzie I. C., Ojinnake M. C., Uzygna E. O., Oji S. E. (1994). Antiinflammatory, antipyretic and antimalarial activity of a West African medicinal plant-Picralima nitida. Afr. J. Med. Sci. 23, 85–90 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairlamb A. (2003). Chemotherapy of human African trypanosomiasis: current and future prospects. Trends Parasitol. 19, 488–494 10.1016/j.pt.2003.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakeye T. O., Itiola O. A., Odelila H. A. (2000). Evaluation of the antimicrobial property of the stem bark of Picralima nitida (Apocynaceae). Phythother. Res. 14, 368–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Focho D. A., Newu M. C., Anjah M. G., Nwana F. A., Ambo F. B. (2009). Ethnobotanical survey of trees in Fundong, Northwest Region, Cameroon. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 5, 17. 10.1186/1746-4269-5-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotie J., Bohle D. S., Olivier M., Gomez M. A., Nzimiro S. (2007). Trypanocidal and antileishmanial dihydrochelerythrine derivatives from garcinia lucida. J. Nat. Prod. 70, 1650–1653 10.1021/np0702281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotio A. L., Dimo T., Ngo Lemba E., Temdie R. J., Ngueguim F., Kamtchouing P. (2009). Acute and chronic anti-inflammatory properties of the stem bark aqueous and methanol extracts of Sclerocarya birrea (Anacardiaceae). InflammoPharmacology 17, 229–237 10.1007/s10787-009-0011-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotsing M. T., Yankep E., Njamen D., Fomum Z. T., Nyasse B., Bodo B., Recio M. C., Giner R. M., Rios J. L. (2003). Identification of an Anti-Inflammatory principle from the stem bark of Millettia versicolor. Planta Med. 69, 767–770 10.1055/s-2003-42794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand M., Mavi S., Drummond R. B., Ndemera B. (1985). The Traditional Medical Practitioner in Zimbabwe. Gweru, Zimbabwe: Mambo Press [Google Scholar]

- Giner-Larza E. M., Manez S., Recio M. C., Giner R. M., Prieto J. M., Cerda-Nicolas M., Rios J. L. (2001). Oleanonic acid, a 3-oxotriterpene from Pistacia, inhibits leukotriene synthesis and has anti-inflammatory activity. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 428, 137–143 10.1016/S0014-2999(01)01290-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gondwe M., Kamadyaapa D. R., Tufts M., Chuturgoon A. A., Musabayane C. T. (2008). Sclerocarya birrea [(A. Rich.) Hochst.] [Anacardiaceae] stem-bark ethanolic extract (SBE) modulates blood glucose, glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) of STZ-induced diabetic rats. Phytomedicine 15, 699–709 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henty E. E. (1973). Weeds of New Guinea and their Control. Department of Forests, Division of Botany; Botany Bulletin. No. 7. Lae, Papua New Guinea, pp. 149–151 [Google Scholar]

- Hostettmann K., Marston A., Ndjoko K., Wolfender J. L. (2000). The potential of African plants as source of drugs. Curr. Org. Chem. 4, 973–1010 10.2174/1385272003375923 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Igoli J. O., Igoji O. G., Tor-Anylin T. O., Ogali N. O. (2005). Traditional medicinal practice amongst the Igede people of Nigeria, part II. Afr. J. Trad. CAM 2, 134–152 [Google Scholar]

- Index mundi. (2008). Cameroon Major Infectious Diseases. http://www.indexmundi.com/cameroon/major_infectious_diseases.html (Accessed on August 02, 2009).

- Irvine F. R. (1961). Woody Plants of Ghana. London: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- Iwu M. M. (1993). Handbook of African Medicinal Plants. London: CRC Press [Google Scholar]

- Jain K. N., Kulkarni K. S., Singh A. (2002). Modulation of NSAID-induced antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects by (2-adrenoceptor agonists with gastroprotective effects. Life Sci. 70, 2857–2869 10.1016/S0024-3205(02)01549-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jatsa H. B., Ngo Sock E. T., Tchuem Tchuente L. A., Kamtchouing P. (2009). Evaluation of the in vivo activity of different concentrations of Clerodendrum umbellatum poir against Schistosoma mansoni infection in mice. Afr. J. Trad. CAM 6, 216–221 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing H., Zhou X., Dong X., Cao J., Zhu H., Lou J., Hu Y., He Q., Yang B. (2010). Abrogation of Akt signaling by Isobavachalcone contributes to its anti-proliferative effects towards human cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 294, 167–177 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.01.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiofack T., Fokunang C., Guedje N., Kemeuze V., Fongnzossie E., Nkongmeneck B. A., Mapongmetsem P. M., Tsabang N. (2010). Ethnobotanical uses of medicinal plants of two ethnoecological regions of Cameroon. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2, 60–79 [Google Scholar]

- Jones K. D. J., Hesketh T., Yudkin J. (2008). Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in sub-Saharan Africa: an emerging public-health concern. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 102, 219–214 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamanyi A., Njamen D., Nkeh B. (1994). Hypoglycaemic properties of the aqueous root extract of Morinda lucida (Benth) (Rubiaceae). Studies in the Mouse. Phytother. Res 8, 369–371 10.1002/ptr.2650080612 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamgang R., Mboumi R. Y., Fondjo A. F., Tagne M. A. F., N'dille G. P. R. M., Yonkeu J. N. (2008). Antihyperglycaemic potential of the water–ethanol extract of Kalanchoe crenata (Crassulaceae). J. Nat. Med. 62, 34–40 10.1007/s11418-007-0179-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamtchouing P., Sokeng S. D., Moundipa P. F., Watcho P., Jatsa H. B., Lontsi D. (1998). Protective role of Anacardium occidentale extract against streptozotocin-induced diabetes in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 62, 95–99 10.1016/S0378-8741(97)00159-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapche G. D. W. F., Fozing C. D., Donfack J. H., Fotso G. W., Amadou D., Tchana A. N., Bezabih M., Moundipa P. F., Ngadjui B. T., Abegaz B. M. (2009). Prenylated arylbenzofuran derivatives from Morus mesozygia with antioxidant activity. Phytochemistry 70, 216–221 10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]