Abstract

γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in the body and hence GABA-mediated neurotransmission regulates many physiological functions, including those in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. GABA is located throughout the GI tract and is found in enteric nerves as well as in endocrine-like cells, implicating GABA as both a neurotransmitter and an endocrine mediator influencing GI function. GABA mediates its effects via GABA receptors which are either ionotropic GABAA or metabotropic GABAB. The latter which respond to the agonist baclofen have been least characterized, however accumulating data suggest that they play a key role in GI function in health and disease. Like GABA, GABAB receptors have been detected throughout the gut of several species in the enteric nervous system, muscle, epithelial layers as well as on endocrine-like cells. Such widespread distribution of this metabotropic GABA receptor is consistent with its significant modulatory role over intestinal motility, gastric emptying, gastric acid secretion, transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation and visceral sensation of painful colonic stimuli. More intriguing findings, the mechanisms underlying which have yet to be determined, suggest GABAB receptors inhibit GI carcinogenesis and tumor growth. Therefore, the diversity of GI functions regulated by GABAB receptors makes it a potentially useful target in the treatment of several GI disorders. In light of the development of novel compounds such as peripherally acting GABAB receptor agonists, positive allosteric modulators of the GABAB receptor and GABA producing enteric bacteria, we review and summarize current knowledge on the function of GABAB receptors within the GI tract.

Keywords: GABAB, motility, visceral hypersensitivity, secretion, baclofen, allosteric modulator, agonist

Introduction

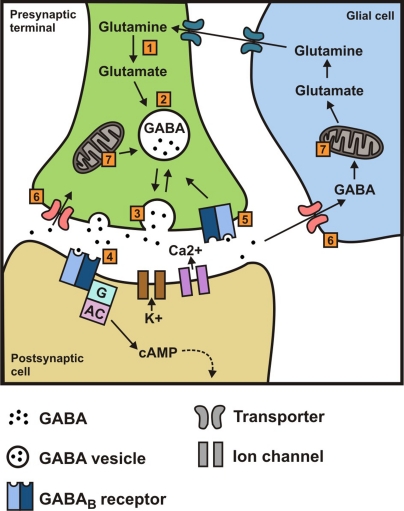

γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in the body and hence GABA-mediated neurotransmission regulates many physiological functions, including those in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. There are two major classes of GABA receptors and these are classified as either ionotropic GABAA (including GABAC) receptors or metabotropic GABAB receptors (Barnard et al., 1998; Bormann, 2000; Bowery et al., 2002; Cryan and Kaupmann, 2005). It is now over 30 years since these latter receptors were first pharmacologically characterized, and baclofen was identified as a selective GABAB receptor agonist. GABAB receptors modulate neurotransmitter release presynaptically by depressing Ca2+ influx via voltage-activated Ca2+ channels (Bowery et al., 2002; Figure 1) while postsynaptic GABAB receptors couple mainly to inwardly rectifying K+ channels (Luscher et al., 1997) and mediate slow inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (Bowery et al., 2002; Figure 1). As well as expression in the brain, GABAB receptors are also abundantly expressed in the GI tract, therefore in this review we will summarize current knowledge on the function of GABAB receptors in the GI tract.

Figure 1.

(1) Synthesis of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) from glutamine/glutamate (catalyzed by l-glutamate decarboxylase (GAD); (2) transport and storage of GABA; (3) release of GABA by exocytosis; (4) binding to GABAB receptors and subsequent downstream effects mediated via a G protein and/or cAMP to K+ and Ca2+ channels; (5) binding to presynaptic receptors; (6) reuptake in presynaptic terminal and uptake by glia; (7) transamination of GABA to α-ketoglutarate (catalyzed by GABA transaminase, GABA-T), thereby regenerating glutamate and glutamine; glial glutamine then re-enters the neuron.

GABAB receptor proteins

The first GABAB receptor cDNAs were isolated only in 1997 (Kaupmann et al., 1997). The identification of a second GABAB receptor protein soon after led to the discovery that native GABAB receptors are heterodimers composed of two subunits, GABAB1 and GABAB2 (reviewed in Calver et al., 2002; Bettler et al., 2004). In the brain two predominant, differentially expressed splice variants are transcribed from the Gabbr1 gene, GABAB1a and GABAB1b, which are conserved in different species including humans (Kaupmann et al., 1997; Bischoff et al., 1999; Fritschy et al., 1999). The human GABAB1 gene encodes a third isoform, GABAB1c, a functional role for which has yet to be determined, although it may play a role in the developing human brain (Calver et al., 2002). In the human GI tract there appears to be a similar expression pattern for both GABAB1a and GABAB1b splice variants, with little or no expression of GABAB1c (Calver et al., 2000). The GABAB1a and GABAB1b isoforms differ by the insertion of a pair of tandem “Sushi” domains, which are potentially involved in protein–protein interactions, in the N-terminus of GABAB1a, and differentiate this isoform from GABAB1b (Calver et al., 2002). In the GABAB1b subtype, the N-terminal extracellular domain is the ligand binding domain and differs from the GABAB1a splice variant at the N-terminus by the presence of a tandem pair of CP modules, while the GABAB1c splice variant differs in the fifth transmembrane region and the second extracellular loop by an additional 31 amino acids (Blein et al., 2000). Human GABAB1c is similar to GABAB1a yet lacks one “Sushi” repeat because the splice machinery skips exon 4 and its expression pattern parallels that of GABAB1a (Bettler et al., 2003). It appears at least in some brain regions that GABAB1a and GABAB1b can participate, through heterodimerization with GABAB2, in the formation of both pre- and post-synaptic receptors. Similar heterodimerization has also been postulated to occur in the GI tract between GABAB1 and GABAB2 (Kawakami et al., 2004) and is further supported by recent immunohistochemical data obtained for both subunits in the upper GI tract (Torashima et al., 2009).

Partial cDNAs corresponding to putative GABAB2 splice variants have also been isolated (Clark et al., 2000). However, investigation of the Gpr51 (Gabbr2) gene structure did not provide evidence that these cDNAs correspond to additional GABAB2 splice variants (Martin et al., 2001). Furthermore, the absence of an expression profile for GABAB2a, GABAB2b, and GABAB2c in the human GI tract would suggest such splice variants do not play a significant role in GI function (Calver et al., 2000). Therefore, it seems likely that in the brain two major populations of heteromeric GABAB receptors exist, GABAB1a,2 and GABAB1b,2. The behavioral phenotypes of mice with targeted deletions of either the GABAB1 (Prosser et al., 2001; Schuler et al., 2001; Mombereau et al., 2004) or the GABAB2 subunits (Gassmann et al., 2004; Mombereau et al., 2005) are similar and corroborate the in vitro experiments demonstrating that functional GABAB receptor responses are dependent on the heterodimerization of GABAB1 and GABAB2 subunits. Additionally, GABA-mediated inhibition of GI motility appears to be dependant on the GABAB1 receptor subunit (Sanger et al., 2002). The more recent development of mice lacking both the GABAB1a and GABAB1b receptor splice variants have been generated (Vigot et al., 2006) and are proving to be very useful in understanding the role of these receptor isoforms in physiological processes (Jacobson et al., 2006, 2007; Vigot et al., 2006), however, such studies have yet to be extended into the GI tract.

Localization of GABA and GABAB Receptors in the Gastrointestinal Tract

γ-Aminobutyric acid is located throughout the GI tract and has been localized in enteric nerves as well as in endocrine-like cells implicating GABA as both a neurotransmitter and an endocrine mediator in the GI tract. The primary synthesis pathway for enteric GABA is catalyzed by l-glutamate decarboxylase (GAD; Figure 1) using the substrate glutamate, and has been localized in both Dogiel type I and Dogiel type II enteric neurons (for a review see Krantis, 2000). High affinity plasma membrane GABA transporters (GAT) are also present in the rat GI tract and have been localized to both enteric glia (GAT2) and myenteric neurons (GAT3) of the duodenum, ileum, and colon (Fletcher et al., 2002). In the enteric nervous system (ENS) approximately 5–8% of myenteric neurons, which largely regulate GI motility, contain GABA, and in the colon it predominantly co-localizes with the inhibitory neurotransmitter somatostatin, but also to a lesser extent with enkephalins and nitric oxide (Krantis, 2000). GABA has also been implicated in the regulation of intestinal fluid and electrolyte transport by virtue of its presence in submucosal nerve cell bodies and mucosal nerve fibers (Krantis, 2000). Therefore, it is not surprising that GABA plays a multifunctional role in the regulation of GI activity. In addition to the ENS and endocrine-like sources of GABA, newer endeavors have adapted Bifidobacteria, found in the intestines of breast-fed children and healthy adults, to increase GABA production by genetically increasing GAD activity (Park et al., 2005), and GABA-producing bacteria have been exploited in the production of GABA-containing functional foods such as fermented goats milk (Minervini et al., 2009). Genetically exploiting commensal bacteria to elevate intestinal GABA production allows for local delivery of GABA to the GI tract and may therefore be of some therapeutic use in regulating epithelial proliferation (see GABAB Receptors and Gastrointestinal Carcinogenesis) or may directly alter intestinal secretory activity. Although the current literature would suggest that GABA would need to access the enteric plexi to exert an effect on the later (see GABAB Receptor Modulation of Intestinal Electrolyte Transport).

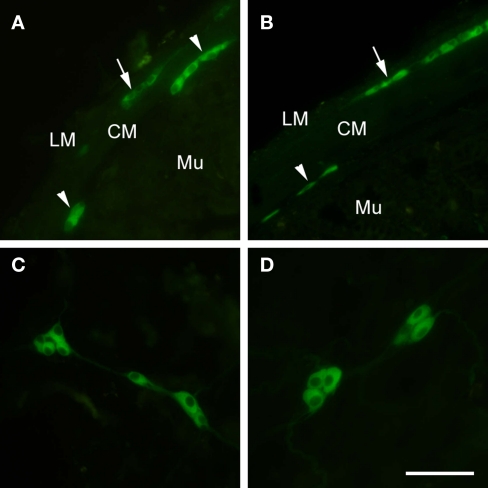

Nakajima et al. (1996) demonstrated using an antibody generated against amino-terminal blocked baclofen, GABAB receptor immunoreactivity in the rat ENS, muscle and epithelial layers. The 80-kDa antigen against which the antibody was raised was subsequently demonstrated to bind GABA and baclofen, but not the GABAA antagonist, bicuculline (Nakayasu et al., 1993). Our own studies in mouse intestine, using a different GABAB1 receptor antibody (Ab25; Engle et al., 2006) corroborated the findings of Nakajima et al. (1996) with respect to localization of GABAB receptors on both submucosal and myenteric neurons in the ENS, however we did not detect any mucosal staining in this species (Casanova et al., 2009). In the rat mucosal epithelium, GABAB receptor positive cells were observed along the length of the GI tract from the gastric body to the colon, decreasing in number in the oral to anal direction, on cells that were morphologically similar to enteroendocrine cells. Both gastric and intestinal regions displayed mucosal GABAB immunoreacticity, however gastric GABAB-positive cells tended to contain somatostatin, in contrast to duodenal GABAB positive cells which stained positively for serotonin (Nakajima et al., 1996). Therefore, the functional effects of GABAB receptors are likely to differ along the GI tract, and are likely to be dependant on its colocalization with prominent enteroendocrine cell mediators such as somatostatin and serotonin. Neural GABAB-positive fibers were observed in the muscle layers of the rat GI tract, and both plexi of the ENS (Nakajima et al., 1996). In the myenteric plexus at least 50% of GABAB positive neurons display NADPH-diaphorase activity (Nakajima et al., 1996) suggesting that GABAB receptors may directly modulate inhibitory, nitric oxide-driven neurotransmission. By taking advantage of newly developed transgenic mice expressing GABAB1a and GABAB1b subunits fused to the enhanced green fluorescence protein (eGFP) we also immunohistochemically localized the GABAB1 receptor subunit to both myenteric and submucosal neurons in mouse colon and ileum (Figure 2). Similar to our studies with an anti-GABAB1 antibody, we did not detect any enteroendocrine-like staining for the GABAB receptor subtype in this species (Casanova et al., 2009).

Figure 2.

Fluorescence immunohistochemistry using anti-eGFP antibodies revealed GABAB1-eGFP localization in the submucosal (arrowheads) and myenteric plexus (arrows) of GB1−/− mice modified to express GABAB1a and GABAB1b subunits fused to the enhanced green fluorescence protein (eGFP) using a modified bacterial artificial chromosome containing the GABAB1 gene (BAC+/+; Casanova et al., 2009) in mouse ileum (A) and colon (B), GABAB1-eGFP was not detected in either the epithelial layer or enteroendocrine cells of GB1−/−, BAC+/+ ileum and colon (A,B). Whole mount preparations of ileum (C) and colon (D) revealed a cytoplasmic, non-nuclear, distribution of GABAB1-eGFP in enteric neurons of GB1−/−, BAC+/+ mice. Scale bars = 100 μm. LM, longitudinal muscle; CM, circular muscle; Mu, mucosa. Adapted from Casanova et al. (2009).

Analysis of GABAB receptor subunit expression has been examined in human small intestine and stomach (Calver et al., 2000), rat small and large intestine (Castelli et al., 1999) as well as dog intestine (Kawakami et al., 2004). In the human GI tract GABAB1 and GABAB2 subunits are differentially expressed (Calver et al., 2000) with the GABAB1 receptor subunit, and its splice variants GABAB1a and GABAB1b predominating. GABAB2 on the other hand, irrespective of the splice variant examined, was undetectable in either region of the human GI tract (Calver et al., 2000). Despite the initial findings of Calver et al. (2000) subsequent studies have identified GABAB2 message in the human lower esophageal sphincter (LES), cardia and corpus (Torashima et al., 2009) as well as in dog intestine (Kawakami et al., 2004). Furthermore, immunohistochemical analysis identified GABAB2 protein on myenteric neurons in human LES and gastric corpus (Torashima et al., 2009).

GABAB Receptors and Gastrointestinal Function

GABAB-induced synthesis and release of enteric neurotransmitters and entorocromaffin cell-derived serotonin

Microdialysis sampling of myenteric plexus neurotransmitter release demonstrated a significant inhibitory effect of the GABAB receptor agonist, baclofen on canine intestinal acetylcholine (ACh) release and this was sensitive to GABAB receptor antagonism (Kawakami et al., 2004). Of particular note, in this species at least, was the sensitivity of ACh release (and motility) to the GABAB receptor antagonist alone (Kawakami et al., 2004). Therefore, in the canine ileum it would appear that GABAB receptor activation is inhibitory and that GABA via GABAB receptors tonically inhibits excitatory ACh release. In contrast, release of the inhibitory neurotransmitter, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide from rat colon was insensitive to inhibition by the GABAB receptor antagonist, phaclofen (Grider and Makhlouf, 1992). Similarly, in guinea-pig ileum the production of electrically induced citrulline, as a marker for nitric oxide synthase activity, was insensitive to GABAB receptor modulation with baclofen, but was reduced by the GABAA agonist, muscimol (Hebeiss and Kilbinger, 1999). Therefore, with the caveat of species differences, it would appear that GABAB receptors exert an inhibitory effect on release of ACh, without any significant effect on inhibitory neurotransmitter release or synthesis.

Both GABAA and GABAB receptors have also been shown to regulate the release of enterochromaffin cell-derived serotonin from guinea-pig small intestine, although they appear to have opposing effects (Schworer et al., 1989). Baclofen-induced, GABAB-driven, inhibition of serotonin release occurs via a tetrodotoxin (TTX) insensitive, non-neural pathway while GABAA receptor activation causes a predominant TTX-sensitive, muscarinic receptor-driven release of serotonin (Schworer et al., 1989). Therefore, the potential exists for GABAB receptors to indirectly regulate ENS activity via release of enteroendocrine-cell derived mediators such as serotonin.

GABAB receptor modulation of intestinal motility

γ-Aminobutyric acid, and as such GABA receptor-mediated effects on GI motility are dependant on an intact ENS as isolated rat smooth muscle cells are unresponsive to addition of GABA (Grider and Makhlouf, 1992). Both electrically induced ileal twitch responses and spontaneous colonic smooth muscle contraction (cholinergic in nature) are sensitive to inhibition by baclofen in the guinea-pig (Ong and Kerr, 1982; Allan and Dickenson, 1986; Minocha and Galligan, 1993; Table 1). In vitro data suggest that this GABAB-mediated inhibitory effect is countered by GABAA receptors, as GABAA receptor activation caused a right-ward shift in the ED50 for baclofen on the ileal twitch response, and this was recovered to some extent in the presence of the GABAA receptor antagonist, bicuculline (Allan and Dickenson, 1986). In addition to which complex GABAB receptor-dependant signaling pathways, in the guinea-pig ileum at least, have been identified and involve GABAB receptor-mediated inhibition of somatostatin-sensitive cholecystokinin-induced contraction (Roberts et al., 1993; Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of GABAB receptor-induced effects on gastrointestinal motility.

| Region | Species | Baclofen induced-effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duodenum/jejunum | Human | TTX sensitive inhibition of spontaneous and DMPP-induced contraction | Gentilini et al. (1992) |

| Rat | Reduction in electrically evoked cholinergic contraction | Krantis and Harding (1987) | |

| Disruption of migrating motor complex activity (i.v. administration) | Fargeas et al. (1988) | ||

| Atropine-sensitive increase in migrating motor complex activity (i.c.v. administration) | |||

| Ileum | Guinea-pig | Decrease in electrically evoked (cholinergic) twitch response | Ong and Kerr (1982) and Marcoli et al. (2000) |

| Relaxation (all levels of the intestine) Inhibition of somatostatin inhibitory activity on cholocystokinin-induced contraction (cholinergic) | Ong and Kerr (1987) Roberts et al. (1993) | ||

| TTX- and hyoscine-sensitive relaxation (basal) and hyoscine-sensitive relaxation following histamine and prostaglandin F2α stimulation | Giotti et al. (1983) | ||

| Inhibition of electrically stimulated NO-mediated relaxation | Kilbinger et al. (1999) | ||

| Mouse | Inhibition of electrically evoked contraction (GABAB1+/+) Loss of baclofen-induced relaxation (GABAB1−/−) | Sanger et al. (2002) | |

| Cat | Contraction of longitudinal muscle (distal and terminal ileum; modest if any sensitivity to atropine and TTX) and no effect on circular muscle activity | Pencheva et al. (1999) | |

| No effect (proximal ileum) on longitudinal or circular muscle activity | |||

| Intestine | Dog | Reduction of circular muscle motor activity coupled with a decrease in ACh release (intra arterial administration) | Kawakami et al. (2004) |

| Colon | Human | No effect | Gentilini et al. (1992) |

| Guinea-pig | Decrease in fecal pellet expulsion and TTX-sensitive relaxation | Ong and Kerr (1982) | |

| Decrease in basal and physostigmine-induced tone (i.v. administration) | Giotti et al. (1985) | ||

| TTX and scopolamine-sensitive relaxation | Giotti et al. (1985) and Minocha and Galligan (1993) | ||

| Rat | Increase in electrically evoked cholinergic and non-cholinergic circular muscle contraction that is sensitive to nicotinic receptor blockade | Bayer et al. (2003) | |

| Rabbit | Modest decrease in resting tone and inhibition of electrically-induced (cholinergic) contraction. Inhibition of NANC neurotransmission and decreased transit | Tonini et al. (1989) |

ACh, acetylcholine; DMPP, dimethylphenylpiperazinium; i.v. intravenous; i.c.v. intracerbroventricular; NANC, non-adrenergic non-cholinergic; NO, nitric oxide; TTX, tetrodotoxin. Unless otherwise noted in italicize, all drug additions were to in vitro preparations.

In the human GI tract spontaneous activity of jejunal longitudinal muscle is sensitive to inhibition by both GABA and baclofen. However, spontaneous colonic activity was insensitive to GABAergic modulation (Gentilini et al., 1992) suggesting that GABAB receptor-mediated inhibition predominates in the small intestine of humans. However, in other species GABAB receptors have been demonstrated to alter colonic motor activity. For example, desensitization of GABAB receptors with baclofen, thereby relieving GABAB-induced effects on motility, resulted in decreased colonic fecal pellet output in the guinea pig (Ong and Kerr, 1982; Table 1), potentially due to dysregulation of cholinergic activity and peristalsis as suggested by the authors, or a disinhibition of inhibitory activity. In contrast to the guinea-pig colon, the propulsive velocity of a distended balloon along rabbit colonic preparations was significantly reduced by GABAB receptor activation with baclofen, consistent with an inhibitory effect of this receptor on excitatory neurotransmission (Tonini et al., 1989; Table 1). In the same species, baclofen had a minor inhibitory effect on colonic longitudinal muscle tone but a more significant inhibitory effect on TTX- and hyoscine-sensitive electrically stimulated responses, suggesting that the inhibitory effects of the GABAB agonist on colonic activity in the rabbit is dependant on cholinergic neurotransmission (Tonini et al., 1989; Table 1). Consistent with modulation of cholinergic enteric nerves, baclofen decreases both GABAB receptor-induced relaxation of guinea-pig ileal (Giotti et al., 1983) and colonic (Giotti et al., 1985) longitudinal muscle via a TTX-sensitive, cholinergic pathway and in vivo inhibited physostigmine-induced colonic tone (Giotti et al., 1985; Table 1). GABA receptor-induced relaxation appears to be mediated predominantly via GABAB receptors in guinea-pig colon, as less than 10% of the GABA-induced relaxant effect is sensitive to GABAA receptor blockade (Giotti et al., 1985). However, there is also evidence for GABAA receptor-mediated activation of inhibitory pathways in guinea-pig colon (Minocha and Galligan, 1993) which one would expect to potentiate GABAB-mediated relaxation. Non-adrenergic non-cholinergic inhibitory responses also display sensitivity to GABAB receptor activation in the rabbit (Tonini et al., 1989; Table 1), indicative of a co-ordinated regulatory role for GABAB receptors in the modulation of peristalsis in this species.

The availability of GABAB subunit receptor deficient mice has led to further characterization of GABAB receptor-mediated effects in the GI tract (Sanger et al., 2002). Baclofen-induced inhibitory responses were observed in wildtype mouse intestine following electrical stimulation, but were absent in GABAB1 subunit deficient animals (Sanger et al., 2002). This unresponsiveness to baclofen does not appear to be due to an overt dysregulation of ileal function in GABAB1 mutant mice as these animals respond in a similar manner as wildtype animals to both electrical and cholinergic stimulation (Sanger et al., 2002; Table 1). Therefore, the functional dependence of GABAB receptors in the mouse is dependant on the GABAB1 subunit, and this finding is consistent with the preferential expression of this subunit in the GI tract of several species, including humans (Castelli et al., 1999; Calver et al., 2000; Kawakami et al., 2004).

As well as having a peripheral site of action, GABA can exert effects on GI motility via central mechanisms (Fargeas et al., 1988). In unanesthetized rats intracerebroventricular administration of baclofen had a stimulatory effect on GABAB receptor- and atropine-sensitive migrating myoelectric complexes (MMC) (Fargeas et al., 1988; Table 1). While seemingly in disagreement with in vitro data, or data from anesthetized animals, which point toward a peripheral inhibitory effect for GABAB receptors in the GI tract, the authors suggest that this enhancement of MMC activity may represent baclofen-induced adaptation of vagal efferent activity.

GABAB receptor modulation of intestinal electrolyte transport

Despite localization of GABAB receptors in the submucosal plexus of rat (Nakajima et al., 1996) and mouse (GABAB1; Casanova et al., 2009) intestine, they do not appear to be involved in the regulation of electrolyte transport. In guinea-pig intestine, only GABAA receptor activation, but not baclofen, mimicked GABA-induced elevations in short-circuit current (MacNaughton et al., 1996). A similar bias toward GABAA receptor-mediated modulation of chloride ion-dependant secretion was also observed in rat small intestine (Hardcastle et al., 1991). However, in this species the GABA-induced effect was dependent on the presence of intact myenteric neurons, suggesting a myenteric reflex is involved in initiating the GABA-induced secretory response (Hardcastle et al., 1991). However, given the paucity of data in this area it is difficult to draw a firm conclusion on the role of GABAB receptor modulation of intestinal ion transport which may vary among intestinal regions and across species.

GABAB receptors and gastrointestinal afferent signaling and nociception

Vagal afferent fibers display sensitivity to baclofen and this response is, as expected, sensitive to GABAB receptor antagonism (Page and Blackshaw, 1999). Further investigation of this vagal afferent pathway elucidated GABAB receptor-mediated opening of K+, and closing of Ca2+ channels as contributing to the inhibitory effect of GABA on afferent activity, although this inhibitory effect varied dependent on the sensitivity of the fibers to mucosal, tension or tension-mucosal stimulation, in addition to which Ca2+- and K+-independent pathways were also identified (Page et al., 2006). In addition to vagal afferents, GABAB receptors also regulate spinal afferent signaling (Hara et al., 1990, 1999; Sengupta et al., 2002). Intrathecal injection of baclofen significantly reduced the threshold response to colorectal distension (CRD) in a dose-dependant manner (Hara et al., 1999). Furthermore, when co-administered with morphine, the anti-nociceptive effect of the later was potentiated, indicative of a GABAB/μ-opiod receptor interaction, which the authors suggest may involve synergistic activation of cAMP and potentiation of the anti-nociceptive effects of both GABA and morphine (Hara et al., 1999). A similar potentiation of the baclofen-induced effect on visceral pain was also observed with the Ca2+ channel blocker, diltiazem (Hara et al., 2004). In addition to acting synergistically with morphine and diltiazem, both studies also demonstrated that intrathecal administration of baclofen alone was sufficient to reduce the visceral pain response to CRD (Hara et al., 1999, 2004). These functional data are consistent with subsequent findings describing baclofen-sensitive electrical activity of S1 dorsal roots following pelvic nerve stimulation during CRD (Sengupta et al., 2002).

Moreover, systemic intravenous (i.v.) administration of baclofen to rats also significantly reduced the visceral pain response, suggesting the GABAB agonist can potentially exert its anti-nociceptive effects at sites outside the central nervous system, including in the GI tract (Brusberg et al., 2009). The same authors also demonstrated that the positive allosteric modulator of the GABAB receptor, CGP7930 also displayed efficacy in reducing CRD-induced effects on the visceromotor response, blood pressure, and heart rate following i.v. administration (Brusberg et al., 2009). However, the efficacy of CGP7930 was less than that of baclofen (Brusberg et al., 2009), potentially as its mechanism of action as an allosteric modulator is dependant on the levels of endogenous GABA or GABA tone. In a similar manner to baclofen, CGP7930 does not appear to alter colonic compliance (Brusberg et al., 2009), suggesting the anti-nociceptive effect of CGP7930 is not due to increased accommodation, as a result of muscle relaxation, of the distension stimulus.

In addition to decreasing CRD-induced pain responses, baclofen also alters gut to brain signaling following peripheral colonic inflammation (Lu and Westlund, 2001). Mustard oil-induced colonic inflammation significantly enhanced spinal cord expression of the early gene product Fos, and this response was sensitive to inhibition by baclofen (Lu and Westlund, 2001), suggesting a dampening of afferent signaling from the periphery to the central nervous system. Additionally, baclofen pretreatment per se, as well as in the presence of mustard oil, concomitantly increased activity in the rostral nucleus tractus solitarius suggesting that activation of descending anti-nociceptive autonomic pathways or an inhibition of inhibitory activity may also occur, resulting in an enhancement of Fos activity (Lu and Westlund, 2001). Therefore, GABAB receptor agonists have the potential to exert a dual effect in the GI tract in response to noxious physical or chemical stimuli by decreasing afferent signaling and enhancing anti-nociceptive outflow.

GABAB receptor-mediated regulation of gastric motility, emptying, and acid secretion

Baclofen exerts a vagus nerve-dependant dual effect on gastric motility that involves an increase in gastric pressure as a result of an inhibition of non-adrenergic non-cholinergic inhibitory neurons in the gastric corpus, as well as an atropine-sensitive stimulation of rhythmic contractions in both the corpus and antrum (Andrews et al., 1987). Moreover, independent of innervation by the central nervous system, peripheral GABAB receptor activation induces TTX- and atropine-sensitive gastric contractility in vitro (Rotondo et al., 2010), suggesting that baclofen locally increases gastric tone through activation of intrinsic cholinergic neurons. Not unexpectedly then, GABAB receptors have been shown to regulate gastric emptying (in mouse; Symonds et al., 2003). However, this was dependant on the consistency of the diet consumed and on the dose of baclofen administered (Symonds et al., 2003). Lower doses significantly increased gastric emptying of a solid meal, but decreased emptying of a liquid meal at a higher dose (Symonds et al., 2003). This divergent effect of baclofen reflects the different mechanisms that underlie gastric emptying of solid and liquid meals. In a model of delayed gastric emptying, induced by central and peripheral administration of dipyrone, intracerebroventricular baclofen dose-dependently reversed dipyrone-induced gastric retention (Collares and Vinagre, 2005).

Given the evidence for central and peripheral regulation of gastric cholinergic neurons by GABAB receptors, it is perhaps not surprising that GABA and GABAB receptors might also influence cholinergic-induced gastric acid secretion. In keeping with such a hypothesis baclofen, or the GABA mimetic PCP-GABA, induce an increase in gastric acid secretion beyond that induced by histamine and cholinergic agonism alone (Goto and Debas, 1983). This effect occurs independently of GABAA receptors (Hara et al., 1990; Yamasaki et al., 1991) and is accompanied by an increase in vagal cholinergic outflow (Yamasaki et al., 1991). Consistent with such a vagal-cholinergic pathway, systemic baclofen-induced acid secretion (and gastric motility) was inhibited by both atropine and vagotomy (Andrews and Wood, 1986). Similar effects have also been observed in mice, and are mimicked by the GABAB receptor agonist, SKF-97541 (Piqueras and Martinez, 2004). As predicted by earlier studies Piqueras and Martinez (2004), demonstrated a vagally mediated atropine-sensitive regulation of acid secretion in mouse stomach, however they also demonstrated that GABAB receptor-induced acid secretion was sensitive to neutralization of gastrin and enhanced in the presence of a somatostatin neutralizing antibody; the former suggesting that GABAergic induced gastric acid secretion occurs via a neurohumoral route which is sensitive to feedback inhibition by the later. Other studies have identified baclofen-induced acid secretion as also been partially dependant on histamine H2 receptors, and identified extravagal effects of baclofen on gastric acid secretion in vagotomized rats (Blandizzi et al., 1992).

GABAB Receptors as a Therapeutic Target in the Gastrointestinal Tract

GABAB receptors and transient lower esophageal relaxation

Modulation of transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation (TLESR) and the application of GABAB agonists in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is of particular translational relevance, being the only case of the use of GABAB receptors as a clinical target (as recently reviewed by Lehmann, 2009; Lehmann et al., 2010). In pre-clinical studies, intravenous and intragastric administration of baclofen displayed almost equal potencies with respect to inhibition of TLESRs in the dog, despite a concomitant increase in gastric pressure, and these effects were sensitive (to some extent) to GABAB receptor antagonism and absent when the S enantiomer of baclofen was used (Lehmann et al., 1999). Similar inhibition of TLESRs by baclofen was observed in ferrets (Blackshaw et al., 1999), and the site of action for the GABAB-mediated effect on TLESR in this species was later demonstrated to involve inhibition of vagal motor output, via GABAB (GBABB1) receptors (McDermott et al., 2001), and thought to involve subsequent inhibition of non-adrenergic non-cholinergic activity. However, inhibition of mechano-sensitive gastric vagal afferents and their central synaptic connections with brain stem neurons must also be considered as a site of action for GABAB receptor agonists in the treatment of GERD. In parallel clinical trials, conducted in and around the same period as pre-clinical studies, data demonstrated that baclofen increased lower esophageal pressure and decreased TLESRs and the number of reflux episodes in healthy human subjects (Lidums et al., 2000). A later study conducted in patients suffering from GERD, similarly demonstrated a significant effect of orally administered baclofen on esophageal pH and on the incidence of reflux episodes and TLESRs, however in this particular study patients did not report any improvement in reflux symptoms (van Herwaarden et al., 2002). Nonetheless, a subsequent study indicated that 4 week treatment with baclofen significantly decreased the intensity of a number of symptoms associated with reflux, including fasting and post prandial epigastric pain, day- and night-time heartburn and regurgitation (Ciccaglione and Marzio, 2003). Despite its efficacy in relieving GERD symptoms, one of the common features associated with baclofen administration in GERD patients is the development of centrally mediated side-effects, with over 80% of baclofen-treated patients reporting neurological events such as dizziness (van Herwaarden et al., 2002). In order to overcome such central side-effects a number of GABAB receptor agonists have been developed and tested for efficacy in reducing TLESRs, these include the GABAB agonists AZD9343 (Beaumont et al., 2009), AZD3355 (lesogaberan; Boeckxstaens et al., 2010a,b) and a prodrug of the R enantiomer of baclofen, XP19986 (arbaclofen placarbil; Gerson et al., 2010). The pre-clinical data for AZD9343 favored a decreased side-effect profile as its pharmacology suggested the GABAB agonist did not readily cross the blood brain barrier and was sequestered intracellularly via a GABA-carrier independent mechanism (Lehmann et al., 2008). Although AZD9343 reduced the number of TLESRs in healthy volunteers, significant side-effects unfortunately remained and included drowsiness and paresthesia (Beaumont et al., 2009). However, other side effects such as the incidence of dizziness in AZD9343-treated subjects were less than those reported in the baclofen-treated group (Beaumont et al., 2009). Of most promise currently in terms of efficacy in treating the symptoms of GERD and having a reduced side-effect profile is lesogaberan. Its pharmacology differs from that of AZD9343 in that lesogaberan displays affinity for GABA carriers, thereby reducing GABAB-mediated central side effects (Lehmann et al., 2009). Initial trials with lesogaberan in healthy male subjects were positive, with lesogaberan and baclofen decreasing the number of TLESRs and reflux episodes to a similar extent (Boeckxstaens et al., 2010a). As predicted by pre-clinical studies, subjects treated with lesogaberan had a similar side-effect profile to that observed in those treated with placebo (Boeckxstaens et al., 2010a). Lesogaberan similarly reduced TLESRs in patients with GERD and no significant differences in the side-effect profile between placebo and lesogaberan were observed (Boeckxstaens et al., 2010b). Therefore therapeutically exploiting affinity for GABA-carriers may prove to be beneficial in reducing the central side effects associated with baclofen.

GABAB receptors and gastrointestinal carcinogenesis

The GABAB-induced effects on gastric pH may potentially inhibit chemically-induced gastric carcinogenesis observed as a decrease in the incidence and number of gastric tumors (Tatsuta et al., 1990). However, this remains unproven, and the exact mechanism underlying the baclofen-induced decrease in proliferation of antral mucosa has yet to be determined (Tatsuta et al., 1992). In the rat lower GI tract, the same group also observed a GABAB-induced inhibitory effect on colon tumor growth, but not incidence (Tatsuta et al., 1992).

Summary and Conclusions

The diversity of GI functions regulated by GABAB receptors make it a potentially useful target in the treatment of several GI disorders, but may also limit its therapeutic application due to off target side effects, both in the GI tract and centrally. For example GERD patients and healthy volunteers treated with baclofen reported adverse effects of a neurological nature that included drowsiness and dizziness (Lidums et al., 2000; van Herwaarden et al., 2002; Ciccaglione and Marzio, 2003). However, the development of peripherally acting compounds such as lesogaberan, which by virtue of its affinity for GABA carriers (Lehmann et al., 2009) limits its effects at central GABAB receptors, may well overcome the disadvantages associated with traditional GABAB agonists. Lesogaberan, like baclofen, displays efficacy in the treatment of GERD (Boeckxstaens et al., 2010a,b), but has yet to be tested in other GI disorders where targeting peripheral GABAB receptors could also be therapeutically useful, i.e., in motility disorders. Furthermore, over the last several years a number of positive allosteric modulators of the GABAB receptor have been developed (Urwyler et al., 2001, 2003; Malherbe et al., 2008). One of which, CGP7930, reduces the visceral pain response induced by CRD (Brusberg et al., 2009) and may therefore be therapeutically useful in the treatment of functional bowel disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome where visceral pain is a predominant and debilitating symptom. These modulators offer advantages over traditional GABAB agonists, such as baclofen, as their actions occur following enhancement of endogenous GABA release or transmission, thereby limiting the side-effects that are normally associated with traditional agonist treatment. More novel strategies for delivering GABA to the GI tract in the form of engineered bacteria, such as GAD transfected Bifidobacterium longum (Park et al., 2005), or the development of GABA containing functional foods (Minervini et al., 2009) are in their infancy, but may offer potential in treating GI conditions that are GABA or GABAB receptor-sensitive.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The Alimentary Pharmabiotic Centre and the authors (Niall P. Hyland and John F. Cryan) receive research support from GlaxoSmithKline.

Acknowledgments

The Alimentary Pharmabiotic Centre is a research centre funded by Science Foundation Ireland (SFI), through the Irish Government's National Development Plan. The authors and their work were supported by SFI (grant no.s 02/CE/B124 and 07/CE/B1368). John F. Cryan is also funded by European Community's Seventh Framework Programme; Grant Number: FP7/2007-2013, Grant Agreement 201714. The authors would like to thank Dr Marcela Julio-Pieper for contributing to the artwork in this manuscript.

References

- Allan R. D., Dickenson H. W. (1986). Evidence that antagonism by delta-aminovaleric acid of GABAB receptors in the guinea-pig ileum may be due to an interaction between GABAA and GABAB receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 120, 119–122 10.1016/0014-2999(86)90650-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews P. L., Bingham S., Wood K. L. (1987). Modulation of the vagal drive to the intramural cholinergic and non-cholinergic neurones in the ferret stomach by baclofen. J. Physiol. 388, 25–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews P. L., Wood K. L. (1986). Systemic baclofen stimulates gastric motility and secretion via a central action in the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 89, 461–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard E. A., Skolnick P., Olsen R. W., Mohler H., Sieghart W., Biggio G., Braestrup C., Bateson A. N., Langer S. Z. (1998). International Union of Pharmacology. XV. Subtypes of gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptors: classification on the basis of subunit structure and receptor function. Pharmacol. Rev. 50, 291–313 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer S., Jellali A., Crenner F., Aunis D., Angel F. (2003). Functional evidence for a role of GABA receptors in modulating nerve activities of circular smooth muscle from rat colon in vitro. Life Sci. 72, 1481–1493 10.1016/S0024-3205(02)02413-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont H., Smout A., Aanen M., Rydholm H., Lei A., Lehmann A., Ruth M., Boeckxstaens G. (2009). The GABA(B) receptor agonist AZD9343 inhibits transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxations and acid reflux in healthy volunteers: a phase I study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 30, 937–346 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04107.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettler B., Kaupmann K., Mosbacher J., Gassmann M. (2004). Molecular structure and physiological functions of GABAB receptors. Physiol. Rev. 84, 835–867 10.1152/physrev.00036.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettler B., Kaupmann K., Mosbacher J., Gassmann M. (2004). Molecular structure and physiological functions of GABA(B) receptors. Physiol. Rev. 84, 835–867 10.1152/physrev.00036.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff S., Leonhard S., Reymann N., Schuler V., Shigemoto R., Kaupmann K., Bettler B. (1999). Spatial distribution of GABA(B)R1 receptor mRNA and binding sites in the rat brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 412, 1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackshaw L. A., Staunton E., Lehmann A., Dent J. (1999). Inhibition of transient LES relaxations and reflux in ferrets by GABA receptor agonists. Am. J. Physiol. 277, G867–G874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blandizzi C., Bernardini M. C., Natale G., Martinotti E., Del Tacca M. (1992). Peripheral 2-hydroxy-saclofen-sensitive GABAB receptors mediate both vagal-dependent and vagal-independent acid secretory responses in rats. J. Auton. Pharmacol. 12, 149–156 10.1111/j.1474-8673.1992.tb00372.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blein S., Hawrot E., Barlow P. (2000). The metabotropic GABA receptor: molecular insights and their functional consequences. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 57, 635–650 10.1007/PL00000725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeckxstaens G. E, Rydholm H, Lei A., Adler J., Ruth M. (2010a). Effect of lesogaberan, a novel GABA(B)-receptor agonist, on transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxations in male subjects. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 31, 1208–1217 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04283.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeckxstaens G. E., Beaumont H., Mertens V., Denison H., Ruth M., Adler J., Silberg D. G., Sifrim D. (2010b). Effect of lesogaberan on reflux and lower esophageal sphincter function in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 139, 409–417 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bormann J. (2000). The ‘ABC’ of GABA receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 21, 16–19 10.1016/S0165-6147(99)01413-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowery N. G., Bettler B., Froestl W., Gallagher J. P., Marshall F., Raiteri M., Bonner T. I., Enna S. J. (2002). International union of pharmacology. XXXIII. Mammalian gamma-aminobutyric acid(B) receptors: structure and function. Pharmacol. Rev. 54, 247–264 10.1124/pr.54.2.247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusberg M., Ravnefjord A., Martinsson R., Larsson H., Martinez V., Lindstrom E. (2009). The GABAB receptor agonist, baclofen, and the positive allosteric modulator, CGP7930, inhibit visceral pain-related responses to colorectal distension in rats. Neuropharmacology 56, 362–367 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calver A. R., Davies C. H., Pangalos M. (2002). GABAB receptors: from monogamy to promiscuity. Neurosignals 11, 299–314 10.1159/000068257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calver A. R., Medhurst A. D., Robbins M. J., Charles K. J., Evans M. L., Harrison D. C., Stammers M., Hughes S. A., Hervieu G., Couve A., Moss S. J., Middlemiss D. N., Pangalos M. N. (2000). The expression of GABAB1 and GABAB2 receptor subunits in the cNS differs from that in peripheral tissues. Neuroscience 100, 155–170 10.1016/S0306-4522(00)00262-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova E., Guetg N., Vigot R., Seddik R., Julio-Pieper M., Hyland N. P., Cryan J. F., Gassmann M., Bettler B. (2009). A mouse model for visualization of GABAB receptors. Genesis 47, 595–602 10.1002/dvg.20535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelli M. P., Ingianni A., Stefanini E., Gessa G. L. (1999). Distribution of GABAB receptor mRNAs in the rat brain and peripheral organs. Life Sci. 64, 1321–1328 10.1016/S0024-3205(99)00067-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccaglione A. F., Marzio L. (2003). Effect of acute and chronic administration of the GABAB agonist baclofen on 24 hour pH metry and symptoms in control subjects and in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gut 52, 464–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark J. A., Mezey E., Lam A. S., Bonner T. I. (2000). Distribution of the GABAB receptor subunit gb2 in rat CNS. Brain Res. 860, 41–52 10.1016/S0006-8993(00)01958-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collares E. F., Vinagre A. M. (2005). Effect of the GABAB agonist baclofen on dipyrone-induced delayed gastric emptying in rats. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 38, 99–104 10.1590/S0100-879X2005000100015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryan J. F., Kaupmann K. (2005). Don't worry ‘B’ happy!: a role for GABAB receptors in anxiety and depression. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 26, 36–43 10.1016/j.tips.2004.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engle M. P., Gassman M., Sykes K. T., Bettler B., Hammond D. L. (2006). Spinal nerve ligation does not alter the expression or function of GABA(B) receptors in spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia of the rat. Neuroscience 138, 1277–1287 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.11.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fargeas M. J., Fioramonti J., Bueno L. (1988). Central and peripheral action of GABAA and GABAB agonists on small intestine motility in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 150, 163–169 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90763-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher E. L., Clark M. J., Furness J. B. (2002). Neuronal and glial localization of GABA transporter immunoreactivity in the myenteric plexus. Cell Tissue Res. 308, 339–346 10.1007/s00441-002-0566-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy J. M., Meskenaite V., Weinmann O., Honer M., Benke D., Mohler H. (1999). GABAB-receptor splice variants GB1a and GB1b in rat brain: developmental regulation, cellular distribution and extrasynaptic localization. Eur. J. Neurosci. 11, 761–768 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00481.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassmann M., Shaban H., Vigot R., Sansig G., Haller C., Barbieri S., Humeau Y., Schuler V., Muller M., Kinzel B., Klebs K., Schmutz M., Froestl W., Heid J., Kelly P. H., Gentry C., Jaton A. L., van der P. H., Mombereau C., Lecourtier L., Mosbacher J., Cryan J. F., Fritschy J. M., Luthi A., Kaupmann K., Bettler B. (2004). Redistribution of GABAB1 protein and atypical GABAB responses in GABAB2-deficient mice. J. Neurosci. 24, 6086–6097 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5635-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentilini G., Franchi-Micheli S., Pantalone D., Cortesini C., Zilletti L. (1992). GABAB receptor-mediated mechanisms in human intestine in vitro. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 217, 9–14 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90504-W [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerson L. B., Huff F. J., Hila A., Hirota W. K., Reilley S., Agrawal A., Lal R., Luo W., Castell D. (2010). Arbaclofen placarbil decreases postprandial reflux in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 105, 1266–1275 10.1038/ajg.2009.718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giotti A., Luzzi S., Maggi C. A., Spagnesi S., Zilletti L. (1985). Modulatory activity of GABAB receptors on cholinergic tone in guinea-pig distal colon. Br. J. Pharmacol. 84, 883–895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giotti A., Luzzi S., Spagnesi S., Zilletti L. (1983). GABAA and GABAB receptor-mediated effects in guinea-pig ileum. Br. J. Pharmacol. 78, 469–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto Y., Debas H. T. (1983). GABA-mimetic effect on gastric acid secretion. Possible significance in central mechanisms. Dig. Dis. Sci. 28, 56–59 10.1007/BF01393361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grider J. R., Makhlouf G. M. (1992). Enteric GABA: mode of action and role in the regulation of the peristaltic reflex. Am. J. Physiol. 262, G690–G694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara K., Saito Y., Kirihara Y., Sakura S. (2004). The interaction between gamma-aminobutyric acid agonists and diltiazem in visceral antinociception in rats. Anesth. Analg. 98, 1380–1384 10.1213/01.ANE.0000107935.84035.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara K., Saito Y., Kirihara Y., Yamada Y., Sakura S., Kosaka Y. (1999). The interaction of antinociceptive effects of morphine and GABA receptor agonists within the rat spinal cord. Anesth. Analg. 89, 422–427 10.1097/00000539-199908000-00032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara N., Hara Y., Goto Y. (1990). Effects of GABA antagonists and structural GABA analogues on baclofen stimulated gastric acid secretion in the rat. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 52, 345–352 10.1254/jjp.52.345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardcastle J., Hardcastle P. T., Mathias W. J. (1991). The influence of the gamma-amino butyric acid (GABA) antagonist bicuculline on transport processes in rat small intestine. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 43, 128–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebeiss K., Kilbinger H. (1999). Cholinergic and GABAergic regulation of nitric oxide synthesis in the guinea pig ileum. Am. J. Physiol. 276, G862–G866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson L. H., Bettler B., Kaupmann K., Cryan J. F. (2006). GABAB1 receptor subunit isoforms exert a differential influence on baseline but not GABAB receptor agonist-induced changes in mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 319, 1317–1326 10.1124/jpet.106.111971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson L. H., Bettler B., Kaupmann K., Cryan J. F. (2007). Behavioral evaluation of mice deficient in GABA(B(1)) receptor isoforms in tests of unconditioned anxiety. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 190, 541–553 10.1007/s00213-006-0631-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaupmann K., Huggel K., Heid J., Flor P. J., Bischoff S., Mickel S. J., McMaster G., Angst C., Bittiger H., Froestl W., Bettler B. (1997). Expression cloning of GABAB receptors uncovers similarity to metabotropic glutamate receptors. Nature 386, 239–246 10.1038/386239a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami S., Uezono Y., Makimoto N., Enjoji A., Kaibara M., Kanematsu T., Taniyama K. (2004). Characterization of GABAB receptors involved in inhibition of motility associated with acetylcholine release in the dog small intestine: possible existence of a heterodimer of GABAB1 and GABAB2 subunits. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 94, 368–375 10.1254/jphs.94.368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbinger H., Ginap T., Erbelding D. (1999). GABAergic inhibition of nitric oxide-mediated relaxation of guinea-pig ileum. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 359, 500–504 10.1007/PL00005382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krantis A. (2000). GABA in the mammalian enteric nervous system. News Physiol. Sci. 15, 284–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krantis A., Harding R. K. (1987). GABA-related actions in isolated in vitro preparations of the rat small intestine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 141, 291–298 10.1016/0014-2999(87)90274-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann A. (2009). GABAB receptors as drug targets to treat gastroesophageal reflux disease. Pharmacol. Ther. 122, 239–245 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann A., Antonsson M., Aurell Holmberg A., Blackshaw L. A., Brändén L., Bräuner-Osborne H., Christiansen B., Dent J., Elebring T., Jacobson B.-M., Jensen J., Mattsson J. P., Nilsson K., Oja Page A. J., Saransaari P., von Unge S. (2009). Peripheral GABAB receptor agonism as a potential therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 331, 504–512 10.1124/jpet.109.153593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann A., Antonsson M., Bremner-Danielsen M., Flardh M., Hansson-Branden L., Karrberg L. (1999). Activation of the GABAB receptor inhibits transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations in dogs. Gastroenterology 117, 1147–1154 10.1016/S0016-5085(99)70400-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann A., Elebring T., Jensen J., Mattsson J. P., Nilsson K. A., Saransaari P., von Unge S. (2008). In vivo and in vitro characterization of AZD9343, a novel GABAB receptor agonist and reflux inhibitor. Gastroenterology 134, A131– A132 10.1016/S0016-5085(08)60611-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann A., Jensen J. M., Boeckxstaens G. E. (2010). GABAB receptor agonism as a novel therapeutic modality in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Adv. Pharmacol. 58, 287–313 10.1016/S1054-3589(10)58012-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidums I., Lehmann A., Checklin H., Dent J., Holloway R. H. (2000). Control of transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations and reflux by the GABAB agonist baclofen in normal subjects. Gastroenterology 118, 7–13 10.1016/S0016-5085(00)70408-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Westlund K. N. (2001). Effects of baclofen on colon inflammation-induced Fos, CGRP and SP expression in spinal cord and brainstem. Brain Res. 889, 118–130 10.1016/S0006-8993(00)03124-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luscher C., Jan L. Y., Stoffel M., Malenka R. C., Nicoll R. A. (1997). G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying K channels (GIRKs) mediate postsynaptic but not presynaptic transmitter actions in hippocampal neurons. Neuron 19, 687–695 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80381-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNaughton W. K., Pineau B. C., Krantis A. (1996). Gamma-Aminobutyric acid stimulates electrolyte transport in the guinea pig ileum in vitro. Gastroenterology 110, 498–507 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8566597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malherbe P., Masciadri R., Norcross R. D., Knoflach F., Kratzeisen C., Zenner M. T., Kolb Y., Marcuz A., Huwyler J., Nakagawa T., Porter R. H., Thomas A. W., Wettstein J. G., Sleight A. J., Spooren W., Prinssen E. P. (2008). Characterization of (R,S)-5,7-di-tert-butyl-3-hydroxy-3-trifluoromethyl-3H-benzofuran-2-one as a positive allosteric modulator of GABAB receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 154, 797–811 10.1038/bjp.2008.135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcoli M., Scarrone S., Maura G., Bonanno G., Raiteri M. (2000). A subtype of the gamma-aminobutyric acid (B) receptor regulates cholinergic twitch response in the guinea pig ileum. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 293, 42–47 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin S. C., Russek S. J., Farb D. H. (2001). Human GABABR genomic structure: evidence for splice variants in GABABR1 but not GABABR2. Gene 278, 63–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott C. M., Abrahams T. P., Partosoedarso E., Hyland N., Ekstrand J., Monroe M., Hornby P. J. (2001). Site of action of GABAB receptor for vagal motor control of the lower esophageal sphincter in ferrets and rats. Gastroenterology 120, 1749–1762 10.1053/gast.2001.24849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minervini F., Bilancia M. T., Siragusa S., Gobbetti M., Caponio F. (2009). Fermented goats’ milk produced with selected multiple starters as a potentially functional food. Food Microbiol. 26, 559–564 10.1016/j.fm.2009.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minocha A., Galligan J. J. (1993). Excitatory and inhibitory responses mediated by GABAA and GABAB receptors in guinea pig distal colon. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 230, 187–193 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90801-N [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mombereau C., Kaupmann K., Froestl W., Sansig G., van der Putten H., Cryan J. F. (2004). Genetic and pharmacological evidence of a role for GABAB receptors in the modulation of anxiety- and antidepressant-like behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology 29, 1050–1062 10.1038/sj.npp.1300413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mombereau C., Kaupmann K., Gassmann M., Bettler B., van der Putten H., Cryan J. F. (2005). Altered anxiety and depression-related behaviour in mice lacking GABAB2 receptor subunits. Neuroreport 16, 307–310 10.1097/00001756-200502280-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima K., Tooyama I., Kuriyama K., Kimura H. (1996). Immunohistochemical demonstration of GABAB receptors in the rat gastrointestinal tract. Neurochem. Res. 21, 211–215 10.1007/BF02529137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayasu H., Nishikawa M., Mizutani H., Kimura H., Kuriyama K. (1993). Immunoaffinity purification and characterization of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)B receptor from bovine cerebral cortex. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 8658–8664 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong J., Kerr D. I. (1982). GABAA- and GABAB-receptor-mediated modification of intestinal motility. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 86, 9–17 10.1016/0014-2999(82)90390-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong J., Kerr D. I. (1987). Comparison of GABA-induced responses in various segments of the guinea-pig intestine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 134, 349–353 10.1016/0014-2999(87)90368-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page A. J., Blackshaw L. A. (1999). GABAB receptors inhibit mechanosensitivity of primary afferent endings. J. Neurosci. 19, 8597–8602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page A. J., O'Donnell T. A., Blackshaw L. A. (2006). Inhibition of mechanosensitivity in visceral primary afferents by GABAB receptors involves calcium and potassium channels. Neuroscience 137, 627–636 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park K. B., Ji G. E., Park M. S., Oh S. H. (2005). Expression of rice glutamate decarboxylase in Bifidobacterium longum enhances gamma-aminobutyric acid production. Biotechnol. Lett. 27, 1681–1684 10.1007/s10529-005-2730-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pencheva N., Itzev D., Milanov P. (1999). Comparison of gamma-aminobutyric acid effects in different parts of the cat ileum. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 368, 49–56 10.1016/S0014-2999(99)00017-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piqueras L., Martinez V. (2004). Peripheral GABAB agonists stimulate gastric acid secretion in mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 142, 1038–1048 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosser H. M., Gill C. H., Hirst W. D., Grau E., Robbins M., Calver A., Soffin E. M., Farmer C. E., Lanneau C., Gray J., Schenck E., Warmerdam B. S., Clapham C., Reavill C., Rogers D. C., Stean T., Upton N., Humphreys K., Randall A., Geppert M., Davies C. H., Pangalos M. N. (2001). Epileptogenesis and enhanced prepulse inhibition in GABAB1-deficient mice. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 17, 1059–1070 10.1006/mcne.2001.0995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts D. J., Hasler W. L., Owyang C. (1993). GABA mediation of the dual effects of somatostatin on guinea pig ileal myenteric cholinergic transmission. Am. J. Physiol. 264, G953–G960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotondo A., Serio R., Mule F. (2010). Functional evidence for different roles of GABAA and GABAB receptors in modulating mouse gastric tone. Neuropharmacology 58, 1033–1037 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger G. J., Munonyara M. L., Dass N., Prosser H., Pangalos M. N., Parsons M. E. (2002). GABAB receptor function in the ileum and urinary bladder of wildtype and GABAB1 subunit null mice. Auton. Autacoid Pharmacol. 22, 147–154 10.1046/j.1474-8673.2002.00254.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler V., Luscher C., Blanchet C., Klix N., Sansig G., Klebs K., Schmutz M., Heid J., Gentry C., Urban L., Fox A., Spooren W., Jaton A. L., Vigouret J., Pozza M., Kelly P. H., Mosbacher J., Froestl W., Kaslin E., Korn R., Bischoff S., Kaupmann K., van der P. H., Bettler B. (2001). Epilepsy, hyperalgesia, impaired memory, and loss of pre- and postsynaptic GABAB responses in mice lacking GABAB1. Neuron 31, 47–58 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00345-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schworer H., Racke K., Kilbinger H. (1989). GABA receptors are involved in the modulation of the release of 5-hydroxytryptamine from the vascularly perfused small intestine of the guinea-pig. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 165, 29–37 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90767-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta J. N., Medda B. K., Shaker R. (2002). Effect of GABAB receptor agonist on distension-sensitive pelvic nerve afferent fibers innervating rat colon. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 283, G1343–G1351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symonds E., Butler R., Omari T. (2003). The effect of the GABAB receptor agonist baclofen on liquid and solid gastric emptying in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 470, 95–97 10.1016/S0014-2999(03)01779-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsuta M., Iishi H., Baba M., Nakaizumi A., Ichii M., Taniguchi H. (1990). Inhibition by gamma-amino-n-butyric acid and baclofen of gastric carcinogenesis induced by N-methyl-N’-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine in Wistar rats. Cancer Res. 50, 4931–4934 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsuta M., Iishi H., Baba M., Taniguchi H. (1992). Attenuation by the GABA receptor agonist baclofen of experimental carcinogenesis in rat colon by azoxymethane. Oncology 49, 241–245 10.1159/000227048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonini M., Crema A., Frigo G. M., Rizzi C. A., Manzo L., Candura S. M., Onori L. (1989). An in vitro study of the relationship between GABA receptor function and propulsive motility in the distal colon of the rabbit. Br. J. Pharmacol. 98, 1109–1118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torashima Y., Uezono Y., Kanaide M., Ando Y., Enjoji A., Kanematsu T., Taniyama K. (2009). Presence of GABAB receptors forming heterodimers with GABAB1 and GABAB2 subunits in human lower esophageal sphincter. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 111, 253–259 10.1254/jphs.09062FP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urwyler S., Mosbacher J., Lingenhoehl K., Heid J., Hofstetter K., Froestl W., Bettler B., Kaupmann K. (2001). Positive allosteric modulation of native and recombinant gamma-aminobutyric acid (B) receptors by 2,6-Di-tert-butyl-4-(3-hydroxy-2,2-dimethyl-propyl)-phenol (CGP7930) and its aldehyde analog CGP13501. Mol. Pharmacol. 60, 963–971 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urwyler S., Pozza M. F., Lingenhoehl K., Mosbacher J., Lampert C., Froestl W., Koller M., Kaupmann K. (2003). N,N’-Dicyclopentyl-2-methylsulfanyl-5-nitro-pyrimidine-4, 6-diamine (GS39783) and structurally related compounds: novel allosteric enhancers of gamma-aminobutyric acidB receptor function. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 307, 322–330 10.1124/jpet.103.053074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Herwaarden M. A., Samsom M., Rydholm H., Smout A. J. (2002). The effect of baclofen on gastro-oesophageal reflux, lower oesophageal sphincter function and reflux symptoms in patients with reflux disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 16, 1655–1662 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01325.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigot R., Barbieri S., Brauner-Osborne H., Turecek R., Shigemoto R., Zhang Y. P., Lujan R., Jacobson L. H., Biermann B., Fritschy J. M., Vacher C. M., Muller M., Sansig G., Guetg N., Cryan J. F., Kaupmann K., Gassmann M., Oertner T. G., Bettler B. (2006). Differential compartmentalization and distinct functions of GABAB receptor variants. Neuron 50, 589–601 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki K., Goto Y., Hara N., Hara Y. (1991). GABAA and GABAB-receptor agonists evoked vagal nerve efferent transmission in the rat. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 55, 11–18 10.1254/jjp.55.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]