Abstract

Introduction: European countries need to learn from each other to address unsustainable increases in pharmaceutical expenditures. Objective: To assess the influence of the many supply and demand-side initiatives introduced across Europe to enhance prescribing efficiency in ambulatory care. As a result provide future guidance to countries. Methods: Cross national retrospective observational study of utilization (DDDs – defined daily doses) and expenditure (Euros and local currency) of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and statins among 19 European countries and regions principally from 2001 to 2007. Demand-side measures categorized under the “4Es” – education engineering, economics, and enforcement. Results: Instigating supply side initiatives to lower the price of generics combined with demand-side measures to enhance their prescribing is important to maximize prescribing efficiency. Just addressing one component will limit potential efficiency gains. The influence of demand-side reforms appears additive, with multiple initiatives typically having a greater influence on increasing prescribing efficiency than single measures apart from potentially “enforcement.” There are also appreciable differences in expenditure (€/1000 inhabitants/year) between countries. Countries that have not introduced multiple demand side measures to counteract commercial pressures to enhance the prescribing of generics have seen considerably higher expenditures than those that have instigated a range of measures. Conclusions: There are considerable opportunities for European countries to enhance their prescribing efficiency, with countries already learning from each other. The 4E methodology allows European countries to concisely capture the range of current demand-side measures and plan for the future knowing that initiatives can be additive to further enhance their prescribing efficiency.

Keywords: drugs, generics, economics, pharmaceuticals, efficiency, sustainability

Introduction

Scrutiny of pharmaceutical expenditures is increasing as this is the fastest growing cost component in ambulatory care, with pharmaceutical expenditures now typically the largest cost or equal largest component in this sector across Europe (Ess et al., 2003; Godman et al., 2008a; Simoens, 2008a; Coma et al., 2009; Barry et al., 2010; Sermet et al., 2010). Pharmaceutical expenditure is proportionally higher in middle and lower income countries at between 20 and 60% of total healthcare spending, although from a lower baseline (Cameron et al., 2009). The reasons for increasing expenditures are well known and include demographic changes, the continued launch of new expensive medicines, rising patient expectations and stricter clinical targets (Gumbs et al., 2007; Garattini et al., 2008; Lee and Emanuel, 2008; Barry et al., 2010). New biological drugs marketed at appreciably higher acquisition costs than previous standards provide additional impetus to this growth in expenditure enhancing the scrutiny (Caroll, 2005; Barrett et al., 2006; Lee and Emanuel, 2008).

This unsustainable growth has resulted in increasing urgency among governments, health authorities and health insurance companies to introduce reforms to improve prescribing efficiency for both new and existing drugs (Traulsen and Almarsdóttir, 2005; Toth, 2010). Supply side reforms for existing drugs include compulsory price cuts, measures to lower generic prices, reference pricing in a class (Anatomical Therapeutic Classification Level 4 – World Health Organization [WHO], 2009) including voluntary reference pricing, as well as delisting products from the reimbursement list when they are considered no longer to be cost–effective versus current standards (Godman et al., 2008a,b, 2009a,b,c, 2010a; Simoens, 2008b; Teixeira and Vieira, 2008; Wettermark et al., 2008; Coma et al., 2009; Elshaug et al., 2009; McGinn et al., 2010; Sermet et al., 2010). Demand-side reforms and initiatives for existing drugs include measures to enhance the prescribing and dispensing of generics. This includes academic detailing and prescribing guidance incorporating electronic prescribing support systems, prescribing targets, financial incentives including incentives to enhance substitution in pharmacies, mandatory substitution unless prohibited by government agencies and administrative barriers to relegate the prescribing of patent protected products in a class or related classes to second line (Tilson et al., 2005; Gumbs et al., 2007; Hyde, 2007; Sakshaug et al., 2007; Sjöborg et al., 2007; Gouya et al., 2008; Simoens, 2008b,c; Godman et al., 2009a,c, 2010b; Wettermark et al., 2009a,b, 2010a; Krska and Godman, 2010; Martikainen et al., 2010; McGinn et al., 2010; Sermet et al., 2010). A number of these strategies are aimed at counter-acting the commercial activities of pharmaceutical companies, who have typically been the principal source of information among physicians for new drugs (Jones et al., 2001; Prosser et al., 2003; Szecseny, 2003; Watkins et al., 2003; Pegler and Underhill, 2005). This together with the complex nature of prescribing helps explain why pharmaceutical companies in the UK currently invest over £850 mn/year in marketing activities, with similar experiences across Europe (Beishon et al., 2007; Godman et al., 2008b).

Alongside this, governments, health authorities and health insurance agencies have instigated a range of measures to address physician and patient concerns with the effectiveness and/or side-effects of generics to release valuable resources. This urgency has increased with estimated global sales of products of $US50 bn to $US100 bn of products likely to lose their patents between 2008 and 2013 (Frank, 2007; Jack, 2008). The initiatives are similar and include defined criteria for granting substitutability status for generics, publishing lists of substitutable and non-substitutable products, not reimbursing generics where there are concerns with their quality, physician and patient education, encouraging International non-proprietary name (INN) prescribing as well as incentivizing pharmacists to talk with patients when substituting to allay any fears (Allenet and Barry, 2003; Valles et al., 2003; Kjoenniksen et al., 2006; Kopp and Vandevelde, 2006; Godman et al., 2008a, 2009a; Teixeira and Vieira, 2008; Versantvoort et al., 2008; Duerden and Hughes, 2010; Sermet et al., 2010). These concerns though generally only apply in a limited number of situations (Valles et al., 2003; Kjoenniksen et al., 2006; Heikkilä et al., 2007; Shrank et al., 2009). As a result, there should be considerable opportunities for European countries to further enhance their prescribing efficiency without compromising care. This should be welcomed as further reforms are essential to maintain comprehensive and equitable healthcare throughout Europe as we are already seeing European countries experiencing difficulties with funding new premium priced ambulatory care drugs even when these are considered cost–effective. Current activities to help fund new innovative drugs include (Cooke et al., 2005; DoH, 2006, 2008; Godman et al., 2009a; Krska and Godman, 2010; Wettermark et al., 2010b):

placing them on “waiting lists” until more funding becomes available, e.g., Lithuania

funding a limited number through special programs, e.g., “Therapeutic Programs” in Poland

increasing planning activities to pro-actively address potential funding concerns. This includes ascertaining the potential role for new treatments ahead of launch as well as identifying potential areas to release resources, such as current treatments that well soon lose their patent, to fund new innovative treatments at launch, e.g., Sweden and UK. Subsequently monitoring prescribing of the new products against agreed guidance post launch

It is recognized it is difficult for countries to learn from each other in view of different circumstances and starting points, with one approach unlikely to fit all countries. In addition, prescribing behavior is complex (Grol and Grimshaw, 2003; Prosser et al., 2003; Prosser and Walley, 2005; Wettermark et al., 2009b). Having said this, there are examples of European countries learning from each other when considering new health reforms (Toth, 2010). In addition, the plethora of different measures introduced across Europe to enhance prescribing efficiency should stimulate debates within countries on additional reforms and initiatives that could be introduced. Coupled with this, cross national comparisons of drug utilization and expenditure also help identify possible additional reforms that countries could introduce through analytical studies linking datasets from different countries and regions and matching changes in utilization and expenditure with health policy initiatives.

The objectives of this paper are to assess the influence of the many supply and demand-side reforms and initiatives introduced across Europe to enhance prescribing efficiency in ambulatory care once a decision has been made to prescribe a particular class of drug. Subsequently utilize the findings to suggest potential future initiatives that countries could consider to further enhance their prescribing efficiency given continued resource pressures. This though acknowledging the complexities involved.

Materials and Methods

This is a cross national retrospective observational study involving the analysis of reimbursed utilization and expenditure on a yearly basis for the Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs) and HMG CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) among European countries.

Nineteen European countries and regions took part in this study. These were Austria (AT), Croatia (HR), Estonia (EE), France (FR), Finland (FI), Germany (DE), Italy (IT), Lithuania (LT), Norway (NO), Portugal (PT), Poland (PO), Republic of Ireland (IE), Serbia (RS), Slovenia (SI), Spain (ES – only Catalonia), Sweden (SE), Turkey (TR), and the United Kingdom (GB-Eng – England and GB-Scot – Scotland). The countries reflect differences in geography, epidemiology, financing of healthcare, available resources for healthcare as well as different approaches to the pricing of generics, originators, and single sourced products (Table 1). They also reflect appreciable differences in the nature and extent of reforms and initiatives introduced to enhance the prescribing of generics. As a result, provide a number of exemplar initiatives and countries (Table A1 of Appendix).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the European countries in 2008 (using published definitions for generic pricing).

| AT | DE | EE | ES | FI | FR | GB – Eng | GB – Scot | HR | IE | IT | LT | NO | PO | PT | RS | SE | SI | TR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financing – taxation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Financing – health insurance | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Generics – PP | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Generics – MF | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Generics – MA | ✓ | ✓ | AC | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Reference pricing – class(ATC Level 3 or 4) | VP | ✓ | NI | NI | AC | NI | RJT | RJT | ✓ | NI | ✓ | AC | NI | ✓ | NI | Part | Only PPIs | NI | ✓ |

Generic pricing: AC, actively considering. Reference pricing: VP, voluntary reference pricing; NI, not introduced; RJT, proposed but rejected; AC, active consideration; Part, partial applying to some product classes but not all.

The following definitions have been used to classify the different pricing approaches for generics across Europe, which build on previous publications (Godman et al., 2010a,c):

Prescriptive pricing (PP) – mandated price reductions for generics for reimbursement compared with for instance pre-patent loss prices for the molecule

Market forces (MF) – no prescriptive pricing approaches; price reductions left to market forces with typically patients paying an additional co-payment for a more expensive product including branded generics than the current referenced priced molecule

Mixed approaches (MA) – typically prescriptive pricing for the first generic or generics; market forces after that

We acknowledge though that in some countries only branded generics are available. However, to reduce confusion only the term “generics” will be used throughout the paper.

Only administrative databases were used to ensure standardization across countries. These included (100% coverage of the population unless stated):

AT (Austria) – Data Warehouse of the Federation of Austrian Social Insurance Institutions (98% of the population)

DE (Germany) – GAMSI-Database, i.e., the GKV Arzneimittel Schnell-Information, which covers all prescriptions paid by the Social Health Insurance Funds (SHI – approximately 90% of the population)

EE (Estonia) – Estonian Health Insurance Fund

ES (Spain – only Catalonia) – DMART (Catalan Health Service) database (all patients in Catalonia). Data only available from 2003 onwards

FI (Finland) – Prescription Register of the Social Insurance Institution

FR (France) – Medic'am database (CNAM-TS database for salaried personnel covering 75% of the population)

GB – Eng (England) – Information Centre for Health and Social Care

GB – Scot (Scotland) – Prescribing Information System (PIS) from NHS National Services Scotland Corporate Warehouse

HR (Croatia) – Croatian Institute for Health Insurance

IE (Republic of Ireland) – HSE-PCRS (GMS Population covering approximately 30% of the population with higher morbidity than the general population reflected in consuming approximately 65% of total pharmaceutical expenditure)

IT (Italy) – OsMed database

LT (Lithuania) – Electronic database of the National Health Insurance Fund

NO (Norway) – Norwegian Prescription Database (NorPD). Expenditure data only available from 2004 onwards

PO (Poland) – National Health Fund database

PT (Portugal) – INFARMED (NHS) database (approximately 75% of the population)

RS (Serbia) – Republic of Serbia's Health Insurance Fund database

SE (Sweden) – Apoteket AB (National Corporation of Swedish Pharmacies – monopoly up to 1 January 2010)

SI (Slovenia) – The National Institute of Public Health and Health Insurance Institute Prescription Database

TR (Turkey) – Social Security Institution (SGK) – single national public payer purchasing approximately 95% of pharmaceutical expenditure in Turkey

As discussed, two classes were chosen for in-depth analysis of ambulatory care prescribing efficiency. These were the PPIs – Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) A02BC, and the HMG CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) – ATC group C10AA (WHO, 2009). These two classes were chosen as (AFSSAPS, 2005; MeReC Extra, 2006; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2006; Wessling and Lundin, 2006; Godman et al., 2008b, 2009a,b; Eriksson and Lundin, 2009; Martikainen et al., 2010; McGinn et al., 2010):

they are both commonly prescribed in ambulatory care

they also contain a mixture of generics, originators and single sourced products in a class and many patients, if not all in the case of PPIs, can be adequately managed with generic products

PPIs and statins are typically the subject of country and/or regional initiatives to enhance prescribing efficiency

Utilization rates for the different molecules in each class were computed using Defined Daily Doses (DDDs), with utilization patterns in 2007 generally compared with 2001. These dates were chosen as typically both generic simvastatin and generic omeprazole became available and were reimbursed during this time period among Western European countries (Table 2). Simvastatin was the first major statin to become available as a generic in Europe with generally no or limited utilization of lovastatin. Omeprazole was the first PPI to become available as a generic. Both events resulted in demand-side initiatives to try and enhance the prescribing of generics ahead of more expensive patent protected products to improve prescribing efficiency (Table A1 of Appendix).

Table 2.

Dates when generic omeprazole and generic simvastatin were first dispensed and reimbursed among European countries.

| Country | Year when generic omeprazole was dispensed and reimbursed |

Year when generic simvastatin was dispensed and reimbursed |

Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| AT (Austria) | 2003 | 2002 | |

| DE (Germany) | 2002 | 2003 | |

| EE (Estonia) | Before 2001 | 2001 | Reimbursement data only available from 2004 |

| ES (Spain – Catalonia) | Before 2003 | Before 2003 | Data only available after 2003 |

| FI (Finland) | 2002 | Before 2001 | Data only from 2001 to 2007 |

| FR (France) | 2004 | 2005 | |

| GB – Eng (England) | 2002 | 2003 | |

| GB – Scot (Scotland) | 2002 | 2003 | |

| HR (Croatia) | Before 2000 | 2001 | Data will include 2000 to 2007 |

| IE (Republic of Ireland) | 2002 | 2003 | |

| IT (Italy) | 2007 | 2007 | 2008 compared with 2006 as both generic omeprazole and generic simvastatin became available in 2007 |

| LT (Lithuania) | Before 2001 | Before 2001 | |

| NO (Norway) | Before 2004 | Before 2004 | Pharmacy reimbursement data only available from 2004 |

| PO (Poland) | Before 2001 | Before 2001 | |

| PT (Portugal) | Before 2001 | 2001 | |

| RS (Serbia) | Before 2005 | Before 2005 | Data only available from 2005 onwards |

| SE (Sweden) | 2003 | 2003 | |

| SI (Slovenia) | Before 2001 | Before 2001 | |

| TR (Turkey) | Before 2007 | Before 2007 | Data only available from 2007 to 2009 |

The concepts of ATC classification and DDDs were developed to facilitate cross country comparisons in drug utilization especially where there are differences in pack sizes and available tablet strengths (Bergman et al., 1979; Rønning et al., 2000; Rønning, 2002). DDDs are now internationally accepted for comparing drug utilization patterns across countries (Birkett, 2002; WHO, 2003; Walley et al., 2004a; Vlahović-Palcevski et al., 2010). The ATC index from 2010 was used in this study in line with WHO recommendations (Rønning et al., 2000).

Demand-side measures, i.e., initiatives and reforms to influence subsequent prescribing or dispensing of generics, have been collated under the “4 Es,” i.e., education, engineering, economics and enforcement. This approach has been used in other settings and successfully adapted to healthcare to provide a concise and easily understandable methodology to compare and contrast the complexity and multiplicity of demand-side measures implemented within and between countries (Coma et al., 2009; Godman et al., 2009a,c; Wettermark et al., 2009b; McGinn et al., 2010). Examples of the “4 Es” include:

Educational activities – includes development and distribution of prescribing guidance right through to more intensive strategies such as educational outreach visits and benchmarking of physician prescribing habits

Engineering activities – gincludes organizational or managerial interventions such as prescribing targets and compulsory INN prescribing as well as price: volume agreements for single sourced existing products

Economic interventions – includes devolved budgets with penalties, positive and negative financial incentives, as well as differential patient co-payments for more expensive products than the current reference molecule

Enforcement – includes regulations by law such as mandatory generic substitution and prescribing restrictions

Reimbursed expenditures from 2001 to 2007 were typically captured for each class to assess the influence of recent reforms on overall expenditure from a health authority or health insurance perspective. The only exceptions were Austria, Germany and Norway where there are difficulties with disassociating co-payments from total expenditure. However, this typically represents only a small proportion of overall expenditure in these three countries. Expenditure data was collected in local currency.

Reimbursed expenditures, as opposed to total expenditures, were chosen for the analysis as this is the actual expenditure incurred by health authorities or health insurance agencies reflecting the focus of the paper. Reimbursed expenditures in 2007 was subsequently converted to /1000 inhabitants/year to compare expenditures across countries adjusted for population sizes. This includes currency conversions where pertinent to standardize the approach. This was based on established rates for the country; alternatively an average for the year from national banks (Godman and Wettermark, 2009a,b). 2007 was chosen for this calculation as this was the latest year for comprehensive data from all countries. Again, expenditure/1000 inhabitants/year is the internationally accepted standard approach for comparing expenditures across countries. Exchange rates used were 1 = 0.734GB£, LTL3.453, 8.219NOK, 3.783PLN, 79.24RSD and 9.25SEK (2007).

There has been no allowance for inflation in the analysis in order to directly compare the impact of different policies over time. In addition, health authorities and health insurance agencies typically refer to pre-patent loss prices when establishing reimbursed prices for generics especially for prescriptive pricing or mixed approaches to the pricing of generics (Godman et al., 2010a,c). It is acknowledged though that savings will be greater if inflation is factored in.

The data sets collected to compare prescribing efficiency for the PPIs and statins among the European countries included:

Total DDDs 2001 and 2007

DDDs/1000 inhabitants/day (DDDs/TID)

Reimbursed expenditure in 2001 and 2007

€/1000 inhabitants/year in 2007

Principal reforms to lower the price of generics

Principal demand-side reforms to enhance the prescribing of generic PPIs and statins compared with single sourced products collated under the 4Es

Two principal analyses were undertaken for both the PPIs and statins to assess overall efficiency, with criteria subsequently broken down into three categories. These are summarized in Table 3. The three cut-off points for assessing efficiency were chosen intuitively; however, tested among the co-authors for internal validity.

Table 3.

Principal measures used to evaluate changes in prescribing efficiency for both the PPIs and statins during the study years as well as categorize countries.

| Objective | Measure | Efficiency criteria/comment |

|---|---|---|

| Assessment of overall prescribing efficiency |

The increase in utilization rates versus the increase in reimbursed expenditure over time* |

Three efficiency criteria No efficiency – rate of increase in expenditure exceeds utilization Efficient countries – rate of increase in utilization more than double the rate of increase in expenditure Considerable efficiency – reimbursed expenditure decreasing over time despite increasing utilization. In the case of statins this also includes considerably increased utilization (over 350% during the study period) with only a limited increase in expenditure (20% or less) |

| Extent of potential savings from increasing prescribing efficiency |

Overall utilization in 2007 (DDD/TID) compared with overall expenditure (€/1000 inhabitants/year), with both measures adjusted for population sizes |

Data treated with caution as different co-payment levels for the PPIs and statins (Table A1 of Appendix) in addition to any co-payment for the package |

*Generic PPIs and statins were often available in Central and Eastern European countries before 2001 distorting the figures in reality. The Republic of Ireland will not be included when assessing potential savings (Figures 3 and 4) as the GMS population has greater morbidity than the general population reflected in appreciably higher utilization of pharmaceuticals.

In view of the limited number of peer-reviewed publications documenting current reforms for the pricing of generics, as well as current demand-side reforms and their impact especially for the PPIs and statins among the 19 European countries and regions outside of those from a number of the co-authors, details of these were typically provided by the co-authors. This method was also chosen to add robustness and standardization to the documentation since many of the co-authors are involved with either implementing or suggesting additional reforms in their country or region. This especially as there have been concerns with the accuracy of some of the health policy information contained within some of the web based publications (Blaszczyk et al., 2007).

No attempt has been made to analyze the appropriateness of prescribing of either the PPIs or statins. This is due to a lack of access to patient databases to determine the indication and/or doses prescribed. In addition, the main emphasis of this paper is regarding prescribing efficiency once a decision has been made by the physician to prescribe either a PPI or statin. These issues though have been discussed in individual country publications (Coma et al., 2009; Godman et al., 2009a,b,c; McGinn et al., 2010).

No impact analyses have been undertaken as typically multiple supply and demand-side initiatives were instigated in each country during the study period and the datasets generally covered the whole population. In addition, the intensity of different initiatives may vary over time and between different regions further hindering the usefulness of such analyses. This is reflected in the discussion. No regression lines have been added to Figures 3 and 4 as each point represents a different country subject to different supply and demand-side reforms (Table A1 of Appendix).

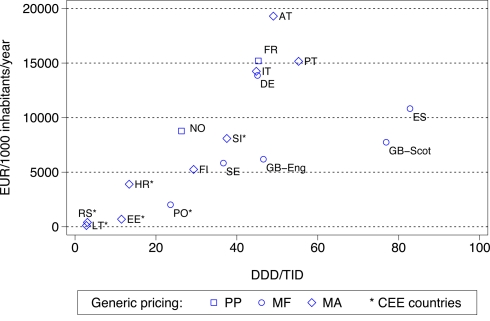

Figure 3.

Utilization (DDD/TID) and overall expenditure (€/1000 inhabitants/year) for PPIs among European countries in 2007 (Italy 2008, Serbia 2008). Standard EU country abbreviations have been used. ES = Catalonia. Republic of Ireland not included as the GMS population has greater morbidity than the general population.

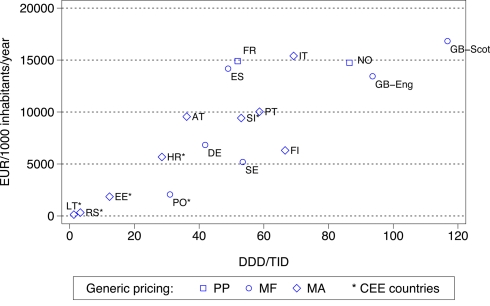

Figure 4.

Utilization (DDD/TID) and overall expenditure (€/1000 inhabitants/year) for the statins among European countries in 2007 (Italy 2008, Serbia 2008). Standard EU country abbreviations have been used. ES = Catalonia. Republic of Ireland not included as the GMS population has greater morbidity than the general population.

Results

Table A1 in the appendix documents the main pricing reforms for generics during the study period among the 19 European countries and regions. Table A1 also documents the nature and intensity of the demand-side reforms introduced to enhance prescribing efficiency principally for the PPIs and statins collated under the “4 Es.” Any co-payments for the product and/or indication, in addition to the standard co-payment for the package, are also included in Table A1. This recognizes that some European countries use this “economic” approach to influence utilization.

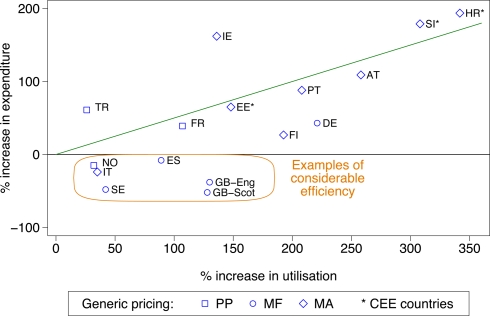

Figure 1 demonstrated the influence of the various supply and demand-side measures (Table A1 of Appendix) on PPI prescribing efficiency among the different European countries and regions as measured by the rate of change in utilization (DDDs) versus reimbursed expenditure principally between 2001 and 2007. The countries have been broken down by:

Figure 1.

Rate of increase in expenditure (local currency) versus the rate of increase in utilization (DDD based) for the PPIs principally from 2007 versus 2001 among European countries (unless stated), with generic pricing approaches divided into three categories. Standard EU country abbreviations have been used. ES = Catalonia (2007 versus 2003), EE = 2007 versus 2004, HR = 2007 versus 2000, IT = 2008 versus 2006, NO = 2007 versus 2004, TR = 2009 versus 2007.

geography – into Central and Eastern European countries and the remainder, for the reasons discussed in Table 3

the different approaches to pricing of generics – Prescriptive – PP, Market Forces – MF, Mixed – MA

Those showing considerable efficiency, in addition to general efficiency, i.e., below the line drawn, are highlighted using the definitions in Table 3.

In both Lithuania and Poland, there was approximately a twofold difference in the rate of increase in utilization (DDD basis) versus the rate of increase in reimbursed expenditure for the PPIs between 2001 and 2007, e.g., in Lithuania utilization increased 10.8-fold between 2001 and 2007 and Poland over 150-fold between 2002 and 2007. This appreciable increase in utilization following reimbursement, which was considerably greater than seen in the other European countries, led to their exclusion from Figure 1. Serbia was also excluded from Figure 1 with comprehensive data only recently becoming available, and after the availability of generic PPIs.

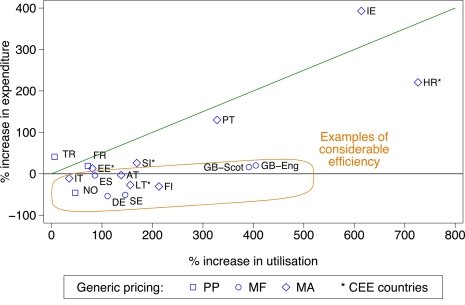

The various demand and supply side reforms instigated among the European countries and regions similarly influenced prescribing efficiency for the statins (Figure 2). The same categorization for efficiency has been used (Table 3), and again countries have been broken down into geography and approaches to the prescribing of generics.

Figure 2.

Percentage change in utilization (DDDs) versus the percentage change in reimbursed expenditure (local currency) for the statins principally from 2001 to 2007 among European countries. The countries again divided into former Central and Eastern European countries (CEE) with the approaches to generic pricing divided into three categories. Standard EU country abbreviations have been used. ES = Catalonia (2007 versus 2003), EE = 2007 versus 2004, HR = 2007 versus 2000, IT = 2008 versus 2006, NO = 2007 versus 2004, TR = 2009 versus 2007.

In Poland, there was over a 140-fold increase in statin utilization between 2002 and 2007 following their reimbursement, with overall a 4.5-fold difference between the rate of increase in utilization versus the rate of increase in reimbursed expenditure between 2001 and 2007. This efficiency gain was helped by the instigation of reference pricing for the statins. Again, Serbia was excluded from Figure 2 with comprehensive data only recently becoming available.

The differences seen in prescribing efficiency for the PPIs (Figure 1) translate into considerable differences in overall expenditure adjusted for the differences in population sizes, i.e., expenditure expressed in /1000 inhabitants/year and utilization by DDDs/1000 inhabitants/day (DDD/TID) by 2007 (Figure 3). The differences in geography and approaches to the prescribing of generics have again been highlighted. Expenditure figures for the PPIs will be affected by whether there are high patient co-payment levels (Table A1 of Appendix).

The differences seen in the rates of prescribing efficiency for the statins between 2001 and 2007 among European countries (Figure 2) are again reflected in considerable differences in overall expenditure in 2007 adjusted for population sizes (Figure 4). The differences in geography and approaches to the prescribing of generics have again been highlighted, with overall expenditures again affected by whether there are high co-payment levels for the statins (Table A1 of Appendix).

Discussion

Additional reforms are essential across Europe to continue funding increased volumes and new drugs without prohibitive increases in either taxes or health insurance premiums. As such, we consider the findings from this study help provide future direction to health authorities and health insurance agencies as they seek to instigate additional measures. This is despite the limitations of the study design, which are discussed later.

General findings from the study include more limited utilization, and hence expenditure, of the PPIs and statins among Central and Eastern European countries compared with Western European countries (Figures 3 and 4). This is principally due to prescribing restrictions and higher patient co-payments in these countries (Table A1 of Appendix). This endorses the need to document ongoing reforms when comparing utilization rates across countries otherwise there could be concerns with the accuracy of the data provided. Table A1 of Appendix also demonstrates that the “4 Es” provides a methodology for health authorities and health insurance agencies to comprehensively categorize their current demand-side initiatives ready for comparisons.

More specific findings include the fact that both supply and demand-side reforms are essential to maximize prescribing efficiency. The findings also demonstrate that the influence of the reforms appears to be additive, with “enforcement” having appreciable influence on subsequent utilization patterns.

Prescribing efficiency in Norway for the PPIs (Figure 1) is enhanced by its aggressive prescriptive pricing policy for generics, overcoming to some extent more limited demands side measures for the PPIs compared with Sweden and the UK (Table A1 of Appendix). The various pricing policies for generics in Austria, France and Portugal also helped improve prescribing efficiency with for instance the PPIs despite limited demand-side measures in these countries for this class (Table A1 of Appendix). Overall though just concentrating on one aspect of reforms, i.e., either supply or demand-side measures but not both, will not help health authorities or health insurance agencies fully realize potential efficiency gains from the availability of generics. This is illustrated when comparing for instance prescribing efficiency for the statins in Sweden and the UK (England and Scotland) versus Germany (Figures 2 and 4). In Germany in 2007, there was very limited utilization of atorvastatin following the introduction of reference pricing for the class in 2003 at just 2% of overall statin utilization (Godman et al., 2009b) with rosuvastatin not available. This compares with 21 and 33% respectively on a DDD basis for the appreciably more expensive atorvastatin and rosuvastatin in Sweden and England in 2007 (Godman et al., 2010c). However, comparative expenditure appears similar or greater in Germany due to higher expenditure/DDD for simvastatin (Figure 4). There are also differences in prescribing efficiency between Croatia and Finland even though there are high patient co-payment levels in both countries. Prescribing efficiency has been enhanced in Finland by active reforms to lower generic prices, e.g., a 3-month's course of simvastatin during early 2006 was 17 versus 127 in 2002 before the introduction of generic substitution (Martikainen et al., 2010), as well as measures restricting the prescribing of atorvastatin and rosuvastatin (Table A1 of Appendix).

The additive nature of the demand-side measures is illustrated by greater prescribing efficiency in Catalonia (Spain), Sweden and the UK with their multiple and intensive measures based on education, engineering and economic initiatives (Table A1 of Appendix) compared with France, Portugal, the Republic of Ireland and Turkey (Figures 1 and 2) due generally to more limited demand-side measures in these countries (Table A1 of Appendix); although this is now changing in France (Sermet et al., 2010). These findings concerning the additive influence of demand-side measures endorse the results from previous studies which also showed that multiple interventions appear more successful in changing prescribing behavior than single interventions (Bero et al., 1998; Barton, 2001; Grol and Grimshaw, 2003; Prosser and Walley, 2005).

Introducing prior authorization, or other similar enforcement schemes, also enhances prescribing efficiency, e.g., statins in Austria, Germany and Norway (Figure 2), coupled with reforms to lower generic prices (Table A1 of Appendix). This compares with a more limited influence on prescribing efficiency for the PPIs in Austria with just “education” and “economic” measures in the absence of “enforcement” (Figure 1; Table A1 of Appendix). The improved efficiency seen with introducing “enforcement” measures for the statins in these three countries appears similar to the combination of extensive educational, engineering and economic initiatives for the statins in for instance England and Sweden (Figure 2; Table A1 of Appendix) along with measures to lower generic prices.

“Enforcement” can be also additive and introduced at any stage as seen in Austria where prescribing restrictions for atorvastatin built on existing educational and economic activities (Table A1 of Appendix; Godman et al., 2009c). This was also seen in Sweden where recent restrictions on Angiotensin Receptor Blockers have increased their prescribing second line building on existing educational, engineering, and economic initiatives among the counties (Wettermark et al., 2010a).

As a result of the differences in the nature and extent of demand-side initiatives across these countries, there are appreciable differences in overall prescribing efficiency between France, Ireland and Portugal when compared with Catalonia (Spain), Sweden and the UK (Figures 1 and 2), and when adjusted for population sizes (Figures 3 and 4). Reimbursed expenditure is also high in Ireland in their selected GMS population at over 60,000/1000 inhabitants/year for both the PPIs and statins.

There have been concerns that extensive demand-side measures including prescribing restrictions can alter the quality of subsequent care (Fein, 2010). However, a recent ecological study demonstrated similar surrogate outcomes in patients with hypercholesterolemia whether they were prescribed formulary drugs, i.e., generic simvastatin, or non-formulary drugs including atorvastatin (Norman et al., 2009). Recent studies conducted in the UK have also shown that patients can be successfully switched from atorvastatin to generic simvastatin without compromising care (Usher-Smith et al., 2008). Conserved resources can be re-directed to fund programs to improve compliance as well as fund increased volumes with the growing incidence of cardiovascular diseases. Compliance is a real concern in patients with chronic asymptomatic diseases (Cramer et al., 2008) rather than any minor differences in effectiveness between the statins in clinical trials, which is not seen in practice (Usher-Smith et al., 2008; Norman et al., 2009).

We are also seeing countries learning from each other as resources pressures grow. This builds on earlier examples generally within healthcare (Toth, 2010), with some examples contained in Table 4.

Table 4.

Examples of countries learning from each other (Godman et al., 2008b, 2009a; Wettermark et al., 2008, 2010a; Barry et al., 2010; Martikainen et al., 2010; McGinn et al., 2010).

| Measures | Examples |

|---|---|

| Supply side – pricing examples | Republic of Ireland introducing reference pricing for the molecule unless there are concerns such as a narrow therapeutic window Health Insurance Fund in Lithuania actively considering reference pricing for the class Republic of Serbia recently introducing policies to further lower the price of generics The Office of Fair Trading in the UK proposing reference pricing for both the molecule and the class. The latter building on the recent experiences in Sweden with proposed reference pricing for the PPIs |

| Demand-side initiatives | Regions in Spain introducing prescribing targets linked with financial incentives Prescribing restrictions introduced for atorvastatin and rosuvastatin in Finland Compulsory INN prescribing in Lithuania unless prior approval granted The national reimbursement agency in Sweden introducing prescribing restrictions for ARBs and patent protected statins to enhance prescribing efficiency compared with continuing with reference pricing (as seen with the PPIs – Table 1) as more complex disease areas than excess acid in the stomach Primary Care Trusts in the UK instigating therapeutic substitution and prior approval schemes to further enhance prescribing efficiency |

As discussed, we accept there are limitations with the study design, which are summarized in Table 5. However, some of these issues are less important when comparing changes in utilization and/or expenditure as opposed to comparing absolute numbers.

Table 5.

Limitations with the study design and rationale for some of the choices.

| Limitations |

|---|

| No control groups in each country |

| Health authorities and health insurance agencies typically instigate multiple reforms over time; consequently, difficult to single out individual demand – side measures and their influence |

| No inclusion of OTC or hospital sales, which could impact especially on the findings for the PPIs where there are high patient co-payment levels |

| Only administrative databases used and not compared with the findings from commercial sources such as Intercontinental Marketing Services (IMS) reflecting the focus of the paper. It is recognized there will be differences in utilization rates between IMS and administrative databases especially where there are high co-payments and/or appreciable restrictions on reimbursed population (seen in practice in Lithuania) |

| Prescribed daily doses (PDDs) were not used as no universal access to prescribing databases or IMS data across all countries. PDDs are likely to be a greater especially with the statins with higher doses advocated in recent guidelines (Walley et al., 2004b) |

| No universal access to patient databases also means no ability to link prescriptions with indications |

| Typically only reimbursed expenditure evaluated acknowledging total expenditure will be greater in countries with appreciable co-payments for statins and PPIs. This principally applies to France as well as Central and Eastern European countries (Table A1 of Appendix). In addition, reimbursed expenditures do not include any rebates or discounts given by generic manufacturers to community pharmacists to preferentially dispense their generic or the dispensing of parallel imported products at lower prices than current tariffs for the pack (the same though also applies to commercial databases). There are also variations in the extent of VAT added to dispensed packs across Europe. However, reimbursed expenditure was chosen to reflect the payer focus of the paper as well as provide standardization across countries |

As a result, some of the findings especially regarding expenditures need to be treated with caution.

Never-the-less, we consider the findings will be of interest to health authorities and health insurance agencies as they plan future supply and demand-side measures to further improve their prescribing efficiency. We also believe the findings will be of interest to pharmaceutical companies as they plan for the future, especially as health authorities and health insurance agencies become increasingly proactive to conserve resources for existing products (Moon et al., 2010).

Ongoing initiatives to optimize the managed entry of new drugs will be discussed in future papers particularly as they underscore the notion that the funding of new premium priced products is an important challenge in Europe (Garattini et al., 2008).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The majority of the authors are employed directly by health authorities or health insurance agencies or are advisers to these organizations. No author has any other relevant affiliation or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript, although Morten Andersen has received teaching grants from the Danish Association of Pharmaceutical Industries for providing education on pharmacoepidemiology. No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the help of INFARMED with providing the NHS data for Portugal, Helga Festöy from NoMA with critique details of the pricing policy for generics in Norway, as well as the help of the NHS Information Centre in Leeds for the provision of the data for England. We would also acknowledge the advice from Fredrik Granath at the Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden regarding statistical analyses when typically multiple supply and demand-side measures are introduced during the study period. The study was in part supported by grants from the Karolinska Institutet.

Appendix

Table A1.

Pricing approaches for generics and major demand-side measures principally for the PPIs and statins among the different European countries typically up to 2007 (Von Ferber et al., 1999; Schmacke and Lauterberg, 2002; Wessling and Lundin, 2006; Hyde, 2007; Magrini et al., 2007; Office of Fair Trading, 2007; Peura et al., 2007; Sakshaug et al., 2007; Fattore and Jommi, 2008; Festoy et al., 2008; Godman et al., 2008a,b, 2009b,c, 2010a,b,c; Simoens, 2008a; Teixeira and Vieira, 2008; Wettermark et al., 2008, 2009a,b, 2010a; Eriksson and Lundin, 2009; Adamski et al., 2010; Barry et al., 2010; DoH, 2010; Martikainen et al., 2010; McGinn et al., 2010; Sermet et al., 2010; Stock et al., 2010).

| Country | Key supply and demand-side reforms |

|---|---|

| AT – Austria | Generic pricing (mixed approach) Initially first generic 48% below originator, with originator mandated to lower its price by 30% for continued reimbursement; second generic 15% below the first to be reimbursed; third generic 10% lower than the second (overall 60% below pre-patent loss prices) Market forces after that with physicians incentivized to prescribe cheapest branded generics Demand-side measures Education – includes guidance and benchmarking Economics – includes financial incentives for physicians to enhance efficient prescribing including the cheapest generic in the class Enforcement – Prescribing restrictions for both atorvastatin and rosuvastatin (prior approval scheme via the Chief Medical Officer of the patient's social health insurance fund) |

| DE – Germany | Generic pricing Market forces for generics along with reference pricing in the class (PPIs and statins) Demand-side measures (variation among the States) Educational initiatives – include prescribing guidance, quality circles and web based training programs Economics – includes budgets, financial incentives linked with prescribing targets and patient co-payments for a more expensive molecule than the referenced priced product (molecule or class) Engineering – includes Disease Management programs, price: volume agreements, rebate contracts between pharmaceutical companies and Sickness Funds and prescribing targets Enforcement – Atorvastatin delisted from the normal reimbursement list in 2003 following the instigation of reference pricing for the statins (“Jumbo Class”) |

| EE – Estonia | Generic pricing Third generic 43% below originator prices; market forces after that Demand-side measures Education – prescribing information to physicians Economics includes co-payment for the PPIs and statins PPIs – 50% co-payment Statins – 10–25% co-payment, rosuvastatin 50% co-payment in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia (total cholesterol > 8 mmol/l) and following a CV event (total cholesterol > 4.5 mmol/l) Enforcement for the statins – reimbursement only for restricted indications otherwise 100% co-payment |

| ES – Spain and regions (Catalonia) | Generic pricing Currently market forces driving down generic prices. This may change to a mixed approach Demand-side measures (some variation among Autonomous Communities including Catalonia) Education – includes benchmarking, guidance and educational courses Economics – includes financial incentives for physicians to meet agreed prescribing targets Engineering – includes prescribing targets Enforcement – includes mandatory for pharmacists to dispense cheapest molecule if the prescribed product is more expensive than current reference price, which is usually a generic. This must be generic if the same price as the drug prescribed. No opportunity for patients to cover any additional costs themselves |

| FI – Finland | Generic pricing Mixed approach to the pricing of generics. The price of the first generic has to be 40% lower than the price of the original product to be reimbursed Prices of subsequent generics must not be higher than the first generic to be reimbursed with market forces driving down prices with the introduction of generic substitution with the cheapest product from 2003. Substitution mandatory unless forbidden by the physician or patient; although there can be higher co-payments for more expensive products Demand-side measures Education – clinical guidelines as well as EBM initiatives to enhance the quality of prescribing. However, no prescribing targets as seen in a number of other European countries Economics – principally via patient co-payments 2001: PPIs – €8.41/purchase plus 50% co-payment (Basic Refund Category), similarly for statins for most patients. Patients with familial hypercholesterolemia or coronary artery disease entitled to lower co-payment at €4.20/ purchase and 25% co-payment 2007: PPIs 58% co-payment; similarly for the statins unless familial hypercholesterolemia or coronary artery disease entitlement where only 28% co-payment (applied to 15% of statin users) Enforcement – in 2006 atorvastatin and rosuvastatin restricted to second line as appreciably more expensive than other statins with limited additional benefit (restriction for atorvastatin subsequently abolished in 2009 with the availability of generic atorvastatin and reference pricing for the molecule) |

| FR – France | Generic pricing Prescriptive pricing for generics with the first generic priced 55% below the originator for reimbursement. Prices further reduced by 7% after 18 months. Demand-side measures Education – includes campaigns to enhance the prescribing and dispensing of generics through for instance benchmarking of physician prescribing and campaigns to allay fears regarding generics Economics Incentives to physicians, patients and pharmacists to enhance the prescribing and dispensing of generics versus originators including encouraging physicians to prescribe by INN name Co-payments – working out on average 20% for PPIs and statins (when factoring in patients with long term illness) Engineering Price: volume agreements for existing compounds) Campaigns from 2009 to enhance the prescribing of generics in a class through prescribing targets linked with financial incentives (CAPI – Contrats d'amélioration des pratiques individuelles) prescribing targets (engineering) |

| GB – England | Generic pricing Market forces with transparency in pricing of generics coupled with high INN prescribing. This has typically resulted in low prices for generics Demand-side measures (national and local with some variation among Primary Care Trusts) Education – includes for instance national and local prescribing guidance (e.g., NICE, British National Formulary and PCT prescribing guidance), benchmarking and academic detailing Economics – budget devolution, Practice Based Commissioning and physician financial incentives Engineering – includes Better Care, Better Value indicators for low cost PPIs and statins as well as prescribing support programs encouraging active therapeutic substitution. In addition, proactively managing the introduction of new generics through encouraging the prescribing of patent protected products in a class that will soon lose their patent ahead of other single sourced products in a class |

| GB – Scotland | As for England However, budgets not devolved locally (GPs responsible for their drug budgets but not accountable) |

| HR – (Croatia) | Generic pricing Mixed approach. The first generic should not be priced higher than 70% of the originator pre-patent price to be reimbursed (originator price dropping by at least 10%) Second generic – a maximum of 90% of the price of the first generic for reimbursement; third generic maximum price of 90% of the second with market forces further lowering prices with patients paying the difference for a more expensive molecule than the current reference Demand-side measures Education – National formulary providing prescribing guidance, with only a limited number of treatment guidelines Engineering includes – price: volume agreements – although applies to new drugs Economics includes higher co-payments for more expensive products that the reference molecule. It also includes co-payments for the statins and PPIs For the statins – in 2003 – 25% co-payment for secondary prevention in patients with ischemic heart disease or cerebrovascular disease and with patients with diabetes with a TC > 5 mmol/l; 75% for patients for primary prevention whose 10-year chance of CHD >20% or will be at the age of 60. Reimbursement only if treatment initiated for patients <70 years In 2006, similar to 2003 for secondary prevention (25%). Primary prevention includes TC > 7 mmol/l after 3 months diet (75% co-payment). In 2008 (outside study period), no co-payment for patients meeting criteria for primary and secondary prevention – co-payment only if they wish originator atorvastatin For the PPIs – typically no co-payment in patients where H2 blockers no longer working for esophageal reflux, alternatively for Zollinger Elisonov syndrome or eradication of Helicobacter pylori; otherwise 100% co-payment Enforcement – Access to patient history to check criteria for reimbursement, e.g., statins and PPIs |

| IE – Republic of Ireland | Generic pricing Overall mixed approach with the recent introduction of a two step price reduction process for patent expired products – 20% reduction on patent expiry (in 2007) followed by a further 15% reduction after 22 months (in 2011) (expected to realise €275 mn by 2011) Demand-side measures Limited demand-side reforms to date to encourage the prescribing of generic drugs first line |

| IT – Italy | Generic pricing The first generic 20% below the originator; market forces after that Demand-side measures (Variation among health authorities) Educational initiatives – guidelines, academic detailing and benchmarking Economics – financial incentives for GPs, additional patient co-payment for more expensive molecules than the reference molecule Engineering – capping ambulatory care budgets Enforcement – prescribing restrictions for certain indications |

| LT – Lithuania | Generic pricing Currently first generic 30% below originator, second and third generics 10% below this; market forces after that Demand-side measures Education – some guidelines in place to encourage rational use of medicines but not obligatory. In addition auditing of prescribing habits with possible financial penalties for excessive costs Economics – includes co-payments for PPIs and statins, as well as possible financial penalties for physicians (above) PPIs – 50%+ for majority of indications Statins - Only 20% co-payment. Initially statins only reimbursed for secondary prevention (post event) and for only 6 months. Reimbursement restrictions now lifted for generic statins Engineering – includes obligatory INN prescribing unless concerns ( compulsory from 2010 unless prior authorization from Hospital or Polyclinic Therapeutic Committee) Enforcement (statins only) – reimbursement only post AMI and only for 6 months (reimbursement restrictions now lifted for generic statins). In addition, the first prescription must be written by a cardiologist otherwise 100% co-payment |

| NO – Norway | Generic pricing Aggressive prescriptive pricing policy for generics with high volume generics 85% below originator prices Demand-side measures Limited educational initiatives during the study period Enforcement PPIs – prescribing of esomeprazole restricted in 2007. Specialists though required to verify the diagnosis and recommend therapy Statins – atorvastatin restricted from 2005 (rosuvastatin not reimbursed) with physicians encouraged to actively substitute patients currently prescribed atorvastatin. Spot checks undertaken amongst physicians if abuse suspected |

| PO – Poland | Generic pricing Market forces driving down generic prices. In addition reference pricing in a class and across therapeutic groups (ATC Levels 3 and 4) Demand-side measures Education – generally limited educational interventions; although variable among the regions Economics – includes co-payment for the indication as well as additional co-payment for a more expensive brand than the reference product (molecule, class, or therapeutic area) PPIs – 30% (apart from esomeprazole which is not reimbursed) Statins – 30% (apart from rosuvastatin which is not reimbursed) Enforcement – Pharmacists are obliged to inform patients about generic products if they have the same active ingredient, dosage, package and route of administration as the prescribed product but cheaper (as branded generics in Poland) |

| PT – Portugal | Generic pricing Mixed approach to the pricing of generics with the first generic priced at least 35% below the originator; this reduces to 20% if the originator price is below €10/pack. Further price reductions in 2005, 2007, and 2008 2005 and 2007 – 6% price reduction for all reimbursed medicines After March 2007 also annual price reductions for generics depending on the market share of each active substance (5, 9, or 12%) 2008 – further 30% price reduction for generic medicines 2010 – further changes to try and reduce prices within homogeneous groups, i.e., same active substance, pharmaceutical form, strength and route of administration In addition, ongoing activities by pharmaceutical companies to suspend market authorization for generics as a counter measure. The official database from Infarmed (July 2010) includes 17 active substances and more than 500 medicines (packages) where marketing authorization has been suspended |

| Demand-side measures Education – includes guidelines (although not mandatory) and campaigns promoting generics. The latter include patient campaigns via TV, radio, leaflets in hospitals and community pharmacies as well as physicians updated every quarter by INFARMED of available generics Economics – includes establishing a Reference Price System (RPS) in 2002 defining a fixed amount paid by the NHS for homogeneous groups. In May 2010 no co-payment for pensioners (100% reimbursement) whose income is below the national minimum wage (the so called Special Regime). In June 2010, new legislation reimbursing 100% only the five cheapest medicines in a homogeneous group Engineering – Agreements between the Portuguese Pharmaceutical Industry (represented by APIFARMA) and the Ministry of Health with the objective of limiting the growth in the NHS expenditure on pharmaceuticals Enforcement – includes since 2002 an obligation for physicians to prescribe by INN for medicines with approved generics; however they can prohibit substitution where patient concerns. Pharmacists are allowed to substitute generics where physicians have prescribed by INN name and have not prohibited substitution, and should also inform patients about generic prices versus originators (however no financial incentives for this) |

|

| RS – Serbia | Generic Pricing Mixed approach with the first generic priced at least a minimum of 80% of average current prices in three reference countries (Slovenia, Croatia and Italy) Subsequent generics should be priced similar or lower to gain market share with the lowest price product establishing the reference price for the molecule In addition, to help further lower prices originator and generic drugs must now have the same price for reimbursement with no opportunity for patients to pay an additional co-payment for a more expensive product Demand-side measures Economics - Patients initially required to pay an additional co-pay for a more expensive product than the current reference price (same INN name - ATC Level 5) - now changing (above). Prescribing efficiency helped by early availability of generics – similar to the situation in Poland (above) Enforcement – Prior authorization schemes in place for selected premium priced drugs based on step therapy approaches |

| SE – Sweden | Generic pricing Market forces driving down prices with compulsory generic substitution Demand-side measures (some variation among the Counties) Education – includes a range of measures incorporating prescribing guidance and guidelines, routine benchmarking against colleagues and against recommended drugs, as well as electronic prescribing support systems Economics – includes devolved budgets and financial incentives Engineering – includes prescribing targets such as % of statins as generic statins Enforcement – includes prescribing restrictions for rosuvastatin (since launch) and atorvastatin (post 2007) |

| SI – Slovenia | Generic pricing First generic no higher than an average of 82% of prices in Austria, France and Germany; market forces after that Demand-side measures Education – includes the Health Insurance Institute organizing therapeutic meetings and undertaking audits of prescribing habits Economics – includes additional co-payments for more expensive compounds than the reference product Enforcement – includes prescribing restrictions for certain drugs based on their more limited value versus current standards |

| TR – Turkey | Generic pricing The first generic must be priced no higher than 66% of the originator's pre-patent loss price; subsequently subject to a 11% price reduction Demand-side measures Education – limited activities to date Enforcement – some prescribing restrictions but not applying to PPIs or statins |

References

- Adamski J., Godman B., Ofierska-Sujkowska G., Osinska B., Herholz H., Wendykowska K., Laius O., Jan S., Sermet C., Zara C., Kalaba M., Gustafsson R., Garuoliene K., Haycox A., Garattini S., Gustafsson L. L. (2010). Review of risk sharing schemes for pharmaceuticals: considerations, critical evaluation and recommendations for European payers. BMC Health Serv. Res. 10, 153. 10.1186/1472-6963-10-153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AFSSAPS. (2005). Prise en Charge Therapeutic du Patient Dyslipidemique. Available at: http://www.afssaps.fr/var/afssaps_site/storage/original/application/da2c055ce7845afe44d7aaca7c3f4de8.pdf [Accessed 20 July 2010].

- Allenet B., Barry H. (2003). Opinion and behaviour of pharmacists towards the substitution of branded drugs by generic drugs: survey of 1,000 community pharmacists. Pharm. World Sci. 25, 197–202 10.1023/A:1025840920988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett A., Roques T., Small M., Smith R. (2006). How much will Herceptin really cost? BMJ 33, 1118–1120 10.1136/bmj.39008.624051.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry M., Usher C., Tilson L. (2010). Public drug expenditure in the Republic of Ireland. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 10, 239–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton S. (2001). Using clinical evidence. BMJ 322, 503–504 10.1136/bmj.322.7285.503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beishon J., McBride T., Scharaschkin A. (2007). Prescribing Costs in Primary Care. National Audit Office. Available at: http://www.nao.org.uk/publications/0607/prescribing_costs_in_primary_c.aspx?alreadysearchfor=yes [Accessed 20 June 2010].

- Bergman U., Gimsson A., Wahba A., Westerholm B. (eds). (1979). Studies in Drug Utilization – Methods and Applications. Copenhagen: World Health Organization Regional Publications; 393066 [Google Scholar]

- Bero L., Grilli R., Grimshaw J., Harvey E., Oxman A., Tomson M., On Behalf of the Cochrane Effective Practice Organisation of Care Review Group. (1998). Getting research into practice. BMJ 317, 465–468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkett D. (2002). The future of ATC/DDD and drug utilisation research. WHO Drug Inf. 16, 238–240 [Google Scholar]

- Blaszczyk P., Janiszewski R., Bondaryk K. (2007). Poland – Pharma Profile; Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Information. Available at: http://ppri.oebig.at/Downloads/Results/Poland_PPRI_2007.pdf [Accessed 20 August 2010].

- Cameron A., Ewen M., Ross-Degnan D., Ball D., Laing R. (2009). Medicine prices, availability and affordability in 36 developing and middle-income countries; a secondary analysis. Lancet 273, 240–249 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61762-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caroll J. (2005). Plans struggle for control of speciality pharma costs. Manag. Care 14, 41–48 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coma A., Zara C., Godman B., Augusti A., Diogene E., Wettermark B., Haycox A. (2009). Policies to enhance the efficiency of prescribing in the Spanish Catalan Region: impact and future direction. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 9, 569–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke J., Mason A., Drummond M., Towse A. (2005). Medication management in English national health service hospitals. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 62, 189–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer J., Benedict A., Muszabek N., Keskinaslan A., Khan Z. M. (2008). The significance of compliance and persistence in the treatment of diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidaemia: a review. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 62, 76–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DoH. (2006). Good Practice Guidance on Managing the Introduction of New Healthcare Interventions and Links to NICE Technology Appraisal Guidance. Available at: www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_064983 [Accessed 20 July 2010].

- DoH. (2008). How to Put NICE Guidance into Practice and Improve the Health and Wellbeing of Communities: Practical Steps for Local Authorities. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/media/163/5A/HowputNICEguidancepracticelocal.pdf [Accessed 20 July 2010].

- DoH. (2010). Better Care Better Value Indicator. Low Cost PPI Prescribing. Available at: http://www.productivity.nhs.uk/Def_IncreasingLowCostPPIPrescribing.aspx [Accessed 3 July 2010].

- Duerden M., Hughes D. (2010). Generic and therapeutic substitutions in the UK: are they a good thing? Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 70, 335–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elshaug A. G., Moss J. R., Littlejohns P., Karnon J., Merlin T. L., Hiller J. E. (2009). Identifying existing health care services that do not provide value for money. Med. J. Aust. 190, 269–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson G., Lundin D. (2009). The Review of Medicines for Lipid Disorders. Available at: http://www.tlv.se/Upload/Genomgangen/summary-lipids.pdf [Accessed 20 July 2010].

- Ess S., Schneeweiss S., Szucs T. (2003). European healthcare policies for controlling drug expenditure. Pharmacoecnomics 21, 89–103 10.2165/00019053-200321020-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fattore G., Jommi C. (2008). The last decade of Italian pharmaceutical policy – instability or consolidation? Pharmacoeconomics 26, 5–15 10.2165/00019053-200826010-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fein O. (2010). Keep the single payer vision. Med. Care 48, 759–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festoy H., Sveen K., Yu L.-M., Gjönnes L., Gregersen T. (2008). Norway – Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Information. Available at: http://ppri.oebig.at/Downloads/Results/Norway_PPRI_2008.pdf [Accessed 3 August 2010].

- Frank R. (2007). The ongoing regulation of generic drugs. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 1993–1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garattini S., Bertele V., Godman B., Wettermark B., Gustafsson L. L. (2008). Enhancing the rational use of new medicines across European healthcare systems – a position paper. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 64, 1137–1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godman B., Bucsics A., Burkhardt T., Haycox A., Seyfried H., Wieninger P. (2008a). Insight into recent reforms and initiatives in Austria; implications for key stakeholders. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 8, 357–371 10.1586/14737167.8.4.357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godman B., Haycox A., Schwabe U., Joppi R., Garattini S. (2008b). Having your cake and eating it: Office of Fair Trading proposal for funding new drugs to benefit patients and innovative companies. Pharmacoeconomics 26, 91–98 10.2165/00019053-200826020-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godman B., Shrank W., Wettermark B., Andersen M., Bishop I., Burkhardt T., Garuoliene K., Kalaba M., Laius O., Joppi R., Sermet C., Schwabe U., Teixeira I., Tulunay F. C., Wendykowska K., Zara C., Gustafsson L. L. (2010a). Use of generics – a critical cost containment measure for all healthcare professionals in Europe? Pharmaceuticals 3, 2470–2494 10.3390/ph3082470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godman B., Bucsics A., Burkhardt T., Schmitzer M., Wettermark B., Wieninger P. (2010b). Initiatives to enhance renin-angiotensin prescribing efficiency in Austria: impact and implications for other countries Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 10, 199–207 10.1586/erp.10.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godman B., Shrank W., Andersen M., Berg C., Bishop I., Burkhardt T., Garuoliene K., Herholz H., Joppi R., Kalaba M., Laius O., McGinn D., Samaluk V., Sermet C., Schwabe U., Teixeira I., Tilson L., Tulunay F. C., Vlahović-Palčevski V., Wendykowska K., Wettermark B., Zara C., Gustafsson L. L. (2010c). Comparing policies to enhance the utilisation generics across Europe: impact and global implications. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 10, 707–722 10.1586/erp.10.72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godman B., Wettermark B. (2009a). “Impact of reforms to enhance the quality and efficiency of statin prescribing across 20 European countries,” in 9th Congress of the European Association for Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Edinburgh, eds. Webb D., Maxwell S., Medimond International Proceedings – Medimond. Pianoro s.t.l. 65–69 [Google Scholar]

- Godman B., Wettermark B. (2009b). “Trends in consumption and expenditure of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in 20 European countries,” in 9th Congress of the European Association for Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Edinburgh, eds Webb D., Maxwell S., Medimond International Proceedings – Medimond. Pianoro s.t.l. 71–75 [Google Scholar]

- Godman B., Wettermark B., Hoffman M., Andersson K., Haycox A., Gustafsson L. L. (2009a). Multifaceted national and regional drug reforms and initiatives in ambulatory care in Sweden; global relevance. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 9, 65–83 10.1586/14737167.9.1.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godman B., Schwabe U., Selke G., Wettermark B. (2009b). Update of recent reforms in Germany to enhance the quality and efficiency of prescribing of proton pump inhibitors and lipid-lowering drugs. Pharmacoeconomics 27, 1–4 10.2165/00019053-200927050-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godman B., Burkhardt T., Bucsics A., Wettermark B., Wieninger P. (2009c). Impact of recent reforms in Austria on utilisation and expenditure of PPIs and lipid lowering drugs; implications for the future. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 9, 475–484 10.1586/erp.09.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouya G., Reichart B., Bidner A., Weissenfels R., Wolzt M. (2008). Partial reimbursement of prescription chages for generic drugs reduces costs fr both healh insurance and patients. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 120, 89–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grol R., Grimshaw J. (2003). From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet 362, 1225–1230 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14546-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumbs P., Verschuren W., Souverein P., Mantel-Teeuwisse A. K., de Wit G. A., de Boer A., Klungel O. H. (2007). Society already achieves economic benefits from generic substitution but fails to do the same for therapeutic substitution. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 64, 680–685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkilä R., Mäntyselkä P., Hartikainen-Herranen K., Ahonen R. (2007). Customers’ and physicians’ opinions of experiences with generic substitution during the first year in Finland. Health Policy (New York) 82, 366–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde R. (2007). Doctors to pay for patients’ medicine in Germany. Lancet 370, 1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack A. (2008). Balancing Big Pharma's books. BMJ 336, 418–419 10.1136/bmj.39491.469005.94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones I. M., Greenfield S., Bradley P. (2001). Prescribing new drugs: qualitative study of influences on consultants and general practioners. BMJ 323, 378–381 10.1136/bmj.323.7309.378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjoenniksen I., Lindbaek M., Grannas A. (2006). Patients’ attitudes towards and experiences of generic drug substitution in Norway. Pharm. World Sci. 28, 284–289 10.1007/s11096-006-9043-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp C., Vandevelde F. (2006). Use of international nonproprietary names (INN) among members. ISDB Newsl. 20, 2–4 [Google Scholar]

- Krska J., Godman B. (2010). Medicines Management in Pharmacy in Public Health, 2010. London: RPS Publishing; (in press). [Google Scholar]

- Lee T., Emanuel E. (2008). Tier 4 drugs and the fraying of the social compact. N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 333–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magrini N., Formoso G., Marata A., Capelli O., Maestri E., Voci C., Nonino F., Brunetti M., Paltrinieri B., Maltoni S., Magnano L., Bonacini M. I., Daya L., Viani N. (2007). Randomised controlled trials for evaluating the prescribing impact of information meetings led by pharmacists and of new information formats in general practice in Italy. BMC Health Services Research 7, 158. 10.1186/1472-963-7-158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martikainen J., Saastamoinen L., Korhonen M., Enlund H., Helin-Salmivaara A. (2010). Impact of restricted reimbursement on the use of statins in Finland. Med. Care 48, 761–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinn D., Godman B., Lonsdale J., Way R., Wettermark B., Haycox A. (2010). Initiatives to enhance the efficiency of statin and proton pump inhibitor prescribing in the UK; impact and implications. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 10, 73–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MeReC Extra. (2006). NICE Appraises Statins. Available at: http://www.npc.co.uk/ebt/merec/cardio/cdlipids/resources/merec_extra_no21.pdf [Accessed 20 July 2010].

- Moon J., Flett A., Godman B., Grosso A., Wierzbicki A. (2010). Getting better value from the NHS drug budget. BMJ 341, c6449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health Clinical Excellence. (2006). Statins for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Events. Technology Appraisal 94 and Related Costing Template and Report. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/ [Accessed 20 July 2010].

- Norman C., Zarrinkoub R., Hasselström J., Godman B., Granath F., Wettermark B. (2009). Potential savings without compromising the quality of care. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 63, 1320–1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Fair Trading (UK). (2007). The Pharmaceutical Price Regulation System: An OFT Study. Annexe A: Market for Prescription Pharmaceuticals in the NHS. London: The Office of Fair Trading; [online]. Available at: http://www.oft.gov.uk/shared_oft/reports/comp_policy/oft885a.pdf [Accessed 3 July 2010]. [Google Scholar]

- Pegler C., Underhill J. (2005). Evaluating promotional material from industry: an evidence-based approach. Pharm. J. 274, 271–274 [Google Scholar]

- Peura S., Rajaniemi S., Kurkijärvi U. (2007). Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Information Finland. Available at: http://ppri.oebig.at/Downloads/Results/Finland_PPRI_2007.pdf [Accessed 2 August 2010].

- Prosser H., Almond S., Walley T. (2003). Influences on GPs’ decision to prescribe new drugs – the importance of who says what. Fam. Pract. 20, 61–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosser H., Walley T. (2005). A qualitative study of GPs’ and PCO stakeholders’ views on the importance and influence of cost on prescribing. Soc. Sci. Med. 60, 1335–1346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rønning M. (2002). A historical overview of ATC/DDD methodology. WHO Drug Inf. 16, 233–234 [Google Scholar]

- Rønning M., Blix H. S., Harbø B. T., Strøm H. (2000). Different versions of the anatomical therapeutic chemical classification system and the defined daily dose – are drug utilisation data comparable? Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 56, 723–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakshaug S., Furu K., Karslstad ø., Rønning M., Skurtveit S. (2007). Switching statins in Norway after new reimbursement policy – a nationwide prescription study. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 64, 476–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmacke N., Lauterberg J. (2002). Criticism of new German chronic disease management is unfair. BMJ 325, 971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sermet C., Andrieu V., Godman B., Van Ganse E., Haycox A., Reynier J. P. (2010). Ongoing pharmaceutical reforms in France; considerations for other countries and implications for key stakeholder groups in France. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 8, 7–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrank W., Cox E., Fischer M., Mehta J., Choudhry N. K. (2009). Patients’ perception of generic medications. Health Affairs 28, 546–556 10.1377/hlthaff.28.2.546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoens S. (2008a). Developing competitive and sustainable Polish generic medicines market. Croat. Med. J. 50, 440–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoens S. (2008b). Generic medicine pricing in Europe: current issues and future perspective. J. Med. Econ. 11, 171–175 10.3111/13696990801939716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoens S. (2008c). Trends in generic prescribing and dispensing in Europe. Exp. Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 1, 497–503 10.1586/17512433.1.4.497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjöborg B., Bäckstrom T., Arvidsson L.-B., Andersén-Karlsson E., Blomberg L. B., Eiermann B., Eliasson M., Henriksson K., Jacobsson L., Jacobsson U., Julander M., Kaiser P. O., Landberg C., Larsson J., Molin B., Gustafsson L. L. (2007). Design and implementation of a point-of-care computerised system for drug therapy in Stockholm metropolitan health region – bridging the gap between knowledge and practice. Int. J. Med. Inform. 76, 497–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock S., Schmit H., Buscher G., Gerber A., Drabik A., Graf C., Lüngen M., Stollenwerk B. (2010). Financial incentives in the German Statutory Health Insurance: new findings, new questions. Health Policy 96, 51–56 10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szecseny J. (2003). Influence of attitudes and behaviour of GPs on prescribing costs. Qual. Saf. Health Care 12, 6–7 10.1136/qhc.12.1.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]