Abstract

BACKGROUND

In patients with chronic infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1 who do not have a sustained response to therapy with peginterferon–ribavirin, outcomes after retreatment are suboptimal. Boceprevir, a protease inhibitor that binds to the HCV nonstructural 3 (NS3) active site, has been suggested as an additional treatment.

METHODS

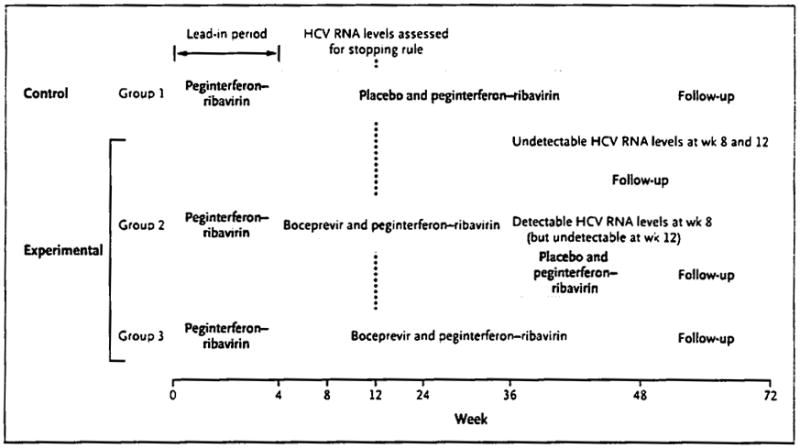

To assess the effect of the combination of boceprevir and peginterferon–ribavirin for retreatment of patients with chronic HCV genotype 1 infection, we randomly assigned patients (in a 1:2:2 ratio) to one of three groups. In all three groups, peginterferon alfa-2b and ribavirin were administered for 4 weeks (the lead-in period). Subsequently, group 1 (control group) received placebo plus peginterferon–ribavirin for 44 weeks; group 2 received boceprevir plus peginterferon–ribavirin for 32 weeks, and patients with a detectable HCV RNA level at week 8 received placebo plus peginterferon–ribavirin for an additional 12 weeks; and group 3 received boceprevir plus peginterferon–ribavirin for 44 weeks.

RESULTS

A total of 403 patients were treated. The rate of sustained virologic response was significantly higher in the two boceprevir groups (group 2, 59%; group 3, 66%) than in the control group (21%, P<0.001). Among patients with an undetectable HCV RNA level at week 8, the rate of sustained virologic response was 86% after 32 weeks of triple therapy and 88% after 44 weeks of triple therapy. Among the 102 patients with a decrease in the HCV RNA level of less than 1 log10 IU per milliliter at treatment week 4, the rates of sustained virologic response were 0%, 33%, and 34% in groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Anemia was significantly more common in the boceprevir groups than in the control group, and erythropoietin was administered in 41 to 46% of boceprevir-treated patients and 21% of controls.

CONCLUSIONS

The addition of boceprevir to peginterferon–ribavirin resulted in significantly higher rates of sustained virologic response in previously treated patients with chronic HCV genotype 1 infection, as compared with peginterferon–ribavirin alone.

More than 170 million people are chronically infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) worldwide.1 The standard treatment is combination therapy with peginterferon and ribavirin.2–4 Of the six HCV genotypes, genotype 1 is the least responsive to currently approved therapies, with rates of sustained virologic response of less than 50%.2,5–7 Thus, there is a large population of patients with few therapeutic options, and direct-acting antiviral therapy has become the focus of investigations regarding treatment for HCV infection.8–11

Boceprevir is a structurally novel peptidomimetic ketoamide protease inhibitor that binds reversibly to the HCV nonstructural 3 (NS3) active site.8 Boceprevir has demonstrated antiviral activity in phase 2 studies of both patients infected with HCV genotype 1 who have not received prior treatment and those who have received prior treatment.8 The primary objective of this phase 3 study of patients with previously treated HCV genotype 1 infection was to compare the safety and efficacy of two therapeutic regimens of boceprevir in combination with peginterferon and ribavirin to therapy with peginterferon and ribavirin alone. The safety and efficacy of boceprevir in previously untreated patients are described in the article by Poordad and colleagues in this issue of the Journal.12

METHODS

STUDY OVERSIGHT

The study protocol is available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org. The trial (HCV RESPOND-2 [Retreatment with HCV Serine Protease Inhibitor Boceprevir and PegIntron/Rebetol 2]) was funded by Schering-Plough (now part of Merck) and was designed, managed, and analyzed by Merck in conjunction with the external academic investigators and members of the external data and safety monitoring board. The academic authors had agreements with the sponsor concerning the confidentiality of the data. The academic authors collected the data, which was then analyzed by the sponsor. The sponsor held the data and made them available to the academic authors. The first draft of the manuscript was written by one academic author and three industry authors. All authors were involved in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; revision of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. All authors vouch for the completeness and accuracy of the data and analyses as well as the fidelity of the study to the protocol.

STUDY PATIENTS

From August through November 2008, we screened 640 patients with HCV genotype 1 infection at 80 sites in North America and Europe. Eligibility criteria included demonstrated responsiveness to interferon (minimum duration of therapy, 12 weeks). We defined patients as having either nonresponse (i.e., a decrease in the HCV RNA level of at least 2 log10 IU per milliliter by week 12 but with a detectable HCV RNA level during the therapy period) or relapse (i.e., an undetectable HCV RNA level at the end of treatment, without subsequent attainment of a sustained virologic response [i.e., with a detectable HCV RNA level during the follow-up period]).

Exclusion criteria included hepatitis B or infection with the human immunodeficiency virus, any other cause of clinically significant liver disease, decompensated liver disease, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, a severe psychiatric disorder, and active substance abuse. Liver-biopsy specimens were assessed for Metavir fibrosis scores and steatosis scores by a single academic author who is a pathologist and was unaware of the assignment of boceprevir or placebo. Possible Metavir fibrosis scores are as follows: a score of 0 indicates no fibrosis, 1 indicates portal fibrosis without septa, 2 indicates portal fibrosis with few septa, 3 indicates numerous septa without cirrhosis, and 4 indicates cirrhosis.

STUDY DESIGN

The primary objective was to compare two treatment regimens containing boceprevir in combination with open-label peginterferon alfa-2b and ribavirin (PegIntron and Rebetol, respectively; Merck) to treatment with peginterferon–ribavirin plus placebo in previously treated adults with chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. Our study was conducted in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice and was approved by the appropriate institutional review boards and regulatory agencies. All patients provided written informed consent before randomization.

Patients were randomly assigned, in a 1:2:2 ratio with the use of an interactive voice-response system, to one of three treatment groups, with stratification according to previous response to therapy (nonresponse or relapse) and HCV sub-genotype (1a or 1b) as determined by means of sequencing of the HCV 5′ noncoding region (Trugene).13 Patients with HCV genotype 1 infection whose HCV subtype could not be classified were randomly assigned to one of the treatment groups. The HCV genotype 1 subtype was also determined by means of sequencing of the nonstructural 5B (NS5B) region (Virco).

The study design is illustrated in Figure 1. For purposes of the study doses, peginterferon alfa-2b was administered subcutaneously at a dose of 1.5 μg per kilogram of body weight once weekly, and ribavirin was administered at a divided daily dose of 600 to 1400 mg per day on the basis of body weight. Treatment with boceprevir consisted of oral administration at a dose of 800 mg three times daily (to be taken with food and with an interval of 7 to 9 hours between doses) in four capsules of 200 mg each. Placebo was matched to boceprevir. The study was double-blinded regarding the administration of boceprevir.

Figure 1. Study Design.

For 13 patients for whom the HCV RNA measurement at the end of the follow-up period was missing, the measurement obtained at 12 weeks of follow-up was carried forward; of these patients, a sustained virologic response was achieved in 2 (1 in group 2 and 1 in group 3). Patients with a detectable HCV RNA level at week 12 were considered to have had treatment failure (according to the stopping rule). Patients in group 1 were offered the opportunity to receive treatment with boceprevir plus peginterferon–ribavirin by means of an access study or to proceed to the follow-up phase of this study. Patients in groups 2 and 3 proceeded to the follow-up phase of this study. The primary efficacy end point was assessed at the end of the follow-up phase. The x-axis numbers are not to scale.

During the 4-week lead-in period, all patients received peginterferon plus ribavirin. Subsequent treatment varied according to group. Group 1 (the control group) received peginterferon–ribavirin plus boceprevir-matched placebo for 44 weeks. Group 2 received a response-guided therapy regimen consisting of boceprevir plus peginterferon–ribavirin, for 32 weeks; according to the week 12 stopping rule, patients with an undetectable HCV RNA level at weeks 8 and 12 completed therapy at week 36, whereas those with a detectable HCV RNA level at week 8 (but an undetectable level at week 12) received peginterferon–ribavirin plus placebo for an additional 12 weeks. Group 3 received boceprevir and peginterferon-ribavirin for 44 weeks.

The stopping rule applied in all groups was that failure to achieve an undetectable HCV RNA level at week 12 resulted in discontinuation of all treatment and advancement to follow-up.

Plasma HCV RNA levels were measured with the use of the TaqMan 2.0 assay (Roche Diagnostics), which has lower limits of quantification and detection of 25 and 9.3 IU per milliliter, respectively; the lower limit of detection was used for decision making at various points throughout the study.13 Measurement was performed at the screening visit, at baseline, every 2 weeks through week 12, and then at weeks 16, 20, 24, 30, 36, 42, and 48, as well as at weeks 4,12, and 24 of the follow-up period.

SAFETY

Adverse events were graded by investigators according to a modified World Health Organization grading system. Non–life-threatening adverse events were managed by means of dose reduction. The recommended guidelines for a two-step dose reduction of peginterferon and for a three-step dose reduction of ribavirin were similar to those previously described (as is summarized in the Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org).7,14–16

Viral breakthrough was defined as achievement of an undetectable HCV RNA level and subsequent occurrence of an HCV RNA level greater than 1000 IU per milliliter. Incomplete virologic response and rebound was defined as an increase of 1 log10 IU per milliliter in the HCV RNA level from the nadir, with an HCV RNA level greater than 1000 IU per milliliter (if both samples being compared were collected the same number of days after the last peginterferon injection). In cases in which the timing between the peginterferon injection and the HCV RNA sample collection was different for the two samples, an increase of 2 log10 IU per milliliter was required to meet this criterion. If a patient had virologic breakthrough or an incomplete virologic response and rebound while receiving therapy, boceprevir treatment could be discontinued, but peginterferon–ribavirin could be continued for up to 48 weeks with appropriate clinical follow-up.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Analyses regarding the primary objective included data from all patients who received at least one dose of any study medication. The key secondary objective was to compare the two boceprevir regimens with the peginterferon–ribavirin regimen in patients who completed the lead-in period and received at least one dose of placebo or boceprevir. Specifically, comparisons for the primary and key secondary objectives were made between group 3 and group 1 and between group 2 and group 1.

The primary efficacy end point was a sustained virologic response, defined as an undetectable plasma HCV RNA level at week 24 of the follow-up period. Secondary and other efficacy analyses were performed to calculate the proportion of patients with an early response (i.e., an undetectable HCV RNA level at week 8) in whom a sustained virologic response was achieved, as well as the proportion of patients with a relapse.

The primary statistical comparison was carried out with the use of a two-sided Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel chi-square test with adjustment for the baseline stratification factors. The study had a statistical power of 90% to detect an absolute improvement in the rate of sustained virologic response by 21 percentage points over the rate in group 1 (assuming response rates of 22% in the control group and 43% in the boceprevir groups) with the use of a two-sided chi-square test and an alpha value of 0.05.

To control for type I error in the primary analysis, a step-down approach was used. Group 3 was first compared against group 1. If the P value for the comparison was less than 0.05, the next comparison — of group 2 and group 1 — was carried out. A similar step-down approach was prespecified to control for the type I error regarding the key secondary objective. To account for multiplicity between the primary and key secondary analyses, the key secondary analyses were conducted only if the significance of the primary comparisons was established. P values calculated for sustained virologic response are provided for only the two prespecified primary and key secondary comparisons.

Summary statistics are reported for each of the three treatment regimens for subgroups of patients defined according to prespecified baseline characteristics. Multivariable logistic-regression analyses involving treatment regimen and prespecified baseline characteristics were performed to evaluate sustained virologic responses. A stepwise procedure was used to identify independent predictors of sustained virologic response (with P=0.05 as the threshold level for variables to be entered into the model and retained in the final model). In addition, we fit a stepwise logistic-regression model of the response (decrease from baseline in the HCV RNA level of ≥1.0 log10 IU per milliliter vs. <1.0 log10 IU per milliliter) at treatment week 4 and baseline characteristics.

RESULTS

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS

A total of 640 patients were evaluated for enrollment in the study; 403 were enrolled and underwent randomization and treatment (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). The baseline demographic characteristics were balanced among the three treatment groups (Table 1), with the exception of high viral load (group 2 vs. group 1, P=0.04). The mean age was 52.7 years, 12% of patients were black, and the mean body weight was 84.9 kg. Approximately 88% of patients had a high viral load (an HCV RNA level >800,000 IU per milliliter) at baseline. The prevalence of infection with HCV genotypes 1a and 1b was similar (47% and 44%, respectively). A total of 19% of patients had a Metavir fibrosis score of 3 or 4. The majority of patients (64%) had had a relapse after previous HCV therapy.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Patients, According to Treatment Group.*

| Characteristic | Group 1 (N = 80) | Group 2 (N = 162) | Group 3 (N = 161) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age—yr | 52.9 | 52.9 | 52.3 |

| Male sex — no. (%) | 58(72) | 98 (60) | 112 (70) |

| Race — no. (%)† | |||

| White | 67 (84) | 142 (88) | 135 (84) |

| Black | 12 (15) | 18 (11) | 19 (12) |

| Other | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 7 (4) |

| Region — no. (%) | |||

| North America | 51(64) | 115 (71) | 119 (74) |

| European Union | 29 (36) | 46 (28) | 42 (26) |

| Latin America | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Body-mass index‡ | 28.2±4.3 | 28.8±4.6 | 28.2±4.6 |

| HCV subtype — no. (%)§ | |||

| 1a | 46 (58) | 94 (58) | 96 (60) |

| 1b | 34 (42) | 66 (41) | 61 (38) |

| Missing data | 0 | 2 (1) | 4 (2) |

| ALT > upper limit of the normal range — no. (%) | 55 (69) | 109 (67) | 115 (71) |

| Platelet count — no. (%)¶ | |||

| ≥100,000 to<150,000/μl | 10 (12) | 21 (13) | 19 (12) |

| ≥150,000/μl | 70 (88) | 141 (87) | 142 (88) |

| High viral load (>800,000 IU/ml) — no. (%)| | 65 (81) | 147 (91) | 141 (88) |

| Metavir fibrosis score — no. (%)** | |||

| 0, 1, or 2 | 61 (76) | 117(72) | 119 (74) |

| 3 or 4 | 15 (19) | 32 (20) | 31 (19) |

| Cirrhosis — no. (%)** | 10 (12) | 17 (10) | 22 (14) |

| Steatosis — no. (%)** | |||

| 0% | 23 (29) | 36 (22) | 45 (28) |

| >0–4% | 53 (66) | 113 (70) | 105 (65) |

| Previous therapy — no. (%) | |||

| Peginterferon alfa-2a | 42 (53) | 79 (49) | 68 (42) |

| Peginterferon alfa-2b | 38 (48) | 83 (51) | 93 (58) |

| Prior nonresponse — no. (%)†† | 29 (36) | 57 (35) | 58 (36) |

| Prior relapse — no. (%)†† | 51(64) | 105 (65) | 103 (64) |

ALT denotes alanine aminotransferase, and HCV hepatitis C virus.

Race was self-reported.

The body-mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

The HCV subtype was ascertained by means of sequencing of the nonstructural 5B (NS5B) region.

Eligibility criteria included an absolute neutrophil count of 1500 per cubic millimeter or higher for nonblacks and 1200 per cubic millimeter or higher for blacks, a platelet count of 100,000 per cubic millimeter or higher, and a hemoglobin level of 12 g per deciliter or more for women and 13 g per deciliter or more for men.

For a viral load >800,000 IU per milliliter, P=0.04 for the comparison of group 2 versus group 1.

Metavir scores and percent steatosis were determined on the basis of assessment of liver-biopsy specimens by a single pathologist who was unaware of the assignment to boceprevir or placebo. A total of 28 patients (4 in group 1,13 in group 2, and 11 in group 3) had missing data regarding these characteristics. Possible fibrosis scores are as follows: 0 (indicating no fibrosis), 1 (indicating portal fibrosis without septa), 2 (indicating portal fibrosis with few septa), 3 (indicating numerous septa without cirrhosis), and 4 (indicating cirrhosis).

Prior nonresponse was defined as a decrease in the HCV RNA level of at least 2 log10 IU per milliliter by week 12 of prior therapy but a detectable HCV RNA level throughout the course of prior therapy, without subsequent attainment of a sustained virologic response. Prior relapse was defined as an undetectable HCV RNA level at the end of prior therapy, without subsequent attainment of a sustained virologic response.

EFFICACY

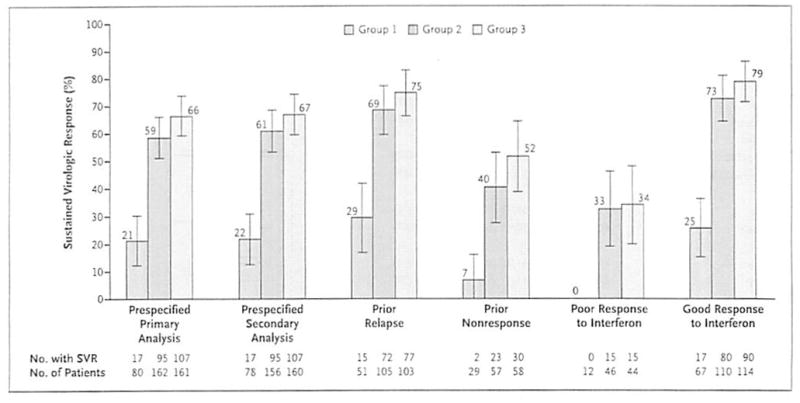

In the primary-analysis population, rates of sustained virologic response were significantly higher among patients receiving boceprevir than among those treated with peginterferon–ribavirin alone (Fig. 2), with overall rates of sustained virologic response of 21%, 59%, and 66% in groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively (P<0.001). This increase seen with boceprevir was due largely to end-of-treatment rates of response (i.e., an undetectable HCV RNA level) that were greater in group 2 (70%) and group 3 (77%) than in group 1 (31%), as well as a decreased rate of relapse in group 2 (in 17 of 111 patients [15%]) and group 3 (in 14 of 121 patients [12%]) as compared with group 1 (in 8 of 25 patients [32%]). Viral breakthrough and incomplete virologic response were infrequent during the treatment period (with either occurring in 1 of 80 patients [1%] in group 1, in 9 of 162 patients [6%] in group 2, and in 7 of 161 patients [4%] in group 3).

Figure 2. Patients with a Sustained Virologic Response, According to Treatment Group and Analysis.

The percentages of patients with a sustained virologic response are shown. The prespecified primary analysis involved all patients who were randomly assigned to a treatment group and received at least one dose of any study medication. The prespecified secondary analysis involved all patients who were randomly assigned to a treatment group and received at least one dose of boceprevir or placebo. Prior relapse was defined as an undetectable HCV RNA level at the end of prior therapy without subsequent attainment of a sustained virologic response. Prior nonresponse was defined as a decrease in the HCV RNA level of at least 2 log10 IU per milliliter by week 12 of prior therapy but a detectable HCV RNA level throughout the course of prior therapy, without subsequent attainment of a sustained virologic response. Poor response to interferon was defined as a decrease in the HCV RNA level of less than 1 log10 IU per milliliter after the 4-week lead-in period (treatment week 4). Good response to interferon was defined as a decrease in HCV RNA level of 1 log10 IU per milliliter or more after the lead-in period. For the primary analysis, the absolute difference between group 2 and group 1 was 37.4 percentage points (95% confidence interval [CI], 25.7 to 49.1; P<0,001), and between group 3 and group 1, 45.2 percentage points (95% CI, 33.7 to 56.8; P<0.001). For the secondary analysis, the absolute difference between group 2 and group 1 was 39.1 percentage points (95% CI, 27.2 to 51.0; P<0.001), and between group 3 and group 1, 45.1 percentage points (95% CI, 33.4 to 56.8; P<0.001). The P values were calculated with the use of the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test after adjustment for baseline stratification factors. I bars are 95% confidence intervals.

The rates of sustained virologic response among patients with prior relapse were 29% in group 1, versus 69% and 75% in group 2 and group 3, respectively; among patients with prior nonresponse, the corresponding rates were 7% versus 40% and 52%. A total of 102 patients (15%, 28%, and 27% in groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively) had a poor response to interferon, defined as a decrease in the HCV RNA level of less than 1 log10 IU per milliliter after the 4-week lead-in period (Fig. 2). In this subgroup, a sustained virologic response was achieved in none of the patients in group 1 and in 33% and 34% in groups 2 and 3, respectively. Among patients who had a good response to interferon (a decrease in HCV RNA level of 1 log10 IU per milliliter or more at treatment week 4), the rates of sustained virologic response were 25%, 73%, and 79% in group 1, group 2, and group 3, respectively.

An assessment for amino acid variants associated with reduced susceptibility to boceprevir was performed for 114 patients in group 2 or group 3 in whom a sustained virologic response did not occur. Postbaseline data were available for 98 of the 114 patients (86%), with variants detected in 43 of these 98 patients (44%). The rate of amino acid variants associated with reduced susceptibility to boceprevir was higher among patients with a poor response to interferon (13 of 46 [28%] in group 2 and 15 of 44 [34%] in group 3) than among patients with a good response to interferon (10 of 110 [9%] in group 2 and 7 of 112 [6%] in group 3).

In group 2, the duration of total therapy was based on a prespecified decision at treatment week 8, at which time patients with an undetectable HCV RNA level were eligible for a shorter period of therapy. The proportion of patients with an undetectable HCV RNA level at week 8 in the boceprevir groups (74 of 162 patients [46%] in group 2 and 84 of 161 patients [52%] in group 3) was approximately six times the proportion in group 1 (7 of 80 [9%]). Early response (i.e., an undetectable HCV RNA level at week 8) was associated with high rate of sustained virologic response in all three groups (7 of 7 patients [100%] in group 1; 64 of 74 patients [86%] in group 2; and 74 of 84 patients [88%] in group 3).

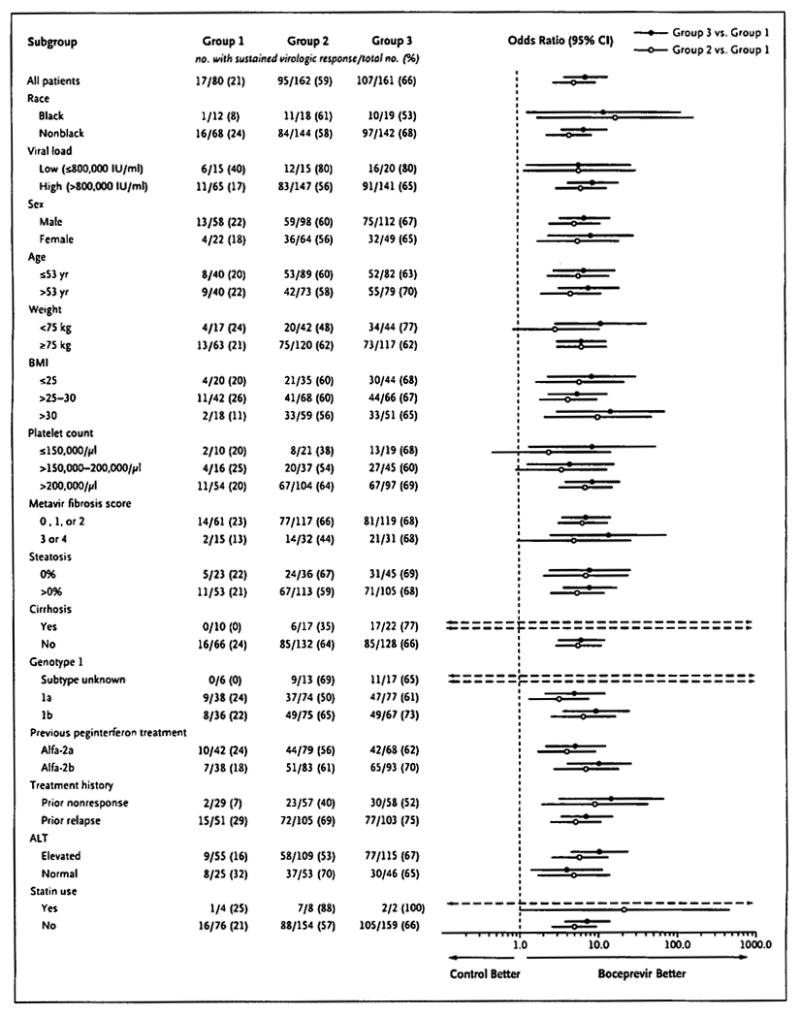

An evaluation of treatment effect according to subgroups of baseline characteristics showed that the numerical odds of a sustained virologic response was greater, across all subgroups, with either response-guided triple therapy (group 2) or 44-week triple therapy (group 3) than with the standard of care (group 1) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Odds Ratios for a Sustained Virologic Response in Group 2 versus Group 1 and Group 3 versus Group 1, According to Subgroup.

Odds ratios are shown for group 3 versus group 1 (solid circles) and group 2 versus group 1 (open circles) on a log10 scale. The dashed vertical line at unity indicates no difference between the two groups (odds ratio of 1). The dashed horizontal arrows indicate odds ratios and confidence intervals that exceed the x-axis scale. Race was self-reported. The body-mass index (BMI) is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters. For the Metavir fibrosis score, presence or absence of cirrhosis, and percent steatosis, a total of 28 patients (4 in group 1, 13 in group 2, and 11 in group 3) had missing data. Data on sustained virologic response for other subgroups are listed in Table S2 of the Supplementary Appendix. P values for the interaction between treatment group and baseline characteristic are given in Table 6 of the Supplementary Appendix. The HCV genotype 1 subtype was determined with the use of the Trugene assay (Bayer Diagnostics). ALT denotes alanine aminotransferase.

Although there was a sustained virologic response in 12 more patients in group 3 than in group 2, the rates in each group did not differ significantly (odds ratio of a sustained virologic response in group 3 vs. group 2,1.4; 95% confidence interval, 0.9 to 2.2). A similarly small difference was seen between these two groups during the period in which the therapy was identical (week 0 through treatment week 36), with 9 to 14 more patients having an undetectable HCV RNA level during treatment weeks 8 to 36 in group 3 than in group 2 (Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). In post hoc exploratory analyses, we observed that this difference appeared to be driven by patients with cirrhosis at baseline: the percentage of patients with cirrhosis who had an undetectable HCV RNA level at week 8 was 18% (3 of 17 patients) in group 2, versus 73% (16 of 22 patients) in group 3, despite identical treatment through this time point (Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). This suggests an underlying difference in responsiveness that is not fully accounted for by treatment-group randomization. In contrast, among patients without cirrhosis at baseline, the percentage with an undetectable HCV RNA level at week 8 was 50% (66 of 132 patients) in group 2 and 49% (63 of 128) in group 3. The odds of a sustained virologic response were similar between group 3 and group 2 for most baseline factors except for body weight under 75 kg, elevated alanine aminotransferase level, and cirrhosis, for which there was a greater odds of a sustained virologic response in group 3 (Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). In contrast, the odds of a sustained virologic response were not different for those with advanced fibrosis (a Metavir fibrosis score of 3 or 4), which is often preferentially used owing to the variability of biopsy readings.

Multivariable stepwise logistic-regression analysis served to identify five baseline factors that were significantly associated with achievement of a sustained virologic response: assignment to either boceprevir group rather than the control group (odds ratios for group 2 and group 3 vs. group 1, 7.3 and 10.7, respectively; P<0.001 for both comparisons), previous relapse (odds ratio vs. previous nonresponse, 3.1; P<0.001), low viral load at baseline (odds ratio vs. high load, 2.5; P=0.02), and absence of cirrhosis (odds ratio vs. presence, 2.1; P=0.04) (Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). When the decline in viral load (i.e., decrease from baseline in the HCV RNA level of ≥1.0 log10 IU per milliliter vs. <1.0 log10 IU per milliliter) at week 4 (was added to the model, the week 4 response was a stronger predictor of sustained virologic response than historical response (odds ratio, 5.2; P<0.001).

SAFETY

The study included a stopping rule whereby patients in whom an undetectable HCV RNA level was not achieved by treatment week 12 discontinued all therapy. The low rate of an undetectable HCV RNA level by treatment week 12 in group 1 resulted in 61% of patients discontinuing treatment for this reason, as compared with 22% and 18% of patients in group 2 and group 3, respectively (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). Thus, the median duration of treatment was 2.4 to 3.2 times longer in the boceprevir groups than in the control group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adverse Events, According to Treatment Group.*

| Event | Group 1 (N=80) | Group 2 (N = 162) | Group 3 (N = 161) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 2 vs. Group 1 | Group 3 vs. Group 1 | ||||

| Median duration of study-drug exposure — days | 104 | 252 | 336 | ||

| Death — no. (%) | 0 | 1 (<1) † | 0 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Any adverse event — no. (%) | 77 (96) | 160 (99) | 161 (100) | 0.34 | 0.04 |

| Discontinuation owing to adverse event — no. (%) | 2(2) | 13(8) | 20 (12) | 0.15 | 0.02 |

| Dose modification owing to adverse event — no. (%) | 11 (14) | 47 (29) | 53 (33) | 0.01 | 0.002 |

| Any life-threatening adverse event — no. (%) | 0 | 4(2) | 5(3) | 0.31 | 0.17 |

| Any serious adverse event — no. (%) | 4(5) | 16 (10) | 23 (14) | 0.23 | 0.03 |

| Hematologic event | |||||

| Reduced neutrophil count — no. (%) | |||||

| Grade 3: 500 to <750 per mm3 | 7(9) | 30 (19) | 32 (20) | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| Grade 4: <500 per mm3 | 3(4) | 10(6) | 11(7) | 0.55 | 0.40 |

| Mean change in hemoglobin from baseline — g/dl | |||||

| At wk 12 | −2.89 | −4.02 | −3.96 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| At wk 24 | −2.69 | −4.36 | −4.31 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| At wk 48 | −3.45 | −4.16 | −4.49 | 0.09 | 0.005 |

| Hemoglobin level — no. (%) | |||||

| Grade 2: 8.0 to <9.5 g/dl | 9(11) | 42 (26) | 41 (25) | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Grade 3: 6.5 to <8.0 g/dl | 1(1) | 5(3) | 12 (7) | 0.67 | 0.07 |

| Grade 4: <6.5 g/dl | 0 | 0 | 1(<1) | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Erythropoietin use | 17 (21) | 66 (41) | 74 (46) | 0.003 | <0.001 |

| Transfusion | 0 | 3(2) | 14(9) | 0.55 | 0.006 |

| Common adverse event — no. (%)‡ | |||||

| Anemia | 16 (20) | 70 (43) | 74 (46) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Dry skin | 6 (8) | 34 (21) | 36 (22) | 0.009 | 0.004 |

| Dysgeusia | 9 (11) | 69 (43) | 72 (45) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Rash | 4 (5) | 27 (17) | 22 (14) | 0.01 | 0.05 |

A listing of all life-threatening and serious adverse events can be found in Table S4 in the Supplementary Appendix. The P values presented are nominal, have not been adjusted for multiple comparisons, and are based on Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Student’s t-test for continuous variables.

There was one death by suicide in group 2, which occurred 18 weeks after the end of the study treatment and was considered to be unrelated to the study treatment.

Common adverse events were those classified as being related to a study treatment and occurring with an incidence of 15% or more in any group. Only common adverse events for which P<0.05 for a pairwise comparison with group 1 (group 3 vs. group 1 or group 2 vs. group 1) are shown. All other common adverse events (for which the treatment-related incidence was 15% or more in any group) can be found in Table S5 in the Supplementary Appendix.

In the boceprevir groups as compared with the control group, a greater proportion of patients reported serious adverse events and there were more discontinuations and dose modifications owing to adverse events. There was a higher incidence of anemia in the groups receiving boceprevir (43 to 46%) than in the control group (20%). Consistent with the increased incidence of anemia, the proportion of patients with hemoglobin levels of 6.5 to less than 9.5 g per deciliter was higher in groups 2 and 3 than in group 1; however, discontinuation owing to anemia was infrequent (occurring in 0% of patients group 1 and group 2 and in 3% [5 of 161 patients] in group 3). Erythropoietin was administered to 21%, 41%, and 46% of patients in groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Of the 403 patients, 17 received a transfusion for the management of anemia; 16 of these patients also received erythropoietin. Adverse events, dose modifications, and study-drug discontinuation in the 49 patients with cirrhosis are summarized in Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix.

The most common adverse events observed in all treatment groups were flulike symptoms that are typically reported in association with peginterferon–ribavirin therapy (Table S5 in the Supplementary Appendix). Dysgeusia, rash, and dry skin were reported more commonly in the boceprevir groups than in the control group.

DISCUSSION

Our data show that the addition of boceprevir to peginterferon–ribavirin therapy leads to high rates of sustained virologic response among patients in whom prior treatment had failed. Furthermore, patients who had previously had a relapse after receiving the standard of care had rates of sustained virologic response of up to 75%, with rates of 40 to 52% in the subgroup of patients with a previous nonresponse. Patients with undetectable HCV RNA levels at treatment week 8 were shown to have a rate of sustained virologic response that was similar whether boceprevir was taken for 32 weeks or 44 weeks; thus, an early response identified patients who could benefit from shorter treatment. There were no identified groups of patients with a previous treatment failure for whom the standard of care was more efficacious than was triple therapy. We observed high rates of a sustained virologic response among black patients and patients with advanced liver disease, who usually have a poor response,17,18 representing a clinically significant improvement over the standard of care.19

Rates of anemia were higher among patients receiving boceprevir-containing regimens than among those receiving control therapy, and many patients required erythropoietin treatment. Discontinuation for anemia was infrequent (affecting 3% of patients in group 3 only). Consistent with the increased incidence of anemia, a higher proportion of boceprevir recipients, as compared with controls, had a neutrophil count of 500 to less than 750 per cubic millimeter or underwent a red-cell transfusion.

This study included a 4-week lead-in period during which peginterferon–ribavirin was administered, which allowed for the assessment of the patient’s interferon responsiveness immediately before the addition of boceprevir. We have previously shown that a decline in viral load of less than 1 log10 IU per milliliter after 4 weeks of peginterferon–ribavirin therapy is significantly correlated to a decline of less than 2 log,10 IU per milliliter after 12 weeks of treatment.20 We identified 102 patients with a poor response to interferon, defined as a decrease in the HCV RNA level of less than 1 log,10 IU per milliliter at week 4. This is an important recognition of the changes that can evolve over time in patients who had previously been treated and are awaiting retreatment. Possible explanations for such changes include an increase in body weight, development of glucose intolerance, an increase in hepatic steatosis, and progression of fibrosis, all of which could have resulted in diminished responsiveness to peginterferon–ribavirin. Notably, a sustained virologic response was achieved, after boceprevir was added to the standard of care, in 33 to 34% of the patients with a poor response to interferon, as compared with 0% in the patients retreated with peginterferon–ribavirin alone.

In summary, the results of our phase 3 trial show that boceprevir, when added to peginterferon alfa-2b and ribavirin, leads to high rates of sustained virologic response in difficult-to-treat patients.

Acknowledgments

Funded by Schering-Plough [now Merck]; HCV RESPOND-2 ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00708500.

Sponsored by Schering-Plough (now part of Merck).

We thank all the patients, health care providers, and investigators involved in the study. Dr. Lisa Pedicone of Merck for her helpful advice and invaluable support, and Karyn Davis of Merck for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

The opinions expressed in this report represent the consensus of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the formal position of Merck or other institutions listed as authors’ affiliations.

References

- 1.Hepatitis C fact sheet. Geneva: World Health Organization; ( http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs164/en.) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoofnagle JH, Seeff LB. Peginterferon and ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2444–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct061675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feld JJ, Hoofnagle JH. Mechanism of action of interferon and ribavirin in treatment of hepatitis C. Nature. 2005;436:967–72. doi: 10.1038/nature04082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hofmann WP, Herrmann E, Sarrazin C, Zeuzem S. Ribavirin mode of action in chronic hepatitis C: from clinical use back to molecular mechanisms. Liver Int. 2008;28:1332–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hadziyannis SJ, Sette H, Jr, Morgan TR, et al. Peginterferon-alpha2a and ribavirin combination therapy in chronic hepatitis C: a randomized study of treatment duration and ribavirin dose. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:346–55. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-5-200403020-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeuzem S. Heterogeneous virologic response rates to interferon-based therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C: who responds less well? Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:370–81. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-5-200403020-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McHutchison JG, Lawitz EJ, Shiffman ML, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b or alfa-2a with ribavirin for treatment of hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:580–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berman K, Kwo PY. Boceprevir, an NS3 protease inhibitor of HCV. Clin Liver Dis. 2009;13:429–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mederacke I, Wedemeyer H, Manns MP. Boceprevir, an NS3 serine protease inhibitor of hepatitis C virus, for the treatment of HCV infection. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;10:181–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McHutchison JG, Everson GT, Gordon SC, et al. Telaprevir with peginterferon and ribavirin for chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1827–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806104. (Erratum. N Engl J Med 2009:361:1516.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McHutchison JG, Manns MP, Muir AJ, et al. Telaprevir for previously treated chronic HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1292–303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908014. (Erratum. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1647.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poordad F, McCone J, Jr, Bacon BR, et al. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1195–206. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Germer JJ, Majewski DW, Rosser M, et al. Evaluation of the TRUGENE HCV 5′NC genotyping kit with the new GeneLibrarian module 3.1.2 for genotyping of hepatitis C virus from clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:4855–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.10.4855-4857.2003. (Erratum. J Clin Microbiol 2004;42:3911.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobson IM, Brown RS, Jr, Freilich B, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b and weight-based or flat-dose ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C patients: a randomized trial. Hepatology. 2007;46:971–81. doi: 10.1002/hep.21932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.PegIntron (Peginterferon alfa-2b) product information. ( http://www.spfiles.com/pipeg-intron.pdf.)

- 16.Rebetol (ribavirin USP) prescribing information. ( http://www.spfiles.com/pirebetol.pdf.)

- 17.Muir AJ, Bornstein JD, Killenberg PG. Peginterferon alfa-2b and ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C in blacks and non-Hispanic whites. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2265–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032502. (Erratum. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1268.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heathcote EJ, Shiffman ML, Cooksley WG, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a in patients with chronic hepatitis C and cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1673–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012073432302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Negro F. Adverse effects of drugs in the treatment of viral hepatitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:183–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poordad F, Sulkowski M, McHutchison J, et al. High correlation between week 4 and week 12 as the definition for null response to peginterferon alfa (PEG) plus ribavirin (R) therapy: results from the IDEAL trial. Presented at the 61st annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; Boston. October 29–November 2, 2010. [Google Scholar]