Abstract

Reports from academic and media sources assert that many young people substitute non-vaginal sexual activities for vaginal intercourse in order to maintain what could be called “technical virginity.” Explanations for technical virginity, however, are based on weak empirical evidence and considerable speculation. Using a sample of 15–19-year-olds from Cycle 6 of the National Survey of Family Growth, we examine technical virginity and its motivations. The results suggest that religious adolescents are less likely than less-religious ones to opt for non-vaginal sex over total abstinence. Abstinence pledgers who are virgins are neither more nor less likely than nonpledgers who are virgins to substitute non-vaginal sex for intercourse. Moreover, religion and morality are actually the weakest motivators of sexual substitution among adolescents who have not had vaginal sex. Preserving technical virginity is instead more common among virgins who are driven by a desire to avoid potential life-altering consequences, like pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases.

Keywords: Technical virginity, sexual behavior, abstinence pledging, religiosity, oral sex, anal sex

Although oral sex and anal sex are far more common among those who also have vaginal intercourse, significant media and social scientific attention has been paid to those who abstain from vaginal sex while engaging in these other forms of sexual activity—a group dubbed “technical virgins” (Gagnon and Simon 1987; Gates and Sonenstein 2000; Woody et al. 2000). According to the USA Today and The New York Times, technical virginity is simply “part of teens’ equation” (Jayson 2005), and “many girls see [oral sex] as a means of avoiding pregnancy and of preserving their virginity” (Lewin 1997, p. 8). Social scientists report that about 10 percent of adolescent girls and 15 percent of adolescent boys are technical virgins, but the proportion decreases quickly with age, as rates of vaginal intercourse increase: Only about four percent of 20–24-year-olds have had oral or anal sex but not vaginal sex (Mosher, Chandra, and Jones 2005). There is little evidence that this practice of sexual substitution is anything new. In the early 1980s, about 15 percent of adolescent girls and 25 percent of adolescent boys had engaged in oral sex but not vaginal intercourse (Newcomer and Udry 1985).

Social scientists, though, have yet to offer compelling, empirically-based explanations for technical virginity. Assumptions about its source persist, however. According to many observers (including scholars and journalists), technical virgins engage in non-vaginal sexual activities to avoid “sinful” behavior or to “stay pure.” This idea has been fueled by the well-publicized finding that abstinence pledgers1 are more likely than nonpledgers to be technical virgins (Brückner and Bearman 2005). Among 18–25-year-olds, 13 percent of consistent pledgers are technical virgins, compared to just two percent of nonpledgers. From this study Brückner and Bearman (2005, p. 277) concluded that pledgers “who do not [have premarital sex] are more likely to substitute oral and/or anal sex for vaginal sex.” This finding was a media hit, and Bearman reiterated it on 60 Minutes. It may not be quite true as stated, however. Brückner and Bearman did not analyze a sample of young people who have not had premarital sex; they analyzed a sample of all young adults, irrespective of their virginity status. If a higher proportion of pledgers abstain from vaginal sex, which other evidence suggests (Bearman and Brückner 2001), then it may be that fewer of these virgin pledgers are substituting alternative forms of sex. In other words, the perceived penchant for technical virginity among abstinence pledgers (and, by extension, religious young people) may be attributable to the simple fact that more of them are virgins in general.

Other scholars suggest that technical virginity is less about maintaining virginity for its religious or moral implications and more about reducing risk to one’s “life chances” (Michels et al. 2005; Regnerus 2007). This explanation stresses that young people who have not had vaginal sex engage in non-vaginal sex to avoid life-altering consequences such as pregnancy or sexually transmitted diseases. As a result, technical virginity is most prevalent among those who envision a promising future for themselves, complete with a college education and good career, and not necessarily among those who morally object to intercourse.

Evidence for either of these explanations is scarce, and a large part of the little we know about technical virginity is taken from studies of college students and young adults—even though technical virginity is much more common among adolescents (Mosher, Chandra, and Jones 2005). This study, which uses a nationally-representative sample of American adolescents, has two primary goals. The first is to assess the claims of heightened technical virginity among religious adolescents and those who take abstinence pledges. The second is to understand adolescents’ expressed motivations for technical virginity. Before turning to these issues, however, we first discuss what we already know about technical virginity among American young people.

RELIGION, ABSTINENCE PLEDGING, AND TECHNICAL VIRGINITY

A common assumption about technical virginity has been that not a few religious young people substitute other forms of sex for vaginal sex, and do so in order to avoid violating religious teachings about nonmarital intercourse. Our empirical knowledge of the link between religion and technical virginity, however, is limited and in some cases has been misunderstood. For example, Brückner and Bearman’s (2005) finding from Wave III Add Health data that pledgers are more likely to be technical virgins than are nonpledgers has been misinterpreted (by an editorial in the same journal issue) to mean that abstinence pledgers—virgins or not—are more likely to have oral and anal sex. According to Fortenberry (2005, p. 270), “Pledgers are more likely to engage in non-vaginal oral-genital and anogenital sexual behaviors.”2 This claim has been disputed using the same Add Health data. In an unpublished conference paper, Rector and Johnson (2005) find significant differences between pledgers and nonpledgers, but it is those who pledge who are less likely to have had oral sex (63 vs. 73 percent) and anal sex (15 vs. 22 percent). The assertion that virgin pledgers are more likely to have had non-vaginal sex than virgins who have not pledged, however, remains unchallenged.

Brückner and Bearman’s finding is not the only piece of evidence to suggest technical virginity is religiously or morally motivated. Although college students (in the late 1970s) with high degrees of self-reported religiosity were less likely to engage in a wide variety of sexual behaviors, including oral sex, technical virgins were found disproportionately among the highly religious (Mahoney 1980). Moreover, a recent ethnography of Southern California youth notes that many self-proclaimed virgins engage in a variety of sexual behaviors, all the while expressing their commitment to “staying pure…because that’s what God calls [them] to do” (Clark 2004, p. 133).

This seemingly contradictory relationship between “purity” and non-vaginal sexual activity—if it does exist—could be the result of mixed definitions of “sex.” After all, only 40 percent of college students consider oral sex to be “sex” (Sanders and Reinisch 1999). Other studies find that number too high and suggest that almost all young people think that sex is only about penile penetration of the vagina (Clark 2004). Regardless of who is correct, the meaning of sex in America is ambiguous and contested (Bogart et al. 2000; Remez 2000).

How religious young people define “sex” is not well documented. One study of California ninth-graders finds that respondents are significantly more likely to oppose vaginal sex on religious grounds than they are oral sex (Halpern-Felsher et al. 2005). This distinction between sexual behaviors, however, is not likely emanating from religious teachings. Few religious organizations—including conservative or evangelical ones—make clear moral distinctions among vaginal sex, oral sex, and anal sex (Remez 2000). Indeed, in-depth interviews of adolescents suggest that the most common definition of sex among religiously conservative adolescents does include oral and anal sex (Regnerus 2007). As one respondent in that study articulates, “If it has the word sex in it, then it’s sex” (p. 167). There is likely more to the religion and technical virginity story than the ambiguous definition of sex.

Perceptions aside, religious young people and abstinence pledgers who have not had vaginal sex should theoretically be less likely to be technical virgins than their counterparts. Varying types and degrees of social embeddedness (such as in a religious community) influence the sexual script an individual follows (Ellingson et al. 2004). Further, institutional actors (like churches or pledging organizations) are key players that determine “the meaning systems and scripts that guide sexual behaviors and relationships” (Ellingson et al. 2004, p. 25). The degree to which these scripts are adopted by young people may also depend on the value accorded the institution that promotes it (Smith 2003). Thus we would expect at least some young people who are embedded in religious communities, who value their religious faith, and who pledge abstinence to adopt the sexual scripts advocated by religious institutions and pledging organizations.

The character of such religious sexual scripts, then, becomes important for our understanding of technical virginity. Do they include proscriptions of premarital, non-vaginal sexual activity? Some evidence indicates that they do. As noted above, religious organizations make no moral distinctions among different types of sexual activities (Remez 2000). True Love Waits, a prominent pledging organization founded by the Southern Baptist Convention, proclaims, “Until you are married, sexual purity means saying no to sexual intercourse, oral sex, and even sexual touching. It means saying no to a physical relationship that causes you to be ‘turned on’ sexually. It means not looking at pornography or pictures that feed sexual thoughts” (“FAQ about TLW” 2005).Of course, young people may choose not to adhere to these sexual scripts and opt for the more permissive scripts promoted by secular culture (especially adolescents who do not value their religious experience very much). As religious authority over sexual behavior continues to wane (Petersen and Donnenwerth 1997; Joyner and Laumann 2000; Ellingson 2004), this seems increasingly the case. And whether or not religious communities articulate proscriptions of non-vaginal sex as frequently and as clearly as they do proscriptions of vaginal sex is not well understood. Yet there is little theoretical basis to support claims of heightened technical virginity among highly religious virgins or abstinence pledgers.

RISK REDUCTION AND TECHNICAL VIRGINITY

Given the restrictive sexual scripts taught by religious communities and pledging organizations, some argue that technical virginity is less about avoiding sinful behavior and more about reducing pregnancy and STD risk. After all, adolescents consider oral sex much less risky than vaginal sex when it comes to contracting a sexually transmitted disease or getting (someone) pregnant (Halpern-Felsher et al. 2005). Regnerus (2007) concludes that the technical virginity phenomenon is evidence of a nascent “middle class morality,” which is neither about religion nor sexual abstinence but rather avoiding hindrances to future schooling plans and socioeconomic life chances. The average technical virgin has no moral objection to vaginal intercourse, he argues, and the phenomenon is noted more readily among mainline Protestant and Jewish adolescents—traditionally some of the least religious and most economically advantaged young people (Smith and Denton 2005; Pyle 2006). African-American adolescents, typically less economically advantaged than white youth, are seldom technical virgins. They instead tend to skip non-vaginal sexual behaviors and to prefer vaginal intercourse (Smith and Udry 1985; Regnerus 2007). Adolescents espousing this new middle class sexual script are generally not interested in remaining virgins per se (for moral reasons) but may nevertheless exhibit the pattern of behavior identified as technical virginity. Instead, they are interested in remaining free from the burden of pregnancy and the sorrows of STDs, so they trade the “higher” pleasures of actual intercourse for a set of low-risk substitutes: coupled oral sex, mutual masturbation, and solitary pornography use (and masturbation). They perceive a bright future for themselves: college, an advanced degree, a career, a family. Simply put, too much seems to be at stake. Sexual intercourse is not worth the risks. Intercourse, then, is suspended temporarily and replaced by lower risk alternatives.

If this theory of “middle class morality” is correct, we would expect technical virginity to be most common among young people with a high educational trajectory and low religiosity; their motivation for abstinence would be based not on religion or morality but on fear of pregnancy and STDs—outcomes that significantly hamper future health and socioeconomic prosperity. Technical virginity would be less about virginity maintenance (for reasons of “purity”) and more about risk-aversion. This study empirically evaluates these explanations for technical virginity—avoiding sin and reducing risk—using a nationally representative sample of 15–19-year-olds. In so doing, we ask and answer two questions: (1) Are religious adolescents and abstinence pledgers who have not had vaginal sex substituting other forms of sex at higher rates than are other virgins, and (2) what reasons motivate technical virgins to substitute non-vaginal sex for vaginal sex?

DATA

The data for this study come from Cycle 6 (2002) of the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG). The NSFG is a nationally representative survey of 12,571 women and men aged 15–44 and is focused on factors affecting pregnancy and birthrates, men’s and women’s health, and parenting. The survey was commissioned by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) and conducted by the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan. Funding was provided by eight programs and agencies of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, including the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The survey included detailed questions about a variety of sexual behaviors and also a brief assessment of the respondents’ religiosity.

The NSFG employed a multistage probability sampling design. At Stage 1, 121 primary sampling units (cities/counties) were selected from more than 2,400 around the U.S., including 11 Hispanic primary sampling units. At Stage 2, these primary sampling units were separated into blocks, which were subsequently divided into four domains by their racial composition. Blocks were then selected with probabilities proportionate to the estimated number of households in the block according to the 2000 census. Next (Stage 3), housing units were chosen from each block. Housing units within blocks with higher proportions of minorities (i.e., Hispanics and African-Americans) were chosen at higher rates to obtain an oversample of these groups. Lastly, in Stage 4 of the design, an eligible respondent from each housing unit was randomly selected and interviewed in his or her home by a trained female interviewer. Sensitive questions were administered using an audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) technique.

The NSFG obtained an overall response rate of 79 percent.3 When weights are applied (to account for unequal probability of selection), the NSFG can be treated as a nationally representative survey of U.S. women and men aged 15–44. For this study, we restrict our sample to unmarried 15–19-year-olds (N = 2,226). Following listwise deletion of missing values, our sample size is 2,158. Our sample of virgins contains 1,040 young people. For more information about Cycle 6 of the NSFG, see Groves et al. (2005).

MEASURES

Dependent Variables

The first dependent variable for this study is a classification of American young people based on their heterosexual behavior. Our four-category typology is constructed from the following yes/no questions posed by NSFG:

“Ha[ve/s] [you/a male] ever put [your/his] penis in [a female’s/your] vagina (also known as vaginal intercourse)?”

“Have you ever put your mouth on a [female’s vagina/man’s penis] (also known as oral sex or [cunnilingus/fellatio])?” and “Has a [female/male] ever put [her/his] mouth on your [penis/vagina] (also known as oral sex or [fellatio/cunnilingus])?”

“Ha[ve/s] [you/a male] ever put [your/his] penis in [a female’s/your] rectum or butt (also known as anal sex)?”

Based on responses to these questions, we classify respondents in the following way:

Technical virgins: Respondents who answered “yes” to at least one of the oral sex questions or the anal sex question but “no” to the vaginal sex question are labeled “technical virgins.”

Total abstainers: Respondents who answered “no” to all of the questions listed above are referred to as “total abstainers.”

Mixed sexual practicers: Respondents who said they had had vaginal sex and one of the other types of sex are considered “mixed sexual practicers.”

Sexual traditionalists: Respondents who answered “yes” to the vaginal sex question but “no” to the other questions are termed “sexual traditionalists.”

For our analyses of the virgin sample, our dependent variable is simply a measure of whether or not the respondent has had oral or anal sex.

Key Independent Variables

Our key independent variables assess the respondents’ level of religiosity, their identification with the abstinence pledge movement, and virgins’ motivations for remaining abstinent. The first religion measure, religious service attendance, taps an individual’s involvement in a moral community and that individual’s level of public religiosity. Religious service attendance is typically a good measure of religiosity because it requires a certain level of (repeated or continued) religious commitment on the part of the respondent. To gauge this facet of religiosity, NSFG asked respondents, “About how often do you attend religious services?” Five response categories were offered: “never,” “less than once a month,” “1–3 times a month,” “once a week,” and “more than once a week.” We created binary variables for each of these responses.

Religion is multidimensional, however, and a measure of religious service attendance does not fully capture levels of religious influence. Public religiosity and private religiosity each independently affect vaginal sexual behavior, even after controlling for the other (Nonnemaker, McNeely, and Blum 2003). To gauge this private aspect of religiosity, interviewers asked, “Currently, how important is religion in your daily life? Would you say it is very important, somewhat important, or not very important?” As with the attendance variable, we created dummy variables for each of these response categories.4

The NSFG also includes a measure of pledging status. Respondents were asked, “[Did you ever take/Have you ever taken] a public or written pledge to remain a virgin until marriage?” Respondents who answered yes are coded 1; those indicating they did not pledge are coded 0.

We also consider respondents’ motivations for maintaining virginity (i.e., abstinence from vaginal sex). NSFG probed the primary motivation for abstinence among virgins with the following question: “As you know, some people have had sexual intercourse by your age and others have not…What would you say is the most important reason why you have not had sexual intercourse up to now?” Respondents had six responses from which to choose: “against religion or morals,” “don’t want to get [a female] pregnant,” “don’t want to get a sexually transmitted disease,” “haven’t found the right person yet,” “in a relationship, but waiting for the right time,” and “other.”5

Control Variables

Sexual behavior, religion, and pledging are known to vary by sociodemographic variables. For this reason, we include a set of control variables in our multivariate analyses. Age and gender (1=female) are accounted for, as are race (reference group=white), urbanicity (reference group=lives in MSA, central city), family structure (1=intact), and living environment (1=living with parents). As a measure of socioeconomic status, we include dummy variables to tap the educational attainment of the respondents’ parents. Respondents either had no parent (reference group), one parent, or two parents with a college degree. Respondents with only one parent are categorized in either the no parent or two parent group, based on the educational attainment of that one parent. For descriptive statistics of all variables, see the Appendix.

Appendix.

Weighted Means, Ranges, and Standard Deviations of Measures

| Variables | Mean (SD),Full Samplea | Mean (SD),Virgin Sampleb | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Has had oral and/or anal sex only | .12 (.32) | — | 0,1 |

| Has had vaginal plus oral and/or anal sex | .43 (.50) | — | 0,1 |

| Has had vaginal sex only | .06 (.24) | — | 0,1 |

| Has had no type of sex | .39 (.49) | — | 0,1 |

| Has had oral sex | — | .23 (.42) | 0,1 |

| Has had anal sex | — | .01 (.08) | 0,1 |

| Has had oral and/or anal sex | — | .23 (.42) | 0,1 |

| Never attends religious services | .24 (.43) | — | 0,1 |

| Attends religious services less than once a month | .22 (.42) | — | 0,1 |

| Attends religious service 1–3 times a month | .17 (.37) | — | 0,1 |

| Attends religious services once a week | .23 (.42) | — | 0,1 |

| Attends religious services more than once a week | .13 (.34) | — | 0,1 |

| Religion not important | .23 (.42) | — | 0,1 |

| Religion somewhat important | .38 (.49) | — | 0,1 |

| Religion very important | .39 (.49) | — | 0,1 |

| Pledged abstinence | .12 (.33) | — | 0,1 |

| Abstained for religious or moral reasons | — | .36 (.48) | 0,1 |

| Abstained for fear of pregnancy | — | .20 (.40) | 0,1 |

| Abstained for fear of STD | — | .08 (.27) | 0,1 |

| Abstained to wait for right person | — | .20 (.40) | 0,1 |

| Abstained to wait for right time | — | .06 (.23) | 0,1 |

| Age | 17.05 (1.41) | 16.56 (1.34) | 15–19 |

| Female | .48 (.50) | .48 (.50) | 0,1 |

| White | .64 (.48) | .67 (.47) | 0,1 |

| African-American | .15 (.36) | .11 (.31) | 0,1 |

| Hispanic | .16 (.36) | .16 (.36) | 0,1 |

| Other race | .06 (.23) | .07 (.25) | 0,1 |

| Lives in MSA, central city | .51 (.50) | .57 (.50) | 0,1 |

| Lives in MSA, not central city | .28 (.45) | .24 (.43) | 0,1 |

| Does not live in MSA | .20 (.40) | .20 (.40) | 0,1 |

| Intact, two-parent family | .57 (.49) | .66 (.48) | 0,1 |

| Lives with parent(s) | .49 (.50) | .61 (.49) | 0,1 |

| No parent has college degree | .62 (.49) | .56 (.50) | 0,1 |

| One parent has college degree | .21 (.41) | .23 (.42) | 0,1 |

| Two parents (or only parent) have college degree | .17 (.38) | .22 (.41) | 0,1 |

N = 2,158

N = 1,040

ANALYTIC APPROACH

We begin by providing simple statistics that reveal the general prevalence of different types of sexual activity—broken down by religious and pledging characteristics—among young Americans ages 15–19. We then display the percentage of virgin respondents who engage in each type of non-vaginal sexual activity. Next, we employ multinomial logit modeling to evaluate religious and pledging effects on different types of sexual behavior, net of possible confounding effects.

Second, we determine technical virgins’ motivations for abstinence from vaginal sex. We first report the primary motivation for abstinence among all virgins in the sample and among technical virgins in the sample. We subsequently display the prevalence of sexual activity among virgins by their motivation for abstinence. Finally, we use a logit regression model to evaluate how these motivations predict technical virginity.

In order to accommodate the multiple design weights that accompany NSFG data, we generate all analyses using “svy” estimators in Stata, which account for the strata, the primary sampling unit, and the unequal probability of being included in the sample (StataCorp 2006).

RESULTS

Religion, Pledging, and Technical Virginity

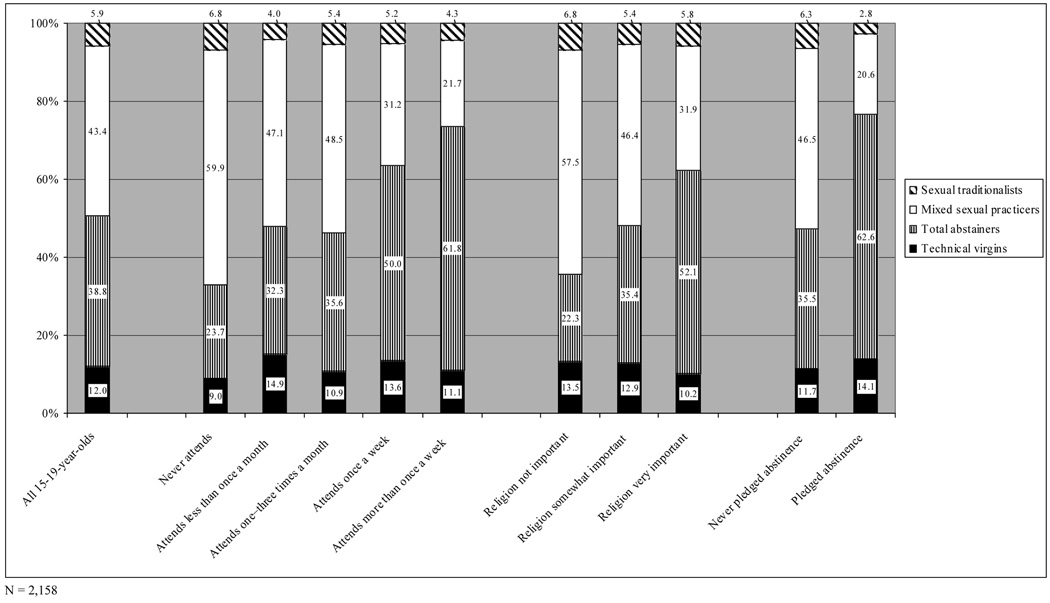

Figure 1 displays the percentage of unmarried young people who fall into each type of sexual classification. To begin, technical virgins are a small minority of American adolescents. Only about 12 percent of adolescents have had only oral and/or anal sex. By contrast, nearly two fifths of American young people have abstained from all types of sex. The plurality of 15–19- year-olds—just over 43 percent—have had both oral and/or anal sex and vaginal sex. Those who have had vaginal sex are likely to have also had another type of sex: Only six percent of young people are sexual traditionalists.

Figure 1.

Sexual Classification of Unmarried 15–19-Year-Olds (in percent), by Religious Service Attendance, Importance of Religion, and Pledging Status

Participation in types of sexual behavior varies widely by religiosity measures, though the prevalence of technical virginity does not fluctuate much between the more and less religious. With respect to church attendance, there is no clear pattern of technical virginity. Although technical virginity is fairly stable across different levels of church attendance, total abstinence increases dramatically among adolescents who attend services more often, and mixed sexual practice decreases substantially. The pattern is somewhat similar when it comes to religious salience. Technical virginity appears, if anything, to decrease slightly with increased religious salience, but total abstinence climbs from just 22 percent among those who say religion is not important to more than half of those who say religion is very important. Similar decreases in mixed sexual practice accompany these rising rates of total abstinence.

The difference between abstinence pledgers and those who do not pledge is slight when it comes to technical virginity. About 14 percent of pledgers have oral and/or anal sex only, compared to just over 12 percent of nonpledgers. As we saw with the religiosity measures, however, this slight increase in technical virginity is accompanied by a drastic increase in total abstinence among pledgers. Nearly two thirds of abstinence pledgers are total abstainers, compared to just over one third of nonpledgers. This high prevalence of total abstinence is reflected by low levels of mixed sexual practice. Only about 21 percent of pledgers have had both vaginal sex and oral or anal sex, compared to 47 percent of nonpledgers.

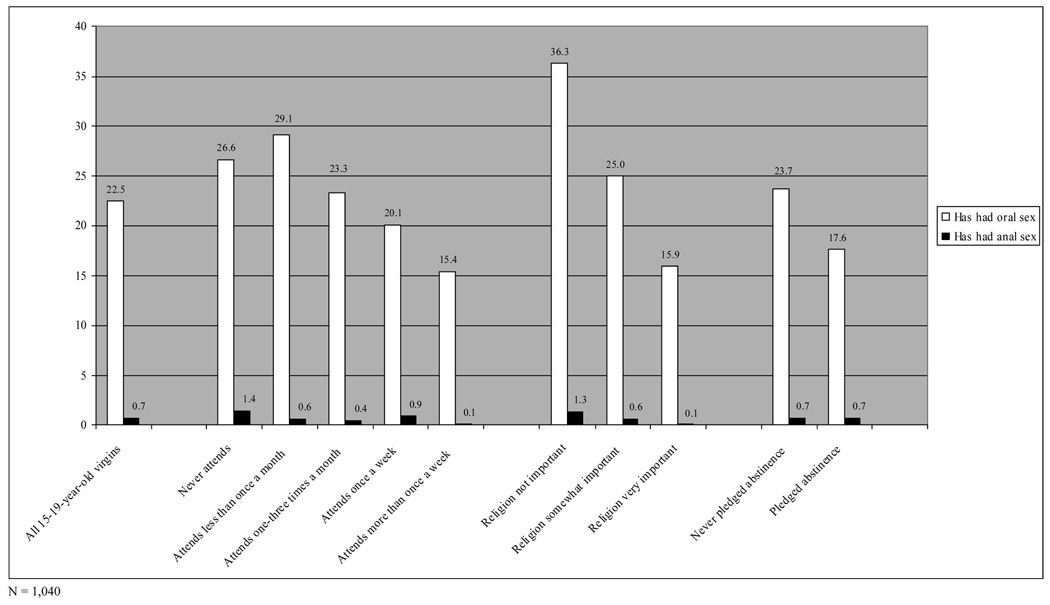

Figure 1 suggests that technical virginity—substituting oral or anal sex for vaginal sex—is not affected much by adolescents’ religiosity or pledging status. However, total abstinence is much more common among these individuals. Given this higher level of abstinence from vaginal sex, it is unlikely that technical virginity is more common among religious and pledging virgins. Indeed, Figure 2 indicates that this is the case. Whereas nearly 30 percent of virgin young people who attend church never or less than once a month have had oral sex, only about 23 percent of semi-regular attenders, 20 percent of weekly attenders, and 15 percent of more-than-weekly attenders have done the same. The disparity is even more pronounced when differences in religious salience are considered. About 16 percent of virgins who say religion is very important to them have had oral sex, compared to 36 percent of those who say religion is not important.

Figure 2.

Percent of 15–19-Year-Old Virgins Who Have Had Oral and Anal Sex, by Religious Service Attendance, Importance of Religion, and Pledging Status

Virgin pledgers are also less likely than virgin nonpledgers to have had oral sex: Only 18 percent of virgins who have pledged to remain abstinent until marriage opt to have oral sex, compared to 24 percent of virgins who do not pledge. This difference, however, is not nearly as pronounced as it is between the religiosity categories.

Oral sex is not the only type of sexual behavior that young people can substitute for vaginal intercourse, but it is apparently a more preferred option than anal sex. Less than one percent of virgins report having had anal sex. Anal sex is less common among the religious and does not appear to vary much by pledging status, but its occurrence is so rare that conclusions can hardly be drawn. Anal sex is just not an appealing alternative to vaginal sex in the eyes of adolescent virgins.

To ensure that these relationships are not actually explained by some other characteristic (e.g., age, family characteristics), we turn to multivariate analysis. Table 1 displays relative risk ratios from a multinomial logit regression model predicting adolescents’ sexual classification, and these results largely confirm the relationships seen in Figure 2. The first column of Table 1 reveals that more religious young people do not tend to be technical virgins as opposed to total abstainers. Adolescents who claim that religion is somewhat important to them are almost half as likely to be technical virgins as those who say religion is not important at all. Those claiming religion is very important in their lives are nearly 70 percent less likely. Although their does appear to be a positive (yet statistically insignificant) effect of church attendance on technical virginity, this association is reversed when the religious salience variables are dropped from the model (results not shown). Pledgers, on the other hand, are neither more nor less likely than nonpledgers to opt for technical virginity over total abstinence.

Table 1.

Relative Risk Ratios from Multinomial Logit Regression Model Predicting Sexual Classification among Unmarried 15–19-Year-Olds

| Comparison | Technical virgins vs. total abstainers | Technical virgins vs. mixed sexual practicers | Technical virgins vs. sexual traditionalists | Total abstainers vs. mixed sexual practicers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religious Service Attendance | ||||

| Less than once a month | 1.66+ | 2.29** | 2.35* | 1.38 |

| One–three times a month | 1.49 | 1.52 | 2.25+ | 1.02 |

| Once a week | 1.56 | 2.59* | 2.73* | 1.66* |

| More than once a week | 1.15 | 3.29** | 2.30+ | 2.85*** |

| Importance of Religion | ||||

| Somewhat important | .53* | .83 | .88 | 1.57* |

| Very important | .28*** | .90 | .86 | 3.21*** |

| Pledging Status | ||||

| Pledged abstinence | .84 | 1.91+ | 2.09 | 2.27** |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | 1.36*** | .70*** | .83 | .52*** |

| Female | .97 | .83 | .75 | .86 |

| African-American | 1.15 | .58* | .15*** | .50** |

| Hispanic | .73 | .85 | .29** | 1.16 |

| Other race | .60 | 1.17 | .24+ | 1.93* |

| Lives in MSA, not central city | .97 | .78 | .65 | .80 |

| Does not live in MSA | 1.40 | .98 | .60 | .70* |

| Intact, two-parent family | 1.37 | 1.56+ | 1.19 | 1.15 |

| Lives with parent(s) | .81 | 1.53+ | 1.67 | 1.89** |

| One parent has college degree | 1.08 | 1.06 | 2.82** | .99 |

| Two parents (or only parent) have college degree | 1.68* | 2.28** | 4.74** | 1.36+ |

| Model Fit Statistics | ||||

| −2 log likelihood | 4,189.09 | |||

| Pseudo R-square | .16 | |||

| N | 2,158 |

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001 (two-tailed test)

Technical virgins = Has had oral and/or anal sex only; N = 259

Total abstainers = Has had no type of sex; N = 837

Mixed sexual practicers = Has had both vaginal and oral and/or anal sex; N = 935

Sexual traditionalists = Has had vaginal sex only; N = 127

Reference group for religious service attendance = Never

Reference group for importance of religion = Not important

Reference group for race = White

Reference group for urbanicity = Lives in MSA, central city

Reference group for parents’ educational attainment = No parent has college degree

The second and third columns of Table 1 show why religious adolescents and pledgers appear just as likely—or even more likely—to be technical virgins in Figure 1. When technical virgins are compared to those who have oral or anal sex and vaginal sex, young people who attend church more frequently are much more likely to opt for technical virginity. Pledgers are nearly twice as likely as nonpledgers to be technical virgins than mixed sexual practicers. Religious service attendance also appears to be a significant determinant of technical virginity versus sexual traditionalism.

The fourth column of Table 1 indicates that technical virginity certainly does not account for religious and pledging influences on abstinence among adolescents. Adolescents who attend church regularly are far more likely to be a total abstainer than a mixed sexual practicer. So are those who consider religion somewhat or very important in there lives. Pledgers are more than twice as likely to remain abstinent from all forms of sex as to engage in mixed sexual behaviors.

The findings thus far call into question the claims that religious young people and abstinence pledgers who do not have vaginal sex are more likely to engage in other sexual activities. Interestingly, the relative risk ratios in Table 1 indicate that technical virginity is more common among those with more educated parents—those with higher educational trajectories themselves—which hints that sexual substitution may indeed be more about educational and career trajectory than about religion or virginity maintenance. To more clearly determine what motivates technical virginity, we next consider adolescents’ expressed primary motivation for abstinence from vaginal sex.

Motivations for Technical Virginity

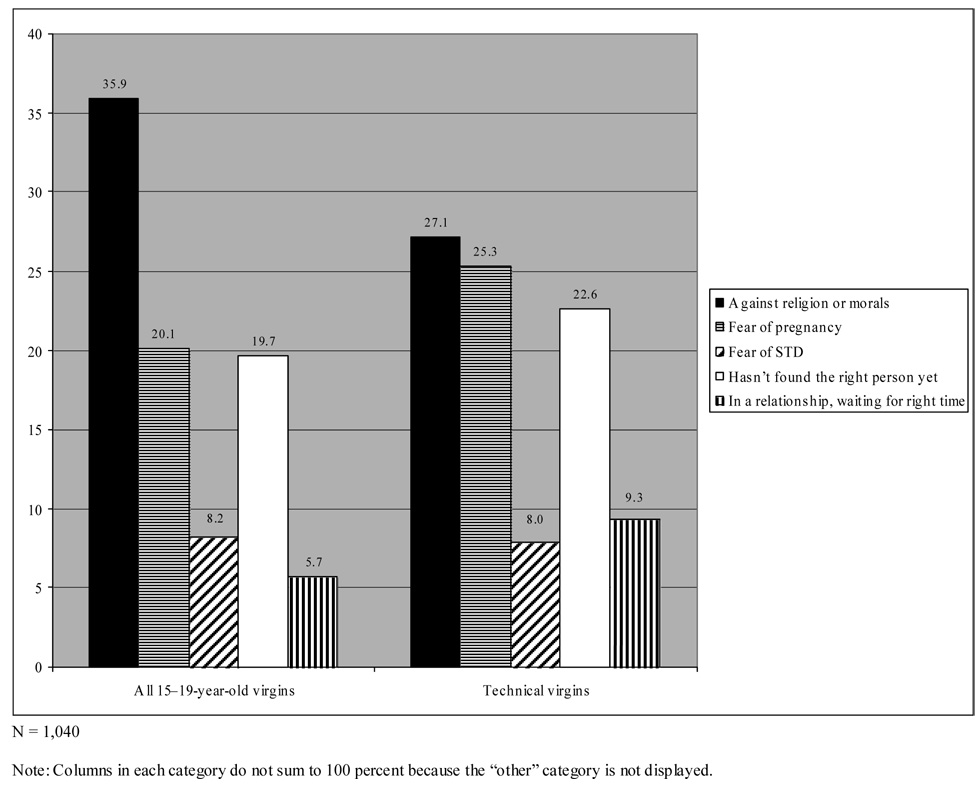

Figure 3 reveals the primary motivation for abstinence among virgins, first among all virgins and then among virgins who have had oral and/or anal sex. Virgins tend to fall into one of three major categories: religious abstainers, risk-reducing abstainers (those who are trying to avoid pregnancy and STDs), and virgins who are waiting for the right time or person to come along. A plurality of virgins—36 percent—abstain from vaginal sex for religious or moral reasons. Fear of pregnancy and STDs motivates about 28 percent of virgins to abstain, and another 25 percent are waiting to have sex until the right time or until they meet the right person. When we consider technical virgins (those who have engaged in non-vaginal sexual behaviors), we find that religious virgins are not as numerous as they are in the overall virgin sample. Religious abstainers account for about 27 percent of all technical virgins. Those who fear pregnancy are overrepresented among technical virgins at 25 percent, compared to their representation among virgins overall (about 20 percent). Virgins who are fearful of STDs make up about eight percent of the technical virgins, which is comparable to their representation in the full sample. Abstainers who are waiting for the right time or person make up 32 percent of the virgins who have had oral and/or anal sex; like the risk-reducing technical virgins, these individuals are overrepresented among virgins having non-vaginal sex.

Figure 3.

Primary Motivation for Abstinence among 15–19-Year -Old Virgins (in percent), Among All Virgins and Technical Virgins

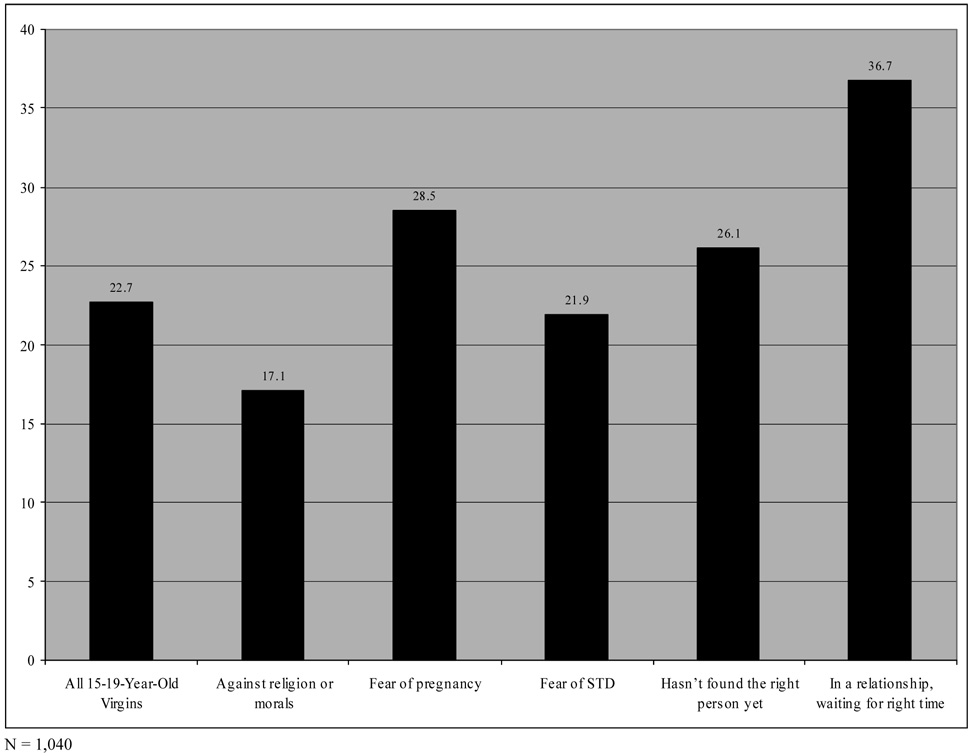

Figure 3 shows that religious abstainers make up a smaller proportion of technical virgins than of virgins overall. In contrast, risk-reducing abstainers and those waiting for the right time or person account for a larger proportion of technical virgins than would be expected from the overall numbers. So which virgins are most likely to be technical virgins? Figure 4 presents the prevalence of non-vaginal sexual behavior among virgins, broken down by their primary motivation for abstinence. If religion is not actually restricting technical virginity (or if it is actually encouraging the behavior), we would expect those who abstain for religious reasons to engage in oral sex at rates similar to or higher than those who abstain for other reasons. But this is not the case. As Figure 4 demonstrates (and Figure 3 intimated), religious abstainers are the least prone to engage in oral and/or anal sex. Only 17 percent do so, compared to 37 percent of those waiting for the right time, 29 percent of those who fear pregnancy, 26 percent of young people who haven’t found the right person, and 22 percent of those who fear STDs. Simply put, people who abstain from vaginal sex for explicitly religious reasons do appear to refrain from oral and anal sex at higher rates than other virgins.

Figure 4.

Percent of 15–19-Year-Old Virgins Who Are Technical Virgins, by Primary Motivation for Abstinence

Table 2 presents odds ratios from a logit regression model predicting oral and/or anal sex among virgins. The bivariate associations in Table 6 remain significant in multivariate analysis. Those who abstain for religious reasons (the suppressed reference group) are less likely to have had oral or anal sex than all other virgins. These findings, using a more proximate measure of motivation for technical virginity, suggest that religion does indeed have a restricting influence on technical virginity, net of demographic characteristics. The results also suggest that sexual substitution is most prevalent among virgins seeking to reduce risk and those waiting for the right time or person, not among those attempting to “stay pure.”

Table 2.

Odds Ratios from Logit Regression Model Predicting Technical Virginity among 15–19-Year-Old Virgins

| Has had oral and/or anal sex | |

|---|---|

| Primary Motivation for Abstinence | |

| Fear of pregnancy | 2.44*** |

| Fear of STD | 2.24+ |

| Hasn’t found the right person yet | 1.74* |

| In a relationship, waiting for right time | 3.63*** |

| Demographics | |

| Age | 1.36*** |

| Female | 1.07 |

| African-American | .69 |

| Hispanic | .59* |

| Other race | .43 |

| Lives in MSA, not central city | 1.07 |

| Does not live in MSA | 1.22 |

| Intact, two-parent family | 1.35 |

| Lives with parent(s) | .81 |

| One parent has college degree | 1.12 |

| Two parents (or only parent) have college degree | 1.97** |

| Model Fit Statistics | |

| −2 log likelihood | 1,033.15 |

| Pseudo R-square | .07 |

| N | 1,040 |

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001 (two-tailed tests)

Notes: Models contain but do not display a control for “other” motivation for abstinence.

Reference group for primary motivation for abstinence = Against religion or morals

Reference group for race = White

Reference group for urbanicity = Lives in MSA, central city

Reference group for parents’ educational attainment = No parent has college degree

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

We began by asking two questions: (1) Are religious young people and abstinence pledgers who have not had vaginal sex substituting other forms of sex at higher rates than are other virgins, and (2) what reasons motivate those who choose to do this? Our analyses suggest that the answer to this first question is “no,” despite scholarly reports to the contrary (Mahoney 1980; Brückner and Bearman 2005). Religious adolescents who have not had vaginal sex are actually less likely to substitute non-vaginal forms of sex for vaginal intercourse. When we compare virgin pledgers to virgin nonpledgers, we find that abstinence pledgers who do not have premarital sex are neither more nor less likely than their counterparts to have oral or anal sex. Thus claims of heightened sexual substitution among these individuals are unfounded.6

The implications of these findings for abstinence-only education are not straightforward. On one hand, abstinence pledging is not entirely ineffective, especially during adolescence. It certainly does not contribute to an increase in non-vaginal sexual behaviors. Nearly two thirds of 15–19-year-old pledgers are totally abstinent—thereby avoiding pregnancy and STD risk—while only about one third of nonpledgers are. Simply put, religious and moral motivations can and do influence sexual decision-making among American adolescents. On the other hand, religious and moral motivations are not a “silver bullet” when it comes to eradicating STDs and teenage pregnancy, as Fortenberry (2005) suggests. From a public health perspective, abstinence-only programs such as pledging may be incomplete, and policymakers should consider more comprehensive programs. But scholars would also be wise to respect the religiously-based moral framework from which most of these pledging programs operate. Among many (religious) Americans, physical health is considered secondary to religious and spiritual health.

Having addressed previous assertions about religious young people, abstinence pledging, and technical virginity, we set out to determine what actually motivates technical virginity. We find that there are three common motivations: (1) adhering to religious or moral teachings about vaginal sex, (2) reducing the risk of pregnancy or STD acquisition, and (3) waiting for the right time or the right person before having vaginal intercourse.

Even though religion is a weak motivation for sexual substitution, plenty of religious technical virgins do exist (because there are plenty of religious virgins). More than a quarter of technical virgins seem motivated by religious or moral principles. These individuals may very well view technical virginity as a means of conforming to cultural sexual scripts while not violating religious teachings on vaginal sex. But the majority of religious adolescents who have not yet had vaginal sex stick to their religious sexual scripts, which do seem to include proscriptions of premarital, non-vaginal sexual behavior (Remez 2000).

Yet those who adhere to a religious sexual script often do so not simply because of their social embeddedness in a religious community, though this helps. Rather, it is strong personal faith and the internalization of a religious sexual script7 that leads to the avoidance of non-vaginal sexual behaviors (in addition to the avoidance of vaginal sex). The threat of running afoul of one’s church and community often fails to deter adolescents from technical virginity, although it does seem to help curb the occurrence of vaginal sex. It appears that premarital non-vaginal sex is not as stigmatized within religious communities as premarital vaginal sex, despite what any official organizational stance may be.

The second group of technical virgins is those who avoid vaginal intercourse because of the risks it poses to their health, well-being, and future plans. This rationale—risk-reduction—appears to be the most compelling motivation for technical virginity among young people who have not had vaginal sex. Technical virginity is most common among these individuals who are driven by a desire to avoid pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases. Much is at stake for these individuals. They are more likely to come from homes with educated parents and are subsequently more likely to attend (or are already attending) a four-year college. For these, vaginal sex involves too much risk—it could incur damage to their educational and career trajectories, and thus it is replaced for a time by lower-risk alternatives such as oral sex. Their behavior is reflective not of their religious morality, but of their desire to live up to the expectations of their family’s socioeconomic status (Regnerus 2007).

Although many technical virgins are motivated by religion and by risk-reduction, many others have simply embraced a sexual script that defines non-vaginal sexual activities as stepping stones on the path to the pinnacle of intimacy (per their script), vaginal intercourse. These individuals are “technical virgins” by definition, but their technical virginity is less about strategic planning and more about selectiveness and the progression of intimacy. Indeed, this group of technical virgins—about one third of all technical virgins—should hardly be considered technical virgins at all. They have not substituted for vaginal sex; they just have not gotten around to it yet. These adolescents are waiting for the right time and person to come along before taking that final step, or “going all the way.” Calculated technical virginity, then, is even rarer than it first appears.

Limitations

There are always limitations when using cross-sectional data, not the least of which is our inability to measure religiosity and abstinence pledging prior to sexual activity in the first part of our analysis. Brückner and Bearman (2005) find that 11 percent of abstinence pledgers are “secondary virgins”—that is, they had vaginal intercourse before they pledged abstinence and were promising to remain abstinent from that point forward. If this is the case, pledging effects will be underestimated in this study. If, however, people engage in sexual activity and then curb their religiosity8 or forget their pledge, as some pledgers are known to do (Rosenbaum 2006), our results could be overestimations. Nevertheless, we are not primarily interested in identifying antecedents of technical virginity but are instead concerned with understanding the contemporary prevalence of technical virginity among subgroups of young Americans and their expressed motivation for the behavior. Furthermore, we are interested in technical virginity during adolescence (when it is most popular), and the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health includes data on oral sex only in its third wave, when respondents were young adults.

Social desirability may also be a factor outside our control. Abstinence pledgers may be more prone to conceal instances of intercourse that they consider experimental or no longer in line with their current behavior (Rosenbaum 2006). This is a limitation to which all survey research on sensitive behaviors is subject.

Finally, technical virginity may well be some sort of rational, calculated decision made by young people. But alternative explanations for the phenomenon may also be valid. Some of these individuals may very well wish that they had remained totally abstinent; adolescents sometimes regret their sexual activity after it has taken place (Regnerus 2007). Some young people may get “caught up in the moment,” feel pressure to have oral sex, or have it forced upon them. Or perhaps oral sex is the only option presented to them by their partner. Still further, they may simply prefer the idea of oral sex to vaginal sex.

Conclusions

This study has evaluated the claims that religious young people and abstinence pledgers who have not had vaginal sex are more likely to engage in other sexual activities. Additionally, we have sought to understand young people’s motivations for technical virginity. We conclude that technical virginity does not vary among the more or less religious and those who sign or do not sign abstinence pledges because virginity is more common among religious adolescents and abstinence pledgers. Among virgins, however, religious young people and abstinence pledgers, if anything, are less likely to have oral and/or anal sex. So while many religious adolescents and abstinence pledgers who have not had vaginal sex are at risk for acquiring STDs by virtue of their sexual substitution, technical virginity is not more pronounced among these individuals.

Reducing risk is the most compelling motivation for technical virginity. Young people who avoid vaginal sex because they fear pregnancy or sexually transmitted diseases are more likely than religious abstainers to engage in non-vaginal sexual activities. Yet there are still a large number of religious technical virgins, because more virgins are motivated by religion than by anything else.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The first and third authors were supported by a research grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R03-HD048899-01, Mark Regnerus, PI).

The abstinence pledge movement consists of over one hundred loosely connected groups. Many of these groups are religious, and they endorse a variety of reasons to abstain from sex until marriage, including what they perceive to be the “failure” of contraceptives, the “horrors” of (untreated) STDs, the importance of giving your spouse the “gift” of virginity, and biblical teachings about sexual morality. Secularized pledging organizations, which emphasize that abstinence is the only foolproof way to avoid pregnancy and STDs, have also been developed as a tool for disseminating abstinence-only sex education in public schools. More than 2.5 million adolescents have taken an abstinence pledge (Bearman and Brückner 2001).

This misinterpretation was promulgated by a variety of media outlets, including 60 Minutes, The Today Show and Real Time with Bill Maher. For a more complete list, see Rector and Johnson (2005).

This response rate was calculated using the AAPOR double sampling computation method, which does not reflect unequal probabilities of selection within phases.

Individuals who indicated that they had “no religion” on a previous question (about religious affiliation) were skipped out of this question. Rather than lose more than 800 (nonrandom) cases, we code these respondents as 1 (“not important”).

This variable also appears as a dependent variable in Figure 3.

We argue that the differences between our findings and others result from differences in conceptualization (i.e., analyzing technical virginity among virgins only). But there are other differences that might contribute to the contradictory findings. Most notably, our sample is of 15–19-year-olds, while Brückner and Bearman’s is of 18–25-year-olds. We performed analyses in NSFG using 18–25-year-olds and found a similar story to the one we present here. About 14 percent of young adults who attend church more than once a week are technical virgins, compared to just five percent of those who never attend church. Among virgins, however, there is no difference between the more and less religious with respect to technical virginity. The pledge question was asked only of 15–19-year-olds, so we could not ascertain differences by pledging status for this age group. Nevertheless, we are confident that the difference is not attributable to our sample. Differences could also arise from measurements of non-vaginal sexual activity. The Brückner and Bearman measure of oral sex is of sexual activity in the last six or seven years, while ours is a measure of whether the respondent has ever had oral (or anal) sex. Though there is no way to tell the effect that this measurement discrepancy has on the outcomes of the studies, we suspect it is minimal.

Indeed, 57 percent of virgins who report that religion is very important to them abstain from sex primarily for religious or moral reasons.

Adolescents do not reduce their religiousness after engaging in vaginal sex (Hardy and Raffaelli 2003; Meier 2003), but the effects of non-vaginal sex on subsequent religiosity are not known.

REFERENCES

- Bearman Peter S, Brückner Hannah. Promising the Future: Virginity Pledges and First Intercourse. American Journal of Sociology. 2001;106:859–912. [Google Scholar]

- Bogart Laura M, Cecil Heather, Wagstaff David A, Pinkerton Steven D, Abramson Paul R. Is it ‘Sex’?: College Students’ Interpretations of Sexual Behavior Terminology. The Journal of Sex Research. 2000;37:108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Brückner Hannah, Bearman Peter S. After the Promise: The STD Consequences of Adolescent Virginity Pledges. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;36:271–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark Chap. Hurt: Inside the World of Today’ s Teenagers. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran John K, Chamlin Mitchell B, Beeghley Leonard, Fenwick Melissa. Religion, Religiosity, and Nonmarital Sexual Conduct: An Application of Reference Group Theory. Sociological Inquiry. 2004;74:102–127. [Google Scholar]

- Ellingson Stephen. Constructing Causal Stories and Moral Boundaries: Institutional Approaches to Sexual Problems. In: Laumann Edward O, Ellingson Stephen, Mahay Jenna, Paik Anthony, Youm Yoosik., editors. The Sexual Organization of the City. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2004. pp. 283–308. [Google Scholar]

- Ellingson Stephen, Laumann Edward O, Paik Anthony, Mahay Jenna. The Theory of Sex Markets. In: Laumann Edward O, Ellingson Stephen, Mahay Jenna, Paik Anthony, Youm Yoosik., editors. The Sexual Organization of the City. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2004. pp. 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- FAQ about TLW. 2005 Retrieved August 31, 2006 ( http://www.lifeway.com/tlw/faq/).

- Fortenberry Dennis J. The Limits of Abstinence-Only in Preventing Sexually Transmitted Infections. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;36:269–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates Gary J, Sonenstein Freya L. Heterosexual Genital Sexual Activity among Adolescent Males: 1988 and 1995. Family Planning Perspectives. 2000;32:295–297. 304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves Robert M, Benson Grant, Mosher William D, Rosenbaum Jennifer, Granda Peter, Axinn William, Lepkowski James, Chandra Anjani. Plan and Operation of Cycle 6 of the National Survey of Family Growth. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Vital and Health Statistics. 2005;42 [PubMed]

- Halpern-Felsher Bonnie L, Cornell Jodi L, Kropp Rhonda Y, Tschann Jeanne M. Oral Versus Vaginal Sex among Adolescents: Perceptions, Attitudes, and Behavior. Pediatrics. 2005;115:845–851. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy Sam A, Raffaelli Marcela. Adolescent Religiosity and Sexuality: An Investigation of Reciprocal Influences. Journal of Adolescence. 2003;26:731–739. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayson Sharon. Technical Virginity Becomes Part of Teens’ Equation. USA Today. 2005 October 19; Retrieved August 31, 2006 ( http://www.usatoday.com/news/health/2005-10-19-teens-technical-virginity_x.htm).

- Joyner Kara, Laumann Edward O. Teenage Sex and the Sexual Revolution. In: Laumann Edward O, Michael Robert T., editors. Sex, Love, and Health in America: Private Choices and Public Consequences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2000. pp. 41–71. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin Tamar. Teen-Agers Alter Sexual Practices, Thinking Risks Will Be Avoided. The New York Times. 1997 April 5;:8. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney ER. Religiosity and Sexual Behavior among Heterosexual College Students. The Journal of Sex Research. 1980;16:97–113. [Google Scholar]

- Meier Ann M. Adolescents’ Transition to First Intercourse, Religiosity, and Attitudes about Sex. Social Forces. 2003;81:1031–1052. [Google Scholar]

- Michels Tricia M, Kropp Rhonda Y, Eyre Stephen L, Halpern-Felsher Bonnie L. Initiating Sexual Experiences: How Do Young Adolescents Make Decisions Regarding Early Sexual Activity? Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2005;15:583–607. [Google Scholar]

- Mosher William D, Chandra Anjani, Jones Jo. Sexual Behavior and Selected Health Measures: Men and Women 15–44 Years of Age, United States, 2002. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; Advance Data from Vital Health Statistics. 2005;362 [PubMed]

- Newcomer Susan F, Udry J. Richard. Oral Sex in an Adolescent Population. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1985;14:41–46. doi: 10.1007/BF01541351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonnemaker James M, McNeely Clea A, Blum Robert Wm. Public and Private Domains of Religiosity and Adolescent Health Risk Behaviors: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;57:2049–2054. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen Larry R, Donnenwerth Gregory V. Secularization and the Influence of Religion on Beliefs about Premarital Sex. Social Forces. 1997;75:1071–1089. [Google Scholar]

- Pyle Ralph E. Trends in Religious Stratification: Have Religious Group Socioeconomic Distinctions Declined in Recent Decades? Sociology of Religion. 2006;67:61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Rector Robert, Johnson Kirk A. Adolescent Virginity Pledges and Risky Sexual Behaviors; Paper presented at the National Welfare and Evaluation Conference of the Administration for Children and Families; Washington, DC. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Regnerus Mark D. Forbidden Fruit: Sex and Religion in the Lives of American Teenagers. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Remez Lisa. Oral Sex among Adolescents: Is It Sex or Is It Abstinence? Family Planning Perspectives. 2000;32:298–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum Janet. Reborn a Virgin: Adolescents’ Retracting of Virginity Pledges and Sexual Histories. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1098–1103. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.063305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders Stephanie A, Reinisch June Machover. Would You Say You ‘Had Sex’ If…. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;281:275–277. [Google Scholar]

- Smith Christian. Theorizing Religious Effects among American Adolescents. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2003;42:17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Smith Christian. Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. Melinda Lundquist Denton. [Google Scholar]

- Smith Edward A, Udry J. Richard. Coital and Non-Coital Sexual Behavior of White and Black Adolescents. American Journal of Public Health. 1985;75:1200–1203. doi: 10.2105/ajph.75.10.1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 9.1. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Steensland Brian, Park Jerry, Regnerus Mark, Robinson Lynn, Wilcox Bradford, Woodberry Robert. The Measure of American Religion: Toward Improving the State of the Art. Social Forces. 2000;79:291–318. [Google Scholar]

- Woody Jane D, Russel Robin, D’Souza Henry J, Woody Jennifer K. Adolescent Non-Coital Sexual Activity: Comparisons of Virgins and Non-Virgins. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy. 2000;25:261–268. [Google Scholar]