1 Discovery of brugian filariasis in Japan

A tiny islet named Hachijo-Koshima was known as the only one focus of brugian filariasis in Japan. It is located about 300 km south to Tokyo in the Pacific Ocean. It had been rather hard to access due to the lack of the regular transportation system. The island was visited for the first time after the last World War II by the medical doctors for the investigation of the nature of a debilitating disease annoying much the inhabitants for long years there. They were Dr. Manabu Sasa, Associate Professor of Medical Zoology, Institute of Infectious Diseases, University of Tokyo and Dr. Rokuro Kano, Senior Assistant in the same department at that time. During their short stay of two days, July 3 to 4, 1948 they took blood thick smear samples from 17 school children and 22 adults at night from 9 to 12 pm. Microfilariae were detected in 3 cases of school children and 4 cases of adults. Thus the disease named as “Baku” by the natives was reconfirmed to be a filariasis. However, at that time the microfilariae were not carefully observed and they were granted to be of Wuchereria bancrofti, as it had been the only one species of filaria known prevailing widely through Japan.

Two years later in May, 1950, Sasa and Kano revisited the island accompanied with two new members; Shigeo Hayashi, M.D., a junior assistant and Koji Sato, V.D., a research fellow. During the 3 weeks’ stay in the island they made night blood smear examinations, investigated the clinical manifestations and also carried out selective chemotherapy to the detected microfilaria carriers with diethylcarbamazine citrate (Supatonin®). The mosquito fauna of the island was also carefully investigated. The blood smears were brought back to the laboratory in the institute for a more detailed morphological examination. The microfilariae from the carriers in Hachijo-Koshima were all identified as of Brugia malayi (Brug, 1927). The detail of the survey was reported by Hayashi S, Sasa M, Kano R, and Sato K. (1951) [1]. This was the first record of brugian filariasis in Japan.

2 Identification of microfilaria

The general appearance of the microfilaria is quite characteristic having a jagged outline, smaller size, and thickly packed nuclear column. It is different from bancroftian microfilaria which is larger in size, and has smoother outline and neatly arranged nuclear column. More careful observation would reveal two or three tail nuclei locating at the end of tail apart from main nuclear column. The measurements of fixed points were made with 20 microfilariae. A stochastic analysis clearly indicated they were significantly different from those of bancroftian type and identical with those of malayan type as being described by Feng L.C. (1933) [2]. The application of a special staining using Methylgreen and Pyronin dyes was so useful to differentiate special structure and/or cells; such as excretory pore, excretory cell, G1 to G4 cells and anal pore [3]. As to malayan microfilaria it has a longer cephalic space, bigger excretory and anal pore. Excretory cell is located far behind the excretory pore in contrast to bancroftian type in which the excretory cell is closely attaching to the excretory pore. The malayan microfilaria has much bigger G1 and its G2 is situated in the middle between G1 and anal pore. In bancroftian type G2 to G4 usually gather and closely located near anal pore. A special note for preparing Methylgreen-Pyronin staining solution was made in the reference [3].

3 Clinical manifestations

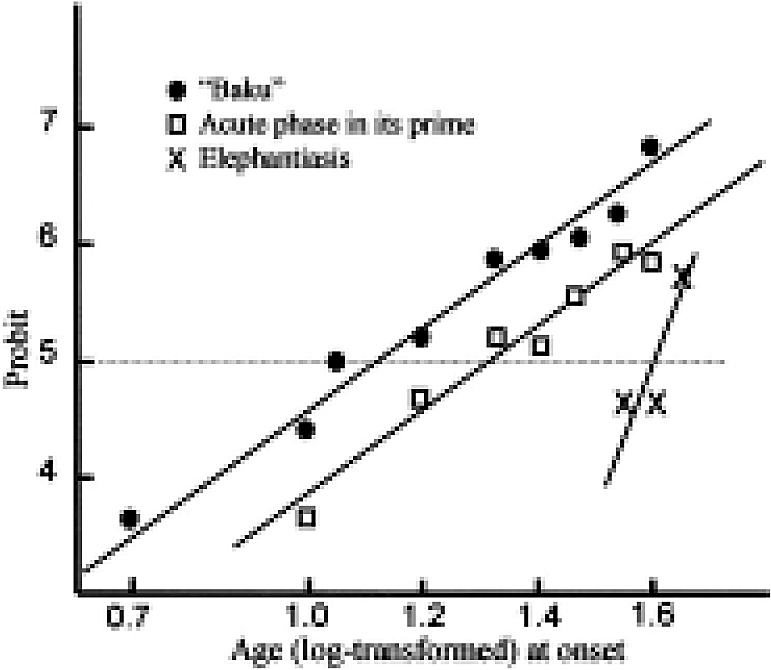

The disease called by the native inhabitants as “Baku” used to begin with an appearance of one or two skin eruptions of various sizes from a hen egg to a hand palm. It occurred either on the upper or lower extremities. It used to be accompanied with a string of induration of connecting lymph duct beneath the skin and occasionally with an indurated regional lymph node. The skin eruption would cause some itch but usually no pain. Lymphatic complications could be felt hard but usually not sore. The most annoying complication was the fever attack of around 40°C. The fever would last for a few days to a week. This enforced the people to stay in bed even while they were so busy in field work of cultivation or in fishing on the sea. Usually the people realized the initiation of this disease “Baku” in their life by the first appearance of skin eruption. The frequent attacks of fever would develop in the following acute phase. In the height of acute phase the edematous swelling of arm or leg would occur. It would subside in due time, however after frequent swelling the skin turned to be thick and hard. It would not shrink any more, developing into chronic phase of elephantiasis. In differing from elephantiasis in bancroftian filariasis, that of malayan filariasis used to be confined to the distal part of extremities and never became over double the normal size in thickness. It needs to be noticed that in malayan filariasis of Hachijo-Koshima Island no hydrocele or chyluria cases were ever observed. According to a careful retrospective enquiry for ever experienced suffering of “Baku” with the natives of island, Hayashi reported that the average age for the initiation of “Baku” was 13 years, ranging from 5 to 41 years of age. The average age for the acute phase in its prime was 21 years, ranging from 10 to 43 years, then the average age for the onset of elephantiasis was 39 years, ranging from 31 to 47 years (Fig. 1). This indicated that the disease took a long time course to develop. From the initiation of the disease in young age, 7 or 8 years more were required to proceed to the height of acute phase, and further nearly 20 years were needed to reach the last chronic stage, elephantiasis [1, 3, 4].

Fig. 1.

Estimation of the age at onset for “Baku”, acute phase in its prime and elephantiasis. Age distributions of these symptoms show the normal distribution when the ages are log-transformed.

4 Epidemiology

4.1 Distribution

In spite of intensive and extensive surveys for the existence of malayan filariasis, inspired by the first discovery in Hachijo-Koshima in fact the carriers of malayan type microflariae were detected only in four localities so far. One was Toriuchi Village in Hachijo-Koshima and another was a village named Utsuki which was located in the opposite side of the same island Hachijo-Koshima. The third was Hachijo main island, much bigger than Hachijo-Koshima. Two islands are separated each other by a sea channel of only 4 km wide. The fourth was Shikine Island which is located about 100 km north to Hachijo Island. Two microfilaria carriers of malayan type were detected in Hachijo Island, however all of them were revealed to be the recent immigrants from the Toriuchi Village in Hachijo-Koshima. In Hachijo Island the bancroftian filariasis had been long prevailing but it seemed to be incorrect to include this in the endemic area of Malayan filariasis. In Shikine Island, only a single microfilaria positive case of malayan type was detected. Its origin was unknown. However, it also seemed rather difficult to designate it as an endemic focus of malayan filariasis. Utsuki Village, situated on Hachijo-Koshima is absolutely isolated from Toriuchi Village and the survey in 1950 revealed only one malayan microfilaria positive case among 20 examinees. The natives of Utsuki Village claimed that they had been suffering so much from “Baku” in the past but it seemed declining in recent years. In conclusion Toriuchi Village in Hachijo-Koshima was actually proper to be designated the only one focus of malayan filariasis in Japan [5, 6].

4.2 Microfilaraemia positive rate

The first detailed report on the epidemiological features of malayan filariasis in Hachijo-Koshima Island appeared in the paper by Hayashi et al. (1951) [1]. The night blood examinations of 85 inhabitants revealed 29 (34.1%) positives. No difference in the positive rate was observed between the sexes. The youngest positive was a child of 6 years. The rate in 6-10 year age class was already 40% and it reached to 72.7% in 31-40 year age class, thereafter the rate became gradually lower according to the increase in age.

5 Vector mosquitoes

Hachijo-Koshima is an islet of oval shape, about 3 square km in size having a longer diameter of 3 km and a shorter diameter of 1.5 km. It looks as if the summit of a steep mountain projected on the surface of ocean, being surrounded by rocky cliffs. There were no plain fields good for rice paddy and no swamps or ponds, therefore no suitable habitats for anopheline and Mansonia mosquitoes, well known as proper vectors of malayan filariasis. The survey of mosquito fauna of the island indicated only 6 species, namely Aedes togoi, Aedes albopictus, Aedes flavopictus, Culex pipiens pallens, Culex (Lutzia) volax and Armigeres subalbatus. Each house of the inhabitants provided with a concrete water reservoir which gathered rainwater. These had been the essential water source of the people for daily use, but they were also forming the most suitable breeding places for Aedes togoi.

The indoor collections of mosquito at the houses of patients were intensively made. The catches were composed exclusively of Aedes togoi, mostly well engorged females. Naturally developed infective third stage larvae of Brugia malayi were detected from these mosquitoes as reported in reference 3. This was the first record that Aedes togoi, an Aedes mosquito belonging to the subgenus Stegomyia is serving as a natural vector of malayan filariasis. Aedes togoi was also breeding abundantly in rock pools in the beach. A trial of experimental infection of Culex pipiens pallens was made by Hayashi [3, 4]. Some infective larvae were found to be developed in mosquitoes when dissection was done 13-18 days after feeding on a microfilaraemia positive patient. It showed that Culex pipiens pallens is a potential vector of malayan filariasis. However, Aedes togoi was, in fact, acting the main vector of malayan filariasis in Hachijo-Koshima.

6 Treatment

Diethylcarbamazine hydrochloride was first introduced by Hewitt et al. (1947) as an effective chemical against cotton rat filaria. Its effect against human bancroftian filariasis was verified for the first time by Stevenson et al. (1948). In May, 1950 the chemical, provided by Tanabe Pharmaceutical Company in a form of diethylcarbamazine citrate (Supatonin®), was applied to treat patients in Hachijo-Koshima. This was the first trial in the world to treat human malayan filariasis. 26 patients were subjected to oral administration of Supatonin® at a dosage of 6 mg per kg of body weight (B.W.) per day (2 mg × 3) in consecutive 6 days. Due to some severe untoward reactions the full compliance could not be achieved. The reexaminations of blood after 10 days of administration showed that all 6 cases, who took the drug in a total amount of more than 26.7 mg/kg B.W., turned to negative, 7 (70%) among 10 cases who took 1.8-6.0 mg/kg B.W. converted to negative, but 4 cases who did not take the drug still remained positive. The other cases could not be reexamined. The major side effects were fever attack, headache, nausea and/or vomiting, with occasional skin eruptions. The patients claimed that the doctors from Tokyo did not treat them, instead brought them “Baku”. However, all these side effects subsided in several days even when they continued taking the drug [1, 3, 4].

7 Control

A series of frequent mass chemotherapy using Supatonin® were carried out on a schedule to treat all detected microfilaria positive cases at a dosage of 6 mg/kg B.W. per day in consecutive 12 days (making it to reach 72 mg/kg in total). The village was visited one or two times a year from May, 1950 until Oct., 1958. Although not all the cases received the full course of administration, the microfilaria positive rate tended to gradual declining with a considerable fluctuation. The rate before treatment in May 1950 was 31.5% (29/92), which reduced to 16.2% (12/74) in Sept. 1950, followed by the figures 20.8% in Aug. 1951, 16.4% in May 1952, 22.4% in Sept. 1952, 33.3% in Aug. 1956, 28.8% in Nov. 1956, 23.3% in July 1958 and 9.5% in Oct. 1958. During 4 years between Sept. 1952 to Aug. 1956, the village was left unvisited. It might explain the resurgence of positive cases.

Meanwhile vector control was also made using the residual spraying of DDT in houses and/or cowsheds, and DDT spray into rock pools in the beach. Introduction of small fish (gold fish and/or killifish) was made into the concrete water reservoir at each house. In fact the trials of vector control were made occasionally and did not necessarily cover the whole village; still these seemed to contribute to the success of control to some extent. In 1963 Hayashi and his colleagues revisited the village and found 14 positives among 85 examinees (16.5%). They gave an intensive chemotherapy with Supatonin® to all positive cases under strict supervision of the doctors. In addition all the houses were sprayed with phenitrothion (an antimosquito chemical). Five years later in 1968 when a team revisited the village the total population of 68 persons were found completely free of microfilariae. Three years later in 1971 Hachijo-Koshima Island was entirely evacuated due to its inconvenience for human life. Thus there is practically no more focus of Malayan filariasis in Japan [5, 6].

This is a success story of complete eradication of an endemic disease in a certain locality. As to the experience in Hachijo-Koshima we could not concentrate enough effort to carry out more intensive chemotherapy. This was our regret, nevertheless we have to notice a success of some extent resulted. In fact for a real success of control in a term of longer period, more simple and more cost-effective measure has to be developed. The appearance of new drug like as ivermectin and the combination of this with diethylcarbainazine would provide promising measures in combat against human lymphatic filariasis.

Acknowledgement

My deepest gratitude is to Dr. Manabu Sasa who has been an excellent leader in the research, survey and control works for human filariasis in Japan. His kind guidance introduced me into the field of filariasis control. I would like to express my sincere thanks also to all my colleagues for their excellent collaboration and kind support.

This paper is revised from Asian Parasitology Vol. 3 Filariasis in Asia and Western Pacific Islands, 105-108 by The Federation of Asian Parasitologists in 2004.

References

- 1.Hayashi S, Sasa M, Kano R, Sato K.Studies on filariasis in Hachijo-Kosima Island (2). Nissin Igaku 1951; 38: 19-22 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feng LC. Comparative study of the anatomy of Microfilaria malayi Brug, 1927 and Microfilaria bancrofti Cobbold 1877. Chin Med J 1933; 47: 1214-1246 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayashi S. Studies on filariasis malayi and bancrofti in Japan. Jpn J Med Zool (suppl. For commemorating Dr. Harujiro Kobayashi) 1954; 41-53 (in Japanese).

- 4.Sasa M, Hayashi S, Kano R, Sato K, Komine I, Ishii S. Studies on filariasis due to Wuchereria malayi (Brug, 1927) discovered from Hachijo-Kosima Island, Japan. Jpn J Exp Med 1952; 22: 357-390 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sasa M, Hayashi S, Sato K, lkeshoji T, Tanaka H. A review of field experiments in the control of bancroftian and malayan filariasis in Japan, 1968. Jpn J Exp Med 1959; 29: 369-405 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sasa M.Brugia malayi in Japan. ln: Sasa M. Human Filariasis. University of Tokyo Press, 1976: 494-498.