Abstract

Local protein synthesis is a prominent feature of developing axons, where it has critical roles in regulating the morphological plasticity of growth cones. Recent studies have identified specific mRNAs that are translated in growth cones in response to specific extracellular signals. In this review, we discuss the functional relevance of axonal protein translation for developing axons, the differences in translational capacity between developing and mature vertebrate axons, and possible pathways governing the specific translational activation of axonal mRNAs.

Keywords: mRNA, RNA-binding proteins, microRNAs, posttranscriptional regulation, axons

1. Introduction

Work over the last three decades has established the existence of protein translation machinery and mRNAs in axons of both vertebrates and invertebrates [for a review see 1]. However, while dendritic protein translation is generally accepted [2], axonal protein translation in vertebrates has remained somewhat controversial. This difference might be explained, in part, by early work in the mature nervous system that appeared to show a lack of protein translation machinery in axons [3]. In contrast, more recent studies indicate that, during development, axons contain mRNAs and ribosomes. Here, we discuss the differences in translational capacity between developing and mature vertebrate axons. We also address emerging signaling pathways that regulate translation in developing axons. But first, we focus on the phenomenon of local translation in neurons and other cell types, and potential rationales for its occurrence in developing axons.

2. The role of local protein synthesis in developing axons

While axonal protein translation in developing axons is an intensively studied phenomenon [4–9], its purpose and function is far less clear. Often, it is argued that the extreme distance between the soma and the tips of axons, along with the slow rate of transport of proteins from the soma to axons make local protein synthesis in axons necessary [e. g. 10]. In this view, local translation is understood simply as a means to overcome the slow anterograde transport from the cell body and to maintain the axoplasmic mass [10]. However, several lines of evidence are inconsistent with this idea. For example, the degree to which local translation is utilized is not proportional to axon length. Indeed, elongating developing axons utilize local translation [4,6–9] during pathfinding processes when they are intermediate in length [e.g. 11], but they do not rely on local translation when they are at their longest, i.e., when they have reached their target and formed synapses [12]. Furthermore, the argument of distance and slow transport should apply indiscriminately to all axonal proteins that have to be transported from the cell body by the slow transport mechanism, yet not all axonal proteins are locally translated. In fact, very few mRNAs have been definitively identified to be locally translated in developing vertebrate axons, including β-actin [13], β-tubulin [14], κ opioid receptor [15,16], ADF [17], RhoA [6], and cofilin [18]. A cDNA library from dorsal root ganglia axon mRNA identified only around 100 distinct mRNAs (unpublished result, L.J. Cox, U. Hengst, and S.R. Jaffrey). Thus, the majority of axonal proteins appear to be translated in the cell body and not the axon. This challenges the view of local translation as being necessary for maintaining the protein composition in the growth cone.

The fact that only a small fraction of axonal proteins are locally synthesized suggests that these proteins possess some unique properties or have certain roles that necessitate local synthesis. The identification of several axonally-translated proteins [6,8,9,16] suggests some of these properties. These proteins have roles in enabling the rapid morphological plasticity of growth cones in response to extracellular signals. The repulsive axon guidance cue Semaphorin3A induces the rapid local translation of RhoA in developing rat dorsal root ganglion growth cones causing growth cone collapse and axonal retraction [6,19]. The local translation of RhoA, a critical upstream regulator of the cytoskeleton, may enable the growth cone to respond to cues in the environment in a dynamic and spatially-precise manner that is required for axon guidance. For example, signals that activate translation may result in rapid changes in protein levels since their cognate mRNAs are present in ribosome-rich neural granules which appear to be mobilized in response to translation-inducing signals [20]. The pronounced and rapid growth cone collapsing effect of Sema3A reflects, in part, its ability to rapidly increase in RhoA protein levels in growth cones [6]. Thus, local translation may have a role in augmenting the function of proteins whose effects are magnified by rapid increases in their levels.

A related role for local translation may be to precisely regulate the appearance of proteins that are needed in a temporally-specific manner. For example, an EphA2 reporter mRNA is rapidly translated upon crossing the spinal cord midline [11]. Although this study did not examine the presence or expression of endogenous axonal EphA2 mRNAs, the ability of the midline to induce the reporter transcript raises the possibility that the corresponding endogenous mRNA is translated in order to participate in guidance events that occur distal to the midline.

Local protein synthesis may result in the localization of newly-synthesized proteins in growth cones with a degree of spatial specificity that might not be achieved by motor-based transport. An example is the asymmetric translation of β actin, which is associated with netrin-1-induced [9] and Ca2+-dependent [8] growth cone turning. Interestingly, the majority of axonal β-actin protein is anterogradely transported from the cell body into the axons [21]. Cell body derived β-actin might be used for the maintenance of the cytoskeleton or the general forward movement of axons [22], while locally, asymmetrically translated β-actin deposited at precise sites within growth cones is used to define the directionality of turning [8,9]. Thus, local translation facilitates the enrichment of β-actin at specific locations within the growth cone. Microtubule-dependent transport [23] of β-actin might be insufficient to transport it to the actin-rich edges and filopodia of a growth cone with the precision required for turning events. However, asymmetric activation of preexisting β-actin mRNA-containing polyribosome appears to be sufficient to generate a rapid increase in protein levels with spatial precision.

Data in migrating fibroblasts suggests that the same mechanism of local, asymmetrical β-actin translation is used there as well to confer directionality [24]. In this case, it is clear that local protein translation would not be utilized to overcome any distance problem, but instead is likely to reflect intrinsic requirements of directional cellular migration. Local translation at the leading edge, like in growth cones, may permit precise accumulation of specific proteins along lamellipodia or filopodia of the migrating fibroblast, and may permit rapid increases in protein levels in response to specific stimuli. The growth cone has obvious morphological similarities to the leading edge, and indeed, many proteins that are involved in cellular migration have been found to have a role in growth cone guidance [25]. Thus, local protein translation in developing axons may fundamentally reflect the need for local translation in the process of directional migration. The reduced translational capacity of mature axons may reflect the inability of these axons to migrate, in addition to the reduced need for axonal pathfinding and other developmental processes.

3. Changes in translational capacity during axonal maturation

A striking feature of vertebrate axons is that ribosomes and mRNA are present during axonal development and are significantly reduced or are not present in axons of the mature nervous system [3]. Axons undergo several stages in their development: during development, axons are rapidly growing with a growth cone at their tip that is directed by extracellular guidance cues to its target. Once it reaches its synaptic target, the axon undergoes a profound transition from a highly motile structure to an essentially static axon bearing the presynaptic terminal. Since most electron microscopic studies were performed on sections from the mature nervous system [3], vertebrate axons were considered to lack the capacity for local protein synthesis. This contrasted with studies in mature invertebrate neurons which appeared to have axonal mRNAs [1 and references therein]. However, invertebrates do not develop morphologically and functionally distinct dendrites and axons; instead their neurons possess only one type of neurite, confusingly termed an axon [26]. Therefore, it is difficult to extrapolate from studies of protein synthesis in axons of invertebrates [27] and in Aplysia neurites [28], to the existence of axonal protein synthesis in mature vertebrate axons [29].

The demonstration of the synthesis of β-tubulin, β-actin, and other proteins in axons of sympathetic neurons of newborn rats [14], and subsequent studies demonstrating a functional requirement for protein synthesis in developing vertebrate axons made it clear that there are certain developmental stages in which local translation is present and critical for axonal function [4,6,18]. mRNAs and ribosomal RNA levels in developing axons are appreciably high but RNA levels decline during development and can be no longer be detected in axons of hippocampal neurons by 10 days in vitro [12]. A few mRNAs have been found in some specialized mature neurons: hypothalamic magnocellular neurons axons contain the mRNAs encoding the neurohypophyseal hormone precursors of vasopressin [30] and oxytocin [31]; however, both mRNAs are found to be not associated with polyribosomes [32], making their physiological role unclear. Other examples of mRNA localization in mature vertebrate axons are the mRNAs of the olfactory marker protein (OMP) and various odorant receptors that are found in axon terminals of sensory neurons projecting to the olfactory bulb [33–35]. Both of these neurons are special cases, and they might not be characteristic of mammalian neurons: hypothalamic magnocellular neurons are neurosecretory cells, and sensory odorant receptor neurons, unlike most other neurons in the central nervous system, are able to regenerate [36].

The best experimental indication for the existence of axonal protein translation machinery in mature axons of vertebrates stems from experiments performed on axoplasmic whole mount preparations of lumbar spinal nerve roots [37]. These preparations revealed a restricted localization of ribosome-positive domains near the axolemma. However, it is currently unclear whether these domains are translationally active. Thus, axonal translation appears to be a feature predominantly of developing axons, and it seems likely that most mature vertebrate axons have minimal or no capacity for synthesizing proteins locally.

The striking difference between developing and mature axons in the capability to locally translate proteins indicates the existence of a switch from an actively translating axon to an axon with greatly reduced or no translation. We term this process ‘axonal maturation’. Axonal maturation is characterized by the disappearance of axonal polyribosomes and mRNAs, leading to loss of local translation capability. Additionally, axonal maturation is associated with a change in protein composition, such as the downregulation of guidance cue receptors and the upregulation of presynaptic proteins. These changes might reflect a change in gene transcription programs. The phenomenon of axonal maturation raises several key question: (1) Is axonal maturation a cell intrinsic property or does it occur in response to an extracellular signal? (2) If it is elicited by a signal, what is the identity of these signal(s)? (3) By what mechanism(s) are the mRNAs and polyribosomes removed from the axons upon maturation?

One possibility is that axonal maturation occurs at a specific time point during development. Neurons might be pre-programmed in such a way that at the time when axons should have reached their target and axonal elongation is no longer required, axons lose their capacity for local translation.

Another possibility is that an extracellular signal triggers axon maturation. For example, synapse formation itself might be a likely signal for axonal maturation, and factors such as FGF22 that functions as presynaptic organizing molecules [38] may also promote axonal maturation. An alternative signal could be the reduction in neurotrophin signaling and a resulting drop in axonal cAMP levels. The in vivo expression of neurotrophins, their receptors, and endogenous neuronal cAMP levels that are controlled by neurotrophin signaling decrease sharply during development [39,40]. Neurotrophins and cAMP levels are well established to modulate the transport of mRNAs or mRNA-containing ribonucleoprotein complexes (mRNPs) into dendrites [13,41]. In axons, neurotrophin-3 has been demonstrated to induce the transport of a β-actin mRNA-containing mRNP to axons and to increase β-actin protein levels in growth cones [13,42,43]. Similarly, treatment of dorsal root ganglion axons with the neurotrophins NGF and BDNF increases the axonal transport of cytoskeletal mRNAs, such as β-actin [21].

How could an extracellular signal trigger axonal maturation? Synapse formation will most likely require a yet unknown retrograde signal from the nascent synapse to the nucleus that causes a change in gene transcription, decreasing the levels of cytoskeletal proteins and initiating the transcription of genes encoding presynaptic proteins. Part of this change in gene expression could be the downregulation of proteins required for the axonal transport of mRNAs and of the axonally-localized mRNAs themselves.

Regardless of whether there is an extracellular signal or if there are cell-intrinsic signals, axonal maturation will also require the removal of already axonally-localized mRNAs and polyribosomes. The mammalian RNA-binding protein Staufen-1 has been implicated in dendritic mRNA transport [e. g. 44], but has also been found in axons [45]. While the role of Staufen-1 was originally considered to be an mRNA transport protein it is now clear that Staufen-1 can mediate regulated mRNA decay as well [46]. Staufen-1 can recruit the nonsense-mediated RNA decay factor Upf1 to the 3′UTR of the Arf1 mRNA, and possibly other mRNAs, causing mRNA decay [46]. As Staufen-1 is localized to both axons and dendrites it will be interesting to investigate whether Staufen-1-mediated mRNA decay is involved in the decrease in mRNA upon axonal maturation.

The process of axonal maturation is, at least in part, reversible as several studies show that regenerating axons in vitro [47,48] and probably in vivo [49] regain the ability for local protein synthesis [for a review see 50]. It is tempting to speculate that regeneration is a reversal to a developing state. Indeed severed axons form a structure at their tip that resembles the growth cone of a developing axon [51]. Growth cone formation is dependent upon intra-axonal protein synthesis and degradation [48], and importantly, the regenerative capacity of different types of neurons correlates with the level of intra-axonal protein translation and degradation [48]. The extent to which severed axons are capable of regeneration is directly dependent on the intra-axonal cAMP levels: priming with neurotrophins or pharmacological elevation of cAMP increases the regenerative capability and can overcome the axon growth inhibition by MAG [40,52,53]. Conceivably, elevated cAMP levels may mediate their effects, in part, by regulating axonal protein translation or mRNA localization in regenerating axons as discussed above.

4. Translational control of axonal mRNAs

4.1 Techniques to study local protein translation

To study the regulation of local translation in axons it is necessary to detect translation events with spatial and temporal precision. The study of local translation in axons has been greatly enhanced by the use of fluorescent reporter methods, such as the membrane-anchored, destabilized enhanced GFP (dEGFP) reporter. This method was first used to monitor local protein translation of CAMKII-α in dendrites [54]. The destabilization element appended to the C-terminus of EGFP results in the levels of dEGFP being highly sensitive to changes in protein translation rates [54]. Additionally, since the dEGFP is myristoylated and becomes relatively immobilized in the membrane, fluorescence signals reflect translation at those sites, rather than trafficking from the soma [54]. Using this technology, it was demonstrated that local translation of RhoA in dorsal root ganglion axons is controlled by a yet unidentified cis-acting element in the 3′UTR of this mRNA [6]. Recently, in a variation of this technique, the photoconvertible, fluorescent protein Kaede [55] was expressed on a transcript containing the β-actin 3′UTR to visualize asymmetric, local translation in Xenopus laevis retinal growth cones in response to a netrin-1 gradient [9]. The photoconversion of pre-existing Kaede-tagged protein from green to red fluorescence of Kaede is used to selectively visualize the appearance of newly-synthesized protein which appears as a green fluorescent signal.

The use of these GFP-derived fluorophores is confounded by the fact that newly synthesized protein requires tens of minutes to become fluorescent [56]. Thus, dynamic monitoring of protein synthesis is not possible with these reporters. Fluorescent signals that appear immediately after an experimental treatment are likely derived from the maturation of previously translated EGFP/Kaede, while fluorescence signals that appear later could represent newly translated protein. Destabilization can control for this problem [6,54] since fluorescence is usually measured at two time points, e.g. before and after an experimental treatment, with the second being a time point at which most protein present at the first time point will be degraded.

Another technical concern for destabilized reporters is that pharmacologic manipulations that affect myr-dEGFP signals may reflect alteration in protein degradation rates rather than translation rates. Thus, experimental treatments should be shown not to affect myr-dEGFP degradation rates by monitoring fluorescence signal decay in the presence of protein translation inhibitors.

4.2 Localization of translation in specific, discrete hotspots

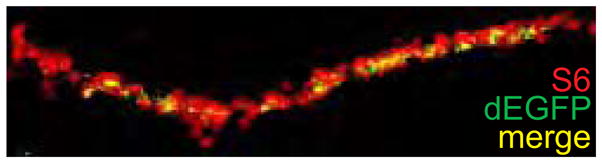

Common to all studies is that local translation is detected in relatively small, discrete puncta within axons and growth cones. This is in contrast to the much more diffuse and widespread appearance of the localization of the corresponding mRNAs [6,9] and indicates that only a subpopulation of all axonal mRNAs is actively translated. Indeed, dEGFP reporter signals are localized to a subset of ribosome clusters, as seen by co-staining with antibodies directed against ribosomal protein S6 (Figure 1). This partial overlap between ribosomal staining and dEGFP puncta indicates that dEGFP-negative clusters are either translationally inactive or that their function is related to the translation of other, distinct mRNAs. In any case, these data demonstrate that RNA clusters or granules are intimately linked to mRNA translation in axons. Currently, little is known about how translational activation of specific RNA clusters or mRNAs is regulated [20].

Figure 1.

dEGFP puncta indicating sites of local translation (green) co-localize (yellow) with a subpopulation ribosomal protein S6-positive clusters (red).

4.3 Emerging models for the regulation of local translation in axons

Several different models have been proposed for the regulation of axonal translation and the reader is referred to excellent reviews [20,57,58]. Here, we discuss some recent studies that highlight novel mechanisms that may regulate mRNA translation in axons and growth cones.

A possible mechanism that might regulate axonal mRNA translation involves the action of microRNAs. MicroRNAs are non-coding RNAs of ~19–22 nucleotide length that can suppress mRNA translation [59] and have been found to co-purify with polyribosomes from mammalian neurons [60]. MicroRNAs bind and assemble a complex of proteins termed the microRNA-induced silencing complexes (miRISC) that bind mRNAs that contain partial sequence complementarity to the microRNA. Binding of miRISC to mRNAs inhibits the initiation of translation [61]. miRISCs contain proteins such as Dicer, argonaute proteins, transactivation-responsive RNA-binding protein, and fragile-X mental retardation protein (FMRP) [62], several of which, including FMRP, Dicer, and the argonaute proteins Ago3 and Ago4, have been found to be localized in axons and growth cones in RNA granule-like structures [19]. The importance of the microRNA pathway in the regulation of axonal translation is suggested by the finding that most identified axonal mRNAs contain several conserved microRNA-binding sites as determined by the TargetScan 3.0 algorithm for microRNA target prediction [63]; for example the 3′UTRs of β-actin, RhoA, and GAP-43 contain 4, 6, and 5 conserved microRNA-binding sites, respectively.

Although evidence for microRNA-mediated suppression of axonal mRNA translation has not yet been demonstrated, there is evidence for the functional activity of some miRISC components in axons [19]. These studies took advantage of the overlap in protein composition of miRISCs and RISCs loaded with small interfering RNA (siRNA), RNAs that have complete sequence complementarity to their mRNA targets. Unlike miRISCs which inhibit the initiation of mRNA translation [61], siRNA-loaded RISCs silence gene expression by initiating mRNA cleavage and degradation [64,65]. In these studies, developing sensory neurons were cultured in compartmented culturing chambers that permit the fluidic isolation of cell bodies and axons. Selective transfection of siRNA targeting the RhoA mRNA resulted in knockdown of the transcript in the axon compartment [19]. Fluorescently-tagged siRNA accumulated in RNA granule like structures which exhibited limited mobility, thus potentially explaining why axonally-transfected the siRNA failed to affect mRNA levels in the cell body [19]. These studies demonstrated that siRNA-loaded RISCs can assemble and function in axons. Furthermore, these studies identified an important methodological approach to knockdown mRNAs in axons, thus allowing their biologic function to be ascertained.

Critical to microRNA-mediated translational repression are processing bodies (P-bodies) [66 and references therein]. P-bodies are cytoplasmic mRNA-processing complexes containing translationally repressed mRNAs and proteins that can mediate the translational suppression, translation, RNAi, or decay of mRNAs [66]. Recent studies suggest that P-bodies are the site for microRNA-dependent repression of translation [61,67]. In the case of CAT-1 mRNA, a transcript induced by cellular stresses such as amino acid deprivation, it was demonstrated that the microRNA miR-122 represses its translation in human Huh7 hepatoma cells and that the repression can be relieved by different stress conditions [68]. The derepression is characterized by the release of CAT-1 mRNA from P-bodies and the subsequent association of the mRNA with polyribosomes [68].

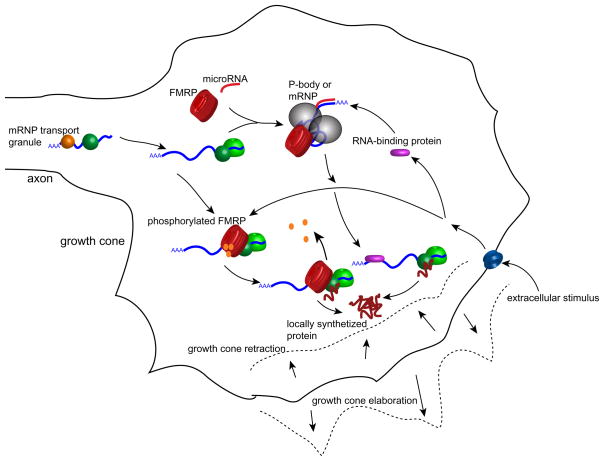

These data raise the possibility that axonal mRNAs are repressed by localization to P-bodies in a microRNA-dependent manner (Figure 2). Extracellular stimuli can trigger the release of these mRNAs from P-bodies and association with polyribosomes. Currently, it is not known whether this mechanism takes place in developing axons. RhoA and κ opioid receptor mRNAs show only very weak axonal expression under control conditions but are both strongly expressed upon application of Semaphorin3A [6] or netrin [16]. It will be important to determine if P-bodies are found in developing axons and to investigate whether these mRNAs show a stimulus-dependent co-localization with P-body components.

Figure 2.

Schematic of proposed signaling pathways regulating mRNA translation in growth cones. Conceivably, axonal mRNAs may be localized to P bodies, sites of microRNA-mediated mRNA translation suppression, and released from these sites upon exposure to translation-inducing stimuli. Axonal mRNAs may also be repressed by phosphorylated FMRP, which may mediate its translational inhibition by recruitment of RISC proteins or microRNAs. Dephosphorylation of FMRP alleviates the inhibition of stalled ribosomes, thereby leading to enhanced local translation.

Another mechanism by which axonal translation might be regulated is through interactions of FMRP with axonal mRNAs. Although FRMP interacts in vitro with a large number of mRNAs via a G-quartet consensus sequence, it remains elusive which of these are relevant to the physiologic roles of FMRP [69]. Interestingly, FMRP binds to a U-rich motif found in the RhoA transcript [70]. Several models have been proposed to explain how FMRP might up- or downregulate the translation of mRNA to which it binds [71]. FMRP has been found in both polyribosomes and mRNPs [72]. In polyribosomes, FMRP is phosphorylated on the highly conserved residue Ser499 and nearby serines [73]. Unphosphorylated FMRP is mainly associated with actively translating polyribosomes while phosphorylated FMRP is associated with stalled, inactive polyribosomes [73]. Dephosphorylation is thought to release the translational repression mediated by FMRP [73]. In mRNPs, FMRP is thought to inhibit initiation of translation [71]. A mechanism for this effect may be related to the recent finding that FMRP associates with components of RISC as well as microRNAs [74]. Thus, the mechanism of FMRP-mediated translational suppression may involve the recruitment of recruit RISC to mRNAs [71].

5. Conclusion

Developing axons are able to respond and adapt to their environment by local protein translation and degradation without the direct involvement of the nucleus. The capacity to synthesize proteins locally is greatly reduced or even completely lost once axons mature, but it can be regained in regenerating axons. Impaired restoration of local translation might contribute to impaired re-growth of axons following axonal injury. The understanding of the mechanisms governing the capability of local protein translation will potentially identify new strategies to enhance the regenerative capability of central nervous system axons [75].

The regulation of axonal mRNAs is poorly understood. Nearly 15 years after the identification of the β-actin zipcode [76], it remains the only identified and well characterized cis-acting element causing axonal localization of mRNAs. The identification of other cis-acting elements in the 3′UTRs of axonally translated mRNAs will greatly advance our understanding of the mechanisms of axonal mRNA transport and translational regulation. Of equal importance is the characterization of trans-acting factors, such as mRNA-binding proteins and possibly microRNAs. The use of conditional Dicer knockout mice [77] will be especially valuable to investigate the roles of microRNAs in axonal protein translation.

Acknowledgments

U. Hengst is supported by the Paralysis Project of America. S.R. Jaffrey is supported by the Fragile X Research Foundation (FRAXA) and NIMH. We are grateful to L.J. Cox for comments on the manuscript. The authors apologize for omitting many primary references due to space limitations.

Abbreviations

- dEGFP

destabilized enhanced green fluorescent protein

- FMRP

fragile-X mental retardation protein

- GEF

guanine nucleotide exchange factor

- miRISC

microRNA-induced silencing complexes

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- mRNP

ribonucleoprotein complex

- P-body

processing body

- RNAi

RNA interference

- UTR

untranslated region

- ZBP1

zipcode binding protein 1

References

- 1.Piper M, Holt C. RNA translation in axons. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:505–23. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.111746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sutton MA, Schuman EM. Local translational control in dendrites and its role in long-term synaptic plasticity. J Neurobiol. 2005;64:116–31. doi: 10.1002/neu.20152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peters A, Palay SL, Webster H. The Fine Structure of the Nervous System. 1. New York: Harper & Row; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell DS, Holt CE. Chemotropic responses of retinal growth cones mediated by rapid local protein synthesis and degradation. Neuron. 2001;32:1013–26. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00551-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell DS, Holt CE. Apoptotic pathway and MAPKs differentially regulate chemotropic responses of retinal growth cones. Neuron. 2003;37:939–52. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu KY, Hengst U, Cox LJ, Macosko EZ, Jeromin A, Urquhart ER, et al. Local translation of RhoA regulates growth cone collapse. Nature. 2005;436:1020–4. doi: 10.1038/nature03885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brunet I, Weinl C, Piper M, Trembleau A, Volovitch M, Harris W, et al. The transcription factor Engrailed-2 guides retinal axons. Nature. 2005;438:94–8. doi: 10.1038/nature04110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yao J, Sasaki Y, Wen Z, Bassell GJ, Zheng JQ. An essential role for β-actin mRNA localization and translation in Ca2+-dependent growth cone guidance. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1265–73. doi: 10.1038/nn1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leung KM, van Horck FP, Lin AC, Allison R, Standart N, Holt CE. Asymmetrical β-actin mRNA translation in growth cones mediates attractive turning to netrin-1. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1247–56. doi: 10.1038/nn1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Álvarez J, Giuditta A, Koenig E. Protein synthesis in axons and terminals: significance for maintenance, plasticity and regulation of phenotype. With a critique of slow transport theory. Prog Neurobiol. 2000;62:1–62. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brittis PA, Lu Q, Flanagan JG. Axonal protein synthesis provides a mechanism for localized regulation at an intermediate target. Cell. 2002;110:223–35. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00813-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleiman R, Banker G, Steward O. Development of subcellular mRNA compartmentation in hippocampal neurons in culture. J Neurosci. 1994;14:1130–40. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-03-01130.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bassell GJ, Zhang H, Byrd AL, Femino AM, Singer RH, Taneja KL, et al. Sorting of β-actin mRNA and protein to neurites and growth cones in culture. J Neurosci. 1998;18:251–65. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00251.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eng H, Lund K, Campenot RB. Synthesis of β-tubulin, actin, and other proteins in axons of sympathetic neurons in compartmented cultures. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-01-00001.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bi J, Hu X, Loh HH, Wei LN. Mouse κ-opioid receptor mRNA differential transport in neurons. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64:594–9. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.3.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsai NP, Bi J, Loh HH, Wei LN. Netrin-1 signaling regulates de novo protein synthesis of κ opioid receptor by facilitating polysomal partition of its mRNA. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9743–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3014-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee SK, Hollenbeck PJ. Organization and translation of mRNA in sympathetic axons. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4467–78. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piper M, Anderson R, Dwivedy A, Weinl C, van Horck F, Leung KM, et al. Signaling mechanisms underlying Slit2-induced collapse of Xenopus retinal growth cones. Neuron. 2006;49:215–28. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hengst U, Cox LJ, Macosko EZ, Jaffrey SR. Functional and selective RNA interference in developing axons and growth cones. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5727–32. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5229-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiebler MA, Bassell GJ. Neuronal RNA granules: movers and makers. Neuron. 2006;51:685–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Willis D, Li KW, Zheng JQ, Chang JH, Smit A, Kelly T, et al. Differential transport and local translation of cytoskeletal, injury-response, and neurodegeneration protein mRNAs in axons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:778–91. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4235-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dent EW, Gertler FB. Cytoskeletal dynamics and transport in growth cone motility and axon guidance. Neuron. 2003;40:209–27. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00633-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bridgman PC. Myosin-dependent transport in neurons. J Neurobiol. 2004;58:164–74. doi: 10.1002/neu.10320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shestakova EA, Singer RH, Condeelis J. The physiological significance of β-actin mRNA localization in determining cell polarity and directional motility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7045–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121146098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luo L, Jan LY, Jan YN. Rho family GTP-binding proteins in growth cone signalling. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1997;7:81–6. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(97)80124-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bullock TH, Horridge GA. Structure and Function in the Nervous Systems of Invertebrates. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giuditta A, Cupello A, Lazzarini G. Ribosomal RNA in the axoplasm of the squid giant axon. J Neurochem. 1980;34:1757–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1980.tb11271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin KC, Casadio A, Zhu H, Yaping E, Rose JC, Chen M, et al. Synapse-specific, long-term facilitation of aplysia sensory to motor synapses: a function for local protein synthesis in memory storage. Cell. 1997;91:927–38. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80484-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohr E, Richter D. Axonal mRNAs: functional significance in vertebrates and invertebrates. J Neurocytol. 2000;29:783–91. doi: 10.1023/a:1010987206526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohr E, Fehr S, Richter D. Axonal transport of neuropeptide encoding mRNAs within the hypothalamo-hypophyseal tract of rats. EMBO J. 1991;10:2419–24. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07781.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jirikowski GF, Sanna PP, Bloom FE. mRNA coding for oxytocin is present in axons of the hypothalamo-neurohypophysial tract. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:7400–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.19.7400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mohr E, Morris JF, Richter D. Differential subcellular mRNA targeting: deletion of a single nucleotide prevents the transport to axons but not to dendrites of rat hypothalamic magnocellular neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:4377–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ressler KJ, Sullivan SL, Buck LB. Information coding in the olfactory system: evidence for a stereotyped and highly organized epitope map in the olfactory bulb. Cell. 1994;79:1245–55. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vassar R, Chao SK, Sitcheran R, Nunez JM, Vosshall LB, Axel R. Topographic organization of sensory projections to the olfactory bulb. Cell. 1994;79:981–91. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wensley CH, Stone DM, Baker H, Kauer JS, Margolis FL, Chikaraishi DM. Olfactory marker protein mRNA is found in axons of olfactory receptor neurons. J Neurosci. 1995;15:4827–37. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-04827.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Graziadei PPC, Monti-Graziadei GA. Continous nerve cell renewal in the olfactory system. In: Jacobson M, editor. Handbook of Sensory Physiology. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1978. pp. 55–82. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koenig E, Martin R, Titmus M, Sotelo-Silveira JR. Cryptic peripheral ribosomal domains distributed intermittently along mammalian myelinated axons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8390–400. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-22-08390.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Umemori H, Linhoff MW, Ornitz DM, Sanes JR. FGF22 and its close relatives are presynaptic organizing molecules in the mammalian brain. Cell. 2004;118:257–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jelsma TN, Aguayo AJ. Trophic factors. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1994;4:717–25. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(94)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cai D, Qiu J, Cao Z, McAtee M, Bregman BS, Filbin MT. Neuronal cyclic AMP controls the developmental loss in ability of axons to regenerate. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4731–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-13-04731.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Knowles RB, Kosik KS. Neurotrophin-3 signals redistribute RNA in neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:14804–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang HL, Singer RH, Bassell GJ. Neurotrophin regulation of β-actin mRNA and protein localization within growth cones. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:59–70. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang HL, Eom T, Oleynikov Y, Shenoy SM, Liebelt DA, Dictenberg JB, et al. Neurotrophin-induced transport of a β-actin mRNP complex increases β-actin levels and stimulates growth cone motility. Neuron. 2001;31:261–75. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00357-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tang SJ, Meulemans D, Vazquez L, Colaco N, Schuman E. A role for a rat homolog of staufen in the transport of RNA to neuronal dendrites. Neuron. 2001;32:463–75. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00493-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Price TJ, Flores CM, Cervero F, Hargreaves KM. The RNA binding and transport proteins staufen and fragile X mental retardation protein are expressed by rat primary afferent neurons and localize to peripheral and central axons. Neuroscience. 2006;141:2107–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim YK, Furic L, Desgroseillers L, Maquat LE. Mammalian Staufen1 recruits Upf1 to specific mRNA 3′UTRs so as to elicit mRNA decay. Cell. 2005;120:195–208. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zheng JQ, Kelly TK, Chang B, Ryazantsev S, Rajasekaran AK, Martin KC, et al. A functional role for intra-axonal protein synthesis during axonal regeneration from adult sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9291–303. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09291.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verma P, Chierzi S, Codd AM, Campbell DS, Meyer RL, Holt CE, et al. Axonal protein synthesis and degradation are necessary for efficient growth cone regeneration. J Neurosci. 2005;25:331–42. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3073-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gaete J, Kameid G, Álvarez J. Regenerating axons of the rat require a local source of proteins. Neurosci Lett. 1998;251:197–200. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00538-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Willis DE, Twiss JL. The evolving roles of axonally synthesized proteins in regeneration. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16:111–8. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bray D, Thomas C, Shaw G. Growth cone formation in cultures of sensory neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978;75:5226–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.10.5226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Qiu J, Cai D, Dai H, McAtee M, Hoffman PN, Bregman BS, et al. Spinal axon regeneration induced by elevation of cyclic AMP. Neuron. 2002;34:895–903. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00730-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Qiu J, Cai D, Filbin MT. A role for cAMP in regeneration during development and after injury. Prog Brain Res. 2002;137:381–7. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(02)37029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aakalu G, Smith WB, Nguyen N, Jiang C, Schuman EM. Dynamic visualization of local protein synthesis in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 2001;30:489–502. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00295-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ando R, Hama H, Yamamoto-Hino M, Mizuno H, Miyawaki A. An optical marker based on the UV-induced green-to-red photoconversion of a fluorescent protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12651–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202320599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tsien RY. The green fluorescent protein. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:509–44. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kindler S, Wang H, Richter D, Tiedge H. RNA transport and local control of translation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:223–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.122303.120653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wells DG. RNA-binding proteins: a lesson in repression. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7135–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1795-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim J, Krichevsky A, Grad Y, Hayes GD, Kosik KS, Church GM, et al. Identification of many microRNAs that copurify with polyribosomes in mammalian neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:360–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2333854100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pillai RS, Bhattacharyya SN, Artus CG, Zoller T, Cougot N, Basyuk E, et al. Inhibition of translational initiation by Let-7 MicroRNA in human cells. Science. 2005;309:1573–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1115079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tang G. siRNA and miRNA: an insight into RISCs. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:106–14. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391:806–11. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mello CC, Conte D., Jr Revealing the world of RNA interference. Nature. 2004;431:338–42. doi: 10.1038/nature02872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Anderson P, Kedersha N. RNA granules. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:803–8. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200512082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu J, Valencia-Sanchez MA, Hannon GJ, Parker R. MicroRNA-dependent localization of targeted mRNAs to mammalian P-bodies. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:719–23. doi: 10.1038/ncb1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bhattacharyya SN, Habermacher R, Martine U, Closs EI, Filipowicz W. Relief of microRNA-mediated translational repression in human cells subjected to stress. Cell. 2006;125:1111–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Veneri M, Zalfa F, Bagni C. FMRP and its target RNAs: fishing for the specificity. Neuroreport. 2004;15:2447–50. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200411150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen L, Yun SW, Seto J, Liu W, Toth M. The fragile X mental retardation protein binds and regulates a novel class of mRNAs containing U rich target sequences. Neuroscience. 2003;120:1005–17. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00406-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zalfa F, Achsel T, Bagni C. mRNPs, polysomes or granules: FMRP in neuronal protein synthesis. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16:265–9. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Feng Y, Absher D, Eberhart DE, Brown V, Malter HE, Warren ST. FMRP associates with polyribosomes as an mRNP, and the I304N mutation of severe fragile X syndrome abolishes this association. Mol Cell. 1997;1:109–18. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ceman S, O’Donnell WT, Reed M, Patton S, Pohl J, Warren ST. Phosphorylation influences the translation state of FMRP-associated polyribosomes. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:3295–305. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Duan R, Jin P. Identification of messenger RNAs and microRNAs associated with fragile X mental retardation protein. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;342:267–76. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-123-1:267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Twiss JL, van Minnen J. New insights into neuronal regeneration: the role of axonal protein synthesis in pathfinding and axonal extension. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23:295–308. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Singer RH. RNA zipcodes for cytoplasmic addresses. Curr Biol. 1993;3:719–21. doi: 10.1016/0960-9822(93)90079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Harfe BD, McManus MT, Mansfield JH, Hornstein E, Tabin CJ. The RNaseIII enzyme Dicer is required for morphogenesis but not patterning of the vertebrate limb. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10898–903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504834102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]