Abstract

Background

The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure recommends that clinicians consider use of multidrug therapy to increase likelihood of achieving blood pressure goal. Little is known about recent patterns of combination antihypertensive therapy use in patients being initiated on hypertension treatment.

Methods

We investigated combination antihypertensive therapy use in newly diagnosed hypertensive patients from the Cardiovascular Research Network Hypertension Registry. Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess the relationship between combination antihypertensive therapy and 12-month blood pressure control.

Results

Between 2002–2007, a total of 161,585 patients met criteria for incident hypertension and were initiated on treatment. During the study period, an increasing proportion of patients were treated initially with combination rather than single agent therapy (20.7% in 2002 compared to 35.8% in 2007, P<0.001). This increase in combination therapy use was more pronounced in patients with stage 2 hypertension, whose combination therapy use increased from 21.6% in 2002 to 44.5% in 2007. Nearly 90% of initial combination therapy was accounted for by two combinations, a thiazide and a potassium-sparing diuretic (47.6%) and a thiazide and an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (41.4%). After controlling for relevant clinical factors, including subsequent intensification of treatment and medication adherence, combination therapy was associated with increased odds of blood pressure control at 12 months (odds ratio compared to single-drug initial therapy 1.20; 95% CI 1.15 – 1.24, P<0.001).

Conclusions

Initial treatment of hypertension with combination therapy is increasingly common and is associated with better long-term blood pressure control.

Introduction

The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC-7) recommends consideration of initial hypertension therapy with more than 1 drug, particularly when blood pressure (BP) is >20/10 mm Hg above goal, to increase the likelihood of achieving BP goal in a timely fashion.(1) Moreover, clinical trials demonstrate that most hypertensive patients will not achieve goal BP with a single drug alone, further supporting the use of multidrug therapy.(2–4) Combining drugs with complementary mechanisms of action permits use of lower doses of each, reducing the risk of dose-dependent adverse events. However, to date, little is known about use of combination therapy for the initial treatment of hypertension in routine practice.

Prior studies have assessed prevalent combination therapy use for hypertension and found increasing use over time.(5;6) However, many of these studies are dated, report trends prior to the release of the JNC-7 report, or provide little detail regarding the most commonly occurring drug combinations. Weycker et al. found that fewer patients with stage 1 than with stage 2 hypertension at time of diagnosis achieved adequate blood pressure control (BP<140/90) at 360 days. However, use of combination therapy was not reported nor its association with BP control. (7) There is a lack of contemporary data regarding the most commonly used combination therapy for newly diagnosed hypertension patients and the association between initial combination therapy use and BP control.

Accordingly, we assessed trends in use of combination versus single agent therapy as initial treatment for patients with incident hypertension using the Cardiovascular Research Network (CVRN) Hypertension registry from 2002–2007. Next, we identified the most common combination agents used over time and stratified use of combination therapy by stage of hypertension at time of treatment initiation. Finally, we assessed the association between combination agent use and BP control 12 months following initiation of hypertension therapy among patients with incident hypertension.

Methods

Definition of the Hypertensive Cohort

This study was conducted within the Cardiovascular Research Network (CVRN), a consortium of research organizations affiliated with the HMO Research Network and sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The CVRN Hypertension Registry includes all adult patients with hypertension at 3 large integrated health care delivery systems, HealthPartners of Minnesota (HP), Kaiser Permanente Colorado (KPCO), and Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC). The algorithm for entry into the cohort has been described previously.(8) Briefly, patients entered into the registry upon meeting one or more of the following criteria: (1) at least 2 consecutive elevated BP measurements (i.e., ≥140 mm Hg systolic and/or 90 mm Hg diastolic or ≥130/80 mm Hg in the presence of diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease); (2) 2 diagnostic codes for hypertension (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] codes: 401.x to 405.x) recorded on separate dates; (3) 1 diagnostic code for hypertension plus prescription for an antihypertensive medication; or (4) 1 elevated BP measurement plus 1 diagnostic code for hypertension.

The current analysis included 161,585 patients with incident hypertension between 2002 and 2007 who were started on therapy with antihypertensive medications. Incident hypertension was defined as having 1 year or longer health plan membership with drug coverage prior to meeting hypertension registry entry criteria, without a prior hypertension diagnosis, and without prior pharmacy dispensing or claims filed for antihypertensive medications. Individuals who qualified for entry into the cohort, but whose initial BP upon cohort entry was normal (n=16,038) or missing (n=41,473) were excluded. We excluded patients whose initial BP upon entry into the cohort was normal to help ensure that the patients included in the analysis did indeed have as-yet-untreated incident hypertension. Only individuals with at least 180 days of health plan membership with drug coverage after entry into the cohort were included in the current analysis. Baseline BP was defined as the BP closest to the date of entry into the cohort and could include BP measurements up to 90 days prior to cohort entry date. In addition, the 1.4% of patients prescribed 3 or medication classes as initial treatment for a new diagnosis of hypertension were not included in the analysis since these patients may have prevalent rather than incident hypertension.

Combination therapy

Combination antihypertensive therapy, the primary exposure of interest, was defined as treatment initiation with two antihypertensive medications for patients with incident hypertension. Treatment initiation was defined as the first prescription or set of prescriptions filled after entry in the hypertension registry in patients without prior diagnosis of hypertension. Initiation of medication was determined using pharmacy dispensing data, which include all medications dispensed from health plan outpatient pharmacies, or claims filed for medications.

Blood Pressure Control at 12 Months

BP control at 12 months was the primary outcome of interest and was assessed using the BP measurement closest to 12 months after initiation of hypertension treatment (and within a 6 – 18 month window). BP was considered uncontrolled if BP > 140/90 (or >130/80 in patients with diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease). Systolic and diastolic BP data at 12 months were available for 77.4% of the cohort.

Statistical Analysis

The blood pressure levels, stage of hypertension and treatment with either combination or single agent therapy as well as the specific combination were described for patients with incident hypertension being started on treatment during the study period. Student’s t test and χ2 test were used to compare baseline variables in patients treated with combination versus single agent therapy. Multivariable logistic regression assessed demographic and clinical factors associated with initial combination antihypertensive drug therapy. The model included site of care, gender, race, smoking status, year of entry into the cohort, and co-morbid compelling indications for particular antihypertensive drug classes (e.g., diabetes, myocardial infarction, heart failure, chronic kidney disease or stroke). ICD-9-CM codes were used to define myocardial infarction (410.*), congestive heart failure (428.*), and ischemic stroke (433.*, 434.*, and 436). Diabetes mellitus was defined by the following: (1) 2 outpatient diagnoses or 1 primary inpatient discharge diagnosis of diabetes mellitus (ICD-9-CM code 250.x); (2) prescription for any antidiabetic medication other than metformin or thiazolidinediones; or (3) prescription for metformin or a thiazolidinedione plus a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus; or (4) hemoglobin A1c value > 7% or 2 fasting plasma glucose values > 7 mmol/L (126 mg/dL) on separate dates. Chronic kidney disease was defined as 2 consecutive serum creatinine values that yield estimated glomerular filtration rates < 60 mL/minute when the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation is applied or by an ICD-9-CM diagnostic code for chronic kidney disease (codes 585.1–585.9). To assess the association between combination therapy and BP control at 12 months, multivariable logistic regression models were constructed adjusting for these variables, as well as BP stage and combination antihypertensive agent use. Data from patients who died or who were missing a blood pressure measurement within a 6-month window around the 12-month time point were censored.

To further assess the robustness of our findings, we performed a series of sensitivity analyses. First, we assessed the association between fixed-dose (i.e., 2 antihypertensive medications in a single pill) or free (i.e., 2 antihypertensive medications as 2 separate pills) combinations versus single agent therapy and BP control. Second, we evaluated the association between ACE/thiazide combination therapy versus single agent and BP control. Third, we adjusted for adherence to antihypertensive medications in the evaluation of the association between combination therapy and BP control. Medication adherence was calculated as total days’ supply dispensed divided by the number of days between first and last fills for that drug. (9) Patient-level adherence with antihypertensive drugs was calculated as the time-weighted average of adherence for each antihypertensive drug.

Fourth, we compared therapy intensification between patients initiated on combination therapy versus single agent therapy. Intensification of antihypertensive therapy was based on the number of times a drug dose was increased and/or the number of times an antihypertensive drug class was added (including the addition of a new class in substitution for another class). Thus, this intensification metric accounts for changes in the antihypertensive drug regimen after our initial assessment of single vs. combination therapy. We hypothesized that patients started on combination therapy would have less need to have therapy intensified during the follow-up period since they were being initiated on more antihypertensive therapy. Finally, we adjusted for therapy intensification in the assessment of the association between combination therapy initiation and BP control. All analyses were two-tailed, and a P < 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were completed using SAS v9.1 (SAS Inc, NC). The authors are solely responsible for the design and conduct of this study, all study analyses, the drafting and editing of the paper and its final contents. Funding for the study was provided by the NIH.

Results

Baseline Characteristics of Incident Hypertension Patients

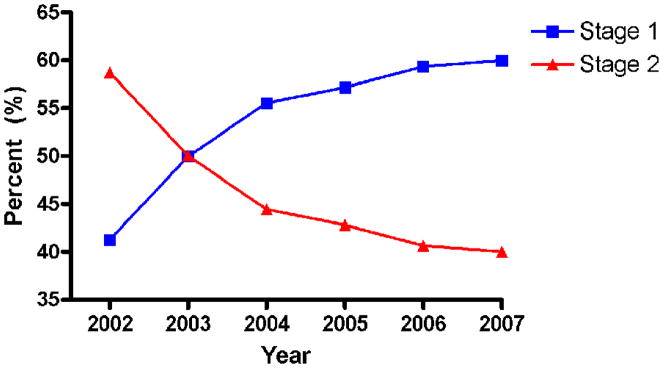

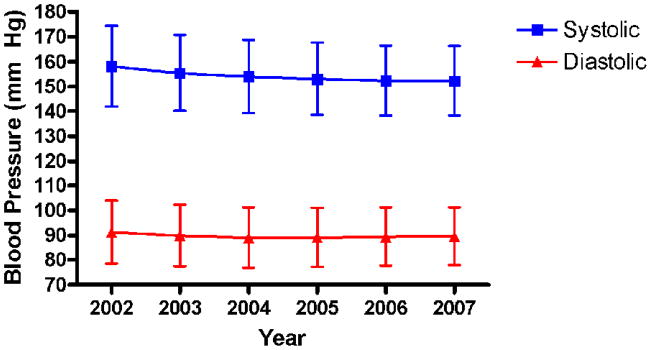

Among 161,585 patients with incident hypertension being initiated on therapy during the study period, there was a decline in the proportion of individuals entering the cohort with stage 2 hypertension (defined as initial SBP ≥ 160 mm Hg or DBP ≥ 100 mm Hg), from 58.7% in 2002 to 40.0% in 2007 (P<0.001, Figure 1). There was a corresponding decrease in systolic blood pressure (SBP) during the same time period from a mean SBP of 158.1 mmHg for those entering the cohort in 2002 to a mean of 152.3 mm Hg for those entering in 2007 (Figure 2). The mean diastolic blood pressure (DBP) for those entering the cohort in 2002 was 91.3 mmHg. By 2004, the mean DBP decreased to 89.1 mmHg, subsequently increasing slightly to 89.6 mmHg in 2007.

Figure 1.

Study participants’ baseline blood pressure upon entering the hypertension cohort. Between 2002 and 2007, there was an increase in the proportion of patients whose baseline blood pressure was in the stage 1 range (blue line). There was a corresponding decrease in the proportion with a baseline blood pressure in the stage 2 range (red line).

Figure 2.

Study participants’ mean blood pressure upon entering the hypertension cohort. The error bars represent standard deviation. Between 2002 and 2007, the mean systolic blood pressure of patients with incident hypertension decreased. The mean diastolic blood pressure differed little in 2002 compared to 2007.

Initial Combination Therapy for Incident Hypertension

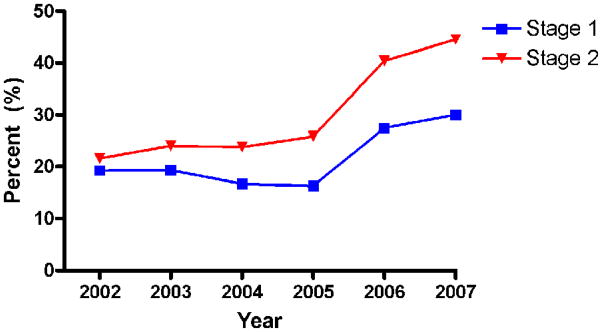

In both stage 1 and stage 2 hypertensive patients, the proportion initially treated with two drugs increased from 2002–2007. This increase was larger in patients with stage 2 hypertension. Among patients newly diagnosed with stage 2 hypertension, the proportion initially treated with two drugs rose from 21.6% in 2002 to 44.5% in 2007 (Figure 3). Nearly 90% of initial combination therapy was accounted for by two combinations of classes. A combination of a thiazide and a potassium-sparing diuretic accounted for 47.6% of initial combination therapy, and a combination of a thiazide and an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor accounted for another 41.4%. Of patients initiated on antihypertensive treatment with 2 drugs, 86% of first antihypertensive prescriptions were for fixed-dose combination products.

Figure 3.

The use of two-drug combination antihypertensive therapy as initial treatment for incident hypertension increased significantly between 2002 and 2007. The increase was larger among patients with stage 2 hypertension at time of diagnosis.

Less common combinations of antihypertensive medication classes included a thiazide and a beta blocker (5.3% of all combination therapy), and an ACE inhibitor and a beta blocker (2.6% of initial combination therapy). The remaining 3.1% of initial combination therapy was comprised of a wide variety of infrequent combinations, such as ACE inhibitor/loop diuretic (0.54%), thiazide/calcium channel blocker (CCB) (0.56%), ACE inhibitor/CCB (0.17%), and thiazide/angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) (0.14%).

Patients treated with initial combination therapy (fixed-dose or free combinations) were slightly younger and had higher SBP and DBP than those treated initially with a single agent (Table I). Compared with patients with stage 1 hypertension, a higher proportion of patients with stage 2 hypertension were treated with combination therapy. Multivariable logistic regression identified several factors associated with combination therapy, including more recent entry into the cohort and prior myocardial infarction (Table II). Conversely, diabetes mellitus, history of ischemic stroke, and history of chronic kidney disease were associated with initiation of a single antihypertensive agent.

Table I.

Characteristics of the Cohort by Type of Initial Antihypertensive Therapy (single versus combination).

| Characteristic | N | Single N = 122,662 |

Combination N = 38,923 |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 161,585 | 55.8 ± 13.5 | 55.1 ± 12.9 | < 0.001 |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) | 124,537 | 29.9 ± 6.5 | 30.5 ± 6.6 | < 0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | 161,585 | 153.6 ± 14.7 | 156.8 ± 15.7 | < 0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | 161,585 | 89.1 ± 12.1 | 91.8 ± 12.1 | < 0.001 |

| Sex, N (%) | ||||

| Female | 83,086 | 62,738 (51.2) | 20,348 (52.3) | <0.001 |

| Race, N (%) | ||||

| African American | 11,506 | 8,438 (6.9) | 3,068 (7.9) | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 15,868 | 12,299 (10.0) | 3,569 (9.2) | |

| Native American/Asian/mixed/other | 19,216 | 15,003 (12.2) | 4,213 (10.8) | |

| White | 79,860 | 61,282 (50.0) | 18,578 (47.7) | |

| Unknown | 35,135 | 25,640 (20.9) | 9,495 (24.4) | |

| Hypertension Stage, N (%) | ||||

| Stage 1 | 86,473 | 68,483 (55.8) | 17,990 (46.2) | <0.001 |

| Prior Myocardial Infarction, N (%) | ||||

| Yes | 767 | 500 (0.4) | 267 (0.7) | <0.001 |

| Prior Ischemic Stroke, N (%) | ||||

| Yes | 2,269 | 1,877 (1.5) | 392 (1.0) | <0.001 |

| Prior Congestive Heart Failure, N (%) | ||||

| Yes | 1,094 | 732 (0.6) | 362 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| Prior Diabetes Mellitus, N (%) | ||||

| Yes | 22,341 | 19,287 (15.7) | 3,054 (7.9) | <0.001 |

| Prior Chronic Kidney Disease, N (%) | ||||

| Yes | 6,071 | 4,924 (4.0) | 1,147 (3.0) | <0.001 |

| Average Medication Adherence | 130,884 | 0.78 ± 0.28 | 0.76 ± 0.28 | <0.001 |

| Number of Medication Dose Increases, N (%) | ||||

| 0 | 121,350 | 92,008 (75.0) | 29,342 (75.4) | 0.33 |

| 1 | 32,072 | 24,439 (19.9) | 7,633 (19.6) | |

| ≥2 | 8,163 | 6,215 (5.1) | 1,948 (5.0) | |

| Number of New Medication Classes Added to Initial Regimen, N (%) | ||||

| 0 | 103,118 | 76,735 (62.6) | 26,383 (67.8) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 43,782 | 34,042 (27.8) | 9,740 (25.0) | |

| ≥2 | 14,685 | 11,885 (9.7) | 2,800 (7.2) | |

Table II.

Results of Logistic Regression Model Predicting Initiation of Combination Therapy Upon Entry Into CVRN Hypertension Registry, 2002–2007.

| Predictor | Odds Ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Year | ||

| 2002 | 1.00 | Reference |

| 2003 | 1.11 | 1.05 to 1.18 |

| 2004 | 1.02 | 0.96 to 1.08 |

| 2005 | 1.08 | 1.02 to 1.15 |

| 2006 | 2.11 | 1.98 to 2.24 |

| 2007 | 2.40 | 2.25 to 2.56 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (per 10 mm Hg increase) | 1.15 | 1.14 to 1.16 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (per 10 mm Hg increase) | 1.14 | 1.13 to 1.16 |

| Site | ||

| KPNC | 1.00 | Reference |

| KPCO | 1.20 | 1.15 to 1.25 |

| HP | 0.77 | 0.71 to 0.83 |

| Age (per 10 year increase) | 1.04 | 1.03 to 1.06 |

| Gender, Female vs Male | 1.01 | 0.98 to 1.04 |

| Race | ||

| White | 1.00 | Reference |

| Black | 1.21 | 1.14 to 1.27 |

| Hispanic | 1.03 | 0.99 to 1.08 |

| Asian or Other | 1.05 | 1.01 to 1.10 |

| Missing | 1.16 | 1.12 to 1.20 |

| Smoking status | ||

| Current | 1.00 | Reference |

| Former | 0.86 | 0.80 to 0.93 |

| Never | 0.91 | 0.87 to 0.94 |

| Other | 0.91 | 0.83 to 0.99 |

| Missing | 1.10 | 1.01 to 1.20 |

| Body Mass Index (per 5 unit increase) | 1.09 | 1.08 to 1.11 |

| Congestive Heart Failure, Yes vs No | 1.74 | 1.50 to 2.03 |

| Diabetes Mellitus, Yes vs No | 0.58 | 0.55 to 0.61 |

| Myocardial Infarction, Yes vs No | 2.07 | 1.74 to 2.47 |

| Ischemic Stroke, Yes vs No | 0.77 | 0.68 to 0.87 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease, Yes vs No | 0.77 | 0.71 to 0.83 |

KPNC, Kaiser Permanente Northern California; KPCO, Kaiser Permanente Colorado; HP, HealthPartners

Blood Pressure Control at 12 Months Following Initiation of Antihypertensive Therapy

After exclusion of patients whose 12-month BP control status was missing, the population included 124,984 patients with 12-month BP control data. The 12 month BP was controlled in 78,095 patients (62.5% of participants with incident hypertension). Initial treatment with two antihypertensive drugs was associated with higher odds of BP control at 12 months (odds ratio compared to single-drug initial therapy 1.16; 95% CI 1.12 – 1.20, P<0.001 adjusting for demographics and clinical characteristics. The findings were consistent whether patients were prescribed fixed-dose combination agents (odds ratio compared to single-drug initial therapy 1.16; 95% CI 1.12 – 1.20, P<0.001) or two free-drug antihypertensive agents (odds ratio compared to single-drug initial therapy 1.14; 95% CI 1.06 – 1.23, P<0.001). In addition, prescription of the combination thiazide/ACE inhibitor was also associated with increased odds of BP control compared to initial single agent therapy (OR 1.25; 95% CI 1.19 – 1.31, P<0.001 for thiazide/ACE inhibitor compared to single-drug initial therapy).

Next, we compared adherence to antihypertensive medication between patients started on combination versus single agent therapy. While adherence to antihypertensive medications was statistically different between the two groups, the difference in adherence levels was not clinically significant (mean adherence 0.76±0.28 vs. 0.78±0.26 for combination versus single agent therapy; P<0.001). Further, the association between combination therapy and improved BP control remained consistent after adjusting for adherence to antihypertensive medications (OR 1.19; 95% CI 1.15 – 1.24, P<0.001). Patients initiated on combination therapy were less likely to have an increase in the number of classes of antihypertensive medications during the year of follow-up compared to patients prescribed single agent therapy (32.1% vs. 37.4%; for the percent of patients with any increase in classes of antihypertensive medications; P<0.001); however, there was no difference in the number of dosing increases of antihypertensive medications (24.6% vs. 24.9%; P=0.33). After additional adjustment for therapy intensification, combination therapy remained associated with increased odds of BP control (OR 1.20; 95% CI 1.15 – 1.24, P<0.001). Baseline systolic blood pressure and initial single vs. combination therapy did not have an interactive effect on 12-month BP control, P=0.75.

Discussion

The objectives of this study were to assess trends in use of combination versus single agent therapy as initial treatment for patients with incident hypertension and to evaluate use of combination therapy and BP control. We found that initial therapy with two drugs for new-onset hypertension was associated with better BP control at 12 months compared to single agent therapy even after adjusting for, among other factors, subsequent therapy intensification and medication adherence. The association between two-drug initial therapy for hypertension and better 12-month blood pressure control was found irrespective of use of fixed-dose or free combination products. In addition, we found increasing use of combination therapy as first-line therapy for hypertension from 2002 to 2007, with a particularly large increase in 2006. This increase was larger in patients who were initially treated for stage 2 hypertension. Finally, between 2002 and 2007, fewer patients were treated initially for stage 2 hypertension, a finding perhaps related to earlier recognition of hypertension by clinicians. Our findings highlight not only the increasing role of combination antihypertensive agents in routine practice, but also the potential long-term benefit of initiating two antihypertensive medications when hypertension is diagnosed.

Several studies, differing in important ways from the current study, have reported aspects of the pharmacoepidemiology of combination antihypertensive therapy. A study of Canadian office visits reported little change in the use of fixed-dose antihypertensive products as a proportion of all antihypertensive agents used between 1996 and 2006.(10) Our finding of increasing use of combination therapy is consistent with other studies that have considered the more common(5) free-drug combinations as well as the less common fixed-dose combinations. (5;6) In what was perhaps the most detailed longitudinal epidemiologic study of combination therapy prior to the current study, Ma et al. reported increasing use of several combinations between 1993 and 2004. Increasingly common combinations included ACE inhibitor or ARB in combination with diuretic (10% versus 27% of all antihypertensive drug visits), CCB (8% versus 17%), or beta blocker (9% versus 16%), as well as diuretic/beta blocker combination therapy (9% versus 16%).(5) Overall, the most common two-drug combinations in the study by Ma et al. were diuretic/beta blocker, diuretic/ACE inhibitor or ARB, and ACE inhibitor or ARB/beta blocker. While we also found a high proportion of patients treated with a combination of a diuretic and an ACE inhibitor, the other common combinations in the study by Ma et al. were not commonly observed in our cohort. The practice patterns observed may be related to formulary considerations specific to managed care organizations. In contrast to Ma’s study, the current study focused on initiation of therapy. The association between certain comorbid compelling indications and initiation of a single drug is somewhat surprising. This finding remains unexplained, but may be attributable to a variety of factors, including a desire to avoid a too-rapid decrease in blood pressure in patients who have a history of CVA. To our knowledge, the current study is the first large epidemiologic study reporting the association between initial treatment with combination antihypertensive therapy and long-term BP control.

Our main finding, the association between initial combination therapy and improved 12-month BP control, is consistent with clinical trials data. Feldman et al. found improved 6-month BP control in patients randomized to a treatment algorithm involving initiation of two antihypertensive drugs compared to guideline-based management.(11) In a large meta-analysis of antihypertensive therapy, the use of a second antihypertensive agent was associated with approximately 5 times the extra BP lowering effect compared to doubling the dose of the initial medication.(12) This increased efficacy likely arises from the fully additive effect provided by some drug combinations with complementary mechanisms of actions.(13) Moreover, this finding adds to the evidence supporting current guidelines, which recommend consideration of combination antihypertensive therapy in many situations.

The American Society of Hypertension (ASH) recently published a position paper in which various two-drug combinations of antihypertensive agents were classified as preferred, acceptable, or less effective.(13) The combination of a thiazide and a potassium-sparing diuretic was recognized as a form of combination antihypertensive therapy in both JNC 7 and the ASH guidelines. Preferred combinations include RAAS inhibitor/diuretic and RAAS inhibitor/CCB. Although the data analyzed in this study predated the publication of this position paper, 94.2% of prescriptions in our study were accounted for by three combinations judged to be either preferred or acceptable. A small minority of combinations were of the less effective type, including ACE inhibitor/beta blocker (2.6% of all combinations). Although our findings suggests that clinical practice is largely consistent with expert consensus and clinical trial data, use of a renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) antagonist in combination with a calcium channel blocker, a preferred combination, was rare, accounting for <1% of combination therapy. In recommending RAAS/calcium channel blocker combination therapy, the ASH position paper cites the ACCOMPLISH trial,(14) which was published after the end of data collection for the present study. It is possible that the use of RAAS/calcium channel blocker combination therapy has increased since the publication of ACCOMPLISH. Moreover, it is possible that specific formulary considerations at the sites involved in the study may have had an impact on the use of calcium channel blockers in combination with RAAS antagonists, although generic drugs are available in both of these classes.

This study has several limitations. The study cohort was comprised of patients treated within integrated healthcare delivery systems, which could limit the applicability of the findings to other populations. The inclusion of multiple geographically separated sites with different health plans increases the likelihood that the results reflect practice in many areas. During the study period, hypertension practice guidelines and algorithms were made available via paper format and/or the Web within each health care system and disseminated through educational conferences. These guidelines were consistent with national guidelines (eg, JNC-7) on hypertension management. In addition, generic medications were encouraged over brand name medications, but medications representing all therapeutic classes for hypertension treatment were available. Clinicians were encouraged to follow evidence-based practice; however, there was no mandate to use a specific agent in the initial treatment of hypertension. An emphasis on the use of generic drugs may have resulted in greater use of the combination of hydrochlorothiazide and triamterene than would be observed in other practice settings. The three large health systems in which the study was conducted have preferred formularies, and there are financial incentives for both physicians and patients to avoid expensive and/or non-generic drugs, including many branded combination therapy treatments. Our analysis, however, was performed at the level of antihypertensive classes, rather than individual products, and generic drugs were available in most of the classes during the time period we studied, particularly in the later years. In addition, our analysis of the association between combination therapy and 12-month BP excluded data from patients for whom 12-month BP data was not available. It is possible that inclusion of those data, had they been available, might have altered the findings. Finally, the analysis only takes into account prescriptions which were filled, rather than all prescribed medications. However, failure to fill prescriptions would be expected to bias the study toward a lack of effect of combination antihypertensive therapy on 12-month BP.

Initial treatment of newly diagnosed hypertensive patients with a combination of two antihypertensive drugs is becoming increasingly common, particularly among patients with stage 2 hypertension. After controlling for subsequent changes in therapy, initial treatment with two antihypertensive agents was associated with a higher odds of BP control at one year. Clinicians should consider initiation of two antihypertensive agents upon diagnosis of hypertension.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This study was funded by grant U19HL091179 from the NHLBI as part of the Cardiovascular Research Network. Dr Ho is supported by a VA Research & Development Career Development Award (05-026-2). Dr. Byrd was supported by a Department of Veterans Affairs Cardiology Research Fellowship.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest/Disclosure(s):

P.M.H. serves as a consultant for Wellpoint, Inc.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black HR, Elliott WJ, Grandits G, et al. Principal results of the Controlled Onset Verapamil Investigation of Cardiovascular End Points (CONVINCE) trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2073–2082. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.16.2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. HOT Study Group. Lancet. 1998;351:1755–1762. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)04311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cushman WC, Ford CE, Cutler JA, et al. Success and predictors of blood pressure control in diverse North American settings: the antihypertensive and lipid-lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial (ALLHAT) J Clin Hypertens. 2002;4:393–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2002.02045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma J, Lee KV, Stafford RS. Changes in antihypertensive prescribing during US outpatient visits for uncomplicated hypertension between 1993 and 2004. Hypertension. 2006;48:846–852. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000240931.90917.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muntner P, Krousel-Wood M, Hyre AD, et al. Antihypertensive prescriptions for newly treated patients before and after the main antihypertensive and lipid-lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial results and seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure guidelines. Hypertension. 2009;53:617–623. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.120154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weycker D, Edelsberg J, Vincze G, et al. Blood pressure control in patients initiating antihypertensive therapy. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:169–176. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selby JV, Peng T, Karter AJ, et al. High rates of co-occurrence of hypertension, elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and diabetes mellitus in a large managed care population. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steiner JF, Ho PM, Beaty BL, et al. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are not clinically useful predictors of refill adherence in patients with hypertension. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:451–457. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.841635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hemmelgarn BR, Chen G, Walker R, et al. Trends in antihypertensive drug prescriptions and physician visits in Canada between 1996 and 2006. Can J Cardiol. 2008;24:507–512. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(08)70627-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feldman RD, Zou GY, Vandervoort MK, et al. A simplified approach to the treatment of uncomplicated hypertension: a cluster randomized, controlled trial. Hypertension. 2009;53:646–653. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.123455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wald DS, Law M, Morris JK, et al. Combination therapy versus monotherapy in reducing blood pressure: meta-analysis on 11,000 participants from 42 trials. Am J Med. 2009;122:290–300. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gradman AH, Basile JN, Carter BL, et al. Combination therapy in hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2010;4:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jamerson K, Weber MA, Bakris GL, et al. Benazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2417–2428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]