Abstract

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a disease characterized by inappropriate response to self-antigens. Genetic, environmental and hormonal factors are believed to contribute to the development of the disease. We think of SLE pathogenesis as occurring in three phases of variable duration. A series of regulatory failures during the ontogeny of the immune system lead to the emergence of auto-reactive clones and the production of auto-antibodies (phase I). As the immune response to self-antigens broadens, the auto-antibody repertoire is enriched (phase II) and clinical manifestations eventually ensue (phase III). The final result is tissue damage that if not treated will lead to the functional failure of such important organs as the kidney and brain.

Keywords: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, Auto-antibodies, Complement, Cell signaling, CD3ζ chain, Fcγ receptor, NFAT, Nephritis

1. Introduction

A prototypic autoimmune disease, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a syndrome characterized by inappropriate immune response to self-antigens. In SLE, the immune system fails to control auto-reactive T, B, and antigen-presenting cells that produce an array of auto-antibodies and cytokines leading to the cellular infiltration of various organs and the local activation of complement (1). Eventually organ damage occurs that, if left untreated, leads to serious and even fatal complications such as renal failure.

Although the clinical and laboratory findings in SLE are well described, the exact events that lead to the development of the disease are unclear. Schematically, we can hypothesize based on the current evidence that the development of SLE occurs in three phases:

The initial break in immunologic tolerance toward certain self-antigens induced by a poorly characterized interplay between environmental, hormonal and genetic factors.

The propagation of the abnormal immune response and the appearance of laboratory evidence of immunological dysfunction, such as antinuclear antibodies.

The clinical manifestations, with one or more organs such as the joints, skin or kidneys displaying inflammation-induced damage.

In this chapter, we will discuss initially the epidemiology and clinical manifestations of SLE, before addressing the pathogenetic mechanisms that lead to the expression of the disease.

2. Epidemiology: Heredity, Gender and the Environment

SLE is a relatively rare disease affecting approximately 40–50 individuals per 100,000 people in the United States (2), with an incidence of approximately two to three new cases per year per 100,000 persons (3). Worldwide studies, although showing variable incidence and prevalence among different populations (4–6), agree in that the majority of patients with SLE are women of childbearing age; the female: male ratio is estimated between 6 and 14:1 (7–10). SLE is less common at the extremes of age but can affect both children (11) and elderly individuals (12, 13); interestingly, the difference in incidence between men and women is not as striking in these age groups (13). These observations led to the hypothesis that hormonal factors, either the excess of estrogens or lack of androgens, may be involved in the development of the disease by influencing the development and/or reactivity of the immune system.

In addition to the gender differences in prevalence, SLE prevalence and severity differ among different populations. For example, individuals of African and Asian descent in the United States are more commonly and more severely affected than European-Americans (3, 14, 15). This observation underscores the fact that genetic factors predispose individuals to the development of SLE. Adding further credence to this argument, twin studies have shown a higher concordance rate for SLE among monozygotic versus dizygotic twins (24% vs. 2%) (16).

Nevertheless, genetic factors can not account for all the cases of SLE and therefore both natural factors and infectious agents have been implicated in the development of the disease. One of the first environmental factors that was found to be associated with SLE is sunlight: indeed, a significant proportion of patients display skin sensitivity to light and in particular ultraviolet light (17). No definite association with a particular infectious agent has been made; one exception is the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), a virus associated with B cell hyperactivity. Patients with SLE are almost universally seropositive for EBV as compared to lower rates in healthy controls. Given this as well as similarity of EBV antigens and auto-antigens targeted by auto-antibodies found in SLE patients’ sera, EBV has been suggested as a possible instigator of SLE (18).

The above described epidemiological characteristics of SLE suggest that a host of environmental, infectious and hormonal factors when applied to a genetically predisposed individual may lead to the development of SLE. The exact factors and the processes that trigger the disease are unclear and are the focus of many studies in humans with SLE and animal models of lupus.

3. Clinical Manifestations: Evaluating and Treating Systemic Inflammation

The initial clinical presentation, course and outcome of SLE are highly variable. The diagnosis is based on the presence of certain clinical and laboratory findings that are listed in Table 1 (19). Typically the disease course in most patients is characterized by periods of high activity (flare) and remission. The duration and frequency of these flares, their severity and precise clinical picture differ significantly among patients. This makes SLE a challenging disease to diagnose and treat.

Table 1.

Criteria for the diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus

| 1. | Malar rash |

| 2. | Discoid rash |

| 3. | Photosensitivity |

| 4. | Oral ulcers |

| 5. | Arthritis |

| 6. | Serositis |

| 7. | Renal disorder |

| 8. | Neurologic disorder |

| 9. | Hematologic disorder |

| 10. | Immunologic disorder |

| 11. | Antinuclear antibody (ANA) |

The symptoms and signs of SLE can be broadly categorized as constitutional (a result of systemic inflammation), and organ-specific (20–23). Constitutional symptoms that patients with SLE may experience include high fevers, fatigue, and weight loss. More importantly the overwhelming majority of patients with SLE will present with specific organ involvement. Approximately 60–90% of the patients will develop some form of inflammatory skin rash which is oftentimes caused or exacerbated by sunlight (ultraviolet radiation) (17). The joints are affected in a significant percentage of patients in the form of inflammatory arthritis with pain and swelling. Inflammation involving the serous membranes (pleuritis, pericarditis) manifesting as chest or abdominal pain, is also common (10–30% of the patients) (20, 21). SLE affects the hematologic system with a decrease in the levels of white cells, platelets, and red cells; life threatening thrombocytopenia and severe anemia although uncommon can be seen in patients with SLE. In the most severe forms of SLE, the kidney and the central nervous systems are affected (23). The patients with renal lupus will present with abnormalities in the urine (blood and/or protein in the urine) and oftentimes edema. If left untreated, renal lupus may lead to severe complications including renal failure and vascular disease. Patients with central nervous involvement present with neurological complications (e.g., strokes, pain due to nerve damage) and/or psychiatric manifestations (mania, depression). SLE may also affect other organs such as the muscles (myositis), the lung (pneumonitis), and the heart (myocarditis). Overall, SLE symptoms and signs are caused by local inflammation in various organs that if left untreated may result in permanent organ damage.

The treatments to date are based on immunosuppressive regiments that nonspecifically inhibit the immune system. When intervening early on, before permanent damage occurs, these medications can be effective albeit with significant side effects. For skin and joint manifestations, the antimalarial hydroxychloroquine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and low to moderate doses of corticosteroids are often times sufficient. For moderately severe disease such as persistent skin rashes, pleuritis, severe arthritis, higher doses of corticosteroids are used with or without the introduction of an immunosuppressive medication such as methotrexate or azathioprine (24, 25). For the most severe life or organ-threatening manifestations (kidney, nervous system lupus), cytotoxic medications (cyclophosphamide) are used (22, 23). Clinical trials are ongoing for the use of less toxic medications such as mycophenolate mofetil in renal lupus (26, 27).

4. Clinical Laboratory Findings: A Window in the Pathogenesis of SLE

Studies of patients with SLE have shown that the above described clinical manifestations are caused by an exuberant immunological activation in the absence of a readily recognizable infectious agent. Both the humoral and cellular components of the immune system are activated. The serum of patients with SLE contains an array of antibodies that recognize self antigens and in particular nuclear antigens (reviewed in (28)). Some of these antibodies have been associated with specific manifestations of the disease; for example anti-dsDNA and anti-Sm antibodies are associated with nephritis (29), while anti-Ro antibody is associated with dry mouth (sicca) and neonatal lupus (20, 28). Some, but not all of these autoantibodies have been shown to cause damage. Examples include the antiplatelet antibodies that can reduce the number of platelets leading to bleeding (immune thrombocytopenia); the antiphospholipid antibodies directed against the components of the cell membrane that can mitigate platelet aggregation and thrombosis. It has to be noted that auto-antibodies can be found in the sera of patients with SLE long before the clinical manifestations of the disease, as shown in a study evaluating sera of military recruits who developed SLE (30). In this landmark study it was shown that auto-antibodies can be found in the serum of SLE patients long before the diagnosis is made. Importantly, there was a temporal progression of the autoantibody repertoire whereas antinuclear (ANA) antibodies appeared first, followed by anti-dsDNA and antiribonucleoprotein antibodies.

Another characteristic of the serum of patients with SLE is the low level of complement proteins C3 and C4; this is thought to be due to complement activation by immune complexes in the tissues and circulation. Importantly, in a significant number of patients (especially patients with nephritis), falling C3 and rising anti-dsDNA levels may predate clinical deterioration (31). These findings in the peripheral blood of patients with SLE show that there is a hyperactive B cell compartment of the immune system that produces autoantibodies against cellular components.

Several studies have addressed the nature of organ and tissue damage in SLE. Biopsies of the skin and the kidneys, two organs that are affected in a significant proportion of patients with SLE, have clearly shown that the components of the immune system, both cellular and humoral, are found in these target-organs. Skin biopsies in cutaneous lupus show a lymphocytic infiltration of the dermis and deposition of immunoglobulin and complement along the dermal–epidermal junction (32). Depending on the level of inflammation and the location of the infiltrating cells, various clinical manifestations ensue: acute superficial rashes, chronic discoid lesions, bullae formation or deep layer inflammation (panniculitis); oftentimes ulcers and scars form. Similarly, kidney studies have shown that lymphocytes infiltrate the interstitium while immunoglobulin (IgG, IgM, and IgA) and complement deposit in the glomeruli. The result of this inflammatory process is scarring of the glomerular tuft and tubular damage. Clinically these processes are manifested by leakage of protein and cells in the urine, and in the extreme cases by uremia (22, 23).

5. Etio-Pathogenesis: Integrating Genes, Environment and the Immune System

The epidemiological features, clinical manifestations and clinical laboratory findings have been invaluable in creating a model for the development of SLE and the propagation of the autoimmune response. The immunological abnormities that lead to SLE seem to start long before the clinical manifestations become apparent; genes, infections and environmental factors as well as hormones influence the development of the immune system in the early years of life, facilitating the emergence and activation of autoimmune lymphocytic clones.

Given the difficulties studying the preclinical phases of SLE at least in humans, most research efforts to understand the etio-pathogenesis of SLE have focused on two fronts:

The characterization of the immune deregulation in SLE and the identification of the key pathways involved in it.

The unraveling of the genetic background of patients with SLE and the potential role of these genes to disease pathology.

In the next sections, we will try to provide the links between SLE risk conferring genes and the immunological abnormalities found in patients with active disease. In addressing this issue, both intra- and intercellular signaling aberrations as well as changes in soluble mediators will be examined. It has to be noted that no single abnormality has been recognized to date as dominant in SLE but rather an array of signaling aberrations lead to the expression of the syndrome.

6. Cell Signaling: Auto-Reactivity, Deficient Regulation, and Inappropriate Activation

One of the first and the most significant susceptibility locus that has been found to be associated with SLE resides within the highly polymorphic major histo-compatibility complex (MHC) class II locus. In particular, Caucasians that have the DR2 (HLA-DRB1*1501) or DR3 (HLA-DRB1*0301) alleles have a two- to threefold increase in their relative risk to develop SLE; the risk conferred by these alleles though, is not as prominent in the other populations (33, 34). The MHC class II locus encodes proteins that are involved in antigen presentation to CD4+ T cells. Beyond being simply associated with SLE risk, certain MHC class II genes have been found to be associated with the production of specific autoantibodies. For example, MHC class II allele HLA-DRB1*03 was associated with the expression of anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies in patients with SLE (35). Similarly modest associations were found between HLA-DQA1*0601, and DQB*0201 with anti-Ro and HLA-DQA1*0501, and DQB*0201 with anti-La antibodies. Although certain clinical manifestations tend to be more prevalent in patients with these alleles, the associations between clinical picture and genotype are modest at best. Given these findings, it has been hypothesized that certain MHC class II molecules expressed on antigen-presenting cells (APC) of SLE patients may preferentially or aberrantly present certain (auto)-antigens to helper CD4+ T cells leading to abnormal T cell responses to antigenic stimuli that should have been ignored under normal conditions.

Indeed, multiple studies have shown that T cells that recognize and react against auto-antigens are present in the peripheral blood of patients with SLE. Among the self-antigens, the T cells from SLE patients have been shown to recognize histones, native DNA, and small nuclear ribonucleoproteins. These T cells are able to provide cognate help to B cells and lead to the production of potentially pathogenic anti-dsDNA auto-antibodies (36, 37).

In addition to auto-reactivity, T cells in SLE show a variety of signaling defects and abnormalities. Once the T cell receptor (TCR) is engaged, SLE T cells show a very robust and early influx of calcium and phosphorylation of Tyrosine residues on early signaling molecules (38). Two main reasons have been recognized as underlying the abnormal early signaling events of SLE T cells: Preaggregated lipid rafts (39) and the substitution of the CD3ζ chain by the FcεRIγ chain (40). The lipid rafts are platforms on the membrane of lymphocytes that help bring together all the important molecules that participate in the activation of the cells once their receptor has been engaged by its cognate ligand. In SLE T cells, as opposed to control T cells from healthy individuals and patients with other autoimmune diseases, the lipid rafts are already aggregated thus facilitating the early signaling events that lead to the influx of calcium and activation of kinases and phosphatases. In addition to the ready-made signaling platform, SLE T cells employ a different (rewired) (41) TCR/CD3 molecular complex that is more efficient in transducing the activating signal than the TCR/CD3 complex found in control nonactivated cells. Under normal conditions the main signaling molecule responsible for the transduction of the signal is the CD3ζ chain. SLE T cells have decreased CD3ζ chain levels and instead express in its place the FcεRIγ (40), a molecule initially recognized to be associated with the Fcε receptor on mast cells. This change results in the recruitment of Syk kinase instead of the Zap70 to the CD3 complex and leads to a more robust downstream signaling (41, 42). The expression of CD3ζ and Fc εRIγ are at least in part dictated by the activity of their respective genes, both of which are controlled by the transcriptional factor Elf-1: Elf-1 binding to its cis element on the CD3ζ promoter leads to gene transcription while it acts as a transcription repressor on the FcεRIγ gene. Elf-1 production is defective (43) in SLE T cells thus tilting the balance toward the production of FcεRIγ. Other mechanisms such as alternative splicing of the CD3ζ gene also contribute to the decreased CD3ζ chain levels in SLE T cells (44, 45).

In many respects, SLE T cells appear to be hyperactive, but nevertheless their ability to produce interleukin-2 (IL-2) upon activation is limited (46). IL-2 is a cytokine that is important for T cell activation, activation-induced cell death (AICD) and the survival of T regulatory cells (Treg). Its deficient production may therefore be linked to the prolonged survival of T cells (including auto-reactive cells) and insufficient inhibition of autoreactive processes by Treg (47, 48). Multiple transcription factors have to cooperate in order for the IL-2 gene to be transcribed. In SLE T cells the transcription activators NF-kB (49), AP-1 (a c-fos/c-jun dimer) (50) and p-CREB (51) are deficient while the transcription repressor CREM (52, 53) binds strongly to the promoter of IL-2. This combination of increased repressors and deficient activators is responsible for the inappropriately low production of IL-2 by activated SLE T cells.

The robust calcium flux once the T cell receptor is engaged does translate though into high NFAT (a calcium dependent transcription activator) translocation into the nucleus of T cells (54). NFAT because of deficiency of AP-1 does not stimulate the production of IL-2 but is able to bind to the promoter and stimulate the production of CD154 (also called CD40 ligand). CD154 is a costimulatory molecule that helps the T cells provide help to B cells therefore leading to the production of pathogenic auto-antibodies (55). In addition SLE T cells evade activation induced death (AICD) by yet another mechanism. These cells over-express cyclo-oxygenase 2 (Cox-2) (56), a molecule that facilitates their survival after activation.

Recently, it has been identified that SLE T cells upregulate CD44, a molecule that facilitates their migration in tissues such as the kidneys (57). There they produce proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-17 (58) that enables the recruitment of other immune cells and the propagation of the inflammatory process resulting in tissue damage.

Genetic studies have tried to shed light into the underlying causes for the aberrant function of SLE T cells. Of particular interest has been the observed association of SLE with genes encoding molecules that prevent or dampen T cell activation. One such molecule is the cytotoxic T cell antigen-4 (CTLA-4). CTLA-4 is similar in structure to CD28, which by binding to the CD80/86 molecules on APC augments T cell activation. CTLA-4 blocks the CD28:CD80/86 interaction by potently binding to the CD80/86 and at the same time delivers an inhibitory signal into the cell (59). Therefore CTLA-4 brings T cell activation to an end and induces a state of anergy. This function is an important check-point that prevents over-activation of the immune system and is thought to prevent autoimmune diseases by promoting long-lived anergy (60). Preliminary studies looking at several polymorphisms of the CTLA-4 gene showed that a T/C substitution at the −1,722 site is associated with SLE (61). Of note though, soluble CTLA-4 was shown to be increased in SLE patients, especially ones with active disease (62). More studies are therefore needed to address the potential role of CTLA-4 in SLE.

Another gene that encodes a negative regulator of T cell activation and has been associated with SLE is PTPN22. This gene encodes the lymphoid tyrosine phosphatase (LYP) that prevents T cell activation (63, 64). A missense polymorphism (R620W) (65) in the PTPN22 gene may impair the negative signaling transduced by LYP thus lowering the threshold for T cell activation.

The serum of patients with SLE contains various auto-antibodies, some of which have clear pathogenic capacity. These are produced by activated auto-reactive B cells, which are clearly abnormal. Although auto-reactive B cells are part of the immunological repertoire of normal individuals, SLE B cells show clear evidence of aberrant function possibly resulting during their maturation process. It has been shown that the peripheral B cell population in patients with active SLE has an increased number of CD127 high plasma cells and decreased number of naïve B cells (66). Looking even further at the naïve B cell population, a study of a limited number of young patients with SLE showed that a large proportion of B cells from these patients (up to 50%) are auto-reactive even before their first encounter with antigens (67). These studies suggest failure of important checkpoints in the maturation of B cells with the resulting survival of a higher number of auto-reactive B cells that may produce auto-antibodies as well as secrete cytokines and act as (auto)antigen-presenting cells. Given these findings, a recent report identifying the BLK/C8orf13 as a risk conferring area for SLE (68) is very interesting. BLK encodes for a src family tyrosine kinase that signals downstream to the B cell receptor. A polymorphism upstream of the BLK gene that in B cell lines led to the decreased production of BLK mRNA was associated with SLE. BLK is mainly found in immature B cells and therefore its decreased expression may affect B cell ontogeny (69). Under normal conditions, immature B cells that encounter and react to auto-antigens during their maturation process will undergo receptor editing or apoptosis (negative selection); these mechanisms prevent the emergence of auto-reactive B cells in the periphery. Immature B cells that recognize self-antigens but due to impaired signaling (as in the case of decreased BLK activity) do not undergo negative selection, will escape to the periphery.

Abnormal maturation and increased help from T cells cause multiple signaling aberrancies of SLE B cells. On the one hand, similar to T cells, SLE B cells upon the engagement of their receptor have increased tyrosine phosphorylation and intracellular calcium flux (70). On the other hand, inhibitory signaling such as via the Fc receptor FcγRIIb (a negative regulator of B cell receptor (BCR) signaling) are depressed (71). In addition, memory SLE B cells do not upregulate FcγRIIb as readily as controls (72). Genetic studies have shown an association of a polymorphism (FcγRIIb-232 I/T substitution) with SLE (33). The final result of this imbalance between inhibitory and activation signals in SLE B cells is augmented antibody production.

SLE B cells can also influence the function of T cells as they have been shown to produce antibodies that react with the CD3 molecule on T cells and activate the calcium and calmodulin dependent kinase IV (CaMKIV) (73) in these cells. In turn, CaMKIV causes binding of the repressor c-AMP response element modulator (CREM) to the IL-2 promoter, blocking the transcription of the gene.

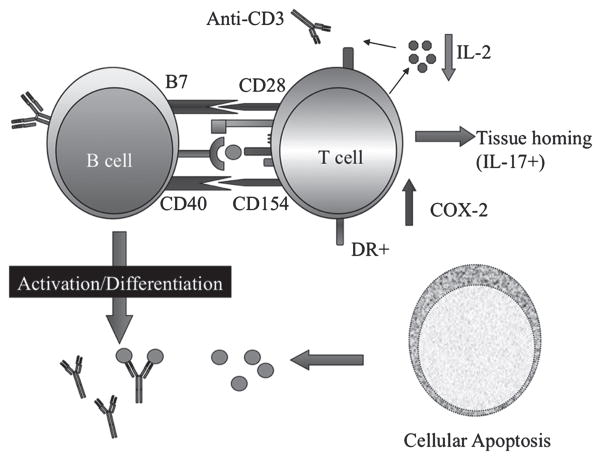

In summary, the hyperresponsive SLE B and T cells (see Fig. 1) contribute to the production of autoantibodies, cytokine imbalance and cell tissue infiltration that lead to the clinical manifestations of SLE.

Fig. 1.

Aberrant T:B cell cooperation in SLE. SLE T cells display an aberrant phenotype upon activation. They express persistently CD154 (CD40 ligand) that provides help to B cells and do not undergo readily activation-induced cell death due to the upregulation of cyclo-oxygenase 2 and deficient production of interleukin-2. At the same time, IL-17+ T cells infiltrate tissues and contribute to local inflammation. Impaired toleragenic mechanisms lead to the escape to the periphery of auto-reactive B cells, which are prone to produce autoantibodies with help by T cells. Apoptosis of cells (such as keratinocytes after UV exposure) leads to ample auto-antigen availability that is not handled appropriately by the reticulo-endothelial system. In turn, immune complexes containing autoantigens and autoantibodies deposit in tissues causing complement-mediated injury.

7. Humoral Factors: Apoptosis, the Complement System and Cytokines

Two of the most important findings in the serum of patients with SLE are the presence of various auto-antibodies and the decrease in the concentration of complement. Under normal conditions, natural auto-antibodies and complement are important as they play a major role in the clearance of auto-antigens contained in apoptotic material (74). It has been hypothesized that the appearance of auto-antibodies and the activation of complement seen in patients with SLE are a result of inappropriate cellular debris (waste) disposal (75). According to this theory, debris from cells that have undergone cellular death (by apoptosis or necrosis) is not handled correctly by the body with a resultant stimulation of autoantibody production, creation and tissue deposition of immune complexes, and complement activation leading to tissue damage.

This theory has been further strengthened by the fact that several complement components encoding genes have been associated with susceptibility to SLE. Individuals with deficiency in C1q, C2 or C4 have a much higher risk to develop SLE than control individuals. In the case of C1q deficiency, a very rare genetic trait, the rate of development of SLE is very high, approximately 90%. Similarly, 10% of patients who have a genetic deficiency in C2 develop SLE as well as up to 75% of patients with a complete lack of C4 (75–77). These observations point to the fact that complement is essential not only as a first line of defense against pathogens, but also is instrumental in averting the emergence of autoimmunity. Complement coats (opsonizes) auto-antigen:antibody complexes facilitating their removal from the circulation. This prevents the inappropriate presentation of auto-antigens to immune cells and emergence of autoimmunity (74) as is probably the case in SLE patients with complement deficiency.

Besides complement components of the classical pathway, SLE has also been associated with components of the lectin pathway of complement activation. More precisely a proportion of SLE patients have been shown to have deficiency of the mannose binding lectin (MBL) (78), a molecule that is similar to C1q in structure and function. Another study has associated polymorphisms in the promoter or coding region of MBL gene with SLE (79). The MBL pathway is crucial for the opsonization of bacteria and its deficiency in SLE may be important for both decreased antimicrobial vigilance (80) and the poor handling of auto-antigens.

Complement fragments C3b and C4b coating apoptotic material bind through the complement receptor 1 (CR1) (CD35) onto erythrocytes. An association between a structural variant of CR1 (CR1 S) and SLE in Caucasians has been suggested in a meta-analysis (75) of genetic studies in SLE; this observation suggests that even in patients with normal complement activity in the serum, slow removal of the immune complexes from the circulation may result in further immune activation of cells by the auto-antigens as well as the increased deposition of immune complexes in the tissues.

Cellular waste is also cleared by the cells of the reticulo-endothelial system (RES) mainly via the interaction of IgG with its receptor. IgG-coated auto-antigens (debris) bind to one or more of the various Fcγ receptors (FcγR) on the surface of the cells of the RES. The affinity of the FcγR for the different IgG subclasses can be influenced by the substitution of a single aminoacid in their extracellular domain. It is therefore not surprising that variants of the FcγR gene that result in changes of the aminoacid sequence of these chains are associated with altered binding to IgG. These subtle changes can in turn influence such important immune functions as phagocytosis, antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity (ADCC), and the clearance of immune complexes. Several studies have recognized the 1q23 region that contains the genes FCGR2A, FCGR3A, FCGR3B and FCGR2B which encode for low affinity IgG receptors as a susceptibility locus (33) for SLE.

FCGR2A has two codominant alleles that encode the different forms of FcγRIIa (CD32), a receptor found primarily on polymorphonuclear cells, mononuclear phagocytes and platelets. FcγRIIa binds IgG2 and C-reactive protein (CRP) (81). The two forms of FcγRIIa differ from each other by one single aminoacid at position 131. IgG2 binds stronger to the FcγRIIa that bears histidine at position 131 (H131) than to the molecule that has arginine at the same position (R131) (82). IgG2 is a poor activator of classical complement pathway and therefore its binding to the FcγRIIa is important for the clearance of immune complexes that contain IgG2. Multiple studies in different populations concluded that patients with the FcγRIIa-R131 polymorphism are at higher risk for SLE (33) but not nephritis (83, 84).

Altered CRP expression may independently or in conjunction with altered expression of FcγRIIa contribute to the development of SLE. Under normal conditions CRP is important for the disposal of cellular debris. In SLE, the defective expression of CRP may lead to deficient disposal of products of apoptosis making them available for presentation to T cells. SLE has been associated with a single nucleotide polymorphism (CRP-4) in the 3′ region of the CRP gene (85).

Similar to FCGR2A, FCGR3A has two codominant alleles that encode for two different forms of FcγRIIIa (CD16), a receptor expressed on natural killer (NK) and mononuclear cells. FcγRIIIa binds IgG1 and IgG3. The two forms of FcγRIIIa differ at position 176 with the one form having valine (V176) and the other phenylalanine (F176). The FcγRIIIa from individuals that are homozygous for the V176 form bind IgG1 and IgG3 more efficiently than FcγRIIIa from individuals homozygous for the F176 (82). A meta-analysis of data derived from 11 independent studies of the weaker FcγRIIIa-F176 form found a modest association with SLE (84).

Along the same lines SLE patients lacking the enzyme DNase I were reported (86). DNase I deficiency may lead to a decreased breakdown of DNA-protein complexes, eventually giving rise to immunological targeting of native DNA and its associated proteins.

These data suggest that proper waste handling fails at multiple levels in SLE with defective coating of the auto-antigens by complement and CRP and decreased binding to the Fc receptors.

Besides auto-antibodies and complement, the immune function in SLE is influenced by an array of cytokines that are aberrantly produced or missing (87). Genes encoding cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNFα) (88) and interleukin-10 (IL-10) (89) as well as the TNF receptor (90) have been associated with SLE. It has been shown that both IL-10 and TNF are aberrantly produced in SLE. More importantly though it has been found that peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) taken from SLE patients, especially ones with active disease, bear an interferon signature (91); in essence this means that genes that depend on type I interferons are activated in SLE patients. Genetic studies have shown that genetic polymorphisms of two genes that encode transcription factors related to interferon, STAT4 (T allele; rs7574865) (92) and IRF5 (T allele; rs2004640) (93) are associated with higher risk for development of SLE. Multiple inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6 are upregulated by these transcription factors (94). It is therefore plausible that the cells of SLE patients over-interpret interferon-mediated signals, such as those elicited by viral responses leading to the inappropriate activation of the immune system.

8. Conclusion

Genetic and functional studies have shown that SLE pathogenesis is complex. On the one hand, the failure of toleragenic mechanisms results in the generation of autoreactive immune cell clones. On the other hand, the deficient removal of apoptotic debris due to complement and/or Fc receptor abnormalities leads to the increased total burden of self-antigens. With these mechanisms in place, external stimuli are over- or mis-interpreted by the immune system, and result in aberrant antigen presentation, lymphocyte activation, and the production of an array of inflammatory cytokines. These in turn lead to tissue deposition of immune complexes, complement activation, and target-organ cell infiltration. Current and future trials aim at understanding the complex mechanisms in every step of SLE pathogenesis so that we may design more effective and less toxic therapeutic interventions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal and skin diseases grant No 1K23 AR055672-01A1

References

- 1.Krishnan S, Chowdhury B, Juang Y-T, Tsokos GC. Overview of the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. In: Tsokos GC, Gordon C, Smolen JS, editors. Systemic lupus erythematosus:acompaniontoRheumatology. 1. Mosby Inc; Philadelphia: 2007. pp. 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC, Deyo RA, Felson DT, Giannini EH, Heyse SP, Hirsch R, Hochberg MC, Hunder GG, Liang MH, Pillemer SR, Steen VD, Wolfe F. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:778–799. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199805)41:5<778::AID-ART4>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCarty DJ, Manzi S, Medsger TA, Jr, Ramsey-Goldman R, LaPorte RE, Kwoh CK. Incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus. Race and gender differences. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1260–1270. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siegel M, Lee SL. The epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1973;3:1–54. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(73)90034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nossent JC. Systemic lupus erythematosus on the Caribbean island of Curacao: an epidemiological investigation. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992;51:1197–1201. doi: 10.1136/ard.51.11.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vilar MJ, Sato EI. Estimating the incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus in a tropical region (Natal, Brazil) Lupus. 2002;11:528–532. doi: 10.1191/0961203302lu244xx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCarty DJ, Manzi S, Medsger TA, Jr, et al. Incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus. Race and gender differences. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1260–1270. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lahita RG. The role of sex hormones in systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1999;11:352–356. doi: 10.1097/00002281-199909000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Voulgari PV, Katsimbri P, Alamanos Y, Drosos AA. Gender and age differences in systemic lupus erythematosus. A study of 489 Greek patients with a review of the literature. Lupus. 2002;11:722–729. doi: 10.1191/0961203302lu253oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soto ME, Vallejo M, Guillen F, Simon JA, Arena E, Reyes PA. Gender impact in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2004;22:713–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tucker LB, Menon S, Isenberg DA. Systemic lupus in children: daughter of the Hydra? Lupus. 1995;4:83–85. doi: 10.1177/096120339500400201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mak SK, Lam EK, Wong AK. Clinical profile of patients with late-onset SLE: not a benign subgroup. Lupus. 1998;7:23–28. doi: 10.1191/096120398678919723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baker SB, Rovira JR, Campion EW, Mills JA. Late onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Med. 1979;66:727–732. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(79)91109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hochberg MC. The incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus in Baltimore, Maryland, 1970–1977. Arthritis Rheum. 1985;28:80–86. doi: 10.1002/art.1780280113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ward MM, Studenski S. Clinical manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Identification of racial and socioeconomic influences. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:849–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deapen D, Escalante A, Weinrib L, Horwitz D, Bachman B, Roy-Burman P, Walker A, Mack TM. A revised estimate of twin concordance in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:311–318. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Werth VP. Clinical manifestations of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun Rev. 2005;4:296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.James JA, Neas BR, Moser KL, Hall T, Bruner GR, Sestak AL, Harley JB. Systemic lupus erythematosus in adults is associated with previous Epstein-Barr virus exposure. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1122–1126. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200105)44:5<1122::AID-ANR193>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hochberg M. Updating the American College of Rheumatology Revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cervera R, Khamashta MA, Font J, Sebastiani GD, Gil A, Lavilla P, Domenech I, Aydintug AO, Jedryka-Goral A, de Ramon E, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus: clinical and immunologic patterns of disease expression in a cohort of 1, 000 patients. The European Working Party on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Medicine (Baltimore) 1993;72:113–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pons-Estel BA, Catoggio LJ, Cardiel MH, Soriano ER, Gentiletti S, Villa AR, Abadi I, Caeiro F, Alvarellos A, Alarcon-Segovia D. The GLADEL multinational Latin American prospective inception cohort of 1, 214 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: ethnic and disease heterogeneity among “Hispanics”. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004;83:1–17. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000104742.42401.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boumpas DT, Fessler BJ, Austin HA, III, Balow JE, Klippel JH, Lockshin MD. Systemic lupus erythematosus: emerging concepts. Part 2: dermatologic and joint disease, the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, pregnancy and hormonal therapy, morbidity and mortality, and pathogenesis. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:42–53. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-1-199507010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boumpas DT, Austin HA, III, Fessler BJ, Balow JE, Klippel JH, Lockshin MD. Systemic lupus erythematosus: emerging concepts. Part 1: renal, neuropsychiatric, cardiovascular, pulmonary, and hematologic disease. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:940–950. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-12-199506150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Maini M, Urowitz M. Systemic steroids. In: Tsokos GC, Gordon C, Smolen JS, editors. Systemic lupus erythematosus: a companion to Rheumatology. 1. Mosby Inc; Philadelphia: 2007. pp. 487–498. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Papadimitraki E, Boumpas DD. Cytotoxic drug treatment. In: Tsokos GC, Gordon C, Smolen JS, editors. Systemic lupus erythematosus: a companion to Rheumatology. 1. Mosby Inc; Philadelphia: 2007. pp. 498–510. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ginzler EM, Dooley MA, Aranow C, Kim MY, Buyon J, Merrill JT, Petri M, Gilkeson GS, Wallace DJ, Weisman MH, Appel GB. Mycophenolate mofetil or intravenous cyclophosphamide for lupus nephritis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2219–2228. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Houssiau FA, Ginzler EM. Current treatment of lupus nephritis. Lupus. 2008;17:426–430. doi: 10.1177/0961203308090029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sherer Y, Gorstein A, Fritzler MJ, Shoenfeld Y. Autoantibody explosion in systemic lupus erythematosus: more than 100 different antibodies found in SLE patients. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2004;34:501–537. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahman A, Hiepe F. Anti-DNA antibodies – overview of assays and clinical correlations. Lupus. 2002;11:770–773. doi: 10.1191/0961203302lu313rp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arbuckle MR, McClain MT, Rubertone MV, Scofield RH, Dennis GJ, James JA, Harley JB. Development of autoantibodies before the clinical onset of systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1526–1533. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Illei GG, Lipsky PE. Biomarkers in systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2004;6:382–390. doi: 10.1007/s11926-004-0013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jerdan MS, Hood AF, Moore GW, Callen JP. Histopathologic comparison of the subsets of lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:52–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsao BP. Update on human systemic lupus erythematosus genetics. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16:513–521. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000132648.62680.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Graham RR, Ortmann WA, Langefeld CD, Jawaheer D, Selby SA, Rodine PR, Baechler EC, Rohlf KE, Shark KB, Espe KJ, Green LE, Nair RP, Stuart PE, Elder JT, King RA, Moser KL, Gaffney PM, Bugawan TL, Erlich HA, Rich SS, Gregersen PK, Behrens TW. Visualizing human leukocyte antigen class II risk haplotypes in human systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:543–553. doi: 10.1086/342290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Galeazzi M, Sebastiani GD, Morozzi G, Carcassi C, Ferrara GB, Scorza R, Cervera R, de Ramon Garrido E, Fernandez-Nebro A, Houssiau F, Jedryka-Goral A, Passiu G, Papasteriades C, Piette JC, Smolen J, Porciello G, Marcolongo R. HLA class II DNA typing in a large series of European patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: correlations with clinical and autoantibody subsets. Medicine (Baltimore) 2002;81:169–178. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200205000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rajagopalan S, Zordan T, Tsokos GC, Datta SK. Pathogenic anti-DNA autoantibody-inducing T helper cell lines from patients with active lupus nephritis: isolation of CD4-8- T helper cell lines that express the gamma delta T-cell antigen receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7020–7024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.7020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shivakumar S, Tsokos GC, Datta SK. T cell receptor alpha/beta expressing double-negative (CD4−/CD8−) and CD4+ T helper cells in humans augment the production of pathogenic anti-DNA autoantibodies associated with lupus nephritis. J Immunol. 1989;143:103–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liossis SN, Ding XZ, Dennis GJ, Tsokos GC. Altered pattern of TCR/CD3-mediated protein-tyrosyl phosphorylation in T cells from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Deficient expression of the T cell receptor zeta chain. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1448–1457. doi: 10.1172/JCI1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krishnan S, Nambiar MP, Warke VG, Fisher CU, Mitchell J, Delaney N, Tsokos GC. Alterations in lipid raft composition and dynamics contribute to abnormal T cell responses in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2004;172:7821–7831. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Enyedy EJ, Nambiar MP, Liossis SN, Dennis G, Kammer GM, Tsokos GC. Fc epsilon receptor type I gamma chain replaces the deficient T cell receptor zeta chain in T cells of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1114–1121. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200105)44:5<1114::AID-ANR192>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsokos GC, Nambiar MP, Tenbrock K, Juang YT. Rewiring the T-cell: signaling defects and novel prospects for the treatment of SLE. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:259–263. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00100-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krishnan S, Warke VG, Nambiar MP, Tsokos GC, Farber DL. The FcR gamma subunit and Syk kinase replace the CD3 zeta-chain and ZAP-70 kinase in the TCR signaling complex of human effector CD4 T cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:4189–4195. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.4189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Juang YT, Tenbrock K, Nambiar MP, Gourley MF, Tsokos GC. Defective production of functional 98-kDa form of Elf-1 is responsible for the decreased expression of TCR zeta-chain in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2002;169:6048–6055. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.6048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chowdhury B, Tsokos CG, Krishnan S, Robertson J, Fisher CU, Warke RG, Warke VG, Nambiar MP, Tsokos GC. Decreased stability and translation of T cell receptor zeta mRNA with an alternatively spliced 3′-untranslated region contribute to zeta chain down-regulation in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18959–18966. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501048200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsuzaka K, Setoyama Y, Yoshimoto K, Shiraishi K, Suzuki K, Abe T, Takeuchi T. A splice variant of the TCR zeta mRNA lacking exon 7 leads to the down-regulation of TCR zeta, the TCR/CD3 complex, and IL-2 production in systemic lupus erythematosus T cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:3518–3525. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Linker-Israeli M, Bakke AC, Kitridou RC, Gendler S, Gillis S, Horwitz DA. Defective production of interleukin 1 and interleukin 2 in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) J Immunol. 1983;130:2651–2655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Valencia X, Yarboro C, Illei G, Lipsky PE. Deficient CD4 + CD25high T regulatory cell function in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2007;178:2579–2588. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miyara M, Amoura Z, Parizot C, Badoual C, Dorgham K, Trad S, Nochy D, Debre P, Piette JC, Gorochov G. Global natural regulatory T cell depletion in active systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2005;175:8392–8400. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.8392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Herndon TM, Juang YT, Solomou EE, Rothwell SW, Gourley MF, Tsokos GC. Direct transfer of p65 into T lymphocytes from systemic lupus erythematosus patients leads to increased levels of interleukin-2 promoter activity. Clin Immunol. 2002;103:145–153. doi: 10.1006/clim.2002.5192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kyttaris VC, Juang YT, Tenbrock K, Weinstein A, Tsokos GC. Cyclic adenosine 5′-monophosphate response element modulator is responsible for the decreased expression of c-fos and activator protein-1 binding in T cells from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2004;173:3557–3563. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Katsiari CG, Kyttaris VC, Juang YT, Tsokos GC. Protein phosphatase 2A is a negative regulator of IL-2 production in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3193–3204. doi: 10.1172/JCI24895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Solomou EE, Juang YT, Gourley MF, Kammer GM, Tsokos GC. Molecular basis of deficient IL-2 production in T cells from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2001;166:4216–4222. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.4216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tenbrock K, Juang YT, Gourley MF, Nambiar MP, Tsokos GC. Antisense cyclic adenosine 5′-monophosphate response element modulator up-regulates IL-2 in T cells from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2002;169:4147–4152. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kyttaris VC, Wang Y, Juang YT, Weinstein A, Tsokos GC. Increased levels of NF-ATc2 differentially regulate CD154 and IL-2 genes in t cells from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2007;178:1960–1966. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Desai-Mehta A, Lu L, Ramsey-Goldman R, Datta SK. Hyperexpression of CD40 ligand by B and T cells in human lupus and its role in pathogenic autoantibody production. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2063–2073. doi: 10.1172/JCI118643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu L, Zhang L, Yi Y, Kang HK, Datta SK. Human lupus T cells resist inactivation and escape death by upregulating COX-2. Nat Med. 2004;10:411–415. doi: 10.1038/nm1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li Y, Harada T, Juang YT, Kyttaris VC, Wang Y, Zidanic M, Tung K, Tsokos GC. Phosphorylated ERM is responsible for increased T cell polarization, adhesion, and migration in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2007;178:1938–1947. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Crispin JC, Oukka M, Bayliss G, Cohen RA, Van Beek CA, Stillman IE, Kyttaris VC, Juang YT, Tsokos GC. Expanded double negative T cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus produce IL-17 and infiltrate the kidneys. J Immunol. 2008;181:8761–8766. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baroja ML, Vijayakrishnan L, Bettelli E, Darlington PJ, Chau TA, Ling V, Collins M, Carreno BM, Madrenas J, Kuchroo VK. Inhibition of CTLA-4 function by the regulatory subunit of serine/threonine phosphatase 2A. J Immunol. 2002;168:5070–5078. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.5070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Salomon B, Bluestone JA. Complexities of CD28/B7: CTLA-4 costimulatory pathways in autoimmunity and transplantation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:225–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hudson LL, Rocca K, Song YW, Pandey JP. CTLA-4 gene polymorphisms in systemic lupus erythematosus: a highly significant association with a determinant in the promoter region. Hum Genet. 2002;111:452–455. doi: 10.1007/s00439-002-0807-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wong CK, Lit LCW, Tam LS, Li EK, Lam CWK. Aberrant production of soluble costimulatory molecules CTLA-4, CD28, CD80 and CD86 in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:989–994. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cloutier JF, Veillette A. Association of inhibitory tyrosine protein kinase p50csk with protein tyrosine phosphatase PEP in T cells and other hemopoietic cells. EMBO J. 1996;15:4909–4918. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cloutier JF, Veillette A. Cooperative inhibition of T-cell antigen receptor signaling by a complex between a kinase and a phosphatase. J Exp Med. 1999;189:111–121. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kyogoku C, Langefeld CD, Ortmann WA, Lee A, Selby S, Carlton VE, Chang M, Ramos P, Baechler EC, Batliwalla FM, Novitzke J, Williams AH, Gillett C, Rodine P, Graham RR, Ardlie KG, Gaffney PM, Moser KL, Petri M, Begovich AB, Gregersen PK, Behrens TW. Genetic association of the R620W polymorphism of protein tyrosine phosphatase PTPN22 with human SLE. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:504–507. doi: 10.1086/423790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sims GP, Ettinger R, Shirota Y, Yarboro CH, Illei GG, Lipsky PE. Identification and characterization of circulating human transitional B cells. Blood. 2005;105:4390–4398. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yurasov S, Wardemann H, Hammersen J, Tsuiji M, Meffre E, Pascual V, Nussenzweig MC. Defective B cell tolerance checkpoints in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Exp Med. 2005;201:703–711. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hom G, Graham RR, Modrek B, Taylor KE, Ortmann W, Garnier S, Lee AT, Chung SA, Ferreira RC, Pant PV, Ballinger DG, Kosoy R, Demirci FY, Kamboh MI, Kao AH, Tian C, Gunnarsson I, Bengtsson AA, Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S, Petri M, Manzi S, Seldin MF, Ronnblom L, Syvanen AC, Criswell LA, Gregersen PK, Behrens TW. Association of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus with C8orf13-BLK and ITGAM-ITGAX. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:900–909. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tretter T, Ross AE, Dordai DI, Desiderio S. Mimicry of pre-B cell receptor signaling by activation of the tyrosine kinase Blk. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1863–1873. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liossis SN, Kovacs B, Dennis G, Kammer GM, Tsokos GC. B cells from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus display abnormal antigen receptor-mediated early signal transduction events. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2549–2557. doi: 10.1172/JCI119073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Enyedy EJ, Mitchell JP, Nambiar MP, Tsokos GC. Defective FcgammaRIIb1 signaling contributes to enhanced calcium response in B cells from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Immunol. 2001;101:130–135. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mackay M, Stanevsky A, Wang T, Aranow C, Li M, Koenig S, Ravetch JV, Diamond B. Selective dysregulation of the Fc{gamma}IIB receptor on memory B cells in SLE. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2157–2164. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Juang YT, Wang Y, Solomou EE, Li Y, Mawrin C, Tenbrock K, Kyttaris VC, Tsokos GC. Systemic lupus erythematosus serum IgG increases CREM binding to the IL-2 promoter and suppresses IL-2 production through CaMKIV. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:996–1005. doi: 10.1172/JCI200522854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mevorach D, Mascarenhas JO, Gershov D, Elkon KB. Complement-dependent clearance of apoptotic cells by human macrophages. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2313–2320. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Manderson AP, Botto M, Walport MJ. The role of complement in the development of systemic lupus erythematosus. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:431–456. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ghebrehiwet B, Peerschke EI. Role of C1q and C1q receptors in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Dir Autoimmun. 2004;7:87–97. doi: 10.1159/000075688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Slingsby JH, Norsworthy P, Pearce G, Vaishnaw AK, Issler H, Morley BJ, Walport MJ. Homozygous hereditary C1q deficiency and systemic lupus erythematosus. A new family and the molecular basis of C1q deficiency in three families. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:663–670. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Senaldi G, Davies ET, Peakman M, Vergani D, Lu J, Reid KB. Frequency of man-nose-binding protein deficiency in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1713–1714. doi: 10.1002/art.1780381128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sullivan KE, Wooten C, Goldman D, Petri M. Mannose-binding protein genetic polymorphisms in black patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:2046–2051. doi: 10.1002/art.1780391214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Iliopoulos AG, Tsokos GC. Immunopathogenesis and spectrum of infections in systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1996;25:318–336. doi: 10.1016/s0049-0172(96)80018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bharadwaj D, Stein MP, Volzer M, Mold C, Du Clos TW. The major receptor for C-reactive protein on leukocytes is fcgamma receptor II. J Exp Med. 1999;190:585–590. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.4.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Salmon JE, Pricop L. Human receptors for immunoglobulin G: key elements in the pathogenesis of rheumatic disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:739–750. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200104)44:4<739::AID-ANR129>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Karassa FB, Trikalinos TA, Ioannidis JP. Role of the Fcgamma receptor IIa polymorphism in susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis: a meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:1563–1571. doi: 10.1002/art.10306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Karassa FB, Trikalinos TA, Ioannidis JP. The Fc gamma RIIIA-F158 allele is a risk factor for the development of lupus nephritis: a meta-analysis. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1475–1482. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Russell AI, Cunninghame Graham DS, Shepherd C, Roberton CA, Whittaker J, Meeks J, Powell RJ, Isenberg DA, Walport MJ, Vyse TJ. Polymorphism at the C-reactive protein locus influences gene expression and predisposes to systemic lupus erythematosus. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:137–147. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yasutomo K, Horiuchi T, Kagami S, Tsukamoto H, Hashimura C, Urushihara M, Kuroda Y. Mutation of DNASE1 in people with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2001;28:313–314. doi: 10.1038/91070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kyttaris VC, Juang YT, Tsokos GC. Immune cells and cytokines in systemic lupus erythematosus: an update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17:518–522. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000170479.01451.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wilson AG, Gordon C, di Giovine FS, de Vries N, van de Putte LB, Emery P, Duff GW. A genetic association between systemic lupus erythematosus and tumor necrosis factor alpha. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:191–195. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.D’Alfonso S, Rampi M, Bocchio D, Colombo G, Scorza-Smeraldi R, Momigliano-Richardi P. Systemic lupus erythematosus candidate genes in the Italian population: evidence for a significant association with interleukin-10. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:120–128. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200001)43:1<120::AID-ANR15>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Morita C, Horiuchi T, Tsukamoto H, Hatta N, Kikuchi Y, Arinobu Y, Otsuka T, Sawabe T, Harashima S, Nagasawa K, Niho Y. Association of tumor necrosis factor receptor type II polymorphism 196R with Systemic lupus erythematosus in the Japanese: molecular and functional analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:2819–2827. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200112)44:12<2819::aid-art469>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kirou KA, Lee C, George S, Louca K, Peterson MG, Crow MK. Activation of the interferon-alpha pathway identifies a subgroup of systemic lupus erythematosus patients with distinct serologic features and active disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1491–1503. doi: 10.1002/art.21031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Remmers EF, Plenge RM, Lee AT, Graham RR, Hom G, Behrens TW, de Bakker PIW, Le JM, Lee H-S, Batliwalla F, Li W, Masters SL, Booty MG, Carulli JP, Padyukov L, Alfredsson L, Klareskog L, Chen WV, Amos CI, Criswell LA, Seldin MF, Kastner DL, Gregersen PK. STAT4 and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:977–986. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Graham RR, Kozyrev SV, Baechler EC, Reddy MV, Plenge RM, Bauer JW, Ortmann WA, Koeuth T, Gonzalez Escribano MF, Pons-Estel B, Petri M, Daly M, Gregersen PK, Martin J, Altshuler D, Behrens TW, Alarcon-Riquelme ME. A common haplotype of interferon regulatory factor 5 (IRF5) regulates splicing and expression and is associated with increased risk of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2006;38:550–555. doi: 10.1038/ng1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Takaoka A, Yanai H, Kondo S, Duncan G, Negishi H, Mizutani T, Kano S, Honda K, Ohba Y, Mak TW, Taniguchi T. Integral role of IRF-5 in the gene induction programme activated by Toll-like receptors. Nature. 2005;434:243–249. doi: 10.1038/nature03308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]