Abstract

An enantioselective total synthesis of zampanolide has been accomplished using a novel DDQ/Brønsted acid catalyzed cyclization as the key reaction. The synthesis features cross-metathesis to construct the tri-substituted olefin and a ring-closing metathesis to form the macrolactone. The final N-acyl aminal formation was stereoselectively accomplished by an organocatalytic reaction.

The isolation of taxol in the 1970’s and subsequent decade-long studies led to the approval of paclitaxel as an important anticancer drug. 1 Paclitaxel inhibits cell division by stabilizing microtubule assembly.2 Since the discovery of this unique mechanism of action, the search for new agents has become the subject of immense interest. In recent years, epothilones and discodermolide-based antitumor therapeutics have received significant attention. 3 Also, laulimalide and pelorusides were identified as the exciting new generation of microtubule-stabilizing agents.4 Both laulimalide and pelorusides have exhibited intriguing synergistic effects with taxol, maintained potent activity against taxol-resistant cell lines and are not substrates for P-glycoprotein-mediated drug efflux pump.5,6 More recently, Northcote, Miller and co-workers reported that (−)-zampanolide 1 (Figure 1), a 20-membered macrolide also possesses potent microtubule-stabilizing properties.7

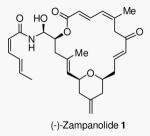

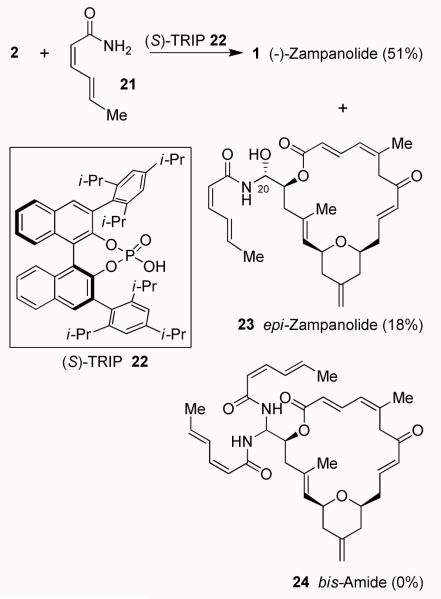

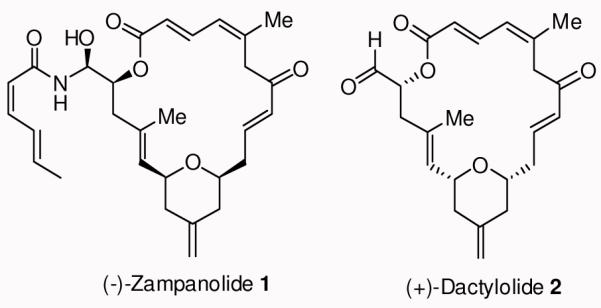

Figure 1.

(−)-Zampanolide 1 (natural form) and (+)-dactylolide 2 (enantiomer of natural form)

Zampanolide (1) was originally isolated by Tanaka and Higa from the marine sponge Fasciospongia rimosa in Okinawa in 1996.8 More recently, (−)-zampanolide 1 was isolated from a Tongan marine sponge, Cacospongia mycofijiensis, and reported to block cell division in the G2/M of the cell cycle.7 Uenishi and co-workers reported potent cytotoxic activity of (−)-zampanolide against SKM-1 and U937 cell lines with IC50 values of 1.1 and 2.9 nM respectively.9 Furthermore, it is potent against HL-60, 1A9 cells and especially against A2780AD which is quite resistant to paclitaxel.7 Zampanolide’s natural abundance is very scarce which has resulted in only limited biological studies. Zampanolide possesses a unique unsaturated macrocyclic structural feature containing only three stereogenic centers and a chiral N-acyl aminal side chain.

The chemistry and biology of zampanolide has attracted much synthetic attention. Smith and co-workers achieved the first total synthesis of (+)-zampanolide, the unnatural antipode, in 2001.10 Subsequently, both Hoye et al. in 200311 and Uenishi et al.9 in 2009, reported the total synthesis of natural (−)-zampanolide. These syntheses established that the natural (−)-zampanolide core is the opposite enantiomer of the related natural product (+)-dactylolide (2). Dactylolide displayed only modest cytotoxicity. Since its discovery by Riccio and co-workers in 2001 12, a number of total syntheses13,14,15,16,17,18,19 and a synthetic approach to (+)-dactylolide have been reported.20 It appears that the N-acyl aminal side chain of (−)-zampanolide is important for its potent cytotoxic properties. The key N-acylation reaction typically9 provided only 12% yield of zampanolide along with its epimer and bis-acylated product, suggesting that an improvement is necessary for the synthesis of structural variants. Herein, we report an enantioselective synthesis of (−)-zampanolide that can be amenable to the synthesis of N-acyl aminal derivatives.

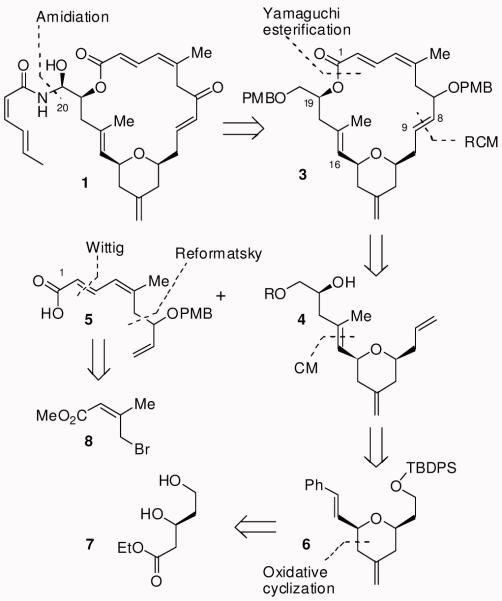

Our synthetic strategy for (−)-zampanolide (1) is shown in Figure 2. We planned to synthesize the macrocyclic core in a convergent manner in order to prepare a variety of structural analogs. Our strategic bond disconnection of the sensitive N-acyl aminal side chain at C20 provides macrolactone 3, which can be formed from alcohol 4 and acid 5 by esterification followed by a ring-closing metathesis. A similar RCM strategy was first employed by Hoye and Hu.11 The tri-substituted olefin in 4 would be installed by a cross metathesis of 6. The tetrahydropyran ring 6 would be constructed by an oxidative cyclization reaction of a cinnamyl ether derived from β-hydroxy ester 7. The polyene carboxylic acid 5 would be assembled by a Reformatsky reaction with γ-bromo unsaturated ester 8 followed by Wittig olefination of the corresponding aldehyde.

Figure 2.

Synthetic plan for (−)-Zampanolide 1

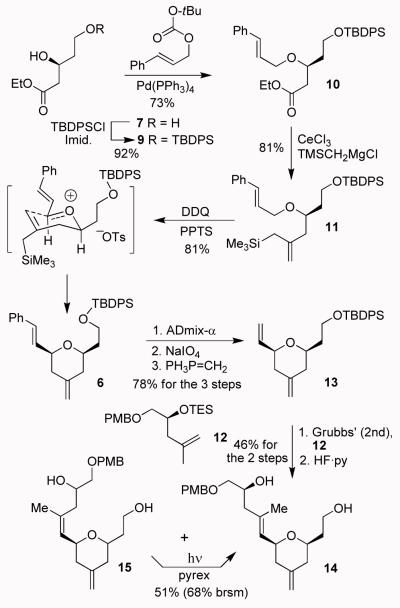

As shown in Scheme 1, the synthesis commenced with known ester 7, which was readily prepared with excellent enantioselectivity using Noyori hydrogenation as the key step.21 Selective protection of the primary alcohol as a TBDPS ether provided 9. Etherification of the secondary alcohol with t-butyl cinnamyl carbonate in the presence of a catalytic amount of Pd(PPh3)4 afforded cinnamyl ether 10 in 73% yield. The ethyl ester 10 was converted to allylsilane 11 by employing a modified procedure of Narayanan and Bunnelle to provide 11 in 81% yield.22 Our subsequent plan was to carry out an oxidative Sakurai type cyclization to construct the 4-methylenetetrahydro-2H-pyran ring stereoselectively. For this transformation, we initially explored an oxidative cyclization reaction with DDQ as benzylic/allylic ethers have been converted to carbocation intermediates using DDQ with or without Lewis acids by Mukaiyama and Hayashi,23 She et al.,24 and Floreancig and co-workers.25 The reaction with DDQ at −40 °C for 3 days resulted in only 30-35% desired product 6 along with unidentified side products possibly due to the presence of the allylsilane functionality. The same reaction in the presence of a variety of Lewis acids also provided similar results. However, oxidative cyclization with DDQ in the presence of a mild Brønsted acid such as PPTS provided the best results. Reaction of 11 with 1.5 equiv of DDQ and 1.5 equiv of PPTS at −38 °C in acetonitrile for 3 h afforded 6 in 81% yield as a single diastereomer (by 1H-NMR analysis). The NOESY data fully corroborated the depicted cis-stereochemistry of 6. Presumably, the cyclization proceeded through a Zimmerman-Traxler transition state where all substituents are equatorially oriented.26

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of tetrahydropyran 14

Our synthetic strategy then called for the elaboration of the E-trisubstituted olefin in 4 by a cross-metathesis reaction. The corresponding olefin substrate 12 was obtained in optically active form by opening of PMB-protected glycidyl derivative with isopropenylmagnesium bromide followed by protection of the resulting alcohol as TES-ether. Our attempted cross-metathesis of 6 with 12 under a variety of conditions did not provide any cross-metathesis product. Assuming the lack of reactivity of the styrene chain, we planned to convert the styrene chain into a methylene chain. This was achieved by selective dihydroxylation of the styrene chain with ADmix-α followed by diol cleavage with NaIO4 to provide the corresponding aldehyde as described by Smith and Dong.27 Wittig olefination of the resulting aldehyde with methylene phosphorane afforded 13 in 78% yield (3 steps). Cross-metathesis28 of 13 with 12 using Grubbs’ second generation catalyst (10 mol %) in CH2Cl2 at reflux for 9 h provided E/Z olefin mixture (1.7:1) in 57% yield. The mixture was treated with HF·py to remove all silyl groups. The resulting alcohols were separated by silica gel chromatography. Photochemical isomerization of the Z-isomer 15 provided a 51% yield (68% brsm) of tri-substituted olefin 14.

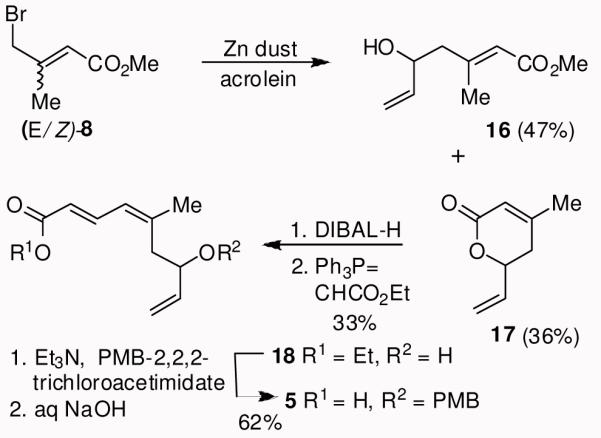

The synthesis of polyene carboxylic acid 5 is shown in Scheme 2. Allyl bromide 8 was prepared as an E/Z mixture (1.3:1) using the procedure of Fallis and Lei.29 Reformatsky reaction of the mixture of bromides 8 with acrolein resulted in allylic alcohol 16 (47% yield) and unsaturated δ-lactone 17 (36% yield) after separation by silica gel chromatography. DIBAL-H reduction followed by Wittig reaction with (carbethoxymethylene)triphenylphosphorane afforded allylic alcohol 18. Protection of the resulting alcohol as a PMB-ether followed by saponification of the ester provided acid 5 in 62% yield (2 steps).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of polyene carboxylic acid 5

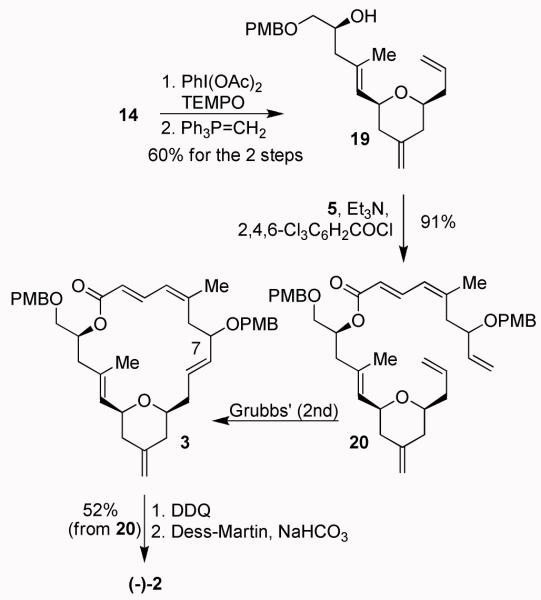

The synthesis of macrolactone 3 is shown in Scheme 3. The primary alcohol in 14 was selectively oxidized with TEMPO in the presence of PhI(OAc)2. The resulting aldehyde was subjected to Wittig olefination with methylenetriphenylphosphorane to provide 19 in 60% yield (2 steps). Esterification of acid 5 with alcohol 19 under Yamaguchi conditions using 2,4,6-trichlorobenzoyl chloride and DMAP furnished ester 20 in 91% yield. Ring-closing metathesis using Grubbs’ second generation catalyst (12 mol %) in benzene at 60 °C for 20 h afforded 3 as a mixture (1:1) of diastereomers at the C7 chiral center. Removal of both PMB-ethers by treatment with DDQ provided the corresponding diol. Dess-Martin oxidation of the diol furnished (−)-2, the unnatural antipode of dactylolide (52% for the 3 steps).

Scheme 3.

The synthesis of (−)-2

The conversion of (−)-2 to (−)-zampanolide 1 required the addition of a carboxamide to the aldehyde to form a N-acyl aminal. Such direct addition in one previous synthesis9 afforded only 12% yield of (−)-zampanolide, 12% yield of epimeric product 23 and 16% yield of bis-amide 24. In an effort to improve this reaction, we investigated Brønsted acid-catalyzed N-acyl aminal formation under a variety of reaction conditions. In one of our initial successful attempts, reaction of (−)-2 with carboxamide 21 in the presence of diphenylphoshoric acid clearly provided a mixture of all three products, (−)-zampanolide, epi-zampanolide, and bis-amide 24, although analysis of the mixture showed that (−)-zampanolide formation was favored slightly. Encouraged by this result, we then investigated N-acyl aminal formation between aldehyde (−)-2 and amide 21 in the presence of matched chiral phosphoric acid (S)-TRIP30,31 (22, 20 mol %) at 23 °C for 12 h. These reaction conditions provided excellent chemoselectivity towards mono addition and the formation of bis-amide 24 was not observed. The reaction furnished (−)-zampanolide in 51% yield and epi-zampanolide 23 in 18% yield after separation/purification by HPLC. We have also investigated the corresponding mismatched reaction with (R)-TRIP, however, this reaction afforded a 1:1 mixture of (−)-1 and epi-1. Again, the formation of bis-amide 24 was not observed. The spectral data (1H NMR and 13C NMR) of synthetic 1 ([α]22D - 94, c 0.08, CH2Cl2) is in agreement with that of natural zampanolide (Lit.8 [α]22D - 101, c 0.12, CH2Cl2).

In summary, we have accomplished an enantioselective synthesis of (−)-zampanolide. The synthesis features a novel intramolecular oxidative cyclization reaction, a cross-metathesis reaction to construct a tri-substituted olefin, a ring-closing metathesis to form a highly functionalized macrolactone, and a chiral phosphoric acid catalyzed stereoselective N-acyl aminal formation that stereoselectively furnished (−)-zampanolide and no bis-amide byproduct. The present synthesis is amenable to the synthesis of structural variants of (−)-zampanolide and further investigations of important analogs are in progress.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 4.

The synthesis of (−)-Zampanolide

Acknowledgment

This research is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- (1).Pazdur R, Kudelka AP, Kavanagh JJ, Cohen PR, Raber MN. Cancer Treat. Rev. 1993;19:351–386. doi: 10.1016/0305-7372(93)90010-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Schiff PB, Fant J, Horwitz SB. Nature. 1979;277:665–667. doi: 10.1038/277665a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Mani S, Macapinlac MJ, Goel S, Verdier-Pinard D, Fojo T, Rothenberg M, Colevas D. Anti-cancer Drugs. 2004;15:553–558. doi: 10.1097/01.cad.0000131681.21637.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Hamel E, Day BW, Miller JH, Jung MK, Northcote PT, Ghosh AK, Curan DP, Cushman M, Nicolaou KC, Paterson I, Sorenson EJ. J. Mol. Phamacology. 2006;70:1555–1564. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.027847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Gapud EJ, Bai R, Ghosh AK, Hamel E. Mol. Pharmacology. 2004;66:113–121. doi: 10.1124/mol.66.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Hood KA, West LM, Rouwe B, Northcote PT, Berridge MV, Wakefield SJ, Miller JH. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3356–3360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Field JJ, Singh AJ, Kanakkanthara A, Halafihi T, Northcote PT, Miller JH. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:7328–7332. doi: 10.1021/jm901249g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Tanaka J, Higa T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:5535–5538. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Uenishi J, Iwamoto T, Tanaka J. Org. Lett. 2009;11:3262–3265. doi: 10.1021/ol901167g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Smith AB, III, Safonov IG, Corbett RM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:12426–12427. doi: 10.1021/ja012220y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Hoye TR, Hu M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:9576–9577. doi: 10.1021/ja035579q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Cutignano A, Bruno I, Bifulco G, Casapullo A, Debitus C, Gomez-Paloma L, Riccio R. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2001:775–778. doi: 10.1021/np010053+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Smith AB, III, Safonov IG, Corbett RM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:11102–11113. doi: 10.1021/ja020635t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Ding F, Jennings MP. Org. Lett. 2005;7:2321–2324. doi: 10.1021/ol0504897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Aubele DL, Wan S, Floreancig PE. Angew. Chem. 2005;117:3551–3554. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:3485–3488. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Sanchez CC, Keck GE. Org. Lett. 2005;7:3053–3056. doi: 10.1021/ol051040g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Louis I, Hungerford NL, Humphries EJ, McLeod MD. Org. Lett. 2006;8:1117–1120. doi: 10.1021/ol053092b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Zurwerra D, Gertsch J, Altmann K-H. Org. Lett. 2010;12:2302–2305. doi: 10.1021/ol100665m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Yun SY, Hansen EC, Volchkov I, Cho EJ, Lo WY, Lee D. Angew. Chem. 2010;122:4357–4359. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:4261–4263. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Troast DM, Yuan J, Porco JA., Jr Adv. Synth. Catal. 2008;350:1701–1711. doi: 10.1002/adsc.200800247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Kitamura M, Ohkuma T, Inoue S, Sayo N, Kumobayashi H, Akutagawa S, Ohta T, Takaya H, Noyori R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:629–631. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Narayanan BA, Bunnelle WH. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:6261–6264. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Hayashi Y, Mukaiyama T. Chem. Lett. 1987:1811–1814. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Yu B, Jiang T, Li J, Su Y, Pan X, She X. Org. Lett. 2009;11:3442–3445. doi: 10.1021/ol901291w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Tu W, Liu L, Floreancig PE. Angew. Chem. 2008;120:4252–4255. [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:4184–4187. doi: 10.1002/anie.200706002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Zimmerman HE, Traxler MD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957;79:1920–1923. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Smith AB, III, Dong S. Org. Lett. 2009;11:1099–1102. doi: 10.1021/ol802942j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Chatterjee AK, Choi T-L, Sanders DP, Grubbs RH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:11360–11370. doi: 10.1021/ja0214882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Lei B, Fallis AG. Can. J. Chem. 1991;69:1450–1456. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Hoffmann S, Seayad AM, List B. Angew. Chem. 2005;117:7590–7593. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int.Ed. 2005;44:7424–7427. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Akiyama T. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:5744–5758. doi: 10.1021/cr068374j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.