Abstract

BACKGROUND

Guidelines recommend lifelong anticoagulation in patients with cancer and a history of thromboembolism, but the use of anticoagulation in hospice has not been described. A retrospective study of medication data was conducted to determine patterns of anticoagulant use and predictors of type of anticoagulant prescribed for hospice patients with lung cancer.

METHODS

Medication data were evaluated for 16,896 hospice patients with lung cancer in 2006 to determine patient and hospice characteristics that predicted anticoagulant prescription. Independent predictors of warfarin versus low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) prescription were identified using a logistic regression model.

RESULTS

One of every 11 patients was prescribed an anticoagulant, most commonly warfarin. Compared with patients prescribed LMWH, patients prescribed warfarin were older (71.6 vs 65.8 years, P<.001), were more likely white (81.2% vs 74.3%, P = .03), had a longer stay in hospice (median 21 days vs 17 days, P = .001), and were more likely to have ≥3 comorbid illnesses (37.5% vs 25.0%, P<.001). The strongest independent predictor of type of anticoagulant prescribed was geographic region, with hospices in the Northeast more likely to prescribe LMWH.

CONCLUSIONS

Anticoagulant use is prevalent in patients with lung cancer enrolled in hospice. This study highlights the need to understand the benefits and risks of anticoagulation at the end of life.

Keywords: anticoagulants, hospice care, drug interactions, neoplasms, thromboembolism

Patients with advanced cancer enrolled in hospice are at high risk of venous thromboembolism, usually because of older age, advanced or metastatic disease, and decreased mobility.1 Approximately 10% of patients with cancer who are treated in palliative care units are diagnosed with symptomatic thromboembolism,2 and more than half of patients in inpatient hospice units are believed to have asymptomatic deep venous thrombosis.3

Guidelines advocate lifelong anticoagulation in patients with current thromboembolism or a history of thromboembolism and active cancer.4–6 Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is preferred over warfarin because of evidence of the superiority of LMWH in preventing recurrent thromboembolic disease in patients with cancer.7

Guidelines for the use of anticoagulants in cancer suggest benefit in select patients receiving palliative care.5 A proposed benefit of anticoagulation in hospice care, where the goal is promoting quality of life rather than lengthening survival, is that treatment may reduce bothersome symptoms of thromboembolism such as pain, edema, and dyspnea.1 However, no studies of adequate size have been conducted to definitively determine the effect of anticoagulation on symptoms or survival in hospice patients.8

The use of anticoagulants in the context of palliative care is challenging for several reasons: 1) the unknown effect on quality of life; 2) uncertain risk of discontinuing anticoagulation; 3) risk of bleeding, which is increased with renal failure and malnutrition; 4) numerous drug interactions with warfarin; 5) high burden associated with more intense patient monitoring; and 6) direct and indirect costs that strain patients and hospice providers who are reimbursed by a fixed hospice benefit.9 Although palliative care practitioners and patients are increasingly accepting of anticoagulation in theory,10,11 to our knowledge, actual anticoagulant use at the end of life has not been described previously.

The purpose of this study was to determine patterns of anticoagulant use and the predictors of the type of anticoagulant prescribed for hospice patients with lung cancer. We chose to evaluate patients with lung cancer because they make up the largest group with cancer who enroll in hospice annually and have a high risk of venous thromboembolism, increased 4-fold in metastatic disease.12,13

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Source of Data

Data for this study were obtained from excelleRx, operating as Hospice Pharmacia, a national hospice pharmacy provider that manages medication therapy for >800 hospice organizations in the United States. Patients served by Hospice Pharmacia are similar in demographic and clinical characteristics to samples from the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization as well as the National Home and Hospice Care Survey.14 Data from this provider have been described in more detail elsewhere.14,15 We obtained data on medication use for 65,106 persons with a terminal diagnosis of cancer who enrolled in hospice and died during the period of January 1, 2006, through December 31, 2006. Demographic and clinical data, including primary diagnosis and other medical conditions, were collected by hospice staff at admission into hospice care. Medication data were collected by hospice staff as part of routine clinical care and reported to the hospice pharmacy provider during encounters between hospice staff and pharmacy staff.

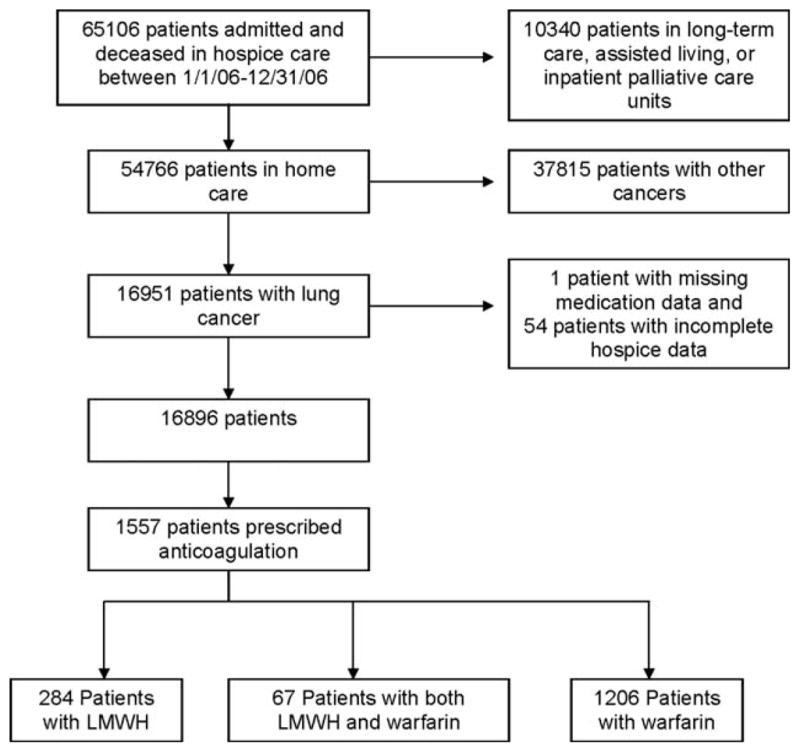

Our target population included patients with lung cancer who received hospice care in the home. We excluded patients who received hospice care in long-term care and assisted living settings or inpatient palliative care units (n = 10,340) because of known inconsistencies in medication data reporting. We also excluded patients with cancers other than lung cancer (n = 37,815). In addition, 1 patient with missing medication data and 54 patients with incomplete hospice data were excluded. Our study sample was comprised of 16,896 patients with lung cancer who received hospice care in the home. The derivation of the study sample is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The derivation of the study sample is shown. LMWH indicates low molecular weight heparin.

This study was approved by The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center’s institutional review board with waiver of informed consent.

Measures

Patient and hospice variables were evaluated to predict the frequency of warfarin versus LMWH prescription. Patient variables included age, sex, race, length of stay in hospice, number of medications, and comorbid illnesses. Comorbid illnesses were derived from the indications for each medication as coded by Hospice Pharmacia staff, and were only included for analysis if the diagnosis was included in Elixhauser’s method.16 Hospice variables included zip codes (to categorize hospices according to region) and average daily census (to classify hospices according to size). Potential clinically significant drug interactions (those that require monitoring, dose change, or alternative therapy to realize a benefit or to minimize risk from use17) were also identified for patients prescribed warfarin or LMWH.

Statistical Analysis

Patient and hospice variables were compared between hospice patients who were prescribed anticoagulants and those who were not, and subsequently between those who were prescribed warfarin and those who were prescribed LMWH. Variables were compared using the chi-square test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables. A multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to determine predictors of the dichotomous outcome of warfarin as opposed to LMWH prescription. P values <.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Of 16,896 patients with lung cancer who received hospice care in the home, 1557 (9.2%) were prescribed ≥1 anticoagulants. Table 1 shows the comparison of patients who were prescribed anticoagulants versus those who were not. The anticoagulant group was younger, was more likely white, had a longer stay in hospice, took more concurrent medications, had more comorbid illnesses, and was more likely to be enrolled in a small- or medium-sized hospice. All of these differences were statistically significant.

Table 1.

Comparison of Characteristics of Patients With Lung Cancer Who Were Prescribed Anticoagulants With Those of Patients Who Were Not

| Patient Characteristic | Patientsa Prescribed Anticoagulants,b n = 1557 [9.20%] | Patientsa Not Prescribed Anticoagulants, n = 15,339 [90.80%] | Pc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, y (±SD) | 70.3 (±11.3) | 71.1 (±11.1) | .03 |

| Sex, No. (%) | |||

| Women | 680 (43.7) | 7004 (45.7) | .13 |

| Men | 877 (56.3) | 8335 (54.3) | |

| Race, No. (%) | |||

| White | 1244 (79.9) | 11,952 (77.9) | .048 |

| Black | 104 (6.7) | 1190 (7.8) | |

| Hispanic | 24 (1.5) | 378 (2.5) | |

| Other | 185 (11.9) | 1819 (11.9) | |

| Mean length of stay, d (median) | 40.4 (20.0) | 35.9 (16.0) | <.0001 |

| Mean No. of medications (±SD) | 15.6 (±5.7) | 12.4 (±6.1) | <.0001 |

| No. of comorbidities, No. (%) | |||

| <3 | 1018 (65.4) | 12,560 (81.9) | <.0001 |

| ≥3 | 539 (34.6) | 2779 (18.1) | |

| Hospice location, No. (%) | |||

| Northeast | 317 (20.4) | 3382 (22.1) | |

| South | 667 (42.8) | 6385 (41.6) | .42 |

| West | 203 (13.0) | 2046 (13.3) | |

| Midwest | 370 (23.8) | 3526 (23.0) | |

| Hospice size, No. (%)d | |||

| Very small (<26) | 227 (14.6) | 2512 (16.4) | |

| Small (26–100) | 664 (42.7) | 6314 (41.2) | .04 |

| Medium (101–500) | 608 (39.1) | 5759 (37.5) | |

| Large (501–782) | 58 (3.7) | 754 (4.9) | |

SD indicates standard deviation.

Unless otherwise specified.

Anticoagulants included warfarin, low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) (dalteparin, enoxaparin, and tinzaparin and the Factor Xa inhibitor fondaparinux), and combination warfarin and LMWH.

Differences in the proportions between the 2 groups were tested using the chi-square test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables.

Based on average daily census.

Among patients who were prescribed anticoagulants, 1206 (77.5%) were prescribed warfarin only, and 284 (18.2%) were prescribed LMWH only; 67 (4.3%) patients were prescribed both warfarin and LMWH during their hospice stay and were not included in comparisons between the anticoagulant groups. Table 2 compares characteristics according to anticoagulant group. Patients prescribed warfarin were older, were more likely white, had a longer stay in hospice, and had more comorbid illnesses. These differences were all statistically significant. There were also significant between-group differences in distribution according to US region and hospice size, with a higher percentage of LMWH patients in the Northeast and enrolled in small- or medium-sized hospices.

Table 2.

Comparison of Patients With Lung Cancer Who Were Prescribed Warfarin or LMWH

| Patient Characteristic | Patientsa Who Were Prescribed LMWH,b n = 284 [19.1%]c | Patientsa Who Were Prescribed Warfarin, n = 1206 [80.9%]c | Pd |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (±SD), y | 65.8 (±11.5) | 71.6 (±10.9) | <.0001 |

| Sex | |||

| Women | 132 (46.5) | 519 (43.0) | .29 |

| Men | 152 (53.5) | 687 (57.0) | |

| Race | .03 | ||

| White | 211 (74.3) | 979 (81.2) | |

| Black | 25 (8.8) | 73 (6.1) | |

| Hispanic | 3 (1.1) | 21 (1.7) | |

| Other | 45 (15.9) | 133 (11.0) | |

| Mean length of stay, d (median) | 28.7 (17.0) | 42.0 (21.0) | .001 |

| Mean No. of medications (±SD) | 15.2 (±6.0) | 15.6 (±5.6) | .32 |

| No. of patients with drug interactions (%) | 0 (0.0) | 344 (28.5) | <.0001e |

| No. (%) of comorbidities | |||

| <3 | 213 (75.0) | 754 (62.5) | <.0001 |

| ≥3 | 71 (25.0) | 452 (37.5) | |

| Hospice location | |||

| Northeast | 89 (31.3) | 215 (17.8) | |

| South | 98 (34.5) | 537 (44.5) | <.0001 |

| West | 41 (14.4) | 155 (12.9) | |

| Midwest | 56 (19.7) | 299 (24.8) | |

| Hospice sizef | |||

| Very small (<26) | 30 (10.6) | 191 (15.8) | |

| Small (26–100) | 126 (44.4) | 510 (42.3) | .02 |

| Medium (101–500) | 123 (43.3) | 454 (37.7) | |

| Large (501–782) | 5 (1.8) | 51 (4.2) | |

| Indication for anticoagulation | |||

| AF | 3 (1.1) | 178 (14.8) | |

| DVT and/or PE | 226 (79.6) | 7 (0.6) | |

| Thrombosis | 50 (17.6) | 961 (79.7) | <.0001e |

| AF and thrombosis, DVT, or PE | 0 (0.0) | 32 (2.7) | |

| Other | 5 (1.8) | 28 (2.3) | |

LMWH indicates low molecular weight heparin; SD, standard deviation; AF, atrial fibrillation; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism.

Unless otherwise specified.

LMWH (dalteparin, enoxaparin, and tinzaparin) and the Factor Xa inhibitor fondaparinux.

Percentages were based on 1490 patients who were prescribed LMWH or warfarin; 67 patients were prescribed both warfarin and LMWH during their hospice stay and were not included in the comparisons between the anticoagulant groups.

Differences in the proportions between the 2 groups were tested using the chi-square test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables.

Fisher exact test was used.

Based on average daily census.

Table 3 shows the results of the logistic regression model that included patient and hospice variables to evaluate factors independently associated with warfarin versus LMWH prescription. Older patients and patients with a longer hospice stay were significantly more likely to be prescribed warfarin. Patients in hospices in the Northeast were significantly more likely to be prescribed LMWH. A similar model was constructed that excluded patients who were prescribed anticoagulants for atrial fibrillation, and the odds ratios for individual predictors remained nearly the same (data not shown).

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Model Showing the Odds of Being Prescribed Warfarin as Opposed to LMWHa for Patients With Lung Cancer in Hospice Careb

| Patient Characteristic | OR for Warfarin Prescription | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.047 | 1.034–1.060 |

| Sex, women vs men | 0.918 | 0.698–1.207 |

| Race (white used as reference) | ||

| Black | 0.644 | 0.388–1.068 |

| Hispanic | 2.096 | 0.595–7.375 |

| Other | 0.649 | 0.439–0.960 |

| Hospice location | ||

| South vs Northeast | 2.565 | 1.807–3.640 |

| West vs Northeast | 1.619 | 1.040–2.522 |

| Midwest vs Northeast | 2.597 | 1.751–3.853 |

| Length of stay, d | 1.006 | 1.002–1.010 |

| No. of medications | 0.993 | 0.967–1.019 |

| Hospice sizec | 1.000 | 0.999–1.001 |

LMWH indicates low molecular weight heparin; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

LMWH was used as a reference.

Model was based on 1490 patients who were prescribed either LMWH (284 patients) or warfarin (1206 patients); 67 patients were prescribed both warfarin and LMWH during their hospice stay and were not included in the comparisons between the anticoagulant groups.

Based on average daily census.

A potential for significant drug interactions was identified in 28.5% of the patients prescribed warfarin and none of the patients prescribed LMWH. Table 4 lists the medications that potentially interacted with warfarin, with the most frequent being aspirin, followed by allopurinol, fluconazole, and ibuprofen. One third of potential warfarin interactions involved a drug-drug interaction via the cytochrome P450 system.17

Table 4.

Drug Interactions With Warfarin

| Interacting Medication | No. (%) of Warfarin Patients Prescribed Other Medicationsa | Mechanism of Interaction14 |

|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | 146 (12.1) | Multiple, including effects on platelet function |

| Allopurinol | 36 (3.0) | Unknown, possibly CYP450 |

| Fluconazole | 36 (3.0) | CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP3A |

| Ibuprofen | 36 (3.0) | Inhibits platelet aggregation |

| Phenytoin | 19 (1.6) | CYP450 |

| Phytonadione | 12 (1.0) | Vitamin K antagonizes warfarin’s effect |

| Metronidazole | 10 (0.8) | CYP2C9 |

| Carbamazepine | 9 (0.7) | CYP450 |

| Naproxen | 7 (0.6) | Inhibits platelet aggregation |

| Meloxicam | 6 (0.5) | Inhibits platelet aggregation |

| Fenofibrate | 4 (0.3) | CYP2C9 |

| Indomethacin | 3 (0.2) | Inhibits platelet aggregation |

| Cimetidine | 2 (0.2) | Inhibits hydroxylation in liver |

| Etodolac | 2 (0.2) | Inhibits platelet aggregation |

| Gemfibrozil | 2 (0.2) | CYP2C9 |

| Methimazole | 2 (0.2) | Altered metabolism of vitamin K-dependent clotting in thyroid disease |

| Phenobarbital | 2 (0.2) | CYP450 |

| Thyroid preparations | 2 (0.2) | Altered metabolism of vitamin K-dependent clotting in thyroid disease |

| Aminoglutethimide | 1 (0.1) | CYP450 |

| Garlic | 1 (0.1) | Antiplatelet properties |

| Ginkgo biloba | 1 (0.1) | Inhibits platelet aggregation, increased bleeding when used alone |

| Nabumetone | 1 (0.1) | May affect platelet aggregation |

| Oxandrolone | 1 (0.1) | Alters clotting factors |

| Piroxicam | 1 (0.1) | Inhibits platelet aggregation |

| Propylthiouracil | 1 (0.1) | Altered metabolism of vitamin K-dependent clotting in thyroid disease |

| Sulindac | 1 (0.1) | Inhibits platelet aggregation |

Percentages based on 1206 patients taking warfarin.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to describe anticoagulant use among patients with advanced cancer enrolled in hospice. We found that 1 of every 11 hospice patients with lung cancer was prescribed an anticoagulant, most commonly warfarin. The strongest predictor of anticoagulant choice was geographic region; hospices in the Northeast were associated with significantly higher rates of LMWH prescription than in other regions. We also found many more potential drug interactions with warfarin than with LMWH.

The decision of whether to prescribe anticoagulants for patients at the end of life is complex, given that the primary goal of hospice care is to reduce symptoms and promote quality of life. Two relatively small studies have evaluated the benefits and risks of anticoagulation in patients with thromboembolism who received palliative care.8,18 A prospective randomized study of 20 patients with cancer and an estimated life expectancy of ≤6 months who received nadroparin or placebo for thromboembolic prophylaxis showed a nonsignificant trend toward increased survival in the LMWH group without increased risk of bleeding.8 In a case series of 62 patients with advanced cancer and thromboembolic disease, 3 of 7 patients who stopped LMWH after 6 months developed symptomatic recurrent thromboembolism; although there was no major bleeding, the minor bleeding rate was 8.1%.18 No studies have specifically evaluated the effect of anticoagulants on symptoms.19

The potential benefits of anticoagulation, however, must be balanced by the risks of bleeding, administration concerns, and monitoring requirements that could negatively affect quality of life. This risk-benefit ratio is different when prescribing anticoagulants for atrial fibrillation in hospice patients, as was the case for almost 15% of patients taking warfarin in our sample. In that situation, anticoagulation does not affect symptoms but reduces the absolute risk of stroke by approximately 4% per year.20 For patients with a median survival of 20 days, if risk were evenly distributed over time, this would be equivalent to a 0.22% absolute reduction in stroke risk while enrolled in hospice.

One reason to continue anticoagulation at the end of life is the possibility that discontinuing it in patients with thromboembolism may hasten death. The annual thromboembolic recurrence rate after discontinuing warfarin after at least 3 months of therapy is between 3.2% and 10.9%.21 However, many of the trials that evaluated the effects of discontinuing warfarin have excluded patients with limited mobility or with limited life expectancy. A secondary consideration would be to extend life to afford patients and families more time for resolution and closure at the end of life. Another rationale is that anticoagulants could reduce swelling, pain, dyspnea, or other symptoms associated with thromboembolic disease.

One reason to discontinue anticoagulation at the end of life is the risk of bleeding, especially in patients with renal insufficiency or low body weight. Although dose reduction strategies to reduce bleeding risk have been advocated for LMWH,18 there is no rationale for using low-intensity warfarin, because it conveys a higher thromboembolic recurrence rate with a similar risk of bleeding.21 The risk of bleeding from anticoagulation may be higher in hospice patients because of alterations in renal function, malnutrition, and multiple drug-drug and drug-disease interactions that require more intense monitoring. Drug interactions are a concern, because many hospice patients have medications added to their regimens at the end of life.22

Should clinicians choose to continue anticoagulation at the end of life, then the question becomes: Which anticoagulant is the most appropriate? One advantage of LMWH over warfarin is superior efficacy with respect to recurrent thromboembolism in patients with cancer.7 However, the significance of this benefit is unclear in hospice patients with lung cancer, half of whom receive hospice care for <3 weeks. The normally touted advantage that LMWHs do not require frequent blood monitoring is not as certain in hospice care. LMWH increases bleeding risk in patients with renal disease and low body weight,23 and hospice patients may have changing renal function that is not routinely monitored.

The risk of bleeding with warfarin has not been studied in hospice patients, but could be higher because of poor oral intake. Malnutrition can lead to vitamin K depletion in a few days. A small study of patients with advanced cancer showed that 78% had evidence of vitamin K deficiency.24 In a prospective cohort study in 25 nursing homes, 490 patients taking warfarin over a 12-month period had 720 adverse events and 253 potential adverse events related to warfarin.24 Although most of these adverse events were considered minor, 29% of the total events were because of preventable errors in prescribing or monitoring.24 Although the patients in this study were not hospice patients per se, nearly a quarter of hospice patients in the United States receive care in a nursing home,12 and nursing home patients are at similar risk for malnutrition and polypharmacy as hospice patients. A possible strategy to reduce the risk of warfarin could be to estimate bleeding risk and discontinue warfarin in those at high risk.21 However, a risk-prediction tool has not been shown to strongly predict bleeding or patient outcomes.25 One outpatient bleeding risk index includes risks of age ≥65 years, history of stroke, history of gastrointestinal bleeding, and ≥1 comorbid conditions, including recent myocardial infarction, anemia, renal impairment, or diabetes mellitus. The rate of bleeding per 100 person-years for low-risk (0 risk factors) patients was 0% and for moderate-risk (1–2 points) patients was 4.3%. There were too few patients with a score of ≥3 to determine the rate of bleeding for high-risk patients.26

Despite the advantages of LMWH over warfarin, a main concern with LMWH use at the end of life is its high cost.27 Medicare, the primary payer of hospice care in the United States, reimburses hospice providers on a fixed per diem basis of approximately $135 per day (with slight variation depending on region), which covers all costs, including medications.12 Prescribing a LMWH for a hospice patient could expend 70% to 90% of the entire daily Medicare reimbursement rate just from the average cost per day of the LMWH alone. The implications of switching from warfarin to LMWH are shown in Table 5, which provides an estimate of the daily cost of anticoagulation for patients in our sample. The daily cost is based on the average daily dose of the anticoagulant and average wholesale price in 2006. It is worth noting that approximately $400 per year is required for monitoring warfarin.28

Table 5.

Estimated Cost of Anticoagulation in Hospice Care

| Drug Name | Average Cost Per Daya | Average Cost Per Week |

|---|---|---|

| Warfarin | $0.67 | $4.69 |

| Dalteparin | $119.12 | $833.84 |

| Enoxaparin | $97.21 | $680.47 |

| Tinzaparin | $90.72 | $635.04 |

| Fondaparinux | $122.28 | $855.96 |

Cost is based on the average wholesale price for 2006.

Another possible advantage of warfarin over LMWH is acceptability. Warfarin is administered orally and has become easier to monitor at home with point-of-care devices that use finger-stick specimens. A daily injection of an LMWH could impair quality of life.27 However, contrary to the concern that LMWH is invasive, a qualitative study in the United Kingdom showed that cancer patients considered LMWH injections acceptable and even preferable to antiembolic stockings with respect to quality of life.10 Unfortunately, in this study, no comparison was made to patients prescribed warfarin.

Clinicians caring for patients at the end of life need to make a difficult decision about whether to follow anticoagulation guidelines despite a lack of data about the benefits and risks of using anticoagulants in hospice patients. Our study describes anticoagulant use in hospice patients before the introduction of new anticoagulation guidelines by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network in 2007,4 the American Society of Clinical Oncology in 2007,6 and the American College of Chest Physicians in 2008,5 all of which advocate lifelong anticoagulation for patients with active cancer and a history of thromboembolism, preferably with LMWH rather than warfarin. The extent to which the new guidelines will affect hospice practice in the United States is unclear. Of 20 practitioners providing palliative care in 1 medical center in Austria, most agreed on anticoagulation for primary or secondary prophylaxis of thromboembolism or for atrial fibrillation in advanced cancer patients with good performance status, but none would administer anticoagulants to patients who were approaching death.29

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe anticoagulant use in the hospice population. The limitations of our study result from its retrospective design. First, actual anticoagulant use may have been overestimated, because we did not have data on medication administration. Second, although we were able to report the indication for anticoagulant use, we were unable to further define the indication of thrombosis, a nonspecific diagnosis that was more common in the warfarin group. We also were unable to determine how long a patient had a thromboembolic condition, which could be an important determinant for warfarin or LMWH use. In addition, we were unable to establish a relationship between anticoagulation and quality of life because of a lack of data about symptoms. There may be other reasons related to quality of life, such as the ability to swallow or aversion to injections, for which a particular anticoagulant may have been preferred. Third, although we were able to detect many potentially clinically significant warfarin drug interactions, information on the actual occurrence of adverse drug events was not available. Fourth, although we included comorbidities based on a valid measure, data on comorbidities may have been underreported, especially if a patient was not prescribed drug therapy for a particular condition. Finally, despite the finding that patients prescribed warfarin had a longer stay in hospice, an association between anticoagulation and survival in hospice could not be determined from this study because of the inability to control for cancer stage and severity of comorbid illness. Furthermore, the clinical significance of a difference in median length of stay of 4 days is not clear without further information about quality of life.

Given recently updated guidelines advocating the use of LMWH in patients with a history of thromboembolism and active cancer, optimal use of anticoagulants in hospice patients needs to be determined. The change in anticoagulation guidelines, favoring the long-term use of LMWH in patients with cancer and thromboembolism, is accompanied by changing attitudes of palliative care practitioners and their patients favoring anticoagulation with LMWH.11 Hospice patients with cancer are at higher risk of thromboembolism and bleeding; thus, the optimal balance between these risks must include the effect of anticoagulation and choice of anticoagulant on quality of life and on burdensome symptoms at the end of life. In addition, the substantial cost incurred by instituting current anticoagulation guidelines in end-of-life populations whose medications are supported by a fixed daily reimbursement rate must be considered. Given the risk-benefit ratio, the use of anticoagulants to prevent stroke for hospice patients with atrial fibrillation is probably not justified. Further study should be directed at determining the benefits of anticoagulants in reducing symptoms at the end of life and quantifying the risks of bleeding in this vulnerable population, all within the context of the cost-effectiveness of therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tamara Locke, who assisted in editing a final version of the article, and Jude K. A. Des Bordes, who assisted in the literature review.

Footnotes

Presented in part as a poster at the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer General Assembly, Rome, Italy, June 25-27, 2009.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

Dr. Holmes is supported by a Hartford Geriatrics Health Outcomes Research Scholars Award. Dr. Bain is an employee of excelleRx, Inc., operating as Hospice Pharmacia.

References

- 1.Tassinari D, Santelmo C, Scarpi E, et al. Controversial issues in thromboprophylaxis with low-molecular weight heparins in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36:e3–e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soto-Cardenas MJ, Pelayo-Garcia G, Rodriguez-Camacho A, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with advanced cancer under palliative care: additional risk factors, primary/secondary prophylaxis and complications observed under normal clinical practice. Palliat Med. 2008;22:965–968. doi: 10.1177/0269216308098803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson M, Sproule M, Paul J. The prevalence and associated variables of deep venous thrombosis in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 1999;11:105–110. doi: 10.1053/clon.1999.9023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Streiff M. The NCCN guidelines on venous thromboembolism. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2007;5:117–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition) Chest. 2008;133(suppl 6):1S–453S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lyman GH, Khorana AA, Falanga A, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Guideline: recommendations for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and treatment in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5490–5505. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zacharski L, Prandoni P, Monreal M. Warfarin versus low-molecular-weight heparin therapy in cancer patients. Oncologist. 2005;10:72–79. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.10-1-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weber C, Merminod T, Herrmann FR, et al. Prophylactic anti-coagulation in cancer palliative care: a prospective randomised study. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:847–852. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0339-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noble S. The challenges of managing cancer related venous thromboembolism in the palliative care setting. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:671–674. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2007.061622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noble SIR, Nelson A, Turner C, Finlay IG. Acceptability of low molecular weight heparin thromboprophylaxis for inpatients receiving palliative care: qualitative study. BMJ. 2006;332:577–580. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38733.616065.802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noble SI, Finlay IG. Have palliative care teams’ attitudes toward venous thromboembolism changed? A survey of thromboprophylaxis practice across British specialist palliative care units in the years 2000 and 2005. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. [Accessed August 18, 2009.];National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization Facts & Figures. 2008 Available at: http:/files/public/Statistics_Research/NHPCO_facts-and-figures_2008.pdf.

- 13.Chew H, Davies A, Wun T, et al. The incidence of venous thromboembolism among patients with primary lung cancer. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:601–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.02908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strassel SA, Blough DK, Hazlet TK, et al. Pain, demographics, and clinical characteristics in persons who received hospice care in the United States. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32:519–531. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bain KT, Maxwell TL, Strassel SA, et al. Hospice use among patients with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2009;158:118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris D, et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. [Accessed August 2009.];Lexi-Interact. Available at http://www.lexi.com.

- 18.Noble SI, Hood K, Finlay IG. The use of long-term low-molecular weight heparin for the treatment of venous thromboembolism in palliative care patients with advanced cancer: a case series of sixty-two patients. Palliat Med. 2007;21:473–476. doi: 10.1177/0269216307080816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noble S. Management of venous thromboembolism in the palliative care setting. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2007;13:574–579. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2007.13.12.27884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. Risk factors for stroke and efficacy of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1449–1457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spiess JL. Can I stop the warfarin? A review of the risks and benefits of discontinuing anticoagulation. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:83–87. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Currow DC, Stevenson JP, Abernethy AP, et al. Prescribing in palliative care as death approaches. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:590–595. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clark NP. Low-molecular-weight heparin use in the obese, elderly, and in renal insufficiency. Thromb Res. 2008;1(suppl 1):S58–S61. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harrington DJ, Western H, Seton-Jones C, Rangarajan S, Beynon T, Shearer MJ. A study of the prevalence of vitamin K deficiency in patients with cancer referred to a hospital palliative care team and its association with abnormal haemostasis. J Clin Pathol. 2008;61:537–540. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2007.052498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Radford MJ, et al. The safety of warfarin therapy in the nursing home setting. Am J Med. 2007;120:539–544. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dahri K, Loewen P. The risk of bleeding with warfarin: a systematic review and performance analysis of clinical prediction rules. Thromb Haemost. 2007;98:980–987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirkova J, Fainsinger RL. Thrombosis and anticoagulation in palliative care: an evolving clinical challenge. J Palliat Care. 2004;20:101–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wells P, Forgie M, Simms M, et al. The outpatient bleeding risk index: validation of a tool for predicting bleeding rates in patients treated for deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:917–920. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.8.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sullivan PW, Arant TW, Ellis SL, et al. The cost effectiveness of anticoagulation management services for patients with atrial fibrillation and at high risk of stroke in the US. Pharmacoeconomics. 2006;24:1021–1033. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200624100-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]