Abstract

In this review, we describe the application of experimental data and modeling of intracellular endocytic trafficking mechanisms with a focus on the process of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. A detailed parts-list for the protein–protein interactions in clathrin-mediated endocytosis has been available for some time. However, recent experimental, theoretical, and computational tools have proved to be critical in establishing a sequence of events, cooperative dynamics, and energetics of the intracellular process. On the experimental front, total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy, photo-activated localization microscopy, and spinning-disk confocal microscopy have focused on assembly and patterning of endocytic proteins at the membrane, while on the theory front, minimal theoretical models for clathrin nucleation, biophysical models for membrane curvature and bending elasticity, as well as methods from computational structural and systems biology, have proved insightful in describing membrane topologies, curvature mechanisms, and energetics.

1. Interactions mediating the clathrin-mediated endocytosis

Endocytosis is the process by which an intracellular vesicle is formed by membrane invagination, engulfing extracellular and membrane-bound components. Endocytosis and the reverse process of exocytosis are required for a large number of essential cell functions, including nutrient uptake, cell–cell communication, and the modulation of membrane composition. The central role of these transport mechanisms is well appreciated in receptor regulation, neurotransmission, and drug delivery.1,2 Endocytosis exists in different forms: phagocytosis, pinocytosis, receptor-mediated endocytosis (most commonly clathrin-mediated endocytosis or CME, 3–11 which is the focus of this review). Other mechanisms include caveolae-mediated endocytosis,12 and transient poration induced by shocks to the cellular microenvironment. There is accumulating evidence that endocytosis is not merely a mundane transport process to assist in cargo trafficking; instead it features in crucial regulatory roles.9 Impaired deactivation of receptor tyrosine kinases13 through attenuation of endocytosis is linked to hyper-proliferative conditions such as cancer.14,15 Certain receptors of the ErbB family, (e.g., ErbB4), have competing internalization pathways, i.e., endocytosis vs. proteolytic cleavage, constituting a biochemical switch, which is implicated in the regulation of cardiac development as well as in pathological signaling in neurological disorders such as Schizophrenia.16–18 Recent evidence suggests that various pre-synaptic proteins regulating neurotransmission via endo/exocytosis are either mutated or over-expressed in neurological and psychiatric disorders.19 The cellular endocytic machinery is also co-opted by several bacterial and viral pathogens, including HIV, HSV and E. coli, to gain entry into and infect otherwise healthy cells.20–23

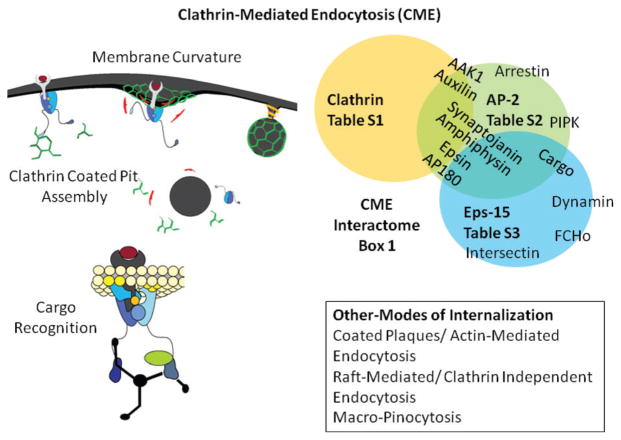

Our current understanding of CME can be summarized by several steps (outlined in Fig. 1), which include: (1) nucleation of clathrin-coated pits; (2) cargo capture in coated pits; (3) curvature-induction and membrane invagination; (4) vesicle-scission and uncoating; and (5) endosomal sorting. In the past 15 years, extensive studies of the individual steps have yielded a detailed parts-list of the components of the CME machinery, which is outlined in Box 1, see also Tables S1–S3 (ESI†). Such a list focuses on protein–protein interactions that are believed to orchestrate the signaling environment as well as the protein–membrane interactions in CME. However, as we discuss in this review, a functional and mechanistic understanding of this process is still elusive despite the detailed enumeration of the interactions. In Sections 2 and 3, we describe the complementary and synergistic role played by theory and modeling in delineating the mechanistic underpinnings of the interactions of the CME proteome. In Section 4, we conclude by outlining the outstanding challenges and the outlook for future, which is centered on rationalizing the predictions of multiscale biophysical models with emerging super-resolution imaging experiments.

Fig. 1.

Overview and “parts”-list of clathrin-mediated endocytosis.

BOX 1. Component “Parts” of CME.

Clathrin

Clathrin monomers are made up of 3 light chains and 3 heavy chains arranged into triskelia. The heavy chains contain the clathrin’s binding sites for most other proteins, including AP-2 and other cargo-specific endocytic adaptors. The light chains bind together to arrange clathrin into triskelia, preventing unstimulated polymerization of clathrin heavy chains;24 they contain few binding sites, such as for HIP1R, a protein involved in clathrin plaque endocytosis by recruiting the actin machinery.25 Unsurprisingly, clathrin is essential for CME and plays major structural and biochemical functions. The organization of clathrin monomers causes individual triskelia to possess an intrinsic pucker angle, such that free-floating clathrin in high concentrations spontaneously polymerizes into closed cages.26,27 One method by which CCV size may be regulated is by tightly controlling the pucker angle of bound triskelia; indeed some postulate that CALM protein does precisely this to control endocytic vesicle size. 28–30 Due to the intrinsic curvature of polymerized clathrin networks, it has also been speculated that the growing clathrin coat in CCPs serves to fix the membrane into a spherical bud.31,32 The second major function of the clathrin network is to activate AAK1 via multiple heavy- and light-chain interactions.33 This activation allows AAK1 to unlock AP-2, which is required for cargo incorporation and stabilization of the required AP-2 concentration at CCP sites. A list of important clathrin binding partners is included in Table S1 (ESI†).

AP-2

AP-2 is an endocytosis-specific protein in a family of heterotetrameric adaptors widely implicated in clathrin-mediated budding events, see Table S2 (ESI†); other family members are involved in endosomal or trans-Golgi network vesicle formation.34 AP-2 is initially recruited to the membrane by the Eps15/Intersectin/FCHo complex along with Epsin.35 Both Eps15 and Epsin possess multiple AP-2 binding motifs situated on long unstructured domains; these domains extend out from the cytosolic face of the membrane, recruiting a sufficient AP-2 concentration to begin clathrin polymerization.36 Clathrin network activation of AAK1 produces a conformational change in AP-2, swinging the μ2 domain out 90° such that it lies parallel to the membrane. This rearrangement exposes AP-2 sites for direct cargo binding and indirect binding through cargo-specific adaptors, as well as an additional, higher-affinity binding site for PIP2.37 If cargo is captured in the CCP, the AP-2/cargo complex activates PIPK Iγ, which generates an additional membrane PIP2 that can sustain further CCP growth.38 This activation can occur both directly, via AP-2 interaction with the PIPK kinase core domain, and indirectly, via GEF/GTPase combinations like SMAP1/Arf6.39 The requirement of cargo capture for PIPK Iγ prevents unproductive CCPs from maturing, since the additional PIP2 production is required to overcome baseline synaptojanin phosphatase activity on existing PIP2. Indeed the strict regulation of PIP2 levels by AP-2 and cargo-dependent signaling and synaptojanin activity is thought to be important throughout CME, and is likely the mechanism of matching vesicle size to cargo content.40–42 Once cargo is sequestered in the coated pit, the radial decay of the PIP2 gradient prevents more AP-2 from binding. The residual curvature outside the PIP2-rich region allows amphiphysin to bind, and its ability to bind clathrin extends the coat slightly beyond the AP-2 rich region. This provides one explanation for the observed results of Kirchhausen et al. that AP-2 is relatively enriched toward the back of the vesicle.43,44 After vesicle scission, the disassembly of the clathrin coat is partly mediated by AP-2 dissociation from the vesicular membrane. This dissociation is dependent on Rab5 and hRME6, which displace AAK1 from AP-2 to dephosphorylate the μ2-subunit.45 The resulting inactivation of the AP-2 high-affinity PIP2 binding site is coordinated with synaptojanin-mediated depletion of membrane PIP2,46,47 releasing AP-2 from the membrane and generating enough PI(4)P to recruit auxilin/GAK to the vesicle to finish the uncoating process.

Eps15

Eps15 is constitutively associated with CCPs in vivo, performing an essential function from the time of CCP nucleation until deep invagination and scission of the CCV. As part of the CCP nucleation complex (see Table S3, ESI†), Eps15 initiates coat assembly by recruiting AP-2 and CALM to the plasma membrane.35,48–50 By binding multiple AP-2 molecules simultaneously, it can generate a sufficient local concentration to promote clathrin polymerization. Since clathrin association with AP-2 disrupts the Eps15 binding site, Eps15 is continually pushed to the rim of the growing CCP, where it can effectively recruit AP-2 to increase the size of the clathrin coat.50 In addition to recruiting additional AP-2, Eps15 interacts with dynamin by complexing with intersectin, and recruits dynamin to the membrane to permit deep invagination into a budding vesicle.51,52 For most classes of endocytic cargo, Eps15 is not incorporated into budding CCVs.53 In the case of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) or other poly-ubiquitinated cargo-internalization, Eps15 serves as a cargo-specific adaptor protein.54 After Cbl-dependent polyubiquitination of EGFR, Eps15 is phosphorylated on tyrosine residue 850 and captures the EGFR via its ubiquitin-interacting motifs (UIMs), sequestering it into the coated pit.55 Successful EGFR internalization is dependent on Eps15 phosphorylation, and phosphopeptide experiments demonstrate that pTyr850 is likely a binding site for a PTB-domain containing protein. Since unphosphorylated Eps15 does not remain within endocytic coated pits, it is likely that the phosphotyrosine binding protein in question serves to anchor the Eps15/EGFR complex within the coated pits. This prediction is further supported by the knowledge that Eps15 interacts with sorting components further downstream, such as Hrs and ESCRT proteins.56

Epsin

Epsin is an ENTH-domain protein that plays a role in mediating membrane curvature in endocytic pits. Epsin binds membrane PIP2 and inserts an amphipathic helix into the membrane, producing a curvature-inducing deformation.57 Epsin may also (similar to Eps15) aid in recruiting AP-2 to the membrane by simultaneously binding up to 8 AP-2 molecules, and also like Eps15 is displaced from AP-2 by clathrin binding.29 Although epsin’s intrinsic capability for membrane association may theoretically allow it to persist within CCPs, images of Epsin/Eps15 colocalization and more recent z coordinate-sensitive methods of microscopy suggest that Epsin follows Eps15 in migrating to the rim of growing coated pits. Epsin, like Eps15, also serves as a cargo-specific binding protein and adaptor for ubiquitinated proteins, shuttling monoubiquitinated cargo to non-clathrin endocytosis (NCE) and polyubiquitinated cargo to CME.4,58,59 Interestingly, Epsin knockouts or Eps15 knockouts alone are not strongly deficient in CME of ubiquitinated cargo, while multiple-knockout cells are, demonstrating that Epsin and Eps15 may serve a redundant function as cargo-dependent adaptors.60

Amphiphysin

Amphiphysin is an N-BAR domain protein with curvature-sensing and curvature-inducing capability. Its initial recruitment to the membrane is likely mediated by some combination of affinity for AP-2 and clathrin, and attraction to the high-curvature neck region of the forming CCV.61,62 Since the curvature-sensing and membrane-bending ability of amphiphysin are both initially under autoinhibition, the early stages of amphiphysin recruitment may be mediated by association with AP-2 and clathrin at the CCP rim.61 The membrane localization of amphiphysin attracts dynamin dimers,63 and their association with amphiphysin releases its N-BAR domain from SH3 autoinhibition. This recovers its membrane-tubulating ability, allowing the protein to further aggregate at and constrict the vesicle neck. Together, the high local concentration of dynamin and tubular nature of the neck allow dynamin to oligomerize into a helical collar interspersed with amphiphysin.62,64 Sorting nexin 9 (SNX9) has been shown in certain cell types such as HeLa cells, which do not express amphiphysin, to perform the analogous function to amphiphysin;65–67 in amphiphysin-expressing cells the two proteins may perform a redundant function.

Dynamin

Dynamin is initially recruited to the membrane neck by amphiphysin, and potentially also by the Eps15/intersectin complex. As described above, dynamin then oligomerizes into a helical collar,68 and proceeds to mediate vesicle scission in a GTP-dependent manner. 63,69 The exact mechanism of scission is uncertain, but several models have been put forward. The traditional view of dynamin is that it acts as a pinchase,69 physically constricting the thin neck until thermal fluctuations are enough to mediate complete breakage between the cell membrane and the vesicle. Supporting this view is evidence that GTP hydrolysis by the dynamin collar produces a rotation in the helical protein assembly, suggesting mechanical constriction of the neck.70,71 An alternate view is that PIP2 binding by the numerous dynamin pleckstrin homology (PH) domains at the vesicle neck effectively induce phase separation with a high PIP2 concentration at the neck and a much lower concentration on the bulk membrane.72 This phase separation generates an energetic impetus to reduce the neck radius, in order to minimize the points of contact between the high-PIP2 and low-PIP2 regions (i.e. reduce line-tension). Yet another experimental study falls somewhere in between: reproducing the GTP-dependent helical twisting, Roux et al. conclude that the mechanical force is not enough to split the vesicle from the bulk membrane, necessitating additional driving force such as separation-induced line tension.69

Synaptojanin

Synaptojanin (specifically splice variant synaptojanin 1, a 170 kDa protein) is a phosphoinositide phosphatase that plays a general regulatory role in CME and a large role in disassembly of the clathrin coat after vesicle budding. It converts membrane PIP3 to PIP2, and PIP2 to PIP, and is recruited to the membrane by endophilin.47 Since PIP2 levels must be tightly regulated during endocytosis, synaptojanin is required even before the vesicle uncoating step;73 without its phosphatase action, high membrane PIP2 levels could cause nonspecific binding and mislocalization of endocytic proteins. The most well-defined role for synaptojanin is in CCV uncoating. Synaptojanin is recruited to the vesicle as Rab5 disrupts the highest-affinity AP-2/PIP2 interactions45—creating binding sites for the endophilin/synaptojanin complex—and proceeds to convert PIP2 into PI(4)P. The uncoating process is then completed by GAK/auxilin and Hsc70.

GAK/Auxilin

GAK and auxilin are homologs expressed ubiquitously and selectively in nervous tissue, respectively. GAK/auxilin (hereafter referred to as just auxilin) are recruited to the endocytic vesicle after synaptojanin generates a sufficient concentration of PI(4)P on the vesicle. Although baseline regulatory phosphatase activity produces a continuous supply of membrane PI(4)P during earlier stages of CME, the ability of the PI(4)P to diffuse into the bulk membrane from the endocytic pit precludes premature auxilin recruitment.74 Once the CCV has detached from the membrane, the confinement of generated PI(4)P to the vesicle allows a sufficient concentration to build up and recruit auxilin. Auxilin simultaneously binds the membrane and clathrin coat, and recruits the chaperone protein Hsc70 which binds to the auxilin J-domain.75,76 Once the Hsc70/auxilin complex is established, it can completely disassemble the clathrin coat from the vesicle.

2. Components limiting the clathrin coat formation and minimal models for clathrin coat nucleation

2.1 Nucleation of clathrin-coated pits (CCP)

In CME, the nucleation of productive CCP on the plasma membrane appears to be a stochastic process,77 and recent evidence shows that this nucleation is dependent on a protein complex of FCHo1/2, Eps15 and intersectin-135 (see Box 1 for a “parts”-list of proteins involved in CME, see also Fig. 1 and Tables S1–S3, ESI†). This complex assembles at coated pit nucleation sites prior to clathrin coat formation and recruits the AP-2 adaptor protein at the site of the future pit via the multiple AP-2 binding sites of Eps15.29,48,50,53 Clathrin is then recruited to the plasma membrane by AP-2, and the increased local clathrin concentration exceeds the threshold required for polymerization of the clathrin triskelia.28,53,78–81 There is also evidence for the random formation of rapidly abortive pits, which may form when thermal fluctuations transiently produce a critical local concentration of AP-2 at the membrane, allowing for brief clathrin polymerization.82 These pits quickly dissociate, however, due to the lack of accessory proteins to stabilize AP-2 at the membrane.77 Theoretical and computational studies of clathrin have answered certain physical questions about individual triskelia and the polymerized clathrin coat. A simple thermodynamic model has been used to peg the strength of heavy chain interactions at ~kBT (the amplitude of thermal fluctuations), and to demonstrate that adaptor protein binding deepens the energetic well for clathrin polymerization.83,84 Thus, clathrin fails to polymerize at physiological concentrations unless it is locally concentrated by adaptor binding.

2.2 Minimal model of clathrin coat assembly

While the prevailing viewpoint in CME suggests that clathrin is necessary in coated pits in order to stabilize their shape and perhaps to drive membrane invagination, it is somewhat difficult to reconcile the putative stabilization capability of the clathrin lattice with the fact that clathrin leg–leg interactions only provide an energetic benefit on the order of thermal fluctuations (~kBT).32 Even though sides of the hexagonal/pentagonal lattice are each composed of two proximal and two distal legs, the small energy contribution of each precludes extremely strong attachment. In addition, lattice-incorporated clathrin is reported to freely exchange with the cytosolic reservoir even in growing coated pits,85,86 which seems to suggest that the clathrin lattice may itself easily be disrupted, reducing its ability to sustain membrane curvature. Given the weak energetics of clathrin–clathrin binding, it stands to reason that association between clathrin and membrane-bound adaptor proteins serves as a much stronger driving force toward clathrin assembly on the membrane. While clathrin itself may, at high enough concentrations, assemble into membrane-less cages,27,87 in order to polymerize at physiological concentration and bend the membrane it must be recruited and stabilized by stronger protein–protein binding interactions.

To establish a minimal model for clathrin lattice formation, we consider a three-species (q = 3) inhomogeneous Potts model (cellular Potts model or CPM) in which clathrin, adaptor protein and free membrane coexist on a 2-dimensional hexagonal (6 nearest neighbor) lattice. In the CPM framework,88 the Hamiltonian is defined as:

| (1) |

Here, J is the interaction energy between the cells σ(i,j) and σ(i′,j′) which occupy neighboring lattice sites (i,j) and (i′,j′). For our simulations, J is dependent on the cell types of the two neighbors (τ(σ), see Table 1 for energy values). The delta function term is implemented to prevent self-interaction between lattice sites which are part of the same cell, but has minimal effect in our simulations since cells rarely occupy more than one lattice site. The second term in this expression is a target area constraint which restricts the area of clathrin and adaptor on the coat, reflecting the finite dimensions of lattices formed on the membrane prior to invagination. The constant λ represents the strength of the area constraint, and a(σ) is the cell size, and Aτ(σ) is the target cell size.

Table 1.

Stable coat formation with clathrin and AP2; C = clathrin, A = AP2

| C–C Energy [J(C,C)] = [J(A,A)] | C–A Energy [J(C,A)] | C Area constraint [C] [Aτ=C] | A Area constraint [A] [Aτ=A] | Coat formation? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stable coat | −kBT | −8 kBT | 1 | 1 | Yes |

| Coat depletion | −kBT | −8 kBT | 1 | 0 | No |

| High clathrin | −kBT | −8 kBT | 3 | 0 | Yes |

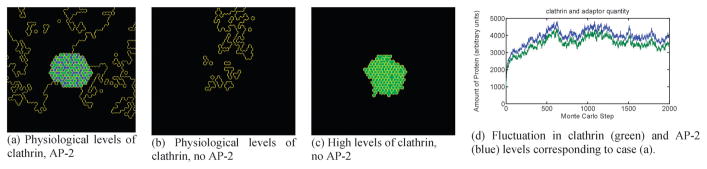

Using the CPM, we identified regimes of binding energy and concentration for which transient lattice nucleation, stable lattice nucleation, and no lattice nucleation are observed. This simple model, which fits experimental evidence of both native and cell-free or other non-physiological parameter sets, provides a clear demonstration of how clathrin may assemble into a stable lattice with a weak intrinsic impetus for oligomerization. Furthermore, the model elucidates a biological necessity for this weak interaction: it is strong enough, but not too strong as to induce spurious nucleation of clathrin lattices which would deprive the cell of its available cytosolic clathrin pool. Interaction energy parameters for the three identified regimes are described in Table 1 and depicted in Fig. 2. In the regime corresponding to Fig. 2(a), low levels of clathrin are stabilized to the membrane via association with adaptors, to which they bind more strongly. The model in this regime represents a general dilute antiferromagnetic Ising model, and the frustration in the hexagonal lattice prevents nearest-neighbor interactions from being purely in the lowest energy state. This leads to a degenerate ground state with fluctuations of clathrin levels around a mean value, see Fig. 2(d), which reproduces the exchange between cytosolic and coated pit-dwelling clathrin observed experimentally. Fig. 2(b) depicts no membrane clathrin localization without AP2. This regime uses the same energy parameters as the wild-type state, but the removal of AP2 from the forming bud causes clathrin to completely vacate the membrane surface. This is consistent with the findings that at physiological concentrations, clathrin–clathrin interactions are not strong enough to stabilize a coated pit, and instead any clathrin that becomes membrane-bound does so only transiently, soon recycling back into the cytosolic pool. Fig. 2(c) depicts the regime of supra-physiological clathrin concentration, which induces AP2-independent coat formation. When the total area constraint (see eqn (3)) on clathrin is relaxed in the model, analogous to increasing the clathrin concentration in vivo, coated pit formation is rescued even in the absence of AP2. This phenomenon also occurs if the clathrin self-interaction is made more energetically favorable. Adaptor-free clathrin cages have been observed in cell-free experiments with high levels of clathrin concentration, and in auxilin knockdown experiments where auxilin-dependent inhibition of clathrin self-interaction is abrogated, corresponding to the model result.

Fig. 2.

Green = clathrin; blue = AP-2; black = medium. (a) At normal concentrations, clathrin and adaptor for a stable coat. (b) Removal of the adaptor leads to coat disappearance. (c) At supra-physiological levels, clathrin can polymerize into cages independent of the adaptor. (d) In coats containing clathrin and adaptor, the amount of each coat component is dynamic throughout the simulation even after stable coat formation.

2.3 Cargo capture in coated pits

How clathrin coat and vesicle size are regulated in vivo is a matter for debate. The precise mechanism is poorly understood, but is thought to involve a complex interplay between PIP2 levels, cargo capture and sequestration, and signaling. The formation of the clathrin network triggers an increase in the activity of Adaptin-Associated Kinase 1 (AAK1), which phosphorylates the μ2-subunit of AP-237,78 (see Box 1 and Table S1, ESI†). This kinase action unlocks the structure of the AP-2 adaptor, allowing it to bind more strongly to membrane PIP2 and exposing the μ2 cargo-binding site.34 The appearance of cargo at the growing structure presents a checkpoint that determines the productivity of the coated pit. If cargo does not enter the pit, the local concentration of membrane PIP2 becomes insufficient to stabilize the growing network of clathrin, AP-2 and other adaptor/accessory proteins, leading to the dissolution of the coated pit prior to an endocytic event.82 At this stage, endocytic cargo—either constitutively internalized (e.g. transferrin receptor) or ligand-induced (e.g. EGFR) receptors (see Section S1, ESI†)—that enters the CCP is retained in this pit and provides the signaling impetus for continued growth and invagination of the CCP. The cargo is bound by AP-2, either directly by the μ2 subunit or indirectly by class-specific adaptors (see Tables S1–S3, ESI†), and the cargo–AP2 complex triggers the activity of PIP kinase type Iγ (PIPK Iγ), increasing the local concentration of membrane PIP2.36,89 As AP-2, Epsin, and most other CME-associated proteins bind PIP2, the activity of PIPK Iγ produces a sufficient concentration of membrane binding sites to sustain the growing CCP.

It is worth noting that this signaling structure presents one possible mechanism for matching CCP size to the level of captured cargo. The CCP can propagate as long as PIPK Iγ is activated by the AP-2/cargo complex, and radial growth is terminated when the cargo, clustered near the cytosolic pole of the CCP,44 is too far from the pit edge to sustain sufficient PIPK Iγ activity. Experiments on CME of the LDL receptor have reproduced the effects on CCP size predicted by this model for varying cargo levels, and recent cell-free studies have demonstrated that lipid domain formation (in this case a PIP2-rich domain) can work in concert with membrane proteins to regulate curvature generation and vesicle budding.90

Multiple non-exclusive mechanisms have been proposed to explain cellular control of clathrin-coated vesicle size. Ehrlich et al. observed that the size of coated pits and subsequent vesicles were dependent on the amount of cargo loading, with coated pits persisting longer and becoming larger upon higher levels of cargo incorporation.77 It was also observed that the checkpoint at which coated pits were either aborted or committed to vesiculation was largely standardized, strengthening the notion that cargo binding controls the biochemical checkpoint to allow CCPs to develop further. The authors propose that the bending rigidity of the underlying membrane may resist curvature above this critical coat size, and that cargo binding stabilizes the coat and allows further membrane bending.

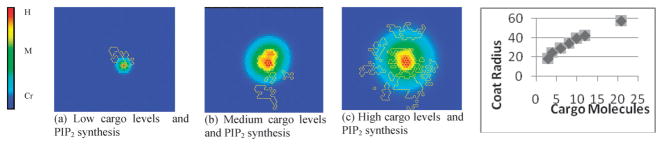

This argument, however, may not explain the disassembly of coated pits that lack cargo at the checkpoint. If the membrane bending rigidity is the only force opposing coat enlargement, since the bending energy increases with coat size, there should exist a nonzero average vesicle size around which cargo-free pits fluctuate. An alternative explanation, which may better fit the observed data, is that cargo entrance into coated pits mediates pit growth biochemically by increasing levels of PIP2 in a dose-dependent manner. Upon cargo capture, AP2-cargo complexes are formed which activate PIP kinase type Iγ.38,89 The PIPK then increases local levels of PIP2, which diffuses among other membrane phospholipids. In this way the cargo concentration can clearly affect coated pit size, since higher levels of PIP2 produce a larger membrane area of enriched PIP2 to sustain coated pit growth. Baseline phosphatase activity slowly depletes PIP2 away from the AP2–cargo complex, such that coats do not grow without bound. Since PIP2 is a binding partner for several CME-related proteins, it must be maintained above a critical level to support pit growth. Transient coated pits are nucleated by FCHo–Intersectin–Eps15 complexes,35 which allow AP2 and clathrin to transiently cluster into a preliminary coated pit, but under this mechanism, it is clear that the pit will disassemble if PIP2 levels are not increased to a critical level via cargo capture.77 These interactions are captured in a model described below, demonstrating the production–diffusion–elimination equilibrium for different cargo levels, lending credence to this proposed mechanism. We model the synthesis, diffusion, and absorption of membrane-bound species using the Cellular Potts Model framework. Specifically, we alter the concentration of the AP2–cargo complex, allowing this complex to synthesize PIP2 at a specified rate per complex; we explore low, medium, and high rates of PIP2 synthesis. The surrounding medium can absorb PIP2 at a specified rate, to mimic the baseline phosphatase activity exerted by regulatory components around the membrane; we keep the absorption rate fixed in our simulations at a constant value. We then examined the PIP2 field at equilibrium to show that the membrane area containing PIP2 above a given critical threshold concentration grows along with the cargo concentration. Fig. 3 shows equilibrium images of the field for three different cargo concentrations (or three different rates of PIP2 synthesis). The concentration gradient is color coded with red indicating high PIP2 concentration and blue indicating low levels of PIP2. Fig. 3 also displays the maximum size (in arbitrary units) of clathrin coats for different levels of cargo production.

Fig. 3.

Increasing levels of cargo within a coated pit (a)–(c) lead to larger stable coats, as predicted by the model. (d) Clathrin coat size dependence on cargo levels predicted by the model. In the color scale bar, H, M, Cr, correspond to high, medium, and critical (lower-bound) concentration of PIP2.

3. Mechanism and biophysical model for membrane deformation and curvature

3.1 Curvature induction and membrane invagination

Clathrin coat growth and membrane invagination proceed in tandem within canonical CCPs. Concomitantly with the addition of clathrin triskelia to the coat, curvature is induced in the plasma membrane around the coat, forming a growing bud on the cell surface.31,32,91 The development of this curvature is putatively mediated by multiple membrane-binding proteins, including epsin,57,92 amphiphysin,61,62,64,93 and by the clathrin coat itself.31 The initial membrane deformation may occur during CCP nucleation itself, where FCHo proteins generate a small membrane curvature through their F-BAR domains.35 Once the adaptor machinery has begun to assemble at the endocytic site, ENTH domain-containing epsins are recruited by Eps15 and higher levels of membrane PIP2, and induce a stronger curvature by inserting amphipathic helices into the membrane. As the spherical bud begins to emerge, a tubular neck region begins to form in the membrane; this region is uncovered by the clathrin coat and contains free PIP2, but is still subject to a large curvature, which attracts proteins containing curvature-sensing N-BAR domains such as amphiphysin and endophilin.46

The mechanism by which clathrin sustains curvature in the bud region remains an open question from an energetics stand-point. Since individual heavy chain interactions are not stronger than thermal fluctuations, it is difficult to understand how the clathrin coat can impose its intrinsic curvature on the membrane, especially in the event that epsins migrate to the CCP rim. One possibility is that the clathrin coat imparts a larger bending rigidity on the underlying membrane. Even in the absence of strong inter-protein attraction, computational studies demonstrate that inclusions of increased rigidity tend to aggregate on the membrane.94–96 This rigidity-driven attraction effectively strengthens the clathrin coat, increasing its ability to isotropically deform the membrane. The alternative view is that tubulating proteins (e.g. epsins) are incorporated as part of the growing coat through CLAP domain or AP-2 mediated interactions to stabilize the curvature, which was recently proposed in a model described below.

3.2 Elastic bending free energy for fluid membranes

Following the Helfrich formulation,97 we describe the membrane energy E as:94,95

| (2) |

Here, κ and κ′ are membrane elastic bending rigidities, H = 1/2(C1 + C2) is the mean curvature of the membrane, C1 and C2 are the two principal curvatures, H0 is the spontaneous imposed (or intrinsic) curvature of the membrane due to curvature-inducing proteins, K = C1C2 is the Gaussian curvature, σ is the frame tension, and A is the total membrane area. For small deformations of the membrane, the shape of the membrane can be represented in the Monge gauge (z = z(x,y)), converting the Hamiltonian (not including the Gaussian rigidity term) into the more computationally efficient form:

| (3) |

Several extensions to the Helfrich model applicable to the endocytosis problem have been discussed in the literature:98–108 (1) a model treating a membrane as a pair of slightly compressible monolayer bound together with non-instantaneous lipid density relaxation has been proposed.105 (2) A model for cytoskeleton fortified membranes has been developed98 and applied to erythrocyte deformation.99 This model includes shear elasticity of the cytoskeleton in combination with the Helfrich Hamiltonian. (3) The dynamics of the Helfrich membrane in the overdamped limit including hydrodynamic coupling to the surrounding solvent and arbitrary external forces have been introduced.100–104 (4) The infinitely thin assumption for the membrane surface has also been relaxed and the inter-layer friction and slippage between the lipid monolayers have been incorporated.104–106 (5) Direct simulation of eqn (2) using a Monte Carlo (MC) method allowing for the treatment of systems with extreme curvature has also been described.108

Migration of trans-membrane and peripheral proteins can be driven via both static membrane curvature gradients and by dynamic membrane fluctuations.109–131 Several recently discovered protein membrane-binding domains have been postulated to assemble in a process that is driven by membrane curvature and membrane tension and in the process induce local deformations of the bilayer.115,129 During the process of endocytosis, clustering of proteins with the ENTH domain in regions of background mean curvature44 have been reported. These studies have further motivated the development of models for protein diffusion in ruffled surfaces110–113 and the simultaneous diffusion of protein and membrane dynamics. In a recent work, Agrawal et al. modeled the intrinsic curvature field of each curvature-inducing protein as a Gaussian function with a range bi and magnitude C0,i:

| (4) |

where xi and yi are the x and y coordinates of the ith inclusion on the membrane. When multiple proteins are present on the membrane, the resulting protein-induced membrane curvature is calculated as:

| (5) |

where Ne is the number of proteins present on the membrane.125 The protein diffusion is modeled through the simulation of probabilistic hopping along the membrane surface. Using this model, recently, Weinstein and Radhakrishnan have treated simultaneous protein diffusion and membrane motion models to treat the case of curvature inducing proteins diffusing on the membrane.126 The new aspect of their continuum membrane model is the two-way coupling between the protein and membrane motion. In this case, the membrane topology not only influences the protein diffusion by presenting a curvilinear manifold, but also presents an energy landscape for protein diffusion. The protein diffusion in-turn impacts membrane dynamics because the spatial location of the proteins determines the intrinsic curvature functions and hence the elastic energy of the membrane.94,95 Using this approach they identify regimes of curvature magnitude and range for which bud nucleation was induced by curvature-mediated cooperative orientation of non-interacting proteins.94

Agrawal et al. have also developed a computational methodology for incorporating thermal effects and calculating relative free energies for elastic fluid membranes subject to spatially dependent intrinsic curvature fields using the method of thermodynamic integration.94,95 By explicitly computing the free-energy changes and by quantifying the loss of entropy accompanied with increasing membrane deformation, they showed that the entropy of the membrane decreases with increasing size of the localized region subject to the curvature field;95 the authors also showed that the loss of entropy accompanied increasing membrane, thereby, renormalizing the membrane bending rigidity.

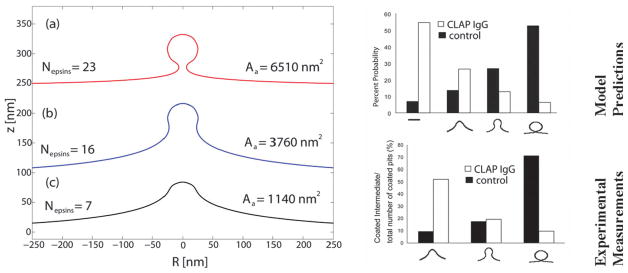

3.3 Model and analysis of curvature induction and epsin localization in CME

Agrawal et al. have explored the role of cooperative protein–protein and protein–membrane interactions in CME and proposed a minimal mesoscale model for protein-mediated vesiculation,125 which addressed how the shapes and energetics of vesicular-bud formation in a planar membrane is stabilized by the presence of the clathrin-coat assembly in CME.125 In their proposed model for CME, the epsins bind to the lattice of a growing clathrin coat through the interaction of the CLAP domain of epsin with the clathrin triskelion. This way, multiple epsins localized spatially and orientationally templated on the clathrin coat collectively play the role of a curvature inducing capsid. In addition, epsin serves as an adaptor in binding the clathrin coat to the membrane through the interaction of its ENTH domain with PIP2 molecules on the membrane. By employing the Helfrich methodology outlined above, they have addressed how the shapes and energetics of vesicular-bud formation in a planar membrane is stabilized by the presence of the epsin/clathrin assembly, see Fig. 4. The results suggest that there exists a critical size of the coat above which a vesicular bud with a constricted neck resembling a mature vesicle is stabilized. The model also provides estimates for the number of epsins involved in stabilizing a coated vesicle (Fig. 4, left) and without any direct fitting reproduces the experimentally observed shapes of vesicular intermediates as well as their probability distributions quantitatively, in wildtype as well as CLAP IgG injected neuronal cell experiments (Fig. 4, right). The model also describes a strong dependence of the vesicle diameter on the bending rigidity. Hence, the authors proposed a unique dual role for the tubulating protein epsin, namely, (1) multiple epsins localized spatially and orientationally template collectively play the role of a curvature inducing capsid; (2) in addition, epsin serves as an adaptor in binding the clathrin coat to the membrane.128 The authors also suggested an important role for the clathrin lattice, namely in the spatial- and orientational-templating of epsins through their interactions with the CLAP domain.

Fig. 4.

(Reproduced with permission from ref. 125) Left: membrane deformation profiles under the influence of imposed curvature of the epsin shell model for three different coat areas, here κ = 20 kBT. For the largest coat area, the membrane shape is reminiscent of a clathrin-coated vesicle. Right: calculated (top) and experimentally measured (bottom) probability of observing a clathrin-coated vesicular bud of given size in WT cells (filled) and CLAP IgG injected cells (unfilled).

3.4 Direct visualization of spatial organization of proteins in CME

Total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy, which uses evanescent waves to gather super-resolution images, is being widely used for live-cell imaging with a combination of spatial and temporal resolution. The recent development of differential evanescence nanometry also enables the tracking of axial localization of specific proteins. The technique utilizes alternating TIRF and wide-field images to determine the axial position for the centroid of a specific protein with ~10 nm resolution and 0.4 Hz temporal resolution. Since the TIRF signal decays exponentially with axial position, and the wide-field signal is dependent only on the fluorophore concentration (and not the axial position), the centroid of a fluorophore ensemble can be calculated from the intensities of the two signals. This technique has been used by Saffarian et al. to study the clustering of AP2 and epsin in budding vesicles.44 Upon fluorescently tagging clathrin, AP-2 and epsin, they established that AP-2 is enriched toward the cytosolic pole of the vesicle while epsin localizes to the rim of the coated pit. Because the neck region of the vesicle is populated by amphiphysin and dynamin as opposed to AP-2, the adaptor’s pole enrichment in relation to clathrin is explained. While sparse imaging data have previously shown epsin localization at the rim of forming vesicles, this evidence was far from conclusive. Since epsin plays a putative role in generating membrane curvature and driving invagination, it is not obvious that the protein may simultaneously play this role and migrate to the edge of CCPs. Thus, to rationalize these experimental observations further, we analyzed the spatial segregation of epsins and AP-2 in the CCP on the basis of a curvature-mediated migration hypothesis, as discussed below. Specifically, based on the results of Agrawal et al.125 (see Fig. 4), if we positioned epsins to be regularly spaced (i.e. 18.5 nm apart) consistent with the clathrin lattice, and evaluated the hypothetical TIR-WF data from this model, the results do not conform to the data of Saffarian et al.44 suggesting that a curved topology of the bud alone cannot explain the epsin enrichment on the vesicle neck. One possible mechanism driving epsin segregation to the neck of a growing vesicle can be epsins colocalizing with Eps15 at the CCP rim, as described earlier. An alternative explanation is based on the hypothesis that epsin induces anisotropic curvature owing to its tubulation property. This raises important implications for the understanding of simultaneous curvature induction and segregation on the membrane, which is discussed next.

3.5 Models of spatial segregation of curvature inducing proteins due to curvature anisotropy

Indeed, studies of membrane curvature inclusions have demonstrated the effect of anisotropy in curvature-inducing proteins.116,117 The membrane-tubulating ability of these proteins suggests significant anisotropy in their method of curvature induction, and both energy-minimization and Monte Carlo simulation approaches have shown that these proteins should tend to cluster at the neck region of a budding vesicle.116,117 This mechanism seems justifiable to rationalize the propensity for the association of the BAR domain, dynamin, or epsin in regions of negative Gaussian curvature.68 Studies of anisotropic inclusions have shown that for certain choices of parameters even anisotropic curvature-inducing proteins can produce spherical buds.116 These models suggest that the uniform spatial distribution of epsins on the clathrin coat (owing to the CLAP domain-mediated interaction) can be responsible for early invagination. However, as the coat matures into a bud, the emergence of a well defined-neck region with negative Gaussian curvature causes the epsins to migrate to the rim along with Eps15, suggesting a rich and dynamic set of events surrounding a nucleating CCP.

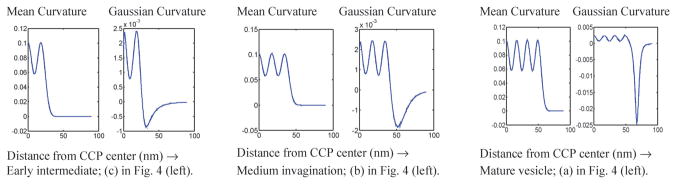

The analysis of the membrane topology from Fig. 4 shows that early membrane invagination is dominated by the emergence of large mean curvature but small negative Gaussian curvature, see Fig. 5 (left), but as the membrane invagination matures to form a well defined vesicle neck, the emergence of neck-regions with large negative Gaussian curvature is suggested, Fig. 5 (middle and right). Membrane invagination clearly produces a highly negative Gaussian curvature in the vesicle neck, and it is reasonable to believe this phenomenon may play a role in regulating the spatiotemporal localization of CME proteins. That is, anisotropy in the curvature-inducing ability of epsin may couple to the Gaussian curvature gradient to provide the energetic impetus for epsin’s migration along a budding vesicle’s neck.

Fig. 5.

Mean and Gaussian curvature profiles during early bud formation, medium membrane invagination, and deep membrane invagination.

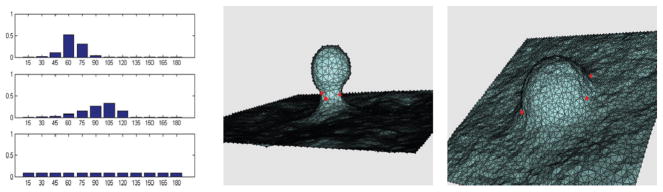

We have explored this possibility by modeling the curvature anisotropy as an elliptical Gaussian with an aspect ratio of 3; this is a variant of eqn (4) in which the bi along one of the orthogonal directions is chosen as 3 times that of the other. For such a model, the orientational angular distributions of epsins (Fig. 6, left) at different stages of bud formation are evaluated in three different scenarios: (1) at the neck of a mature bud (see snapshot in Fig. 6, middle); (2) at the boundary of an intermediate bud (see snapshot in Fig. 6, right); (3) on a planar membrane (snapshot not shown). The results of Fig. 6 suggest that in the presence of curvature anisotropy, increasing the magnitude of negative Gaussian curvature decreases the spread in the angular distribution of epsins, suggesting increased orientational preference of an anisotropic curvature-inducing protein. This analysis indeed reconciles the neck localization of epsin at the later stage of vesicle nucleation with its putative function of generating the initial membrane curvature of the CCP at early stages of invagination.

Fig. 6.

Left: angular distributions, probability P(θ) versus angle θ (°), of epsins; top corresponds to the mature bud, middle corresponds to the early intermediate, and bottom corresponds to a planar membrane. Middle: snapshot of a mature bud; red dots indicate fixed locations of epsins, where the angular distributions were sampled. Right: snapshot of an intermediate bud; red dots indicate fixed locations of epsins, where the angular distributions were sampled.

4. Future outlook

A definitive understanding of the interplay between clathrin coat formation and membrane curvature evolution is emerging but remains incomplete. Though many aspects of CME are well-characterized, especially in the domain of protein–protein interactions and increasingly in the area of protein localization, several open questions remain which are fundamental to a complete understanding of this fundamental cellular process.

4.1 Vesicle scission and uncoating

One major unresolved theme is the mechanism by which anisotropic tubulation properties of proteins sense and induce curvature, as well as how they migrate in the background mean as well as Gaussian curvature gradients as discussed in Section 3. For example, once the membrane-bound amphiphysin has generated a sufficiently high curvature in the neck, GTPase effector domains (GED) of the previously-recruited dynamin are thought to mediate its oligomerization into a helical collar around the vesicle neck.68 Assembly of the dynamin collar immediately precedes vesicle scission in wild-type cells, but the exact mechanism of scission is still debated (see Box 1). Experimental approaches have shown compelling evidence for a GTP-dependent mechanochemical conformation change, yet cell-free experiments seem to suggest that the twisting action itself is insufficient to split a membrane in the absence of sufficient line tension or surface tension. Computational models of CME have suggested a line-tension dependent mechanism mediated by phase separation, and integrative mechanisms dependent on tension, membrane rigidity and binding energetics. After complete CCV budding from the plasma membrane, the clathrin coat is removed from the vesicle. In the initial stage of uncoating, a complex of endophilin and synaptojanin deplete membrane PIP2,40,47 depleting the binding sites available for AP-2. The curvature-sensing capability of endophilin’s N-BAR domain promotes its membrane localization, and endophilin recruits the phosphatase synaptojanin to convert PIP2 into PI(4)P,132 dramatically increasing the vesicle PI(4)P concentration. GAK/auxilin bind the newly-formed PI(4)P via a PTEN-like domain75 and recruit the Hsc70 chaperone protein to the coated vesicle to complete the uncoating process.74–76,133 The formation, regulation, and sub-cellular localization of dynamic clusters or domains of phospholipids (especially PIP2 and PI(4)P) within the various membrane compartments remain unknown.

4.2 Endosomal sorting and downstream processing

Even though the specific methods of post-endocytic cargo sorting are beyond the scope of this review, it has been noted that the sorting of endocytic cargo for either degradation or recycling is dependent on the type of cargo itself, as well as on additional adaptor and accessory proteins retained on the endosomal membrane.134,135 In the specific case of the EGF receptor, the initial method of endocytosis (clathrin vs. caveolinmediated) determines the fate of the receptor; CME leads to receptor recycling while non-clathrin endocytosis (NCE) leads to receptor degradation;54,136,137 however, several open questions remain, as discussed in Section S1, ESI.†

4.3 Distinction between coated pits and coated plaques

Recently, Saffarian et al.44 showed that in mammalian cells, clathrin-coated endocytic complexes can proceed through traditional pits and longer-lasting, flat plaques. As the plaques appear only on the adherent surface of adhesion-competent cell lines and at specific membranous locations on polarized cells (e.g. epithelial cell apical membrane), it is possible that the deviations between plaque and pit morphology occur in response to structural or biophysical stimuli such as cytoskeletally-mediated spatial restriction or differences in membrane rigidity. While we focused exclusively on the CME of coated-pits in this review, we make the important distinction that canonical clathrin-coated pits (CCPs) mature and bud in an actin-independent fashion, while actin and associated proteins are essential in the internalization of coated plaques. A simple geometric model has been advanced to explain why CCPs are likely formed by simultaneous coat formation and coat invagination, rather than by initial flat coat formation with subsequent remodeling into a spherical bud. This view has been supported by imaging studies which depict large evolved stresses in flat clathrin lattices or plaques,44 and by neutron scattering studies emphasizing the intrinsic pucker angle of clathrin triskelia both as monomers and within coats.26 This supports the hypothesis that coated plaques are likely a result of restriction by the cytoskeleton or adhesion complexes. The scope of this review not with standing, the further analysis of coated plaques should remain of scientific and medical interest. Evidence strongly suggests that viral and bacterial entry into mammalian cells proceeds via flat clathrin-coated plaques in an actin-dependent manner,23,138 and further study may yield targets for beneficial pharmacological intervention. The differences between coated pits from coated plaques split the CME into two distinct morphological pathways, yet, its full biological implication in trafficking of cell surface receptors, intracellular adhesion of molecules, and nanocarrier adhesion, is not understood. The reliance of some infections on one pathway or another, for example, makes it important to fully characterize the differences between actin-dependent and actin-independent machinery.

4.4 Structural (all-atom and coarse-grained) modeling of BAR protein

Recent advances in live-cell fluorescent imaging have allowed for accurate recording of the dynamics of specific tagged molecules in vitro,81,139–142 and a newly-developed method utilizing two different microscopic techniques has allowed researchers to analyze spatial localization of these proteins in three dimensions44,143 (albeit in a limited manner). These emerging imaging modalities enable better spatial/temporal resolution in mapping proteins in the context of CME and have raised new challenges in mapping at the single-molecule resolution the interactions in multimeric complexes of the CME.144–154 In addressing the structural challenges at the atomic resolution, all-atom and hierarchically coarse-grained simulations of BAR-domain proteins have been performed.144–149,153,154 The coarse-grained modeling work referenced above represents BAR-domain remodeling at four distinct scales, and at each level of coarse-graining parameters are set such that overall system properties of the coarse-grained simulation match those of the base representation. In order of increasing coarseness is the all-atom simulation, residue-based coarse-graining which preserves the protein secondary structure, shape-based coarse graining which conserves topology and macroscopic protein shape, and a continuum elastic model which conserves final membrane curvature. The coarse-grained simulations represent proteins as ensembles of discrete quasi-particles that deform to seek out the membrane topology corresponding to a free-energy minimum; this model is also parameterized by initial all-atom simulations.144–149

The BAR domain protein simulations have suggested both the physical mechanisms underlying curvature induction, and the ordering of proteins bound to membranes. N-BAR proteins both sense and induce curvature by a combination of H0 helix insertion into the membrane bilayer, and electrostatic scaffolding interaction between the positively-charged concave protein face and the negatively charged membrane.148 By binding at different angles relative to the maximum curvature orientation, N-BAR proteins can more effectively bind to membranes with a range of local curvatures and subsequently bend them closer to the N-BAR intrinsic curvature. To promote scaffolding, their N-terminal domains also orient the proteins such that the concave face always remains facing the membrane.149 F-BAR proteins induce curvature via a distinct mechanism, and thus have different energetic requirements for forming different membrane structures. The simulations of BAR domains also replicate the curvature anisotropy predicted from experimental membrane tubulation studies, offering further evidence for BAR domains to accumulate at the vesicle neck in CME. These simulations further reinforce the importance of PIP2 to successful budding events, since higher PIP2 concentrations facilitate closer association between BAR domains and the membrane.

4.5 Module-based endocytic model for CME

There is ample evidence from siRNA knockdown studies and experiments with different cell lines that several steps of CME are fortified with considerable redundancy. For example, the function of the ubiquitous adaptor AP-2 can be somewhat replaced by the CALM protein, and SNX9 and amphiphysin perform identical membrane-bending and dynamin-clustering roles. Further investigation into the physical mechanism focused on functional modules rather than on each specific protein is thus warranted to gain a “systems” understanding of the endocytic proteins. A whole-endocytosis model takes a very high-level approach to identifying the energetic impetus for clathrin-mediated endocytosis. By organizing groups of endocytic proteins into function-specific modules,72,150 the model implicitly incorporates many players in CME without depending overtly on specific parameters of any protein. In this model, the invagination and vesiculation of a CCV is mediated by the PIP2 balance at different spatial locations of the endocytic bud, which is modeled using a small set of coupled differential equations.151 The constriction of the vesicle neck is caused by the dynamin module, which corresponds to (at least) dynamin and BAR-domain proteins amphiphysin and endophilin. This module is assumed to assemble at the neck, where it protects underlying PIP2 from dephosphorylation, generating a phase separation between the protected region and the unprotected bulk membrane. This separation creates a line tension that works to minimize contact between the two phases, and contact between water and the unprotected phase, which constricts the neck until the vesicle is deeply invaginated. That there is some contribution to budding from line tension has been proposed by experimental researchers,71,152 but the model’s reliance only on tension-induced budding may contradict available evidence of dynamin function. Specifically, the GTP-dependent twisting of helical dynamin suggests mechanoconstriction of the neck, and studies of dynamin-mediated budding in cell-free systems support the pinchase role of dynamin. Dynamin’s mechanism of inducing scission has also been studied via minimal energy surface models, which suggest that the GTP-dependent change in the helical pitch of the dynamin collar may lead to instability and neck collapse.

The budding phase diagrams generated by the Oster model have an interesting connection to the pit/plaque dichotomy recently identified by Saffarian et al.44 Actin-dependent, plaque-like budding occurs on adherent or polarized cell surfaces that are likely characterized by increased rigidity—due to substrate-imposed constraints and the existence of cytoskeletal adhesion complexes, in accordance with the Oster model predictions. In addition, the vesicle morphology for actin-dependent and actin-independent budding in this model also resembles the proposed morphology for plaques and pits, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Insight, innovation, integration.

Intracellular trafficking mechanisms involve the collective interactions between the proteome and the lipidome and are crucial to essential cell functions, including nutrient uptake, cell–cell communication, and membrane homeostasis. These intracellular transport mechanisms regulate and impact receptor regulation, neurotransmission and drug delivery. Unlike established methods in structural biology or optical microscopy, experimental protocols to study cell membrane-mediated signaling are limited: the relevant mesoscale assemblies are too large for atomic resolution and yet fall below the diffraction limit to elude optical methods. In this review article, we discuss the applications of innovative experimental methods based on super-resolution fluorescence, and innovative theoretical/computational methods based on multiscale modeling to access the mesoscale. Through the integration of theory and experiment and simultaneously physical biology and systems biology, we discuss the insight gained into the process of clathrin-mediated endocytosis with respect to structure, assembly, and mechanisms, from biology as well as physics perspectives.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Radhakrishnan, Lemmon, Lazzara, Janmey, and Ferguson laboratories at the University of Pennsylvania for helpful discussions. We acknowledge funding from National Science Foundation CBET-0853539 and CBET-0853389, National Institutes of Health NIBIB-1R01EB006818 and NHLBI-1R01HL087036, and computational support from National Partnerships for Advanced Computational Infrastructure NPACI-MCB060006.

Common abbreviations

- CME

Clathrin Mediated Endocytosis

- CCP

Clathrin-Coated Pits

- CCV

Clathrin-Coated Vesicle

- EGFR

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor

- AP-2

Adaptor Protein 2

- PIP2

Phosphatidylinositol-bisphosphate

- MC

Monte Carlo

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/c1ib00036e

References

- 1.Oved S, Yarden Y. Nature. 2002;416:133–136. doi: 10.1038/416133a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmidt AA. Nature. 2002;419:347–348. doi: 10.1038/419347a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirchhausen T. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:187–198. doi: 10.1038/35043117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sigismund S, Woelk T, Puri C, Maspero E, Tacchetti C, Transidico P, Di Fiore PP, Polo S. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2760–2765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409817102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marsh M. Endocytosis. Oxford University Press; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aguilar RC, Wendland B. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2679–2680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500213102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farsad K, De Camilli P. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:372–381. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korolchuk V, Banting G. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:857–860. doi: 10.1042/bst0310857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sorkin A, Von Zastrow M. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:600–614. doi: 10.1038/nrm883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miwako I, Schmid SL. Methods Enzymol. 2005;404:503–511. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)04044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teis D, Huber LA. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:2020–2033. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3010-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parton RG, Richards AA. Traffic (Oxford, U K) 2003;4:724–738. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bache KG, Slagsvold T, Stenmark H. EMBO J. 2004;23:2707–2712. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polo S, Pece S, Di Fiore PP. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:156–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Floyd S, Camilli PD. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:299–301. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01316-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linggi B, Carpenter G. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:649–656. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hahn CG, Wang HY, Cho DS, Talbot K, Gur RE, Berrettini WH, Bakshi K, Kamins J, Borgmann-Winter KE, Siegel SJ, Gallop RJ, Arnold SE. Nat Med (N Y) 2006;12:824–828. doi: 10.1038/nm1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arnold SE, Talbot K, Hahn CG. Prog Brain Res. 2005;147:319–345. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(04)47023-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kavalali ET. Neuroscientist. 2006;12:57–66. doi: 10.1177/1073858405281852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cossart P, Veiga E. J Microsc (Oxford, U K) 2008;231:524–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2008.02065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eto DS, Gordon HB, Dhakal BK, Jones TA, Mulvey MA. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:2553–2567. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veiga E, Cossart P. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:894. doi: 10.1038/ncb1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Veiga E, Guttman JA, Bonazzi M, Boucrot E, Toledo-Arana A, Lin AE, Enninga J, Pizarro-Cerda J, Finlay BB, Kirchhausen T, Cossart P. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:340–351. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young A. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18:448–458. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mousavi SA, Malerod L, Berg T, Kjeken R. Biochem J. 2004;377:1–16. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferguson ML, Prasad K, Boukari H, Sackett DL, Krueger S, Lafer EM, Nossal R. Biophys J. 2008;95:1945–1955. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.126342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirst J, Sahlender DA, Li S, Lubben NB, Borner GHH, Robinson MS. Traffic (Oxford, U K) 2008;9:1354–1371. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00764.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hao WH, Luo Z, Zheng L, Prasad K, Lafer EM. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22785–22794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morgan JR, Prasad K, Jin SP, Augustine GJ, Lafer EM. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:33583–33592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304346200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang B, Ganetzky B, Bellen HJ, Murthy VN. Neuron. 1999;23:419–422. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80794-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hinrichsen L, Meyerhoiz A, Groos S, Ungewickell EJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8715–8720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600312103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wakeham DE, Chen CY, Greene B, Hwang PK, Brodsky FM. EMBO J. 2003;22:4980–4990. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conner SD, Schroter T, Schmid SL. Traffic (Oxford, U K) 2003;4:885–890. doi: 10.1046/j.1398-9219.2003.0142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Collins BM, McCoy AJ, Kent HM, Evans PR, Owen DJ. Cell (Cambridge, Mass) 2002;109:523–535. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00735-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henne WM, Boucrot E, Meinecke M, Evergren E, Vallis Y, Mittal R, McMahon HT. Science. 2010;328:1281–1284. doi: 10.1126/science.1188462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ungewickell EJ, Hinrichsen L. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:417–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ricotta D, Conner SD, Schmid SL, von Figura K, Honing S. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:791–795. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200111068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krauss M, Kukhtina V, Pechstein A, Haucke V. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11934–11939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510306103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanabe K, Torii T, Natsume W, Braesch-Andersen S, Watanabe T, Satake M. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:1617–1628. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hopper NA, O’Connor V. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:454–456. doi: 10.1038/ncb0505-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Irie F, Okuno M, Pasquale EB, Yamaguchi Y. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:U501–U569. doi: 10.1038/ncb1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zoncu R, Perera RM, Sebastian R, Nakatsu F, Chen H, Balla T, Ayala G, Toomre D, De Camilli PV. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3793–3798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611733104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kirchhausen T. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:596–605. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saffarian S, Cocucci E, Kirchhausen T. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000191. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Semerdjieva S, Shortt B, Maxwell E, Singh S, Fonarev P, Hansen J, Schiavo G, Grant BD, Smythe E. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:499–511. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200806016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ringstad N, Gad H, Low P, Di Paolo G, Brodin L, Shupliakov O, De Camilli P. Neuron. 1999;24:143–154. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80828-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Song W, Zinsmaier KE. Neuron. 2003;40:665–667. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00726-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Benmerah A, Gagnon J, Begue B, Megarbane B, Dautry-Varsat A, Cerf-Bensussan N. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1831–1838. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Benmerah A, Lamaze C, Begue B, Schmid SL, Dautry-Varsat A, Cerf-Bensussan N. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:1055–1062. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.5.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Praefcke GJ, Ford MG, Schmid EM, Olesen LE, Gallop JL, Peak-Chew SY, Vallis Y, Babu MM, Mills IG, McMahon HT. EMBO J. 2004;23:4371–4383. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koh TW, Korolchuk VI, Wairkar YP, Jiao W, Evergren E, Pan HL, Zhou Y, Venken KJT, Shupliakov O, Robinson IM, O’Kane CJ, Bellen HJ. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:309–322. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200701030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sengar AS, Wang W, Bishay J, Cohen S, Egan SE. EMBO J. 1999;18:1159–1171. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.vanDelft S, Schumacher C, Hage W, Verkleij AJ, Henegouwen P. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:811–821. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.4.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Melker AA, van der Horst G, Borst J. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:55465–55473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409765200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Confalonieri S, Salcini AE, Puri C, Tacchetti C, Di Fiore PP. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:905–911. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.4.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Henegouwen P. Cell Commun Signaling. 2009;7 doi: 10.1186/1478-811x-7-24. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yoon Y, Tong JS, Lee PJ, Albanese A, Bhardwaj N, Kallberg M, Digman MA, Lu H, Gratton E, Shin YK, Cho W. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:531–540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.068015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen H, De Camilli P. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2766–2771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409719102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hawryluk MJ, Keyel PA, Mishra SK, Watkins SC, Heuser JE, Traub LM. Traffic (Oxford, U K) 2006;7:262–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang FT, Khvorova A, Marshall W, Sorkin A. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16657–16661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400046200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McMahon HT, Wigge P, Smith C. FEBS Lett. 1997;413:319–322. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00928-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yoshida Y, Kinuta M, Abe T, Liang S, Araki K, Cremona O, Di Paolo G, Moriyama Y, Yasuda T, De Camilli P, Takei K. EMBO J. 2004;23:3483–3491. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sever S, Skoch J, Newmyer S, Ramachandran R, Ko D, McKee M, Bouley R, Ausiello D, Hyman BT, Bacskai BJ. EMBO J. 2006;25:4163–4174. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Takei K, Slepnev VI, Haucke V, De Camilli P. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:33–39. doi: 10.1038/9004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lundmark R, Carlsson SR. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:46772–46781. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307334200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lundmark R, Carlsson SR. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:42694–42702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407430200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Soulet F, Yarar D, Leonard M, Schmid SL. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:2058–2067. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-11-1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fournier JB, Dommersnes PG, Galatola PC. R Biol. 2003;326:467–476. doi: 10.1016/s1631-0691(03)00096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Roux A, Uyhazi K, Frost A, De Camilli P. Nature. 2006;441:528–531. doi: 10.1038/nature04718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Danino D, Moon KH, Hinshaw JE. J Struct Biol. 2004;147:259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kozlov MM. Biophys J. 1999;77:604–616. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)76917-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu J, Kaksonen M, Drubin DG, Oster G. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10277–10282. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601045103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rusk N, Le PU, Mariggio S, Guay G, Lurisci C, Nabi IR, Corda D, Symons M. Curr Biol. 2003;13:659–663. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Massol RH, Boll W, Griffin AM, Kirchhausen T. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10265–10270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603369103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lee DW, Wu XF, Eisenberg E, Greene LE. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3502–3512. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang CX, Engqvist-Goldstein AEY, Carreno S, Owen DJ, Smythe E, Drubin DG. Traffic (Oxford, U K) 2005;6:1103–1113. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ehrlich M, Boll W, van Oijen A, Hariharan R, Chandran K, Nibert ML, Kirchhausen T. Cell (Cambridge, Mass) 2004;118:591–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Conner SD, Schmid SL. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:773–779. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200304069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Edeling MA, Mishra SK, Keyel PA, Steinhauser AL, Collins BM, Roth R, Heuser JE, Owen DJ, Traub LM. Dev Cell. 2006;10:329–342. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rappoport JZ, Kemal S, Benmerah A, Simon SM. Am J Physiol. 2006;291:C1072–C1081. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00160.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rappoport JZ. Biochem J. 2008;412:415–423. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Loerke D, Mettlen M, Yarar D, Jaqaman K, Jaqaman H, Danuser G, Schmid SL. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:628–639. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nossal R. Traffic (Oxford, U K) 2001;2:138–147. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2001.020208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nossal R. Macromol Symp. 2004;219:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wu XF, Zhao XH, Baylor L, Kaushal S, Eisenberg E, Greene LE. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:291–300. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200104085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wu XF, Zhao XH, Puertollano R, Bonifacino JS, Eisenberg E, Greene LE. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:516–528. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-06-0353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Greene B, Liu SH, Wilde A, Brodsky FM. Traffic (Oxford, U K) 2000;1:69–75. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Izaguirre JA, Chaturvedi R, Huang C, Cickovski T, Coffland J, Thomas G, Forgacs G, Alber M, Hentschel G, Newman SAJA. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(7):1129–1137. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Krauss M, Kinuta M, Wenk MR, De Camilli P, Takei K, Haucke V. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:113–124. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200301006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Stachowiak JC, Hayden CC, Sasaki DY. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7781–7786. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913306107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lundmark R, Carlsson SR. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2010;21:363–370. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Legendre-Guillemin V, Wasiak S, Hussain NK, Angers A, McPherson PS. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:9–18. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rao YJ, Ma QJ, Vahedi-Faridi A, Sundborger A, Pechstein A, Puchkov D, Luo L, Shupliakov O, Saenger W, Haucke V. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:8213–8218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003478107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Agrawal NJ, Weinstein J, Radhakrishnan R. Mol Phys. 2008;106:1913–1923. doi: 10.1080/00268970802365990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Agrawal NJ, Radhakrishnan R. Phys Rev E: Stat, Nonlinear, Soft Matter Phys. 2009;80:011925. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.80.011925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kozlov MM. Nature. 2007;447:387–389. doi: 10.1038/447387a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Helfrich W. Z Naturforsch, C: Biochem, Biophys, Biol, Virol. 1973;28:693–703. doi: 10.1515/znc-1973-11-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Stokke BT, Mikkelsen A, Elgsaeter A. Eur Biophys J Biophys Lett. 1986;13:203–218. doi: 10.1007/BF00260368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Stokke BT, Mikkelsen A, Elgsaeter A. Eur Biophys J Biophys Lett. 1986;13:219–233. doi: 10.1007/BF00260369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lawrence CLL, Frank LHB. Phys Rev Lett. 2004;93:256001. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pinnow HA, Helfrich W. Eur Phys J E: Soft Matter Biol Phys. 2000;3:149–157. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cai W, Lubensky TC. Phys Rev E: Stat Phys, Plasmas, Fluids, Relat Interdiscip Top. 1995;52:4251. doi: 10.1103/physreve.52.4251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Veksler A, Gov NS. Biophys J. 2007;93:3798–3810. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.113282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shkulipa SA, den Otter WK, Briels WJ. J Chem Phys. 2006;125:234905–234911. doi: 10.1063/1.2402919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Seifert U, Langer SA. Europhys Lett. 1993;23:71–76. [Google Scholar]

- 106.den Otter WK, Shkulipa SA. Biophys J. 2007;93:423–433. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.105395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gao H, Shi W, Freund LB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9469–9474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503879102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ramakrishnan N, Kumar PBS, Ipsen JH. Phys Rev E: Stat, Nonlinear, Soft Matter Phys. 2010;81:041922. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.81.041922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Roux A, Koster G, Lenz M, Sorre B, Manneville JB, Nassoy P, Bassereau P. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4141–4146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913734107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Divet F, Danker G, Misbah C. Phys Rev E: Stat Phys, Plasmas, Fluids, Relat Interdiscip Top. 2005;72:041901. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.72.041901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Divet F, Biben T, Cantat I, Stephanou A, Fourcade B, Misbah C. Europhys Lett. 2002;60:795–801. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Naji A, Brown FLH. J Chem Phys. 2007;126:235103–235116. doi: 10.1063/1.2739526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Reister-Gottfried E, Leitenberger SM, Seifert U. Phys Rev E: Stat Phys, Plasmas, Fluids, Relat Interdiscip Top. 2007;75:11. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Atilgan E, Sun SX. J Chem Phys. 2007;126:095102. doi: 10.1063/1.2483862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Reynwar BJ, Illya G, Harmandaris VA, Muller MM, Kremer K, Deserno M. Nature. 2007;447:461–464. doi: 10.1038/nature05840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bohinc K, Lombardo D, Kralj-Iglic V, Fosnaric M, May S, Pernu F, Hagerstrand H, Iglic A. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2006;11:90–101. doi: 10.2478/s11658-006-0009-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Iglic A, Babnik B, Bohinc K, Fosnaric M, Hagerstrand H, Kralj-Iglic V. J Biomech. 2007;40:579–585. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.McMahon HT, Gallop JL. Nature. 2005;438:590–596. doi: 10.1038/nature04396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Baumgart T, Das S, Webb WW, Jenkins JT. Biophys J. 2005;89:1067–1080. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.049692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Baumgart T, Hess ST, Webb WW. Nature. 2003;425:821–824. doi: 10.1038/nature02013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Capraro BR, Yoon Y, Cho W, Baumgart T. J Am Chem Soc. 132:1200–1201. doi: 10.1021/ja907936c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]