Abstract

Many adolescents have chronic exposure to hazardous levels of alcohol. This is likely to be a significant predictor of health outcomes, including those related to immunity. We assessed substance use and biochemical immunological parameters in heavy drinking adolescents (meeting DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence) and light/non-drinking control adolescents in Cape Town. Lifetime alcohol dose, measured in standard units of alcohol, was orders of magnitude higher in alcohol dependent (AD) participants than controls. All adolescent AD had a ‘weekends-only’ style of alcohol consumption. The AD group was chosen to represent relatively ‘pure’ AD, with minimal other drug use and no psychiatric diagnoses. With these narrow parameters in place, we found that AD adolescents were lymphopenic compared to controls, with significantly lower mean numbers of absolute circulating CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ T-lymphocytes. Upon conclusion, we found that adolescent AD individuals with excessive alcohol intake, in a weekend binge-drinking style but without comorbid drug or psychiatric disorders, may be at increased risk of lymphopenia. This alcohol misuse may increase infectious disease susceptibility (including TB and HIV) by reducing immune system capabilities. Complex interactions of alcohol with other documented high-risk activities may further compound health risks.

Keywords: adolescents, alcohol, immunity

INTRODUCTION

Chronic exposure to hazardous levels of alcohol is typical for an alarming proportion of school-going adolescents internationally and in South Africa (Kim et al., 2008; Kuntsche et al., 2004; Lim et al., 2007; Parry et al., 2004; Reddy et al., 2003; United States Department of Health and Human Services. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Office of Applied Studies, 2005). This harmful alcohol intake may impact health outcomes, including those related to immune function. The quantity of alcohol consumed, the frequency with which it is consumed, and the pattern of consumption determine the health and related effects of alcohol use (Li, 2008). Binge drinking is defined as consuming five or more drinks (male) or four or more drinks (female) in approximately 2 hours (NIAAA, 2004). This high-risk drinking pattern occurs frequently in adolescents and can result in damage due to a number of acute and chronic consequences that affect health (Li, 2008).

South African surveillance shows binge drinking to be a common form of substance misuse among school-going youth of both genders, with over a third of the males in Cape Town reporting binge drinking by grade 11 (Parry et al., 2004). Recent (past month) alcohol use (particularly weekend binge-drinking) has been reported by 31.7% of school-going adolescents in the Cape Town area (Flisher et al., 2003).

It is well documented that excessive alcohol intake results in compromised immunity and increased risk of infections (Cook, 1998; Happel and Nelson, 2005; MacGregor and Louria, 1997; Messingham et al., 2002; Nelson and Kolls, 2002; Szabo, 1999). The effects of alcohol on immunity have largely been demonstrated in vivo in mice and rats (Szabo and Mandrekar, 2009). Research with acute and chronic ethanol-fed C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice has demonstrated a significant reduction in splenic cellularity, CD4+ T-cell numbers, CD8+ T-cell numbers, B cell numbers and Natural Killer (NK) cell numbers (Meadows et al., 1989; 1992; Shellito and Olariu, 1998; Song et al., 2002; Starkenburg et al., 2001; Zhang and Meadows, 2005). Most studies in humans investigating the impact of alcohol use on measures of immunity have been conducted in samples of chronically alcohol-dependant adults in treatment facilities, with varying degrees of medical, externalizing, and other substance use problems (Charpentier et al., 1984; Cook, 1998; 1995; 1997; 1996; Mutchnick and Lee, 1988; Roselle et al., 1988; Schleifer et al., 2002). Due to the possible interactive effects of other substances commonly used by persons with alcohol use disorders (AUDs), the possibility exists that effects on immunity observed may not be directly attributable to alcohol consumption.

Alcohol can disturb the complex process of host immunity through its modulating effects on the different cellular components of the adaptive and/or innate immune systems (Brown et al., 2006; Cook, 1998; Szabo, 1999). Studies have revealed that alcoholics without liver disease typically have normal numbers of lymphocytes in their peripheral blood, whereas those with liver disease have a wide range of abnormalities, depending on the stage and severity of disease. In alcoholic liver disease, there is lymphopenia in the later stages of cirrhosis (Cook, 1998).

Through research into the effects of alcohol use, it has become clear that age is an important factor influencing its impact (Matthews, 2010). Relatively little is known about the effects of alcohol and, more specifically, binge-drinking on immunity in adolescents. The paucity of information in this regard is concerning in light of documented increases in alcohol consumption among adolescents (Matthews, 2010; McArdle, 2008).

Adolescence is associated with higher rates of risk-taking behaviours, exposure to high-risk environments, and vulnerability to experimentation. South African youth risk-taking behaviours include under-age alcohol use, tobacco and other drug experimentation, and engagement in unprotected sex (Reddy et al., 2003).

The Cape Town region of South Africa provides an opportunity to study adolescents meeting criteria for AD, but with minimal other drug use histories. The inclusion of adolescents without co-morbid externalizing disorders or substance use disorders (SUDs), including regular cigarette smoking, allows for the examination of the effects of alcohol on lymphocytes without the confounding effects of other substance abuse. To our knowledge, no studies examining the effects of alcohol use on lymphocytes in treatment-naive, community-dwelling adolescents with AD and with no co-morbid SUDs have been published. The aim of this study was to explore the effect of adolescent AD on lymphocytes by examining and comparing quantitative in vivo parameters in treatment-naïve 13–15 year old adolescents with AD, but without co-morbid other SUDs or externalizing disorders, with light/non-drinking control adolescents, from the same well-defined and homogenous study population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population and Participants

The current study examined a subset of participants recruited for a larger study (n=127) of relatively ‘pure’ adolescent AUD without concomitant drug use or psychiatric (including externalizing) diagnoses. In the parent study, participants were mixed ancestry English or Afrikaans-speaking adolescents (ages 12–15 years) from schools within a 25-km radius of the single test site at Tygerberg Hospital. Participants were individually matched for age (within 1 year), gender, education level, language, and socioeconomic status. Screening procedures included a structured psychiatric diagnostic interview, a developmental and medical history (from participants and at least one biological parent or legal guardian) and a detailed physical and neurological examination that included anthropometry, assessment for stigmata of nutritional deficiencies and developmental delays (PDC). The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Aged Children (6–18 Years) Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL) (Kaufman et al., 1996) was used to ascertain current and past psychiatric diagnoses. The Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcohol (SSAGA-II) (Bucholz et al., 1994) was used to confirm AUD diagnosis and to derive detailed substance use histories (alcohol, tobacco and all other drugs).

Participants were assigned to one of two groups: an AD group meeting DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) or a light/non-drinking control group (lifetime dose of <100 standard units of alcohol or never consumed alcohol). Exclusion criteria for both groups were: mental retardation, current DSM-IV Axis I diagnoses other than AD and lifetime diagnoses of psychoses, severe mood disorders (current and lifetime), ADHD, conduct disorders and SUDs other than alcohol, current use of sedative or psychotropic medication, signs or history of fetal alcohol syndrome or malnutrition, sensory impairment, history of traumatic brain injury with loss of consciousness exceeding 10 minutes, presence of diseases that may affect the CNS (e.g., meningitis, epilepsy), HIV (tested using the enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)), less than 6 years of formal education, and lack of proficiency in English or Afrikaans. At the consent explanation interview, a social worker obtained collateral information from consenting parents, verifying the absence of medical, psychiatric and psychosocial problems. The mean age of the parent sample was 14.80 years and females (54%) slightly outnumbered males (46%). The parent sample consisted of 43% non-smokers (never smoked), 32% light smokers (<100 cigarettes in their lifetime) and 25% regular smokers (>100 cigarettes in their lifetime). The primary aim of the parent study was to explore the effects of heavy alcohol use on brain structure and function via the study of relatively pure untreated adolescent AUDs without comorbid Substance Use Disorders or comorbid psychiatric disorders (including externalizing disorders).

The sub-sample of 37 males and females (ages 13–15 years) in the current study was selected consecutively from the parent study sample according to whether individuals still required blood collection and were non-smokers or light smokers. Regular smokers were excluded. Blood collection for the immune measures was done on the same occasion as the additional blood collection for the parent study. Two participants refused the additional blood collection. Participants in the sub-sample were from 7 schools within a 25-km radius of the single test site. The AD (n=18) and light/non-drinking control (n=19) groups had a mean age of 14.70 years (±0.62) with no differences between groups. Males (60%) outnumbered females (40%), and the majority of the sample were Afrikaans-speakers (78%). Half of the total sample consisted of non-smokers (51%) and the other half were light smokers (49%). The majority of participants (73%) in the sample had never experimented with cannabis and none of the participants had experimented with any other drugs.

Measures

Substance use

A revised version of the Timeline Follow-back procedure (TLFB) (Sobell and Sobell, 1992), a semi-structured, clinician-administered assessment of lifetime history of alcohol use and drinking patterns (i.e., frequency, quantity and density of alcohol consumption, including every phase from when participants first started drinking at least once per month to the present, including all periods of sobriety) was used in collaboration with the K-SADS-PL to elicit alcohol-use data. It was administered by a trained Psychiatrist on the day of screening. During a pre-screening phase, potential participants were asked to write down their patterns and quantity of alcohol consumption. During the screening and the TLFB interview, the clinician compared alcohol consumption reported in the pre-screen and the TLFB procedure. Participants with great discrepancies between the pre-screen and screen report were excluded due to possible response bias. On the day of blood sample collection, alcohol use during the preceding week was determined, including quantity and alcohol type for each of the seven days. A standard drink was defined as one beer or wine cooler (340ml), one glass of wine (150ml) or a 45ml shot of liquor.

Blood collection and sample preparation

EDTA venous blood samples (5 ml) for the immunological assays were collected from each participant at the various schools via venipuncture in the morning and delivered to the laboratory within 2 hours. The following parameters were measured for each participant: total T-cells (CD3+), the T cell subsets CD4+ (T helper) and CD8+ (T-cytotoxic), CD4+:CD8+ ratio, T-regulatory cells (CD3+CD4+CD25+CD62L+), NK Cell activity determined at 50:1, 25:1 and 12:1 (effector to target ratios).

Immunological biochemistry

The fresh blood received within the laboratory was processed for flow cytometric analyses TrueCount tubes (containing defined beads in order to calculate absolute cell numbers) that use multi-colour staining and single platform technology (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, California). Well mixed blood (50 µl) was incubated with the mixture of monoclonal antibodies defining discreet subsets of the T cells. The commercial antibody mixture (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, California) contained antibodies reacting to the following lymphocyte subsets: CD45+, CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+. A lyse no-wash method was use and samples were analyzed on a FACS Calibur flow cytometer using MultiTest software. Results are expressed as % Positive cells as well as absolute cell counts per µl blood.

For the determination of the T-regulatory subset, a mixture of anti-CD3, anti-CD4, anti-CD25 and anti-CD62L antibodies were used to define the cells which are of T-helper cell phenotype (CD3+CD4+) expressing high densities of CD25 and CD62L markers. This subset of T-cells correlate well with T-regulatory cells defined by their FoxP3 positivity as reported by other authors.

Natural killer (NK) cell activity was conducted using the K562 cell line: peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were prepared from the blood samples by density gradient centrifugation. The PBMCs were washed, counted and incubated at various ratios (50:1, 25:1 and 12:1) with the K562 cells at 37°C and 5% CO2. After 4 hours, Propidium Iodide was added to determine which cells had died during the co-culture: the flow cytometric method was used and involved a gating strategy identifying the K562 cells (these cells vary by size to the PBMCs) and, when compared to “control” cultures (K562 cells alone), the various ratios of cells could be analysed. The results were expressed as % Cell death (% cell lysis).

Procedures

The Committee for Human Research of Stellenbosch University approved all study procedures. After eligibility was established, written consent from parents and written assent from participants was obtained. Participants were transported from their homes or schools to the testing site. After physical and psychiatric screening, urine analysis and breathalyzer testing, the participants completed demographic self-report questionnaires. On a Monday, between 1 and 6 weeks after the screening and inclusion procedures at the testing site, the researchers visited the participants at the 7 schools to collect blood samples and the alcohol use data for the preceding 7 days. Mondays were selected in order to obtain the blood samples as soon as possible after the typical weekends-only alcohol consumption style observed in this population. Participants were provided with meals and refreshments and, at the conclusion of the testing sessions, were compensated for their time with gift vouchers. Confidentiality of all study information was maintained with the exception of statutory reporting requirements in newly-identified or ongoing threats to the safety of minor participants.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS (SPSS Inc., 2008). The Fisher's exact test was used to examine the significance of the associations between categorical variables. Two-way ANOVAs (Group by Gender) were performed on each dependent variable using the General Linear Model procedure, and partial eta squared was computed as a measure of effect size. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to confirm that effects were robust to ANOVA assumptions. Associations between ordinal/continuous variables were tested with Spearman’s rank order correlation coefficients. A 5% significance level (p<0.05) was used as guideline for determining significant differences.

RESULTS

Demographic and substance use characteristics (Table 1)

Table 1.

Demographic and Substance Use

| AD Group | Control Group | Effect Sizeb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n= 18) | (n = 19) | Partial Eta | Odds | |

| M (SD) or % | M (SD) or % | Squared | Ratio | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (in years) | 14.8 (0.5) | 14.6 (0.7) | 3.5 | |

| Gender Ratio (M/F) | 10/8 | 11/8 | 0.96 | |

| Alcohol Use | ||||

| % Never consumed alcohol | 0% | 47% | ||

| %Never intoxicated | 0% | 95% | ||

| Age at first alcohol use | 12.0 (2.2) | 13.0 (1.3) (n=10) | 6.0 | |

| Alcohol lifetime dose (standard units) | 1296 (1577) | 2 (3) | 26.8a | |

| Age at first intoxication | 12.8 (1.4) | N/A | ||

| Age of onset of regular drinking | 12.9 (1.4) | N/A | ||

| % Weekends-only alcohol style | 100% | N/A | ||

| Frequency of alcohol intake (days per month) in most recent drinking phase | 4.2 (2) | N/A | ||

| % Subjects who drank in week preceding blood collection | 22.2% | 5.3% | 4.2 | |

| Other Substance Use | ||||

| % Smoked tobacco | 61% | 37% | 1.7 | |

| % Lifetime >100 cigarettes | 0% | 0% | ||

| Lifetime tobacco dose | 16.1 (28.2) | 2.5 (6.9) | 10.7* | |

| % Used cannabis | 39% | 10.5% | 3.2 | |

| Lifetime cannabis dose | .83 (1.3) | .16 (0.5) | 12.0* | |

| % Never used any other drugs | 100% | 100% | ||

Difference between groups is significant (by either F test or Mann-Whitney U test).

p≤0.05,

p≤0.01

Statistical comparisons are not valid for variables associated with group selection criteria.

Partial Eta Squared - percent of variance of dependent variable accounted for by group membership

All adolescents in the sample were deemed generally healthy following a medical and neurological examination by a psychiatrist. The groups were comparable in age and gender distribution. Almost half of the adolescents in the control group had never had alcohol and all, except one, had never been intoxicated. In participants that had ever used alcohol, groups did not differ in the age of onset of drinking. All adolescents in the AD group had a ‘weekends-only’ style of alcohol consumption. Only 4 AD and 1 control participant had consumed alcohol in the 7 days preceding the Monday when blood samples were collected. The mean frequency of alcohol consumption during the most recent phase of drinking in the AD group was about 4 days per month. Experimentation with tobacco and cannabis was low in both groups.

Lymphocyte measures (Table 2)

Table 2.

Immunology Measures

| AD Group | Control Group | Effect size | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n=18) | (n=19) | ||

| Immune Measures | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| T-cell CD3+ (%) | 63.6 (6.8) | 62.4 (3.9) | 2.3 |

| T-cell CD4+ (%) | 38.3 (5.4) | 35.8 (5.1) | 3.8 |

| T-cell CD8+ (%) | 21.0 (6.5) | 22.7 (5.5) | 0.8 |

| T-cell CD3+ (cells per microlitre) | 1273 (356) | 1620 (415) | 15.2** |

| T-cell CD4+ (cells per microlitre) | 749 (241) | 916 (229) | 11.4* |

| T-cell CD8+ (cells per microlitre) | 438 (165) | 598 (231) | 11.5* |

| CD4+ to CD8+Ratio | 2.0 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.7) | 3.2 |

| T-regulatory cells (%) | 12.6 (5.0) | 13.7 (8.2) | 0.3 |

| Natural Killer Cell Activity-50 (%) | 16.9 (5.3) | 16.1 (7.2) | 1.4 |

| Natural Killer Cell Activity-25 (%) | 18.4 (6.6) | 19.2 (11.3) | 0 |

| Natural Killer Cell Activity-12 (%) | 17.8 (6.6) | 21.5 (14.8) | 1.7 |

Difference between groups is significant (by either F test or Mann Whitney U Test).

p<0.05;

p<0.01

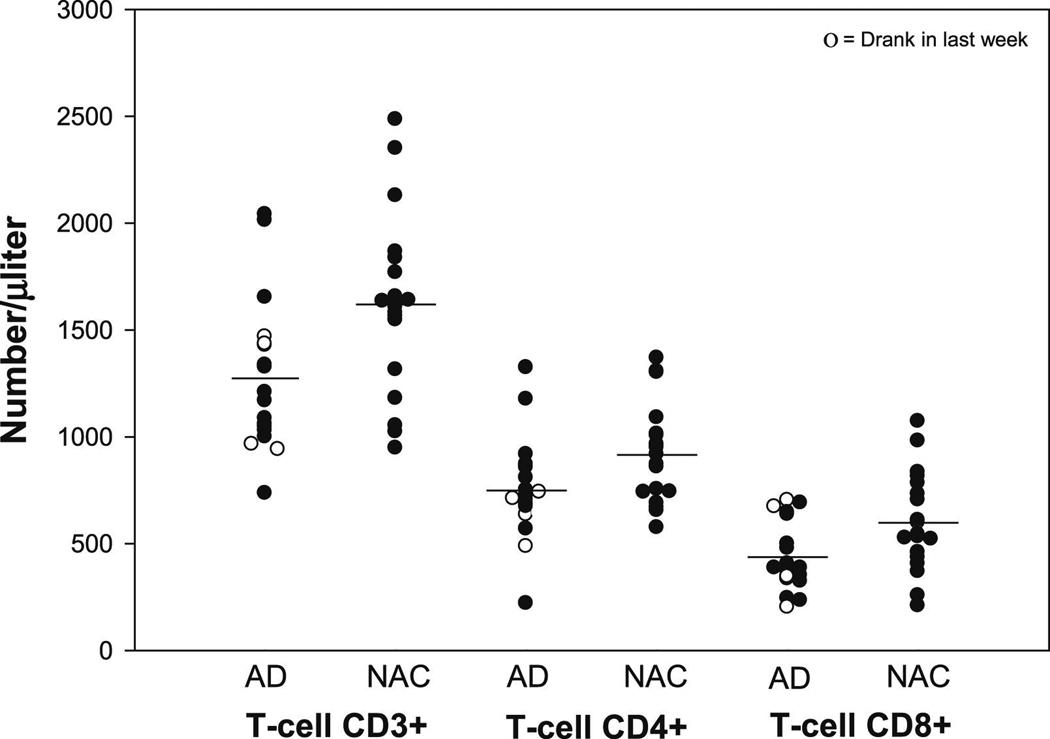

Adolescents in the AD group had a significantly lower mean number of absolute circulating CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ T-lymphocytes. Overall, the AD group was lymphopenic when compared with controls. There were no significant differences between groups for the CD4+:CD8+ ratio, levels of T-regulatory cells and NK cell activity.

The CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ T-lymphocyte cell counts are presented in Figure 1, in which the AD adolescents who used alcohol in the week preceding the blood sample collections are indicated.

Figure 1.

Scatter plots representing the distributions and differences in CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ T-lymphocyte subsets between the alcohol dependence (AD) (n=18) and light/nondrinking control (NAC) (n=19) groups. Adolescents in the AD group had significantly lower mean numbers of CD3+ (p= 0.01), CD4+ (p= 0.03) and CD8+ (p= 0.02) T-lymphocytes than those in the control group. The plots also show the CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ cell counts for the few adolescents who used alcohol in the week and weekend (seven days) preceding the Monday of blood sample collections. The distributions of these cell counts in the AD adolescents who consumed alcohol in the preceding week appeared no different to those of the AD adolescents who did not drink in the preceding week. All cell counts are shown as absolute cell counts per microlitre.

When analyzing associations between alcohol use and immune measures within the AD group, no significant correlations were found. However, there were trends towards inverse correlations between average standard units of alcohol consumed per month and absolute circulating CD8+ (r = −0.40; p=0.10).

DISCUSSION

We report here on the reduction of T-lymphocyte counts in a sample of healthy, treatment-naive adolescents with “pure” alcohol dependence (without comorbid substance use disorders or comorbid psychiatric, including externalizing, disorders) compared to light/non-drinking adolescent controls. Groups were age and gender comparable and consisted of non-smokers or light mokers. The average age of regular drinking and first intoxication was towards the end of the 12th year.

An individual’s exposure to alcohol (quantity and duration) is one of the mediating factors in the risk for alcohol-related effects (Li, 2008). Alcohol consumed per month was less than half that reported in a sample of adolescents in the United States (US) (Tapert and Brown, 1999) (57 standard drinks per month vs. 131 standard drinks per month). The AD adolescents in our sample had a similar pattern of weekend binge-drinking as is commonly found in the United States (Moss et al., 1994). Our adolescent sample was generally healthy with no clinical physical sequallae of alcohol abuse being evident.

The immunologic findings reported here suggest that heavy alcohol use in alcohol dependent adolescents is associated with reduced numbers of circulating total T-lymphocytes (CD3+) and T-lymphocyte subsets CD4+ (T helper) and CD8+ (T-cytotoxic). The relatively unique aspects of the current AD sample (i.e., the lack of comorbid substance use or psychiatric, including externalizing, disorders), suggests that the reduced cellular immune capacity is likely an effect of heavy alcohol use and alcohol dependence, per se, and not a result that can be attributed to the usual comorbidities that accompany adolescent AD in most settings. Moreover, the fact that very few of the AD sample used alcohol in the week preceding the Monday blood sample collections suggests that the effects are the result of chronic rather than acute alcohol abuse. It is possible that the effects would have been larger were data collected after a week of heavy alcohol use. It is also likely that effects would be greater in adolescent samples in the US, since alcohol use is higher and comorbidity effects would also be present (Brown et al., 2000; Tapert and Brown, 2000). Although the distributions of the CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ cell counts in the AD adolescents who consumed alcohol in the preceding week appeared no different to those of the AD adolescents who did not drink in the preceding week (Figure 1), the subset who had consumed alcohol was very small and the comparison between subsets had minimal power. As reported, all AD participants had a weekends-only drinking style and the mean drinking frequency of this group was about 4 days per month. Some AD participants reported drinking only 2 days per month in the most recent drinking phase, indicating that although they drink only during weekends, they may not drink every weekend. This could explain the lower than expected number of participants that consumed alcohol intake in the week preceding the Monday blood draw. Another probable explanation is that most of the blood collection was done just prior to the start of school year-end examinations, which may have resulted in less social interaction and more firm parental control over these weekends, reducing the occasions where the adolescents could consume alcohol as they perhaps usually would.

Acute or recent infections may also affect lymphocytes. The blood samples were collected at schools and participants attending school were assumed to be free of illness. No additional information on infections was obtained on the day of blood collection and serologic testing for viruses to rule out the observation of lymphopaenia was not deemed feasible. However, all participantss included in the parent study underwent a complete physical examination by a clinician on the day of screening to rule out severe illness/infection.

Our findings are in line with research in human adult alcoholics and animal models, which have also found decreases in circulating T-lymphocyte numbers (Cook et al., 1995; Kutscher et al., 2002; Zhang and Meadows, 2005). Although the peripheral blood compartment does not reflect the total lymphocyte pool, the fact that other blood elements have been shown to decrease could imply that the bone marrow hematopoeisis process may be affected.

Schleifer and colleagues (1999), however, did not find such differences in alcohol-dependant adults without medical disorders compared to non-abusing controls. Follow-on work by Schleifer and colleagues (2002), which included alcohol-dependent adults with minor health abnormalities, also found no differences in CD8+ and other immune measures. Further research to clarify the effect of heavy alcohol use during adolescence on immunity is lacking and this study, although preliminary, contributes some insight into possible effects.

The higher, although not significantly so, ratios of CD4+ to CD8+ T-lymphocytes in AD vs. controls is in line with previous work in chronic alcoholics in which normal or elevated ratios have been documented (Cook, 1998). We did not significant find differences between groups in NK cell activity. NK cells have been reported to display reduced functional activity in alcoholics, especially in individuals with liver or other alcohol-related diseases (Cook, 1998).

Previous research that examined peripheral blood lymphocytes in smokers and non-smokers showed that active smoking increases most immune cell numbers, including total lymphocytes, total T-cells, helper and suppressor T-cells, B-cells, and monocytes (Wolfe et al., 1993). Although more AD participants than controls smoked cigarettes, all were light smokers. There was some experimentation with cannabis in both groups but cannabis doses were very low and none of our participants reported ever using any other type of illicit drug.

The limitations of this study include the small sample size and also the lack of measurement of antigen-specific T-lymphocyte responses. The aim of this work was to explore possible differences between control and pure AD adolescents with regard to circulating T cells. We did not conduct functional assays such as mitogen-induced cell proliferation or antigen-specific responses to determine response potential to offending antigens. Given this preliminary data, indicating alcohol-related effects on lymphocyte numbers, it is reasonable to speculate that this sample may also show reduced cellular responses in vivo. Future work could consider stimuli derived from recall bacterial/yeasts (Candida) or Tetanus toxoid to determine these responses, either by measuring proliferation or by the secretion of important immune regulatory cytokines.

In conclusion, developmentally vulnerable adolescents who consume excessive amounts of alcohol in a weekend binge drinking style may be at increased risk of lymphopenia, more specifically in relation to circulating absolute CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ T-lymphocyte numbers. This reduction may impact immune capabilities and if these effects are perpetuated throughout adolescent development, ongoing alcohol misuse may increase susceptibility to a range of infectious diseases and may also impact acute phase responses to ongoing stressors, including exposure to infective pathogens. This possible reduction in cellular immune capacity is particularly concerning in light of the endemic rates of infectious diseases, including TB and HIV, in South Africa. The complex interaction of alcohol use with other high risk activities such as unprotected sex and, in older adolescents with higher rates of co-morbid substance misuse, further compounds the potential risks suggested by our data. Because of the small sample sizes reported here, findings should be interpreted with caution. However, within this research field where data is limited, these results provide an initial indication of possible effects of heavy alcohol use during adolescence on cellular immunity. In Africa HIV transmission is higher than in Europe and the US (Miller and Shattock, 2003) and some of this difference in transmission efficiency is attributable to host factors (Miller and Shattock, 2003). Factors common to developing settings, such as poor nutrition and recurrent infections, like helminths and sexually transmitted diseases, are known to negatively affect immune function and may increase HIV susceptibility (Chersich and Rees, 2008; Miller et al., 1993; Schaible and Kaufmann, 2007). We can reasonably hypothesize that the decreased lymphocyte counts are an observation that may be linked to heavy alcohol use. Therefore, within this context, these adolescents may be more susceptible to HIV and other infections due to both risky behavior and decreased immune capabilities, as a result of reduced levels of available effector cells able to combat and prevent infection.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by 5R01AA016303 (PI: Fein).

The authors would like to express gratitude to Ms. Patsy Thomson for data entry, Ms Jonica Hall for data synthesis, Ms. Barenise Alexander for participant recruitment, and schools and participants from the Western Cape Education Department for their cooperation and participation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

There are no conflicts of interest, past or present.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - Fourth Revision. Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Brown LA, Cook RT, Jerrells TR, Kolls JK, Nagy LE, Szabo G, Wands JR, Kovacs EJ. Acute and chronic alcohol abuse modulate immunity. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2006;30:1624–1631. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Tapert SF, Granholm E, Delis DC. Neurocognitive functioning of adolescents: effects of protracted alcohol use. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2000;24:164–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucholz KK, Cadoret R, Cloninger CR, Dinwiddie SH, Hesselbrock VM, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Reich T, Schmidt I, Schuckit MA. A new, semi-structured psychiatric interview for use in genetic linkage studies: a report on the reliability of the SSAGA. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1994;55:149–158. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charpentier B, Franco D, Paci L, Charra M, Martin B, Vuitton D, Fries D. Deficient natural killer cell activity in alcoholic cirrhosis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1984;58:107–115. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chersich MF, Rees HV. Vulnerability of women in southern Africa to infection with HIV: biological determinants and priority health sector interventions. AIDS. 2008;22 Suppl 4:S27–S40. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000341775.94123.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook RT. Alcohol abuse, alcoholism, and damage to the immune system--a review. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1998;22:1927–1942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook RT, Ballas ZK, Waldschmidt TJ, Vandersteen D, LaBrecque DR, Cook BL. Modulation of T-cell adhesion markers, and the CD45R and CD57 antigens in human alcoholics. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1995;19:555–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook RT, Li F, Vandersteen D, Ballas ZK, Cook BL, LaBrecque DR. Ethanol and natural killer cells. I. Activity and immunophenotype in alcoholic humans. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1997;21:974–980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook RT, Waldschmidt TJ, Cook BL, Labrecque DR, McLatchie K. Loss of the CD5+ and CD45RAhi B cell subsets in alcoholics. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1996;103:304–310. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-621.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flisher AJ, Parry CD, Evans J, Muller M, Lombard C. Substance use by adolescents in Cape Town: prevalence and correlates. J. Adolesc. Health. 2003;32:58–65. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00445-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happel KI, Nelson S. Alcohol, immunosuppression, and the lung. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2005;2:428–432. doi: 10.1513/pats.200507-065JS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Ryan N. The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Aged Children (6–18 years) Lifetime Version. 1996 doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Lee S, Chow J, Lau J, Tsang A, Choi J, Griffiths SM. Prevalence and the factors associated with binge drinking, alcohol abuse, and alcohol dependence: a population-based study of Chinese adults in Hong Kong. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43:360–370. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Rehm J, Gmel G. Characteristics of binge drinkers in Europe. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004;59:113–127. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutscher S, Heise DJ, Banger M, Saller B, Michel MC, Gastpar M, Schedlowski M, Exton M. Concomitant endocrine and immune alterations during alcohol intoxication and acute withdrawal in alcohol-dependent subjects. Neuropsychobiology. 2002;45:144–149. doi: 10.1159/000054955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li TK. Quantifying the risk for alcohol-use and alcohol-attributable health disorders: present findings and future research needs. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008;23 Suppl 1:S2–S8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim WY, Fong CW, Chan JM, Heng D, Bhalla V, Chew SK. Trends in alcohol consumption in Singapore 1992 2004. Alcohol Alcohol. 2007;42:354–361. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor RR, Louria DB. Alcohol and infection. Curr. Clin. Top. Infect. Dis. 1997;17:291–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DB. Adolescence and alcohol: recent advances in understanding the impact of alcohol use during a critical developmental window. Alcohol. 2010;44:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2009.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle P. Alcohol abuse in adolescents. Arch. Dis. Child. 2008;93:524–527. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.115840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows GG, Blank SE, Duncan DD. Influence of ethanol consumption on natural killer cell activity in mice. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1989;13:476–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1989.tb00359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows GG, Wallendal M, Kosugi A, Wunderlich J, Singer DS. Ethanol induces marked changes in lymphocyte populations and natural killer cell activity in mice. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1992;16:474–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb01403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messingham KA, Faunce DE, Kovacs EJ. Alcohol, injury, and cellular immunity. Alcohol. 2002;28:137–149. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(02)00278-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CJ, McGhee JR, Gardner MB. Mucosal immunity, HIV transmission, and AIDS. Lab. Invest. 1993;68:129–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CJ, Shattock RJ. Target cells in vaginal HIV transmission. Microbes Infect. 2003;5:59–67. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(02)00056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss HB, Kirisci L, Gordon HW, Tarter RE. A neuropsychologic profile of adolescent alcoholics. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1994;18:159–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutchnick MG, Lee HH. Imparied lymphocyte proliferative response to mitogen in alcoholic patients. Absence of a relation to liver disease activity. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1988;12:155–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1988.tb00151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson S, Kolls JK. Alcohol, host defence and society. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002;2:205–209. doi: 10.1038/nri744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIAAA. National Advisory Council on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Summary of Meeting; 4–5 February, 2004.2004. [Google Scholar]

- Parry CD, Myers B, Morojele NK, Flisher AJ, Bhana A, Donson H, Pluddemann A. Trends in adolescent alcohol and other drug use: findings from three sentinel sites in South Africa (1997–2001) J. Adolesc. 2004;27:429–440. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy SP, Panday S, Swart D, Jinabhai CC, Amosun SL, James S, Monyeki KD, Stevens G, Morejele N, Kambaran NS, et al. Umthenthe Uhlaba Usamila – The South African Youth Risk Behaviour Survey 2002. Cape Town: South African Medical Research Council; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Roselle GA, Mendenhall CL, Grossman CJ, Weesner RE. Lymphocyte subset alterations in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. J. Clin. Lab. Immunol. 1988;26:169–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaible UE, Kaufmann SH. Malnutrition and infection: complex mechanisms and global impacts. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleifer SJ, Benton T, Keller SE, Dhaibar Y. Immune measures in alcohol-dependent persons with minor health abnormalities. Alcohol. 2002;26:35–41. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(01)00194-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleifer SJ, Keller SE, Shiflett S, Benton T, Eckholdt H. Immune changes in alcohol-dependent patients without medical disorders. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1999;23:1199–1206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shellito JE, Olariu R. Alcohol decreases T-lymphocyte migration into lung tissue in response to Pneumocystis carinii and depletes T-lymphocyte numbers in the spleens of mice. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1998;22:658–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb04308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MC. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Raye Z, Litten JPA, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biochemical methods. Totowa, NJ: Human Press, Inc; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Song K, Coleman RA, Zhu X, Alber C, Ballas ZK, Waldschmidt TJ, Cook RT. Chronic ethanol consumption by mice results in activated splenic T cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2002;72:1109–1116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS Inc. SPSS Statistics 17.0. Chicago: SPSS Inc.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Starkenburg S, Munroe ME, Waltenbaugh C. Early alteration in leukocyte populations and Th1/Th2 function in ethanol-consuming mice. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2001;25:1221–1230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo G. Consequences of alcohol consumption on host defence. Alcohol Alcohol. 1999;34:830–841. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/34.6.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo G, Mandrekar P. A recent perspective on alcohol, immunity, and host defense. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2009;33:220–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00842.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapert SF, Brown SA. Neuropsychological correlates of adolescent substance abuse: four-year outcomes. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 1999;5:481–493. doi: 10.1017/s1355617799566010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapert SF, Brown SA. Substance dependence, family history of alcohol dependence and neuropsychological functioning in adolescence. Addiction. 2000;95:1043–1053. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95710436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Applied Studies. National Survey on Drug Use and Health; 2005. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe WH, Miner JC, Michalek JE. Immunological parameters in current and former US Air Force personnel. Vaccine. 1993;11:545–547. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90228-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Meadows GG. Chronic alcohol consumption in mice increases the proportion of peripheral memory T cells by homeostatic proliferation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2005;78:1070–1080. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0605317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]