Abstract

Aversive symptoms of abstinence from nicotine have been posited to lead to smoking relapse and research on temporal patterns of abstinence symptoms confirms this assumption. However, little is known about the association of symptom trajectories early after quitting with post-cessation smoking or about the differential effects of tonic (background) versus phasic (temptation-related) symptom trajectories on smoking status. The current study examined trajectories of urge and negative mood among 300 women using the nicotine patch during the first post-cessation week. Ecological momentary assessments collected randomly and during temptation episodes were analyzed using hierarchical linear modeling yielding four individual trajectory parameters: intercept (initial symptom level), linear slope (direction and rate of change), quadratic coefficient (curvature), and volatility (scatter). Early lapsers, who lapsed during the first post-cessation week, exhibited more severe tonic urge and phasic negative mood immediately after quitting, and more volatile tonic and phasic urge compared to abstainers. Late lapsers, who were abstinent during the first week but lapsed by 1 month, exhibited more severe tonic urge immediately after quitting compared to abstainers. These results demonstrate the importance of early post-cessation urge and negative affect and highlight the value of examining both tonic and phasic effects of abstinence from nicotine.

Keywords: Early post-cessation symptoms, Withdrawal trajectory, Volatility, Urge, Negative Mood, Lapser, Ecological Momentary Assessment

Each year, over 40 % of current smokers in the U.S. attempt to quit, but only 5% of all smokers quit successfully (CDC, 2002, 2006). Thus, continued efforts to elucidate the specific mechanisms that lead to relapse are crucial for developing interventions that can improve quit rates. Relapse has often been posited to result from nicotine withdrawal, a syndrome that develops after cessation or reduction of tobacco use and that can cause clinically significant distress and impairment (DSM-IV-TR, 2000). Withdrawal is at the center of many conceptual models of drug use and relapse (e.g., Baker, Morse, & Sherman, 1987; Baker, Piper, McCarthy, Majeskie, & Fiore, 2004; Solomon, 1977) and is thought to mediate the effects of several existing treatments (e.g., Hughes, 1993; Piper et al., 2008).

Among symptoms of withdrawal, negative mood and urge/craving are common across all drugs of abuse (Baker et al., 1987; Baker et al., 2004; Solomon, 1977), with four out of eight formal symptoms of nicotine withdrawal pertaining to negative affect (DSM-IV-TR, 2000). Although not a formal criterion, urge/craving, defined as a strong subjective desire to smoke, is a reliable, valid, and clinically significant symptom (Abrams, 2000; Shiffman, 2000) that is commonly included in withdrawal scales (e.g., Hughes, 2007; Welsch et al., 1999).

Post-cessation symptoms emerge within 30 minutes of the last cigarette (Hendricks, Ditre, Drobes, & Brandon, 2006; Hughes, 1992) and up to 62% of smokers relapse within the first week or two following cessation (Garvey, Bliss, Hitchcock, Heinold, & Rosner, 1992), highlighting the importance of phenomena occurring early after quitting. For example, overall withdrawal and craving alone during the first post-cessation week predict relapse (Piper et al., 2008), as does an increase in craving on the quit day (McCarthy, Piasecki, Fiore, & Baker, 2006). Similarly, large increases in negative mood on the quit date predict relapse among smokers with a history of major depression (Kahler et al., 2002).

Temporal patterns of post-cessation symptoms have also been associated with relapse. Piasecki and colleagues (Piasecki, Fiore, & Baker, 1998; Piasecki et al., 2000) demonstrated that trajectory clusters characterized by a late increase or a plateau of overall withdrawal, negative affect, or urge over several weeks were associated with subsequent relapse. Likewise, cluster analysis of depressive symptom profiles revealed that profiles showing symptoms increasing over time were associated with significantly higher odds of relapse than typical profiles (Burgess et al., 2002).

Individual, rather than clustered, post-cessation symptom trajectories have also been examined. Each individual’s trajectory in these studies was characterized by an intercept representing elevation of symptoms, a linear slope representing the direction and rate of symptom change, a quadratic index (curvature) describing deceleration versus acceleration of symptom change, and a volatility index capturing symptom scatter around the predicted trajectory line. Higher intercepts, positive linear slopes and higher volatility of a combined withdrawal index predicted subsequent relapse (Piasecki, Jorenby, Smith, Fiore, & Baker, 2003b). All four parameters indicated more aversive profiles of withdrawal among those who lapsed compared to abstainers (Piasecki, Jorenby, Smith, Fiore, & Baker, 2003a). Intercepts, linear slopes and quadratic coefficients of affective symptom trajectories differentiated between quitters on nicotine patch and quitters on placebo patch, with the placebo patch group showing steeper decline from elevated early symptoms (Gilbert et al., 2009).

These studies used paper-and-pencil daily diaries or assessments on selected days. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) methodology, which enables investigation of smoking-related phenomena in real or near-real time in the smokers’ natural environment (Stone, Shiffman, Atienza, & Nebeling, 2007) may be even better suited for withdrawal trajectory research. EMA can capture symptom peaks and valleys that may be missed by daily diary or retrospective questionnaires, and it permits naturalistic observation of post-cessation symptoms long enough to model a trajectory while avoiding error and biases associated with retrospective recall (Hammersley, 1994; Stone et al., 2007).

Recent symptom trajectory studies using EMA via electronic devices and multiple assessments per day have confirmed the effects of trajectory parameters on relapse. The intercept and slope of total withdrawal and craving trajectories (Piper et al., 2008), as well as the pre-quit slope of negative affect and a change of urge levels on the quit date (McCarthy et al., 2006) predict later relapse, although the quadratic trend and volatility indices were not included in these studies.

A key advantage of EMA is that it enables the examination of both the phasic post-cessation symptoms that occur during episodes of temptation and background or tonic symptom levels assessed on random occasions (Shiffman, 2000, 2005). To the best of our knowledge, temporal patterns of post-cessation symptoms have not been examined during temptation episodes and random occasions separately. Differentiation between phasic and tonic symptoms is important because the two aspects may reflect different influences on the withdrawal process. Shiffman theorized that phasic symptoms reflect transient situational triggers while tonic symptoms reflect chronic nicotine deprivation (Shiffman, 2000, 2005). Thus, temporal characteristics of phasic versus tonic symptoms may be differentially related to post-cessation smoking.

Studies of the association of post-cessation symptom trajectories with relapse reported either how individual trajectory parameters predict subsequent relapse (McCarthy et al., 2006; Piasecki et al., 2003b; Piper et al., 2008), or how trajectories differentiate between groups differing in cessation success such as lapsers and abstainers (Piasecki et al., 2003a). In the latter study, the two groups differed on all four trajectory parameters, but the trajectories were modeled over a long period (for 8 weeks after quitting). Given the importance of early post-cessation symptoms and the fact that the large majority of smokers relapse relatively quickly, whether such differences emerge during the first post-cessation week also warrants investigation.

Study Purpose and Overview

The purpose of the current study was to examine the association of urge/craving and negative affect trajectories early in a quit attempt with smoking relapse. In this study, relapse is defined as non-abstinence determined at specified time points, based on any smoking (i.e., even a puff) during the period indicated in the point prevalence abstinence measure. A lapse refers to a specific incident of smoking at any time during the quit attempt.

Women enrolled in a smoking cessation randomized clinical trial provided EMA reports of their urge, negative mood, and lapse episodes for one week post-cessation. To address the issue of lapsing during or after this period, a 3-category lapser status was created including early lapsers who smoked during the first post-cessation week, late lapsers who abstained during the first post-cessation week but smoked by 1 month, and abstainers who were continuously abstinent from the quit day through 1 month. The groups were compared to one another with respect to the intercept, linear slope, quadratic coefficient, and volatility of symptom trajectories. We hypothesized that early lapsers would manifest the most severe initial symptoms, slower dissipating or worsening symptoms, and the highest symptom volatility, followed by late lapsers, and then abstainers. Because the study did not collect pre-quit EMA data, we cannot assert that the observed post-cessation urge and negative mood reflect withdrawal. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to focus on temporal trajectories of negative mood and urge/craving that used EMA data to construct trajectories, and that examined the effects of tonic and phasic post-cessation symptom trajectories separately.

Although staying abstinent after quitting is difficult for any smoker, there is evidence suggesting that it may be particularly difficult for women (Cepeda-Benito, Reynoso, & Erath, 2004; Wetter et al., 1999). Therefore, the parent study from which this analysis was derived (Wetter et al., in press) focused on the development of a relapse prevention intervention for women. Given that women may experience higher levels of abstinence-induced negative affect and urge to smoke compared to men (Leventhal et al., 2007; Wetter et al., 1999), studies of post-cessation symptom trajectories among women may help elucidate relapse mechanisms and lead to more effective treatments targeted at women.

Method

Parent Study

The current data come from a randomized clinical trial of a palmtop computer-delivered relapse prevention intervention for female smokers. Women who wanted to quit (N=302) completed baseline questionnaires, provided EMA data during the first post-cessation week, and were subsequently randomized to computer-delivered treatment or to a control group. The treatment did not affect abstinence (Wetter et al., in press). All participants received five group counseling sessions and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). Thus, the current study examined post-cessation symptoms not relieved by NRT or counseling.

Participants

Participants were recruited from the Seattle metropolitan area. Inclusion criteria were: female; age 18 to 70 years; smoking at least 10 cigarettes per day for at least the past year; expired breath carbon monoxide level ≥ 10 parts per million; and ability to speak, read, and write in English. Exclusion criteria were: regular use of tobacco products other than cigarettes; active substance abuse disorder; current psychiatric disorder; current bupropion use; and contraindications for NRT. Of the 302 participants, 300 provided EMA data and were included in the current analyses.

EMA Procedures and Measures

EMA data were collected using Casio E-10 palmtop computers with custom software, which precluded participants from using any other function of the computer. Participants were trained in how to use their computer and were asked to complete assessments for 1 week starting on the quit day. Study staff were available during the assessment week to answer questions and troubleshoot. Participants returned their computers at Day 7.

During the assessment week, participants completed “random assessments” in response to random computer prompts, “temptation assessments” each time they experienced an urge to smoke, “morning assessments” each day after waking, and “lapse assessments” each time they actually smoked a cigarette. The current study analyzed data collected during random assessments (RAs) and temptation assessments (TAs).

RAs

Each palmtop computer was programmed to deliver four prompts between the participant’s stated wake-up time and bedtime. To ensure that the prompts were spread throughout the participant’s waking hours, that time was divided into four equal segments with one random prompt scheduled within each segment. If a user-initiated assessment occurred within a 15-minute window prior to a scheduled random prompt, the prompt was rescheduled for another random time within the same time segment. Occasionally, if no time was left within the time segment, three instead of four RAs were delivered that day.

Each prompt was an alarm-style beeping tone delivered three times for 30 seconds with 30-second intervals of silence. The prompts were delivered for 2.5 minutes or until the participant responded. Participants had the option to delay RAs for 5 minutes up to 4 times. Assessments with no response were recorded as missing.

To encourage compliance with RAs, participants were compensated for their time and effort on the following schedule: 50 to 69% completed RAs - $10 gift certificate; 70 to 89% completed RAs - $25 gift certificate; and 90% or more completed RAs - $50 gift certificate. Feedback on RAs compliance rates was offered at Day 3 and Day 5, and percentages were computed on Day 7.

The EMA program delivered 7,409 random prompts during the assessment week. The prompts resulted in 5,764 completed RAs (78% compliance). Participants completed an average of 19.21 RAs during the week (SD = 5.10) and an average of 2.74 RAs per day (SD = 0.73).

TAs

Participants were asked to initiate and complete TAs every time they experienced an urge, desire, temptation or craving to smoke, or just felt like smoking. To avoid encouraging false reports of temptations, no incentives were offered for these user-initiated assessments.

Participants completed a total of 5,068 TAs, an average of 17.12 TAs per person for the week (SD = 11.21) and 2.45 TAs per day (SD = 1.60). Four participants did not provide any TAs.

EMA Items

The present study analyzed two EMA items that were administered both in RAs and TAs.

Urge

“How strong is your urge to smoke?” (1 - No Urge, 2 - Weak, 3 - Moderate, 4 - Strong, 5 - Severe).

Negative Mood

“Right now, my mood is negative (for example: irritable, sad, anxious, tense, stressed, angry, frustrated, etc).” (1- Definitely NO, 2 - Mostly NO, 3 - Mostly YES, 4 - Definitely YES).

In addition to negative mood and urge, RAs and TAs included measures not analyzed in the current study. Each EMA assessment typically required 2 to 4 minutes to complete.

Lapser Status and Abstinence Measures

Lapser status categories were created using Day 7 and 1 Month abstinence measures. Intent-to-treat, biochemically confirmed abstinence at Day 7 required a paper-and-pencil self-report of no smoking since quit day, no lapses recorded in the EMA data, and carbon monoxide (CO) levels of < 10 ppm at Days 3, 5, and 7. Intent-to-treat biochemically confirmed abstinence at 1 Month (Day 35) used paper-and-pencil self-report of no smoking “since our last contact” (“last contact” was at Day 7) and CO level of < 10 ppm. For Day 7 and 1 Month, missing self-reported smoking status or CO data were considered indicative of smoking. All participants attended the Day 7 (randomization day) visit and the follow-up rate at 1 Month was 95%.

Based on these measures, abstainers (n=132) were abstinent both at Day 7 and 1 Month (i.e., continuously from the quit day through 1 Month). Early lapsers (n= 75) smoked during the first post-cessation week, regardless of their smoking status at 1 Month. Late lapsers (n=93) were abstinent during the first post-cessation week, but smoked by 1 Month.

Among the 75 participants classified as early lapsers, 62 reported one or more lapses on their palmtops. The total number of EMA-reported lapses was 139 and 34 occurred on Day 1, 36 on Day 2, 13 on Day 3, 25 on Day 4, 11 on Day 5, 13 on Day 6, and 7 on Day 7. On average, early lapsers reported 2.24 lapses via EMA (SD = 2.43). Twenty five early lapsers reported more than one lapse per week via EMA, with 12 reporting 2 lapses, 2 reporting 3 lapses, 5 reporting 4 lapses, and 6 reporting 5, 7, 8, 9, 10 or 13 lapses per week, respectively.

Statistical Analyses

Hierarchical linear modeling of urge and negative mood

The EMA urge and negative mood data are hierarchically structured because the repeated measurements are nested within individuals. Hierarchical linear modeling (HLM1; Bryk & Raudenbush, 2002), in which the coefficients of the variables in the model that differ between individuals are treated as random effects, while the coefficients that are the same across individuals are treated as fixed effects, accounts for the within-subject correlation that arises from the heterogeneity of the study population. It also allows modeling autocorrelation that depends on time separation of measurements within each individual (Diggle, Heagerty, Liang, & Zeger, 2002) and dramatically improves power and efficiency in assessing the primary effects of interest when compared to the approach of treating subject-specific effects as fixed effects (Twisk, 2006). Under appropriate assumptions, valid inferences can be drawn in HLM by using all observed data even when some data are missing (Laird, 1988).

In our study, the HLM contained two levels of regression. At Level 1, the repeated measurement of urge or negative mood was expressed as a regression function of time for each individual. Therefore, the Level 1 models describe a single individual’s trajectory. The Level 2 models aimed to explain the differences of the Level 1 individual profiles as a function of other covariates (e.g., lapser status).

Individual-level profile (Level 1)

In Level 1 equations, time was coded as days from quitting, with fractional values allowed. To accommodate a potential nonlinear relationship between the symptoms and time, both linear (time) and quadratic (time squared) terms were included.

The above models resulted in three parameters. (1) The intercept represents each individual’s symptom level at the beginning of the trajectory (time zero) extrapolated from subsequent observations. Time zero refers to the beginning of the assessment week occurring on the quit day at the participant’s stated wake-up time. (2) The linear slope describes the direction (increase versus decrease) and rate of change of urge and negative mood over the assessment week.2 (3) The quadratic coefficient represents acceleration or deceleration of urge and negative mood over the course of one week. A positive quadratic coefficient indicates a concave profile while a negative coefficient indicates a convex profile. The analyses employed a model that allowed the autocorrelation to decay with time separation and that did not assume equal temporal spacing of the measurements.

Comparison between categories of lapser status (Level 2)

At Level 1, each individual’s symptom profile was modeled using the above-described equation that included both time and time-squared plus random error. At Level 2, lapser status was entered as a categorical predictor with three levels: early lapser, late lapser, and abstainer. Also included and tested were the interactions between lapser status and time as well as lapser status and time-squared. The former corresponded to the differences between lapser status categories with regards to the linear slope while the latter corresponded to the differences between lapser status categories with regard to curvature. Other covariates are listed below in the analytical plan section.

Effect sizes

Effect sizes were defined as the proportion of variance in the outcome variable explained by predictors of interest (Xu, 2003) and were calculated using an estimate proposed by Xu (Xu, 2003) for linear mixed-effects models. The estimate was modified to fall in the interval [0,1], which is congruent with its definition as a measure of the proportion of variance explained. Interpretation of sizes of the effects (i.e., across-group differences in the intercepts, linear slope and quadratic coefficients) is similar to a traditional partial correlation due to the analogy of our R2 estimate to the R2 measure from the linear regression model setting (Rutledge & Loh, 2004). Effect sizes < 4% are considered to be small, 4-9% to be mild, 9-25% to be moderate, and higher than 25% to be large (Neter, Kutner, Nachtsheim, & Wasserman, 1996).

Volatility of symptoms

Among the different ways to measure volatility (Hedeker, Mermelstein, & Demirtas, 2008; Jahng, Wood, & Trull, 2008; Piasecki et al., 2003a) lability of symptoms around the predicted trajectory was selected as best reflecting unpredictability of symptoms using one index to describe between- and within-subject differences. Specifically, the volatility index was defined as the mean absolute deviation (MAD) over time between a participant’s observed symptom scores and her HLM-predicted trajectory function. MAD was calculated along the entire trajectory and was due to both within- and between-day variation. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to test for differences in the volatility index across lapser status groups while adjusting for mean symptom levels.

Analytical plan

Urge and negative mood trajectories were analyzed separately within RAs and TAs using HLM. Basic models controlled for treatment3 only and adjusted models controlled for treatment, assessment time relative to the first lapse (before versus after), and baseline demographics and tobacco-related variables listed in Table 1. Effect sizes were calculated using the approach described above. Next, ANCOVA volatility tests were conducted. Finally, the average estimated trajectories by lapser status were plotted for adjusted models.

Table 1. Demographic and Baseline Tobacco-Related Characteristics in the Full Sample and by Lapser Status Groups.

| Variable | Total n = 300 |

Abstainers n = 132 |

Late Lapsers n = 93 |

Early Lapsers n = 75 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Quit Day | 42.8 (10.8) | 43.6 (10.4) | 42.0 (11.6) | 43.1 (11.0) |

| Race (% White) | 81.7 | 84.1* | 87.1@ | 70.7* @ |

| Education (% > High School) | 83.7 | 85.6 | 82.8 | 81.3 |

| Number of Cigarettes/Day | 20.5 (7.8) | 19.2 (7.2)* | 21.7 (8.3)* | 21.3 (7.8) |

| Carbon Monoxide Level | 23.2 (11.0) | 22.3 (10.7) | 24.2 (11.7) | 23.6 (10.6) |

| Fagerstrom Nicotine Dependence1 | 5.2 (1.9) | 4.9 (1.9) | 5.3 ( 2.0) | 5.3 (1.8) |

| Time to 1st Cigarette (% > 5 Min) | 63.7 | 68.9 | 57.0 | 62.7 |

| WSWS2 Mean Withdrawal Pre- cessation |

1.7 (0.6) | 1.6 ( 0.6) | 1.6 (0.6)* | 1.8 (0.5)* |

| History of Major Depression | 30.7 | 26.5 | 29.0 | 40.0 |

| CES-D3 Depression Symptoms | 7.2 (5.4) | 6.3 (5.2)* | 7.4 (5.1) | 8.5 (5.5)* |

| Treatment Group | 50.3 | 52.3 | 51.6 | 45.3 |

Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence, Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerstrom, 1991.

Wisconsin Smoking Withdrawal Scale, Welsch et al., 1999.

Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale, Radloff, 1977.

p<=.05. Pairwise differences between lapser status categories were tested using t-test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables.

p<=.05. Pairwise differences between lapser status categories were tested using t-test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables.

To support interpretation of the main analyses described above, supplemental analyses were conducted testing (1) associations of baseline variables with trajectory parameters and volatility of basic models using Pearson correlations for continuous variables and t-tests for categorical variables; (2) differences between linear slopes, quadratic coefficients4, and volatility indices before and after the first lapse among early lapsers using HLM (linear and quadratic coefficients) and Wilcoxon signed rank pairs test (volatility); (3) group differences in the number of temptations per week using Wilcoxon test; (4) associations between the number of temptations per week and trajectory parameters of basic models using Pearson correlation estimates and ANOVA; and (5) group differences in trajectories of daily temptation frequency using HLM.

All analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 for Windows (Copyright © 2002-2003 by SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The main analyses were conducted using PROC MIXED and PROC GLM. An alpha level of .05 was used in all analyses.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Baseline demographic and tobacco-related characteristics of study participants, and significant between-group differences are presented in Table 1. Additionally, dependence-related variables (number of cigarettes per day, baseline carbon monoxide, Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence and minutes to first cigarette) were significantly associated with symptom intercepts in all basic models - the higher the dependence, the higher the intercept. Higher baseline mean withdrawal was significantly associated with a higher intercept, less steep linear slope, deeper downward concave curvature in all basic models and with higher volatility in three out of four models. Older age was associated with lower volatility in basic and adjusted models.

Comparing Urge Trajectories among Lapser Status Groups

Urge during RAs

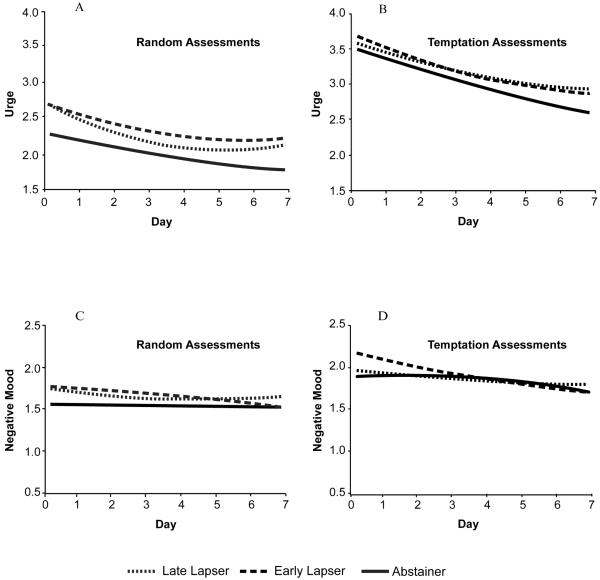

Results of basic and adjusted models of urge trajectories during RAs are summarized in Table 2 and adjusted models are depicted in Figure 1, Panel A. Abstainers had a significant downward slope and no quadratic trend in either model. In both models, early and late lapsers had significantly higher urge intercepts compared to abstainers (R2 = 24.0%, basic model, and 20.1%, adjusted model). The quadratic term increment for late lapsers versus abstainers was significant in both models (R2 = 0.04%) indicating a shallow concave trajectory shown in Figure 1, Panel A. The linear slope increment was significant in the adjusted model (R2 = 2.1%) but it did not have a straightforward interpretation in the presence of a significant quadratic term.

Table 2. Urge Trajectories during Random and Temptation Assessments in Late Lapsers, Early Lapsers, and Abstainers.

| Fixed Effect | Estimate | P | Estimate | P | Estimate | P | Estimate | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Assessments | Temptation Assessments | |||||||

| Basic Model | Adjusted Model | Basic Model | Adjusted Model | |||||

| Intercept | 2.22 | < .01 | 1.15 | < .01 | 3.40 | < .01 | 2.89 | < .01 |

| Late Lapser Increment | 0.40 | 0.01 | 0.39 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.48 |

| Early Lapser Increment | 0.49 | < .01 | 0.39 | 0.01 | 0.28 | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.17 |

| Linear Slope | −0.11 | 0.02 | −0.11 | 0.01 | −0.17 | < .01 | −0.16 | < .01 |

| Late Lapser Slope Increment | −0.13 | 0.06 | −0.14 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.89 | −0.01 | 0.85 |

| Early Lapser Slope Increment | −0.08 | 0.30 | −0.08 | 0.32 | −0.07 | 0.42 | −0.02 | 0.78 |

| Quadratic | 0.00 | 0.43 | 0.01 | 0.35 | 0.01 | 0.41 | 0.00 | 0.51 |

| Late Lapser Quadratic Increment | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.59 | 0.01 | 0.53 |

| Early Lapser Quadratic Increment | 0.01 | 0.28 | 0.01 | 0.28 | 0.01 | 0.32 | 0.01 | 0.43 |

| Late vs. Early Lapser Comparisons | Estimate | P | Estimate | P | Estimate | P | Estimate | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Late Lapser Intercept Increment | −0.09 | 0.61 | 0.00 | 0.99 | −0.13 | 0.37 | −0.09 | 0.51 |

| Late Lapser Slope Increment | −0.05 | 0.51 | −0.06 | 0.47 | 0.06 | 0.53 | 0.01 | 0.92 |

| Late Lapser Quadratic Increment | 0.01 | 0.52 | 0.01 | 0.50 | −0.01 | 0.65 | 0.00 | 0.85 |

Note. Intercept, linear slope, and quadratic term are estimates among abstainers. Late lapser and early lapser increments refer to the portion of the estimate above or below the abstainer estimate. For late versus early lapser comparisons, the late lapser increment is the portion of estimate above or below the early lapser estimate. The intercept estimate is defined as the average urge level for abstainers at time 0, using the unit of response scale 1 (no urge) through 5 (severe). The linear slope estimate for abstainers shows increase or decrease of the symptom in the unit of urge response scale per day. The estimate of the quadratic coefficient for abstainers describes symptom acceleration or deceleration in the units of the urge scale per day. Analyses controlled for treatment in basic models and treatment, baseline demographics, baseline tobacco-related variables and time of observation relative to the first lapse in adjusted models.

Figure 1.

Urge and negative mood trajectories among early lapsers, late lapsers, and abstainers measured during random and temptation assessments.

Urge during TAs

Across time and lapser status groups, urge ratings were significantly higher during TAs than during RAs (M = 3.19, SD = 1.13 versus M = 2.11, SD = 1.14; F = 2387, p<0.0001). Urge trajectories during TAs are summarized in Table 2 (basic and adjusted models) and Figure 1, Panel B (adjusted model). In both models, abstainers had a downward slope over time, but did not display a significant quadratic effect. Early lapsers had significantly higher initial urge levels than abstainers in the basic model (R2 = 4.4%), but this difference was no longer significant in the adjusted model.

Comparing Negative Mood Trajectories among Lapser Status Groups

Negative mood during RAs

Negative mood trajectories during RAs are presented in Table 3 (basic and adjusted models) and Figure 1, Panel C (adjusted model). Abstainers displayed no significant linear or quadratic trend over time. Early lapsers had significantly higher initial negative mood levels than abstainers in the basic model (R2 = 5.5%), but the intercept difference was no longer significant in the adjusted model.

Table 3. Negative Mood Trajectories during Random and Temptation Assessments in Late Lapsers, Early Lapsers, and Abstainers.

| Fixed Effect | Estimate | P | Estimate | P | Estimate | P | Estimate | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Assessments | Temptation Assessments | |||||||

| Basic Model | Adjusted Model | Basic Model | Adjusted Model | |||||

| Intercept | 1.57 | < .01 | 0.86 | < .01 | 1.93 | < .01 | 1.26 | .0001 |

| Late Lapser Increment | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.52 | 0.07 | 0.55 |

| Early Lapser Increment | 0.25 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.33 | 0.02 | 0.27 | 0.04 |

| Linear Slope | 0.00 | 0.95 | −0.01 | 0.82 | 0.01 | 0.87 | 0.02 | 0.69 |

| Late Lapser Slope Increment | −0.05 | 0.40 | −0.05 | 0.40 | −0.05 | 0.46 | −0.06 | 0.39 |

| Early Lapser Slope Increment | −0.01 | 0.89 | −0.01 | 0.93 | −0.11 | 0.17 | −0.10 | 0.20 |

| Quadratic | 0.00 | 0.91 | 0.00 | 0.96 | −0.01 | 0.43 | −0.01 | 0.30 |

| Late Lapser Quadratic Increment | 0.01 | 0.46 | 0.01 | 0.47 | 0.01 | 0.47 | 0.01 | 0.37 |

| Early Lapser Quadratic Increment | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.01 | 0.38 | 0.01 | 0.37 |

| Late vs. Early Lapser Comparisons | Estimate | P | Estimate | P | Estimate | P | Estimate | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Late Lapser Intercept Increment | −0.07 | 0.54 | −0.02 | 0.90 | −0.25 | 0.09 | −0.20 | 0.17 |

| Late Lapser Slope Increment | −0.04 | 0.55 | −0.04 | 0.53 | 0.05 | 0.54 | 0.04 | 0.65 |

| Late Lapser Quadratic Increment | 0.01 | 0.30 | 0.01 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 0.85 | 0.00 | 0.94 |

Note. Intercept, linear slope, and quadratic term are estimates among abstainers. Late lapser and early lapser increments refer to the portion of the estimate above or below the abstainer estimate. For late versus early lapser comparisons, the late lapser increment is the portion of estimate above or below the early lapser estimate. The intercept estimate is defined as the average negative mood level for abstainers at time 0, using the unit of negative mood response scale 1 (definitely no) through 4 (definitely yes). The linear slope estimate for abstainers shows increase or decrease of the symptom in the unit of negative mood response scale per day. The estimate of the quadratic coefficient for abstainers describes symptom acceleration or deceleration in the units of the negative mood scale per day. Analyses controlled for treatment in basic models and treatment, baseline demographics, baseline tobacco-related variables and time of observation relative to the first lapse in adjusted models.

Negative mood during TAs

Across time and lapser status groups, negative mood ratings were significantly higher during TAs compared to RAs (M = 2.02, SD = 0.93 versus M = 1.68, SD = 0.81; F = 414, p < 0.0001). The negative mood trajectories during TAs are summarized in Table 3 (basic and adjusted models) and Figure 1, Panel D (adjusted model). Abstainers did not show a significant linear or quadratic effect over time. Early lapsers had a significantly higher negative mood intercept compared to abstainers in the basic model (R2 = 6.5%) and in the adjusted model (R2 = 4.8%).

Volatility

In the entire sample, volatility was significantly higher during TAs compared to RAs both for urge (M = 0.67, SD = 0.25 versus M = 0.59, SD = 0.24, p < 0.0001; adjusted models) and negative mood (M = 0.56, SD = 0.24 versus M = 0.43, SD = 0.20, p < 0.0001; adjusted models). Urge volatility during RAs and TAs was significantly higher among early lapsers compared to abstainers in basic and adjusted models (Table 4). Negative mood volatility during TAs was significantly higher among early lapsers compared to late lapsers in the basic model, but this difference was no longer significant in the adjusted model ((Table 4).

Table 4. Volatility of Urge and Negative Mood around the Predicted Trajectory: Comparison of Early Lapsers, Late Lapsers, and Abstainers.

| Abstainers (A) |

Late Lapsers (LL) |

Early Lapsers (EL) |

EL v. A | LL v. A | EL v. LL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | P | T | P | T | P | ||||

| BASIC MODELS | |||||||||

| Urge - Random Assessments | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.56 (0.23) | 0.59 (0.23) | 0.64 (0.23) | 2.30 | 0.02 | 0.96 | 0.34 | 1.34 | 0.18 |

| 95% CI | 0.52 - 0.60 | 0.54 - 0.64 | 0.58 - 0.69 | ||||||

| Urge - Temptation Assessments | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.63 (0.25) | 0.68 (0.25) | 0.74 (0.25) | 2.78 | 0.01 | 1.24 | 0.21 | 1.50 | 0.13 |

| 95% CI | 0.59 - 0.68 | 0.63 - 0.73 | 0.68 - 0.79 | ||||||

| Negative Mood - Random Assessments | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.43 (0.18) | 0.41 (0.18) | 0.46 (0.18) | 0.99 | 0.32 | −0.84 | 0.40 | 1.67 | 0.10 |

| 95% CI | 0.40 - 0.46 | 0.38 - 0.45 | 0.42 - 0.50 | ||||||

| Negative Mood - Temptation Assessments | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.57 (0.23) | 0.52 (0.23) | 0.60 (0.23) | 0.78 | 0.44 | −1.58 | 0.12 | 2.09 | 0.04 |

| 95% CI | 0.53 - 0.61 | 0.47 - 0.57 | 0.54 - 0.65 | ||||||

| A | LL | EL | EL v. A | LL v. A | EL v. LL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | P | T | P | T | P | ||||

| ADJUSTED MODELS | |||||||||

| Urge - Random Assessments | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.56 (0.23) | 0.59 (0.23) | 0.64 (0.23) | 2.28 | 0.02 | 1.00 | 0.32 | 1.28 | 0.20 |

| 95% CI | 0.52 - 0.60 | 0.54 - 0.64 | 0.58 - 0.69 | ||||||

| Urge - Temptation Assessments | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.63 (0.25) | 0.68 (0.25) | 0.73 (0.25) | 2.53 | 0.01 | 1.31 | 0.19 | 1.22 | 0.22 |

| 95% CI | 0.59 - 0.68 | 0.63 - 0.73 | 0.67 - 0.78 | ||||||

| Negative Mood - Random Assessments | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.43 (0.18) | 0.42 (0.18) | 0.46 (0.18) | 0.96 | 0.34 | −0.78 | 0.44 | 1.59 | 0.11 |

| 95% CI | 0.40 - 0.47 | 0.38 - 0.45 | 0.42 - 0.50 | ||||||

| Negative Mood - Temptation Assessments | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.57 (0.23) | 0.52 (0.23) | 0.59 (0.23) | 0.46 | 0.65 | −1.56 | 0.12 | 1.79 | 0.07 |

| 95% CI | 0.53 - 0.61 | 0.47 - 0.57 | 0.53 - 0.64 | ||||||

Note. Volatility index was computed as mean absolute deviation. Differences between lapser status categories were tested using ANCOVA adjusting for mean symptom (urge or negative mood) level.

Trajectories and Volatility Among Early Lapsers Before and After Initial Lapse

Linear slopes and quadratic coefficients of urge and negative mood trajectories among early lapsers did not significantly differ before and after the first lapse across basic and adjusted RAs and TAs models. Similarly, comparisons of volatility of urge and negative mood before and after the first lapse did not reveal any significant differences.

Temptation Frequency

Lapser status groups did not differ with respect to the number of reported temptations. Number of temptations per week was not associated with trajectory parameters and these associations did not differ by lapser status. Trajectories of daily temptation frequency across the post-cessation week did not differ by lapser status on any of the parameters.

Discussion

The current study demonstrated that female smokers who lapsed relatively quickly during a quit attempt experienced more severe post-cessation symptoms when compared to abstainers. Specifically, they exhibited higher initial levels of background urge, higher initial levels of negative affect during episodes of temptation, and more pronounced volatility of urge. Women who smoked later generally fell between early lapsers and abstainers in symptom severity, and differed from the latter in initial background urge, but not negative mood or volatility.

These intercept and volatility results are consistent with expectations, but the current study did not find the hypothesized differences between lapser status groups in the linear slope and the curvature representing the rate of symptom change over time. Women who smoked early did not show the expected signs of slower dissipating or worsening symptoms. A shallow concave trajectory of background urge was found only among late lapsers and did not appear clinically significant given the small effect size. On the other hand, effect sizes for significant intercepts ranged from mild to moderate, typical of behavioral predictors, which rarely produce large effects (Rutledge & Loh, 2004). Controlling for baseline characteristics eliminated three out of nine significant between-group differences demonstrating that the remaining differences are explained by post-cessation smoking, above and beyond variability explained by baseline characteristics.

Comparisons of the current results with previous studies are challenging given different trajectory monitoring periods, different measures of post-cessation symptoms, and mixed gender samples in those studies. With these caveats in mind, our intercept and volatility results were generally congruent with those from previous research, including the paper diary study comparing trajectories of withdrawal between lapsers and abstainers (Piasecki et al., 2003a, 2003b). The lack of consistent significant effects of symptom change over time found in other studies (Burgess et al., 2002; Piasecki et al., 1998; Piasecki et al., 2003a, 2003b; Piasecki et al., 2000) might be attributed to a short monitoring period in our investigation. The current results differed from those in two other EMA studies which did not find any differences in post-cessation urge or negative mood between lapser status groups (Shiffman et al., 1997; Shiffman et al., 1996). However, Shiffman and colleagues used different analytic methods from those employed in the current study, so it is difficult to evaluate the reasons for these differential findings.

An important point of emphasis is that the observed intercept differences between lapser status categories represented their symptom levels at the beginning of post-quit Day 1. This finding is consistent with research showing that withdrawal emerges very quickly after quitting and that the immediate response to nicotine deprivation may be useful in determining the risk for relapse (Hendricks et al., 2006; Kahler et al., 2002; McCarthy et al., 2006).

While the intercept is a static parameter of the trajectory, another notable finding reflected the dynamic aspect of symptoms showing that women who lapsed during the first post-cessation week exhibited the greatest volatility of urge. Although volatility has been associated with post-cessation smoking in previous studies (Piasecki et al., 2003a, 2003b), to our knowledge, our study is the first to demonstrate that volatility of urge early in the process of quitting is associated with relapse.

There may be different mechanisms underlying the relationship of urge volatility and relapse. One relevant factor is that volatility captures peak values. Importantly, it also captures fluctuations, including acute symptom increases that may be unexpected and catch the quitter off guard before she can perform coping behaviors. Moreover, based on the strength model of self-regulation (Muraven & Baumeister, 2000; Muraven & Shmueli, 2006), where self-control is viewed as a limited resource, exertion associated with attempts to control volatility in urges may lead to fatigue, depletion of coping resources, and ultimately relapse. A recent EMA study of post-cessation urges (O’Connell, Schwartz, & Shiffman, 2008) did not support the strength model with respect to the number and duration of urges, but the intensity of the most recent resisted urge predicted smoking in one of the two analyzed samples. The few studies to date that used the volatility index derived it from one measurement per day (Piasecki et al., 2003a, 2003b). Our results, based on several EMA assessments per day, confirm the usefulness of incorporating volatility as a component of post-cessation symptom profiles in future studies.

Current results related to volatility show that women who lapse early display the highest volatility measures both within the tonic (background) and phasic (temptation-related) urge. On the other hand, the findings related to initial symptom severity discriminate between tonic and phasic symptoms. Theoretically, tonic symptoms are slowly changing conditions resulting from nicotine deprivation, and phasic symptoms are acute, superimposed on the background level, and set off by situational triggers such as a stressful event or a smoking cue (Shiffman, 2000, 2005). The possibility of different mechanisms implies that tonic and phasic symptoms may be differentially associated with relapse, as suggested by our results.

Although our study did not test for an interaction between assessment type (RAs versus TAs) and lapser status, the finding of higher initial urge severity among early and late lapsers compared to abstainers during RAs but not TAs suggests that urge levels during temptations may be similar for all smokers while background urge levels may differ between those who relapse and those who remain abstinent. This interpretation is similar to findings from studies of ad libitum smokers showing that tonic but not phasic urge differentiated between more and less dependent smokers (e.g., Shiffman & Paty, 2006). Conversely, severity of negative mood in our study differentiated between early lapsers and abstainers during TAs but not RAs suggesting that phasic negative affect may play a more important role in post-cessation smoking than background negative affect. Future research may consider including situational triggers to further probe the differential association of tonic and phasic trajectory parameters with relapse.

The present findings have several treatment implications. Initial high severity of urge and negative affect experienced by early lapsers might respond to pre-cessation measures. Pre-cessation counseling, focused on developing a very specific plan for the quit day, might help to address high symptom levels experienced immediately after quitting. Scheduled reduced smoking might be considered, because it is more effective in alleviating post-cessation withdrawal than abrupt cessation (Cinciripini et al., 1995). Starting the nicotine patch pre-cessation could potentially lower post-cessation symptom levels, because it has proven to be more effective than the patch starting at quit day (Shiffman & Ferguson, 2008). Other pharmacotherapies that begin pre-cessation such as varenicline and bupropion might also have beneficial effects on reducing symptom levels on the quit day. However, these steady-state pharmacotherapies have been proven to affect tonic craving while evidence does not confirm their effectiveness in reducing episodic craving (Perkins, 2009; Piasecki, Jorenby, Smith, Fiore, & Baker, 2003c). Therefore, urge increases among early lapsers reflected by high volatility of both phasic and tonic craving could potentially be treated with ad libitum NRT (gum, spray, inhaler or lozenge) added to the patch, bupropion, or varenicline. Evidence shows that a combination of medications in all likelihood suppresses craving more effectively than a single medication (Fiore et al., 2008), possibly via a synergistic effect of a steady-state medication reducing tonic craving and an acute NRT medication reducing episodic craving (Ferguson & Shiffman, 2009).

Limitations

The study has several limitations. First, the lack of pre-cessation EMA data does not allow to preclude that the observed high post-cessation symptoms were due to pre-existing high levels of the same symptoms rather than to withdrawal, although some of the baseline covariates that were controlled included information about urge and negative affect.

Second, the results, although prospective, are nevertheless correlational and may reflect the effects of a factor not measured in this study, so inferences about causality should be drawn with caution. Such inferences are particularly challenging among early lapsers whose post-cessation symptoms may have been potentially confounded by smoking. For example, symptom increases proximal to lapses could have affected trajectories and volatility of early lapsers but not late lapsers or abstainers such that interpretation of post-cessation symptom profiles as predisposing to relapse in all three groups should be avoided. However, supplemental analyses among early lapsers did not confirm the confounding effects of smoking and the possibility of such effects in the analyses across the three groups was reduced by controlling for observation time relative to the initial lapse.

Third, challenges related to TAs need to be borne in mind. Although the numbers of reported temptations are consistent with other studies (e.g., (Shiffman et al., 1996), temptations may have been under-reported given that incentives could not be used. The fact that negative mood but not urge discriminated between lapser status groups during temptations may possibly reflect uniformity imposed on urge ratings by TAs instructions requiring high levels of urge, while no such limits were imposed on negative mood ratings. Additionally, group differences observed during temptations may potentially reflect phenomena other than the phasic process such as differences in sensitivity to temptation or differences in the subjective criteria used to define a temptation. Therefore, interpretation of TAs as reflecting phasic phenomena necessitates caution. Potential differences in the frequency of experienced temptations were considered but temptation frequency did not emerge as a significant factor in post-cessation smoking differences in this study.

Fourth, given that NRT has been shown to reduce symptom elevation in two trajectory studies (Gilbert et al., 2009; Piasecki et al., 2003c), the patch may have dampened post-cessation symptoms and decreased sensitivity of our analysis. However, the majority of previous studies also used NRT (McCarthy et al., 2006; Piasecki et al., 1998; Piasecki et al., 2003a, 2003b; Piasecki et al., 2000; Piper et al., 2008). Considering that the use of NRT is now standard of care recommended by the Clinical Practice Guideline (Fiore et al., 2008), our results apply to an important segment of female quitters.

Finally, research on the association of gender with post-cessation symptom profiles is scarce and inconclusive (Gilbert et al., 2009; Piasecki et al., 2003c). Since only women were studied, the results cannot be generalized to men or to the general population.

Conclusions

With these limitations in mind, characteristics of urge and negative affect during the first week after quitting differentiated between more and less successful quitters in our study, illustrating the potential importance of early post-cessation symptoms with respect to influencing smoking relapse among women and pointing to the possibility of early intervention to prevent relapse. Our findings support the value of withdrawal research using EMA and encourage research of early post-cessation symptom dynamics among other populations with the ultimate goal of developing better, more sophisticated treatments.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grant R01CA74517 awarded by the National Cancer Institute to Dr. David Wetter

Footnotes

HLM denotes both hierarchical linear modeling and hierarchical linear model, assuming the associated context informs the term that is referred to.

Interpretation of the linear slope should be combined with the quadratic coefficient and the time point being assessed to describe the symptom rate of change at that time point.

Treatment was delivered after EMA data collection but could have affected between-group differences via post-treatment 1 Month abstinence used to construct lapser status groups.

Intercept difference were not tested because linear slope and quadratic term are sufficient to determine trajectory differences when the two trajectories are constrained to connect at the point of first lapse.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/abn

References

- Abrams DB. Transdisciplinary concepts and measures of craving: commentary and future directions. Addiction. 2000;95(Suppl 2):S237–246. doi: 10.1080/09652140050111807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Morse E, Sherman JE. The motivation to use drugs: A psychobiological analysis of urges. In: Rivers C, editor. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation. University of Nebraska Press; Lincoln: 1987. pp. 257–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: an affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review. 2004;111(1):33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Hierarchical linear models. 3rd ed. Sage; London: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess ES, Brown RA, Kahler CW, Niaura R, Abrams DB, Goldstein MG, et al. Patterns of change in depressive symptoms during smoking cessation: who’s at risk for relapse? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(2):356–361. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.70.2.356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC . Cigarette smoking among adults - United States, 2000, MMWR - Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. Vol. 51. 2002. pp. 642–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC . Tobacco use among adults --- United States, 2005, MMWR - Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. Vol. 55. 2006. pp. 1145–1148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda-Benito A, Reynoso JT, Erath S. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation: differences between men and women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(4):712–722. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinciripini PM, Lapitsky L, Seay S, Wallfisch A, Kitchens K, Van Vunakis H. The effects of smoking schedules on cessation outcome: can we improve on common methods of gradual and abrupt nicotine withdrawal? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63(3):388–399. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.3.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diggle PJ, Heagerty P, Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Analysis of longitudinal data. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- DSM-IV-TR . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4 ed. American Psychiatric Association; Arlington, VA: 2000. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SG, Shiffman S. The relevance and treatment of cue-induced cravings in tobacco dependence. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36(3):235–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz NL, Curry SJ, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service; Rockville, MD: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Garvey AJ, Bliss RE, Hitchcock JL, Heinold JW, Rosner B. Predictors of smoking relapse among self-quitters: a report from the Normative Aging Study. Addictive Behaviors. 1992;17(4):367–377. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90042-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DG, Zuo Y, Rabinovich NE, Riise H, Needham R, Huggenvik JI. Neurotransmission-related genetic polymorphisms, negative affectivity traits, and gender predict tobacco abstinence symptoms across 44 days with and without nicotine patch. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118(2):322–334. doi: 10.1037/a0015382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammersley R. A digest of memory phenomena for addiction research. Addiction. 1994;89(3):283–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb00890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D, Mermelstein RJ, Demirtas H. An application of a mixed-effects location scale model for analysis of Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) data. Biometrics. 2008;64(2):627–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2007.00924.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks PS, Ditre JW, Drobes DJ, Brandon TH. The early time course of smoking withdrawal effects. Psychopharmacology. 2006;187(3):385–396. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0429-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR. Tobacco withdrawal in self-quitters. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60(5):689–697. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.5.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR. Pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation: unvalidated assumptions, anomalies, and suggestions for future research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61(5):751–760. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.5.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR. Measurement of the effects of abstinence from tobacco: a qualitative review. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21(2):127–137. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahng S, Wood PK, Trull TJ. Analysis of affective instability in ecological momentary assessment: Indices using successive difference and group comparison via multilevel modeling. Psychological Methods. 2008;13(4):354–375. doi: 10.1037/a0014173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Brown RA, Ramsey SE, Niaura R, Abrams DB, Goldstein MG, et al. Negative mood, depressive symptoms, and major depression after smoking cessation treatment in smokers with a history of major depressive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111(4):670–675. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird NM. Missing data in longitudinal studies. Statistics in Medicine. 1988;7(1-2):305–315. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780070131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM, Waters AJ, Boyd S, Moolchan ET, Lerman C, Pickworth WB. Gender differences in acute tobacco withdrawal: effects on subjective, cognitive, and physiological measures. Experimental & Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;15(1):21–36. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy DE, Piasecki TM, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Life before and after quitting smoking: an electronic diary study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115(3):454–466. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraven M, Baumeister RF. Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126(2):247–259. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraven M, Shmueli D. The self-control costs of fighting the temptation to drink. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20(2):154–160. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.2.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neter J, Kutner MH, Nachtsheim CJ, Wasserman W. Applied Linear Statistical Models. Mc-Graw-Hill Companies; Chicago: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell KA, Schwartz JE, Shiffman S. Do resisted temptations during smoking cessation deplete or augment self-control resources? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22(4):486–495. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.4.486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA. Does smoking cue-induced craving tell us anything important about nicotine dependence? Addiction. 2009;104(10):1610–1616. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Profiles of discouragement: Two studies in variability in the time course of smoking withdrawal symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107(2):238–251. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM, Jorenby DE, Smith SS, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Smoking withdrawal dynamics: I. Abstinence distress in lapsers and abstainers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003a;112(1):3–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM, Jorenby DE, Smith SS, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Smoking withdrawal dynamics: II. Improved tests of withdrawal-relapse relations. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003b;112(1):14–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM, Jorenby DE, Smith SS, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Smoking withdrawal dynamics: III. Correlates of withdrawal heterogeneity. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2003c;11(4):276–285. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.11.4.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM, Niaura R, Shadel WG, Abrams D, Goldstein M, Fiore MC, et al. Smoking withdrawal dynamics in unaided quitters. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109(1):74–86. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper ME, Federmen EB, McCarthy DE, Bolt DM, Smith SS, Fiore MC, et al. Using mediational models to explore the nature of tobacco motivation and tobacco treatment effects. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117(1):94–105. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutledge T, Loh C. Effect sizes and statistical testing in the determination of clinical significance in behavioral medicine research. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;27(2):138–145. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2702_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Comments on craving. Addiction. 2000;95(Suppl 2):S171–175. doi: 10.1080/09652140050111744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Dynamic influences on smoking relapse process. Journal of Personality. 2005;73(6):1715–1748. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2005.00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Engberg JB, Paty JA, Perz WG, Gnys M, Kassel JD, et al. A day at a time: predicting smoking lapse from daily urge. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106(1):104–116. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Ferguson SG. Nicotine patch therapy prior to quitting smoking: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2008;103(4):557–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Gnys M, Richards TJ, Paty JA, Hickcox M, Kassel JD. Temptations to smoke after quitting: a comparison of lapsers and maintainers. Health Psychology. 1996;15(6):455–461. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.6.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Paty J. Smoking patterns and dependence: contrasting chippers and heavy smokers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115(3):509–523. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon RI. An opponent process theory of acquired motivation: The affective dynamics of addiction. In: Maser JD, Seligman MEP, editors. Psychopathology: Experimental models. W. H. Freeman; San Francisco: 1977. pp. 66–103. [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, Shiffman S, Atienza AA, Nebeling L. Historical roots and rationale of ecological momentary assessment (EMA) In: Stone AA, Shiffman S, Atienza AA, Nebeling L, editors. The science of real-time data capture: Self-reports in health research. University Press; Oxford: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Twisk JWR. Applied multilevel analysis. Cambridge University Press; United Kingdom: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Welsch SK, Smith SS, Wetter DW, Jorenby DE, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Development and validation of the Wisconsin Smoking Withdrawal. Experimental & Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1999;7(4):354–361. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.4.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetter DW, Kenford SL, Smith SS, Fiore MC, Jorenby DE, Baker TB. Gender differences in smoking cessation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67(4):555–562. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetter DW, McClure JB, Cofta-Woerpel L, Costello TJ, Reitzel LR, Businelle MS, et al. A randomized clinical trial of a palmtop computer-delivered treatment for smoking relapse prevention among women. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. doi: 10.1037/a0022797. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu R. Measuring explained variation in linear mixed effects models. Statistics in Medicine. 2003;22(22):3527–3541. doi: 10.1002/sim.1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]