Dapsone (4,4′-diaminodiphenylsulfone; DDS) is a sulfone antimicrobial used to treat leprosy, malaria, and inflammatory dermatoses and to prevent and treat opportunistic infections in immunocompromised patients, particularly those who cannot tolerate sulfonamide antimicrobials.1 However, dapsone can lead to dose-dependent hematologic toxicity and is the most commonly recognized cause of acquired methemoglobinemia in human patients.2 The hydroxylamine metabolite of dapsone oxidizes the iron moiety of hemoglobin,3 which leads to increased levels of methemoglobin, impaired oxygen delivery, and cyanosis. Dapsone hydroxylamine is generated by CYP2C9 and CYP2C19, with minor contributions from other P450s.4,5 A rapid activity variant for CYP2C19 (CYP2C19*17) has been reported6 but not for CYP2C9.

Dapsone hydroxylamine is detoxified by cytochrome b5 (b5) and its electron donor, cytochrome b5 reductase (b5R),7 which are expressed in blood, liver, and other tissues. This reduction pathway converts the hydroxylamine back to the parent dapsone. Dapsone itself is inactivated and eliminated following N-acetylation by the enzyme NAT2 in the liver,8 and impaired N-acetylation activity is a risk factor for hematologic and neurologic toxicity from dapsone.9,10 However, genotypic analysis of the CYP2C19, NAT2, and b5/b5R pathways has not been performed in the setting of dapsone-associated methemoglobinemia.

This report describes a patient who developed methemoglobinemia at prophylactic dosages of dapsone, for which we characterized wild-type alleles at the CYP2C19*17 loci, but low activity of the b5/b5R pathway along with low expression of the CYB5A gene encoding b5, and a homozygous slow NAT2*5B haplotype, both of which may have contributed to defective dapsone detoxification.

CLINICAL CASE SUMMARY

A 69-year-old white man had a history of diabetes mellitus and hypertension, leading to chronic renal failure. The patient had been diagnosed with possible sulfonamide hypersensitivity 30 years previously, characterized by fever and malaise after a short course of trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX); however, complete medical records were not available. In July 2008, the patient received a cadaveric renal transplant because of progressive diabetic nephropathy; the donor was cytomegalovirus (CMV) positive. The patient received immunosuppressive dosages of glucocorticoids, mycophenolate mofetil, basiliximab, and tacrolimus for the renal transplant; insulin for his diabetes; and prophylaxis against CMV with valganciclovir and against Pneumocystis jiroveci (formerly carinii) with dapsone (100 mg, 3 days per week). The first-line antimicrobial for Pneumocystis prophylaxis, TMP-SMX,11 was not prescribed given the history of possible sulfonamide hypersensitivity. The patient was HIV negative and had no personal or family history of cyanosis.

One week after discharge, the patient presented with a 3-day complaint of fatigue and progressive shortness of breath. On physical examination, the patient had mild tachypnea and cyanosis. Oxygen saturation by pulse oximeter was 85% with supplemental nasal oxygen; the previously normal hemoglobin concentration had dropped to 9 g/dL. Chest radiographs were normal, and there was no evidence of venous thromboembolism on ultrasound examination. Arterial blood gas revealed a Pao2 of 109 torr while the patient was inspiring 50% oxygen, along with a high but unquantified level of methemoglobinemia by arterial blood gas analysis. Cyanosis, as seen in this patient, is typically associated with methemoglobin levels >10%–20%; methemoglobin levels >50% are often associated with respiratory failure, altered mental status, and other neurological symptoms,12 none of which this patient exhibited. Therefore, the methemoglobin levels were estimated to be between 10% and 50%. The reticulocyte count was increased at 4.9%, with a negative direct antiglobulin test and no haptoglobin depletion. Serum lactate dehydrogenase was only slightly elevated at 391 U/dL (135–225 U/L). White blood cell and platelet counts were normal; unfortunately, staining for Heinz bodies was not performed.

Because of the patient’s cyanosis and the history of dapsone administration, a presumptive diagnosis of drug-induced methemoglobinemia was made. The patient was administered a single dose of methylene blue (60 mg intravenously), with dramatic resolution of the cyanosis. As there was no evidence of hemorrhage, the regenerative anemia was attributed to hemolysis secondary to oxidative damage to the red cells. During a 2-week recovery period, specific measurements for methemoglobin were obtained by co-oximetry, and the patient’s methemoglobin levels continued to be elevated at approximately 2%–3% (normal, 0.0%–0.9%). Once the reticulocyte count had normalized, the patient was tested for red blood cell glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency; however, activity was normal at 21 U/g hemoglobin (normal range, 7.0–20.5).

After the episode of methemoglobinemia, dapsone was discontinued and pentamidine was initiated for Pneumocystis prophylaxis. Twelve weeks after the resolution of methemoglobinemia, 12 mL of whole blood in heparin was obtained, with informed consent, and sent overnight to the University of Wisconsin– Madison for genotyping of NAT2, CYP2C19, CYB5A (which encodes b5), and CYB5R3 (which encodes b5R), as well as evaluation of b5/b5R activity and expression. At the time of sampling, the patient was being treated with pentamidine 300 mg monthly, prednisone 10 mg daily, tacrolimus 5 mg twice daily, mycophenolate mofetil 1 g twice daily, and insulin.

METHODS

Sample Collection and Handling

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from whole blood upon receipt, using Histopaque density gradient media (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri). Viability of the PBMCs was determined using trypan blue dye exclusion, and aliquots of cells were frozen directly for activity assays and genomic DNA isolation and in RNAlater preservative solution (Ambion Inc, Austin, Texas) for RNA isolation.

Reduction Activities of b5 and b5R

The reduction capacity of b5 and b5R was determined in the patient’s leukocytes using the classic substrate, cytochrome c.13 Briefly, PBMCs (30 µg) were incubated with 80 µM cytochrome c (Sigma Aldrich) in phosphate-buffered saline at pH 7.4. Dicumarol (10 µM, MP Biomedicals, Solon, Ohio) was included to inhibit competing NADPH/quinone oxidoreductase activity.13 After preincubation for 1 minute at 37°C, NADH (1 mM; Sigma Aldrich) was added to the reaction, and reduction of cytochrome c was measured over time by spectrophotometry at 550 nm (Beckman DU-640B spectrophotometer). Normal reduction activities for comparison were established in 29 healthy, predominantly white subjects, with a median age of 46 years (range, 20–61 years). The University of Wisconsin–Madison Institutional Review Board approved all blood collection procedures.

CYB5A and CYB5R3 expression

Total RNA was isolated from PBMC using an RNAqueous-4PCR kit (Ambion, Austin, Texas) with DNase treatment. One microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed to complementary DNA (cDNA) using RETROscript RT (Ambion) with oligo (dT) and random decamer primers. Gene-specific primers were designed for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) across introns for CYB5A and CYB5R3 (Table 1) using Primer3Plus software (www.bioinformatics.nl/cgi-bin/primer3plus/primer3plus.cgi). qPCR was performed for each transcript using a SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California), with a final concentration of 0.5 ng/µL cDNA and 200 nM forward and reverse primers and using an ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Quantification cycle (Cq, ie, threshold cycle [CT])14 values were normalized for GAPDH expression (ΔC ).

Table I.

Primers Used for qPCR and for Gene Resequencing of CYB5A, CYB5R3, NAT2, and CYP2C19

| Region | Experiment | Orientation | Primer Sequence (5′→3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYB5A | |||

| qPCR | Forward | GCCAGGGAAATGTCCAAAAC | |

| Reverse | CGTGGAGCGCTGGAACAG | ||

| Coding | PCR and resequencing | Forward | GGCCTGGCTCGCGGCGAACCGAG |

| Reverse | CTCCCGTGTCCAAAGCAGGC | ||

| Promoter | PCR and resequencing | Forwarda | AGGACGAGGCATTCCAAAAC |

| Reversea | AATCGCGGGAGTTTCCTATT | ||

| Forwardb | GGACTGCTGCCAATAGGAAA | ||

| Reverseb | TCTTGCTGTGGTGTGCTTC | ||

| 3′ UTR | PCR and resequencing | Forward | TTTTGAGTCCACCACAGTGC |

| Reverse | CCTCTGTGGGTCTGGATGAG | ||

| CYB5R3 | |||

| qPCR | Forward | GCCCAGCTCAGCACGTTG | |

| Reverse | CGTGGAGCGCTGGAACAG | ||

| Coding | PCR | Forward | ACCATGGGGGCCCAGCTCA ACTGGGTGAGCGTGAACAG |

| Reverse | |||

| Resequencing | Forward | CTACCTCTCGGCTCGAATTG TGTCTCCAATCTGCATGCTC | |

| Reverse | |||

| Promoter | PCR and resequencing | Forward | GTACGGGACTTCAAACCA |

| (exon1M) | Reverse | CGTAAGTAGCGGTCACCA | |

| CpG island | PCR and resequencing | Forward | CATCCATTCAACAAGTATTTAGGC |

| Reverse | GACAGAGTCTCGCCCTGTCC | ||

| PCR | Reverse | CTCGGCTCACCGCAAACT | |

| 3`UTR | PCR and resequencing | Forwarda | AGCCTCTCCATTCTTCAGCA |

| Reversea | CCTGGCACCTGCAGCTTT | ||

| Forwardb | CCACACACACTATAAGGCTGA | ||

| Reverseb | GGCAGACCCTCGAGGAGCTAGA | ||

| β-actin | qPCR | Forward | AGGCACTCTTCCAGCCTTC |

| Reverse | GGATGTCCACGTCACACTTC | ||

| GAPDH | qPCR | Forward | CAACTTTGGTATCGTGGAAGG |

| Reverse | CATCACGCCACAGTTTCC | ||

| NAT2 | Resequencing | Forward | CATGTAAAAGGGATTCATGCAG |

| Reverse | CGTGAGGGTAGAGAGGATATCTG | ||

| CYP2C19 | Resequencing | Forward | TGACAAGACACAGACTGGGATAA |

| –3402 locus | Reverse | CCTTGCCAGTGTTTGGTTCT | |

| CYP2C19 | Resequencing | Forward | GCCTGTTTTATGAACAGGATGA |

| –806 locus | Reverse | GAGACCCTGGGAGAACAGG |

PCR, polymerase chain reaction; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

Amplify 5′ end of target sequence.

Amplify 3′ end of target sequence.

Relative quantification of gene expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method, with mean ΔCT values generated from leukocyte cDNA from 29 healthy subjects used as the calibrator sample. Specificity of products was confirmed by melting curve analyses and by agarose gel visualization of products.

CYB5A, CYB5R3, and NAT2 Resequencing and CYP2C19*17 Genotyping

Primers were designed to amplify the entire coding sequences of CYB5A and CYB5R3 from leukocyte cDNA (Table 1). Thermocycler parameters were as described previously.15 The promoter and 3′ untranslated regions of the 2 genes were amplified from genomic DNA, as isolated from PBMC using the DNeasy Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, California). The amplicon that contained the known CYB5A promoter region16 comprised 728 base pairs (bp) upstream of the translation start site and the first 73 bases of the translated region of exon 1, whereas the amplicon that contained the previously characterized CYB5R3 promoter region17 started at −683 bp in the 5′ flanking region, spanned the entire exon 1M, and ended at +207 in intron 1. CpG Island Searcher (http://cpgislands.usc.edu) was used to locate CpG islands further upstream from either gene; these sites may influence gene expression via methylation.18 An additional upstream CpG island was identified for CYB5R3, located between −1530 and −1071 bp from the start codon, and was separately resequenced for the patient.

The coding region of the NAT2 gene, located within a single exon, was amplified from genomic DNA by PCR (Table 1). The rapid-activity (highly inducible) CYP2C19*17 allele is composed of 2 polymorphic sites: −3402C>T and −806C>T; the latter is associated with increased transcriptional activity of CYP2C19.6 These 2 regions were amplified and resequenced from patient genomic DNA, using primers listed in Table 1.

PCR products from CYB5A, CYB5R3, and NAT2 were sequenced in both directions using BigDye Terminator v3.1 reagents (Applied Biosystems) and an ABI 3700 DNA sequencer. Sequences were aligned with reference cDNA sequences (NM_148923 for CYB5A, NM_000398 for CYB5R3) and with human genomic DNA sequences (hg19; UCSC genome browser) for the coding region of NAT2 and the promoter and 3′ untranslated regions of CYB5A and CYB5R3, using Staden software (http://staden.sourceforge.net).

RESULTS

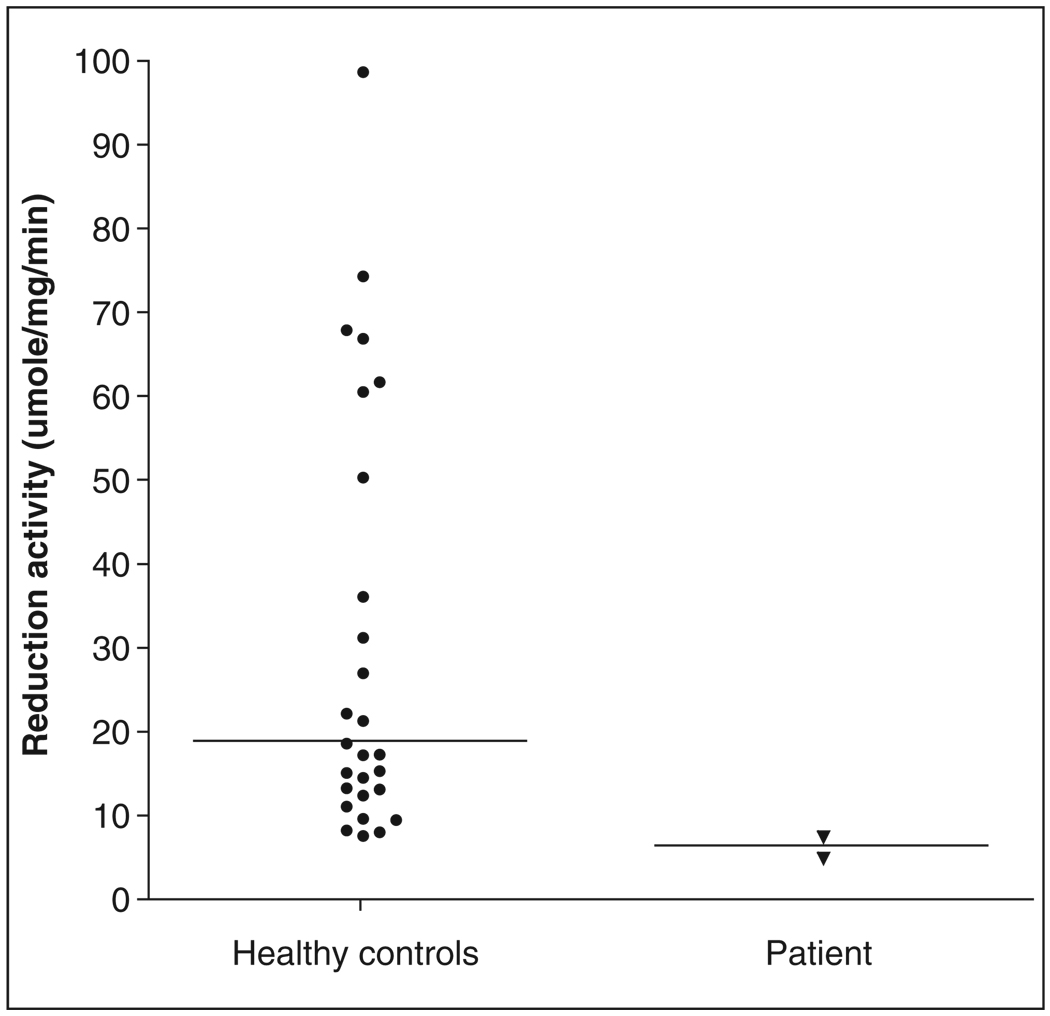

Mean reduction activity in the patient’s PBMC, measured in 2 separate assays, was 6.4 µmol/mg/ min, which was outside of the observed range for values measured in 29 healthy control subjects (median 18.9 µmol/mg/min, range 7.9–174 µmol/ mg/min, Figure 1). Consistent with low reduction activity in PBMCs, expression of both leukocyte CYB5A and CYB5R3 was decreased in the patient compared with the healthy controls (relative quantity value 0.22 for CYB5A and 0.41 for CYB5R3); this was repeatable in several assays. Despite low CYB5A expression, no polymorphisms could be identified in the coding, promoter, or 3′ UTR of CYB5A in this patient. Although several CYB5R3 SNPs were found in the patient, none were novel and none have been associated with low b5R expression or activity in human liver.15

Figure 1.

Cytochrome c reduction activity in the patient’s peripheral blood mononuclear leukocytes (measured in 2 separate assays) was lower than all values observed in 29 healthy control subjects.

When NAT2 was resequenced, the patient was found to be homozygous for the slow-acetylator genotype 341T>C (Ile114Thr), in association with 481 C>T and 803A>G, to constitute the NAT2*5B haplotype (rs1801280). NAT2 activity was not evaluated, since this isoform is not expressed in peripheral blood.19 Another subject, a white woman with a history of sulfamethoxazole-associated skin rash, was also homozygous for the same 341T>C (Ile114Thr) allele (data not shown). The patient’s genomic DNA was resequenced at the CYP2C19*17 loci. The patient was homozygous wild-type for both −3402C and −806C (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Dapsone is indicated for preventing P jiroveci pneumonia in immunocompromised patients, particularly in those patients with prior adverse reactions to TMP-SMX. Although dapsone is usually well tolerated, it is one of the most common drugs implicated in acquired methemoglobinemia.2 Dapsone-associated methemoglobinemia has been reported after stem cell transplant,20 after solid organ transplant,21–23 and during radiation and chemotherapy,24 but no genotypic risk factors have been explored.

Clinical risk factors associated with dapsone methemoglobinemia include renal failure,25 administration of other drugs known to contribute to methemoglobinemia (lidocaine, benzocaine, prilocaine, acetaminophen, nitroprusside, phenazopyridine, and possibly zopiclone),26,27 slow N-acetyltransferase 2 activity,9,10 and decreased G6PD activity.28 G6PD is necessary to generate NADPH, which otherwise maintains adequate glutathione concentrations within erythrocytes; this counteracts oxidation of hemoglobin. In this patient, no other drugs had been given that are known to cause methemoglobinemia, and G6PD activity was normal. This patient did have a history of renal failure, which may have contributed to risk; at the time of dapsone administration, his serum creatinine averaged 3.0 to 4.0 mg/dL. However, serum dapsone concentrations were not measured at the time of the adverse reaction. When considering all of the factors in this case using the Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale, this patient’s score was, conservatively, 5, indicating a “probable” adverse drug reaction.29

Dapsone methemoglobinemia is caused by its oxidative metabolite, dapsone hydroxylamine.3 This metabolite is detoxified by b5 and b5R,7 which show pharmacogenetic variability.15,30 We hypothesized that this pathway might be impaired in this patient, and we indeed found very low b5/b5R reduction activity in this patient’s leukocytes, decreased by about 65% compared with the mean of healthy controls. Low b5/b5R activity was previously found in 3 pediatric patients who developed methemoglobinemia during dapsone treatment.31 Reduction activities in affected children were decreased by about 13% to 45% compared with the mean of unaffected patients. However, the mechanism for this was not explored.

The patient in this study showed low leukocyte messenger RNA (mRNA) expression for CYB5A and CYB5R3 compared with healthy controls, which is consistent with the patient’s low reduction activities. However, we did not identify any coding, promoter, or 3′UTR polymorphisms in either gene that might explain low activity. This patient may have had a polymorphism in an unexamined region of either gene or, more likely, downregulation of CYB5A and CYB5R3 expression secondary to drug therapy or disease factors. Although the expression of CYB5A and CYB5R3 is highly correlated and appears to be co-regulated,15 little is known about drug and disease effects on the transcriptional regulation of this detoxification pathway. Studies of this are underway in our laboratory.

This patient was homozygous for the NAT2*5B haplotype containing the nonsynonymous SNP 341T>C. This SNP leads to enhanced degradation of NAT2 and results in markedly decreased N-acetylation activity.32,33 The NAT2*5B haplotype has been associated with impaired biotransformation of isoniazid34 and, along with other slow NAT2 genotypes, is a risk factor for dose-dependent adverse reactions to sulfasalazine.35 These drugs share structural similarities with dapsone; however, NAT2 genotypes have not been previously evaluated in association with adverse reactions to dapsone. Because up to 18% of whites are homozygous for 341T>C (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP; rs 1801280), further work is needed to determine whether this genotype, or the larger NAT2*5B haplotype, confers risk for dapsone methemoglobinemia. The patient was negative for the rapid CYP2C19*17 genotype, which, if present, could have contributed to increased dapsone hydroxylamine generation. Although we did not genotype for slow allelic variants of CYP2C9, the presence of 1 or more of these variants might have had a protective effect against dapsone hydroxy-lamine formation in this patient.5

Null mutations in the GSTM1 and GSTT1 genes have been associated with idiosyncratic toxicity from drugs such as the withdrawn oral hypoglycemic agent troglitazone36 and the cholinesterase inhibitor tacrine.37 A recent study of a patient with rash and arthralgia following TMP-SMX administration found a homozygous NAT2*5B genotype, as in our patient, and null GSTM1 and GSTT1 genotypes.38 Since GSTs are not involved in SMX disposition39 and have not been reported in association with dapsone clearance, we did not genotype for these null variants. However, it is possible that null mutations in either gene may have predisposed our patient to dapsone methemoglobinemia.

Dapsone and sulfamethoxazole are both arylamine compounds and generate similar hydroxylamine metabolites that lead to adverse drug reactions; both drugs are also metabolized by NAT2 and b5/b5R pathways.7,40 It is therefore possible that this patient experienced adverse reactions to both sulfamethoxazole and dapsone because of the same underlying risk factors. Cross-reactivity between hypersensitivity to TMP-SMX and dapsone has been reported and may approach 40% in some immunocompromised populations.41–44 However, the risk factors for this shared sensitivity require further investigation.

In conclusion, this patient developed methemoglobinemia on low prophylactic dosages of dapsone that are typically well tolerated. Genotyping revealed a homozygous slow NAT2*5B haplotype, along with low CYB5A and CYB5R3 expression and b5/ b5R reduction activity, but no evidence of rapid CYP2C19*17 genotype. Either or both of these pathways may have contributed to the risk of this adverse event, and further work will determine whether these detoxification defects confer risk for dapsone methemoglobinemia in the general population.

Acknowledgments

Financial disclosure: This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences, grant R01 GM61753. No authors are fellows of the American College of Clinical Pharmacology.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Giullian JA, Cavanaugh K, Schaefer H. Lower risk of urinary tract infection with low-dose trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole compared with dapsone prophylaxis in older renal transplant patients on a rapid steroid-withdrawal immunosuppression regimen. Clin Transplant. 2009;24:636–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2009.01129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ash-Bernal R, Wise R, Wright SM. Acquired methemoglobinemia: a retrospective series of 138 cases at 2 teaching hospitals. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004;83:265–273. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000141096.00377.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reilly T, Woster P, Svensson C. Methemoglobin formation by hydroxylamine metabolites of sulfamethoxazole and dapsone: implications for differences in adverse drugs reactions. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;288:951–959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganesan S, Tekwani BL, Sahu R, Tripathi LM, Walker LA. Cytochrome P(450)-dependent toxic effects of primaquine on human erythrocytes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;241:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winter HR, Wang Y, Unadkat JD. CYP2C8/9 mediate dapsone N-hydroxylation at clinical concentrations of dapsone. Drug Metab Dispos. 2000;28:865–868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sim SC, Risinger C, Dahl ML, et al. A common novel CYP2C19 gene variant causes ultrarapid drug metabolism relevant for the drug response to proton pump inhibitors and antidepressants. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;79:103–113. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurian J, Bajad S, Miller J, Chin N, Trepanier L. NADH cytochrome b5 reductase and cytochrome b5 catalyze the microsomal reduction of xenobiotic hydroxylamines and amidoximes in humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311:1171–1178. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.072389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palamanda JR, Hickman D, Ward A, Sim E, Romkes-Sparks M, Unadkat JD. Dapsone acetylation by human liver arylamine N-acetyltransferases and interaction with antiopportunistic infection drugs. Drug Metab Dispos. 1995;23:473–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bluhm R, Adedoyin A, McCarver D, Branch R. Development of dapsone toxicity in patients with inflammatory dermatoses: activity of acetylation and hydroxylation of dapsone as risk factors. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1999;65:598–605. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(99)90081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffmann TK, von Schmiedeberg S, Wulferink M, et al. Dapsone-induced agranulocytosis: the role of xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes demonstrated by a case report. Hautarzt. 2005;56:673–677. doi: 10.1007/s00105-004-0877-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodriguez M, Fishman JA. Prevention of infection due to Pneumocystis spp. in human immunodeficiency virus-negative immunocompromised patients. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:770–782. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.4.770-782.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright RO, Lewander WJ, Woolf AD. Methemoglobinemia: etiology, pharmacology, and clinical management. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34:646–656. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70167-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitzsimmons S, Workman P, Grever M, Paull K, Camalier R, Lewis A. reductase enzyme expression across the NCI tumor cell line panel: correlation with sensitivity to mitomycin C and EO9. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:259–269. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.5.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, et al. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem. 2009;55:611–622. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sacco J, Trepanier L. Cytochrome b5 and NADH cytochrome b5 reductase: genotype-phenotype correlations for hydroxylamine reduction. Pharmacogenet Genom. 2010;20:26–37. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3283343296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang N, Dardis A, Miller W. Regulation of cytochrome b5 gene transcription by Sp3, GATA-6 and SF1 in human adrenal NCI-H295A cells [published online ahead of print April 14, 2005] Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:2020–2034. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toyoda A, Fukumaki A, Hattori M, Sakaki Y. Mode of activation of the GC box/Sp1-dependent promoter of the human NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase-encoding gene. Gene. 1995;164:351–355. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00443-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones PA. The DNA methylation paradox. Trends Genet. 1999;15:34–37. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01636-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cribb AE, Grant DM, Miller MA, Spielberg SP. Expression of monomorphic arylamine N-acetyltransferase (NAT1) in human leukocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;259:1241–1246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunford LM, Roy DM, Hahn TE, et al. Dapsone-induced methemoglobinemia after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:241–242. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plotkin JS, Buell JF, Njoku MJ, et al. Methemoglobinemia associated with dapsone treatment in solid organ transplant recipients: a two-case report and review. Liver Transpl Surg. 1997;3:149–152. doi: 10.1002/lt.500030207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Talarico JF, Metro DG. Presentation of dapsone-induced methemoglobinemia in a patient status post small bowel transplant. J Clin Anesth. 2005;17:568–570. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ward KE, McCarthy MW. Dapsone-induced methemoglobinemia. Ann Pharmacother. 1998;32:549–553. doi: 10.1345/aph.17003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walker JG, Kadia T, Brown L, Juneja HS, de Groot JF. Dapsone induced methemoglobinemia in a patient with glioblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2009;94:149–152. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-9813-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naik PM, Lyon GM, 3rd, Ramirez A, et al. Dapsone-induced hemolytic anemia in lung allograft recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008;27:1198–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fung HT, Lai CH, Wong OF, Lam KK, Kam CW. Two cases of methemoglobinemia following zopiclone ingestion. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2008;46:167–170. doi: 10.1080/15563650701305558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turner MD, Karlis V, Glickman RS. The recognition, physiology, and treatment of medication-induced methemoglobinemia: a case report. Anesth Prog. 2007;54:115–117. doi: 10.2344/0003-3006(2007)54[115:TRPATO]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Degowin RL, Eppes RB, Powell RD, Carson PE. The haemolytic effects of diaphenylsulfone (DDS) in normal subjects and in those with glucose-6-phosphate-dehydrogenase deficiency. Bull World Health Organ. 1966;35:165–179. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naranjo C, Busto U, Sellers E, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239–245. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurian JR, Longlais BJ, Trepanier LA. Discovery and characterization of a cytochrome b5 variant with impaired hydroxylamine reduction capacity. Pharmacogenet Genom. 2006;19:1366–1373. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328011aaff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams S, MacDonald P, Hoyer J, Barr R, Atahle U. Methemoglobinemia in children with acute lymphobastic leukemia (ALL) receiving dapsone for Pneumocystis carinii prophylaxis: a correlation with cytochrome b5 reductase (Cb5R) enzyme levels. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2004:431–438. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fretland AJ, Leff MA, Doll MA, Hein DW. Functional characterization of human N-acetyltransferase 2 (NAT2) single nucleotide polymorphisms. Pharmacogenetics. 2001;11:207–215. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200104000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zang Y, Zhao S, Doll MA, States JC, Hein DW. The T341C (Ile114Thr) polymorphism of N-acetyltransferase 2 yields slow acetylator phenotype by enhanced protein degradation. Pharmacogenetics. 2004;14:717–723. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200411000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kita T, Tanigawara Y, Chikazawa S, et al. N-Acetyltransferase2 genotype correlated with isoniazid acetylation in Japanese tuberculous patients. Biol Pharm Bull. 2001;24:544–549. doi: 10.1248/bpb.24.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen M, Xia B, Chen B, et al. N-acetyltransferase 2 slow acetylator genotype associated with adverse effects of sulphasalazine in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21:155–158. doi: 10.1155/2007/976804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watanabe I, Tomita A, Shimizu M, et al. A study to survey susceptible genetic factors responsible for troglitazone-associated hepatotoxicity in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;73:435–455. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9236(03)00014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simon T, Becquemont L, Mary-Krause M, et al. Combined glutathione-S-transferase M1 and T1 genetic polymorphism and tacrine hepatotoxicity. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2000;67:432–437. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2000.104944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.LaRocca D, Lehmann DF, Perl A, et al. The combination of nuclear and mitochondrial mutations as a risk factor for idiosyncratic toxicity. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:249–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02743.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cribb AE, Miller M, Leeder JS, et al. Reactions of the nitroso and hydroxylamine metabolites of sulfamethoxazole with reduced glutathione. Implications for idiosyncratic toxicity. Drug Metab Dispos. 1991;19:900–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rothman N, Hayes RB, Bi W, et al. Correlation between N-acetyltransferase activity and NAT2 genotype in Chinese males. Pharmacogenetics. 1993;3:250–255. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199310000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holtzer C, Flaherty J, Coleman R. Cross-reactivity in HIV-infected patients switched from trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole to dapsone. Pharmacotherapy. 1998;18:831–835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hughes WT. Use of dapsone in the prevention and treatment of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia: a review. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:191–204. doi: 10.1086/514626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jorde U, Horowitz H, Wormser G. Utility of dapsone for prophylaxis of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-intolerant, HIV-infected individuals. AIDS. 1993;7:355–359. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199303000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mandrell BN, McCormick JN. Dapsone-induced methemoglobinemia in pediatric oncology patients: case examples. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2001;18:224–228. doi: 10.1053/jpon.2001.26876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]