Abstract

Background

Hemochromatosis, North America’s most prevalent genetic disorder, tends to present with an insidious onset and subtle, yet characteristic findings. Patients tend to present with both constitutional symptoms and end-organ effects.

Methods

Clinical criteria such as history, physical examination, imaging criteria with focused radiologic constellations, and laboratory findings were used for diagnosis.

Results

We report the case of a man who lacked classic systemic symptoms, but instead presented with isolated metacarpophalangeal joint disease and characteristic radiologic findings. The diagnosis was confirmed by serum iron studies and subsequent genetic work-up.

Conclusions

A high index of clinical suspicion is required to diagnose early disease; better prognostic responses are expected with treatment of less severe disease. Hand surgeons should be aware of the characteristic findings for this rare presentation so proper treatment can be initiated early.

Keywords: Hemochromatosis, Metacarpophalangeal joint, Arthropathy, Osteoarthritis, Arthritis, MPJ, MCP joint

Introduction

Hereditary hemochromatosis is the most common genetic disorder in North America with an incidence of 1 in every 200–400 individuals [13], with a marked predilection for those of Northern European decent (up to 1 in every 10 individuals) [15]. It also displays a male preponderance, perhaps due to female cyclic physiologic blood loss and potential sex gene-based disease modification [9].

This disease causes genetically driven increased enteric absorption of iron with progressive total body iron overload [24] and typically presents clinically between the third and fifth decades as tissue concentrations rise to toxic levels [4, 9]. Iron deposition in skin produces a bronzing effect, while involvement of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis and fibrosis of the Leydig cells of the testis lead to hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Hepatic iron overload eventually results in cirrhosis with increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Pancreatic involvement creates endocrine dysfunction, primarily brittle diabetes due to islet cell failure. Myocardial iron accumulation may cause congestive heart failure, while deposits in the bundle of His and the Purkinje system lead to arrhythmias [6]. Joint pathology presents as arthritis.

Early hepatic involvement and endocrinopathies (e.g., hypothalamic-pituitary systems) produce symptoms of lethargy, fatigue, and decreased libido early in the natural history of the disease. Arthritis generally tends to follow this.

If left unrecognized and untreated, hemochromatosis can lead to debilitating and life-threatening outcomes. Death may result from progression to the development of liver failure, hepatocellular carcinoma, heart failure, diabetes, and fatal arrhythmias. Treatment via therapeutic phlebotomy and low-iron dietary modification can be a simple and highly effective therapy, especially when instituted early [23].

Here we discuss a previously undiagnosed patient who presented atypically with isolated asymmetric bilateral second metacarpal-phalangeal joint (MPJ) arthritis and subtle yet suspicious radiologic findings in the absence of more typical early signs and symptoms of hemochromatosis.

Case Report

A 39-year-old white male was referred for the evaluation of bilateral progressive hand pain with intermittent MPJ swelling over the past 6 months. He denied a history of prior hand trauma or family history of arthropathies. The review of systems was unremarkable.

Physical exam revealed mild swelling and tenderness over the second MPJs bilaterally, right worse than left. There were neither sensorimotor deficits nor associated skin changes.

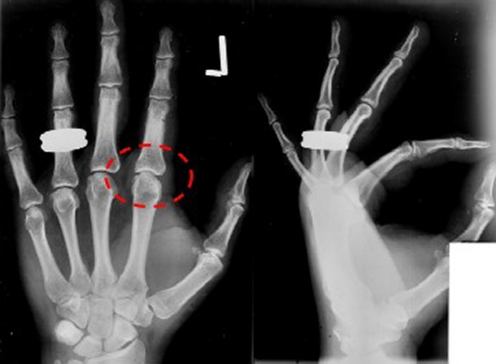

Standard PA, lateral, and oblique X-rays (Figs. 1 and 2 below) revealed classic findings of metacarpal head osteophyte formation in a radial bird’s beak pattern with MPJ space narrowing and chondrocalcinosis.

Fig. 1.

Radiologic findings, right hand. Note changes at the MPJ

Fig. 2.

Radiologic findings, left hand. Note changes at the MPJ

Serum iron-binding studies revealed markedly elevated serum levels of iron (215 μg/dL; lab normal range, 40–190 μg/dL), transferrin saturation (96%; lab normal range, 12–57%), and ferritin (2,318 μg/L; lab normal range, 18–350 μg/L).

He was referred to a hematologist for further work-up; genetic studies confirmed hemochromatosis related to a C282Y mutation. The patient subsequently began serial phlebotomies as definitive treatment.

Discussion

Arthritis of hemochromatosis typically affects the second and third MPJs [8, 9]; however, the knees, hips, and wrists may also be involved. Between 25–50% of patients develop this as part of their disease process. The pathology is characterized by chondrocalcinosis and hemosiderin deposition in the synovial linings [5, 17, 18].

Radiologic findings in the hand include chondrocalcinosis (which is indistinguishable from that of pseudogout arthropathy) and distinguishing signs such as hook-like osteophyte formation on the radial aspects of affected metacarpal heads and a predilection for the MPJ rather than other joints such as the scapholunate (a joint commonly affected by pseudogout) [2, 3]. Joint space narrowing, subchondral cyst formation, and subchondral sclerosis may also be evident [20].

Screening studies include total serum iron, total iron-binding capacity, transferrin saturation, and serum ferritin. Fasting transferrin saturation ≥45% is the most sensitive screening test, able to rule out virtually all unaffected individuals [12]. Serum ferritin serves as a proxy for total body iron levels; but while hepatic ferritin production is upregulated in iron overload, it is also overproduced in conjunction with alcohol abuse, metabolic syndrome, inflammatory conditions, and acute or chronic hepatitis [1, 10]. Elevated ferritin levels tend to be associated with more advanced disease; levels over 1,000 μg/L portend a higher risk of cirrhosis and serve as an independent indication for liver biopsy.[21] Together, normal serum transferrin saturation and ferritin levels signify a 97% negative predictive value for hemochromatosis.

Genetic tests are available to confirm the diagnosis when indicated. While a majority of clinically significant hereditary cases are due to homozygous C282Y mutations of the HFE gene, the H63D mutation is also clinically relevant. Several other less common non-HFE mutations have also been identified in hemochromatosis. However, the presence of the mutation does not in-and-of itself guarantee phenotypic expression of the disease [7, 19].

Therapeutic phlebotomy is considered first-line therapy. While standardized guidelines are lacking, efficacy has been reported with an induction regimen of bleeding one unit weekly (i.e., 200–250 mg iron) until ferritin levels normalize to within 25–50 μg/L, followed by maintenance removal of two to four units annually to keep ferritin levels between 50 and 100 μg/L. In the absence of contraindications, phlebotomized blood should be saved for the transfusion pool. If phlebotomy is contraindicated, such as in the setting of severe anemia or cardiac failure, iron chelators may be considered [8, 16].

Treatment is highly effective in mild to moderate disease. Elements of the disease such as hepatopathy, especially when mild, may be reversed with adequate therapy. The severity of hemochromatosis-related arthritis may correlate with iron stores [22]; however, unlike the other organopathies of hemochromatosis, the arthritis does not regress with treatment [8, 11, 14].

Reports of hemochromatosis presenting with signs including MCP arthritis have been published in the literature of fields such as rheumatology [3, 22], hematology [9, 17], and radiology [2]. However, to date, the hand surgery literature has not referenced this phenomenon; to our knowledge, this represents the first report in our field.

Conclusions

Hand surgeons, like our prime care and rheumatology colleagues, are positioned to receive patients demonstrating the arthritic component of this disease, including those that have not yet been accurately diagnosed. Given the grave sequelae of untreated hemochromatosis and its favorable response to therapy in mild to moderate cases, it stands to reason that the inclusion of this disease process and its radiologic findings in our differential diagnoses may help ameliorate not only patient morbidity but also mortality.

Suggested Algorithm

Suspect disease in the setting of early-onset (between ages 30s and 50s) unexplained arthritis featuring MPJ involvement along with telltale radiologic findings. Suspicious screening hand films reveal hook-like osteophyte formation on the radial aspect of affected metacarpal heads along with MPJ chondrocalcinosis, joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, and relative sparing of other joints (i.e., scapholunate with pseudogout).

Then, rule out autoimmune, gouty, and inflammatory arthritides via a standard arthritis panel. Screen for hemochromatosis with a serum iron panel focusing on fasting transferrin saturation and ferritin levels. If iron studies are positive, refer to a Hematologist for genetic testing, familial counseling, possible liver biopsy, and definitive medical management.

References

- 1.Adams PC, Barton JC. Haemochromatosis. Lancet. 2007;370(9602):1855–1860. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61782-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adamson TC, Resnik CS, Guerra J, et al. Hand and wrist arthropathies of hemochromatosis and calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease: distinct radiographic features. Radiology. 1983;147(2):377–381. doi: 10.1148/radiology.147.2.6300958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Axford JS. Rheumatic manifestations of haemochromatosis. Baillieres Clin Rheum. 1991;5(2):351–365. doi: 10.1016/S0950-3579(05)80287-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bacon BR, Britton RS. Clinical penetrance of hereditary hemochromatosis. N Engl Jour Med. 2008;358(3):221–230. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barton JC, McDonnell S, Adams P. Management of hemochromatosis. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:932–939. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-11_part_2-199812011-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buja L, Roberts W. Iron in the heart. Am Jour Med. 1971;51:209–221. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(71)90240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark P, Britton LJ, Powell LW. The diagnosis and management of hereditary haemochromatosis. Clin Biochem Rev. 2010;31(1):3–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Association for the Study of the Liver EASL clinical practice guidelines on hemochromatosis. Jour Hepatol. 2010;53:3–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franchini M. Hereditary iron overload: update on pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Am Jour Hematology. 2006;81:202–209. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janssen MC, Swinkels DW. Hereditary haemochromatosis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterology. 2009;23(2):171–183. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kowdley KV, Brandhagen DJ, Gish RG, et al. Survival after liver transplantation in patients with hepatic iron overload: the national hemochromatosis transplant registry. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:494–503. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLaren CE, McLachlan GJ, Halliday JW, et al. Distribution of transferrin saturation in an Australian population: relevance to the early diagnosis of hemochromatosis. Gastroenterology. 1998;114(3):543–549. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(98)70538-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merryweather-Clarke AT, Pointon JJ, Sherman JD, et al. Global prevalence of putative haemochromatosis mutations. Jour Med Genet. 1997;34:275–278. doi: 10.1136/jmg.34.4.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niederau C, Fischer R, Sonnenberg A, et al. Survival and causes of death in cirrhotic and in noncirrhotic patients with primary hemochromatosis. N Engl Jour Med. 1985;313:1256–1262. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198511143132004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Njajou OT, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ, Osborne RH, et al. A population-based study of the effect of the HFE C282Y and H63D mutations on iron metabolism. Eur Jour Hum Genet. 2003;11(3):225–231. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pietrangelo A. Hereditary hemochromatosis: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(2):393–408. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piperno A. Classification and diagnosis of iron overload. Haematologica. 1998;83:447–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Powell LW, George DK, McDonnel SM, et al. Diagnosis of hemochromatosis. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:925–931. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-11_part_2-199812011-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross JM, Kowalchuk RM, Shaulinsky J, et al. Association of heterozygous hemochromatosis C282Y gene mutation with hand osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(1):121–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schattenkirchner M, Fischbacher L, Giebner-Fischbacher U, et al. Arthropathy in idiopathic hemochromatosis. Klin Wochenschr. 1983;61(23):1199–1207. doi: 10.1007/BF01537431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tavill AS. Diagnosis and management of hemochromatosis. Hepatology. 2001;33(5):1321–1328. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.24783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valenti L, Fracanzani AL, Rossi V, et al. The hand arthropathy of hereditary hemochromatosis is strongly associated with iron overload. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(1):153–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Witte DL, Crosby WH, Edwards CQ, et al. Hereditary hemochromatosis. Clinica Chimica Acta. 1996;245(2):139–200. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(95)06212-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Worwood M. Inherited iron loading: genetic testing in diagnosis and management. Blood Rev. 2005;19:69–88. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]