Abstract

Effects of partial root-zone irrigation (PRI) on the hydraulic conductivity in the soil–root system (Lsr) in different root zones were investigated using a pot experiment. Maize plants were raised in split-root containers and irrigated on both halves of the container (conventional irrigation, CI), on one side only (fixed PRI, FPRI), or alternately on one of two sides (alternate PRI, APRI). Results show that crop water consumption was significantly correlated with Lsr in both the whole and irrigated root zones for all three irrigation methods but not with Lsr in the non-irrigated root zone of FPRI. The total Lsr in the irrigated root zone of two PRIs was increased by 49.0–92.0% compared with that in a half root zone of CI, suggesting that PRI has a significant compensatory effect of root water uptake. For CI, the contribution of Lsr in a half root zone to Lsr in the whole root zone was ∼50%. For FPRI, the Lsr in the irrigated root zone was close to that of the whole root zone. As for APRI, the Lsr in the irrigated root zone was greater than that of the non-irrigated root zone. In comparison, the Lsr in the non-irrigated root zone of APRI was much higher than that in the dried zone of FPRI. The Lsr in both the whole and irrigated root zones was linearly correlated with soil moisture in the irrigated root zone for all three irrigation methods. For the two PRI treatments, total water uptake by plants was largely determined by the soil water in the irrigated root zone. Nevertheless, the non-irrigated root zone under APRI also contributed to part of the total crop water uptake, but the continuously non-irrigated root zone under FPRI gradually ceased to contribute to crop water uptake, suggesting that it is the APRI that can make use of all the root system for water uptake, resulting in higher water use efficiency.

Keywords: Crop water consumption, hydraulic conductivity in soil–root system (Lsr), partial root-zone irrigation, soil moisture, soil water uptake

Introduction

Partial root-zone irrigation (PRI) or partial root-zone drying (PRD), include alternate PRI (APRI) and fixed PRI (FPRI) and is a new water-saving irrigation technique developed recently (Kang and Zhang, 2004). In APRI, half of the root zone is irrigated while the other half is dried, and then the previously well-watered side of the root system is allowed to dry while the previously dried side is fully irrigated (Kang et al., 1997; Stoll et al., 2000). However, in FPRI, a fixed half of the root zone is always irrigated while the other half is always dried. So far PRI has already been investigated on vegetable crops such as tomato (Kirda et al., 2004), potato (Liu et al., 2006), hot pepper (Shao et al., 2008), and bean (Gencoglan et al., 2006), fruit trees such as grapevine (De La Hera et al., 2007), pear (Kang et al., 2002), and apple (Leib et al., 2005), and field crops such as maize (Kang et al., 2000; Hu et al., 2009) and cotton (Du et al., 2008). Earlier results demonstrated that PRI induces compensatory water absorption from the wetted zone (English and Raja, 1996), reduces transpiration, and maintains a higher level of photosynthesis compared with conventionally managed crops receiving twice as much water (Kirda et al., 2004; Zegbe et al., 2004). APRI could maintain high grain yield with almost 50% reduction in irrigation water, which resulted in higher water use efficency (WUE) (Kang et al., 2000). In addition, PRI also reduced excessive vegetative growth of crops (Dry and Loveys, 1998) and increased quality of fruit (Loveys et al., 2000).

Water movement to and from a root depends on the soil hydraulic conductivity, the distance across any root–soil air gap, and the hydraulic conductivity of the root. In an experiment for a 30-d period of soil drying, Nobel and Cui (1992) found that the predominant limiting factor for water movement was root hydraulic conductivity for the first 7 d, the root–soil air gap for the next 13 d, and then the soil hydraulic conductivity thereafter. Drought-induced changes in soil hydraulic conductivity were greater in absolute terms than changes in root hydraulic conductivity (Kang and Zhang, 1997).

In general, which one of these three conductivities is the limiting factor for water transport varies with soil water potential (Kang and Zhang, 1997; Draye et al., 2010). Under sufficiently wet conditions when root water extraction is at its maximum (potential) rate, water uptake partitioning over depth is highly correlated with root mass or length per unit volume of soil (Novák, 1987). Under drier conditions when hydraulic conditions limit root water uptake, water extraction has been reported to be proportional to root length density and soil water potential (Novák, 1987), and the actual transpiration/potential transpiration ratio decreased linearly with soil water content (Doorenbos and Kassam, 1986). When soil water potential is higher than –1.0 MPa, there is no apparent effect of temperature on root shrinkage, and hydraulic conductivity of the root–soil air gap increases by 0.44% and 0.59% per °C change in temperature for maize and sunflower, respectively, but when soil water potential is lower than –1.0 MPa, root shrinkage increases whereas the hydraulic conductivity of the root–soil air gap decreases with temperature (Kang and Zhang, 1997). In intermediate conditions, the spatial distribution and the magnitude of the uptake will depend on the spatial distribution of the ratio between root radial and soil conductivity and on xylem conductivity (Draye et al., 2010). Moreover, total root water uptake is strongly affected by the hydraulic conductivity drop from the bulk soil to the soil–root interface, especially under conditions where the radial root hydraulic conductivity is larger than the soil hydraulic conductivity (Shroder et al., 2008).

Additionally, soil water uptake by plant roots also depends on the complex interplay between plant and soil that modulates and determines transport processes at a range of spatial and temporal scales (Garrigues et al., 2006). The rhizosphere effect on water transport differs markedly from that of bulk soil. Under soil drying, rhizosphere properties can reduce water depletion around roots and weaken the drop in water potential towards roots, therefore favouring water uptake under dry conditions (Carminati et al., 2010). Hence, plant water uptake is determined by the hydraulic conductivity in the whole soil–root system.

PRI was originally developed as an irrigation technique to specifically manipulate root-to-shoot signalling to increase WUE. Despite many recent articles describing the impact of this technique (Dodd, 2007), there are only a few studies on water uptake and transport in plant (Dodd et al., 2008a, b; Lovisolo et al., 2002). Since previous work has measured whole-plant hydraulic conductance (Lovisolo et al., 2002) or the spatial distribution of transpirational water fluxes of plants exposed to FPRI (Dodd et al., 2008a, b), in this experiment, different PRIs, FPRI and APRI, were applied and compared with conventional irrigation (CI). This study investigated hydraulic conductivity in the soil–root system in different root zones and its contribution to plant water uptake under PRI, attempting to understand how water flow from soil to plants is affected by the different irrigation methods.

Materials and methods

Experimental material

The experiment was conducted in a greenhouse under natural light conditions in Northwest A & F University in northwest China, where no temperature-controlling equipment was available. The photon flux density ranged from 450 to 800 μmol m−2 s−1. The average day/night temperature was 27/18 °C and relative humidity ranged from 30% to 60%.

The experimental soil type is Earth–cumuli–Orthic Anthrosols (lou soil), a clay loam with moderately low permeability and moderate organic matter content. The loam soil had a soil pH of 7.87, an organic matter content of 15.55 g kg−1, total N content of 0.89 g kg−1, available N (i.e. hydrolytic N at 1 mol l−1 NaOH hydrolysis) of 50.5 mg kg−1, available P (0.5 mol l−1 NaHCO3) of 14.7 mg kg−1, and available K (1 mol l−1 neutral NH4OAc) of 140.5 mg kg−1 soil. Gravimetric (θ) and volumetric (θv) water content of this soil at field capacity were 26% (g g−1) and 33.8% (cm3 cm−3), respectively, and the bulk density when dry was 1.3 g cm−3. A moisture release curve for this soil (Fan et al., 2008) allowed measurements of θ to be converted to soil water potentials (Ψsoil) according to the van-Genuchten model, in which the saturated water content (θs) was 0.3643 g g−1, the residual water content (θr) was 0.0609 g g−1, parameters α, n, and m were 0.0348, 1.274, and 0.2151, respectively, and the goodness-of-fit of the van-Genuchten equation was indicated by r2=0.951.

Maize plants (Zea mays L. cv. Shanndan No. 9, a local variety) were grown in PVC perforated tubes (5.2 cm in diameter, 30 cm in height) filled with soil. A basal dressing of 0.435 g of urea and 0.125 g of KH2PO4 per kg soil was added. Each tube was evenly separated with plastic sheets into two sub-parts of equal volume, between which no water exchange occurred. Each sub-part was filled with 320 g of air-dried soil. In order to reduce bare soil evaporation and prevent soil surface hardening, a fine plastic perforated tube (6.7 mm in diameter) was vertically installed in each sub-part and used for irrigation. Each fine tube was wrapped with two layers of window mesh to help water dispersal. All tubes were irrigated up to field capacity before sowing. After the primary root was severed, one pre-germinated seed was placed at the middle of the tube so that the root was fairly evenly distributed into the two separated sub-parts.

Experimental design

Treatments were three irrigation methods, including CI (irrigated on both sub-parts of the tube in each watering), APRI (watering was alternately applied to the two sub-parts of the tube in consecutive watering every 10 d, i.e. the wet and dry sides were alternated at days 11, 21, and 31 of irrigation treatment) and FPRI (watering was fixed to one of the two sub-parts). CI was replicated 48 times and the two PRIs 64 times each.

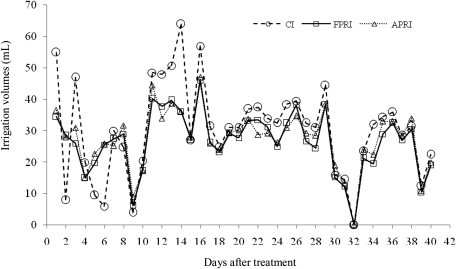

Irrigation treatment started 22 d after seedling emergence and the period of irrigation treatment lasted for 40 d. Soil water content was kept within the range 65–95% of field capacity. Weighing the tubes and irrigating with tap water every day or every 2 d controlled soil water regime for different irrigation methods during the experimental period. Because of different soil moisture change in the different root zones for the three irrigation methods, different upper weights were designed for the three irrigation treatments. The upper limit weight of CI, WCI,=pot weight+dry soil weight+the estimated weight of a plant+dry soil weight×0.26×0.95. For the two PRI treatments, the upper limit weight, WPRI,=pot weight+dry soil weight+ the estimated weight of a plant+dry soil weight×0.26×0.95×0.5+ dry soil weight×0.26×0.65×0.5. The estimated weight of a plant was obtained by weighing a plant of similar size. The amount of irrigation (Fig. 1) was calculated using the tube water balance. Irrigation water was applied through fine plastic perforated tubes.

Fig. 1.

Changes in amount of irrigation (ml) for three irrigation methods.

Measurements and methods

On days 5, 15, 25, and 35 of irrigation treatment, the hydraulic conductivity in the soil–root system (Lsr) was determined for the whole root and each sub-root using a pressure chamber (Model 3005, SMEC, 7.8 cm in diameter, 52 cm in height). On days 10, 20, 30, and40, Lsr was determined only for the irrigated root zone. Each measurement was replicated four times. In order to minimize the temperature and diurnal effects on the hydraulic conductivity, four replicates were sown and measured on different dates, and all treatments in the same replicate were measured on the same dates. Moreover, before each plant was used, it was removed from the greenhouse and allowed to equilibrate overnight in the laboratory maintained at the temperature (25±0.25 °C) at which the determinations were carried out. All measurements were carried out during 7:00–11:00 a.m. Afterwards, each sub-root was sampled and used for the measurement of root length and root area. Soil samples from each sub-part of the PVC tube were taken and soil water content determined.

Lsr

To measure Lsr for the whole root system, the shoot was cut off and the root system and its container sealed into the pressure chamber, and the cut stem was projected through a seal in the lid of the chamber. Pressure was applied until root water potential was reached, and then a series of pressures applied to determine volume flows. The relationship between the flow rate and the applied pressure was then used to determine the value of Lsr, in the manner previously described by Kang and Zhang (1997).

For one sub-root, the other sub-root was cut from the plant and a half soil column of the same volume was bound to it, then Lsr was determined as described above. The hydraulic conductivity per root area and per root length was calculated from Lsr and total root area or root length.

Root length and area

Sub-root samples were scanned for root length and area with a CI-400 computer image analysis system (CID Ltd, USA). The obtained root length/dried mass and root area/dried mass ratios were used to calculate the total root length and area, respectively, for all harvested root samples.

Soil water content

For the measurement of gravimetric soil water content (θ), soil samples were oven dried at 105 °C to constant dry weight.

Crop water consumption

Because there was no drainage from the tubes in the experiment under controlled condition, the amount of crop water consumption (ET) (Fig. 2) was calculated from the tube water balance using the following equation:

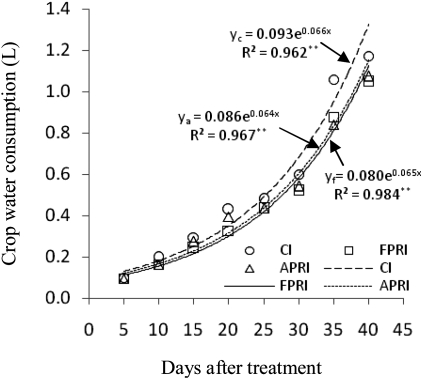

Fig. 2.

Changes in crop water consumption (l) for three irrigation methods. **Significant difference at 0.01 probability levels (r0.01,6=0.834).

ET (l)=primary soil water +irrigation water–final soil water.

As shown in Fig. 2, crop water consumption increased quickly with time for all three irrigation methods, which fitted the exponential equation well.

Data analysis

Using SPSS software, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted and multiple comparisons of means were performed using Tukey's HSD test at a significance level of P=0.05. Correlation and regression analysis were conducted using Microsoft Excel 2007.

Results

Relationship between crop water consumption and Lsr in different root zones

Coefficients of correlation between the amount of crop water consumption and Lsr in different root zones of maize are shown in Table 1. Crop water consumption was significantly correlated with Lsr in the whole root zone for all three irrigation methods. As for Lsr in a half root zone, the correlation coefficient of the non-irrigated root zone in FPRI was low while that of APRI was close to the significance level at the probability of 95%. As expected, the coefficient of the irrigated root zone was markedly greater than the significance level at a probability of 99% for all three irrigation methods, suggesting that the Lsr in both the whole and irrigated root zones can reflect water uptake by plants well under conventional and partial root-zone irrigation.

Table 1.

Correlation coefficients between crop water consumption and Lsr in different root zones of maize

| Lsr | df | Correlation coefficients (r) |

| Lsr in the whole root zone under CI | 2 | 0.996** |

| Lsr in Ch under CI | 6 | 0.976** |

| Lsr in the whole root zone under FPRI | 2 | 0.997** |

| Lsr in Fw under FPRI | 6 | 0.987** |

| Lsr in Fd under FPRI | 2 | 0.204 |

| Lsr in the whole root zone under APRI | 2 | 0.989* |

| Lsr in Aw under APRI | 6 | 0.979** |

| Lsr in Ad under APRI | 2 | 0.911 |

Root zone abbreviations: Ch, a half root zone of CI; Fd and Fw indicate the non-irrigated (dry) and irrigated (wet) half root zones of FPRI, respectively; Ad and Aw indicate the non-irrigated (dry) and irrigated (wet) half root zones of APRI, respectively.

*and** represent significant difference at 0.05 and 0.01 probability levels, respectively (r0.05,2=0.950, r0.01,2=0.990; r0.05,6=0.707, r0.01,6=0.834).

Lsr in different root zones under three irrigation methods

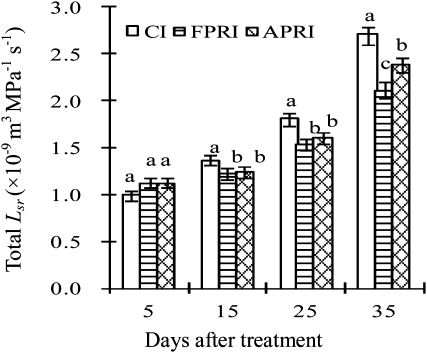

As shown in Fig. 3, no significant difference was found in Lsr in the whole root zone between the three irrigation methods at 5 d after treatment (DAT). The Lsr in the whole root zone of CI increased significantly when compared with those of PRIs at 15 and 25 DAT. At 35 DAT, the Lsr in the whole root zone of APRI was markedly greater than that of FPRI, but lower than that of CI.

Fig. 3.

Lsr in the whole root zone. Vertical bars represent one standard error of the mean. Different letters indicate significant difference between different irrigation methods at the same time (P<0.05).

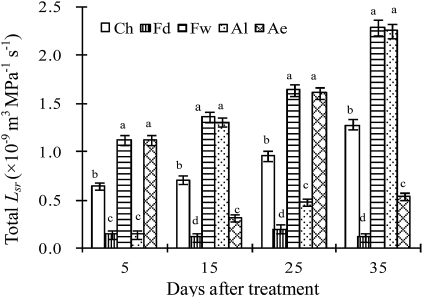

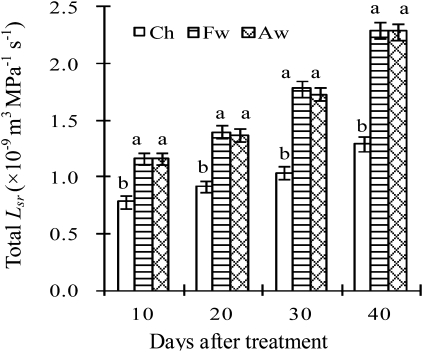

Figure 4 shows that the Lsr in the non-irrigated root zone of PRIs dropped significantly when compared with that in a half root zone of CI, while the Lsr in the irrigated root zone of PRIs increased by 68.7–92.0% at 5, 15, 25, and 35 DAT. Moreover, the Lsr in the irrigated root zone of PRIs increased by 49.0–78.1% at 10, 20, 30, and 40 DAT (Fig. 5), suggesting that PRIs have an obvious compensatory effect on root water uptake.

Fig. 4.

Lsr in half root zone. Root-zone abbreviations: Ch, a half root zone of CI; Fd and Fw indicate the non-irrigated (dry) and irrigated (wet) half root zones of FPRI, respectively; Ae and Al indicate the early and late irrigated half root zones of APRI, respectively, i.e. Ae was wet and Al was dry during the first 10 d of irrigation treatment, and they were alternated at the beginning of the 11th day, and so on. Vertical bars represent one standard error of the mean. Different letters indicate significant difference between different root zones of three irrigation methods at the same time (P<0.05).

Fig. 5.

Lsr in the irrigated root zone. Root-zone abbreviations: Ch, a half root zone of CI; Fw, the irrigated (wet) half root zones of FPRI; Aw, the irrigated (wet) half root zones of APRI. Vertical bars represent one standard error of the mean. Different letters indicate significant difference between the three irrigation methods at the same time (P<0.05).

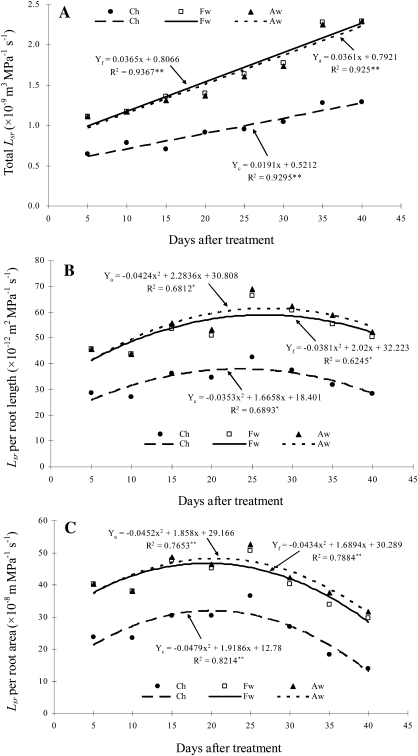

Interestingly, for all three irrigation methods, total Lsr in the irrigated root zone increased linearly with time (Fig. 6A), while the relationship between Lsr per root length or per root area in the irrigated root zone and time can be estimated with a second-degree parabola (Fig. 6B, C).

Fig. 6.

Relationship between Lsr in the irrigated root zone and time. Root-zone abbreviations: Ch, a half root zone of CI; Fw indicate the irrigated (wet) half root zones of FPRI; Aw, the irrigated (wet) half root zones of APRI. *and** represent significant difference at 0.05 and 0.01 probability levels, respectively (r0.05,6=0.707, r0.01, 6=0.834).

In addition, Fig. 4 also shows that there was significant variation in Lsr between two root zones with respect to the same irrigation methods. As expected, the Lsr in the irrigated root zone was consistently greater than that in the non-irrigated root zone in FPRI at 5, 15, 25, and 35 DAT. In APRI, the Lsr in two root zones alternately varied but Lsr in the irrigated root zone was consistently greater than that in the non-irrigated root zone. The difference in Lsr between two root zones of APRI was significantly lower than that of FPRI. Moreover, the Lsr in the non-irrigated root zone of APRI increased significantly when compared with that of FPRI, indicating that soil moisture content can significantly influence Lsr.

Relative importance of Lsr in different root zones

The proportion of Lsr in a half root zone to Lsr in the whole root zone is shown in Table 2. The contribution of Lsr in a half root zone to Lsr in the whole root zone was ∼50% for CI at 5, 15, 25, and 35 DAT. For Lsr in the irrigated root zone of FPRI, it was close to 100% and greater than that of the non-irrigated root zone and that of a half root zone of CI. While in APRI, the proportions of the two root zones varied alternately but that of the irrigated root zone was consistently greater than that of the non-irrigated root zone and that of a half root zone of CI. With respect to the non-irrigated root zone, the proportion of APRI increased greatly when compared with that of FPRI, indicating that compared with APRI and CI, FPRI could not efficiently make use of all root parts for crop water uptake.

Table 2.

The proportion of Lsr in a half root zone to Lsr in the whole root zone (%)

| Days after treatment | CI | FPRI |

APRI |

||

| Ch | Fd | Fw | Al | Ae | |

| 5 | 56.88±1.23b | 11.66±0.33c | 89.57±1.08a | 11.66±0.33c | 89.57±1.08a |

| 15 | 51.56±0.63c | 8.60±0.23e | 99.65±1.68a | 86.03±1.26b | 20.75±1.08d |

| 25 | 52.71±0.77c | 11.76±0.31e | 96.33±1.29a | 24.60±1.32d | 82.48±1.12b |

| 35 | 47.19±1.09c | 4.87±0.21e | 97.05±1.21a | 84.86±1.11b | 20.38±1.18d |

Root-zone abbreviations: Ch, a half root zone of CI; Fd and Fw indicate the non-irrigated (dry) and irrigated (wet) half root zones of FPRI, respectively; Ae and Al indicate the early and late irrigated half root zones of APRI, respectively. Values are means ±SE.

Different letters in the same row indicate significant difference (P<0.05).

Effect of soil moisture in different root zones on Lsr

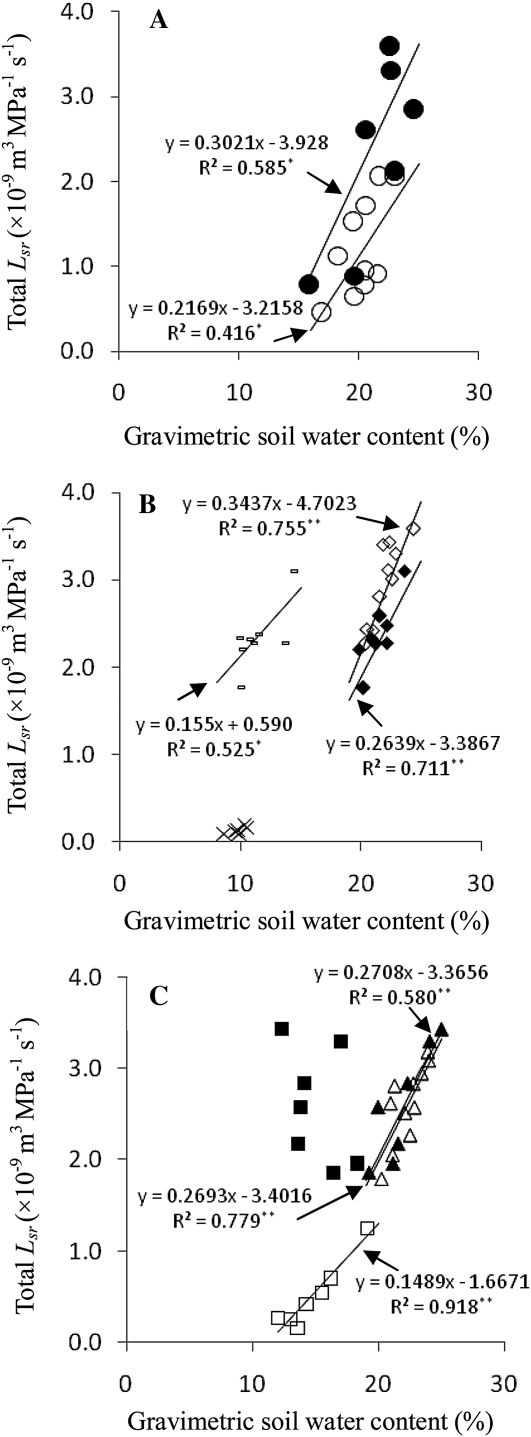

As shown in Fig. 7, the slopes of linear regression equations between Lsr and gravimetric soil water content (θ, see Fig. 8) in different root zones varied with irrigation methods. With respect to θ in the same half root zone for CI, the slope between θ and Lsr in the whole root zone increased by 39.3% compared with that between θ and Lsr in a half root zone (Fig. 7A). With the same Lsr in the whole root zone of FPRI, the slope between Lsr and θ in the irrigated root zone was greater than that between Lsr and θ in the non-irrigated root zone. As for θ in the same irrigated root zone of FPRI, the slope between θ and Lsr in the irrigated root zone was greater than that between θ and Lsr in the whole root zone (Fig. 7B), indicating that the non-irrigated root zone decreased water transport in the soil–root system under FPRI. APRI was different from FPRI (Fig. 7C). θ in the non-irrigated root zone was significantly correlated with Lsr in the non-irrigated root zone but not with Lsr in the whole root zone. The regression equation between θ in the irrigated root zone and Lsr in the whole root zone was almost the same as that between θ and Lsr in the irrigated root zone, suggesting that water uptake under APRI was determined by soil water content in the irrigated root zone but not the non-irrigated root zone, although part of the water flow was from the non-irrigated root zone to plants.

Fig. 7.

Relationship between Lsr (Y) and gravimetric soil water content (θ) in different root zones (X). In (A), for CI, Lsr in the whole root zone versus θ in a half root zone (closed circles) and Lsr versus θ in a half root zone (open circles) is indicated. In (B), for FPRI, Lsr in the whole root zone versus θ in the irrigated root zone (closed diamonds); Lsr in the whole root zone versus θ in the non-irrigated root zone (hyphens); Lsr versus θ in the irrigated root zone (open diamonds); Lsr versus θ in the non-irrigated root zone (crosses). In (C), for APRI, Lsr in the whole root zone versus θ in the irrigated root zone (closed triangles); Lsr in the whole root zone versus θ in the non-irrigated root zone (closed squares); Lsr versus θ in the irrigated root zone (open triangles); Lsr versus θ in the non-irrigated root zone (open squares). *and** indicate significant difference at 0.05 and 0.01 probability levels, respectively (r0.05,4=0.811, r0.01,4=0.917; r0.05,5=0.754, r0.01,5=0.874; r0.05,6=0.707, r0.01,6=0.834; r0.05,8=0.632, r0.01,8=0.765; r0.05,9=0.602, r0.01,9=0.735).

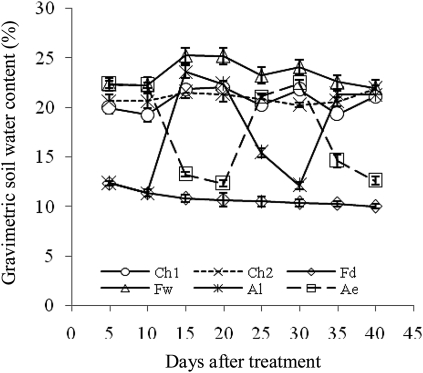

Fig. 8.

Changes in gravimetric soil water content in different root zones of three irrigation methods. Root zone abbreviations: Ch1 and Ch2 indicate two half root zones of CI, respectively; Fd and Fw indicate the non-irrigated (dry) and irrigated (wet) half root zones of FPRI, respectively; Ae and Al indicate the early and late irrigated half root zones of APRI, respectively. Vertical bars represent one standard error of the mean.

Similar results were achieved when examining the effect of different irrigation treatments on the relationship between Lsr and soil water potential in different root zones of maize (Table 3).

Table 3.

Linear regression equations between Lsr (Y) and soil water potential (Ψ, 0.1 MPa) in different root zones (X)

| Treatment | Dependent variable (Y) | Independent variable (X) | Equation | df | Determination coefficient (r2) |

| CI | Lsr in the whole root zone | Ψ in Ch | Y=3.109–1.474X | 5 | 0.588* |

| Lsr in Ch | Ψ in Ch | Y=1.902–1.267X | 8 | 0.409* | |

| FPRI | Lsr in the whole root zone | Ψ in Fw | Y=3.416–3.046X | 6 | 0.619* |

| Lsr in the whole root zone | Ψ in Fd | Y=1.117–0.008X | 6 | 0.367 | |

| Lsr in Fw | Ψ in Fw | Y=4.540–5.213X | 8 | 0.829** | |

| Lsr in Fd | Ψ in Fd | Y=0.160–0.0004X | 4 | 0.397 | |

| APRI | Lsr in the whole root zone | Ψ in Aw | Y=3.675–3.284X | 5 | 0.643* |

| Lsr in the whole root zone | Ψ in Ad | No relation | |||

| Lsr in Aw | Ψ in Aw | Y=3.719–3.999X | 9 | 0.610** | |

| Lsr in Ad | Ψ in Ad | Y=0.824–0.075X | 5 | 0.481 |

Root-zone abbreviations: Ch, a half root zone of CI; Fd and Fw indicate the non-irrigated (dry) and irrigated (wet) half root zones of FPRI, respectively; Ad and Aw indicate the non-irrigated (dry) and irrigated (wet) half root zones of APRI, respectively.

*and** indicate significant difference at 0.05 and 0.01 probability levels, respectively (r0.05,4=0.811, r0.01,4=0.917; r0.05,5=0.754, r0.01,5=0.874; r0.05,6=0.707, r0.01,6=0.834; r0.05,8=0.632, r0.01,8=0.765; r0.05,9=0.602, r0.01,9=0.735).

Crop water uptake and use under three irrigation methods

As shown in Table 4, there were significant differences in biomass, crop water consumption, and WUE between the three irrigation methods. Total crop water consumption in FPRI and APRI treatments was significantly lower than under CI treatment. Compared with CI, FPRI and APRI increased WUE by 11.31% and 7.34%, respectively. FPRI decreased shoot biomass while APRI maintained it. Moreover, root biomass of APRI was higher than that of both CI and FPRI plants.

Table 4.

WUE at the end of the experiment

| Treatment | Shoot dry mass (g pot−1) | Root mass (g pot−1) | Crop water consumption (l pot−1) | WUE (g l−1) |

| CI | 4.91±0.18a | 1.28±0.07b | 1.172±0.036a | 5.28±0.24b |

| FPRI | 4.60±0.13b | 1.33±0.09b | 1.047±0.025b | 5.67±0.30a |

| APRI | 4.86±0.15a | 1.46±0.11a | 1.075±0.028b | 5.88±0.29a |

Values are means ±SE. Different letters indicate significant difference between different irrigation methods (P<0.05).

Discussion

The results reported here show that there is a significant and substantial compensatory effect of water uptake under partial root zone irrigation. This indicates that dynamic changes in water uptake can occur in different parts of the root zone when water distribution also changes unevenly and dynamically. Many studies have shown that plants can compensate for water stress in one part of the root zone by taking up water from other parts of the root zone where water is available (English and Raja, 1996; Leib et al., 2005). This might reflect plant acclimation to heterogeneous water distribution in soil. On one hand, root system tends to proliferate largely in the region of highly efficient water and to optimize allocation and utilization of plant resources in order to capture the maximum necessities of water and nutrients (Ben-Asher and Silberbush, 1992; Gallardo et al., 1994; Hu et al., 2008). On the other hand, ABA can be induced by partial root drying as a drought signal (Stoll et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2006; Dodd et al., 2008a) and regulate the activity of aquaporins and increase root hydraulic conductivity (Zhang et al., 1995; Hose and Hartung, 1999). Steudle (2000) speculated that aquaporins might reversibly regulate root hydraulic conductivity as a valve and increase plant water uptake in adverse conditions.

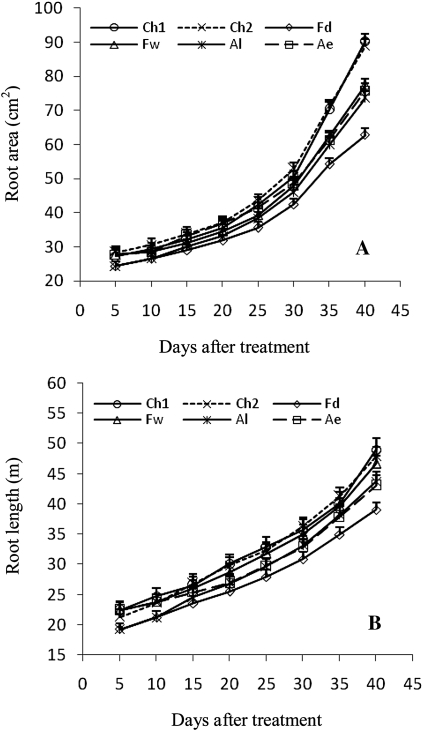

The results reported here also reveal that the non-irrigated root zone plays a minor role in water uptake and transport in the whole soil–plant system under FPRI. This is consistent with studies of Dodd et al. (2008a, b) that partitioned whole plant transpirational water fluxes of FPRI plants into components from wet and dry parts of the root zone, by measuring sap fluxes from each. The half of the roots in permanently dry soil under FPRI might be subjected to severe drought, causing anatomy change of plant roots, and resistance to water uptake and transport to increase, thus decreasing root hydraulic conductivity (Perumalla and Peterson, 1986; Schreiber et al., 1999). Root length and area decreased markedly compared with those of the root system in other root zones (Fig. 9). In addition, soil moisture was very low (Fig. 8), thus soil hydraulic conductivity decreased greatly (Yang and Shao, 2000). Moreover, severe drought enhances root shrinkage and thus decreases the hydraulic conductivity in the soil–root interface gap, resulting in lower hydraulic conductivity of the whole soil–root system (Taylor and Willatt, 1983; North and Nobel, 1991; Kang and Zhang, 1997), which is confirmed by the results reported here.

Fig. 9.

Changes in root area (A) and length (B) in different root zones of the three irrigation methods. Root zone abbreviations: Ch1 and Ch2 indicate two half root zones of CI, respectively; Fd and Fw indicate the non-irrigated (dry) and irrigated (wet) half root zones of FPRI, respectively; Ae and Al indicate the early and late irrigated half root zones of APRI, respectively. Vertical bars represent one standard error of the mean.

Lsr and its relative importance in different root zones varied differently with respect to irrigation methods (Tables 2, 3, Figs 3, 4, 5, 7). This is obviously related to the effect of soil moisture heterogeneity, which is manipulated by different irrigation methods, on the components of Lsr. For both root zones of CI, soil water potential was close to –0.03 MPa. The components of Lsr, including soil hydraulic conductivity, the hydraulic conductivity in the soil–root interface gap, and the hydraulic conductivity of the root, all contributed greatly to crop water uptake (Novák, 1987; Kang and Zhang, 1997; Draye et al., 2010). For the irrigated root zone of FPRI and APRI, the condition was similar to CI. For the non-irrigated root zone of FPRI, the soil water potential was largely lower than –1.0 MPa. The non-irrigated root zone played a minor role in water uptake and transport in the whole soil–plant system under FPRI, as stated above (also see Dodd et al., 2008a, b). As for the non-irrigated root zone of APRI, the condition was different. The soil water potential was close to –1.0 MPa. During the early period after irrigation stopped, Lsr was almost maintained. During the later period, the components of Lsr were still greater than those of FPRI though all largely decreased, which remains to be determined further.

Under FPRI, the non-irrigated root zone had reduced water transport in the whole soil-plant system, but Lsr in the whole root zone was significantly correlated with soil water content in the non-irrigated root zone (Fig. 7B). Such a phenomenon should be due to water efflux from plant roots induced by water potential difference between the two root zones (Caldwell and Richards, 1989; Xu and Bland, 1993; Faria et al., 2010). Xu and Bland (1993) indicated that reverse water flow in sorghum roots occurred with a water potential difference of 0.55 MPa between dry topsoil and wet subsoil. In FPRI, the irrigated root zone was continuously watered while the non-irrigated root zone was permanently left dry, resulting in an obvious difference in soil moisture between them. For instance, the soil water content in the non-irrigated root zone was ∼9.1–10.3% while it was ∼23.1–25.6% in the irrigated root zone at 10 DAT. With the reverse water flow in plant roots, the water in the irrigated root zone might enter the non-irrigated root zone, thus soil moisture changed synchronously in the two root zones. Apparently this needs further investigation.

The results reported here also show that total water uptake increased with time but the water uptake capacity per root system had a peak at ∼20 DAT (Fig. 6). This was confirmed by similar data sets of root system hydraulic conductivity (Lp) and total root system hydraulic conductance (LR) of Fiscus and Markhart (1979). This might result from root morphological and physiological changes with time. In this study, maize plant was just in the jointing stage (∼20 DAT). Roots proliferated greatly and root length and area increased quickly during the experimental period (Fig. 9). The early period increase in water uptake capacity per root system was caused by the rapid proliferation of new secondary and tertiary roots, which were more highly conductive (Fiscus and Markhart, 1979). While part of the roots aged with time, root surfaces suberized and the membrane permeability dropped, thus the total resistance of roots to water uptake and transport increased (Fiscus and Markhart, 1979; Fusseder, 1987; Maurel et al., 2010), thus resulting in a gradual decrease in water uptake capacity per root system. Total water uptake continuously increased with time, which was due to concurrent increases in root system hydraulic conductivity and root area (Fiscus and Markhart, 1979).

Conclusions

For all three irrigation methods, Lsr in both the whole and irrigated root zones is related to water uptake by plants. Moreover, Lsr in either the whole or the irrigated root zones is linearly correlated with soil water content and matrix potential in the irrigated root zone. PRI treatments led to a significant compensatory effect on water uptake in the irrigated root zone although they had a reduced total water uptake and consumption (Fig. 2, Table 4) when compared with CI. Lsr and its relative importance in different root zones varied differently with respect to irrigation methods. For the two PRIs, total water uptake by plants was largely determined by the soil water moisture and Lsr in the irrigated root zone. Nevertheless, the non-irrigated root zone under APRI also contributed to crop water uptake but the continuously non-irrigated root zone under FPRI played a minor role in water uptake, suggesting that it is APRI that can make best use of all the root system to take up water from soil, resulting in higher WUE (Table 4).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for research grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51079124, 50939005, and 50869001), the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (2010AA10A302), Hong Kong University Grants Committee (AoE/B-07/99), and Hong Kong Research Grants Council (HKBU 262307).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- APRI

alternate partial root-zone irrigation

- CI

conventional irrigation

- Lsr

hydraulic conductivity in the soil–root system

- FPRI

fixed partial root-zone irrigation

- PRD

partial root-zone drying

- PRI

partial root-zone irrigation

- WUE

water use efficiency

References

- Ben-Asher J, Silberbush M. Root distribution under trickle irrigation: factors affecting distribution and comparison among methods of determination. Journal of Plant Nutrition. 1992;15:783–794. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell MM, Richards JH. Hydraulic lift: water efflux from upper roots improve effectiveness of water uptake by deep roots. Oecologia. 1989;79:1–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00378231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carminati A, Moradi AB, Vetterlein D, Vontobel P, Lehmann E, Weller U, Vogel HJ, Oswald SE. Dynamics of soil water content in the rhizosphere. Plant and Soil. 2010;332:163–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Hera ML, Romero P, Gomez-Plaza E, Martinez A. Is partial root-zone drying an effective irrigation technique to improve water use efficiency and fruit quality in field-grown wine grapes under semiarid conditions? Agricultural Water Management. 2007;87:261–274. [Google Scholar]

- Dodd IC. Soil moisture heterogeneity during deficit irrigation alters root-to-shoot signalling of abscisic acid. Functional Plant Biology. 2007;34:439–448. doi: 10.1071/FP07009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd IC, Egea G, Davies WJ. Accounting for sap flow from different parts of the root system improves the prediction of xylem ABA concentration in plants grown with heterogeneous soil moisture. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2008a;59:4083–4093. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd IC, Egea G, Davies WJ. Abscisic acid signalling when soil moisture is heterogeneous: decreased photoperiod sap flow from drying roots limits abscisic acid export to the shoots. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2008b;31:1263–1274. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2008.01831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doorenbos J, Kassam AH. Yield response to water. FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper 33. 1986. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, Rome. [Google Scholar]

- Draye X, Kim Y, Lobet G, Javaux M. Model-assisted integration of physiological and environmental constraints affecting the dynamic and spatial patterns of root water uptake from soils. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2010;61:2145–2155. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dry PR, Loveys BR. Factors influencing grapevine vigour and the potential for control with partial root zone drying. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research. 1998;4:140–148. [Google Scholar]

- Du T, Kang S, Zhang J, Li F. Water use and yield responses of cotton to alternate partial root-zone drip irrigation in the arid area of north-west China. Irrigation Science. 2008;26:147–159. [Google Scholar]

- English M, Raja SN. Perspectives on deficit irrigation. Agricultural Water Management. 1996;32:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Fan YW, Deng Y, Wang BL. Comparative study on calculation of parameters in van-Genuchten model of soil moisture release curve. Yellow River. 2008;30:49–50. [Google Scholar]

- Faria LN, Da Rocha MG, Van Lier QDJ, Casaroli D. A split-pot experiment with sorghum to test a root water uptake partitioning model. Plant and Soil. 2010;331:299–311. [Google Scholar]

- Fiscus EL, Markhart AH. Relationships between root system water transport properties and plant size in Phaseolus. Plant Physiology. 1979;64:770–773. doi: 10.1104/pp.64.5.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusseder A. The longevity and activity of the primary root of maize. Plant and Soil. 1987;101:257–265. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo M, Turner NC, Ludwig C. Water relations, gas exchange and abscisic acid content of Lupinus cosentinii leaves in response to drying different proportions of the root system. Journal of Experimental Botany. 1994;45:909–918. [Google Scholar]

- Garrigues E, Doussan C, Pierret A. Water uptake by plant roots: I - formation and propagation of a water extraction front in mature root systems as evidenced by 2D light transmission imaging. Plant and Soil. 2006;283:83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Gencoglan C, Altunbey H, Gencoglan S. Response of green bean (P. vulgaris L.) to subsurface drip irrigation and partial rootzone-drying irrigation. Agricultural Water Management. 2006;84:274–280. [Google Scholar]

- Hose E, Hartung W. The effect of abscisic acid on water transport through maize roots. Journal of Experimental Botany. 1999;50(Suppl):40–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hu T, Kang S, Li F, Zhang J. Effects of partial root-zone irrigation on the nitrogen absorption and utilization of maize. Agricultural Water Management. 2009;96:208–214. [Google Scholar]

- Hu T, Kang S, Yuan L, Zhang F, Li Z. Effects of partial root-zone irrigation on growth and development of maize root system. Acta Ecologica Sinica. 2008;28:6180–6188. [Google Scholar]

- Kang S, Hu X, Li Z, Jerie P. Soil water distribution, water use and yield response to partial rootzone drying under shallow groundwater conditions in a pear orchard. Scientia Horticulturae. 2002;92:277–291. [Google Scholar]

- Kang S, Liang Z, Pan Y, Shi P, Zhang J. Alternate furrow irrigation for maize production in an arid area. Agricultural Water Management. 2000;45:267–274. [Google Scholar]

- Kang S, Zhang J. Hydraulic conductivities in soil-root system and relative importance at different soil water potential and temperature. Transaction of CSAE. 1997;13:76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kang S, Zhang J. Controlled alternate partial rootzone irrigation: its physiological consequences and impact on water use efficiency. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2004;55:2437–2446. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S, Zhang J, Liang Z, Hu X, Cai H. The controlled alternative irrigation: a new approach for water saving regulation in farmland. Agricultural Research in the Arid Areas. 1997;15:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kirda C, Cetin M, Dasgan Y, Topcu S, Kaman H, Ekici B, Derici MR, Ozguven AI. Yield response of greenhouse grown tomato to partial root drying and conventional deficit irrigation. Agricultural Water Management. 2004;69:191–201. [Google Scholar]

- Leib BG, Caspari HW, Redulla CA, Andrews PK Jabro JJ. Partial rootzone drying and deficit irrigation of ‘Fuji’ apples in a semi-arid climate. Irrigation Science. 2005;24:85–99. [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Shahnazari A, Andersen MN, Jacobsen SE Jensen CR. Effects of deficit irrigation (DI) and partial root drying (PRD) on gas exchange, biomass partitioning, and water use efficiency in potato. Scientia Horticulturae. 2006;109:113–117. [Google Scholar]

- Loveys BR, Stoll M, Dry PR, McCarthy MG. Using plant physiology to improve the water use efficiency of horticultural crops. Acta Horticulturae. 2000;537:187–197. [Google Scholar]

- Lovisolo C, Hartung W, Schubert A. Whole-plant hydraulic conductance and root-to-shoot flow of abscisic acid are independently affected by water stress in grapevines. Functional Plant Biology. 2002;29:1349–1356. doi: 10.1071/FP02079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurel C, Simonneau T, Sutka M. The significance of roots as hydraulic rheostats. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2010;61:3191–3198. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobel PS, Cui MY. Hydraulic conductances of the soil, the root soil air gap, and the root - changes for desert succulents in drying soil. Journal of Experimental Botany. 1992;43:319–326. [Google Scholar]

- North GB, Nobel PS. Changes in hydraulic conductivity and anatomy caused by drying and rewetting roots of Agave deserti (Agavaceae) American Journal of Botany. 1991;78:906–915. [Google Scholar]

- Novák V. Estimation of soil-water extraction patterns by roots. Agricultural Water Management. 1987;12:271–278. [Google Scholar]

- Perumalla CJ, Peterson CA. Deposition of casparian bands and suberin lamellae in the exodermis and endodermis of young corn and onion roots. Canadian Journal of Botany/Revue Canadienne de botanique. 1986;64:1873–1878. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber L, Hartmann K, Skrabs M, Zeier J. Apoplastic barriers in roots: chemical composition of endodermal and hypodermal cell walls. Journal of Experimental Botany. 1999;50:1267–1280. [Google Scholar]

- Shao GC, Zhang ZY, Liu N, Yu SE, Xing WG. Comparative effects of deficit irrigation (DI) and partial rootzone drying (PRD) on soil water distribution, water use, growth and yield in greenhouse grown hot pepper. Scientia Horticulturae. 2008;119:11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Shroder T, Javaux M, Vanderborght J, Korfgen B, Vereecken H. Effect of local soil hydraulic conductivity drop using a three-dimensional root water uptake model. Vadose Zone Journal. 2008;7:1089–1098. [Google Scholar]

- Steudle E. Water uptake by roots: effects of water deficit. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2000;51:1531–1542. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/51.350.1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll M, Loveys B, Dry P. Improving water use efficiency of irrigated horticultural crops. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2000;51:1627–1634. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/51.350.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor HM, Willatt ST. Shrinkage of soybean roots. Agronomy Journal. 1983;75:818–820. [Google Scholar]

- Wakrim R, Wahbi S, Tahi H, Aganchich B, Serraj R. Comparative effects of partial root drying (PRD) and regulated deficit irrigation (RDI) on water relations and water use efficiency in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Scientia Horticulturae. 2005;109:113–117. [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Bland WL. Reverse water-flow in sorghum roots. Agronomy Journal. 1993;85:697–702. [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Shao M. Study on soil water in Loess Plateau. 2000. Science Press, Beijing. [Google Scholar]

- Zegbe JA, Behboudian MH, Clothier BE. Partial root zone drying is a feasible option for irrigating processing tomatoes. Agricultural Water Management. 2004;68:195–206. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Zhang X, Liang J. Exudation rate and hydraulic conductivity of maize roots are enhanced by soil drying and abscisic acid treatment. New Phytologist. 1995;131:329–336. [Google Scholar]