Abstract

Aim:

To compare the efficacy and safety of rapid acting insulin analog lispro given subcutaneously with that of standard low-dose intravenous regular insulin infusion protocolin patients with mild to moderate diabetic ketoacidosis.

Materials and Methods:

In this prospective, randomized and open trial, 50 consecutive patients of mild to moderate diabetic ketoacidosis were randomly assigned to two groups. The patients in group 1 were treated with intravenous regular insulin infusion and admitted in intensive care unit. The patients in group 2 were treated with subcutaneous insulin lispro 2 hourly and managed in the emergency medical ward. Response to therapy was assessed by duration of treatment and amount of insulin administered until resolution of hyperglycemia and ketoacidosis, total length of hospital stay, and number of hypoglycemic events in the two study groups.

Results:

The baseline clinical and biochemical parameters were similar between the two groups. There were no differences in the mean duration of treatment and amount of insulin required for correction of hyperglycemia and ketoacidosis. There was no mortality and no difference in the length of hospital stay between the two groups. The length of stay and amount of insulin required for correction of hyperglycemia was greater in patients who had infection as the precipitating cause than those with poor compliance. The hypoglycemic events were higher in the regular insulin group (2 vs1) than in the lispro group.

Conclusion:

Patients with uncomplicated diabetic ketoacidosis can be managed in the medical wards with appropriate supervision and careful monitoring. Rapid acting insulin analog lispro is a safe and effective alternative to intravenous regular insulin for this subset of patients.

Keywords: Diabetic ketoacidosis, hyperglycemic crises, insulin analog

Introduction

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is an important hyperglycemic emergency in patients with diabetes mellitus characterized by the biochemical triad of uncontrolled hyperglycemia, metabolic acidosis, and increased ketones. This serious metabolic derangement results from combination of absolute or relative insulin deficiency and an increase in counterregulatory hormones (glucagon, catecholamine's, cortisol, and growth hormone). It is a major cause of morbidity and repeated hospitalization. It also accounts for nearby half of all deaths in patients with type 1 diabetes up to 24 years of age.[1,2]

Most patients with DKA have type 1 diabetes mellitus; however, patients with type 2 diabetes are also at an increased risk of DKA during catabolic stress of acute infections, surgery, and trauma.[3] There are studies to support that hospitalizations for DKA have increased in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in recent times[4–7] that may be related to increased incidence of type 2 diabetes.

Improved understanding of pathophysiology of DKA with close monitoring and correction of electrolytes has resulted in significant reduction in morbidity and mortality from this life-threatening condition. Several guidelines are currently available for the management of DKA in both adults and children.[8–10] The mainstay in treatment of patients of DKA involves administration of low doses of regular insulin by continuous intravenous infusion or by frequent intramuscular or subcutaneous injections of regular insulinor rapid acting insulin analogs.[11] Although many reports have shown that low dose insulin therapy is effective regardless of the route of administration, it is preferable to give continuous intravenous infusion of regular insulin until resolution of ketoacidosis because of potential delay in onset of action and longer half-life of subcutaneously given regular insulin.[12,13]

Many patients with DKA may require admission to intensive care unit either because of severity of ketoacidosis or due to coexisting serious illness. However, in certain institutions, patients are admitted in intensive care units even if they have mild to moderate ketoacidosis for administration of intravenous insulin infusion either due to hospital regulations or because of unavailability of infusion pumps in the general medical wards. In this context the treatment of uncomplicated DKA with subcutaneous rapid acting insulin analog has shown promise as an effective alternative to the use of regular insulin.[14] Mazer et al.[15] have reviewed this issue based on several studies[16–20] and concluded that treatment of patients with mild to moderate DKA with subcutaneous rapid acting insulin analogs (lispro and aspart) given hourly or 2 hourly in non-intensive care settings is as effective and safe as the treatment with continuous intravenous regular insulin in the intensive care unit. They also suggested that that use of insulin analogs may confer an overall cost saving, obviating the need for infusion pumps and admission in intensive care unit in certain institutions.

Being a teaching hospital, we have limited intensive care facilities, nursing staff, and financially poor patient population. Therefore, we aimed to compare the efficacy of insulin lispro subcutaneous 2 hourly in patients of mild to moderate DKA with standard intravenous regular insulin. We planned this study considering the paucity of work and subsequent observations of the outcomes using newer insulin in our patients of DKA.

Materials and Methods

We included 50 patients in our study who were admitted in emergency department of Era Medical College Hospital and were diagnosed to have mild to moderate DKA[21] from January 2009 to June 2010. We excluded those patients who had severe DKA and required admission in intensive care unit, those with loss of consciousness, acute myocardial ischemia, congestive cardiac failure, end-stage renal disease, anasarca, pregnancy, serious co-morbidities, and persistent hypotension even after the infusion of 1 L of normal saline. The study patients were randomized in emergency department following a computer generated randomization table in two groups. Group 1 comprised of patients who had to receive regular intravenous insulin infusion and were admitted in ICU while group 2 patients received subcutaneous insulin lispro at 2 hourly intervals. They were managed in an emergency medical ward itself. The study was conducted with the help of resident doctors and nursing staff who were given assigned treatment protocols [Table 1] for management of DKA. The research protocol was approved the by Institutional Ethics Committee.

Table 1.

Treatment protocol of patients of mild to moderate diabetic ketacidosis

At the time of admission, thorough clinical assessment was done that included detailed history and complete general and systemic examination. Respiratory rate, temperature, pulse, and blood pressure were recorded. The hydration status was assessed by dryness of tongue, reduced skin turgor, sunken eyes, tachycardiaand hypotension, and decreased urine output. Intravenous fluid administration was started immediately with 0.9% sodium chloride solution at the rate of 10-20 ml/kg/h for initial 1-2 h. Subsequent fluid replacement was based on hydration status, hemodynamic parameters, serum electrolytes, and urine output. The patients who were assigned to group 1 received an initial bolus of regular insulin 0.1 unit/kg intravenously followed by continuous infusion of regular insulin calculated to deliver 0.1 unit/kg/h until blood glucose levels decreased to approximately 250 mg/dl when insulin infusion rate was decreased to 0.05 units/kg/h until resolution of DKA and intravenous fluids were changed to dextrose containing solutions (5% dextrose) to keep blood glucose level approximately at 200 mg/dl. The patients assigned to group two received subcutaneous insulin lispro as initial bolus of 0.3 units/kg followed by 0.2 units/kg 1 h later and then 0.2 units/kg every 2 hourly until blood glucose reached 250 mg/dl. The insulin dose was then reduced to 0.1 units/kg/h to keep blood glucose ~200 mg/dl. The fluid and electrolyte management was similar in two groups as per protocol. Insulin therapy, correction of acidosis, and volume expansion leads to hypokalemia. To prevent hypokalemia, potassium replacement was initiated during second hour after ensuring adequacy of urine output.

Levels of glucose, electrolytes, urea, creatinine, arterial pH, and urinary ketones were determined at admission and then at 4, 8, 12, 16, and 24 h of treatment. Total blood count, electrocardiogram, chest radiograph, urinanalysis, urine, and blood cultures were undertaken to detect the precipitating cause. During treatment blood glucose levels were determined at bedside by finger stick hourly in all the patients. Resolution of ketoacidosis was considered when serum bicarbonate level was >18 mmol/l and arterial pH was >7.3.[21] When these levels were achieved the intravenous regular insulin infusion or subcutaneous lispro injections were discontinued with an overlap of 1-2 h after the administration of subcutaneous regular insulin to prevent the recurrence of hyperglycemia and ketoacidosis. Then the patients were switched back to pre-admission doses of short and intermediate acting insulin with adjustments if required. Patients with newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus received a split-mixed insulin dose of 0.5-0.8 units/kg/day, 2/3 as intermediate acting and 1/3 as regular insulin in two to three doses. Response to therapy was assessed by time and amount of insulin required for resolution of hyperglycemia and ketacidosis and number of hypoglycemic events (defined as a blood glucose value <60 mg/dl) during therapy.

Statistical Analysis

All data in the text and tables are expressed as mean± SD. For comparison of baseline demographic and clinical characteristics between two groups an unpaired Student's t-test was used. All statistical analyses was done by using the Statistical package for social sciences (SPSS 15.0 version) with P < 0.05 taken as significant.

Results

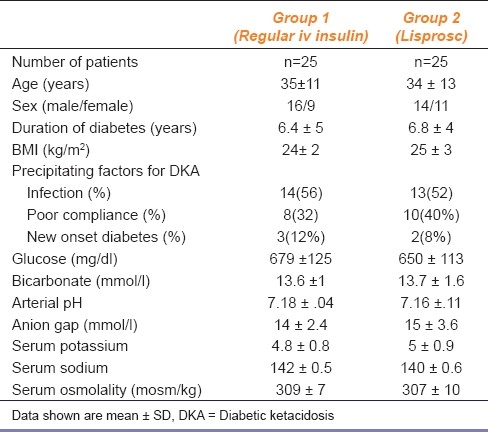

The study included 25 patients treated with regular intravenous insulin infusion in intensive care unit and 25 patients treated with subcutaneous insulin lispro in emergency ward. The baseline clinical characteristics of the two groups are shown in Table 2. Mean age, BMI, and duration of diabetes were similar. More than half of the patients in both the groups had type 2 diabetes. The precipitating cause of DKA was infection (56% and 52%) and poor compliance to insulin therapy (32% and 40%). Newly diagnosed patients of diabetes were 12% and 8% in the two groups, respectively.

Table 2.

Baseline profile of patients of mild to moderate diabetic ketoacidosis

The biochemical parameters at the time of admission in patients treated with insulin lispro were similar to those treated with intravenous regular insulin infusion.The response to treatment in two groups has been shown in Table 3. No differences were recorded in time taken for decline of blood glucose (7.2 ±2 h vs. 7.5±3 h), disappearance of urine ketones or resolution of metabolic acidosis (11± 1.6 h vs. 12 ±2.2 h) between the two study groups. The amount of two types of insulin's required for correction of hyperglycemia (69 ±13 units vs. 66 ±12 units) and ketacidosis (104 ±12 units vs. 100 ±14 units) were similar and the duration of hospital stay (6.6± 1.5 days vs. 6.0 ±1.2 days) was also not different between the two groups. The duration of hospital stay and amount of insulin required for correction of hyperglycemia was significantly higher in patients who had infection as the precipitating cause than those with poor compliance in both the groups. Three patients (two in the intravenous insulin group and one in the lispro group) experienced mild hypoglycemia. There was no need to increase or change the dose or route of insulin administration due to delayed or inadequate response in any of the patient in the lispro group. None of the patient in either group developed complications such as venous thrombosis, adult respiratory distress syndrome, or hyperchloremic acidosis which could be associated with infusion of large volumes of normal saline. There was no mortality and none of the patients had the recurrence of ketoacidosis during the hospital stay.

Table 3.

Treatment response in patients of mild to moderate diabetic ketoacidosis

Discussion

The DKA is an acute metabolic complication in patients with diabetes mellitus. It is associated with significant morbidity and use of health care resources. The aim of our study was to compare the efficacy of rapid acting insulin analog lispro given subcutaneously with that of standard low dose intravenous regular insulin infusion in patients with mild to moderate ketoacidosis. The results of our study show that treatment with subcutaneous insulin lispro administered 2 hourly is as safe and effective as treatment with conventional intravenous regular insulin infusion in such patients. The rate of decline of blood glucose, time taken for resolution of ketoacidosis, amount of insulin required for control of hyperglycemia, and resolution of ketoacidosis were similar between the two treatment groups. The duration of hospital stay also was not different between the groups. In our study population, infection and poor compliance with insulin regimen were the most common precipitating factors of DKA, for which ignorance, poor compliance, and poverty might be the probable reasons.

The intravenous infusion of regular insulin has been the mainstay of treatment of DKA as it causes more predictable fall in blood glucose and it allows for rapid adjustments. Nevertheless, intravenous insulin infusion requires need of infusion pumps and another venous line to allow independent handling of fluid replacement and insulin infusion rate. We recognize that admitting patients into intensive care units is difficult because of limited availability of beds and also it is associated with higher costs. The protocols of DKA treatment with subcutaneous rapid acting insulin analogs represent a technical simplification and may lower the cost of treatment as patient will not need infusion pumps or second intravenous line so it will obviate the need of admission in intensive care unit and reduce the cost of hospitalization.

Umpierrez et al.,[15] in a prospective, randomized study compared the efficacy and safety of subcutaneous insulin lispro every hour with that of standard low dose intravenous infusion of regular insulin in adult patients with DKA. They observed comparable blood glucose decrease rates and control of ketoacidosis between the two groups of adults receiving subcutaneous lispro 1-2 hourly and a group treated with intravenous regular insulin. They concluded that patients with uncomplicated DKA can be managed safely with rapid acting insulin analogs in general medical wards or stepped down units. Treatment of DKA in intensive care unit was associated with 39% higher hospitalization charges.[15] They had the similar conclusions in another study done with insulin as part 1-2 hourly.[16] Della Manna et al.,[17] also found rapid acting insulin analog as safe and effective alternative to regular insulin in their study done in pediatric patients with DKA.

The limitations of our study were very small number of patients and exclusion of patients with severe DKA.The commitment of residents and paramedical staff is required for proper management of DKA whether it is in intensive care unit or emergency medical ward.

Conclusion

We had a local experience to facilitate DKA management in emergency medical ward. Our study indicates that patients with uncomplicated DKA under appropriate supervision and careful monitoring can be managed in medical wards or non-ICU settings. A rapid acting insulin analog is safe and effective alternative to intravenous regular insulin infusion in patients with uncomplicated DKA.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Bismuth E, Laffel L. Can we prevent diabetic ketoacidosis in children? Pediatr Diabetes. 2007;8(suppl 6):24–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2007.00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White NH. Diabetic ketoacidosis in children. Endocriol Metab Clin North Am. 2000;29:657–82. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8529(05)70158-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Umipierrez GE, Kitabchi AE. Diabetic Ketacidosis: Risk factors and management strategies. Treat Endocrinol. 2003;2:95–108. doi: 10.2165/00024677-200302020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valabhji J, Watson M, Cox J, Poulter C, Elwig C, Elkeles RS. Type 2 Diabetes presenting as diabetic ketoacidosis in adolescence. Diabet Med. 2003;20:416–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.00942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balasubramanyam A, Zern JW, Hyman DJ, Pavlik V. New profiles of diabetic ketoacidosis: Type 1 and type 2 diabetes and the effects of ethnicity. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2317–22. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.19.2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Umipierrez GE, Casals MM, Gebhart SS, Mixon PS, Clark WS, Phillips LS. Diabetic Ketoacidosis in obese African-Americans. Diabetes. 1995;44:790–5. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.7.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitabchi AE, Smiley D, Umipierrez GE. Narrative Review: Ketosis prone type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:350–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-5-200603070-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savage M, Kilvert A. On behalf of ABCD. ABCD guidelines for the management of hyperglycemic emergencies in adults. Pract Diabetes Inter. 2006;23:227–31. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolfsdorf JI, Craig ME, Daneman D, Dunger D, Edge JA, Lee WR. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2009 Compendium- Diabetic Ketoacidosis in children and adolescents with diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2009;10(Suppl 12):118–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.New UK guidelines for DKA management from March 2010. [last accessed on 2010 Dec 6]. Available from: http://www.diabetes.nhs.uk/publications_and_resources/reports_and_guidance/

- 11.Kitabchi AE, Umipierrez GE, Fisher JN, Murphy MB, Stentz FB. Thirty years of personal experience in hyperglycemic crises: Diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:1541–52. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lebovitz HE. Diabetic ketoacidosis. Lancet. 1995;345:767–72. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90645-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitabchi AE, Umipierrez GE, Murphy MB, Kreisberg RA. Hyperglycemic crises in adult patients with diabetes.A consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2739–48. doi: 10.2337/dc06-9916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitabchi AE, Umipierrez GE, Miles JM, Fisher JN. Hyperglycemic crises in adult patients with diabetes: A consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1335–43. doi: 10.2337/dc09-9032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazer M, Chen E. Is subcutaneous administration of rapid acting insulin as effective as intravenous insulin for treating diabetic ketoacidosis? Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:259–63. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Umipierrez GE, Latif KA, Stover R, Cuervo R, Karabell A, Freire AX, et al. Efficacy of subcutaneous insulin lispro versus continuous intravenous regular insulin for the treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis. Am J Med. 2004;117:291–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Umipierrez GE, Latif KA, Cuervo R, Karabell A, Freire AX, Kitabchi AE. Treatment ofdiabetic ketoacidosis with subcutaneous insulin Aspart. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1873–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.8.1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Della Manna T, Steinmetz L, Campose PR, Farhat SC, Schvartsman C, Kuperman H, et al. Subcutaneous use of a fast-acting insulin analogue: An alternative treatment for paediatric patients with diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1856–61. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.8.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ersoz HO, Ukinc K, Kose M, Erem C, Gunduz A, Hacihasanoglu AB, et al. Subcutaneous lispro and intravenous regular insulin treatments are equally effective and safe for the treatment of mild and moderate diabetic ketoacidosis in adult patients. Int J ClinPract. 2006;60:429–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2006.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Savoldelli RD, Farhat SC, Manna TD. Alternative management of diabetic ketoacidosis in a Brazilian pediatric emergency department. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2010;2:41. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-2-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kitabchi AE, Umipierrez GE, Murphy MB, Barrett EJ, Kreisberg RA, Malone JI. Management of hyperglycemic crises in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:131–53. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]