Abstract

(±)-3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) is a commonly abused illicit drug which affects multiple organ systems. In animals, high-dose administration of MDMA produces deficits in serotonin (5-HT) neurons (e.g., depletion of forebrain 5-HT) that have been viewed as neurotoxicity. Recent data implicate MDMA in the development of valvular heart disease (VHD). The present paper reviews several issues related to MDMA-associated neural and cardiac toxicities. The hypothesis of MDMA neurotoxicity in rats is evaluated in terms of the effects of MDMA on monoamine neurons, the use of scaling methods to extrapolate MDMA doses across species, and functional consequences of MDMA exposure. A potential treatment regimen (l-5-hydroxytryptophan plus carbidopa) for MDMA-associated neural deficits is discussed. The pathogenesis of MDMA-associated VHD is reviewed with specific reference to the role of valvular 5-HT2B receptors. We conclude that pharmacological effects of MDMA occur at the same doses in rats and humans. High doses of MDMA that produce 5-HT depletions in rats are associated with tolerance and impaired 5-HT release. Doses of MDMA that fail to deplete 5-HT in rats can cause persistent behavioral dysfunction, suggesting even moderate doses may pose risks. Finally, the MDMA metabolite, 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA), is a potent 5-HT2B agonist which could contribute to the increased risk of VHD observed in heavy MDMA users.

I. Introduction

3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA or Ecstasy) is a popular illicit drug in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere. The allure of MDMA is likely related to its unique profile of psychotropic effects which includes amphetamine-like mood elevation, coupled with feelings of increased emotional sensitivity and closeness to others (Liechti and Vollenweider, 2001; Vollenweider et al., 1998). MDMA misuse among adolescents is widespread in the United States (Landry, 2002; Yacoubian, 2003), and a recent sampling of high school seniors found 10% reported using MDMA at least once (Banken, 2004). The incidence of MDMA-related medical complications has risen in parallel with the increasing popularity of the drug. Serious adverse effects of MDMA intoxication include hyperthermia, serotonin (5-HT) syndrome, cardiac arrhythmias, hypertension, hyponatremia, liver problems, seizures, coma, and death (Schifano, 2004). Accumulating evidence suggests that heavy MDMA use is associated with cognitive impairments, mood disturbances, and cardiac valve dysfunction, in some cases lasting for months after cessation of drug intake (Morgan, 2000; Parrott, 2002). Despite the risks of illicit MDMA use, a number of clinicians believe the drug has therapeutic value in the treatment of psychiatric disorders, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (Doblin, 2002), and clinical studies with MDMA are underway (see http://clinicaltrials.gov). In controlled research settings, MDMA has been administered safely to humans, but adverse effects have been documented in certain individuals (Harris et al., 2002; Mas et al., 1999).

These considerations provide compelling reasons to evaluate the pharmacology and toxicology of MDMA. The present paper several issues related to MDMA-associated toxicities. The hypothesis of MDMA neurotoxicity in rats is evaluated in terms of MDMA effects on monoamine neurons, the use of scaling methods to adjust MDMA doses across species, and functional consequences of MDMA-induced 5-HT depletions. A potential treatment regimen (l-5-hydroxytryptophan plus carbidopa) for MDMA-associated neural deficits is discussed. The pathogenesis of MDMA-associated valvular heart disease (VHD) is reviewed with particular reference to the role of 5-HT2B receptors. Previously published data from our laboratory at the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) will be included to supplement literature reports. Clinical findings will be mentioned in specific instances to note comparisons between rats and humans.

The neurotoxicity aspect of this review will focus on data obtained from rats since most preclinical MDMA research has been carried out in this animal model. Data from mice will not be considered because this species displays the unusual characteristic of long-term dopamine (DA) depletions (i.e., DA neurotoxicity) in response to MDMA, rather than long-term 5-HT depletions observed in rats, nonhuman primates, and most other animals (reviewed by Colado et al., 2004). We will not address possible molecular mechanisms underlying MDMA-induced 5-HT deficits, as several excellent reviews have covered this subject (Lyles and Cadet, 2003; Monks et al., 2004; Sprague et al., 1998). All experiments in our laboratory utilized male Sprague–Dawley rats (Wilmington, MA) weighing 300–350 g. Rats were maintained in facilities accredited by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, and procedures were carried out in accordance with the Animal Care and Use Committee of the NIDA Intramural Research Program (IRP).

II. Effects of MDMA on Monoamine Neurons

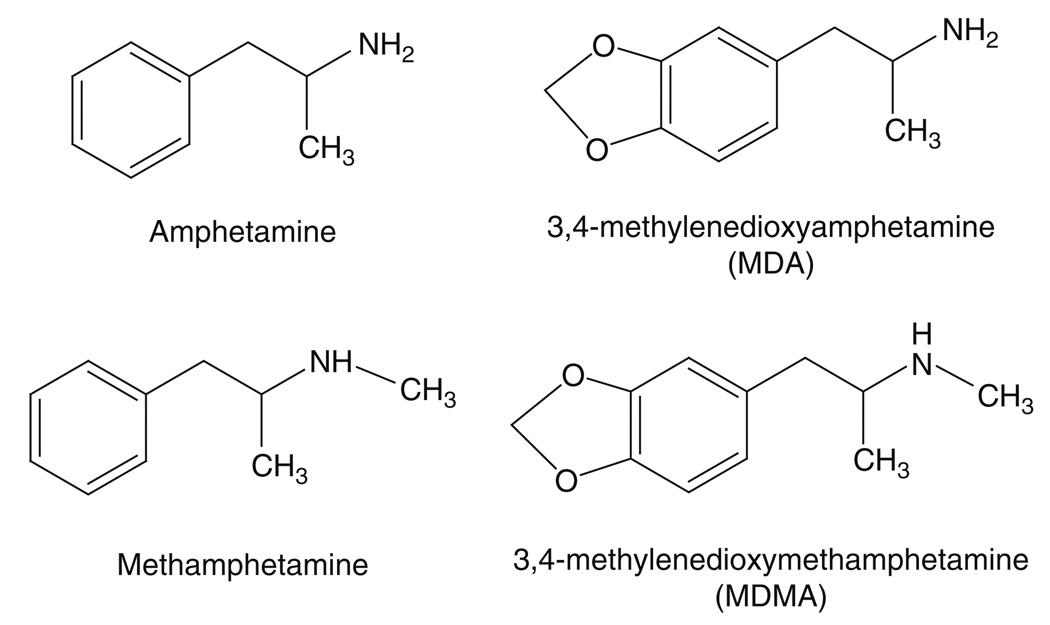

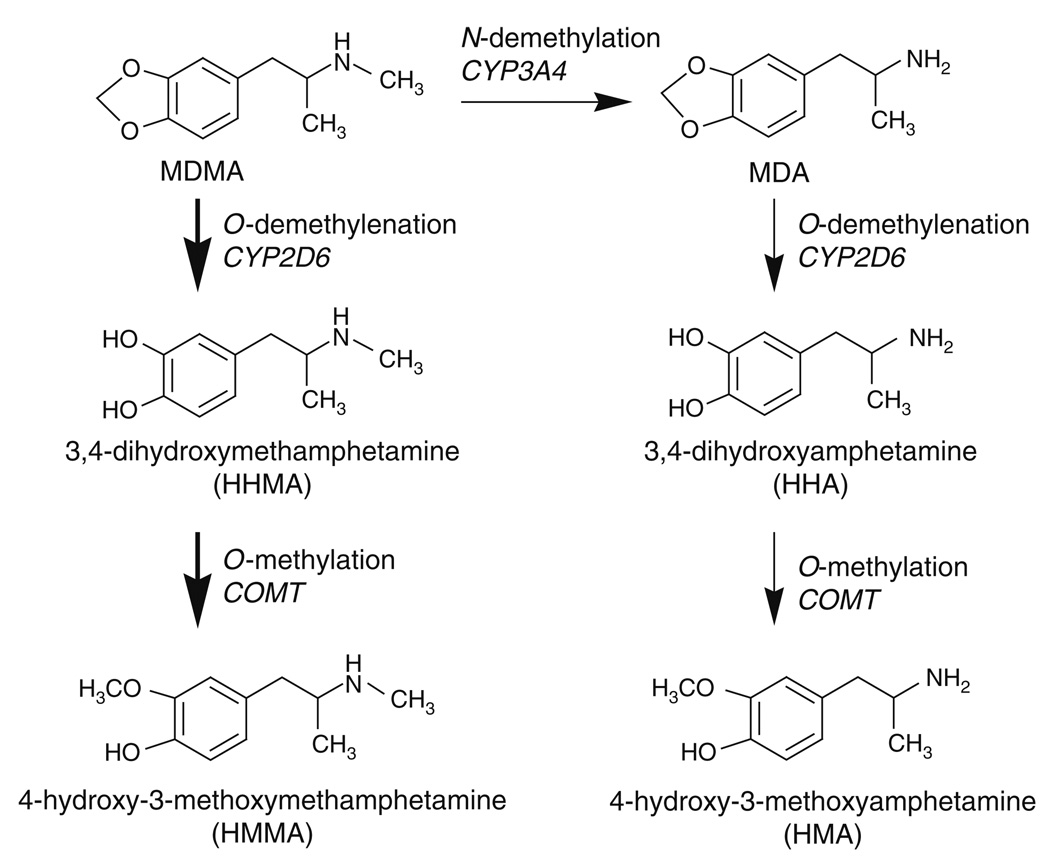

In order to critically evaluate the hypothesis of MDMA-induced 5-HT neurotoxicity, a brief review of MDMA pharmacology is necessary. Figure 1 shows that MDMA is a ring-substituted analog of methamphetamine. Ecstasy tablets ingested by humans contain a racemic mixture of (+) and (−) isomers of MDMA, and both isomers are bioactive (Johnson et al., 1986; Schmidt, 1987). Ecstasy tablets often contain other psychoactive substances such as substituted amphetamines, caffeine, or ketamine, which can contribute to the overall effects of the ingested preparation (Parrott, 2004). Upon systemic administration, 𝒩-demethylation of MDMA occurs via first-pass metabolism to yield the ring-substituted amphetamine analog 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA) (de la Torre et al., 2004). Initial studies carried out in the 1980s showed that MDMA and MDA stimulate efflux of preloaded [3H]5-HT, and to a lesser extent [3H]DA, in nervous tissue (Johnson et al., 1986; Nichols et al., 1982; Schmidt et al., 1987). Subsequent findings revealed that MDMA interacts with monoamine transporter proteins to stimulate nonexocytotic release of 5-HT, DA, and norepinephrine (NE) in rat brain (Berger et al., 1992; Crespi, 1997; Fitzgerald and Reid, 1993).

FIG. 1.

Chemical structures of MDMA and related amphetamines.

Like other substrate-type releasers, MDMA and MDA bind to transporter proteins and are subsequently transported into the cytoplasm of nerve terminals, releasing neurotransmitters via a process originally described as carrier-mediated exchange (for review see Rothman and Baumann, 2006; Rudnick and Clark, 1993). However, the mechanism by which substrates induce the release of neurotransmitters is more complicated than a simple exchange process. Recent studies of the DA transporter (DAT) have shown that inward transport of a substrate like amphetamine is accompanied by an inward sodium current, which increases the concentration of intracellular sodium at the transporter, thereby facilitating reverse transport of DA (Goodwin et al., 2008; Pifl et al., 2009). Determining the precise molecular mechanism of transporter-mediated release of 5-HT is a topic of ongoing research.

Table I summarizes published data from our laboratory showing structure–activity relationships for stereoisomers of MDMA, MDA, and related drugs as monoamine releasers in rat brain synaptosomes (Partilla et al., 2000; Rothman et al., 2001; Setola et al., 2003). Stereoisomers of MDMA and MDA are substrates for 5-HT transporters (SERT), NE transporters (NET), and DAT, with (+) isomers exhibiting greater potency as releasers. In particular, (+) isomers of MDMA and MDA are much more effective DA releasers than their corresponding (−) isomers. It is noteworthy that (+) isomers of MDMA and MDA are rather nonselective in their ability to stimulate monoamine release in vitro. When compared to amphetamine and methamphetamine, the major effect of methylenedioxy ring-substitution is enhanced potency for 5-HT release and reduced potency for DA release. For example, (+)-MDMA releases 5-HT (EC50 = 70.8 nM) about 10 times more potently than (+)-methamphetamine (EC50 = 736 nM), whereas (+)-MDMA releases DA (EC50 = 142 nM) about six times less potently than (+)-methamphetamine (EC50 = 24 nM).

TABLE I.

Profile of MDMA and Related Compounds as Monoamine Transporter Substrates in Rat Brain Synaptosomes

| Drug | 5-HT release EC50 (nM ± S.D.) |

NE release EC50 (nM ± S.D.) |

DA release EC50 (nM ± S.D.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (+)-Methamphetamine | 736 ± 45 | 12 ± 0.7 | 24 ± 2 |

| (−)-Methamphetamine | 4640 ± 240 | 29 ± 3 | 416 ± 20 |

| (±)-MDMA | 74.3 ± 5.6 | 136 ± 17 | 278 ± 12 |

| (+)-MDMA | 70.8 ± 5.2 | 110 ± 16 | 142 ± 6 |

| (−)-MDMA | 337 ± 34 | 564 ± 60 | 3682 ± 178 |

| (+)-Amphetamine | 1765 ± 94 | 7.1 ± 1.0 | 25 ± 4 |

| (±)-MDA | 159 ± 12 | 108 ± 12 | 290 ± 10 |

| (+)-MDA | 99.6 ± 7.4 | 98.5 ± 6.1 | 50.0 ± 8.0 |

| (−)-MDA | 313 ± 21 | 287 ± 23 | 900 ± 49 |

Data are taken from Partilla et al. (2000), Rothman et al. (2001), and Setola et al. (2003). Details concerning in vitro methods can be found in these papers. Substrate activity at SERT, NET, and DAT is reflected as release efficacy for the corresponding transmitter.

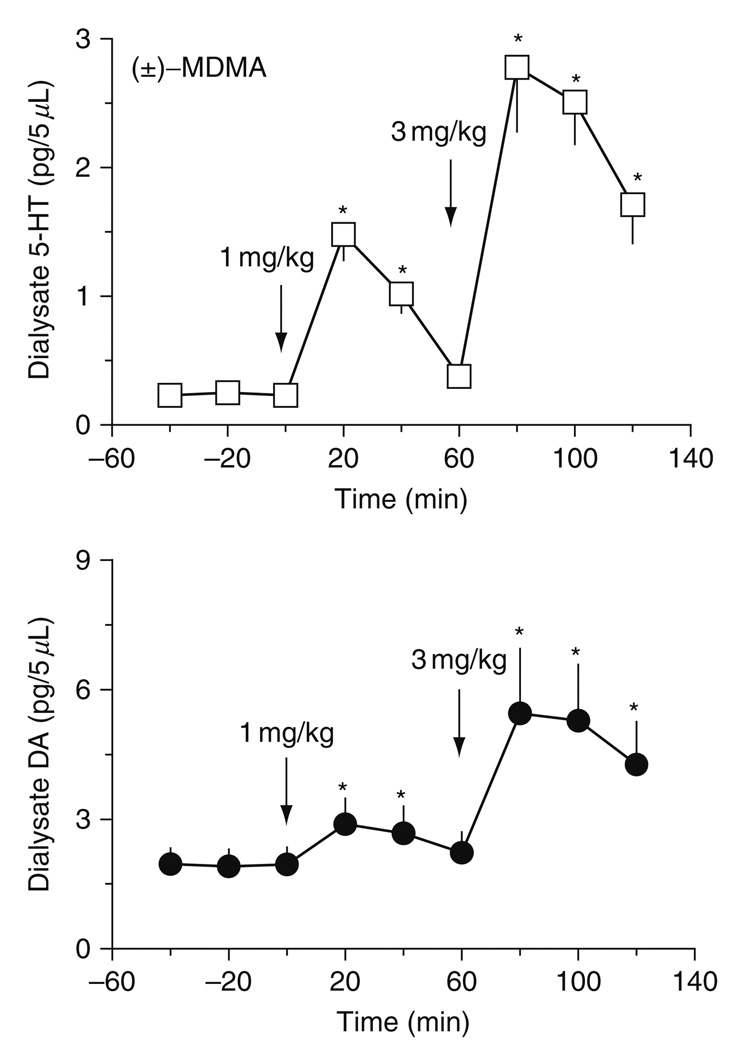

Consistent with in vitro results, in vivo microdialysis experiments demonstrate that MDMA increases extracellular 5-HT and DA in rat brain, with effects on 5-HT being greater in magnitude (Baumann et al., 2005; Gudelsky and Nash, 1996; Kankaanpaa et al., 1998; Yamamoto et al., 1995). Figure 2 depicts data from our laboratory showing the stimulatory effects of MDMA on extracellular 5-HT and DA in rat n. accumbens (Baumann et al., 2005). In these experiments, rats undergoing microdialysis received i.v. injections of 1 mg/kg MDMA at time zero, followed by 3 mg/kg MDMA 60 min later. Importantly, these doses of MDMA are comparable to those used in rat self-administration paradigms (Ratzenboeck et al., 2001; Schenk et al., 2003). In all of our microdialysis studies, samples are collected at 20 min intervals beginning 1 h before injections, until 1 h after the second dose of drug; samples are assayed for 5-HT and DA by high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to electrochemical detection (HPLC-ECD) (Baumann and Rutter, 2003). Neurochemical data are expressed as pg/5 µl sample. MDMA causes significant dose-related increases in dialysate 5-HT [F8,45 = 33.04, P < 0.0001] and DA [F8,45 = 5.56, P < 0.001] in n. accumbens. At both doses, elevations in extracellular 5-HT are much greater than corresponding elevations in DA. For example, the 1 mg/kg dose of MDMA produces a 7.5-fold rise in 5-HT but only a 1.5-fold rise in DA.

FIG. 2.

Effects of i.v. MDMA on concentrations of 5-HT (top panel) and DA (bottom panel) in dialysate samples obtained from rat n. accumbens. Conscious rats undergoing in vivo microdialysis received i.v. injections of 1 mg/kg MDMA at time zero followed by 3 mg/kg 60 min later. Dialysate samples obtained at 20 min intervals were assayed for 5-HT and DA by HPLC-ECD. Data are mean ± S.E.M., expressed as pg/5 µl sample for 𝒩 = 7 rats/group. *P < 0.05 versus preinjection baseline. (Modified from Baumann et al., 2005).

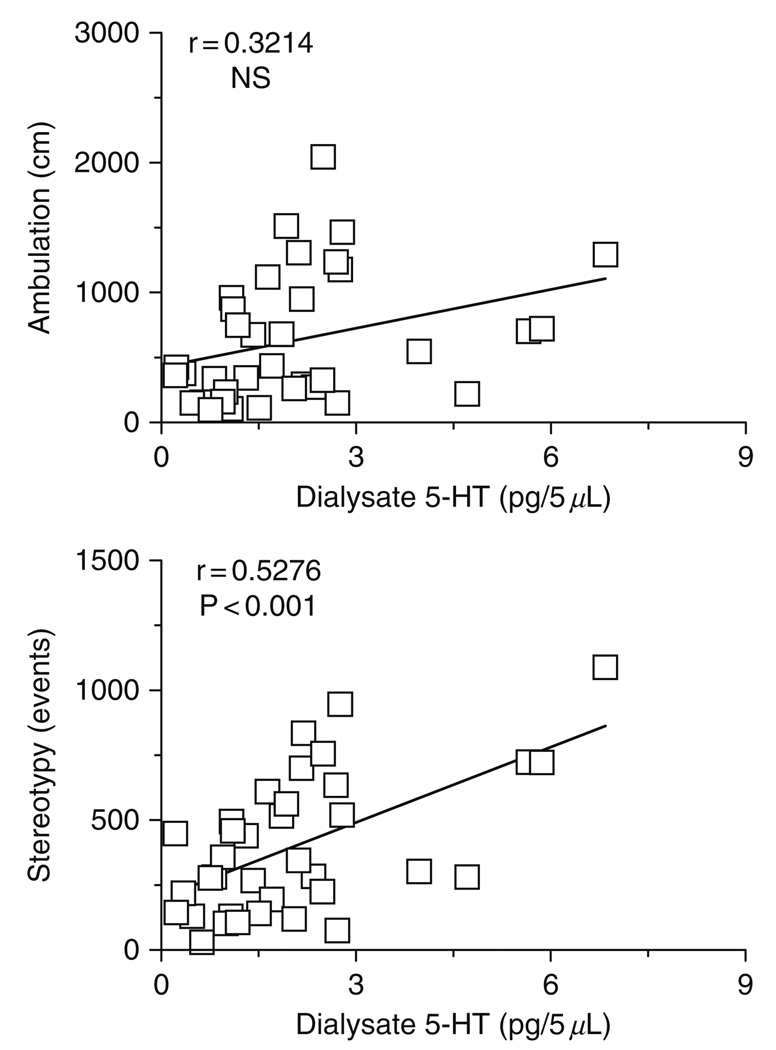

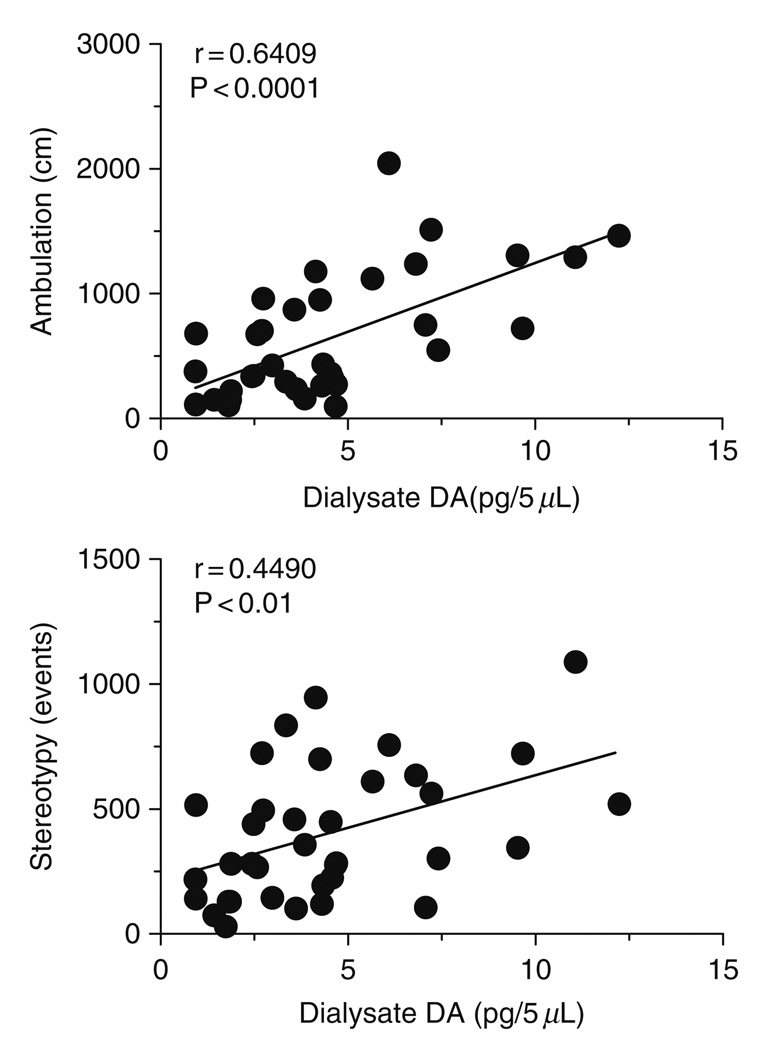

Acute central nervous system (CNS) effects of MDMA are presumably mediated by release of monoamine transmitters, with the subsequent activation of pre- and postsynaptic receptors (reviewed by Cole and Sumnall, 2003; Green et al., 2003). As a specific example in rats, MDMA elicits a unique spectrum of motor actions characterized by forward locomotion (i.e., ambulation) and elements of the 5-HT behavioral syndrome such as forepaw treading and head weaving (i.e., stereotypy) (Gold et al., 1988; Slikker et al., 1989; Spanos and Yamamoto, 1989). It is well established that hyperactivity caused by MDMA is dependent upon activation of multiple 5-HT and DA receptor subtypes in the brain (reviewed by Bankson and Cunningham, 2001; Geyer, 1996). We examined the role of brain monoamines in mediating locomotor effects of MDMA by combining in vivo microdialysis with automated analysis of motor behaviors (Baumann et al., 2008b). Microdialysis guide cannulae were aimed at various brain regions implicated in motor stimulation, including n. accumbens, striatum, and prefrontal cortex. Conscious rats undergoing microdialysis were housed in chambers equipped with photobeams to assess ambulation and stereotypy. Neurochemical and locomotor effects of MDMA administration were determined simultaneously in the same individual rats, thereby allowing the use of Pearson correlation analysis to examine relationships between pg amounts of transmitter, distance traveled and stereotypic events. Figure 3 depicts representative data from the n. accumbens where MDMA-induced elevations in dialysate 5-HT are positively correlated with stereotypy [r = 0.5276, P < 0.0001] but not ambulation [r = 0.3241, NS]. On the other hand, Fig. 4 shows that increases in accumbens DA are highly correlated with ambulation [r = 0.6409, P < 0.0001] and somewhat less so with stereotypy [r = 0.4490, P < 0.01]. Our correlation data from various brain regions indicate that motor effects produced by MDMA involve transporter-mediated release of 5-HT and DA in a region- and modality-specific manner. Additionally, the role of NE in modulating behavioral effects of MDMA is largely unexplored, and this issue warrants further study (Selken and Nichols, 2007; Starr et al., 2008).

FIG. 3.

Correlations between dialysate 5-HT in the n. accumbens versus ambulation (top panel) and stereotypy (bottom panel) produced by MDMA. Conscious rats undergoing in vivo microdialysis received i.v. injections of 1 mg/kg MDMA at time zero followed by 3 mg/kg 60 min later. Data points represent raw values obtained at 20 min intervals, from +20 min (first sample after 1 mg/kg) through +120 min (last sample after 3 mg/kg) for 𝒩 = 6 rats. Pearson correlation coefficients (r) are shown with corresponding P values. (Modified from Baumann et al., 2008b).

FIG. 4.

Correlations between dialysate DA in the n. accumbens versus ambulation (top panel) and stereotypy (bottom panel) produced by MDMA. Conscious rats undergoing in vivo microdialysis received i.v. injections of 1 mg/kg MDMA at time zero followed by 3 mg/kg 60 min later. Data points represent raw values obtained at 20 min intervals, from +20 min (first sample after 1 mg/kg) through +120 min (last sample after 3 mg/kg) for 𝒩 = 6 rats. Pearson correlation coefficients (r) are shown with corresponding P values. (Modified from Baumann et al., 2008b).

Adverse effects of acute MDMA administration, including cardiovascular stimulation and elevated body temperature, are thought to involve monoamine release from sympathetic nerves in the periphery or nerve terminals in the CNS. MDMA increases heart rate and mean arterial pressure in conscious rats (O’Cain et al., 2000); this cardiovascular stimulation is likely mediated by MDMA-induced release of peripheral NE stores, similar to the effects of amphetamine (Fitzgerald and Reid, 1994). MDMA has weak agonist actions at α2-adrenoreceptors and 5-HT2 receptors that might influence its cardiac and pressor effects (Battaglia and De Souza, 1989; Lavelle et al., 1999; Lyon et al., 1986). Moreover, as will be described in more detail in a subsequent part of this review, MDA is a potent 5-HT2B agonist and this property could contribute to adverse cardiovascular effects (Setola et al., 2003). The ability of MDMA to elevate body temperature is well characterized in rats (Dafters, 1995; Dafters and Lynch, 1998; Nash et al., 1988), and this response has been considered a 5-HT-mediated process. However, the data of Mechan et al. (2002) provide convincing evidence that MDMA-induced hyperthermia involves the activation of postsynaptic D1 receptors by released DA.

III. Long-Term Effects of MDMA on 5-HT Systems

The long-term adverse effects of MDMA on 5-HT systems have attracted substantial interest, since studies in rats and nonhuman primates show that high-dose MDMA administration produces persistent reductions in markers of 5-HT nerve terminal integrity (reviewed by Lyles and Cadet, 2003; Sprague et al., 1998). Table II summarizes the findings of investigators who first demonstrated that MDMA causes long-term (>1 week) inactivation of tryptophan hydroxylase activity, depletions of brain tissue 5-HT, and reductions in SERT binding and function (Battaglia et al., 1987; Commins et al., 1987; Schmidt, 1987; Stone et al., 1987). These serotonergic deficits are observed in various regions of rat forebrain, including frontal cortex, striatum, hippocampus, and hypothalamus. Immunohistochemical analysis of 5-HT in cortical and subcortical areas reveals an apparent loss of 5-HT axons and terminals in MDMA-treated rats, especially the fine-diameter projections arising from the dorsal raphe nucleus (O’Hearn et al., 1988). Moreover, 5-HT axons and terminals remaining after MDMA treatment appear swollen and fragmented, suggesting structural damage.

TABLE II.

Long-Term Effects of (±)-MDMA on 5-HT Neuronal Markers in Rats

| 5-HT deficit | Dose | Survival interval |

References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depletions of 5-HT in cortex, as measured by HPLC-ECD | 10 mg/kg, s.c., single dose | 1 week | Schmidt (1987) |

| Depletions of 5-HT in forebrain regions as measured by HPLC-ECD | 10–40 mg/kg, s.c., twice daily, 4 days | 2 weeks | Commins et al. (1987) |

| Reductions in tryptophan hydroxylase activity in forebrain regions | 10 mg/kg, s.c., single dose | 2 weeks | Stone et al. (1987) |

| Loss of [3H]-paroxetine-labeled SERT binding sites in forebrain regions | 20 mg/kg, s.c., twice daily, 4 days | 2 weeks | Battaglia et al. (1987) |

| Deceased immunoreactive 5-HT in fine axons and terminals in forebrain regions | 20 mg/kg, s.c., twice daily, 4 days | 2 weeks | O’Hearn et al. (1988) |

Time-course studies indicate that MDMA-induced 5-HT depletions occur in a biphasic manner, with a rapid acute phase followed by a delayed long-term phase (Schmidt, 1987; Stone et al., 1987). In the acute phase, which lasts for the first few h after drug administration, massive depletion of brain tissue 5-HT is accompanied by inactivation of tryptophan hydroxylase. By 24 h later, tissue 5-HT recovers to normal levels but hydroxylase activity remains diminished. In the long-term phase, which begins within 1 week and lasts for months, marked depletion of 5-HT is accompanied by sustained inactivation of tryptophan hydroxylase and loss of SERT binding and function (Battaglia et al., 1988; Scanzello et al., 1993). The findings summarized in Table II have been replicated by many investigators, and the spectrum of decrements is typically described as 5-HT neurotoxicity (Baumann et al., 2007; Ricaurte et al., 2000). Most of the studies designed to examine MDMA neurotoxicity in rats have employed i.p. or s.c. injections of 10 mg/kg or higher, either as single or repeated treatments. These MDMA dosing regimens are known to produce significant hyperthermia, which can exacerbate 5-HT depletions caused by the drug (Green et al., 2004; Malberg and Seiden, 1998). Most investigations have involved non-contingent administration of MDMA rather than self-administration, and this factor could significantly influence effects of the drug.

There are caveats to the hypothesis that MDMA produces 5-HT neurotoxicity. O’Hearn et al. (1988) showed that high-dose MDMA administration has no effect on 5-HTcell bodies in the dorsal raphe, despite profound loss of 5-HT in forebrain projection areas. Thus, the effects of MDMA on 5-HT neurons are sometimes referred to as “axotomy,” to account for the fact that perikarya are not damaged (Molliver et al., 1990; O’Hearn et al., 1988). MDMA-induced reductions in 5-HT levels and SERT binding eventually recover (Battaglia et al., 1988; Scanzello et al., 1993), suggesting that 5-HTterminals are not destroyed. Many drugs used clinically produce effects that are similar to those produced by MDMA. For instance, reserpine causes sustained depletions of brain tissue 5-HT, yet reserpine is not considered a neurotoxin (Carlsson, 1976). Chronic administration of 5-HT selective reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), like paroxetine and sertraline, leads to a marked loss of SERT binding and function comparable to MDMA, but these agents are therapeutic drugs rather than neurotoxins (Benmansour et al., 1999; Frazer and Benmansour, 2002). Finally, high-dose administration of SSRIs produces swollen, fragmented, and abnormal 5-HT terminals which are indistinguishable from the effects of MDMA and other substituted amphetamines (Kalia et al., 2000).

The caveats mentioned above raise a number of questions with respect to MDMA neurotoxicity. Of course, the most important question is whether MDMA abuse causes neurotoxic damage in humans. This complex issue is a matter of ongoing debate which has been addressed by a number of recent papers (Gouzoulis-Mayfrank et al., 2002; Kish, 2002; Reneman, 2003). Clinical studies designed to critically evaluate the long-term effects of MDMA are hampered by a number of factors including comorbid psychopathology and poly-drug abuse among MDMA users. Animal models afford the unique opportunity to evaluate the effects of MDMA without many of these complicating factors, and the main focus here will be to review the evidence pertaining to MDMA-induced 5-HT neurotoxicity in rats.

IV. Scaling Methods and MDMA Dosing

A major point of controversy relates to the relevance of MDMA doses administered to rats when compared to doses taken by humans (see Cole and Sumnall, 2003). As noted earlier, MDMA regimens that produce 5-HT depletions in rats involve administration of single or multiple injections of 10–20 mg/kg, whereas the typical dose of Ecstasy abused by humans is one or two tablets of 80–100 mg MDMA, or 1–3 mg/kg administered orally (Green et al., 2003; Schifano, 2004). Based on principles of allometric scaling (i.e., interspecies scaling), some investigators have proposed that neurotoxic doses of MDMA in rats correspond to recreational doses in humans (Ricaurte et al., 2000). In order to critically evaluate this claim, a brief discussion of interspecies scaling is warranted. The concept of interspecies scaling is based upon shared biochemical mechanisms among eukaryotic cells (e.g., aerobic respiration), and was initially developed to describe variations in basal metabolic rate (BMR) between animal species of different sizes (reviewed by White and Seymour, 2005). In the 1930s, Kleiber (1932) derived what is now called the “allometric equation” to describe the relationship between body mass and BMR. The generic form of the allometric equation is: ϒ = aWb, where “ϒ” is the variable of interest, “W” is body weight, “a” is the allometric coefficient, and “b” is the allometric exponent. In the case where “ϒ” is BMR, b is accepted to be 0.75. West et al. (2002) have shown that most biological phenomena scale according to a universal quarter-power law, as illustrated by the space-filling fractal networks of branching tubes used by the circulatory system.

Given that the allometric equation is grounded in fundamental commonalities across organisms, it is not surprising this equation can describe the relationship between body mass and physiological variables, such as BMR, heart rate, and circulation time (e.g., Noujaim et al., 2004). Because circulation time and organ blood flow strongly influence drug pharmacokinetics, the allometric equation has been used in the medication development process to “scale-up” dosages from animal models to man (reviewed by Mahmood, 1999). In general, smaller animals have faster heart rates and circulation times, leading to faster clearance of exogenous drugs. This relationship does not hold true for all classes of drugs, however, especially those that are subject to complex metabolism (Lin, 1998).

MDMA is extensively metabolized in humans, as depicted in Fig. 5, and the major pathway of biotransformation involves: (1) O-demethylenation catalyzed by cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) and (2) O-methylation catalyzed by catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) (reviewed by de la Torre et al., 2004). CYP2D6 and COMT are both polymorphic in humans, and differential expression of CYP2D6 isoforms leads to interindividual variations in the metabolism of 5-HT medications (e.g., SSRIs) (Charlier et al., 2003). Interestingly, CYP2D6 is not present in rats, which express a homologous but functionally distinct cytochrome P450 2D1 (Malpass et al., 1999; Maurer et al., 2000). A minor pathway of MDMA biotransformation in humans involves 𝒩-demethylation of MDMA to form MDA, which is subsequently O-demethylenated and O-methylated. 𝒩-Demethylation of MDMA represents a more important pathway for rats when compared to humans (de la Torre et al., 2004). The metabolism of MDMA and MDA generates a number of metabolites, some of which may be bioactive (e.g., Escobedo et al., 2005; Forsling et al., 2002). Determining the potential neurotoxic properties of the various metabolites of MDMA is an important area of research (reviewed by Baumgarten and Lachenmayer, 2004; Monks et al., 2004).

FIG. 5.

Metabolism of MDMA in humans. The main cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoforms responsible for particular biotransformation reactions are indicated in italics. Thick arrows highlight major pathways, whereas thin arrows represent minor pathways.

To complicate matters further, de la Torre et al. (2000) have shown that MDMA displays nonlinear kinetics in humans such that administration of increasing doses, or multiple doses, leads to unexpectedly high plasma levels of the drug. Enhanced plasma and tissue levels of MDMA are most likely related to autoinhibition of MDMA metabolism, mediated via formation of a metabolite–enzyme complex that irreversibly inactivates CYP2D6 (Wu et al., 1997). Because MDMA displays nonlinear kinetics, repeated drug dosing could produce serious adverse consequences due to unusually high blood and tissue levels of the drug (Parrott, 2002; Schifano, 2004). The existing database of MDMA pharmacokinetic studies represents a curious situation where clinical findings are well documented, while preclinical data are lacking. Specifically, only a handful of animal studies have assessed the relationship between pharmacodynamic effects of MDMA and pharmacokinetics of the drug after administration of single or repeated doses (Chu et al., 1996; Mechan et al., 2006). Few studies have systemically characterized the nonlinear kinetics of MDMA in animal models (Mueller et al., 2008). Collectively, the available data demonstrate that potential species differences in tissue drug uptake, variations in metabolic enzymes and their activities, and the phenomenon of nonlinear kinetics, preclude the use of allometric scaling to extrapolate MDMA doses across different species.

The uncertainties and limitations of allometric scaling led us to investigate the method of “effect scaling” as an alternative strategy for matching equivalent doses of MDMA in rats and humans (see Winneke and Lilienthal, 1992). In this approach, the lowest dose of drug that produces a specific pharmacological response is determined for rats and humans, and subsequent dosing regimens in rats are calculated with reference to the predetermined threshold dose. In the case of MDMA, this strategy is simplified because CNS drug effects, such as neuroendocrine and behavioral changes, have already been investigated in different species. Theoretically, equivalent drug effects in vivo should reflect similar drug concentrations reaching active sites in tissue, suggesting the method of effect scaling can account for differences in drug absorption, distribution and metabolism across species (at least for low drug doses). Table III shows the doses of MDMA that produce comparable CNS effects in rats and humans. Remarkably, the findings reveal that MDMA doses in the range of 1–2 mg/kg produce pharmacological effects that are equivalent in both species. It is noteworthy that MDMA is typically administered to rats via the i.p. or s.c. route whereas humans take the drug orally. Given the similar effects of MDMA in rats and humans at the same doses, it appears that drug bioavailability is comparable after i.p., s.c., or oral administration (e.g., Finnegan et al., 1988), but verification of this hypothesis awaits further investigation.

TABLE III.

Comparative Neurobiological Effects of (±)-MDMA Administration in Rats and Humans

| CNS effect | Dose in rats | Dose in humans |

|---|---|---|

| In vivo release of 5-HTand DA | 2.5 mg/kg, i.p. (Gudelsky and Nash, 1996); 1 mg/kg, s.c. (Kankaanpaa et al., 1998) | 1.5 mg/kg p.o. (Liechti et al., 2000; Liechti and Vollenweider, 2001)a |

| Secretion of prolactin and glucocorticoids | 1–3 mg/kg, i.p. (Nash et al., 1988) | 1.67 mg/kg, p.o. (Mas et al., 1999); 1.5 mg/kg, p.o. (Harris et al., 2002) |

| Drug discrimination | 1.5 mg/kg, i.p. (Oberlender and Nichols, 1988; Schechter, 1988) | 1.5 mg/kg, p.o. (Johanson et al., 2005) |

| Drug reinforcement | 1 mg/kg, i.v. (Wakonigg et al., 2003) | 1–2 mg/kg, p.o. (Tancer and Johanson, 2003)b |

Subjective effects were attenuated by 5-HT uptake blockers, suggesting the involvement of transporter-mediated 5-HT release.

Reinforcing effects were determined based on a multiple choice procedure.

Administration of MDMA at i.p. doses of 1–3 mg/kg causes marked elevations in extracellular 5-HT and DA in rat brain, as determined by in vivo micro-dialysis (Baumann et al., 2005; Gudelsky and Nash, 1996; Kankaanpaa et al., 1998). Recall the data from Fig. 2 which demonstrate that 1 mg/kg i.v. MDMA increases extracellular 5-HT and DA rat n. accumbens. Although it is impossible to directly measure 5-HT and DA release in living human brain, clinical studies indicate that subjective effects of recreational doses of MDMA (1.5 mg/kg, p.o.) are mediated via transporter-mediated release of 5-HT (Liechti and Vollenweider, 2001; Liechti et al., 2000). Nash et al. (1988) showed that i.p. injections of 1–3 mg/kg of MDMA stimulate prolactin and corticosterone secretion in rats, and similar oral doses increase plasma prolactin and cortisol in human drug users (Harris et al., 2002; Mas et al., 1999). The dose of MDMA discriminated by rats and humans is identical: 1.5 mg/kg, i.p., for rats (Glennon and Higgs, 1992; Oberlender and Nichols, 1988; Schechter, 1988) and 1.5 mg/kg, p.o., for humans (Johanson et al., 2005). A few studies have shown that rats will self-administer MDMA at doses ranging from 0.25 to 1.0 mg/kg i.v., indicating these doses possess reinforcing efficacy (Ratzenboeck et al., 2001; Schenk et al., 2003). Wakonigg et al. (2003) demonstrated that a single i.v. injection of 1 mg/kg MDMA serves as a powerful reinforcer in an operant runway procedure, and MDMA displays similar reinforcing potency in Sprague–Dawley and Long–Evans rat strains. Tancer and Johanson (2003) reported that 1 and 2 mg/kg of MDMA have reinforcing properties in humans which resemble those of (+)-amphetamine. The findings summarized in Table III suggest there is no scientific justification for using allometric scaling to “adjust” MDMA doses between rats and humans.

Based on this analysis, we devised an MDMA dosing regimen in rats which attempts to mimic binge use of MDMA in humans. Male Sprague–Dawley rats were double-housed in plastic cages, under conditions of constant ambient temperature (22 °C) and humidity (70%) in a vivarium. In our most recent studies, three i.p. injections of 1.5 or 7.5 mg/kg MDMA were administered, one dose every 2 h, to yield cumulative doses of 4.5 or 22.5 mg/kg (Baumann et al., 2008a). Control rats received saline vehicle according to the same schedule. Rats were removed from their cages to receive i.p. injections, but were otherwise confined to their home cages. The 1.5 mg/kg dose was used as a low “behavioral” dose whereas the 7.5 mg/kg dose was used as a high “toxic” dose (i.e., a dose fivefold greater than threshold). Our repeated dosing regimen was designed to account for the common practice of sequential dosing (i.e., “bumping”) used by humans during rave parties (Parrott, 2002). During the binge dosing procedure, body temperatures were measured by a rectal thermometer probe, and 5-HT-mediated behaviors were scored for 6 h after the first dose. Rats were decapitated 2 weeks after dosing, brain regions were dissected, and tissue levels of 5-HT and DA were determined by HPLC-ECD as described previously (Baumann et al., 2001).

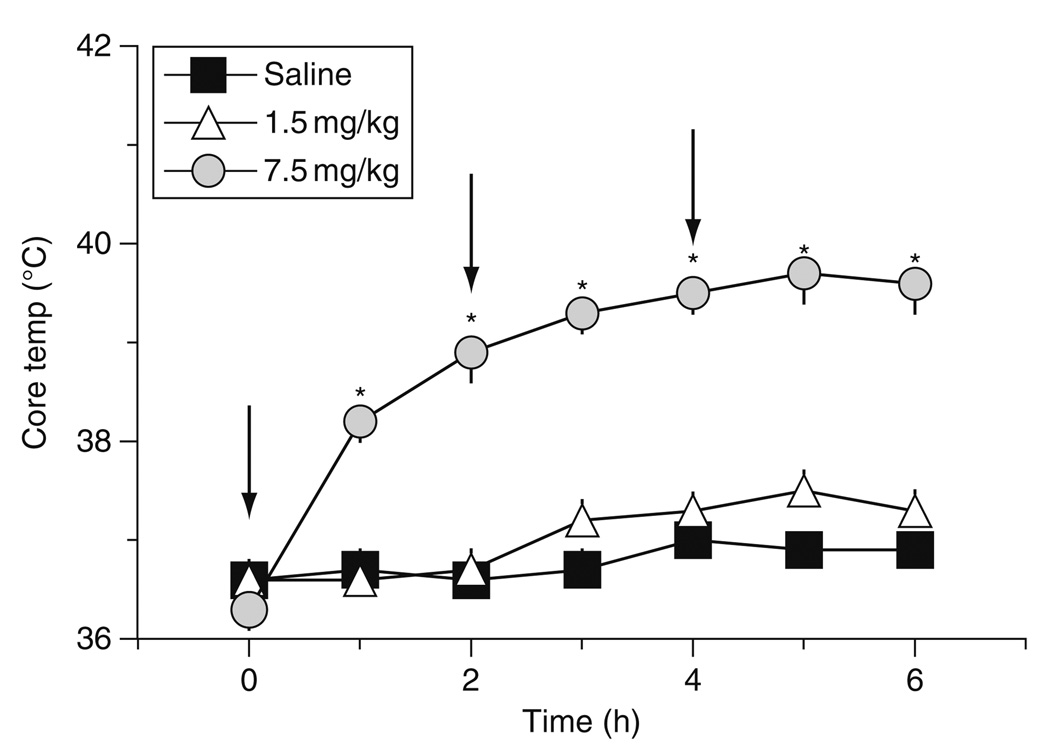

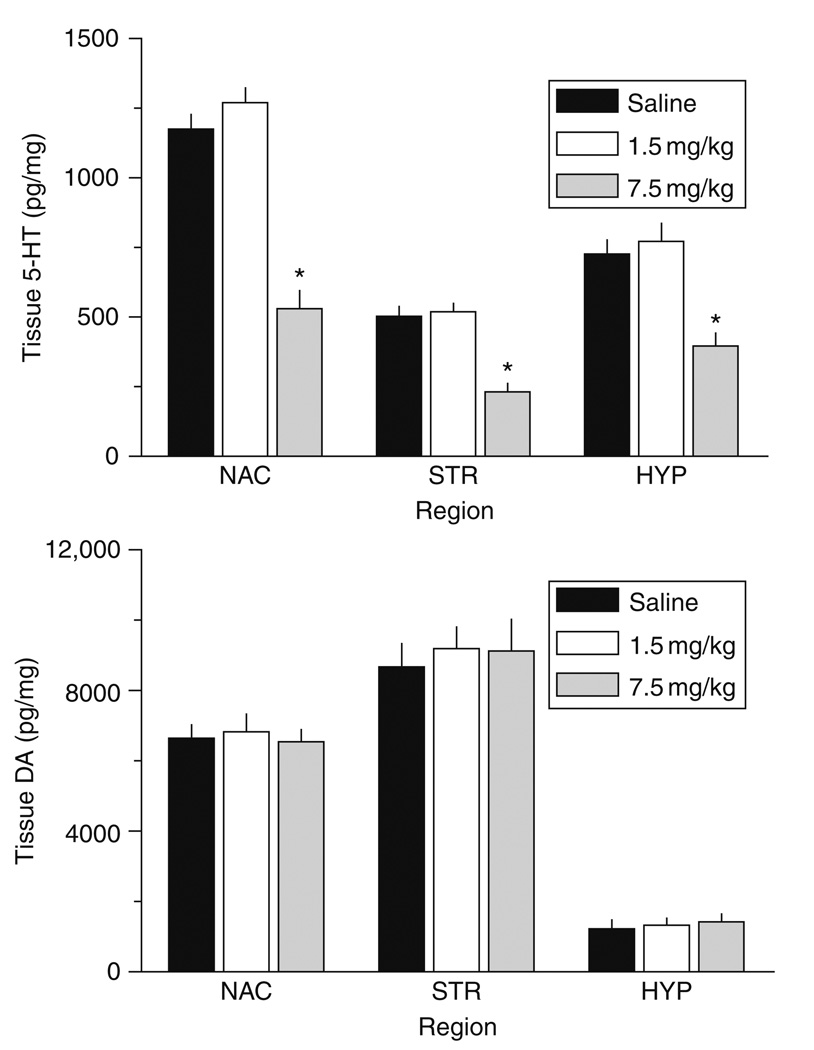

Figure 6 demonstrates that our binge MDMA dosing regimen increases core body temperature in rats [F2,105 = 218.11, P < 0.0001]. Specifically, repeated i.p. doses of 7.5 mg/kg MDMA elicit persistent hyperthermia on the day of treatment, whereas doses of 1.5 mg/kg do not. The 7.5 mg/kg dose causes temperature increases which are about 2 °C above normal, and such elevations are present for at least 6 h. The data in Fig. 7 demonstrate that binge MDMA treatment significantly decreases tissue 5-HT levels in the n. accumbens [F2,17 = 50.52, P < 0.0001], striatum [F2,17 = 25.49, P < 0.001], and mediobasal hypothalamus [F2,17 = 14.31, P < 0.0001] when assessed 2 weeks later. Post hoc tests reveal that high-dose MDMA produces long-term depletions of tissue 5-HT (~50% reductions) in all three regions examined, but the low-dose group has 5-HT concentrations similar to saline controls. Transmitter depletion is selective for 5-HT neurons since tissue DA levels are unaffected. The magnitude of 5-HT depletions depicted in Fig. 7 is similar to that observed by others (Battaglia et al., 1987; Schmidt, 1987; Stone et al., 1987).

FIG. 6.

Effects of MDMA binge administration on body temperature in rats. Male rats received three i.p. injections of saline, 1.5 mg/kg (low dose) or 7.5 mg/kg MDMA (high dose); injections were given at time 0, 2, and 4 h. Core body temperature was monitored hourly via insertion of a rectal temperature probe. Data are degrees Celsius expressed as mean ± S.E.M. for 𝒩 = 6 rats/group. *P < 0.05 compared to saline control at a given time point.

FIG. 7.

Effects of MDMA binge administration on tissue levels of 5-HT (top panel) and DA (bottom panel) in microdissected rat brain regions. Male rats received three i.p. injections of saline, 1.5 mg/kg (low dose) or 7.5 mg/kg MDMA (high dose). Rats were decapitated 2 weeks later, and tissue was dissected from n. accumbens (NAC), striatum (STR) and mediobasal hypothalalmus (HYP). Postmortem concentrations of 5-HT and DA were quantified by HPLC-ECD. Data are pg/mg wet weight expressed as mean ± S.E.M. for 𝒩 = 6 rats/group. *P < 0.05 compared to saline control for a specified brain region.

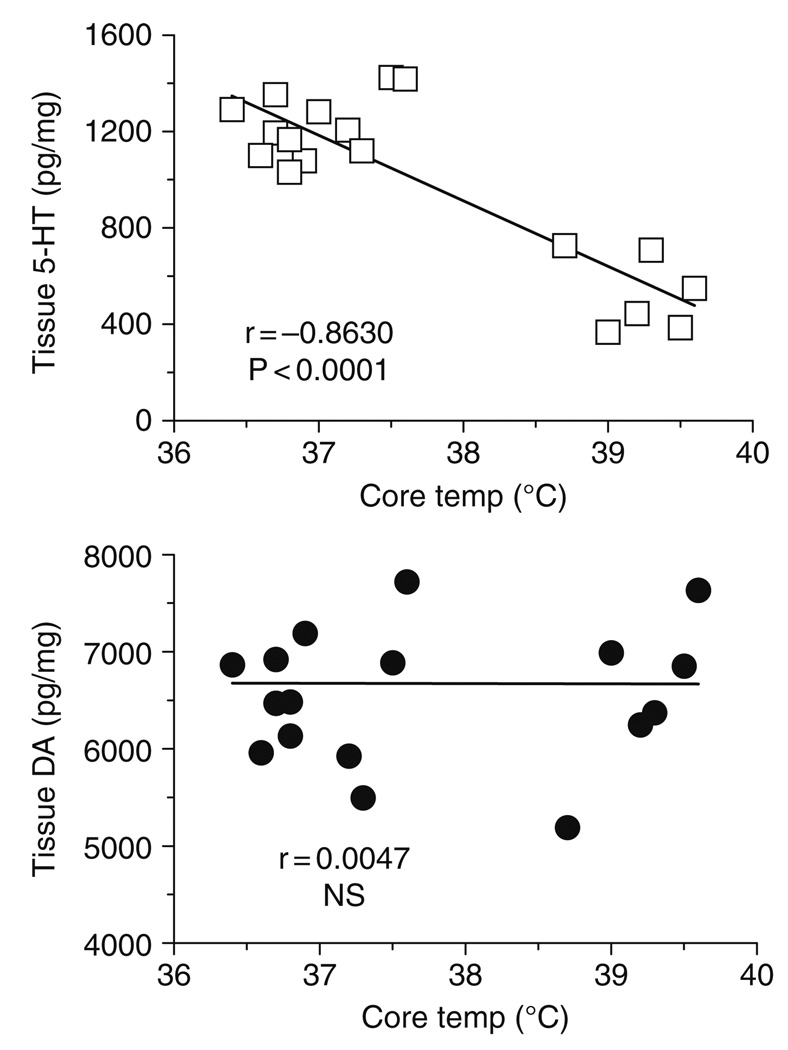

Given that high-dose MDMA binges cause acute hyperthermia and long-term 5-HT depletions in the same rats, we examined the relationship between body temperature and postmortem tissue monoamines using Pearson correlation analysis. We found that body temperature is negatively correlated with tissue 5-HT in the n. accumbens (r = −0.8630, P < 0.0001), striatum (r = −0.8089, P < 0.0001), and hypothalamus (r = −0.6910, P < 0.001). There are no significant correlations between body temperature and tissue DA. Figure 8 shows representative data from the n. accumbens, where MDMA-induced elevations in core temperature are significantly correlated with depletion of tissue 5-HT but not DA. Collectively, our findings demonstrate that repeated treatments with behaviorally relevant doses of MDMA do not cause acute hyperthermia or long-term 5-HT depletions. In contrast, repeated administration of MDMA at a dose which is fivefold higher than the behavioral dose causes both of these adverse effects. The degree of acute hyperthermia produced by MDMA appears to predict the extent of subsequent 5-HT depletion. Our findings are consistent with those of O’Shea et al. (1998) who reported that high-dose MDMA (10 or 15 mg/kg, i.p.), but not low-dose MDMA (4 mg/kg, i.p.), causes acute hyperthermia and long-term 5-HT depletion in Dark Agouti rats.

FIG. 8.

Correlations between acute body temperature versus postmortem tissue levels of 5-HT (top panel) and DA (bottom panel) in rat n. accumbens measured 2 weeks after MDMA administration. Body temperatures represent average values obtained from 1 to 6 h after MDMA or saline injections, as shown in Fig. 6. Postmortem tissue levels of 5-HT and DA were measured 2 weeks later by HPLC-ECD, as shown in Fig. 7. Data points represent average temperature versus tissue amine concentration from individual rats (𝒩 = 18 rats), and Pearson correlation coefficients (r) are given. (Modified from Baumann et al., 2008a).

V. Functional Consequences of MDMA-Induced 5-HT Depletion

Any definition of neurotoxicity must include the concept that functional impairments accompany neuronal damage (Moser, 2000; Winneke and Lilienthal, 1992). As noted previously, high-dose MDMA causes persistent inactivation of tryptophan hydroxylase which leads to inhibition of 5-HT synthesis and loss of 5-HT (O’Hearn et al., 1988; Stone et al., 1987). Moreover, MDMA-induced reduction in the density of SERT binding sites leads to decreased capacity for 5-HT uptake in nervous tissue (Battaglia et al., 1987; Schmidt, 1987). Regardless of whether these 5-HT deficits reflect neurotoxic damage or long-term adaptations, such changes would be expected to have discernible in vivo correlates. Many investigators have examined functional consequences of high-dose MDMA administration, and a comprehensive review of this subject is beyond the scope of this review (reviewed by Cole and Sumnall, 2003; Green et al., 2003). The following discussion will consider long-term effects of MDMA (i.e., >1 week) on in vivo indicators of 5-HT function in rats as measured by electrophysiological recording, neuroendocrine secretion, microdialysis sampling, and specific behaviors. A number of key findings are summarized in Table IV. In general, few published studies have been able to relate the magnitude of MDMA-induced 5-HT depletion to the degree of specific functional impairment. Furthermore, MDMA administration rarely causes persistent changes in baseline measures of neural function, and deficits are most readily demonstrated by provocation of the 5-HT system by pharmacological (e.g., drug challenge) or physiological means (e.g., environmental stress).

TABLE IV.

Effects of (±)-MDMA Administration on Functional Indices of 5-HT Transmission in Rats

| CNS effect | Dosing regimen | Survival interval | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| No change in 5-HT cell firing | 20 mg/kg, s.c., twice daily, 4 days | 2 weeks | Gartside et al. (1996) |

| Changes in corticosterone and prolactin secretion | 20 mg/kg, s.c., single dose; 20 mg/kg, s.c. twice daily, 4 days | 2 weeks 4, 8, and 12 months | Poland et al. (1997) |

| Reductions in evoked 5-HT release in vivo | 20 mg/kg, s.c., twice daily, 4 days; 10 mg/kg, i.p., twice daily, 4 days | 2 weeks, 1 week | Series et al. (1994), Shankaran and Gudelsky (1999) |

| Increased anxiety-like behaviors | 5 mg/kg, s.c., 1 or 4 injections, 2 days; 7.5 mg/kg, s.c., twice daily, 3 days | 3 months; 2 weeks | McGregor et al. (2003), Morley et al. (2001),a Fone et al. (2002)a |

These investigators noted marked increases in anxiogenic behaviors in the absence of significant MDMA-induced 5-HT depletion in brain.

5-HT projections innervating the rat forebrain have cell bodies residing in the raphe nuclei (Steinbusch, 1981). These neurons exhibit pacemaker-like electrical activity which can be recorded using electrophysiological techniques (Aghajanian et al., 1978; Sprouse et al., 1989). Gartside et al. (1996) used extracellular recording methods to examine 5-HT cell firing in the dorsal raphe of rats previously treated with MDMA. Rats received two daily injections of 20 mg/kg, s.c. MDMA for 4 days and were tested under chloral hydrate anesthesia 2 weeks later. MDMA pretreatment had no effect on the number of classical or burst-firing 5-HT cells encountered during recording. Additionally, 5-HT cell firing rates and action potential characteristics were not different between MDMA- and saline-pretreated groups. These data show that 5-HT neurons and their firing properties are not altered after MDMA administration, and this agrees with immunohistochemical evidence demonstrating MDMA does not destroy 5-HT perikarya. The electrophysiological data from MDMA-pretreated rats differ from the findings reported with 5,7-DHT. In rats treated with i.c.v. 5,7-DHT, the number of classical and burst-firing 5-HT neurons is dramatically decreased in the dorsal raphe, in conjunction with a loss of 5-HT fluorescence (Aghajanian et al., 1978; Hajos and Sharp, 1996). Thus, 5,7-DHT produces reductions in 5-HT cell firing that are attributable to cell death, but MDMA does not.

5-HT neurons projecting from raphe nuclei to the hypothalamus provide stimulatory input for the secretion of adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) and prolactin from the anterior pituitary (Van de Kar, 1991). Accordingly, 5-HT releasers (e.g., fenfluramine) and 5-HT receptor agonists increase plasma levels of these pituitary hormones in rats and humans, while stimulating glucocorticoid secretion from the adrenals of both species (reviewed by Levy et al., 1994). Neuroendocrine challenge experiments have been used to demonstrate changes in serotonergic responsiveness in rats treated with MDMA (Poland, 1990; Poland et al., 1997; Series et al., 1995). In the most comprehensive study, Poland et al. (1997) examined effects of high-dose MDMA on hormone responses elicited by acute fenfluramine challenge. Male Sprague–Dawley rats received single s.c. injections of 20 mg/kg MDMA and were tested 2 weeks later. Prior MDMA exposure did not alter baseline levels of circulating ACTH or prolactin. However, in MDMA-pretreated rats, fenfluramine-induced ACTH secretion was reduced while prolactin secretion was enhanced. The MDMA dosing regimen caused significant depletions of tissue 5-HT in various brain regions, including hypothalamus. In a follow-up time-course study, rats received twice daily s.c. injections of 20 mg/kg MDMA for 4 days, and were challenged with fenfluramine (6 mg/kg, s.c.) at 4, 8, and 12 months thereafter. As observed in the single dose MDMA study, rats exposed to multiple MDMA doses displayed blunted ACTH responses and augmented prolactin responses to fenfluramine. Interestingly, the impaired ACTH response persisted for 12 months in MDMA-pretreated rats, even though tissue levels of 5-HT were not depleted at this time point. The data show that high-dose MDMA can cause functional abnormalities for up to 1 year, and changes in 5-HT responsiveness do not necessarily parallel the extent of recovery from 5-HT depletions in brain.

In our laboratory, we wished to further explore the long-term neuroendocrine consequences of MDMA exposure. Specifically, we wished to compare MDMA-induced hormone responses in rats pretreated with low- versus high-dose MDMA binges. Utilizing the MDMA dosing regimen described previously, male rats received three i.p. injections of 1.5 or 7.5 mg/kg MDMA, one dose every 2 h. Control rats received saline vehicle according to the same schedule. One week after MDMA binges, rats were fitted with indwelling jugular catheters under pentobarbital anesthesia. One week after surgery (i.e., 2 weeks after MDMA or saline), rats were brought into the testing room, and i.v. catheters were connected to extension tubes. Rats received i.v. injections of 1 mg/kg MDMA at time zero, followed by 3 mg/kg MDMA 60 min later. Blood samples were withdrawn via the catheters immediately before and at 15, 30, and 60 min after each dose of MDMA. Elements of the 5-HT syndrome, namely forepaw treading, flattened body posture, and head weaving, were scored during the blood sampling procedure. Plasma levels of prolactin and corticosterone were measured by double-antibody radioimmunoassay methods (Baumann et al., 1998, 2008a).

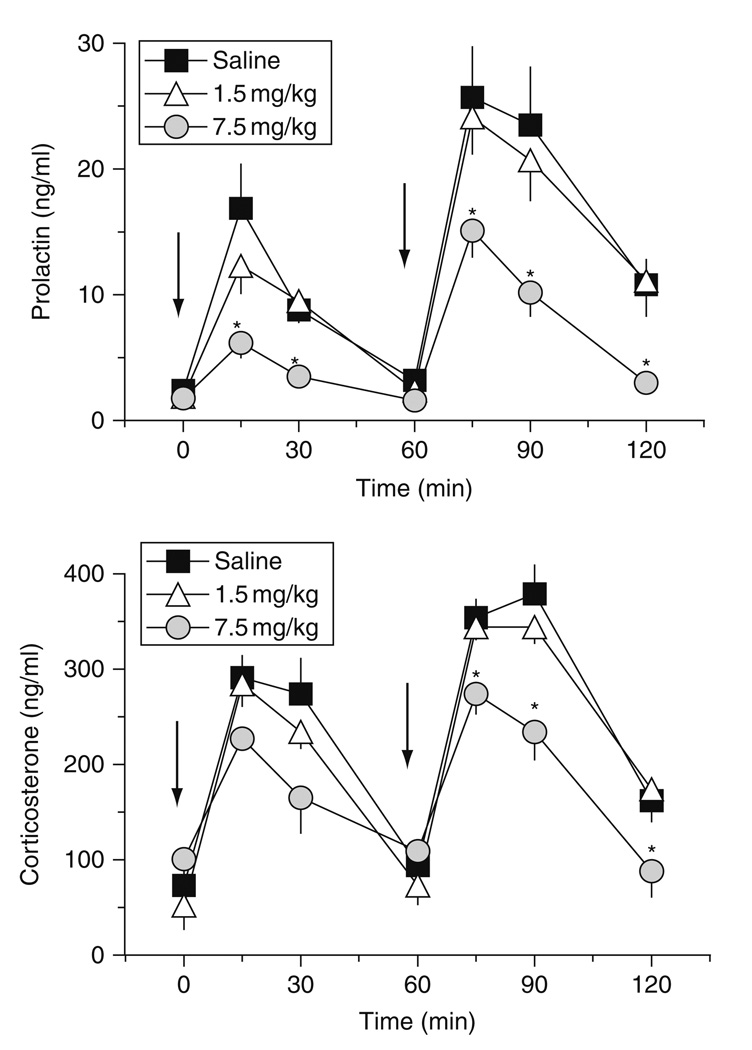

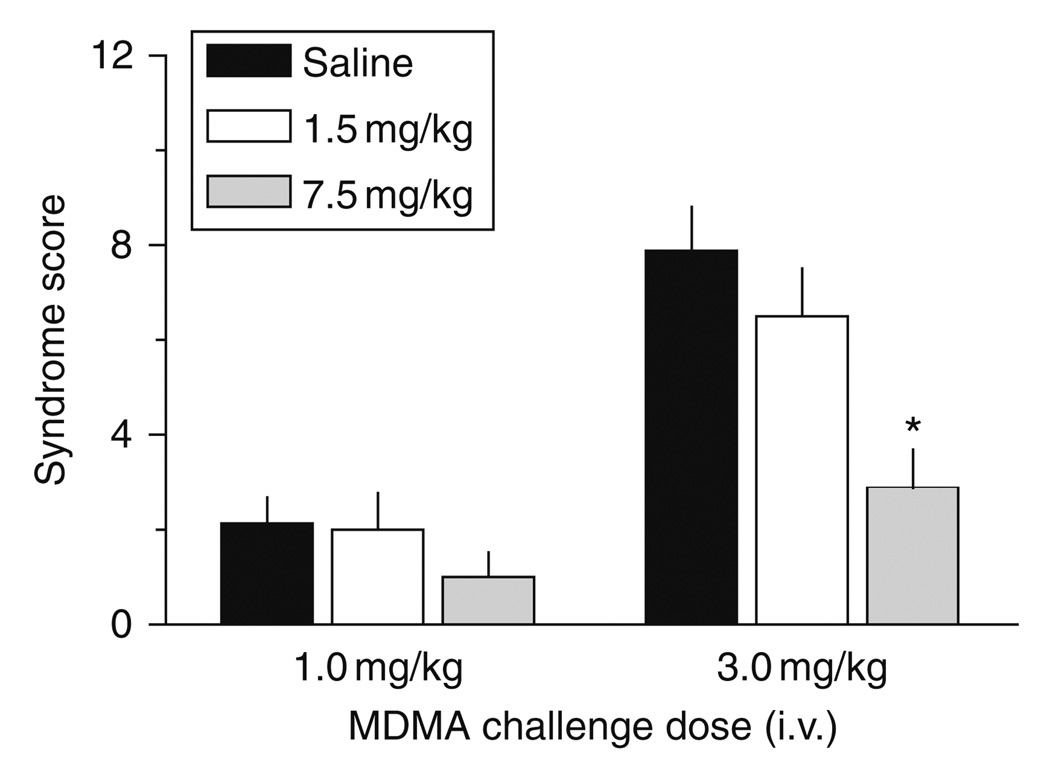

Figure 9 shows the effects of acute i.v. MDMA on prolactin and corticosterone secretion in rats exposed to MDMA binges. MDMA pretreatment does not alter baseline levels of either hormone. Acute i.v. administration of MDMA elicits dose-related elevations in circulating prolactin and corticosterone, in agreement with the findings of others who administered MDMA to rats via the i.p. route (Nash et al., 1988). Importantly, MDMA pretreatment significantly influences the magnitude of MDMA-induced prolactin [F2,147 = 21.03, P < 0.0001] and corticosterone [F2,147 = 12.20, P < 0.001] responses. Post hoc tests reveal that rats exposed to 7.5 mg/kg MDMA binges display reductions in prolactin and corticosterone secretion evoked by MDMA challenge. Blunted endocrine sensitivity is most severe for prolactin secretion, where responses in the high-dose binge group are about 50–60% lower than control responses. It is noteworthy that MDMA-induced endocrine secretion is similar between the low-dose binge group and saline-pretreated controls. Figure 10 shows the effects of MDMA challenge on 5-HT syndrome in rats previously exposed to MDMA binges. Acute i.v. MDMA produces robust 5-HT syndrome that is significantly affected by MDMA pretreatment [F2,42 = 8.15, P < 0.001]. Specifically, rats pretreated with high-dose binges display blunted syndrome scores after 3 mg/kg i.v. MDMA. Similar to the neuroendocrine findings, the behavioral effects of MDMA in the low-dose binge group are comparable to saline-pretreated controls.

FIG. 9.

Effects of i.v. MDMA on plasma concentrations of prolactin (top panel) and corticosterone (bottom panel) in rats pretreated with saline or MDMA binges. Male rats received three i.p. injections of saline, 1.5 mg/kg (low dose) or 7.5 mg/kg MDMA (high dose). Two weeks later, rats were given i.v. challenge injections of 1 mg/kg MDMA at time 0 h, followed by 3 mg/kg at 60 min. Blood samples were withdrawn immediately before and at 15, 30, and 60 min after each drug injection. Plasma hormones were assayed by double-antibody RIA methods. Data are ng/ml expressed as mean ± S.E. M. for 𝒩 = 8 rats/group. *P < 0.05 compared to saline-pretreated control at a given time point. (Modified from Baumann et al., 2008a).

FIG. 10.

Effects of i.v. MDMA on 5-HT behavioral syndrome in rats pretreated with saline or MDMA binges. Male rats received three i.p. injections of saline, 1.5 mg/kg (low dose) or 7.5 mg/kg MDMA (high dose). Two weeks later, rats were given i.v. challenge injections of 1 mg/kg MDMA at time 0 h, followed by 3 mg/kg at 60 min. The occurrence of flat-body posture and forepaw treading were scored after each dose of acute i.v. MDMA. Data are summed syndrome scores expressed as mean ± S.E.M. for 𝒩 = 8 rats/group. *P < 0.05 compared to saline-pretreated control at the corresponding challenge dose of MDMA. (Modified from Baumann et al., 2008a).

Our neuroendocrine and behavioral results are consistent with the development of tolerance to pharmacological effects of MDMA. The present endocrine data do not agree completely with the data of Poland et al. (1997); however, our findings do agree with previous data showing blunted hormonal responses to fenfluramine in rats previously treated with high-dose fenfluramine (Baumann et al., 1998). Perhaps more importantly, the data shown in Fig. 9 are strikingly similar to clinical findings in which cortisol and prolactin responses to acute (+)- fenfluramine administration are reduced in human MDMA users (Gerra et al., 1998, 2000; Gouzoulis-Mayfrank et al., 2002). Indeed, Gerra et al. (2000) reported that (+)-fenfluramine-induced prolactin secretion is blunted in abstinent MDMA users for up to 1 year after cessation of drug use. The mechanism(s) underlying reduced sensitivity to (+)-fenfluramine and MDMA are not known, but it is tempting to speculate that MDMA-induced impairments in evoked 5-HT release are involved. While some investigators have cited neuroendocrine changes in human MDMA users as evidence for 5-HT neurotoxicity, Gouzoulis-Mayfrank et al. (2002) provide a compelling argument that endocrine abnormalities in MDMA users could be related to cannabis use rather than MDMA. Further experiments will be required to resolve the precise nature of neuroendocrine changes in human MDMA users.

In vivo microdialysis allows continuous sampling of extracellular fluid from intact brain, and this method has been used to evaluate persistent neurochemical consequences of MDMA exposure (Gartside et al., 1996; Matuszewich et al., 2002; Series et al., 1994; Shankaran and Gudelsky, 1999). For example, Shankaran and Gudelsky (1999) assessed neurochemical effects of acute MDMA challenge in rats that had previously received four i.p. injections of 10 mg/kg MDMA. In vivo microdialysis was performed in the striatum of conscious rats 1 week after high-dose MDMA treatment. Baseline levels of dialysate 5-HT were not altered by prior MDMA exposure even though tissue levels of 5-HT in striatum were depleted by 50%. The ability of MDMA to evoke 5-HT release was severely impaired in MDMA-pretreated rats, while the concurrent DA response was normal. In this same study, effects of MDMA on body temperature and 5-HT syndrome were attenuated in MDMA-pretreated rats, suggesting the development of tolerance. Other investigations using in vivo microdialysis methods have shown that 5-HT release in response to physiological or stressful stimuli is impaired in rats pretreated with high-dose MDMA (Gartside et al., 1996; Matuszewich et al., 2002).

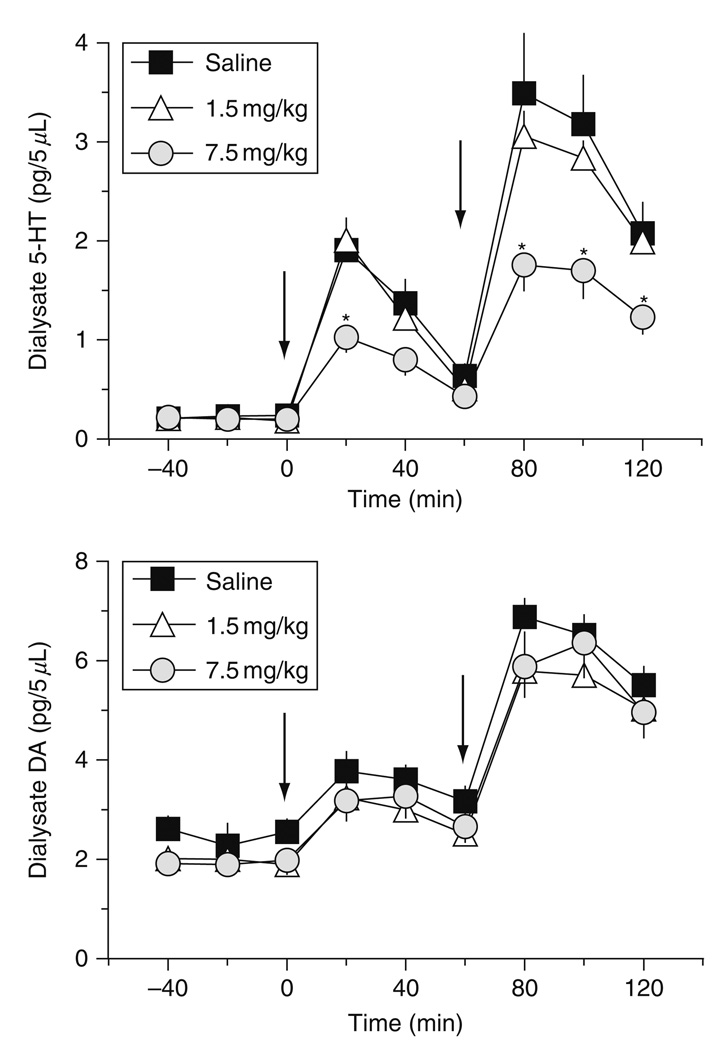

Based on our neuroendocrine and behavioral findings, we sought to evaluate whether MDMA tolerance might be reflective of neurochemical changes in the brain. To this end, we performed in vivo microdialysis in the n. accumbens and striatum of rats previously exposed to low- and high-dose MDMA binges. For these experiments, rats received three i.p. injections of 1.5 or 7.5 mg/kg MDMA, one dose every 2 h. Control rats received saline vehicle according to the same schedule. One week after MDMA binges, rats were fitted with indwelling jugular catheters and intracranial guide cannulae under pentobarbital anesthesia. Guide cannulae were aimed at the n. accumbens or striatum in separate groups of rats. One week after surgery (i.e., 2 weeks after MDMA or saline), rats were subjected to microdialysis testing. Dialysate samples were collected at 20 min intervals and assayed for 5-HT and DA by HPLC-ECD. After three baseline samples were obtained, rats received i.v. injections of 1 mg/kg MDMA at time zero, followed by 3 mg/kg MDMA 60 min later. Dialysate samples were collected until 1 h after the second dose of MDMA.

Figure 11 illustrates the effects of i.v. MDMA injections on 5-HT and DA release in the n. accumbens of rats previously exposed to MDMA binges. MDMA pretreatment does not affect baseline concentration of either transmitter. Acute i.v. MDMA produces dose-related elevations in dialysate 5-HT and DA, consistent with our prior findings (Baumann et al., 2005, 2007). However, MDMA pretreatment significantly affects dialysate 5-HT responsiveness [F2,161 = 22.95, P < 0.0001], with rats in the 7.5 mg/kg MDMA group displaying reductions in evoked 5-HTrelease. The magnitude of 5-HT responses in the high-dose MDMA group is about half that of responses in the saline-pretreated group at both challenge doses of MDMA. Rats in the 1.5 mg/kg MDMA group exhibit 5-HT release that is nearly identical to saline-pretreated controls. Interestingly, MDMA pretreatment has no effect on dialysate DA responsiveness. In this case, rats from all pretreatment groups exhibit similar DA release in response to MDMA challenge injections. Microdialysis findings from the striatum gave results analogous to those from n. accumbens. Namely, rats pretreated with high-dose MDMA binges have impairments in MDMA-induced release of 5-HT but not DA.

FIG. 11.

Effects of i.v. MDMA on dialysate 5-HT (top panel) and DA (bottom panel) in n. accumbens of rats pretreated with saline or MDMA binges. Male rats received three i.p. injections of saline, 1.5 mg/kg (low dose) or 7.5 mg/kg MDMA (high dose). Two weeks later, rats undergoing in vivo microdialysis were given i.v. challenge injections of 1 mg/kg MDMA at time 0 h, followed by 3 mg/kg at 60 min. Dialysate samples collected at 20 min intervals were assayed for 5-HT and DA by microbore HPLC-ECD. Data are pg/5 µl expressed as mean ± S.E.M. for 𝒩 = 8 rats/group. *P < 0.05 compared to saline-pretreated control at a given time point. (Modified from Baumann et al., 2008a).

Taken together with previous studies, our microdialysis data reveal important long-term consequences of MDMA administration: (1) baseline concentrations of dialysate 5-HT are not altered, despite profound depletions of tissue transmitter, (2) evoked 5-HT release is blunted in response to pharmacological or physiological provocation, (3) impairments in transmitter release are selective for 5-HT since evoked DA release is not affected, and (4) blunted 5-HT release may underlie tolerance to various pharmacological effects of MDMA. The dialysis findings with MDMA resemble those obtained from rats treated with 5-HT neurotoxin, 5,7-dihydroxytryptamine (5,7-DHT) (Hall et al., 1999; Kirby et al., 1995; Romero et al., 1998). In a representative study, Kirby et al. (1995) used microdialysis in rat striatum to evaluate the long-term neurochemical effects of i.c.v. 5,7-DHT. These investigators showed that impairments in stimulated 5-HT release and reductions in dialysate 5-HIAA are highly correlated with loss of tissue 5-HT, whereas baseline dialysate 5-HT is not. In fact, depletions of brain tissue 5-HT up to 90% did not affect baseline levels of dialysate 5-HT (Kirby et al., 1995). It seems that adaptive mechanisms serve to maintain normal concentrations of synaptic 5-HT, even under conditions of severe transmitter depletion. A comparable situation exists after lesions of the nigrostriatal DA system where baseline levels of extracellular DA are maintained in the physiological range despite substantial loss of tissue DA (see Zigmond et al., 1990). In the case of high-dose MDMA treatment, it seems feasible that reductions in 5-HT uptake (e.g., less functional SERT protein) and metabolism (e.g., decreased monoamine oxidase activity) compensate for 5-HT depletions in order to keep optimal concentrations of 5-HT bathing nerve cells. On the other hand, deficits in 5-HT release are readily demonstrated in MDMA-pretreated rats when 5-HT systems are taxed by drug challenge or environmental stressors. It is noteworthy that human MDMA users often report tolerance as a major side-effect of chronic drug use (Parrott, 2005; Verheyden et al., 2003). The rat data shown here suggest the possibility that MDMA tolerance in humans may reflect deficits in central 5-HT release mechanisms.

One of the more serious and disturbing clinical findings is that MDMA causes persistent cognitive deficits in some users (Morgan, 2000; Reneman, 2003). Numerous research groups have examined the effects of MDMA treatment on learning and memory processes in rats, yet most studies failed to identify persistent impairments—even when extensive 5-HT depletions were present (Byrne et al., 2000; McNamara et al., 1995; Ricaurte et al., 1993; Robinson et al., 1993; Seiden et al., 1993; Slikker et al., 1989). While a complete review of this literature is not possible, representative findings will be mentioned. In an extensive series of experiments, Seiden et al. (1993) evaluated the effects of high-dose MDMA on a battery of tests including open-field behavior, schedule-controlled behavior, one-way avoidance, discriminated two-way avoidance, forced swim, and radial maze performance. Male Sprague–Dawley rats received twice daily s.c. injections of 10–40 mg/kg MDMA for 4 days, and were tested beginning 2 weeks after treatment. Despite large depletions of brain tissue 5-HT, MDMA-pretreated rats exhibited normal behaviors in all paradigms. Likewise, Robinson et al. (1993) found that MDMA-induced depletion of cortical 5-HT up to 70% did not alter spatial navigation, skilled forelimb use or foraging behavior in rats. On the other hand, Marston et al. (1999) reported that MDMA administration produces persistent deficits in a delayed nonmatch to performance (DNMTP) procedure when long delay intervals are employed (i.e., 30 s). Specifically, saline-pretreated rats exhibited progressive improvement in task performance over successive days of testing, whereas MDMA-pretreated rats did not. The authors theorized that delay-dependent impairments in the DNMTP procedure reflect MDMA-induced deficits in short-term memory, possibly attributable to 5-HT depletion.

With the exception of the findings of Marston et al., the collective behavioral data in rats indicate that MDMA-induced depletions of brain 5-HT have little effect on cognitive processes. There are several potential explanations for this apparent paradox. First, high-dose MDMA administration produces only partial depletion of 5-HT in the range of 40–60% in most brain areas. This level of 5-HT loss may not be sufficient to elicit behavioral alterations, as compensatory adaptations in 5-HT neurons could maintain normal physiological function. Second, MDMA appears to selectively affect fine-diameter fibers arising from the dorsal raphe, and it is possible that these 5-HT circuits may not subserve the behaviors being monitored. Third, the behavioral tests utilized in rat studies might not be sensitive enough to detect subtle changes in learning and memory processes. Finally, the functional reserve capacity in the CNS might be sufficient to compensate for even large depletions of a single transmitter.

While MDMA appears to have few long-term effects on cognition in rats, a growing body of evidence demonstrates that MDMA administration can cause persistent anxiety-like behaviors in this species (Fone et al., 2002; Gurtman et al., 2002; Morley et al., 2001). Morley et al. (2001) first reported that MDMA exposure induces long-term anxiety in rats. These investigators gave male Wistar rats one or four i.p. injections of 5 mg/kg MDMA for 2 consecutive days. Subjects were tested 3 months later in a battery of anxiety-related paradigms including elevated plus maze, emergence and social interaction tests. Rats receiving either single or multiple MDMA injections displayed marked increases in anxiogenic behaviors in all three tests when compared to control rats. Because no 5-HT endpoints were examined, it was impossible to relate changes in behavior to changes in 5-HT transmission. In a follow-up study, Gurtman et al. (2002) replicated the original findings of Morley et al. using rats pretreated with four i.p. injections of 5 mg/kg MDMA for 2 days; persistent anxiogenic effects of MDMA were associated with depletions of 5-HT in the amygdala, hippocampus, and striatum. Interestingly, Fone et al. (2002) showed that twice daily injections of 7.5 mg/kg MDMA for 3 days caused impairments in social interaction in adolescent Lister rats, even in the absence of 5-HT depletions or reductions in [3H]-paroxetine-labeled SERT binding sites. These data suggested the possibility that MDMA-induced anxiety does not require 5-HT deficits.

In an attempt to determine potential mechanisms underlying MDMA-induced anxiety, McGregor et al. (2003) evaluated effects of the drug on anxiety-related behaviors and a number of postmortem parameters including autoradiography for SERT and 5-HT receptor subtypes. Rats received moderate (5 mg/kg, i.p., 2 days) or high (5 mg/kg, i.p., 4 injections, 2 days) doses of MDMA, and tests were conducted 10 weeks later. This study confirmed that moderate doses of MDMA can cause protracted increases in anxiety-like behaviors without significant 5-HT depletions. Furthermore, the autoradiographic analysis revealed that anxiogenic effects of MDMA may involve long-term reductions in 5-HT2A/2C receptors rather than reductions in SERT binding. Additional work by Bull et al. (2003, 2004) suggests that decreases in the sensitivity of 5-HT2A receptors, but not 5-HT2C receptors, could underlie MDMA-associated anxiety. Clearly, more investigation into this important area of research is warranted.

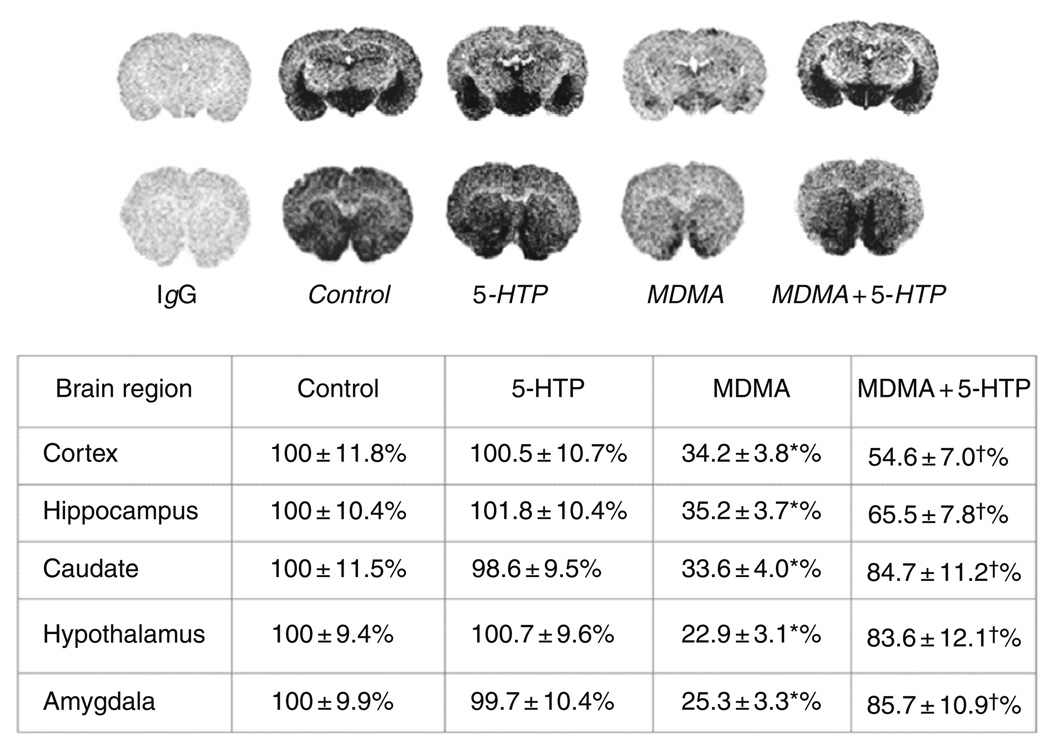

VI. Reversal of MDMA-Induced 5-HT Depletion by l-5-Hydroxytryptophan

As noted in Section I, accumulating evidence indicates that long-term MDMA abuse is associated with cognitive impairments and mood disturbances that can last for months after cessation of drug intake (Morgan, 2000; Parrott, 2002). There is speculation that psychological problems in MDMA users may result from 5-HT depletions in the CNS (McCann et al., 2008). To the extent that MDMA might produce 5-HT depletion in humans, one feasible approach for treatment would be to restore brain 5-HT by administration of the 5-HT precursor l-5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP). To test this idea, male Sprague–Dawley rats received three i.p. injections of 7.5 mg/kg MDMA or saline, one dose every 2 h (Wang et al., 2007). Two weeks later, rats received i.p. injections of saline or 5-HTP plus benserazide (5-HTP-B), each drug at 50 mg/kg. Rats were sacrificed 2 h after treatments. Benserazide is an inhibitor of aromatic acid decarboxylase which prevents peripheral conversion of 5-HTP to 5-HT, thereby facilitating entry of 5-HTP into the CNS. Previous studies show that a similar 5-HTP-B dosing regimen produces large increases in extracellular 5-HT in rat n. accumbens (Halladay et al., 2006). 5-HT concentrations in brain tissue sections were visualized using immunoautoradiography. As reported in Fig. 12, MDMA markedly decreases immunoreactive 5-HT in the caudate n. and hippocampus to about 35% of control. Under the same dosing conditions, SERT binding in these brain regions is reduced by nearly 90%. Importantly, administration of 5-HTP-B to MDMA-pretreated rats significantly increases the 5-HTsignal toward normal levels in caudate (85% of control) and hippocampus (66% of control). These experiments suggest that high-dose MDMA treatments leave 5-HT nerve terminals largely intact but emptied of endogenous 5-HT. Administration of the 5-HT precursor 5-HTP appears to “refill” empty nerve terminals, substantially restoring brain 5-HT levels. Our data suggest that precursor loading with 5-HTP might be a clinically useful approach to treatment in abstinent MDMA users who experience cognitive and psychiatric morbidity due to persistent 5-HT deficits (Thomasius et al., 2006). Future investigations should test the validity of this hypothesis in carefully controlled clinical studies.

FIG. 12.

Effects of MDMA on brain 5-HT as measured by immunoautoradiography. Male rats received three i.p. injections of saline or 7.5 mg/kg MDMA. Two weeks later, rats were treated with i.p. injections of either saline or 5-HTP/benserazide (5-HTP-B, 50 mg/kg of each drug), and were decapitated 2 h thereafter. 5-HT was measured by immunoautoradiography in postmortem brain sections. Values are mean ± S.D. for 𝒩 = 6 rats/group, and representative autoradiograms are shown. *P < 0.01 compared to control; +P < 0.01 compared to corresponding MDMA-treated group. Taken from Wang et al., 2007.

VII. MDMA and Valvular Heart Disease

Recent evidence indicates that MDA, the 𝒩-demethylated metabolite of MDMA, displays direct agonist actions at the 5-HT2B receptor subtype (Setola et al., 2003). This finding suggests that illicit MDMA use might increase the risk for VHD. Understanding the possible relationship between MDMA and VHD is best understood in the context of fenfluramine-associated valvulopathy. (±)-Fenfluramine, and its more potent enantiomer, (+)-fenfluramine, were commonly prescribed anorectic medications. These agents were removed from clinical use in 1997 due to the occurrence of VHD in some patients (Connolly and McGoon, 1999). Although a serotonergic mechanism was suspected as a possible cause of the VHD (Connolly et al., 1997), little was known about the pathogenesis of this adverse effect in the late 1990s. In light of the established role of 5-HT as a mitogen (Seuwen et al., 1988), we carried out an investigation to determine if isomers of fenfluramine or its metabolites (i.e., norfenfluramines), might activate a specific mitogenic 5-HT receptor subtype (Rothman et al., 2000). Drugs were tested for activity at various 5-HT receptor sites using high-throughput binding and functional assays. A number of additional test drugs were included in our study to provide both positive and negative controls. “Positive control” drugs included methysergide, its active metabolite methylergonovine (Bredberg et al., 1986) and ergotamine. Methysergide and ergotamine are known to produce left-sided VHD chiefly affecting the mitral valve (Bana et al., 1974; Hendrikx et al., 1996). “Negative control” drugs included phentermine, fluoxetine, and its metabolite norfluoxetine. These drugs interact with monoamine transporters but are not associated with VHD. Our working hypothesis was that “positive control” drugs would share in common the ability to activate a mitogenic 5-HT receptor expressed in heart valves, whereas “negative control” drugs would not.

An initial receptorome screen (Setola and Roth, 2005) led to a detailed evaluation of the binding of these drugs to the 5-HT2 family of receptors. Our data reveal that isomers of fenfluramine display low affinity for most 5-HT receptors. In contrast, isomers of norfenfluramine possess high affinity (𝒦I = 10–50 nM) for the 5-HT2B receptor subtype, confirming the findings of others (Fitzgerald et al., 2000; Porter et al., 1999). Moreover, functional studies demonstrate that norfenfluramines are full agonists at the 5-HT2B site. Positive control drugs such as ergotamine, methysergide, and methylergonovine are partial agonists at the 5-HT2B receptor, whereas negative control drugs are not. Taken together, our in vitro findings indicate that 5-HT2B receptors are involved in the valvulopathic effects of fenfluramine. Consistent with this hypothesis, 5-HT2B receptors are richly expressed on mitral and aortic valves (Fitzgerald et al., 2000), where they can stimulate mitogenisis (Lopez-Ilasaca, 1998).

The importance of 5-HT2B receptors in mediating drug-induced VHD is supported by recent data showing carbergoline and pergolide are potent agonists at this receptor site. Both of these medications are known to increase the risk of VHD (for review see Roth, 2007). As noted earlier, Setola et al. have reported that MDMA and MDA are 5-HT2B receptor agonists that elicit prolonged mitogenic responses in human valvular interstitial cells via activation of 5-HT2B receptors (Setola et al., 2003). The data summarized in Table V demonstrate that stereoisomers of MDA are particularly potent and efficacious agonists at the 5-HT2B site. The in vitro findings predict that MDMA abuse might cause VHD, similar to the effects of other known 5-HT2B agonists. Indeed, a recent clinical investigation reported that MDMA users have markedly increased valvular regurgitation compared to normal control subjects (Droogmans et al., 2007). The severity of regurgitation was directly related to the amount of MDMA consumed, indicating a dose-related increase in the risk for VHD. Additional studies will be needed to confirm and extend these important clinical observations.

TABLE V.

Potency (pEC50) and Efficacy of MDMA and MDA for Activation of 5-HT2B-Mediated PI Hydrolysis

| Test drug | pEC50 for 5-HT2B-mediated PI hydrolysis (nM) |

Efficacy for 5-HT2B-mediated PI hydrolysis (relative to 5-HT) |

|---|---|---|

| 5-HT | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| (±)-MDMA | 2000 | 0.32 |

| (+)-MDMA | 900 | 0.27 |

| (−)-MDMA | 6000 | 0.38 |

| (±)-MDA | 190 | 0.80 |

| (+)-MDA | 150 | 0.76 |

| (−)-MDA | 100 | 0.81 |

| Fenfluramine | 400 | 0.13 |

| Norfenfluramine | 60 | 0.96 |

| Dihydroergotamine | 30 | 0.73 |

| Pergolide | 53 | 1.12 |

| Methysergide | 150 | 0.18 |

| Methylergonivine | 0.8 | 0.40 |

Data are mean values for 𝒩 = 3 experiments. Data taken from Setola et al. (2003).

VIII. Summary

The findings reviewed in this chapter allow a number of conclusions to be drawn with regard to MDMA-induced toxic effects. First, MDMA produces pharmacological actions at the same doses in rats and humans (e.g., 1–2 mg/kg), which argues against the arbitrary use of allometric scaling to adjust doses between these species. Second, high doses of MDMA that produce 5-HT depletions in rats are accompanied by impairments in evoked 5-HT release that are manifest as drug tolerance. The animal data indicate that tolerance in human MDMA users could reflect central 5-HT dysfunction, thereby contributing to dangerous dose escalation. Third, doses of MDMA that fail to cause 5-HT depletions in rats can produce persistent increases in anxiety-like behaviors, suggesting even moderate doses of the drug may pose risks. Finally, the agonist activity of MDA isomers at the 5-HT2B receptor subtype could be involved with the increased risk for VHD in heavy MDMA users. Future investigations are warranted to further elucidate the long-term effects of MDMA exposure on neural and cardiac function in humans.

Acknowledgments

This research was generously supported by the NIDA IRP. The authors are indebted to John Partilla, Chris Dersch, Mario Ayestas, Robert Clark, Fred Franken, and John Rutter for their expert technical assistance during these studies.

References

- Aghajanian GK, Wang RY, Baraban J. Serotonergic and non-serotonergic neurons of the dorsal raphe: Reciprocal changes in firing induced by peripheral nerve stimulation. Brain Res. 1978;153(1):169–175. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)91140-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bana DS, MacNeal PS, LeCompte PM, Shah Y, Graham JR. Cardiac murmurs and endocardial fibrosis associated with methysergide therapy. Am. Heart J. 1974;88:640–655. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(74)90251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banken JA. Drug abuse trends among youth in the United States. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2004;1025:465–471. doi: 10.1196/annals.1316.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankson MG, Cunningham KA. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) as a unique model of serotonin receptor function and serotonin-dopamine interactions. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001;297:846–852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia G, De Souza EB. Pharmacologic profile of amphetamine derivatives at various brain recognition sites: Selective effects on serotonergic systems. NIDA Res. Monogr. 1989;94:240–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia G, Yeh SY, O’Hearn E, Molliver ME, Kuhar MJ, De Souza EB. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine and 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine destroy serotonin terminals in rat brain: Quantification of neurodegeneration by measurement of [3H]paroxetine-labeled serotonin uptake sites. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1987;242:911–916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia G, Yeh SY, De Souza EB. MDMA-induced neurotoxicity: Parameters of degeneration and recovery of brain serotonin neurons. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1988;29:269–274. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann MH, Rutter JJ. Application of in vivo microdialysis methods to the study of psychomotor stimulant drugs. In: Waterhouse BD, editor. Methods in Drug Abuse Research, Cellular and Circuit Analysis. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2003. pp. 51–86. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann MH, Ayestas MA, Rothman RB. Functional consequences of central serotonin depletion produced by repeated fenfluramine administration in rats. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:9069–9077. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-09069.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann MH, Ayestas MA, Dersch CM, Rothman RB. 1-(m-Chlorophenyl) piperazine (mCPP) dissociates in vivo serotonin release from long-term serotonin depletion in rat brain. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;24:492–501. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann MH, Clark RD, Budzynski AG, Partilla JS, Blough BE, Rothman RB. N-substituted piperazines abused by humans mimic the molecular mechanism of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, or ‘Ecstasy’) Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30(3):550–560. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann MH, Wang X, Rothman RB. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) neurotoxicity in rats: A reappraisal of past and present findings. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2007;189(4):407–424. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0322-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann MH, Clark RD, Franken FH, Rutter JJ, Rothman RB. Tolerance to 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine in rats exposed to single high-dose binges. Neuroscience. 2008a;152(3):773–784. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann MH, Clark RD, Rothman RB. Locomotor stimulation produced by 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) is correlated with dialysate levels of serotonin and dopamine in rat brain. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2008b;90(2):208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgarten HG, Lachenmayer L. Serotonin neurotoxins—Past and present. Neurotox. Res. 2004;6(7–8):589–614. doi: 10.1007/BF03033455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benmansour S, Cecchi M, Morilak DA, Gerhardt GA, Javors MA, Gould GG, Frazer A. Effects of chronic antidepressant treatments on serotonin transporter function, density, and mRNA level. J. Neurosci. 1999;19(23):10494–10501. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-23-10494.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger UV, Gu XF, Azmitia EC. The substituted amphetamines 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, methamphetamine, p-chloroamphetamine and fenfluramine induce 5-hydroxytryptamine release via a common mechanism blocked by fluoxetine and cocaine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1992;215:153–160. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90023-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredberg U, Eyjolfsdottir GS, Paalzow L, Tfelt-Hansen P, Tfelt-Hansen V. Pharmacokinetics of methysergide and its metabolite methylergometrine in man. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1986;30:75–77. doi: 10.1007/BF00614199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull EJ, Hutson PH, Fone KC. Reduced social interaction following 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine is not associated with enhanced 5-HT 2C receptor responsivity. Neuropharmacology. 2003;44(4):439–448. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00407-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull EJ, Hutson PH, Fone KC. Decreased social behaviour following 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) is accompanied by changes in 5-HT2A receptor responsivity. Neuropharmacology. 2004;46(2):202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne T, Baker LE, Poling A. MDMA and learning: Effects of acute and neurotoxic exposure in the rat. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2000;66(3):501–508. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00227-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson A. The contribution of drug research to investigating the nature of endogenous depression. Pharmakopsychiatr. Neuropsychopharmakol. 1976;9(1):2–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlier C, Broly F, Lhermitte M, Pinto E, Ansseau M, Plomteux G. Polymorphisms in the CYP 2D6 gene: Association with plasma concentrations of fluoxetine and paroxetine. Ther. Drug Monit. 2003;25(6):738–742. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200312000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu T, Kumagai Y, DiStefano EW, Cho AK. Disposition of methylenedioxymethamphetamine and three metabolites in the brains of different rat strains and their possible roles in acute serotonin depletion. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1996;51(6):789–796. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)02397-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colado MI, O’Shea E, Green AR. Acute and long-term effects of MDMA on cerebral dopamine biochemistry and function. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2004;173(3–4):249–263. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1788-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole JC, Sumnall HR. The pre-clinical behavioural pharmacology of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2003;27(3):199–217. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commins DL, Vosmer G, Virus RM, Woolverton WL, Schuster CR, Seiden LS. Biochemical and histological evidence that methylenedioxymethylamphetamine (MDMA) is toxic to neurons in the rat brain. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1987;241(1):338–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly HM, McGoon MD. Obesity drugs and the heart. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 1999;24:745–792. doi: 10.1016/s0146-2806(99)90013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly HM, Crary JL, McGoon MD, Hensrud DD, Edwards BS, Schaff HV. Valvular heart disease associated with fenfluramine-phentermine. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997;337(9):581–588. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199708283370901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespi D, Mennini T, Gobbi M. Carrier-dependent and Ca(2+)-dependent 5-HT and dopamine release induced by (+)-amphetamine, 3,4-methylendioxymethamphetamine, p-chloroamphetamine and (+)-fenfluramine. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;121:1735–1743. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dafters RI. Hyperthermia following MDMA administration in rats: Effects of ambient temperature, water consumption, and chronic dosing. Physiol. Behav. 1995;58(5):877–882. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)00136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dafters RI, Lynch E. Persistent loss of thermoregulation in the rat induced by 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA or “Ecstasy”) but not by fenfluramine. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 1998;138(2):207–212. doi: 10.1007/s002130050664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Torre R, Farre M, Ortuno J, Mas M, Brenneisen R, Roset PN, Segura J, Cami J. Non-linear pharmacokinetics of MDMA (‘ecstasy’) in humans. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2000;49:104–109. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00121.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Torre R, Farre M, Roset PN, Pizarro N, Abanades S, Segura M, Segura J, Cami J. Human pharmacology of MDMA: Pharmacokinetics, metabolism, and disposition. Ther. Drug Monit. 2004;26(2):137–144. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200404000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doblin R. A clinical plan for MDMA (Ecstasy) in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): Partnering with the FDA. J. Psychoactive Drugs. 2002;34(2):185–194. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2002.10399952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Droogmans S, Cosyns B, D’Haenen H, Creeten E, Weytjens C, Franken PR, Scott B, Schoors D, Kemdem A, Close L, Vandenbossche JL, Bechet S, et al. Possible association between 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine abuse and valvular heart disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 2007;100(9):442–445. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]