Abstract

Objectives

We sought to understand how low-income urban mothers explain feelings of sadness, stress or demoralization in the context of their life experiences.

Methods

28 in-depth qualitative interviews, constituting part of a community-based participatory research (CBPR) project aimed at developing a culturally relevant, community-based intervention for maternal depression. Qualitative data validity was ensured through investigator and expert triangulation, and through member checking.

Results

The following themes emerged: 1) Informants spoke of wanting reprieves from chaos, and discussed this desire relative to wanting to be alone. By contrast, informants expressed loneliness not only in interpersonal terms, but also related to having problems that precluded future relationships, or feeling unique in experiencing an adversity. 2) Informants spoke of demoralization associated with feeling that their problems were externally imposed and therefore beyond their control, but spoke of empowerment associated with owning one’s problems. 3) Informants discussed degrees of sadness in relation to their own abilities to adjust or modify their mood, or their ability to contain their feelings.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that helping a mother find reprieves from chaos, increasing her perception of her own locus of control around externally imposed adversities, and empowering her to recognize and self-manage her own feelings may constitute important elements of a culturally relevant, community-based intervention for depression.

Keywords: depression, sadness, ethnographic interviews, qualitative research, vulnerable populations

Introduction

Among all major chronic conditions, depression causes the greatest decrement in health worldwide (1), and by 2020 is expected to be the second leading cause of disability (2). Community-based studies of low-income and minority women in the US estimate the prevalence of clinically significant depressive symptomatology to be between 16% and 48% (3–9). Maternal depression, specifically, impacts the children of affected women (10–14). Despite evidence-based strategies for treating depressed adults (15–22), engagement with care remains challenging (23, 24). Although recent evidence demonstrates that addressing maternal depression can ameliorate many of its adverse effects on children (25), the majority of depressed mothers – particularly racial and ethnic minorities, and those in poverty – fail to receive adequate care (26–30).

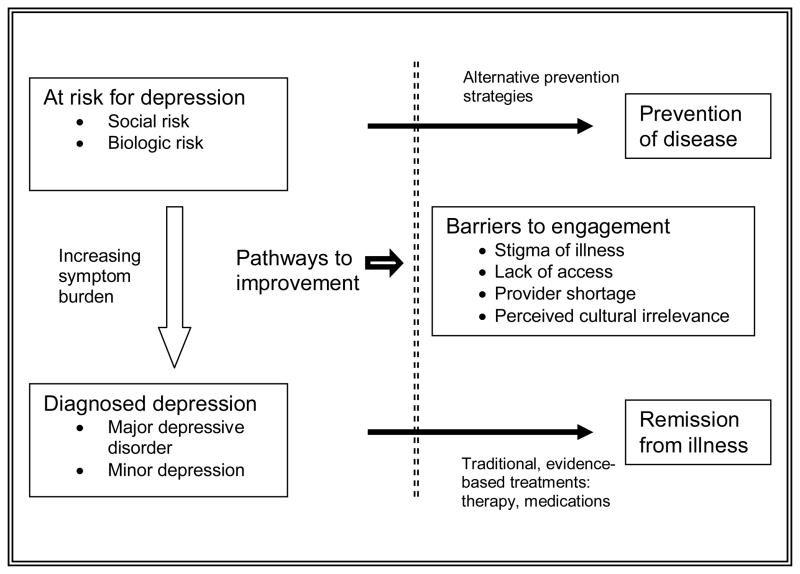

For these high risk populations, the barriers to quality mental health care are complex. The stigma of mental illness (31–33), conceptions of symptoms as unalterable manifestations of social adversity (34–37), and culturally aberrant ways in which healthcare is sometimes delivered (37, 38), have all been documented as barriers to engagement with services. Furthermore, widespread shortages of mental health professionals make engagement with care difficult even for those motivated to seek it ((30); Figure 1). For these reasons, the Institute of Medicine concluded in its report on reducing risks for mental disorders through prevention, that strategies for preventing depression in high risk populations may yield greater benefits than strategies for treating it (39). The following research is grounded in the premise that community-based approaches – which emphasize prevention and do not directly involve traditional systems of medical care – may hold promise to overcome many of these barriers.

Figure 1.

Framework for Barriers to Engagement with Mental Health Care

Progressive models of health service delivery emphasize the importance of community resources in promoting general health (40, 41). Such resources, some argue, are inherently more client-centered, culturally relevant and accessible than traditional health services (42). Many large scale community programs dedicated to maternal and child health, such as Head Start, Healthy Families, and the national Healthy Start Initiative have reported maternal depression as a major organizational concern and a potentially modifiable risk factor for suboptimal family health (4, 43, 44). At present, however, there is a paucity of data concerning evidence-based depression interventions being delivered by community – as opposed to professional – personnel.

This study, therefore, represents an initial step in a CBPR trajectory aimed at developing a community-based strategy to address depression among low-income mothers. Specifically, we aimed to learn how a community-based depression intervention may be aligned with how a group of women – as potential intervention recipients – explain sadness, stress or demoralization in the context of their life experiences. In addition to eliciting such explanations, we focused on what women did in terms of personal readjustments to feel less distressed or overwhelmed by their feelings. These specific research questions were designed to inform the development of culturally relevant and acceptable community-based intervention strategies.

Methods

Context and Qualitative Methodology

We conducted 28 in-depth qualitative interviews with low-income mothers in Boston, MA between November 2004 and May 2006. These interviews were part of a broader CBPR project aimed at designing and implementing a community-based prevention intervention for maternal depression. The premise underlying the broader project was that many factors impede the engagement of low-income women with traditional mental health services – one of which is the lack of perceived relevance of care. In the tradition of CBPR (45), we sought to address the issues of relevance and acceptability by giving voice to potential future intervention participants as a step toward intervention design.

The interviews, conducted in a focused ethnographic style, were guided by open-ended questions, examples of which included, “Please tell me about your family,” “What is a typical day like for you?” and “What are some of the things you like to do with your child?” Such questions were designed to encourage informants to open up and express their perceptions in their own terms, an accepted goal of ethnographic interviewing (46). Interviews lasted 45 to 90 minutes and were audiotaped and transcribed. The interviews were conducted by two of the authors (MS, SR), both of whom were trained in qualitative interviewing. An anthropologist unaffiliated with the project assessed samples of the tapes to assure appropriate interviewing technique.

Participants and recruitment

Participants were recruited from local Head Start or Healthy Families programs, or from the outpatient pediatric clinic of an urban safety net hospital with multiple community programs in place. These organizations were chosen because they were felt to represent potential venues for future intervention implementation. As is typical in qualitative research, our sampling scheme was nonrandom; rather, it aimed to cover a range of relevant perspectives from women of different cultures and thus maximize the variability in perspectives. Therefore, although our subjects were drawn from Head Start and Healthy Families, they were not meant to be proportionally representative of these organizations’ clientele. After agreeing on a research design with the directors of our partnering agencies, key personnel in each recruiting venue were given a brief overview of the study’s goals (i.e. to learn how mothers who are in distress think about their lives), and asked to recruit women for participation. Any mother or pregnant woman was eligible to participate, provided they were able to communicate with interviewers effectively in English.

Because prior research has documented Head Start and Healthy Families mothers as being at high risk for depression, we chose not to prescreen subjects with a conventional symptom inventory for depressive illness and risk equipping them with a biased vocabulary to explain their emotions. Similarly, we felt that conducting an interview on sadness and demoralization prior to administering a symptom inventory would bias responses to the latter. Because the broader goal of this research was to design community-based prevention strategies for depression, interviewers specifically probed for known risk factors for depressive illness, common to low-income urban families: family history of depression, violence victimization, single parenthood, having a sick child, and homelessness. These risk factors are communicated in the results section where appropriate.

Data analysis

The open-ended structure of our interviews permitted investigators to explore findings without imposing conventional biomedical constructs of depression. Data derived from earlier time points were discussed and used to adapt interview questions in an iterative fashion as the study proceeded (47). To maximize the reliability of the analysis, investigators reviewed each transcript independently. The authors then met to discuss tentative themes and translate the tentative themes into codes. The authors then independently coded the transcripts and convened to assure uniform coding of each; disagreements were resolved through discussion; coded transcripts were sorted into code-specific passages through the use of the Hyperresearch software package (Randolph, MA). Each coded passage was then re-read by three of the authors (MS, KD JL), analyzed for connection to other passages, and ultimately categorized into final themes.

Data credibility and corroboration of findings

Data collection ended when the authors recognized that a set of recurrent themes was identified and no new themes in this regard were evident (thematic saturation). We employed three, previously described techniques to ensure data validity (48, 49). 1) Investigator triangulation: a multidisciplinary team of investigators analyzed the raw data independently and met to ensure consensus prior to proceeding to each subsequent analysis step. 2) Expert triangulation: investigators convened three meetings in which the study’s methodology, coding scheme, and results were presented to health services researchers, child development specialists, and psychiatrists; and 3) Member checking: results were shared with a subset of study subjects who had given permission to be contacted for this purpose.

Human subjects

This study was approved by the Boston University Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Results

Population

We conducted 28 interviews: 27 with mothers; one with an expectant mother. Subjects ranged in age from 19 to 43 years. All had incomes at or below the federal poverty level, and all had completed at least some high school. The study population was of mixed racial and ethnic background; of those not born in the United States, countries of origin included China, Japan, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Zambia.

Reliability of Findings

Interviews conducted by the two interviewers were compared, and no systematic differences were discernable. Although the expert triangulation meetings helped investigators define their themes more specifically, themes did not change based on these meetings. After conducting member checking sessions with five informants, during which no changes were made to study findings, the investigators decided that additional sessions were unnecessary.

Major Theme 1: Aloneness versus loneliness

Approximately half of our respondents discussed either their feeling of loneliness or state of aloneness in relation to their sadness. Whereas loneliness was always associated with sadness, emptiness or demoralization, aloneness was often described in terms of wanting a reprieve from chaos (¶1).

¶1 It’s been very hard. I’m not the kind of person that really asks for help much. So if I’m having a problem with something, then I probably just deal with it on my own. And if I’m stressed out, then I separate myself. And I used to do that before I had her [her daughter], so it’s just a habit. If I’m upset or mad about something, I’ll go away or something. I’ll leave town or I’ll just separate myself from whatever – from everybody. And it does good because when I come back, I miss everybody, and my attitude’s better.

Relative to the desire to be alone, informants commonly discussed negative experiences with partners or parents who added to the stress of their lives (¶2). Specifically, some informants discussed a “default” pathway in their lives towards tolerability, which was made intolerable by the presence of these people. The desire for aloneness sometimes took the form of wanting to return to a normative – or tolerable – life without extraordinary stressors.

¶2 I do bad by myself, but with him it’s worse. Like when I’m with him, all of my money like he’ll take my money, I’ll end up like more than broke. When it’s just me, at least I can pay the bills. When it’s him too, I can’t even pay the bills, I get behind on the bills, so it’s ridiculous.

A few of our informants discussed aloneness or loneliness in terms related to freedom or captivity – the former, more congruent with aloneness; the latter, with loneliness. The woman below, who had once been homeless (and was seeing a counselor at the time of the interview), explained her loneliness relative to being controlled, or held captive, by her husband (¶3).

¶3 Like I feel depressed because I didn’t have any family here. I know only him [the husband]. Only him. All the information, only from him. So I couldn’t see what’s going on in here. It was like so – you feel lonely and scary for future. What is going to happen next? I still have a big responsibility for taking care of my baby and my husband. Only I have to carry it all myself. I don’t have any partner, anyone to share with to take care of my daughter. That was a big part too. I was depressed.

In addition to the interpersonal type of loneliness expressed above, our informants related two additional types: an experiential loneliness, in which they perceived that they were the only ones experiencing a certain adversity (“…sometimes you feel like you’re all alone. But when you see other [adolescent] parents, you feel a little bit better that I know at least that I’m not going through this by myself”); and an existential loneliness, in which they perceived that their present circumstances precluded future relationships (¶4). The following woman reflected on being an adolescent parent.

¶4 Because you’re just like, who’s going to want to marry you if you have a baby and you know, and you feel like bad. Who’s going to want to be with me. I already have a baby. Nobody’s going to want to take – who’s going to want – and if they do want to, are they really going to love [son’s name]?

Major Theme 2: Externally imposed circumstances versus self-determination

A second major theme focused on the difference between feeling that one’s adversities were externally imposed, versus feeling that one had played a role in either creating or solving them. Among virtually all our informants, the perceived loss of control over one’s life circumstances was perceived as demoralizing. The following informant, an adolescent parent with a history of homelessness and diagnosed depression, referred to the following specific scenario of how living in a shelter imposed specific restrictions on other opportunities in her life (¶5).

¶5: This semester, I screwed up. I thought I could do it. I was in the shelter. I couldn’t do anything, just concentrate get housing. And in September, that lady called me and said, I have an apartment in September. And school start in September. That means I can go. Because in the shelter, I can’t go to a 4-year college…They don’t let you stay in the shelter if you go to a 4 year college; they kick you out. I said oh God, give me a chance that I can go to school.

By contrast, perceiving control – or taking control – over one’s circumstances was typically seen as an act of empowerment that served to alleviate sadness or positively reframe one’s experience of adversity (¶6). The following informant was a victim of sexual abuse.

¶6: I was on the train, and I look over and there’s my grandmother, the one that I lived with when I got sexually abused because they were so pissed that I had said something…And like I saw her, and I was like oh my God, it’s just like very awkward. That was like-I mean, I don’t know, I just felt safe in some weird way. I knew they-she couldn’t yell at me, I knew she couldn’t say anything to me. And if she did, I could just walk away from her. Life seems a lot easier now. It’s very-I like being an adult.

Taking control of one’s circumstances meant not only working to solve one’s problems or overcome them, but also acknowledging previous errors in judgment, or assuming ownership or responsibility for one’s problems. When informants endorsed an ownership of their own problems, such an endorsement was nearly always associated with positive feelings of self-efficacy, pride or personal empowerment (¶7).

¶7: But I love my family though. I love them, though at the same time I want to kill them which I won’t do. It’s my family. They are so not supportive. They will talk, tell you what to do. They would just be like. Alright when I had my son, I had my son at 15. Yes, I was not ready to be a mother, but I accepted the responsibility. Then they start talking all this nonsense. Oh this and that. I would rather go to someone outside then go to them to ask them anything. It’s not that I can’t count on them, but I know it’s the trash that they’re going to be talking afterwards.

Major Theme 3: Sadness related to an individual’s ability to adjust her own mood

Informants often discussed sadness in relation to their own ability to adjust to their mood. These adjustments occurred primarily through personal coping mechanisms such as engaging in pleasant activities, finding brief reprieves from chaos, or interacting positively with other adults. On the mild end of a severity spectrum, informants related the ability to engage in – and the success of – activities to alleviate sadness. In the middle of the spectrum, informants endorsed an ability to attempt such activities, but perceived the attempts as unsuccessful. On the severe end, informants lost the ability to even attempt to make themselves feel better, and as a result felt stuck or hopeless.

The effectiveness of minor readjustments

Many of our informants spoke about small, personal interventions they would attempt to deal with their feelings. Such interventions (playing sports, praying, visiting friends) were often perceived as preventing a slide into a more severe form of sadness or demoralization. When these strategies fulfilled their intended purpose, informants tended to conceptualize their sadness as an entity to be dealt with, or to fight against - and themselves, as active participants in managing their own feelings (¶8).

¶8: I just continue to stay focused. I keep myself busy and stuff. I go play basketball. I like playing basketball. So if I feel down, I just go and play a game of basketball, come play with him [her child], and just forget about, keep going. You gotta be strong though because it’s so easy to just fall into it, fall into that mold, just like, I don’t care no more, like whatever. You don’t even care about nothing. It’s so easy to pick up that attitude because so many people have it. There’s so much bad stuff around you it’s like, you just gotta keep going.

By contrast, many informants related less successful coping strategies (¶9). In relating this lack of success, informants emphasized the disconnect between the benefit they expected from the activity and the lack of pleasure they actually experienced.

¶9: You know what it’s like, even if there is a nice movie on TV, I’m just sitting there, I’m not enjoying it. I’m just thinking, thinking.

To a few informants, the lack of success of their coping strategies served as a marker that their mood was becoming a problem. The following informant had been diagnosed with depression, and reported marked seasonal variation in her mood (¶10).

¶10: Hopeless. You’re afraid to ask for help. You don’t want to go out; you want to stay home. You want to think a lot. You want to think, keep thinking. You don’t want to do anything. You just want to think. You try to do something to soothe yourself – okay you cook a meal – but after you eat, you still feel something. It’s still not enough, not that you’re still hungry, but feel still want some more, and you don’t know what to do. You cook the meal because you think that when you’re cooking, you spend the time, you can forget about those things. But after you cook, you eat, and then those things come back, and no more things for you do in the house. You still have to keep walking around. There’s nothing to watch on the TV. You go back to sleep, but you can’t, you stay awake. Don’t know what to do; you don’t want to read. You go online, there’s nothing interesting to you. You don’t want to see any homepages. You keep thinking a lot. You may try and call somebody, but that person don’t pick up the phone. You keep calling and calling. Then you feel like, okay, I’m not going to call that person again. But after a while you keep calling. I don’t know why. And outside it’s sunny. If it’s sunny, it makes you more depressed. If it’s sunny, it’s a little bit warmer, I might want to go across to the supermarket. If not, I probably just want to stay the whole day inside.

Feeling stuck and the inability to attempt minor readjustments

Some of our informants discussed sadness in terms related to their inability to even attempt to address their feelings. When this was the case, they tended to conceptualize their sadness as a lost battle, or as an entity entirely outside their control (¶11).

¶11: I get very depressed, so when I get stressed all I want to do is sleep, sleep, sleep, sleep, sleep because that’s how it was when [son’s name] wasn’t going to school like he would be in the house all day like, and sit in his room and watch cartoons, and I’d just sleep all day because I was so stressed I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t know how I was going to pay my rent. So I would just sleep and get very depressed, I don’t eat-all I want to do is sleep. I don’t want to talk to nobody. I don’t want to mess with the kids, you know. All I want to do is sleep, sleep, sleep. It’s like a heavy weight on your shoulder that you don’t know what to do, where you’re going to turn, ain’t no one there to help you at all. Why, why why did God let this happen to me, if there is a God, you know, so you just sleep it out, as the day pass.

Informants tended to view this inability to attempt to improve one’s situation – even if that situation was externally imposed – as a sign that their feelings may be “abnormal,” or may be a sign of depression. However, even when informants viewed such feelings as abnormal, they commonly invoked their social circumstances as the fundamental underlying reason for their feelings (¶12).

¶12: Sleep. Sleep because I can’t get a job. Sleep ‘cause my man is half of a man, don’t help nothing. Sleep ‘cuz the kids are so clingy. I don’t know why they’re like that because I’m not that type of person.

Discussion

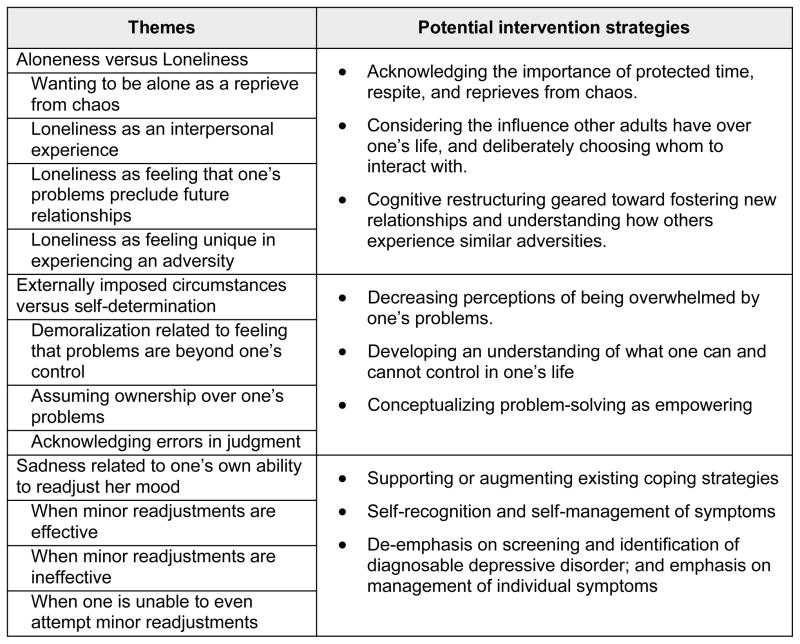

We discovered a series of themes regarding how informants appeared to interpret sadness, stress or demoralization in the context of their life experiences. Informants spoke of wanting reprieves from chaos – a desire often expressed in terms of wanting to be alone. By contrast, informants expressed loneliness not only in interpersonal terms, but also related to having problems that precluded future relationships, or feeling unique in experiencing an adversity. Informants contrasted the sense of empowerment associated with owning problems to the demoralization associated with feeling that one’s problems were externally imposed and therefore beyond their control. Informants also discussed sadness in relation to their own abilities to readjust their mood. On the mild end of the spectrum, informants related their ability to engage in activities to alleviate sadness. In the middle, informants related an ability to attempt such activities, but saw the attempts as unsuccessful. On the severe end, informants lost the ability to even attempt to make themselves feel better, and as a result expressed feeling stuck or hopeless.

These findings have potential implications for the design of culturally relevant, community-based interventions for maternal depression. First, attention to expressions of loneliness or aloneness may be important to understanding how young mothers interpret sadness. Specifically, programs that acknowledge the importance of “protected time” – in which individuals experience brief reprieves from chaos – appear likely to resonate with potential intervention recipients. Additionally, many of our informants’ expressions of loneliness appear modifiable, though not necessarily through conventional support group mechanisms. Rather, other forms of loneliness (like feeling one’s problems preclude interpersonal relationships) may be more amenable to other remedies, such as cognitive restructuring, motivational techniques, or more “internal” mechanisms of processing life events such as journaling or bibliotherapy.

Second, it may be important for interventions geared to populations like ours to foster the perception of greater control over one’s life. Distinguishing between what an individual can’t control and what she can – and focusing intervention efforts on the latter – may be important. In light of our finding that perceiving ownership of problems can be an empowering notion, it may be important to work to dispel the potential misconception that dealing with problems represents a focus on deficits; rather, that actively dealing with problems may be empowering.

Lastly, community-based maternal depression interventions may consider how to bolster women’s coping strategies so that they can better self-manage their feelings – irrespective of whether such feelings meet conventional criteria for depressive illness. Within community organizations, whose social service personnel are more accustomed to dealing with stress or social problems than with depression per se, such a strategy may represent an alternative to more conventional screening and referral intervention models.

Much of the literature on community-based mental health interventions has emphasized group models that promote social support. Such interventions have demonstrated mixed success (50, 51), and are logistically unfeasible in certain settings. Additionally, interventions based on screening and referral are limited by the lack of available mechanisms to assure that referrals are brought to fruition (15, 24). By contrast, many of our specific findings raise the possibility that interventions based on brief cognitive restructuring models may hold promise in settings outside the traditional medical system. Many such interventions have been developed and have demonstrated success in both community and medical settings (18, 52, 53). There is also evidence that they can be taught to providers relatively inexperienced in mental health (54).

Our study has a number of limitations. First, an in-depth discussion of our informants’ strengths and resiliencies was beyond the scope of our study. Although each informant expressed a unique set of strengths, this paper intentionally focused on perceptions of sadness, stress and demoralization; and that should not be interpreted as a comment that our informants’ weaknesses overwhelmed their strengths. Second, like many qualitative research endeavors, ours is not necessarily generalizable. All our informants were recruited from a single metropolitan area; all spoke English; and all had the social wherewithal to access the services from which they were recruited into the study. We cannot, therefore, comment about other, possibly more marginalized populations. We contend, however, that the venues from which our subjects were recruited reflect important national-level programs within which future depression programs are likely to be implemented, and that such a recruitment paradigm represents one of our study’s principal strengths. Lastly, our sampling frame was meant to maximize variability in responses. Its primary benefit was that it allowed us to hear from a wide range of informants; but this came at the expense of being able to make inferences on the basis of a proportionally representative sample.

Understanding women’s perceptions of their own feelings of sadness, stress or demoralization is important to maximizing the effectiveness of interventions designed to help them address these feelings. That said, our results do not indicate that one specific intervention model would be superior to any other. However, when viewed in the context of the Life Course Model – in which factors that impact wellbeing affect families across generations, and in which building capacity in the community represents a key strategy to reduce risk and foster resilience (55, 56) – our findings do shed light on potentially promising avenues for intervention planning. Given the morbidities associated with maternal depression – and the poor access to quality mental health services that low-income women have – the public health implications of such interventions, if successful, could be substantial.

Figure 2.

Themes and their relationship to potential intervention strategies

Acknowledgments

We thank Howard Bauchner, MD, Barry Zuckerman, MD, and Emily Feinberg, ScD, for their thoughtful review of the manuscript. We thank Lance Laird, Th.D. for sharing his insight on qualitative methodology. We thank the Joel and Barbara Alpert Children of the City Endowment for supporting this work. Dr. XXXXX is also supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (K23XXXXX) and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Sources of Support: Joel and Barbara Alpert Endowment, National Institute of Mental Health, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, Tandon A, Patel V, Ustun B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):851–858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349(9063):1436–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07495-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lanzi RG, Pascoe JM, Keltner B, Ramey SL. Correlates of maternal depressive symptoms in a national Head Start program sample. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(8):801–7. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.8.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Administration for Children and Families. Research to Practice: Depression in the Lives of Early Head Start Families: United States Department of Health and Human Services. Jan, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beeghly M, Olson KL, Weinberg MK, Pierre SC, Downey N, Tronick EZ. Prevalence, stability, and socio-demographic correlates of depressive symptoms in Black mothers during the first 18 months postpartum. Matern Child Health J. 2003;7(3):157–68. doi: 10.1023/a:1025132320321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kahn RS, Wise PH, Kennedy BP, Kawachi I. State income inequality, household income, and maternal mental and physical health: cross sectional national survey. BMJ. 2000;321(7272):1311–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7272.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall LA, Williams CA, Greenberg RS. Supports, stressors, and depressive symptoms in low-income mothers of young children. Am J Public Health. 1985;75(5):518–22. doi: 10.2105/ajph.75.5.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olson AL, DiBrigida LA. Depressive symptoms and work role satisfaction in mothers of toddlers. Pediatrics. 1994;94(3):363–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrington AR, Greene-Harrington CC. Healthy Start screens for depression among urban pregnant, postpartum and interconceptional women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(3):226–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zuckerman B, Moore KA, Glei D. Association between child behavior problems and frequent physician visits. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150(2):146–53. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170270028004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zuckerman B, Amaro H, Bauchner H, Cabral H. Depressive symptoms during pregnancy: relationship to poor health behaviors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160(5 Pt 1):1107–11. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weissman MM, Gammon GD, John K, Merikangas KR, Warner V, Prusoff BA, et al. Children of depressed parents. Increased psychopathology and early onset of major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44(10):847–53. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800220009002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nomura Y, Wickramaratne PJ, Warner V, Mufson L, Weissman MM. Family discord, parental depression, and psychopathology in offspring: ten-year follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(4):402–9. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200204000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray L, Cooper P. Effects of postnatal depression on infant development. Arch Dis Child. 1997;77(2):99–101. doi: 10.1136/adc.77.2.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Screening for depression: recommendations and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(10):760–4. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-10-200205210-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Tutty S, Operskalski B, Von Korff M. Telephone psychotherapy and telephone care management for primary care patients starting antidepressant treatment: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(8):935–42. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.March J, Silva S, Petrycki S, Curry J, Wells K, Fairbank J, et al. Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(7):807–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.7.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW, Jr, Hunkeler E, Harpole L, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2836–45. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kroenke K, West SL, Swindle R, Gilsenan A, Eckert GJ, Dolor R, et al. Similar effectiveness of paroxetine, fluoxetine, and sertraline in primary care: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2001;286(23):2947–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.23.2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reynolds CF, 3rd, Frank E, Perel JM, Imber SD, Cornes C, Miller MD, et al. Nortriptyline and interpersonal psychotherapy as maintenance therapies for recurrent major depression: a randomized controlled trial in patients older than 59 years. JAMA. 1999;281(1):39–45. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keller MB, Kocsis JH, Thase ME, Gelenberg AJ, Rush AJ, Koran L, et al. Maintenance phase efficacy of sertraline for chronic depression: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280(19):1665–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simon GE, VonKorff M, Heiligenstein JH, Revicki DA, Grothaus L, Katon W, et al. Initial antidepressant choice in primary care. Effectiveness and cost of fluoxetine vs tricyclic antidepressants. JAMA. 1996;275(24):1897–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miranda J, Chung JY, Green BL, Krupnick J, Siddique J, Revicki DA, et al. Treating depression in predominantly low-income young minority women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(1):57–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Needlman R, Kelly S, Higgins J, Sofranko K, Drotar D. Impact of Screening for Maternal Depression in a Pediatric Clinic: an Exploratory Study. Ambulatory Child Health. 1999;5:61–71. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weissman MM, Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne PJ, Talati A, Wisniewski SR, Fava M, et al. Remissions in maternal depression and child psychopathology: a STAR*D-child report. JAMA. 2006;295(12):1389–98. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.12.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chow JC, Jaffee K, Snowden L. Racial/ethnic disparities in the use of mental health services in poverty areas. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(5):792–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang ZJ, Wong FY, Ronzio CR, Yu SM. Depressive symptomatology and mental health help-seeking patterns of U.S - and foreign-born mothers. Matern Child Health J. 2007;11(3):257–67. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown DR, Ahmed F, Gary LE, Milburn NG. Major depression in a community sample of African Americans. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(3):373–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang PS, Berglund P, Kessler RC. Recent care of common mental disorders in the United States: prevalence and conformance with evidence-based recommendations. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(5):284–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.9908044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.United States Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of health, National Institute of Mental Health; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cooper LA, Gonzales JJ, Gallo JJ, Rost KM, Meredith LS, Rubenstein LV, et al. The acceptability of treatment for depression among African-American, Hispanic, and white primary care patients. Med Care. 2003;41(4):479–89. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000053228.58042.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Givens JL, Katz IR, Bellamy S, Holmes WC. Stigma and the acceptability of depression treatments among african americans and whites. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1292–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0276-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nadeem E, Lange JM, Edge D, Fongwa M, Belin T, Miranda J. Does stigma keep poor young immigrant and U.S.-born Black and Latina women from seeking mental health care? Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(12):1547–54. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.12.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown G. Social Origins of Depression. New York: The Free Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reading R, Reynolds S. Debt, social disadvantage and maternal depression. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53(4):441–53. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00347-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karasz A. Cultural differences in conceptual models of depression. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(7):1625–35. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anderson CM, Robins CS, Greeno CG, Cahalane H, Copeland VC, Andrews RM. Why lower income mothers do not engage with the formal mental health care system: perceived barriers to care. Qual Health Res. 2006;16(7):926–43. doi: 10.1177/1049732306289224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nadeem E, Lange JM, Miranda J. Mental health care preferences among low-income and minority women. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2008;11(2):93–102. doi: 10.1007/s00737-008-0002-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mrazek PJ, Haggerty RJ Committee on Prevention of Mental Disorders Institute of Medicine. Reducing Risks for Mental Disorders: Frontiers for Preventive Intervention Research. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74(4):511–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002;288(14):1775–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brach C, Fraser I. Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? A review and conceptual model. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57 (Suppl 1):181–217. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacobs F, Easterbrooks MA, Brady A, Mistry J. Healthy Families Massachusetts: Final Evaluation Report. Medford: Tufts University; 2005. May, [Google Scholar]

- 44.The National Healthy Start Initiative. Washington, D.C: [last accessed June 9, 2008.]. URL: http://www.healthystartassoc.org. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bernard HR. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. 3. Walnut Creek: Altamira Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. 3. Sage Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giacomini MK, Cook DJ for the Evidence-Based Medicine Working G. Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature: XXIII. Qualitative Research in Health Care B. What Are the Results and How Do They Help Me Care for My Patients? JAMA. 2000;284(4):478–482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.4.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Giacomini MK, Cook DJ for the Evidence-Based Medicine Working G. Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature: XXIII. Qualitative Research in Health Care A. Are the Results of the Study Valid? JAMA. 2000;284(3):357–362. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dennis CL. Psychosocial and psychological interventions for prevention of postnatal depression: systematic review. BMJ. 2005;331(7507):15. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7507.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dennis CL, Hodnett E. Psychosocial and psychological interventions for treating postpartum depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD006116. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006116.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ciechanowski P, Wagner E, Schmaling K, Schwartz S, Williams B, Diehr P, et al. Community-integrated home-based depression treatment in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(13):1569–77. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.13.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huibers MJ, Beurskens AJ, Bleijenberg G, van Schayck CP. The effectiveness of psychosocial interventions delivered by general practitioners. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2):CD003494. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hegel MT, Dietrich AJ, Seville JL, Jordan CB. Training residents in problem-solving treatment of depression: a pilot feasibility and impact study. Fam Med. 2004;36(3):204–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lu MC, Halfon N. Racial and ethnic disparities in birth outcomes: a life-course perspective. Matern Child Health J. 2003;7(1):13–30. doi: 10.1023/a:1022537516969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kotelchuck M. Building on a life-course perspective in maternal and child health. Matern Child Health J. 2003;7(1):5–11. doi: 10.1023/a:1022585400130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]