Abstract

Objective

To estimate the proportion of children who receive an Individualized Education Program (IEP) following grade retention in elementary school.

Design/setting

Descriptive analysis of a nationally representative, longitudinal cohort.

Participants

Children retained in K/1 and 3rd grade for presumed academic reasons, followed through fifth grade.

Outcome measure

Presence or absence of an IEP.

Results

300 children retained for presumed academic reasons in K/1, and 80 in 3rd grade were included in the study. Of the K/1 retainees, 68% never received an IEP over the subsequent four to five years; of the 3rd grade retainees, 73% never received an IEP. K/1 retainees in the highest SES quintile and suburban K/1 retainees were less likely to receive an IEP than retained children in all other SES quintiles (aOR 0.17; 95% CI 0.05-0.62) and in rural communities (aOR 0.16; 95% CI 0.06-0.44), respectively. Among K/1 retainees with persistent low academic achievement in reading and math (as assessed by standardized testing), 37% and 28%, respectively, never received an IEP.

Conclusions

The majority of children retained in K/1 or 3rd grade for academic reasons, including a many of those who demonstrate sustained academic difficulties, never receive an IEP during elementary school. Further studies are important to elucidate whether retained elementary school children are being denied their rights to special education services. In the meantime, early grade retention may provide an opportunity for pediatricians to help families advocate for appropriate special education evaluations for children experiencing school difficulties.

Keywords: grade retention, individualized education program, special education, school readiness

Introduction

In the United States, 5-10% of students are retained annually,1 and 10% of students aged 16-19 years have repeated a grade.2 In 2003, the National Center for Education Statistics reported that 9% of white students, 13% of Hispanic students, and 18% of black students were retained in 1999.3 A proportion of these students may require special education services at the time they are retained, in subsequent years, or both. Timely recognition of – and support for – children requiring special education services could prevent the need for long-term and expensive educational services by effectively addressing children’s needs when they arise.4 Appropriate intervention could also minimize the likelihood that a child will repeat an additional grade, which increases the likelihood of subsequent school dropout.5

One approach to supporting a child with low academic achievement is the provision of special education services, as indicated by an Individualized Education Program (IEP). An IEP is a legally binding document describing a child’s special education services, and is developed after a child has undergone a special evaluation and been determined eligible for services. The services indicated on an IEP may include various therapies (speech and language, occupational, physical) or placement in a special education classroom. Although eligibility for an IEP varies from state to state, evaluation for an IEP is the right of every American child under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

Pediatricians are under increasing pressure to support families whose children experience academic, or other, difficulties in school. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has written a policy statement and guidelines for pediatrician involvement in the IEP process, and members of the pediatric community have called on pediatricians to address school failure with families.6-9 The AAP suggests multiple roles for the pediatrician, including screening, diagnosis, referral to appropriate services and advocacy,10 the last of which is emphasized in the new Bright Futures Guidelines for Child Health Supervision.11 Grade retention, specifically, has been posited as a “red flag” that might prompt providers to advocate for more special education assessments and services for children demonstrating academic difficulties.5, 9, 12

We sought to examine, among children retained in kindergarten, first grade and third grade, the proportion that received special education services, as indicated by an IEP. We were particularly interested in those retained children who demonstrated persistent academic difficulty, as these children would qualify for special education services in the vast majority of school districts in the US. We further sought to perform an exploratory analysis, describing subject characteristics associated with IEP receipt despite early grade retention and persistent academic underachievement.

Methods

Data Source and Study Sample

We extracted data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study – Kindergarten Cohort (ECLS-K). The ECLS-K is a nationally representative sample of children who attended kindergarten in 1998-1999, and were monitored through the fifth grade with parent interviews, teacher surveys, and direct assessments of academic performance. Details of the ECLS sampling strategy, response rate, and design are available at http://nces.ed.gov/ecls/kinderdataprocedure.asp.

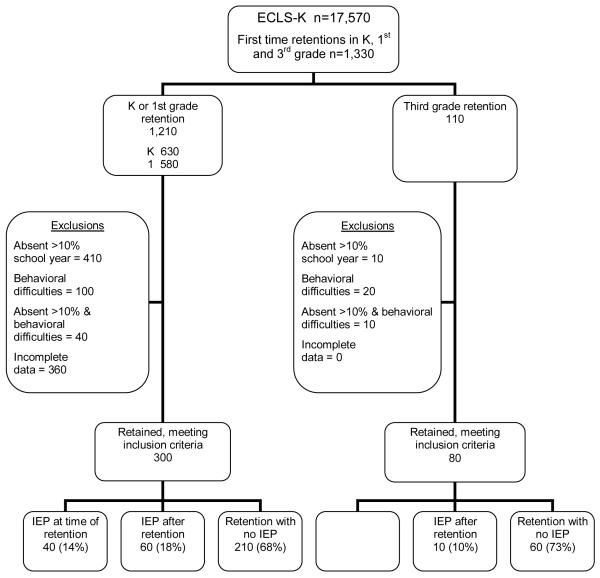

Although the specific criteria for grade retention vary across school districts, academic underachievement and behavioral/social difficulties are the most commonly cited reasons for retention.13, 14 We aimed to include children retained only for academic reasons in our study, and therefore excluded children with substantial behavior problems, as reported by their teachers to have significant externalizing problem behavior (scores >2SD above the mean) or self-control difficulties (scores >2SD below the mean) on the Social Rating Scale, an adaptation of the valid and reliable Social Skills Rating System (Figure).15 Additionally, because the phenomenon of school absenteeism is complex and multifactorial (and likely linked to problem behavior, underachievement and retention),16 we excluded children who were absent from school more than 10% of the year in which the retention occurred and assumed the remaining children were retained for academic underachievement. We further restricted our analysis to first-time retentions because we felt that repeated retentions – and therefore possibly repeated IEPs – may not represent statistically independent events, and may even be causally related to one another.

Figure. Sample Description.

All unweighted absolute numbers are rounded to the nearest 10 subjects; all percentages reflect unweighted estimates on non-rounded numbers.

Measures

Our dependent measure was the presence of an IEP, as reported for each subject through a school administrator’s response to a standardized school record abstraction form. Using these forms, ECLS prospectively recorded dates, goals and disabilities listed on each IEP. It also tracked school transfers and proactively collected IEP information from schools that subjects no longer attended. Although IEP data were available for each school year from kindergarten through fifth grade, data on the specific year of retention and the specific year of excess absenteeism were available only for the kindergarten, first grade and third grade years. We therefore present data regarding first time retentions only for kindergarten, first and third grade.

We extracted data concerning IEP goals and disabilities. Whereas an IEP goal reflects an educational objective often related to the reason an evaluation was sought, an IEP disability reflects the conclusions of that evaluation. A single IEP may list multiple goals and disabilities. For ease of reporting, we categorized the IEP goals of reading, mathematics, language arts and science as ‘academic goals;’ we categorized auditory processing and listening comprehension as ‘listening/hearing goals;’ we categorized oral expression, voice/speech and language pragmatics each as ‘speech goals;’ we grouped social skills and adaptive behaviors together as ‘social/behavioral goals;’ and we combined fine motor, gross motor and orientation/mobility into a ‘motor skills’ category.

The following additional measures were extracted from the ECLS-K dataset based on their theoretical relevance to IEP receipt. Child race was identified by parents and classified as white, black, Hispanic, Asian, or other. Socioeconomic status was assessed by the National Center for Education Statistics based on income, education, and social prestige, and divided into five quintiles. We extracted the primary language of the child (categorized as English or Non-English), maternal education at the time the child entered the study (categorized as Less than High School or Completed High School), type of community child lived in (urban, suburban, or rural), and whether the child was part of a single or dual parent family.

To obtain an objective measure of academic achievement, we extracted standardized T scores for directly administered assessments of reading and math proficiency during each year of data collection. Because the ECLS cohort is nationally representative, the T scores indicate the extent to which an individual ranks higher or lower than the national average. We defined low academic achievement as scoring greater than two standard deviations below the mean on these tests.

Data Analysis

We performed all analyses separately for children retained in kindergarten or first grade (K/1 retainees) and for children retained in third grade (3rd grade retainees). We stratified the analyses in this manner for 3 reasons: first, kindergarten is not a mandatory requirement throughout the US, and as a result there is significant overlap between kindergarten and first grade curricula; second, the anecdotally common practice of parents electing to have a child repeat her first year of school would likely affect K/1 retentions (and therefore underestimate the proportion to receive IEPs), but would unlikely affect third grade retentions; lastly, third grade is typically the year children solidify their literacy skills, and therefore the year that learning disabilities often manifest.

Within the K/1 and 3rd grade strata, we first sought to validate our assumption that by excluding frequently absent children and children with behavioral problems, we were enriching our sample for students with academic difficulties, as opposed to those retained for other reasons such as parent choice. To do so, we modeled the odds of having low academic achievement among retained vs. non-retained children by weighted multivariable logistic regression. In this analysis, children who were not retained were subject to the same exclusion criteria (based on absenteeism and behavioral problems) as the retained sample.

Among the K/1 and third grade retainees, our primary outcome of interest was the proportion of children to receive an IEP by the fifth grade – the last elementary school year available in the ECLS data. Multivariable logistic regression was used to test associations between theoretically relevant demographic characteristics and IEP receipt. The same series of analyses was repeated among retained children who also demonstrated low academic achievement in the fifth grade. Individual level weights were used to yield valid national estimates; longitudinal weights were applied to account for ECLS’s intentional diminution of sample size over the course of the longitudinal study.17 The Taylor series estimation, an accepted technique to adjust standard errors for weighted data, was used to accommodate the ECLS-K’s complex sampling design.18 All analyses were performed with Intercooled Stata 9.2 (College Station, Tx).

The Boston University Medical Center granted exemption from Institutional Board Review. Pursuant to the terms of the ECLS restricted data use license, this manuscript was reviewed by the National Center for Educational Statistics prior to publication. All sample sizes reflecting unweighted data are rounded to the nearest 10 subjects, but reported percentage estimates reflect the actual data.

Results

Sample description

Of the 17,570 children included in the ECLS-K dataset, 1,330 (8%) experienced their first retention in grades K (630; 4%), 1 (580; 3%), or 3 (110; 1%). In the K/1 retained group, 550 children were excluded from the analysis for excess absenteeism and/or behavioral difficulties, and another 360 for having incomplete data.* In the 3rd grade retained group, 40 children were excluded for excess absenteeism and/or behavioral difficulties. This left 300 children retained in K/1 and 80 children retained in 3rd grade for presumed academic difficulties included in the analyses (Figure).

The K/1 retainees had a far greater likelihood of low academic achievement, both at the time of retention (aOR for low reading achievement 25.5; 95% CI 17.8, 36.7) and in the fifth grade (aOR for low reading achievement 17.4; 95% CI 10.7, 28.3) than children who were not retained in these years – consistent with our assumption that academic difficulty was the primary reason for retention in our cohort. A similar trend held for those retained in 3rd grade, but a low sample size precluded stable regression models among this group.

IEP Receipt

Of the 300 children retained in kindergarten or first grade, 40 (14%) had an IEP on record during the year they were retained, 60 (18%) received an IEP in the subsequent 1-5 years, and 210 (68%) never received an IEP over the study period (Figure). Of the 80 children retained in third grade, 20 (18%) had an IEP on record during or before the year they were retained, 10 (10%) received an IEP in the subsequent 1-2 years, and 60 (73%) never received an IEP over the study period.

Academic IEP Goals and Disabilities

Of the 130 total IEPs received by our cohort of retained children (K/1 plus 3rd grade), 80 (62%) had data concerning IEP goals and 60 (46%) had data concerning the precise disabilities listed on the IEP (Table 1). Whereas 44% of K/1 IEPs specified an academic goal, 83% of 3rd grade IEPs did so (p=<0.001). Among the K/1 IEPs, the most commonly listed goal was related to speech, and among the 3rd grade IEPs, the most commonly listed goal was related to academics. Similarly, whereas only 3% of K/1 IEPs listed learning disability as an official IEP disability, 27% of 3rd grade IEPs did so.

Table 1.

IEP Goals and Disabilities by Year of IEP

| K/1st Grade | 3rd Grade | |

|---|---|---|

| IEP Goals | ||

| Unweighted total number of IEPs with reported goals |

40 | 40 |

| Weighted total number of IEPs with reported goals |

12,000 | 12,000 |

| Reported IEP goals (%) | ||

| Academics | 44 | 83 |

| Listening | 59 | 39 |

| Speech | 87 | 61 |

| Social Adaptation | 23 | 14 |

| Motor Skills | 33 | 19 |

| Other | 8 | 6 |

| IEP Disabilities | ||

| Unweighted total number of IEPs with reported disabilities |

40 | 20 |

| Weighted total number of IEPs with reported disabilities |

9,480 | 5,970 |

| Reported IEP disabilities (%) | ||

| Learning disability | 3 | 27 |

| Emotional disturbance | 0 | 0 |

| Speech/language impairment | 83 | 55 |

| Mental retardation | 9 | 18 |

| Visual impairment/blindness | 6 | 0 |

| Hearing impairment/deafness | 0 | 0 |

| Health impairment | 3 | 9 |

| Physical impairment | 9 | 5 |

| Multiple impairments | 3 | 5 |

| Deaf and blind | 0 | 0 |

| Developmental delay | 20 | 9 |

| Autism | 0 | 0 |

| Traumatic brain injury | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 20 | 0 |

All unweighted absolute numbers are rounded to the nearest 10 subjects; all percentages reflect unweighted estimates on non-rounded numbers.

Grade retention and correlates of IEP receipt (Table 2)

Table 2.

Sample Characteristics among Children Retained for Presumed Academic Reasons

| Characteristics | K/1 retainees | 3rd grade retainees | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Did Not Receive IEP (%) |

Chi- square p value |

n | Did Not Receive IEP (%) |

Chi- square p value |

|

| Population estimate, weighted n |

116,000 | 82,000 | 51,000 | 40,000 | ||

| Sample Size | 300 | 210 (68) | 80 | 60 (73) | ||

| Child gender | ||||||

| Male | 200 | 130 (63) | 0.005 | 40 | 30 (68) | 0.316 |

| Female | 100 | 80 (79) | 40 | 30 (77) | ||

| Race | ||||||

| White | 160 | 110 (68) | 0.809 | 30 | 20 (68) | 0.203 |

| Black | 50 | 30 (63) | 20 | 20 (88) | ||

| Hispanic | 50 | 40 (72) | 20 | 20 (71) | ||

| Asian | 20 | 10 (76) | 0 | 0 (50) | ||

| Other | 20 | 20 (65) | 0 | 0 (33) | ||

|

Socioeconomic

Status |

||||||

| 1st quintile (lowest) |

80 | 50 (62) | 0.008 | 40 | 30 (74) | 0.114 |

| 2nd quintile | 70 | 50 (68) | 10 | 10 (79) | ||

| 3rd quintile | 50 | 30 (72) | 10 | 0 (38) | ||

| 4th quintile | 50 | 30 (60) | 10 | 10 (82) | ||

| 5th quintile (highest) |

50 | 40 (89) | 0 | 0 (33) | ||

|

Primary Language

of Child |

||||||

| English | 260 | 180 (70) | 0.117 | 60 | 20 (70) | 0.950 |

| Non-English | 40 | 30 (58) | 30 | 40 (73) | ||

| Maternal Education | ||||||

| < high school | 60 | 40 (64) | 0.455 | 20 | 20 (70) | 0.929 |

| ≥ high school | 240 | 170 (69) | 50 | 40 (71) | ||

| Community Type | ||||||

| Urban | 110 | 80 (70) | 0.055 | 30 | 30 (82) | 0.029 |

| Rural | 80 | 50 (58) | 20 | 10 (50) | ||

| Suburban | 120 | 90 (74) | 20 | 20 (79) | ||

|

Number of parents

in home |

||||||

| Single parent | 100 | 70 (68) | 0.956 | 20 | 20 (74) | 0.609 |

| Dual parent | 200 | 138 (68) | 50 | 30 (68) | ||

All unweighted absolute numbers are rounded to the nearest 10 subjects; all percentages reflect unweighted estimates on non-rounded numbers.

Among K/1 retainees, in multivariable analysis, the likelihood of IEP receipt during the study period was not related to race, primary language, maternal education, or living in a single parent household (Table 3). Retained children in the highest SES quintile were significantly less likely (aOR 0.17; 95% CI 0.05-0.62) to receive an IEP when compared to children in other SES quintiles. Retained children living in suburban communities were significantly less likely (aOR 0.16; 95% CI 0.06-0.44) to receive an IEP when compared to children living in rural communities. Due to sample size limitations multivariable analyses were not conducted among 3rd grade retainees.

Table 3.

IEP Receipt In Relation To Subject Characteristics Of Retained Children – Weighted Multivariable Analysis

| Subject Characteristics | aOR for IEP receipt (95% CI) among K/1st Grade retainees |

|---|---|

| All Minority vs. White Race | 0.97 (0.37,2.51) |

| Highest SES Quintile vs. Lowest 4 | 0.17 (0.05,0.62) |

| Primary Language English | 0.50 (0.05,4.61) |

| Maternal Education > High School | 0.54 (0.15,1.90) |

| Suburban vs. Urban Community | 0.65 (0.19,2.27) |

| Suburban vs. Rural Community | 0.16 (0.06,0.44) |

| Two parent vs. single parent home | 1.62 (0.51,5.14) |

| Female vs. Male Gender | 1.05 (0.47,2.38) |

Among the K/1 retainees who had low fifth grade math achievement, 37% (95% CI 20-54%) never received an IEP. Among the K/1 retainees who had low 5th grade reading achievement, 28% (95% CI 13-43%) never received an IEP (Table 4). Among the persistently low achieving 3rd grade retainees, low sample sizes produced IEP frequency estimates with confidence intervals too wide to be interpretable (Table 4). Among both the K/1 and 3rd grade retainees, low sample sizes of children with persistently low fifth grade achievement precluded a reliable multivariable analysis of demographic correlates of IEP receipt among this subpopulation.

Table 4.

Longitudinal Academic Achievement and IEP Receipt

| Type of Assessment | Those with poor academic achievement never to receive an IEP (%; 95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

| K/1st Grade | 3rd Grade | |

| During Retained Year | ||

| Math | 10/40 (39%; 22-56%) | 0/10 (43%; 0-92%) |

| Reading | 20/40 (36%; 22-51%) | 0/0 (66%; 0-100%) |

| Math and Reading | 0/20 (27%; 7-47%) | 0/10 (43%; 0-92%) |

| During 5th Grade Year | ||

| Math | 10/40 (37%; 20-54%) | 0/0 (75%; 0-100%) |

| Reading | 10/40 (28%; 13-43%) | 0/10 (33%; 0-88%) |

| Math and Reading | 0/20 (22%; 1-43%) | 0/0 (75%; 0-100%) |

All unweighted absolute numbers are rounded to the nearest 10 subjects; all percentages reflect unweighted estimates on non-rounded numbers.

Discussion

Within this nationally representative sample of children retained in kindergarten or first grade – and followed through the fifth grade – 68% did not receive additional academic support in the form of an IEP. Among those retained in the 3rd grade, 73% did not receive an IEP. As many as 37% of K/1 retainees – who continued to demonstrate substantial academic difficulties and almost surely would have qualified for an IEP – did not receive one. Although the proportion of IEPs to specifically list academic goals and to specifically categorize the child as having a learning disability increased between the K/1 and third grade retention years, the proportion of retainees never to receive an IEP remained equally high across these time points.

Although debates about the value of grade retention abound, the practice, in and of itself, has never been demonstrated to be an effective intervention relative to subsequent academic achievement or socioemotional adjustment.19 In fact, a previous study using the same ECLS cohort found no evidence that grade retention in kindergarten improved subsequent achievement in mathematics or reading.20 Some experts in the field, therefore, believe that retention practices need to be accompanied by focused individualized assessments of children’s special education needs.21 Although our results do not definitely demonstrate that retained children have been denied their rights to such assessments, they raise the question of whether or not the potential special education needs of retained children, particularly those who demonstrate persistent academic difficulties, are being addressed consistently.

Our findings build on a body of previous work, which suggests that many children facing learning difficulties or school failure may not be receiving timely or appropriate services. Multiple parent support groups exist across the US, in large measure, to coordinate advocacy efforts and pressure school districts to bring such services to bear.22, 23 Furthermore, a year 2000 report from the Federal Council on Disability found that all 50 states were out of compliance with federal standards regarding special education legislation, and that parents were unjustly bearing the burden of ensuring appropriate and timely services.24 Given that educators may lack the time and resources to implement intervention strategies apart from grade retention,25 and that pediatricians are increasingly being called upon to advocate for their patients’ educational needs, noting grade retention among school age pediatric patients may prompt providers to proactively advise families regarding their rights to a special education evaluation and to advocate for families within their local school systems.

Our study has a number of limitations. First, we were unable to directly assess the reason for grade retention. As mentioned, we excluded children with marked absenteeism or behavior problems; and although the remaining retained children appeared to be poor academic performers, we are unable to exclude other, less common, reasons for retention (for example, limited English proficiency or parent choice). However, in addition to corroborating our approach by comparing the directly assessed math and reading proficiency of the retained and non-retained ECLS subjects, our approach is supported by the fact that a large proportion of IEP recipients, both at K/1 and third grade, had IEP goals dealing specifically with educational achievement.

Second, because we were unable to determine whether retained children had been evaluated – but found ineligible – for special education services, we cannot definitively assert that these children have been denied their rights to special education services. It remains possible, in other words, that the approximately 70% of retainees in our study who did not receive IEPs were either appropriately evaluated and justly denied services or sought services outside the IEP infrastructure. However, given that we defined low academic achievement as performance >2SD below the mean in reading or math (placing these children 2-3 years behind their peers), we felt it likely that this subgroup of K/1 retainees would have been found eligible for special education services if they had been assessed. Still, among this group, nearly a third did not receive IEPs.

Additional limitations of this study include our inability to track subjects beyond the fifth grade, which leaves unknown the question of IEP receipt in subsequent years. However, for children with academic difficulty in K/1 or 3rd grade, an IEP many years later would not be considered timely. Also, although our decision to exclude children with excessive absenteeism and substantial behavior problems makes for a purer sample of students retained for academic reasons alone, we realize that absenteeism, problem behavior and poor academic performance are often comorbid. As a result, readers should be cautious about generalizing our results to children with excessive absenteeism or substantial behavior problems. We admit that our finding that high SES retainees are less likely to obtain IEPs than low SES retainees is counterintuitive, and may therefore bespeak a confounded result. Lastly, it is possible that some children with academic difficulty receive special education services outside the purview of the IEP system.

With the above limitations considered, our study demonstrates that a large proportion of children retained in elementary school do not receive IEPs. Although the study lacks some key information to demonstrate a widespread denial of children’s rights to special education services, it does demonstrate the need for further investigation into how elementary school children failing school are evaluated and served – specifically, a systematic inquiry into whether or not children’s rights have been denied. In the meantime, we believe these data provide pediatricians with useful information to inform their practice: specifically, that providers cannot assume local school districts are doing everything in their power to help children who are failing school. Rather, knowing that a child has been retained in grade may prompt providers to help families obtain IEP evaluations, and – if possible – help them interpret the results.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful for the support of Howard Bauchner, MD. In addition we thank Howard Cabral, PhD for his insights regarding statistical methods and analyses. We also thank Kari Hironaka, MD, MPH for her thoughtful review of the manuscript. All authors declare no potential conflicts of interest in undertaking this study. Michael Silverstein, MD, MPH had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

This study was supported by Maternal Child Health Bureau training grant T77MC00015. All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Per the ECLS restricted data use agreement, all numbers are rounded to the nearest 10 subjects and may not tabulate perfectly. “Incomplete data” in this case a function of an intentional diminution of sample size over the course of the longitudinal ECLS study.

References

- 1.Byrd RS, Weitzman ML. Predictors of early grade retention among children in the United States. Pediatrics. 1994 Mar;93(3):481–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Condition of Education. U.S. Depatment of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; Washington, DC: 2006. NCES 2006-071. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Status and Trends in the Education of Hispanics. U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; Washington, DC: 2003. NCES 2003-008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gryphon M, Salisbury D. Escaping IDEA: Freeing Parents, Teachers, and Students through Deregulation and Choice. Policy Analysis. 2002;(No-444) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byrd RS. School failure: assessment, intervention, and prevention in primary pediatric care. Pediatr Rev. 2005 Jul;26(7):233–243. doi: 10.1542/pir.26-7-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrd RS, Weitzman M, Auinger P. Increased behavior problems associated with delayed school entry and delayed school progress. Pediatrics. 1997 Oct;100(4):654–661. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.4.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halfon N, DuPlessis H, Inkelas M. Transforming the U.S. child health system. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007 Mar-Apr;26(2):315–330. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.2.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blanchard LT, Gurka MJ, Blackman JA. Emotional, developmental, and behavioral health of American children and their families: a report from the 2003 National Survey of Children’s Health. Pediatrics. 2006 Jun;117(6):e1202–1212. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hehir TMK, Palfrey JS, Smith PJ. Educating children with disabilities: how pediatricians can help. Contemporary Pediatrics. 2002 Sept;9:102. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10.The pediatrician’s role in development and implementation of an Individual Education Plan (IEP) and/or an Individual Family Service Plan (IFSP). American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Children with Disabilities. Pediatrics. 1999 Jul;104(1 Pt 1):124–127. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.1.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagan JF, Shaw J, Duncan P, editors. Bright Futures Guidelines for Health Supervisions of Infants, Children, and Adolescents. 3rd ed American Academy of Pediatrics; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lambros KM, Leslie LK. Management of the child with a learning disorder. Pediatr Ann. 2005 Apr;34(4):275–287. doi: 10.3928/0090-4481-20050401-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steiner K. [Accessed October 30, 2008];Grade Retention and Promotion. 2008 http://ericae.net/edo/ED267899.htm.

- 14.Heubert JP, Hauser RM, editors. High Stakes: Testing for Tracking, Promotion, and Graduation. National Academy Press; Washington, D.C.: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gresham F, Elliot S, editors. Social Skills Rating System. American Guidance Services, Inc.; Circle Pines, MN: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kearny C. An Interdisciplinary Model of School Absenteeism in Youth to Inform Professional Practice and Public Policy. Educational Psychology Reivew. 2008;20(3):257–282. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tourangeau K, Nord C, Lê T, Pollack JM, Atkins-Burnett S. Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 1998–99 (ECLS-K), Combined User’s Manual for the ECLS-K Fifth-Grade Data Files and Electronic Codebooks (NCES 2006–032): U.S. Department of Education. National Center for Education Statistics; Washington, DC: [Accessed October 30, 2008]. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burt VL, Cohen SB. A comparison of methods to approximate standard errors for complex survey data. Rev Public Data Use. 1984 Oct;12(3):159–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jimerson SR. Meta-Analysis of Grade Retention Research: Implications for Practice in the 21st Century. School Psychology Review. 2001;30(3):420–437. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong G, Raudenbush SW. Effects of Kindergarten Retention Policy on Children’s Cognitive Growth in Reading and Mathematics. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. 2005 January 1;27(3):205–224. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kinlaw CR. Sorting out Student Retention: 2.4 Million Children Left behind? Policy Matters. Center for Child and Family Policy, Duke University (NJ1); 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 22. [Accessed October 30, 2008];Special Education: Getting the Best School Experience. http://specialchildren.about.com/od/specialeducation/Special_Education_Getting_the_Best_School_Experience.htm.

- 23.PAGER. Parent Advocacy Group for Educational Rights [Accessed October 30, 2008]; http://www.pagergroup.org/index.html.

- 24.West J. Back to School on Civil Rights: Advancing the Federal Commitment To Leave No Child Behind: National Council on Disability. Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xia C, Glennie E. Grade Retention: A Three Part Series. Policy Briefs. Grade Retention: A Flawed Education Strategy [and] Cost-Benefit Analysis of Grade Retention [and] Grade Retention: The Gap between Research and Practice. Center for Child and Family Policy, Duke University (NJ1); 2005. [Google Scholar]