Abstract

Background

Advanced (“open”) access scheduling, which promotes patient-driven scheduling in lieu of pre-arranged appointments, has been proposed as a more patient-centered appointment method and has been widely adopted within the United Kingdom and Veterans Health Administration and among U.S. private practices.

Objective

To describe patient, physician and practice outcomes resulting from implementation of advanced access scheduling in the primary care setting.

Data Sources

Comprehensive search of electronic databases (MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science) until August 2010, supplemented by reviewing reference lists and gray literature.

Study Selection

Studies were assessed blinded and in duplicate. Controlled and uncontrolled English-language studies of advanced access implementation in primary care were eligible if they specified methods and reported outcomes data.

Data Extraction

2 reviewers collaboratively assessed risk for bias by using the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group Risk of Bias criteria. Data were independently extracted in duplicate.

Data Synthesis

28 papers describing 24 studies met eligibility criteria. All studies had at least one source of potential bias. All 8 studies evaluating time to third next available appointment showed reductions (range of decrease 1.1–32 days) but only 25% (2/8) achieved a third-next-available appointment <48 hours. No-show rates improved only in practices with baseline no-show rates >15%. Effects on patient satisfaction were variable. Limited data addressed clinical outcomes and loss to follow-up.

Conclusion

Studies of advanced access support benefits to wait time and no-show rate. However, effects on patient satisfaction were mixed and data about clinical outcomes and loss to follow-up were lacking.

Introduction

Advanced access is an appointment scheduling system that allows patients “to seek and receive care from the provider of choice at the time the patient chooses.”1 Traditional scheduling systems arrange appointments for future dates, resulting in each physician’s patient care time being mostly scheduled well in advance. Consequently, wait time for appointments can be long, and patients may miss long-scheduled appointments.2 In fact, the average wait time in 2009 for a new non-urgent visit with a U.S. family practice physician was 20 days.3 By contrast, in advanced access, patients are offered an appointment on the day that they call or at the time of their choosing, preferably within 24 hours. This results in few pre-scheduled appointments and a relatively open schedule. Triage is minimized as everyone is offered an appointment whether for urgent or routine care.

There has been increased interest in advanced access as waiting times for routine healthcare have lengthened in recent years,3,4 leading to negative health outcomes5 and contributing to emergency department crowding.6,7 The Institute for Healthcare Improvement reports working with about 3,000 practices to implement advanced access.8 Both the Veteran’s Affairs system and the United Kingdom’s National Health Service have implemented advanced access in their extensive networks of ambulatory practices.9,10 In 2003, 47% of National Association of Public Hospitals members reported at least piloting advanced access in their primary care clinics.11

Proponents of advanced access suggest that it reduces patient waiting times, improves continuity of care, and reduces no-shows.12–14 On the other hand, skeptics of the system point out that advanced access is difficult to implement, may instead reduce continuity of care, and may leave patients with chronic conditions lost to follow-up. 11,12,15,16 Published reports of advanced access implementations are inconsistent. Therefore, given the widespread usage and promotion of advanced access, coupled with uncertainty as to its impact on physicians and patients, our objective was to summarize and evaluate the field of research examining the outcomes of advanced access scheduling systems in the primary care setting through a systematic review of the literature.

Methods

Data Sources and Searches

To identify relevant articles, we searched the following databases: OVID (1950-August 2010), Scopus (1960-August 2010), and Web of Science (1900-August 2010). Search strategies differed, depending upon the database. In OVID, we used the keywords “open access or advanc$ access or same-day” combined with the keywords “schedul$ or appoint$.” We also used the keywords “open access or advanc$ access or same-day” combined with the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms “Primary Health Care” and “Appointments and Schedules” using the Boolean term “and.” In Scopus we altered the search terms to comply with search mechanisms and used (schedul* OR appoint*) AND (“open access” OR “advanced access” OR “advance access” OR “same day”). We used the search strategy TS=(schedul* OR appoint*) AND TS=(advanced access OR advance access OR open access) to identify articles in Web of Science. We also hand searched bibliographies of pertinent articles.

Study selection

Full-length articles, research letters, and brief reports in English were eligible for inclusion. Of these, we included articles that: (1) investigated an advanced access intervention in a primary care setting (including cohort, case-control, cross-sectional, and randomized controlled trials), (2) reported quantitative outcomes for patients and/or providers, and (3) compared intervention and non-intervention data. We excluded conference abstracts because of the preliminary nature of their data. Commentaries, editorials, and narratives not written in scientific format – i.e. without a full description of methodology, study population, baseline data or results, and with no statistical testing – were also excluded.

One investigator selected articles for review based on title and/or abstract. Two investigators then independently assessed abstracts for inclusion. Reviewers were blinded to author, journal, and date of publication. If an investigator could not make an inclusion/exclusion decision based on the abstract, the full article was retrieved. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two investigators independently extracted data for each study using a standardized form. Main outcomes included success of advanced access implementation (time to the third available appointment), physician/practice outcomes (no-show rate, fiscal outcomes, and provider satisfaction), and patient outcomes (patient satisfaction, continuity of care, loss to follow-up, emergency room/urgent care use, and chronic disease quality measures). Time-to-third-available appointment is a widely-utilized metric for appointment availability.17 It is preferred over the time to the next available appointment because it does not give the false impression of schedule availability if there is a last-minute cancellation. When time-to-third-available appointment data were reported for both new and return visits (or, long and short visits), we recorded the result for the return, or short, visit. We defined continuity of care as any measure of the frequency with which patients see their own primary care physician (PCP).18–21

Studies used a variety of questions and reporting methods to describe patient satisfaction. For purposes of analysis, we divided satisfaction questions into two broad categories: overall satisfaction and appointment system satisfaction. Overall satisfaction included questions such as “How satisfied are you with today’s visit?” while appointment system satisfaction included questions such as “Were you able to get an appointment as soon as you wanted?” or “How satisfied were you with the appointment system?”

In addition, we abstracted study characteristics and demographics including trial design, funding, country of study, practice setting, number of practices and physicians, number of patients, and length of follow-up.

There are no validated tools for assessing the quality of quality improvement studies, which differ from standard therapeutic interventions in several important ways, including unit of analysis (typically provider rather than patient) and role of local context. Consequently, we adapted the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group Risk of Bias criteria to qualitatively report the risk of bias of the study results.22 These criteria are similar to those found in the SQUIRE guidelines for quality improvement reporting23 and the AHRQ Evidence Report on Systems to Rate the Strength of Scientific Evidence.24 We did not consider funding as no studies were commercially funded.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

The limited reporting of the trials and wide variety of outcomes evaluated precluded a meta analysis of results; consequently, we describe results qualitatively. All study designs are reported together. We hypothesized that if advanced access were an effective strategy, then studies with more successful implementations (defined as those with shorter final time-to-third-available appointment) would be more likely to report successful physician or patient outcomes. The only outcome for which there were enough studies to examine this hypothesis was no-show rate. Consequently, to determine if the success of advance access implementation affected outcomes, we conducted a linear regression of time-to-third-available appointment on no-show rate.

We used an Access 2002 database (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) to conduct blinded, independent reviews of the literature, and SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) to conduct the linear regression. As this study did not consist of direct human subjects research, institutional review board approval was not required.

Results

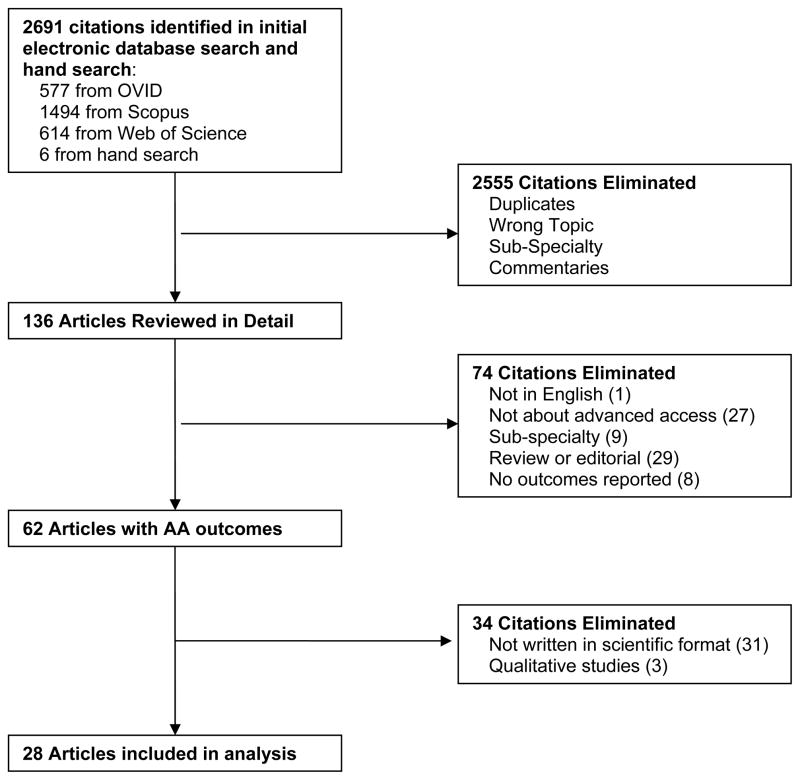

The initial electronic database search identified 2,691 citations, of which 2,556 were excluded based on title review by one investigator (K.R.) because they were not about advanced access, were set in specialty settings, were conference abstracts or were duplicates found in multiple databases (Figure 1). Two independent, blinded investigators reviewed the remaining 136 article titles and abstracts for selection, excluding 74 because they were identified as not in English (N=1), not about advanced access (N=27), sub-specialty studies (N=9), reviews, editorials or non-research letters (N=29), or did not include patient or provider outcomes related to advanced access (N=8). Of the remaining 62 articles of advanced access implementations in the primary care setting that reported outcomes, 34 more were excluded because they were narratives not written in scientific format (N=31), or were qualitative studies (N=3). The resulting 28 articles are included in this systematic review. Since several interventions resulted in more than one published article, these 28 articles represented 24 distinct studies.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of search results.

Characteristics of the studies are shown in Table 1. Only 1 was a randomized trial, most took place in the United States in adult medicine practices, and setting ranged from small private offices to large health systems. Follow-up ranged from three months to approximately four years.

Table 1.

Overview of included studies.

| Source | Provider specialty | Trial design | Country of study | Sponsorship | Provider setting | Number of practices | Number of providers | Follow up time period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belardi et al., 200426 | Family practice | Controlled before-after | USA | National government | Teaching practice | 1 (2 teams) | 6 (1.3 FTE) per team | 15 months |

| Bennett et al., 200927 * | Family practice | Uncontrolled before-after | USA | Not disclosed | Teaching practice | 1 | 49 | 14 months |

| Bundy et al., 200529 ** | Family practice | Uncontrolled before-after | USA | Non-profit | Varied (1 not-for-profit practice, 1 private practice, 2 practices owned by large health system) | 4 | 30 | 9 months |

| Dixon et al., 2006***30; Pickin et al. 2004***32 |

Family practice | Uncontrolled before-after | UK | National government | National Health Service practices | 462 | NR | 8–16 months |

| Kennedy et al., 200365 | Family practice | Uncontrolled before-after | USA | Not disclosed | Teaching practice | 1 | 12.8 FTE (incl non-MDs) | 5 months |

| Meyers et al., 200339 | Family practice | Uncontrolled before-after | USA | National government | US military | 1 | 9 | 4 months |

| Phan et al., 200946 | Family practice | Uncontrolled before-after | USA | Not disclosed | Teaching practice | 1 | 32 | 1 year |

| Rohrer et al., 200747 | Family practice | Cross-sectional | USA | Not disclosed | Network of community practices | 4 (2 AA, 2 control) | NR | 1 year |

| Salisbury et al., 200744 and 200733; Sampson et al., 200845; Pickin et al. 201051 |

Family practice | Controlled before-after | UK | National government | National Health Service practices | 48 (24 AA, 24 control) | mean 3.26 FTE per practice | 1 year |

| Mehrotra et al., 200831 | Family practice and general medicine | Uncontrolled before-after | USA | Non-profit | Health system with small offices | 6 (5 in analysis) | 2.8–8.8 FTEs/practice | 1–3 years |

| Armstrong, 200538 | General medicine | Uncontrolled before-after | USA | National government | Veterans Affairs | 862 | NR | 4 years |

| Boushon et al. 200628 | General medicine | Uncontrolled before-after | USA | Non-profit | Not reported | 17 | NR | 1 year |

| Lasser et al, 200536 | General medicine | Cross-sectional | USA | National government | Network of neighborhood health centers | 16 | 58 | n/a |

| Lewandowski et al., 200666; Solberg et al., 2004,25 and 200634; Sperl-Hillen et al, 200835 |

General medicine | Uncontrolled before-after | USA | Non-profit | Multispecialty medical group | 17 | 500 all specialties; 105 (99.6 FTE) primary care | 1–2 years |

| Lukas et al., 2004 37 | General medicine | Cross-sectional | USA | National government | Veterans Affairs | 78 | NR | n/a |

| Radel et al., 2001 40 *** | General medicine | Uncontrolled before-after | USA | Not disclosed | Health maintenance organization | 2 | 6 | 1 year |

| Subramanian et al., 2009 48 | General medicine | Controlled before-after | USA | National government | Teaching practice | 12 | ~100 | 1 year |

| Cherniack et al., 2007 42 | Geriatrics | Uncontrolled before-after | USA | Not disclosed | Veterans Affairs | 1 | 8 | 1 year |

| Mallard et al., 2004 41 | Pediatrics | Uncontrolled before-after | USA | Local government | Community health center | 1 | 2 | 6 months |

| O’Connor et al., 2006 43 | Pediatrics | Randomized controlled trial | USA | National government | Community health center | 1 | 10 | 4 months |

| Parente et al., 2005 67 | Pediatrics | Uncontrolled before-after | USA | Not disclosed | Teaching practice | 1 | 4 | 3 months |

NR, not reported; FTE, Full-time equivalent

Institute for Healthcare Improvement Access and Efficiency Collaborative study

“Institute for Healthcare Improvement QI initiative” May 2001–May 2002

Idealized Design of Clinical Office Practices study

The overall risk of bias in the studies was high (Appendix Tables 1 and 2). Only one study randomized physician participants, and this study was subject to substantial contamination and crossover bias. The remaining studies all included self-selected intervention groups in which baseline characteristics often differed between intervention and control groups. Furthermore at least 6 studies implemented other practice initiatives concurrently with advanced access. Less than half of studies reported basic measures of advanced access implementation such as time-to-third-available appointment.

An overview of results for each outcome is presented in Table 2. Details for each outcome follow.

Table 2.

Selected major outcomes following advanced access implementation, summary of studies

| Outcome | Number of studies | Overall result | Result among studies with concurrent control group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time to third available appointment | 8 | Statistically significant improvement in 5; any improvement in all 8; only 2 achieved access < 48 hours | N=2; significant improvement in both, one achieved < 48 hour access |

| No show rate | 11 | Statistically significant improvement in 5; >2% absolute improvement in 6; any improvement in 10 | N=4; significant improvement in 2, non-significant change in 2 |

| Patient satisfaction (overall) | 4 | Statistically significant improvement in 1; any improvement in 2 | N=0 |

| Patient satisfaction (appointments) | 4 | Statistically significant improvement in 0; any improvement in 2 Statistically significant worsening in 1 |

N=2; non-significant change in both |

| Continuity of care | 9 | Statistically significant improvement in 3; any improvement in 7 Worsening in 2 (none statistically significant) |

N=3; 1 significant improvement, 2 non-significant change |

| Healthcare utilization | 2 | No significant change in ED visits or hospitalizations; 1 study reduced visits to urgent care | N=1; no significant change |

Wait time for an appointment

Eleven articles describing 8 studies reported time-to-third-available appointment, the preferred metric for appointment availability (Table 3).25–35 Advanced access implementation was associated with a decrease in time-to-third-available appointment in all studies (range 1–32 days), and the decrease was statistically significant in all 5 studies (6 papers) in which statistical analysis was performed.25–27,32–34 A total of 5/8 (63%) studies achieved a mean time-to-third-available appointment of less than five days; 2 (25%) reached less than two days.32,33 One additional study of community health centers with open-access scheduling found that 49% of visits were to providers whose individual average time-to-third-available appointment was four days or less in the previous year.36 Two multisite studies found that a greater degree of advanced access implementation was significantly associated with reductions in wait time, although the effect was small.32,37 For example, in the VA, the degree of advanced access implementation accounted for 7% of the variance in wait time.37

Table 3.

Time to third available appointment

| Source | TTTA (days)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No-AA | AA | Δ in TTTA (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Belardi et al., 2004 26 | 21 | 4–7 | −14 to −17 | <.01 |

| Pickin et al. 2004*32 | 3.6 | 1.9 | −1.7 (−1.4 to −2.0) | <.05 |

| Bundy et al., 2005 29 | 36 | 4 | −32 (−20 to −44) | NR |

| Salisbury et al., 2007 33 | 2.9 | 1.6 | −1.1 (−2.2 to −0.1) | .04 |

| Bennet and Baxley, 2009 27 | 30.7 | 9.0 | −21.7 | <.0001 |

| Solberg et al., 2004†25 | Overall 17.8 | 4.2 | −13.6 | NR |

| Solberg et al., 2006†34 | Dep 19.5 | 4.5 | −15 | <.01 |

| Sperl-Hillen et al., 2008†35 | DM 21.6 | 4.2 | −14.7 | <.001 |

| Mehrotra et al., 2008 31 | 21 | 11 | −10 | NR |

| Boushon et al. 2006 28 | 23 | 10 | −13 | NR |

Similar results reported inDixon et al, 200630 from the same dataset

These articles report data from the same study.

TTTA, time-to-third-available appointment; AA, advanced access; Dep, depression; DM, diabetes.

Four additional studies examined time to next appointment only;38–41 two of these achieved an average next-available appointment time of two days or less.39,40 The VA system as a whole, using data from over 6 million patient visits, reported an improvement in next appointment availability from 42.9 days to 15.7 days.38

Physician and practice outcomes

Besides wait time, the only practice outcome frequently studied was no-show rate, which was reported in 11 studies (Table 4). The change in no-show rate ranged from −24% to 0 and was significantly decreased in five studies.29,36,41–43, Of note, three of these five studies served a population of patients with low socioeconomic status and all five had relatively high baseline no-show rates (16–43%).29,36,41

Table 4.

Physician and practice outcomes

| Source | No-show rate, practices without AA | No-show rate, practices with AA | Absolute change in no-show rate | P value | Visit volume, physician productivity, and compensation outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mallard et al., 200441 | 43% | 19% | −24% | <.0001 |

|

| O’Connor et al., 200643 | 21% | 9% | −12% | <.02 | |

| Cherniak et al., 200742 | 18% | 11% | −9% | 0 | |

| Bundy et al., 200529 | 16% | 11% | −5% (95% CI, −10 to −1) | <.05 | |

| Lasser et al, 200536 | 17.2% | 15.4% | −1.8% OR 0.80 (95% CI, 0.74 to 0.86) |

<.0001 | |

| Belardi et al., 200426 | 8.6%→7.8% | 9.2%→6.7% | −2.6% | NS |

|

| Salisbury et al., 200733 | 4.8→4.7% | 4.3→3.4% | −0.9% | 0.85 |

|

| Bennett et al., 200927 | 19.7% | 19.3% | −0.4% | NS | |

| Kennedy et al., 200365 | 10% | 6% | −4% | NR |

|

| Meyers et al., 200339 | Family practice: ~3.7% Pediatrics: ~3.5% Military medicine: ~2.9% Internal medicine: ~1.9% |

Family practice: ~2.4% Pediatrics: ~2.9% Military medicine: ~4% Internal medicine: 0% |

Family practice: ~−1.3% Pediatrics: ~−0.6% Military medicine: ~1.1% Internal medicine: ~−1.9% |

NR | |

| Mehrotra et al., 200831 | 14% | 14% | 0% | NR | |

| Radel et al., 200140 | “Financial performance improved” | ||||

| Solberg et al, 2004 and 200625,34, Lewandowski et al., 200666 |

Office visits/patient* CHD 8.2→8.9, p<.0001 DM 7.0→7.0, p=0.22 Dep 11.4→10.9, p<.001 Total healthcare costs per person CHD $16,631→$18736 DM $7607→$8407 Dep $6409→$7731 Financial performance

|

||||

| Subramanian et al., 200948 |

Office visits/patient OR 1.00 (95% CI, 0.92 to 1.08) |

Data from Solberg 2004. In Solberg 2006, results reported as 10.8→10.4, p < 0.01.

AA, advanced access; NS, not significant; NR, not reported; FTE, full-time equivalent; RVU, relative value unit; WRVU, work relative value unit.

Seven studies reported the impact of advanced access on visit volume, physician compensation or productivity outcomes; all reported neutral to positive results (Table 4).

Patient satisfaction

Four studies reported quantitative data pertaining to overall patient satisfaction (Table 5). Of these, one reported statistically significant improvement.29 Quantitative pre/post data on satisfaction with the appointment system were presented in four studies (Table 5).29,31,37,44,45 None showed significant improvement; in one, each 10% increase in proportion of same-day appointments was associated with an 8% reduction in satisfaction (OR 0.92, 95% CI, 0.90 to 0.94).45 However, a VA survey found that patient satisfaction appeared to be higher at facilities with shorter wait times (p=0.09).37

Table 5.

Patient satisfaction and advanced access implementation

| Study | Satisfaction, practices without AA* | Satisfaction, practices with AA* | Absolute Δ satisfaction | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Patient satisfaction: overall

|

||||

| Bundy et al., 2005 29 | 45% | 61% | 16% (95% CI, 0.2 to 30) | <.05 |

| Lewandowski et al., 2006 66 | 84% | 87% | 3% | NS |

| Solberg et al., 200425 | DM 36% | DM 55% | 19% | NR |

| Parente et al., 2005 67 | 6.21† | 6.08† | −.13 points | NS |

| Radel et al. 200140 | 72%5 | 95% | 23% | NR |

|

Patient satisfaction: appointment system

|

||||

| Salisbury et al. 200744, Sampson et al. 200845 | 52% | 52% | Adjusted OR 0.93 (95% CI, 0.67–1.28) | NS |

| Bundy et al., 200529 | 37% | 47% | 10% (95% CI, −9 to 29) | NS |

| Lukas et al., 2004 37 | 74% | 84% | 10% | 0.09 |

| Mehrotra et al., 2008 31 | 53% | 51% | −2% | NR |

AA, advanced access; DM, patients with diabetes only; NS, not significant; NR, not reported.

percent of respondents reported as “satisfied” or “highly satisfied” unless otherwise specified

Mean score on 1–7 scale with 7 = highest satisfaction

Continuity of care and loss to follow-up

The effect of advanced access scheduling on continuity of care was explored in 9 studies using multiple methods of assessing continuity (Table 6). Only two studies found significant decreases in continuity;43,46 of these, one noted that a provider in the open access group was on maternity leave during the brief 4 month period of study follow-up, potentially accounting for this finding.43

Table 6.

Clinical outcomes of advanced access

| Source | Continuity of care, practices without AA | Continuity of care, practices with AA | Change in continuity | P value | Urgent Care/ED/hospital use without AA→with AA | Other clinical outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belardi et al., 2004 26 | ~75% | >90% | ~15% | <.015 | ||

| Parente et al., 2005 67 | 69.8% | 91.4% | 24.1% | <.000 | ||

| Solberg et al., 200425, Solberg et al, 200634, Sperl-Hillen et al., 2008 35 | COC index19 CHD: 0.66 DM: 0.68 Dep: 0.60 |

COC index19 CHD: 0.72 DM: 0.73 Dep: 0.63 |

CHD: 0.06 DM: 0.05 Dep: 0.03 |

<.0001 <.0001 <.0001 |

1 or more visits to urgent care CHD 13.5%→8.6% p<.0001 DM 17.5%→12.4% p<.0001 Dep 31.8%→22.8% p<.0001 1 or more visits to ED* CHD 51.5%→50.9% p=0.068 DM 14.4%→15.1% p=0.078 Dep 14.9%→16.9% p=0.15 1 or more ED or urgent care visit DM 41%→37.6%, p<.001 1 or more hospitalizations* CHD 58.4%→57.3% p=0.002 DM 9.5%→9.7% p=0.70 Dep 7.7%→8.9% p=0.13 Mental health ED visit or hospitalization Dep 6.5%→6.3% p=.34 |

Diabetes quality: A1c <7% 44.4→52.7% p<.001 LDL<100 29.8→38.7% p<.001 Depression quality Continuation of new medication for 180 days 46.2%→50.8% p<.001 |

| Phan et al., 2009 46 | UPC21 0.56 MMCI20 0.49 |

UPC21 0.54 MMCI20 0.43 |

UPC21 -0.02 MMCI20 −0.06 |

0.13 0.001 |

||

| Bundy et al., 2005 29 | 76% | 89% | 13% (95% CI, −7 to 32) | NS | ||

| O’Connor et al., 2006 43 | 75% | 60% | −15% | NS |

On-time immunization rate 74% in AA group 74% in non-AA group |

|

| Salisbury et al., 2007 33; Pickin et al., 201051 |

COC index18 0.43→0.46 |

COC index18 0.43→0.40 |

Adjusted diff .003 (−0.07 to 0.07) |

0.93 |

Antibiotic prescribing Reduction in monthly prescriptions of 0.9 items/1,000 patients AA relative to controls (95% CI, −2.2 to 0.4, p=0.16) |

|

| Meyers et al., 2003 39 | ~38% | ~45% | ~7% | NR | ||

| Bennett et al., 2009 27 | 64.0% | 68.2% | 4.2% | NR | ||

| Subramanian et al., 200948 |

ED or urgent care visits OR 0.97 (95% CI 0.92 to 1.02) Hospitalizations OR 0.95 (95% CI 0.81 to 1.11) |

Diabetic quality A1c −0.12% (95% CI −0.21 to −0.03) SBP 6.4 (95% CI 5.4 to 7.5) LDL −0.2 (95% CI −2.0 to 1.5) |

||||

| Radel et al, 200140 |

Cardiovascular quality LDL<100 52%→75% HTN BP control <140/86 64%→96% Diabetes quality Hgb A1c ≤ 7.5 65.5%→76.6% |

Data are from Solberg 2004. Solberg 2006 using same dataset reports 1 or more visits to the ED for depression as 25.6→27.3, p=.13 and 1 or more hospitalizations as 19.9→21.7 p<.05.

AA, advanced access; COC, continuity of care; UPC, Usual Provider Continuity Index; MMCI, Modified, Modified Continuity Index; CHD, coronary heart disease; DM, diabetes; Dep, depression; ED, emergency department; OR, odds ratio; NR, not reported; NS, reported as not significant.

Loss to follow-up was rarely evaluated and results were mixed. Two studies found no consistent difference in loss to follow-up between advanced access and traditional scheduling.26,47 One study of patients with depression found more patients had primary care follow-up after advanced access implementation (33.0% vs. 15.4%, p=.001), but also noted that fewer followed up after a mental health hospitalization (50.3% vs. 65.9%, p=.001).34 An advanced access VA practice found that 19% of geriatric patients failed to arrange follow-up appointments; however, this study did not report loss to follow-up prior to advanced access implementation.42

Clinical outcomes

Emergency Department (ED), urgent care, and/or hospitalization rates under advanced access were quantitatively reviewed in four articles about two studies (Table 6).25,34,35,48 Urgent care visits decreased significantly in one study,25 but neither study found a consistent effect on ED visits or hospitalizations.

Three studies examined clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. All found improvements in glycosylated hemoglobin control (2 statistically significant but only 1 clinically significant),35,40,48 one found significant improvement in lipid control35 and another found significant worsening of blood pressure control.48 A pre-post report of advanced access implementation in the VA reported dramatic improvement in a wide variety of clinical performance measures;38 however, the VA implemented numerous other quality improvement activities during this period which were not accounted for.49,50 A variety of other outcomes were assessed in 1–2 studies each (Table 6).

Effect of success of AA implementation on outcomes

We assessed whether outcomes were better for studies with more successful implementations (shorter time-to-third-available appointment). There was a positive but non-significant correlation between time-to-third-appointment and no show rate in the five studies reporting both measures (R2=0.69, p=0.10). We were unable to perform similar analyses for other outcomes due to lack of data.

Discussion

This systematic review investigated the impact of advanced access scheduling on no-show rates, practice finances, patient satisfaction, continuity of care, healthcare utilization and preventive care. In summary, among 28 articles describing 24 implementations, we found that the time to the third available appointment consistently decreased with advanced access scheduling, although very few studies were able to achieve same-day access. Overall, advanced access yielded neutral to small positive improvements in no-show rates, continuity and patient satisfaction, while effects on clinical outcomes were mixed. It is worth noting that these studies report outcomes of advanced access as it has been applied in the “real world.” The limited benefits we found may therefore not be attributable to a failure of the advanced access concept itself so much as imperfect implementation (as evidenced by the limited number of studies that were able to achieve same day access). Nonetheless, since most clinicians would not be likely to apply this intervention in a randomized controlled trial setting, it is useful to examine its real-world effectiveness.

Any systematic review is dependent on the quality of the studies it evaluates. The studies included in this analysis were rarely conducted in a rigorous fashion. Only one was a randomized trial and only six others had a concurrent control group. The remaining studies were conducted in a pre/post fashion without accounting for secular trends or other concurrent quality improvement initiatives, making it impossible to isolate the effect of advanced access scheduling on outcomes. This was particularly problematic for the three studies set in the Veterans Affairs system and the four studies of practices participating in Institute for Healthcare Improvement programs, in which numerous concurrent quality improvement activities were undertaken. Moreover, the limited reporting of most studies made it difficult to assess the level of advanced access achieved, while lack of statistical analysis often made it difficult to interpret the results. Very few studies included outcomes of clinical relevance.34,35,43,48,51 The wide variety of practice settings combined with the paucity of data about most outcomes prohibited us from distinguishing which effects were attributable to advanced access itself versus to local context and variability in implementation. Finally, publication bias is always of concern although we did identify both positive and negative reports.

Despite the fact that the time-to-third-available appointment declined in all studies, one of the most striking findings was the low number of practices that achieved true same-day access. Only a quarter of studies reporting time-to-third-available appointment achieved two-day access. It is possible that some of the 16 studies that did not report time-to-third-available appointment achieved successful implementations, and it is also possible that individual sites within multi-site studies may also have been successful. Nonetheless, on balance our results suggest that successful implementation of this scheduling system is challenging. Reasons provided by authors for failure included increased demand of new patients due to physician shortages, difficulty scheduling physicians to match demand, provider resistance to same-day scheduling, unexpected decreases in appointment supply due to provider illness or departure, expected changes in supply such as maternity leave and vacations, and irregular schedules of medical trainees.16,26,31 Murray and Tantau’s descriptions of advanced access do specifically describe strategies to meet these predictable roadblocks,12,13,52 yet they do not seem to have been readily overcome in practice.

No-show rates declined as time-to-third-available appointment declined. However, improvements in no-show rates were less robust than those observed in time-to-third-available appointment, and were chiefly seen in studies of underserved populations with a high baseline no-show rate. For practices with lower baseline no-show rates, advanced access did not appear to provide significant benefit. It is possible that there is a “floor” no-show rate below which improvements are unlikely. Regardless, advanced access did not provide the large benefits to no-show rates that have been theoretically postulated.

Surveys of providers show they fear that advanced access will decrease continuity if patients are encouraged to be seen immediately by whichever physician is available.16 Our results do not support this concern. Continuity of care decreased markedly in only one of 7 studies, a residency site in which irregular house staff schedules made continuity of care extremely challenging without the ability to pre-book appointments.43 Conversely, proponents of advanced access contend that the system will improve continuity by improving each provider’s availability.12,53 Our findings only partially support this theory: advanced access improved continuity in only half of the studies, and in one study, the improvement in continuity was only weakly associated with improvements in wait time.35

Despite the near-universal reduction in wait time, patient satisfaction with overall care or with the scheduling system did not consistently improve. Clinicians often assume that shorter wait times for appointments will automatically lead to improved patient satisfaction. In the VA system, patient satisfaction was positively correlated with shorter wait times.37 However, numerous surveys of patients in the UK have found that scheduling an appointment at a convenient time is more important to patients than speed of access, unless they are presenting with a new health problem.44,54–56 These results are consistent among working patients, patients with chronic illness, women and older patients.55 Furthermore, one survey found that patients were no more likely to get the type of appointment they wanted (e.g. with a particular provider, provider type, or time) in the advanced access system than in practices with conventional scheduling systems.44 In fact, satisfaction decreased 8% for every 10% increase in same-day appointments available.45 Thus, a strict focus on reducing wait time for appointments by embargoing appointments – such as has been reported in the National Health Service57 – may not be a patient-centered approach to improving scheduling systems. Although this is not the intent of advanced access, which should be able to accommodate requests for appointments, qualitative studies have found that real-world implementations of advanced access often focus on same day access to the exclusion of other core principles.58

While advanced access was not designed to improve clinical outcomes per se, as with any intervention it is necessary to ensure that it does not harm patients. Additionally, since prompt care and continuity improve clinical outcomes,59–62 advanced access might be expected to have clinical benefits. Few studies evaluated clinical outcomes, and here the results were mixed. Of the four studies analyzing emergency room/urgent care use, only one showed a decrease in use of these services. Diabetic care was unaffected or mildly improved.35 On-time immunization rates for children were unchanged.43 Overall then, it does not appear that advanced access in itself is a particularly robust method of improving clinical outcomes. However, we found no compelling evidence of harm.

On the other hand, we did find some evidence to support the concern that some patients may be more likely to be lost to follow-up in an advanced access system.32 In one study, nearly one fifth of geriatric patients failed to make follow-up appointments as requested, although pre-intervention data were not presented.42 While our systematic review focused on primary care only, a specialty care practice implementing advanced access noted that 50% of patients failed to call for follow-up appointments, indicating that losing patients to follow-up is of concern in specialty settings as well.63

As advanced access scheduling gains popularity, it is important to have a realistic expectation of its potential benefits.64 We found that most practices attempting advanced access reduce wait time substantially, although few achieve same-day access. For practices with high no-show rates, advanced access appears to yield marked improvements; however, it is less effective for practices with lower baseline no-show rates. Patient satisfaction does not consistently improve and may be contingent upon how the advanced access model is applied. Most importantly, data about clinical outcomes and potential harm such as loss to follow-up is lacking. A large randomized trial of open-access scheduling that includes patient outcomes such as satisfaction, continuity of care, quality of care and healthcare utilization, along with a rigorous assessment of loss to follow-up, would be valuable to further our understanding of the utility of this scheduling system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: During the period this study was conducted, Dr. Horwitz was supported by CTSA Grant Number UL1 RR024139 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH roadmap for Medical Research. Both Dr. Ross and Dr. Horwitz are currently supported by the National Institute on Aging (K08 AG032886, K08 AG038336) and by the American Federation of Aging Research through the Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award Program. No funding source had any role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

This publication was made possible by CTSA Grant Number UL1 RR024139 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH roadmap for Medical Research. This project was also supported by Award Numbers K08 AG038336 and K08 AG032886 from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and by the American Federation on Aging Research (AFAR) through the Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award Program. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR, NIA, AFAR or NIH. No funding source had any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. All authors had full access to all the data in the study. LIH takes full responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

An earlier version of this work was presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine 31st Annual Meeting in Pittsburgh, PA, April 10, 2008.

Conflict of interest

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that (1) JSR and LIH have support from the National Institute on Aging and the National Center for Research Resources for the submitted work, (2) KDR, JSR, LIH have no relationships with any company that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; (3) their spouses, partners, or children have no financial relationships that may be relevant to the submitted work; and (4) KDR, JSR and LIH have no non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

References

- 1.Murray M, Tantau C. Redefining open access to primary care. Manag Care Q. 1999;7:45–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.George A, Rubin G. Non-attendance in general practice: a systematic review and its implications for access to primary health care. Fam Pract. 2003 Apr;20(2):178–184. doi: 10.1093/fampra/20.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merritt HA. Summary report: 2009 Survey of Physician Appointment Wait Times. 2009 http://www.merritthawkins.com/pdf/mha2009waittimesurvey.pdf.

- 4.Trude S, Ginsburg PB. An update on Medicare beneficiary access to physician services. Issue Brief Cent Stud Health Syst Change. 2005 Feb;93:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prentice JC, Pizer SD. Delayed access to health care and mortality. Health Serv Res. 2007 Apr;42(2):644–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00626.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rust G, Ye J, Baltrus P, Daniels E, Adesunloye B, Fryer GE. Practical barriers to timely primary care access: impact on adult use of emergency department services. Arch Intern Med. 2008 Aug 11;168(15):1705–1710. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.15.1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.California HealthCare Foundation. [Accessed Nov 1, 2010];Overuse of emergency departments among insured Californians. 2006 http://www.chcf.org/publications/2006/10/overuse-of-emergency-departments-among-insured-californians.

- 8.Institute for Healthcare Improvement. [Accessed July 20, 2010];Advanced Access: Reducing Waits, Delays and Frustrations in Maine. 2006 http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/OfficePractices/Access/ImprovementStories/AdvancedAccessReducingWaitsDelaysandFrustrationinMaine.htm.

- 9.Pulse Magazine. [Accessed February 8, 2011];Government Issues Advanced Access Demand. 2007 http://www.pulsetoday.co.uk/story.asp?storycode=4116322.

- 10.The Scottish Government. [Accessed February 8, 2011];GP Patient Experience Survey Access results for Practices 2010. 2010 http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/Doc/924/0099312.pdf.

- 11.Singer IA, Regenstein M. Advanced Access: Ambulatory Care Redesign and the Nation’s Safety Net. Washington, DC: National Association of Public Hospitals; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray M, Tantau C. Same-day appointments: exploding the access paradigm. Fam Pract Manag. 2000 Sep;7(8):45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray M. Modernising the NHS: Patient care: access. BMJ. 2000;320:1594–1596. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7249.1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boelke C, Boushon B, Isensee S. Achieving open access: the road to improved service & satisfaction. Med Group Manage J. 2000 Sep–Oct;47(5):58–62. 64–56, 68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salisbury C. Evaluating open access: problems with the program or the studies? Ann Intern Med. 2008 Dec 16;149(12):910. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-12-200812160-00015. author reply 911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahluwalia S, Offredy M. A qualitative study of the impact of the implementation of advanced access in primary healthcare on the working lives of general practice staff. BMC Fam Pract. 2005 Sep 27;6:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-6-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray M, Berwick DM. Advanced access: reducing waiting and delays in primary care. JAMA. 2003 Feb 26;289(8):1035–1040. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.8.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bice TW, Boxerman SB. A quantitative measure of continuity of care. Med Care. 1977 Apr;15(4):347–349. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197704000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Given CW, Branson M, Zemach R. Evaluation and application of continuity measures in primary care settings. J Community Health. 1985 Spring;10(1):22–41. doi: 10.1007/BF01321357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magill MK, Senf J. A new method for measuring continuity of care in family practice residencies. J Fam Pract. 1987 Feb;24(2):165–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patten RC, Friberg R. Measuring continuity of care in a family practice residency program. J Fam Pract. 1980 Jul;11(1):67–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Review Group. [Accessed Sep 7, 2010];Risk of bias criteria. 2009 http://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-resources-review-authors.

- 23.Ogrinc G, Mooney SE, Estrada C, et al. The SQUIRE (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence) guidelines for quality improvement reporting: explanation and elaboration. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008 Oct;17( Suppl 1):i13–32. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.029058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.West S, King V, Carey TS, et al. Systems to rate the strength of scientific evidence. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) 2002 Mar;(47):1–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solberg LI, Maciosek MV, Sperl-Hillen JM, et al. Does improved access to care affect utilization and costs for patients with chronic conditions? Am J Manag Care. 2004 Oct;10(10):717–722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Belardi FG, Weir S, Craig FW. A controlled trial of an advanced access appointment system in a residency family medicine center. Fam Med. 2004 May;36(5):341–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bennett KJ, Baxley EG. The effect of a carve-out advanced access scheduling system on no-show rates. Fam Med. 2009 Jan;41(1):51–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boushon B, Provost L, Gagnon J, Carver P. Using a virtual breakthrough series collaborative to improve access in primary care. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006 Oct;32(10):573–584. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(06)32075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bundy DG, Randolph GD, Murray M, Anderson J, Margolis PA. Open access in primary care: results of a North Carolina pilot project. Pediatrics. 2005 Jul;116(1):82–87. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dixon S, Sampson FC, O’Cathain A, Pickin M. Advanced access: more than just GP waiting times? Fam Pract. 2006 Apr;23(2):233–239. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mehrotra A, Keehl-Markowitz L, Ayanian JZ. Implementing open-access scheduling of visits in primary care practices: a cautionary tale. Ann Intern Med. 2008 Jun 17;148(12):915–922. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-12-200806170-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pickin M, O’Cathain A, Sampson FC, Dixon S. Evaluation of advanced access in the national primary care collaborative. Br J Gen Pract. 2004 May;54(502):334–340. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salisbury C, Montgomery AA, Simons L, et al. Impact of Advanced Access on access, workload, and continuity: controlled before-and-after and simulated-patient study. Br J Gen Pract. 2007 Aug;57(541):608–614. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Solberg LI, Crain AL, Sperl-Hillen JM, Hroscikoski MC, Engebretson KI, O’Connor PJ. Effect of improved primary care access on quality of depression care. Ann Fam Med. 2006 Jan–Feb;4(1):69–74. doi: 10.1370/afm.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sperl-Hillen JM, Solberg LI, Hroscikoski MC, Crain AL, Engebretson KI, O’Connor PJ. The effect of advanced access implementation on quality of diabetes care. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008 Jan;5(1):A16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lasser KE, Mintzer IL, Lambert A, Cabral H, Bor DH. Missed appointment rates in primary care: the importance of site of care. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2005 Aug;16(3):475–486. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lukas CV, Meterko M, Mohr D, Seibert MN. [Accessed 25 Aug, 2010];The implementation and effectiveness of advanced clinic access. 2004 http://www.colmr.research.va.gov/publications/reports/ACA_FullReport.pdf.

- 38.Armstrong B, Levesque O, Perlin JB, Rick C, Schectman G. Reinventing Veterans Health Administration: focus on primary care. J Healthc Manag. 2005 Nov–Dec;50(6):399–408. discussion 409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meyers ML. Changing business practices for appointing in military outpatient medical clinics: the case for a true “open access” appointment scheme for primary care. J Healthc Manag. 2003 Mar–Apr;48(2):125–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Radel SJ, Norman AM, Notaro JC, Horrigan DR. Redesigning clinical office practices to improve performance levels in an individual practice association model HMO. J Healthc Qual. 2001 Mar–Apr;23(2):11–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2001.tb00330.x. quiz 15, 52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mallard SD, Leakeas T, Duncan WJ, Fleenor ME, Sinsky RJ. Same-day scheduling in a public health clinic: a pilot study. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2004 Mar–Apr;10(2):148–155. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200403000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cherniack EP, Sandals L, Gillespie D, Maymi E, Aguilar E. The use of open-access scheduling for the elderly. J Healthc Qual. 2007 Nov–Dec;29(6):45–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2007.tb00224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Connor ME, Matthews BS, Gao D. Effect of open access scheduling on missed appointments, immunizations, and continuity of care for infant well-child care visits. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006 Sep;160(9):889–893. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.9.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salisbury C, Goodall S, Montgomery AA, et al. Does Advanced Access improve access to primary health care? Questionnaire survey of patients. Br J Gen Pract. 2007 Aug;57(541):615–621. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sampson F, Pickin M, O’Cathain A, Goodall S, Salisbury C. Impact of same-day appointments on patient satisfaction with general practice appointment systems. Br J Gen Pract. 2008 Sep;58(554):641–643. doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X330780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Phan K, Brown SR. Decreased continuity in a residency clinic: a consequence of open access scheduling. Fam Med. 2009 Jan;41(1):46–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rohrer JE, Bernard M, Naessens J, Furst J, Kircher K, Adamson S. Impact of open-access scheduling on realized access. Health Serv Manage Res. 2007 May;20(2):134–139. doi: 10.1258/095148407780744679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Subramanian U, Ackermann RT, Brizendine EJ, et al. Effect of advanced access scheduling on processes and intermediate outcomes of diabetes care and utilization. J Gen Intern Med. 2009 Mar;24(3):327–333. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0888-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kizer KW, Demakis JG, Feussner JR. Reinventing VA health care: systematizing quality improvement and quality innovation. Med Care. 2000 Jun;38(6 Suppl 1):I7–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jha AK, Perlin JB, Kizer KW, Dudley RA. Effect of the transformation of the Veterans Affairs Health Care System on the quality of care. N Engl J Med. 2003 May 29;348(22):2218–2227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa021899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pickin M, O’Cathain A, Sampson F, Salisbury C, Nicholl J. The impact of Advanced Access on antibiotic prescribing: a controlled before and after study. Fam Pract. 2010 Jun 13; doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmq039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murray M, Bodenheimer T, Rittenhouse D, Grumbach K. Improving timely access to primary care: case studies of the advanced access model. JAMA. 2003 Feb 26;289(8):1042–1046. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.8.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tantau C. Accessing patient-centered care using the advanced access model. J Ambul Care Manage. 2009 Jan–Mar;32(1):32–43. doi: 10.1097/01.JAC.0000343122.15467.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gerard K, Salisbury C, Street D, Pope C, Baxter H. Is fast access to general practice all that should matter? A discrete choice experiment of patients’ preferences. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2008 Apr;13(Suppl 2):3–10. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2007.007087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rubin G, Bate A, George A, Shackley P, Hall N. Preferences for access to the GP: a discrete choice experiment. Br J Gen Pract. 2006 Oct;56(531):743–748. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pascoe SW, Neal RD, Allgar VL. Open-access versus bookable appointment systems: survey of patients attending appointments with general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract. 2004 May;54(502):367–369. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anonymous. Patients denied advance bookings. BBC News; Jun 20, 2005. [Accessed 29 Jul 2010]. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/4112390.stm. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pope C, Banks J, Salisbury C, Lattimer V. Improving access to primary care: eight case studies of introducing Advanced Access in England. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2008 Jan;13(1):33–39. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2007.007039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mercer CH, Sutcliffe L, Johnson AM, et al. How much do delayed healthcare seeking, delayed care provision, and diversion from primary care contribute to the transmission of STIs? Sex Transm Infect. 2007 Aug;83(5):400–405. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.024554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saultz JW, Lochner J. Interpersonal continuity of care and care outcomes: a critical review. Ann Fam Med. 2005 Mar–Apr;3(2):159–166. doi: 10.1370/afm.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cheng SH, Chen CC, Hou YF. A longitudinal examination of continuity of care and avoidable hospitalization: evidence from a universal coverage health care system. Arch Intern Med. 2010 Oct 11;170(18):1671–1677. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Walraven C, Taljaard M, Etchells E, et al. The independent association of provider and information continuity on outcomes after hospital discharge: implications for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2010 Sep;5(7):398–405. doi: 10.1002/jhm.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Newman ED, Harrington TM, Olenginski TP, Perruquet JL, McKinley K. The rheumatologist can see you now”: Successful implementation of an advanced access model in a rheumatology practice. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 Apr 15;51(2):253–257. doi: 10.1002/art.20239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Auerbach AD, Landefeld CS, Shojania KG. The tension between needing to improve care and knowing how to do it. N Engl J Med. 2007 Aug 9;357(6):608–613. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb070738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kennedy JG, Hsu JT. Implementation of an open access scheduling system in a residency training program. Fam Med. 2003 Oct;35(9):666–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lewandowski S, O’Connor PJ, Solberg LI, Lais T, Hroscikoski M, Sperl-Hillen JM. Increasing primary care physician productivity: A case study. Am J Manag Care. 2006 Oct;12(10):573–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Parente DH, Pinto MB, Barber JC. A pre-post comparison of service operational efficiency and patient satisfaction under open access scheduling. Health Care Manage Rev. 2005 Jul–Sep;30(3):220–228. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200507000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.