Abstract

Objective

The rise in popularity of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in the United States has stimulated increasing interest in researching CAM. One challenge to this research is determining the optimal dose of a CAM intervention. T'ai Chi Chuan (TCC) has received considerable attention as a mind–body practice; however, it remains unclear exactly how much TCC practice is necessary to elicit a discernable effect.

Design

In this review, we selected 19 studies and examined the variation in the number and length of training sessions. Secondary and tertiary aims include examining attendance rates for each intervention and the instructions given to participants regarding home-based practice. The degree to which investigators monitored participants' home-based practice was also examined.

Results

In the intent-to-treat analyses, the median time of TCC practice was 2877 minutes intended for participants across the selected interventions. Fourteen (14) of the publications provided information about participant attendance in the original publication, 2 provided additional information through further author inquiry, and 3 commented on TCC practice outside of the structured class environment through author inquiry.

Conclusions

The data reported are inconsistent in reported attendance and home-based practice rates, making it difficult to speculate on the relationship between the amount of TCC and intervention effects. Further research could contribute to this area by determining the optimal dose of TCC instruction.

Introduction

The widespread use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) by the U.S. public1,2 warrants basic and clinical research to determine the safety and efficacy of CAM practices3 as well as identification of the optimal dose for specific CAM modalities. Lack of confirmed treatment schedule and dosing information in clinical efficacy studies may result in insufficient or misleading study outcomes. For example, randomized clinical trials of saw palmetto may have not shown effects due to inadequate dose of the identified active ingredient.4

As data on physiologic correlates of t'ai chi practice are mounting, such as recent findings of an augmented immune response to a viral challenge,5 the optimal dosing may be particularly timely for T'ai Chi Chuan (TCC). A review of selected TCC interventions reported that the number and length of training sessions vary widely across studies.6 Thus, the primary objective of this study was to review the variation in the number and length of training sessions investigated in randomized clinical trials of TCC. A secondary objective was to examine the reporting of participants' attendance rates to scheduled intervention classes.

The extent to which study participants practice the modality on their own, independent of scheduled training sessions, can further complicate the issue of dose. Thus, a third objective of this study was to examine the extent to which study participants were encouraged or discouraged from practicing on their own (instruction given regarding home-based practice). Included in this objective was the assessment of the investigators' recording and reporting of participants' home-based practice.

Methods

A computerized search of studies investigating the clinical effects of TCC of publications in English was conducted in the PubMed, EMBASE, Allied and Complementary Medicine (AMED), and Manual, Alternative and Natural Therapy (MANTIS) databases. Search terms included “Tai Chi,” “clinical trial,” “randomized controlled trial evaluation study,” “meta-analysis,” “cross-sectional studies,” “follow-up studies,” “cohort studies,” “cohort analysis,” “prospective studies,” “case-control studies,” “controlled study,” and “comparative study” and have been used previously.6 The inclusion criteria for the selected group of studies was defined as: randomized prospective study of TCC-naïve participants, defined TCC intervention, at least one control group, and adequate sample size allowing for statistical analysis of study outcomes.

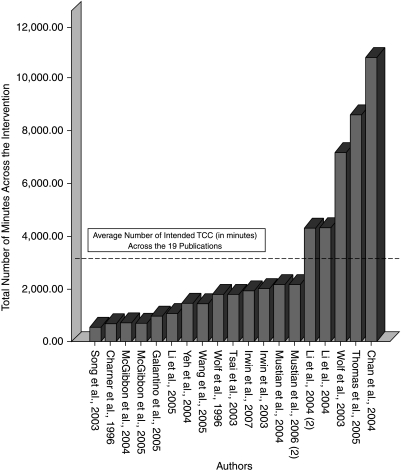

Within the selected publications, the total number of minutes of each TCC session, multiplied by the number of sessions assigned by the intervention (i.e., 3 hour-long sessions per week for 12 weeks = 2160 minutes) was calculated for each study in the intent-to-treat analysis (Fig. 1). This method was selected to examine the intended treatment program across the selected TCC interventions, irrespective of dropouts or low/high attendance rates.

FIG. 1.

Intent-to-treat summary of t'ai chi training.

Attendance rates to the intervention classes were examined across the selected publications. Fourteen (14) publications reported attendance rates and were included in the mean analyses (calculated by multiplying the reported average attendance rate by the number of intended minutes for each intervention). Instructions given to participants regarding home-based practice were also examined. Some published studies did not report attendance rates or further instructions about practicing TCC outside of the scheduled intervention. Where data regarding the attendance rate or instructions regarding practice were not included in the publication, an effort was made to contact authors to obtain the missing information by individualized surveys sent over email. Two (2) of the authors provided additional information over the phone.

Results

The computerized literature search yielded a total of 93 published studies between 1989 and 2006. Reviews, retrospective studies, and 2 studies that applied a combination regimen with TCC movements were removed from further analysis. Nineteen (19) of these studies were included in this review as these studies met the inclusion criteria (2 of these studies7,8 were reported across 2 separate publications9,10), yielding a final sample of 19 publications (Table 1).

Table 1.

Attendance Rates and Instructions for Home-Based Practice of Selected T'ai chi Interventions

| Author/reference | Patient population | Number of classes/regimen | Attendance rates (from publication unless otherwise specified) | Instructions regarding outside TCC practice | Outcome/results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mustian et al., 20048,a | 21 breast cancer survivors | 3 (60 minutes) × weeks for 12 weeks | Among the TCC participants, 11 completed all study requirements, with a 72% exercise attendance/compliance rate, while 10 psychosocial support group participants completed all study requirements, with a 67% attendance rate | Told not to change their physical activity at all during the course of the trial. According to self-report data, 80% (n = 8) of the women completing the support group intervention adhered to this requirement and 100% (n = 11) of the TCC group adhered to not changing physical activity | TCC group exhibited improvement in Health Related Quality of Life and self-esteem from baseline to 6 and 12 weeks, while the support group exhibited declines |

| Mustian et al., 200610,a | 21 breast cancer survivors | 3 (60 minutes) × weeks for weeks | Same as above | Same as above | The TCC group demonstrated significant improvement in aerobic capacity, muscular strength, and flexibility at 12 weeks compared to physical activity control |

| Irwin et al. 200330 | 36 healthy adults with history of chickenpox | 45 minutes, 3× per week for 15 weeks | Of the total possible sessions (N = 45), median compliance was 39 | Investigators confirmed via e-mail that there was no alteration in outside physical activity by participant self-reports | Varicella zoster-specific cell-mediated immunity increased 50% in TCC group; significant increase in SF-36 scores were higher with TCC |

| Irwin et al. 20075 | 112 healthy older adults | 40 minutes, 3× per week for 16 weeks | 91% of participants completed the intervention. TCC participants attended a mean ± standard deviation of 83% ± 20%, and health education subjects attended 80% ± 20% of all sessions | Specific instructions not listed; from publication, “TCC participants showed a significant increase in the number of minutes of at-home practice per week” | TCC group demonstrated varicella zoster virus immunity comparable to that of the traditional varicella vaccine; together the vaccine and the TCC intervention had an additive effect compared to a health education group |

| Song et al. 200311 | 72 osteoarthritis patients | 12 weeks; 1st 2 weeks: 3 classes per week; then only once a week with home practice encouraged | 41% overall dropout rate | After 2 weeks the exercise group came to the supervised session once a week; TCC 20 minutes daily at least 3 times a week at home for the following 10 weeks. Phone contact to encourage regular performance, and daily log to record the frequency of exercise. | TCC group experienced less stiffness, and reported fewer difficulties in physical functioning |

| The control subjects were also contacted each week by telephone to confirm they were not taking part in any other exercise activities. Home practice not reported | |||||

| Yeh et al. 200414 | 30 patients with chronic stable heart failure | 2 (1 hour) × week for 12 weeks | Not reported | From publication: “Participants were encouraged to practice at home at least three times per week….More than three quarters (77%) of patients reported some regular physical activity at home, such as walking. The duration of exercise ranged from 5 to 65 minutes, and the frequency ranged from once a week to daily” | At 12 weeks, TCC group showed improvement in QoL scores, increased 5-minute walk test, and decreased serum B-type natriuretic peptide levels compared to control group |

| Wolf et al. 199613 | 200 elderly (70 and older) patients | 15 weeks—not clear | Not reported in detail—makeup classes resulted in a very high attendance rate | From publication: “Subjects were encouraged to practice at least 15 min twice a day, but home practice was not monitored” | Lowered BP in TCC group; fear of falling responses and intrusiveness responses were reduced after the TCC intervention compared with the ED group; after adjusting for fall risk factors, TCC was found to reduce the risk of multiple falls by 47.5% |

| Wolf et al. 200315 | 311 elderly (70–97) patients | The TCC group met 2 sessions/week at increasing durations starting at 60-minute contact time and progressing to 90 minutes over the course of 48 weeks | From publication: “The average standard deviation attendance in the [TCC] group was 76 ± 19% (range: 6–100%), whereas the average attendance for a statistical group was 81 ± 17% (range: 10–100%)”; when attendance was evaluated in a statistical model adjusted for center, a statistically significant effect of attendance (p = 0.006) was found | From inquiry: outside practice was encouraged; rates not recorded | Risk ratio of falling not statistically significant in TCC group |

| Li 20047,a | 256 physically inactive older adults | 3 (∼60 minutes) × week for 6 months | Median compliance was 61 sessions for both groups, ranging from 30 to 77 sessions for TCC participants and from 35 to 78 sessions for the controls (Noted in publication: No statistical differences in the above baseline variables were found between those who attended intervention classes and those who did not attend.) | From author inquiry: “Participants in both conditions were encouraged to practice movements learned in class. However, we did not monitor the amount or time of out-of-class practice during the trial just as we did in the other study” | TCC group showed improvements in measures of functional balance at the intervention endpoint significantly reduced their risk of falls during the 6-month postintervention period, compared to control group |

| Li et al. 200416,a | 118 patients ages 60–92 | 60-minute session, 3× per week, for 6 months | Same as above | Same as above | TCC group demonstrated sig. improvements in sleep quality, latency, duration, efficiency, sleep disturbances |

| Li et al. 20059,a | 256 community-dwelling elderly patients | 1-hour classes, 3× week for weeks | Median compliance was 61 sessions for both groups, ranging from 30 to 77 sessions for TCC participants and from 35 to 78 sessions for the controls | Same as above | Risks for falls was 55% lower in the TCC group than the stretching control |

| Wang et al. 200531 | 20 RA patients | TCC 2× per week for 1-hour sessions for 12 weeks | Not reported due to limited space for publication. | Not reported due to limited space for publication | TCC group improved in physical functioning |

| McGibbon et al. 200418 | 26 patients with vestibulopathy | Each group met once weekly for 10 weeks for ∼70 minutes | From correspondence: 88% attendance to TCC intervention; 65% attendance rate for vestibulopathy control | From inquiry: outside practice was encouraged, and rates were recorded; follow-up analysis requested from author | Improvements on whole-body and footfall stability, not gaze stability for TCC compared to the VR group |

| McGibbon et al. 200517 | 36 older adults with vestibulopathy | Same as above | Same as above | Same as above | Gait-time improvements were seen in both groups, Between-group analysis suggests TCC group improvements are due to reorganized lower-extremity neuromuscular patterns (faster gait and reduced excessive hip compensation) |

| Thomas et al. 200519 | 207 elderly participants | 1 hour; 3× week for 12 months | 81% attendance to the TCC intervention; only 76% to the resistance training | From inquiry: “The participants were encouraged to practice at home, but we did not document participation at home” | No difference between TCC group, control, and resistance exercise group and control in primary outcomes; only result: improvements in insulin sensitivity: in resistance vs. control |

| Channer et al. 199632 | 126 patients recovering from MIs | 1 hour; 2× week for 3 weeks, then weekly for 5 weeks | 8% completed the 8-week nonexercise; TCC: 82% completed TCC; 73% completed aerobic exercise group | Instructions to home-based practice not reported and the authors were unable to be contacted | TCC group demonstrated decreases in diastolic BP and heart rate; decreases in systolic BP were seen in both TCC and AE groups |

| Galantino et al. 200533 | 38 HIV patients | 1 hour; 2× per week for 8 weeks | When the authors were contacted, they reported an 80% adherence rate in the TCC arm | From our inquiry: “participants completed exercise logs; however, [these] data were not reported in publication” | Improved physical functioning and improved quality of life in both TCC and exercise groups |

| Chan et al. 200412 | 132 postmenopausal women | 45 minutes, 5× week for 12 months | Average attendance rate for the TCC exercise group was 4.2 ± 0.9 days per week. The dropout rate was 19.4% in the TCC group (13/67 subjects) and 16.9% in the control group (11/65 subjects) | Home-based practice was not addressed in the publication and the authors were not reachable | Bone-marrow density loss shown to be slower in TCC group (both groups still showed bone loss over the year) |

| Tsai et al. 200334 | 76 subjects with normal or stage I hypertension | 3× per wk for 50 minutes for 12 weeks | Not reported | No mention of outside practice or instructions for outside practice is made (outside of instructing them to not change their dietary intake) | TCC group: showed significant decreases in systolic blood pressure; total serum cholesterol decreased; HDL increased; both stait and trait anxiety decreased |

Studies highlighted in gray instructed participants to not change their physical activity outside of the intervention; all others either encouraged TCC practice outside of the scheduled class setting or instructions were unreported. Direct quotes from publications are delineated by quotations, and information gathered from correspondence (T.S. via e-mail) is marked accordingly.

These publications were noted (through author correspondence) to be reported across 2 separate publications, both listed in Table 1.

TCC, t'ai chi chuan; SF-36, Short Form–36 Health Survey; QoL, quality of life; BP, blood pressure; ED, education; WE, wellness education; VR, vestibular rehabilitation; AE, aerobic exercise; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

All 19 of the included publications reported on the length and duration of the intended TCC class schedule in the original report. In the intent-to-treat analyses, the total number of minutes of intended class during the intervention ranged from 540 minutes (16 hour-long sessions across 12 weeks)11 to 10,800 minutes (45-minute sessions, 5 times per week for 12 months).12 The median of t'ai chi practice was 2877 minutes across the 19 interventions (see Fig. 1).

As can be seen from Table 1, TCC has been studied in a wide range of patient populations and has been investigated thoroughly in elderly populations (7 out of the 19 studies selected). The attendance rates and instructions regarding home-based practice are highlighted and summarized below, in addition to being presented in Table 1.

Attendance to scheduled interventions

Attendance rates were reported in 14 out of the 19 publications, and authors reported attendance rates for 2 additional studies (out of the 19 selected) via e-mail. This correspondence is noted under the “Attendance Rates” column in Table 1. The average across these studies was 79% and 74% attendance to TCC classes and comparison exercise groups, respectively. When attendance was taken into account (for these 14 studies), the median amount of TCC practice received by participants was 2069 minutes.

Instruction given regarding outside TCC practice

In addition to attendance reporting, we examined publications for the instructions given to participants by the TCC instructor regarding TCC practice outside of the scheduled class meetings. Ten (10) of the studies selected for review encouraged participants to practice TCC outside of class.7,9,11,13–19 For example, 2 publications13 recommended practicing daily TCC, outside of class instruction, to participants. Another study specified home practice at least 3 times a week outside of supervised instruction. Within this group (of 10 studies) of selected studies, we were unable to find details regarding materials (e.g., training videotapes) given to participants for outside practice or details of instruction beyond the recommended amount of practice. Only 1 of the 10 studies that encouraged outside practice5 reported the amount of TCC practiced at home by participants (which increased over the intervention period). The remaining 9 studies did not discuss the amount of home TCC practice. From these 10 studies, 9 authors were successfully contacted via e-mail (T.S., personal correspondence); however, the authors were unable to provide further data on home practice adherence or high-practice versus low-practice subgroup analyses.

Three of the studies5,8,10 included in this review discouraged TCC practice outside of the scheduled class environment, instructing participants to not change outside physical activity. This group of studies is highlighted in Table 1. These study investigators confirmed (T.S., personal correspondence via e-mail) the compliance of study participants with these instructions via participants' self-report. If participants did in fact practice TCC outside of the structured class environment, the investigators were unable to comment on the amount or number of participants' home-based practice.

Both the study with the shortest11 as well as the study with the longest12 duration of TCC practice (540 versus 10,800 minutes, respectively) demonstrated benefit from TCC intervention compared to their respective control groups. When osteoarthritis patients practiced 540 minutes of TCC over 12 weeks, the TCC group experienced less pain and stiffness and reported fewer difficulties in physical functioning compared to controls. Postmenopausal women performing TCC for 10,800 minutes over 12 months for almost 20 times more than in the previously quoted study demonstrated slower bone mineral density loss (it should be noted that both groups still showed some bone loss over the year). Thus, TCC practice may show an effect based on a wide range of practice duration or “TCC dose.”

Discussion

This review and author survey shows that the duration or “dose” of formal TCC training administered across these selected studies varies greatly. In addition, instructions regarding home TCC practice vary between studies. In those cases where home practice is encouraged, there is little monitoring of the adherence to the recommendation in terms of time spent. As a result of this variability in study design and monitoring of the study intervention, the dose of TCC received by participants in published TCC studies is highly variable. Nevertheless, this mind–body practice has received increasing attention as an exercise intervention for a number of health conditions (for review see Li et al.20), with a recent, widely popularized publication suggesting possible immunostimulatory effects from t'ai chi practice.5

TCC may improve the risk of falling in elderly persons, balance for vestibulopathy patients, and cardiovascular outcomes, physical functioning, and pain in patients with chronic conditions.6 Based on the current review, it is clear that although the majority of interventions teach participants for an average of 2877 minutes over the course of the intervention (typically 1-hour-long sessions 3 times per week), there is no consensus on how much TCC practice would be necessary to see a benefit in the various conditions studied.

It is not clear how investigators determine the dose of TCC to be included in their studies. Only one publication in this review5 cited the TCC program (40-minute TCC practice 3 times per week for 16 weeks). The other investigators did not comment on their rationale for selecting the length or intensity of their t'ai chi program. The Arthritis Foundation suggests practicing daily: “The practice can take as few as five minutes or can last as long as an hour per session.”21 However, we were unable to find any other recommendations or suggestions on what would constitute an effective practice. Although the data reported here did not find a consistent relationship between the dose of TCC and effects of intervention, further research should determine the optimal dose of TCC for various conditions.

One strategy for studying varying doses of TCC would be to test duration and intensities drawn from the exercise literature. Indeed, TCC is often characterized as an exercise intervention, with corresponding cardiovascular and respiratory benefit.22,23 Thus, TCC instruction may follow guidelines similar to other physical exercise programs, such as the surgeon general's recommendation of 30 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise 5 days per week.24 This amount of exercise has been shown to be effective for major depressive disorder, and although the investigators hypothesized a dose response, lower amounts of exercise were not significantly different for the control group.25 The investigation of dose optimization for exercise interventions may be an area for further study, which could in turn contribute to establishing an effective dose in aerobic CAM activities such as TCC.

A cursory review of other CAM mind–body investigations (possibly sharing meditative aspects of TCC) revealed a small amount of pilot data suggesting dose responses. For instance, Gross et al.26 demonstrated a significant dose–response relationship between hours of practice and reduction in anxiety and sleep symptom change (from baseline to 3-month follow-up) in a Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction Program. The intended “dose” was 225 minutes of mindfulness meditation per week (45 minutes per day at least 5 days per week for 8 weeks). Participants (N = 20) averaged 18.7 minutes per day across the 8 weeks, with adherence to home-based practice monitored through telephone calls and patient logs. Greater amounts of total practice (including time in class and at-home practice) produced significantly greater improvements in sleep quality and anxiety ratings. A similar dose response was noted in home yoga practice, which yielded greater hip function and gait strength.27 Participants attended 2 90-minute yoga classes per week for 8 weeks and were asked to complete at least 20 minutes of directed home practice on alternate days, completing daily logs of home-based practice. Participants who practiced at home an average of 30 minutes or more per day (n = 10) experienced significant changes in both hip extension and pelvic tilt than those who practiced less than 30 minutes a day on average. In both of these programs, home-based practice is the tenet of the intervention, and making concerted efforts to monitor this practice time is essential. Larger trials with similar study designs that prove effective and well-adhered to could guide future methodologies for investigating dose optimization for TCC.

One limitation to the current inquiry into dose optimization is that this study does not take quality of TCC practice into account. All of the studies reviewed here utilized the skills of a t'ai chi master; however, what dictates a master is not clarified by any of the investigators. Furthermore, there is almost no mention, outside of anecdotal notes of participants' satisfaction, of how well participants performed within the structured intervention. Some participants may have maintained a high level of focus throughout the class period, which is one tenet of TCC practice. Other participants could have been completely unfocused during their time in class. Although there is no ranking system of TCC performance that we were able to identify, the issue of quality may precede the current investigation into dose optimization and should be addressed by future investigators.

Reporting at the level of detail that is highlighted in this paper may not be a priority for the majority of behavioral intervention research despite recent attempts to include such recommendations in the CONSORT guidelines of clinical trial reporting.28 CAM, such as TCC, should be studied applying rigorous research methodology. Dose optimization for CAM behavioral interventions requires close monitoring and determination of how much of an intervention was actually received by participants, resulting in increased rigor of CAM research data. Well-designed and -executed clinical research in CAM is needed to inform the public about safety and efficacy of CAM practices that are becoming increasingly popular.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mary Ryan for her help conducting the original literature search. We would also like to thank Dr. Shan Wong for his thoughtful review of this manuscript as well as Dawn Wallerstedt, C.R.N.P., and Phil Sannes for their unrelenting support. Special thanks to Kathryn Ross for her help with table and figure formatting.

References

- 1.Eisenberg DM. Davis RB. Ettner SL, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990–1997: Results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280:1569–1575. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes PM P-GE. McFann K. Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. CDC advance data from vital and health statistics. 2004. number 343. [PubMed]

- 3.National Center for Complementary Alternative Medicine. Expanding horizons of health care: Strategic plan. 2001–2005. http://nccam.nih.gov/about/plans/fiveyear/index.htm http://nccam.nih.gov/about/plans/fiveyear/index.htm

- 4.Bent S. Kane C. Shinohara K, et al. Saw palmetto for benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:557–566. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Irwin MR. Olmstead R. Oxman MN. Augmenting immune responses to varicella zoster virus in older adults: A randomized, controlled trial of tai chi. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:511–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mansky P. Sannes T. Wallerstedt D, et al. Tai chi chuan: Mind-body practice or exercise intervention? Studying the benefit for cancer survivors. Integr Cancer Ther. 2006;5:192–201. doi: 10.1177/1534735406291590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li F. Harmer P. Fisher KJ. McAuley E. Tai Chi: Improving functional balance and predicting subsequent falls in older persons. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:2046–2052. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000147590.54632.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mustian KM. Katula JA. Gill DL. Roscoe JA. Lang D. Murphy K. Tai Chi Chuan, health-related quality of life and self-esteem: A randomized trial with breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2004;12:871–876. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0682-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li F. Harmer P. Fisher KJ, et al. Tai Chi and fall reductions in older adults: A randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:187–194. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mustian KM. Katula JA. Zhao H. A pilot study to assess the influence of tai chi chuan on functional capacity among breast cancer survivors. J Support Oncol. 2006;4:139–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song R. Lee EO. Lam P. Bae SC. Effects of tai chi exercise on pain, balance, muscle strength, and perceived difficulties in physical functioning in older women with osteoarthritis: A randomized clinical trial. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:2039–2044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan K. Qin L. Lau M, et al. A randomized, prospective study of the effects of Tai Chi Chun exercise on bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:717–722. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.08.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolf SL. Barnhart HX. Kutner NG. McNeely E. Coogler C. Xu T. Reducing frailty and falls in older persons: An investigation of Tai Chi and computerized balance training. Atlanta FICSIT Group. Frailty and Injuries: Cooperative Studies of Intervention Techniques. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:489–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeh GY. Wood MJ. Lorell BH, et al. Effects of tai chi mind-body movement therapy on functional status and exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Med. 2004;117:541–548. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolf SL. Barnhart HX. Kutner NG. McNeely E. Coogler C. Xu T. Selected as the best paper in the 1990s: Reducing frailty and falls in older persons. An investigation of tai chi and computerized balance training. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1794–1803. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li F. Fisher KJ. Harmer P. Irbe D. Tearse RG. Weimer C. Tai chi and self-rated quality of sleep and daytime sleepiness in older adults: A randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:892–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGibbon CA. Krebs DE. Parker SW. Scarborough DM. Wayne PM. Wolf SL. Tai chi and vestibular rehabilitation improve vestibulopathic gait via different neuromuscular mechanisms: Preliminary report. BMC Neurol. 2005;5:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-5-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGibbon CA. Krebs DE. Wolf SL. Wayne PM. Scarborough DM. Parker SW. Tai chi and vestibular rehabilitation effects on gaze and whole-body stability. J Vestib Res. 2004;14:467–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas GN. Hong AW. Tomlinson B, et al. Effects of tai chi and resistance training on cardiovascular risk factors in elderly Chinese subjects: A 12-month longitudinal, randomized, controlled intervention study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2005;63:663–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li JX. Hong Y. Chan KM. Tai chi: Physiological characteristics and beneficial effects on health. Br J Sports Med. 2001;35:148–156. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.35.3.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hortsman J. The Arthritis Foundation. www.arthritis.org/resources/arthritistoday/2000_archives/2000_07_08_taichi.asp. [Jun 6;2006 ]. www.arthritis.org/resources/arthritistoday/2000_archives/2000_07_08_taichi.asp

- 22.Lai JS. Wong MK. Lan C. Chong CK. Lien IN. Cardiorespiratory responses of Tai Chi Chuan practitioners and sedentary subjects during cycle ergometry. J Formos Med Assoc. 1993;92:894–899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhuo D. Shephard RJ. Plyley MJ. Davis GM. Cardiorespiratory and metabolic responses during Tai Chi Chuan exercise. Can J Appl Sport Sci. 1984;9:7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Department of Health Human Services Centers for Disease Control Prevention NC Promotion; fCDPaH. US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. 1996.

- 25.Dunn AL. Marcus BH. Kampert JB. Garcia ME. Kohl HW., 3rd Blair SN. Comparison of lifestyle and structured interventions to increase physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness: A randomized trial. JAMA. 1999;281:327–334. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.4.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gross CR. Kreitzer MJ. Russas V. Treesak C. Frazier PA. Hertz MI. Mindfulness meditation to reduce symptoms after organ transplant: A pilot study. Adv Mind Body Med. 2004;20:20–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DiBenedetto M. Innes KE. Taylor AG, et al. Effect of a gentle Iyengar yoga program on gait in the elderly: An exploratory study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:1830–1837. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davidson KW. Goldstein M. Kaplan RM, et al. Evidence-based behavioral medicine: What is it and how do we achieve it? Ann Behav Med. 2003;26:161–171. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2603_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dunn AL. Trivedi MH. Kampert JB. Clark CG. Chambliss HO. Exercise treatment for depression: Efficacy and dose response. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Irwin MR. Pike JL. Cole JC. Oxman MN. Effects of a behavioral intervention, Tai Chi Chih, on varicella-zoster virus specific immunity and health functioning in older adults. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:824–830. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000088591.86103.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang C. Roubenoff R. Lau J, et al. Effect of tai chi in adults with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:685–687. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Channer KS. Barrow D. Barrow R. Osborne M. Ives G. Changes in haemodynamic parameters following Tai Chi Chuan and aerobic exercise in patients recovering from acute myocardial infarction. Postgrad Med J. 1996;72:349–351. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.72.848.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galantino ML. Shepard K. Krafft L, et al. The effect of group aerobic exercise and t'ai chi on functional outcomes and quality of life for persons living with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:1085–1092. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsai JC. Wang WH. Chan P, et al. The beneficial effects of Tai Chi Chuan on blood pressure and lipid profile and anxiety status in a randomized controlled trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2003;9:747–754. doi: 10.1089/107555303322524599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]