Abstract

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) is a pivotal glycolytic enzyme, and a signaling molecule which acts at the interface between stress factors and the cellular apoptotic machinery. Earlier, we found that knockdown of GAPDH in human carcinoma cell lines resulted in cell proliferation arrest and chemoresistance to S phase-specific cytotoxic agents. To elucidate the mechanism by which GAPDH depletion arrests cell proliferation, we examined the effect of GAPDH knockdown on human carcinoma cells A549. Our results show that GAPDH-depleted cells establish senescence phenotype, as revealed by proliferation arrest, changes in morphology, SA-β-galactosidase staining, and more than 2-fold up-regulation of senescence-associated genes DEC1 and GLB1. Accelerated senescence following GAPDH depletion results from compromised glycolysis and energy crisis leading to the sustained AMPK activation via phosphorylation of α subunit at Thr172. Our findings demonstrate that GAPDH depletion switches human tumor cells to senescent phenotype via AMPK network, in the absence of DNA damage. Rescue experiments using metabolic and genetic models confirmed that GAPDH has important regulatory functions linking the energy metabolism and the cell cycle networks. Induction of senescence in LKB1-deficient non-small cell lung cancer cells via GAPDH depletion suggests a novel strategy to control tumor cell proliferation.

Keywords: senescence, AMPK, GAPDH, glycolysis, metabolic stress, lung cancer

1. Introduction

Induction of senescence-like phenotype is considered a promising strategy to control tumor cell proliferation; a better understanding of mechanisms leading to induction of senescence will open avenues toward novel therapeutic modalities [1]. Cellular senescence is a complex process driven by multiple senescence-associated factors within mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade, retinoblastoma, and p53 tumor suppressor pathways. While replicative senescence occurs in normal cells after a certain number of cell divisions, accelerated cellular senescence is a program executed in response to various types of stress, e.g., oncogene activation, genotoxic or metabolic stress [1; 2]. Both types of senescence are characterized by DNA synthesis arrest, changes in morphology (enlarged, flattened shape of the cells), and accumulation of biomarkers such as senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal), p16/INK4a, and DEC1.

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) is recognized as an intriguing example of moonlighting proteins, which performs multiple functions within seemingly unrelated pathways [3]. Recent studies revealed the role of GAPDH as a signaling molecule which acts at the interface between stress factors and the cellular apoptotic machinery [4–6]. Earlier we reported that knockdown of GAPDH resulted in accumulation of p53, and p21 leading to cell cycle arrest, and chemoresistance to S phase-specific cytotoxic agents [7].

In the present work, we demonstrate that GAPDH-depleted cells establish senescence phenotype characterized by cell proliferation arrest, altered cell morphology, and induction of senescence biomarkers. Our study revealed that senescence in GAPDH-depleted non-small cell lung cancer cells is induced by sustained activation of AMPK followed by p53 stabilization. Our findings indicate that cell proliferation in LKB1-deficient human carcinoma cell line A549 could be switched over to senescence phenotype by GAPDH depletion, and that GAPDH plays a critical role linking the energy metabolism and the cell cycle networks, thus deepening its significance as a novel target to control tumor cell proliferation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell cultures and drug treatment

Human lung carcinoma A549 cell line (LKB1-deficient, p16-deficient, p53-proficient) was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). A549 cells were maintained in Ham’s F12K medium containing 7 mM glucose with 10% FBS at a confluency of 40–80%, at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and cultivated for less than 6 months. For AMPK inhibition, cells were treated with 200 nM of Compound C (VWR, NJ).

2.2. Cell growth and viability

were measured by flow cytometry with Guava Personal Cell Analyzer (PCA, Guava Technologies, Hayward, CA) using ViaCount reagent (Millipore, Hayward, CA), as described earlier [8]. For cell proliferation assay, cells were transfected with 10 nM siGAPDH (GAPDH-depleted cells) or scrambled siRNA (control cells), incubated for 48 hr, and re-plated in 6-well plates at density 10,000 cells/cm2. Cells were collected every 24 hr by trypsinization, and counted.

2.3. RNA interference with short duplex RNA

RNAi experiments were performed using predesigned Stealth RNA (GAPDH Validated Stealth RNAi DuoPak duplexes 1 and 2) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Transient transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent, as described earlier [7] or electroporation technique using the Neon™ Transfection System by manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The final siGAPDH concentration was 1–50 nM. Scrambled Negative Stealth RNAi control (Invitrogen, CA) was used as negative control in all siRNA experiments. For rescue experiments, a construct pGAPDH containing GAPDH ORF driven by CMV promoter was prepared and verified by sequencing.

2.4. Telomere length measurement by quantitative PCR

The relative telomere lengths (T/S ratios) were measured in DNA extracted from A549 cells using quantitative Real-Time PCR method as described by Cawthon [9]. All qRT-PCR experiments were performed in triplicate with ABI 7300 instrument (Applied Biosystems, CA). The DNA content was normalized against the signal from albumin gene-specific primers.

2.5. RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cultured A549 cells (about 2×106 cells per experiment, 3 replicates) using Ribopure TM kit (Ambion, TX) and quantified by fluorescent method with Quant-iT RNA assay kit (Invitrogen, CA). The relative quantification of GLB1 mRNA was performed by SYBR Green assay (Fermentas, MD), and DEC1 mRNA with TaqMan assay (Applied Biosystems, CA). The level of specific mRNA was normalized against β-actin mRNA (for GLB1 mRNA), or 18S rRNA (for DEC1 mRNA). Data were collected from 3 independent experiments in 3 replicates for each sample.

2.6. Enzymatic assays

ATP level was estimated by the Adenosine 5’-triphosphate (ATP) bioluminescent somatic cell assay kit (Sigma, St. Louis, Missouri) using 6000–10,000 cells per assay. GAPDH enzymatic activity was estimated with KDalert GAPDH assay, per manufacturer's protocol (Ambion, Austin, TX).

2.7. Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as described earlier [8]. Membranes were developed using rabbit monoclonal anti-phosphoAMPKα antibody at dilution of 1:1000 (Cell Signaling Technologies, MA), monoclonal anti-GAPDH antibody at 1:10,000 (Millipore, Billerica, MA), mouse monoclonal anti-p53 at 1:500 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin Ab at 1:10,000 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, CA), rabbit anti-Ser15-phosphorylated p53 Ab at 1:1000, rabbit anti-γH2AX (H2AX phosphorylated at Ser-139) polyclonal Ab at 1:500 (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA), and rabbit anti-phospho-S6 ribosomal protein Ab at 1:2000 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). Rabbit anti-AMPK (non-phosphorylated) antibody was a generous gift from Dr. Birnbaum (University of Pennsylvania, PA). β-actin was used as a loading control. Bands were quantified using Odyssey Infrared Imaging system version 3.0 (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) with fluorescence detection at 700 nm and 800 nm.

2.8. Senescence-Associated β-galactosidase assay

Cellular senescence was detected by Senescence Cells Histochemical Staining kit (Sigma, St. Louis, Missouri). Cells were seeded in a 6-well plate at density 200,000 cells per well. The proportion of blue-stained cells was determined by light microscopy, and results were presented as the mean percentage of stained cells from at least five fields for each experiment.

2.9. Neutral Comet Assay

DNA damage was assessed using neutral Comet assay (pH 8.3; 1V/cm; 20 min) using the CometAssay kit (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD) according to manufacturer's instructions. The Olive Tail Moment was determined for 50 cell images in each sample using CometScore freeware (TriTek, Sumerduck, VA).

2.10. Immunofluorescent Microscopy

Cells were grown on BD BioCoat poly-L-lysine pre-coated glass coverslips (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in 12-well plates at a density of 50,000 cells/well, and fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 15 min. Cells were then washed in ice-cold methanol, blocked in 5% normal rabbit serum, and labeled with anti–γ-H2AX antibody (phosphorylated histone H2A.X rabbit monoclonal antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488; Cell Signaling Technology). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI and mounted with Vectashield hard set mounting medium (Vector Laboratories). Fluorescence images were recorded with a Nikon Eclipse 50i fluorescent microscope and analyzed by ImageJ1.37v software (NIH). All experiments were repeated at least four times.

2.11. Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were carried out using Student's t test with Statistica 7 software program (StatSoft, OK), and non-linear regression analysis with GraphPad Prizm 4.0 software (GraphPad software, CA). p value<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data are presented as the mean ± SE.

3. Results

3.1. Accelerated senescence phenotype in GAPDH-depleted lung carcinoma A549 cells

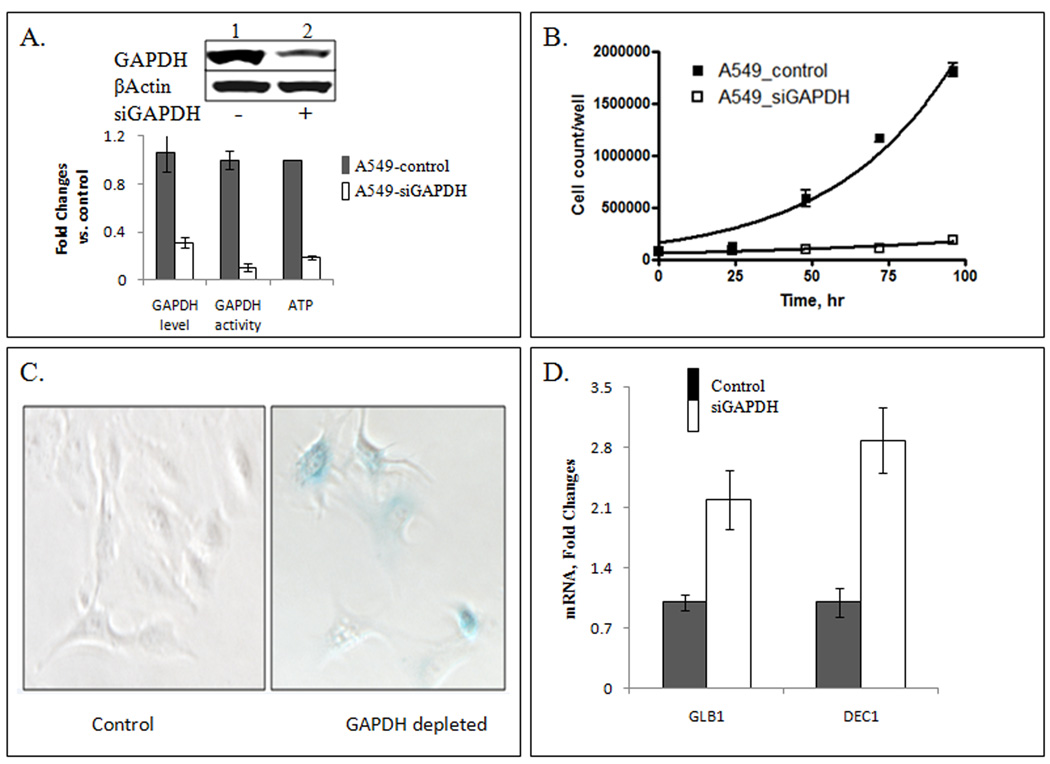

Human lung carcinoma cells A549 were transiently transfected with two different siRNA targeted against GAPDH mRNA (siGAPDH). Pre-designed Stealth RNA (GAPDH Validated Stealth RNAi DuoPak) duplexes 1 and 2 used in RNA interference experiments did not exert off-target effects, as described earlier [7]. The residual level of mRNA in siGAPDH-treated A549 cells was about 5–10% of control cells treated with scrambled siRNA. A consistent decrease in GAPDH protein level, enzymatic activity, and ATP level was observed in A549 cells (Fig. 1A). The level of GAPDH was not restored for at least 7 days after transfection [7]. Knockdown of GAPDH by siGAPDH caused cell proliferation arrest, in contrast to control A549 cells transfected with scrambled siRNA (Fig. 1B). Cells treated with siGAPDH manifested proliferation arrest, revealed enlarged morphology, and distinct blue staining characteristic for SA-β-galactosidase activation (42±15% stained cells vs. 2±2% in control cells) (Figure 1C). Simultaneously, we observed accumulation of senescence markers, GLB1 and DEC1 mRNAs (Figure 1D). Taken together with cell proliferation arrest, these markers delineate the senescent phenotype of GAPDH-depleted cells. Treatment with 2DG also resulted in cell proliferation arrest. Incubation with 2DG did not change appearance of the cells compared to control (untreated) cells. Low SA-β-galactosidase activity was associated with 2DG-treated cells (5±3% stained cells). We did not detect manifestation of senescence markers GLB1 and DEC1 mRNA after 2DG treatment (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Accelerated senescence phenotype in GAPDH-depleted lung carcinoma A549 cells. Panel A: Western blot analysis of cell lysate after siGAPDH treatment for 72 hr demonstrated 70% reduced GAPDH level relative to control (cells treated with scrambled siRNA). Lower chart, relative levels of GAPDH protein, GAPDH activity and ATP in control cells (gray bars), and in cells incubated for 72 hr after transfection with 10 nM siGAPDH (open bars). All data were collected from at least three independent experiments and presented as the mean ± SE. Panel B: GAPDH knockdown induces cell proliferation arrest. Cells were transfected with 10 nM siGAPDH or scrambled siRNA (control), collected every 24 hr by trypsinization, and counted as described in Materials and Methods. (■), control cells; (□), GAPDH knockdown cells (treated with siGAPDH RNA). Where not seen, error bars are smaller than symbols. Panel C: Senescence-Associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) activity in control and GAPDH depleted cells. SA-β-gal staining was evaluated microscopically after cell fixation and staining with X-gal at pH 6.0 overnight. Blue staining was prominent in cells incubated for 72 hours after siGAPDH transfection (right image), but not in control cells (left image). Panel D: Expression of senescence-related biomarkers GLKB1 and DEC1 mRNA following GAPDH depletion. Two days after transfection, the cells were harvested, total RNA was extracted, and the relative levels of GLB1 and DEC1 mRNA were estimated using quantitative RT-PCR. The results were normalized using β-actin mRNA (for GLB1) or 18S rRNA ( for DEC1) as endogenous standards. The gray bars, control cells; the open bars, GAPDH knockdown cells.

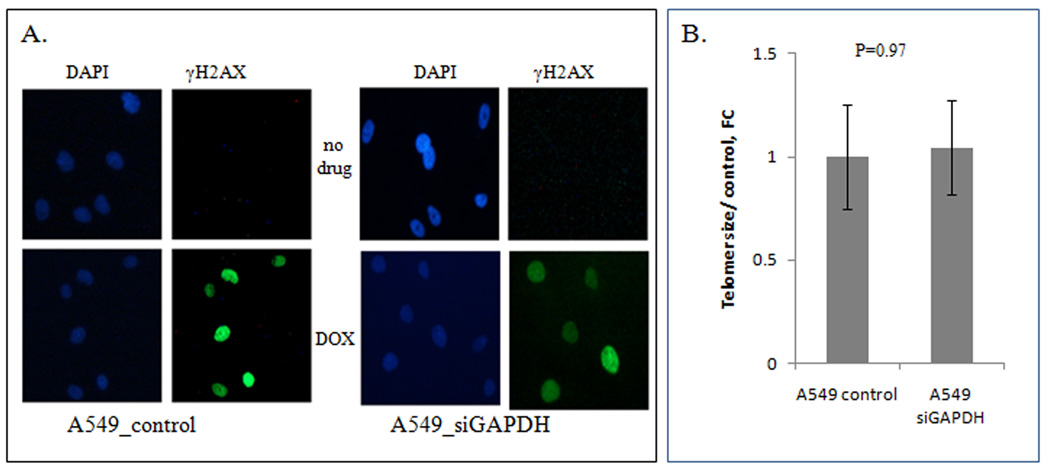

3.2. Energy crisis in A549 cells induces cellular senescence in the absence of telomere shortening or DNA damage

After treatment with siGAPDH, we did not detect γH2AX accumulation indicating the absence of DNA damage response (Fig. 2A). No accumulation of double strand breaks was revealed by Comet assay in A549 cells after GAPDH depletion. The Olive Tail moments calculated for control cells did not differ statistically from those for siGAPDH-treated cells (p=0.76) (Supplementary Fig. 1). Estimation of the relative average telomere length using quantitative RT-PCR method did not reveal shortening of telomeres in GAPDH-depleted cells, compared with control cells treated with scrambled siRNA (p=0.97) (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

GAPDH depletion does not induce DNA damage or telomere shortening in A549 cells. Panel A: Immunohistochemical analysis of control cells (left images) or siGAPDH-treated cells (right images) for the presence of γH2AX foci. After transfection, cells were incubated for 2 days, and immunostained with anti-γH2AX Ab as described in Materials and Methods. The DSB marker γH2AX did not reveal DNA damage after GAPDH knockdown. As a positive control for γH2AX activation, cells treated with DOX were immunostained in the same experiment. Panel B: The length of telomeres was not decreased in GAPDH knockdown cells (p=0.97). Genomic DNA was extracted from control cells, or 10 nM siGAPDH-depleted cells, and the number of telomeric repeats was estimated using quantitative PCR using Cawthon primers [9]. The results have been obtained from three independent experiments, with four replicates in each experiment, and shown as the mean ± SE.

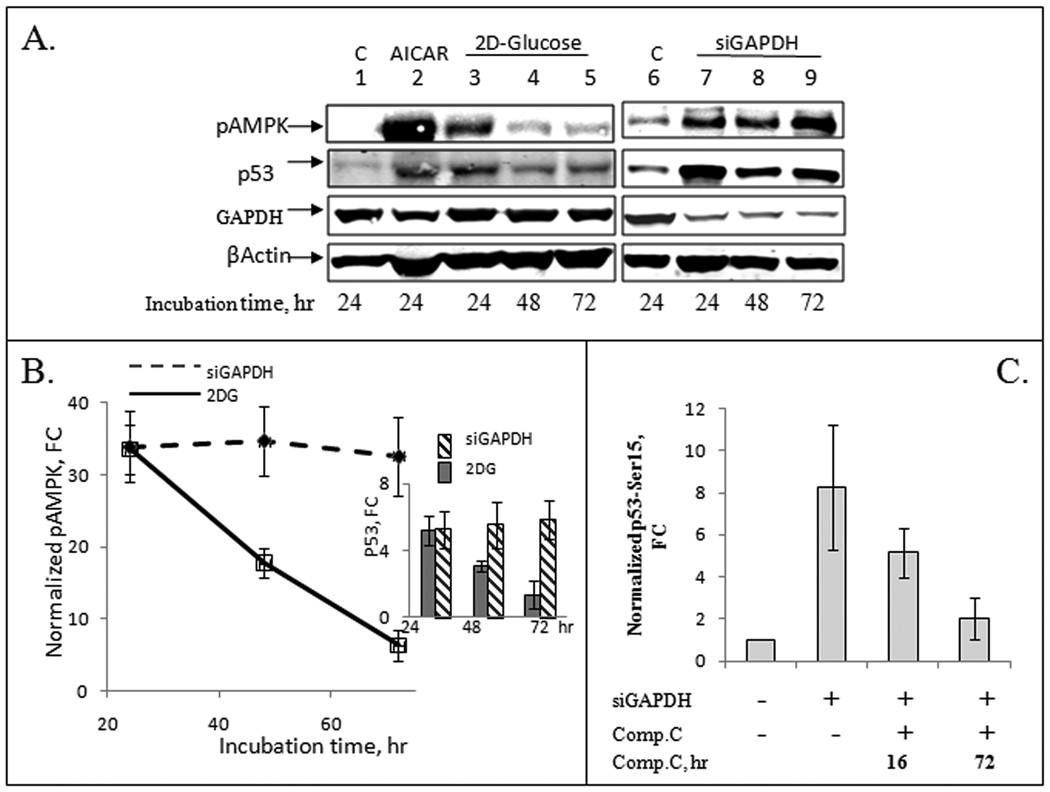

3.3. GAPDH depletion causes sustained phosphorylation of AMPK and stabilization of p53 in human lung cancer cells A549

Treatment of A549 cells with 2 mM AICAR for 2 hours, or 50 mM 2DG for 24 hr resulted in AMPK activation, as revealed by Western analysis with Thr172-specific anti-phosphoAMPKα antibody (Fig. 3A). Following inhibition of glycolysis via GAPDH depletion, the decrease of ATP level resulted in AMPK phosphorylation, and p53 stabilization (Fig. 3B). In line with these findings, we detected accumulation of p53 phosphorylated at Ser15 in GAPDH knockdown cells (Fig. 3C). Activation of AMPK in GAPDH-depleted cells persisted for at least 72 hrs, in parallel to the stabilization of p53 during this period. On the other hand, AMPK activation caused by 2DG treatment was short-lived: the level of phosphorylated AMPK dropped 5–7-fold after 72 hr incubation (Fig. 3A, B). Correspondingly, p53 level dropped during this time (see insert in Fig. 3B). Incubation of GAPDH-depleted cells with Compound C (an AMPK inhibitor) decreased phosphorylation of Ser15 in p53 (Fig. 3C). We also assessed mTOR activation by testing the phosphorylation of its biomarker ribosomal protein S6 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Neither siGAPDH, nor 2DG treatment inhibited accumulation of phosphorylated S6 in the presence of fetal bovine serum and glucose, and pS6 remained at the level comparable with control proliferating A549 cells.

Figure 3.

GAPDH depletion causes sustained phosphorylation of AMPK and stabilization of p53 in human lung cancer A549 cells. Panel A: Western blot analysis demonstrated accumulation of phospho-AMPK and p53 after treatment with 50 mM 2DG for 6 hr followed by incubation for 24–72 hr in complete F12K medium containing 7 mM glucose (lanes 3–5), or following transfection with siGAPDH (lanes 7–9). Cells treated with AMPK inducer AICAR for 2 hr (lane 2) were used as a positive control. No treatment control, lanes 1 and 6. Panel B: The relative levels of Thr172-phosphoAMPK (active kinase) were estimated in 2DG and siGAPDH-treated cells by image analysis of membranes shown in Panel A after staining with infra-red dye labeled antibodies. The insert shows the relative change in p53 level in the same samples. FC, fold change. Panel C: Relative levels of p53 phosphorylation at Ser15 in the presence of AMPK-specific protein kinase inhibitor Compound C. Incubation of GAPDH-depleted cells with 200 nM Compound C abrogated phosphorylation of p53 at Ser15, as revealed by Western blot analysis with anti-Ser15-p53 antibody. p53 phosphorylation was estimated by image analysis of membranes after staining with infra-red dye-labeled antibodies.

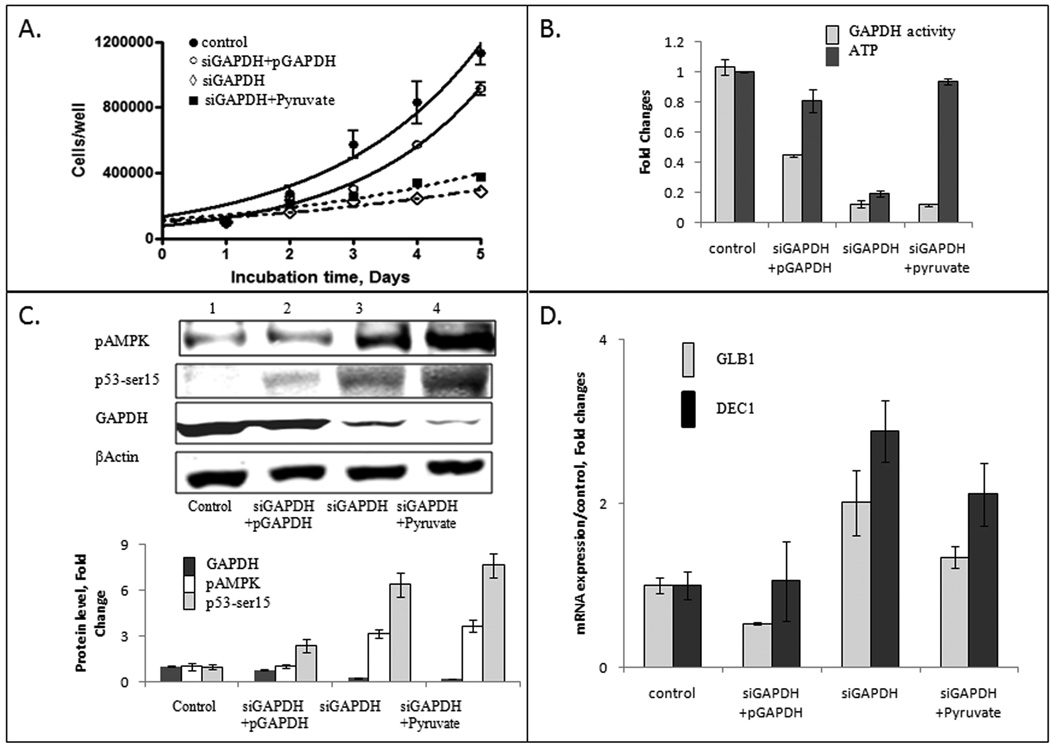

3.4. Senescence phenotype is reversed by overexpression of GAPDH but not metabolic compensation of glycolysis

Genetic rescue of GAPDH-depleted cells by overexpression of wild type GAPDH restored cell proliferation as demonstrated by cell growth curve (Fig. 4A). Overexpression also restored GAPDH protein, enzymatic activity, and ATP levels in siGAPDH-treated A549 cells (Fig. 4B). Phosphorylation of Ser15 in p53 was abrogated with GAPDH-expressing plasmid pGAPDH (Fig. 4C). To compensate for the requirements for glycolytic functions of GAPDH, siGAPDH-transfected A549 cells were incubated in F12K medium supplemented with 10 mM pyruvate. Addition of 10 mM pyruvate compensated the shortage of ATP, in the absence of GAPDH protein or activity (Fig. 4B). Sodium pyruvate did not restore proliferation of GAPDH-depleted cells (Fig. 4A). Control experiments ruled out inhibition of cell growth by 10 mM pyruvate, or pGAPDH transfection (Supplementary Fig. 3). Importantly, the presence of pyruvate did not abrogate p53 phosphorylation (Fig. 4C). Overexpression of GAPDH restored the low level of senescence biomarkers GLB1 and DEC1 mRNA, while expression of GLB1 and DEC1 genes in siGAPDH-depleted cells supplemented with 10 mM pyruvate remained high (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

Energy crisis rescue with metabolic (by adding downstream ATP-generating metabolite pyruvate) and genetic (by ectopic overexpression of GAPDH) compensation of ATP deficit. Panel A: Cell growth curves of cells treated under different conditions: ●- control; ☼-siGAPDH+pGAPDH; ◊-siGAPDH; ■siGAPDH+Pyruvate. Following transfection with siGAPDH, cells were re-plated and treated with 10 mM pyruvate. Alternatively, cells were transfected with siGAPDH duplex, along with GAPDH-expressing construct driven by CMV promoter. Cells were collected by trypsinization every 24 hr and counted. The chart shows the results of three independent experiments. Where not seen, error bars are smaller than symbols. Panel B: Intracellular GAPDH activity (open bars) and ATP level (gray bars) were measured after 72 hr incubation. Enzymatic activity of GAPDH was estimated with KDalert GAPDH assay and ATP level was estimated using the ATP bioluminescent somatic cell assay. Bioluminescence was measured in triplicate, and quantified against the standard curve. Panel C: GAPDH overexpression (black bars) but not pyruvate supplement prevented activation of AMPK (open bars) and phosphorylation of p53 at Ser15 (gray bars). Relative levels of phosphoAMPK and phospho-Ser15-p53 were estimated using Western blot analysis with two-color fluorescence detection. β-actin was used as loading control and for normalization. Panel D: Quantitative analysis of senescence biomarkers DEC1 and GLB1 mRNA after metabolic or genetic compensation of ATP deficit. Total RNA was extracted from the cells, and the relative levels of GLB1 (gray bars) and DEC1 (black bars) mRNA were estimated using quantitative Real-time PCR analysis. β-actin mRNA and 18S rRNA were used as endogenous controls. The chart shows the results from two independent experiments performed in triplicate.

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we report that human non-small lung cancer A549 cells acquire senescence phenotype after depletion of GAPDH, a pivotal enzyme in glycolytic pathway. Cellular senescence has critical significance for neoplastic transformation providing a barrier for pre-malignant cells. Induction of senescence in tumor cells was observed in response to restoration of tumor suppression, oncogene inactivation, and chemotherapeutic intervention, and therefore is a viable strategy for anticancer therapy [1; 2]. Activation of the senescence phenotype is induced by different types of stress including telomere uncapping, DNA damage, oncogene activity, lack of nutrients and growth factors, and improper cell contacts [10].

Beyond its role in the glycolytic pathway, GAPDH is a component of cellular stress response [3; 4]. The recent findings link GAPDH to targeted nitrosylation of nuclear proteins as a general mechanism in cellular signal transduction [11]. Earlier we demonstrated that p53-proficient A549 cells responded to GAPDH depletion by cell cycle arrest, while p53-deficient NCI-H358 cells continued proliferating [7]. In the present study, we found that inhibition of the glycolytic pathway via GAPDH depletion resulted in reduction of ATP level, sustained activation of AMPK, and accumulation of p53. Because sustained activation of AMPK in murine cells has been shown to induce accelerated p53-dependent cellular senescence [12], we hypothesized that GAPDH depletion may induce senescence phenotype. To test this hypothesis, we assayed the senescence biomarkers in GAPDH-depleted human lung cancer A549 cells. Indeed, the siGAPDH-depleted cells manifested enlarged morphology, induction of SA-β-galactosidase activity, accumulation of p53 (Figs. 1, and 3), and accumulation of senescence biomarkers DEC1 and GLB1 mRNA (Fig. 1D). Expression of DEC1 gene mediates p53-dependent premature senescence, and GLB1 up-regulation accompanies premature senescence though is not necessary for establishing the senescence phenotype [13–15].

Upon activation, enzymatically active AMPK catalyzes phosphorylation of p53 at Ser 15 resulting in its stabilization, accumulation, and induction of p53 transcriptional activity [12;16]. After GAPDH depletion, AMPK activation was followed by phosphorylation and stabilization of p53 (Fig. 3A, B). Incubation of GAPDH-depleted cells with Compound C, which is a selective inhibitor of AMPK protein kinase activity, abrogated accumulation of Ser15-phosphorylated p53 (Fig. 3D). Importantly, in our experimental settings siGAPDH treatment had a prolonged AMPK-activating effect which lasted at least 7 days [7]. Therefore, the transfected cells experienced an extended period of energy stress. This was in contrast to 2DG treatment where AMPK activation drastically faded over a period of 72 hours, in parallel to decreasing level of p53 (Fig. 3A, C). We hypothesize that the differential effects of two ATP-depleting agents, 2DG and siGAPDH, are likely due to the prolonged AMPK activation after GAPDH depletion, in contrast to temporary AMPK activation after 2DG (Fig. 3C). Modulation of AMPK activity has been suggested for pharmacological management of cancer [17].

Because AMPK activation is accompanied by phosphorylation of α subunit at Thr172 [18], we monitored accumulation of Thr172-phosphorylated AMPK as a biomarker for active AMPK. Consistent with the lack of LKB1 in A549 cells, we observed delayed AMPK phosphorylation following treatment with AMPK inducers 2DG and AICAR. Accumulation of pAMPK was notable after 6 hr treatment with 50 mM 2DG, or 2 hr treatment with 2 mM AICAR (Fig.3A).

DNA damage is a strong pro-senescence stimulus. We assessed DNA damage using two analytical methods – electrophoretic mobility of DNA after in situ cell lysis (Comet assay), and accumulation of γH2AX which is a sensitive marker of DSB [19]. Neither method demonstrated DNA damage after GAPDH depletion. Another mechanism leading to senescence of cells is shortening of telomeres after multiple cycles of division. GAPDH knockdown was reported to decrease the length of telomeres in A549 cells [20]. In our experiments, we did not detect any shortening of telomeres in A549 GAPDH-depleted cells. The reason for these differential results is not clear at the moment but could be due to the nature of siRNA, or substantially lower siRNA concentrations in our experiments. Therefore, we ruled out genotoxic stress as an inducer of senescence after GAPDH knockdown (Fig. 2, and Supplementary Fig. 1).

We tested mTOR activation by assessing the level of S6 phosphorylation. S6 is a ribosomal protein and its phosphorylation parallels activity of mTOR, a regulator of protein biosynthesis and cell growth [21]. S6 phosphorylation was inhibited neither in GAPDH-depleted cells nor in 2DG-treated cells (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Senescence phenotype induced by GAPDH depletion was reversed by GAPDH over-expression, as evidenced by restored cell growth, decreased SA-β-galactosidase staining, reduced DEC1 and GLB1 mRNA expression, and abrogated phosphorylation of p53 at Ser15, and AMPKα at Thr172 (Fig. 4). In the metabolic rescue experiment, in which the energy crisis was recuperated by pyruvate supplement, the senescent phenotype was not reversed. While ATP level in the GAPDH-depleted cells supplemented with pyruvate returned to the normal level, cells did not proliferate, displayed SA-β-galactosidase staining, contained increased levels of DEC1 and GLB1 mRNA, and accumulated Ser 15-phosphorylated p53. Taken together, our findings strongly indicate the additional, yet to be characterized functions of GAPDH in regulation of metabolic crisis.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that in human carcinoma A549 cells, GAPDH knockdown triggers cellular senescence. We demonstrated that activation of senescence phenotype by GAPDH depletion occurred without DNA damage or telomere shortening, suggesting that induction of senescence by non-genotoxic agents can be used to inhibit tumor growth in LKB1-deficient cells. Our findings reveal novel aspects of senescence in carcinoma cancer cells linking it to GAPDH, and provide new insights in the development of anticancer therapies.

Research Highlights.

We examined the effect of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (GAPDH) depletion on proliferation of human carcinoma A549 cells

GAPDH depletion induces accelerated senescence in tumor cells via AMPK network, in the absence of DNA damage

Metabolic and genetic rescue experiments indicate that GAPDH has regulatory functions linking energy metabolism and cell cycle

Induction of senescence in LKB1-deficient lung cancer cells via GAPDH depletion suggests a novel strategy to control tumor cell proliferation

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We are grateful to Dr. Birnbaum (University of Pennsylvania) for the gift of anti-AMPK antibody. This work was partially supported by the National Cancer Institute [Grant R01-CA104729] to EK, and the Jayne Haines Center for Pharmacogenomics and Drug Safety, Temple University School of Pharmacy.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- AICAR

5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxyamide ribonucleoside

- Compound C

6-[4-(2-Piperidin-1-ylethoxy)phenyl]-3-pyridin-4-ylpyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine

- DAPI

4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- 2DG

2-deoxyglucose

- DSB

double strand breaks

- MTT

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- pGAPDH

GAPDH-expressing plasmid

- siRNA

short interfering RNA

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Collado M, Serrano M. Senescence in tumours: evidence from mice and humans. Nat.Rev.Cancer. 2010;10:51–57. doi: 10.1038/nrc2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmitt CA, Fridman JS, Yang M, Lee S, Baranov E, Hoffman RM, Lowe SW. A senescence program controlled by p53 and p16INK4a contributes to the outcome of cancer therapy. Cell. 2002;109:335–346. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00734-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sirover MA. On the functional diversity of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase: Biochemical mechanisms and regulatory control. Biochim.Biophys.Acta. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.05.010. Epub ahead of print PMID: 21640161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sen N, Hara MR, Kornberg MD, Cascio MB, Bae BI, Shahani N, Thomas B, Dawson TM, Dawson VL, Snyder SH, Sawa A. Nitric oxide-induced nuclear GAPDH activates p300/CBP and mediates apoptosis. Nat.Cell Biol. 2008;10:866–873. doi: 10.1038/ncb1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakajima H, Amano W, Fujita A, Fukuhara A, Azuma YT, Hata F, Inui T, Takeuchi T. The active site cysteine of the proapoptotic protein glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase is essential in oxidative stress-induced aggregation and cell death. J.Biol.Chem. 2007;282:26562–26574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704199200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colell A, Ricci JE, Tait S, Milasta S, Maurer U, Bouchier-Hayes L, Fitzgerald P, Guio-Carrion A, Waterhouse NJ, Li CW, Mari B, Barbry P, Newmeyer DD, Beere HM, Green DR. GAPDH and autophagy preserve survival after apoptotic cytochrome c release in the absence of caspase activation. Cell. 2007;129:983–997. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phadke MS, Krynetskaia NF, Mishra AK, Krynetskiy E. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase depletion induces cell cycle arrest and resistance to antimetabolites in human carcinoma cell lines. J.Pharmacol.Exp.Ther. 2009;331:77–86. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.155671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krynetskaia NF, Phadke MS, Jadhav SH, Krynetskiy EY. Chromatin-associated proteins HMGB1/2 and PDIA3 trigger cellular response to chemotherapy-induced DNA damage. Mol.Cancer Ther. 2009;8:864–872. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cawthon RM. Telomere length measurement by a novel monochrome multiplex quantitative PCR method. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ben-Porath I, Weinberg RA. The signals and pathways activating cellular senescence. Int.J.Biochem.Cell Biol. 2005;37:961–976. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kornberg MD, Sen N, Hara MR, Juluri KR, Nguyen JV, Snowman AM, Law L, Hester LD, Snyder SH. GAPDH mediates nitrosylation of nuclear proteins. Nat.Cell Biol. 2010;12:1094–1100. doi: 10.1038/ncb2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones RG, Plas DR, Kubek S, Buzzai M, Mu J, Xu Y, Birnbaum MJ, Thompson CB. AMP-activated protein kinase induces a p53-dependent metabolic checkpoint. Mol.Cell. 2005;18:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qian Y, Zhang J, Yan B, Chen X. DEC1, a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor and a novel target gene of the p53 family, mediates p53-dependent premature senescence. J.Biol.Chem. 2008;283:2896–2905. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708624200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee BY, Han JA, Im JS, Morrone A, Johung K, Goodwin EC, Kleijer WJ, DiMaio D, Hwang ES. Senescence-associated beta-galactosidase is lysosomal beta-galactosidase. Aging Cell. 2006;5:187–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Debacq-Chainiaux F, Pascal T, Boilan E, Bastin C, Bauwens E, Toussaint O. Screening of senescence-associated genes with specific DNA array reveals the role of IGFBP-3 in premature senescence of human diploid fibroblasts. Free Radic.Biol.Med. 2008;44:1817–1832. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng Z, Zhang H, Levine AJ, Jin S. The coordinate regulation of the p53 and mTOR pathways in cells. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2005;102:8204–8209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502857102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brahimi-Horn MC, Bellot G, Pouyssegur J. Hypoxia and energetic tumour metabolism. Curr.Opin.Genet.Dev. 2011;21:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawley SA, Davison M, Woods A, Davies SP, Beri RK, Carling D, Hardie DG. Characterization of the AMP-activated protein kinase kinase from rat liver and identification of threonine 172 as the major site at which it phosphorylates AMP-activated protein kinase. J.Biol.Chem. 1996;271:27879–27887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khanna KK, Jackson SP. DNA double-strand breaks: signaling, repair and the cancer connection. Nat.Genet. 2001;27:247–254. doi: 10.1038/85798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sundararaj KP, Wood RE, Ponnusamy S, Salas AM, Szulc Z, Bielawska A, Obeid LM, Hannun YA, Ogretmen B. Rapid shortening of telomere length in response to ceramide involves the inhibition of telomere binding activity of nuclear glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. J.Biol.Chem. 2004;279:6152–6162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310549200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell. 2006;124:471–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.