Abstract

Objectives. We examined whether neighborhood socioeconomic status (NSES) is associated with cognitive functioning in older US women and whether this relationship is explained by associations between NSES and vascular, health behavior, and psychosocial factors.

Methods. We assessed women aged 65 to 81 years (n = 7479) who were free of dementia and took part in the Women's Health Initiative Memory Study. Linear mixed models examined the cross-sectional association between an NSES index and cognitive functioning scores. A base model adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, education, income, marital status, and hysterectomy. Three groups of potential confounders were examined in separate models: vascular, health behavior, and psychosocial factors.

Results. Living in a neighborhood with a 1-unit higher NSES value was associated with a level of cognitive functioning that was 0.022 standard deviations higher (P = .02). The association was attenuated but still marginally significant (P < .1) after adjustment for confounders and, according to interaction tests, stronger among younger and non-White women.

Conclusions. The socioeconomic status of a woman's neighborhood may influence her cognitive functioning. This relationship is only partially explained by vascular, health behavior, or psychosocial factors. Future research is needed on the longitudinal relationships between NSES, cognitive impairment, and cognitive decline.

A growing body of research suggests that the characteristics of neighborhoods in which individuals live may influence their risk of poor self-rated health, cardiovascular disease, and mortality above and beyond individual-level characteristics.1–15 The proposed mechanisms by which lower quality neighborhoods may affect physical health include increased exposure to chronic stressors and pollutants in the environment; increased access to alcohol and cigarette outlets; barriers to physical activity; reduced social support, networks, and cohesion; and reduced access to high-quality health and social services. Three recent studies have linked lower neighborhood socioeconomic status (NSES) to lower cognitive function in UK adults older than 52 years,16 US adults older than 70 years living in urban areas,17 and Mexican Americans older than 65 years living in 5 southwestern states.18 However, the mechanisms underlying this relationship are not well understood.

Extensive epidemiological research has linked NSES to vascular-related conditions,4,19–22 poor health behaviors,23–25 and greater psychosocial stress.26–30 Incidentally, these factors also have well-established linkages with brain health such that individuals who have vascular-related conditions,31,32 who engage in low levels of physical activity, whose tobacco and alcohol consumption is excessive,33–35 and who have pronounced symptoms of depression or low social support36–38 are at increased risk for poor cognitive function. No studies to date have addressed whether these conditions may explain the relationship between NSES and cognitive function.

Previous studies indicate that neighborhood environments may influence poor cognitive function above and beyond individual-level demographic characteristics such as age, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, and income.16,17,39,40 Certain demographic subgroups may be especially vulnerable to the effects of NSES on cognitive function. For example, poor neighborhood environments may have stronger effects on older adults than on younger adults because older adults spend more time in their neighborhoods41; may have less access to social, financial, or health services; and have accumulated more exposures to stressors or pollutants. Non-White older adults who live in lower socioeconomic status (SES) neighborhoods may face discrimination or other stressors that may confer greater vulnerability to NSES effects on cognitive function.

Wight et al.17 examined individual- and neighborhood-level educational interactions among US adults. However, no US study to date has addressed whether other individual-level demographic factors may buffer or exacerbate the negative effects on cognitive function of living in a lower SES neighborhood using an index consisting of important measures of SES beyond education alone.

We examined whether an NSES index was related to cognitive function in a large, geographically and demographically diverse cohort of older US women with rich data on a sensitive measure of global cognitive function and a comprehensive set of clinical, behavioral, and psychosocial confounders. In addition, we assessed whether the relationship between NSES and cognitive function was explained by risk and protective factors for poor cognitive function that have also been linked with NSES and whether certain subgroups were more vulnerable to lower NSES.

METHODS

The Women's Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS) was an ancillary study to the Women's Health Initiative hormone therapy trials,42 2 large, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials designed to assess the relative effects of 0.625 milligrams per day of conjugated equine estrogen alone (E trial) or in combination with 2.5 milligrams per day of continuous medroxyprogesterone acetate (E+P trial) on the incidence of dementia and the level of cognitive functioning among postmenopausal women. The WHIMS study design, eligibility criteria, and recruitment procedures have been described previously.43,44 Briefly, 7479 women from 39 sites who were at least 65 years old and free of dementia were enrolled in WHIMS (4532 in the E+P trial and 2947 in the E trial) between May 1996 and December 1999. We geocoded addresses of WHIMS women at enrollment to census tracts and linked them with census data on NSES at the census tract level.

Study Sample

We excluded 1342 women from the overall sample (17.9% of 7479): those living outside of metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs; 797), which precluded us from accounting for geographic clustering, and those with missing, foreign, or military addresses or with geocoded census tracts that were missing NSES values (545). A total of 6137 women were included in the analyses. Women who were excluded from the analytic sample were slightly younger, less educated, and less wealthy than those who participated. They were also more likely to be married, to have higher levels of social support and social integration, to be less depressed, and to drink and smoke less (for each χ2 P< .05).

Dependent Variable: Cognitive Function

The Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MSE) was used to measure cognitive functioning at baseline.45 The 3MSE is a well-established measure of global cognitive function with good reliability and high sensitivity and specificity for detecting cognitive impairment and dementia in general and in WHIMS.46,47 3MSE assessments were administered by trained and certified technicians who were masked to treatment group and other outcomes. Administration times averaged 10 to 12 minutes. Total 3MSE score was a sum of 15 items and ranged from 0 to 100; higher scores reflected better cognitive functioning. Test items assessed temporal and spatial orientation, immediate and delayed recall, executive function (control and management of other cognitive processes), naming, verbal fluency, abstract reasoning, praxis, writing, and visuoconstructional abilities.

As a result of the skewed distribution toward higher 3MSE scores, a negative logarithmic transformation, −loge(102 − 3MSE score), was applied to yield a more normal distribution. Higher transformed scores indicated higher cognitive functioning. We then computed z scores from this index to express it in standard deviation units.

Independent Variables

Neighborhood socioeconomic status.

Data from the 2000 census were used to assess NSES at the census tract level. NSES was an index of 6 census tract variables: percentage of adults older than 25 years with less than a high school education, percentage of male unemployment, percentage of households with income levels below the poverty line, percentage of households receiving public assistance, percentage of female-headed households with children, and median household income. The composite measure was identified through confirmatory factor analyses and demonstrated in previous studies to be an important neighborhood-level predictor of health outcomes.19

The NSES index was scaled to range from 0 to 100 for US census tracts; higher scores indicated more affluent tracts. To obtain the NSES value for each woman at the baseline visit, which occurred between 1996 and 1999, we derived intercensal estimates using either geometric or linear interpolation according to the 1990 census tract definitions. Because some census tract boundaries changed between 1990 and 2000, we created a mapping between the 1990 and 2000 censuses using the 1990/2000 Census Tract Relationship File to facilitate the interpolation.

Individual-level covariates.

Individual-level demographic and lifestyle variables were measured at baseline by self-report.44 To examine potential factors influencing the relationship between NSES and cognitive function, we considered 3 groups of confounders that have been linked to NSES or cognitive function. Vascular factors included nonfatal coronary heart disease (myocardial infarction, angina, and coronary revascularization), diabetes, stroke, and hypertension, as assessed via self-reported history, measured blood pressures, and current medication use. Health behaviors included number of alcoholic drinks consumed per day, smoking status, and physical activity (episodes per week of moderate activity ≥ 20 minutes in duration).

Finally, psychosocial confounders included depressive symptoms, social support, and social integration. Depressive symptoms were measured with a validated algorithm of an 8-item screening instrument48 that incorporated 6 items from the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale49 and 2 items from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule.50 The total score ranged from 0 to 1; higher scores indicated more depressive symptoms. Social support was measured via 9 items selected from the Medical Outcomes Study.51 These items assessed perceived availability of emotional and informational support, tangible support, affectionate support, and positive social interactions (score range = 9–45). Social integration was an average of 2 items that measured how often a woman had attended religious services or meetings of clubs, lodges, or parent groups during the preceding month. Both items ranged from 1 (not at all) to 6 (every day).

Statistical Analysis

We examined the cross-sectional association between NSES and transformed 3MSE scores at baseline. We used a linear mixed model with random effects to account for clustering by MSA. Exploratory analyses indicated that clustering by census tract did not improve the model fit, whereas MSA-level clustering did improve the fit. The model building strategy first examined the unadjusted relationship between NSES and 3MSE score. Model 1 adjusted for basic demographic covariates that were significantly associated with NSES or cognitive function in bivariate regressions (median centered age, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, household income, and marital status). Hysterectomy status was included as a covariate because it distinguished between women who were randomized to the E trial as opposed to the E+P trial. A cut point of less than $10 000 was used in household income analyses because this income level appeared to define the strongest between-group differences.

We then examined whether adjustment for 3 separate sets of confounders (models 2–4) partially explained the association between NSES and 3MSE score in model 1. Model 2 included covariates from model 1 and the vascular factors defined earlier. Model 3 included covariates from model 1 and health behaviors. Model 4 included model 1 covariates and psychosocial factors. Tests of interactions assessed the consistency of associations for subgroups defined according to age (< 70 vs ≥70 years), race (White vs non-White), household income (< $10 000 vs ≥ $10 000), or educational status (≤ high school vs ≥ college). Individual-level covariate data on race/ethnicity, education, income, and marital status were missing in 6.7% of cases. Single imputation via IVEware52 was used to impute missing values. Supporting analyses, limited to women with complete data, were conducted to assess the sensitivity of our findings to imputation.

RESULTS

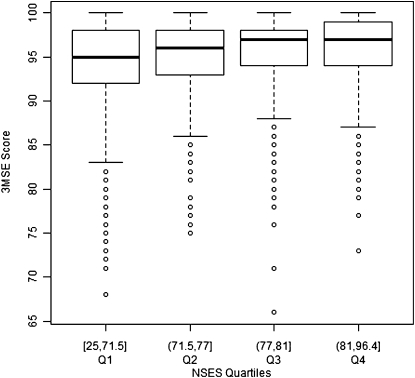

The baseline, raw mean 3MSE score was 95.1 for the 6137 women in the analytic sample (Table 1 ). Approximately 87% of the women were White, 7% were Black, 3% were Hispanic, and 3% were of another race or ethnicity. Approximately 92% had a high school degree or higher, 51% were married, and 39% had undergone a hysterectomy. The mean NSES value across individual women in the sample was 75.4. Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of raw 3MSE scores by NSES quartile, with quartile cut points defined by the distribution of NSES in the WHIMS sample.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Analytic Sample Characteristics: Women's Health Initiative Memory Study, United States, 1996–1999

| Sample (n = 6137), Mean ±SD or No. (%) | |

| 3MSE score | 95.1 ±4.4 |

| NSES index scorea | 75.4 ±8.5 |

| Individual-level characteristics | |

| Age, y | 70.2 ±3.9 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 5337 (87.0) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 429 (7.0) |

| Hispanic | 157 (2.6) |

| Other | 214 (3.5) |

| Educational attainment | |

| < high school | 472 (7.7) |

| High school | 1358 (22.1) |

| Some college | 2426 (39.5) |

| ≥ college | 1881 (30.7) |

| Household income, $ | |

| <10 000 | 354 (5.8) |

| 10 000–19 999 | 1176 (19.2) |

| 20 000–34 999 | 1889 (30.8) |

| 35 000–49 999 | 1282 (20.9) |

| 50 000–74 999 | 915 (14.9) |

| 75 000–99 999 | 305 (5.0) |

| 100 000–149 999 | 150 (2.4) |

| ≥150 000 | 66 (1.1) |

| Marital status | |

| Never married | 218 (3.6) |

| Divorced or separated | 781 (12.7) |

| Widowed | 1930 (31.4) |

| Marriage-like relationship | 52 (0.8) |

| Married | 3156 (51.4) |

| Hysterectomy | |

| No | 3744 (61.0) |

| Yes | 2393 (39.0) |

| Vascular factors | |

| History of or current coronary heart disease | 588 (9.6) |

| History of or current stroke | 103 (1.7) |

| History of or current diabetes | 518 (8.4) |

| History of or current hypertension | 3289 (53.6) |

| Health behavior factors | |

| Alcohol intake, drinks/d | |

| None | 2729 (44.5) |

| <1 | 2735 (44.6) |

| ≥1 | 673 (11.0) |

| Smoking status | |

| Never smoked | 3170 (51.7) |

| Past smoker | 2501 (40.8) |

| Current smoker | 466 (7.6) |

| Physical activity | |

| No activity | 1095 (17.8) |

| Some activity of limited duration, frequency, or intensity | 2752 (44.8) |

| 2–3 times/wkb | 981 (16.0) |

| ≥4 times/wkb | 1293 ±21.1 |

| Psychosocial factors | |

| Depressive symptoms score | 0.03 ±0.1 |

| Social support score | 35.5 ±7.9 |

| Social integration score | 2.6 ±1.1 |

Notes. 3MSE = Modified Mini-Mental Examination; NSES = neighborhood socioeconomic status (census tract level).

Across all Women's Health Initiative Memory Study census tracts.

Moderate or strenuous activity of at least 20 min in duration.

FIGURE 1.

Box plot graphs of raw Modified Mini-Mental Examination (3MSE) scores, by neighborhood socioeconomic status (NSES) quartile: Women's Health Initiative Memory Study, United States, 1996–1999.

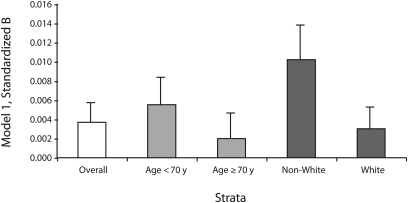

Note. Global cognitive function, measured with the Modified Mini-Mental Examination, was scaled in standard deviation units. Model 1 adjusted for basic covariates (median centered age, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, household income, marital status, and hysterectomy status). Census tract–level neighborhood socioeconomic status (NSES) and age interaction P = .05; NSES and race interaction P = .07.

Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status and Cognitive Function

Table 2 displays coefficients and standard errors for the cross-sectional association between NSES and transformed 3MSE score. Without any covariate adjustment, living in a neighborhood with a 1-unit higher NSES value (the median NSES value for the WHIMS sample was 77, with a range of 25–96) was significantly associated with a level of cognitive functioning that was 0.0235 standard deviations higher (P < .001). The intraclass correlation was 0.052.

TABLE 2.

Association Between Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status and Global Cognitive Function: Women's Health Initiative Memory Study, United States, 1996–1999

| B (SE) | |

| Unadjusted | 0.0235*** (0.0015) |

| Model 1a | 0.0037** (0.0017) |

| Model 2b | 0.0034** (0.0017) |

| Model 3c | 0.0028* (0.0017) |

| Model 4d | 0.0028* (0.0017) |

Note. Global cognitive function, measured with the Modified Mini-Mental Examination, was scaled in standard deviation units. Neighborhood socioeconomic status was measured at the census tract level.

Adjusted for basic covariates (centered median age, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, household income, marital status, and hysterectomy status).

Included basic covariates and vascular factors (history of or current coronary heart disease, diabetes, stroke, and hypertension).

Included basic covariates and health behavior factors (alcohol intake, smoking status, and physical activity).

Included basic covariates and psychosocial factors (depressive symptoms, social support, and social integration).

*P ≤ .1; **P ≤ .05; ***P ≤ .01.

This relationship remained significant (B = 0.0037, P = .02) after basic covariates were included (model 1). Adjustment for vascular factors (model 2) attenuated the strength of the relationship slightly (B = 0.0034, P = .03). Adjustment for health behavior factors (model 3) or psychosocial factors (model 4) also attenuated the relationship (B = 0.0028, P = .07, and B = 0.0028, P = .08, respectively). Coronary heart disease (P = .06) in model 2, alcohol intake (P < .001) in model 3, and depressive symptoms (P = .03) in model 4 were the only significant predictors of cognitive function after adjustment for NSES.

Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status and Cognitive Function Modifiers

With minimal covariate adjustment (model 1), the interaction between NSES and age was significant at P = .05, and the interaction between NSES and race was marginally significant (P = .07). As shown in Figure 2, the fitted slopes were greater for younger (vs older) women and for non-White (vs White) women. Adjustment for vascular, health behavior, and psychosocial factors in models 2 through 4 did not materially change these results. We found no evidence that relationships varied among subgroups defined according to household income and education (P > .1).

FIGURE 2.

Census tract–level neighborhood socioeconomic status and global cognitive function: Women's Health Initiative Memory Study, United States, 1996–1999.

Note. Linear regression parameter estimates (margin of error) are for the overall sample and are stratified by individual-level age and race.

Sensitivity analyses among only women who had complete, nonimputed data yielded similar results comparable to the analyses among the full sample. Stratified analyses were similar, the only difference being that education-stratified analyses in the reduced sample without imputed data revealed a stronger association between higher NSES and higher cognitive function among women with more educational attainment (P < .05).

DISCUSSION

This study of a national sample of older US women provides consistent evidence that living in a neighborhood with higher NSES is associated with higher cognitive functioning, above and beyond individual-level demographic characteristics such as age, race/ethnicity, income, education, and marital status. This is the largest US-based study to examine the cross-sectional relationship between area-level socioeconomic composition and cognitive function and to explore potential underlying mechanisms as well as vulnerability to low NSES across age, race, income, and education.

We hypothesized that the relationship between higher NSES and higher cognitive function among women would be explained by the association between NSES and vascular factors, health behavior, and psychosocial factors. These factors only partially explained the relationship between NSES and cognitive function, as indicated by the slightly smaller magnitudes of the regression parameters. In particular, the findings for the overall sample indicated that adjustment for health behavior and psychosocial factors resulted in the greatest relative reduction in the association between NSES and cognitive function. However, accounting for the 3 groups of confounders did not completely explain the relationship, suggesting that there may have been other factors that were not accounted for. These factors may include better access to high-quality health services, cognitive activity, or intake of foods high in antioxidants that have been shown to be protective against poor cognitive function.53–56

Our findings corroborate previous research on NSES and cognitive function. Lang et al.16 found that higher neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation was cross-sectionally related to lower cognitive functioning. Further adjustment for systolic blood pressure, stroke, and depression did not account for the association between neighborhood deprivation and cognitive function. Accounting for perceived access to medical resources or stores and local shops also did not explain the association. Wight et al.17 found that lower neighborhood-level education was cross-sectionally associated with lower cognitive performance, even after adjustment for demographic factors, depressive symptoms, and chronic health conditions. Although these studies were nationally representative of UK adults aged 52 years or older16 or US adults older than 70 years,17 our study adds to the literature by including rural areas (in addition to urban or suburban areas) and by measuring cognitive functioning with the 3MSE, which is more sensitive to detecting cognitive impairment than are the tests used in those studies.57,58

We also hypothesized that the relationship between higher NSES and higher cognitive function would be more pronounced among non-White women, older women, and women of lower individual SES. However, stratified analyses and models with interaction terms indicated that higher NSES was protective for younger and non-White women. Individual-level income and education did not modify the effects of NSES.

Lang et al.16 found that neighborhood deprivation's association with poor cognition was more pronounced among older men and women. Our findings, which can also be interpreted as an association between lower NSES and lower cognitive function for younger and non-White women, conflict with the results of Lang et al. In addition, our results do not support previous literature suggesting that older individuals are more vulnerable to lower NSES neighborhood effects owing to a longer duration of exposure to poor or declining neighborhood conditions; greater acquired biological, psychological, and cognitive vulnerability; general declines in physical function that may limit their mobility to areas outside of their neighborhood; and greater reliance on local health and social resources.41,59

It is unclear why older women in WHIMS were not as vulnerable to the effects of living in a lower SES neighborhood; it may be that these women were exposed to unmeasured factors accumulated over their lifetime that overwhelmed the effects of NSES on cognition. In addition, survivorship bias may have played a role as to whether women living in lower SES neighborhoods had worse cognitive function and higher mortality rates than did those with better cognitive function. Both of these hypotheses should be examined further.

Nonetheless, our findings suggest that it may not be too early to intervene in women younger than 70 years to mitigate the effects of lower NSES on risk of lower cognitive function. Discrepant findings may be a result of the fact that Lang et al.16 may have included women with dementia. In addition, the variability of NSES in the WHIMS sample was greater in the younger age group than it was in the older age group, which may have promoted our ability to detect a relationship among the younger group. Because the WHIMS did not include data on duration of current residence, we cannot rule out the possibility that older women were more likely to have moved recently and, therefore, to live in a neighborhood of different SES than the neighborhoods in which they spent most of their lives. This bias would be most relevant if NSES has a more acute effect. However, research indicates that neighborhoods are slow to change over time, and the NSES values for different neighborhoods that individuals may move in and out of do not change drastically over the life course.3,60,61

To our knowledge, this study is the first to report differences in the relationship between NSES and cognitive function by race. Our results concur with our hypothesis that non-Whites may be more vulnerable to NSES effects than are Whites because of their greater susceptibility to the effects of stressors or their reduced access to social, psychosocial, and economic resources. It is possible that the ability to observe this association was facilitated by the larger variance in NSES values among non-Whites than among Whites. Unlike Wight et al.,17 who found that the effect of living in a neighborhood with lower educational attainment on cognitive performance was modified by individual-level education, we did not find significant effect modification by education; however, we did find a stronger effect among those with higher education in sensitivity analyses that excluded imputed data. Women excluded from the analytic sample were less educated, suggesting that the association among women with lower education may be more sensitive to missing data.

Our data were drawn from volunteers without dementia who were eligible for a trial of postmenopausal hormone therapy, yet we still observed a robust association between NSES and 3MSE score after adjustment for vascular factors and a reduced association after adjustment for health behavior and psychosocial factors. Without covariate adjustment, a 2–standard-deviation difference in NSES (i.e., 17 units) was associated with an approximately 0.4–standard-deviation difference (17 × 0.0235) in our measure of cognitive function. Covariate adjustment for potential confounders in our models attenuated this relationship so that a 2–standard-deviation NSES difference was associated with 0.04– to 0.06–standard-deviation differences (17 × 0.0028 and 17 × 0.0037, respectively) in cognitive function. To provide some context for comparison purposes, the WHIMS trials revealed that assignment to conjugated equine estrogen therapy without and with medroxyprogesterone acetate was associated with decrements in cognitive function of 0.08 and 0.09 standard deviations, respectively, over the course of the trials.62 These relatively small mean differences were associated with significant increases in dementia and brain atrophy.43,63,64

Strengths and Limitations

This study had a number of important strengths. First, this is the largest US study of contextual-level socioeconomic status on cognitive function. Second, our primary outcome instrument, the 3MSE, is a widely used measure of global cognitive function and a dementia screening tool that covers a wider range of cognitive domains,65 includes more difficult items, and has a higher sensitivity to cognitive impairment than those of other tests of global cognitive function.45 Third, the WHIMS encompassed a demographically and geographically diverse sample of women living in 35 states and rural, mixed, and urban areas (3%, 76%, and 21%, respectively, of all sample tracts), lending further support for contextual-level effects on cognitive function in the United States. Although we excluded women living outside MSAs, some MSAs included rural and mixed rural–urban census tracts. In addition, our study expanded on another US-based national study17 by including women younger than 70 years.

Fourth, we examined a comprehensive and multifaceted SES index that builds on previous literature17,39 focusing on education, income, or classes of neighborhoods (e.g., transitional, suburban). Finally, we considered a relatively large number of confounders to examine potential mechanistic pathways. Inclusion of these confounders indicated that higher NSES was independently and consistently associated with cognitive functioning even after important demographic, vascular, health behavior, and psychosocial confounders had been taken into account.

Despite these strengths, several limitations of our analyses should be noted. We examined cross-sectional associations between NSES, cognitive function, and confounding variables measured at baseline. Thus, any causal relationships or indication of mediation resulting from adjustment for vascular, health behavior, and psychosocial covariates and examination of the reduction of main effects66 must be interpreted with caution. The WHIMS sample was not population based and included mostly well-educated women who had volunteered and were eligible for a clinical trial of postmenopausal hormone therapy and who probably had substantial interest in their health. It also required participants to have plans to stay in their current geographic area, so our results may not be generalizable to other populations, including men.

The generalizability of our sample may have been further restricted as a result of missing NSES data or information on MSAs, which limited the sample to 82% of the entire WHIMS cohort. In addition, we cannot rule out the potential for residual confounding or selection effects such that individuals with similar characteristics beyond those we accounted for may systematically choose to live in similar neighborhoods.

Public Health Implications

Poor cognitive function in late life has been linked to steeper declines in cognitive function over time, which increases the risk of dementia such as Alzheimer's disease.67,68 Our analyses suggest that policies that aim to bolster NSES or early public health interventions that target modifiable risk factors such as poor health behaviors and facilitate social support and integration among women in lower SES neighborhoods may also provide some protection against the harmful effects of lower NSES on poor cognitive function.

In particular, the relationship between living in a lower SES neighborhood and moderate alcohol intake or more depressive symptoms indicates that these may be key intermediate factors to intervene on for individuals living in high-risk neighborhoods. Stratified analyses showing differential effects by age and race indicate that targeted interventions among non-White women or women younger than 70 years may help mitigate the harmful effects of lower NSES. Future research should examine the longitudinal relationship between living in a lower SES neighborhood and risks for steeper cognitive declines and subclinical syndromes (e.g., mild cognitive impairment) that increase the risk for dementia.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI; 1-R01-HL084425) to Chloe E. Bird. The Women's Health Initiative (WHI) is funded by the NHLBI (contracts N01WH22110, 24152, 32100-2, 32105-6, 32108-9, 32111-13, 32115, 32118-32119, 32122, 42107-26, 42129-32, and 44221).

This work was presented at the annual conference of the American Association of Geriatric Psychiatry, San Antonio, TX, March 2011.

We acknowledge the contributions of WHI investigators in the program office: Jacques Rossouw, Shari Ludlam, Joan McGowan, Leslie Ford, and Nancy Geller (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, MD). We also acknowledge the contributions of investigators in the clinical coordinating center: Ross Prentice, Garnet Anderson, Andrea LaCroix, and Charles L. Kooperberg (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA); Evan Stein (Medical Research Labs, Highland Heights, KY); and Steven Cummings (University of California at San Francisco). Finally, we acknowledge the contributions of investigators in the clinical centers: Sylvia Wassertheil-Smoller (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY); Haleh Sangi-Haghpeykar (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX); JoAnn E. Manson (Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA); Charles B. Eaton (Brown University, Providence, RI); Lawrence S. Phillips (Emory University, Atlanta, GA); Shirley Beresford (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA); Lisa Martin (George Washington University Medical Center, Washington, DC); Rowan Chlebowski (Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor- UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA); Erin LeBlanc (Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research, Portland, OR); Bette Caan (Kaiser Permanente Division of Research, Oakland, CA); Jane Morley Kotchen (Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee); Barbara V. Howard (MedStar Research Institute/Howard University, Washington, DC); Linda Van Horn (Northwestern University, Evanston, IL); Henry Black (Rush Medical Center, Chicago, IL); Marcia L. Stefanick (Stanford Prevention Research Center, Stanford, CA); Dorothy Lane (State University of New York at Stony Brook); Rebecca Jackson (Ohio State University, Columbus); Cora E. Lewis (University of Alabama at Birmingham); Cynthia A. Thomson (University of Arizona, Tucson); Jean Wactawski-Wende (University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY); John Robbins (University of California at Davis, Sacramento, CA); F. Allan Hubbell (University of California at Irvine); Lauren Nathan (University of California at Los Angeles); Robert D. Langer (University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA); Margery Gass (University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH); Marian Limacher (University of Florida, Gainesville); J. David Curb (University of Hawaii, Honolulu); Robert Wallace (University of Iowa, Iowa City); Judith Ockene (University of Massachusetts/Fallon Clinic, Worcester); Norman Lasser (University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Newark); Mary Jo O'Sullivan (University of Miami, Miami, FL); Karen Margolis (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis); Robert Brunner (University of Nevada, Reno, NV); Gerardo Heiss (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill); Lewis Kuller (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA); Karen C. Johnson (University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis); Robert Brzyski (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio); Gloria E. Sarto (University of Wisconsin, Madison); Mara Vitolins (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC); and Michael S. Simon (Wayne State University School of Medicine/Hutzel Hospital, Detroit, MI).

Human Participant Protection

This study was approved by the institutional review boards of the authors’ various institutions. Participants provided written informed consent.

References

- 1.Anderson RT, Sorlie P, Backlund E, Johnson N, Kaplan GA. Mortality effects of community socioeconomic status. Epidemiology. 1997;8(1):42–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cubbin C, Winkleby MA. Protective and harmful effects of neighborhood-level deprivation on individual-level health knowledge, behavior changes, and risk of coronary heart disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(2):559–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diez Roux AV. Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(11):1783–1789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diez-Roux AV, Nieto FJ, Muntaner C, et al. Neighborhood environments and coronary heart disease: a multilevel analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146(1):48–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feldman PJ, Steptoe A. How neighborhoods and physical functioning are related: the roles of neighborhood socioeconomic status, perceived neighborhood strain, and individual health risk factors. Ann Behav Med. 2004;27(2):91–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haan M, Kaplan GA, Camacho T. Poverty and health: prospective evidence from the Alameda County Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;125(6):989–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones K, Duncan C. Individuals and their ecologies: analysing the geography of chronic illness within a multilevel modeling framework. Health Place. 1995;1(1):27–30 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leclere F, Rogers R, Peters K. Ethnicity and mortality in the United States: individual and community correlates. Soc Forces. 1997;76(1):169–198 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lochner KA, Kawachi I, Brennan RT, Buka SL. Social capital and neighborhood mortality rates in Chicago. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(8):1797–1805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robert SA. Community-level socioeconomic status effects on adult health. J Health Soc Behav. 1998;39(1):18–37 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Neighborhood disadvantage, disorder, and health. J Health Soc Behav. 2001;42(3):258–276 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh GK, Siahpush M. Increasing inequalities in all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among US adults aged 25–64 years by area socioeconomic status, 1969–1998. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(3):600–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sundquist K, Malmstrom M, Johansson SE. Neighbourhood deprivation and incidence of coronary heart disease: a multilevel study of 2.6 million women and men in Sweden. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(1):71–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wainwright NW, Surtees PG. Places, people, and their physical and mental functional health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(4):333–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yen IH, Syme SL. The social environment and health: a discussion of the epidemiologic literature. Annu Rev Public Health. 1999;20:287–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lang IA, Llewellyn DJ, Langa KM, Wallace RB, Huppert FA, Melzer D. Neighborhood deprivation, individual socioeconomic status, and cognitive function in older people: analyses from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(2):191–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wight RG, Aneshensel CS, Miller-Martinez D, et al. Urban neighborhood context, educational attainment, and cognitive function among older adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(12):1071–1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheffield KM, Peek MK. Neighborhood context and cognitive decline in older Mexican Americans: results from the Hispanic Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(9):1092–1101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bird CE, Shih RA, Eibner C, et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic status and incident coronary heart disease among women. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(suppl 1):S127 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sundquist K, Winkleby M, Ahlen H, Johansson SE. Neighborhood socioeconomic environment and incidence of coronary heart disease: a follow-up study of 25,319 women and men in Sweden. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):655–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winkleby M, Sundquist K, Cubbin C. Inequities in CHD incidence and case fatality by neighborhood deprivation. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(2):97–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nordstrom CK, Diez Roux AV, Jackson SA, Gardin JM. The association of personal and neighborhood socioeconomic indicators with subclinical cardiovascular disease in an elderly cohort: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(10):2139–2147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boardman JD, Finch BK, Ellison CG, Williams DR, Jackson JS. Neighborhood disadvantage, stress, and drug use among adults. J Health Soc Behav. 2001;42(2):151–165 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dubowitz T, Heron M, Bird CE, et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic status and fruit and vegetable intake among whites, blacks, and Mexican Americans in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(6):1883–1891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore LV, Diez Roux AV. Associations of neighborhood characteristics with the location and type of food stores. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(2):325–331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cutrona CE, Wallace G, Wesner KA. Neighborhood characteristics and depression: an examination of stress processes. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2006;15(4):188–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Gannon-Rowley T. Assessing “neighborhood effects”: social processes and new directions in research. Annu Rev Sociol. 2002;28:443–478 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wickrama KA, Conger RD, Wallace LE, Elder GH., Jr Linking early social risks to impaired physical health during the transition to adulthood. J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44(1):61–74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aneshensel CS, Wight RG, Miller-Martinez D, Botticello AL, Karlamangla AS, Seeman TE. Urban neighborhoods and depressive symptoms among older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62(1):S52–S59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mair CF, Diez Roux A, Galea S. Are neighborhood characteristics associated with depressive symptoms? A critical review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(11):940–946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cacciatore F, Abete P, Ferrara N, et al. Congestive heart failure and cognitive impairment in an older population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(11):1343–1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Di Carlo A, Baldereschi M, Amaducci L, et al. Cognitive impairment without dementia in older people: prevalence, vascular risk factors, impact on disability. The Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(7):775–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Espeland MA, Coker LH, Wallace R, et al. Association between alcohol intake and domain-specific cognitive function in older women. Neuroepidemiology. 2006;27(1):1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ott A, Andersen K, Dewey ME, et al. Effect of smoking on global cognitive function in nondemented elderly. Neurology. 2004;62(6):920–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sabia S, Nabi H, Kivimaki M, Shipley MJ, Marmot MG, Singh-Manoux A. Health behaviors from early to late midlife as predictors of cognitive function: the Whitehall II Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(4):428–437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chodosh J, Kado DM, Seeman TE, Karlamangla AS. Depressive symptoms as a predictor of cognitive decline: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(5):406–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ganguli M, Du Y, Dodge HH, Ratcliff GG, Chang CC. Depressive symptoms and cognitive decline in late life: a prospective epidemiological study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(2):153–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seeman TE, Lusignolo TM, Albert M, Berkman L. Social relationships, social support, and patterns of cognitive aging in healthy, high-functioning older adults: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. Health Psychol. 2001;20(4):243–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Espino DV, Lichtenstein MJ, Palmer RF, Hazuda HP. Ethnic differences in Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores: where you live makes a difference. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(5):538–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.George LK, Landerman LR, Blazer DG. Cognitive impairment. Robbins LN, Regier DA, Psychiatric Disorders in America.New York, NY: Free Press; 1991:291–327 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cagney KA, Browning CR, Wen M. Racial disparities in self-rated health at older ages: what difference does the neighborhood make? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60(4):S181–S190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stefanick ML, Cochrane BB, Hsia J, Barad DH, Liu JH, Johnson SR. The Women's Health Initiative postmenopausal hormone trials: overview and baseline characteristics of participants. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(suppl 9):S78–S86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shumaker SA, Reboussin BA, Espeland MA, et al. The Women's Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS): a trial of the effect of estrogen therapy in preventing and slowing the progression of dementia. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19(6):604–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shumaker SA, Legault C, Kuller L. Conjugated equine estrogen alone, pooled hormone therapy, and incidence of probable dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women. JAMA. 2004;291:2947–2958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Teng EL, Chui HC. The Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) Examination. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48(8):314–318 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bland RC, Newman SC. Mild dementia or cognitive impairment: the Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS) as a screen for dementia. Can J Psychiatry. 2001;46(6):506–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Espeland MA, Rapp SR, Robertson J, et al. Benchmarks for designing two-stage studies using modified Mini-Mental State Examinations: experience from the Women's Health Initiative Memory Study. Clin Trials. 2006;3(2):99–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tuunainen A, Langer RD, Klauber MR, Kripke DF. Short version of the CES-D (Burnam screen) for depression in reference to the structured psychiatric interview. Psychiatry Res. 2001;103(2–3):261–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS. National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38(4):381–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS Social Support Survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):705–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Raghunathan TE, Solenberger PW, van Hoewyk J. IVEware: Imputation and Variance Estimation Software User Guide. Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Methodology Program, University of Michigan; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Altschuler A, Somkin CP, Adler NE. Local services and amenities, neighborhood social capital, and health. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(6):1219–1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carlson MC, Saczynski JS, Rebok GW, et al. Exploring the effects of an “everyday” activity program on executive function and memory in older adults: Experience Corps. Gerontologist. 2008;48(6):793–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Joseph JA, Shukitt-Hale B, Willis LM. Grape juice, berries, and walnuts affect brain aging and behavior. J Nutr. 2009;139(9):1813S–1817S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wengreen HJ, Munger RG, Corcoran CD, et al. Antioxidant intake and cognitive function of elderly men and women: the Cache County Study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2007;11(3):230–237 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McDowell I, Kristjansson B, Hill GB, Hebert R. Community screening for dementia: the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) and Modified Mini-Mental State Exam (3MS) compared. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(4):377–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ. The Mini-Mental State Examination: a comprehensive review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40(9):922–935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Glass TA, Balfour JL. Neighborhoods, aging, and functional limitations. : Kawachi I, Berkman L, Neighborhoods and Health. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2003:303–334 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Geronimus AT, Bound J. Use of census-based aggregate variables to proxy for socioeconomic group: evidence from national samples. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148(5):475–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grafova IB, Freedman VA, Kumar R, Rogowski J. Neighborhoods and obesity in later life. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(11):2065–2071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Espeland MA, Brunner RL, Hogan PE. Long-term effects of conjugated equine estrogen therapies on domain-specific cognitive function. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(7):1263–1271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Resnick SM, Espeland MA, Jaramillo SA. Effects of postmenopausal hormone therapy on regional brain volumes in older women. Neurology. 2009;72(2):135–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Espeland MA, Tindle HA, Bushnell CA. Brain volumes, cognitive impairment, and conjugated equine estrogens. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med. 2009;64(12):1243–1250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cullen B, O'Neil B, Evans JJ, Coen RF, Lawlor BA. A review of screening tests for cognitive impairment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(8):790–799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Backman L, Jones S, Berger AK, Laukka EJ, Small BJ. Multiple cognitive deficits during the transition to Alzheimer's disease. J Intern Med. 2004;256(3):195–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jones S, Small BJ, Fratiglioni L, Backman L. Predictors of cognitive change from preclinical to clinical Alzheimer's disease. Brain Cogn. 2002;49(2):210–213 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]