Abstract

The wide publicity related to human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines has led to a sense that HPV vaccine programs are inevitable in both developed and developing countries, whereas 2 existing methods of screening—visual inspection with ascetic acid (VIA) and DNA testing—have received much less attention.

These screening methods detect cervical lesions better than does the Papanicolaou test and allow immediate treatment, minimizing loss to follow-up. These advantages may outweigh the strengths of HPV vaccines.

Priority should be given to improving screening coverage with VIA and DNA tests, focusing on women older than 30 years and underserved populations in all countries. This approach will save the lives of millions of women who have already been exposed to HPV and will develop cervical cancer during the next 20 years.

Cervical cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality among women in developing countries, causing an estimated 273 000 deaths worldwide each year.1 Eighty-three percent of these deaths occur in developing countries.2 More than 99% of cervical cancer cases are linked to human papillomavirus (HPV).3 The development of vaccines that prevent HPV infection has created tremendous enthusiasm for and momentum toward their introduction in a broad range of countries.3 We discuss the strengths and weaknesses of available program strategies for reducing cervical cancer, including HPV vaccination. We focus on the epidemiological, programmatic, and cost implications of various strategies.

THE EPIDEMIOLOGY OF HUMAN PAPILLOMAVIRUS

There are about 40 varieties (genotypes) of HPV that infect the human genital tract; worldwide, however, 7 types cause approximately 87% of cases of cervical cancer and only 2 types—HPV 16 and 18—cause about 70% of cases. HPV is common and easily transmitted, so most women are infected with it soon after they become sexually active. Although condoms lower the risk if used correctly and consistently, HPV can still infect parts of the genital area that are not protected from skin contact by condoms.4

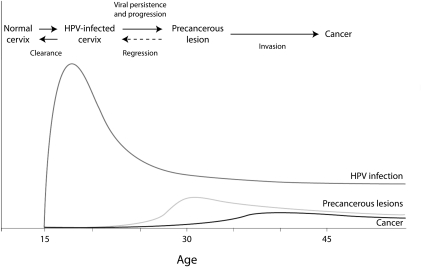

As Figure 1 shows, the prevalence of HPV infection increases sharply after sexual debut; during the next few years, most women naturally shed the virus, but some women have persistent infections. In time, these infections can lead to abnormal cell growth; after 10 to 20 years, persistent infection (if not detected and treated) can develop into cervical cancer. Although the prevalence of HPV infection is high worldwide, women in low-income countries have higher rates of cancer, largely because of a lack of programs to screen for and treat early stages of disease.

FIGURE 1.

Illustrative graph of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, precancerous lesions, and cervical cancer, by age of women.

Source. World Health Organization.3 (Original in Schiffman M, Castle PE. The promise of global cervical-cancer prevention. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(20):2101–2103. [© 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society. Adapted with permission.])

CURRENT COVERAGE OF CERVICAL CANCER PREVENTION PROGRAMS

To date, national programs have focused on cytology screening through the Papanicolaou (Pap) test. A review of cancer screening in 57 countries using data from 2002 found that only 18% of 25- to 64-year-old women in developing countries had a pelvic examination and Pap test in the last 3 years, compared with 63% in developed countries.2 Screening prevalence ranged from greater than 80% in parts of Europe to less than 1% in Bangladesh, Ethiopia, and Myanmar. Even allowing for some underreporting (e.g., if women did not know or remember that they had undergone a Pap test), there are clearly serious deficiencies. For example, in Ethiopia, Bangladesh, and Malawi, less than 10% of women reported ever having had a pelvic examination.

As might be expected, coverage of cervical cancer screening programs varies greatly by socioeconomic status in most, but not all, countries. Overall, in the 57 countries reviewed, 9% of women in the poorest quintile had received a Pap test in the last 3 years, compared with 64% in the wealthiest quintile.2 A notable exception to this pattern was India, where coverage was 6% for the richest group of women and 4% for the poorest. In general, screening coverage decreases among women aged 45 years and older, although cervical cancer rates increase with age.

STRATEGIES FOR CERVICAL CANCER REDUCTION

Strategies for reducing cervical cancer deaths vary considerably in terms of the stage of the disease process, the strategy's effectiveness, and the level of technology required. These factors, in turn, have important implications for program cost and feasibility.

Screening and Treatment

Given the difficulty of preventing infection with HPV, until recently the only strategy for reducing the incidence of cervical cancer has been screening and treatment. There are several approaches to screening for cervical cancer, including cytological testing (Pap test), HPV DNA testing for high-risk strains of the HPV virus, and visual inspection of the cervix with acetic acid (VIA), with or without magnification. Cytological testing is the most common screening method in developed countries, but it requires trained technicians and good laboratories that are often unavailable in developing countries.

There are 2 types of HPV DNA testing: one which requires a laboratory to read the sample and another (careHPV, created by PATH and QIAGEN for use in low-income countries) that can be read on site by a health care provider (expected to be on the market in 2012).

Visual inspection with ascetic acid is an underused screening method, given its low cost and relative ease to administer. Because VIA allows diagnosis of abnormal cells almost immediately, women can be treated in the same visit with cryotherapy (applying liquid carbon dioxide or nitrogen to the cervix), which reduces costs and loss to follow-up.

Effectiveness of Screening Methods

All HPV screening methods, when done properly, can detect most precancerous lesions; none, however, is perfect. For example, a cluster-randomized trial in 52 villages in India found that

The detection rate of CIN grade 1 was higher in the VIA group than in either the HPV-testing group or the cytologic-testing group (P<0.001 for both comparisons). The detection rates of CIN grade 2 or 3 lesions and invasive cancer were similar in the three intervention groups.5(p1389–1390)

A review of studies in developing countries6 found that VIA had the highest level of sensitivity, although the range was wide (50%–96% of cases identified). Cytology testing also had a wide range of sensitivity (31%–78%), but even the best score was disappointing. HPV DNA testing has slightly lower sensitivity (61%–90%) than VIA, but it has a narrower range than the other 2 tests. The range in specificity of each test is also notable (VIA, 44%–97%; cytology testing, 91%–99%; HPV DNA testing, 62%–94%).

Cytological testing has a wide range of sensitivity rates (31%–78%), largely because the quality of laboratories where samples are read varies, as does the preservation of samples in transport. A study in Honduras found that among 339 women who had both VIA and a Pap test, 49 VIA examinations were read as abnormal.7 Of these, 23 had biopsy-proven dysplasia. None of the 23 true positive cases was identified when the Pap tests were read in Honduras and only 4 were identified when the slides were reread in the United States.

Even in developed countries, the results of Pap tests are much less reliable than many people realize. Most high-quality studies find sensitivity rates of less than 60%.8

At their best, the specificity of each of the 3 screening tests reaches nearly perfect levels (94%–99%), but the range of results is widest for VIA, in part because the surface of a woman's cervix reacts to the acetic acid for a number of reasons, including polyps, inflammatory conditions, and squamous metaplasia (noncancerous changes in the lining of the cervix).9

Treatment Following Screening

To reduce morbidity and mortality, screening must be followed by treatment, either at the same or a following visit. Women who have precancerous lesions on the cervix are usually treated with 1 of the following methods:

Cryotherapy—does not require electricity and can be performed safely and effectively by nurses and midwives.

LEEP (loop electrosurgical excision procedure)—requires heavier and more expensive equipment, reliable electricity, and highly skilled providers. It is associated with a higher risk of severe bleeding.10

Cone biopsy—general or spinal anesthesia is sometimes used, and cone biopsies are often done in a hospital or outpatient surgery clinic.11

Laser ablation—requires highly skilled providers, expensive equipment, and electricity.

All of these procedures prevent abnormal tissue from progressing to invasive cancer in 85% to 89% of cases.12 Once cervical cancer has developed, these are not appropriate treatment methods.

Prevention of Infection With Vaccines

The development of vaccines that are effective in preventing infection with HPV opens up a new route for prevention of cervical cancer. At present, there are 2 vaccines on the market: Gardasil and Cervarix. Both vaccines are currently approved in approximately 100 countries, including the United States,13 and offer virtually complete protection for girls and women against HPV genotypes 16 and 18, which cause 70% of cervical cancer worldwide. Both vaccines have a known duration of protection of at least 5 years; clinical trials are still in progress to show the full duration of protection. Both are administered in a series of 3 injections over 6 months; they must be kept refrigerated (but not frozen) and should not be exposed to sunlight.

The intuitive appeal of vaccination is enormous, as can be seen from the fact that around 100 countries have approved the use of both vaccines in only a few years, including countries with poor screening coverage such as Ethiopia. Although “an ounce of prevention is better than a pound of cure,” a variety of considerations should be taken into account when deciding on the most appropriate next steps governments should take in trying to reduce cervical cancer in their populations. These considerations range from the practical to the ethical.

THE PROS AND CONS OF VARIOUS STRATEGIES

Deciding what approaches to use to reduce deaths from cervical cancer requires weighing a number of disparate considerations against national or local conditions and priorities.

Potential Reduction in Cancer Deaths

Although it may be commonly believed that HPV vaccine is the most effective approach to reduce cancer deaths, the reality is more complicated. If HPV vaccination provides 99% effective protection against genotypes 16 and 18 (about 70% of the HPV infections that cause cancer), then a 69% reduction in cervical cancer deaths would be expected (0.99 × 0.70). This rate does not include loss to follow-up between doses, which could reduce effectiveness further. By contrast, a good VIA program can detect at least 90% of all precancerous cases. With a cure rate of 85% for cryotherapy, a combined program of VIA and cryotherapy would effectively prevent 76% of cervical cancer deaths (0.90 × 0.85). Thus, it should not automatically be assumed that HPV vaccination will be more effective than screening and treatment.

Goldie et al. found that screening women just once in a lifetime at the age of 35 years with VIA or DNA testing was cost-effective and reduced lifetime risk of cervical cancer by 26% to 36% compared with women who received no screening at all.14 Adding a second screening at age 40 years reduced relative cancer risk by an additional 40%, meaning that a total of 66% to 76% of cervical cancer cases could be averted by using this simple method twice in a lifetime.14

It is important to note that although VIA has high sensitivity, the specificity is not as high as other screening methods, and thus there are more false positives. False positives can result in unnecessary anxiety for women as well as unneeded treatment with cryotherapy. Cryotherapy is a safe outpatient procedure that has been used for 40 years to treat precancerous cervical lesions. A systematic review of 38 studies by the Alliance for Cervical Cancer Prevention (ACCP) showed that side-effects of cryotherapy, although reported by fewer than 1% of study participants, included pain, cramping, and pelvic inflammatory disease. The ACCP also reported that the most common negative experiences were pain and cramping during and after cryotherapy, followed by watery discharge; however, these symptoms were brief and acceptable. Considering the low level of risk associated with over treatment, we believe that the benefit of capturing more true positive cases outweighs the risks of potential overtreatment with cryotherapy in a see-and-treat approach using VIA and cryotherapy.

Loss to Follow-Up

A powerful factor affecting the success of vaccination and screening programs is loss to follow-up, which varies considerably by population characteristics, program characteristics, and context. In their cost-effectiveness models, Goldie et al. used the figure of 15% loss to follow-up at each step.14 If this rate is applied to HPV vaccination, even with 100% coverage in the first round, only about 72% of girls would get the third shot of the 3-dose regimen. This rate greatly reduces the potential contribution a vaccination program can make. Similarly, with most screening programs, a positive Pap test leads to 2 more visits for treatment. VIA, by contrast, can be implemented with a 1-visit approach for screening and treatment.

As Table 1 shows, even assuming a sensitivity of only 70% for VIA (range = 50%–96%), with a 1-visit approach, VIA would prevent a higher proportion of cases of cervical cancer than would the HPV vaccine. This model assumes that the vaccine is not protective unless all 3 doses are given, a subject that is now being studied.

TABLE 1.

Estimated Percentage of Cervical Cancer Cases Prevented With Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination and With Visual Inspection With Ascetic Acid (VIA) and Same-Day Cryotherapy

| HPV Vaccine | VIA (1 Visit) and Cryotherapy | |

| Cases of HPV prevented, % | 70 | NA |

| Precancerous lesions detected, % | NA | 70 |

| Precancerous lesions effectively treated,a % | NA | 85 |

| Loss to follow-up,a % | 19 | NA |

| Cervical cancer prevented, % | 51 | 60 |

Note. NA = not applicable.

Using a figure of 15% loss at each of 2 follow-up visits.

Implementation Time Lags

From a humanitarian point of view, perhaps the most troubling aspect of the enthusiasm for HPV vaccination for developing countries is that it accepts that the current level of deaths from cervical cancer will go on for the next 2 decades. Even if implemented fully among all 12-year-old girls tomorrow, vaccination will not save lives for more than 20 years. All women who have already been sexually active will essentially be left to their fate.

The common response to this concern is that pursuing vaccination does not mean abandoning screening. However, in developing countries where adequate screening programs have yet to be implemented, it seems unlikely that governments will be able to develop both screening and vaccination programs in the short or even medium term, despite intentions to do so.

Contacts With Health Care Providers

The recommended number and timing of contacts with health care providers vary greatly for the different prevention, screening, and treatment strategies. Vaccination requires 3 visits, in addition to continued screening visits. It is still not known how long immunity lasts, and whether a booster shot will be needed later in life.

Regarding Pap tests, in the United States the National Cancer Institute recommends that women have their first test at age 21 years, or when they first have sexual intercourse, and after 3 consecutive negative screenings continue to have them at least every 3 years until they turn 65.15 Standards for VIA are not as well developed, but several programs aim to screen women in resource-poor countries once or twice in their lifetimes—at age 35 years and then at 40 years, when persistent HPV infections have begun producing lesions. In middle- and upper-income countries, VIA could be done more often, because cost and access to treatment are less of a problem.

Making screening more evidence-based and cost-effective will increase screening in some groups and decrease it in others. For example, using data from the 2000 National Health Interview Survey in the United States, Sirovich and Welch found that 55% of women with no history of abnormal cytology have a Pap test every year, rather than every 3 years as recommended.16 At the same time, 50% of cervical cancer cases in the United States occur among women who have never been screened, and another 10% occur among women who have not been screened in the past 5 years.17

Modeling done by Russell in the 1990s showed clearly that as the interval between screenings decreased from 3 years to 1 year, there was a diminishing return in terms of cancer prevented.18 Screening every 3 years was estimated to prevent 91% of cases of cervical cancer, whereas screening every 2 years prevented 93% of cases and every 1 year 94% of cases. Increasing testing from every 3 years to every year increased the average number of lifetime tests per woman from 10 to 30 and tripled the cost of a year of life saved.

Program Costs

The cost of HPV vaccines is a commonly cited concern. In the United States, all 3 doses of the Merck vaccine are estimated to cost $360. That cost is far out of reach for most women in developing countries.19 Tiered pricing has recently become available in Mexico, Panama, and South Africa at US $40 per dose. However, in countries with a per capita gross national product of less than US $1000, the vaccine cost per dose may need to be as low as US $1 to be cost-effective.19

Additionally, costs associated with vaccine distribution will need to be analyzed to fully grasp the cost of widespread vaccination programs. The 2 HPV vaccines currently in distribution require refrigeration to remain effective, and because the vaccines are delivered via intramuscular injection, they will usually need to be administered by medical personnel at higher costs than other vaccine programs.

A number of authors have done sophisticated models of cost and effectiveness. They concluded that if immunity wanes and booster vaccinations are needed, and women aged 26 years or younger are vaccinated (the “catch-up” strategy proposed in the United States), then immunization would be less cost-effective than screening alone. They also determined that vaccination was more cost-effective when combined with less frequent, more sensitive screening.20

Effects on the Health System

In many developing countries, health systems are struggling (and often failing) to provide services that have long been considered basic—including immunization against childhood diseases and treatment of common but deadly diseases such as malaria, childbirth complications, and childhood pneumonia. At least in theory, everyone agrees that HPV vaccination must be conducted in conjunction with screening and treatment programs. Consequently, there will be no short-term savings in terms of substituting vaccination for screening and treatment.

Screening for precancerous cervical lesions (using VIA or HPV DNA testing) can be built into existing services, such as family planning and prenatal care. By contrast, distributing the HPV vaccine to young girls in most developing countries would entail an entirely new program because prepubescent girls are not currently the target of any major health initiative. This new program would require devoting not just money but other scarce resources, such as the attention of program planners and managers, staff training, staff time, and transportation resources. These resources are likely to be drawn away from existing programs, whereas introducing VIA screening programs can be done in health centers by midlevel providers (e.g. midwives and nurses) through the strengthening of existing programs and staff. Additionally, by expansion of the coverage and frequency of pelvic examinations, other undiagnosed health complications faced by women may be identified before they become acute.

STRATEGIES FOR DIFFERENT SETTINGS

Before discussing the implications of the information thus far presented, it is important to note that there are some lessons that apply across settings.

Lessons That Apply Across Settings

Focus on screening methods other than the Papanicolaou test.

The Pap test, which was introduced in the 1940s, was largely responsible for the major decreases in rates of cervical cancer morbidity and mortality in developed countries during the last half of the 20th century. That result was achieved despite problems with false positives, false negatives, high costs, loss to follow-up, and incomplete coverage. Both VIA and HPV DNA testing have substantially higher sensitivity than does the Pap test, so screening programs using these methods are less likely to miss precancerous and cancerous lesions. Despite this evidence, VIA is commonly considered a second-best or temporary method, to be used only until countries can mount effective cytological testing programs.

Focus screening on older women.

Persistent HPV infections leading to dysplasia generally take about 10 years to develop; thus, expanded screening should focus on women aged 30 years and older, who are most at risk.

Having a few tests over the course of a lifetime for all women is better than having many tests for most women.

Even in countries with well-established screening programs, there is maldistribution of screening—many women are screened too often, too young, and too old, whereas other women are never or rarely screened. Programs would be much more cost-effective if there was a longer interval between examinations; for example, if women with 3 negative tests were screened only every 3 years (as recommended), rather than annually as is common practice.

Implications for Different Scenarios

A scenario for low-income countries.

For least-developed countries with limited health infrastructure and low screening coverage, the first priority should be to implement a national program of VIA and cryotherapy. This approach is not only low-cost and low-tech, but it will quickly reduce cervical cancer among the millions of women now in their 20s and 30s who will otherwise die over the next 2 decades, as well as those not reached by vaccination. This approach should take priority over starting vaccination campaigns, which will do little to reduce deaths among current cohorts of women of reproductive age. In low-income countries that have strong health infrastructure (as demonstrated by high coverage rates for other vaccines) and have a high percentage of young girls attending schools (where a vaccine program could be implemented), the HPV vaccine may be a sensible second step.

A scenario for middle-income countries.

Although some countries in this category have fairly high effective coverage for screening (e.g., Dominican Republic, 62%; Mexico, 66%; Brazil, 73%), many still have surprisingly low coverage (e.g., India, 6%; Malaysia, 31%; China and South Africa, 23%).2 (Note that “effective coverage” refers to the proportion of 25–64-year-old women in 2002 who had a pelvic examination and a Pap test in the last 3 years.) For all of these countries, the first priority should be to ensure that all women in their 30s and 40s are screened and treated as indicated.

Countries with successful screening programs may want to add an HPV vaccine, contingent on several factors. They will have to negotiate an appropriate purchase cost of the vaccine with the manufacturers to ensure that vaccination will be cost-effective. Health care expenditure per capita is a good indicator of appropriate cost. A cost-effectiveness analysis for Brazil, which had a per capita health expenditure of $755 in 2005,21 concluded that at a cost of $5 per dose (not including program costs), vaccination would have a cost-effectiveness ratio of less than $150 per life year saved, and that in combination with screening 3 times in a woman's lifetime, it would be a cost-effective intervention.19

In addition to cost, distribution mechanisms need to be considered. Will the vaccine be integrated into school programs? How will out-of-school youths be reached? Communications and marketing of the vaccine will be crucial for vaccine success, and this has associated costs. Middle-income countries that are currently using cytological testing would save a considerable amount of money if they switched to VIA. This money could then be used to expand DNA testing or vaccine costs.

A scenario for high-income countries.

Although the risk of a woman dying of cervical cancer has been greatly reduced in developed countries, a substantial number of such deaths still occur. The American Cancer Society estimated that there were 11 070 new cases of invasive cervical cancer and 3870 deaths in the United States in 2008.22 Although the main focus of this article is developing countries, the evidence also has important implications for developed countries.

As in the other scenarios, the first priority in high-income countries must be to expand coverage of screening. As of 2002, effective coverage was 80% to 85% in Austria and Luxembourg; 70% to 79% in Australia, Belgium, France, Germany and Latvia; and only 60% to 69% in Denmark, Finland, Hungary, Italy, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.2 For a few countries, the reported effective coverage is shockingly low—for example, 44% in Ireland and Israel. A great deal of improvement in screening in developed countries is needed for women who are already at risk for cervical cancer.

Furthermore, strategies need to be revised so that they are evidence-based. There should be a serious discussion about retiring the Pap test in favor of more accurate, less costly methods (e.g., HPV DNA tests and VIA) and more sensible schedules—less screening of younger women and more emphasis on women aged 30 years and older, poor women, and minority women. After all, women who have never been screened account for half of the cervical cancer cases in the United States.17 There should also be fewer screenings per woman, especially after a negative HPV DNA test.

Questions remain for vaccination programs. Does it make sense for a high-income country with low incidence of cervical cancer to invest millions of dollars in HPV vaccination that currently covers only strains that produce 70% of cancer cases? How will the vaccine reach those currently unreached by screening and in most need of protection? Is $43 000 a reasonable cost for a year of healthy life saved? Is $120 000 reasonable? These questions need to be answered for particular situations and in light of other ways the funds could be spent.

CONCLUSIONS

The wide publicity related to HPV vaccines, as well as an incomplete understanding of its potential and requirements, has led to a sense of inevitability; often the question is not whether to introduce HPV vaccination, but when and how. At the same time, existing methods of screening (VIA and DNA testing) receive much less attention, although they could save the lives of millions of women before the vaccine can have any effect. We believe that the evidence supports giving priority to improving the coverage, methods, and schedules of screening and treatment programs, and that this applies in countries ranging from the least to the most developed.

In summary, the evidence shows that currently favored strategies (i.e., Pap test, HPV vaccination) are neither optimally protective nor cost-effective in low-income or high-income nations. Instead, policy changes are needed on a global scale to prevent unnecessary deaths from undetected, untreated cervical cancer.

Only after evidence-based screening programs are well in place should countries consider vaccine programs, and then only after considering the cost per year of life saved and competing demands on health funding and systems. Applying these measures will save the lives of millions of women who will develop precancerous lesions during the 20 years that we will have to wait for the vaccine to show results.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Department of International Health, Boston University School of Public Health.

Human Participant Protection

Protocol approval was not required because no human subjects were involved in this research.

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55(2):74–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gakidou E, Nordhagen S, Obermeyer Z. Coverage of cervical cancer screening in 57 countries: low average levels and large inequalities. PLoS Med. 2008;5(6):e132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization, United Nations Population Fund. Preparing for the introduction of HPV vaccines: policy and programme guidance for countries. 2006. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2006/WHO_RHR_06.11_eng.pdf. Accessed May 16, 2011

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Genital HPV infection—fact sheet. November 24, 2009. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv.htm. Accessed May 16, 2011

- 5.Sankaranarayanan R, Nene BM, Shastri SS, et al. HPV screening for cervical cancer in rural India. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1385–1394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sankaranarayanan R. ACCP evidence base: implications for policy and practice. World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2006. Powerpoint presentation. Available at: http://www.alliance-cxca.org. Accessed May 16, 2011

- 7.Perkins R, Langrish S, Stern L, Figueroa J, Simon C. Comparison of visual inspection and Papanicolaou (PAP) smears for cervical cancer screening in Honduras: should PAP smears be abandoned? Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12(9):1018–1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nanda K, McCrory DC, Myers ER, et al. Accuracy of the Papanicolaou test in screening for and follow-up of cervical cytologic abnormalities: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(10):810–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sankaranarayanan R, Wesley R, Thara S, et al. Test characteristics of visual inspection with 4% acetic acid (VIA) and Lugol's iodine (VILI) in cervical cancer screening in Kerala, India. Int J Cancer. 2003;106(3):404–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cervical Cancer Prevention Initiatives at PATH: Two Decades of Progress Toward a World Free of HPV-Related Cancers. Seattle, WA: Program for Appropriate Technology in Health (PATH); 2008. Available at: http://www.rho.org/files/PATH_cxca_rep_to_world.pdf. Accessed May 16, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Patient Education Pamphlet—Gynecologic Problems (AP163): Cancer of the Cervix. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castro W, Gage J, Gaffikin L, et al. Effectiveness, Safety, and Acceptability of Cryotherapy: A Systematic Literature Review. Seattle, WA: Alliance for Cervical Cancer Prevention; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merck & Co. Form 10-K: annual report pursuant to section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2007. February 28, 2008. Available at: http://www.merck.com/finance/proxy/2007_form_10-k.pdf. Accessed May 16, 2011

- 14.Goldie S, Gaffikin L, Goldhaber-Fiebert J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of cervical-cancer screening in five developing countries. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(20):2158–2168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.What You Need to Know About Cervical Cancer. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sirovich B, Welch G. The frequency of Pap smear screening in the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(3):243–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Institutes of Health (NIH) Cervical cancer: NIH Consensus Development Conference Statement, April 1–3, 1996. Available at: http://consensus.nih.gov/1996/1996CervicalCancer102html.htm. Accessed May 16th, 2011

- 18.Russell L. Educated Guesses: Making Policy About Medical Screening Tests. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agosti J, Goldie S. Introducing HPV vaccine in developing countries—key challenges and issues. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(19):1908–1910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim J, Goldie S. Health and economic implications of HPV vaccination in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(8):821–832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization Core health indicators. Available at: http://www.who.int/whosis/database/core/core_select_process.cfm. Accessed May 27, 2010

- 22.American Cancer Society. Detailed guide: cervical cancer: can cervical cancer be prevented? Available at: http://www.cancer.org/cancer/cervicalcancer/detailedguide/cervical-cancer-prevention. Accessed May 16, 2011.