Abstract

Highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) restores CD4+ T-cell numbers in the periphery; however, its efficacy in restoring functional immunity is not fully elucidated. Here we evaluated longitudinal changes in the expression of several key markers of T-cell activation, namely CD40 ligand (CD154), OX40 (CD134), or CD69, after anti-CD3/CD28 activation, as well as levels of IL-12 production after Staphylococcus aureus Cowan stimulation in 28 HIV-infected adult patients. Patients were followed up to 12 mo post-HAART initiation. Viral burdens and CD4 cell counts were measured at the same time points. A control group of 15 HIV-uninfected adult subjects was included for comparison. Significant increases in CD40L and OX40 expression, but not of CD69 expression, were observed over time in the overall patient population, and more particularly in patients with baseline CD4 counts lower than or equal to 200 cells/μL, or those with baseline viral loads lower than or equal to 105 RNA copies/mL. Similar increases were seen for IL-12 production. Viral loads were inversely associated with CD40L expression or IL-12 production in a mixed linear model analysis, while CD4 counts were directly associated. CD40L expression and IL-12 production were significantly correlated. In conclusion, HAART-mediated control of viral replication led to partial restoration of CD40L upregulation/expression, and to increased IL-12 production, but the magnitude of the response depended on the baseline characteristics of the treated patients.

Introduction

The immunological dysfunction associated with HIV infection involves many components of the immune system, including cellular and soluble factors. The hallmark of HIV infection is the marked decline in the number and functional abilities of CD4+ T cells. Previous studies have shown that CD4 counts are a highly predictive prognostic factor for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), with counts ≤200 cells/μL being a major criterion for AIDS (reviewed in 3). Importantly, even the diminished CD4+ T cells still present in HIV-1-infected individuals exhibit functional defects, notably blunted CD40 ligand (CD40L) expression upon T-cell receptor (TCR) stimulation. Those defects become more pronounced with the progression to AIDS (37,38).

CD40L, a member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) super-family, is a major regulator of immunity. This ligand undergoes a tightly regulated inducible expression upon TCR-induced stimulation on the surface of CD4+ T cells (reviewed in 8,14,17). The interaction of this ligand and its receptor, CD40, on antigen-presenting cells (APCs), appears to play a crucial role in the maturation process undergone by APCs. In particular, strong evidence suggests that the interaction of monocytes with activated, CD40L-expressing CD4+ T cells increases the production of IL-12 when they are activated by Staphylococcus aureus Cowan (8).

In HIV-1 infection, CD40L has been shown to have dual functions. On one hand, it is associated with immunological control of viral replication by inducing anti-HIV-1 suppressive immune responses, while on the other hand it leads to increased CD4+ T-cell activation, which promotes the replication of HIV-1 in these lymphocytes (19,20). We and others have demonstrated that HIV-1-mediated blunted CD40L upregulation might play an important role in the suppression of the cell-mediated immune response (7,38). Indeed, we showed in these studies that there is a distinct difference in CD40L expression between HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected individuals (with the latter expressing significantly higher levels of CD40L at both the per CD4+ T-cell level and overall percentage), and that CD40L and IL-12 had a strong correlation. Furthermore, earlier studies in untreated HIV-infected patients have shown severe defects in IL-12 production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) after stimulation by a broad panel of microbial stimuli (reviewed in 8,38). However, the involvement of blunted CD40L in this in vivo defect has not been systematically studied. While previous studies have demonstrated that standard markers of immune activation like HLA-DR and CD38 (12,29), or soluble immune activation markers (12), provide good immune correlates indicating disease stage or effect of HAART initiation, these markers do not necessarily reflect changes in CD4 cell numbers and/or function. Thus given the critical importance of CD40L in both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell activation, it is of immunological interest to elucidate the impact of HAART on such immunological correlates. The objective of the current study was to assess CD40L-induced expression and IL-12 production after HAART initiation, as well as their association with baseline status, as defined as CD4 count and viral load (VL). In addition, the relationships between CD40L-induced expression or IL-12 production with other T-cell activation markers were analyzed.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Heparinized blood samples were obtained from 28 HIV-1-infected adults (University of Cincinnati), with CD4 counts of less than 550 cells/μL and detectable VL (>50 RNA copies/mL), and 15 age-matched HIV-uninfected controls. Patients were further grouped according to baseline CD4 counts (≤200 or >200 cells/μL) or baseline VL (≤100,000 or >100,000 RNA copies/mL). They had no active opportunistic infections or cancer. The patients were either treatment-naïve, had previously-interrupted HAART for at least 6 mo, or were switching from a non-suppressive regimen to another one more likely to result in virologic suppression. The initial sample (“baseline”) was obtained prior to HAART initiation or switch. Blood samples were then obtained from patients at follow-up visits up to 12 mo post-HAART initiation. Adherence to HAART was scaled from poor (1) to excellent (4) based upon compliance with study visits, picking up medication on time, self-reported medication adherence, and HIV viral load measurements demonstrating the expected response to therapy. In addition, blood samples from 15 HIV-uninfected adult individuals were obtained and analyzed as controls. All samples were processed within 3 h of collection. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects according to protocols approved by the institutional review boards of all participating institutions.

Viral loads

Plasma VL was measured by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (Ultrasensitive HIV RT-PCR; Roche, Basel, Switzerland). The threshold of detection was 50 HIV-1 copies/mL.

Cell preparation

PBMCs were separated by density-gradient centrifugation on Ficoll (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ), and cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in complete Roswell Park Memorial Institute culture medium 1640 (RPMI 1640) supplemented with 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM glutamine, and 5 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES, hereafter referred to as C-RPMI; all from Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD). For analysis of T-cell activation markers, PBMCs were first adhered for 1 h at 37°C to remove monocytes. T cells were then purified from the non-adherent cell fraction using T-Qwick (One-Lambda, Los Angeles, CA).

IL-12 production

PBMCs from either HIV-1-infected patients or uninfected controls were either left unstimulated or stimulated immediately after separation from whole blood by Staphylococcus aureus Cowan (0.01% SAC; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), and cultured for 24 h. Production of IL-12 p70 (sensitivity 4 pg/mL; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Undetectable values were assigned an arbitrary value of half the sensitivity limit (i.e., 2 pg/mL).

Expression of T cell activation markers

A total of 5 × 105 T cells were stimulated (or not stimulated, as a control) for 24 h or 48 h with magnetic beads coated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 Ab (T-cell expander®; Dynal, Carlsbad, CA) in duplicate in 96-well plates in complete medium supplemented with 2% human AB+ serum. Preliminary experiments had determined the optimal concentration to be 2.5 μL beads/106 T cells; this concentration was therefore used throughout the study. After incubation, the cells were washed with Fluorescent Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) buffer (PBS, 1% fetal calf serum [FCS], and 0.01% sodium azide), and incubated with human IgG (20 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 10 min at 4°C to block Fc receptor. They were then stained with labeled antibodies (Ab) that recognize CD4, CD40L (CD154), CD69, or OX40 (CD134), or with isotype-matched control Ab (all Ab from BD PharMingen, Mountain View, CA), for 30 min at 4°C. The cells were then washed twice before being fixed in FACS buffer containing 4% paraformaldehyde (30 min minimum at 4°C). Surface expression of the aforementioned activation markers was analyzed on a per cell basis gated on CD4+ T cells using a FACSCalibur and CellQuest software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). A minimum of 50,000 cells (debris and dead cells were gated out using forward-scatter analysis) were analyzed. Results are expressed as the percentage of cells expressing a given marker compared with the isotype staining of such markers.

CD40L mRNA expression

Purified T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 beads or were cultured in medium for 2 h. Total RNA was extracted from purified T cells according to the manufacturer's protocol (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and reverse transcribed using SuperScript reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and random primers (Roche). Reverse transcriptase products were amplified by quantitative real-time PCR (Light-Cycler; Roche), using SYBR green (Roche) and specific primers. Melting curves and electrophoresis established the purity of the amplified bands. A threshold was set in the linear part of the amplification curve. Relative units (RU) were calculated by normalization to CD4 mRNA expression (38).

Statistical analysis

Primary outcome measures were IL-12 production and expression of T-cell activation markers such as CD40L (at both the protein expression and mRNA levels), CD69, and OX40, after 24 h or 48 h of cell stimulation. These outcomes were checked for their central tendency, dispersion, and skewness before performing parametric statistical analyses. Only IL-12 production showed skewed distribution and was therefore log transformed. At baseline, demographic and clinical characteristics of HIV patients were summarized using median (range) and frequency (in %), and compared with healthy participants using Wilcoxon rank sum tests and Fisher's exact tests for numerical and categorical variables, respectively. Baseline outcome variables were assessed for their associations with disease status (HIV versus control), CD4 cell counts in HIV-infected patients (high CD4 counts >200/μL versus CD4 counts ≤200/μL), and VL level (VL >100,000 copies/mL versus VL ≤100,000 copies/mL) using fixed effect models. Means were compared between subgroups of HIV-infected patients and the control group under the fixed effect model framework and adjusting for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni's methods. Similar approaches were used to compare outcome variables from HIV-infected patients at 12 mo after HAART to those of control subjects at baseline. Using mixed-effect models on HIV-infected patients only, we assessed changes of outcome variables from baseline to 12 mo after HAART initiation. A random effect was used in computation to account for within-patient correlations from repeated measurements. In order to assess linear trends of biomarkers in multiple visits during the study period, we applied mixed linear models using the outcome measures as dependent variables, and the continuous time interval (i.e., months from the baseline visit to the current following visit) as the major independent variable of interest. The time interval was also interacted with fixed effects of CD4 cell count and VL level in order to assess the trends of subgroups within the mixed linear model framework. In order to assess relationships between IL-12 production and T-cell activation markers, a multivariate mixed linear model was applied using IL-12 production as the dependent variable, and T-cell activation markers and their interactions with fixed effects of CD4 level and VL level as independent variables. The mixed linear model was used to assess relationships of variables in the longitudinal set-up, instead of the traditional simple linear regression model or the Pearson correlation coefficient, since the latter methods do not account for within-patient variability caused by repeated measurements. In a secondary analysis, we assessed the relationships of CD40L to CD69 and OX40 using the same multivariate mixed linear model by considering CD40L as the dependent variable and CD69 and OX40 as the independent variables of interest. All statistical models were also adjusted for controlling covariates such as demographic characteristics and CD4 cell counts of patients in analyses. All statistical analyses were performed using the SAS 9.2 software package (SAS, Cary, NC). Figures were plotted using SPLUS 7.0 software (Insightful Corp., Seattle, WA), and p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

Twenty-eight adult HIV-1-infected patients with no active opportunistic infection (median age: 38 y, range: 24–59 y) were recruited. Demographic information of the patients and those of the age-matched control adults is summarized in Table 1. At baseline, the patients' median peripheral CD4 count was 252 cells/μL (range: 13–512 cells/μL), and the median VL was 54,200 RNA copies/mL (range: 3900–1,582,300 copies/mL). Of the 28 patients, 15 (53.6%) had CD4 counts >200 cells/μL, while 7 (25%) had VL >100,000 copies/mL. Thirteen (46.4%) were treatment-naïve. The patients then started a combination of various antiretroviral therapies as summarized in Table 1. Treatment adherence was good, with 86.4% of patients presenting with an adherence score of 4, on a 1–4 scale (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Variable | Category | HIV-infected (n = 28)a | Control (n = 15)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age | 38 (24–59) | 30 (22–46) | |

| Gender | Male | 92.6%b | 60.0% |

| Race | White | 66.7%b | 93.3% |

| Clinical information | |||

| CD4 counts (cells/μL) | All patients | 252 (13–512) | |

| CD4 >200 | 53.6%c | ||

| VL (×103 copies/mL) | All patients | 54.2 (3.9–15,582) | |

| VL >100,000 | 25.0%c | ||

| Number of visits | 4 (2–6) | ||

| Inter-visits (month) | 4 (1–12) | ||

| Monocyte counts (cells/μL) | 400 (200–800) | ||

| ARVd | Number of ARV prescribed | 4 (2–4) | |

| Type of ARVe | Efavirenz | 57.1% | |

| Tdf | 46.4% | ||

| Kaletra | 32.1% | ||

| 3TC | 28.6% | ||

| Combivir | 25.0% | ||

| atv | 7.1% | ||

| d4T | 3.6% | ||

| Fos-apv | 3.6% | ||

| T20 | 3.6% | ||

| Ddl | 3.6% | ||

| nvp | 3.6% | ||

| Adherence score = 4f | 86.4% | ||

Values are expressed in median (range) or frequency (%) for numerical values and categorical values respectively.

Indicates a significant difference between the HIV-infected and control groups (p < 0.05).

Indicates the proportion of enrolled patients with the described characteristic.

List of antiretrovirals (ARV) prescribed.

Percentage of patients prescribed any of the following ARV: Tdf, tenofovir; 3TC, lamivudine; d4T, stavudine; atv, atazanavir; Fos-apv, fos-amprenavir; T20, enfuvertide; ddi, didanosine; nvp, nevirapine.

Initiation of HAART in HIV-1-infected patients restored CD4 cell counts and decreased viral load

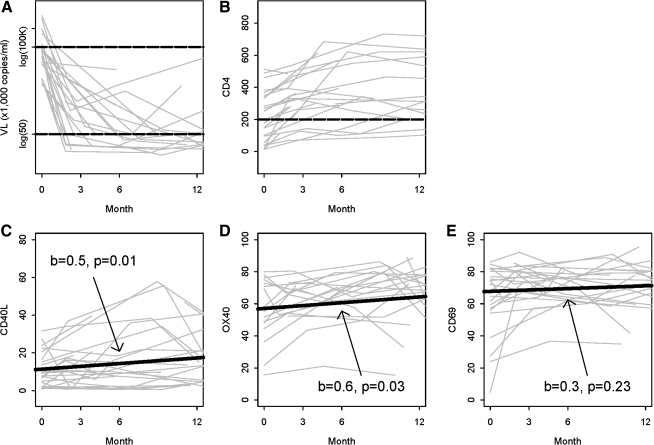

We measured the plasma VL and peripheral CD4+ T-cell counts in longitudinal samples following HAART initiation. As shown in Fig. 1A, plasma VL dramatically decreased over time during the follow-up visits compared to baseline. This decrease continued through 12 mo, at which point all patients except 1 had VL <50 copies/mL. CD4 counts significantly increased (Fig. 1B) in the overall patient population. Patients with low baseline CD4 counts (≤200 cells/μL) demonstrated a fourfold increase in median CD4 count by 3 mo. Though less pronounced, peripheral CD4 counts also increased in patients with high baseline CD4 counts (p = 0.02). By the end of the study, at 12 mo, CD4 counts were >200 cells/μL in all but 1 patient (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Induction of T-cell activation markers increased following antiretroviral therapy. Changes in viral loads (A), CD4 counts (B), induced CD40L expression (C), induced CD69 expression (D), and induced OX40 expression (E) in all patients at baseline, 3 mo, 6 mo, and 12 months of HAART initiation. Slope (b) and significance (p) are shown for each analysis. T-cell activation markers (CD40L, CD69, and OX40) were measured by surface flow cytometry analysis after 24 h of TCR-induced T-cell stimulation using anti-CD3/28 coated beads. Results were expressed as percentages of CD4+ T cells expressing each T-cell activation marker.

HAART initiation led to increased expression of CD40L and other T-cell activation markers

In view of the critical role of CD40L in cell-mediated immunity, we measured expression of inducible CD40L in CD4+ T cells, at both the protein and mRNA levels. In addition, we measured the expression of two other T-cell activation markers, OX40 and CD69. At baseline, expression of these three markers was significantly lower in CD4+ T cells obtained from HIV-infected patients after 24 h of activation compared to that seen in T cells from uninfected controls (all p < 0.05, Table 2). Similar trends were seen after 48 h of stimulation (data not shown). Inducible CD40L and CD69, but not OX40, expression was significantly higher at baseline in patients with high CD4 cell counts compared to those with low CD4 cell counts (Table 2). There was no difference in the baseline percentage of CD4+ T cells expressing inducible CD40L, CD69, or OX40 in patients stratified according to their baseline VL (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline CD40L-mRNA Upregulation, Surface CD40L, CD69, and OX40 Expression, and IL-12 Production in HIV-Infected Patients and Uninfected Controls

| Category | CD40La | CD69a | OX40a | CD40L-mRNAd | IL-12e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 15) | 21.0 (2.0) | 86.6 (1.4) | 70.8 (2.4) | 2.31 ± 0.18 | 4.7 (0.1) |

| All HIV+ patients (n = 28) | 10.2 (1.7)bb | 64.6 (4.4)bb | 54.5 (4.6)bb | 0.93 ± 0.14bb | 1.9 (0.1)bb |

| CD4 >200 (n = 15) | 14.6 (2.1)b | 71.6 (2.8)b | 61.1 (3.8) | 1.23 ± 0.18bb | 2.2 (0.2)bb |

| CD4 ≤200 (n = 13) | 3.2 (0.9)bb,cc | 50.3 (9.3)bb,cc | 45.3 (8.8)bb,c | 0.58 ± 0.18bb,c | 1.6 (0.1)bb,cc |

| VL ≤100,000 (n = 21) | 10.4 (2.1)bb | 66.1 (4.7)bb | 57.8 (4.6) | 0.97 ± 0.14bb | 1.9 (0.2)bb |

| VL >100,000 (n = 7) | 9.7 (3.1)bb | 53.0 (11.5)bb | 45.1 (11.5)bb | 0.79 ± 0.38bb | 1.8 (0.3)bb |

| 12 months post-HAART initiation | |||||

| All HIV+ (n = 25) | 21.3 (3.6)ff | 73.5 (2.9)bb | 67.8 (3.9)f | 1.6 (0.1)bb,ff | 3.2 (0.3)bb,ff |

| CD4 >200 (n = 12) | 24.4 (5.4) | 73.8 (4.1)b | 65.3 (5.1) | 2.0 (0.2)f | 3.8 (0.4)b,ff |

| CD4 ≤200 (n = 13) | 18.4 (4.8)f | 73.3 (4.2)bb,f | 70.2 (6.0)f | 1.3 (0.2)bb,c,ff | 2.7 (0.3)bb,c,ff |

| VL ≤100,000 (n = 18) | 20.1 (3.5)f | 72.9 (3.1)bb | 68.6 (4.2) | 1.6 (0.1)bb,ff | 3.2 (0.3)bb,ff |

| VL >100000 (n = 7) | 24.4 (9.5) | 75.0 (7.1) | 65.7 (9.3) | 1.7 (0.3)ff | 3.2 (0.7) |

The percentage of CD4+ T cells expressing each marker was measured by flow cytometry after stimulation of T cells with anti-TCR for 24 h.

and bbindicate that the mean is significantly lower from that of the control group with p values < 0.05 and 0.01, respectively.

and ccindicate that the mean is significantly lower from that of the CD4 >200 group with p values <0.05 and 0.01, respectively.

Values were log transformed.

Values were log-transformed (SE) levels (expressed in pg/mL) of IL-12 p70 measured in supernatants of PBMCs stimulated with SAC for 24 h. CD4 counts are expressed in cells/μL.

or ffindicate that the mean at 12 months after HAART initiation is significantly higher than that at baseline, with p values <0.05 and 0.01 respectively.

HAART, highly active anti-retroviral therapy; VL, viral load; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; SAC, Staphylococcus aureus Cowan.

Expression of the three activation markers was determined at follow-up visits post-HAART initiation. Upward trends were found in both CD40L and OX40 after treatment in all patients (slope = 0.5, p = 0.02, and slope = 0.7, p = 0.02, respectively; Fig. 1C and D). The trends for CD40L at mRNA levels were similar to those at the protein expression levels (data not shown). In contrast, there was no significant increase in CD69 expression (slope = 0.3, p = 0.18, Fig. 1E). These data are further confirmed in Table 2; both CD40L and OX40 showed significant increases in their mean values at 12 months after HAART initiation, compared to baseline values (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectively). Mean expression of CD40L and OX40 reached comparable levels to those of the normal controls (p = 0.960 and p = 0.608, respectively). Trends for CD40L mRNA levels were comparable to those of protein expression levels as shown in the table. Similar trends were seen, although not significant, at 48 h of stimulation (data not shown).

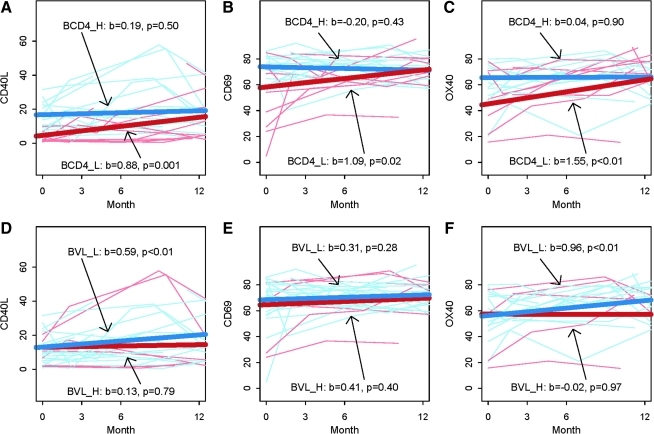

To examine the effects of baseline CD4 cell counts or VL on induction of CD40L, OX40, or CD69 following HAART initiation, data were subjected to multivariate ANOVA models. Expression of CD40L, OX40, and CD69 on CD4+ T cells were all significantly increased post-HAART initiation in patients with low baseline CD4 counts (red lines in Fig. 2A, B, and C), whereas they did not increase in patients with initially high CD4 counts (blue lines in Fig. 2A, B, and C). Patients with low baseline VL exhibited significant increases of CD40L and OX40 expression, but not of CD69 (blue lines in Fig. 2D, E, and F). In contrast, no significant changes in these markers were observed in patients with high initial VL (red lines in Fig. 2 D, E, and F), which could be due to the small number of these patients included in our study. One limitation of our study is that cells were analyzed right away, thus precluding us from analyzing HAART-associated changes in the expression per cell of CD40L, OX40, or CD69. However, collectively our data suggest that CD4 count correction and decreased VL following HAART ameliorated the capacity of CD4+ T cells to respond to TCR stimulation, but that amelioration was more striking when baseline CD4 dysregulation was more pronounced.

FIG. 2.

HAART-induced increases in T-cell activation makers vary depending on patient baseline CD4 counts or viral loads. CD40L, OX40, and CD69 expression for each patient are shown at various time points following HAART initiation. Slope (b) and significance (p) are shown for each analysis. Results are shown as percentages of CD4+ T cells expressing each marker. Top panels (A, B, and C) show stratification according to baseline CD4 counts. Plots show variation in CD40L (A), CD69 (B), and OX40 (C) expression, when HIV patients were stratified according to baseline CD4 counts. CD4_H (blue lines) signifies high baseline CD4 counts (>200/μL), and CD4_L (red lines) signifies low baseline CD4 counts (≤200/μL). Bottom panels (D, E, and F) show stratification according to baseline VL. Similar plots show variations in CD40L (D), CD69 (E), and OX40 (F) expression when HIV patients were stratified according to baseline VL. VL_L (blue lines) signifies low baseline VL (<100,000 copies/mL), and VL_H (red lines) signifies high baseline VL (≥100,000 copies/mL). Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/vim

CD40L mRNA followed similar trends as those exhibited by CD40L protein expression. At baseline, HIV-infected patients had significantly lower levels of induced CD40L mRNA than the HIV-uninfected controls (Student's t-test, log-transformed values, p < 0.01, Table 2). Baseline CD40L mRNA positively correlated with CD4 cell counts, while it was inversely correlated with HIV-1 VL (both p < 0.01). Treatment was accompanied by a steady increase in the levels of induced CD40L mRNA (slope = 0.04, p = 0.002; data not shown). Similarly to what we observed with protein levels, mRNA CD40L expression increased by threefold at 12 mo over baseline levels in patients with low baseline CD4 counts (slope = 0.05, p = 0.002). In patients with high baseline CD4 counts, CD40L mRNA expression increased 1.5-fold at 12 mo over baseline levels (slope = 0.03, p = 0.16; data not shown), confirming our previous findings that the majority of the defects affecting CD40L expression in HIV infection are either at the transcriptional level, or in the signaling cascades leading to CD40L upregulation (38).

HAART initiation increased IL-12 production

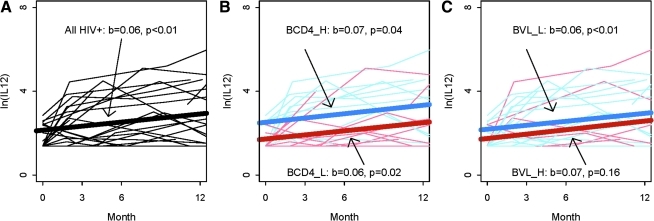

We have previously shown that addition of exogenous CD40L increased IL-12 production by PBMCs obtained from HIV-1-infected persons following SAC stimulation (38). Thus, we hypothesized that the HAART-mediated increase in CD40L expression would lead to increased IL-12 production. In agreement with our previous studies, IL-12 production was low in all HIV-infected patients at baseline compared to uninfected controls, and was particularly low in patients with low baseline CD4 counts (Table 2).

Following HAART initiation, IL-12 production increased significantly over time (slope = 0.06, p < 0.01), as shown in Fig. 3A. The IL-12 production level in cells from HIV+ patients at 12 mo after HAART initiation was increased by 5.7-fold from its baseline level (p < 0.001, Table 2), although it still remained significantly lower than in the controls. This trend was maintained when patients were stratified according to their baseline CD4 counts. Patients with either low or high baseline CD4 counts both exhibited a significant increase in IL-12 production (slope = 0.06, p = 0.02, and slope = 0.07, p = 0.04, respectively; red and blue lines, respectively, in Fig. 3B). Similar improvement over time was seen in patients with low baseline VL (blue line in Fig. 3C). Absolute numbers of monocytes, which are the main PBMCs that produce IL-12, did not change after HAART (data not shown), suggesting that the increased IL-12 production over time is more likely a reflection of functional improvement rather than of a numeric change.

FIG. 3.

IL-12 production increases in HAART-treated patients. IL-12 production was measured in supernatants of 24-h SAC-stimulated PBMCs. Log transformed levels are shown for each patient. Slope (b) and significance (p) are shown for each analysis. (A) Overall population. (B) Stratification according to baseline CD4 counts. CD4_H (blue lines) signifies high baseline CD4 counts (>200/μL). CD4_L (red lines) signifies low baseline CD4 counts (≤200/μL). (C) Stratification according to baseline VL. VL_L (blue lines) signifies low baseline VL (<100,000 copies/mL). VL_H (red lines) signifies high baseline VL (≥100,000 copies/mL). Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/vim

Further analysis revealed that IL-12 production and CD40L expression were positively correlated, with or without stratification of patients' baseline CD4 counts or viral load (p < 0.01), whereas IL-12 production did not correlate with the expression of the other activation markers, OX40 or CD69, as summarized in Table 3. Like CD40L, IL-12 production was positively correlated with CD4 cell counts, while it was inversely correlated with viral load (p < 0.001). Similar trends were observed for CD40L at mRNA levels as shown in the table.

Table 3.

Correlation Between IL-12 Production or CD40L Expression and Other Markers of T-Cell Activation or CD4 Counts

| Dependent variable | Independent variable | All HIV-infecteda(n = 28) | High baseline CD4a(n = 16) | Low baseline CD4a(n = 12) | Low baseline viral load (n = 21) | High baseline viral load (n = 7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log (IL-12) | ||||||

| CD40L | 0.06 (0.02)bb | 0.07 (0.02)bb | 0.045 (0.02)b | 0.04 (0.01)bb | 0.08 (0.03)bb | |

| CD69 | 0.07 (0.04) | 0.06 (0.04) | 0.09 (0.04) | −0.01 (0.01) | 0.15 (0.08) | |

| OX40 | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.01 (0.04) | 0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.07) | |

| CD4 | 0.39 (0.53) | −0.14 (0.53) | 0.93 (0.69) | 0.67 (0.31)b | 0.11 (0.95) | |

| CD40L (mRNA)d | 0.90 (0.17)bb | 1.6 (0.26)bb | 0.56 (0.24)b | 0.84 (0.22)bb | 1.01 (0.28)bb | |

| CD40L | ||||||

| CD69 | −.60 (0.38) | −.76 (0.41) | −.44 (0.42)bb | 0.02 (0.16)bb | −.22 (0.74)bb | |

| OX40 | 0.87 (0.32)bb | 0.86 (0.39)bb | 0.89 (0.32)bb | 0.29 (0.16)bb | 1.45 (0.61)bb | |

| CD4 c | 6.85 (4.72) | 7.43 (4.45) | 6.27 (7.05)b | 2.94 (3.57)b | 10.75 (7.66)b | |

| CD40L (mRNA)d | 6.07 (1.7)bb | 3.82 (2.52) | 7.83 (2.38)b | 5.11 (2.00)b | 8.19 (3.46)b | |

Values represent mean (SE) of slope coefficient.

Indicate significant positive relationship or positive slope between the dependent variable and the independent variable with p values <0.05 and 0.01, respectively.

Correlation with log CD4 counts was tested.

Log transformed values.

Discussion

We and others have demonstrated that blunted CD40L expression in CD4+ T cells from HIV-1-infected individuals could lead to defective production of IL-12 by APCs from infected subjects (10,34,37,38). Thus we hypothesized that the drastic reduction in viral load and partial restoration of CD4 counts seen following HAART could lead to the restoration of CD40L expression, and as a likely consequence, to increased production of IL-12.

The downregulation of TCR-induced CD40L expression on CD4+ T cells decreases with time in parallel with other markers of suppression of cell-mediated immunity in HIV-1 infection (34,37). CD40L induction by pathogens is also impaired in HIV-infected patients (33). Our previous data demonstrated that engagement of CD4 receptor by HIV-1 gp120 envelope glycoprotein (or by HIV-1 virions themselves) prior to T-cell activation models the dysregulation of CD40L upregulation, which is apparent in HIV-infected donors (38,39). Consistent with these data, the present study revealed that viral suppression following HAART led to amelioration of TCR-induced CD40L expression by CD4+ T cells. Furthermore, the increased expression was positively associated with CD4 cell counts and inversely associated with VL. While the effects are mostly inter-related, these data suggest that both the VL and CD4 counts have a direct effect on blunted CD40L-induced expression. HAART also led to amelioration of OX40 induction, but not of CD69 expression. CD40L and OX40 both belong to the TNF super-family, and their induction by TCR stimulation is enhanced by CD28 co-stimulation (15,37). CD28 expression on CD4+ T cells is diminished in HIV infection, but increases following antiretroviral therapy (2,21,35), which may have contributed to the increases in CD40L and OX40 expression observed in this study. Induction after TCR engagement of these molecules is differently regulated in comparison to that of CD69 (11,24,36), a feature that suggests that HAART might not restore different signaling cascades to the same extent. Only a few studies have analyzed T-cell signaling cascades after HAART (28,30), and future studies will be needed to clarify that point. An alternative explanation is that CD69 expression was not as severely affected in T cells from untreated HIV-uninfected patients as CD40L, and there were therefore fewer margins for improvement.

When we stratified patients according to baseline CD4 counts, an interesting trend emerged. Patients with low baseline CD4 counts exhibited a significant increase in CD40L, OX40, or CD69 expression following HAART. In contrast, patients with low CD4 nadirs were previously shown to exhibit a lesser HAART-mediated reconstitution of antigen-specific T-cell responses, as evidenced by low levels of reconstitution of DTH responses and in vitro proliferation, compared with patients with less advanced disease (22,23). Consistent with our observations here, those data suggest that successful HAART may ameliorate the intrinsic reactivity of CD4+ T cells to TCR stimulation, but that HAART does not restore the losses in the immunological repertoire that had occurred during HIV disease progression. In contrast to the results obtained with CD4 counts, a high baseline VL did not predict the subsequent restoration of activation marker expression. However, this result might be due to the very small number of patients with such high VL at baseline, and would thus require further studies.

While there is a general consensus on increased levels in serum IL-12 during the early stages of HIV-1 infection (4,6,27), in vitro stimulation of PBMCs from HIV-infected patients with a wide range of stimuli led to a reduced production of IL-12, although results vary with both the nature of the stimuli and the disease stage (18,25). Studies of the effect of HAART on correcting anomalies in IL-12 production have yielded discrepant results, showing either an amelioration post-HAART (5,26), or an absence of significant improvement (1,9). Our present study shows that viral reduction and/or CD4 restoration resulting from HAART was accompanied by increased IL-12 production. Differences in the results coming from these independent studies could come from differences in the studied populations (notably children versus adults, and proportion of patients with advanced disease), as well as in the level of virological and immunological restoration. Indeed, in the present study HAART was successful, with all patients except one exhibiting undetectable VL at 12 mo, in contrast to our previous studies (1,9).

We also found a strong correlation between induced CD40L expression and IL-12, but not between induced OX40 and CD69, and IL-12 production. We have previously shown that CD40L signaling is a critical element for IL-12 induction (10). Similarly, a recent study demonstrated that signaling through CD40 could restore IL-12 secretion in dendritic cells that had exhausted their potential for cytokine production, further underscoring the importance of CD40L in IL-12 production (13). Our present ex vivo data confirm our in vitro mechanistic observations, directly incriminating blunted CD40L in the decreased production of IL-12 observed in chronically HIV-infected patients (39). However, we cannot exclude the possible direct impact of the increased number in CD4+ T cells (albeit this was adjusted for during the analysis) seen during this study. Alternatively, other T-cell signaling pathways, including IFN-γ-mediated, may be involved in IL-12 production (16,31,32). As IL-12 production and inducible CD40L were correlated with CD4 counts, the most commonly used surrogate immunological marker of HAART efficiency, our data suggest that the follow-up of these functional markers could be of use in clinical studies.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI056927 and AI068524 to C.C., and AI069513 to C.J.F.). We thank Dr. Gene Shearer for his review of the manuscript. The authors also thank all study participants, Diane Daria for help with recruitment and follow-up of patients, and Rui Zhang for her expert assistance.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Angel JB. Kumar A. Parato K, et al. Improvement in cell-mediated immune function during potent anti-human immunodeficiency virus therapy with ritonavir plus saquinavir. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:898–904. doi: 10.1086/515244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angel JB. Parato KG. Kumar A, et al. Progressive human immunodeficiency virus-specific immune recovery with prolonged viral suppression. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:546–554. doi: 10.1086/318547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Battegay M. Nuesch R. Hirschel B. Kaufmann GR. Immunological recovery and antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1 infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:280–287. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70463-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bebell LM. Passmore JA. Williamson C, et al. Relationship between levels of inflammatory cytokines in the genital tract and CD4+ cell counts in women with acute HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:710–714. doi: 10.1086/590503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bocchino M. Ledru E. Debord T. Gougeon ML. Increased priming for interleukin-12 and tumour necrosis factor alpha in CD64 monocytes in HIV infection: modulation by cytokines and therapy. AIDS. 2001;15:1213–1223. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200107060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrnes AA. Harris DM. Atabani SF. Sabundayo BP. Langan SJ. Margolick JB. Karp CL. Immune activation and IL-12 production during acute/early HIV infection in the absence and presence of highly active, antiretroviral therapy. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:1447–1453. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0708438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chirmule N. McCloskey TW. Hu R. Kalyanaraman VS. Pahwa S. HIV gp120 inhibits T cell activation by interfering with expression of costimulatory molecules CD40 ligand and CD80 (B71) J Immunol. 1995;155:917–924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chougnet C. Role of CD40 ligand dysregulation in HIV-associated dysfunction of antigen-presenting cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:702–709. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0403171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chougnet C. Jankelevich S. Fowke K, et al. Long-term protease inhibitor-containing therapy results in limited improvement in T cell function but not restoration of interleukin-12 production in pediatric patients with AIDS. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:201–205. doi: 10.1086/322006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chougnet C. Thomas E. Landay AL. Kessler HA. Buchbinder S. Scheer S. Shearer GM. CD40 ligand and IFN-gamma synergistically restore IL-12 production in HIV-infected patients. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:646–656. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199802)28:02<646::AID-IMMU646>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Ambrosio D. Cantrell DA. Frati L. Santoni A. Testi R. Involvement of p21ras activation in T cell CD69 expression. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:616–620. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D'Amico R. Yang Y. Mildvan D, et al. Lower CD4+ T lymphocyte nadirs may indicate limited immune reconstitution in HIV-1 infected individuals on potent antiretroviral therapy: analysis of immunophenotypic marker results of AACTG 5067. J Clin Immunol. 2005;25:106–115. doi: 10.1007/s10875-005-2816-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dohnal AM. Luger R. Paul P. Fuchs D. Felzmann T. CD40 ligation restores type 1 polarizing capacity in TLR4-activated dendritic cells that have ceased interleukin-12 expression. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:1741–1750. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00584.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donaghy H. Stebbing J. Patterson S. Antigen presentation and the role of dendritic cells in HIV. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2004;17:1–6. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200402000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dybul M. Mercier G. Belson M, et al. CD40 ligand trimer and IL-12 enhance peripheral blood mononuclear cells and CD4+ T cell proliferation and production of IFN-gamma in response to p24 antigen in HIV-infected individuals: potential contribution of anergy to HIV-specific unresponsiveness. J Immunol. 2000;165:1685–1691. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frasca L. Nasso M. Spensieri F. Fedele G. Palazzo R. Malavasi F. Ausiello CM. IFN-gamma arms human dendritic cells to perform multiple effector functions. J Immunol. 2008;180:1471–1481. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grewal IS. Flavell RA. CD40 and CD154 in cell-mediated immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:111–135. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harrison TS. Levitz SM. Role of IL-12 in peripheral blood mononuclear cell responses to fungi in persons with and without HIV infection. J Immunol. 1996;156:4492–4497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kornbluth RS. The emerging role of CD40 ligand in HIV infection. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;68:373–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kornbluth RS. An expanding role for CD40L and other tumor necrosis factor superfamily ligands in HIV infection. J Hematother Stem Cell Res. 2002;11:787–801. doi: 10.1089/152581602760404595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lange CG. Lederman MM. Medvik K. Asaad R. Wild M. Kalayjian R. Valdez H. Nadir CD4+ T-cell count and numbers of CD28+ CD4+ T-cells predict functional responses to immunizations in chronic HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 2003;17:2015–2023. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200309260-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lange CG. Valdez H. Medvik K. Asaad R. Lederman MM. CD4+ T-lymphocyte nadir and the effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on phenotypic and functional immune restoration in HIV-1 infection. Clin Immunol. 2002;102:154–161. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lederman HM. Williams PL. Wu JW, et al. Incomplete immune reconstitution after initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with severe CD4+ cell depletion. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:1794–1803. doi: 10.1086/379900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsumura Y. Hori T. Kawamata S. Imura A. Uchiyama T. Intracellular signaling of gp34, the OX40 ligand: induction of c-jun and c-fos mRNA expression through gp34 upon binding of its receptor, OX40. J Immunol. 1999;163:3007–3011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyaard L. Hovenkamp E. Pakker N. van der Pouw Kraan TC. Miedema F. Interleukin-12 (IL-12) production in whole blood cultures from human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals studied in relation to IL-10 and prostaglandin E2 production. Blood. 1997;89:570–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monari C. Casadevall A. Baldelli F. Francisci D. Pietrella D. Bistoni F. Vecchiarelli A. Normalization of anti-cryptococcal activity and interleukin-12 production after highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2000;14:2699–2708. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200012010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nilsson J. Kinloch-de-Loes S. Granath A. Sonnerborg A. Goh LE. Andersson J. Early immune activation in gut-associated and peripheral lymphoid tissue during acute HIV infection. AIDS. 2007;21:565–574. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280117204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nyakeriga AM. Fichtenbaum CJ. Goebel J. Nicolaou SA. Conforti L. Chougnet CA. Engagement of the CD4 receptor affects the redistribution of Lck to the immunological synapse in primary T cells: implications for T-cell activation during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 2009;83:1193–1200. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01023-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenblatt HM. Stanley KE. Song LY. Johnson GM. Wiznia AA. Nachman SA. Krogstad PA. Immunological response to highly active antiretroviral therapy in children with clinically stable HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:445–455. doi: 10.1086/431597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schweneker M. Favre D. Martin JN. Deeks SG. McCune JM. HIV-induced changes in T cell signaling pathways. J Immunol. 2008;180:6490–6500. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.10.6490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Snijders A. Hilkens CM. van der Pouw Kraan TC. Engel M. Aarden LA. Kapsenberg ML. Regulation of bioactive IL-12 production in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human monocytes is determined by the expression of the p35 subunit. J Immunol. 1996;156:1207–1212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Snijders A. Kalinski P. Hilkens CM. Kapsenberg ML. High-level IL-12 production by human dendritic cells requires two signals. Int Immunol. 1998;10:1593–1598. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.11.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Subauste CS. Wessendarp M. Portilllo JA, et al. Pathogen-specific induction of CD154 is impaired in CD4+ T cells from human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:61–70. doi: 10.1086/380510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Subauste CS. Wessendarp M. Smulian AG. Frame PT. Role of CD40 ligand signaling in defective type 1 cytokine response in human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:1722–1731. doi: 10.1086/320734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valdez H. Connick E. Smith KY, et al. Limited immune restoration after 3 years' suppression of HIV-1 replication in patients with moderately advanced disease. AIDS. 2002;16:1859–1866. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200209270-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Kooten TG. Klein CL. Kirkpatrick CJ. Cell-cycle control in cell-biomaterial interactions: expression of p53 and Ki67 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells in direct contact and extract testing of biomaterials. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;52:199–209. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200010)52:1<199::aid-jbm26>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vanham G. Penne L. Devalck J, et al. Decreased CD40 ligand induction in CD4 T cells and dysregulated IL-12 production during HIV infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;117:335–342. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00987.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang R. Fichtenbaum CJ. Hildeman DA. Lifson JD. Chougnet C. CD40 ligand dysregulation in HIV infection: HIV glycoprotein 120 inhibits signaling cascades upstream of CD40 ligand transcription. J Immunol. 2004;172:2678–2686. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang R. Lifson JD. Chougnet C. Failure of HIV-exposed CD4+ T cells to activate dendritic cells is reversed by restoration of CD40/CD154 interactions. Blood. 2006;107:1989–1995. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]