1. Introduction

Organocatalysis has captured the imagination of a significant group of synthetic chemists. Much of the mechanistic understanding of these reactions has come from computational investigations or studies involving both experimental and complementary computational explorations. As much as any other area of chemistry, organocatalysis has advanced because of both empirical discoveries and computational insights. Quantum mechanical calculations, particularly with density functional theory (DFT), can now be applied to real chemical systems that are studied by experimentalists; this review describes the quantum mechanical studies of organocatalysis.

The dramatic growth of computational investigations on organocatalysis in the last decade reflects the great attention focused on this area of chemistry since the discoveries of List, Lerner, and Barbas of the proline-catalyzed intermolecular aldol reaction, and by MacMillan in the area of catalysis by chiral amino-acid derived amines. The number of reports on the successful applications of organocatalysts and related mechanistic investigations for understanding the origins of catalysis and selectivities keep growing at a breathtaking pace. Literature coverage in this review is until October 2009, except for very recent discoveries that alter significantly the conclusions based on older literature.

1.1 Computational methods for organocatalysis

Over the last two decades, DFT has become a method of choice for the cost-effective treatment of large chemical systems with high accuracy.1 Most of the studies reported in this review were carried out using the B3LYP functional with the 6-31G(d) basis set, which is a standard in quantum mechanical calculations. Nevertheless, DFT is experiencing continuing developments of new functionals and further improvements. The availability of many new functionals and, in particular, the rapidly evolving performance issues of B3LYP have stimulated extra efforts on benchmarking DFT methods for the prediction of key classes of organic reactions.2 The well-documented deficiencies of B3LYP include the failure to adequately describe medium-range correlation and photobranching effects,3,4 delocalization errors causing significant deviations in π→σ transformations,2b,5 and incorrect description of non-bonding and long-range interactions,6 which are likely to be key factors in determining stereoselectivities. Benchmark results also show that newer functionals considerably improve some of the underlying issues.2–7 Recent advances, especially in the treatment of dispersion effects, now offer more reliable models of the reaction profiles and stereoselectivities.

Most benchmarks focus on energetics rather than stereoselectivities. Systematic benchmarking for stereoselectivities requires more sophisticated techniques and averaging over conformations. To date, such benchmarking based upon stereoselectivity is available for only three reactions,8 and even there only various basis sets with B3LYP, as well as comparisons of results predicted using enthalpies and free energies. It is not possible to assign error bars for stereoselectivities for the majority of reports discussed in this review. Because stereoisomeric transition structures are very similar species, their relative energies are likely to be calculated accurately, as shown by the good agreement between calculated and experimental values.

More recently Harvey (Harvey, 2010, faraday discussions) has studied two typical organic reactions of polar species (Wittig and Morita-Baylis-Hillman reactions) at different levels of theory.2i He showed that many standard computational methods, involving B3LYP, are qualitatively useful, but the energetics may be misleading for larger reactive partners; the quantitative prediction of rate constants remains difficult. These studies suggest that although B3LYP provides valuable qualitative insight into the reaction mechanisms and selectivities, the energetics may require testing with higher accuracy methods for complex organic systems. On the other hand, Simón and Goodman found B3LYP to be “only slightly less accurate” than newer methods, and recommended its use for organic reaction mechanisms.9

2. Enamine/Iminium Catalysis

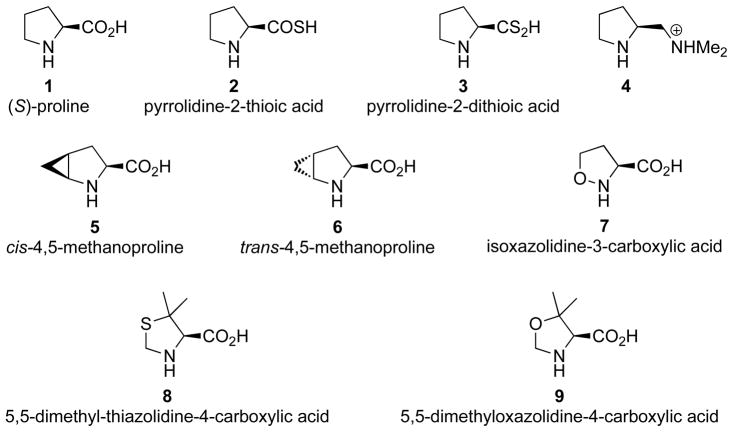

2.1. Proline and proline derivatives

2.1.1. Intramolecular aldol reaction

The Hajos-Parrish reaction is sometimes considered to be the first organocatalytic enantioselective transformation to be reported (1971). Two groups, Hajos and Parrish at Hoffmann La Roche10 and Eder, Sauer, and Wiechert at Schering AG,11 published a series of papers and patents involving these transformations. This discovery made possible the stereoselective synthesis of enediones like the so-called Wieland-Miescher ketone, which are key structural elements of steroids, terpenoid, and taxol. It also paved the way to the growing phenomenon of organocatalysis. List has reviewed the field recently12 and MacMillan has described his influence on creating the field of organocatalysis.13

2.1.1.1. Mechanism of Hajos-Parrish reaction

Four main mechanisms of the C-C bond-forming step have been proposed (Scheme 1). There were two original proposals set forth by Hajos and Parrish. The first is the nucleophilic attack by the exocyclic enol ether to a carbinolamine to displace the catalyst (Mechanism A). The second is a simultaneous proton transfer and nucleophilic attack by an enaminium, assisted by the carboxylate (Mechanism B). Based on the observation of a small non-linear effect, Agami suggested that second molecule of proline may be involved in the proton transfer process from the carboxylic acid (Mechanism C).14 Finally, a mechanism originally proposed by Jung in 1976 suggested a nucleophilic attack of the enamine terminus with simultaneous proton transfer to the developing alkoxide involving a single molecule of proline catalyst (Mechanism D).15

Scheme 1.

Four proposed mechanisms of the Hajos-Parrish reaction

Houk and co-workers reported a detailed DFT investigation of the proposed mechanisms of this reaction.16 Geometry optimizations were performed at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of theory, while energies were computed at the B3LYP/6-31+G(d, p) level of theory with single point PCM solvation corrections for DMSO using HF/6-31+G(d, p) and the UAKS radii.17 The carbinolamine intermediate that precedes the TS corresponding to mechanism A is found to be higher in energy than the uncatalyzed reaction. Such a transition state would be even higher in energy than this intermediate. Mechanism B is disfavored by ~30 kcal/mol due to the distortion of the enamine from planarity to accommodate proton transfer. Mechanism C is disfavored due to the entropic penalties associated with the involvement of another molecule of proline. Mechanism D is favored energetically; this transition structure is ~10 kcal/mol lower in energy than the uncatalyzed process. The preference for this mechanism stems from the enhanced nucleophilicity of the planar enamine as well as the activation of the carbonyl electrophile by the carboxylic acid.

The entire transformation leading from the attack of the exocyclic ketone by the proline moiety through the aldol transition state and the subsequent hydrolysis of the product iminium has been investigated in detail.14 More recent kinetic isotope effect experiments and calculations lead to the conclusion that the rate-determining step occurs prior to C–C bond formation.18

2.1.1.2. Origins of stereoselectivity

The stereoselectivity of the Hajos-Parrish reaction has also been investigated by Houk and coworkers using B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of theory.19 Two chair Zimmerman-Traxler-like transition states are possible: the syn and the anti (Figure 1). The syn and anti refer to orientation of the enamine with respect to the carboxylic acid. The anti transition state leads to the formation of the experimentally observed product, while the syn leads to the formation of the minor product. The 3.4 kcal/mol preference for the anti TS corresponds reasonably well to the experimentally observed stereoselectivity of 95 % ee (2.2 kcal/mol). A later study involving a single point at the B3LYP/6-311+G(2df, p) level of theory was shown to reproduce the exact experimental stereoselectivity of 2.2 kcal/mol for the Hajos-Parrish reaction.20

Figure 1.

The computed anti and syn transition structures of proline-catalyzed Hajos-Parrish reaction

The enantioselectivity of the Hajos-Parrish reaction is directly related to the ability with which each of the transition states can achieve optimal enamine nucleophilicity and provide the greatest electrostatic stabilization to the developing negative charge on the carbonyl electrophile. A planar enamine allows for optimal nucleophilicity to the enamine and experiences minimal geometric distortion to form the iminium upon C–C bond formation. The proton donation from the carboxylic acid moiety and, to a lesser extent, the δ+NCH···Oδ− electrostatic interactions stabilize the developing alkoxide.

The enamine of the anti TS is much more planar than the syn TS. This distortion of the syn TS arises from the necessity to proton transfer to a more proximal alkoxide, which in turn, results in the distortion of the pyrrolidine ring. In contrast, such distortions are unnecessary in the anti TS in which there is ample distance between the carboxylic acid and the developing alkoxide.

The δ+NCH···Oδ− electrostatic interaction exists for both the syn and anti TSs. However, the distance is much shorter (2.4 Å) and therefore the interaction is stronger in the anti TS, in comparison to the syn, where this distance is much longer (3.4 Å). The absolute magnitude of the δ+NCH···Oδ− interaction is also greater in the anti TS than in the syn, due to the greater positive charge on the far more advanced developing iminium.

2.1.1.3. Catalysis by proline derivatives

Houk and co-workers have also reported the origins and predictions of stereoselectivities of the Hajos-Parrish reaction catalyzed by a diverse range of proline-derivatives (Scheme 2).21 B3LYP/6-31G(d) geometry optimizations followed by B3LYP/6-311+G(2df, p) reproduced the exact enantioselectivities of the derivatives for which the reaction has been reported. This combination of methods yielded excellent correlation between the computed and experimental stereoselectivities (mean absolute error, MAE = 0.1 kcal/mol). The Houk-List model, described later in Scheme 10, provides the basis for the experimentally observed stereoselectivities of all the catalysts in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2.

Various proline derivative catalysts for the Hajos-Parrish reaction studied by Houk

Scheme 10.

The Houk-List model for predicting the stereoselectivity of the intermolecular aldol reaction catalyzed by proline

4,5-methanoproline

The first computational investigations of proline-derivative catalyzed Hajos-Parrish reaction was reported by a joint collaboration between Houk and Hanessian groups.20 At the time, the Hanessian group had reported the synthesis of cis- and trans-4,5-methanoprolines as conformationally rigid proline surrogates (5 and 6). Interestingly, the Hanessian group discovered that the cis-4,5-methanoprolines exhibited similar stereoselectivity and reactivity as proline in the Hajos-Parrish reaction, whereas the trans-4,5-methanoproline was a poorer catalyst, both in terms of selectivity and rate.

Bicyclo[3.1.0]hexanes are known to favor the boat conformation over the chair due to the torsional interactions around the fused cyclopropane ring. The computed lowest energy conformations of the cis- and trans-methanoproline enamines revealed that the trans-methanoproline enamine is the expected boat with a significantly pyramidalized amine. The cis-methanoproline was also found to be the expected boat; however, the steric repulsion of the carboxylic acid group syn to the cyclopropane ring resulted in a rather planar cis-methanoproline enamine.

The stereoselectivity of the Hajos-Parrish reactions catalyzed by these methanoprolines is dictated by the native conformational preference of the respective proline derivatives. In the cis-methanoproline case, the planar enamine allows for a facile transition to the anti, planar iminium transition structure, whereas the realization of the pyramidalized syn transition structure would require geometric distortion (Figure 2). This is in contrast to the trans-methanoproline, where the naturally pyramidalized enamine requires less geometric distortion to reach the syn, pyramidalized iminium transition structure, than the planar anti. Despite this conformational bias, trans-methanoproline is still anti-selective not only due to the stability gained by the more planar iminium of the anti transition structure but because of the accentuated interaction between the cyclopropyl methylene hydrogen and the developing alkoxide oxygen.

Figure 2.

The computed anti and syn transition structures of 4,5-methanoproline (5, 6)-catalyzed Hajos-Parrish reactions.

The observed catalytic ability of the two derivatives can also be explained by the conformational biases. The energy required for the naturally pyramidalized trans stereoisomer to achieve the necessary planar iminium arrangement in the aldol transition state is responsible for its comparatively poorer catalytic ability.

Pyrrolidine-2-thioic and dithioic acids

The pyrrolidine-2-thioic acid (2) and the closely related pyrrolidine-2-dithioic acid (3) feature acid groups that prefer longer ideal proton transfer distances. As expected, there is a substantial penalty for the syn transition states for cases where the proton transfer occurs from the sulfur (4.8 kcal/mol), while proton transfer from the oxygen exhibited a smaller preference (2.8 kcal/mol, Figure 3).21

Figure 3.

The computed anti and syn transition structures of thioic acid (2) and dithioic acid (3) catalyzed Hajos-Parrish reactions.

Protonated amine

The protonated amine case (4), which features a quaternary ammonium cation as the proton donor in lieu of a carboxylic acid moiety, was particularly unique from the other catalysts in that it exhibited a reversal in the stereoselectivity (4.7 kcal/mol preference for the syn transition structure, Figure 4).21 This reversal is seen to be caused by two factors: 1) the relief of geometric strain in the syn transition structure due to the change in hybridization of the proton donor; 2) and the destabilization of the anti transition structure due to the steric interactions between the ammonium ion and the substrate.

Figure 4.

The computed anti and syn transition structures of quaternary ammonium (4) catalyzed Hajos-Parrish reactions.

Isoxazolidine-3-carboxylic acid

The isoxazolidine-3-carboxylic acid (7) is an interesting choice of catalyst, due to the possibility of increased nucleophilicity originating from an α-effect. This catalyst also lacks the ability to stabilize the developing alkoxide via δ+NCH···Oδ− interactions. The computed activation barrier for the C-C bond formation for this catalyst was ΔH‡ = 10.0 kcal/mol, which was found to be similar to the analogous barrier in proline of 10.0 kcal/mol.21 The lack of change in reactivity is most likely due to the fact that the repulsive δ−NO···Oδ− interactions erode any potential reactivity gained from the α-effect. This same repulsive interaction is also responsible for the lack of any computed stereoselectivity for this catalyst (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The computed anti and syn TSs of isoxazolidine-3-carboxylic acid (7) catalyzed Hajos-Parrish reactions.

5,5-dimethylthiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid (DMTC) and 5,5-dimethyloxazolidine-4-carboxylic acid (DMOC)

5,5-Dimethylthiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid (DMTC, 8) and the closely related 5,5-dimethyloxazolidine-4-carboxylic acid (DMOC, 9) were also studied.21 DMTC is particularly interesting because since the first reports of intermolecular aldol reactions catalyzed by proline, it has been ear-marked as a promising alternative to proline. The presence of the gem-dimethyl groups in both these catalysts create A1,2 strain with the carboxylic acid group. The need to accommodate a proximal alkoxide in the syn TS forces the slight rotation of the carboxylate towards the gem-dimethyl groups as compared to the anti TS (Figure 6). This results in the computed greater stereoselectivity of the DMOC (3.1 kcal/mol) as compared to proline (2.1 kcal/mol). The DMTC exhibited the same stereoselectivity as proline, and this decrease in preference is seen to be from the weaker δ+NCH···Oδ− interaction in DMTC as compared to DMOC.

Figure 6.

The computed anti and syn TSs of 5,5-dimethylthiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid (DMTC) and 5,5-dimethyloxazolidine-4-carboxylic acid (DMOC) catalyzed Hajos-Parrish reactions.

2.1.1.4. Primary amino acid catalysis

Clemente and Houk studied the stereoselectivity of Hajos-Parrish reaction catalyzed by primary amino acids (Scheme 3).22 Primary amino acids exhibit a slightly different stereoselectivity from proline. In the classic Hajos-Parrish reaction, the enantioselectivity exhibited by the primary amino acids are lower than that catalyzed by proline. However, in cases where there is an alkyl substituent on the exocyclic terminus, primary amino acids are more selective than proline.

Scheme 3.

Various primary amino acids and the intramolecular aldol cyclizations studied

Geometry optimizations were performed at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of theory, while energies were computed at the B3LYP/6-31+G(d, p) level of theory with single point PCM solvation corrections for DMSO using HF/6-31+G(d, p) and the UAKS radii.

The enamine mechanism is still operative. In the case of the Hajos-Parrish substrate, the stereoselectivity arises from the energetic discrimination between the syn and the anti enamine cyclizations. The energetic penalty of the syn TS is again explained as a consequence of the geometric distortion required to do proton transfer to a more proximal alkoxide. In the case of primary amino acids, the energetic penalty from this distortion is less than that exhibited by proline (1.7 kcal/mol less than proline), because the absence of the constraining pyrrolidine ring alleviates some of the geometric penalty of the syn TS (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Phenylalanine catalyzed Hajos-Parrish reaction.

In the case where the exocyclic terminus is substituted by a methyl group, the stereoselectivity is influenced by the difference in energy between the Z or E enamines. In the case of proline, the methyl group of the anti-Z-enamine experiences steric interaction with the pyrrolidine ring, while the E-enamine experiences steric interaction with the approaching cyclopentadione electrophile, leading to overall destabilization of the anti-Z transition structure. The syn transition structures are higher in energy. This is in sharp contrast to the phenylalanine anti Z-enamine structures, which exhibits little steric interaction between the methyl and the proton of the phenylalanine enamine (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Proline and phenylalanine catalyzed asymmetric intramolecular aldol condensation.

2.1.2. Intermolecular aldol reactions

The intermolecular aldol reaction was reported by List, Lerner, and Barbas, and is the first report of the rebirth of organocatalysis since the discovery of the Hajos-Parrish reaction (Scheme 4).23

Scheme 4.

The intermolecular aldol reaction catalyzed by proline

2.1.2.1. Mechanism

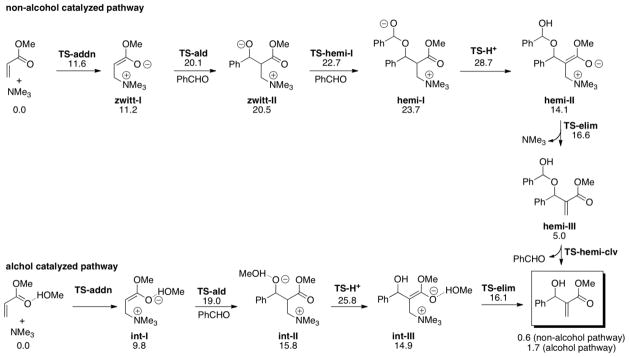

The generally accepted mechanism of proline-catalyzed reactions involves the transformation of the starting carbonyl compound to a more nucleophilic enamine (Scheme 5, left cycle). Although the generation of enamine is critical for catalysis, the details of the process are still not well understood.

Scheme 5.

Mechanistic possibilities involving the enamine and oxazolidinone pathways

Patil and Sunoj24 computed a proton-relay mechanism involving two molecules of methanol for the enamine formation between model substrates (dimethylamine and propanal) at the mPW1PW91/6-31G(d) level of theory. The PCM solvation model with UAKS radii was used to include solvent effects (THF) in the energy calculations. Significantly lower activation energies compared to the unassisted pathway (Scheme 6) suggested a facile enamine formation in the presence of protic additives. The catalytic ability of co-catalysts is explained by the improved transition state stabilization due to effective hydrogen bonding.

Scheme 6.

Activation free energies (ΔG‡, kcal/mol) for hemiacetal, iminium and enamine formation with respect to separated reactants. mPW1PW91/6-31G(d), using PCM and UAKS radii

Clemente and Houk16 studied the pathway involving the formation of an enamine intermediate for a proline-catalyzed intramolecular aldol reaction with B3LYP/6-31+G(d, p)//B3LYP/6-31G(d). The predicted activation energies for the carbinol amine, iminium and enamine formation are 17.0, 15.3 and 26.2 kcal/mol respectively with respect to separated reactants (Scheme 7). More recently, Sunoj and co-workers25 reported the gas phase free energy profile associated with the formation of the enamine intermediate in the reaction between proline and propanal at the B3LYP/6-31+G(d, p) level of theory. The activation free energies for the formation of carbinolamine, iminium and enamine intermediates are found to be 24.2, 25.1 and 26.2 kcal/mol relative to the separated starting compounds.

Scheme 7.

Activation energies (ΔE‡, kcal/mol) for carbinolamine, iminium and enamine formation with respect to separated reactants (B3LYP-6-31+G(d, p)//B3LYP/6-31G(d))

Boyd and co-workers reported a DFT investigation of the mechanism of the proline-catalyzed intermolecular aldol reaction between acetone and acetaldehyde.26 B3LYP/6-311+G(2df, p) single point energies based on B3LYP/6-31G(d) geometry optimizations along with solvation corrections using the Onsager model (DMSO, ε = 46.7) were used.

Boyd and co-workers report that the most difficult step along the reaction potential energy profile is the initial addition of proline to the donor ketone to form the carbinolamine with a barrier of ΔEzp‡ = 40.1 kcal/mol. This was shown to be more difficult than the enamine formation (ΔEzp‡ = 7.1 kcal/mol) or the C-C bond formation step (ΔEzp‡ = 13.7 kcal/mol) in the gas phase. Once solvation corrections have been accounted for, however, the barrier for initial addition drops to ΔEzp‡ = 9.7 kcal/mol, and is more facile than the enamine formation (ΔEzp‡ = 12.0 kcal/mol) or the C-C bond formation step (ΔEzp‡ = 11.1 kcal/mol). They concluded that the use of high polarity solvent is necessary to stabilize the various zwitterionic intermediates and transition state, as expected of an acid-base mechanism.

Reaction progress kinetic analysis of the proline mediated intermolecular aldol reaction by Blackmond and co-workers27 provided evidence that the enamine formation cannot be rate-determining. The rate depends on the concentrations of both the donor ketone and the acceptor aldehyde. The observed isotope effects supports a role for the carboxyl group in the rate limiting step, which is suggested to be the C-C bond formation.

Only very recently, Gschwind and co-workers28 detected and characterized the enamine intermediates in proline catalyzed aldol reactions for the first time experimentally, and showed the direct formation of enamine carboxylic acids from oxazolidinones in the solvent dimethylsulfoxide.

The NMR spectroscopic evidence for the formation of oxazolidinone intermediates in the reactions of proline with carbonyl compounds29 has stimulated significant debate over the mechanism of catalysis. List and co-workers characterized the formation of oxazolidinones in terms of a “parasitic equilibrium”; that is, oxazolidinones are not involved in the catalytic cycle, but their formation would still allow for turnover by keeping the catalyst in solution.29c More recently a catalytic role of oxazolidinone have been proposed that involves a key enamine carboxylate intermediate (Scheme 5, right cycle).30

Sunoj and co-workers25 explored the competing enamine and oxazolidinone pathways (Scheme 5) using density functional and ab-initio MP2 calculations. Scheme 8 shows the activation free energies of alternative pathways for the conversion of iminium carboxylate to various key intermediates computed with B3LYP/6-31+G(d, p). The barrier for the formation of the oxazolidinone intermediate by the intramolecular attack of carboxylate to imium is only 0.7 kcal/mol. Higher activation free energies for the formation of enamine carboxylic acid (12.8) and enamine carboxylate (18.0) suggest an equilibrium composition in favor of the oxazolidinone intermediate, in agreement with the experiments. The C-C bond formation steps for both enamine and oxazolidinone pathways were also examined (Figure 9). The C-C bond formation barriers for the oxazolidinone pathway are higher by 11.6 kcal/mol compared to the enamine pathway, and do not predict the correct stereochemistry of the major product. The resulting oxazolidinone products are also found to be significantly higher in energy than the corresponding iminium products in the enamine pathway. Although the energetics support the enamine pathway, a likely convergence between the enamine and oxazolidine pathways under the experimental conditions is proposed based on the variance of enantio- and diastereoselectivities under different conditions.

Scheme 8.

Gibbs free energies of activation (ΔG‡, kcal/mol) for the conversion of iminium carboxylate to various key intermediates calculated with B3LYP/6-31+G(d, p) (Energies for the formation of anti intermediates are given along with that for syn intermediates in square brackets)

Figure 9.

Gibbs free energies of activation (ΔG‡, kcal/mol) for the C-C bond formation in the enamine and oxazolidinone pathways calculated with B3LYP/6-31+G(d, p). Free energies of iminium and oxazolidinone products (ΔG, kcal/mol) are given in parenthesis.

Blackmond and co-workers31 carried out experimental studies of the role of base additives in enamine catalysis of aminations and observed an unusual reversal of enantioselectivity, in line with the kinetically controlled outcome of the oxazolidinone pathway.

2.1.2.2. Origins of stereoselectivity

The Zimmerman-Traxler model

In List’s initial paper on the proline-catalyzed intermolecular aldol reaction,23 the enantioselectivities were rationalized based on the Zimmerman-Traxler transition states (Scheme 9),32 originally described for metal enolate aldol reactions. In this model, the nitrogen of the proline enamine is aiding the proton transfer from the carboxylic acid to the forming alkoxide. The stereoselectivity arises from a switch in the axial or equatorial orientation of the electrophile substituent.

Scheme 9.

The Zimmerman-Traxler transition states proposed by List and co-workers to rationalize the stereoselectivities of proline-catalyzed intermolecular aldol reactions

The Houk-List model

Joint efforts by the Houk and List groups resulted in the Houk-List model to explain the origin of stereoselectivity of proline catalyzed intermolecular aldol reactions.8,33 In contrast to the Hajos-Parrish reaction where the intramolecular nature of the aldol addition restricts the approach of the electrophile, the carbonyl of the electrophile in the intermolecular case can realize various dihedral angles with respect to the enamine double bond. Calculations from Bahmanyar and Houk indicate that only the transition structures that involve intramolecular proton catalysis are energetically viable. DFT (B3LYP/6-31G(d)) computations of a simple model system involving the proline enamine attack of acetaldehyde revealed that only certain rotamers with a dihedral angle of ±60° can participate in the H-bonding. In particular, transition structures with a dihedral −60° were found to be 5–10 kcal/mol higher in energy than those with +60° (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Rotameric anti-re transition structures of the intermolecular aldol reaction between acetone and acetaldehyde, catalyzed by proline.

Scheme 10 shows the Houk-List model for predicting the stereoselectivity of proline-catalyzed intermolecular aldol reactions. Transition structures involving the anti proline enamine are favored over the syn, due to: (1) the greater electrostatic stabilization arising from the δ+NCH···Oδ− interaction; (2) the syn transition structures suffer from distortion of the pyrrolidine ring to accommodate proton transfer to a more proximal developing alkoxide; and (3) transition structures involving the syn-enamine force the substituents at the forming C-C bond to be nearly eclipsed.

The re face attack is found to be preferred over the si face attack. This minimizes the steric interaction between the aldehyde substituent and the enamine, placing the substituent in a pseudo-equatorial conformation. The re face attack also generally features a more perfect staggering of substituents around the forming C-C bond.

The computed transition state geometries reveal that the carboxylic acid proton and enamine nitrogen (N···H distance ~2.5 Å) are not arranged to form an ideal Zimmerman-Traxler six-membered ring, as had been originally surmised by List.23 on the other hand, the remaining five atoms are arranged in a chairlike arrangement. These findings are summarized in the Houk-List model, which can be represented as a Newman projection centered at the forming C-C bond or in the offset Newman arrangement that shows the chairlike arrangement of the five heavy atoms involved in bonding changes (Scheme 10).

The Seebach-Eschenmoser model

More recently, the Seebach-Eschenmoser model has been proposed to explain the origin of selectivity (Scheme 11).30 This model involves the enamine carboxylate as a key reaction intermediate. They suggested anti-addition to the syn-enamine rotamer, which leads to the more stable, exo isomer of the product oxazolidinone, and ultimately to the experimentally observed stereoisomer of the product.

Scheme 11.

The Seebach-Eschenmoser model for predicting the stereoselectivity of the intermolecular aldol reaction catalyzed by proline

In order to gauge the accuracies of DFT in reproducing the stereoselectivities of proline-catalyzed aldol reactions, the average absolute errors in calculations for three known aldol reactions were determined.8 B3LYP/6-31G(d) was shown to have average absolute errors of approximately ±0.5 kcal/mol.

Predictions of stereoselectivities

Houk and Bahmanyar predicted the stereoselectivities of proline-catalyzed intermolecular aldol reactions between cyclohexanone and benzaldehyde.8,33 The predictions were computed prior to the experiments, which were in turn performed by Benjamin List. They reported excellent agreement between the quantum mechanical prediction and the experimental results. Subsequent calculations indicated that different predictions were obtained when more extensive conformational searches were performed, and are described in a recent published interview of Houk.34 List also found that the stereochemical results obtained with the proline catalyzed reaction of cyclohexanone and benzaldehyde were highly dependent on adventitious water and temperature, so that the agreement of theory and experiment was rather fortuitous.

2.1.2.3. 5-pyrrolidin-2-yltetrazole

5-Pyrrolidin-2-yltetrazole is one of the currently most interesting analogues of proline, in particular for reactions when less reactive aldehydes are employed as aldol acceptors (Scheme 12). In addition, although tetrazoles and carboxylic acids have similar pKa values, the tetrazole group is much more lipophilic and, unlike proline, does not suffer from solvation issues in organic solvents.

Scheme 12.

The 5-pyrrolidin-2-yltetrazole catalyzed intermolecular aldol reactions

Domingo and co-workers performed a B3LYP/6-31G(d, p) study of the tetrazole-catalyzed intermolecular aldol reaction between acetone and pivaldehyde.35 Solvation energies were computed for DMSO using the PCM method. The tetrazole catalyst can exist in two different tautomers (Scheme 13). The 2-tautomer is more stable than the 3-tautomer form by 2.4 kcal/mol in the gas phase. Solvation corrections increased this difference by 3.3 kcal/mol.

Scheme 13.

The two tautomeric forms of 5-pyrrolidin-2-yltetrazole catalyst. DMSO energies are in brackets

Domingo and co-workers state that the origins of stereoselectivity are similar to the reported proline case by Houk and co-workers. The transition structures involving anti enamine attack on the re face of the pivaldehyde was favored (Figure 11). However, the most interesting feature of note in this report was the discovery that the free energy of activation of the tetrazole catalyst was lower than that of the prolines. This is a consequence of the larger solvation corrections for the tetrazole transition structures (ΔGsolv = 11.1 kcal/mol) than the proline transition structures (ΔGsolv = 7.4 kcal/mol).

Figure 11.

Anti-re and anti-si TSs of the intermolecular aldol reaction between acetone and pivaldehyde, catalyzed by proline and 5-pyrrolidin-2-yltetrazole. DMSO values in brackets.

2.1.2.4. Proline amide derivatives

Wu and co-workers have reported the development of a proline amide derivative as a catalyst for the intermolecular aldol reaction of acetone and p-nitrobenzaldehyde (Scheme 14).36 These catalysts are of particular interest as a more active and stereoselective catalyst than the parent proline. They yield the same enantioselectivity as the proline aldol reactions.

Scheme 14.

Proline amide derivatives as catalysts for the intermolecular aldol reaction

HF/6-31G(d) geometries with B3LYP/6-31G(d, p) single points were used to compute the transition structures of various proline-amide derivative catalyzed aldol reactions. The computed activation barriers of simple proline amides, which lack a strongly acidic proton, are similar to those catalyzed by proline. As expected, the presence of another H-bond donor decreases the aldol barrier even further, as shown by the transition structure of (1S,2S)-diphenyl-2-aminoethanol amide derivative (Figure 12). Experimental observations also show that the doubly hydrogen bonded aminoethanol amide derivative is more reactive than proline or the parent proline amide.

Figure 12.

Anti-re and anti-si transition structures of the intermolecular aldol reaction between acetone and benzaldehyde, catalyzed by (1S,2S)-diphenyl-2-aminoethanol amide proline derivative.

The use of (1S,2S)-diphenyl-2-aminoethanol amide derivative resulted in a substantial increase in stereoselectivity, as compared to proline. This increase in stereoselectivity is said to arise from the steric interaction between the phenyl of the benzaldehyde and the hydroxyl of the aminoethanol in the si attack of the anti enamine.

Gong and co-workers reported highly selective aldol reactions of ketones with α-keto acids using amides prepared from proline and aminopyridines (Scheme 15).37 B3LYP/6-31+G(d) was used to explain the high enantioselectivity of the reaction.

Scheme 15.

Organocatalyzed aldol reaction of ketones with α-keto acids

It was proposed that the pyridine nitrogen of the catalyst could hydrogen bond with the acid, while the amide hydrogen could bind with the α-keto acid at the carbonyl of either the keto or ester group (Scheme 16). Binding at the keto group was calculated to be favored by 2.5 kcal/mol. Single hydrogen bonding of the amide hydrogen with either carbonyl group (and without interaction of the pyridine nitrogen) was calculated to be disfavored by 8.0–8.7 kcal/mol.

Scheme 16.

Possible binding modes of catalyst with α-keto acid

The Gong research group also investigated the intermolecular aldol reaction of hydroxyacetone with benzaldehyde, catalyzed by a proline amide (Scheme 17).38 It was found that water influenced the regioselectivity, affording products with enantioselectivities ranging from 91 to 99% ee. Theoretical studies (B3LYP/6-31++G(d, p)//HF/6-31+G(d) with explicit solvation by water) revealed that this is due to the hydrogen bonds formed between the amide oxygen of proline amide, the hydroxy of hydroxyacetone, and water. HF generally gives poor activation energies because of the lack of correlation energy. This may also cause the position of the transition state to be in error. However, geometries with HF are reasonable, if less accurate than B3LYP geometries, so that use of HF for geometries is occasionally employed for large systems.

Scheme 17.

Intermolecular aldol reaction of hydroxyacetone with benzaldehyde, catalyzed by a proline amide

The anti enamine and anti enol enamine were predicted to differ in stability by only 0.4 kcal/mol (Scheme 18). In the absence of explicit solvation, the transition state leading to the minor 1,2-diol regioisomer (via the enol enamine) was calculated to be favored over the transition state leading to the major 1,4-diol regioisomer (via the enamine) by 4.3 kcal/mol. This regioselectivity is attributed to the short hydrogen-hydrogen distance of 2.34 Å between an amide hydrogen and hydroxy hydrogen in the disfavored transition state.

Scheme 18.

Top: Relative stabilities of anti enamine and anti enol enamine. Bottom: Activation free energies for 1,2-diol and 1,4-diol formation

With the inclusion of an explicit water molecule, the calculated relative energies of the transition states still favor the experimental 1,2-diol (Figure 13). It was reasoned that the experimentally observed selectivity for the 1,4-diol is attributed to the stabilities of the enamine-water complexes. The 6.6 kcal/mol stability of the anti enamine compared to the anti enol enamine leads to formation of the favored 1,4-diol.

Figure 13.

Aldol reaction of benzaldehyde and hydroxyacetone catalyzed by proline amide.

Okuyama and co-workers observed high stereoselectivities in aldol and Michael addition reactions catalyzed by 4-hydroxyprolinamide alcohols (Scheme 19).39 B3LYP/6-31G(d) calculations were performed to understand the high selectivity observed in the reaction between acetone and benzaldehyde (99% ee).

Scheme 19.

Aldol reaction of acetone and cyclohexanones catalyzed by a 4-hydroxyprolineamide alcohol

The anti conformation of the enamine was assumed to be the most stable, and attack on the re- and si-faces of benzaldehyde were calculated. Only one conformation for each of these transition states was located due to steric hindrance of the two gem-diphenyl groups of the catalyst (Figure 14). The 5.3 kcal/mol difference between the transition states leading to the major (R) and minor (S) isomers is in excellent agreement with the experimental results.

Figure 14.

anti-re and anti-si transition structures for the prolineamide-catalyzed aldol reaction.

2.1.2.5. Primary amino acids

Acyclic primary amino acids have also been discovered to be catalysts for the intermolecular aldol reactions (Scheme 20), as discussed earlier for the Hajos-Parrish reaction.40 Simple natural and unnatural primary amino acid derivatives catalyzed the reaction between cyclohexanone and an aldehyde in high yield and enantioselectivities.

Scheme 20.

Primary amino acid catalyzed intermolecular aldol reaction between cyclohexanone and para-nitrobenzaldehyde

Córdova has reported the origins of stereoselectivity of this reaction using B3LYP/6-31G(d, p) geometry optimizations and B3LYP/6-31+G(2d,2p) single points.41 Four factors were seen to control the stereoselectivity of this reaction: (1) The C-N bond of the amino acid can rotate in the enamine intermediate, in contrast to the corresponding proline-derived enamine intermediates. (2) δ+NH···Oδ− electrostatic interactions between the amine proton and the forming alkoxide are stabilizing. Transition state (R, R), which lacks this interaction, is higher in energy by 2–5 kcal/mol (Figure 15). (3) The steric interactions between the aldehyde phenyl and the enamine cyclohexyl are destabilizing. The (S, S) transition state is thus more crowded than the corresponding (S, R) transition state, which lacks this destabilizing interaction. The same holds true for the (R, R) transition state compared to the (R, S) transition state. (4) Finally, the methyl substituent of alanine interacts unfavorably with the cyclohexyl ring, destabilizing the (R, S) transition state by 3.2 kcal/mol compared to the (S, R).

Figure 15.

(S, R), (S, S), (R, R), and (R, S) TSs for the reaction between cyclohexanone enamine of alanine and benzaldehyde

The same group computed the reaction profile for formation of the major (S, R) product (Figure 16a). The overall reaction profile is analogous to various proline-catalyzed processes. It is worthy to note that the oxazolidinone is 4.6 kcal/mol more stable compared to the active catalyst enamine (Figure 16b). Córdova stated that the need for water in the reaction mixture experimentally is to drive the equilibrium towards the enamine from the oxazolidinone.

Figure 16.

(a) Overall reaction profile for primary amino acid catalyzed aldol reaction. (b) Relative energies of oxazolidinone and enamine (kcal/mol).

Blackmond and co-workers later investigated the effect of water in proline-mediated aldol reactions using reaction progress kinetics analysis.29e Their results showed two conflicting roles for water: 1) increasing the total catalyst concentration within the cycle due to the suppression of spectator species, such as oxazolidinones; 2) decreasing the relative concentrations of key intermediates in the cycle by shifting the equilibrium from the iminium carboxylate back toward proline.

2.1.2.6. Cyclic aminophosphonates - pyrrolidin-2-ylphosphonic acid

Dinér and Amedjkouh reported the aldol reaction of acetone and cyclohexanone derivatives with para-nitrobenzaldehyde catalyzed by pyrrolidin-2-ylphosphonic acid (Scheme 21).42 This catalyst is the phosphonic acid version of proline, and was studied as a candidate for the syn-aldol catalyst.

Scheme 21.

Pyrrolidin-2-ylphosphonic acid catalyzed intermolecular aldol reactions

The reaction involving acetone and para-nitrobenzaldehyde has been studied computationally using B3LYP/6-31G(d). The three most important transition structures are shown in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

The most stable anti-re, anti-si, and syn-re transition structures.

The origins of stereoselectivity for this catalyst are very similar to those for the proline cases. The one notable difference between this catalyst and proline is that the syn-re transition state is only 0.9 kcal/mol disfavored compared to the most stable anti-re, whereas in proline, this difference is greater (>2 kcal/mol).

All enantioselective organocatalysts known to date yield the anti-aldol as major products. The authors hoped that the reduced preference between the anti and syn enamine preference in the aldol transition state of this catalyst would favor the formation of syn aldol in the reaction between benzaldehyde and various cyclohexanone derivatives. However, even with Lewis base additives which enhance the syn-aldol selectivity to the reaction mixture, the authors found only modest preference for the syn aldol (syn:anti ~1:1).

2.1.2.7. Nornicotine

Lovell, Noodleman, and Janda have reported the experimental and theoretical studies of nornicotine aqueous aldol reactions between acetone and substituted benzaldehydes. Notably, proline and pyrrolidine are poor catalysts for the aqueous aldol reactions. The mechanism they proposed for this reaction is shown in Scheme 22.43

Scheme 22.

Nornicotine catalyzed intermolecular aldol reaction mechanism

Lovell, Noodleman, and Janda propose that the nornicotine catalyst reacts via the enamine pathway, but invoked an unusual transition state in which a molecule of water simultaneously attacks the internal carbon of the enamine olefin and donates a proton to the forming alkoxide. In addition a second molecule of water is suggested to be present in the transition structure that later participates in the hydrolysis of the catalyst. No explanations were offered to justify the necessity for the electrophile addition to the more hindered face of the enamine.

This mechanism is based on their calculations for the model reaction of acetaldehyde and acetone (Scheme 23). However, the authors did not include the 9 kcal/mol higher energy of the enol tautomer of acetone compared to acetone. Furthermore, this high energy pathway, in which the first transition structure is entropically disfavored, was not explained.

Scheme 23.

Intermolecular aldol reaction mechanism computed by Janda and co-workers43 (B3LYP/6-311+G(2d,2p)//B3LYP/6-311G(d, p); COSMO model for solvation energies (water))

Zhang and Houk computed the same aldol reaction in water and proposed an alternative mechanism involving water ionization.44 The reaction involves three steps: (1) water autoionization, (2) hydroxide or hydronium-catalyzed conversion of aldehyde or ketone into enol, and (3) C-C bond formation and proton transfer to give the aldol product. The overall process for the reaction of acetone and acetaldehyde using B3LYP/6-311++G(3d,3p)//B3LYP/6-31G(d) and the CPCM solvation model are shown in Scheme 24. Two alternative possible mechanisms—(1) initial proton transfer from the ketone enol to water, and (2) initial proton transfer from the ketone enol to aldehyde—were also computed, but the highest-energy species of these reactions are significantly higher in energy than that of the mechanism shown in Scheme 24. While C-C bond formation was calculated to be the rate-determining step, formation of the enol or enolate may be rate-determining for more reactive aldehydes.

Scheme 24.

Intermolecular aldol reaction mechanism computed by Janda and co-workers43 (B3LYP/6-311+G(2d,2p)//B3LYP/6-311G(d, p); COSMO model for solvation energies (water))

2.1.3. Mannich reaction

The discovery of the intermolecular aldol reaction soon paved the way for the discovery that additions to various other double bonds would also be possible. The proline-catalyzed direct Mannich reaction is a natural extension of the aldol reaction, and is a highly effective carbon-carbon bond-forming reaction that is used for the preparation of enantiomerically enriched amino acids, amino alcohols, and their derivatives (Scheme 25).45

Scheme 25.

Typical intermolecular Mannich and aldol reactions catalyzed by proline

Origin of the reverse enantioselectivity compared to the aldol reaction

The enantioselectivity of the Mannich reaction is opposite that of the aldol reaction. Computational investigations by Houk and co-workers show that the imine acceptor must be situated so as to accommodate proton transfer to nitrogen (Figure 18).46 This situates the carbon substituent in the more crowded pseudo-axial position.

Figure 18.

The anti-re and -si TSs of the Mannich reaction, and anti-re TS of the aldol reaction catalyzed by proline.

The enhanced rate of the Mannich reaction versus the aldol reaction

It is also of interest to note that proline-catalyzed Mannich reactions are often much faster than the corresponding aldol reaction. Hayashi and co-workers have suggested that the more basic imines are more readily activated by the carboxylic acid of proline.47

The origin of erosion of diastereoselectivity in the pipecolic acid catalyzed Mannich reaction

Barbas’ group reported that pipecolic acid catalysis gives both syn and anti diastereomers with high enantioselectivity (Scheme 26).48 The diastereomeric ratio of syn- versus anti-product ranged from 2:1 to 1:1. This unusual change in diastereoselectivity upon the increase in ring size from five to six was investigated computationally by Cheong and Houk.48

Scheme 26.

Intermolecular Mannich reaction of aldehydes catalyzed by pipecolic acid

The C-C bond forming steps involving both pipecolic acid and proline enamines of propionaldehyde attacking the N-PMP-protected R-imino methyl glyoxylate were calculated at the HF level of theory with the 6-31G(d) basis set.

The diastereoselectivity of this reaction is determined by whether the anti or syn enamine conformer is favored in the transition structure. In the case of proline, the transition structures involving the anti-enamine are favored over those that involve the syn-enamine. The latter involves distortions of the developing iminium from planarity to accommodate proton transfer, and the computed diastereoselectivity given by the difference in anti-si and syn-si transition structures is 1.0 kcal/mol.

This differentiation is weakened in the case of pipecolic acid – the analogous difference for pipecolic acid is only 0.2 kcal/mol (Figure 19). The piperidine ring experiences steric interactions with the anti or syn-enamines that are different than those of the pyrrolidine ring of proline. The relatively rigid piperidine ring holds the carboxylic acid more rigidly than the more flexible pyrrolidine. This alters electrostatic interactions with the ester of the iminoglyoxylate and with the protonated imine. These differences allow the imine to react via both the anti and syn-enamine, giving rise to roughly equal amounts of both syn- and anti-product experimentally and computationally. Although the calculated selectivities are in good agreement with the experiments, it should be noted that various benchmarks show that such small energy differences fall in the error margin of the most of the standard computational methods.2–7 It is generally assumed, without proof, that these methods are able to predict small differences in the energies of stereoisomeric transition states.

Figure 19.

The anti-si and syn-si transition structures of Mannich reaction catalyzed by pipecolic acid.

The facial re or si selectivity of the imine acceptor is governed by the necessity for intramolecular proton transfer and minimization of steric interactions between the imine and the reactive enamine. The E-imine is more stable than the Z-imine. Transition structures involving intramolecular proton transfer are favored; thus the re face attacks necessitate substantial eclipsing of the imine and enamine. Consequently, anti-re and syn-re transition structures are higher in energy by >1 kcal/mol than the anti-si or syn-si transition structure for both proline and pipecolic acid.

The Mannich reaction catalyzed by diarylprolinol silyl ethers

Hayashi and co-workers used B3LYP/6-31G(d) to investigate the role of acid additives in the Mannich reaction of imines and acetaldehyde catalyzed by diarylprolinol silyl ethers (Scheme 27).49 The catalyst was modeled by 2-methylpyrrolidine and the imine was modeled by N-benzoyl-N-benzylidenenamine. The lowest energy conformer was calculated to have an s-cis geometry around the C=N–C=O bond (Scheme 28). The s-trans conformer converged to a transition structure for the rotation of this dihedral. The Z-isomer is approximately 30 kcal/mol higher in energy than the E. The modeled enamine was calculated to have a small 0.7 kcal/mol preference for an anti alkene with respect to the pyrrolidine methyl group. The imine was calculated to favor protonation of the nitrogen versus protonation of the carbonyl oxygen by approximately 7 kcal/mol.

Scheme 27.

Diarylprolinol silyl ether catalyzed Mannich reaction

Scheme 28.

Imine and enamine conformers

Addition of the acetaldehyde anti-enamine to the protonated imine was calculated to be highly exothermic (−31.1 kcal/mol in THF, PCM model) and barrierless. The favored transition structure was modeled by constraining the forming C–C bond at 3.0 Å and plotting the energy versus the dihedral angle around this bond. The optimal geometry was located at a dihedral angle of 140 between the reacting imine and enamine double bonds (Figure 20). Because the addition step is extremely fast, the authors conclude that enaminium formation is the rate-determining step of the reaction.

Figure 20.

Transition state model for Mannich reaction of acetaldehyde and protonated N-benzoyl iminium.

Wong also investigated a similar Mannich reaction using the same catalyst and concluded that the reaction proceeds through an enol rather than an enamine intermediate (Scheme 29).50 The calculated enantioselectivity is in good agreement with experimental results. Wong also proposed that the Michael-aldol condensation, Michael addition, α-amination, α-fluorination, and α-sulfenylation, and α-bromination reactions proceed by an enol intermediate with this catalyst.

Scheme 29.

Mannich reaction via an enol mechanism

The Mannich reaction catalyzed by (S)-1-(2-pyrrolidinylmethyl) pyrrolidine

Li and co-workers used BH&HLYP to explain the opposite diastereoselectivities obtained by (S)-1-(2-pyrrolidinylmethyl) pyrrolidine and proline in the direct Mannich reactions between ketimine and isovaleraldehyde reported by Jørgensen and co-workers (Scheme 30).51 Sketches and relative energies of the lowest energy transition structures for each diastereomeric product are shown in Scheme 31. The (S, S) and (R, S) transition structures are higher in energy than the (R, R) and (S, R) transition structures due to a disfavored steric interaction between the ketimine protecting group and the pyrrolidinyl moiety of the catalyst. In the (R, R) and (S, R) transition structures, the ketimine is attacked from the opposite face of the pyrrolidine group. The stability of the (R, R) transition state compared to the diastereomeric (S, R) transition structure is attributed to three factors: (1) larger degree of planarity of the developing iminium in the (R, R) transition structure, (2) electrostatic stabilization of the imine nitrogen by the catalyst in the (R, R) transition structure, and (3) better staggering around the forming C-C bond in the (R, R) transition structure.

Scheme 30.

Opposite diastereoselectivities observed in the Mannich reaction with proline and pyrrolidinylmethylpyrrolidine catalysts

Scheme 31.

Lowest energy transition structures leading to each diastereomer of the Mannich reaction (BH&HLYP/6-31G(d, p), including solvation energies—CH2Cl2, CPCM/UAKS model)

Catalysis of the same reaction by proline was then studied computationally and represented the first theoretical study of the Mannich reaction of ketimines. The previous studies had involved reactions of aldimines. The lowest energy transition structures for each diastereomer are shown in Scheme 32. The C-C bond forming distances are shorter than those calculated for the reactions of aldimines (2.2–2.4 Å) and the proton transfer occurs later in the ketimine reactions. In agreement with experiment, the lowest energy transition structure involves attack of the anti enamine on the si-face of the ketimine to give the (R, S) product. This transition structure has good staggering around the C–C forming bond and the iminium is stabilized by the carboxylic acid proton.

Scheme 32.

Lowest energy transition structures leading to each diastereomer of the Mannich reaction (BH& HLYP/6-31G(d, p), including solvation energies—CH2Cl2, CPCM/UAKS model)

The computational design of an anti-selective Mannich organocatalyst

Following on the heels of the study of pipecolic acid catalyzed Mannich reactions, Houk and Barbas reported a joint computational and experimental design of an anti-selective organocatalyst (Scheme 33).52 The stereoselective formation of anti-products necessitates a reversal in the facial selectivity of either the enamine or the imine, compared to the proline-catalyzed reactions. A substituent at the 5-position of the pyrrolidine was used to fix the conformation of the enamine. The acid functionality was placed at the distal 3-position of the ring, to affect control of enamine and imine facial selection in the transition state. To avoid steric interactions between the substituent at the 5-position of the new catalyst and the imine in the transition state, the substituents at 3- and 5-positions were placed in the trans configuration. On the basis of these considerations, a new catalyst, (3R,5R)-5-methyl-3-pyrrolidinecarboxylic acid, was designed. The proposed major transition state of the Mannich reaction catalyzed by the new catalyst is shown in Scheme 33.

Scheme 33.

Development of anti-selective Mannich reaction organocatalyst

The reaction between propionaldehyde and N-PMP-protected R-imino methyl glyoxylate was studied using HF/6-31G(d) calculations to test the design prior to synthesis. No computed structures were reported in this work. The catalyst was predicted to give 95:5 anti:syn diastereoselectivity and ~98% ee for the formation of the (2S,3R)-product.

The relative contributions of the carboxylic acid and methyl group of the catalyst in directing the stereochemical outcome of the reaction were assessed. Computational studies involving the derivative lacking the 5-methyl group, (S)-3-pyrrolidinecarboxylic acid, indicate that the methyl group contributes ~1 kcal/mol toward the anti-diastereoselectivity. That is, the stereoselectivity changes to 82:18 anti:syn dr and 92% ee when transition structures with the unmethylated catalyst are located. This unmethylated catalyst was also tested in an actual reaction, for the case where R1 = i-Pr. This derivative afforded (2R,3S)-anti-product in 95:5 anti:syn dr and 93% ee, which is a drop of 0.6 kcal/mol from the 1-catalyzed reaction with the same substrate.

2.1.4. α-Aminoxylation reaction

The proline-catalyzed aminoxylation reaction is a convenient way of oxidizing the α position of carbonyl compounds (Scheme 34).

Scheme 34.

Oxyamination reaction

Three different variations of the mechanism have been proposed (Scheme 35). The proposed mechanisms differed by the degree to which the carboxylic acid or the proline amine participates in the proton-transfer process. The transition state model proposed by Hayashi53 is analogous to the Houk-List model; proton transfer occurs from the carboxylic acid in a “partial-Zimmerman-Traxler” chairlike transition state. Zhong proposed a Zimmerman-Traxler transition state in which the proline amine also facilitates the proton transfer,54 while MacMillan proposed an enammonium-mediated ene-like zwitterionic transition state.55 These pathways do not exhaust the mechanistic possibilities. Nitrosobenzene dimerizes readily, and analogous pathways involving the proline enamine attack on the nitrosobenzene dimer are also possible. Blackmond has reported the observation of an acceleration of reaction rate for the aminoxylation and the related amination reactions by the products of the reaction.56,29f It was concluded that the autoinduction occurs in these reactions but not in the aldol reaction because of a difference in the rate-determing steps. 57

Scheme 35.

Proposed transition states of proline-catalyzed α-aminoxylation reaction

The reaction was investigated computationally by the Cordóva,58a Houk58b and Wong58c groups. Cordóva reports that the C-O bond forming step for the major R-enantiomer occurs via the anti enamine, similar to the model proposed by Hayashi (Scheme 36). Formation of the minor S-enantiomer reportedly occurs via addition of the syn enamine to the re-face of the hydrogen-bound nitrosomethane. The minor transition structure is disfavored by approximately 7 kcal/mol. Attempts to locate a transition structure according to the MacMillan model resulted in structures that are similar to the Hayashi transition structure.

Scheme 36.

B3LYP/6-311+G(2d,2p)//B3LYP/6-31G(d, p) relative gas phase transition structure energies for the aminoxylation reaction

The transition structure for the major R-enantiomer computed by the Houk group (Figure 21)58b is similar to that of Cordóva. However, the minor transition structure (syn-O) differs in that the syn enamine attacks the si-face of the hydrogen-bound nitrosobenzene, as opposed to the re-face described by Cordóva. The transition structure for the minor enantiomer is 3.3 kcal/mol higher in energy than the most stable transition structure for the major enantiomer. This corresponds to a prediction of 99% ee of the product favored experimentally, in reasonable agreement with the experimentally reported ee of 97%.

Figure 21.

B3LYP/6-31G(d) transition structures for the α-aminoxylation reaction. Activation energies include HF/6-31+G(d, p) DMSO, PCM model, UAKS radii solvation.

The model proposed by Zhong is found not to be a transition state, but minimizes to more stable transition state anti-O. Here the proline amine-proton distance is 2.7 Å, and there is no evidence of proline amine pyramidalization. The enammonium-mediated zwitterionic ene-like transition state proposed by MacMillan, with the carboxylate group syn to the proton-transfer face, was not found. The closest enammonium transition structure found was one in which the carboxylate group is anti to the proton transfer; it is 32.4 kcal/mol higher in energy than the most stable transition structure. The high barrier is attributed to the poor nucleophilicity of the enammonium olefin and the great energetic penalty accrued by the charge separation.58b

The transition structures involving the nitrosobenzene dimer are disfavored due to the entropic cost of dimerization and the difficulty of a nucleophilic attack on the partially negatively charged oxygen of the nitrosobenzene dimer. The most stable transition structure involving the nitrosobenzene dimer is 24.4 kcal/mol higher than the most stable pathway involving the nitrosobenzene monomer.58b

The transition structures for attack at nitrogen (oxyamination) were generally higher in energy than those for attack at oxygen. The attack at nitrogen to give the (R)-hydroxyamination product via transition structure anti-N is disfavored by 2.6 kcal/mol. This heteroatom selectivity is also explained by the preferential protonation of the more basic nitrogen. In the absence of Brønsted catalysis, a reversal in heteroatom selectivity is expected. The reaction between the dimethyl enamine of propionaldehyde and nitrosobenzene was computationally shown to favor the attack on the nitrogen.58b

Wong also investigated the reaction and found that the lowest energy transition structures for each enantiomer occur from the anti enamine (Scheme 37). The calculated energy difference is large in the gas phase (5.2 kcal/mol), but decreases substantially with the inclusion of solvent effects (1.3 kcal/mol). The pathway subsequent to bond-formation was also computed with one explicit water molecule. It was found that the resulting imine favors a syn geometry with respect to the catalyst carboxylate in order to maximize hydrogen bonding. 58c

Scheme 37.

B3LYP/6-31G(d, p) activation energies for the α-aminoxylation reaction (Solvation energy corrections (B3LYP/6-311+G(2d,2p) PCM, DMSO) are in brackets)

2.1.5. α-Fluorination

Jørgensen used DFT to explain the enantioselectivities of α-fluorination reactions catalyzed by trimethylsilyl diarylprolinol (Scheme 38).59 Unlike proline, where the carboxylic acid directs the electrophile to the “top” face of the enamine via hydrogen bonding, the TMS diarylprolinol catalyst directs the electrophile to the “bottom” face of the catalyst due to steric shielding (Scheme 39). It was found that there is little preference for the anti or syn enamines of propanal and 3,3-dimethylbutanal (Scheme 40), so transition structures for attack of both anti and syn enamines were calculated.

Scheme 38.

Organocatalyzed α-fluorination reaction

Scheme 39.

Hydrogen bond and steric stereocontrol

Scheme 40.

B3LYP/6-31G(d) relative free energies of anti versus syn enamines

Transition structures for the α-fluorination of 3,3-dimethylbutanal by N-fluorobenzenesulfonamide (NFSI) were located using B3LYP/6-31G(d). The syn and anti conformations and E and Z geometries were considered. The lowest energy transition structures leading to the major (S)- and minor (R)-enantiomers are shown in Figure 22. The major (S)-enantiomer is formed by attack of the anti-E enamine from the “bottom” (si) face to NFSI. The minor (R)-enantiomer is 2.4 kcal/mol higher in energy and is formed by attack of the syn-E-enamine from the “bottom” (re) face to NFSI. This predicted selectivity (96% ee) is in excellent agreement with the enantioselectivity (97% ee) observed experimentally. The energy difference is attributed to good staggering around the forming C-F and breaking F-N bonds in the major enantiomer, but eclipsing around these bonds in the minor enantiomer. The transition structure for the major enantiomer of the α-amination of n-butanal by diethyl azodicarboxylate (DEAD) was also located, but the stereoselectivity was not discussed.

Figure 22.

Lowest energy transition structures for the α-fluorination of 2,2-dimethylbutanal.

2.1.6. γ-Amination

The γ-amination of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes by diethyl azodicarboxylate (DEAD), catalyzed by the same TMS-protected diarylprolinol, was studied computationally by Jørgensen (Scheme 41).60 The (R) enantiomer dominated in these reactions, which is the opposite of what was expected. Density functional theory (B3LYP/6-31G(d) with CPCM solvent corrections) was used to rationalize the stereoselectivity of the reaction. Two low-energy conformers of the enamine were located, E-s-trans-E and E-s-trans-Z (Scheme 42), which differ in energy by 1.4 kcal/mol. This is consistent with 1H-NMR observations of a mixture of isomers; the two isomers are believed to readily interconvertible by a protonation/deprotonation mechanism.

Scheme 41.

γ-amination of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes

Scheme 42.

Mechanism for the γ-amination of 2-pentenal. B3LYP/6-31G(d) energies (with CPCM solvent corrections)

The activation energy for γ-amination of the major (R) isomer with respect to the E-s-trans-E enamine is predicted to be 17.1 kcal/mol, while that of the minor (S) enantiomer is 13.0 kcal/mol. The activation energy for α-amination of both enamine conformations is approximately 21 kcal/mol. Given the discrepancy between the calculated selectivity for the (S)-enantiomer and the experimental observation of the (R)-enantiomer, Diels-Alder cycloaddition barriers of the enamine intermediates were calculated. It was postulated that the resulting Diels-Alder cycloadducts should readily hydrolyze to the γ-aminated aldehyde, and the E-geometry of the C2-C3 double bond would be restablished via a reversible addition mechanism of a nucleophile such as water or the catalyst. The activation energy for the [4+2] cycloaddition of E-s-cis-E was calculated to be only 6.7 kcal/mol (11.6 kcal/mol with respect to the lowest energy enamine, Figure 23), while the activation energy for the [4+2] cycloaddition of E-s-cis-Z was calculated to be 12.3 kcal/mol (18.1 kcal/mol with respect to the lowest energy enamine). The Diels-Alder reactions were calculated to be exothermic, while the γ-amination reactions were calculated to be endothermic. Thus, calculations predict that the preferred mechanism for γ-amination occurs by a Diels-Alder cycloaddition of the E-s-cis-E enamine, followed by hydrolysis to give the (R) product. To support the Diels-Alder mechanism, 2-pentenal and the pyrrolidine catalyst were reacted with N-methylmaleimide instead of DEAD. The Diels-Alder cycloadduct was isolated.

Figure 23.

Lowest energy transition structures for the [4+2] cycloaddition of enamines and DEAD.

The Seebach group computed the relative energies of the enamine formed by 2-pentenal, and the iminium formed by 3-phenyl-2-propenal, with TMS-protected diarylprolinol catalyst using B3LYP and MP2 and found that the anti-all-trans conformations are most stable (Figure 24).61 The most stable calculated iminium geometry overlays very well with the crystal structure.

Figure 24.

DFT gas phase relative energies calculated by Seebach and co-workers (ref 47).

2.1.7. α-Alkylation

The intramolecular catalytic asymmetric α-alkylation of aldehydes was developed by List and co-workers. The synthesis of cyclic aldehydes via proline and 2-methylproline catalyzed cyclizations of acyclic halo-aldehydes are shown in Scheme 43.62

Scheme 43.

The prototypical proline and 2-methylproline catalyzed alkylation reaction

Two items are of particular interest in this reaction: (1) Simple methyl substitution at the 2-position of proline enhanced the stereoselectivity of the reaction, as shown in Scheme 43. (2) Triethylamine accelerates the reaction. Thiel and List reported a computational investigation of this reaction using B3LYP with the 6-31G(d) and LANL2DZ basis sets.63 CHCl3 solvation effects were taken into account by geometry optimizations using the Onsager model and single point energies using the CPCM method with the UAKS radii. Triethylamine was modeled using trimethylamine.

The reaction proceeds via the enamine nucleophilic displacement of the halogen, analogous to the typical proline mechanisms (Figure 25). The rate and stereo-determining step was considered to be the alkylation step. It is interesting to note that the stabilization of the departing iodide by the carboxylic acid of the catalyst induces a cisoid conformation of the carboxylic acid, while in other reported reactions involving proline, the transoid conformation is preferred. Triethylamine was found to provide a salt bridge between the carboxylic acid and the departing halide.

Figure 25.

The two lowest energy alkylation transition structures involving 2-methylproline and trimethylamine

The stereoselectivity of this reaction arises from preferred cyclization by the anti enamine. The basic origin of stereoselectivity remains the same – the cyclization of the syn enamine accrues energetic penalties due to the catalyst stabilization of a more proximal developing anion. The calculated 99% ee is in good agreement with the experimentally observed 95% ee. The enhanced enantioselectivity for the 2-methylproline catalyzed aldol reaction compared to the proline-catalyzed reaction is due to the inherently larger steric interactions between the methyl and the aldehyde substituent in the syn transition structure. Again, the calculated 66% ee for the proline-catalyzed reaction is in good agreement with the experimental 68% ee.

2.1.8. Hydrophosphination

Diaryl prolinols have been used to catalyze the asymmetric hydrophosphination of α,βunsaturated aldehydes (Scheme 44).64 The origin of high enantioselectivity was investigated using density functional theory (B3LYP/6-311+G(2d,2p)//B3LYP/6-31G(d, p)). The lowest energy iminium intermediate is in the E geometry and is 3.5 kcal/mol lower in energy than the Z isomer (Scheme 45). In agreement with experimental observations, the lowest energy transition structure leads to the S product. The lowest energy transition structure leading to the minor R product is 1.5 kcal/mol higher in energy and also rises from the E iminium. Steric repulsion with the bulky group of the catalyst causes this transition state to be disfavored. The lowest energy transition structure that arises from the Z iminium is 4.2 kcal/mol higher in energy than the S transition state.

Scheme 44.

Asymmetric hydrophosphination reaction

Scheme 45.

B3LYP/6-31G(d, p) iminium ion and transition structure energies. Solvent-corrected values (B3LYP/6-311+G(2d,2p) single point, CPCM, CHCl3) are in parentheses

2.1.9. Michael addition

Domingo and co-workers used B3LYP/6-31G(d, p) to study the role of (S)-5-(pyrrolidin-2-yl)-1H-tetrazole in the Michael addition of (i) acetaldehyde to nitroethylene and (ii) acetone to β-nitrostyrene (Scheme 46).65 For the former reaction, it was found that the enamine isomers formed by condensation of the catalyst with acetaldehyde differ by only 0.8 kcal/mol (Model A, Scheme 47). All possible modes of addition—of the α and β faces of both the anti and syn enamines to both faces of nitroethylene—were calculated. The lowest energy transition structure has an activation barrier of 18.7 kcal/mol and occurs by addition of nitroethylene to the β-face of the anti conformation of the enamine, with a hydrogen bond between the tetrazole hydrogen and an oxygen on the nitro group.

Scheme 46.

Michael addition of nitroalkenes to acetaldehyde and acetone

Scheme 47.

Relative energies of Michael addition

For the latter reaction, four transition structures—addition of both faces of nitrostyrene to the β-face of both the anti and syn enamines—were located (Model B). The four lowest energy transition structures for each mode of attack are shown in Scheme 48. In all four transition structures, an anti arrangement between the phenyl group of nitrostyrene and the enamine C-C double bond, and a gauche arrangement between the enamine and nitrostyrene C-C double bonds are preferred. The configuration of the lowest energy transition structure, TS-anti-re, agrees with the experimentally observed major diastereomer. The stability of this transition structure is attributed to favorable electrostatic interactions between the forming iminium and the nitro group, as well as the tetrazole hydrogen and an oxygen on the nitro group. Seebach proposed this arrangement (topological rule) for the transition states of enamine reactions with nitroalkenes.66 The syn transition structures are approximately 2 kcal/mol higher in energy; the N=O···H-N distances reveal weaker hydrogen bond stabilization.

Scheme 48.

Transition structures and activation energies for addition of acetaldehyde-enamine to nitrostyrene

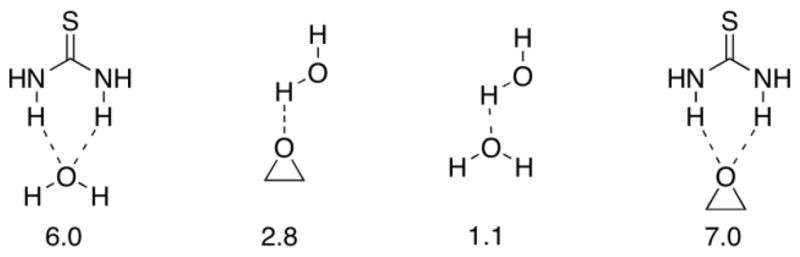

Sunoj used mPW1PW91 and B3LYP to explore the importance of explicit solvation in computing transition structures for the proline-catalyzed Michael addition of 3-pentanone and cyclohexanone to nitrostyrene (Scheme 49).67 Polar protic solvents had experimentally been shown to improve reaction rates and stereoselectivities,68 and calculations without explicit solvent molecules failed to reproduce the experimentally observed stereoselectivities. The experimentally observed major diastereomer could arise from addition of the anti enamine to the re-face of nitrostyrene (TS-anti-re) to give the syn-(S, R) product. However, mPW1PW91/6–311G(d, p)//mPW1PW91/6–31G(d) gas phase calculations predict a stereochemical outcome of 6% de (syn) and 40% ee in favor of the (S, R) product for 3-pentanone, and 32% de (anti) and 97% ee in favor of the (R, R) product for cyclohexanone.

Scheme 49.

Proline-catalyzed addition of 3-pentanone and cyclohexanone to nitrostyrene

With one methanol, calculations still do not fit experiment, but the inclusion of two methanol molecules in a cooperative binding mode results in stereoselectivities that are in good agreement with experimental results. Calculations predict 80% de (syn) and 90% ee (S, R) for 3-pentanone, and 82% de (syn) and 59% ee (S, R) for cyclohexanone. The most favored transition structures for each ketone are shown in Figure 26. Both transition structures involve attack of the anti enamine to the re-face of nitrostyrene, with two methanol molecules bridging the carboxylic acid group of the catalyst and the nitro group of the alkene. The enamine and nitroalkene C-C π bonds are anti to one another.

Figure 26.

Lowest energy transition structures for the proline catalyzed Michael addition of nitrostyrene and cyclohexanone (left) and 3-pentanone (right), with 2 explicit water molecules.

Nájera and co-workers used B3LYP/6-31G(d) to explain the stereoselectivity of the Michael addition reaction of nitroalkenes with 1,2-aminoalcohol-derived prolinamide catalysts (Scheme 50).69

Scheme 50.

Michael addition catalyzed by prolinamide catalysts

The reaction was modeled by 3-pentanone, 1-nitropropene, and a truncated 1,2-aminoalcohol catalyst. Four possible modes of attack—attack of the nitropropene on both the Re- and Si- faces of both the anti- and syn-enamines were calculated (Scheme 51).

Scheme 51.

Possible modes of attack for the Michael addition reaction

In agreement with the experimental results, the lowest energy transition structure (Table 1, TS anti, Re, 15.0 kcal/mol), which occurs via attack of the Re-face of the anti enamine, gives the major (4S,5R)-syn product. The transition structure that gives the minor (4R,5S)-syn enantiomer occurs by attack of the nitroalkene to the Si-face of the anti enamine. The computed energy difference between these two transition structures (1.4 kcal/mol ≈ 80% ee) agrees well with the enantioselectivities obtained experimentally. The syn, re and syn, si transition structures do not have stabilizing hydrogen bond interactions and therefore have higher calculated activation energies.

Table 1.

B3LYP/6-31G(d) activation energies (kcal/mol)

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TS | Eact | Forming C···C | NH···O1 | O3H···O1 | NH···O2 | O3H···O2 |

| TS anti, re | 15.0 | 2.13 | 2.03 | 1.89 | 2.59 | 2.72 |

| TS anti, si | 16.4 | 2.10 | 2.11 | 2.85 | 2.56 | 2.09 |

| TS syn, re | 18.2 | 2.01 | – | – | – | – |

| TS syn, si | 27.6 | 1.95 | – | – | – | – |

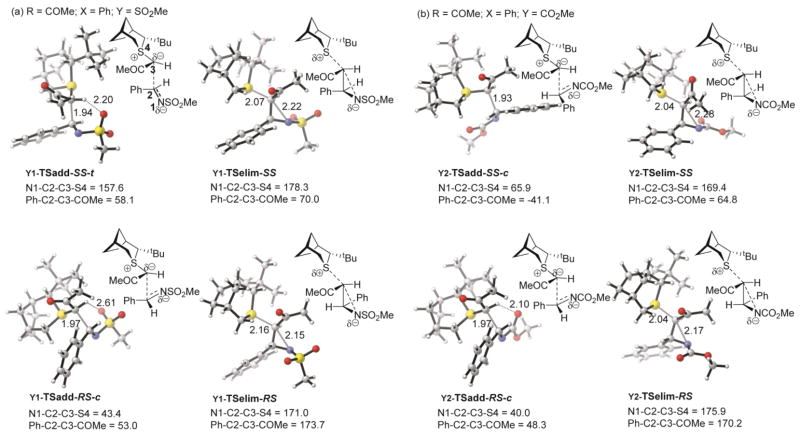

Alexakis and co-workers reported a DFT study of the pyrrolidine-type catalyzed conjugate addition of aldehydes to vinyl sulfone and vinyl phosphonate Michael acceptors (Scheme 52).70 The reaction of 3,3-dimethylisobutyraldehyde and vinyl sulfone was computed. Because the five lowest-energy minima for the enamine formed by the pyrrolidine catalyst and 3,3-dimethylbutyraldehyde are anti, only the transition structures for si-face (“bottom”, major) and re-face (“top”, minor) attack on the anti enamine were considered (Figure 27). In agreement with experiment, si-face attack was calculated to be favored (ΔG‡ = 6.2 kcal/mol). The stereoselectivity is attributed to favorable electrostatic interactions between the sulfone oxygens and enamine nitrogen. Compared to the reactant, the negative charge on each sulfone oxygen increases in the transition state, and these oxygens are stabilized by the developing positive charge on the enamine nitrogen. The minor (re) transition structure was calculated to be significantly higher in energy (ΔG‡ = 13.0 kcal/mol). The sulfone oxygens in the minor transition structure are far from the enamine nitrogen (4.07 Å), and experience steric hindrance with the bulky group of the catalyst.

Scheme 52.

Michael addition reaction of vinyl sulfones

Figure 27.

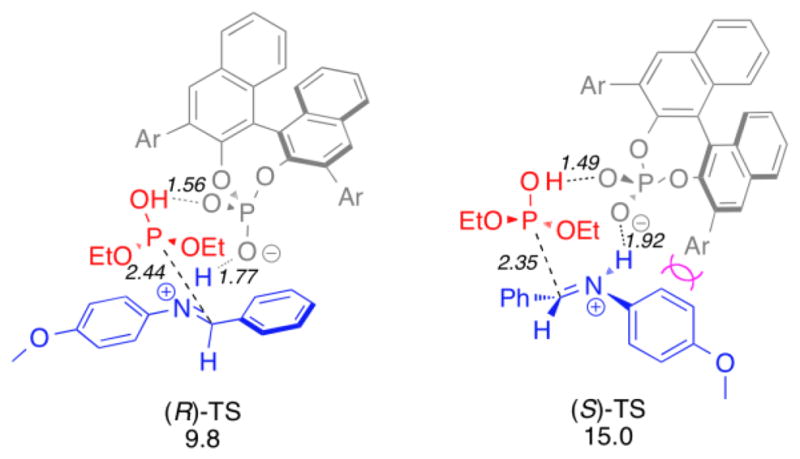

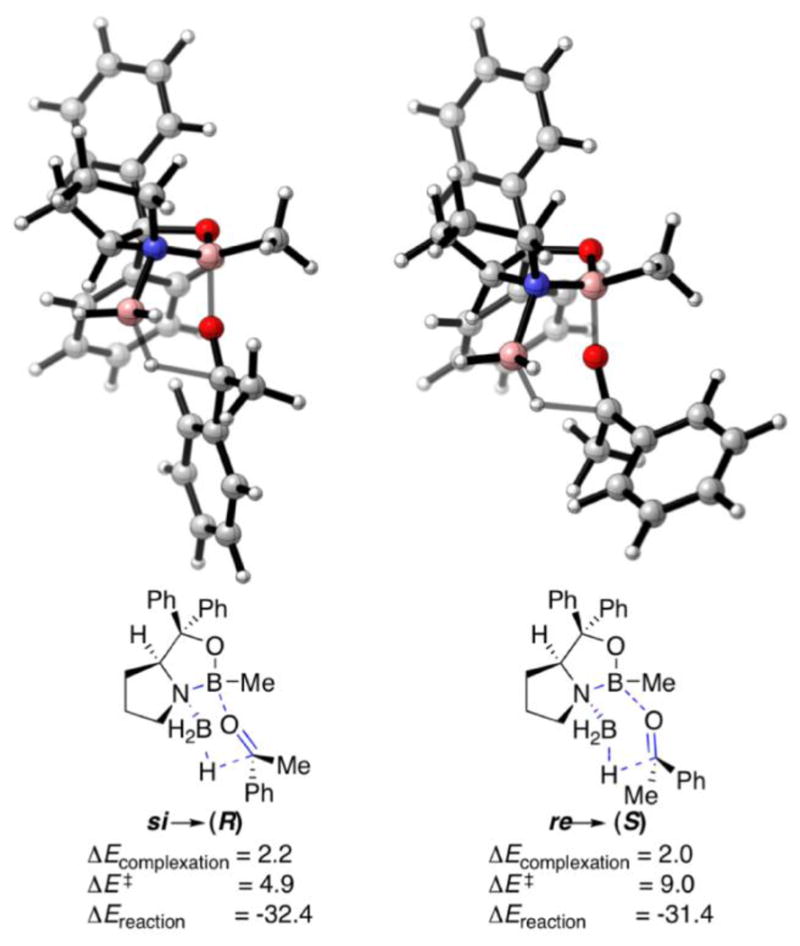

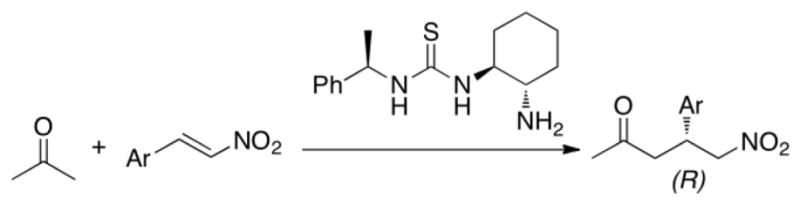

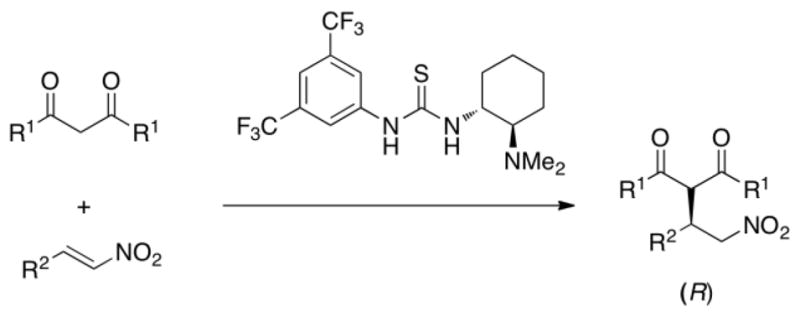

Michael addition transition structures for the addition of 3,3-dimethylisobutyraldehyde to a vinyl disulfone.