Abstract

While the salutary effects of exercise training on conduit artery endothelial cells have been reported in animals and humans with cardiovascular risk factors or disease, whether a healthy endothelium is alterable with exercise training is less certain. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of exercise training on transcriptional profiles in normal endothelial cells using a genome-wide microarray analysis. Brachial and internal mammary endothelial gene expression was compared between a group of healthy pigs that exercise trained for 16–20 wk (n = 8) and a group that remained sedentary (n = 8). We found that a total of 130 genes were upregulated and 84 genes downregulated in brachial artery endothelial cells with exercise training (>1.5-fold and false discovery rate <15%). In contrast, a total of 113 genes were upregulated and 31 genes downregulated in internal mammary artery endothelial cells using the same criteria. Although there was an overlap of 66 genes (59 upregulated and 7 downregulated with exercise training) between the brachial and internal mammary arteries, the identified endothelial gene networks and biological processes influenced by exercise training were distinctly different between the brachial and internal mammary arteries. These data indicate that a healthy endothelium is indeed responsive to exercise training and support the concept that the influence of physical activity on endothelial gene expression is not homogenously distributed throughout the vasculature.

Keywords: chronic exercise, brachial artery, internal mammary artery, endothelial phenotype

there is an increasing amount of evidence that the beneficial effects of exercise training on conduit artery endothelial function are most notable in subject populations with preexisting cardiovascular risk factors/disease and consequent compromised vascular function (36, 39). Conversely, in sedentary but otherwise healthy subjects, whether exercise training further improves endothelial function is debatable (36, 39). In this regard, we (41) recently conducted a retrospective analysis of data collected in our laboratory since 1992 and concluded that in healthy pigs long-term exercise training does not alter brachial and femoral artery vasomotor function. Given the multiplicity of biological functions performed by the endothelium (1, 2), it is tenuous to assume that the lack of a training-induced adaptation in conduit artery vasomotor function implies the absence of an exercise effect on endothelial phenotype.

To address this issue, we recently (41) investigated whether exercise-mediated phenotypic adaptations of endothelial cells could be manifested without concurrent changes in vasomotor function. In that study (41), expression of a select set of genes related to vasomotor function, inflammation, and oxidative stress was measured in endothelial cells from brachial and femoral arteries of healthy exercise-trained and sedentary pigs. In agreement with the vasomotor function data, there were no significant differences in the magnitude of expression for any of the 18 measured proteins (41), thus further suggesting that healthy exercise-trained pigs do not reveal a more atheroprotected endothelial cell phenotype than their sedentary counterparts. While a plausible interpretation of these findings is that when the endothelial phenotype is near optimal levels, as in healthy conduit arteries, changes may not occur as a result of a “ceiling effect,” it is also possible that studies evaluating targeted markers may overlook exercise-responsive genes. Therefore, it remains possible that, with exercise training, a healthy endothelium undergoes molecular changes previously unnoticed that will ultimately result in a protective effect against future cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., aging).

With the motivation to definitively establish whether or not a healthy endothelium is alterable with physical activity, in the present study we adopted a genome-wide microarray analysis to enhance the ability to capture, if existent, the effects of exercise training on conduit artery endothelial gene expression. Specifically, we compared endothelial transcriptional profiles in the brachial and internal mammary arteries between healthy exercise-trained and sedentary pigs. The utilization of cutting-edge bioinformatic techniques enabled us to examine the influence of exercise training on endothelial gene networks and interactions between individual components of networks. In general, we hypothesized that exercise-trained pigs, relative to sedentary pigs, would exhibit altered expression of endothelial cell genes involved in the regulation of vascular health such that between-group differences would be most pronounced in the conduit artery perfusing the working skeletal muscles (i.e., brachial artery).

METHODS

Experimental animals.

Before initiation of the study, approval was received from the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Missouri. The experimental animals were adult male Yucatan miniature swine (n =16) that were purchased from a commercial breeder (Sinclair Research Farm, Columbia, MO). The pigs were 10–12 mo of age and weighed 25–40 kg at time of purchase. All pigs were housed in the animal care facility in the Department of Biomedical Sciences at the University of Missouri in a room maintained at 20–23°C with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle. Pigs were provided a standard diet (1,050 g/day of Purina Lab Mini-pig Chow) in which 8% of daily caloric intake was derived from fat.

Treadmill exercise training program.

All pigs were familiarized with running on a motorized treadmill and then randomly assigned to either an exercise (EX; n = 8) or sedentary (SED; n = 8) group. The exercise group completed a 16- to 20-wk endurance-training program as described previously (40). Briefly, intensity and duration of exercise bouts increased steadily so that by week 10 of training the pigs ran on the treadmill 85 min/day, 5 days/wk. The 85-min training bouts consisted of a 5-min warm-up, a 15-min sprint run at 6–8 mph, a 60-min endurance run at 4–6 mph, and a 5-min cool down. Pigs assigned to the sedentary group were restricted to their enclosures (1 × 1.6 meter pens) and did not exercise. Our laboratory (41, 48) has comprehensively established that this training program elicits the expected adaptations in exercise endurance and skeletal muscle oxidative capacity. For confirmation purposes, at the conclusion of the exercise training program, pigs performed a graded intensity treadmill exercise test to exhaustion. Furthermore, at time of death samples were taken from the 1) medial head of triceps brachii, 2) long head of triceps brachii, 3) lateral head of triceps brachii, 4) accessory head of triceps brachii, and 5) deltoid muscles. Muscles samples were frozen and stored at −80°C until processed. Citrate synthase activity was measured from whole muscle homogenate using the spectrophotometric method of Srere (45).

Tissue sampling.

After completion of the exercise intervention or sedentary confinement, and ∼24 h following the last exercise bout, pigs were sedated with ketamine (25 mg/kg im) and Rompun (2.25 mg/kg im). Pigs were then anesthetized with phentobarbital sodium (20 mg/kg iv), intubated and ventilated with room air, and euthanized by removal of the heart in full compliance with the American Veterinary Medical Association Guidelines on Euthanasia. Immediately following death, the brachial and internal mammary arteries were harvested, rinsed with ice-cold Krebs saline, and stored in 10 vol of a cold RNA-stabilizing agent (RNAlater; Ambion, Austin, TX). On the same day as death, and while remaining wetted with the RNAlater solution, arteries were dissected clean of excess adventitia, opened with one full-length longitudinal cut through the vessel wall, and laid open, lumen side up. Excess solution was gently blotted away with a clean kimwipe, and the vessel's luminal surface was covered with a minimal volume of TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH). After 30 s of incubation, the endothelium was gently scraped with a sterile scalpel blade. The remainder of a 1-ml volume of TRI Reagent was pipetted across the lumen surface, and the wash/endothelial cell slurry was collected into a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube. Each sample was passed through a 20-gauge needle attached to a plastic syringe 10 times to ensure a homogenous lysate. This method of scraping the luminal surface yields an endothelial enriched sample, as demonstrated by us (41) and others (12, 27, 42). Isolation of total RNA was performed for each sample per the TRI Reagent manufacturer's protocol (Ambion). Total RNA purification via the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) was performed per manufacturer's protocol. Product was eluted in a 26-μl volume with a 2-μl aliquot being used for spectrophotometric quantification. Twenty-five nanograms of each sample were used in an Experion StdSens RNA analysis to confirm concentration and quality of RNA. The RNA quality of three samples (1 EX brachial, 1 SED brachial, and 1 SED internal mammary) was not optimal, and therefore they were excluded from the microarray and quantitative real-time PCR analysis. This resulted in 7 EX vs. 7 SED animals for comparisons within the brachial artery and 8 EX vs. 7 SED animals for comparisons within the internal mammary artery. Our rationale for selecting the brachial and internal mammary arteries was that we desired to evaluate the effects of exercise training on endothelial gene expression in arteries that perfuse active skeletal muscles (brachial artery) and arteries that perfuse metabolically less active tissues (internal mammary artery) during exercise. Furthermore, in humans, the brachial artery is the vessel of choice for assessment of endothelial function (i.e., flow-mediated dilation; Refs. 11, 46), while the internal mammary artery is also of special interest given its resistance to atherosclerosis and frequent use in coronary bypass surgeries.

Microarray analysis.

Porcine tissue total RNA (0.5 μg) was used to make the biotin-labeled antisense RNA (aRNA) target using the MessageAmp Premier RNA amplification kit (Ambion) by following the manufacturer's procedures. Briefly, the total RNA was reverse transcribed to first-strand cDNA with a oligo(dT) primer bearing a 5′-T7 promoter using ArrayScript reverse transcriptase. The first-strand cDNA then underwent second-strand synthesis to convert into double-stranded cDNA template for in vitro transcription. The biotin-labeled aRNA was synthesized using T7 RNA transcriptase with biotin-NTP mix. After purification, the aRNA was fragmented in 1× fragmentation buffer at 94°C for 35 min. One-hundred thirty microliters of hybridization solution containing 50 ng/μl of fragmented aRNA were hybridized to the porcine genome array genechip (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) at 45°C for 20 h. After hybridization, the chips were washed and stained with R-phycoerythrin-streptavidin on Affymetrix Fluidics Station 450 using fluidics protocol Midi_euk2v3-450. The microarrays were then scanned and data were acquired using an Afflymetrix GeneChip Scanner 3000 driven by GCOS 1.2 software (Afflymetrix). All raw microarray data (29 arrays from 15 unique animals) have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository, which can be publicly accessed at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/. The data are MIAME compliant, and the GEO accession number is GSE26663.

Quantitative real-time PCR.

To verify the microarray results, four brachial artery endothelial genes found to be altered with exercise training were selected. Selection of genes was based on an initial preliminary analysis of the brachial artery microarray data as well as on optimized primer sequence availability in the literature. Primer sequences for these genes are presented in Table 1. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from total RNA (same RNA extract used for microarray) by reverse transcription using SuperScript III first-strand synthesis system kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacturer's recommended protocol. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed as previously described (43) using the ABI PRISM 7000 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Primers for each target were purchased from IDT (Coralville, IA). A 25-μl reaction mixture containing 20 μl of Power SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) and the appropriate concentrations of gene-specific primers plus 5 μl of cDNA template were loaded in each well of a 96-well plate (duplicate samples). PCR was performed with thermal conditions as follows: 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. A dissociation curve analysis was performed after each run to verify the identity of the PCR products. Before running the RT-PCR experiments, all primers were validated by running a standard curve of 10-fold cDNA dilutions on an endothelial sample for which we had abundance of total RNA. All dilution-cycle threshold (Ct) curves exhibited linearity (all R2 > 0.99) and acceptable slopes (3.2–3.9) for this dilution series. All samples were tested within the amplification range for which the primers were tested. Average Cts across all samples (EX and SED combined) were (means ± SE) as follows: SERPINE2 = 27.5 ± 0.4, PRLR = 26.8 ± 0.3, IL-6 = 25.3 ± 0.4, THBS1 = 22.8 ± 0.3, and GAPDH = 18.6 ± 0.3. Swine GAPDH primers (53) were used to amplify the endogenous control product. The comparative Ct (2−ΔΔCt) method was utilized to calculate expression of each target gene. Our laboratory (52) has established that GAPDH is a suitable housekeeping gene for RT-PCR when examining porcine endothelial gene expression. In the present study, GAPDH threshold cycles were not different between exercise-trained and sedentary pigs (18.4 ± 0.2 vs. 18.7 ± 0.5, respectively; P = 0.63). Furthermore, microarray analysis indicated the absence of a training effect on GAPDH mRNA. It should also be noted that based on the microarray analysis, there were no differences between exercise-trained and sedentary pigs on other common housekeeping genes (e.g., β-actin and 18S), hence supporting the utility of these genes for internal normalization purposes in exercise training and endothelial gene expression studies.

Table 1.

Forward and reverse primer sequences for quantitative real-time PCR

| Gene | Primer Sequence (5′→3′) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| SERPINE2 | (20) | |

| Forward | CGG ACG GCA GGA CCA A | |

| Reverse | GCC ACT GTC ACA ATG TCT TTA TTC TT | |

| PRLR | (51) | |

| Forward | CGC CGC TTT GCT GGA A | |

| Reverse | GCC AGT CTC GGT GGT TTT TG | |

| IL-6 | (38) | |

| Forward | GCG CAG CCT TGA GGA TTT C | |

| Reverse | CCC AGC TAC ATT ATC CGA ATG G | |

| THBS1 | (23) | |

| Forward | CCC ATC ATG CCC TGC TCT AA | |

| Reverse | CCA GCC ATC GTC AGC AGA GT | |

| GAPDH | (53) | |

| Forward | GGG CAT GAA CCA TGA GAA GT | |

| Reverse | GTC TTC TGG GTG GCA GTG AT |

Statistical analysis.

The primary analysis of microarray gene expression data was conducted using the Linear Models for Microarray Data (limma) package (21) and the affy package (19), available through the Bioconductor project (22) for use with R statistical software. Data quality was examined via an extensive battery of metrics obtained using the affyQCReport package. Within affy, quantile normalization was used for between-chip normalization and RMA for background adjustment. For summarizing probe set measurements, median polish and PM-only probes were used. After normalization, nonspecific filtering was carried out on control probe sets and probe sets with little to no variability across all chips [interquartile range < median interquartile range (IQR)] were excluded from further statistical analyses to reduce false positives, as they contain very little information content relative to the analysis at hand. After this preprocessing was completed, the statistical analysis was performed using an empirical Bayesian moderated t-test (44) applied to normalized intensity for each gene, where the exercise group was compared with the sedentary group. The comparisons are expressed as fold changes (EX/SED) along with nominal (unadjusted) and adjusted P values. Adjustment to the P values was made to account for multiple testing using the false discovery rate (FDR) method of Benjamini and Hochberg (7). We chose 15% as our FDR-cutoff for declaring statistical significance and a threshold of ≥1.5-fold (up or down) for declaring a biologically significant change in expression. The 1.5-fold cutoff is commonly used in studies of this nature, and, objectively, it is neither too liberal nor conservative in assisting the P value in weeding out errors (8). Because of the sparseness of the direct annotations with the Affymetrix porcine array, we built a custom annotation package for the array using annotations provided through ANEXdb annotations (http://www.anexdb.org/), which is described in detail by Couture et al. (14). To our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive source of annotations of the porcine genechip array (24,123 genes). Briefly, it is based around the Iowa Porcine Assembly, which is a novel assembly of ∼1.6 million unique porcine-expressed sequence reads annotated through homolog sequence alignment to NCBI RefSeq. The result is a very dense annotation of the porcine-specific probe sets (94%), of which 80% are linked to an NCBI RefSeq entry.

Gene ontology (GO) analyses were subsequently carried out on the gene list to assess the association between Gene Ontology Consortium categories (4) and differentially expressed genes between EX and SED groups. We defined the gene universe for the analysis as follows. We began with all probe sets on the array that had been analyzed for differential expression but also that had both an Entrez gene identifier (35) and a GO annotation, as provided by GO.db (10) annotation maps. For probes that mapped to the same Entrez identifier, a single probe was chosen to ensure a surjective map from probe IDs to GO categories (via Entrez identifiers). This was necessary to avoid redundantly counting GO categories, which increases false positives. Probes with the largest IQR were chosen to be associated with an Entrez identifier. With the use of this gene universe, GOstats (17) was used to carry out conditional hypergeometric tests. These tests exploit the hierarchical nature of the relationships among the GO terms for conditioning (3). We carried out GO analyses for overrepresentation of biological process (BP), molecular function (MF), and cellular component (CC) ontologies, and computed the nominal hypergeometric probability for each GO category. These results were used to assess whether the number of selected genes associated with a given term was larger than expected, and the α-level was 0.05. For the remainder of the data, independent t-tests were used to compare exercise-trained vs. sedentary groups. The α-level was set at 0.05.

Networks were generated through the use of Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (Ingenuity Systems: www.ingenuity.com), henceforth IPA. The full list of all ANEXdb-annotated microarray results were uploaded into IPA with Entrez GeneID, fold change, and adjusted P value. Since the porcine array is not included in IPA as a reference set, we used the full contents of the array as a “user dataset”; therefore, it was essential to include all genes represented on the array, not just those there were significant or even those that were just “present” (i.e., detected) in the samples. Therefore, the reference set consisted of 24,043 genes (out of 24,123 on the array) that mapped to its corresponding object in the Ingenuity Knowledge Base (IKB). In the case of duplicate mapped IDs, the median values (fold change and adjusted P value) were used to represent the single results for that object. Genes that were not detected, or those that were filtered out based on IQR (as previously described), were assigned a fold change of 1 and an adjusted P value of 1. A 1.5-fold cutoff and an adjusted P value <15% were set to identify molecules whose expression was significantly differentially regulated, which IPA terms as Network Eligible Molecules (NEMs). Our networks were built using only knowledge obtained from human data (or uncategorized chemicals) and experimentally observed relationships. To construct the networks, NEMs were overlaid onto a global molecular network developed from information contained in the IKB. Networks of NEMs were then algorithmically generated to maximize their specific connectivity with each other relative to all molecules they are connected to in the IKB, where the NEMs served as “seeds” for generating networks. Additional molecules were recruited to merge smaller networks into successively larger networks by using the default IPA network maximum size of 35 molecules.

Networks were then scored based on the number of NEMs they contained, so that the higher the score, the lower the probability of finding the observed number of NEMs in a given network by random chance. Specifically, the score is the negative log10 of the P value from Fisher's exact test applied to a given network. For example, a score of 9 for a network implies a 1-in-a-billion chance of obtaining a network containing at least the same number of NEMs by chance when randomly picking 35 molecules from the IKB. For a detailed description of the network generating algorithm, see Calvano et al. (9).

Graphical representations of the networks were generated using IPA's Path Designer, which illustrates the molecular relationships between molecules. Molecules are represented as nodes, and the biological relationship between two nodes is represented as an edge (connecting line). All edges are supported by ≥1 reference from the literature, from a textbook, or from canonical information stored in the IKB. These are rich, high information content graphics, with full details included in the figure legends and captions.

RESULTS

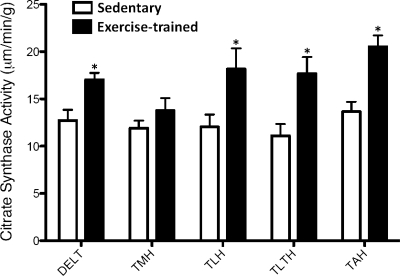

Following the 16- to 20-wk intervention, body weight (EX = 44.1 ± 1.1, SED = 46.0 ± 3.2 kg; means ± SE), total plasma cholesterol (EX = 56.2 ± 5.0, SED = 45.0 ± 6.1 mg/dl), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (EX = 29.6 ± 4.9, SED = 22.6 ± 4.3 mg/dl), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (EX = 26.7 ± 1.8, SED = 22.4 ± 1.7 mg/dl) were not different between exercise and sedentary pigs (P > 0.05). Triglycerides, although within a healthy range, were higher (P < 0.05) in exercise-trained (68 ± 7.5 mg/dl) compared with sedentary pigs (38.6 ± 5.8 mg/dl). This difference was not affected by dietary intake as both groups of pigs were provided with the same diet. Following the intervention, exercise-trained pigs increased endurance time on the treadmill by ∼20% (pre = 27 ± 1, posttraining = 32 ± 1 min; Δ = 5 ± 1 min; P = 0.002) and revealed lower heart rates during rest (pre = 92 ± 5, posttraining = 64 ± 3 beats/min; Δ = 28 ± 4 beats/min; P < 0.001) and submaximal exercise (pre = 197 ± 7, posttraining=139 ± 8 beats/min; Δ = 59 ± 10 beats/min; P < 0.001). In addition, exercise training was associated with increased citrate synthase activity of the deltoid muscle and the long, lateral and accessory head of the triceps brachii muscle (Fig. 1; P < 0.05). Together, these data confirm that pigs in the exercise group exhibited the classic training-induced adaptations.

Fig. 1.

Exercise training was associated with increased citrate synthase activity in forelimb skeletal muscles (sedentary group, n = 8; exercise-trained group, n = 8). Values are means ± SE. DELT, deltoid; TMH, triceps brachii medial head; TLH, triceps brachii long head; TLTH, triceps brachii lateral head; TAH, triceps brachii accessory head. *P < 0.05 vs. sedentary.

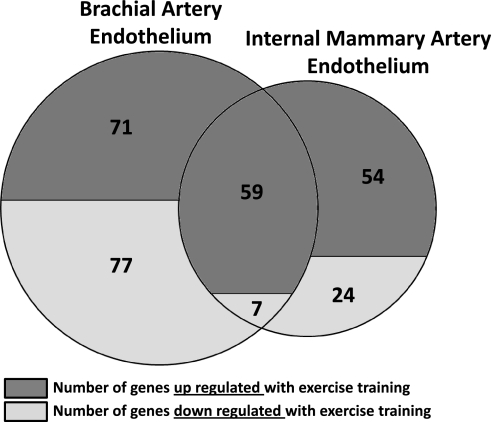

As depicted in Fig. 2, a total of 130 genes were upregulated and 84 genes downregulated in brachial artery endothelial cells with exercise training (>1.5-fold and FDR <15%). In contrast, a total of 113 genes were upregulated and 31 genes downregulated in internal mammary endothelial cells using the same criteria. The effects of exercise training produced an overlap of 66 genes between the brachial and internal mammary arteries, and the direction of change for those genes was the same in both arteries (59 upregulated and 7 downregulated with exercise training; Fig. 3). For brevity, Tables 2 and 3 provide the list of significant annotated probe sets with twofold (or greater) between-group differences in brachial and internal mammary artery endothelial gene expression. The full list of all significant probe sets along with their fold change is available in Supplemental Data (Supplemental Material for this article is available online at the Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol website). Furthermore, GO analyses for overrepresentation of biological process, molecular function, and cellular component ontologies are also available in Supplemental Data. Of interest, 79 and 52 biological processes were altered with exercise training in the brachial and internal mammary arteries, respectively. Tables 4 and 5 summarize the top 10 biological processes based on the estimated odds ratio of a differentially expressed gene being associated with a process.

Fig. 2.

Impact of exercise training on endothelial transcriptional profiles in healthy swine.

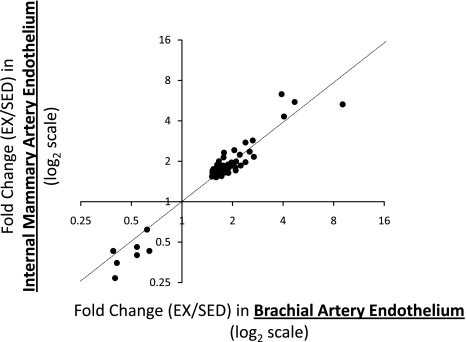

Fig. 3.

Between-artery correlation in changes of gene expression induced by exercise training. Effects of exercise training produced an overlap of 66 genes between the brachial and internal mammary arteries. Each dot represents a gene. As illustrated, the direction of change for those genes was the same in both arteries (59 upregulated and 7 downregulated with exercise training). Dotted line depicts perfect agreement. EX/SED, exercise/sedentary.

Table 2.

List of annotated probe sets with twofold or greater difference in brachial artery endothelial gene expression between exercise-trained and sedentary pigs

| ID | Gene Symbol | Gene Title | Adjusted P Value | Fold Change (EX/SED) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EX > SED in brachial artery | ||||

| Ssc.90.1.S1_at | CHI3L1 | Chitinase 3-like 1 (cartilage glycoprotein-39) | 0.05 | 4.69 |

| Ssc.16342.1.A1_at | SERPINE2 | Serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade E (nexin, plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1), member 2 | <0.01 | 4.05 |

| Ssc.13645.1.A1_at | SCG2 | Secretogranin II | 0.01 | 3.92 |

| Ssc.29372.1.A1_at | PLCXD3 | Phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C, X domain containing 3 | 0.05 | 2.81 |

| Ssc.3693.1.S1_at | SERPINB7 | Serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade B (ovalbumin), member 7 | 0.01 | 2.75 |

| Ssc.28515.1.S1_at | USP2 | Ubiquitin specific peptidase 2 | 0.05 | 2.68 |

| Ssc.24638.1.S1_at | PRLR | Prolactin receptor | 0.03 | 2.64 |

| Ssc.7106.1.S1_at | CDO1 | Cysteine dioxygenase, type I | 0.01 | 2.53 |

| Ssc.7338.1.A1_at | ARSJ | Arylsulfatase family, member J | 0.04 | 2.39 |

| Ssc.6932.1.A1_at | DPP10 | Dipeptidyl-peptidase 10 (nonfunctional) | 0.03 | 2.39 |

| Ssc.30334.1.A1_at | CYP3A4 | Cytochrome P450, family 3, subfamily A, polypeptide 4 | 0.05 | 2.27 |

| Ssc.62.2.S1_a_at | IL6 | Interleukin 6 (interferon, beta 2) | 0.03 | 2.25 |

| Ssc.28084.1.A1_at | KIF26B | Kinesin family member 26B | 0.03 | 2.24 |

| Ssc.14477.1.S1_at | CILP | Cartilage intermediate layer protein, nucleotide pyrophosphohydrolase | 0.07 | 2.21 |

| Ssc.5837.1.S1_at | DBP | D site of albumin promoter (albumin D-box) binding protein | 0.02 | 2.10 |

| Ssc.1312.1.S1_at | TMEM25 | Transmembrane protein 25 | 0.03 | 2.09 |

| Ssc.26326.1.S1_at | CYP3A4 | Cytochrome P450, family 3, subfamily A, polypeptide 4 | 0.14 | 2.08 |

| Ssc.10462.1.S1_at | CAPSL | Calcyphosine-like | 0.06 | 2.05 |

| EX < SED in brachial artery | ||||

| Ssc.29575.1.A1_at | VNN2 | Vanin 2 | 0.01 | 0.29 |

| Ssc.4114.1.A1_at | MARCH3 | Membrane-associated ring finger (C3HC4) 3 | 0.03 | 0.31 |

| Ssc.8868.1.S1_at | FCGR2C | Fc fragment of IgG, low affinity IIc, receptor for (CD32) (gene/pseudogene) | 0.01 | 0.34 |

| Ssc.2033.1.S1_at | CRY1 | Cryptochrome 1 (photolyase-like) | <0.01 | 0.39 |

| Ssc.25227.1.S1_at | ARNTL | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator-like | 0.10 | 0.41 |

| Ssc.28686.1.S1_at | SPOCK1 | Sparc/osteonectin, cwcv, and kazal-like domains proteoglycan (testican) 1 | 0.07 | 0.43 |

| Ssc.25458.1.S1_at | SPOCK1 | Sparc/osteonectin, cwcv, and kazal-like domains proteoglycan (testican) 1 | 0.04 | 0.44 |

| Ssc.167.2.S1_a_at | FCGR3A | Fc fragment of IgG, low affinity IIIa, receptor (CD16a) | 0.02 | 0.45 |

| Ssc.15296.1.S1_at | CD53 | CD53 molecule | 0.03 | 0.48 |

| Ssc.17821.1.A1_at | PLEK | Pleckstrin | 0.04 | 0.50 |

Data are for exercise-trained (EX; n = 7) and sedentary (SED; n = 7) pigs. Gene symbols that are italicized indicate overlap with internal mammary artery. All genes in table have a false discovery rated (FDR) adjusted P value (also called a q value) of ≤15% to account for multiple testing.

Table 3.

List of annotated probe sets with twofold or greater difference in internal mammary artery endothelial gene expression between exercise-trained and sedentary pigs

| ID | Gene Symbol | Gene Title | Adjusted P Value | Fold Change (EX/SED) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EX > SED in internal mammary artery | ||||

| Ssc.13645.1.A1_at | SCG2 | Secretogranin II | 0.01 | 6.32 |

| Ssc.90.1.S1_at | CHI3L1 | Chitinase 3-like 1 (cartilage glycoprotein-39) | 0.11 | 5.53 |

| Ssc.16342.1.A1_at | SERPINE2 | Serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade E (nexin, plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1), member 2 | 0.01 | 4.31 |

| Ssc.24638.1.S1_at | PRLR | Prolactin receptor | 0.01 | 2.86 |

| Ssc.8162.1.S1_at | PTX3 | Pentraxin 3, long | 0.14 | 2.77 |

| Ssc.6932.1.A1_at | DPP10 | Dipeptidyl-peptidase 10 (nonfunctional) | 0.07 | 2.76 |

| Ssc.12584.1.A1_at | CD79B | CD79b molecule, immunoglobulin-associated beta | 0.10 | 2.76 |

| Ssc.10462.1.S1_at | CAPSL | Calcyphosine-like | 0.05 | 2.42 |

| Ssc.7106.1.S1_at | CDO1 | Cysteine dioxygenase, type I | 0.09 | 2.36 |

| Ssc.12171.1.A1_at | FAM13A | Family with sequence similarity 13, member A | 0.06 | 2.32 |

| Ssc.14477.1.S1_at | CILP | Cartilage intermediate layer protein, nucleotide pyrophosphohydrolase | 0.13 | 2.24 |

| Ssc.5663.1.S1_at | VCAN | Versican | 0.10 | 2.17 |

| Ssc.28515.1.S1_at | USP2 | Ubiquitin specific peptidase 2 | 0.08 | 2.16 |

| Ssc.5663.2.S1_at | VCAN | Versican | 0.07 | 2.16 |

| Ssc.10127.1.A1_at | ATP2B2 | ATPase, Ca2+ transporting, plasma membrane 2 | 0.10 | 2.14 |

| Ssc.14506.1.S1_at | TOP2A | Topoisomerase (DNA) II alpha 170 kDa | 0.10 | 2.10 |

| Ssc.25241.1.S1_at | ATP2B2 | ATPase, Ca2+ transporting, plasma membrane 2 | 0.08 | 2.00 |

| EX < SED in internal mammary artery | ||||

| Ssc.21272.1.A1_at | SEMA5A | Sema domain, seven thrombospondin repeats (type 1 and type 1-like), transmembrane domain (TM), and short cytoplasmic domain, (semaphorin) 5A | 0.14 | 0.26 |

| Ssc.25227.1.S1_at | ARNTL | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator-like | 0.10 | 0.35 |

| Ssc.22436.1.S1_at | CYP26B1 | Cytochrome P450, family 26, subfamily B, polypeptide 1 | 0.05 | 0.39 |

| Ssc.4747.1.S1_at | FST | Follistatin | 0.13 | 0.43 |

| Ssc.2033.1.S1_at | CRY1 | Cryptochrome 1 (photolyase-like) | 0.02 | 0.43 |

| Ssc.9957.1.A1_at | CCL8 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 8 | 0.12 | 0.44 |

| Ssc.14379.1.A1_at | SLC38A1 | Solute carrier family 38, member 1 | 0.14 | 0.45 |

| Ssc.3282.1.S1_at | NR2F1 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 2, group F, member 1 | 0.10 | 0.47 |

| Ssc.28782.1.A1_at | SLC38A1 | Solute carrier family 38, member 1 | 0.15 | 0.48 |

Data are for EX (n = 7) and SED (n = 7) pigs. Gene symbols that are italicized indicate overlap with brachial artery. All genes in table have an FDR adjusted P value (also called a q value) of ≤15% to account for multiple testing.

Table 4.

List of top 10 biological processes affected by exercise training in brachial artery endothelium

| Odds Ratio | P Value | Count | Size | Term | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10.81 | <0.01 | 5 | 21 | Cholesterol biosynthetic process | CYP51A11.58, DHCR241.91, SCAP1.84, IDI11.58, LSS1.7, CYP51A11.57 |

| 7.8 | <0.01 | 9 | 50 | Steroid biosynthetic process | ADM0.52, CYP51A11.58, DHCR241.91, SCAP1.84, IDI11.58, LSS1.7, PRLR1.57, SC5DL2.64, CYP7B11.55, ADM0.61 |

| 7.63 | <0.01 | 4 | 22 | Circadian rhythm | CRY10.39, ARNTL0.41, BHLHE410.64, CYP7B11.74, CRY10.61 |

| 7.22 | <0.01 | 4 | 23 | Activation of plasma proteins involved in acute inflammatory response | A2M0.58, C1QA0.61, C1QB0.55, C1QC0.57 |

| 6.53 | 0.01 | 4 | 25 | Negative regulation of hydrolase activity | DHCR241.91, FKBP1B1.84, PLEK1.77, TGFB20.5, DHCR241.59 |

| 5.97 | <0.01 | 7 | 48 | Sterol metabolic process | CYP51A11.58, DHCR241.91, SCAP1.84, IDI11.58, LSS1.7, SC5DL1.57, CYP7B11.55, CYP51A10.61 |

| 4.82 | 0.01 | 5 | 41 | Humoral immune response | BLNK0.51, IL62.25, C1QA0.61, C1QB0.55, C1QC0.57 |

| 4.73 | <0.01 | 6 | 50 | Response to glucocorticoid stimulus | CDO12.53, ADM0.52, A2M0.58, IL62.25, C1QB0.55, CCNE11.54 |

| 4.62 | <0.01 | 6 | 51 | Cell cycle arrest | GADD45A0.53, DHCR241.91, AIF11.84, PLAGL10.66, MAP2K60.65, TGFB21.77, GADD45A1.59 |

| 4.62 | <0.01 | 6 | 51 | Leukocyte migration | ADORA11.55, IL62.25, ITGB20.65, ROCK10.54, TGFB21.59, SCG23.92 |

Selection of top 10 biological processes was based on odds ratio. To minimize the influence of pathway size on odds ratio, only pathways >10 genes and those with 4 or more altered genes were considered. Superscripts indicate fold change (EX/SED).

Table 5.

List of top 10 biological processes affected by exercise training in internal mammary artery endothelium

| Odds Ratio | P Value | Count | Size | Term | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12.38 | <0.01 | 6 | 39 | DNA packaging | NAP1L21.79, NUSAP11.51, NCAPG1.63, TOP2A2.1, HIST1H2BO1.59, HIST1H2BK1.63 |

| 4.37 | 0.01 | 5 | 81 | Regulation of hormone levels | FST0.43, ADRA2A1.65, FKBP1B1.71, CYP26B10.39, PTGS11.71 |

| 3.97 | 0.02 | 4 | 70 | Calcium ion transport | ADRA2A1.65, FKBP1B1.71, ATP2B22.14, CCL82, ADRA2A1.59, FKBP1B0.44 |

| 3.49 | 0.03 | 4 | 79 | Positive regulation of locomotion | ADRA2A1.65, IGF11.68, IL161.66, SCG21.63, ADRA2A1.66, IGF16.32 |

| 3.44 | 0.04 | 4 | 80 | Chemotaxis | IL161.66, ENPP21.54, CCL80.44, SCG26.32 |

| 3.4 | 0.02 | 5 | 107 | Cell migration | IL161.66, NR2F10.47, TGFBR30.64, VAV20.59, SCG2 6.32 |

| 3.31 | 0.04 | 4 | 83 | Di-, tri-valent inorganic cation transport | ADRA2A1.65, FKBP1B1.71, ATP2B22.14, CCL82, ADRA2A1.59, FKBP1B0.44 |

| 3.17 | 0.02 | 6 | 132 | Secretion by cell | FST0.43, ADRA2A1.65, FKBP1B .71, PTGS11.71, CCL80.44, SCG26.32 |

| 3.08 | 0.03 | 5 | 112 | Regulation of catabolic process | ADRA2A1.65, IGF11.68, ARNTL1.66, RAP1GAP1.63, TIMP30.35, ADRA2A1.78, IGF11.58, ARNTL1.53 |

| 3.06 | <0.01 | 10 | 237 | Localization of cell | ADRA2A1.65, IGF11.68, IL161.66, ENPP21.63, SERPINE21.66, NR2F11.54, TGFBR34.31, VAV20.47, SCG20.64, CHRD0.59, ADRA2A6.32, IGF11.66 |

Selection of top 10 biological processes was based on odds ratio. To minimize the influence of pathway size on odds ratio, only pathways >10 genes and those with 4 or more altered genes were considered. Superscripts indicate fold change (EX/SED).

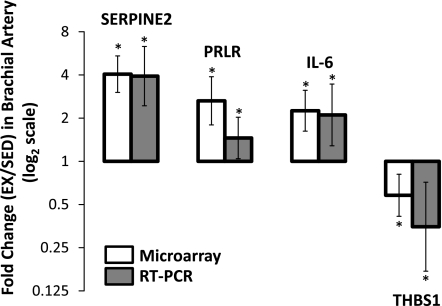

Quantitative real-time PCR was carried out on four brachial artery endothelial cell genes altered with exercise training. As illustrated in Fig. 4, microarray and real-time PCR produced the same results for all four genes, hence substantiating the findings obtained by the microarray experiments and analysis.

Fig. 4.

Verification of microarray results by quantitative real-time PCR in a subset of brachial artery genes. Error bars indicate 95% confidence limits. *P < 0.05, significantly different between exercise-trained and sedentary pigs.

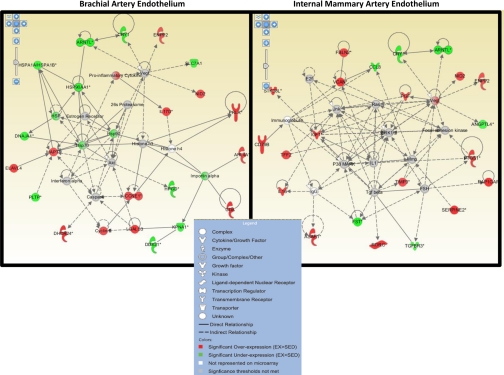

Figure 5 illustrates the top-scoring and highly significant gene networks influenced by exercise training in the brachial and internal mammary artery. The scores for the top gene networks in the brachial and internal mammary arteries were 35 and 47, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Top-scoring (and highly significant) gene networks influenced by exercise training in the brachial (left; score = 35) and internal mammary (right; score = 47) artery. Nodes represent genes/molecules, with their shape denoting the functional class of the molecule product (see legend inset). Molecules in red are those that are upregulated and molecules in green are those that are downregulated with exercise training, whereas molecules in gray are unchanged in expression but are members of the network. White molecules denote network members that were not represented on the array.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to evaluate the impact of exercise training on endothelial transcriptional profiles in large animals with the use of genome-wide microarray analysis. Endothelial samples were obtained from the brachial and internal mammary arteries of healthy exercise-trained and sedentary pigs, the best nonprimate model for human cardiovascular research (15). We demonstrated that exercise training altered expression of 214 endothelial cell genes from the brachial and 144 genes from the internal mammary artery with an overlap of 66 genes between vessels.

The emergence of the field of “exercise vascular cell biology” (30) during the past decade has been of paramount importance for our understanding of the cardiovascular effects of exercise. Initial and current molecular studies in the field of exercise vascular cell biology primarily consist of descriptive work examining expression of single genes and/or proteins following exercise interventions. This discipline is rapidly evolving, and more mechanistic approaches are also undertaken to test the involvement of genes of interest with the application of gene knockout and overexpression models (28). While these reductionist approaches have represented a crucial forward step towards our understanding of the impact of physical activity on vascular cells, it is important to recognize that, by nature, they are insufficient to provide us with a wide appreciation of the complex molecular effects of exercise. As a result, there is a need to move toward more holistic and integrative molecular approaches (26).

Herein, we utilized cutting-edge molecular and bioinformatic techniques to study the influence of exercise training on endothelial transcriptional profiles and gene networks. Specifically, microarray experiments were performed on brachial and internal mammary endothelial samples to identify genes that are differentially expressed with exercise training. In addition, relations between the differentially expressed genes were assessed by IPA. This program allows the unbiased construction of gene (product) networks of interacting molecules by connecting all possible differentially expressed genes and hub molecules (molecules of which the expression remains unchanged; Ref. 26). Figure 5 illustrates the top endothelial gene networks influenced by exercise training in the brachial and internal mammary arteries. Although five molecules were common to the top two networks (ARNTL, CRY1, NID2, ENPP2, and VEGF), there are important differences apparent between the brachial and internal mammary artery top networks. First, the reduction in HSP90 gene expression at the brachial artery with exercise training was a surprise. It has been reported that the binding of HSP90 to endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) in endothelial cells enhances the activation of eNOS, thus contributing to the maintenance of nitric oxide bioavailability and vascular homeostasis (18). Given previous results of no effect of exercise training on vasomotor reactivity in brachial arteries from healthy pigs (41), it appears that decreased HSP90 mRNA does not result in decreased HSP90 protein and/or reduced nitric oxide bioavailability in the brachial arteries of Yucatan pigs. More expectedly, in the internal mammary artery, VEGF appeared to be marginally involved in the top gene network altered by exercise training. These results support the recent report (6) in humans that serum concentrations of VEGF are positively correlated with endothelial function of the internal mammary artery following exercise training. However, we are unaware of evidence for changes in VEGF in serum from exercise-trained Yucatan pigs. Perhaps of greater interest, these results provide evidence that the effect of exercise training on endothelial gene expression was different between brachial and internal mammary arteries. This interpretation is further supported when considering that a relatively small portion of the genes affected by exercise training overlapped between both arteries (Fig. 2). More strikingly, according to the GO analysis, the top 10 biological processes influenced by exercise diverged between brachial and internal mammary arteries. For example, the greatest effects of exercise training on the endothelium of the brachial artery appeared to be related to cholesterol and steroid biosynthetic processes (Table 4), whereas the main effects of exercise on the internal mammary artery endothelium involved pathways linked to DNA packaging and regulation of hormone levels (Table 5).

This is not the first study to demonstrate that exercise training produces a heterogeneous effect on gene expression across the vasculature. For instance, previous research has documented that exercise training increases eNOS protein content nonuniformly throughout the coronary arterial tree (32) and skeletal muscle vascular beds (33, 37). The differential effect of exercise on expression of endothelial cell genes is particularly important when considering that study conclusions are frequently founded on experiments only interrogating a single vessel. In this regard, caution is necessary in extrapolation of outcomes on exercise effects from one vasculature to another.

Our findings that the effect of exercise training on endothelial gene expression is vessel dependent suggest that exercise-induced signals and/or downstream endothelial responses to a given signal differ between vasculatures. For example, a possible explanation for the differential effect of exercise on gene expression between the brachial and internal mammary artery may be related to the distinct magnitudes of blood flow, and presumably shear stress, to which these arteries are exposed during the exercise bouts. While we are unaware of any studies that have compared brachial and internal mammary hemodynamics during exercise, it is reasonable to deduce that a conduit vessel perfusing the working (forelimb) skeletal muscles (31) (i.e., brachial artery) is subjected to markedly greater levels of shear than the internal mammary artery that prefuses tissues that are metabolically less active (5). To our surprise, however, only 1 of the 28 brachial artery endothelial genes (SERPINE2) that were markedly altered by exercise (>2-fold; Table 2) was considered shear responsive in a recent endothelial cell culture and microarray study by Conway et al. (13). Given the strong evidence indicating that exercise training produces enlargement of conduit arteries perfusing active muscle (16, 24), it is possible that outward remodeling may have caused expression of shear stress-responsive genes to return back to sedentary levels. In this regard, it is currently proposed that the endothelial adaptations in skeletal muscle arteries are training duration dependent. That is, improvements in conduit artery endothelial function are observed during the initial weeks (∼2 wk) and as the exercise-training regimen progresses, function becomes normalized (49, 50), possibly as a result of the arterial remodeling (29, 47).

It should be noted that while this is the first study to utilize microarray analysis to examine the effects of exercise training on endothelial cells using a large animal model, Maeda et al. (34) were pioneers in employing microarray analysis techniques to study vascular adaptations to training. In a study in rats, the authors evaluated the effects of a 4-wk treadmill running intervention on abdominal aorta (whole vessel) gene expression and found that 206 genes were upregulated and 117 downregulated with exercise training, which represents a similar distribution to that found in our study (Fig. 2). In addition, our study is not the first to examine the effects of exercise training on gene expression in the internal mammary artery. In a classic study by Hambrecht et al. (25), the authors reported that exercise produced increased protein content for eNOS, phospho-eNOS-Ser, Akt, and phospho-Akt in the internal mammary artery (whole vessel) of patients with stable coronary artery disease (25). Exercise did not alter expression levels of these genes in our study. These combined observations suggest that the eNOS and Akt pathways in the internal mammary artery may only be responsive to the effect of exercise training when endothelial impairment or disease is present. It is important to recognize, however, that eNOS and Akt are mainly regulated by phosphorylation and to a lesser extent by their protein and mRNA expression levels, hence possibly explaining at least part of the differences between these two studies.

In summary, this is the first study to evaluate the impact of the exercise-trained state on endothelial transcriptional profiles in the brachial and internal mammary arteries of swine using a whole genome microarray approach. We demonstrated that, in healthy exercise-trained pigs, expression of endothelial cell genes in conduit arteries is different than that in arteries from sedentary pigs. While we do not have evidence that these exercise-induced changes in mRNA can be extrapolated to the protein level, our data suggest that a healthy endothelium is indeed responsive to exercise training. Most importantly, these data support the concept that the influence of physical activity on endothelial gene expression is not homogenously distributed throughout the vasculature. Future research should establish whether endothelial gene networks affected by exercise in healthy arteries are altered in the presence of cardiovascular risk factors or disease. In addition, further characterization of the function and regulation of the exercise-responsive genes will be critical to advance our understanding in exercise vascular cell biology.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the expert technical assistance of Miles Tanner, Stacy Barr, David Harah, Pam Thorne, Ann Melloh, Diederik Kuster, and Dr. Mingyi Zhou. This study was supported by American Heart Association Grant AHA 11POST5080002 (to J. Padilla), National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Grant T32-AR-048523 (to G. H. Simmons), and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant P01-HL-052490 (to M. H. Laughlin, D. K. Bowles, and M. T. Hamilton).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aird WC. Endothelial cell heterogeneity and atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep 8: 69–75, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aird WC. Spatial and temporal dynamics of the endothelium. J Thromb Haemost 3: 1392–1406, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexa A, Rahnenfuhrer J, Lengauer T. Improved scoring of functional groups from gene expression data by decorrelating GO graph structure. Bioinformatics 22: 1600–1607, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, Harris MA, Hill DP, Issel-Tarver L, Kasarskis A, Lewis S, Matese JC, Richardson JE, Ringwald M, Rubin GM, Sherlock G. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet 25: 25–29, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barone R. (Editor). Anatomie Comparee des Mammiferes Domestiques. Paris: Vigot; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beck EB, Erbs S, Mobius-Winkle S, Adams V, Woitek FJ, Walther T, Hambrecht R, Mohr FW, Stumvoll M, Bluher M, Schuler G, Linke A. Exercise training restores the endothelial response to vascular growth factors in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2011. March 22 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Stat Soc Ser B 57: 289–300, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bey L, Akunuri N, Zhao P, Hoffman EP, Hamilton DG, Hamilton MT. Patterns of global gene expression in rat skeletal muscle during unloading and low-intensity ambulatory activity. Physiol Genomics 13: 157–167, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calvano SE, Xiao W, Richards DR, Felciano RM, Baker HV, Cho RJ, Chen RO, Brownstein BH, Cobb JP, Tschoeke SK, Miller-Graziano C, Moldawer LL, Mindrinos MN, Davis RW, Tompkins RG, Lowry SF. A network-based analysis of systemic inflammation in humans. Nature 437: 1032–1037, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlson M, Falcon S, Pages H, Li N. GO.db: A Set Of Annotation Maps Describing The Entire Gene Ontology. 2.2.2. Rpv [Google Scholar]

- 11.Celermajer DS, Sorensen KE, Gooch VM, Spiegelhalter DJ, Miller OI, Sullivan ID, Lloyd JK, Deanfield JE. Non-invasive detection of endothelial dysfunction in children and adults at risk of atherosclerosis. Lancet 340: 1111–1115, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Civelek M, Manduchi E, Riley RJ, Stoeckert CJ, Jr, Davies PF. Chronic endoplasmic reticulum stress activates unfolded protein reponse in arterial endothelium in regions of suceptibility to atherosclerosis. Circ Res 105: 453–461, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conway DE, Williams MR, Eskin SG, McIntire LV. Endothelial cell responses to atheroprone flow are driven by two separate flow components, low time-average shear stress and fluid flow reversal. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H367–H374, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Couture O, Callenberg K, Koul N, Pandit S, Younes R, Hu Z, Dekkers J, Reecy J, Honavar V, Tuggle C. ANEXdb: an integrated animal ANnotation and microarray EXpression database. Mamm Genome 20: 768–777, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Critser JK, Laughlin MH, Prather RS, Riley LK. Proceedings of the Conference on Swine in Biomedical Research. ILAR J 50: 89–94, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dinenno FA, Tanaka H, Monahan KD, Clevenger CM, Eskurza I, DeSouza CA, Seals DR. Regular endurance exercise induces expansive arterial remodelling in the trained limbs of healthy men. J Physiol 534: 287–295, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Falcon S, Gentleman R. Using GOstats to test gene lists for GO term association. Bioinformatics 23: 257–258, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia-Cardena G, Fan R, Shah V, Sorrentino R, Cirino G, Papapetropoulos A, Sessa WC. Dynamic activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by Hsp90. Nature 392: 821–824, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gautier L, Cope L, Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA. affy-analysis of Affymetrix GeneGhip data at the probe level. Bioinformatics 20: 307–315, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geeraert B, DeKeyzer D, Davey PC, Crombe F, Benhabiles N, Holvoet P. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced expression of ABCA1 in blood monocytes precedes coronary atherosclerosis and is associated with plaque complexity in hypercholesterolemic pigs. J Thromb Haemost 5: 2529–2536, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gentleman R, Huber W, Carey VJ, Irizarry RA, Dudoit S. Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions Using R and Bioconductor. New York: Springer, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, Ellis B, Gautier L, Ge Y, Gentry J, Hornik K, Hothorn T, Huber W, Iacus S, Irizarry R, Leisch F, Li C, Maechler M, Rossini AJ, Sawitzki G, Smith C, Smyth G, Tierney L, Yang JY, Zhang J. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol 5: R80, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grado-Ahuir JA, Aad PY, Ranzenigo G, Caloni F, Cremonesi F, Spicer LJ. Microarray analysis of insulin-like growth factor-I-induced changes in messenger ribonucleic acid expression in cultured porcine granulosa cells: possible role of insulin-like growth factor-I in angiogenesis. J Anim Sci 87: 1921–1933, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green DJ, Swart A, Exterkate A, Naylor LH, Black MA, Cable NT, Thijssen DHJ. Impact of age, sex and exercise on brachial and popliteal artery remodelling in humans. Atherosclerosis 210: 525–530, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hambrecht R, Adams V, Erbs S, Linke A, Krankel N, Shu Y, Baither Y, Gielen S, Thiele H, Gummert JF, Mohr FW, Schuler G. Regular physical activity improves endothelial function in patients with coronary artery disease by increasing phosphorylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation 107: 3152–3158, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuster DWD, Merkus D, vanderVelden J, Verhoeven AJM, Duncker DJ. “Integrative Physiology 2.0”: integration of systems biology into physiology and its application to cardiovascular homeostasis. J Physiol 589: 1037–1045, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.LaMack JA, Himburg HA, Friedman MH. Distinct profiles of endothelial gene expression in hyperpermeable regions of the porcine aortic arch and thoracic aorta. Atherosclerosis 195: e35–e41, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lauer T, HeiBCPreik M, Balzer J, Hafner D, Strauer BD, Kelm M. Reduction of peripheral flow reserve impairs endothelial function in conduit arteries of patients with essential hypertension. J Hypertens 23: 563–569, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laughlin MH. Endothelium-mediated control of coronary vascular tone after chronic exercise training. Med Sci Sports Exerc 27: 1135–1144, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laughlin MH, Joseph B. Wolfe Memorial Lecture. Physical activity in prevention and treatment of coronary disease: the battle line is in exercise vascular cell biology. Med Sci Sports Exer 36: 352–362, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laughlin MH, Klabunde RE, Delp MD, Armstrong RB. Effects of dipyridamole on muscle blood flow in exercising miniature swine. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 257: H1507–H1515, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laughlin MH, Pollock JS, Amann JF, Hollis ML, Woodman CR, Price EM. Training induces nonuniform increases in eNOS content along the coronary arterial tree. J Appl Physiol 90: 501–510, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laughlin MH, Woodman CR, Schrage WG, Gute D, Price EM. Interval sprint training enhances endothelial function and eNOS content in some arteries that perfuse white gastrocnemius muscle. J Appl Physiol 96: 233–244, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maeda S, Iemitsu M, Miyauchi T, Kuno S, Matsuda M, Tanaka H. Aortic stiffness and aerobic exercise: mechanistic insight from microarray analyses. Med Sci Sports Exerc 37: 1710–1716, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maglott D, Ostell J, Pruitt KD, Tatusova T. Entrez gene: gene-centered information at NCBI. Nucleic Acids Res 35: D26–D31, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maiorana A, O'Driscoll G, Taylor R, Green D. Exercise and the nitric oxide vasodilator system. Sports Med 33: 1013–1035, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McAllister RM, Jasperse JL, Laughlin MH. Nonuniform effects of endurance exercise training on vasodilation in rat skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol 98: 753–761, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miguel JC, Chen J, VanAlstine WG, Johnson RW. Expression of inflammatory cytokines and Toll-like receptors in the brain and respiratory tract of pigs infected with porcinereproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 135: 314–319, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moyna NM, Thompson PD. The effect of physical activity on endothelial function in man. Acta Physiol Scand 180: 113–123, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muller JM, Meyers PR, Laughlin MH. Vasodilator responses of coronary resistance arteries of exercise-trained pigs. Circulation 89: 2308–2314, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Padilla J, Newcomer SC, Simmons GH, Kreutzer KV, Laughlin MH. Long-term exercise training does not alter brachial and femoral artery vasomotor function and endothelial phenotype in healthy pigs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 299: H379–H385, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Passerini AG, Polacek DC, Shi C, Francesco NM, Manduchi E, Grant GR, Pritchard WF, Powell S, Chang GY, Stoeckert CJ, Jr, Davies PF. Coexisting proinflammatory and antioxidative endothleial transcription profiles in a disturbed flow region of the adult porcine aorta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 2482–2487, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roseguini BT, Soylu M, Whyte JJ, Yang HT, Newcomer SC, Laughlin MH. Intermittent pneumatic leg compressions acutely upregulate VEGF and MCP-1 expression in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H1991–H2000, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol 3: article 3, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Srere PA. Citrate synthase. Methods Enzymol 13: 3–5, 1969 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thijssen DHJ, Black MA, Pyke KE, Padilla J, Atkinson G, Harris RA, Parker B, Widlansky ME, Tschakovsky ME, Green DJ. Assessment of flow-mediated dilation in humans: a methodological and physiological guideline. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300: H2–H12, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thijssen DHJ, Maiorana AJ, O'Driscoll G, Cable NT, Hopman MTE, Green DJ. Impact of inactivity and exercise on the vasculature in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol 108: 845–875, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thompson MA, Henderson KK, Woodman CR, Turk JR, Rush JWE, Price EM, Laughlin MH. Exercise preserves endothelium-dependent relaxation in coronary arteries of hypercholesterolemic male pigs. J Appl Physiol 96: 1114–1126, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tinken TM, Thijssen DHJ, Black MA, Cable NT, Green DJ. Time course of change in vasodilator function and capacity in response to exercise training in humans. J Physiol 586: 5003–5012, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tinken TM, Thijssen DHJ, Hopkins N, Dawson EA, Cable NT, Green DJ. Shear stress mediates endothelial adaptations to exercise training in humans. Hypertension 55: 312–318, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trott JF, Horigan KC, Gloviczki JM, Costa KM, Freking BA, Farmer C, Hayashi K, Spencer T, Morabito JE, Hovey RC. Tissue-specific regulation of porcine prolactin receptor expression by estrogen, progesterone, and prolactin. J Endocrinol 202: 153–166, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Whyte JJ, Samuel M, Mahan E, Padilla J, Simmons GH, Arce-Esquivel AA, Bender SB, Whitworth KM, Hao YH, Murphy CN, Walters EM, Prather RS, Laughlin MH. Vascular endothelium-specific overexpression of human catalase in cloned pigs. Transgenic Res 2010. December 18 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhu XY, Rodriguez-Porcel M, Bentley MD, Chade AR, Sica V, Napoli C, Cplice N, Ritman EL, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Antioxidant intervention attenuates myocardial neovascularization in hypercholesterolemia. Circulation 109: 2109–2115, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]