Abstract

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is a leading risk factor for a variety of cardiovascular diseases including coronary heart disease and atherosclerosis. Exercise training (ET) has a beneficial effect on these disorders, but the basis for this effect is not fully understood. This study was designed to investigate whether the ET abates endothelial dysfunction in the aorta in T2D. Heterozygous controls (m Leprdb) and type 2 diabetic mice (db/db; Leprdb) were either exercise entrained by forced treadmill exercise or remained sedentary for 10 wk. Ex vivo functional assessment of aortic rings showed that ET restored acetylcholine-induced endothelial-dependent vasodilation of diabetic mice. Although the protein expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase did not increase, ET reduced both IFN-γ and superoxide production by inhibiting gp91phox protein levels. In addition, ET increased the expression of adiponectin (APN) and the antioxidant enzyme, SOD-1. To investigate whether these beneficial effects of ET are APN dependent, we used adiponectin knockout (APNKO) mice. Indeed, impaired endothelial-dependent vasodilation occurred in APNKO mice, suggesting that APN plays a central role in prevention of endothelial dysfunction. APNKO mice also showed increased protein expression of IFN-γ, gp91phox, and nitrotyrosine but protein expression of SOD-1 and -3 were comparable between wild-type and APNKO. These findings in the aorta imply that APN suppresses inflammation and oxidative stress in the aorta, but not SOD-1 and -3. Thus ET improves endothelial function in the aorta in T2D via both APN-dependent and independent pathways. This improvement is due to the effects of ET in inhibiting inflammation and oxidative stress (APN-dependent) as well as in improving antioxidant enzyme (APN-independent) performance in T2D.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, inflammation, superoxide, vascular biology

type 2 diabetes (T2D) is associated with impairment in endothelial function characterized by impaired endothelial-dependent vasodilation, increased inflammatory cell, and platelet adhesion in both rodents and humans (22, 32, 41, 42, 54). Accumulating evidence suggests that endothelial dysfunction is an early stage of atherosclerosis (11, 41). Thus endothelial dysfunction with inflammatory cell and platelet adhesion may contribute to the development of atherosclerosis in T2D. Even though the mechanisms responsible for endothelial dysfunction are not fully elucidated, previous studies indicate that a decrease in nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability may play a central role in endothelial dysfunction in T2D (32, 36, 54).

In addition, oxidative stress and chronic inflammation are important pathogenic factors in many diseases including T2D and cardiovascular diseases (CVD) such as stroke, coronary artery disease, and atherosclerosis (8, 19, 28, 32). Previous studies indicated that reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide (O2·−) readily react with NO to form peroxynitrate (ONOO−), which results in decreased NO bioavailability (8, 10, 32, 47). Oxidative stress is tightly regulated by a balance between production and removal facilitated by enzymatic activity in the healthy condition, whereas cell damage induced by excessive oxidative stress can contribute to diabetes-induced atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease (8, 9). Other potential triggers for endothelial dysfunction involve proinflammatory cytokines (10, 50). Proinflammatory cytokines impair endothelial function in animal models and in isolated human veins (3, 10, 33). Previous studies show that insulin resistance and T2D are associated with increased proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 as well as decreased plasma adiponectin (APN) (8, 15, 35, 54). We hypothesize that exercise training (ET) improves endothelial function in the diabetic aorta by suppressing oxidative stress and inflammatory process thereby increasing NO bioavailability.

METHODS

Animals.

The procedures were approved by the Laboratory Animal Care Committee at the University of Missouri-Columbia. Male heterozygous control mice (5 wk old; Con; m Leprdb; background strain: C57BLKS/J) and homozygous type 2 diabetic mice (db/db; Leprdb; background strain: C57BLKS/J) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory and were housed in animal facility conditioned with 12-h:12-h light/dark cycles and allowed free access to normal chow and water. Control and db/db mice were randomly divided into exercise training (ET) and sedentary (Sed) groups. All ET and Sed animals were euthanized at the age of 16- to 17 wk old. In addition, male adiponectin knockout mice (APNKO) or their age-matched wild-type (WT) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. Mice were 16–18 wk of age at the time of the experiments. Body weights and nonfasting blood glucose levels with commercial One Touch UltraSmart glucometer (Lifescan, Milpitas, CA) were recorded on a weekly basis.

Exercise performance test.

Exercise performance testing followed the methods of Massett and Berk (29) with minor modification. Briefly, all mice were acclimatized to run on a motorized rodent treadmill with an electric grid at the rear of the treadmill (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH) over 2 days before conducting an exercise performance test. Acclimation runs were 15 min in duration with a treadmill incline of 0°. Treadmill speed was 10 m/min on day 1 and 12 m/min on the day 2. For the performance test, mice were placed on the treadmill and allowed to adapt to the surroundings for 3–5 min before starting. The treadmill was started at a speed of 8.5 m/min with a 0° incline. After 5 min, the speed was raised to 10 m/min. Speed was then increased by 2.5 m/min every 3 min to a maximum of 30 m/min. Exercise continued until exhaustion, defined as an inability to maintain running speed despite repeated contact with the electric grid and air blow. Each such exhausted mouse was immediately removed from the treadmill when exhaustion was determined and returned to its home cage. This protocol was repeated 9 wk after completion of the training period to access the efficacy of the training regime.

Exercise training.

Mice assigned to the exercise group were exposed to 10 wk of training consisting of treadmill running 5 days/wk, 60 min/day at a final intensity equivalent to ∼50% of VO2Max attained during the exercise performance test (27, 29). To allow for animal acclimatization, exercise intensity was gradually increased over the first 4 wk to reach a target of 1 h of daily exercise at a speed of 10 m/min (db/db) and 13 m/min (Con). A daily 60-min exercise consisted of a 10-min warm-up, a 45-min run, and a 5-min cool down.

Functional assessment of the aorta.

Under anesthesia, aortae were rapidly excised and rinsed in cold physiological saline solution (PSS) containing (in mM) 118.99 NaCl, 4.69 KCl, 1.18 KH2PO4, 1.17 MgSO4·7H2O, 2.50 CaCl2·2H2O, 14.9 NaHCO3, 5.5 d-Glucose, and 0.03 EDTA. Fat and connective tissue surrounding aortae were carefully removed using small forceps and spring scissors. Aortae were maintained in PSS in 95% O2-5% CO2 at 37°C for the entire experiment. 2 mm of aortic rings were isometrically mounted in a myograph (model 610M; DMT, Denmark). After a 15-min equilibration period, an optimal passive tension (15 mN) was applied followed by another 30 min of equilibration. Aortic rings were precontracted with 1 μmol/l phenylephrine (PE). A dose-response curve was obtained by cumulative addition of endothelial-dependent vasodilator, ACh (1 nmol/l to 10 μmol/l), and endothelial-independent vasodilator, sodium nitroprusside (SNP; 1 nmol/l to 10 μmol/l). Relaxation at each concentration was measured and expressed as the percentage of force generated in response to PE. The contributions of NO and superoxide to vasorelaxation were assessed by incubating the vessels with NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME; NO synthases inhibitor; 100 μmol/l, 20 min) and hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidinyloxy (TEMPOL: a membrane-permeable superoxide dismutase mimetic, 3 mmol/l, 60 min), respectively (12, 54).

Western blot analyses.

For Western blot analysis, aortae were separately homogenized and sonicated in 200 μl lysis buffer (Cellytic MT Mammalian Tissue Lysis/Extraction Reagent; Sigma) with protease and phosphotase inhibitors (Sigma) at 1:100 ratios, respectively. Protein concentrations were assessed with BCA protein assay kit (Pierce). Equal amounts of protein (5 μg or 10 μg) were separated by 12% or 7.5% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF or nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad). Endothelial NO synthase (eNOS), SOD-1, SOD-3 APN, IFN-γ, gp91phox, nitrotyrosine, and β-actin (β-actin) protein expressions were detected by Western blot analysis with the use of eNOS primary antibody (Santa Cruz; 1:200), SOD-1 primary antibody (Calbiochem; 1:1,000), SOD-3 primary antibody (Stressgen; 1:1,000), APN primary antibody (R&D; 1:1,000), IFN-γ primary antibody (Millipore; 1:500), gp91phox primary antibody (BD; 1:1,000), nitrotyrosine (Abcam; 1:500), and β-actin antibody (Abcam; 1:2,000). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were accordingly used. Signals were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Bio-Rad) and scanned with a Fuji LAS 3000 densitometer. The relative amounts of protein expression were quantified and normalized to those of the corresponding internal reference, β-actin, and then normalized to corresponding WT or Con mice, which were set to a value of 1.0.

ELISA assay of serum insulin and APN.

Blood was obtained from the vena cava after anesthesia with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg ip). A whole blood sample was held for 30 min at room temperature to allow clotting. The sample was then centrifuged at 2,000–3,000 g for 10 min at 4°C; the serum was transferred in separate tubes without disturbing blood clots and stored at −80°C until analysis. The serum insulin and APN levels were measured with commercial kits (Alpco diagnostics and Millipore, respectively) using spectrophotometry according to company protocol. Insulin resistance was determined by using homeostasis assessment model (HOMA-IR) (52). HOMA-IR used the following formula: HOMA-IR = fasting glucose (mmol/l) × fasting insulin (mU/l)/22.5.

Insulin tolerance test.

The tail tip was cut horizontally with sterile scissors and baseline blood glucose was measured using OneTouch Ultramini glucometer (Lifescan). Diluted insulin (porcine pancreas; 1 unit/kg body wt; Sigma) was injected into the intraperitoneal cavity after overnight fasting. Blood glucose was sampled from the tail of each mouse at 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min by gently massaging a small drop of blood onto the glucometer strip.

Citrate synthase activity.

To see the effect of ET, soleus muscles were harvested from mice hindlimb, and citrate synthase activity was measured by citrate synthase assay kit (Sigma; CS0720) according to company protocol.

Data analysis.

All values are presented as means ± SE. Between-group differences in body weight, glucose, HOMA-IR, insulin, citrate synthase activity, and relative protein content were assessed by one-way ANOVA using SPSS17. Insulin tolerance test and concentration-response curves were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with repeated measures. For WT and APNKO experiment, t-test was used. Statistical differences were considered significant at the P < 0.05 probability level.

RESULTS

General characteristics of mice.

Soleus muscle citrate synthase activity, as an indicator of oxidative capacity and of mitochondrial density and function, was increased by ET in Con and db/db mice, confirming the efficacy of the ET regimen (Table. 1). Body weight of db/db mice was significantly greater than that of Con mice. Exercise did not lower the body weight of either Con or db/db mice. Blood glucose (nonfasting) and serum insulin of db/db mice was significantly greater than that found in Con + Sed mice. Exercise lowered these parameters although they did not reduce to levels found in Con + Sed mice. Insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) of db/db mice was significantly greater than that of Con + Sed mice; exercise lowered HOMA-IR in db/db mice but not significantly (P = 0.123) owing to large variations between mice.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of Con and db/db mice

| Con + Sed | Con + ET | db/db + Sed | db/db + ET | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 |

| Body mass, g | 28.55 ± 0.86 | 26.76 ± 0.76 | 51.03 ± 0.85* | 49.84 ± 0.55* |

| Nonfasting glucose, mg/ml | 213.33 ± 3.13 | 179.83 ± 8.84 | 577.50 ± 12.87* | 446.20 ± 49.79*† |

| Fasting HOMA-IR | 0.44 ± 0.04 | 0.71 ± 0.28 | 189.82 ± 43.43* | 129.04 ± 22.80* |

| Fasting insulin, ng/ml | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.06 | 8.67 ± 1.12* | 5.45 ± 0.72* |

| Citrate synthase activity units, μmol·ml−1·min−1 | 134.99 ± 3.71 | 159.50 ± 5.77*† | 133.85 ± 5.83 | 164.11 ± 10.46*† |

Values are means ± SE. ET, exercise training; HOMA-IR, homeostasis assessment model-insulin resistance.

P < 0.05 vs. control (Con) + sedentary (Sed);

P < 0.05 vs. diabetic (db/db) + Sed.

Exercise partially ameliorated insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes.

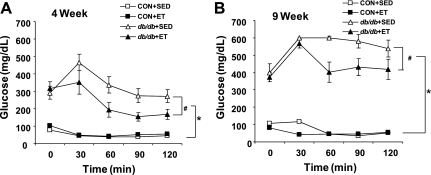

We examined the effects of ET on diabetes-induced insulin resistance in Con and db/db at both 4 wk and 9 wk post-ET. As expected, db/db mice showed severe insulin resistance when compared with Con mice. Exercise improved impaired insulin sensitivity of db/db compared with sedentary db/db but not sufficiently to reach the levels observed in the control mice (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Insulin tolerance test. Insulin tolerance test was performed after 4 wk (A) and 9 wk (B) treadmill exercise training. Insulin (1 unit/kg) was intraperitoneally injected after an overnight fast (n = 5 to 6). ET, exercise training. *P < 0.01 vs. control mice (Con) + sedentary (Sed); #P < 0.05 vs. diabetic mice (db/db) + Sed.

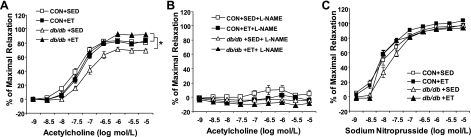

Exercise improved aortic endothelial function in type 2 diabetes.

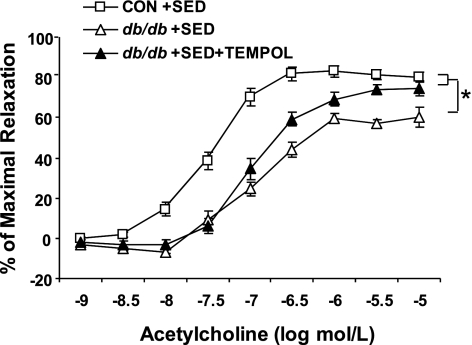

Isolated aortic rings from Con and db/db in all treatments dilated in a dose-dependent manner to endothelial-dependent and endothelial-independent agonists (ACh and SNP, respectively). ACh-induced vasodilation was significantly impaired in the db/db + Sed compared with the Con + Sed (Fig. 2A). Exercise improved ACh-induced dilation in db/db aorta, such that ACh-induced dilation was significantly greater in db/db + ET aorta than in db/db + Sed aorta (Fig. 2A). In addition, ACh-induced vasodilation of db/db + ET aorta was not different from those of Con + Sed and Con + ET aortae (Fig. 2A). ACh-induced vasodilation was completely inhibited by l-NAME (Fig. 2B) in all groups. This suggests that relaxation to ACh is dependent on NO. To determine whether antioxidants restore ACh-induced dilation in a manner similar to exercise, experiments were conducted with and without TEMPOL, a cell-permeable SOD mimetic. In the absence of TEMPOL, the response to ACh was significantly attenuated in the db/db + Sed aorta compared with Con + Sed aorta. TEMPOL partially restored ACh-induced vasodilation in the db/db + Sed control (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

A: ACh-induced dilation in isolated aortae from Con (m Leprdb) and db/db (Leprdb) mice without (Sed) and with 10 wk ET. Endothelial-dependent vasorelaxation to ACh was significantly impaired from aortae of db/db + Sed. ET restored impaired vasorelaxation in db/db but did not improve vasorelaxation in Con. B: NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME; 100 μmol/l, 20 min) inhibited vasorelaxation to ACh. C: endothelial-independent vasorelaxation was not significantly different among groups. Each mouse aorta generated 1 to 2 rings (n = 6–10 rings/group). *P < 0.05 vs. db/db + Sed.

Fig. 3.

Endothelial-dependent vasorelaxation to ACh was significantly impaired from aortae of db/db + Sed compared with Con + Sed. Hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidinyloxy (TEMPOL; a superoxide dismutase mimetic) partially restored impaired vasorelaxation in db/db + Sed. Each mouse aorta generated 2 rings (n = 8 rings/group). *P < 0.05 vs. db/db + Sed.

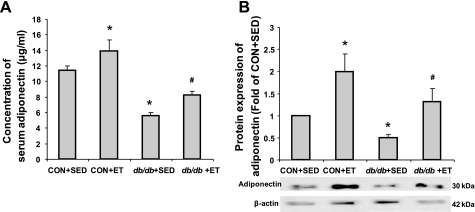

Exercise increased serum and protein expression of APN in the aorta.

Protein expression of APN was examined in the serum and in isolated aortae from trained and sedentary Con and db/db mice. Serum and protein expression of APN were significantly decreased in db/db compared with Con. Exercise elevated serum and protein expression of APN in both Con and db/db (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The role of ET in adiponectin expression in serum and aorta. A: protein expression of serum adiponectin showed significantly lower expression in db/db + Sed compared with Con + Sed. However, ET increased adiponectin expression in both Con and db/db (n = 4 to 5). B: protein expression of adiponectin from aortae showed a similar pattern to that seen in the serum (n = 5). *P < 0.05 vs. Con + Sed; #P < 0.05 vs. db/db + Sed.

eNOS, IFN-γ, SOD-1, and gp91phox protein expressions in the aorta.

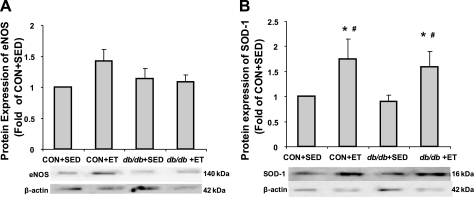

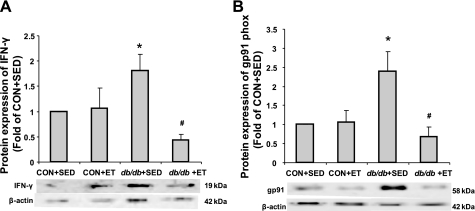

The protein levels of eNOS and SOD-1 were not significantly altered by diabetes status. Exercise did not alter eNOS protein content, whereas it increased SOD-1 protein expression in aortae of both Con and db/db (Fig. 5, A and B). The proinflammatory cytokine, IFN-γ, was markedly increased in db/db, and ET decreased IFN-γ levels (Fig. 6A). Protein expression of gp91phox, a NAD(P)H oxidase subunit, was markedly increased in db/db, but ET decreased protein expression of gp91phox in the aorta (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 5.

Protein expressions of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and SOD-1. A: protein levels of eNOS were not altered by diabetes status. ET did not increase protein expression of eNOS in either Con or db/db (n = 5). B: protein levels of SOD-1 were not changed by diabetes status. However, ET increased SOD-1 protein expression in both Con and db/db mice (n = 6). *P < 0.05 vs. Con + Sed; #P < 0.05 vs. db/db + Sed.

Fig. 6.

Protein expressions of INF-γ and gp91phox (gp91). A: proinflammatory cytokine, INF-γ protein expression significantly increased in db/db aorta compared with Con. ET decreased INF-γ only in db/db, but not in control mice (n = 4). B: NAD(P)H oxidase subunit, gp91phox protein expression significantly increased in db/db aorta compared with Con but ET decreased protein expression of gp91phox (n = 5). *P < 0.05 vs. Con + Sed; #P < 0.05 vs. db/db + Sed.

Deficiency of APN induced endothelial dysfunction.

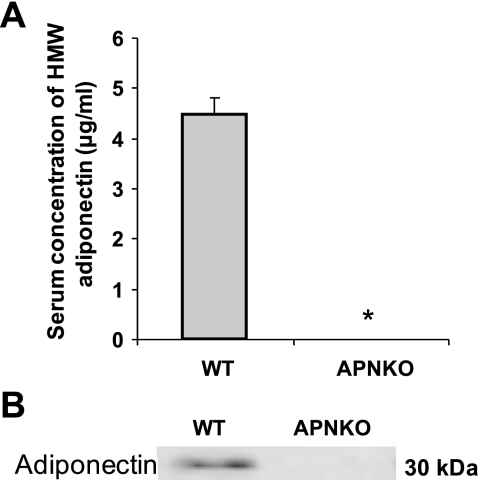

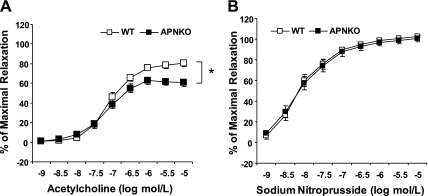

Basic characteristics including body mass, glucose, HOMR-IR, and insulin levels were comparable between WT and APNKO mice (Table 2). Next, we investigated the role of APN on endothelial function in the aorta. We confirmed the lack of serum APN and the protein expression in the aorta in APNKO mice (Fig. 7, A and B). In aortae isolated from male APNKO mice, ACh-induced vasodilation was blunted compared with age-matched WT littermates (Fig. 8A). However, SNP-induced vasodilation was identical between WT and APNKO (Fig. 8B).

Table 2.

Basic characteristics of wild-type and adiponectin knockout mice

| Wild-type | Adiponectin Knockout | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 7 | 11 |

| Body mass, g | 29.41 ± 0.41 | 31.70 ± 0.65 |

| Nonfasting | ||

| Glucose, mg/dL | 227.43 ± 15.95 | 224.00 ± 5.91 |

| HOMA-IR | 9.24 ± 1.05 | 15.17 ± 2.21 |

| Insulin, ng/ml | 0.58 ± 0.07 | 0.98 ± 0.16 |

| Fasting | ||

| n | 6 | 6 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 114 ± 0.14 | 115.17 ± 0.16 |

| HOMA-IR | 1.17 ± 0.61 | 1.20 ± 0.39 |

| Insulin, ng/ml | 0.14 ± 0.07 | 0.16 ± 0.05 |

Values are means ± SE.

Fig. 7.

Protein expressions of adiponectin in wild-type (WT) and adiponectin knockout (APNKO) mice. Protein expression of adiponectin in serum (A) and aorta (B) in WT and APNKO mice is shown. APNKO mice did not express any adiponectin compared with WT mice (n = 8–14). HMW, high molecular weight. *P < 0.05 vs. WT.

Fig. 8.

A: concentration-response curve showed that endothelial-dependent vasorelaxation to ACh was significantly impaired in aortae of APNKO. B: endothelial-independent vasorelaxation to sodium nitroprusside was comparable between WT and APNKO. Each mouse aorta generated 1 to 2 rings (n = 13–26 rings/group). *P < 0.05 vs. WT.

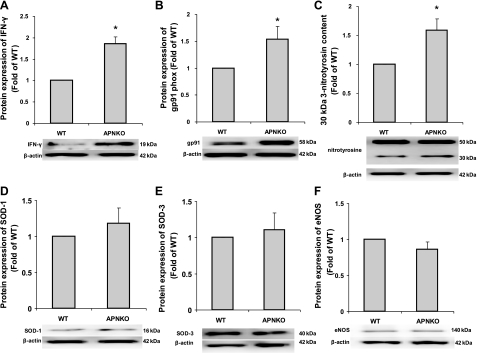

Deficiency of APN increased protein expression of proinflammatory cytokine and oxidative stress but not SOD-1 and -3.

Protein expression of INF-γ, a proinflammatory cytokine, in the APNKO aortae was significantly elevated compared with WT mice (Fig. 9A). In addition, protein expression of both gp91phox and 30 kDa nitrotyrosine was greater in APNKO mice compared with WT (Fig. 9, B and C). However, 50 kDa nitrotyrosine, SOD-1, -3, and eNOS protein expressions were comparable between WT and APNKO mice (Fig. 9, C–F).

Fig. 9.

Protein expressions of INF-γ, gp91phox, 3-nitrotyrosine, SOD-1, -3, and eNOS. INF-γ (A; proinflammatory cytokine), gp91phox [B; a NAD(P)H oxidase subunit], and 30 kDa nitrotyrosine (C; oxidative stress marker) was increased in APNKO aorta compared with WT. However, 50 kDa protein expression of nitrotyrosine was comparable between WT and APNKO. D-F: antioxidants, SOD-1, -3, and eNOS protein expressions were identical between WT and APNKO (n = 3–8). *P < 0.05 vs. WT.

DISCUSSION

The endothelium plays a key role in regulating vascular homeostasis and exerts vasoprotective effects such as vasodilation, suppression of smooth muscle cell growth, and inhibition of inflammatory responses (11, 41). A major vasodilator substance released by the endothelium is NO (9, 11, 12). Reduced NO bioavailability by both decreased production and inactivation of NO is associated with the initiation, progression, and complications of atherosclerosis (9). Because endothelial dysfunction is considered to be an early stage of atherosclerosis, understanding the mechanisms involved is a major goal for devising therapeutic treatments for atherosclerosis (11). Previous studies showed inconsistent effects of exercise on eNOS expression in the vasculature. For example, several groups reported that both low and moderate exercise increased eNOS protein expression, whereas others indicated that exercise did not change the expression of eNOS in the vasculature (12, 32, 37, 55). In addition, Bitar et al. (5) showed that diabetes increased eNOS protein, whereas our previous study showed that diabetes status was not associated with a change in eNOS protein expression within the aorta (54). These discrepancies may be derived from differences in types and intensity of exercise, age, and disease status of the animals.

Our major findings are 1) ET regimen rescues aortic dysfunction in T2D; 2) ET results in increased antioxidant, SOD-1, and APN in db/db mice; 3) ET may attenuate inflammation and macrovascular oxidative stress by inhibiting gp91phox-dependent NAD(P)H oxidase activation via an APN-dependent manner; and 4) APN plays a role in preventing endothelial dysfunction in T2D.

Role of ET in endothelial function independent of the changes in body weight, hyperglycemia, and insulin sensitivity.

Numerous studies recommend that increased physical activity is beneficial to prevent and/or ameliorate T2D and CVD by improving hyperglycemia, body weight, and insulin sensitivity (6, 51). Although these three factors are important considerations in abating diabetes-induced vascular dysfunction, beneficial effects of ET also can occur independently from these factors (17, 32, 54). In our study, 10 wk of moderate ET did not decrease body weight of db/db mice because this animal model is a knockout of the leptin receptor, which maintains an obese state by increased food intake (Table 1). Although ET partially improved hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia, it did not decrease these parameters to those found in healthy control levels (Table 1).

Antioxidant effects of ET.

Excessive oxidative stress defined as an imbalance between production and removal of superoxide facilitated by enzymatic activity is one of the major factors contributing to endothelial dysfunction in diabetes and CVD (5, 9, 54). NO is highly reactive with superoxide to form peroxynitrite, which results in decreased NO bioavailability. There are multiple cellular sources of superoxide such as NAD(P)H oxidase, xanthine oxidase, the mitochondrial respiratory chain, arachidonic acid metabolism, and uncoupled eNOS when substrate or cofactors are not available (5, 7). Prior work showed activation of the vascular isoform of NAD(P)H oxidase contributes to superoxide formation in diabetes (13, 38, 54). Additionally, inhibition of ROS generation both by genetic deficiency and by pharmacological blockage of gp91phox decreased production of superoxide in diabetes (13, 38, 54). We showed that gp91phox protein expression in db/db is increased, suggesting that upregulation of gp91phox is associated with apocynin-inhibitable NAD(P)H oxidase-derived superoxide production (54). In our study, ET decreased protein expression of gp91phox in db/db, suggesting that downregulation of gp91phox by ET, which contributes to a reduction in NAD(P)H derived-superoxide production and consequently improvement of endothelial function in db/db (Fig. 6B). Apart from superoxide production, oxidative stress also can be regulated by antioxidant enzymes. SODs are enzymes that scavenge superoxide to form hydrogen peroxide and play a role in preserving NO bioavailability in the vasculature (32, 47). In our study, db/db mice showed decreased endothelial function compared with Con, but TEMPOL incubation partially restored endothelial function in db/db, suggesting an increase of antioxidant enzymes may contribute to restoring endothelial function (Fig. 3). Indeed, ET upregulates SOD-1 protein expression in both Con and db/db. But SOD-2 protein expression was minimal in the aorta (data not shown). Therefore, we suggest the effect of ET in T2D is by decreasing production of superoxide and increasing antioxidant activity.

Anti-inflammatory effects of ET.

Recent studies showed that inflammation plays a key role in coronary artery disease and other manifestations of atherosclerosis (19, 20). Atherosclerosis is an inflammatory disease in which immune mechanisms interact with metabolic risk factors such as hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and elevated blood pressure to initiate, propagate, and activate lesions in the arterial tree (19, 39). The atherosclerotic process is initiated with accumulation of cholesterol-containing low density lipoproteins in the intima (19, 20). When the endothelium is activated, leukocyte adhesion molecules and chemokines promote recruitment of monocytes and T cells (19, 20). T cells in lesions recognize local antigens and mount T helper-1 responses with secretion of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF, IFN-γ) that contribute to local inflammation (19, 20). Of these cytokines, IFN-γ improves the efficiency of antigen presentation and increases synthesis of the TNF and IL-1 (19, 44). Furthermore, IFN-γ promotes macrophage and endothelial activation with production of adhesion molecules, cytokines, chemokines, oxygen-derived free radicals, proteases, and coagulation factors (19, 20). Indeed, apolipoprotein E-knockout mice lacking INF-γ are inhibited in the development of atherosclerosis, suggesting that IFN-γ contributes to development of atherosclerosis (18). In our study, aorta protein expression of INF-γ is increased in db/db mice compared with control mice. Exercise decreased IFN-γ in the aorta, suggesting that ET inhibits endothelial dysfunction, in part, by ameliorating the inflammation process (Fig. 6A).

Role of APN in endothelial dysfunction.

Adiponectin is a 30 kDa protein exclusively secreted by adipose tissue and plays a protective role against the development of diabetes and atherosclerosis (14, 23, 26, 30, 48, 53). Plasma levels of APN are markedly reduced in diabetic patients as well as rodent models of diabetes (21, 25, 40, 45). In addition, numerous epidemiological studies showed that reduced APN levels correlate with CVD (16, 56). Several clinical observations also demonstrated reduced APN is associated with impaired endothelial-dependent vasodilation (34, 43, 46).

Aging is one of the major risk factors for the development of CVD (49). Adiponectin levels increase with age; however, patients who have diabetes or obesity show lower plasma APN (1, 24, 31). Several studies indicate there may be a survival advantage conferred by the beneficial cardiometabolic protective effects of APN (2, 4). Atzmon et al. (2) showed that genotypic characteristics of longevity linked to higher circulating APN have been found to be more common in centenarians than in control group. More studies are required to address mechanisms underlying APN and aging process.

In our study, serum and aorta protein expression of APN were significantly decreased in db/db mice, but following 10 wk of exercise improved APN contents in serum and in the aortae of these mice (Fig. 4).

Because our diabetic mice showed decreased both serum and aorta protein expression of APN and ET conferred restoration of the levels, we hypothesized that APN may play an important role in remediating endothelial dysfunction in diabetes. Using APNKO mice, we demonstrated that endothelial-dependent vasodilation was significantly reduced in isolated aortae from APNKO mice compared with WT mice, suggesting reduced APN levels in diabetes may be a main factor contributing to endothelial dysfunction (Fig. 8). Immunoblots were used to investigate mechanisms of APN-dependent anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. Our preliminary results have demonstrated that protein expressions of antioxidants, SOD-1, -3, and eNOS were normal in APN-deficient mice (Fig. 9, D–F), suggesting that endothelial dysfunction in APNKO mice is independent of these factors. We showed that increased IFN-γ, gp91phox, and nitrotyrosine (marker for peroxynitrite) occur in APNKO mice, suggesting that APN may inhibit oxidative processes that lead to inflammation and CVD (Fig. 9).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the major finding of this study is that exercise training: 1) improved ACh-induced dilation in diabetes-related endothelial dysfunction of aorta; 2) both serum content and aorta protein expression of APN were increased in training in diabetic mice; 3) SOD-1 protein expression was increased by ET in diabetic mice, whereas aorta expression of eNOS was not changed by ET. Interestingly, increased APN by ET may inhibit inflammation by reducing IFN-γ and oxidative stress in diabetes. In addition, ET ameliorated endothelial dysfunction by increasing anti-oxidant enzyme, SOD-1 via an APN-independent mechanism. Our ET results for diabetic mice show improved endothelial function, suggesting that exercise intervention promotes NO bioavailability and suppresses oxidative/nitrative stress to reduce diabetes-induced endothelial dysfunction. We suggest exercise has a role as effective intervention in restoring endothelial function to diabetics via both APN-dependent and independent pathways.

GRANTS

This study was supported by grants from Pfizer Atorvastatin Research Award (2004-37), American Heart Association SDG (110350047A), and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants (RO1-HL077566 and RO1-HL085119; all grants C. Zhang).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1. Adamczak M, Rzepka E, Chudek J, Wiecek A. Ageing and plasma adiponectin concentration in apparently healthy males and females. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 62: 114–118, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Atzmon G, Pollin TI, Crandall J, Tanner K, Schechter CB, Scherer PE, Rincon M, Siegel G, Katz M, Lipton RB, Shuldiner AR, Barzilai N. Adiponectin levels and genotype: a potential regulator of life span in humans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 63: 447–453, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bhagat K, Vallance P. Inflammatory cytokines impair endothelium-dependent dilatation in human veins in vivo. Circulation 96: 3042–3047, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bik W, Baranowska-Bik A, Wolinska-Witort E, Martynska L, Chmielowska M, Szybinska A, Broczek K, Baranowska B. The relationship between adiponectin levels and metabolic status in centenarian, early elderly, young and obese women. Neuro Endocrinol Lett 27: 493–500, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bitar MS, Wahid S, Mustafa S, Al-Saleh E, Dhaunsi GS, Al-Mulla F. Nitric oxide dynamics and endothelial dysfunction in type II model of genetic diabetes. Eur J Pharmacol 511: 53–64, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boule NG, Haddad E, Kenny GP, Wells GA, Sigal RJ. Effects of exercise on glycemic control and body mass in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. JAMA 286: 1218–1227, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brownlee M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature 414: 813–820, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cao Y, Tao L, Yuan Y, Jiao X, Lau WB, Wang Y, Christopher T, Lopez B, Chan L, Goldstein B, Ma XL. Endothelial dysfunction in adiponectin deficiency and its mechanisms involved. J Mol Cell Cardiol 46: 413–419, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen X, Zhang H, McAfee S, Zhang C. The reciprocal relationship between adiponectin and LOX-1 in the regulation of endothelial dysfunction in ApoE knockout mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 299: H605–H612, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clapp BR, Hingorani AD, Kharbanda RK, Mohamed-Ali V, Stephens JW, Vallance P, MacAllister RJ. Inflammation-induced endothelial dysfunction involves reduced nitric oxide bioavailability and increased oxidant stress. Cardiovasc Res 64: 172–178, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Davignon J, Ganz P. Role of endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerosis. Circulation 109: III27–III32, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Durrant JR, Seals DR, Connell ML, Russell MJ, Lawson BR, Folian BJ, Donato AJ, Lesniewski LA. Voluntary wheel running restores endothelial function in conduit arteries of old mice: direct evidence for reduced oxidative stress, increased superoxide dismutase activity and down-regulation of NADPH oxidase. J Physiol 587: 3271–3285, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ebrahimian TG, Heymes C, You D, Blanc-Brude O, Mees B, Waeckel L, Duriez M, Vilar J, Brandes RP, Levy BI, Shah AM, Silvestre JS. NADPH oxidase-derived overproduction of reactive oxygen species impairs postischemic neovascularization in mice with type 1 diabetes. Am J Pathol 169: 719–728, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fernandez-Real JM, Castro A, Vazquez G, Casamitjana R, Lopez-Bermejo A, Penarroja G, Ricart W. Adiponectin is associated with vascular function independent of insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Care 27: 739–745, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gao X, Belmadani S, Picchi A, Xu X, Potter BJ, Tewari-Singh N, Capobianco S, Chilian WM, Zhang C. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces endothelial dysfunction in Lepr(db) mice. Circulation 115: 245–254, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goldstein BJ, Scalia R. Adipokines and vascular disease in diabetes. Curr Diab Rep 7: 25–33, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gregg EW, Gerzoff RB, Thompson TJ, Williamson DF. Trying to lose weight, losing weight, and 9-year mortality in overweight US adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care 27: 657–662, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gupta S, Pablo AM, Jiang X, Wang N, Tall AR, Schindler C. IFN-gamma potentiates atherosclerosis in ApoE knock-out mice. J Clin Invest 99: 2752–2761, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 352: 1685–1695, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hansson GK, Robertson AK, Soderberg-Naucler C. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Annu Rev Pathol 1: 297–329, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hotta K, Funahashi T, Arita Y, Takahashi M, Matsuda M, Okamoto Y, Iwahashi H, Kuriyama H, Ouchi N, Maeda K, Nishida M, Kihara S, Sakai N, Nakajima T, Hasegawa K, Muraguchi M, Ohmoto Y, Nakamura T, Yamashita S, Hanafusa T, Matsuzawa Y. Plasma concentrations of a novel, adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in type 2 diabetic patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 20: 1595–1599, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Johnstone MT, Creager SJ, Scales KM, Cusco JA, Lee BK, Creager MA. Impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Circulation 88: 2510–2516, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T. Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors. Endocr Rev 26: 439–451, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kizer JR, Arnold AM, Strotmeyer ES, Ives DG, Cushman M, Ding J, Kritchevsky SB, Chaves PH, Hirsch CH, Newman AB. Change in circulating adiponectin in advanced old age: determinants and impact on physical function and mortality. The Cardiovascular Health Study All Stars Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 65: 1208–1214, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Koenig W, Khuseyinova N, Baumert J, Meisinger C, Lowel H. Serum concentrations of adiponectin and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus and coronary heart disease in apparently healthy middle-aged men: results from the 18-year follow-up of a large cohort from southern Germany. J Am Coll Cardiol 48: 1369–1377, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kubota N, Terauchi Y, Yamauchi T, Kubota T, Moroi M, Matsui J, Eto K, Yamashita T, Kamon J, Satoh H, Yano W, Froguel P, Nagai R, Kimura S, Kadowaki T, Noda T. Disruption of adiponectin causes insulin resistance and neointimal formation. J Biol Chem 277: 25863–25866, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lerman I, Harrison BC, Freeman K, Hewett TE, Allen DL, Robbins J, Leinwand LA. Genetic variability in forced and voluntary endurance exercise performance in seven inbred mouse strains. J Appl Physiol 92: 2245–2255, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Maeda N, Shimomura I, Kishida K, Nishizawa H, Matsuda M, Nagaretani H, Furuyama N, Kondo H, Takahashi M, Arita Y, Komuro R, Ouchi N, Kihara S, Tochino Y, Okutomi K, Horie M, Takeda S, Aoyama T, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y. Diet-induced insulin resistance in mice lacking adiponectin/ACRP30. Nat Med 8: 731–737, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Massett MP, Berk BC. Strain-dependent differences in responses to exercise training in inbred and hybrid mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288: R1006–R1013, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Matsuda M, Shimomura I, Sata M, Arita Y, Nishida M, Maeda N, Kumada M, Okamoto Y, Nagaretani H, Nishizawa H, Kishida K, Komuro R, Ouchi N, Kihara S, Nagai R, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y. Role of adiponectin in preventing vascular stenosis. The missing link of adipo-vascular axis. J Biol Chem 277: 37487–37491, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mitterberger MC, Mattesich M, Klaver E, Lechner S, Engelhardt T, Larcher L, Pierer G, Piza-Katzer H, Zwerschke W. Adipokine profile and insulin sensitivity in formerly obese women subjected to bariatric surgery or diet-induced long-term caloric restriction. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 65: 915–923, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moien-Afshari F, Ghosh S, Elmi S, Rahman MM, Sallam N, Khazaei M, Kieffer TJ, Brownsey RW, Laher I. Exercise restores endothelial function independently of weight loss or hyperglycaemic status in db/db mice. Diabetologia 51: 1327–1337, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ohkawa F, Ikeda U, Kanbe T, Kawasaki K, Shimada K. Effects of inflammatory cytokines on vascular tone. Cardiovasc Res 30: 711–715, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ouchi N, Ohishi M, Kihara S, Funahashi T, Nakamura T, Nagaretani H, Kumada M, Ohashi K, Okamoto Y, Nishizawa H, Kishida K, Maeda N, Nagasawa A, Kobayashi H, Hiraoka H, Komai N, Kaibe M, Rakugi H, Ogihara T, Matsuzawa Y. Association of hypoadiponectinemia with impaired vasoreactivity. Hypertension 42: 231–234, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Park Y, Capobianco S, Gao X, Falck JR, Dellsperger KC, Zhang C. Role of EDHF in type 2 diabetes-induced endothelial dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H1982–H1988, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Park Y, Wu J, Zhang H, Wang Y, Zhang C. Vascular dysfunction in Type 2 diabetes: emerging targets for therapy. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 7: 209–213, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pellegrin M, Miguet-Alfonsi C, Bouzourene K, Aubert JF, Deckert V, Berthelot A, Mazzolai L, Laurant P. Long-term exercise stabilizes atherosclerotic plaque in ApoE knockout mice. Med Sci Sports Exerc 41: 2128–2135, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Picchi A, Gao X, Belmadani S, Potter BJ, Focardi M, Chilian WM, Zhang C. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces endothelial dysfunction in the prediabetic metabolic syndrome. Circ Res 99: 69–77, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pickup JC. Inflammation and activated innate immunity in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 27: 813–823, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sandu O, Song K, Cai W, Zheng F, Uribarri J, Vlassara H. Insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes in high-fat-fed mice are linked to high glycotoxin intake. Diabetes 54: 2314–2319, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schalkwijk CG, Stehouwer CD. Vascular complications in diabetes mellitus: the role of endothelial dysfunction. Clin Sci (Lond) 109: 143–159, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schmidt AM, Crandall J, Hori O, Cao R, Lakatta E. Elevated plasma levels of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) in diabetic patients with microalbuminuria: a marker of vascular dysfunction and progressive vascular disease. Br J Haematol 92: 747–750, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shimabukuro M, Higa N, Asahi T, Oshiro Y, Takasu N, Tagawa T, Ueda S, Shimomura I, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y. Hypoadiponectinemia is closely linked to endothelial dysfunction in man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88: 3236–3240, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Szabo SJ, Sullivan BM, Peng SL, Glimcher LH. Molecular mechanisms regulating Th1 immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol 21: 713–758, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Takagi T, Matsuda M, Abe M, Kobayashi H, Fukuhara A, Komuro R, Kihara S, Caslake MJ, McMahon A, Shepherd J, Funahashi T, Shimomura I. Effect of pravastatin on the development of diabetes and adiponectin production. Atherosclerosis 196: 114–121, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tan KC, Xu A, Chow WS, Lam MC, Ai VH, Tam SC, Lam KS. Hypoadiponectinemia is associated with impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89: 765–769, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Trott DW, Gunduz F, Laughlin MH, Woodman CR. Exercise training reverses age-related decrements in endothelium-dependent dilation in skeletal muscle feed arteries. J Appl Physiol 106: 1925–1934, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tsubakio-Yamamoto K, Matsuura F, Koseki M, Oku H, Sandoval JC, Inagaki M, Nakatani K, Nakaoka H, Kawase R, Yuasa-Kawase M, Masuda D, Ohama T, Maeda N, Nakagawa-Toyama Y, Ishigami M, Nishida M, Kihara S, Shimomura I, Yamashita S. Adiponectin prevents atherosclerosis by increasing cholesterol efflux from macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 375: 390–394, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ungvari Z, Kaley G, de Cabo R, Sonntag WE, Csiszar A. Mechanisms of vascular aging: new perspectives. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 65: 1028–1041, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. van den Oever IA, Raterman HG, Nurmohamed MT, Simsek S. Endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, and apoptosis in diabetes mellitus. Mediators Inflamm 2010: 792393, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wing RR, Goldstein MG, Acton KJ, Birch LL, Jakicic JM, Sallis JF, Jr, Smith-West D, Jeffery RW, Surwit RS. Behavioral science research in diabetes: lifestyle changes related to obesity, eating behavior, and physical activity. Diabetes Care 24: 117–123, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yang J, Park Y, Zhang H, Xu X, Laine GA, Dellsperger KC, Zhang C. Feed-forward signaling of TNF-α and NF-κB via IKK-β pathway contributes to insulin resistance and coronary arteriolar dysfunction in type 2 diabetic mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 296: H1850–H1858, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yokoyama H, Emoto M, Araki T, Fujiwara S, Motoyama K, Morioka T, Koyama H, Shoji T, Okuno Y, Nishizawa Y. Effect of aerobic exercise on plasma adiponectin levels and insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 27: 1756–1758, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhang H, Zhang J, Ungvari Z, Zhang C. Resveratrol improves endothelial function: role of TNFα and vascular oxidative stress. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 29: 1164–1171, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhang QJ, McMillin SL, Tanner JM, Palionyte M, Abel ED, Symons JD. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase phosphorylation in treadmill-running mice: role of vascular signalling kinases. J Physiol 587: 3911–3920, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhu W, Cheng KK, Vanhoutte PM, Lam KS, Xu A. Vascular effects of adiponectin: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic intervention. Clin Sci (Lond) 114: 361–374, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]