Abstract

Acute coronary syndromes (ACS) are common, life-threatening cardiac disorders that typically are triggered by rupture or erosion of an atherosclerotic plaque. Platelet deposition and activation of the blood coagulation cascade in response to plaque disruption lead to the formation of a platelet-fibrin thrombus, which can grow rapidly, obstruct coronary blood flow, and cause myocardial ischemia and/or infarction. Several clinical studies have examined the relationship between physical activity and ACS, and numerous preclinical and clinical studies have examined specific effects of sustained physical training and acute physical activity on atherosclerotic plaque rupture, platelet function, and formation and clearance of intravascular fibrin. This article reviews the available literature regarding the role of physical activity in determining the incidence of atherosclerotic plaque rupture and the pace and extent of thrombus formation after plaque rupture.

Keywords: exercise, blood platelets, myocardial infarction, blood coagulation, fibrinolysis

acute coronary syndromes (ACS) are a group of life-threatening cardiac diseases characterized by acute, regional reductions in coronary blood flow, myocardial ischemia, or infarction, and pain in the chest, neck, or arms. The ACS are divided into the clinical diagnoses of unstable angina pectoris, non-ST segment myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), and ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). The vast majority of ACS are triggered by disruption of an atherosclerotic plaque, which converts coronary atherosclerosis from a chronic disease to an acute medical emergency. Thrombosis plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of ACS, as disruption of an atherosclerotic plaque exposes flowing blood to subendothelial collagen, tissue factor, and other procoagulant molecules that trigger activation of platelets and formation of fibrin within the vessel lumen (Fig. 1). If the thrombotic response to plaque disruption is limited, coronary blood flow is not altered significantly and the plaque disruption remains clinically silent. However, if platelets and fibrin amass in sufficient quantity to obstruct coronary blood flow, clinical presentation ensues. Physical activity has been linked to vascular changes that affect the propensity of atherosclerotic plaques to rupture. Physical activity also has been shown to regulate platelet function and the cellular and molecular pathways that govern fibrin formation and clearance. Hence, physical activity appears to be an important determinant of the incidence and outcomes of ACS. This article will review currently available studies regarding the relationship between physical activity and ACS. Emphasis will be placed on the mechanisms by which physical activity regulates atherosclerotic plaque rupture and the function of blood platelets, the blood coagulation cascade, and the fibrinolytic system.

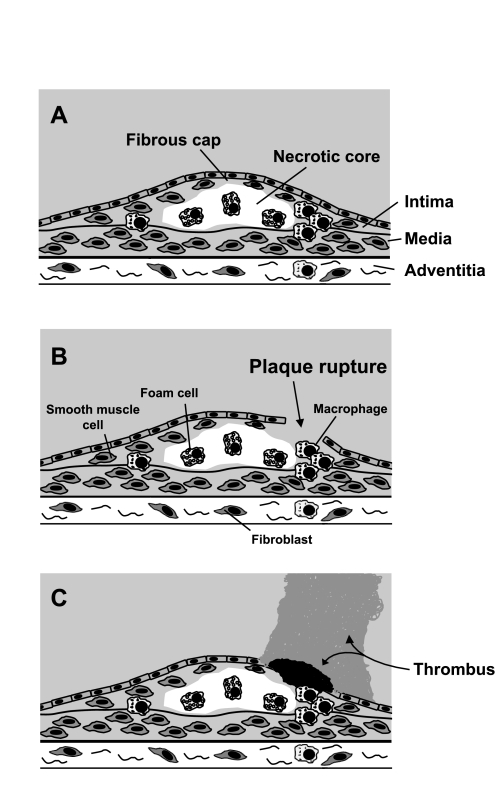

Fig. 1.

Atherosclerotic plaque rupture and thrombosis. A: coronary atherosclerotic plaque with thin-walled fibrous cap and thrombogenic necrotic core. B: plaque rupture. C: thrombotic response. If thrombus formation is not extensive (black thrombus), there is no obstruction to blood flow and event does not cause clinical symptoms. If thrombus formation is extensive (gray thrombus), blood flow is obstructed and acute coronary syndrome develops.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF CORONARY PLAQUE RUPTURE

Atherosclerosis is a chronic vascular disease that is characterized by endothelial dysfunction, intimal hyperplasia, inflammation, smooth muscle proliferation, and deposition of lipids and formation of microvessels within the vascular wall. The focal nature of atherosclerosis results in formation of discrete plaques. Key components of the plaque include a fibrous cap, composed of smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts, an overlying layer of endothelial cells, and an internal core that contains cholesterol and other lipids, macrophages, foam cells (which are derived from macrophages), other inflammatory cells, and extracellular matrix. Some plaques are more vulnerable to rupture than others. Important characteristics of the vulnerable plaque include a thin fibrous cap, a large, lipid-rich, hypocellular core, and the presence of leukocytes, which produce metalloproteinases (MMPs) and other factors that trigger extracellular matrix degradation and apoptosis, within the fibrous cap (Fig. 1). Rupture of the fibrous cap is not the only mechanism by which thrombosis overlying an atherosclerotic plaque can be triggered, e.g., plaque erosion (without fibrous cap rupture) can initiate thrombosis (14). However, fibrous cap rupture is the only from of plaque disruption that has been linked mechanistically to physical exercise (4).

BRIEF SUMMARY OF PLATELET AGGREGATION, BLOOD COAGULATION, AND FIBRINOLYSIS

Atherosclerotic plaque disruption triggers platelet activation by multiple pathways. Endothelial disruption exposes subendothelial collagen, which activates platelets by binding glycoprotein VI (GPVI) and integrin α2β1 on the platelet surface (46). After plaque rupture plasma von Willebrand factor (vWF) binds to collagen, and platelets adhere to immobilized vWF via GPIb-GPV-GPIX and integrin αIIbβ3 (GPIIb/IIIa) (20). GPIIb/IIIa also binds fibrinogen, which drives platelet aggregation and thrombus growth. Adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and thromboxane A2 bind to specific receptors on platelets to amplify their aggregation after plaque rupture (38). Platelets express alpha-2 adrenergic receptors, which likely play an important role in mediating effects of physical exercise on platelet function (13, 55).

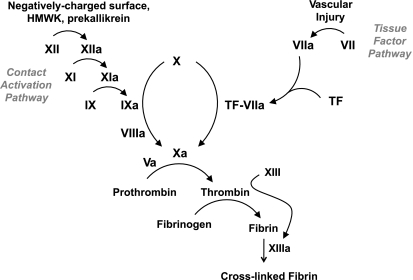

The primary activator of the blood coagulation system is tissue factor (TF), a cell-membrane-anchored protein that is abundant in the adventitia of normal blood vessels and the intima and media of atherosclerotic arteries. In response plaque disruption, plasma factor VIIa (“a” denotes the activated form of the blood coagulation proteins) binds TF to produce a complex that converts factor X to factor Xa (Fig. 2). Factor Xa, in complex with factor Va, calcium, and phospholipid, converts prothrombin to thrombin. In addition to activating platelets and clotting fibrinogen, thrombin activates factor XIII, which cross-links fibrin monomers. The contact activation pathway, consisting of prekallikrein, high-molecular-weight kininogen, factor XI, and factor XII, produces factor IXa, which, in complex with factor VIIIa, activates factor X, i.e., factor X can be activated by both the TF and contact activation pathways. While the TF pathway is the dominant initiator of hemostasis and thrombosis, the contact activation pathway plays an important amplification role (2).

Fig. 2.

Blood coagulation cascade. The tissue factor and contact activation pathways converge at factor X, whose activation initiates the common pathway. HMWK, high-molecular-weight kininogen.

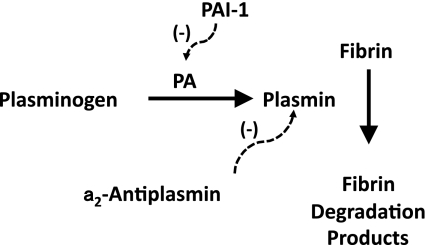

Accretion of fibrin within the vasculature depends not only on the activity of the coagulation cascade, but also the fibrinolytic pathway (Fig. 3), which degrades fibrin. The central protein of the fibrinolytic system is plasminogen, which circulates in plasma and is activated by plasminogen activators (PAs). Urokinase (u-PA) and tissue-type PA (t-PA) are the two main endogenous PAs. t-PA, which is released by vascular endothelial cells, is the main PA in plasma. Activated plasminogen (i.e., plasmin) cleaves fibrin into soluble degradation products, thereby dissolving the fibrin clot. Antiplasmin, which inhibits plasmin, and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), which inhibits t-PA and u-PA, are the main endogenous inhibitors of the fibrinolytic system.

Fig. 3.

Fibrinolytic system. Actions of fibrinolysis inhibitors are indicated by dashed lines. PA, plasminogen activator; PAI-1, PA inhibitor-1.

EPIDEMIOLOGICAL DATA LINKING PHYSICAL ACTIVITY TO ACS

Several studies have examined the relationships between physical activity, performed repetitively over prolonged periods of time, on the incidences of total and cardiac mortality and nonfatal ACS. The most comprehensive data arise from meta-analyses of predominantly male patients with established coronary artery disease (CAD) who received 2–6 mo of supervised exercise training within a cardiac rehabilitation program, after which patients exercised regularly in an unsupervised fashion (36, 37). Analysis of 8,440 patients with established CAD participating in 51 randomized, controlled trials revealed chronic physical exercise, assessed over a mean of 2.4 years, was associated with a 27% reduction in total mortality (P < 0.05) and a 31% reduction in cardiac mortality (P < 0.05) (21). However, this study did not find that regular physical activity significantly reduced the rate of nonfatal myocardial infarction or sudden cardiac death, events mechanistically linked to atherosclerotic plaque rupture and thrombosis. Reduction in death without a reduction in nonfatal myocardial infarction or sudden cardiac death raises the possibility that exercise training reduces the risk of fatal ventricular arrhythmias and/or the extent of myocyte necrosis associated with myocardial infarction, without actually reducing the incidence of coronary plaque rupture or the intensity of ensuing thrombosis.

Despite the recognized benefits of chronic physical exercise on cardiovascular health (16, 44), acute vigorous physical exercise can trigger coronary thrombosis and ACS, particularly in individuals who follow a sedentary lifestyle (9, 30, 45, 51, 52). The relative risk of sustaining an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) during physical exercise has been estimated to be 20- to 30-fold greater than the risk of developing an AMI while at rest (17). However, the actual incidence of exercise-induced AMI is low—estimated to be only one annual event per 593–3,852 apparently healthy middle-aged men (50). In addition, habitual vigorous exercise has been shown to diminish the risk of sudden death during vigorous exertion (1, 9).

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY CAN TRIGGER ATHEROSCLEROTIC PLAQUE RUPTURE

Burke et al. (4) performed histological studies of 141 men with severe coronary artery disease who died suddenly, including 116 individuals who died while at rest and 25 who died during strenuous activity or emotional stress. Of note, 21/25 of the individuals who died during physical or emotional stress were considered to be physically deconditioned. The incidence of plaque rupture was 68% in men dying during exertion or emotional stress vs. 23% in men dying while at rest (P < 0.001). Hemorrhage into the plaque was significantly more frequent in the exertional-death group than in the rest-death group. Men dying during exertion/emotional stress had a significantly higher mean ratio of total cholesterol to high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol than those dying at rest. In multivariate analysis, both exertion and the ratio of total cholesterol to high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol were independently associated with acute plaque rupture. The authors concluded that in physically inactive men with severe CAD, acute physical exertion and/or emotional stress are independent risk factors for fatal atherosclerotic plaque rupture. The authors also observed that plaques that ruptured during exercise/emotional stress were characterized by a thin fibrous cap, extensive vasa vasorum, and rupture in the midportion of the cap. In contrast, the site of plaque rupture in patients who died suddenly while at rest was most often in the shoulder region (i.e., junction of the cap with the normal wall). The authors postulated that changes in vasomotor tone during physical exercise triggers plaque rupture, and that the thinness of the fibrous cap is a key determinant of exercise-induced plaque rupture.

Tanaka et al. (49) assessed morphology of plaque rupture in ACS patients using optical coherence tomography (OCT), a catheter-based imaging technique that allows characterization of plaque composition in living patients. This study assessed 43 consecutive men with ACS who were found to have plaque rupture after undergoing cardiac catheterization with OCT analysis. Patients were divided into those that were resting at the onset of ACS (n = 28) and those whose ACS symptoms began during physical activity (n = 15). Physical activity was defined as exertion requiring expenditure of ≥4 metabolic equivalent of task (MET) units, i.e., an activity level similar to that of walking 4 miles/h on the level. In contrast to the study by Burke et al. (4), the study by Tanaka et al. (49) found that 1) the culprit plaque ruptured at the shoulder more frequently in the exertion group (93% of patients) than in the rest group (57% of patients; P = 0.014), and 2) the broken fibrous cap was significantly thicker in the exertion group than in the rest-onset group (P < 0.001). These data suggested that plaques with thin fibrous caps can rupture during rest or usual day-to-day activities, while rupture of plaques with thick (i.e., 70–140 μm) fibrous caps may depend on mechanical factors generated during strenuous physical activity. In fact, the authors estimated that ∼30% of all plaque ruptures occur in thick-capped atheroma.

MECHANISMS LINKING PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND PLAQUE RUPTURE

Preclinical studies have examined the mechanisms that underlie the relationships between physical activity and plaque rupture. In hyperlipidemic mice, chronic physical exercise, in conjunction with metabolic treatment (antioxidants and l-arginine), reduced spontaneous atherosclerotic plaque rupture (35). In this study, moderate physical exercise (swimming) increased plasma levels of nitric oxide, suggesting increased nitric oxide expression as a mechanism underlying the beneficial effect of chronic physical exercise on plaque rupture. Consistent with these data, McAllister et al. (29a) showed that chronic treadmill exercise increased endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression in rats, and Lu et al. (28) demonstrated that long-term exercise increases nitric oxide production by murine macrophages.

Kadoglou et al. (22) examined the effects of exercise on atherosclerotic plaque composition in mice. Apolipoprotein E-deficient mice (n = 90; males 50%) were fed high-fat chow for 16 wk, at which point 30 mice were euthanized and served as a control group. Remaining mice were changed to normal chow, which they received for 6 wk, during which 30 mice performed daily treadmill exercise (up to 60 min daily at 15 m/min and 5% grade), and 30 mice remaining in their cages without access to exercise equipment. Atherosclerotic plaque burden, assessed within the aortic root, was 30% lower in the exercise group than in the control and sedentary groups. Collagen and elastin content of atherosclerotic plaques were significantly higher in the exercise group than in the sedentary and control groups, changes that would be anticipated to reduce the incidence of plaque rupture. Compared with the control and sedentary groups, concentrations of matrix MMP-9 (MMP-9) and macrophages within atherosclerotic plaques were significantly lower in the exercise group, while the concentration of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) was significantly higher in plaques of exercised mice. The changes in plaque MMP-9 expression and macrophage content induced by exercise would be expected to reduce plaque rupture, as expression of active MMP-9 by macrophages significantly increases atherosclerotic plaque rupture in a murine model (15).

EFFECTS OF PHYSICAL EXERCISE ON PLATELET FUNCTION

The extent of the thrombotic response to atherosclerotic plaque rupture or erosion is a critical determinant of whether vascular occlusion occurs or not. Hence, physical activity could regulate the development of ACS via effects on platelet function. Several studies have shown that acute physical exercise increases platelet reactivity, typically assessed by in vitro aggregation assays, in both healthy individuals and in patients with cardiovascular disease (8, 17, 25, 26, 40, 43). The effects of chronic exercise training and physical deconditioning on platelet function also have been studied. Wang et al. (56, 57) demonstrated that sustained periods of exercise training suppress platelet adhesion and aggregation in healthy sedentary men and women. In these studies healthy though sedentary men and women were randomly divided into training and control groups. The trained subjects exercised on a bicycle ergometer at 60% of maximal oxygen consumption for 30 min/day, 5 days/wk for 8 wk. Thereafter, subjects underwent a 12-wk period of physical deconditioning. A progressive exercise test was performed on trained subjects at baseline and every 4 wk, and blood samples were drawn before and after this exercise test. The same progressive exercise test, with blood drawn before and after exercise, was performed on control subjects at baseline and 8 wk later. Platelet adhesion was measured using a tapered parallel-plate chamber. Platelet aggregation was induced by ADP and evaluated by the %reduction in single platelet count. The studies showed that platelet adhesion and aggregation were enhanced by acute strenuous exercise, but that the enhancement of platelet reactivity by acute exercise was significantly blunted in physically trained subjects compared with control, nonexercised subjects. Furthermore, the effects of exercise training on platelet function were lost after 12 wk of physical deconditioning. Another study showed that acute, strenuous treadmill exercise upregulated platelet reactivity in healthy, sedentary individuals, but not in healthy individuals who were habitually physically active (24). The beneficial effects of chronic physical exercise on platelet activation in hypertensive patients without known atherosclerosis was studied by de Meirelles et al. (10). In this study, 13 sedentary hypertensive patients underwent 60 min of aerobic exercise three times a week, while 6 sedentary hypertensive patients served as the control group. After 12 wk, platelet reactivity, assessed at rest by in vitro aggregometry, was significantly lower in the exercise group than in the sedentary group, while platelet NO synthase activity and cGMP levels were significantly higher in the exercise group. This beneficial effect of reduced basal platelet aggregability with chronic physical exercise has also been demonstrated in normotensive, healthy subjects (56, 57). Some studies have assessed the impact of different levels of physical activity on platelet reactivity. In healthy individuals, acute, moderate-intensity physical activity was found to exert less of a stimulatory effect or no significant effect on platelet function, compared with strenuous physical activity (5, 18, 58, 59).

Overall, the effects of acute exercise and sustained physical training on platelet reactivity are consistent with the epidemiological studies, cited above, that examined the risk of developing AMI during exercise, and the modulation of this risk by prolonged physical training; i.e., acute physical activity increases platelet reactivity, while sustained physical training blunts this effect. However, the molecular pathways by which physical activity regulates platelet function remain poorly defined. Increased plasma catecholamine levels during exercise appear to play an important role in mediating the effects on platelet reactivity. Epinephrine activates platelets, though one study suggested that norepinephrine, rather than epinephrine, is the main determinant of exercise-induced upregulation of platelet reactivity (19). Consistent with the role of catecholamines in platelet activation during exercise, aspirin therapy, which inhibits thromboxane-induced platelet activation, does not inhibit the effect of acute exercise on platelet reactivity in patients with CAD (7, 39). However, one study found no linear correlation between plasma catecholamine concentrations and in vivo platelet activation in high-endurance athletes during acute exercise (31), suggesting that factors other than catecholamines mediate the enhanced platelet reactivity observed during and immediately following physical exercise. Acute physical exercise does not alter platelet intracellular free calcium concentration, a determinant of platelet reactivity (3). Protein kinase C plays a key role in regulating platelet activation. Sustained physical activity was found to inhibit the decline in platelet protein kinase C activity that occurs with aging, suggesting a potential molecular mechanism by which exercise training alters platelet reactivity (54). Platelets and other cell types can shed phospholipid membrane blebs from their surface, termed microparticles, which play important roles in hemostasis and thrombosis by supporting thrombin generation. Acute strenuous physical exercise has been shown to increase the release of procoagulant microparticles from platelets and shear-induced thrombin generation (6). While acute physical exercise increases platelet reactivity, it also is associated with activation of pathways that reduce platelet activation, perhaps as a compensatory mechanism. For example, acute vigorous exercise promotes release of nitric oxide from platelets (23). In addition, thrombin-induced expression of GPIIb/IIIa by platelets decreases in response to acute physical exercise, while the inhibitory of effect of prostacyclin on platelets is potentiated by exercise (27).

EFFECTS OF PHYSICAL ACTIVITY ON BLOOD COAGULATION AND FIBRINOLYSIS

TF present in the core of atherosclerotic plaques plays a critical role in initiating thrombosis after plaque rupture. Exercise training decreases TF content of atherosclerotic plaques in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice (41). In addition to its presence in atherosclerotic plaque, TF is expressed by circulating leukocytes, particularly monocytes, and is present in plasma microparticles. Although the vast majority of circulating TF appears to exist in an encrypted, nonfunctional form, emerging evidence suggests that circulating TF promotes thrombosis. Induction of TF activity in circulating blood cells by bacterial endotoxin is reduced in athletes compared with less active individuals, suggesting that exercise training decreases circulating TF expression (29). However, Weiss et al. (60) concluded that the TF pathway does not account for the induction of thrombin activity in blood by intense physical exercise. One study found no significant effect of exercise training on plasma factor VIII concentration (53), although another study involving patients who had sustained a myocardial infarction found that 4 wk of physical training significantly lowered plasma factor VIII activity and antigen (61). Nagy et al. (34) evaluated the association between chronic, self-reported exercise level and plasma levels of selected hemostasis factors in 292 middle-aged women who had sustained an ACS. Exercise capacity had a statistically significant, inverse relationship with plasma levels of factor VII and vWF antigens. The authors concluded that reduced levels of physical activity after ACS are associated with a prothrombotic plasma profile. In a study of 109 patients with well-controlled hypertension without a past history of thrombotic events, self-reported physical activity levels were used to compare physically active (more than 30 min/day or held manual labor jobs) with sedentary patients (33). Physically active subjects had lower levels of prothrombin fragment F1+2 (a sensitive marker of thrombin formation) compared with sedentary individuals, suggesting that chronic exercise may reduce the tendency for thrombosis. Elevated plasma fibrinogen level is associated with increased risk of ischemic cardiovascular events. Three months of aerobic exercise training was shown to significantly reduce plasma fibrinogen levels in patients with coronary artery disease (63).

Effects of acute exercise on hemostasis factors have also been reported. Two exercise sessions performed 4 h apart significantly increased inducible TF expression by blood monocytes (11). Studies examining the effects of high-intensity exercise on coagulation markers have shown transient increases in vWF, factor VIII, d-dimer (a breakdown produce of cross-linked fibrin), and antithrombin III in patients with and without established atherosclerotic disease (32, 42).

Reduced activity of the fibrinolytic system has been associated with increased risk of thrombosis. Physically trained healthy subjects exhibited significantly higher postexercise plasma t-PA activity and lower PAI-1 levels compared with untrained subjects (48). Stratton et al. (47) studied the effects of 6 mo of endurance training on t-PA and PAI-1 activity. No effects of exercise were seen in 10 younger patients. However, in the 13 older subjects statistically significant increases in plasma t-PA activity and decreases in plasma PAI-1 activity were observed in physically trained individuals. DeSouza et al. (12) found that healthy postmenopausal women who were physically active had lower plasma fibrinogen levels, t-PA antigen, PAI-1 antigen, and higher t-PA activity levels than healthy postmenopausal women who were sedentary. These finding suggest that physical training attenuates the age-associated functional decreases in the endogenous fibrinolytic system seen in sedentary women. Womack et al. (62) assessed the effects on intensity and duration of acute exercise on fibrinolysis. Fifteen healthy males performed cycle ergometer exercise at levels below and above their lactate thresholds (LT). Exercise below LT was associated with a significant increase in plasma t-PA antigen and significant decrease PAI-1 activity. However, exercise above LT elicited an even greater effect, suggesting that exercise intensity is an important determinant of the fibrinolytic response to acute physical activity.

While traditionally considerate as separate systems, the blood coagulation and fibrinolysis pathways function in an integrated fashion to regulate fibrin formation and stability. As a whole, available data suggest that sustained exercise training dampens the activity of the blood coagulation system, while acute episodes of intense physical activity can transiently upregulate circulating levels of some coagulation factors. The activity of the fibrinolytic system, assessed in terms of net t-PA activity, appears to be upregulated by both acute physical activity and sustained physical training. While the overall activities of both the blood coagulation and fibrinolysis systems appear to increase in response to acute physical exercise, the balance between the systems, which is an important determinant of fibrin stability, appears to be maintained (25).

SUMMARY AND FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

Acute physical activity increases the relative risk of ACS, although the absolute risk of ACS during or immediately after physical activity is low. Increased risk of ACS and coronary thrombosis during and immediately after physical exercise results from the enhancing effects of exercise on atherosclerotic plaque rupture, platelet reactivity, and blood coagulation. The risk of an adverse cardiovascular event during exercise is greatest in sedentary individuals with established coronary artery disease and other coronary risk factors, particularly hyperlipidemia. In contrast, sustained physical training reduces platelet reactivity and promotes changes in the blood coagulation and fibrinolytic systems that inhibit fibrin formation. However, sustained physical activity has not been established to reduce the risk of coronary plaque rupture or ACS.

While much has been learned about the effects of physical activity on ACS and coronary thrombosis, the currently available literature is predominantly observational. Furthermore, available research has focused more on the effects of exercise on surrogate markers (e.g., platelet reactivity in vitro, coagulation factor levels in plasma), than on clinically relevant endpoints, such as atherosclerotic plaque rupture, kinetics of thrombus formation, and the incidence of ACS.

Areas in need of additional research include 1) development of clinically relevant animal models of atherosclerotic plaque rupture and arterial thrombosis; 2) determination of the effects of sustained physical activity on the susceptibility of atherosclerotic plaques to rupture and the intensity of the ensuing, in situ thrombotic response; 3) elucidation of the molecular pathways by which physical training alters platelet function; 4) determination of the molecular and cellular pathways by which sustained physical activity alters the activities of the blood coagulation and fibrinolytic systems; 5) better definition of the impact of exercise type (e.g., resistance vs. aerobic), duration, and intensity of ACS and coronary thrombosis; and 6) understanding of the impact of physical exercise on the efficacies of medications used to treat or prevent ACS, such as aspirin, thienopyridines, anticoagulant and fibrinolytic agents, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors.

GRANTS

This work was supported by a research grant from the Missouri Life Sciences Research Board, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-57346 and HL-095951.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1. Albert CM, Mittleman MA, Chae CU, Lee IM, Hennekens CH, Manson JE. Triggering of sudden death from cardiac causes by vigorous exertion. N Engl J Med 343: 1355–1361, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Antoniades C, Bakogiannis C, Tousoulis D, Demosthenous M, Marinou K, Stefanadis C. Platelet activation in atherogenesis associated with low-grade inflammation. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets 9: 334–345, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barr SM, Lees KR, McBryan DD, Reid J, Farish E, Rubin PC. Exercise and platelet intracellular free calcium concentration. Clin Sci (Lond) 75: 221–224, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burke AP, Farb A, Malcom GT, Liang Y, Smialek JE, Virmani R. Plaque rupture and sudden death related to exertion in men with coronary artery disease. JAMA 281: 921–926, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cadroy Y, Pillard F, Sakariassen KS, Thalamas C, Boneu B, Riviere D. Strenuous but not moderate exercise increases the thrombotic tendency in healthy sedentary male volunteers. J Appl Physiol 93: 829–833, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen YW, Chen JK, Wang JS. Strenuous exercise promotes shear-induced thrombin generation by increasing the shedding of procoagulant microparticles from platelets. Thromb Haemost 104: 293–301, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Christiaens L, Macchi L, Herpin D, Coisne D, Duplantier C, Allal J, Mauco G, Brizard A. Resistance to aspirin in vitro at rest and during exercise in patients with angiographically proven coronary artery disease. Thromb Res 108: 115–119, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chung I, Goyal D, Macfadyen RJ, Lip GY. The effects of maximal treadmill graded exercise testing on haemorheological, haemodynamic and flow cytometry platelet markers in patients with systolic or diastolic heart failure. Eur J Clin Invest 38: 150–158, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dahabreh IJ, Paulus JK. Association of episodic physical and sexual activity with triggering of acute cardiac events: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 305: 1225–1233, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. de Meirelles LR, Mendes-Ribeiro AC, Mendes MA, da Silva MN, Ellory JC, Mann GE, Brunini TM. Chronic exercise reduces platelet activation in hypertension: upregulation of the l-arginine-nitric oxide pathway. Scand J Med Sci Sports 19: 67–74, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Degerstrom J, Osterud B. Increased inflammatory response of blood cells to repeated bout of endurance exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 38: 1297–1303, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. DeSouza CA, Jones PP, Seals DR. Physical activity status and adverse age-related differences in coagulation and fibrinolytic factors in women. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 18: 362–368, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. El-Sayed MS, Sale C, Jones PG, Chester M. Blood hemostasis in exercise and training. Med Sci Sports Exerc 32: 918–925, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Farb A, Burke AP, Tang AL, Liang TY, Mannan P, Smialek J, Virmani R. Coronary plaque erosion without rupture into a lipid core. A frequent cause of coronary thrombosis in sudden coronary death. Circulation 93: 1354–1363, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gough PJ, Gomez IG, Wille PT, Raines EW. Macrophage expression of active MMP-9 induces acute plaque disruption in apoE-deficient mice. J Clin Invest 116: 59–69, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Haskell WL, Lee IM, Pate RR, Powell KE, Blair SN, Franklin BA, Macera CA, Heath GW, Thompson PD, Bauman A. Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Med Sci Sports Exerc 39: 1423–1434, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hilberg T, Gla D, Schmidt V, Losche W, Franke G, Schneider K, Gabriel HH. Short-term exercise and platelet activity, sensitivity to agonist, and platelet-leukocyte conjugate formation. Platelets 14: 67–74, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hilberg T, Menzel K, Glaser D, Zimmermann S, Gabriel HH. Exercise intensity: platelet function and platelet-leukocyte conjugate formation in untrained subjects. Thromb Res 122: 77–84, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ikarugi H, Taka T, Nakajima S, Noguchi T, Watanabe S, Sasaki Y, Haga S, Ueda T, Seki J, Yamamoto J. Norepinephrine, but not epinephrine, enhances platelet reactivity and coagulation after exercise in humans. J Appl Physiol 86: 133–138, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jennings LK. Mechanisms of platelet activation: need for new strategies to protect against platelet-mediated atherothrombosis. Thromb Haemost 102: 248–257, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jolliffe JA, Rees K, Taylor RS, Thompson D, Oldridge N, Ebrahim S. Exercise-based rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD001800, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kadoglou NP, Kostomitsopoulos N, Kapelouzou A, Moustardas P, Katsimpoulas M, Giagini A, Dede E, Boudoulas H, Konstantinides S, Karayannacos PE, Liapis CD. Effects of exercise training on the severity and composition of atherosclerotic plaque in apoE-deficient mice. J Vasc Res 48: 347–356, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kasuya N, Kishi Y, Sakita SY, Numano F, Isobe M. Acute vigorous exercise primes enhanced NO release in human platelets. Atherosclerosis 161: 225–232, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kestin AS, Ellis PA, Barnard MR, Errichetti A, Rosner BA, Michelson AD. Effect of strenuous exercise on platelet activation state and reactivity. Circulation 88: 1502–1511, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li N, He S, Blomback M, Hjemdahl P. Platelet activity, coagulation, and fibrinolysis during exercise in healthy males: effects of thrombin inhibition by argatroban and enoxaparin. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27: 407–413, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li N, Wallen NH, Hjemdahl P. Evidence for prothrombotic effects of exercise and limited protection by aspirin. Circulation 100: 1374–1379, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lindemann S, Klingel B, Fisch A, Meyer J, Darius H. Increased platelet sensitivity toward platelet inhibitors during physical exercise in patients with coronary artery disease. Thromb Res 93: 51–59, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lu Q, Ceddia MA, Price EA, Ye SM, Woods JA. Chronic exercise increases macrophage-mediated tumor cytolysis in young and old mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 276: R482–R489, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lund T, Kvernmo HD, Osterud B. Cellular activation in response to physical exercise: the effect of platelets and granulocytes on monocyte reactivity. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 9: 63–69, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29a. McAllister RM, Newcomer SC, Laughlin MH. Vascular nitric oxide effects of exercise training in animals. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 33: 173–178, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mittleman MA, Maclure M, Tofler GH, Sherwood JB, Goldberg RJ, Muller JE. Triggering of acute myocardial infarction by heavy physical exertion. Protection against triggering by regular exertion. Determinants of Myocardial Infarction Onset Study Investigators. N Engl J Med 329: 1677–1683, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mockel M, Ulrich NV, Heller G, Jr, Rocker L, Hansen R, Riess H, Patscheke H, Stork T, Frei U, Ruf A. Platelet activation through triathlon competition in ultra-endurance trained athletes: impact of thrombin and plasmin generation and catecholamine release. Int J Sports Med 22: 337–343, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mustonen P, Lepantalo M, Lassila R. Physical exertion induces thrombin formation and fibrin degradation in patients with peripheral atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 18: 244–249, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nagashima J, Musha H, Takada H, Matsumoto N, Fujimaki R, Ishige N, Aono J, Murayama M. Influence of physical fitness and smoking on the coagulation system in hypertensive patients: effect on prothrombin fragment F1+2. Intern Med 46: 933–936, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nagy E, Janszky I, Eriksson-Berg M, Al-Khalili F, Schenck-Gustafsson K. The effects of exercise capacity and sedentary lifestyle on haemostasis among middle-aged women with coronary heart disease. Thromb Haemost 100: 899–904, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Napoli C, Williams-Ignarro S, de Nigris F, Lerman LO, D'Armiento FP, Crimi E, Byrns RE, Casamassimi A, Lanza A, Gombos F, Sica V, Ignarro LJ. Physical training and metabolic supplementation reduce spontaneous atherosclerotic plaque rupture and prolong survival in hypercholesterolemic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 10479–10484, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. O'Connor GT, Buring JE, Yusuf S, Goldhaber SZ, Olmstead EM, Paffenbarger RS, Jr, Hennekens CH. An overview of randomized trials of rehabilitation with exercise after myocardial infarction. Circulation 80: 234–244, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Oldridge NB, Guyatt GH, Fischer ME, Rimm AA. Cardiac rehabilitation after myocardial infarction. Combined experience of randomized clinical trials. JAMA 260: 945–950, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ombrello C, Block RC, Morrell CN. Our expanding view of platelet functions and its clinical implications. J Cardiovasc Transl Res 3: 538–546, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pamukcu B, Oflaz H, Acar RD, Umman S, Koylan N, Umman B, Nisanci Y. The role of exercise on platelet aggregation in patients with stable coronary artery disease: exercise induces aspirin resistant platelet activation. J Thromb Thrombolysis 20: 17–22, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Perneby C, Wallen NH, Hofman-Bang C, Tornvall P, Ivert T, Li N, Hjemdahl P. Effect of clopidogrel treatment on stress-induced platelet activation and myocardial ischemia in aspirin-treated patients with stable coronary artery disease. Thromb Haemost 98: 1316–1322, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pynn M, Schafer K, Konstantinides S, Halle M. Exercise training reduces neointimal growth and stabilizes vascular lesions developing after injury in apolipoprotein e-deficient mice. Circulation 109: 386–392, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ribeiro J, Almeida-Dias A, Ascensao A, Magalhaes J, Oliveira AR, Carlson J, Mota J, Appell HJ, Duarte J. Hemostatic response to acute physical exercise in healthy adolescents. J Sci Med Sport 10: 164–169, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Scalone G, Lanza GA, Sgueglia GA, Sestito A, Infusino F, Barone L, Di Monaco A, Aurigemma C, Coviello I, Mollo R, Pisanello C, Andreotti F, Crea F. Predictors of exercise-induced platelet reactivity in patients with chronic stable angina. J Cardiovasc Med 10: 891–897, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shiroma EJ, Lee IM. Physical activity and cardiovascular health: lessons learned from epidemiological studies across age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Circulation 122: 743–752, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Siscovick DS, Weiss NS, Fletcher RH, Lasky T. The incidence of primary cardiac arrest during vigorous exercise. N Engl J Med 311: 874–877, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Steinhubl SR, Moliterno DJ. The role of the platelet in the pathogenesis of atherothrombosis. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 5: 399–408, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Stratton JR, Chandler WL, Schwartz RS, Cerqueira MD, Levy WC, Kahn SE, Larson VG, Cain KC, Beard JC, Abrass IB. Effects of physical conditioning on fibrinolytic variables and fibrinogen in young and old healthy adults. Circulation 83: 1692–1697, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Szymanski LM, Pate RR, Durstine JL. Effects of maximal exercise and venous occlusion on fibrinolytic activity in physically active and inactive men. J Appl Physiol 77: 2305–2310, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tanaka A, Imanishi T, Kitabata H, Kubo T, Takarada S, Tanimoto T, Kuroi A, Tsujioka H, Ikejima H, Ueno S, Kataiwa H, Okouchi K, Kashiwaghi M, Matsumoto H, Takemoto K, Nakamura N, Hirata K, Mizukoshi M, Akasaka T. Morphology of exertion-triggered plaque rupture in patients with acute coronary syndrome: an optical coherence tomography study. Circulation 118: 2368–2373, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Thompson PD, Franklin BA, Balady GJ, Blair SN, Corrado D, Estes NA, 3rd, Fulton JE, Gordon NF, Haskell WL, Link MS, Maron BJ, Mittleman MA, Pelliccia A, Wenger NK, Willich SN, Costa F. Exercise and acute cardiovascular events placing the risks into perspective: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism and the Council on Clinical Cardiology. Circulation 115: 2358–2368, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Thompson PD, Funk EJ, Carleton RA, Sturner WQ. Incidence of death during jogging in Rhode Island from 1975 through 1980. JAMA 247: 2535–2538, 1982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tofler GH, Stone PH, Maclure M, Edelman E, Davis VG, Robertson T, Antman EM, Muller JE. Analysis of possible triggers of acute myocardial infarction (the MILIS study). Am J Cardiol 66: 22–27, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. van den Burg PJ, Hospers JE, van Vliet M, Mosterd WL, Bouma BN, Huisveld IA. Effect of endurance training and seasonal fluctuation on coagulation and fibrinolysis in young sedentary men. J Appl Physiol 82: 613–620, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wang HY, Bashore TR, Friedman E. Exercise reduces age-dependent decrease in platelet protein kinase C activity and translocation. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 50A: M12–M16, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wang JS, Cheng LJ. Effect of strenuous, acute exercise on alpha2-adrenergic agonist-potentiated platelet activation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 19: 1559–1565, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wang JS, Jen CJ, Chen HI. Effects of chronic exercise and deconditioning on platelet function in women. J Appl Physiol 83: 2080–2085, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wang JS, Jen CJ, Chen HI. Effects of exercise training and deconditioning on platelet function in men. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 15: 1668–1674, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wang JS, Jen CJ, Kung HC, Lin LJ, Hsiue TR, Chen HI. Different effects of strenuous exercise and moderate exercise on platelet function in men. Circulation 90: 2877–2885, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wang JS, Liao CH. Moderate-intensity exercise suppresses platelet activation and polymorphonuclear leukocyte interaction with surface-adherent platelets under shear flow in men. Thromb Haemost 91: 587–594, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Weiss C, Bierhaus A, Kinscherf R, Hack V, Luther T, Nawroth PP, Bartsch P. Tissue factor-dependent pathway is not involved in exercise-induced formation of thrombin and fibrin. J Appl Physiol 92: 211–218, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Womack CJ, Nagelkirk PR, Coughlin AM. Exercise-induced changes in coagulation and fibrinolysis in healthy populations and patients with cardiovascular disease. Sports Med 33: 795–807, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Womack CJ, Rasmussen JM, Vickers DG, Paton CM, Osmond PJ, Davis GL. Changes in fibrinolysis following exercise above and below lactate threshold. Thromb Res 118: 263–268, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wosornu D, Allardyce W, Ballantyne D, Tansey P. Influence of power and aerobic exercise training on haemostatic factors after coronary artery surgery. Br Heart J 68: 181–186, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]