Abstract

Chronic exercise attenuates coronary artery disease (CAD) in humans largely independent of reductions in risk factors; thus major protective mechanisms of exercise are directly within the coronary vasculature. Further, tight control of diabetes, e.g., blood glucose, can be detrimental. Accordingly, knowledge of mechanisms by which exercise attenuates diabetic CAD could catalyze development of molecular therapies. Exercise attenuates CAD (atherosclerosis) and restenosis in miniature swine models, which enable precise control of exercise parameters (intensity, duration, and frequency) and characterization of the metabolic syndrome (MetS) and diabetic milieu. Intracellular Ca2+ is a pivotal second messenger for coronary smooth muscle (CSM) excitation-contraction and excitation-transcription coupling that modulates CSM proliferation, migration, and calcification. CSM of diabetic dyslipidemic Yucatan swine have impaired Ca2+ extrusion via the plasmalemma Ca2+ ATPase (PMCA), downregulation of L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCC), increased Ca2+ sequestration by the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA), increased nuclear Ca2+ localization, and greater activation of K channels by Ca2+ release from the SR. Endurance exercise training prevents Ca2+ transport changes with virtually no effect on the diabetic milieu (glucose, lipids). In MetS Ossabaw swine transient receptor potential canonical (TRPC) channels are upregulated and exercise training reverses expression and TRPC-mediated Ca2+ influx with almost no change in the MetS milieu. Overall, exercise effects on Ca2+ signaling modulate CSM phenotype. Future studies should 1) selectively target key Ca2+ transporters to determine definitively their causal role in atherosclerosis and 2) combine mechanistic studies with clinical outcomes, e.g., reduction of myocardial infarction.

Keywords: calcification, proliferation, voltage-gated Ca2+ channel, plasmalemma Ca2+ ATPase, sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase, nucleus, K+ channel, transient receptor potential canonical channel, subcellular localization, Ossabaw miniature swine, Yucatan miniature swine, Göttingen miniature swine

chronic exercise attenuates coronary artery disease (CAD) morbidity and mortality in humans, and nearly two-thirds of the benefit is independent of reductions in traditional risk factors (81). The profound implication is that the major protective mechanisms of exercise are direct actions within the coronary vasculature. Further, intensive control of one CAD risk factor in diabetes, i.e., blood glucose, increased mortality in long-term type 2 diabetes patients (1). These findings indicate that knowledge of the cellular and molecular mechanisms of exercise as an adjunct therapy to prevent diabetic CAD could provide insights into pathogenesis and other molecular therapies.

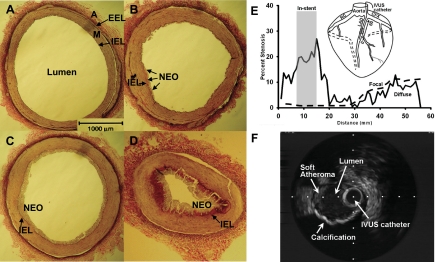

The heterogeneity of macrovascular and microvascular coronary arteries (109) prompts this minireview focus on macrovascular CAD (atherosclerosis) and, more specifically, the role of coronary smooth muscle (CSM) cells. It is also fully recognized that microvascular CAD is a problem in metabolic syndrome and diabetes. Atherosclerotic CAD progresses through stages shown in Fig. 1 (see Refs. 94 and 109 for review). The completely healthy stage of an epicardial conduit coronary artery is characterized by medial CSM cells in their differentiated contractile state with a single layer of endothelium comprising the intima (Fig. 1A). This is almost never seen in the average person beyond adolescence in Western society. Instead, because of the presence of copious systemic risk factors, including sedentary lifestyle, thin layers of neointima form when lipids and other factors infiltrate the artery (Fig. 1B). The progression continues unabated to form often concentric, thicker neointima with increasing numbers of macrophages that are more lipid laden and transformed to foam cells (Fig. 1C). In addition to the neointima, the vascular media thickens due to CSM proliferation. More severe, complex lesions form in later stages in which CSM proliferation and migration into the neointima accelerate and fibrosis and calcification increase to form a flow-limiting stenosis (Fig. 1D) (76, 94, 109). Eccentric, complex lesions also include areas of soft atheroma and calcification (Fig. 1F). The severity and complexity of atherosclerotic lesions varies according to the magnitude of dyslipidemia and other CAD risk factors and the duration of exposure to the systemic risk factors (48). If the fibrosis and calcification do not form stable lesions, a more lipid-laden core may have just a thin fibrous cap and be susceptible to rupture (16, 76, 127). Such unstable, vulnerable plaque is the major cause of acute myocardial infarction characterized by ST segment elevation in the electrocardiogram and requiring revascularization with percutaneous balloon angioplasty and stenting or coronary bypass surgery. Despite these treatments, survivors of myocardial infarction face >10-fold increased risk of progression to heart failure and death (115).

Fig. 1.

Progression of macrovascular coronary artery disease (CAD; atherosclerosis) in swine. Verhoeff van Giesen's staining of epicardial coronary conduit arteries. A: healthy, lean. B–D: varying degrees of atherosclerosis after 20 wk of diabetic dyslipidemia. Variability in lesion severity in these examples is due to the varying degree of diabetic dyslipidemia between animals. B: early stage showing very mild neointimal thickening. C: more developed and concentric, thicker neointimal thickening. D: more advanced stages of atherosclerosis with severe intimal thickening, foam cell accumulation, and luminal occlusion. E: diffuse CAD and in-stent stenosis (gray shaded vertical bar) quantified by intravascular ultrasound analysis of percent stenosis longitudinally through 60 mm length of an artery in a MetS Ossabaw pig. A schematic representation of more focal CAD in a hyperlipidemic Yucatan pig that is not insulin-resistant is shown by the dashed line. Inset shows IVUS catheter placed in LAD artery for interrogation of the artery. F: intravascular ultrasound image showing a complex lesion with soft atheroma and eccentric, profound calcification in MetS Ossabaw swine demonstrated by the dropout of the ultrasound signal peripheral to the calcified arc. Dots are 1-mm spacing. A, adventitia; EEL, external elastic lamina; M, media; IEL, internal elastic lamina; NEO, neointima; RC, right coronary; LAD, left anterior descending; CFX, circumflex; cross-hatched segment on LAD, stent placement; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound. [Dr. M. Richardson worked on the preparation of Fig. 1 and grants permission for its publication.]

METABOLIC SYNDROME AND DIABETES AS MAJOR RISK FACTORS FOR CAD

Rapid and robust accumulation of fat depots enabled by “thrifty” genes (22) was a natural, beneficial adaptation in earlier human cultures to adapt to feast and famine ecology, but the “thrifty genotype” is detrimental in our modern era of plentiful food sources and minimal physical activity. Extreme physical inactivity and poor diet that are now commonplace in modern lifestyles amplify manifestation of a thrifty genotype, as up to 27% of adults in the United States have obesity-associated metabolic abnormalities (34) and even young children are affected (104). Key components of the pathologies are propensity to central (intra-abdominal) obesity, insulin resistance, impaired glucose tolerance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension (38, 53, 104). Although the definition and precise clinical utility have recently been controversial (53), generally the presence of three of these characteristics renders a diagnosis of metabolic syndrome (MetS; “prediabetes”) (38). The diagnosis of type 2 diabetes is rendered by an increase in fasting plasma glucose, which typically occurs after >10 years in the prediabetic/MetS stage.

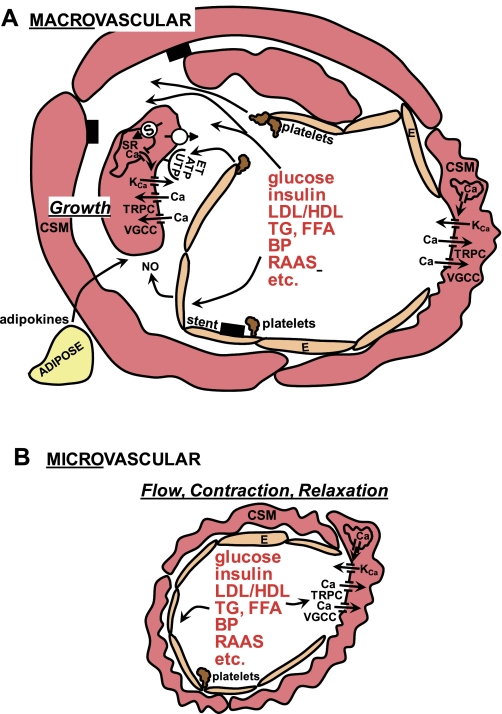

Hyperglycemia, hyper- and hypoinsulinemia, increased ratio of low-density lipoprotein to high-density lipoprotein (LDL/HDL) cholesterol, triglycerides (TG), and free fatty acids (FFA) are major components of the systemic MetS and diabetic milieu (Fig. 2; Refs. 37, 70, 94). In addition, chronic inflammation is thought to be key to macrovascular CAD (70, 94). A plethora of “outside-in” risk factors from perivascular adipose tissue (adipokines) represent another source of atherogenic factors (92, 98). A central concept is that MetS and diabetes increase CAD by damaging the coronary endothelium, which normally inhibits CSM contraction, migration, and proliferation (Fig. 2A; Ref. 94). Similar factors are thought to alter the contraction and relaxation of CSM in the microvasculature that regulates coronary blood flow (Fig. 2B). Aggregating platelets release a variety of growth factors, including ATP and UTP, and the dysfunctional endothelium allows these and other mitogens and the atherogenic milieu to stimulate CSM via several receptor signaling systems and ion channels as shown in the model in Fig. 2A, and this will be covered in more detail in the next sections. These tonic modulatory functions of the endothelium are mediated by the production and/or release of several vasoactive factors, collectively referred to as endothelium-derived relaxing factors [EDRFs; e.g., nitric oxide (NO), prostacyclin] and endothelium-derived contracting factors [EDCFs; e.g., endothelin (ET)] (for review see Ref. 94). The processes of migration and proliferation of CSM as key steps in atherosclerosis (94) involve dedifferentiation of the cells from their normal contractile phenotype to a synthetic, phenotypically modulated cell (90). Although contraction of CSM in a conduit artery (Fig. 2A, right) that results in coronary vasospasm is potentially life-threatening, it is a lesser problem clinically than atherosclerosis (106). MetS and type 2 diabetes patients are generally found to have increased activity of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS, Ref. 21; Fig. 2), which further adds to the complexity of the milieu because of the contribution to “obesity hypertension” (Fig. 2; blood pressure; BP) (40). Type 1 diabetes, in contrast, generally involves less extreme dyslipidemia and RAAS activation and greater hyperglycemia compared with MetS and type 2 diabetes (21, 37, 70, 94, 105). Although the “ABCs” of diabetes treatment, i.e., hemoglobin A1C (glucose), blood pressure, and cholesterol management, can attenuate cardiovascular disease (1), adherence is difficult and costly, and intensive glycemic control could not be generally recommended for long-term, established type 2 diabetes due to increased mortality (1).

Fig. 2.

Schematic showing the systemic metabolic syndrome (MetS) and diabetic milieu impinging on coronary macro- and microvasculature and Ca2+ signaling mechanisms. A: macrovascular CSM is largely involved in dedifferentiation, growth, and calcification underlying atherosclerosis. The MetS and diabetic milieu stimulate the endothelium and platelet aggregation to release factors that activate mitogenic receptors, such as those for endothelin (ET), and nucleotides (e.g., ATP, UTP). Compromised integrity of the endothelial barrier also permits more direct interaction of the MetS and diabetic milieu with CSM to modulate Ca2+ signaling mechanisms and contribute to atherosclerosis (CSM on left side of artery). Although contraction (CSM on right side of artery) can lead to coronary vasospasm, the greater clinical problem is atherosclerosis. B: microvascular CSM mainly regulate coronary blood flow by contraction and relaxation. Structural remodeling occurs, but the processes are not the same as in macrovascular CSM dedifferentiation. Microvascular CSM is exposed to the MetS and diabetic milieu, similar to macrovascular CSM, which modulate contraction and relaxation, largely by actions on Ca2+ signaling mechanisms. See text for more details. CSM, coronary smooth muscle; E, endothelium; LDL/HDL, low-density lipoprotein to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG, triglycerides, FFA, free fatty acids; BP, blood pressure; RAAS, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system; NO, nitric oxide; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum; S = SERCA = sarcoplasmic-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase; open circle, Ca2+ extrusion mechanisms (plasmalemmal Ca2+ ATPase and Na+/Ca2+ exchange); KCa, Ca2+-activated K channels; TRPC, transient receptor potential canonical channels; VGCC, voltage-gated Ca2+ channels; black rectangles, stent.

Despite significant improvements, CAD remains the leading cause of death in our society and is greatly exacerbated in MetS and diabetes (33). Because MetS is increasing in prevalence in our society to levels widely considered epidemic (128), more widespread progression of patients to type 2 diabetes will compound CAD morbidity and mortality, since CAD further increases to fourfold higher in diabetic vs. nondiabetic patients (27). Progression of CAD is greater in MetS and diabetes partly because of the pervasive “diffuse CAD” that is a hallmark of diabetic CAD (15, 82, 83), which was highlighted in a recent pooled analysis (87). Diffuse CAD argues for more systemic therapy afforded by exercise as opposed to localized treatment with coronary angioplasty and stenting.

CHRONIC EXERCISE-INDUCED ADAPTATIONS

Exercise is one of the first-line treatments for thus preventing or delaying the onset of type 2 diabetes, and decreases plasma lipids, blood pressure, cardiovascular events, and mortality (19). Given the multiple risk factors for CAD (Fig. 2, above), the integrative effects of exercise seem to be a substantial adjunct to pharmacotherapy, which would require a “polypill” for such widespread benefit on multiple risk factors. Haskell et al. (42) were one of the first to report profound effects of exercise on coronary arteries in which they showed ultradistance runners had greater coronary artery diameters at rest and after maximal nitroglycerin-induced vasodilation, suggesting that exercise training in humans elicited structurally larger coronary arteries due to vascular remodeling. Hambrecht and coworkers showed attenuation of plaque formation (99) and improved event-free survival in patients after angioplasty (41). Belardinelli et al. (3) found that exercise training decreased restenosis progression and the natural progression of CAD in arterial segments proximal and distal to the stent, i.e., decreased peri-stent CAD. Unfortunately, few human studies have included sufficient numbers of MetS or diabetic (type 1 or type 2) patients, nor have they studied cellular and molecular mechanisms (3; for review see 30).

Rigorous assessment of CAD.

Overall, these significant, but relatively modest, effects on plaque progression and regression in humans do not account fully for the remarkable relief of symptoms of CAD and improved event-free survival. Since vulnerable plaque rupture is the major cause of acute myocardial infarction (above), exercise training-induced plaque stabilization may be much more important than reduction in stenosis (16). Studies that employ high-resolution imaging methods such as intravascular ultrasound, optical coherence tomography, magnetic resonance, near-infrared imaging, and others that enable chemical resolution of collagen and lipid (e.g., 125) will be needed for thorough characterization of the effects of exercise on CAD (127). Further, longitudinal measures of CAD, not just at the end of the study, will provide the most insights into CAD progression and regression (88).

Animal model of CAD, exercise, and the “diabetic milieu”.

Invasive studies of cellular and molecular mechanisms of exercise effects on CAD require appropriate animal models. Phenomenal work has been done on transgenic and gene ablation (knockout) mouse models to understand mechanisms of MetS and diabetes, as summarized from work of the Animal Models for Diabetic Cardiovascular Complications (AMDCC) (49). However, transgenic mouse models are simply not adequate for studying CAD, not to mention vascular interventions using stents and catheter devices identical to those used in humans (28, 31, 74, 107, 116, 127), which are essential for translation to the clinic. Further, animal models that develop mature, clinically significant atheroma will provide vast improvement over studies that employ injury of healthy arteries (116). Particularly important for the study of diabetic CAD is use of a model that displays diffuse CAD, which is the hallmark (15, 82, 83, 87). Intravascular ultrasound assessment of CAD in Ossabaw miniature swine with MetS enables interrogation of much of the artery as shown in Fig. 1E. In this example, automated pullback of the intravascular imaging transducer along 60 mm of the coronary shows diffuse stenosis along much of the coronary artery. As predicted, in-stent stenosis is clearly greater along the 8-mm length of the stent compared with other segments of the artery. A more focal CAD occurs in hyperlipidemic Yucatan miniature swine that are not insulin-resistant, as shown by the percent stenosis decreasing to nearly zero in more distant artery segments (84). Progression to clinically detectable coronary calcification is shown in MetS Ossabaw swine in Fig. 1F (84). Although arterial calcium deposition has been shown microscopically in swine models postmortem (36, 125), detection by clinically used intravascular ultrasound in living animals is a significant milestone. Finally, in addition to the study of basic cellular and molecular mechanisms by invasive methods, animal models should ideally include hard clinical endpoints, such as spontaneous myocardial infarction and mortality for translation to the clinic (e.g., 115).

Link et al. (71) nearly 40 years ago reported that exercise training of domestic swine attenuated CAD and Kramsch et al. (55) showed profound regression of mature atherosclerosis in nonhuman primates. More recent studies by Fleenor and Bowles (31), Long et al. (74), and Edwards et al. (29) showed that exercise training profoundly decreased restenosis and native atherosclerosis progression. These are particularly strong studies because the exercise stimulus prescription was well quantified by intensity, duration, frequency, and total duration of training. Classical training adaptations were elicited, including lower resting heart rate and exercise heart rate at a submaximal workload, increased physical work capacity, and skeletal muscle oxidative enzymes (31, 74). These studies validate by widely accepted exercise training criteria the use of large animal models to study exercise and CAD (20). The next step is to superimpose MetS and diabetes on the background to elicit CAD. Studies to date have all been performed on swine.

The MetS and diabetic milieus have qualitative, quantitative (severity), and duration differences in animal models and it is essential that one be cognizant of these variables for interpretation of exercise study outcomes and CAD mechanisms (6, 29, 36). Table 1 compares Yucatan, Ossabaw, and Göttingen miniature swine, which are collectively the most widely used miniature swine breeds for laboratory animal medicine for MetS, diabetic dyslipidemia, CAD, and exercise training studies. Direct, quantitative comparisons are not ideal because no single study has systematically compared the three breeds when controlling for age, sex, diet composition calories, and duration of treatment. Neeb et al. (84) compared only Yucatan and Ossabaw using precisely matched conditions. The measures of MetS and diabetes are also not the same, e.g., intravenous glucose tolerance test or fasting values or glucose clamp (17, 29, 63, 89), which makes quantitative comparisons between all studies tenuous. See also the review by Varga et al. that encompasses swine and other animal models of MetS (120). Table 1 summarizes the six key components of MetS schematically shown in Fig. 2, progression to type 2 diabetes (item 7), and the incidence of CAD (item 8). 1) The first major characteristic of MetS is obesity. Yucatan pigs could be made only mildly obese by consumption of excess calorie atherogenic diet; in contrast, Ossabaw and Göttingen pigs are superior for studying the pathogenesis of obesity and related disorders. 2) Yucatan miniature swine do not naturally develop obesity-associated insulin resistance. 3) As insulin resistance is a precursor to glucose intolerance, Ossabaw and Göttingen pigs also show marked increases elicited by excess calorie diet. 4) A high fat and cholesterol diet elicits dyslipidemia (hypercholesterolemia) in domestic (36) and all three miniature swine breeds that are almost exclusively used in laboratory animal medicine and exercise studies (17, 24, 25, 52, 52, 77, 78, 130, 132). 5) The increased plasma triglycerides noted only in Ossabaw and Yucatan are probably linked to the decreased insulin action. Several decades of work on domestic and Yucatan breeds have shown no increase in plasma triglycerides, until atherogenic diet was combined with impaired insulin action in these breeds by chemically induced diabetes (e.g., 36, 67; and see below). 6) Genetically leaner Yucatan pigs made mildly obese and hyperlipidemic by consumption of excess calorie atherogenic diet did not become hypertensive (11, 130) and blood pressure measures have not been reported for Göttingen. In summary, Ossabaw miniature swine fed a high-caloric diet display a natural pathogenesis of all MetS characteristics (84). 7) Yucatan and Göttingen swine do not progress to type 2 diabetes (e.g., 63, 89, 93). Ossabaw pigs develop type 2 diabetes as evidenced by a significantly increased fasting plasma glucose of ∼30% above healthy lean pigs. This degree of fasting hyperglycemia clearly shows only the earliest diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and is not nearly the magnitude commonly found in type 2 diabetic humans (1) or in rodent models (37, 120); thus, longer duration is probably needed to elicit robust type 2 diabetes in Ossabaw swine. Göttingen pigs, however, will reliably develop mild MetS (17, 52, 63). Although outstanding work shows that a line of cross-bred domestic pigs with familial hypercholesterolemia will develop MetS (5), use of the standard-sized domestic swine is not practical because they weigh >250 kg and are 2 yr of age before type 2 diabetes develops. A 250-kg pig is not amenable to use of conventional treadmill exercise equipment and angiography instrumentation needed for clinically relevant atherosclerosis assessment and stent deployment. 8) All three breeds develop CAD (coronary atherosclerosis) when fed an atherogenic diet. CAD is more widely documented in Yucatan and Ossabaw breeds (e.g., 84), while there are few studies of atherosclerosis in Göttingen (50) and Göttingen-Yucatan cross-bred pigs (47). There are no studies of coronary catheter interventions in lean Göttingen pigs, almost certainly due to the diminutive size of only ∼20–30 kg, which would preclude use of standard human clinical devices. Direct, carefully controlled comparison showed that Ossabaw developed more extensive and diffuse CAD and restenosis responses to stenting than Yucatan pigs (84). In Yucatan and Ossabaw pigs exercise training attenuated CAD. Highlights of the MetS and type 2 diabetes section of Table 1 are underlined. The finding that dyslipidemia, in the absence of insulin resistance or hyperglycemia, elicited CAD in Yucatan pigs affirms a major role for plasma lipids. Despite the outstanding metabolic data in the Göttingen, there is a paucity of cardiovascular and CAD data (47, 50) and there have been no exercise training studies.

Table 1.

Metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and coronary artery disease characteristics in Yucatan, Ossabaw, and Göttingen miniature swine

| Characteristic | Yucatan | Ossabaw | Göttingen | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, coronary artery disease | ||||

| 1) Obesity | No | Ossabaw∼Göttingen>Yucatan | Ossabaw∼Göttingen > Yucatan | 6, 11, 14, 17, 18, 26, 32, 52, 56, 63, 64, 68, 84, 107, 129 |

| 2) Insulin resistance | No | Yes | Yes | 4, 26, 29, 35, 52, 63, 64, 68, 84, 89, 107, 130 |

| 3) Glucose intolerance (or impaired glucose tolerance, [IGT]) | No | Yes | Yes | 6, 11, 14, 24, 26, 29, 35, 52, 63, 64, 68, 78, 84, 89, 107, 129, 130, 132 |

| 4) Dyslipidemia (↑LDL/HDL or ↑LDL/TC) | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4, 14, 18, 24, 26, 29, 35, 47, 50, 52, 64, 67, 68, 84, 95, 107, 132 |

| 5) Dyslipidemia (↑triglycerides) | No | Yes | Yes | 4, 14, 18, 24, 26, 29, 35, 45, 52, 64, 68, 78, 95, 107, 129, 130 |

| 6) Hypertension | No | Yes | No data | 11, 14, 26, 29, 89, 107 |

| 7) Type 2 diabetes (fasting hyperglycemia) | No | Yes | No | 8–10, 14, 29, 52, 63, 68 |

| 8) Coronary artery disease | Yes | Yes; >Yucatan | Yes | 6, 8–10, 14, 14, 24, 26, 28, 29, 39, 47, 50, 56, 60, 66, 73, 75, 77, 78, 84, 91, 92, 107, 107, 117, 123, 125, 126, 133 |

| CAD attenuated by exercise | Yes | Yes | No data | 29, 31, 71, 74 |

| Diabetes (toxin-induced type 1) and dyslipidemia, coronary artery disease | ||||

| 1) Obesity | No | No data | Göttingen > Yucatan | 11, 61, 65, 89, 129 |

| 2) Insulin resistance | Yes; secondary | No data | Yes | 61, 65, 89 |

| 3) Glucose intolerance (or impaired glucose tolerance, [IGT]) | Yes | No data | Yes | 61, 65, 89 |

| 4) Dyslipidemia (↑LDL/HDL or ↑LDL/TC) | Yes | No data | No data | 24, 44, 67, 77–79, 96, 123, 129, 130 |

| 5) Dyslipidemia (↑ triglycerides) | Yes | No data | No data | 24, 44, 67, 78, 96, 123, 130 |

| 6) Hypertension | No | No data | No data | 77, 89 |

| 7) Type 1 diabetes (fasting hyperglycemia) | Yes | No data | Yes | 11, 24, 44, 61, 65, 67, 77–79, 89, 123, 129, 130 |

| 8) Coronary artery disease | Yes; >nondiab. | No data | No data | 24, 67, 78, 79, 123 |

| CAD attenuated by exercise | Yes*; vasomotor | No data | No data | 77–79 |

All studies cited include atherogenic diet (high fat/cholesterol; often excess calorie). Characteristics 1–6 define metabolic syndrome (MetS) and metabolic abnormalities, and characteristic 7 defines diabetes specifically. All type 1 diabetes models required pancreatic beta cell-selective toxins alloxan or streptozotocin. “No data” denotes that there were no studies or the study did not include these measures. LDL; low-density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; TC, total cholesterol.

Conduit artery vasomotor responses were attenuated, not atherosclerosis. Highlighted entries are underlined.

Inducing type 1 diabetes (plus or minus dyslipidemia) is relatively straightforward in swine by pancreatic beta cell toxins streptozotocin or alloxan, which yield within ∼24 h plasma glucose values ranging from 200 to 400 mg/dl, depending on the specific doses of toxin (e.g., 11, 25, 36, 62, 89; Table 1, item 7). The lesser role of glucose in atherosclerosis (36, 78) was the reason for including in Table 1 only studies using the combination of chemically induced diabetes and atherogenic diet to promote dyslipidemia, while excluding studies of purely toxin-induced diabetic (hyperglycemic) and normolipidemic pigs when fed normal low-fat/-cholesterol diet. The comparisons in Table 1 exclude Ossabaw swine because they have been used solely for studies of the natural progression of diet-induced obesity, MetS, type 2 diabetes, and CAD; thus there are no data on beta cell toxin-induced models of type 1 diabetes. 1) Similar to the above, the Göttingen shows more robust obesity than Yucatan pigs. 2) Insulin resistance in the Yucatan is secondary to the profound hyperglycemia, not due to primary insulin resistance of peripheral target tissues (mainly skeletal muscle and adipose) (89). In the Göttingen pig insulin resistance is partially due to primary insulin resistance and secondarily due to the streptozotocin destruction of beta cell mass (61, 65). 3) Clearly, when insulin-producing pancreatic beta cells are destroyed, there is profound glucose intolerance. 4) Although there are no data on plasma lipids in the streptozotocin-treated and atherogenic diet-fed Göttingen, it is reasonable to assume that LDL/HDL and triglycerides would be elevated above healthy controls based on data from atherogenic diet feeding alone (50, 52, 64). 5) Increased plasma triglycerides in Yucatan have only been found reliably in chemically induced diabetic pigs, again reinforcing the linkage to decreased insulin action (e.g., 36, 67). 6) It is clear that there is no hypertension in Yucatan swine, despite the extreme diabetic dyslipidemia, thus suggesting other components of the MetS milieu drive hypertension. I could find no data on hypertension in Göttingen pigs. 7) Fasting hyperglycemia in graded severity has been achieved in several studies and, despite chemically induced diabetes being an artificial experimental intervention, not natural pathogenesis, this diabetes model is an excellent means of studying the effect of the very extreme diabetic dyslipidemic milieu on CAD. 8) CAD in diabetic dyslipidemic Yucatan was greater than in normoglycemic (nondiabetic) dyslipidemic pigs when postprandial lipids were not greater than fasting (36, 67), thus validating the swine model by its mimicry of the greater CAD in diabetic humans (15, 27, 82, 83). However, when postprandial lipids (i.e., triglycerides) were much greater than fasting due to a “gorging” meal regimen (130), then diabetes (hyperglycemia) did not further exacerbate the CAD (78). There are no data in Göttingen pigs. It is important to note (asterisk in Table 1) that the only measures of exercise training attenuation of macrovascular and microvascular CAD were decreases in vasomotor impairment, not atherosclerosis (77–79). Exercise training has not been studied in the Göttingen pig. A summary of the diabetic dyslipidemia section of Table 1 is the preponderance of metabolic and CAD data in the Yucatan pig, while there is a paucity of CAD data in the Göttingen and no data whatsoever on Ossabaw swine. A striking observation overall is that exercise training had almost no effect on metabolic parameters (insulin resistance, glucose regulation, lipids, hypertension) in Yucatan and Ossabaw swine, yet there was attenuation of CAD (29, 31, 71, 74, 77–79).

The importance of the diabetic milieu is epitomized by the greater susceptibility of microvasculature to glucose toxicity shown in other animal models (37) and humans in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial [DCCT (114)]. In contrast, it was clearly shown that dyslipidemia is a much greater factor than hyperglycemia in macrovascular CAD (atherosclerosis) in swine models (36, 78), consistent with the greater CAD in type 2 diabetic humans who are generally more dyslipidemic compared with type 1 diabetics (105). Another example of the potentially major impact of the specific diabetic milieu on CAD is that increased aldosterone is more predominant in MetS and type 2 diabetes compared with type 1 diabetes (21, 94) and aldosterone is a powerful inducer of coronary calcification (51, 76). Further, the RAAS activation in MetS could explain why “obesity hypertension” is found in the Ossabaw swine model (40). Because most of exercise training-induced cardioprotection is not due to reduction of traditional risk factors (81), the diabetic milieu must be well characterized to draw the conclusion that exercise effects are partly due to direct actions on the vasculature. Studies in experimental animals described in the next section provide support for this.

CORONARY SMOOTH MUSCLE (CSM) Ca2+ REGULATION

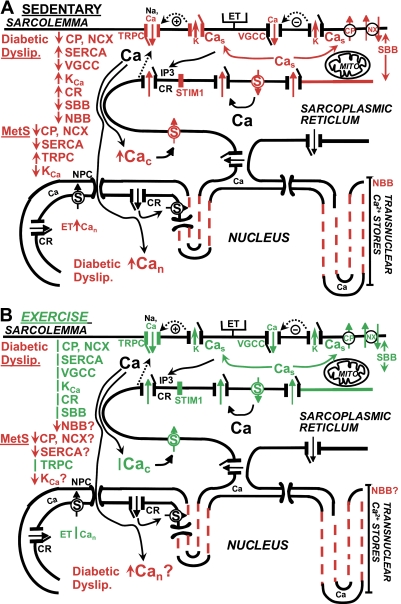

It is clear that cytosolic Ca2+ is a primary regulator of smooth muscle contraction and Ca2+ signaling is involved in “phenotypic modulation” of CSM (90), characterized by proliferation and migration in several in vitro cell culture models (46, 121, 122). Although the focus here is Ca2+ signaling, I recognize that there are numerous other mechanisms contributing to atherosclerosis (e.g., platelet aggregation and release of growth-promoting and vasoactive molecules, lipid accumulation, adhesion molecules, macrophage invasion, immune response, increased extracellular matrix production, etc.). Rapidly proliferating CSM are characterized by decreased smooth muscle myosin and actin contractile proteins (90), decreased contraction (90), increased amount and perinuclear distribution of sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) (46, 90, 123), altered membrane ionic signaling mechanisms, and increased DNA synthesis (90). Phenotypic modulation of CSM in atherosclerosis also involves dedifferentiation to a more osteogenic phenotype that contributes to vascular calcification (51, 76). Underwood et al. (118) and Bowles and Wamhoff (13) reviewed CSM Ca2+ regulation in exercise, but not in CAD. In essence, they considered how exercise converted CSM in healthy arteries (Fig. 1A) to super-healthy and/or primed the CSM to defend against atherogenic factors. I review salient features of those data on healthy CSM that have bearing on CSM Ca2+ regulation in MetS and diabetes, which are summarized schematically in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Schematic model of Ca2+ regulation abnormalities in macrovascular CSM in diabetic dyslipidemia and MetS and attenuation of abnormalities by exercise training. A: sedentary. CSM cells from a sedentary pig show abnormalities of at least 10 Ca2+ regulatory processes, proteins, and membrane domains that influence Ca2+ signaling. The red font and structures denote functional and molecular changes (actual protein expression or membrane domain differences). For example, SERCA function and SERCA2b protein (S) are increased in diabetic dyslipidemia. There is a retraction of the SR from the sarcolemma (long red arrow), thereby impairing the superficial buffer barrier (SBB) function. Overall, decreased Ca2+ extrusion via the plasmalemmal Ca2+ pump and Na+/Ca2+ exchange is a major defect in Ca2+ regulation. SERCA and KCa channel function increase, including a closer coupling of Ca2+ release from caffeine-sensitive SR Ca2+ release channels and increased subsarcolemmal Ca2+ (Cas), perhaps partially compensating for other defects. [The IP3-sensitive and caffeine/ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ release channels (CR) are shown generically as one channel for simplicity, but are not the same molecular entity.] Voltage-gated Ca2+ channel current is downregulated. The net effect of these Ca2+ regulation abnormalities is increased cytosolic Ca2+ (↑Cac). The transnuclear SR membrane is retracted (dashed lines), thereby impairing the nuclear buffer barrier (NBB), and is associated with increased localized nuclear Ca2+ (↑Can) responses to endothelin in diabetic dyslipidemia. CSM in MetS have impaired Ca2+ extrusion and SERCA pump function. TRPC channel functional Ca2+ influx (red arrow in channel) and TRPC1 isoform protein expression (red channel structure) are increased, which are very closely associated with increased STIM1 protein expression. There is decreased KCa channel function, despite increased molecular expression. The precise subcellular localization of Ca2+ transport molecules and processes is emphasized for the crucial role in CSM function. B: exercise training. Aerobic exercise training attenuates 8 of the abnormalities in Ca2+ transport protein and membrane domains. The green font and structures denote those changed by exercise training. For example, the shorter double green arrow shows the shorter distance of the SR from sarcolemma after exercise training, thus attenuating the defect in SBB. The effects of exercise training on Ca2+ regulation are relatively independent of changes in the diabetic dyslipidemia or MetS milieu (shown by the red letters). There have been no studies to determine whether exercise attenuates abnormalities of the NBB, plasmalemmal Ca2+ pump and Na+/Ca2+ exchange, SERCA, KCa channels, or Can (shown by “?”). See text and Table 2 for more details. ET, endothelin, receptor; TRPC, transient receptor potential canonical channels; VGCC, voltage-gated Ca2+ channels; CP, plasmalemma Ca2+ ATPase (PMCA pump); NX, Na+/Ca2+ exchange; KCa, Ca2+-activated K channels; Cas, subsarcolemmal Ca2+; Mito, mitochondria; IP3, inositol trisphosphate; STIM1, stromal interaction molecule type 1; CR, ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ release channels; Cac, cytosolic Ca2+; NPC, nuclear pore complex; Can, nuclear Ca2+; MetS, metabolic syndrome; S = SERCA = sarcoplasmic-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum; +, hyperpolarization-induced stimulation of ion flux; −, hyperpolarization-induced inhibition of channel opening; ↑, increased; ↓, decreased; |, attenuated or returned diabetic dyslipidemia- or MetS-induced changes toward normal; red dashed lines, retracted transnuclear SR.

Ca2+ regulation in healthy CSM.

Studies of CSM from Yucatan and domestic swine have been conducted over the past almost 20 years. I focus on CSM from sedentary animals and ignore the changes in diabetic dyslipidemia and MetS in Fig. 3A, left. In all cases the data summarized in Fig. 3 are from direct functional measures of intracellular free Ca2+ with fluorescent indicators (fura-2, fura red, fluo-4) using widefield epifluorescence and confocal microscopy, patch-clamp electrophysiology of ion channels (including simultaneously with imaging), and molecular measures of protein and mRNA expression. Use of acutely isolated CSM cells, instead of cultured cells exposed to “diabetic milieu,” provide more confidence that the findings represent most closely Ca2+ regulation in the intact organism. There is almost uniform agreement that localized subsarcolemmal Ca2+ (Fig. 3A, Cas) is regulated at higher levels than bulk cytosolic Ca2+ (Fig. 3A, Cac) (103). These gradients of Cac and Cas are largely maintained by a superficial buffer barrier (SBB; Fig. 3A; 109, 119) that involves close proximity of sarcolemmal ion channels and transporters with superficial sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). Ca2+ entering CSM via voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCC; Fig. 3A) is rapidly sequestered by the SR Ca2+ pump (SERCA) superficial SR, thus buffering (attenuating) strongly the rise in Cac (108, 109, 118). Ca2+ influx through ligand-gated channels, now known widely as transient receptor potential canonical (TRPC; Fig. 3A) channels can also refill the SR or participate in excitation-contraction coupling, excitation-transcription coupling, and other processes. Preferential release of Ca2+ from the superficial SR toward the sarcolemma in the regions of the Ca2+ pump and Na+/Ca2+ exchange results in Ca2+ extrusion from CSM, a process that we first termed “SR Ca2+ unloading” (102, 103). The mechanism also includes internal cycling of Ca2+ between the SR and another intracellular Ca2+ store during SR Ca2+ unloading (131). Mitochondria (Fig. 3A) was suspected as the store, but selective inhibitors of mitochondrial Ca2+ transport were not used to clearly identify the store. Alternatively, superficial SR Ca2+ release and occurrence of localized “Ca2+ sparks” can be coupled to stimulation of large-conductance, Ca2+-activated K+ channels. The hyperpolarization acts as a negative feedback system to close VGCC, thereby decreasing Ca2+ influx (Fig. 3A, KCa; circled minus sign, and dashed line; 77, 78, 86, 103). This functional association of Ca2+ sparks and KCa is another prime example of vascular heterogeneity, as microvascular CSM has strong coupling of Ca2+ sparks and KCa, while healthy conduit CSM has minimal coupling (77, 109). Conduit CSM displays very intricate morphology of the transnuclear SR, which functionally forms a nuclear buffer barrier (NBB; Fig. 3A; 109, 121, 123). The specificity of CSM Ca2+ signaling is further reinforced by comparing the effects of receptor agonists. For example, endothelin elicits a substantial release of Ca2+ from the SR, which decays to nearly baseline levels (67, 121, 123). The results are CSM proliferation and the most efficacious contraction of any coronary vasoactive agent. In contrast, although the UTP-induced Ca2+ transient in CSM of in vitro organ cultured arteries is robust and similar in amplitude as the response to endothelin, the UTP-induced Ca2+ transient does not elicit contraction of CSM (46); instead, the Ca2+ transient and kinase activation elicit CSM proliferation only (101). This principle of specificity is applicable to the effects of MetS, diabetic dyslipidemia, and exercise training.

Exercise training effects on CSM Ca2+ regulation in diabetic dyslipidemia.

The past decade of work has shown altered regulation of several domains of intracellular free Ca2+ in diabetic dyslipidemia. I show the spatial relationships in Fig. 3A and list the many changes in Table 2, bottom [Diabetes (toxin-induced type 1) and dyslipidemia] because there are at least 10 Ca regulatory processes, proteins, and membrane domains that influence Ca signaling and the diabetic milieu is different in the studies of diabetic dyslipidemic Yucatan pigs. Cytosolic Ca2+ (Cac) and nuclear Ca2+ (Fig. 3A, Can) are modulated by several Ca2+ transporters in diabetic dyslipidemia-induced CAD. The sarcolemmal Ca2+ pump (CP; Fig. 3A) appears to be the first Ca2+ transporter to be impaired in diabetes (130), along with loss of the coupling of SR Ca2+ release from ryanodine-sensitive SR Ca2+ channels (CR; Fig. 3A) to Ca2+ extrusion via the sarcolemmal Ca2+ pump and Na+/Ca2+ exchange (NX; Fig. 3A). The coupling is functional and physical, as digital imaging of fluorescent markers of the SR and sarcolemmal shows that the SR retracted significantly from the sarcolemma (Fig. 3A, red double arrow; 130). The distance of the SR from sarcolemma was returned to healthy control after exercise training of diabetic dyslipidemic pigs (Fig. 3B, green double arrow; 130). Conduit (macrovascular) CSM may compensate for the defective Ca2+ extrusion by the upregulation of KCa channels in the sarcolemma that are activated by Ca2+ sparks and other Ca2+ release from the SR (77, 78). These large and transient KCa currents activated are referred to as spontaneous transient outward currents (STOCs) (72, 77, 78, 86, 103). It is worth noting the analogous result that aldosterone hypertensive rats had profoundly increased KCa (72). The upregulation of KCa channels was clearly a compensatory response to increased Ca2+ influx through VGCC (72), as inhibition of KCa channels caused more membrane depolarization in hypertensive compared with normotensive rats (72). Microvascular CSM, in contrast, showed profound downregulation of Ca2+ sparks and KCa in diabetic dyslipidemia, thus attesting to the marked heterogeneity of CSM Ca2+ regulation (77). Another compensation for impaired Ca2+ extrusion is an upregulation of the SR Ca2+ pump protein and function (S; Fig. 3A), which is manifest as greater buffering (attenuation) of the rise in cytosolic Ca2+ that occurs during Ca2+ influx (44, 45, 132). Our results seem at odds with the downregulation of SERCA function and protein in aortic smooth muscle from grossly hyperlipidemic and atherosclerotic rabbits (2). The apparent discrepancy strongly reinforces the concept that the time course and severity of disease are crucial to interpretation of findings on Ca2+ regulation mechanisms. The CAD in our studies on diabetic dyslipidemic Yucatan pigs was relatively mild (44, 45, 132) compared with the gross atherosclerosis in the rabbits (2). Our studies in Yucatan and Ossabaw swine CSM show that Ca2+ modulation by SERCA function progresses from increased function (compensation) in mild/moderate atherosclerosis to severe dysfunction with more severe disease elicited by coronary stenting in atherosclerotic pigs (84) (Table 2). Collectively, these studies show that Ca2+ transporter changes can be beneficial in an attempt to compensate for an adverse change (defect) in another transporter. Adaptations in Ca2+ regulatory mechanisms should not be taken uniformly as causing CAD in diabetes.

Table 2.

Coronary vascular smooth muscle Ca2+ signaling abnormalities in Yucatan and Ossabaw miniature swine and effects of exercise training

| Yucatan |

Ossabaw |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Sedentary1 | Exercise1 | Sedentary | Exercise | References |

| Metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes | |||||

| 1) Plasmalemmal Ca2+ pump | No Δ | No data | ↓2 | No data | 84, 130, 132 |

| 2) Na+/Ca2+ exchange | No Δ | No data | ↓2 | No data | 84, 130, 132 |

| 3) SERCA | NoΔ mild CAD; ↑moderate CAD | No data | ↑Moderate CAD; ↓severe CAD | No data | 84, 130, 132 |

| 4) Voltage-gated Ca2+ channel | ↓ | No data | No data | No data | 12, 132, |

| 5). TRPC channel, store-operated Ca2+ entry | Absent | Absent | ↑ | | | 29, 132 |

| 6) STIM1 | No data | No data | ↑ | | | 29 |

| 7) KCa channel | ↑ | No data | ↓ | No data | 8, 78 |

| 8) SR Ca2+ release | No Δ, ↑3 | No data | No Δ | No data | 29, 67, 78 |

| 9) Superficial buffer barrier (SBB) | ↓ | No data | No data | No data | 130 |

| 10) Nuclear buffer barrier (NBB) | No data | No data | No data | No data | |

| 11) Increased Cac | ↑ | No data | ↑ | No data | 8, 130, 132 |

| 12) Increased Can | No data | No data | No data | No data | |

| Diabetes (toxin-induced type 1) and dyslipidemia | |||||

| 1) Plasmalemmal Ca2+ pump | ↓ | | | No data | No data | 130, 132 |

| 2) Na+/Ca2+ exchange | ↓ | | | No data | No data | 80, 130, 132 |

| 3) SERCA | ↑ | | | No data | No data | 44, 45, 130, 132 |

| 4) Voltage-gated Ca2+ channel | ↓ | | | No data | No data | 132 |

| 5) TRPC channel, store-operated Ca2+ entry | Absent | Absent | No data | No data | 23, 29 |

| 6) STIM1 | No data | No data | No data | No data | |

| 7) KCa channel | ↑ | | | No data | No data | 77, 78 |

| 8) SR Ca2+ release | ↑4 | | | No data | No data | 67, 78, 123 |

| 9) Superficial buffer barrier (SBB) | ↓ | | | No data | No data | 78, 130 |

| 10) Nuclear buffer barrier (NBB) | ↓ | No data | No data | No data | 123 |

| 11) Increased Cac | ↑ | | | No data | No data | 130, 132 |

| 12) Increased Can | ↑ | No data | No data | No data | 123 |

All studies include excess calorie atherogenic diet (high fat and high cholesterol) feeding. MetS, type 2 diabetes, and diabetic dyslipidemia characteristics are in Table 1. Göttingen are not included because no Ca2+ signaling studies have been done. “No data” denotes that there were no studies or the study did not include these measures. “Absent” indicates no evidence for store-operated Ca2+ entry. TRPC, transient receptor potential canonical channels; KCa, Ca2+-activated K channels; Cas, subsarcolemmal Ca; STIM1, stromal interaction molecule type 1; Cac, cytosolic Ca; Can, nuclear Ca; SERCA, sarcoplasmic-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum; No Δ, no change; ↑, increased; ↓, decreased; |, attenuated or returned MetS- or diabetic dyslipidemia-induced changes toward normal.

Although Yucatan do not meet criteria to be defined as having MetS, data are included because Yucatans have the major component of dyslipidemia.

Plasmalemmal Ca2+ extrusion mechanisms are decreased in “healthy” lean Ossabaw vs. Yucatan (84).

Perhaps surprising is the downregulation of VGCC in CSM of diabetic dyslipidemic pigs (VGCC; Fig. 3A; 132). In contrast, VGCC were upregulated when in vitro monolayer cultures of smooth muscle were exposed to cholesterol (100). The dogma that cholesterol increased VGCC function persisted until refuted by direct patch-clamp data from CSM of hyperlipidemic (12) and diabetic dyslipidemic pigs (132). This is an excellent example of how results can differ dramatically from native preparations vs. cell culture and whenever available the results from more physiological native CSM preparations or phenotypically characterized smooth muscle should receive higher priority. The downregulation of VGCC in diabetic dyslipidemia is very consistent with the concept of excitation-transcription coupling (124), wherein Ca2+ influx and localized Ca2+ signaling may alter CSM phenotype. Wamhoff et al. selectively increased or decreased L-type VGCC gene expression and Ca2+ influx and found parallel changes in smooth muscle contractile gene and protein expression (122). Exercise training of diabetic dyslipidemic Yucatan pigs prevented the decrease in VGCC current (132), which is consistent with a less proliferative, more differentiated CSM phenotype (Fig. 3B; Table 2).

Cytosolic and localized Can were increased in response to the mitogen endothelin (ET; Fig. 3A) in diabetic dyslipidemia and were directly associated with increased coronary atherosclerosis (67, 123). The transnuclear SR was more fragmented, thus potentially providing more structural evidence for a breakdown in the NBB. The lipid-lowering agent atorvastatin prevented the increases in Can, defects in the transnuclear SR morphology, and coronary atherosclerosis. These data are consistent with a causal role of Can in atherosclerosis, especially considering that it is highly plausible because of the known role of Can in regulation of gene transcription in other cells (124). This is not definitive evidence, however, because there is no selective inhibitor of Can transients. No studies have been performed to determined whether aerobic exercise training will prevent the increases in CSM Can or transnuclear SR distribution in diabetic dyslipidemia (Fig. 3B, red font “Diabetes ↑Can”, broken red lines; Table 2). However, the attenuation of the endothelin-induced increase in CSM Can by exercise training of lean healthy pigs (121) and global effects on all other Ca2+ transporters suggest that exercise could attenuate diabetes dyslipidemia-induced increases in CSM Can.

Finally, to integrate these findings with human studies, recall that almost two-thirds of the exercise training-induced cardioprotection in humans is not explained by changes in traditional risk factors (81). In the studies on diabetic dyslipidemic swine reviewed here no component of the “diabetic milieu” (body weight, glucose, lipids, etc.) was changed by exercise training (Table 1). While all conceivable hormones and metabolic factors were not measured, these carefully controlled studies in swine are highly consistent with the conclusion that exercise effects are largely due to direct actions on the vasculature.

Exercise training effects on CSM Ca2+ regulation in metabolic syndrome.

Similar to the above discussion of diabetic dyslipidemia, I show the spatial relationships in Fig. 3A and list the changes in MetS Ossabaw swine in Table 2, top (Metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes) because there are several Ca regulatory processes, proteins, and membrane domains that influence Ca signaling and the MetS milieu is critical in these studies. Although Yucatan do not meet criteria to be defined as having MetS, data are included in Table 2 because Yucatans have the major component of dyslipidemia. MetS Ossabaw swine provide strong evidence for increased functional and molecular expression of TRPC channels in CSM (29). TRPC channels are thought to be one molecular form of “store-operated channels” (SOC) activated by signals from depletion of Ca2+ from the SR Ca2+ store (Fig. 3A, dashed arrow; 7, 57, 69). The SR Ca2+ depletion is sensed by the stromal interaction molecule type 1 (Fig. 3, STIM1) to couple to TRPC channel opening. Increased Cac and Can responses to mitogens are key findings in alloxan diabetic and dyslipidemic Yucatan swine (67, 123), but unlike the Ossabaw MetS, we have never in ∼20 years of studying CSM from healthy or diabetic dyslipidemic Yucatan pigs found activation of TRPC/SOC Ca2+ influx in CSM of Yucatan pigs (e.g., Fig. 2A in Ref. 132). In our hands SOC-mediated Ca2+ influx is absent from Yucatan and the presence SOC is unique to Ossabaw CSM. Importantly, SOC-mediated Ca2+ entry contributes to vascular smooth muscle phenotypic switching and vascular disease (57, 59, 111). Although there are six isoforms of TRPC (TRPC1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7), TRPC1 mediated neointimal hyperplasia in human arteries in vitro (57). Indeed, the pivotal study of Kumar et al. (57) showed definitively a causal role of TRPC1, as inhibition of TRPC1 in organ culture with a highly specific blocking antibody that binds an extracellular epitope elicited about a 50% decrease in neointima formation. However, many details remain to be determined regarding the sarcolemmal receptors for TRPC activation in MetS-induced CAD and restenosis and these purely in vitro studies did not address TRPC channel regulation in culture media simulating the MetS milieu or exercise milieu.

Edwards et al. (29) found that SR Ca2+ store depletion activated Ca2+ influx in CSM, which was increased in MetS vs. lean pigs and attenuated by 7 wk of exercise training (Fig. 3, Table 2). These data were from unidirectional divalent cation (Ca2+, Mn2+) influx measures using the sensitive Mn2+ quench method. The voltage dependence of SOC current in patch-clamp studies showed the characteristic nonselectivity of TRPC1, which was supported by increased TRPC1 mRNA and protein, but not Orai1 protein. The accessory protein stromal interaction molecule type 1 (STIM1) also showed parallel increases with TRPC1 in MetS and attenuation after exercise training (Fig. 3). A provocative possibility is whether intermediate conductance Ca-activated K channel (IKCa1) expression is increased in MetS pigs, similar to that noted in cultured, proliferating CSM, in CSM from atherosclerotic pigs (112), and after coronary restenosis (113). The result should be hyperpolarization and increased Ca2+ influx through TRPC1 due to the increased driving force for Ca2+ (Fig. 3, + and dashed line). The decreased large conductance KCa in CSM of MetS pigs (8) would suggest highly specific expression of these KCa isoforms. The fine tuning of KCa dysregulation in hypertension and metabolic disease is entirely possible and provides impetus for more work in the area (97), especially with regard to effects of exercise training. These data further argue for the specificity of the diabetic milieu, as the decrease in KCa in MetS (8) is opposite of the upregulation noted in conduit CSM in diabetic dyslipidemia (77, 78) (Table 2). The degree of hyperglycemia, obesity, plasma cholesterol, insulin, aldosterone, and other hormones differed between the studies (8, 77, 78); thus, differential signals for vascular adaptations could have a major influence. The SERCA pump in MetS is apparently more responsive to its milieu, as SERCA is upregulated in CSM of lean Ossabaw pigs compared with lean Yucatans and SERCA decreases in MetS (84). This suggests a propensity toward SERCA dysfunction in Ossabaw swine predisposed to MetS. Sarcolemmal Ca2+ extrusion is also impaired in CSM of lean Ossabaw vs. Yucatan swine and there have been no exercise training studies to assess the impact on SERCA or sarcolemmal Ca2+ transporters (84). Finally, the available data on MetS again support the finding that exercise training-induced cardioprotection is not due exclusively to changes in traditional risk factors (81). Only LDL/HDL ratio was improved by exercise training of MetS swine, while seven other metabolic parameters were unchanged (Table 1), despite improved CSM Ca2+ regulation by TRPC1 and attenuated CAD after exercise training (29).

Although much of the evidence provided does not definitely show whether altered Ca2+ signaling in MetS and diabetes causes native CAD and restenosis, several lines of evidence are consistent with this interpretation based on longstanding logic from environmental medicine (43). First, the varied degree of CAD within a single artery and between arteries allows one to determine whether underlying Ca2+ regulatory mechanisms (mRNA, protein, and activity) are proportional to the degree of CAD, i.e., assess causation by the strength of the association (123). Second, studying CAD at varying durations of MetS, diabetes, and after stenting allows one to determine whether Ca2+ signaling mechanisms occur before CAD, i.e., assesses causation by the temporality of the relationship (85). For example, TRPC channels increased in MetS before CAD (29, 85). Assessment of causation by specificity (selective antagonism) is very difficult in coronary arteries in vivo because it would require chronic use of systemic pharmacological inhibitors or transgenic technology (e.g., 58). Selective antagonism with pharmacological inhibitors and molecular tools (siRNA, antisense oligonucleotides) to dissect mechanistic pathways may require use of the in vitro organ culture approach (e.g., 121) and more refined catheter delivery methods for local targeting in vivo (54).

The collective interpretation of data from CSM Ca2+ signaling in diabetic dyslipidemic Yucatan pigs and MetS Ossabaw pigs is that Ca2+ influx via VGCC promotes CSM differentiation, while Ca2+ release and Ca2+ influx via SOC (TRPC1) promote CSM dedifferentiation and proliferation. Exercise training prevents/reverses these the Ca2+ signaling abnormalities.

CONCLUSIONS, PERSPECTIVES, AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Some of the most therapeutically beneficial drugs have multiple actions. For example, statin drugs have pleiotropic effects beyond their lipid-lowering ability, which may account for their convincing success in prevention (25), regression (88), and stabilization of CAD (76, 127). Exercise may very well rival statins, because it is difficult to fathom that a single drug or therapy could elicit such widespread adaptations in Ca2+ signaling as exercise training. Characterization of the multiple Ca2+ signaling mechanisms, even if “only” associated with exercise, provide a glimpse of many Ca2+ regulatory pathways that may be targeted by pharmacological therapy. While characterization of Ca2+ signaling is a major advance, there are key priorities for future directions: 1) target key molecules in the Ca2+ signaling pathways for over- or underexpression to determine with more confidence the causal role, instead of only the association, of these molecules in mechanisms of exercise protection against CAD; 2) combine mechanistic studies with hard clinical outcomes, e.g., reduction of spontaneous myocardial infarction and mortality. Even precise intravascular imaging methods and histology measures of atherosclerosis are considered surrogate endpoints. Studies of hard clinical endpoints would facilitate translation of cellular and molecular mechanisms of Ca2+ regulation to true cardioprotection.

GRANTS

Preparation of this review was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-062552 and UL1-RR-025761 (Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

First and foremost, I thank many colleagues who contributed to this work over the past nearly 20 years since our first publication on the effects of exercise training on coronary smooth muscle Ca2+ regulation. I thank Dr. M. Richardson for his work on Fig. 1. Although every attempt was made to cite many studies on swine metabolic derangements and atherosclerosis, the space and reference limit in this brief review format precluded citation of all the excellent work in the field.

REFERENCES

- 1. ACCORD Study Group; Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Genuth S, Ismail-Beigi F, Buse JB, Goff DC, Jr, Probstfield JL, Cushman WC, Ginsberg HN, Bigger JT, Grimm RH, Jr, Byington RP, Rosenberg YD, Friedewald WT. Long-term effects of intensive glucose lowering on cardiovascular outcomes. N Engl J Med 364: 818–828, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adachi T, Matsui R, Xu S, Kirber M, Lazar HL, Sharov VS, Schoneich C, Cohen RA. Antioxidant improves smooth muscle sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase function and lowers tyrosine nitration in hypercholesterolemia and improves nitric oxide-induced relaxation. Circ Res 90: 1114–1121, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Belardinelli R, Paolini I, Cianci G, Piva R, Georgiou D, Purcaro A. Exercise training intervention after coronary angioplasty: the ETICA trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 37: 1891–1900, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bell LN, Lee L, Saxena R, Bemis KG, Wang M, Theodorakis JL, Vuppalanchi R, Alloosh M, Sturek M, Chalasani N. Serum proteomic analysis of diet-induced steatohepatitis and metabolic syndrome in the Ossabaw miniature swine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 298: G746–G754, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bellinger DA, Merricks EP, Nichols TC. Swine models of type 2 diabetes mellitus: insulin resistance, glucose tolerance, and cardiovascular complications. ILAR J 47: 243–258, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bender SB, Tune JD, Borbouse L, Long X, Sturek M, Laughlin MH. Altered mechanism of adenosine-induced coronary arteriolar dilation in early-stage metabolic syndrome. Exp Biol Med 234: 683–692, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bergdahl A, Gomez MF, Dreja K, Xu SZ, Adner M, Beech DJ, Broman J, Hellstrand P, Sward K. Cholesterol depletion impairs vascular reactivity to endothelin-1 by reducing store-operated Ca2+ entry dependent on TRPC1. Circ Res 93: 839–847, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Borbouse L, Dick GM, Asano S, Bender SB, Dincer UD, Payne GA, Neeb ZP, Bratz IN, Sturek M, Tune JD. Impaired function of coronary BKCa channels in metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H1629–H1637, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Borbouse L, Dick GM, Payne GA, Berwick ZC, Neeb ZP, Alloosh M, Bratz IN, Sturek M, Tune JD. Metabolic syndrome reduces the contribution of K+ channels to ischemic coronary vasodilation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H1182–H1189, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Borbouse L, Dick GM, Payne GA, Payne BD, Svendsen MC, Neeb ZP, Alloosh M, Bratz IN, Sturek M, Tune JD. Contribution of BKCa channels to local metabolic coronary vasodilation: effects of metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H966–H973, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boullion RD, Mokelke EA, Wamhoff BR, Otis CR, Wenzel J, Dixon JL, Sturek M. Porcine model of diabetic dyslipidemia: Insulin and feed algorithms for mimicking diabetes in humans. Comp Med 53: 42–52, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bowles DK, Heaps CL, Turk JR, Maddali KK, Price EM. Hypercholesterolemia inhibits L-type calcium current in coronary macro-, not microcirculation. J Appl Physiol 96: 2240–2248, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bowles DK, Wamhoff BR. Coronary smooth muscle adaptation to exercise: does it play a role in cardioprotection? Acta Physiol Scand 178: 117–121, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bratz IN, Dick GM, Tune JD, Edwards JM, Neeb ZP, Dincer UD, Sturek M. Impaired capsaicin-induced relaxation of coronary arteries in a porcine model of the metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H2489–H2496, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Burke AP, Kolodgie FD, Zieske A, Fowler DR, Weber DK, Varghese PJ, Farb A, Virmani R. Morphologic findings of coronary atherosclerotic plaques in diabetics: a postmortem study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24: 1266–1271, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Casscells W, Naghavi M, Willerson JT. Vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque: a multifocal disease. Circulation 107: 2072–2075, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Christoffersen BO, Grand N, Golozoubova V, Svendsen O, Raun K. Gender-associated differences in metabolic syndrome-related parameters in Gottingen minipigs. Comp Med 57: 493–504, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Clark BA, Alloosh M, Wenzel JW, Sturek M, Kostrominova TY. Effect of diet-induced obesity and metabolic syndrome on skeletal muscles of Ossabaw miniature swine. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 300: E848–E857, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Fernhall B, Regensteiner JG, Blissmer BJ, Rubin RR, Chasan-Taber L, Albright AL, Braun B. Exercise and type 2 diabetes: the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Diabetes Association: joint position statement executive summary. Diabetes Care 33: 2692–2696, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Committee to Develop a Resource Book for Animal Exercise Protocols. Resource Book for the Design of Animal Exercise Protocols. Bethesda, MD: Am. Physiol. Soc., 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cooper SA, Whaley-Connell A, Habibi J, Wei Y, Lastra G, Manrique C, Stas S, Sowers JR. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and oxidative stress in cardiovascular insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H2009–H2023, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Diamond J. The double puzzle of diabetes. Nature 423: 599–602, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dick GM, Sturek M. Effects of a physiological insulin concentration on the endothelin-sensitive Ca2+ store in porcine coronary artery smooth muscle. Diabetes 45: 876–880, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dixon JL, Shen S, Vuchetich JP, Wysocka E, Sun G, Sturek M. Increased atherosclerosis in diabetic dyslipidemic swine: protection by atorvastatin involves decreased VLDL triglycerides but minimal effects on the lipoprotein profile. J Lipid Res 43: 1618–1629, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dixon JL, Stoops JD, Parker JL, Laughlin MH, Weisman GA, Sturek M. Dyslipidemia and vascular dysfunction in diabetic pigs fed an atherogenic diet. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 19: 2981–2992, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dyson M, Alloosh M, Vuchetich JP, Mokelke EA, Sturek M. Components of metabolic syndrome and coronary artery disease in female Ossabaw swine fed excess atherogenic diet. Comp Med 56: 35–45, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Eckel RH, Kahn R, Robertson RM, Rizza RA. Preventing cardiovascular disease and diabetes: a call to action from the American Diabetes Association and the American Heart Association. Circulation 113: 2943–2946, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Edwards JM, Alloosh M, Long X, Dick GM, Lloyd PG, Mokelke EA, Sturek M. Adenosine A1 receptors in neointimal hyperplasia and in-stent stenosis in Ossabaw miniature swine. Cor Art Dis 19: 27–31, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Edwards JM, Neeb ZP, Alloosh MA, Long X, Bratz IN, Peller CR, Byrd JP, Kumar S, Obukhov AG, Sturek M. Exercise training decreases store-operated Ca2+ entry associated with metabolic syndrome and coronary atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res 85: 631–640, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Erbs S, Linke A, Hambrecht R. Effects of exercise training on mortality in patients with coronary heart disease. Cor Art Dis 17: 219–225, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fleenor BS, Bowles DK. Exercise training decreases the size and alters the composition of the neointima in a porcine model of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA). J Appl Physiol 107: 937–945, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Flum DR, Devlin A, Wright AS, Figueredo E, Alyea E, Hanley PW, Lucas MK, Cummings DE. Development of a porcine Roux-en-Y gastric bypass survival model for the study of post-surgical physiology. Obesity Surg 17: 1332–1339, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ford ES. Risks for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes associated with the metabolic syndrome: a summary of the evidence. Diabetes Care 28: 1769–1778, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ford ES, Giles WH, Mokdad AH. Increasing prevalence of the metabolic syndrome amoung U.S. adults. Diabetes Care 27: 2444–2449, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fullenkamp AM, Bell LN, Robbins RD, Lee L, Saxena R, Alloosh M, Klaunig JE, Mirmira RG, Sturek M, Chalasani N. Effect of different obesogenic diets on pancreatic histology in Ossabaw miniature swine. Pancreas 40: 438–443, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gerrity RG, Natarajan R, Nadler JL, Kimsey T. Diabetes-induced accelerated atherosclerosis in swine. Diabetes 50: 1654–1665, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Goldberg IJ, Dansky HM. Diabetic vascular disease: an experimental objective. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 26: 1693–1701, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Grundy SM, Brewer HB, Cleeman JI, Smith SC, Jr, Lenfant C. Definition of the metabolic syndrome. Circulation 109: 433–438, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hainsworth DP, Katz ML, Sanders DA, Sanders DN, Wright EJ, Sturek M. Retinal capillary basement membrane thickening in a porcine model of diabetes mellitus. Comp Med 52: 523–529, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hall JE. The kidney, hypertension, obesity. Hypertension 41: 625–633, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hambrecht R, Walther C, Mobius-Winkler S, Gielen S, Linke A, Conradi K, Erbs S, Kluge R, Kendziorra K, Sabri O, Sick P, Schuler G. Percutaneous coronary angioplasty compared with exercise training in patients with stable coronary artery disease: a randomized trial. Circulation 109: 1371–1378, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Haskell WL, Sims C, Myll J, Bortz WM, St Goar FG, Alderman EL. Coronary artery size and dilating capacity in ultradistance runners. Circulation 87: 1076–1082, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hill AB. The environment and disease: association or causation? Proc R Soc Med 58: 295–300, 1965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hill BJF, Dixon JL, Sturek M. Effect of atorvastatin on intracellular calcium uptake in coronary smooth muscle cells from diabetic pigs fed an atherogenic diet. Atherosclerosis 159: 117–124, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hill BJF, Price EM, Dixon JL, Sturek M. Increased calcium buffering in coronary smooth muscle cells from diabetic dyslipidemic pigs. Atherosclerosis 167: 15–23, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hill BJF, Wamhoff BR, Sturek M. Functional nucleotide receptor expression and sarcoplasmic reticulum morphology in dedifferentiated porcine coronary smooth muscle cells. J Vasc Res 38: 432–443, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Holvoet P, Davey PC, De Keyzer D, Doukoure M, Deridder E, Bochaton-Piallat ML, Gabbiani G, Beaufort E, Bishay K, Andrieux N, Benhabiles N, Marguerie G. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein correlates positively with Toll-like receptor 2 and interferon regulatory factor-1 and inversely with superoxide dismutase-1 expression: studies in hypercholesterolemic swine and THP-1 cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 26: 1558–1565, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Horton JD, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. PCSK9: a convertase that coordinates LDL catabolism. J Lipid Res 50, Suppl: S172–S177, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hsueh W, Abel ED, Breslow JL, Maeda N, Davis RC, Fisher EA, Dansky H, McClain DA, McIndoe R, Wassef MK, Rabadan-Diehl C, Goldberg IJ. Recipes for creating animal models of diabetic cardiovascular disease. Circ Res 100: 1415–1427, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jacobsson L. Comparison of experimental hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis in male and female mini-pigs of the Gottingen strain. Artery 16: 105–117, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jaffe IZ, Tintut Y, Newfell BG, Demer LL, Mendelsohn ME. Mineralocorticoid receptor activation promotes vascular cell calcification. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27: 799–805, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Johansen T, Hansen HS, Richelsen B, Malmlof R. The obese Gottingen minipig as a model of the metabolic syndrome: dietary effects on obesity, insulin sensitivity, and growth hormone profile. Comp Med 51: 150–155, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kahn R, Buse J, Ferrannini E, Stern M. The metabolic syndrome: time for a critical appraisal. Joint statement from the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetologia 48: 1684–1699, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Karanian JW, Peregoy JA, Chiesa OA, Murray TL, Ahn C, Pritchard WF. Efficiency of drug delivery to the coronary arteries in swine is dependent on the route of administration: assessment of luminal, intimal, and adventitial coronary artery and venous delivery methods. J Vasc Interv Radiol 21: 1555–1564, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kramsch DM, Aspen AJ, Abramowitz BM, Kreimendahl T, Wood WB., Jr Reduction of coronary atherosclerosis by moderate conditioning exercise in monkeys on an atherogenic diet. N Engl J Med 305: 1483–1489, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kreutz RP, Alloosh M, Mansour K, Neeb ZP, Kreutz Y, Flockhart DA, Sturek M. Morbid obesity and metabolic syndrome in Ossabaw miniature swine are associated with increased platelet reactivity. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 4: 99–105, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kumar B, Dreja K, Shah SS, Cheong A, Xu SZ, Sukumar P, Naylor J, Forte A, Cipollaro M, McHugh D, Kingston PA, Heagerty AM, Munsch CM, Bergdahl A, Hultgardh-Nilsson A, Gomez MF, Porter KE, Hellstrand P, Beech DJ. Upregulated TRPC1 channel in vascular injury in vivo and its role in human neointimal hyperplasia. Circ Res 98: 557–563, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lai L, Kolber-Simonds D, Park KW, Cheong HT, Greenstein JL, Im GS, Samuel M, Bonk A, Rieke A, Day BN, Murphy CN, Carter DB, Hawley RJ, Prather RS. Production of α-1,3-Galactosyltransferase knockout pigs by nuclear transfer cloning. Science 295: 1089–1092, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Landsberg JW, Yuan JX. Calcium and TRP channels in pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. News Physiol Sci 19: 44–50, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Langohr IM, HogenEsch H, Stevenson GW, Sturek M. Vascular-associated lymphoid tissue in swine (Sus scrofa). Comp Med 58: 168–173, 2008 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Larsen MO, Juhl CB, Porksen N, Gotfredsen CF, Carr RD, Ribel U, Wilken M, Rolin B. Beta-cell function and islet morphology in normal, obese, and obese beta-cell mass-reduced Gottingen minipigs. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 288: E412–E421, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Larsen MO, Rolin B. Use of the Gottingen minipig as a model of diabetes with special focus on type 1 diabetes research. ILAR J 45: 303–313, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Larsen MO, Rolin B, Raun K, Bjerre Knudsen L, Gotfredsen CF, Bock T. Evaluation of beta-cell mass and function in the Gottingen minipig. Diabetes Obesity Metab 9, Suppl 2: 170–179, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Larsen MO, Rolin B, Wilken M, Carr RD, Svendsen O. High-fat high-energy feeding impairs fasting glucose and increases fasting insulin levels in the Gottingen minipig: results from a pilot study. Ann NY Acad Sci 967: 414–423, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Larsen MO, Rolin B, Sturis J, Wilken M, Carr RD, Porksen N, Gotfredsen CF. Measurements of insulin responses as predictive markers of pancreatic beta-cell mass in normal and beta-cell-reduced lean and obese Gottingen minipigs in vivo. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 290: E670–E677, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Le T, Langohr IM, Locker MJ, Sturek M, Cheng JX. Label-free molecular imaging of atherosclerotic lesions using multimodal nonlinear optical microscopy. J Biomed Opt 12: 054007, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lee DL, Wamhoff BR, Katwa LC, Reddy HK, Voelker DJ, Dixon JL, Sturek M. Increased endothelin-induced Ca2+ signaling, tyrosine phosphorylation, and coronary artery disease in diabetic dyslipidemic swine are prevented by atorvastatin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 306: 132–140, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lee L, Alloosh M, Saxena R, Van Alstine W, Watkins BA, Klaunig JE, Sturek M, Chalasani N. Nutritional model of steatohepatitis and metabolic syndrome in the Ossabaw miniature swine. Hepatology 50: 56–67, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Li J, Sukumar P, Milligan CJ, Kumar B, Ma ZY, Munsch CM, Jiang LH, Porter KE, Beech DJ. Interactions, functions, and independence of plasma membrane STIM1 and TRPC1 in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 103: e97–e104, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Libby P, Plutzky J. Diabetic macrovascular disease: The glucose paradox? Circulation 106: 2760–2763, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Link RP, Pedersoli WM, Safanie AH. Effect of exercise on development of atherosclerosis in swine. Atherosclerosis 15: 107–122, 1972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Liu Y, Jones AW, Sturek M. Ca2+-dependent K+ current in arterial smooth muscle cells from aldosterone-salt hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 269: H1246–H1257, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Lloyd PG, Sheehy AF, Edwards JM, Mokelke EA, Sturek M. Leukemia inhibitory factor is upregulated in coronary arteries of Ossabaw miniature swine after stent placement. Cor Art Dis 19: 217–226, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Long X, Bratz IN, Alloosh M, Edwards JM, Sturek M. Short-term exercise training prevents micro- and macrovascular disease following coronary stenting. J Appl Physiol 108: 1766–1774, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Long X, Mokelke EA, Neeb ZP, Alloosh M, Edwards JM, Sturek M. Adenosine receptor regulation of coronary blood flow in Ossabaw miniature swine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 335: 781–787, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Mizobuchi M, Towler D, Slatopolsky E. Vascular calcification: the killer of patients with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrology 20: 1453–1464, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Mokelke EA, Dietz NJ, Eckman DM, Nelson MT, Sturek M. Diabetic dyslipidemia and exercise affect coronary tone and differential regulation of conduit and microvessel K+ current. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H1233–H1241, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Mokelke EA, Hu Q, Song M, Toro L, Reddy HK, Sturek M. Altered functional coupling of coronary K+ channels in diabetic dyslipidemic pigs is prevented by exercise. J Appl Physiol 95: 1179–1193, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Mokelke EA, Hu Q, Turk JR, Sturek M. Enhanced contractility in coronary arteries of diabetic pigs is prevented by exercise. Equine Comp Exercise Physiol 1: 71–80, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 80. Mokelke EA, Wang M, Sturek M. Exercise training enhances coronary smooth muscle cell sodium-calcium exchange activity in diabetic dyslipidemic Yucatan swine. Ann NY Acad Sci 976: 335–337, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Mora S, Cook N, Buring JE, Ridker PM, Lee IM. Physical activity and reduced risk of cardiovascular events: potential mediating mechanisms. Circulation 116: 2110–2118, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]