Abstract

Myocardial microvascular permeability and coronary sinus concentration of muscle metabolites have been shown to increase after myocardial ischemia due to epicardial coronary artery occlusion and reperfusion. However, their association with coronary microembolization is not well defined. This study tested the hypothesis that acute coronary microembolization increases microvascular permeability in the porcine heart. The left anterior descending perfusion territories of 34 anesthetized pigs (32 ± 3 kg) were embolized with equal volumes of microspheres of one of three diameters (10, 30, or 100 μm) and at three different doses for each size. Electron beam computed tomography (EBCT) was used to assess in vivo, microvascular extraction of a nonionic contrast agent (an index of microvascular permeability) before and after microembolization with microspheres at baseline and during adenosine infusion. A high-resolution three-dimensional microcomputed tomography (micro-CT) scanner was subsequently used to obtain ex vivo, the volume and corresponding surface area of the embolized myocardial islands within the perfusion territories of the microembolized coronary artery. EBCT-derived microvascular extraction of contrast agent increased within minutes after coronary microembolization (P < 0.001 vs. baseline and vs. control values). The increase in coronary microvascular permeability was highly correlated to the micro-CT-derived total surface area of the nonperfused myocardium (r = 0.83, P < 0.001). In conclusion, myocardial extravascular accumulation of contrast agent is markedly increased after coronary microembolization and its magnitude is in proportion to the surface area of the interface between the nonperfused and perfused territories.

Keywords: microspheres, EBCT, micro-CT, microvascular permeability

a balance between delivery of vital nutrients and removal of waste products from the myocardium is pivotal for maintaining the physiological contractile function of the myocytes and for the coordinated electrical conductance along the cells' membranes. However, it has been shown that myocardial microvascular permeability can change under various pathologic and metabolic circumstances such as diabetes mellitus (24, 41), hypercholesterolemia (32), hypertension (31), and acute myocardial ischemia followed by reperfusion (29). Embolization of microscopic plaque debris into the distal coronary bed during coronary interventions is a common and frequent event (9, 10, 35) that might be associated with microinfarctions and with adverse clinical outcome (7, 10).

We have previously demonstrated that experimental coronary microembolization leads to a decrease in regional myocardial contractility that is proportional to the surface area of the embolization-induced nonperfused islands (microperfusion defects) in the myocardium (23). However, the effect of this maneuver on microvascular integrity or the factors that determine the magnitude of the extravascular accumulation of contrast agent remained unknown.

The consequences of increased permeability to solutes can be observed only if there is, in fact, delivery to the microvasculature, i.e., in the presence of ongoing perfusion. Permeability affecting mediators originating from disintegrated tissue can more easily and likely diffuse from the interfacial region between perfused and nonperfused myocardium (i.e., short distance, proportional to the interface's surface area) into the perfused myocardium and corresponding microvasculature rather than from deep within the nonperfused myocardium (long diffusion distance). Consequently, the movement of water and solutes from the intravascular into the extravascular compartment should primarily occur at the interface between the nonperfused and perfused territories. Based on these observations, we hypothesize that 1) coronary microembolization leads to an increase of microvascular permeability of the endothelium in the microvessels within the perfusion territory embolized, and 2) the increase in extravascular water and solutes due to the increased permeability is directly related to the total surface area of the interface between the nonperfused and surrounding perfused myocardium.

To test these hypotheses, we used two complementary imaging modalities. Electron beam computed tomography (EBCT) was used to obtain in vivo indices of myocardial perfusion (F, flow; ml·g myocardium−1·min−1), microvascular permeability (30), and intramyocardial blood volume as the surrogate for vascular surface area (Bv, blood volume; ml/g myocardium). After completion of the EBCT-based studies, an X-ray microcomputed tomography scanner (micro-CT) was used to obtain directly, ex vivo, the volume and the total surface area of the individual nonperfused, ischemic, myocardial territories within the same region of myocardium that was previously scanned by the EBCT. Micro-CT provides a unique tool for quantification of 3D vascular structures and the number, volume, and surface area of the individual myocardial perfusion defects in a relatively large volume (>1 cm3) of embolized myocardium (22, 23). For testing our hypotheses in an in situ heart in an animal model, we used anesthetized pigs because their coronary circulation closely resembles human heart anatomy, blood flow distribution, and function (37). Different sizes and doses of microspheres were used to explore the relationship between the surface area and increase in microvascular permeability over a wide range of individual-sized perfusion defects and to mimic the clinically observed heterogeneous nature in sizes and quantity of embolizing particle debris during coronary interventions (2). The aim of this study was therefore to quantify changes in coronary microvascular permeability to the nonionic contrast agent iopamidol following coronary microembolization with polymer microspheres in the perfusion territory of porcine left anterior descending coronary artery.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Animal preparation.

The study protocol was approved by the Mayo Foundation Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Thirty-four domestic, crossbred (all female, mean weight: 32.0 ± 3 kg), 3 mo old pigs were initially anesthetized and instrumented as described previously (21, 27). Briefly, the left internal jugular vein and the left carotid artery were exposed via cut down. Sheaths were placed in the left carotid artery (8 French) and in the left jugular vein (7 French), respectively. Under fluoroscopic guidance, a left coronary guide catheter was placed in the left main coronary artery for coronary angiography and monitoring proximal coronary artery pressure. The tip of a 2.2-French, dual-lumen, infusion catheter was advanced via the 8 French catheter, and its tip placed in the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) between the second and third diagonal branches for selective intracoronary infusion of adenosine and microspheres.

EBCT studies.

To overcome the cardiogenic motion imaging artifacts, we used EBCT, a fast CT with a single-scan acquisition time of 50 ms, which could be repeated 17 times per second. This scanner has been proven to be an accurate (4), reproducible (25), and minimally invasive (27) tool for in vivo study of microcirculatory functional parameters, such as myocardial perfusion and permeability indices (27, 29, 30, 32). The technical properties of the EBCT scanner (model C-150; Imatron, South San Francisco, CA) have been described in detail elsewhere (27, 32, 33). Animals were positioned supine in the EBCT gantry so that the heart was centered in the imaging field and fixed in the position for the subsequent studies. The field-of-view in the reconstructed tomographic images was 21 cm, pixel size of 0.58 mm, voxel size of 2.38 mm3, 7-mm slice thickness, acquisition time of 50 ms. Short axis images were obtained at four levels along the left ventricular (LV) axis (from apex to base), triggered at 80% of the RR interval.

Initially, a localization scan without any contrast agent was performed to determine the four LV levels. For the next scan, 4 ml of the low-osmolar, nonionic, radiopaque contrast agent (iopamidol, Isovue-370; Bracco Diagnostics, Princeton, NJ) was injected over 2 s selectively into the LAD catheter to highlight the LAD perfusion territory (Fig. 1, left), which then served as the region of interest for the analysis of the four subsequent flow scans obtained during an intravenous bolus injection of 0.33 ml/kg of iopamidol.

Fig. 1.

Left and middle: electron beam computed tomography (EBCT) images of the porcine left ventricle showing selective opacification of left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) perfusion territory (A), which was manually outlined and used as the region of interest for the subsequent flow scans (B). LCX, left circumflex coronary artery; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle. Right: representative time-density curve obtained from EBCT images of the LAD perfusion territory. HU, Hounsfield Unit. Our algorithm allows differentiation of the time density curve (Dens) into an intravascular curve (Art), which provides information about the transit time through the myocardial vasculature, and an extravascular curve (Extr), which represents the diffusion of contrast into the myocardial interstitium. From these data, myocardial perfusion (F, flow), intramyocardial blood volume (Bv), and an index of myocardial microvascular permeability were calculated.

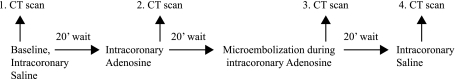

The four consecutive flow scan sequences were performed with a 20-min recovery period in between scans to allow washout of the extravascular contrast agent (8, 16) as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Four consecutive flow-scan sequences were performed with a 20-min recovery period in between computed tomography (CT) scans to allow washout of the extravascular contrast agent.

These included a baseline study (intracoronary infusion of normal saline at 1 ml/min) followed by scanning sequences after 5 min of intracoronary infusion of adenosine (50 μg·kg−1·min−1; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), adenosine plus one selected diameter and dose of polymer microspheres (Duke Scientific, Palo Alto, CA), and at recovery (intracoronary infusion of saline at 1 ml/min). To assess the permeability response to varying magnitude of microembolization, we used microspheres of calibrated sizes and at one of three different doses (see Table 1) as previously shown (22, 27). The doses of microspheres were one-eighth, one-fourth, or one-half of the acutely lethal dose for the selected microsphere diameter (26). Additionally, in 10 randomly chosen animals (1 animal for each size and dose of microspheres + 1 control), the EBCT cine mode was used, as described previously (31) (17 scans/s throughout several cardiac cycles), before and 20 min after embolization, to assess the diastolic thickness of the anterior wall and the total volume of the LAD perfusion territory as an index of myocardial edema following the coronary microembolization (1, 14, 28, 36). To distinguish the endocardial border from the contrast-filled LV cavity, the scans were obtained during continuous infusion of iopamidol. This contrast agent has a molecular weight of 777.09 kDa, the solute has an iodine concentration of 370 mg/ml, osmolality of 780 osmol/kg, viscosity of 9.1 mPa/s, and pH of 6.5 to 7.5. The endocardial and epicardial borders were then manually traced at end diastole, and LV muscle mass was calculated as the product of myocardial muscle area, myocardial specific density (1.05 g/ml), and slice thickness.

Table 1.

Heart rate and mean arterial blood pressure (invasively measured) in pigs at baseline and after microembolization with microspheres at three different sizes and doses

| Heart Rate, beats/min |

Mean Arterial Blood Pressure, mm/Hg |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size and No. of μsph | Baseline | Baseline | Post-ME | |

| 10 μm, 1.25 × 106 | 82 ± 5 | 91 ± 5* | 97 ± 17 | 97 ± 11 |

| 10 μm, 2.5 × 106 | 85 ± 18 | 100 ± 13* | 78 ± 7 | 76 ± 4 |

| 10 μm, 5 × 106 | 74 ± 17 | 85 ± 17* | 82 ± 22 | 76 ± 21 |

| 30 μm, 3.75 × 104 | 81 ± 12 | 95 ± 16* | 92 ± 24 | 87 ± 16 |

| 30 μm, 7.5 × 104 | 82 ± 7 | 95 ± 6* | 96 ± 14 | 95 ± 15 |

| 30 μm, 1.5 × 105 | 88 ± 16 | 109 ± 23* | 94 ± 17 | 89 ± 19 |

| 100 μm, 1.25 × 103 | 82 ± 15 | 99 ± 18* | 88 ± 15 | 86 ± 21 |

| 100 μm, 2.5 × 103 | 73 ± 14 | 90 ± 15* | 99 ± 9 | 81 ± 14* |

| 100 μm, 5 × 103 | 78 ± 9 | 101 ± 9* | 97 ± 16 | 75 ± 18* |

| Control, no μsph | 93 ± 7 | 96 ± 5 | 97 ± 3 | 96 ± 8 |

Data are presented as means ± 1 SD. Post-ME, after microembolization; μsph, microspheres.

P < 0.05 vs. baseline.

To ensure that the measurements of the wall thickness were performed in the same location within the myocardium before and after embolization, markers such as the diagonal branches of the LAD were used as fiducial markers as described previously (22, 23). Hemodynamic parameters, such as heart rate and arterial blood pressure, ECG, and body temperature, were continuously monitored.

Indicator dilution curves obtained following each flow sequence in the myocardial and LV chamber regions of interest within the CT images of the heart (Fig. 1) were analyzed, as previously described (6, 30, 32) to calculate myocardial perfusion (F, flow; ml·g myocardium−1·min−1), intramyocardial mean transit time(s) (MTT), and intramyocardial intravascular blood volume (Bv; ml/g myocardium): Myocardial perfusion was then computed as: {F = 60 × (Bv/MTT)/[1.05 × (1 − Bv)]}. The factor (1 − Bv) served to convert the flow to milliliters per gram of myocardial muscle; 1.05 g/cc is the specific gravity of the myocardium.

Microvascular permeability was calculated as [60 × 1.05 × (slope of extravascular curve × MTT)/(area under the input curve/Bv)], where slope is the maximal slope of the ascending arm of the extravascular curve. Subsequently, the EBCT-derived permeability indices in each pig heart were normalized with the corresponding micro-CT-derived total volume of nonperfused myocardium [microvascular permeabilitynet = microvascular permeability/(1 − nonperfused myocardial volume)], since that fraction of myocardium that is not perfused cannot contribute to an exchange between its surface area and the surrounding myocardium.

In 10 randomly chosen animals, one animal representative for each size and dose of microspheres and in one nonembolized, control animal, the permeability indices at baseline and after LAD microembolization were also calculated for the left circumflex coronary artery (LCX) perfusion territory as a within-animal control region.

Micro-CT studies.

Following the EBCT scans, the hearts were removed and the coronary arteries cannulated. The coronary circulation was then flushed with heparinized saline to wash out the blood from the vasculature and was then infused with a radiopaque silicon polymer (Microfil; Flow Tech, Carver, MA).

The properties of the micro-CT scanner and the preparation of specimens for scanning have previously been described in detail (3, 13, 18, 20). Transmural myocardial samples of ∼1 cm3 were matched using internal landmarks to the embolized and previously EBCT-scanned regions and were then cut out and scanned with the micro-CT scanner, resulting in three-dimensional images (20 μm, on-a-side cubic voxel). Image analysis for obtaining the surface area of the embolized myocardial volume was performed as previously described (22, 23). Briefly, the outline of each nonopacified intramyocardial island was traced, and its surface area and volume calculated. The total nonperfused volume and surface area of the nonperfused islands was then derived per unit volume of myocardium imaged. Images of EBCT and micro-CT were analyzed using the Analyze software package (version 4.5; Biomedical Imaging Resource, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN). For analyses of the EBCT and micro-CT images, the investigators were blinded regarding the embolization or control status, as well as the sizes and doses of the injected microspheres.

Statistics.

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD, unless indicated otherwise. A two-factor ANOVA with replication was applied for differences within the group at different scan conditions and, if significant F values were obtained, Tukey honestly significant difference test was used for the post hoc analysis to identify both within-group and between-group differences. To express the relationship between the nonperfused myocardial volume and the total surface area of nonperfused myocardium (independent factors) and the increase in microvascular permeability (dependent factor), the Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated, and the linear regression analysis was used. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

In 30 animals (3 animals per each size and dose of microspheres + 3 control animals) the EBCT and micro-CT studies could be performed successfully. Four animals were lost due to refractory ventricular fibrillation after the microspheres injection.

Hemodynamic parameters.

Hemodynamic parameters at baseline and after embolization with the different sizes and doses of microspheres are presented in Table 1. Heart rate increased in all animals significantly after embolization with microspheres, regardless of the size or dose (P < 0.01 vs. baseline) but remained unaltered in the control group. Mean aortic blood pressure only changed significantly in animals embolized with microspheres (μsph) of 100-μm diameter at the one-quarter and one-half fatal doses (see Table 1).

EBCT studies.

Myocardial blood flow and blood volume at baseline and after coronary microembolization in relation to different sizes and doses of microspheres at different scan conditions are illustrated in Table 2. In all animals, flow and blood volume were comparable at baseline (P > 0.05) and increased significantly after intracoronary infusion of adenosine (P < 0.01). Embolization decreased blood flow and blood volume proportional to the sizes and dose of the injected microspheres (Table 2).

Table 2.

Intramyocardial blood volume (Bv; ml/g myocardium) and regional myocardial perfusion (F = flow, ml·g myocardium−1·min−1) in the porcine left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) perfusion territory at different scan conditions

| Scan Condition |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter, No. of μsph | Parameter | BL | IC AD | IC AD + μsph | 20 s Post-ME |

| 10 μm, 1.25 × 106 | F | 0.97 ± 0.29 | 2.28 ± 0.40* | 2.11 ± 0.37 | 1.11 ± 0.26* |

| Bv | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.25 ± 0.05* | 0.22 ± 0.03 | 0.13 ± 0.02*† | |

| 10 μm, 2.5 × 106 | F | 1.02 ± 0.24 | 2.09 ± 0.45* | 1.66 ± 0.42* | 1.13 ± 0.36* |

| Bv | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.23 ± 0.04* | 0.20 ± 0.04* | 0.12 ± 0.03* | |

| 10 μm, 5 × 106 | F | 0.95 ± 0.28 | 2.17 ± 0.45* | 1.40 ± 0.26* | 1.10 ± 0.38* |

| Bv | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.24 ± 0.04* | 0.15 ± 0.03* | 0.12 ± 0.02* | |

| 30 μm, 3.75 × 104 | F | 1.00 ± 0.27 | 2.33 ± 0.37* | 1.62 ± 0.31* | 1.12 ± 0.14* |

| Bv | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.22 ± 0.02* | 0.18 ± 0.03* | 0.14 ± 0.02*† | |

| 30 μm, 7.5 × 104 | F | 0.95 ± 0.24 | 2.18 ± 0.39* | 1.41 ± 0.49* | 1.20 ± 0.29* |

| Bv | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.23 ± 0.05* | 0.16 ± 0.03* | 0.13 ± 0.02*† | |

| 30 μm, 1.5 × 105 | F | 0.97 ± 0.25 | 2.11 ± 0.56* | 1.32 ± 0.45* | 1.13 ± 0.35* |

| Bv | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.23 ± 0.05* | 0.14 ± 0.03* | 0.13 ± 0.03† | |

| 100 μm, 1.25 × 103 | F | 1.09 ± 0.35 | 2.29 ± 0.41* | 1.57 ± 0.56* | 1.11 ± 0.22* |

| Bv | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 0.23 ± 0.05* | 0.17 ± 0.04* | 0.13 ± 0.03*† | |

| 100 μm, 2.5 × 103 | F | 1.05 ± 0.31 | 2.38 ± 0.37* | 1.34 ± 0.43* | 1.12 ± 0.28* |

| Bv | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.25 ± 0.06* | 0.14 ± 0.05* | 0.13 ± 0.03 | |

| 100 μm, 5 × 103 | F | 0.98 ± 0.30 | 2.24 ± 0.42* | 1.03 ± 0.30* | 1.06 ± 0.04* |

| Bv | 0.12 ± 0.04 | 0.23 ± 0.04* | 0.12 ± 0.04* | 0.11 ± 0.03 | |

| Control, no μsph | F | 1.09 ± 0.23 | 2.22 ± 0.21* | 2.10 ± 0.27 | 1.16 ± 0.26* |

| Bv | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.22 ± 0.02* | 0.22 ± 0.04 | 0.12 ± 0.03* | |

Values are presented as means ± 1 SD. BL, baseline; IC AD, intracoronary adenosine; μsph, microspheres.

P < 0.05 vs. previous scan;

P < 0.05 for Post-ME vs. BL scan.

The index of permeability at baseline was similar among all animals (P > 0.05, Table 3). It remained unchanged during vasodilation with adenosine infusion but increased significantly (P < 0.01) after embolization in the LAD perfusion territory. In contrast to the LAD perfusion territory, permeability remained unchanged in the nonembolized LCX perfusion territory (P > 0.05). The highest increase in permeability in percentage compared with baseline value was observed after embolization with microspheres of 10-μm diameter, followed by 30 μm and 100 μm (Fig. 3), indicating an inverse relationship between the diameters of embolized vessels and the resulting increase in permeability.

Table 3.

Coronary microvascular permeability index (arbitrary units) in animals embolized with microspheres of 10-, 30-, or 100-μm diameter, each size at 3 different doses

| Scan Condition |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter of μsph | No. of Injected μsph | Baseline | Adenosine | Adenosine + Microspheres | 20 s Post-ME |

| 10 μm | 1.25 × 106 | 0.39 ± 0.1 | 0.40 ± 0.08 | 0.57 ± 0.11* | 0.54 ± 0.16*† |

| 10 μm | 2.5 × 106 | 0.37 ± 0.06 | 0.40 ± 0.07 | 0.53 ± 0.15* | 0.46 ± 0.06*† |

| 10 μm | 5 × 106 | 0.32 ± 0.10 | 0.30 ± 0.08 | 0.58 ± 0.19* | 0.51 ± 0.12*† |

| 30 μm | 3.75 × 104 | 0.38 ± 0.09 | 0.39 ± 0.09 | 0.52 ± 0.08* | 0.46 ± 0.09*† |

| 30 μm | 7.5 × 104 | 0.36 ± 0.16 | 0.35 ± 0.06 | 0.48 ± 0.11* | 0.45 ± 0.07*† |

| 30 μm | 1.5 × 105 | 0.40 ± 0.09 | 0.36 ± 0.09 | 0.54 ± 0.08* | 0.50 ± 0.10*† |

| 100 μm | 1.25 × 103 | 0.46 ± 0.11 | 0.45 ± 0.13 | 0.53 ± 0.09* | 0.51 ± 0.10* |

| 100 μm | 2.5 × 103 | 0.36 ± 0.11 | 0.38 ± 0.08 | 0.52 ± 0.10* | 0.42 ± 0.06* |

| 100 μm | 5 × 103 | 0.31 ± 0.08 | 0.31 ± 0.09 | 0.45 ± 0.11* | 0.37 ± 0.08* |

| Control | 0.40 ± 0.08 | 0.37 ± 0.11 | 0.37 ± 0.07 | 0.37 ± 0.05 | |

| LCX perfusion territory | 0.33 ± 0.07 | 0.35 ± 0.11 | 0.34 ± 0.09 | 0.36 ± 0.12 | |

Values of permeability indices are presented as means ± 1 SD of electron beam computed tomography-derived coronary microvascular permeability indices at different scan conditions in porcine LAD and left circumflex coronary artery (LCX) perfusion territories. The different scan conditions are described in the text.

P < 0.05 vs. previous scan;

P < 0.05 vs. baseline scan.

Fig. 3.

Change in permeability index (arbitrary units) in % compared with baseline values in control and embolized animals after intracoronary injection of 10, 30, or 100 μm microspheres (μsph) at equivalent dose (1/2 of the fatal dose). IC, intracoronary; Post-CME, after coronary microembolization. *P < 0.01 vs. baseline and IC adenosine values; †P < 0.01 vs. 30 μm and 100 μm microspheres.

Muscle volume of LAD perfusion territory and diastolic anterior wall thickness.

Except for the control animal, the average volume of LAD perfusion territory, as an indicator of myocardial edema, increased significantly (P < 0.01) in all representative animals after embolization (Fig. 4A). Diastolic thickness of the anterior wall was 5.87 ± 0.19 mm and increased at 20 min after embolization to 6.56 ± 0.35 mm (P < 0.01), while the systolic thickness did not change (8.61 ± 0.30 mm vs. 8.55 ± 0.33 mm, P = 0.63). The increase in diastolic thickness of the anterior wall was highly correlated to the total surface area of the nonperfused myocardium (Fig. 4B, r = 0.82, P < 0.01).

Fig. 4.

A: LV muscle volume of the LAD perfusion territory determined by EBCT at baseline and at 20 min postembolization. Numbers in the legend (10, 30, or 100 μm) indicate the diameter, and a, b, or c corresponds to the number of the injected microspheres of each size (see Table 1). Bars indicate means ± SD of all animals. B: illustration of the correlation between the total surface area of nonperfused myocardium, as determined by micro-CT, with the embolization-induced increase (%) in diastolic anterior wall (AW) thickness (as the surrogate of myocardial edema) as determined by EBCT. *P < 0.01, embolized vs. baseline (excluding the control animal).

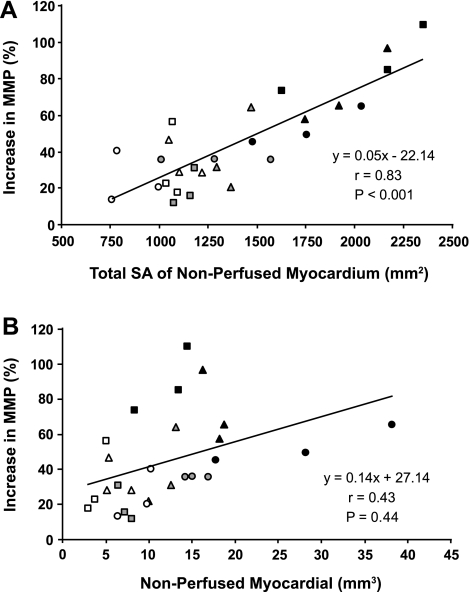

Micro-CT findings.

The volumes of nonperfused myocardial and the corresponding surface area of the embolization islands are presented in Fig. 5, A and B. The EBCT-derived increase in microvascular permeability for iopamidol following embolization was well correlated with the total surface area of the nonperfused myocardium (r = 0.83, P < 0.01, Fig. 5A) but showed weak correlation to the total nonperfused myocardial volume (r = 0.43, P = 0.04, Fig. 5B). By linear regression analysis, the microvascular permeability was related highly significant (P < 0.001) to the total surface area but not to the nonperfused myocardial volume (P = 0.44).

Fig. 5.

Linear regression analysis illustrating the relationship of increase in myocardial microvascular permeability (MMP, %) to the total surface area (SA) per gram myocardium (A) and to the volume of nonperfused myocardium per gram myocardium (B). Squares = 10 μm, triangles = 30-μm, and circles = 100 μm microspheres, each size at the 3 different doses (white = low dose; grey = medium dose; black = high dose). For the exact number of the injected microspheres see Table 1.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that coronary microembolization with microspheres results in enhanced coronary endothelial vascular permeability in the embolized LAD perfusion territory. The lack of increase in permeability in the nonembolized LCX perfusion territory supports our first hypothesis that the increase in permeability is due to microembolization. Our second hypothesis, that the surface area of the interface between the nonperfused and perfused myocardium is the primary location of increased permeability, is supported by the high correlation between the increase of microvascular permeability and the total surface area of embolized, nonperfused myocardium (Fig. 5A). Similarly, the increase in diastolic wall thickness in vivo, and thereby the increase in volume of LAD perfusion territory, as an index of myocardial edema, is highly correlated to the total surface area of the embolized myocardial territories ex vivo (Fig. 4B).

In this study, we found that increased permeability is proportional to the total surface area of perfusion defects. For the same dose of different sizes of microspheres, the increase in permeability was more pronounced in animals embolized with smaller-sized microspheres (Fig. 3). One of the possible mechanisms may stem from the geometric relationship of the surface area-to-volume ratio of perfusion defects that decreases as N(−0.67), where N is the number of perfusion defects. However, this difference cannot solely be explained by the difference in the total surface area, since the increase in permeability exceeded by far the difference in the surface area. For instance, the surface area of nonperfused myocardium secondary to embolization by the highest dose of 10 μm microspheres was slightly higher than that caused by the 100 μm microspheres (Fig. 5A), but the increase in permeability was for the 10 μm microspheres twofold of that for the 100 μm. Addressing the pathophysiological mechanisms for the observed differences in permeability when blocking different-sized coronary microvessels is beyond the focus of this study; however, it reasonable to assume that blocking of the 10-μm exchange vessels would affect more directly the physiology of exchange vessels, resulting in greater increase of permeability, whereas the blockage of the upstream 100-μm conduit vessels would result in larger individual nonperfused territories but would have less affect on permeability, since the downstream 10-μm vessels do not receive contrast to leak. Notably, the change of permeability in vivo, an important element of physiological coronary microvascular function, exhibited in this study an inverse relationship with the size of the embolized coronary arterioles. Our observation is consistent with a longitudinal gradient in metabolic, myogenic, and flow-induced responses to various physiological and pharmacological stimuli in coronary microcirculation as previously described by other investigators using an in vitro approach (19).

Increase of vascular permeability results in enhanced movements of fluids and solutes (39), as well as inflammatory mediators, from the intravascular into the interstitial and/or intracellular compartment, leading to change of cellular and extracellular osmolarity, disturbance of cell membrane conductivity, cell swelling, and interstitial edema (38), thereby compromising myocardial contractile function and potentially leading to lethal arrhythmias (12, 38). Inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α, free oxygen radicals, and interleukins have been shown to play a major role in contractile dysfunction in the microembolized myocardium following coronary microembolization (15, 17, 34), possibly indicating the role of inflammation and/or edema in its pathogenesis. Such mediators can likely more easily diffuse into the perfused myocardium from the interfacial region between perfused and nonperfused myocardium (i.e., proportional to the interface's surface area) rather than from deep within the nonperfused myocardium, which would make the effect more proportional to the volume of nonperfused myocardium.

Increased permeability is a characteristic consequence of coronary endothelial dysfunction and is considered a major pathogenic mechanism in atherosclerosis (40). However, this important index of microvascular integrity is difficult to assess noninvasively and longitudinally in the beating heart. Our CT methodology enables sequential evaluation of regional myocardial microvascular permeability to X-ray contrast media. Using this method and a similar model of coronary microembolization, we have previously shown that microembolization resulted in a contiguous spectrum of perfusion defects that were related to the number of injected microspheres (22). We further demonstrated that the total surface area in a given volume of embolized myocardium was related to the total number of perfusion defects and to the consequent regional myocardial contractile dysfunction (23). Nevertheless, the relationship between the surface area of myocardial perfusion defects and the increase in microvascular permeability following experimental microembolization remained unknown.

Indeed, this study suggests that the previously reported microembolization-induced contractile dysfunction (23, 34) may be related, at least in part, to myocardial edema resulting from increased permeability, as demonstrated by increased diastolic wall thickness and increased volume of myocardium within the LAD perfusion territory (Fig. 4A). The increase in diastolic wall thickness and in the volume of the LAD perfusion territory following embolization cannot be attributed to the volume of the injected microspheres, since the total volume of spheres injected in each animal was negligible (i.e., <3 mm3) compared with the increase in tissue volume, which was ≥ 5 cm3 (Fig. 4A). Unlike myocardial infarction due to occlusion of an epicardial artery, where the chronic increase in LV muscle volume in the remote and infarct border region is mainly attributed to compensatory myocyte hypertrophy, an immediate and transient increase in diastolic wall thickness following embolization strongly suggests a consequence of myocardial edema, since an interval of minutes between the onset of embolization and the observed effect (increase in diastolic wall thickness) is too short for the process of myocellular hypertrophy. Furthermore, the close correlation between the increased diastolic wall thickness and the total surface area of the nonperfused regions (Fig. 4B) in this study supports our primary hypothesis of the perfusion/nonperfusion interface surface area as the primary location for increased permeability to fluid and solutes.

Study limitations.

Although the porcine coronary artery and coronary physiology resembles that of humans, microembolization by biological particles, as it occurs in a clinical setting, might have different and/or additional consequences compared with experimental coronary microembolization by essentially inert microspheres. It is likely that the increase in microvascular permeability due to ischemia and inflammation induced by biological particles would be more pronounced than to inert microspheres. Nonetheless, the current study underscores that the physical obstruction by inert microspheres also leads to increased vascular permeability. It is conceivable that some of the larger vessels in this study were occluded by aggregate of smaller-sized microspheres, and/or that contiguous perfusion territories were embolized by individual microspheres, thereby perturbating the accurate relationship between the diameter of the occluded vessel and the extent of vascular permeability. In addition, we studied relatively young pigs, and vascular permeability may be partly age dependent (5, 11). Nevertheless, this animal study strongly suggests that patchy occlusion of the coronary microvasculature results in enhanced extravasation of fluids and solutes.

Conclusion.

Experimental coronary microembolization results in an increase of vascular permeability primarily by increasing the capillary extraction at the interface between perfused and the nonperfused territories for fluid and solutes, such as for the nonionic contrast agent iopamidol. The increase in vascular permeability is highly correlated to the total surface area of the nonperfused myocardium, indicating that the increase in permeability is mainly due to increased leakiness of the microvasculature at the surface area of the individual ischemic islands and normally perfused myocardium.

Perspectives and Significance

Increased microvascular permeability, a key characteristic feature of endothelial dysfunction and a precursor of atherogenesis, might result from exposure to cardiovascular risk factors, preceding clinical signs or detectable vascular remodeling processes. This is the first study in animal model not only illustrating the extent and the time course of the permeability following coronary microembolization but also showing that its magnitude is in proportion to the surface area of the interface between the perfused and nonperfused myocardial territories.

Exploring the pathophysiological mechanisms and consequences of altered coronary microvascular permeability in the sequelae of coronary microembolization might extend our understanding of phenomena, such as the discrepant relation of nonperfused myocardial volume to a magnitude of decrease in LV performance (22, 23), transient regional myocardial dysfunction, its functional recovery, and perfusion-contraction mismatch. This, in turn, may contribute toward identifying new therapeutic targets in patients at risk for coronary microembolization.

GRANTS

This study was funded in part by National Institutes of Health research grants HL-43025, EB-000305, and HL-72255.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Patricia E. Beighley was a dedicated and amiable expert member of our team throughout the studies. We acknowledge the help and assistance from the radiology technical staff operating the electron-beam CT scanner.

REFERENCES

- 1. Albers J, Schroeder A, de Simone R, Mockel R, Vahl CF, Hagl S. 3D evaluation of myocardial edema: experimental study on 22 pigs using magnetic resonance and tissue analysis. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 49: 199–203, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Angelini A, Rubartelli P, Mistrorigo F, Della Barbera M, Abbadessa F, Vischi M, Thiene G, Chierchia S. Distal protection with a filter device during coronary stenting in patients with stable and unstable angina. Circulation 110: 515–521, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beighley PE, Thomas PJ, Jorgensen SM, Ritman EL. 3D architecture of myocardial microcirculation in intact rat heart: a study with micro-CT. Adv Exp Med Biol 430: 165–175, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bell MR, Lerman LO, Rumberger JA. Validation of minimally invasive measurement of myocardial perfusion using electron beam computed tomography and application in human volunteers. Heart 81: 628–635, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Belmin J, Corman B, Merval R, Tedgui A. Age-related changes in endothelial permeability and distribution volume of albumin in rat aorta. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 264: H679–H685, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bonetti PO, Wilson SH, Rodriguez-Porcel M, Holmes DR, Jr, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Simvastatin preserves myocardial perfusion and coronary microvascular permeability in experimental hypercholesterolemia independent of lipid lowering. J Am Coll Cardiol 40: 546–554, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. El-Maraghi N, Genton E. The relevance of platelet and fibrin thromboembolism of the coronary microcirculation, with special reference to sudden cardiac death. Circulation 62: 936–944, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Emanuelsson H, Holmberg S, Selin K, Waagstein F. Effects of iohexol and metrizoate on myocardial blood flow and metabolism. Acta Radiol Suppl 366: 121–125, 1983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Erbel R, Heusch G. Spontaneous and iatrogenic microembolization. A new concept for the pathogenesis of coronary artery disease. Herz 24: 493–495, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Falk E. Unstable angina with fatal outcome: dynamic coronary thrombosis leading to infarction and/or sudden death. Autopsy evidence of recurrent mural thrombosis with peripheral embolization culminating in total vascular occlusion. Circulation 71: 699–708, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gamble J, Bethell D, Day NP, Loc PP, Phu NH, Gartside IB, Farrar JF, White NJ. Age-related changes in microvascular permeability: a significant factor in the susceptibility of children to shock? Clin Sci (Lond) 98: 211–216, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Garcia-Dorado D, Oliveras J. Myocardial oedema: a preventable cause of reperfusion injury? Cardiovasc Res 27: 1555–1563, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gossl M, Rosol M, Malyar NM, Fitzpatrick LA, Beighley PE, Zamir M, Ritman EL. Functional anatomy and hemodynamic characteristics of vasa vasorum in the walls of porcine coronary arteries. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol 272: 526–537, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Haasler GB, Rodigas PC, Collins RH, Wei J, Meyer FJ, Spotnitz AJ, Spotnitz HM. Two-dimensional echocardiography in dogs. Variation of left ventricular mass, geometry, volume, and ejection fraction on cardiopulmonary bypass. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 90: 430–440, 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hansen PR, Svendsen JH, Hoyer S, Kharazmi A, Bendtzen K, Haunso S. Tumor necrosis factor-α increases myocardial microvascular transport in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 266: H60–H67, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Higgins CB. Cardiotolerance of iohexol. Survey of experimental evidence. Invest Radiol 20, Suppl 1: S65–S69, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hori M, Gotoh K, Kitakaze M, Iwai K, Iwakura K, Sato H, Koretsune Y, Inoue M, Kitabatake A, Kamada T. Role of oxygen-derived free radicals in myocardial edema and ischemia in coronary microvascular embolization. Circulation 84: 828–840, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jorgensen SM, Demirkaya O, Ritman EL. Three-dimensional imaging of vasculature and parenchyma in intact rodent organs with X-ray micro-CT. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 275: H1103–H1114, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kuo L, Davis MJ, Chilian WM. Longitudinal gradients for endothelium-dependent and -independent vascular responses in the coronary microcirculation. Circulation 92: 518–525, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lerman A, Ritman EL. Evaluation of microvascular anatomy by micro-CT. Herz 24: 531–533, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu YH, Bahn RC, Ritman EL. Microvascular blood volume-to-flow relationships in porcine heart wall: whole body CT evaluation in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 269: H1820–H1826, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Malyar NM, Gossl M, Beighley PE, Ritman EL. Relationship between arterial diameter and perfused tissue volume in myocardial microcirculation: a micro-CT-based analysis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 286: H2386–H2392, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Malyar NM, Lerman LO, Gossl M, Beighley PE, Ritman EL. Relation of nonperfused myocardial volume and surface area to left ventricular performance in coronary microembolization. Circulation 110: 1946–1952, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McDonagh PF, Hokama JY. Microvascular perfusion and transport in the diabetic heart. Microcirculation 7: 163–181, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mohlenkamp S, Behrenbeck TR, Lerman A, Lerman LO, Pankratz VS, Sheedy PF, 2nd, Weaver AL, Ritman EL. Coronary microvascular functional reserve: quantification of long-term changes with electron-beam CT preliminary results in a porcine model. Radiology 221: 229–236, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mohlenkamp S, Beighley PE, Pfeifer EA, Behrenbeck TR, Sheedy PF, 2nd, Ritman EL. Intramyocardial blood volume, perfusion and transit time in response to embolization of different sized microvessels. Cardiovasc Res 57: 843–852, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mohlenkamp S, Lerman LO, Lerman A, Behrenbeck TR, Katusic ZS, Sheedy PF, 2nd, Ritman EL. Minimally invasive evaluation of coronary microvascular function by electron beam computed tomography. Circulation 102: 2411–2416, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Powell WJ, Jr, Wittenberg J, Maturi RA, Dinsmore RE, Miller SW. Detection of edema associated with myocardial ischemia by computerized tomography in isolated, arrested canine hearts. Circulation 55: 99–108, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ritman EL. Computed tomography evaluation of regional increases in microvascular permeability after reperfusion of locally ischemic myocardium in intact pigs. Acad Radiol 2: 952–958, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ritman EL. Myocardial capillary permeability to iohexol. Evaluation with fast X-ray computed tomography. Invest Radiol 29: 612–617, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rodriguez-Porcel M, Herrman J, Chade AR, Krier JD, Breen JF, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Long-term antioxidant intervention improves myocardial microvascular function in experimental hypertension. Hypertension 43: 493–498, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rodriguez-Porcel M, Lerman A, Best PJ, Krier JD, Napoli C, Lerman LO. Hypercholesterolemia impairs myocardial perfusion and permeability: role of oxidative stress and endogenous scavenging activity. J Am Coll Cardiol 37: 608–615, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schmermund A, Bell MR, Lerman LO, Ritman EL, Rumberger JA. Quantitative evaluation of regional myocardial perfusion using fast X-ray computed tomography. Herz 22: 29–39, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thielmann M, Dorge H, Martin C, Belosjorow S, Schwanke U, van De Sand A, Konietzka I, Buchert A, Kruger A, Schulz R, Heusch G. Myocardial dysfunction with coronary microembolization: signal transduction through a sequence of nitric oxide, tumor necrosis factor-α, and sphingosine. Circ Res 90: 807–813, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Topol EJ, Yadav JS. Recognition of the importance of embolization in atherosclerotic vascular disease. Circulation 101: 570–580, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Turschner O, D'Hooge J, Dommke C, Claus P, Verbeken E, De Scheerder I, Bijnens B, Sutherland GR. The sequential changes in myocardial thickness and thickening which occur during acute transmural infarction, infarct reperfusion and the resultant expression of reperfusion injury. Eur Heart J 25: 794–803, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Weaver ME, Pantely GA, Bristow JD, Ladley HD. A quantitative study of the anatomy and distribution of coronary arteries in swine in comparison with other animals and man. Cardiovasc Res 20: 907–917, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Weis S, Shintani S, Weber A, Kirchmair R, Wood M, Cravens A, McSharry H, Iwakura A, Yoon YS, Himes N, Burstein D, Doukas J, Soll R, Losordo D, Cheresh D. Src blockade stabilizes a Flk/cadherin complex, reducing edema and tissue injury following myocardial infarction. J Clin Invest 113: 885–894, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Weis SM, Cheresh DA. Pathophysiological consequences of VEGF-induced vascular permeability. Nature 437: 497–504, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wu CC, Chang SW, Chen MS, Lee YT. Early change of vascular permeability in hypercholesterolemic rabbits. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 15: 529–533, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yamaji T, Fukuhara T, Kinoshita M. Increased capillary permeability to albumin in diabetic rat myocardium. Circ Res 72: 947–957, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]