Abstract

In the ventral cochlear nucleus (VCN), neurons have hyperpolarization-activated conductances, which in some cells are enormous, that contribute to the ability of neurons to convey acoustic information in the timing of their firing by decreasing the input resistance and speeding-up voltage changes. Comparisons of the electrophysiological properties of neurons in the VCN of mutant mice that lack the hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channel α subunit 1 (HCN1−/−) (Nolan et al. 2003) with wild-type controls (HCN1+/+) and with outbred ICR mice reveal that octopus, T stellate, and bushy cells maintain their electrophysiological distinctions in all strains. Hyperpolarization-activated (Ih) currents were smaller and slower, input resistances were higher, and membrane time constants were longer in HCN1−/− than in HCN1+/+ in octopus, bushy, and T stellate cells. There were significant differences in the average magnitudes of Ih, input resistances, and time constants between HCN1+/+ and ICR mice, but the resting potentials did not differ between strains. Ih is opposed by a low-voltage-activated potassium (IKL) current in bushy and octopus cells, whose magnitudes varied widely between neuronal types and between strains. The magnitudes of Ih and IKL were correlated across neuronal types and across mouse strains. Furthermore, these currents balanced one another at the resting potential in individual cells. The magnitude of Ih and IKL is linked in bushy and octopus cells and varies not only between HCN1−/− and HCN1+/+ but also between “wild-type” strains of mice, raising the question to what extent the wild-type strains reflect normal mice.

Keywords: KCNA, hearing, brain stem, electrophysiology, patch-clamp recordings, homeostasis

in the auditory system, the timing of firing carries sensory information. In mammals that hear low frequencies, neuronal encoding of the phase of sounds is the basis for the ability to resolve differences in pitch and to use differences in the time of arrival of sound at the two ears to localize sounds in the horizontal plane. Making use of high frequencies, too, requires temporal precision. To detect interaural intensity differences for localizing sounds, monosynaptic excitation from the ipsilateral cochlear nucleus must be matched in timing with disynaptic inhibition from the contralateral cochlear nucleus at the lateral superior olive within fractions of a millisecond (Joris and Yin 1995). In mammals that hear only high frequencies, including mice and bats, neurons cannot encode the phase of individual cycles of sounds, but they encode the phase of amplitude modulation (Gans et al. 2009).

The auditory pathway is subdivided in the ventral cochlear nucleus (VCN) into multiple pathways that differ in the acoustic information that they carry and in the routes that they take through the brain stem to the inferior colliculus. Bushy cells convey the fine structure of sounds in the timing of their firing that is used to localize sound sources (Yin 2002). Octopus cells detect the presence of broad-band transients and convey information to the superior paraolivary nucleus and to the ventral nucleus of the lateral lemniscus (Adams 1997; Schofield 1995; Smith et al. 2005). Individual bushy and octopus cells respond with action potentials that fall within sharper time windows (200 μs) than their auditory nerve inputs (Joris et al. 1998; Oertel et al. 2000; Smith et al. 2005). The population of T stellate cells conveys information about the spectrum of sounds in the rate and duration of tonic firing that is independent of the fine structure to many brain stem auditory nuclei and to the inferior colliculus (Blackburn and Sachs 1990; May et al. 1998; Oertel et al. 2011).

Each of the classes of principal cells is endowed with a hyperpolarization-activated, mixed-cation (gh) conductance. Sharpening and conveying the timing of firing of auditory nerve inputs by bushy and octopus cells depend on the presence of gh and an opposing rapid, low-voltage-activated potassium conductance (gKL) (Bal and Oertel 2000, 2001; Cao et al. 2007; Ferragamo and Oertel 2002; Golding et al. 1995, 1999; Manis and Marx 1991; McGinley and Oertel 2006; Rothman and Manis 2003). T stellate cells have gh but little or no gKL (Ferragamo and Oertel 2002; Rodrigues and Oertel 2006). gh and gKL are also present in inputs and targets of principal cells of the VCN. gh is prominent in spiral ganglion cells (Mo and Davis 1997), cells in the superior olivary complex, and in the ventral nucleus of the lateral lemniscus (Banks et al. 1993; Cuttle et al. 2001; Hassfurth et al. 2009; Koch et al. 2004; Leao et al. 2005, 2006; Notomi and Shigemoto 2004; Scott et al. 2005; Wu 1999).

The hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated (HCN) channels that mediate gh are composed of HCN1–4 α subunits (Ludwig et al. 1998; Robinson and Siegelbaum 2003). All four subunits are expressed in the VCN, and HCN1, HCN2, and HCN4 are expressed at high levels (Koch et al. 2004; Moosmang et al. 1999; Notomi and Shigemoto 2004). HCN channels are tetrameric, voltage-gated, pore-loop ion channels. Homomeric HCN1 channels have the most rapid kinetics, HCN2 channels are slower, and HCN4 the slowest (Moosmang et al. 2001; Santoro et al. 1998); heteromeric channels have properties intermediate between those of the corresponding homomers (Altomare et al. 2003; Ulens and Tytgat 2001; Whitaker et al. 2007). HCN1 is strongly expressed in the octopus cell area, less strongly expressed in the anterior VCN, where most bushy cells are located, and least strongly expressed in the multipolar cell area (Bal and Oertel 2000; Koch et al. 2004; Oertel et al. 2008).

The ion channels that mediate gKL also belong to the family of voltage-gated, pore-loop ion channels; specifically, they are potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily A (KCNA; also known as Kv1 or shaker) channels. These channels are formed from KCNA1–4 and/or KCNA6 α subunits, KCNA1 and KCNA2 being the most abundant (Bal and Oertel 2001; Oertel et al. 2008).

The present study was motivated by a search for mice that hear through biophysically abnormal neurons. The elimination of HCN1 produces mice that are generally healthy but have subtle defects in motor learning (Nolan et al. 2003). We find that these mice do have cochlear nuclear neurons with smaller gh than the wild-type, but they also differ from the wild-type in unexpected ways.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Mice that lack the HCN1 subunit were genetically engineered by Nolan et al. (2003); the mice used for the present experiments were propagated by inbreeding from a breeding pair purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). We routinely test the hearing of mice by looking for a Preyer reflex in response to a click generated by a dog-training clicker. In this crude test of hearing, mice that lack the HCN1 α subunit (HCN1−/−) responded indistinguishably from the wild-type controls (HCN1+/+) and ICR (Harlan, Madison, WI) mice; mice of all three strains freeze briefly in response to the click.

HCN1−/− mice were constructed from 129S/SvEv-derived MM13 embryonic stem cells that were injected into C57BL/6 mice. The HCN1−/− mice are therefore on a hybrid genetic background, derived by mixing two different strains, for which we could not obtain a perfect control strain. In this study, we compare mutant HCN1−/− mice with two groups of mice. One group comprises F2 hybrids from crosses between 129S and C57Bl/6 parents, which we term “wild-type controls” or HCN1+/+. These HCN1+/+ mice were not the same as the HCN1+/+ mice described by Nolan et al. (2003). We also compare HCN1−/− and HCN1+/+ with outbred ICR mice, which we have used in previous biophysical studies (Bal and Oertel 2000, 2001; Cao and Oertel 2005; Cao et al. 2007; Rodrigues and Oertel 2006).

Preparation of slices.

Coronal brain stem slices from mice between 16 and 19 days after birth and containing the VCN were prepared from ICR mice, HCN1−/−, or HCN1+/+. All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the School of Medicine and Public Health.

Slices were cut in normal physiological saline that contained (in mM): 130 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 2.4 CaCl2, 1.3 MgSO4, 20 NaHCO3, 3 HEPES, 10 glucose, saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2, pH 7.3–7.4, at between 24°C and 27°C. The osmolality, measured with a 3D3 osmometer (Advanced Instruments, Norwood, MA), was 306 mosmol/kg. All chemicals were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), unless stated otherwise. Slices, 210 μm-thick, were cut with a vibrating microtome (Leica VT 1000S). After cutting, slices were transferred to the recording chamber (∼0.6 ml) and superfused continually at 5–6 ml/min. Slices were mounted on the stage of a compound microscope (Zeiss Axioskop) and viewed through a 63× water immersion objective. The temperature was measured in the recording chamber, between the inflow of the chamber and the tissue, with a Thermalert thermometer (Physitemp Instruments, Clifton, NJ), the input of which comes from a small thermistor (IT-23; diameter: 0.1 mm; Physitemp Instruments). The output of the Thermalert thermometer was fed into a custom-made, feedback-controlled heater that heated the saline in glass tubing (1.5-mm inside diameter, 3-mm outside diameter) just before it reached the chamber. An adjustable delay in the controller for the heater prevented temperature oscillations. Recordings were generally made within 2 h after slices were cut.

Electrophysiological recordings.

Patch-clamp recordings were made with pipettes made from borosilicate glass, which were filled with a solution consisting of (in mM): 108 potassium gluconate, 9 HEPES, 9 EGTA, 4.5 MgCl2, 14 phosphocreatine (tris salt), 4 ATP (Na salt), 0.3 GTP (tris salt). The pH was adjusted to 7.4 with KOH; the osmolality was 303 mosmol/kg. Resistances ranged between 4 and 6 MΩ. Recordings were made with an Axopatch 200A amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Records were digitized at 50 kHz and low-pass filtered at 10 kHz. All reported results were from recordings in which 75∼90% of the series resistance could be compensated online with 10 μs lag; no corrections were made for errors in voltage that resulted from uncompensated series resistance. Series resistances were between 10 and 14 MΩ in each of the cell types, of which, ∼90% could be compensated in octopus cells and ∼75–80% could be compensated in bushy and T stellate cells. Recordings, in which series resistances were >14 MΩ, were disregarded. The output was digitized through a Digidata 1320A interface (Molecular Devices) and fed into a computer. Stimulation and recording were controlled by pClamp 8 software (Molecular Devices). The control solution contained (in mM): 138 NaCl, 4.2 KCl, 2.4 CaCl2, 1.3 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, pH 7.4, saturated with 100% O2. In voltage-clamp experiments to measure hyperpolarization-activated (Ih) or low-voltage-activated potassium (IKL) current, the voltage-sensitive sodium current was blocked by 1 μM TTX, the voltage-sensitive calcium current was blocked by 0.25 mM CdCl2, and glutamatergic and glycinergic synaptic currents were blocked with 40 μM 6,7-dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (DNQX; Tocris Cookson, UK) and 1 μM strychnine, respectively. Measurements of Ih were made in the additional presence of 50 nM α-dendrotoxin (α-DTX) to block IKL (Bal and Oertel 2000). Measurements of IKL were made in the presence of 50 μM ZD7288 to block Ih. All reported voltages were compensated for a −12-mV junction potential.

Data analysis.

Input resistances were measured as the slope of plots of voltage responses to small hyperpolarizing current steps. The slope was measured over the region ∼10 mV from the resting potential.

Activation and deactivation time constants of Ih were determined by fitting the current evoked during an activating or deactivating pulse to double or single exponential functions of the form: Ih(t) = Iss + Afe−t/τf + Ase−t/τs, where Ih(t) is the current at time t; Iss is the steady-state current; Af and As are the fast and slow initial amplitude of exponential component, respectively; and τf and τs are fast and slow time constants, respectively. Statistical analyses were made with Origin software (version 7.5; OriginLab, Northampton, MA); the results are given as means ± SD; n is the number of cells in which the measurement was made.

RESULTS

Neurons in HCN1−/− mice have higher input resistances and longer time constants than HCN1+/+ strains.

In the VCN, the intermingled groups of principal neurons have distinct biophysical properties that allow them to be recognized electrophysiologically. Octopus cells have low-input resistances that result from the partial activation of gh and gKL and fire only at the onset of a depolarization (Bal and Oertel 2000, 2001; Golding et al. 1995, 1999). In bushy cells, depolarization also produces transient firing, but gh and gKL are smaller than in octopus cells (Cao et al. 2007). T and D stellate neurons fire tonically when they are depolarized but differ in the shapes of their action potentials and in the kinetics of gh; T stellate cells are common excitatory principal cells, whereas D stellate cells are more rare inhibitory neurons that innervate the ipsilateral and contralateral cochlear nuclei and will not be considered in this study (Fujino and Oertel 2001; Needham and Paolini 2003; Oertel et al. 1990; Rodrigues and Oertel 2006).

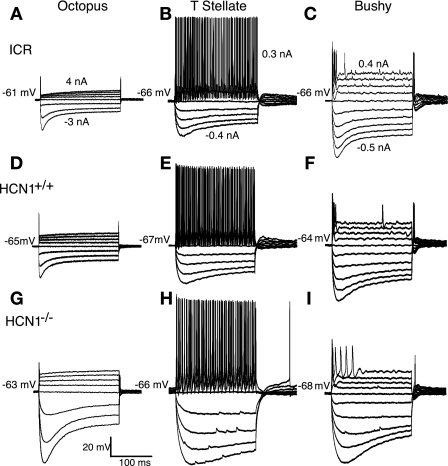

The three major populations of neurons—octopus, T stellate, and bushy cells—remain recognizable in mice that lack HCN1 (Fig. 1). Although their biophysical properties differ, the groups of neurons retain their characteristic features. In whole-cell, patch-clamp recordings, large currents were required to evoke a single action potential in octopus cells of all three groups of mice. As in mice with HCN1, smaller depolarizing current pulses evoked tonic firing in T stellate cells and transient firing in bushy cells of mice that lack HCN1. Currents evoked larger voltage changes in HCN1−/− than in the same cell type from HCN1+/+ and ICR mice, reflecting their higher input resistances. Hyperpolarizing current pulses evoked voltage changes that were initially large and then sagged back toward rest. The sag was slower in HCN1−/− than in the HCN1+/+ or ICR mice.

Fig. 1.

Responses to current pulses reflect the intrinsic electrical properties of neurons. A–C: recordings from octopus, T stellate, and bushy cells in ICR mice illustrate the differences that distinguish them. Depolarizing current pulses caused octopus cells to fire transiently with a single action potential, bushy cells to fire transiently with several action potentials, and T stellate cells to fire tonically. Hyperpolarizing current pulses resulted in a polarization that sags back toward rest, reflecting the activation of hyperpolarization-activated (Ih) current. D–F: responses to current in neurons from hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated 1 channel wild-type control (HCN1+/+) mice are generally similar to those in ICR mice, reflecting the characteristic differences among octopus, T stellate, and bushy cells. G–I: corresponding recordings from neurons in mice that lack the HCN1 α subunit (HCN1−/−) also show similar overall characteristics. Current pulses evoke larger polarizations in HCN1−/− mice than in the strains that contain HCN1, reflecting their higher input resistances. Amplitudes of current pulses, given in the upper panels, were matched in ICR, HCN1+/+, and mutant HCN1−/− neurons.

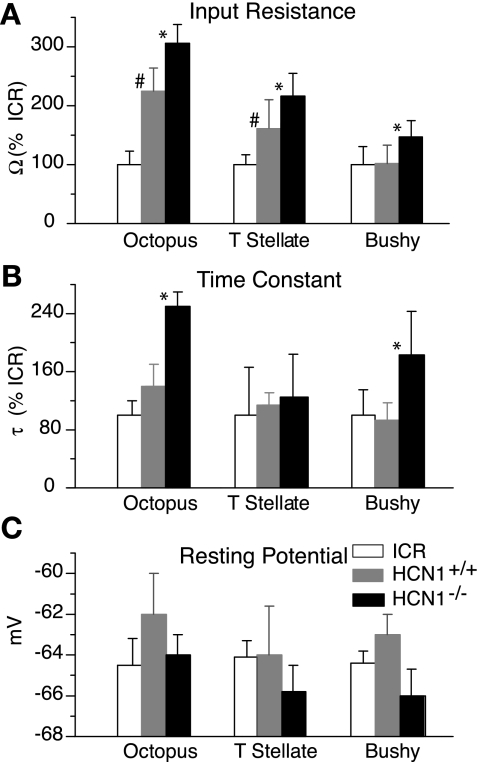

Input resistances were assessed from steady-state voltage changes produced by the injection of small current pulses that elicited hyperpolarizations <10 mV (Fig. 2A and Table 1). The input resistances of octopus cells were significantly higher in mutant HCN1−/− mice (19 MΩ) than in HCN1+/+ mice (14 MΩ; P < 0.05). There was, surprisingly, a large difference in input resistance between octopus cells in HCN1+/+ (14 MΩ) and in ICR mice (6 MΩ). In T stellate cells, the input resistances around rest were also significantly higher in HCN1−/− (160 MΩ) than in HCN1+/+ (126 MΩ; P < 0.05), and there was a difference in input resistance between HCN1+/+ (126 MΩ) and ICR mice (74 MΩ). In bushy cells, the input resistance was ∼70 MΩ in HCN1+/+ compared with ∼100 MΩ in HCN1−/− mice (P < 0.05); input resistances were similar in HCN1+/+ and ICR mice.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of characteristics of principal cells from ICR, HCN1+/+, and mutant HCN1−/− mice. A: input resistances (Ω) were significantly higher in HCN1−/− mutants than in HCN1+/+ in all 3 types of principal cells. The input resistances were also significantly higher in octopus and T stellate cells of HCN1+/+ than in ICR mice. B: the time constants (τ) were longer in octopus and bushy cells of HCN1−/− than in the HCN1+/+. Time constants were not significantly different in ICR and HCN1+/+ in any of the cell types. C: there were no significant differences in the resting potentials (mV) of neurons in the 3 strains of mice. Mean values ± SD are indicated by bars. *Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) between mutant HCN1−/− mice and HCN1+/+, straddling the bars being compared. #Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) between the HCN1+/+ and ICR mice.

Table 1.

Comparison of properties of neurons in ICR, HCN1+/+, and HCN1−/− mice

| Octopus |

T stellate |

Bushy |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICR | HCN1+/+ | HCN1−/− | ICR | HCN1+/+ | HCN1−/− | ICR | HCN1+/+ | HCN1−/− | |

| Input resistance (MΩ) | 6 ± 2 (10)* | 14 ± 2 (8) | 19 ± 3 (19)† | 74 ± 11 (12)* | 126 ± 11 (7) | 160 ± 27 (9)† | 67 ± 17 (36) | 68 ± 22 (11) | 99 ± 24 (12)† |

| Time constant (ms) | 0.2 ± 0.1 (9) | 0.3 ± 0.2 (8) | 0.5 ± 0.1 (5)† | 6.0 ± 2.7 (12) | 6.8 ± 1 (6) | 7.5 ± 3.2 (8) | 1.4 ± 0.5(18) | 1.2 ± 0.3(10) | 2.6 ± 1.1 (11)† |

| Resting potential (mV) | −64.5 ± 1.3 (8) | −62 ± 2 (13) | −64 ± 1 (5) | −64.1 ± 0.8 (10) | −64 ± 2.4 (8) | −65.8 ± 1.3(13) | −64.4 ± 0.6 (9) | −63 ± 1 (8) | −66 ± 1.3 (6) |

| Activation of gh: τf −57 → −107 mV (ms) | 23 ± 4 (7) 81% | 100 ± 19 (6) 63% | 270 ± 34 (5) 60% | 140 ± 35 (5) 45% | 162 ± 54 (5) 57% | 460 ± 84 (5) 44% | 94 ± 17 (7) 54% | 116 ± 38 (9) 56% | 490 ± 94 (8) 45% |

| Activation of gh: τs −57 → −107 mV (ms) | 99 ± 23 (7) 19% | 1131 ± 396 (6) 37% | 2120 ± 760 (5) 40% | 770 ± 200 (5) 55% | 1053 ± 404 (5) 43% | 2430 ± 480 (5) 56% | 630 ± 130 (7) 46% | 945 ± 215 (9) 44% | 2790 ± 670 (8) 55% |

| Deactivation of gh: τ −107 → −57 mV (ms) | 107 ± 21 (7)* | 307 ± 79 (6) | 430 ± 41 (5)† | 275 ± 78 (5) | 313 ± 74 (5) | 440 ± 94 (5)† | 196 ± 34 (7)* | 329 ± 54 (9) | 437 ± 117 (8)† |

Summary of the differences in the properties of neurons in mice of different strains. Numbers are given as means ± SD, with the number of cells from which measurements were made given in parentheses.

Significance of difference, P < 0.05, between ICR and hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated 1 channel wild-type control (HCN1+/+).

Significance of difference, P < 0.05, between mice that lack the HCN1 α subunit (HCN1−/−) and HCN1+/+. gh, Hyperpolarization-activated, mixed-cation conductance; τf and τs, fast and slow time constants, respectively.

Time constants determine how voltage changes are shaped from synaptic inputs and therefore, limit the temporal precision with which these neurons can signal. The rate at which the voltage falls at the offset of a depolarizing current pulse is biologically most interesting, because that is the physiological voltage range. The voltage changes could be fit roughly with a single exponential function. As expected from their elevated input resistances, time constants were longer in HCN1−/− than in HCN1+/+ neurons (Fig. 2B and Table 1). Time constants in octopus cells from HCN1−/− mice (0.5 ms) were longer than those in HCN1+/+ strains (0.2–0.3 ms). They were also significantly longer in bushy cells from HCN1−/− mice (2.6 ms) than in HCN1+/+ (1.2 ms). For both octopus and bushy cells, there were no significant differences in time constants of HCN1+/+ and ICR mice. Time constants were similar in T stellate cells of all three strains. Presumably, the time constants do not exactly parallel input resistances, because the characteristics of neurons over this voltage range were not passive but rather, were affected by gh and gKL.

Resting potentials of neurons are not different in the three strains of mice.

In the face of a presumed loss of inward Ih at rest, one might expect the resting potentials to be hyperpolarized, but that was not the case. Resting potentials in all three cell types were not statistically different among the three strains (Fig. 2C and Table 1).

Measurements of Ih.

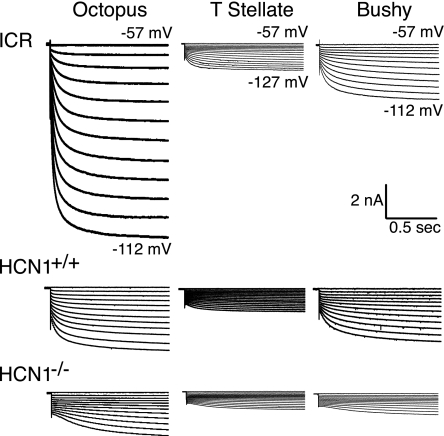

Recordings in voltage-clamp show how the loss of HCN1 affects the magnitude and kinetics of Ih. Examples of recordings from individual cells to identical voltage steps are shown in Fig. 3. To avoid contamination of Ih with other currents, recordings were made in the presence of 40 μM DNQX, 1 μM strychnine, 1 μM TTX, 0.25 mM Cd2+, and 50 nM α-DTX. In all neurons, the instantaneous current step was followed by the growth of Ih; the rates of activation were slower in HCN1−/− than in HCN1+/+ and ICR neurons. Ih was largest in octopus cells, intermediate in bushy cells, and smallest in T stellate cells; in HCN1−/− mice, Ih was smaller than in the HCN1+/+ and ICR mice in all three groups of cells.

Fig. 3.

Ih is smaller and slower in HCN1−/− mutant neurons than in HCN1+/+ or ICR neurons. Examples of recordings of Ih evoked by hyperpolarizing voltage steps from the holding potential of −57 mV in 5-mV increments to the levels indicated by numbers at the right of the traces. The steps evoked an instantaneous current that was proportional to the input conductance of the neurons; the inward current then increased gradually as Ih was activated. Ih was largest in octopus cells, intermediate in bushy cells, and smallest in T stellate cells of HCN1+/+ and ICR mice; in HCN1−/− mutant mice, Ih was similar in T stellate and bushy cells. Note that Ih activated more slowly in HCN1−/− neurons that lack HCN1 (bottom panels) than in HCN1+/+ or ICR neurons (middle and top panels, respectively). Recordings were made in the presence of 40 μM DNQX, 1 μM strychnine, 1 μM TTX, 0.25 mM Cd2+, and 50 nM α-DTX.

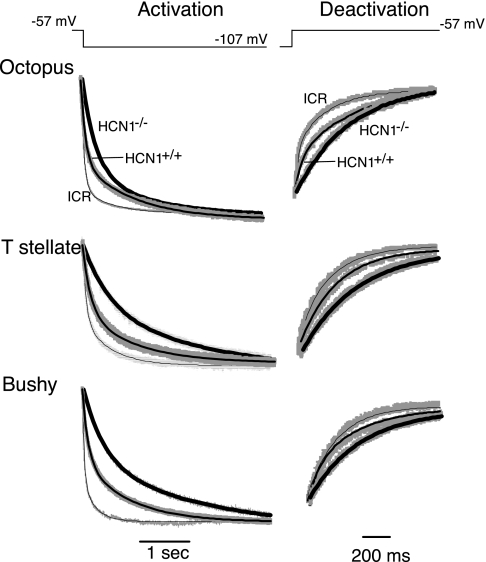

The rates of activation and deactivation of Ih were slower in neurons from the HCN1−/− relative to HCN1+/+ and ICR (Fig. 3). This finding is consistent with the observation that homomeric HCN1 channels have the fastest kinetics (Moosmang et al. 2001); in HCN1−/− mutants, many of the channels that mediate Ih are formed from subunits that form slower channels. The rate constants were measured and compared for the activation of Ih when the voltage was stepped from −57 mV to −107 mV and for deactivation when the voltage was stepped back from −107 mV to −57 mV (Fig. 4 and Table 1). Activation of Ih was well fit with the sum of two exponential functions with τf and τs (Fig. 4). In all three groups of neurons, both τf and τs were longer, and τs was more prominent in HCN1−/− than in HCN1+/+ (Table 1). Deactivation was assessed with single exponential functions in responses to voltage steps from −107 mV to −57 mV (Fig. 4, right). The time constants of deactivation were between 25% and 30% longer in HCN1−/− mutants than in HCN1+/+ (Table 1). In octopus and bushy cells but not in T stellate cells, deactivation of Ih was slower in HCN1+/+ mice than in ICR mice (Fig. 4 and Table 1). The difference in kinetics between ICR and HCN1+/+ mice could reflect a difference in the composition of the HCN ion channels between wild-type strains.

Fig. 4.

In all 3 groups of principal cells of the ventral cochlear nucleus, the kinetics of the activation and deactivation of Ih are slower in HCN1−/− than in HCN1+/+, and they are slower in HCN1+/+ than in ICR mice. Left: traces show responses to voltage steps from −57 mV to −107 mV in examples of each of the 3 cell types. Traces were fit with the sum of 2 exponential functions from the beginning of the activation of Ih to near the steady-state; panels illustrate only the early parts of those traces and the double exponential fit. Recordings from individual cells from the 3 strains of mice are superimposed for comparison. The heavy lines are double exponential fits to HCN1−/− cells, intermediate lines are fits to HCN1+/+, and the finest lines are fits to ICR mice. Right: traces show tail currents when the voltage was stepped back from −107 to −57 mV and were fit with single exponential functions. The heavy lines show fits to traces from mutant HCN1−/− cells, intermediate lines show the fits to HCN1+/+, and the finest lines show fits to traces from ICR mice.

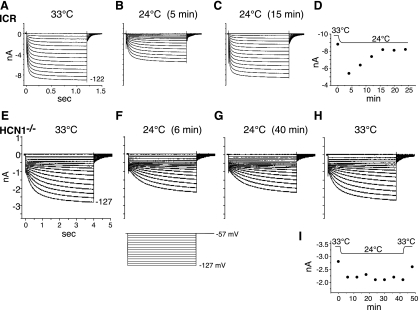

Adaptation of Ih to changes in temperature in octopus cells was absent in HCN1−/− mice.

Temperature is an important determinant of the rates of physical processes, so it is expected that ion channels open and close more rapidly at 33°C than at 24°C. In octopus cells of ICR mice, but not in bushy or T stellate cells, the amplitude of Ih adapts with changes in temperature. In ICR mice, downward shifts in temperature cause an initial reduction in Ih, but the maximal amplitude returns to its original levels within about 15 min (Fig. 5, A–D); upward shifts in temperature increase the maximal amplitude transiently and adapt to the original level over minutes (Cao and Oertel 2005). A similar series of measurements was made in octopus cells of HCN1−/− mice. Figure 5 (E–I) shows that in an octopus cell of a HCN1−/− mouse, a reduction in temperature reduced the amplitude, which then remained stable over 40 min. When the temperature was elevated at the end of that period, the amplitude increased to nearly its original value. The regulation of Ih in octopus cells of HCN1−/−, therefore, resembles that in bushy and T stellate cells of ICR mice.

Fig. 5.

Mouse strains differ in regulation of the magnitude of Ih in octopus cells. A–C: in an octopus cell from an ICR mouse, the temperature was shifted from 33°C to 24°C, and the cell's properties were assayed by stepping the voltage from −57 mV to a range of voltages between −57 and −122 mV. Five minutes after the temperature was reduced to 24°C, the same voltage steps evoked currents that were slower and smaller. Over the next 15 min, while the cell continued to be held at 24°C, the amplitude of Ih grew to near its original amplitude at the steady-state and remained slower than at 33°C. D: a plot of the amplitude of the steady-state current in response to a voltage step to −122 mV shows the time course with which the amplitude of the current returns to near the original value. E–H: a recording from an octopus cell of a HCN1−/− mouse that was subjected to a similar temperature change shows that the amplitude of Ih remained reduced for the 40 min after the temperature was reduced from 33°C to 24°C and that the change was largely reversed by elevating the temperature after that period. I: plot of the time course of the changes in Ih in the same HCN1−/− cell illustrated in E–H.

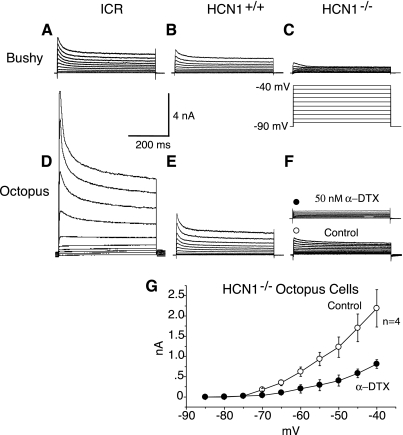

The elimination of HCN1 reduced not only the inward Ih but also the outward IKL current.

The resting properties of octopus and bushy cells in ICR mice are influenced by opposing voltage-gated currents. The inward Ih is activated by hyperpolarization, whereas the outward IKL is activated by depolarization around the resting potential. Both conductances are larger in octopus than in bushy cells (Bal and Oertel 2000, 2001; Cao et al. 2007). Knowing that Ih was reduced in octopus and bushy cells of HCN1−/− mice, we therefore examined IKL in these cells.

We found that IKL was reduced in both octopus and bushy cells of HCN1−/− mice (Fig. 6). [T stellate cells have little or no IKL, even in the wild-type (Ferragamo and Oertel 2002).] Depolarizing voltage steps activated substantial outward currents that inactivated partially and were sensitive to α-DTX (Fig. 6, A–F) (Bal and Oertel 2001). This current was activated in octopus and bushy cells of ICR mice with depolarizing voltage steps that exceeded −75 mV and is the basis for their being termed “low-voltage-activated” (Bal and Oertel 2001; Cao et al. 2007). The α-DTX-sensitive current is smaller in mutant HCN1−/− mice (Fig. 6G). In octopus and bushy cells of HCN1−/− mice, that outward current was substantially reduced (Fig. 6, C and F). There was a large difference in the magnitude of IKL in octopus cells of the mice that have HCN1—ICR mice and HCN1+/+—showing that differences in IKL between strains parallel differences in Ih.

Fig. 6.

The magnitude of low-voltage-activated potassium (IKL) currents is reduced in neurons of HCN1−/− mice relative to HCN1+/+ in octopus and bushy cells. A: In a bushy cell from an ICR mouse, depolarizing voltage steps from −90 mV to −40 mV in 5-mV steps (shown in C) activated a voltage-sensitive outward current. B: in a bushy cell from a HCN1+/+ mouse, similar voltage steps evoked similar outward currents. C: In a bushy cell of a HCN1−/− mouse, outward currents evoked by similar voltage steps were smaller. Inset: voltage protocol applies to A–F. D: in an octopus cell from an ICR mouse, depolarizing voltage steps evoked large outward currents. E: similar voltage steps, applied to an octopus cell of a HCN1+/+ mouse, evoked smaller outward currents. F: in an octopus cell from a HCN1−/− mutant mouse, outward currents evoked by the same protocol were smaller still. Inset: more than one-half of the outward current was blocked by the application of 50 nM α-dendrotoxin (α-DTX). G: current/voltage relationship of average peak outward current in HCN1−/− octopus cells (n = 4) as a function of voltage under control conditions (o) and in the presence of 50 nM α-DTX (●). Recordings were made in the presence of 50 μM ZD7288, 1 μM TTX, 0.25 mM CdCl2, 40 μM DNQX, and 1 μM strychnine.

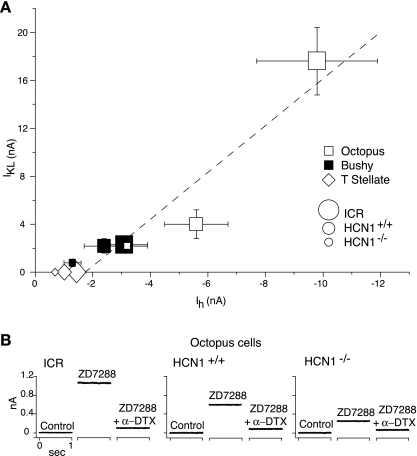

Magnitudes of IKL and Ih co-vary.

The amplitudes of Ih and IKL were measured in populations of neurons and compared. Ih was measured as the steady-state inward current at the end of a hyperpolarizing voltage step from −57 to −122 mV, a step from a voltage at which Ih is activated <10% to a voltage at which it is activated 100% in all three types of principal cells (Bal and Oertel 2000; Cao et al. 2007; Rodrigues and Oertel 2006). Measurements were made in the presence of TTX, CdCl2, DNQX, strychnine, and α-DTX, blockers of potentially contaminating currents. Leak currents were not substracted, but these represent <10% of the measured current in neurons from ICR mice (Bal and Oertel 2000; Cao et al. 2007; Rodrigues and Oertel 2006). IKL was measured as the peak outward current in response to step depolarizations from −90 mV, a voltage at which IKL is not activated, to −40 mV, the voltage at which the high-voltage-activated potassium conductance begins to activate (Bal and Oertel 2001; Cao et al. 2007). The extracellular presence of TTX, CdCl2, DNQX, strychnine, as well as ZD7288 blocked potentially contaminating currents (Bal and Oertel 2001; Cao et al. 2007).

A plot of IKL as a function of Ih shows that Ih and IKL co-vary and that the relationship between Ih and IKL holds for all types of principal cells of the VCN (Fig. 7). The HCN1−/− bushy cells that have, on average, the smallest Ih also have the smallest average IKL; the ICR octopus cells that have the largest Ih have the largest average IKL. T stellate cells have the smallest Ih and have no measurable IKL (Ferragamo and Oertel 2002); the magnitude of Ih in T stellate cells is put into the context of Ih and IKL of bushy and octopus cells in Fig. 7A. The relative magnitudes of Ih and IKL vary monotonically in the three types of principal cells of the VCN in the three strains of mice. These results indicate that the expression at the plasma membrane of HCN channels that mediate Ih is somehow tied to the expression of KCNA channels that mediate IKL in each of the principal cells in each of the three genetic environments.

Fig. 7.

The magnitude of the IKL current is correlated with the magnitude of the opposing Ih inward currents across cell types and across strains of mice. A: the magnitude of Ih was assessed from the size of maximal inward currents evoked at the end of a 2-s voltage step from −57 mV to −122 mV in the presence of 40 μM DNQX, 1 μM strychnine, 1 μM TTX, 0.25 mM CdCl2, and 50 nM α-DTX. This current reflects the sum of Ih and a small leak current. The magnitude of IKL was measured in octopus and bushy cells as the peak outward current in response to voltage steps from −90 mV to −40 mV, measured in the presence of 40 μM DNQX, 1 μM strychnine, 1 μM TTX, 0.25 mM CdCl2, and 50 μM ZD7288. This measurement reflects the sum of IKL and a small leak current. The cell type is designated by the shapes of symbols, and the strain of mice is indicated by the relative size of symbols. Octopus cells of ICR mice have the largest Ih and also have the largest IKL, whereas bushy cells of HCN1−/− mutants have a small Ih and also a small IKL. A regression line, R = 0.95, was fit to measurements of Ih and IKL in octopus and bushy cells in all 3 stains of mice (dashed line). T stellate cells have no measurable IKL (Ferragamo and Oertel 2002); the values of Ih measured in T stellate cells in the 3 strains are shown with diamonds. B: in individual octopus cells, Ih and IKL are balanced at the resting potential. An octopus cell from each of the 3 strains of mice was initially held at the cell's resting potential. Resting potentials of the 3 octopus cells were: ICR −64 mV, HCN1+/+ −66 mV, and HCN1−/− −66 mV. Upon blocking the hyperpolarization-activated, mixed-cation conductance with 50 μM ZD7288, an outward holding current was observed. The further addition of 50 nM α-DTX in the continued presence of ZD7288 reduced the outward holding current to 0.1 nA. The similarity of the magnitudes of currents blocked by ZD7288 and α-DTX in individual cells indicates that in each cell, the inward Ih balanced the outward IKL at the holding potential.

The error bars in Fig. 7A are large, and average values do not lie perfectly along the regression line. In part, this probably results from the variability in the magnitudes of Ih and IKL between cells; comparisons of the isolated Ih and IKL cannot be made within individual cells, because the blockers needed to separate the currents are not fully reversible. It is also possible that the measurements of steady-state Ih and peak IKL do not reflect the parameters that are regulated directly. At physiological membrane potentials, gh is never maximally activated, and the extent of its activation depends, in most cells, on modulation by cyclic nucleotides, and also, gKL is partially inactivated. We therefore used a different experiment to determine to what extent Ih and IKL are matched in individual cells; we determined whether Ih and IKL are balanced in individual cells at the resting potential.

We compared Ih and IKL in individual octopus cells on the basis of their drug sensitivity (Fig. 7B). Octopus cells were held at the resting potential under voltage clamp. The application of 50 μM ZD7288, known to block Ih (Bal and Oertel 2000), resulted in an outward holding current in octopus cells in each of the strains of mice; the subsequent application of 50 nM α-DTX, known to block IKL (Bal and Oertel 2001), reduced the holding currents to within 10% of the original value in all three octopus cells (Fig. 7B). These experiments indicate that Ih and IKL were balanced near the resting potential in octopus cells in all three strains of mice (Oertel et al. 2000). The resting Ih and IKL determined with such experiments was, on average, 1.2 ± 0.2 nA (n = 3) in ICR mice, 0.6 ± 0.1 nA (n = 3) in HCN1+/+ mice, and 0.3 ± 0.1 (n = 5) in the mutant HCN1−/− octopus cells; differences among all groups were statistically significant (P < 0.01). In bushy cells, the magnitudes of IKL and Ih activated at rest are so small that it is impossible to obtain meaningful measurements. Our results indicate that, at least when Ih and IKL are large, they balance one another at the resting potential.

DISCUSSION

A suite of conductances in membranes along processes of characteristic sizes and shapes gives neurons their electrical characteristics. Examining the properties of neurons, in which a conductance or a portion of a conductance is removed, provides a glimpse of not only how that conductance affects the neuron but also of how a perturbation elicits compensatory changes through homeostatic mechanisms. Our study shows that the removal of HCN1 subunits not only reduces Ih but also leads to a reduction of IKL. Furthermore, even in the presence of the gene for HCN1, the magnitude and kinetics of Ih differ in differing genetic environments.

Octopus, T stellate, and bushy cells retain their characteristic features in different strains of mice.

Octopus, T stellate, and bushy cells retain their characteristic features and their resting potentials even when the magnitude and kinetics of Ih vary over a fourfold range. The principal cells of the VCN are as distinct electrophysiologically in mutants as in wild-type strains so that neurons can be recognized on the basis of responses to depolarizing current pulses. Octopus cells respond to suprathreshold depolarization with only a single, small action potential (Golding et al. 1995, 1999). Bushy cells fire transiently with up to six action potentials that do not overshoot 0 mV when they are depolarized (Cao et al. 2007; Manis and Marx 1991; McGinley and Oertel 2006; Wu and Oertel 1984). T stellate cells fire tonically when they are depolarized (Fujino and Oertel 2001; Oertel et al. 1990, 2011). These characteristic properties of neurons are likely common to all mammals, having been described in puppies also (Bal et al. 2009). The resting potentials of all three groups of principal cells varied over ∼5 mV and were not significantly different in mutant HCN1−/−, HCN+/+, and ICR mice. As in other neurons, the intrinsic electrical properties that are characteristic of neuronal types can be generated with a varied array of conductances (Grashow et al. 2010; Marder and Taylor 2011).

Biophysical properties differ not only between HCN1−/− and HCN+/+ mice but also between wild-type strains.

Input resistances in each of the groups of principal cells were elevated in mutant HCN1−/− mice relative to the HCN+/+, as expected, but also differed between ICR and HCN1+/+ mice in octopus and T stellate cells. In octopus cells of ICR mice, input resistances were ∼6 MΩ, consistent with earlier measurements (Golding et al. 1999), whereas they were 14 MΩ in hybrid HCN+/+. Differences were also significant in T stellate cells—74 MΩ in ICR mice compared with 126 MΩ in HCN+/+. There were no significant differences in input resistance of bushy cells between the two wild-type strains, ∼67 MΩ in both.

The removal of HCN1 subunits increases the input resistance, but the expression of a single subunit of gh is governed differently in different groups of principal cells. In the presence of HCN1, the genetic environment affects the input resistance of octopus cells more than the input resistance of bushy cells.

There were unexpectedly large differences in Ih between strains of mice that have HCN1—between the HCN1+/+ and ICR mice. ICR octopus cells have extraordinarily large gh, ∼150 nS (Bal and Oertel 2000). In octopus cells of hybrid HCN+/+ mice, Ih was slower and its magnitude, on average, only about one-half that of ICR mice, revealing the importance of the genetic background in regulating the expression of HCN1. These findings indicate that octopus cells in ICR mice express more HCN channels and are likely of different subunit composition than those of HCN1+/+ mice. Bushy cells have a slower and smaller Ih than octopus cells in ICR mice, on average 30 nS (Cao et al. 2007; Leao et al. 2005, 2006). The magnitude of gh in bushy cells from ICR mice was similar but the kinetics faster than gh from hybrid HCN1+/+. T stellate cells have relatively still slower and smaller maximum gh—19 nS (Rodrigues and Oertel 2006). There was no significant difference in magnitude or kinetics of Ih in T stellate cells of ICR and hybrid HCN1+/+ mice. The differences between ICR and HCN1+/+ raise the question of whether the cochlear nuclei in the HCN1+/+ and mutant HCN1−/− mice are biophysically compromised by their hybrid C57Bl and 129S genetic background. Octopus cells of CBA/J and ICR mice were so similar that biophysical measurements across the two strains were pooled in an early study (Golding et al. 1999). It seems likely that cochlear nuclear neurons in ICR mice resemble those in normal, wild mice more closely than the hybrid HCN1+/+ controls.

Elimination of HCN1 results in smaller and slower Ih.

The present experiments show that Ih was smaller and slower in cells that lack HCN1 than in HCN1+/+. Antibodies detect high levels of HCN1 in octopus cells, lower levels in the anterior VCN, where bushy cells lie, and least in the multipolar cell area where T stellate cells are most common (Koch et al. 2004; Oertel et al. 2008). HCN2 is also strongly expressed in the VCN, but its distribution is more even (Koch et al. 2004). HCN4 is also strongly expressed in the octopus cell area (Notomi and Shigemoto 2004). Consistent with their known properties, we find that the removal of HCN1, the subunit with the fastest kinetics, results in Ih with slower kinetics (Table 1) (Altomare et al. 2003; Moosmang et al. 2001; Ulens and Tytgat 2001; Whitaker et al. 2007). Ih in octopus cells of HCN1−/− mice fails to adapt to changes in temperature as it does in ICR mice (Cao and Oertel 2005). Presumably, this difference reflects a difference in the trafficking of HCN channels.

The magnitude of Ih and IKL co-varies.

The ability to encode precise timing of the fine structure of sounds by octopus and bushy cells is thought to be a consequence of IKL, which gives these neurons short time constants and rate-of-depolarization sensitivity and whose rapid activation cuts excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) short, giving them a sharp peak whose timing is relatively independent of amplitude (Cao et al. 2007; Ferragamo and Oertel 2002; Golding et al. 1995; Manis and Marx 1991; McGinley and Oertel 2006; Rothman and Manis 2003). T stellate cells have little or no gKL (Ferragamo and Oertel 2002). In contrast with gKL, which shapes EPSPs, gh acts like a passive conductance. Under physiological conditions, principal cells of the VCN are not hyperpolarized more than −70 mV, the reversal potential of inhibitory postsynaptic potentials, so that gh is always only partially activated. Its kinetics are so slow relative to synaptic responses that its activation would be expected to be influenced only when synaptic activity is sustained. Individual EPSPs are only 1 ms in duration in octopus cells (Golding et al. 1995) and about 2 ms in bushy cells (Oertel 1985). In T stellate cells, EPSPs can last hundreds of milliseconds, but in these cells, gh is not only small, but its voltage range of activation is more negative than in bushy or octopus cells so that only between 4% and 5% of the conductance is activated at the resting potential (Ferragamo et al. 1998; Oertel et al. 2011; Rodrigues and Oertel 2006). Neurons, not only in the VCN but also in other brain stem auditory nuclei, which are the targets of principal cells of the VCN, share these features (Forsythe and Barnes-Davies 1993; Hassfurth et al. 2009; Mathews et al. 2010; Wu 1999).

Pharmacological evidence indicates that IKL in bushy and octopus cells is mediated by ion channels of the KCNA (Kv1 or shaker) family. In octopus cells, IKL is blocked by α-DTX, a toxin that blocks channels that contain KCNA1, KCNA2, and KCNA6 α subunits (Dolly and Parcej 1996; Grissmer et al. 1994; Harvey 1997; Owen et al. 1997; Tytgat et al. 1995). DTX-K, which blocks channels that contain at least one KCNA1 α subunit (Owen et al. 1997; Robertson et al. 1996; Wang et al. 1999), blocks 75% of IKL; tityustoxin Kα, a toxin that is specific for KCNA2 α subunits (Hopkins 1998; Werkman et al. 1993), blocks 60% of IKL. The ion channel composition must be heterogeneous, because differing proportions contain KCNA1 and KCNA2. In bushy cells, too, IKL is sensitive to α-DTX and partially sensitive to DTX-K and to tityustoxin Kα (Cao et al. 2007; Leao et al. 2004).

The present results suggest that the magnitude of IKL depends on the magnitude of Ih. Removal of the HCN1 subunit reduced Ih relative to the HCN1+/+ in both octopus and bushy cells and resulted in a parallel loss of IKL in both groups of principal cells (Fig. 7A). It is unclear what genetic difference underlies the difference in the magnitude of Ih between ICR and HCN1+/+, but the positive correlation in the amplitudes of Ih and IKL pertains to octopus cells in that strain too (Fig. 7A). Octopus cells from ICR mice had the largest Ih and the largest IKL; bushy cells in HCN1−/− mice had the smaller Ih and smallest IKL. The relationship between Ih and IKL even holds for T stellate cells that have little or no IKL; a line fit through the data points representing measurements from bushy and octopus cells suggests that neurons can have a small Ih in the absence of IKL.

It is possible that a role of Ih is to balance IKL. Ih is an inward current near the resting potential, whereas IKL is an outward current. The positive correlation between the magnitudes of Ih and IKL is evident in octopus cells that have the largest IKL, in which those currents balance one another even in individual cells (Oertel et al. 2000) (Fig. 7B). Bushy cells that have a smaller IKL also have a smaller Ih than octopus cells. The fact that IKL is too small at rest to measure with precision also indicates that it could be balanced by small inward currents other than Ih. In T stellate cells, Ih at rest is small. Not only is the total gh small, but the voltage sensitivity of Ih is more negative than in bushy or octopus cells so that at rest, a relatively smaller proportion of the current is activated than in octopus or bushy cells (Rodrigues and Oertel 2006). Many neurons in the superior olivary complex, including neurons in the medial superior olive, medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB), medial superior olivary nuclei, lateral superior olivary nuclei (LSO), and ventral nucleus of the lateral lemniscus, have the combination of Ih and IKL and likely follow a similar relationship (Banks et al. 1993; Barnes-Davies et al. 2004; Hassfurth et al. 2009; Koch et al. 2004; Leao et al. 2006; Notomi and Shigemoto 2004; Scott et al. 2005; Wu 1999). Indeed, the co-variation of Ih and IKL is evident in the parallel gradients in the LSO, both being largest in the lateral limb and smallest in the medial limb (Barnes-Davies et al. 2004; Hassfurth et al. 2009). Furthermore, the correlation between Ih and IK is not limited to auditory neurons. For example, the magnitude of mRNA for Ih has been found to co-vary with levels of mRNA for KCND potassium channels (Schulz et al. 2006). These observations suggest that these channels could share a common aspect of trafficking or interactions at the membrane as part of a larger complex, but these functions are only beginning to be understood (Hegle et al. 2010).

Homeostasis.

Much has been learned recently about homeostatic regulation of excitability (Nelson and Turrigiano 2008; Turrigiano et al. 1998). Indeed, currents through KCNA channels have been implicated in regulating the activity and synchrony in networks of hippocampal CA3 cells (Cudmore et al. 2010). The expression of KCNQ channels, too, is regulated by electrical activity (Kullmann and Horn 2010). Activity influences Ih in the MNTB and LSO. Ih, in neurons in the lateral limb of the LSO, where neurons have the largest and fastest Ih, increases at the onset of hearing and after cochlear ablation, but Ih in MNTB neurons, which have smaller and slower Ih, changes little with hearing onset and was reduced after cochlear ablation (Hassfurth et al. 2009). In these cells, these changes were, however, accompanied by changes in the resting potential.

We have shown that the intrinsic electrical properties of each of the groups of principal cells of the VCN, octopus, T stellate, and bushy cells have common features both within a strain of mice and across strains but that they are also variable as in other neurons (Grashow et al. 2010; Marder and Taylor 2011). It is likely that those conductances are regulated by homeostatic mechanisms. The excitability of neurons as well as the strength of synapses have been shown to be homeostatically regulated to keep the excitability of neurons within the dynamic range (Davis 2006; Pratt and Aizenman 2007; Wilhelm et al. 2009). In cortical neurons, it seems that firing rate is regulated by homeostasis (Turrigiano et al. 1998). In some invertebrate neurons, it seems to be firing patterns that are regulated (Haedo and Golowasch 2006; Olypher et al. 2006).

Three findings in the present study support the possibility that the resting potential is homeostatically regulated. First, even when the expression of Ih and IKL spans a wide range, the resting potential remains constant. Second, there is a positive correlation between the magnitude of Ih and IKL, not only within one type of cell but across cell types. Third, in individual octopus cells, even when the magnitudes of the currents vary over a factor of 4, Ih and IKL are balanced at the resting potential.

Summary.

Our findings show that the principal cells of the VCN retain their characteristic properties in strains of mice, even when the magnitudes of conductances differ significantly. The finding that Ih and IKL are balanced across widely differing conditions suggests that their relative levels are regulated homeostatically. It is not yet known whether the temporal resolution in hearing parallels the differences in intrinsic characteristics of these neurons.

GRANTS

The work was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (DC00176).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Samantha Wright, who helped with anatomical studies, has been a part of many discussions, and read the manuscript critically. We are fortunate to have technical aspects of our work supported by Ravi Kochhar and to have expert administrative support from Ladera Barnes, Sue Krey, and Rebecca Welch, for which we are most grateful.

REFERENCES

- Adams JC. Projections from octopus cells of the posteroventral cochlear nucleus to the ventral nucleus of the lateral lemniscus in cat and human. Auditory Neurosci 3: 335–350, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- Altomare C, Terragni B, Brioschi C, Milanesi R, Pagliuca C, Viscomi C, Moroni A, Baruscotti M, Altomare C, Terrangni B, Brioshi C, Milanesi R, Pegliuca C, Viscomi C, Moroni A, Baruscotti M, Baruscotti M, DiFrancesco D. Heteromeric HCN1-HCN4 channels: a comparison with native pacemaker channels from the rabbit sinoatrial node. J Physiol 549: 347–359, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bal R, Baydas G, Naziroglu M. Electrophysiological properties of ventral cochlear nucleus neurons of the dog. Hear Res 256: 93–103, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bal R, Oertel D. Hyperpolarization-activated, mixed-cation current (Ih) in octopus cells of the mammalian cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol 84: 806–817, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bal R, Oertel D. Potassium currents in octopus cells of the mammalian cochlear nuclei. J Neurophysiol 86: 2299–2311, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks MI, Pearce RA, Smith PH. Hyperpolarization-activated cation current (Ih) in neurons of the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body: voltage-clamp analysis and enhancement by norepinephrine and cAMP suggest a modulatory mechanism in the auditory brain stem. J Neurophysiol 70: 1420–1432, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Davies M, Barker MC, Osmani F, Forsythe ID. Kv1 currents mediate a gradient of principal neuron excitability across the tonotopic axis in the rat lateral superior olive. Eur J Neurosci 19: 325–333, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn CC, Sachs MB. The representations of the steady-state vowel sound/e/ in the discharge patterns of cat anteroventral cochlear nucleus neurons. J Neurophysiol 63: 1191–1212, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Oertel D. Temperature affects voltage-sensitive conductances differentially in octopus cells of the mammalian cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol 94: 821–83, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao XJ, Shatadal S, Oertel D. Voltage-sensitive conductances of bushy cells of the mammalian ventral cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol 97: 3961–397, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cudmore RH, Fronzaroli-Molinieres L, Giraud P, Debanne D. Spike-time precision and network synchrony are controlled by the homeostatic regulation of the d-type potassium current. J Neurosci 30: 12885–12895, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuttle MF, Rusznak Z, Wong AY, Owens S, Forsythe ID. Modulation of a presynaptic hyperpolarization-activated cationic current (I(h)) at an excitatory synaptic terminal in the rat auditory brainstem. J Physiol 534: 733–744, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GW. Homeostatic control of neural activity: from phenomenology to molecular design. Annu Rev Neurosci 29: 307–323, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolly JO, Parcej DN. Molecular properties of voltage-gated K+ channels. J Bioenerg Biomembr 28: 231–253, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferragamo MJ, Golding NL, Oertel D. Synaptic inputs to stellate cells in the ventral cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol 79: 51–63, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferragamo MJ, Oertel D. Octopus cells of the mammalian ventral cochlear nucleus sense the rate of depolarization. J Neurophysiol 87: 2262–2270, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe ID, Barnes-Davies M. The binaural auditory pathway: membrane currents limiting multiple action potential generation in the rat medial nucleus of the trapezoid body. Proc Biol Sci 251: 143–150, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujino K, Oertel D. Cholinergic modulation of stellate cells in the mammalian ventral cochlear nucleus. J Neurosci 21: 7372–7383, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gans D, Shevkholeslami K, Peterson DC, Wenstrup J. Temporal features of spectral integration in the inferior colliculus: effects of stimulus duration and rise time. J Neurophysiol 102: 167–80, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding NL, Ferragamo MJ, Oertel D. Role of intrinsic conductances underlying responses to transients in octopus cells of the cochlear nucleus. J Neurosci 19: 2897–2905, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding NL, Robertson D, Oertel D. Recordings from slices indicate that octopus cells of the cochlear nucleus detect coincident firing of auditory nerve fibers with temporal precision. J Neurosci 15: 3138–3153, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grashow R, Brookings T, Marder E. Compensation for variable intrinsic neuronal excitability by circuit-synaptic interactions. J Neurosci 30: 9145–9156, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissmer S, Nguyen AN, Aiyar J, Hanson DC, Mather RJ, Gutman GA, Karmilowicz MJ, Auperin DD, Chandy KG. Pharmacological characterization of five cloned voltage-gated K+ channels, types Kv1.1, 12, 13, 15, and 31, stably expressed in mammalian cell lines. Mol Pharmacol 45: 1227–1234, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haedo RJ, Golowasch J. Ionic mechanism underlying recovery of rhythmic activity in adult isolated neurons. J Neurophysiol 96: 1860–1876, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AL. Recent studies on dendrotoxins and potassium ion channels. Gen Pharmacol 28: 7–12, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassfurth B, Magnusson AK, Grothe B, Koch U. Sensory deprivation regulates the development of the hyperpolarization-activated current in auditory brainstem neurons. Eur J Neurosci 30: 1227–1238, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegle AP, Nazzari H, Roth A, Angoli D, Accili EA. Evolutionary emergence of N-glycosylation as a variable promoter of HCN channel surface expression. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 298: C1066–C1076, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins WF. Toxin and subunit specificity of blocking affinity of three peptide toxins for heteromultimeric, voltage-gated potassium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 285: 1051–1060, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joris PX, Smith PH, Yin TC. Coincidence detection in the auditory system: 50 years after Jeffress. Neuron 21: 1235–1238, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joris PX, Yin TC. Envelope coding in the lateral superior olive. I. Sensitivity to interaural time differences. J Neurophysiol 73: 1043–1062, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch U, Braun M, Kapfer C, Grothe B. Distribution of HCN1 and HCN2 in rat auditory brainstem nuclei. Eur J Neurosci 20: 79–91, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullmann PH, Horn JP. Homeostatic regulation of M-current modulates synaptic integration in secretomotor, but not vasomotor, sympathetic neurons in the bullfrog. J Physiol 588: 923–938, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leao KE, Leao RN, Sun H, Fyffe RE, Walmsley B. Hyperpolarization-activated currents are differentially expressed in mice brainstem auditory nuclei. J Physiol 576: 849–864, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leao RN, Berntson A, Forsythe ID, Walmsley B. Reduced low-voltage activated K+ conductances and enhanced central excitability in a congenitally deaf (dn/dn) mouse. J Physiol 559: 25–33, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leao RN, Svahn K, Berntson A, Walmsley B. Hyperpolarization-activated (I) currents in auditory brainstem neurons of normal and congenitally deaf mice. Eur J Neurosci 22: 147–157, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig A, Zong X, Jeglitsch M, Hofmann F, Biel M. A family of hyperpolarization-activated mammalian cation channels. Nature 393: 587–591, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manis PB, Marx SO. Outward currents in isolated ventral cochlear nucleus neurons. J Neurosci 11: 2865–2880, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder E, Taylor AL. Multiple models to capture the variability in biological neurons and networks. Nat Neurosci 14: 133–138, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews PJ, Jercog PE, Rinzel J, Scott LL, Golding NL. Control of submillisecond synaptic timing in binaural coincidence detectors by K(v)1 channels. Nat Neurosci 13: 601–609, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May BJ, Prell GS, Sachs MB. Vowel representations in the ventral cochlear nucleus of the cat: effects of level, background noise, and behavioral state. J Neurophysiol 79: 1755–1767, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinley MJ, Oertel D. Rate thresholds determine the precision of temporal integration in principal cells of the ventral cochlear nucleus. Hear Res 216–217: 52–63, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo ZL, Davis RL. Heterogeneous voltage dependence of inward rectifier currents in spiral ganglion neurons. J Neurophysiol 78: 3019–3027, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moosmang S, Biel M, Hofmann F, Ludwig A. Differential distribution of four hyperpolarization-activated cation channels in mouse brain. Biol Chem 380: 975–98, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moosmang S, Stieber J, Zong X, Biel M, Hofmann F, Ludwig A. Cellular expression and functional characterization of four hyperpolarization-activated pacemaker channels in cardiac and neuronal tissues. Eur J Biochem 268: 1646–1652, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needham K, Paolini AG. Fast inhibition underlies the transmission of auditory information between cochlear nuclei. J Neurosci 23: 6357–6361, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson SB, Turrigiano GG. Strength through diversity. Neuron 60: 477–482, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan MF, Malleret G, Lee KH, Gibbs E, Dudman JT, Santoro B, Yin D, Thompson RF, Siegelbaum SA, Kandel ER, Morozov A. The hyperpolarization-activated HCN1 channel is important for motor learning and neuronal integration by cerebellar Purkinje cells. Cell 115: 551–564, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notomi T, Shigemoto R. Immunohistochemical localization of Ih channel subunits, HCN1–4, in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol 471: 241–276, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertel D. Use of brain slices in the study of the auditory system: spatial and temporal summation of synaptic inputs in cells in the anteroventral cochlear nucleus of the mouse. J Acoust Soc Am 78: 328–333, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertel D, Bal R, Gardner SM, Smith PH, Joris PX. Detection of synchrony in the activity of auditory nerve fibers by octopus cells of the mammalian cochlear nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 11773–11779, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertel D, Shatadal S, Cao XJ. In the ventral cochlear nucleus Kv1.1 and subunits of HCN1 are colocalized at surfaces of neurons that have low-voltage-activated and hyperpolarization-activated conductances. Neuroscience 154: 77–86, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertel D, Wright S, Cao XJ, Ferragamo M, Bal R. The multiple functions of T stellate/multipolar/chopper cells in the ventral cochlear nucleus. Hear Res 276: 61–69, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertel D, Wu SH, Garb MW, Dizack C. Morphology and physiology of cells in slice preparations of the posteroventral cochlear nucleus of mice. J Comp Neurol 295: 136–154, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olypher A, Cymbalyuk G, Calabrese RL. Hybrid systems analysis of the control of burst duration by low-voltage-activated calcium current in leech heart interneurons. J Neurophysiol 96: 2857–2867, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen DG, Hall A, Stephens G, Stow J, Robertson B. The relative potencies of dendrotoxins as blockers of the cloned voltage-gated K+ channel, mKv1.1 (MK-1), when stably expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Br J Pharmacol 120: 1029–1034, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt KG, Aizenman CD. Homeostatic regulation of intrinsic excitability and synaptic transmission in a developing visual circuit. J Neurosci 27: 8268–8277, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson B, Owen D, Stow J, Butler C, Newland C. Novel effects of dendrotoxin homologues on subtypes of mammalian Kv1 potassium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. FEBS Lett 383: 26–30, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson RB, Siegelbaum SA. Hyperpolarization-activated cation currents: from molecules to physiological function. Annu Rev Physiol 65: 453–480, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues ARA, Oertel D. Hyperpolarization-activated currents regulate excitability in stellate cells of the mammalian ventral cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol 95: 76–87, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman JS, Manis PB. Differential expression of three distinct potassium currents in the ventral cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol 89: 3070–3082, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro B, Liu DT, Yao H, Bartsch D, Kandel ER, Siegelbaum SA, Tibbs GR. Identification of a gene encoding a hyperpolarization-activated pacemaker channel of brain. Cell 93: 717–729, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield BR. Projections from the cochlear nucleus to the superior paraolivary nucleus in guinea pigs. J Comp Neurol 360: 135–149, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz DJ, Goaillard JM, Marder E. Variable channel expression in identified single and electrically coupled neurons in different animals. Nat Neurosci 9: 356–362, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott LL, Mathews PJ, Golding NL. Posthearing developmental refinement of temporal processing in principal neurons of the medial superior olive. J Neurosci 25: 7887–7895, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, Massie A, Joris PX. Acoustic stria: anatomy of physiologically characterized cells and their axonal projection patterns. J Comp Neurol 482: 349–371, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano GG, Leslie KR, Desai NS, Rutherford LC, Nelson SB. Activity-dependent scaling of quantal amplitude in neocortical neurons. Nature 391: 892–896, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tytgat J, Debont T, Carmeliet E, Daenens P. The alpha-dendrotoxin footprint on a mammalian potassium channel. J Biol Chem 270: 24776–24781, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulens C, Tytgat J. Functional heteromerization of HCN1 and HCN2 pacemaker channels. J Biol Chem 276: 6069–6072, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang FC, Parcej DN, Dolly JO. Alpha subunit compositions of Kv1.1-containing K+ channel subtypes fractionated from rat brain using dendrotoxins. Eur J Biochem 263: 230–237, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werkman TR, Gustafson TA, Rogowski RS, Blaustein MP, Rogawski MA. Tityustoxin-K alpha, a structurally novel and highly potent K+ channel peptide toxin, interacts with the alpha-dendrotoxin binding site on the cloned Kv1.2 K+ channel. Mol Pharmacol 44: 430–436, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker GM, Angoli D, Nazzari H, Shigemoto R, Accili EA. HCN2 and HCN4 isoforms self-assemble and co-assemble with equal preference to form functional pacemaker channels. J Biol Chem 282: 22900–22909, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm JC, Rich MM, Wenner P. Compensatory changes in cellular excitability, not synaptic scaling, contribute to homeostatic recovery of embryonic network activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 6760–6765, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SH. Physiological properties of neurons in the ventral nucleus of the lateral lemniscus of the rat: intrinsic membrane properties and synaptic responses. J Neurophysiol 81: 2862–2874, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SH, Oertel D. Intracellular injection with horseradish peroxidase of physiologically characterized stellate and bushy cells in slices of mouse anteroventral cochlear nucleus. J Neurosci 4: 1577–1588, 1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin TCT. Neural mechanisms of encoding binaural localization cues in the auditory brainstem. In Integrative Functions in the Mammalian Auditory Pathway, edited by Oertel D, Fay RR, Popper AN. New York: Springer, 2002, p. 99–159 [Google Scholar]