Abstract

In the rodent primary visual cortex, maturation of GABA inhibitory circuitry is regulated by visual input and contributes to the onset and progression of ocular dominance (OD) plasticity. Cortical inhibitory circuitry consists of diverse groups of GABAergic interneurons, which display distinct physiological properties and connectivity patterns. Whether different classes of interneurons mature with similar or distinct trajectories and how their maturation profiles relate to experience dependent development are not well understood. We used green fluorescent protein reporter lines to study the maturation of two broad classes of cortical interneurons: parvalbumin-expressing (PV) cells, which are fast spiking and innervate the soma and proximal dendrites, and somatostatin-expressing (SOM) cells, which are regular spiking and target more distal dendrites. Both cell types demonstrate extensive physiological maturation, but with distinct trajectories, from eye opening to the peak of OD plasticity. Typical fast-spiking characteristics of PV cells became enhanced, and synaptic signaling from PV to pyramidal neurons became faster. SOM cells demonstrated a large increase in input resistance and a depolarization of resting membrane potential, resulting in increased excitability. While the substantial maturation of PV cells is consistent with the importance of this source of inhibition in triggering OD plasticity, the significant increase in SOM cell excitability suggests that dendrite-targeted inhibition may also play a role in OD plasticity. More generally, these results underscore the necessity of cell type-based analysis and demonstrate that distinct classes of cortical interneurons have markedly different developmental profiles, which may contribute to the progressive emergence of distinct functional properties of cortical circuits.

Keywords: γ-aminobutyric acid, development

during a brief postnatal period, the closure of one eye can permanently shift the response property of neurons in the primary visual cortex (V1) to favor inputs from the open eye, i.e., ocular dominance (OD) shift (Hubel and Wiesel 1970). OD plasticity has been a premier model to study how sensory experience shapes the development of cortical circuits during a critical period. To shift eye preference during monocular deprivation, visual cortical neurons must first be able to detect the imbalance of converging visual inputs, relayed to the cortex as altered spiking patterns in thalamic axons, before they can engage a cascade of molecular, cellular, and circuitry mechanisms to weaken the deprived eye-associated inputs and strengthen the open eye-associated inputs (Hensch 2005). GABAergic interneurons are crucial in shaping and detecting the precise spatiotemporal patterns of electrical signaling in cortical circuits and in regulating synaptic plasticity (Markram et al. 2004). Accumulating evidence has indicated that proper functioning of GABAergic inhibitory neurons within V1 are critical to establish the necessary physiological milieu that enables OD plasticity. Mice lacking the synaptic isoform of the GABA-synthetic enzyme GAD65 show no OD plasticity, a deficit that can be rescued by cortical infusion of a GABAA receptor agonist (Hensch et al. 1998). In addition, genetic (Huang et al. 1999) and pharmacological (Fagiolini and Hensch 2000) enhancement of the maturation and function of GABA inhibition in V1 induces a precocious critical period. However, the cellular and circuitry mechanisms by which the maturation of cortical inhibition promotes OD plasticity are not well understood.

Synaptic inhibition in the neocortex is achieved by diverse groups of interneurons, which mediate GABA transmission at discrete spatial and temporal niches during circuit operation and demonstrate distinct physiological properties and connectivity patterns (Markram et al. 2004; Burkhalter 2008). Although our understanding of this diversity is far from complete, previous studies have established a major dichotomy in the inhibitory control of pyramidal neurons. Interneurons that innervate pyramidal cell dendrites are responsible for controlling the efficacy and plasticity of glutamatergic inputs that terminate in the same dendritic domain (Miles et al. 1996; Tamas et al. 1997). On the other hand, interneurons targeting the perisomatic region control action potential (AP) generation, timing, and synchrony in pyramidal cell populations (Cobb et al. 1995; Miles et al. 1996). Whether or how these two major sources of inhibition differentially engage molecular and cellular plasticity mechanisms and contribute to OD plasticity is unclear. Previous studies have focused on parvalbumin-expressing (PV) interneurons, which are fast spiking and innervate the perisomatic region of pyramidal neurons (Miles et al. 1996; Tamas et al. 1997). For example, the morphological maturation of perisomatic innervation from PV cells correlates with the timing of the critical period (Chattopadhyaya et al. 2004). In addition, PV interneurons signal through α1-subunit-containing GABAA receptors, and inhibition through these receptors appears critical for OD plasticity (Fagiolini et al. 2004). Furthermore, the homeoprotein orthodenticle homolog 2, which is able to trigger plasticity when transported from the retina to V1, is prominently taken up by PV cells (Sugiyama et al. 2008). These results indicate an important role of PV interneurons and perisomatic inhibition in the onset of OD plasticity. On the other hand, the role of dendrite-targeted inhibition through somatostatin-expressing (SOM) interneurons has not been well studied. OD plasticity ultimately involves structural rewiring of excitatory synapses onto the dendritic spines of pyramidal neurons (Oray et al. 2004; Mataga et al. 2004). Given the powerful role of dendrite-targeted inhibition in controlling synaptic integration (Miles et al. 1996; Perez-Garci et al. 2006), dendritic Ca2+ spikes (Murayama et al. 2009), plasticity (Ballard et al. 2009), and learning (Collinson et al. 2002; Maubach 2003), it is likely that this source of inhibition also contributes to aspects of OD plasticity.

A necessary step toward further understanding the role of these two major classes of GABAergic interneurons in OD plasticity is a characterization of their functional maturation during the critical period. It has been known for decades that maturation of the GABAergic system in the rodent visual cortex follows a postnatal time course (Luhmann and Prince 1991). However, previous studies have primarily used methods such as spontaneous, miniature, or field-evoked inhibitory postsynaptic current (IPSC) recordings (Bosman et al. 2002, 2005; Heinen et al. 2004; Morales et al. 2002), which cannot distinguish the synaptic sources of inhibition. To date, the physiological maturation of PV interneurons during the critical period has not been fully characterized, and the maturation of SOM interneurons has not been explored. Using two green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter mouse lines, here, we present the first comparison of the maturation of inhibition provided by PV and SOM interneurons before and during the critical period for OD plasticity. We found that both classes of interneurons demonstrate substantial physiological maturation from eye opening to the peak of OD plasticity, but with distinct trajectories. While PV cells demonstrated significant maturation in their characteristic fast signaling properties, which plateaued after the onset of critical period, SOM cells demonstrated a profound and steady increase in their excitability, which continued to the peak of OD plasticity.

METHODS

Animals

To identify PV and SOM cells, we used two transgenic mouse lines, B13 and GIN, respectively, that have been previously used to identify these classes of neurons. The B13 line (Dumitriu et al. 2007; Goldberg et al. 2008; Ango et al. 2008; Daw et al. 2010) expresses enhanced GFP (EGFP) driven by the Pv gene. EGFP in the B13 line is expressed selectively in ∼50% of PV cells in the neocortex (Dumitriu et al. 2007). The GIN line expresses EGFP driven by the Gad1 promoter (Oliva et al. 2000), and EGFP is restricted to a subclass of SOM neurons (Oliva et al. 2000; Ma et al. 2006; Halabisky et al. 2006). EGFP in the GIN line is expressed in SOM neurons in both superficial and deep layers of the neocortex (Oliva et al. 2000; Ma et al. 2006), labeling approximately one-third of SOM cells in layer II/III (Ma et al. 2006). Mice were treated in accordance with Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory guidelines on animal husbandry and care/welfare. Experiments were performed on animals between 15 and 30 days after birth [postnatal day (P)15 and P30], as indicated.

Slice Preparation

Acute brain slices were prepared at the appropriate ages. Animals were deeply anesthetized with avertin (tribromoethanol in amyl hydrate, intraperitoneal injection, 0.2 ml/g), and decapitated. Brains were rapidly removed and placed into ice-cold, oxygenated cutting solution, containing (in mM) 110 choline chloride, 2.5 KCl, 25 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 0.5 CaCl2, 7 MgCl2, 25 glucose, 11.6 ascorbic acid, and 3.1 pyruvic acid bubbled with 95% O2-5% CO2. The anterior one-third of the brain and the posterior section containing the cerebellum were removed with coronal cuts. The brains were then glued to the slicing block, anterior face down. Slices were prepared in the choline-based cutting solution on a Microm HM650V (Walldorf, Germany). Coronal slices contained V1 and were 350 μm thick. Slices were transferred to artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) and incubated at 32–34°C for at least 30 min. aCSF contained (in mM) 126 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 25 NaHCO3, 14 glucose, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 1 MgSO4, and 2 CaCl2 bubbled with 95% O2-5% CO2 to pH 7.4. For recording, slices were transferred to a recording chamber continuously perfused with oxygenated aCSF and maintained at 28–30°C.

Biocytin Filling

GFP-positive cells were identified in layer II/III of the visual cortex and patched with a recording pipette containing 0.2% biocytin. These slices were then incubated overnight at 4°C in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4). After fixation, slices were rinsed in PBS (3 times for 5 min) and then incubated overnight in Alexa fluor 568-conjugated streptavidin (1:1,000, Invitrogen) with 0.3% Triton X-1000 in PBS. Slices were then rinsed in PBS (3 times for 5 min) and mounted in Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Labs). Fluorescently labeled neurons were imaged using a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope and reconstructed using Neurolucida (MicroBrightField).

Electrophysiology

All recordings were performed in layer II/III in coronal cut slices and were restricted to V1. Dual whole cell recordings were performed on a two-channel Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). For paired and single whole cell recordings, interneurons were identified by GFP expression under a narrow-band GFP filter set (Chroma Technology, Brattleboro, VT) in an Axioskop FS2 upright microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) with an ORCA-ER camera (Hamamatsu, Hamamatsu City, Japan). The GFP-positive cell was subsequently visualized with differential interference contrast (Zeiss). For paired recordings, a nearby pyramidal neuron (<50 μm) was visually identified by a triangular soma with a distinct apical dendrite oriented toward the pial surface. Patch pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass on a Flaming-Brown micropipette puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) and had a resistance of 2–4 MΩ. In both paired and single cell recordings, the intracellular solution for the interneuron contained (in mM) 130 K-gluconate, 6 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 2 EGTA, 2 HEPES, 2.5 Na-ATP, 0.5 Na-GTP, and 10 Na-phosphocreatine (pH 7.25, 285–295 mosM). The interneuron recording was performed in current clamp for all experiments. For paired recordings, a high internal Cl− concentration was used to magnify IPSC responses in pyramidal neurons to aid with analysis. The pyramidal neuron internal solution contained (in mM) 65 K-gluconate, 65 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 2 EGTA, 2 HEPES, 2.5 Na-ATP, 0.5 Na-GTP, and 10 Na-phosphocreatine (pH 7.25, 285–295 mosM). The postsynaptic pyramidal neuron was held in voltage clamp at −75 mV. Zolpidem was used to assess GABAA receptor α-subunit composition and was purchased from Tocris (Ellisville, MO).

To assess intrinsic properties, interneurons were stimulated with increasing 1-s-long current steps. PV cells were assessed with 50-pA steps starting from −200 pA increasing up to +700 pA, and SOM cells were assessed with 20-pA steps starting from −100 pA increasing up to +200 pA. Maximum current injections of +700 and +200 pA for PV and SOM cells, respectively, were chosen because these were the highest levels that would reliably not produce spike inactivation. For paired recordings, the presynaptic interneuron was stimulated with a brief suprathreshold current injection (0.8–1.2 nA, 3–5 ms). With the exception of short-term plasticity experiments, 1 spike was initiated per trial, with an intertrial interval (ITI) of 5 s. For analysis, 25–50 trials were averaged. For short-term plasticity experiments, presynaptic interneurons were stimulated at 20 Hz, with an ITI of 10 s.

Analysis and Electrophysiological Parameters

All analysis was performed offline with the ClampFit 9.0 (Molecular Devices) program.

Only stable recordings were included for analysis. Data were discarded if series resistance was >25 MΩ or varied by >25%, if resting membrane potential (VM) was greater than −50 mV several minutes after break in, or if membrane resistance (RM) was <50 MΩ. Pairs of neurons were considered synaptically connected if the averaged IPSC was >2 pA.

Membrane properties.

The membrane time constant (τM; in ms) was determined by a monoexponential fit of the hyperpolarizing voltage response (∼10 mV) to a suitable current injection, from resting level to minimum point of sag, if present.

RM (in MΩ) was the slope of the linear portion of voltage responses to a series of negative current steps (current-voltage response curve).

Membrane capacitance (CM; in pF) was determined from the following equation: CM = τM/RM.

VM (in mV) was the stable membrane potential, as determined with no current injection a few minutes after the seal was broken.

AP threshold (VT; in mV) was membrane potential when the rate of rise equaled 5 V/s, as measured in response to the smallest current step able to evoke a spike.

The excitability index (EI; in pA) incorporated multiple properties of a cell to estimate intrinsic excitability, as determined from the following equation: EI = (VT − VM)/RM.

Spiking properties.

Spike half-width (in ms) was the width measured at half-amplitude, between VT and the peak of the AP, measured in response to the smallest current step able to evoke a spike.

Afterhyperpolarization (AHP) amplitude (in mV) was the voltage difference between VT and the most negative point reached after an AP, measured in response to the smallest current step able to evoke a spike.

Spike frequency (in Hz) was the inverse of the first interspike interval (ISI).

Frequency-current slope (in Hz/pA) was the slope of the linear portion of the frequency-current response curve using the initial spike frequency.

Spike frequency adaptation (dimensionless) was the ratio of the last ISI to the fourth ISI. It was assessed at +700 pA for PV cells and +200 pA for SOM cells.

Synaptic properties.

Amplitude (in pA) was measured from baseline (average of 5 ms) to the peak of the averaged IPSC.

The rise time of averaged IPSCs (RTAvg; in ms) was the time from 10–90% of the rising phase of the averaged IPSC.

The rise time of individual IPSCs (RTIndv; in ms) was the average of the 10–90% rise time determined from at least 10 individual IPSC responses that could be resolved from noise. This measure was used to avoid potential error from jitter in presynaptic spiking or IPSC delay but could only be measured for PV→pyramidal (PV→Py) IPSCs due to the very small amplitude of SOM→pyramidal (SOM→Py) IPSCs.

Decay time (in ms) was determined by a monoexponential fit of the decaying phase of averaged IPSCs.

The paired-pulse ratio (PPR; dimensionless) was the ratio of the second IPSC amplitude to the first IPSC amplitude, stimulated at 20 Hz.

Statistics

All data are reported as means ± SD. Significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Tukey's test for all data with greater than two comparison groups. For comparison of two groups, two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test was used. For comparison of distributions, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used. The significance level was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Targeted whole cell current-clamp recordings were made from PV and SOM neurons to analyze membrane and spiking properties. Dual whole cell recordings were made from PV→Py and SOM→Py pairs to analyze synaptic properties. Three age groups were chosen to study the maturation of inhibition in relation to the onset of OD plasticity: the precritical period after eye opening (P15–P17), early in the critical period (P22–P24), and the peak of the critical period (P28–P30) (Gordon and Stryker 1996). All statistical comparisons were across these three age groups unless otherwise noted.

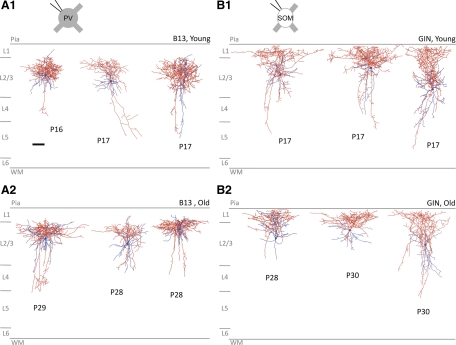

Morphology of GFP-Labeled Cells

Morphological reconstructions were performed to determine which types of cells were labeled in the B13 and GIN lines and to confirm previous reports (see methods). Three cells each in animals from the young age group (P15–P17) and mature age group (P28–P30) in the B13 and GIN lines (total of 12 cells) were reconstructed (Fig. 1). Reconstructed cells in the B13 line (Fig. 1A) generally had dense local axonal arborization restricted to layer II/III, with occasional horizontal or vertical collaterals. This is consistent with identity as nest or small basket cells but not with large basket cells (Wang et al. 2002; Markram et al. 2004). In the GIN line (Fig. 1B), all reconstructed cells had axonal projections up toward the pial surface and extensive arborization within layer I. This supports previous work identifying GIN line cells as Martinotti (MN) cells (Ma et al. 2006).

Fig. 1.

Morphological reconstruction of green fluorescent protein-labeled cells. A, 1: reconstructed cells from young mice in the B13 line. A, 2: mature mice in the B13 line. B, 1: young mice in the GIN line. B, 2: mature mice in the GIN line. Axons, red; soma and dendrites, blue. Specific ages are indicated. P, postnatal day; PV, parvalbumin-expressing cell; SOM, somatostatin-expressing cell. Scale bar = 100 μm.

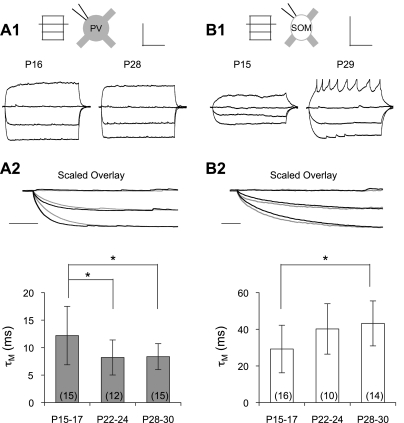

Cell Type-Specific Maturation of Membrane Properties

PV and SOM neuron membrane properties demonstrated distinct developmental profiles over the period studied (Fig. 2). PV cells showed a decrease in τM from eye opening (P15–P17, 12.2 ± 5.3 ms) to the early critical period (P22–P24, 8.2 ± 3.2 ms, P < 0.05), when it reached a steady state (Fig. 2A). On the other hand, in SOM cells, τM increased between eye opening (P15–P17, 29.3 ± 13.0 ms) and the peak of the critical period (P28–P30, 43.2 ± 12.3 ms, P < 0.05; Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Cell type-specific maturation of membrane properties. A, 1: example current step responses (100-pA steps) in PV cells from a young animal (P16) and a mature animal (P28). A, 2: amplitude-scaled overlay (i.e., −200-pA step response set to 1) of the first 100 ms of current-step responses from A, 1. Gray trace, young animal; black trace, mature animal. The membrane time constant (τM) of PV cells decreased during development. B, 1: example current-step responses (20-pA steps) in SOM cells from a young animal (P15) and a mature animal (P29). The mature animal trace shows some truncated spikes. B, 2: amplitude-scaled overlay of the first 150 ms of current-step responses from B, 1. In contrast to PV cells, the τM in SOM cells increased during development. Scale bars = 300 ms and 20 mV in A, 1 and B, 1 and 20 ms in A, 2 and B, 2. *P < 0.05. Sample sizes are shown in parentheses and apply to Figs. 2–6.

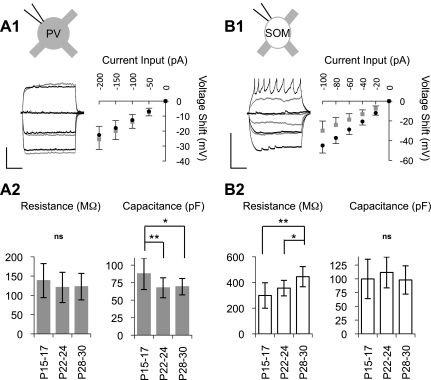

The mechanisms of the changes in τM were different in PV and SOM cells (Fig. 3). In PV cells, RM did not change significantly over the period studied (Fig. 3A); therefore, the reduction in τM of PV cells may be due to a decrease in CM between P15–P17 (87.7 ± 22.5 pF) and P22–P24 (67.7 ± 14.2 pF, P < 0.01; Fig. 3A, 2). In contrast to PV cells, SOM cells showed a substantial RM increase across all three ages studied (P15–P17: 299 ± 99 MΩ and P28–P30: 445 ± 79 MΩ, P < 0.01; Fig. 3B), but CM did not change significantly over the developmental time period tested (Fig. 3B, 2). This increase in RM likely underlies the developmental increase in τM observed in SOM cells.

Fig. 3.

Distinct causes of maturational changes of τM in PV and SOM cells. A, 1: overlayed current-step responses from Fig. 2 and current-voltage relationships of PV cells in young [P16 (gray traces) and P15–P17 (gray square data points)] and mature [P28 (black traces) and P28–P30 (solid circle data points)] animals. A, 2: quantification in three age groups of membrane resistance (RM), determined from the slope of the current-voltage relationship, and membrane capacitance (CM), determined from the following equation: CM = (τM)/(RM). RM did not change significantly with age in PV cells. CM decreased with age and stabilized by the early critical period. B, 1: overlayed current-step responses from Fig. 2 and current-voltage relationships of SOM cells in young [P15 (gray traces) and P15–P17 (gray square data points)] and mature [P29 (black traces) and P28–P30 (solid circle data points)] animals. The mature trace includes some truncated spikes. B, 2: RM of SOM cells increased steadily over the period studied. CM did not change. Scale bars = 300 ms and 20 mV in A, 1 and B, 1. ns, Not signficant. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

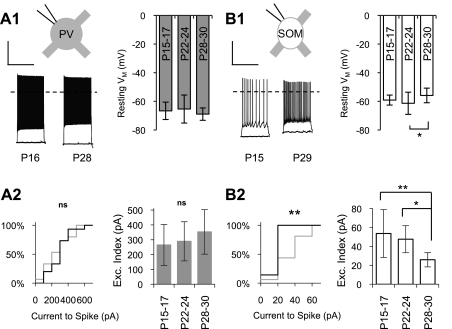

The VM of PV cells was stable over the period studied (Fig. 4A, 1). The VM of SOM cells was stable between P15–P17 and P22–P24 but became significantly more depolarized before the peak of the critical period at P28–P30 (P22–P24: −61.3 ± 7.7 mV and P28–P30: −55.9 ± 5.1 mV, P < 0.05; Fig. 4B, 1). Since VM was measured after the experimental internal solution would have replaced the natural cellular contents, this observed depolarization may reflect a developmental reduction of K+ permeability at rest rather than a change in ion concentrations. A reduction of open K+ channels in SOM cells may explain both the developmental depolarization of VM as well as the developmental increase in RM (Cameron et al. 2000).

Fig. 4.

Cell type-specific maturational changes of neuron excitability. A, 1: membrane potential (VM) with no injected current and in response to a 400-pA current step in example PV cells from a young animal (P16) and a mature animal (P28) (left) and quantification of VM in three age groups (right). VM of PV cells did not change with age. The dashed line represents 0 mV. A, 2, left: the distribution of minimum current injection, in 100-pA intervals, that elicited at least 1 spike in PV cells from young (gray line) and mature (black line) animals did not change with development. Right, the calculated excitability (Exc.) index did not change significantly with age in PV cells. B, 1: VM with no injected current and in response to a 60-pA current step in example SOM cells in a young animal (P15) and a mature animal (P29) (left) and quantification of VM in three age groups (right). VM of SOM cells became more depolarized with development between P22–P24 and P28–P30. B, 2, left: the distribution of minimum current injection, in 20-pA intervals, that elicited at least 1 spike in SOM cells from young (gray line) and mature (black line) animals shifted significantly to the left with age (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, P < 0.01). Right, the calculated excitability index decreased with age in SOM cells. Scale bars = 1,000 ms and 30 mV in A, 1 and B, 1. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Two approaches were used to quantify cell excitability: 1) cumulative distribution of the minimum current injection required for at least one spike to occur (100-pA intervals for PV cells and 20 pA intervals for SOM cells) and 2) EI [expressed in pA and determined by the equation EI = (VT − VM)/RM, as described above]. A lower EI would reflect a more excitable cell, and vice versa.

No changes in cell excitability were observed in PV cells; however, SOM cells demonstrated a substantial increase in excitability with maturation. The current required to evoke spikes in PV cells did not change with development (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, P = 0.89; Fig. 4A, 2), nor did EI change significantly over the period studied (Fig. 4A, 2). In SOM cells, likely due to increased RM and more depolarized VM, a significant shift to the left in the distribution of current required to evoke spikes was observed with maturation (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, P < 0.01; Fig. 4B, 2), along with a twofold reduction of EI (P15–P17: 53.6 ± 25.3 pA and P28–P30: 25.9 ± 7.5 pA, P < 0.01; Fig. 4B, 2).

It should be noted that with the EI measure in mature mice (P28–P30), SOM cells were over 10-fold more excitable than PV cells (Fig. 4A, 2 and B, 2). At all ages, SOM cells, compared with PV cells, demonstrated more hyperpolarized VT (no developmental change; data not shown), larger RM, and more depolarized VM. In other words, all three factors used to determine EI would make SOM cells more excitable than PV cells, suggesting that the SOM source of inhibition may be more frequently or more readily engaged. Additionally, these results are consistent with the description of SOM cells as “low threshold spiking” interneurons (Gibson et al. 1999).

Cell Type-Specific Maturation of Spiking Properties

PV cells showed the fast-spiking properties (Kawaguchi and Kubota 1997) described by McCormick et al. (1985). These include low spike frequency adaptation, large fast AHP, narrow AP half-width, and high spiking frequency. These last three features showed significant maturational changes, leading to more typical fast-spiking characteristics, in PV cells.

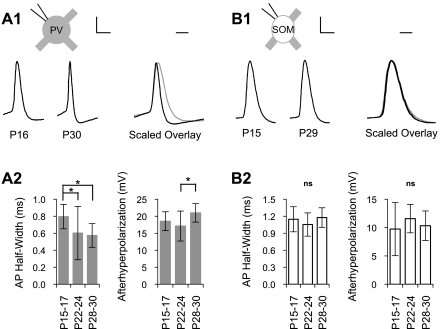

AP morphology substantially changed with maturation in PV cells but not in SOM cells (Fig. 5). The AP half-width of PV cells decreased between P15–P17 (0.80 ± 0.14 ms) and P22–P24 (0.60 ± 0.31 ms, P < 0.05; Fig. 5A), whereas AHP became stronger between P22–P24 (17.1 ± 4.4 mV) and P28–P30 (21.0 ± 2.7 mV, P < 0.05; Fig. 5A). The development of larger AHP was the only maturational feature of PV cells that did not show changes between P15–P17 and P22–P24. Both AP half-width and AHP of SOM cells were stable over the time period studied (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Cell type-specific maturation of action potential (AP) morphology. A, 1, left: example APs in PV cells from a young animal (P16) and a mature animal (P30). Right, amplitude-scaled overlay (i.e., threshold to peak is set to 1) of young (gray trace) and mature (black trace) APs in PV cells demonstrating the reduction in AP half-width and increase of afterhyperpolarization (AHP) with development. A, 2: AP half-width and AHP in PV cells quantified across three ages. B, 1, left: example APs in SOM cells from a young animal (P15) and a mature animal (P29). Right, amplitude-scaled overlay of young (gray trace) and mature (black trace) APs. The gray trace is mostly obscured by the black trace, exemplifying the lack of developmental change in AP morphology. B, 2: AP half-width and AHP in SOM cells quantified across three ages. Scale bars = 20 mV and 2 ms in A, 1 and B, 1 for example spikes and 1 ms in A, 1 and B, 1 for scaled overlays. *P < 0.05.

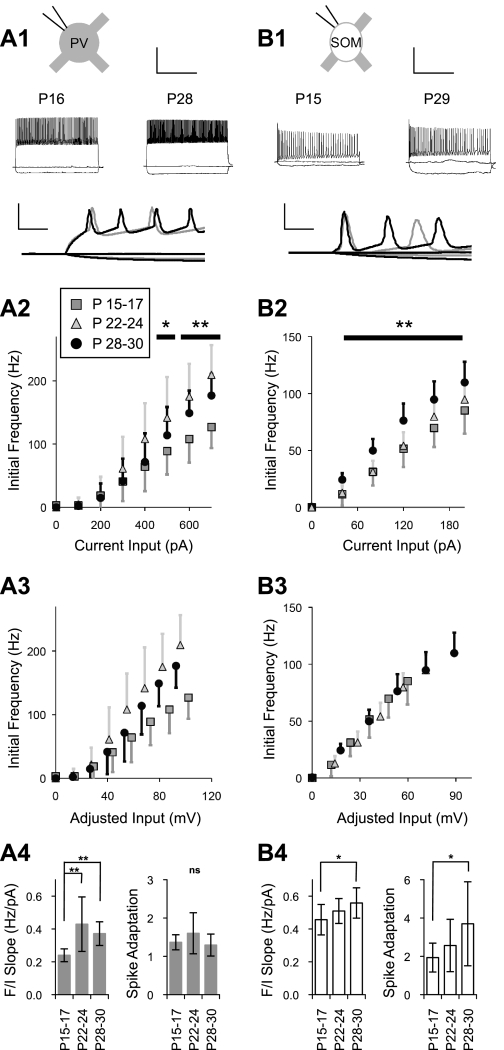

Plots of initial spike frequency versus current injected (frequency-current curves) demonstrated maturational changes for both PV and SOM cells (Fig. 6). In both cell types, the frequency-current curve shifted upward during development. However, in PV cells, the frequency response to a given current input increased with age only for larger current steps (P < 0.05 for 500 pA and P < 0.01 for 600 and 700 pA; Fig. 6A, 2). In SOM cells, higher spike frequencies in older animals were observed across the range of current inputs (P < 0.01 for 40, 80, 120, 160, and 200 pA; Fig. 6B, 2). To determine if changes in RM may contribute to the shift of frequency-current curves, we adjusted these data for developmental differences in RM by multiplying the current input value by the average RM for the specific age group and cell type. This gave an estimation of the predicted membrane potential response (spike activation prevents the full membrane voltage response from occurring) and was expressed in millivolts. Since RM of PV cells did not change with development, adjusting for RM in this cell type had a minimal impact on the relative position of frequency-current curves (Fig. 6A, 3). SOM cells, however, showed a substantial change in RM with development. Adjusting the frequency-current curves of SOM cells for RM eliminated the differences in the frequency response and led to overlapping curves for the different age groups (Fig. 6B, 3). This result suggests that increased RM in SOM cells can largely account for developmental changes in frequency-current response features. Quantification of the frequency-current slope in PV cells showed the increased frequency response occurred between P15–P17 (0.240 ± 0.039 Hz/pA) and P22–P24 (0.429 ± 0.166 Hz/pA, P < 0.01; Fig. 6A, 4); however, in SOM cells, the frequency-current slope increased gradually between P15–P17 (0.457 ± 0.093 Hz/pA) and P28–P30 (0.558 ± 0.092 Hz/pA, P < 0.05; Fig. 6B, 4). Spike adaptation, which is typically low in fast-spiking cells (McCormick et al. 1985), was stable in PV cells over the period studied (Fig. 6A, 4) but increased gradually in SOM cells (P15–P17: 1.94 ± 0.75 and P28–P30: 3.70 ± 2.19, P < 0.05; Fig. 6B, 4).

Fig. 6.

Maturation of spiking properties. A, 1: example current-step responses to −100, 0, and +700 pA in PV cells from a young animal (P16) and a mature animal (P28) along with an overlay of the first 30 ms from young (gray trace) and mature (black trace) animals. B, 1: example current-step responses to −40, 0, and +200 pA in SOM cells from a young animal (P15) and a mature animal (P29) along with an overlay of the first 30 ms. A, 2: initial spike frequency response to current injections in PV cells at ages P15–P17 (gray squares), P22–P24 (gray triangles), and P28–P30 (solid circles). Initial spike frequency in response to large current injections increased with age in PV cells between P15–P17 and P22–P24. The solid horizontal bars indicate the current levels at which a significant difference was observed. B, 2: initial spike frequency response to current injections in SOM cells. Initial spike frequency in SOM cells in response to all current injection levels increased with age. A, 3: data from A, 2 adjusted to the mean RM for each age group. Adjusting for RM did not account for the age-related changes in spike frequency in PV cells. B, 3: data from B, 2 adjusted to the mean RM for each age group. Overlapping data points indicate that adjusting for RM largely accounted for the age-related changes in spike frequency in SOM cells. A, 4: quantification of frequency-current (F/I) slope and spike adaptation across three ages in PV cells. A steepened frequency-current response in PV cells was apparent between P15–P17 and P22–P24, whereas spike adaptation remained stable. B, 4: quantification of frequency-current slope and spike adaptation across three ages in SOM cells. A steepened frequency-current response and increased spike adaptation occured gradually between P15–P17 and P28–P30. Scale bars = 500 ms and 50 mV in A, 1 and B, 1 for full traces and 5 ms and 50 mV in A, 1 and B, 1 for overlays. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

The increased excitability of SOM cells, and the resultant impact on spiking characteristics, appears unique to this cell type, as it is not observed in pyramidal cells (Oswald and Reyes 2008; Desai et al. 2002) or PV cells (Doischer et al. 2008; Okaty et al. 2009). This may reflect increased involvement of this source of inhibition in more mature cortical circuits. The developmental profile of PV cells was consistent with previous studies (Doischer et al. 2008; Okaty et al. 2009; Kuhlman et al. 2010) and demonstrated the postnatal acquisition of fast-spiking characteristics (McCormick et al. 1985).

Source-Specific Maturation of Inhibitory Transmission

The maturational changes of intrinsic properties in PV and SOM cells determine when, if, and how AP firing occurs. But, the impact of cell spiking is, of course, dependent on communication with postsynaptic cells. Therefore, we decided to study the maturation of synaptic connections in PV→Py and SOM→Py pairs during the same developmental time period (Figs. 7 and 8).

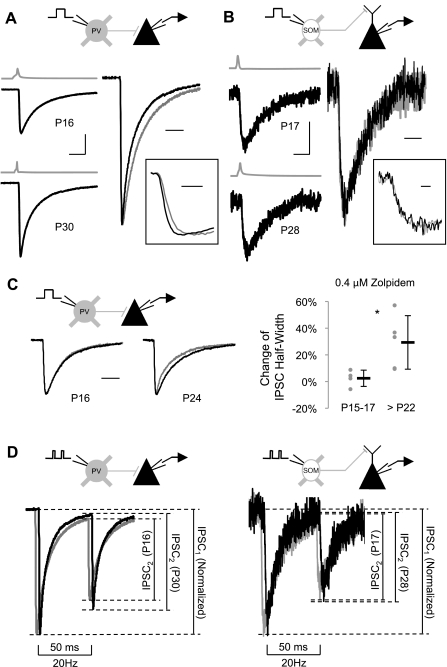

Fig. 7.

Maturation of inhibitory postsynaptic current (IPSC) properties. A, left: example averaged IPSC responses from PV cell (gray traces) to pyramidal cell (black traces) paired recordings in young (P16; top) and mature (P30; bottom) animals. Right, amplitude-scaled overlay of IPSC responses at PV→pyramidal cell (PV→Py) connections in young (gray trace) and mature (black trace) animals. Inset, first 3 ms of overlayed IPSC responses. At PV→Py connections, both IPSC rise time and decay time became faster with development. B, left: example averaged IPSC responses from SOM cell (gray traces) to pyramidal cell (black traces) paired recordings in young (P17; top) and mature (P28; bottom) animals. Right, amplitude-scaled overlay of IPSC responses at SOM→pyramidal cell (SOM→Py) connections in young (gray trace) and mature (black trace) animals. Inset, first 7 ms of overlayed IPSC responses. No developmental changes of IPSCs were detected at SOM→Py connections. C, left: example IPSC responses from PV→Py connections in young (P16) and mature (P24) animals before (gray traces) and during (black traces) the application of zolpidem. In the young animal example, the pre-zolpidem trace is mostly obscured by the zolpidem trace. Right, IPSC kinetics at PV→Py connections were more sensitive to zolpidem in mature mice, suggesting a developmental increase of α1-subunit-containing GABAA receptors. D, left: amplitude-scaled overlay of paired-pulse ratio (PPR)-20 responses at PV→Py connections from young (P16; gray trace) and mature (P30; black trace) animals, slightly offset for clarity. PPR-20 increased with age at PV→Py connections. Right, amplitude-scaled overlay of PPR-20 responses at SOM→Py connections from young (P17; gray trace) and mature (P28; black trace) animals, slightly offset for clarity. No change in PPR-20 was observed at SOM→Py connections. Scale bars = 10 ms, 100 pA, and 190 mV in A, left; 10 ms in A, right; 1 ms in A, inset; 10 ms, 5 pA, and 210 mV in B, left; 10 ms in B, right; 1 ms in B, inset; and 10 ms in C. *P < 0.05 by Student's t-test.

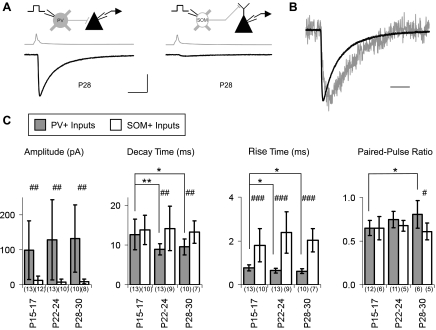

Fig. 8.

Comparison of maturation of IPSC properties at PV→Py and SOM→Py connections. A: example average traces of IPSCs at PV→Py (left) and SOM→Py (right) connections from mature (P28) animals. Gray trace, presynaptic cell; black trace, pyramidal cell. B: amplitude-scaled overlay of IPSCs at PV→Py (black trace) and SOM→Py (gray trace) connections. C: quantification of IPSC properties. The rise time indicated is the rise time of averaged IPSCs. At all ages studied, IPSCs at PV→Py connections had a larger amplitude and faster rise time than IPSCs at SOM→Py connections. Only at mature ages did IPSCs at PV→Py connections have faster decay times and larger PPR-20 than IPSCs at SOM→Py connections. Scale bars = 10 ms, 100 pA, and 160 mV in A and 10 ms in B. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ###P < 0.001 by Student's t-test. Sample sizes are shown in parentheses.

Similar to PV cell intrinsic properties, PV→Py synaptic transmission showed significant maturation in numerous characteristics after eye opening (Fig. 7A). These developmental changes largely stabilized by the early critical period. In contrast, SOM→Py synaptic transmission did not demonstrate any significant changes over the time period studied (Fig. 7B). Synaptic features at both PV→Py and SOM→Py connections are quantified and compared in Fig. 8.

The kinetic properties of IPSCs became faster in PV→Py pairs. IPSC rise times decreased, mostly between P15–P17 (RTAvg: 0.77 ± 0.14 ms and RTIndv: 0.71 ± 0.14 ms) and P22–P24 (RTAvg: 0.65 ± 0.11 ms, P < 0.05; RTIndv: 0.57 ± 0.14 ms, P < 0.05). IPSC decay times also decreased and followed a similar time course (P15–P17: 12.68 ± 3.85 ms and P22–P24: 8.94 ± 1.41 ms, P < 0.01). IPSC amplitude showed a nonsignificant increase (amplitude varied substantially). All of these changes stabilized by P22–P24, with little change apparent between P22–P24 and P28–P30.

To determine if a shift in GABAA receptor subunit composition may underlie the maturational changes in IPSC kinetics, the α1-subunit-specific agonist zolpidem (Munakata et al. 1998) was applied (0.4 μM) (Ali and Thomson 2008) to some PV→Py paired recordings in young (P15–P17) and mature (>P22) slices. Numerous studies have demonstrated a shift in α-subunits from α2/3- to α1-subunits during postnatal maturation (Laurie et al. 1992; Fritschy et al. 1994; Heinen et al. 2004; Hashimoto et al. 2009). α1-Subunit-containing GABAA receptors have faster deactivation properties (Lavoie et al. 1997) and contribute to faster IPSC decay kinetics (Vicini et al. 2001; Bosman et al. 2005). In paired recordings, the application of zolpidem led to a significantly larger increase in IPSC half-width in mature (>P22: 29.3% ± 20.1) compared with young animals (P15–P17: 2.5% ± 6.1, P < 0.05 by Student's t-test; Fig. 7C). This suggests that a relative increase in α1-subunit-containing GABAA receptors contributes to the faster IPSC kinetics observed in older animals. The application of zolpidem did not consistently potentiate IPSC amplitude in any age group (data not shown), likely due to the saturation of GABAA receptors on layer II/III pyramidal neurons (Hajos et al. 2000).

In contrast to PV→Py pairs, SOM→Py connections did not show any maturational changes in IPSC properties. The lack of developmental changes in IPSC kinetics is likely due to the use of GABAA receptor subtypes different from those of perisomatic targeting interneurons; dendritic targeting interneurons signal primarily though α5-subunit-containing GABAA receptors (Ali and Thomson 2008). Although expression of α5-subunits decreases with age (Heinen et al. 2004; Yu et al. 2006), these do not appear to be replaced with a different α-subunit, and therefore kinetic properties would not be expected to change.

In addition to the features of individual IPSCs, short-term synaptic plasticity can also be a key determinant in the function of different types of synaptic connections (Reyes et al. 1998; Markram et al. 1998). For example, excitatory input to PV cells shows short-term depression, whereas excitatory input to SOM cells shows short-term facilitation, possibly resulting in differential engagement of these two sources of inhibition depending on network activity (Reyes et al. 1998). To assess the maturation of short-term plasticity at the output synapses of PV and SOM cells, we measured the PPR at 20 Hz in both PV→Py and SOM→Py pairs (Fig. 7D). Nearly every single paired recording, at both types of synapses and at all ages, demonstrated synaptic depression (one PV→Py pair in the P28–P30 age group was slightly facilitating, PPR = 1.02, but this was the only exception). A gradual increase in PPR occurred in PV→Py pairs from P15–P17 (0.65 ± 0.09) to P28–P30 (0.81 ± 0.16, P < 0.05). This is the only PV synaptic feature that did not appear to stabilize by the early critical period and may reflect an increased ability to sustain activity in the PV inhibitory network. The mechanism of developmental reduction in synaptic depression at these synapses is unclear and would not be explained by increased PV expression (Caillard et al. 2000; Muller et al. 2007). SOM→Py pairs did not demonstrate any changes in PPR.

The distinct developmental profiles of PV and SOM cells contribute to the physiological differences in these two sources of inhibition in the mature V1 (Fig. 8). The mature PV network, by inhibiting proximal cell regions via fast α1-subunit-containing GABAA receptors, is generally expected to provide fast synaptic inhibition. However, in young animals (P15–P17), the decay times of PV→Py and SOM→Py IPSCs were indistinguishable (Fig. 8C). Additionally, mature (P28–P30) PV→Py connections demonstrated less synaptic depression than SOM→Py connections, but this also was a feature that only appeared later in development as a result of maturation of PV synapses (Fig. 8C). Throughout the time period studied, PV→Py IPSCs, compared with SOM→Py IPSCs, had larger amplitudes and faster rise times.

DISCUSSION

Cortical inhibitory circuits consist of diverse classes of interneurons with distinct physiological properties and connectivity patterns (Miles et al. 1996; Kawaguchi and Kubota 1997; Markram et al. 2004; Burkhalter 2008). The maturation profiles of different cell classes and their differential regulation by experience may contribute to the progressive sharpening of functional properties of pyramidal neurons, yet most previous studies on the maturation of cortical inhibition (Bosman et al. 2002, 2005; Heinen et al. 2004; Morales et al. 2002) have not distinguished among different sources of synaptic inhibition. This is the first study, to our knowledge, that directly compares the maturation of two major classes of interneurons during the critical period in V1.

Maturation of Perisomatic Inhibition From PV Interneurons

During the onset phase of the critical period, both the intrinsic and synaptic properties of PV cells become significantly faster and more robust at multiple stages of signal propagation and transmission (Fig. 9). Indeed, the PV τM and AP waveform become faster, and the kinetics of unitary IPSCs become more rapid. The faster membrane properties (lower τM) result from a reduction in CM, which would allow for more rapid integration with enhanced precision in response to synaptic inputs, effectively creating a highly stringent coincidence detector. The rapid AP, along with fast and strong AHP, in PV cells might result from the regulation of ion channel expression and allows PV cells to fire at high frequencies with minimal spike frequency adaptation (Erisir et al. 1999). Additionally, PV cells have the unique property of electrical coupling with one another (Galarreta and Hestrin 1999; Gibson et al. 1999; Beierlein et al. 2000), which could also contribute to the biophysical features of these cells (Veruki et al. 2010).

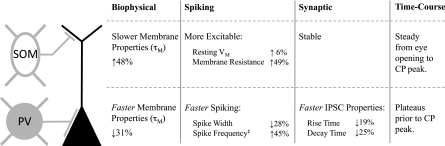

Fig. 9.

Summary of changes in SOM and PV cells and synaptic output. Percentages given indicate changes between P15–P17 and P28–P30. CP, critical period. ‡Measured at 700 pA.

The more rapid IPSC kinetics (i.e., faster decay) at PV→Py synapses seem to result from increased α1-subunit content of postsynaptic GABAA receptors, as evidenced by the enhanced sensitivity to a low concentration of zolpidem. This is consistent with results from multiple brain regions and species showing high expression of α2- or α3-subunits at early stages, with upregulation of α1-subunits at later times (Fritschy et al. 1994; Bosman et al. 2002; Heinen et al. 2004; Vicini et al. 2001; Hashimoto et al. 2009). Consequently, miniature IPSC or spontaneous IPSC recordings, which do not differentiate between presynaptic sources, demonstrate the development of faster inhibitory signaling (Bosman et al. 2002, 2005; Heinen et al. 2004; Vicini et al. 2001; Kotak et al. 2008; Hashimoto et al. 2009). This developmental switch in subunit composition and IPSC properties appears to be a highly conserved, cell type-specific mechanism to sharpen inhibitory transmission during GABA circuit maturation in different cortical areas and species. The concerted changes in synaptic and intrinsic properties, similar to the maturation of basket cells in the dentate gyrus (Doischer et al. 2008), essentially convert V1 PV cells into fast signaling devices during the onset of OD plasticity.

Previous developmental studies on PV cells in the dentate gyrus (Doischer et al. 2008) and somatosensory cortex (Okaty et al. 2009) included much younger neonatal ages and showed, not surprisingly, more profound maturation of some characteristics, including the strength and reliability of synaptic transmission. Our study focused around the critical period and revealed that faster signaling appears to be the main, if not the only, property of PV cells that shows significant maturation, possibly contributing to the onset of OD plasticity.

During OD plasticity, the rearrangement of synaptic connections in V1 is guided by altered visual inputs from the open and closed eyes, which are encoded in the temporal spiking patterns of thalamic axons. The firing of PV cells can precisely reflect the spiking patterns of excitatory inputs, and groups of synaptic and electrically connected PV cells (Galarreta and Hestrin 1999; Gibson et al. 1999; Beierlein et al. 2000) can discriminate synchronous versus less synchronous inputs (e.g., those from the open or closed eye) with millisecond precision (Galareta and Hestrin 2001). Furthermore, mature PV cells are characterized by their “fast in and fast out” signal transmission (Jonas et al. 2004) and thus are highly effective in converting the pattern of excitatory input into well-timed inhibitory output to the perisomatic region, thereby controlling the spiking pattern of innervated pyramidal neurons. PV fast-spiking interneurons therefore appear ideally suited to detect and transmit precise input spiking patterns in V1, a necessary step in the engagement of plasticity mechanisms (Huang and Di Cristo 2008; Hensch 2005), e.g., spike timing-dependent plasticity, which may already be in place at that time (Kuhlman et al. 2010). Here, we have shown that the intrinsic and synaptic properties of V1 PV cells remain immature after eye opening but are significantly sharpened during the onset of OD plasticity. These results suggest that PV cells may develop improved ability to detect and/or transmit changes in input spiking patterns, e.g., from an open versus closed eye. Therefore, the maturation of the PV interneuron network could potentially enable V1 neurons to engage the plasticity mechanisms involved in OD plasticity.

Maturation of Dendrite-Targeted Inhibition From Somatostatin-Expressing Interneurons

SOM interneurons likely include several subgroups (Kawaguchi and Shindou 1998; Wang et al. 2004; Ma et al. 2006). The GIN line used in this study (Oliva et al. 2000) labels subsets of SOM cells, especially MN cells (Fig. 1B) (Ma et al. 2006), which are characterized by their ascending axonal projections, with extensive branching in layer I, and slowly accommodating firing pattern with spikes triggered at low threshold. Importantly, MN cells mediate frequency-dependent disynaptic inhibition (FDDI) among nearby pyramidal cells (Silberberg and Markram 2007), and this is a generic circuit motif prevalent across cortical areas and layers (Berger et al. 2009). FDDI has been postulated to gate synaptic plasticity in distal dendrites (Buchanan and Sjostrom 2009). Furthermore, the dendritic encoding of sensory stimuli in pyramidal neurons is highly sensitive to inhibitory control from MN cells (Murayama et al. 2009). However, the maturation of MN cells and other SOM cells has not been examined, especially during the critical period in V1.

We found that the most apparent developmental changes in SOM interneurons are in cellular biophysical properties: a substantial increase in RM underlies a slower τM in mature cells as well as a steepened frequency-current response curve (Fig. 9). Since CM remained constant, the increase of RM likely results from decreased density of leak channels (Cameron et al. 2000). Increased RM, along with depolarized VM, leads to substantially higher excitability of these cells. Additionally, slower membrane properties would increase the time period over which SOM cells can integrate and respond to synaptic inputs.

These maturation profiles of SOM cells are in sharp contrast to those of pyramidal neurons and PV cells. Postnatal development of layer II/III pyramidal cells leads to lower input resistance (Luhmann and Prince 1991; Desai et al. 2002; Kuhlman et al. 2010) and hyperpolarized VM (Luhmann and Prince 1991; Desai et al. 2002; M. S. Lazarus and Z. J. Huang, unpublished observations), which should reduce cell excitability. The substantial increase of excitability of SOM cells may reflect a stronger engagement of this type of inhibition in V1 circuits during the critical period. Compared with PV cells, we noted that while the maturation of fast signaling in PV cells plateaus early in critical period, the increase of SOM excitability continues to the peak of OD plasticity.

Previous studies on the function of inhibition in OD plasticity have mainly focused on PV cells and their role in triggering the onset of the critical period. Whether and how GABAergic inhibition influences the execution of plasticity mechanisms and promotes the progression of OD shift after the critical period onset is poorly understood. In particular, the functional role of dendrite-targeted inhibition and SOM cells is unexplored. OD plasticity ultimately involves physical rewiring of excitatory synapses onto the dendritic spines of pyramidal neurons (Hofer et al. 2009). A major question remains as to how inputs representing the closed and open eyes compete along the apical dendrites for synaptic connections; in particular, it is unclear whether and how dendrite-targeted inhibition contributes to such competition. The intrinsic and membrane properties of mature SOM cells seem ideally suited to represent the strength of excitatory input and to convert it proportionally into inhibitory outputs, which could act to suppress competing inputs along pyramidal cell dendrites. Our results indicate that the maturational increase in the excitability of SOM cells correlates with the progression of OD plasticity, implying a stronger engagement of dendritic inhibition after the onset of the critical period. Genetic manipulation of SOM cells (e.g., using a SOM cell-specific Cre mouse line) offers the opportunity to directly test their function in OD plasticity.

Conclusions

By studying two distinct classes of visual cortical interneurons during the critical period of OD plasticity, we discovered their distinct maturation profiles. The most prominent feature in fast-spiking, perisomatic targeting PV interneurons is the maturation of fast signaling at the onset of the critical period. The most prominent feature in regular-spiking, dendritic targeting SOM interneurons is the maturation of their excitability and therefore the strength of inhibition, which continues to the peak of OD plasticity. In addition, the maturation of PV and SOM cells seem to exhibit a developmentally enhanced dichotomy: PV cells appear increasingly tuned to detect precisely timed inputs, whereas SOM cells develop stronger ability to detect and thus represent an overall level of input activity. Although our present results are descriptive and correlative by nature, they demonstrate that distinct classes of cortical interneurons have different developmental trajectories, which may progressively sharpen functional and plasticity properties in cortical circuits. This finding underscores the necessity of cell type-specific analysis when studying the development of cortical microcircuits and has general implications in other cortical areas and plasticity paradigms.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Predoctoral Fellowship F30-MH-087036-02 (to M. S. Lazarus) and the Marie and Charles Robertson Fund at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (to Z. J. Huang).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Jiangteng Lu and Dr. Arianna Maffei for helpful comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Ali AB, Thomson AM. Synaptic α5 subunit-containing GABAA receptors mediate IPSPs elicited by dendrite-preferring cells in rat neocortex. Cereb Cortex 18: 1260–1271, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ango F, Wu C, Van der Want JJ, Wu P, Schachner M, Huang ZJ. Bergmann glia and the recognition molecule CHL1 organize GABAergic axons and direct innervation of Purkinje cell dendrites. PLoS Biol 6: e103, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard TM, Knoflach F, Prinssen E, Borroni E, Vivian JA, Basile J, Gasser R, Moreau JL, Wettstein JG, Buettelmann B, Knust H, Thomas AW, Trube G, Hernandez MC. RO4938581, a novel cognitive enhancer acting at GABAA α5 subunit-containing receptors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 202: 207–223, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beierlein M, Gibson JR, Connors BW. A network of electrically coupled interneurons drives synchronized inhibition in neocortex. Nat Neurosci 3: 904–910, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger TK, Perin R, Silberberg G, Markram H. Frequency-dependent disynaptic inhibition in the pyramidal network: a ubiquitous pathway in the developing rat neocortex. J Physiol 587: 5411–5425, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosman LW, Heinen K, Spijker S, Brussaard AB. Mice lacking the major adult GABAA receptor subtype have normal number of synapses, but retain juvenile IPSC kinetics until adulthood. J Neurophysiol 94: 338–346, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosman LW, Rosahl TW, Brussaard AB. Neonatal development of the rat visual cortex: synaptic function of GABAA receptor α subunits. J Physiol 545: 169–181, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan KA, Sjostrom PJ. A piece of the neocortical puzzle: the pyramid-Martinotti cell reciprocating principle. J Physiol 587: 5301–5302, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhalter A. Many specialists for suppressing cortical excitation. Front Neurosci 2: 155–167, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caillard O, Moreno H, Schwaller B, Llano I, Celio MR, Marty A. Role of the calcium-binding protein parvalbumin in short-term synaptic plasticity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 13372–13377, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron WE, Nunez-Abades PA, Kerman IA, Hodgson TM. Role of potassium conductances in determining input resistance of developing brain stem motoneurons. J Neurophysiol 84: 2330–2339, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyaya B, Di Cristo G, Higashiyama H, Knott GW, Kuhlman SJ, Welker E, Huang ZJ. Experience and activity-dependent maturation of perisomatic GABAergic innervation in primary visual cortex during a postnatal critical period. J Neurosci 24: 9598–9611, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb SR, Buhl EH, Halasy K, Paulsen O, Somogyi P. Synchronization of neuronal activity in hippocampus by individual GABAergic interneurons. Nature 378: 75–78, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collinson N, Kuenzi FM, Jarolimek W, Maubach KA, Cothliff R, Sur C, Smith A, Otu FM, Howell O, Atack JR, McKernan RM, Seabrook GR, Dawson GR, Whiting PJ, Rosahl TW. Enhanced learning and memory and altered GABAergic synaptic transmission in mice lacking the α5 subunit of the GABAA receptor. J Neurosci 22: 5572–5580, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daw MI, Pelkey KA, Chittajallu R, McBain CJ. Presynaptic kainate receptor activation preserves asynchronous GABA release despite the reduction in synchronous release from hippocampal cholecystokinin interneurons. J Neurosci 30: 11202–11209, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai NS, Cudmore RH, Nelson SB, Turrigiano GG. Critical periods for experience-dependent synaptic scaling in visual cortex. Nat Neurosci 5: 783–789, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doischer D, Hosp JA, Yanagawa Y, Obata K, Jonas P, Vida I, Bartos M. Postnatal differentiation of basket cells from slow to fast signaling devices. J Neurosci 28: 12956–12968, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumitriu D, Cossart R, Huang J, Yuste R. Correlation between axonal morphologies and synaptic input kinetics of interneurons from mouse visual cortex. Cereb Cortex 17: 81–91, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erisir A, Lau D, Rudy B, Leonard CS. Function of specific K+ channels in sustained high-frequency firing of fast-spiking neocortical interneurons. J Neurophysiol 82: 2476–2489, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagiolini M, Fritschy JM, Low K, Mohler H, Rudolph U, Hensch TK. Specific GABAA circuits for visual cortical plasticity. Science 303: 1681–1683, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagiolini M, Hensch TK. Inhibitory threshold for critical-period activation in primary visual cortex. Nature 404: 183–186, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy JM, Paysan J, Enna A, Mohler H. Switch in the expression of rat GABAA-receptor subtypes during postnatal development: an immunohistochemical study. J Neurosci 14: 5302–5324, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galarreta M, Hestrin S. A network of fast-spiking cells in the neocortex connected by electrical synapses. Nature 402: 72–75, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galarreta M, Hestrin S. Spike transmission and synchrony detection in networks of GABAergic interneurons. Science 292: 2295–2299, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson JR, Beierlein M, Connors BW. Two networks of electrically coupled inhibitory neurons in neocortex. Nature 402: 75–79, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg EM, Clark BD, Zagha E, Nahmani M, Erisir A, Rudy B. K+ channels at the axon initial segment dampen near-threshold excitability of neocortical fast-spiking GABAergic interneurons. Neuron 58: 387–400, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon JA, Stryker MP. Experience-dependent plasticity of binocular responses in the primary visual cortex of the mouse. J Neurosci 16: 3274–3286, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajos N, Nusser Z, Rancz EA, Freund TF, Mody I. Cell type- and synapse-specific variability in synaptic GABAA receptor occupancy. Eur J Neurosci 12: 810–818, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halabisky B, Shen F, Huguenard JR, Prince DA. Electrophysiological classification of somatostatin-positive interneurons in mouse sensorimotor cortex. J Neurophysiol 96: 834–845, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T, Nguyen QL, Rotaru D, Keenan T, Arion D, Beneyto M, Gonzalez-Burgos G, Lewis DA. Protracted developmental trajectories of GABAA receptor α1 and α2 subunit expression in primate prefrontal cortex. Biol Psychiatry 65: 1015–1023, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinen K, Bosman LW, Spijker S, van Pelt J, Smit AB, Voorn P, Baker RE, Brussaard AB. GABAA receptor maturation in relation to eye opening in the rat visual cortex. Neuroscience 124: 161–171, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensch TK. Critical period plasticity in local cortical circuits. Nat Rev Neurosci 6: 877–888, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensch TK, Fagiolini M, Mataga N, Stryker MP, Baekkeskov S, Kash SF. Local GABA circuit control of experience-dependent plasticity in developing visual cortex. Science 282: 1504–1508, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer SB, Mrsic-Flogel TD, Bonhoeffer T, Hubener M. Experience leaves a lasting structural trace in cortical circuits. Nature 457: 313–317, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang ZJ, Di Cristo G. Time to change: retina sends a messenger to promote plasticity in visual cortex. Neuron 59: 355–358, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang ZJ, Kirkwood A, Pizzorusso T, Porciatti V, Morales B, Bear MF, Maffei L, Tonegawa S. BDNF regulates the maturation of inhibition and the critical period of plasticity in mouse visual cortex. Cell 98: 739–755, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel DH, Wiesel TN. The period of susceptibility to the physiological effects of unilateral eye closure in kittens. J Physiol 206: 419–436, 1970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas P, Bischofberger J, Fricker D, Miles R. Interneuron diversity series: fast in, fast out–temporal and spatial signal processing in hippocampal interneurons. Trends Neurosci 27: 30–40, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi Y, Kubota Y. GABAergic cell subtypes and their synaptic connections in rat frontal cortex. Cereb Cortex 7: 476–486, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi Y, Shindou T. Noradrenergic excitation and inhibition of GABAergic cell types in rat frontal cortex. J Neurosci 18: 6963–6976, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotak VC, Takesian AE, Sanes DH. Hearing loss prevents the maturation of GABAergic transmission in the auditory cortex. Cereb Cortex 18: 2098–2108, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlman SJ, Lu J, Lazarus MS, Huang ZJ. Maturation of GABAergic inhibition promotes strengthening of temporally coherent inputs among convergent pathways. PLoS Comput Biol 6: e1000797, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurie DJ, Wisden W, Seeburg PH. The distribution of thirteen GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in the rat brain. III. Embryonic and postnatal development. J Neurosci 12: 4151–4172, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie AM, Tingey JJ, Harrison NL, Pritchett DB, Twyman RE. Activation and deactivation rates of recombinant GABAA receptor channels are dependent on α-subunit isoform. Biophys J 73: 2518–2526, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann HJ, Prince DA. Postnatal maturation of the GABAergic system in rat neocortex. J Neurophysiol 65: 247–263, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Hu H, Berrebi AS, Mathers PH, Agmon A. Distinct subtypes of somatostatin-containing neocortical interneurons revealed in transgenic mice. J Neurosci 26: 5069–5082, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H, Toledo-Rodriguez M, Wang Y, Gupta A, Silberberg G, Wu C. Interneurons of the neocortical inhibitory system. Nat Rev Neurosci 5: 793–807, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H, Wang Y, Tsodyks M. Differential signaling via the same axon of neocortical pyramidal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 5323–5328, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mataga N, Mizuguchi Y, Hensch TK. Experience-dependent pruning of dendritic spines in visual cortex by tissue plasminogen activator. Neuron 44: 1031–1041, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maubach K. GABAA receptor subtype selective cognition enhancers. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord 2: 233–239, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA, Connors BW, Lighthall JW, Prince DA. Comparative electrophysiology of pyramidal and sparsely spiny stellate neurons of the neocortex. J Neurophysiol 54: 782–806, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles R, Toth K, Gulyas AI, Hajos N, Freund TF. Differences between somatic and dendritic inhibition in the hippocampus. Neuron 16: 815–823, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales B, Choi SY, Kirkwood A. Dark rearing alters the development of GABAergic transmission in visual cortex. J Neurosci 22: 8084–8090, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller M, Felmy F, Schwaller B, Schneggenburger R. Parvalbumin is a mobile presynaptic Ca2+ buffer in the calyx of held that accelerates the decay of Ca2+ and short-term facilitation. J Neurosci 27: 2261–2271, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munakata M, Jin YH, Akaike N, Nielsen M. Temperature-dependent effect of zolpidem on the GABAA receptor-mediated response at recombinant human GABAA receptor subtypes. Brain Res 807: 199–202, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murayama M, Perez-Garci E, Nevian T, Bock T, Senn W, Larkum ME. Dendritic encoding of sensory stimuli controlled by deep cortical interneurons. Nature 457: 1137–1141, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okaty BW, Miller MN, Sugino K, Hempel CM, Nelson SB. Transcriptional and electrophysiological maturation of neocortical fast-spiking GABAergic interneurons. J Neurosci 29: 7040–7052, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva AA, Jr, Jiang M, Lam T, Smith KL, Swann JW. Novel hippocampal interneuronal subtypes identified using transgenic mice that express green fluorescent protein in GABAergic interneurons. J Neurosci 20: 3354–3368, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oray S, Majewska A, Sur M. Dendritic spine dynamics are regulated by monocular deprivation and extracellular matrix degradation. Neuron 44: 1021–1030, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald AM, Reyes AD. Maturation of intrinsic and synaptic properties of layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons in mouse auditory cortex. J Neurophysiol 99: 2998–3008, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Garci E, Gassmann M, Bettler B, Larkum ME. The GABAB1b isoform mediates long-lasting inhibition of dendritic Ca2+ spikes in layer 5 somatosensory pyramidal neurons. Neuron 50: 603–616, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes A, Lujan R, Rozov A, Burnashev N, Somogyi P, Sakmann B. Target-cell-specific facilitation and depression in neocortical circuits. Nat Neurosci 1: 279–285, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberberg G, Markram H. Disynaptic inhibition between neocortical pyramidal cells mediated by Martinotti cells. Neuron 53: 735–746, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama S, Di Nardo AA, Aizawa S, Matsuo I, Volovitch M, Prochiantz A, Hensch TK. Experience-dependent transfer of Otx2 homeoprotein into the visual cortex activates postnatal plasticity. Cell 134: 508–520, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamas G, Buhl EH, Somogyi P. Fast IPSPs elicited via multiple synaptic release sites by different types of GABAergic neurone in the cat visual cortex. J Physiol 500: 715–738, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veruki ML, Oltedal L, Hartveit E. Electrical coupling and passive membrane properties of AII amacrine cells. J Neurophysiol 103: 1456–1466, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicini S, Ferguson C, Prybylowski K, Kralic J, Morrow AL, Homanics GE. GABAA receptor α1 subunit deletion prevents developmental changes of inhibitory synaptic currents in cerebellar neurons. J Neurosci 21: 3009–3016, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Gupta A, Toledo-Rodriguez M, Wu CZ, Markram H. Anatomical, physiological, molecular and circuit properties of nest basket cells in the developing somatosensory cortex. Cereb Cortex 12: 395–410, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Toledo-Rodriguez M, Gupta A, Wu C, Silberberg G, Luo J, Markram H. Anatomical, physiological and molecular properties of Martinotti cells in the somatosensory cortex of the juvenile rat. J Physiol 561: 65–90, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu ZY, Wang W, Fritschy JM, Witte OW, Redecker C. Changes in neocortical and hippocampal GABAA receptor subunit distribution during brain maturation and aging. Brain Res 1099: 73–81, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]